Abstract

The Migdal–Eliashberg (ME) formalism provides a reliable framework for describing phonon-mediated superconductivity in the adiabatic regime, where the Fermi energy exceeds the characteristic phonon energy. Here, we extend this framework by incorporating first-order vertex corrections to the electron–phonon (e–ph) interaction and evaluating their impact on H3S and Pb using first-principles calculations. For H3S, where the adiabatic assumption breaks down, vertex corrections to the e–ph coupling are substantial. Combined with phonon anharmonicity and the energy dependence of the electronic density of states, these effects yield a predicted critical temperature Tc in excellent agreement with experiment. In contrast, for elemental Pb, where the adiabatic limit holds, vertex corrections are negligible, and the calculated Tc and gap closely match standard ME predictions. This study demonstrates the importance of non-adiabatic corrections in strongly coupled high-Tc hydrides and establishes a robust first-principles framework for accurately predicting superconducting properties across different regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Migdal–Eliashberg (ME) theory1,2,3 is a powerful many-body method for predicting superconducting properties and is widely regarded as the standard theory for conventional phonon-mediated superconductivity4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. The theory, as formulated by Eliashberg2,3, extends the weak-coupling limit of the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) model12 by incorporating Green’s function approach developed by Migdal for describing the electron–phonon (e–ph) interaction in the normal metallic state1. Nowadays, first-principles simulations based on ME theory are performed routinely and at reasonable computational cost13,14,15, showing good agreement with experiments across a wide range of conventional superconductors, from simple metals to complex materials16,17,18,19,20,21.

Nevertheless, ME theory relies on Migdal’s theorem1, which assumes that the dynamics of electrons and ions happen on two well-separated energy scales, in accordance with the adiabatic Born–Oppenheimer approximation22. Migdal argued that vertex corrections to the bare e–ph scattering diagram can be neglected when the parameter λ(ℏω0/εF) is small, where λ is the effective e–ph coupling constant, ω0 is the characteristic phonon frequency, and εF is the Fermi energy. Specifically, it was shown that each additional term in the perturbative expansion of the e–ph vertex is suppressed by at least a factor of the order \(\hslash {\omega }_{0}/{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{F}}} \sim \sqrt{m/M} \sim 1{0}^{-2}\), where m and M are the electron and ion mass. The condition λ(ℏω0/εF) ≪ 1 is satisfied in most metallic systems since the adiabatic parameter ℏω0/εF ≪ 1, given that the electronic energy scale is of the order of several eV, whereas phonon energies are generally only a fraction of an eV.

However, the validity of Migdal’s theorem has been called into question for several classes of superconductors such as superhydrides, fullerides, and systems with low charge carrier densities, where the electronic Fermi energy is small23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. A natural generalization of the Eliashberg theory to the non-adiabatic regime can be achieved through a perturbative diagrammatic approach in the expansion parameter λ(ℏω0/εF)37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in understanding the impact of higher-order e–ph processes on key materials properties (e.g., spectral functions, band-gap renormalization, polaron formation, carrier mobility, or superconducting pairing), but studies that move beyond leading-order approximations remain rare24,32,47,48,49,50,51,52. This scarcity is primarily due to the rapid increase in computational complexity, as even incorporating second-order scattering events is highly nontrivial. Nonetheless, promising progress has been made, with several recent studies achieving such treatments fully from first principles48,49,50. On the superconductivity front, current approaches to non-adiabatic effects within the Eliashberg framework have relied on simplifying approximations. For example, in the anisotropic case, model Hamiltonians for the electronic structure, combined with an isotropic Einstein phonon spectrum and a single e–ph parameter, have been employed to solve the non-adiabatic Eliashberg equations47. In the isotropic case, besides replacing the momentum dependence in all kernels with Fermi-surface averages, further simplifications have been introduced, such as factorizing the lowest-order vertex correction kernel into a product of two e–ph interaction kernels25,47,53,54.

In this work, we develop and implement a first-principles formalism to compute second-order e–ph vertex corrections within the isotropic Eliashberg framework2,3, extending beyond the conventional ME approximation1,8. The main challenge in implementing this general treatment lies in the significantly increased computational cost, driven by two key factors. First, evaluating the vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function requires the computation of four distinct e–ph matrix elements associated with two phonons. Second, incorporating the resulting vertex-corrected e–ph interaction kernel into the Eliashberg equations introduces additional summations over Matsubara frequencies and integrations over electronic energies. Our methodology is implemented in the EPW code and supports both the full-bandwidth (FBW) and Fermi-surface restricted (FSR) approaches55,56,57. The FBW scheme retains the full energy dependence of the density of states (DOS), enabling the inclusion of e–ph scattering processes away from the Fermi level (εF), while FSR assumes a constant DOS near εF.

To demonstrate the capabilities of our non-adiabatic methodology, we investigate the effect of vertex corrections on the superconducting gap and critical temperature (Tc) of H3S. This high-Tc superconductor serves as a prime example of a system where the adiabatic limit breaks down23,27. At 200 GPa, a flat-band feature near εF gives rise to van Hove singularities (vHs), leading to a small effective Fermi energy. Moreover, the characteristic phonon energy in H3S exceeds 200 meV, yielding an adiabatic parameter of ℏω0/εF ≈ 527. We find that the e–ph coupling constant with vertex corrections (λV) remains a significant fraction of the adiabatic coupling strength (λ), highlighting the persistence of strong coupling beyond the adiabatic regime in systems where the adiabatic limit breaks down, as is the case for many recently studied high-Tc hydrides11,27,58.

Apart from vertex corrections, another critical factor in H3S is the breakdown of the harmonic approximation, driven by hydrogen’s low mass and significant quantum fluctuations24,59,60. These anharmonic effects renormalize phonon frequencies, particularly hydrogen-related modes, leading to strong phonon hardening and a consequent reduction in both the e–ph coupling and critical temperature. To examine the interplay between anharmonic and non-adiabatic effects, we compute the e–ph interactions and superconducting properties of H3S by solving the Eliashberg equations in both the adiabatic and non-adiabatic regimes, with and without anharmonic phonons. Our results show that when both anharmonic and non-adiabatic effects are considered together, the resulting Tc falls within the experimental range.

Finally, we analyze the impact of vertex corrections in Pb, where the adiabatic limit is generally considered valid. In this case, including vertex corrections results in a Tc nearly identical to that predicted within the adiabatic framework, confirming their negligible effect in systems where the Migdal approximation holds.

The manuscript is organized as follows. In the ‘Results’ section, we present the non-adiabatic Eliashberg theory and our ab initio implementation, including lowest-order vertex corrections, followed by applications to H3S and Pb, both with and without vertex corrections. A detailed derivation of the vertex correction in the isotropic formalism, along with computational details, is provided in the ‘Methods’ section. The ‘Discussion’ section summarizes our findings, emphasizing cases where vertex corrections play a significant role. Convergence tests and additional data for H3S, considering both harmonic and anharmonic phonons, are reported in the Supplementary Information.

Results

In this section, we review the theoretical framework of phonon-mediated superconductivity, focusing on ME formalism and its extension to incorporate lowest-order vertex corrections. To solve the Eliashberg equations, we employ the FBW approach, which accounts for the full energy dependence of the electronic DOS. This is essential for accurately capturing the effects of sharp structures in the DOS, such as vHs, and allows for calculations with both fixed and self-consistently updated chemical potential (μF). We also present simplified expressions based on the constant DOS FSR approach. To illustrate the effect of vertex corrections, we examine two representative cases, H3S and Pb, with and without vertex contributions.

Electron self-energy with electron–phonon vertex corrections

Within the Nambu formalism61, the Hamiltonian of an electron–phonon interacting system can be written as

where

Here, \({\hat{\tau }}_{i}\) (i = 0, 1, 2, 3) are the Pauli matrices. Each of the terms is described below.

The first term represents the electron Hamiltonian, where \({\hat{\Psi }}_{n{\bf{k}}}\) is a two-component electron field operator

where \({\hat{c}}_{n{\bf{k}}\sigma }^{\dagger }\) and \({\hat{c}}_{n{\bf{k}}\sigma }\) are the creation and annihilation operators for an electronic state with momentum k, band index n, spin σ, and energy εnk. The second term describes the phonon Hamiltonian, where ωqν is the frequency of a phonon mode with momentum q and branch index ν, and \({\hat{a}}_{{\bf{q}}\nu }^{\dagger }\) and \({\hat{a}}_{{\mathbf{q}}\nu}\) are the bosonic creation and annihilation operators. The anharmonic terms, when relevant, are incorporated into Eq. (3) through additional contributions derived from the self-consistent phonon theory, which replaces the true double-well potential with an effective temperature-dependent harmonic potential that minimizes the free energy, as discussed in detail in ref. 62. The third term accounts for the Coulomb contribution, where \({W}_{n{\bf{k}},m{{\bf{k}}}^{{\prime} }}\) are the scattering matrix elements between electrons.

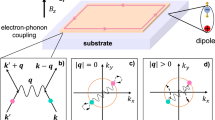

The fourth term describes the e–ph interaction, as illustrated in Fig. 1a, where Np denotes the number of unit cells in the Born–von Kármán (BvK) supercell. This term corresponds to the conventional linear coupling between an electron and a phonon, commonly referred to as the Fan-Migdal term. Higher-order contributions to \({\hat{H}}_{e-ph}\), known as nonlinear e–ph interactions, could also influence materials properties49,50,51,52,63,64, but are not considered in this work. The linear e–ph interaction term is governed by the matrix element \({g}_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}},n{\bf{k}}}^{{\bf{q}}\nu }\), which quantifies the scattering between electronic states nk and mk + q mediated by a phonon with wavevector q and branch index ν. This matrix element is defined as65,66

where unk is the Bloch-periodic part of the Kohn-Sham (KS) electron wavefunction, and the integral is performed over the unit cell (uc). The derivative of the self-consistent potential is given by

Here, κ labels atoms in the unit cell with Mκ as the atomic mass, and α denotes Cartesian directions. The index p labels unit cells with BvK boundary conditions, τκαp is the position of atom κ in the unit cell p, Rp is the lattice vector identifying the unit cell p, and eκα,ν(q) is the eigenvector corresponding to atom κ in the Cartesian direction α for a collective phonon mode qν. The differential ∂VKS(r)/∂τκαp is computed using density functional perturbation theory (DFPT)67. In the presence of anharmonicity, the phonon modes are no longer exact eigenmodes of a harmonic potential, making ΔqνvKS formally ill-defined. To incorporate anharmonic effects within Eq. (8), we retain the harmonic DFPT-computed potential derivatives while replacing the phonon eigenvectors and frequencies with their anharmonically renormalized counterparts, obtained by diagonalizing the dynamical matrix obtained from the special displacement method62.

a First and second-order diagram representing the e–ph vertex. b First and second-order self-energy diagram showing contributions from e–ph interactions. Straight lines indicate bare electron Green’s functions, double lines denote fully dressed electron Green’s functions, and wavy lines represent bare phonon propagators. The second phonon-mediated e–ph vertex is highlighted with red dots.

Using Nambu’s notation, we define the finite-temperature electron Green’s function as a 2 × 2 matrix61:

where \({\hat{T}}_{\tau }\) denotes Wick’s time-ordering operator in imaginary time, and 〈 ⋯ 〉 indicates the grand-canonical thermodynamic average. The diagonal elements correspond to the normal Green’s functions for spin-up and spin-down electrons, describing single-particle electronic excitations. The off-diagonal elements are the anomalous Green’s functions, introduced by Gor’kov68, which describe superconducting Cooper pairs. An important feature of the Nambu–Gor’kov formalism is that, in this matrix representation, the familiar Feynman-Dyson rules of many-body perturbation theory remain valid69.

The study of the superconducting state involves the determination of the matrix Green’s function in Eq. (9). In Matsubara space, this matrix Green’s function obeys the Dyson equation1,70:

where \({\hat{G}}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{0}(i{\omega }_{j})\) is the non-interacting Green’s function

and \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\) is the electron self-energy including contributions arising from the e–ph and Coulomb interactions

In these expressions, iωj = i(2j + 1)πkBT denotes the fermionic Matsubara frequency, where j is an integer, T is the temperature, and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

Following the standard practice, the Coulomb part of the electron self-energy is defined within the GW approximation71,72 as

where \({W}_{n{\bf{k}},m{{\bf{k}}}^{{\prime} }}(i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\) is the dynamically screened Coulomb interaction. Assuming a static screened Coulomb interaction, Eq. (13) simplifies to

where only the off-diagonal components of Green’s function \({\hat{G}}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{od}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\) are retained to avoid double counting Coulomb effects, since the one-particle eigenenergy εnk in \({\hat{G}}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{0}(i{\omega }_{j})\) already includes part of the Coulomb interaction8.

Recent methodological advancements have enabled a fully ab initio treatment of Coulomb interactions within Eliashberg theory17,18,19,73,74,75. However, explicitly incorporating the full Coulomb kernel \({W}_{n{\bf{k}},m{{\bf{k}}}^{{\prime} }}\) in Eq. (14) remains computationally challenging. As a result, this interaction is typically approximated using the semi-empirical Morel-Anderson \({\mu }_{{\rm{c}}}^{* }\) parameter5,76, defined as

where μc is the Fermi-surface averaged Coulomb interaction, ω0 is a characteristic phonon frequency, and εel is the electronic bandwidth. Within the Eliashberg formalism, the corresponding phonon energy scale is given by the Matsubara frequency cutoff ωc, thus \({\mu }_{c}^{* }\) must be replaced by \({\mu }_{{\rm{E}}}^{* }\), which are related via21,77

This approximation is used in the current study.

For the phonon part, the central approximation consists of retaining only the first-order e–ph scattering diagram, shown in Fig. 1b, for \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{ep}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\), in line with Migdal’s theorem1. However, as discussed in the Introduction, this adiabatic approximation fails in several classes of superconductors, necessitating the inclusion of higher-order vertex corrections to the e–ph interaction8,41,43,44,78, which forms the main focus of this work.

A detailed diagrammatic analysis, presented in supplementary Fig. S1, demonstrates that next-order self-energy diagrams, such as the rainbow and parallel bubble diagrams, correspond to Fermi-surface-confined processes whose contributions are already implicitly accounted for in the Migdal approximation8,47,79. In contrast, the lowest-order vertex correction diagram in Fig. 1b captures non-adiabatic effects by involving intermediate electronic states that lie off-shell from the Fermi-surface, as illustrated in the corresponding scattering diagram shown in supplementary Fig. S1. In this work, we only include the lowest-order vertex correction. The explicit treatment of higher-order multi-phonon processes is deferred to future work, motivated by recent analytical toy model results indicating that the rainbow diagram can also influence the superconducting gap51.

The electron self-energy \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{ep}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\), incorporating both adiabatic (A) and non-adiabatic (NA) effects, is given by:

The adiabatic self-energy \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{(A)}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\), corresponding to the first-order Feynman diagram in Fig. 1, is expressed as

where \({g}_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}},n{\bf{k}}}^{{\bf{q}}\nu }\) is the screened e–ph coupling matrix element. Since \({\hat{H}}_{e-ph}\) is Hermitian, the e–ph matrix element satisfy \({g}_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}},n{\bf{k}}}^{{\bf{q}}\nu }={\left[{g}_{n{\bf{k}},m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}}^{-{\bf{q}}\nu }\right]}^{* }\).

Following the standard practice8, we replace the full phonon propagator \({D}_{{\bf{q}}\nu }(i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\) by the bare phonon Green’s function

We define the anisotropic e–ph interaction kernel as

where the anisotropic Eliashberg spectral function is given by

with NF as the DOS per spin at εF. Substituting Eqs. (19)–(21) into the self-energy expression, Eq. (18) takes the compact form

The non-adiabatic self-energy \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{(NA)}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\), corresponding to the second-order Feynman diagram in Fig. 1b, is given by

Here, each matrix element represents an e–ph scattering vertex, associated with either phonon absorption (qν or pμ) or phonon emission (− qν or − pμ). The expression captures a two-phonon scattering process involving four distinct interactions, each requiring explicit evaluation of the corresponding matrix element.

Analogous to the adiabatic case, we substitute the phonon propagators with their bare counterparts and introduce the anisotropic first-order vertex correction to the e–ph coupling via a double spectral representation

where the anisotropic first-order vertex correction to the Eliashberg spectral function is expressed as follows

Using Eqs. (24) and (25), the non-adiabatic electron self-energy can be expressed in a compact form as

Isotropic approximation to electron self-energy

Accounting for the anisotropy in the non-adiabatic self-energy is computationally demanding, as Eq. (26) involves Brillouin zone integrals over two crystal momenta. To date, the most advanced calculations of superconducting properties with anisotropic vertex corrections have relied on several approximations, which include using model Hamiltonians for electronic states, an isotropic Einstein phonon spectrum, and a single e–ph coupling parameter47. However, for most materials, except for a few notable layered systems such as MgB2-type superconductors55,80,81, graphite intercalation compounds82,83, and transition metal dichalcogenides84,85, the effect of this full momentum dependence is weak and an isotropic treatment can be employed19,21. This approximation consists of replacing the k-dependent quantities with their Fermi-surface averages. A detailed derivation is provided in the ‘Methods’ section.

Within the isotropic approximation, the adiabatic self-energy takes the following form

where \(\lambda (i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\) is the isotropic e–ph kernel, expressed as

The kernel is an even function of the Matsubara frequency and attains its maximum at \({\omega }_{j}-{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }}=0\) as given below:

where λ denotes the isotropic e–ph coupling strength. The isotropic Eliashberg spectral function α2F(ω) represents the double Fermi-surface average of α2Fnk,mk+q(ω) and is given by

Following similar steps, the isotropic non-adiabatic self-energy associated with the lowest-order vertex correction can be simplified as

where the isotropic vertex-corrected e–ph kernel

The vertex-corrected kernel attains its maximum at \(i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }}=0\,{\text{and}}\,i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}}=0\), and reduces to

Here, λV is called the vertex-corrected e–ph coupling strength and is a dimensionless measure of the average e–ph coupling strength arising from the non-adiabatic vertex corrections. The isotropic vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) is obtained by performing the Fermi-surface average as follows

Here, the normalization factor C(0) corresponds to the total weight of all four-fold combinations of states at εF expressed as

Computing Eq. (34) has remained a longstanding challenge, even in the isotropic framework, due to the requirement of evaluating four e–ph matrix elements involving two different phonons. To date, additional approximations have been employed, such as estimating the density factor C(0) based on the free-electron model25,53,54, and expressing the vertex-corrected e–ph term \({\lambda }^{{\rm{V}}}(i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }},i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}})\) as a product of two e–ph vertices \(\lambda (i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\lambda (i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}})\)47,53. In this work, we compute this term without relying on these simplifications. We exploit the symmetry under phonon exchange \(({\bf{q}},\nu,\omega )\leftrightarrow ({\bf{p}},\mu,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) to reduce the computational cost. This symmetry, evident from the Feynman diagrams in Fig. 1b, enables us to express \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) in terms of the real part of the four e–ph matrix elements product as detailed in ‘Methods’.

Isotropic non-adiabatic full-bandwidth Eliashberg equations

To obtain the Eliashberg equations, the standard procedure is to express the total self-energy on the basis of Pauli matrices in terms of three scalar functions4,5,8:

where Z(iωj) is the mass renormalization function, χ(iωj) is the energy shift, and ϕ(iωj) is the order parameter. The quantity Δ(iωj) = ϕ(iωj)/Z(iωj) defines the superconducting gap function. Through the Dyson equation (10), the calculation of Green’s function \(\hat{G}(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{{j}})\) is reduced to solving three coupled equations for Z(iωj), χ(iωj), and ϕ(iωj) as derived in ‘Methods’. We refer to this final set as the isotropic non-adiabatic full-bandwidth (NA-FBW) Eliashberg equations and are given by

In Eq. (40), Ne represents the electron number that determines the chemical potential, which is updated self-consistently9,56,57. This is referred to as FBW+μ, while calculations performed with a fixed μF = εF are denoted simply as FBW56,57. The Coulomb interaction enters the Eliashberg expression only through Eq. (39), where it is approximated by the semi-empirical pseudopotential \({\mu }_{{\rm{E}}}^{* }\) introduced earlier. The summation over the Matsubara frequencies in Eqs. (37)–(40) formally extends from −∞ to +∞, however, in practical calculations, it is evaluated over positive Matsubara frequencies only and truncated at a cutoff frequency elaborated in ‘Methods’. We introduce the pseudo-vector γ(ε, iωj) as

and its transpose is given by

along with the matrices PZ(ε, iωj), Pχ(ε, iωj), and Pϕ(ε, iωj) defined as follows:

The elements of γ(ε, iωj), PZ(ε, iωj), Pχ(ε, iωj), and Pϕ(ε, iωj) are given by

with

Isotropic non-adiabatic Fermi-surface restricted Eliashberg equations

We can further simplify the isotropic NA-FBW Eliashberg equations by adopting the constant DOS approximation, such that N(ε) → NF. Assuming an infinite electronic bandwidth at half-filling, the energy integral can be evaluated analytically as described in ‘Methods’, leading to the isotropic non-adiabatic Fermi-surface restricted (NA-FSR) Eliashberg equations

The pseudo-vector \(\tilde{\gamma }(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j})\) and its transpose \({\tilde{\gamma }}^{T}(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j})\), along with the matrices \({\tilde{P}}^{\omega }(i{\omega }_{j})\) and \({\tilde{P}}^{\Delta }(i{\omega }_{j})\) are expressed as

where we define

with Δ(iωj) = ϕ(iωj)/Z(iωj) being the superconducting gap function.

Application examples for H3S and Pb

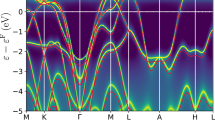

At 200 GPa, H3S crystallizes in the high-symmetry \(Im\bar{3}m\) phase with a lattice parameter of 3.089 Å, consistent with previous theoretical studies59,86,87. The band structure, shown in Fig. 2a, exhibits a broad bandwidth of approximately 25 eV below εF, with parabolic dispersion for the deeper lying bands. The corresponding DOS features two prominent valleys at approximately −1.75 eV and 2.50 eV, as well as a sharp vHs peak near εF. This vHs significantly enhances the e–ph coupling strength, which is a key factor in the high Tc of H3S24,88,89,90. The width of the vHs effectively defines a low Fermi energy scale of approximately 300 meV. Using analytical models for the upper critical field, a small Fermi velocity in the range of (2.1−3.7) × 105 m/s was obtained35,36,91. The corresponding Fermi energy, estimated using \({\varepsilon }_{F}={m}_{e}^{* }{v}_{F}^{2}/2\) with \({m}_{e}^{* }\) as the effective mass of the electron, further confirms the reduced electronic energy scale. This raises important questions about the validity of Migdal’s approximation in this system23,27,36. Figure 2b compares the phonon dispersion and phonon density of states (PhDOS), calculated within the harmonic and anharmonic approximations. The phonon spectrum exhibits a clear separation between low-frequency acoustic modes (below 75 meV), mainly arising from sulfur vibrations, and high-frequency optical modes (above 75 meV), primarily involving hydrogen. This separation is a direct consequence of the large mass difference between S and H atoms. The low-frequency phonon modes are largely unaffected by anharmonicity, in line with a previous study59. This insensitivity stems from the heavier mass and smaller vibrational amplitudes of sulfur atoms, which make them less responsive to anharmonic effects. In contrast, the high-frequency optical modes undergo substantial anharmonic renormalization, with hardening of up to 30 meV observed along several high-symmetry directions. The PhDOS further reinforces this picture. While the spectral features associated with sulfur vibrations remain nearly intact, the high-frequency region shows significant broadening extending up to 243 meV. Accurately capturing these anharmonic effects is essential for a reliable description of vibrational dynamics and superconducting properties of H3S.

The Eliashberg spectral function and the corresponding cumulative e–ph coupling strength for H3S at 200 GPa are shown in Fig. 3a. The harmonic α2F(ω) features a broad central peak spanning the 75−175 meV range, accompanied by a smaller peak at lower frequencies and a distinct sharp peak at 194 meV. As a result, the cumulative λ(ω) increases steadily, with the acoustic region contributing approximately 0.48, and continues to rise throughout the spectrum, ultimately reaching a total value of λ = 2.29, consistent with previous reports18,20,57,86.

a Eliashberg spectral function α2F(ω) and integrated e–ph coupling strength λ(ω) for both harmonic and anharmonic phonons within the adiabatic Migdal approximation. b Vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) and integrated vertex-corrected e–ph coupling strength λV with harmonic (left) and anharmonic (right) phonons.

When anharmonic effects are included, both the phonon frequencies and eigenvectors are renormalized, which in turn modifies the e–ph matrix elements according to Eq. (8). The cumulative e–ph coupling strength λ(ω) from the low-frequency region of sulfur dominated modes increases slightly to 0.56, consistent with the observation that acoustic phonons are only weakly affected by anharmonicity. Above 75 meV, α2F(ω) exhibits two well-separated peaks, corresponding to the softening of the bond-bending and hardening of bond-stretching H modes, respectively. Among these, the bond-stretching modes contribute most significantly to λ. In line with a prior study59, our anharmonic analysis shows a 25% reduction in the e–ph coupling strength, resulting in a revised total value of 1.72.

As discussed earlier, the coexistence of high-frequency hydrogen phonon modes and a low Fermi energy raises concerns about the validity of the standard Migdal approximation in H3S23,24,25,27 and requires taking higher-order vertex corrections into account beyond conventional ME theory. To our knowledge, this work presents the first quantitative computation of the full isotropic lowest-order vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) for this system.

Figure 3b shows 3D plots of \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\), comparing results based on harmonic (left panel) and anharmonic (right panel) phonons. In the harmonic case, \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) displays a broad distribution across the mid- to high-frequency phonon spectrum, with dominant contributions concentrated between 75 and 200 meV. In contrast, the low-frequency acoustic region contributes negligibly, indicating that sulfur modes have minimal impact once vertex corrections are included. The integrated vertex-corrected coupling strength is λV= 1.78, approximately 78% of the corresponding adiabatic value λ = 2.29.

In the anharmonic case, \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) is fragmented, with spectral weight confined in narrower regions of the \((\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) plane. Unlike the harmonic scenario, small intensity peaks emerge in the low-frequency acoustic region, reflecting changes in phonon eigenvectors induced by anharmonicity. At mid-frequencies, the spectral weight is reduced and shifts toward higher energies due to the hardening of hydrogen modes. The total vertex-corrected e–ph coupling strength is substantially reduced, with λV= 0.71, representing nearly a 60% decrease compared to the harmonic vertex-corrected value.

The superconducting properties of H3S have been extensively investigated, with previous calculations primarily based on the adiabatic ME formalism without vertex corrections, using either the FSR59,86 or FBW approach21,24,57. Although the potential significance of vertex corrections has been acknowledged26, earlier isotropic treatments relied on simplified models, either a single Einstein phonon spectrum17,24 or empirical modifications to the vertex-corrected e–ph kernel \({\lambda }^{{\rm{V}}}(i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }},i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}})\)25,54.

In this work, we go beyond such approximations and solve the isotropic Eliashberg equations using the full vertex-corrected e–ph spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\), computed from first principles. Several studies on H3S17,24,57 have emphasized the importance of the FBW description, owing to its narrow electronic bands and the presence of critical features near εF, such as vHs and Lifshitz transitions23,26. To capture these effects, we compute the isotropic superconducting gap Δ(T) using both the FBW and FBW+μ approaches, with and without vertex corrections, while also incorporating anharmonic phonons, as shown in Fig. 4. These calculations explicitly include the energy dependence of the electronic DOS. Consistent with previous studies on H3S57,59, we adopt a Coulomb pseudopotential value of \({\mu }_{{\rm{E}}}^{* }\)= 0.16. When solving the Eliashberg expressions, this choice, combined with an electronic bandwidth εel in the range of 10–25 eV corresponds to μc = 0.21–0.25 via Eqs. (15) and (16), in agreement with values computed ab initio18,73,75.

As shown in Fig. 4, the adiabatic FBW approach yields a zero-temperature superconducting gap of Δ(0)= 37.1 meV, closing at a critical temperature Tc ≈ 189 K. When the chemical potential is updated self-consistently within the FBW+μ scheme, both the gap and Tc increase slightly to 38.6 meV and 195 K, respectively. The inclusion of vertex corrections reduces Δ(0) to approximately 34.5 meV for the ver-FBW and 35.9 meV for the ver-FBW+μ approach. Consequently, the critical temperature is suppressed by 11−12 K relative to the adiabatic case, yielding a Tc of 178 K for the ver-FBW and 183 K for the ver-FBW+μ approach. These theoretical predictions are in excellent agreement with experimental measurements, which report Tc values in the range of 175−185 K for H3S under 200 ± 5 GPa92,93.

This level of agreement is particularly significant given that our approach simultaneously accounts for anharmonic phonon effects, non-adiabatic e–ph vertex corrections, and the energy dependence of the DOS. Notably, we find that a one-shot evaluation of the vertex correction substantially underestimates Tc, demonstrating that iterative self-consistent calculations are essential for accurately quantifying the impact of e–ph vertex renormalization.

For comparison, we also analyze the superconducting gap using the constant DOS FSR approach. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, the resulting Tc values lie outside the experimentally observed range92. Without vertex corrections, Tc is slightly above the value obtained with FBW+μ, while the inclusion of vertex correction leads to a strong underestimation. In Supplementary Sec. II, we provide a detailed discussion of the underlying reasons for the limitations of the FSR approximation. Finally, calculations using harmonic phonons within the FBW, FBW+μ, and FSR approaches, even when incorporating vertex corrections, tend to overestimate the Tc, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2 and summarized in Table 1.

Recent experiments on H3S have reported superconducting gap values from tunneling spectra and Tc values extracted from electrical resistance measurements94. Since these measurements were performed on samples at 151–161 GPa, they are not directly comparable to our calculations at 200 GPa. Nevertheless, the dimensionless BCS ratio 2Δ(0)/kBTc provides a meaningful basis for comparison. Using experimental gap values of 29 meV and 32 meV with Tc = 190 K for samples at 151 GPa and 158 GPa, the corresponding ratios are 3.54 and 3.91, respectively. As summarized in Supplemental Table S1, our calculations yield ratios ranging from 4.27 to 4.55 for anharmonic cases and from 4.52 to 5.00 for harmonic ones, consistent with previous Migdal-Eliashberg results at both harmonic and anharmonic levels57,59. Further theoretical calculations using different exchange-correlation functionals95, together with experimental measurements over a broader pressure range, will be essential for resolving the differences in the BCS ratio. We also note that analysis of upper critical field data has suggested that H3S may exhibit unconventional superconductivity, with a low Fermi velocity and a low Tc/TF ratio placing it close to unconventional superconductors35,36,91.

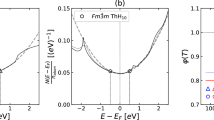

To further test our hypothesis regarding the breakdown of the Migdal approximation and the significance of e–ph vertex corrections, we analyze elemental Pb, a prototypical conventional superconductor. The electronic structure of Pb, shown in Fig. 5, features a broad band, with a nearly flat DOS around εF and sharp features located approximately 2 eV below and above it. The phonon spectrum extends up to ~9 meV and exhibits a pronounced Kohn anomaly near the W-point in the BZ, which is attributed to strong Fermi-surface nesting96.

Although Migdal’s adiabatic condition (ℏω0/εF) is well satisfied in Pb due to the large separation between the electronic and phononic energy scales, the observed Kohn anomaly suggests the presence of nonlinear e–ph interactions53, which are not captured by the standard treatment. These considerations motivate the inclusion of non-adiabatic e–ph vertex effects in our analysis, even for nominally conventional superconductors such as Pb.

To investigate the e–ph interaction in Pb, we computed the isotropic Eliashberg spectral function α2F(ω) and the cumulative e–ph coupling strength λ(ω). As shown in Fig. 6a, α2F(ω) exhibits a broad peak centered around 4.5 meV (transverse phonons) and a narrower peak at 8 meV (longitudinal phonons), consistent with previous reports55,74,97,98. The total e–ph coupling strength, λ=1.29, indicates strong coupling. The high-frequency peak near 7 meV corresponds to the Kohn anomaly at the W point in the phonon dispersion, reflecting enhanced e–ph scattering from Fermi-surface nesting effects96. The cumulative λ(ω) rises sharply below 5 meV, contributing approximately 44% to the total coupling, confirming the dominant role of the low-frequency phonons in mediating Cooper pairing.

a Eliashberg spectral function α2F(ω) and integrated e–ph coupling strength λ(ω). b Vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) and integrated vertex-corrected e–ph coupling strength λV. c Isotropic superconducting gap Δ(T) computed using the adiabatic FSR (solid teal-green), adiabatic FBW (solid orange), vertex-corrected FSR (dashed teal-green with circles), and vertex-corrected FBW (dashed orange with squares) methods for Pb.

With vertex corrections, the 3D spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) (Fig. 6b) retains the characteristic peaks at 5 and 8 meV but yields a very low value of λV = 0.20, representing an 85% decrease relative to the adiabatic λ. This result confirms the validity of Migdal’s approximation for Pb, where vertex corrections are negligible. We note that the e–ph coupling in Pb may be slightly enhanced by the inclusion of spin-orbit coupling, as reported in previous studies98; however, this effect is not expected to alter our conclusions. Additionally, the vertex-corrected tunneling inversion study by Freericks et al.53 found that accounting for the lowest-order vertex correction altered the coupling constant by only ~ 1% and the Tc by less than 2%, further reinforcing the robustness of ME theory for conventional superconductors like Pb. While insightful, their analysis relied on additional simplifying assumptions, such as the constant DOS approach with the vertex-corrected spectral function taken as the product of adiabatic kernels, which may underestimate the vertex effect.

We performed isotropic Eliashberg calculations to compute the superconducting gap Δ(T) using a Coulomb parameter \({\mu }_{{\rm{E}}}^{* }\) = 0.1. Figure 6c shows that the adiabatic FSR approach without vertex corrections yields a zero-temperature gap Δ(0) ≈ 1.3 meV with a gap ratio of 2Δ(0)/kBTc ≈ 4.3, which exceeds the BCS weak-coupling limit and is in good agreement with the experimental Tc ≈ 7.2 K99,100. Both FSR and FBW methods produce nearly similar Δ(T) curves, reflecting the weak energy dependence of the DOS near the Fermi level and the broad electronic bandwidth of Pb. Notably, the inclusion of lowest-order vertex corrections has a negligible impact on the superconducting gap evolution. The vertex-corrected FSR and FBW results lie on top of their adiabatic counterparts across all temperatures. This insensitivity of Δ(0) and Tc to vertex corrections further validates the applicability of ME theory in describing superconductivity in adiabatic and weakly non-adiabatic systems such as Pb.

Discussion

In this work, we revisit the formulation of the lowest-order vertex corrections within the Eliashberg formalism and develop a fully ab initio approach to evaluate the vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function and the corresponding e–ph coupling strength. This methodology, implemented in the EPW code13,56, enables us to move beyond model Hamiltonians and apply the formalism to realistic materials such as H3S and Pb. To solve the isotropic Eliashberg equations, we employ three approaches: the FSR, FBW with a fixed μF, and FBW with a self-consistently updated μF. For H3S, calculations include both harmonic and anharmonic phonons using a Coulomb pseudopotential \({\mu }_{{\rm{E}}}^{* }\)= 0.16, while for Pb, we consider harmonic phonons with \({\mu }_{{\rm{E}}}^{* }\) = 0.10.

For H3S, which exhibits strong e–ph coupling and a van Hove singularity close to the Fermi level, incorporating vertex corrections leads to a significant reduction in both λ and Tc, highlighting the breakdown of the Migdal approximation. The systematic analysis of FSR, FBW, and FBW+μ schemes with and without vertex correction using harmonic and anharmonic phonons (see Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table 1), shows that harmonic phonons systematically overestimate Tc compared to experiment, regardless of the inclusion of e–ph vertex corrections. When effects from phonon anharmonicity and the full energy dependence of electronic DOS are taken into account, the predicted Tc agrees well with experimental measurements, resolving long-standing discrepancies between theory and experiment. Moreover, we observe that the constant-DOS FSR approximation might not provide the correct trend with and without the vertex corrections, particularly in systems with sharp electronic features near the Fermi level. Furthermore, our results show that a one-shot evaluation of vertex corrections severely underestimates Tc, emphasizing the need for fully self-consistent calculations to capture the feedback between e–ph renormalization and superconducting pairing.

In contrast, Pb presents a different scenario. Although Pb satisfies Migdal’s adiabatic condition, the presence of a Kohn anomaly in its phonon dispersion suggests the possibility of nontrivial electron–phonon interactions beyond the adiabatic approximation. This makes Pb a valuable test case for assessing the role of vertex corrections. Our results show these corrections have a negligible effect on both λ and Tc, consistent with the expectations of Migdal-Eliashberg theory. Thus, Pb serves as a benchmark confirming the validity of the adiabatic approximation in conventional superconductors.

Overall, our findings demonstrate that vertex corrections are essential for accurately describing superconductivity in materials with strong non-adiabaticity, low carrier density, or sharp features in the DOS, such as high-Tc hydrides, while validating their negligible influence in conventional adiabatic superconductors. The computational framework established here provides a rigorous and predictive first-principles methodology for extending the applicability of Eliashberg theory beyond the conventional Migdal limit.

Methods

Derivation of the isotropic self-energy expression

The self-energy expression given by Eq. (17) couples electronic states with momenta k. To derive the isotropic equations, we simplify the nk-dependence by defining the energy-resolved average of a quantity Ank as7

Here, \(N(\varepsilon )=\mathop{\sum}\nolimits _{n{\bf{k}}}\delta ({\varepsilon }_{n{\bf{k}}}-\varepsilon )\) denotes the electronic density of states (DOS) per spin at energy ε.

Using Eq. (51), the isotropic form of adiabatic self-energy \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{(A)}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\) from Eq. (22) simplifies to

To express this in terms of energy-resolved quantities, we insert the identity \(\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{-\infty }^{+\infty }d{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\delta ({\varepsilon }_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}}-{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })=1\) into the right-hand side (RHS) of Eq. (52), leading to

In the second line of Eq. (53), we have inserted the factor \(\frac{N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })}{N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })}\) to facilitate simplification. To proceed, we define a double average over k and k + q on the RHS of Eq. (53) as follows

This approximation allows us to decouple the integration over the electron–phonon (e–ph) kernel and the electron Green’s function in the energy domain. Following Allen and Mitrović8, we neglect the energy dependence of the e–ph kernel \(\lambda (\varepsilon,{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} },i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\) and evaluate it at the Fermi level:

This approximation is justified by the assumption that only electronic states near Fermi level (εF) contribute significantly to the e–ph interaction; that is, δ(εnk − ε) → δ(εnk − εF). Furthermore, the k-dependence of Green’s function \({\hat{G}}_{n{\bf{k}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\) (see Eq. (11)) enters through the band energy εnk. Thus, the dominant \({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\) dependence of the energy-resolved Green’s function \(\hat{G}({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} },i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\) arises from the explicit appearance of \({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\). Substituting these approximations into Eq. (53), we obtain the isotropic adiabatic self-energy:

Here, the isotropic e–ph kernel \(\lambda (i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}}})\) is defined as

where α2F(ω) is the isotropic (double-averaged) Eliashberg spectral function expressed as follows:

We now follow similar steps to define the isotropic average of the non-adiabatic self-energy \({\hat{\Sigma }}_{n{\bf{k}}}^{{\rm{(NA)}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\) from Eq. (26) as follows:

In the second step, we insert the identities \(\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{-\infty }^{+\infty }d{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\delta ({\varepsilon }_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}}-{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })=1\), \(\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{-\infty }^{+\infty }d({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })\delta ({\varepsilon }_{l{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}+{\bf{p}}}-({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }))=1\), and \(\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{-\infty }^{+\infty }d{\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime}\delta({\varepsilon}_{p{\bf{k}}+{\bf{p}}}-{\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime})=1\) into the RHS of Eq. (59) to get

where we introduced \(\frac{N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime})N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })}{N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime})N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })}\) for simplification. As in the adiabatic case, we decouple the integration over the e–ph kernel and the electron Green’s function to further simplify the expression. For this purpose, we define the energy-averaged over the RHS of Eq. (60) as follows:

As before, we assume that only electronic states close to the Fermi surface contribute to the integral in Eq. (61) (i.e., δ(εnk − ε) → δ(εnk − εF), \(\delta ({\varepsilon }_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}}-{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })\to \delta ({\varepsilon }_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{F}}})\), δ(εpk+p − ε′′) → δ(εpk+p − εF), and \(\delta ({\varepsilon }_{l{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}+{\bf{p}}}-({\varepsilon}^{\prime\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }))\to \delta ({\varepsilon }_{l{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}+{\bf{p}}}-{\varepsilon }_{{\rm{F}}})\)) and neglect the energy dependence of the vertex-corrected e–ph kernel λV. Thus,

Furthermore, as discussed in the adiabatic case, Green’s function depends on nk only through the band energy εnk (see Eq. (11)), so the dominant ε dependence of energy-resolved Green’s function \(\hat{G}(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j})\) arises from the explicit appearance of ε. Therefore, the isotropic non-adiabatic self-energy Eq. (60) simplifies to

where the isotropic vertex corrections to the e–ph kernel \({\lambda}^{{\rm{V}}}(i{\omega}_{j}-i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}}},i{\omega }_{j}-i{\omega}_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}})\) is given by Eq. (32).

Symmetry reduction of the vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function

We exploit the invariance of isotropic vertex-corrected Eliashberg spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) in Eq. (34) under the exchange \(({\bf{q}},\nu,\omega )\leftrightarrow ({\bf{p}},\mu,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\), which can be understood by examining the corresponding Feynman diagram. The vertex-corrected process, shown in Fig. 1b, involves four electron lines connected by two phonon propagators \({D}_{{\bf{q}}\nu }^{0}\) and \({D}_{{\bf{p}}\mu }^{0}\). Exchanging the roles of these two phonons in the diagram yields a topologically equivalent physical process, as the electron loop remains closed and the same four electronic states participate in the scattering. This symmetry transformation does not result in a loss of generality due to the complete summation of all phonon modes and electronic states. Under this exchange, the spectral function can be written as

Applying the Hermitian property of the e–ph matrix elements, \({g}_{m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}},n{\bf{k}}}^{{\bf{q}}\nu }={\left[{g}_{n{\bf{k}},m{\bf{k}}+{\bf{q}}}^{-{\bf{q}}\nu }\right]}^{* }\), the second term becomes

Since the vertex-corrected spectral function \({\alpha }^{2}{F}^{{\rm{V}}}(\omega,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\) must be real-valued as it represents a physical observable, we can combine the original term and its complex conjugate to obtain

This symmetry-reduced expression allows us to disregard the phase factor in the product of e–ph matrix elements, thereby reducing the computational cost by summing only over identical triplets (q, ν, ω) and \(({\bf{p}},\mu,{\omega }^{{\prime} })\), and eliminating duplicate contributions without loss of physical content.

Simplification of the vertex-corrected self-energy within Eliashberg formalism

The interacting Green’s function \({\hat{G}}_{n{\bf{k}}}(i{\omega }_{j})\), given in Eq. (11), can be written under the isotropic approximation as

where the isotropic non-interacting Green’s function \({\hat{G}}^{0}(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j})\) reduces to

Substituting Eq. (68) and the self-energy expression from Eq. (36) into Eq. (67), we obtain the Dyson equation

Inverting this 2 × 2 matrix, we obtain

where

Using the definitions of γZ(ε, iωj), γχ(ε, iωj), and γϕ(ε, iωj), as given in Eq. (44), Green’s function in Eq. (70) reduces to

To simplify the product \({\hat{\tau }}_{3}\hat{G}(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j}){\hat{\tau }}_{3}\) in Eq. (72), we use

The Pauli matrices obey the identity,

where ϵijk is the Levi-Civita symbol. Using these algebraic relations, we simplify the triple product of Green’s functions in Eq. (31) as follows:

where the coefficients a0, a1, and a2 are given by

Here, for brevity, we define \({\gamma }_{1}^{Z/\chi /\phi }\equiv {\gamma }_{1}^{Z/\chi /\phi }({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} },i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\), \({\gamma }_{2}^{Z/\chi /\phi }\equiv {\gamma }_{2}^{Z/\chi /\phi }({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} },i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}}-i{\omega }_{j}+i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }})\), and \({\gamma }_{3}^{Z/\chi /\phi }\equiv {\gamma }_{3}^{Z/\chi /\phi }({\varepsilon }^{{\prime}\prime},i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}})\). Finally, we note that the \({\hat{\tau }}_{2}\) component is neglected because the functions ϕ(ε, iωj) and \(\bar{\phi }(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j})\) are proportional within an arbitrary phase. Without loss of generality, we set the relative phase such that \(\bar{\phi }(\varepsilon,i{\omega }_{j})=0\)8,13,47,57.

Following the standard Eliashberg procedure, we equate the coefficients of \({\hat{\tau }}_{0}\), \({\hat{\tau }}_{3}\), and \({\hat{\tau }}_{1}\) in the self-energy expressions (Eqs. (56) and (63)) to obtain the self-consistent Eliashberg equations for Z(iωj), χ(iωj), and ϕ(iωj), which are given in Eqs. (37)-(39).

Summation procedure over Matsubara frequencies

In the imaginary-time formalism of finite-temperature quantum field theory, Matsubara frequencies arise from the Fourier transformation of time-dependent correlation functions. For fermions, the Matsubara frequencies are given by

where j is an integer and T is the temperature. For bosons, the corresponding Matsubara frequencies are even, as given by the formula

The self-energy expressions involve summations over fermionic and bosonic Matsubara frequencies associated with electronic and phononic Green’s functions, respectively. In practical calculations, these infinite sums are truncated by introducing a cutoff frequency ωc, typically chosen to be ten times the maximum phonon frequency to ensure convergence of the Eliashberg equations.

The fermionic Matsubara summation is performed over the range j ∈ [−Nc − 1, Nc], where the cutoff index Nc is defined as

Owing to the even symmetry of the phonon propagator \({D}_{{\bf{q}}\nu }(i{\tilde{\omega }}_{l})=2{\omega }_{{\bf{q}}\nu }/[{(i{\tilde{\omega }}_{l})}^{2}-{\omega }_{{\bf{q}}\nu }^{2}]\) and the resulting structure of the Eliashberg equations, the self-energy components Z(iωj), χ(iωj), and ϕ(iωj) are even functions of the Matsubara index j. This allows for efficient summation by exploiting the identity ω−j = −ωj−1 and regrouping terms with appropriate sign conventions.

As an example, we demonstrate this procedure for the adiabatic contribution to the mass renormalization function Z(A)(iωj) from Eq. (37).

Splitting the sum into negative and non-negative components, we obtain

For the negative indices (\({j}^{{\prime} } < 0\)), substituting \({j}^{{\prime} }\to -{j}^{{\prime} }-1\) maps the sum over \({j}^{{\prime} }\in [-{N}_{c}-1,-1]\) to \({j}^{{\prime} }\in [0,{N}_{c}]\):

A similar approach can be applied to the Matsubara summations for other quantities, including ϕ(A)(iωj), χ(A)(iωj), Ne and the terms corresponding to the non-adiabatic vertex corrections. This transformation ensures that all summations are evaluated over positive Matsubara frequencies only, thereby simplifying the numerical implementation.

Derivation of the isotropic Fermi-surface restricted expressions

We further simplify the isotropic Eliashberg equations by assuming the constant density of states, i.e., \(N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })\to {N}_{{\rm{F}}}\). Under this assumption, the adiabatic self-energy in Eq. (56) becomes

We now perform the integral over \({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\) analytically. The poles of Green’s function are

Using the contour integration identity \(\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{-\infty }^{\infty }\frac{dx}{{x}^{2}+{a}^{2}}=\frac{\pi }{a}\) and noting that the integrand term involving \(({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }-{\mu }_{{\rm{F}}}+\chi )\) is odd in \({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\) in the upper-half plane, the relevant integrals reduce to

where we define

Substituting these results into Eq. (83), the adiabatic self-energy under the FSR limit simplifies to

We now turn to the non-adiabatic self-energy in Eq. (63), again assuming \(N({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })\to {N}_{{\rm{F}}}\), \(N(\varepsilon^{\prime\prime})\) → NF, and \(N({\varepsilon }^{\prime\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} })\to {N}_{{\rm{F}}}\), with μF constant, the expression becomes

For brevity, we introduce the shorthand notation \(i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime{\prime}}}=i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime}\prime}}-i{\omega }_{j}+i{\omega }_{{j}^{{\prime} }}\). Performing the analytical integrals over \({\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\), \(\varepsilon^{\prime\prime}\) and \({\varepsilon }^{\prime\prime}-\varepsilon +{\varepsilon }^{{\prime} }\) in Eq. (88), the χ term vanishes since it is an odd function in energy. The integrand is solved using a similar approach as described in Eq. (85), yielding

Thus, the total self-energy within the isotropic FSR approximation is the sum of the adiabatic term in Eq. (87) and the non-adiabatic term in Eq. (89). Following the standard procedure, we match the coefficients of \({\hat{\tau }}_{0}\) and \({\hat{\tau }}_{1}\) in the total self-energy. Equating \({\hat{\tau }}_{0}\) terms, we obtain the expression for Z(iωj):

Similarly, matching \({\hat{\tau }}_{1}\) coefficients gives the expression for ϕ(iωj):

where \(\tilde{\gamma }\), \({\tilde{P}}^{Z}\) and \({\tilde{P}}^{\phi }\) expressions are given by Eqs. (48) and (49).

Computational details

We employed the Quantum ESPRESSO (QE) package101 with optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials (ONCVPSP)102 from Hamman’s library generated with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof parametrization103. We used plane-wave cutoffs of 60 and 100 Ry, a Methfessel-Paxton smearing104 value of 0.01 Ry, and Γ-centered k-grids of 24 × 24 × 24 and 16 × 16 × 16 to describe the electronic structure of H3S and Pb, respectively. The lattice parameters and atomic positions were relaxed until the total energy was converged within 10−6 Ry and the maximum force on each atom was less than 10−4 Ry/Å. The dynamical matrices and the linear variation of the self-consistent potential were calculated within DFPT67 on q-meshes of 4 × 4 × 4 and 8 × 8 × 8 for H3S and Pb, respectively.

For H3S at 200 GPa, we carried out a series of convergence tests to ensure the reliability of our phonon calculations. First, we computed the phonon dispersion by varying the q-mesh from 2 × 2 × 2 to 8 × 8 × 8 (see Supplementary Fig. S3). Notably, imaginary modes appear when using a 3 × 3 × 3 q-grid, which are eliminated upon including anharmonic corrections. To reduce computational cost, we examined the convergence of the phonon dispersion with respect to the kinetic energy cutoff by lowering it from 100 Ry to 60 Ry. The results in Supplementary Fig. S3 show that a 60 Ry cutoff yields converged phonon frequencies and is therefore used throughout this work.

We computed the anharmonic phonons for H3S with the anharmonic special displacement method (A-SDM)62,105 implemented in the ZG code of EPW56. Calculations were performed for 2 × 2 × 2, 3 × 3 × 3, and 4 × 4 × 4 supercells corresponding to 192, 648, and 1,536 distorted configurations, respectively. A 12 × 12 × 12 k-grid for the primitive unit cell was found to be enough to extract the interatomic force constants (IFCs) for the anharmonic phonon dispersions, drastically reducing the computational cost (see Supplementary Fig. S4). For the anharmonic calculations, convergence was verified with respect to both the atomic displacement amplitude and the supercell size, as detailed in Supplementary Section III (see Figs. S4 and S5). All anharmonic calculations presented here were performed at 0 K. We have also performed anharmonic calculations at 200 K and 500 K. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S6, the phonon dispersion at 200 K remains virtually identical to that at 0 K, while at 500 K only minor shifts appear in the high-frequency H modes. These results confirm that temperature has a negligible effect on the phonon spectra at this pressure, consistent with previous findings59.

The EPW code13,55,56,65 was used to investigate e–ph interactions and superconducting properties. The electronic wavefunctions required for the Wannier interpolation106,107,108 were obtained on a uniform Γ-centered 8 × 8 × 8 k-grid. For H3S, we used ten atom-centered orbitals to describe the electronic structure, with one s orbital for each H atom and five s, p, dxy, dxz, dyz orbitals for the S atom, while for Pb we used four sp3 orbitals. The isotropic Eliashberg spectral functions were computed using uniform 48 × 48 × 48 k- and 24 × 24 × 24 q-point grids for electrons and phonons, respectively. The isotropic Eliashberg equations were solved on the imaginary Matsubara frequency axis, using an energy cutoff of 2.5 eV for H3S and 1 eV for Pb. Dirac delta functions for electrons and phonons were approximated by Gaussians with widths of 50 meV and 2.5 meV for H3S, and 50 meV and 0.15 meV for Pb. In the case of H3S, the DOS, e–ph coupling, and superconducting gap are highly sensitive to the position of the Fermi level due to the vHs located near εF. To ensure consistency and numerical accuracy, εF was set to the value obtained from EPW calculations using a 48 × 48 × 48 k-grid for both H3S and Pb. In addition, we found that to achieve convergence of the superconducting gap and critical temperature in the FBW calculations, an energy window of at least 1 eV for H3S and Pb is required when computing the DOS.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Additional data are deposited in the figshare database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30122905. Data and information not included in these sources are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

All calculations are performed using the open-source QUANTUM ESPRESSO v7.3 package (available at https://www.quantum-espresso.org) and its EPW module. The vertex-correction routines used in this work are implemented in a private development branch of EPW and are not yet included in the public release. The modified source code is available from the authors upon reasonable request and will be incorporated into a future release.

References

Migdal, A.B. Interaction between electrons and lattice vibrations in a normal metal. Sov. Phys. JETP 7, 996–1001 (1958).

Eliashberg, G. Interactions between electrons and lattice vibrations in a superconductor. Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 696–702 (1960).

Eliashberg, G.M. Temperature Green’s function for electrons in a superconductor. Sov. Phys. JETP 12, 1000–1002 (1961).

Carbotte, J.P. Properties of boson-exchange superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 1027–1157 (1990).

Scalapino, D.J., Schrieffer, J.R. & Wilkins, J.W. Strong-Coupling Superconductivity. I. Phys. Rev. 148, 263–279 (1966).

Scalapino, D. J. The Electron-phonon Interaction and Strong-coupling Superconductors (ed Parks, R. D.) Vol. 1, 449–560 (Dekker, 1969).

Pickett, W.E. Generalization of the theory of the electron-phonon interaction: thermodynamic formulation of superconducting- and normal-state properties. Phys. Rev. B 26, 1186–1207 (1982).

Allen, P. B. & Mitrović, B. Theory of Superconducting Tc. Solid State Physics Vol. 37, 1–92 (Academic Press, 1983)https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0081194708606657.

Marsiglio, F. & Carbotte, J. Electron-phonon Superconductivity 73–162 (Springer, 2008).

Marsiglio, F. Eliashberg theory: a short review. Ann. Physics 417, 168102 (2020).

Pickett, W.E. Colloquium: Room temperature superconductivity: the roles of theory and materials design. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 021001 (2023).

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L.N. & Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

Poncé, S., Margine, E.R., Verdi, C. & Giustino, F. EPW: Electron-phonon coupling, transport and superconducting properties using maximally localized Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 209, 116–133 (2016).

Sanna, A., Pellegrini, C. & Gross, E.K.U. Combining eliashberg theory with density functional theory for the accurate prediction of superconducting transition temperatures and gap functions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 057001 (2020).

Marini, G. et al. EPIQ: An open-source software for the calculation of electron-phonon interaction related properties. Comput. Phys. Commun. 295, 108950 (2024).

Marques, M.A.L. et al. Ab initio theory of superconductivity. II. Application to elemental metals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024546 (2005).

Arita, R. et al. Nonempirical calculation of superconducting transition temperatures in light-element superconductors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1602421 (2017).

Sanna, A. et al. Ab initio Eliashberg theory: making genuine predictions of superconducting features. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 041012 (2018).

Davydov, A. et al. Ab initio theory of plasmonic superconductivity within the Eliashberg and density-functional formalisms. Phys. Rev. B 102, 214508 (2020).

Flores-Livas, J.A., Sanna, A. & Gross, E. High temperature superconductivity in sulfur and selenium hydrides at high pressure. Eur. Phys. J. B 89, 1–6 (2016).

Pellegrini, C. & Sanna, A. Ab initio methods for superconductivity. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 509–523 (2024).

Born, M. & Oppenheimer, R. Zur quantentheorie der molekeln. Ann. Physik 389, 457–484 (1927).

Jarlborg, T. & Bianconi, A. Breakdown of the Migdal approximation at Lifshitz transitions with giant zero-point motion in the H3S superconductor. Sci. Rep. 6, 24816 (2016).

Sano, W., Koretsune, T., Tadano, T., Akashi, R. & Arita, R. Effect of Van Hove singularities on high-Tc superconductivity in H3S. Phys. Rev. B 93, 094525 (2016).

Durajski, A. P. & Szczesniak, R. Migdal-Eliashberg equations—the effective model for superconducting state in H3S. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.06079 (2016).

Gor’kov, L.P. & Kresin, V.Z. Pressure and high-Tc superconductivity in sulfur hydrides. Sci. Rep. 6, 25608 (2016).

Gor’kov, L.P. & Kresin, V.Z. Colloquium: High pressure and road to room temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 011001 (2018).

Roy, B., Sau, J.D. & Das Sarma, S. Migdal’s theorem and electron-phonon vertex corrections in Dirac materials. Phys. Rev. B 89, 165119 (2014).

Gunnarsson, O., Meden, V. & Schönhammer, K. Corrections to Migdal’s theorem for spectral functions: a cumulant treatment of the time-dependent Green’s function. Phys. Rev. B 50, 10462–10473 (1994).

Cappelluti, E., Grimaldi, C., Pietronero, L. & Strässler, S. Nonadiabatic channels in the superconducting pairing of fullerides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4771–4774 (2000).

Gastiasoro, M.N., Chubukov, A.V. & Fernandes, R.M. Phonon-mediated superconductivity in low carrier-density systems. Phys. Rev. B 99, 094524 (2019).

Hu, S.-Q. et al. Nonadiabatic electron-phonon coupling and its effects on superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 105, 224311 (2022).

Gor’kov, L.P. Superconducting transition temperature: Interacting fermi gas and phonon mechanisms in the nonadiabatic regime. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054517 (2016).

Zhang, S.-S., Raines, Z.M. & Chubukov, A.V. Applicability of Eliashberg theory for systems with electron-phonon and electron-electron interaction: a comparative analysis. Phys. Rev. B 109, 245132 (2024).

Talantsev, E.F. Classifying superconductivity in compressed H3S. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 33, 1950195 (2019).

Talantsev, E.F. Universal Fermi velocity in highly compressed hydride superconductors. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 7, 058403 (2022).

Pietronero, L. & Strässler, S. Theory of nonadiabatic superconductivity. Europhys. Lett. 18, 627 (1992).

Kostur, V.N. & Mitrović, B. Electron-phonon interaction in two dimensions: Variation of Im Sigma (epsilon p, omega) with increasing omega D/EF. Phys. Rev. B 48, 16388–16401 (1993).

Kostur, V.N. & Mitrović, B. Calculations of the superconducting critical temperature with vertex corrections. Phys. Rev. B 50, 12774–12787 (1994).

Grimaldi, C., Pietronero, L. & Strässler, S. Nonadiabatic superconductivity: electron-phonon interaction beyond Migdal’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1158–1161 (1995).

Pietronero, L., Strässler, S. & Grimaldi, C. Nonadiabatic superconductivity. I. Vertex corrections for the electron-phonon interactions. Phys. Rev. B 52, 10516–10529 (1995).

Grimaldi, C., Pietronero, L. & Strässler, S. Nonadiabatic superconductivity. II. Generalized Eliashberg equations beyond Migdal’s theorem. Phys. Rev. B 52, 10530–10546 (1995).

Botti, M., Cappelluti, E., Grimaldi, C. & Pietronero, L. Nonadiabatic theory of the superconducting state. Phys. Rev. B 66, 054532 (2002).

Pietronero, L. & Cappelluti, E. Nonadiabatic breakdown and pairing in high-Tc compounds. Low Temp. Phys. 32, 340–358 (2006).

Velasco, V., Midei, G., Capone, M. & Perali, A. Pairing amplification induced by nonadiabatic effects on the electron-phonon interaction throughout the BCS-BEC crossover. Phys. Rev. B 111, 064512 (2025).

Esterlis, I. et al. Breakdown of the Migdal-Eliashberg theory: a determinant quantum Monte Carlo study. Phys. Rev. B 97, 140501 (2018).

Schrodi, F., Oppeneer, P.M. & Aperis, A. Full-bandwidth Eliashberg theory of superconductivity beyond Migdal’s approximation. Phys. Rev. B 102, 024503 (2020).

Lee, N.-E., Zhou, J.-J., Chen, H.-Y. & Bernardi, M. Ab initio electron-two-phonon scattering in GaAs from next-to-leading order perturbation theory. Nat. Commun. 11, 1607 (2020).

Bianco, R. & Errea, I. Non-perturbative theory of the electron-phonon coupling and its first-principles implementation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.02621 (2023)

Houtput, M. et al. First-principles theory of nonlinear long-range electron-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. B 111, 184320 (2025).

Zappacosta, I., Houtput, M. & Tempere, J. Nonlinear electron-phonon interactions in the Migdal-Eliashberg theory. Phys. Rev. B 111, 214525 (2025).

Lihm, J.-M. & Poncé, S. Nonperturbative self-consistent electron-phonon spectral functions and transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 186401 (2025).

Freericks, J.K., Nicol, E.J., Liu, A.Y. & Quong, A.A. Vertex-corrected tunneling inversion in electron-phonon mediated superconductors: Pb. Phys. Rev. B 55, 11651–11658 (1997).

Durajski, A.P. Quantitative analysis of nonadiabatic effects in dense H3S and PH3 superconductors. Sci. Rep. 6, 38570 (2016).

Margine, E.R. & Giustino, F. Anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg theory using Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 87, 024505 (2013).

Lee, H. et al. Electron-phonon physics from first principles using the EPW code. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 2057–3960 (2023).

Lucrezi, R. et al. Full-bandwidth anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg theory and its application to superhydrides. Commun. Phys. 7, 33 (2024).

Hilleke, K.P. & Zurek, E. Tuning chemical precompression: theoretical design and crystal chemistry of novel hydrides in the quest for warm and light superconductivity at ambient pressures. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 070901 (2022).

Errea, I. et al. High-pressure hydrogen sulfide from first principles: a strongly anharmonic phonon-mediated superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 157004 (2015).

Taureau, R., Cherubini, M., Morresi, T. & Casula, M. Quantum symmetrization transition in superconducting sulfur hydride from quantum Monte Carlo and path integral molecular dynamics. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 56 (2024).

Nambu, Y. Quasi-particles and gauge invariance in the theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 117, 648–663 (1960).

Zacharias, M., Volonakis, G., Giustino, F. & Even, J. Anharmonic lattice dynamics via the special displacement method. Phys. Rev. B 108, 035155 (2023).

Heid, R. Relevance of quadratic electron-phonon coupling for the superconducting transition temperature. Phys. Rev. B 45, 5052–5054 (1992).

Dee, P.M., Coulter, J., Kleiner, K.G. & Johnston, S. Relative importance of nonlinear electron-phonon coupling and vertex corrections in the Holstein model. Comm. Phys. 3, 145 (2020).

Giustino, F., Cohen, M.L. & Louie, S.G. Electron-phonon interaction using Wannier functions. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165108 (2007).

Giustino, F. Electron-phonon interactions from first principles. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015003 (2017).

Baroni, S., Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001).

Gor’Kov, L. On the energy spectrum of superconductors. Sov. Phys. JETP 7, 158 (1958).

Schrieffer, J. R. Theory of Superconductivity (CRC Press, 1999).

Mahan, G.D. Many-particle Physics (Plenum, 1993).

Hedin, L. New method for calculating the one-particle Green’s function with application to the electron-gas problem. Phys. Rev. 139, 796–823 (1965).

Hybertsen, M.S. & Louie, S.G. Electron correlation in semiconductors and insulators: band gaps and quasiparticle energies. Phys. Rev. B 34, 5390–5413 (1986).

Pellegrini, C., Kukkonen, C. & Sanna, A. Ab initio calculations of superconducting transition temperatures: when going beyond RPA is essential. Phys. Rev. B 108, 064511 (2023).

Mori, H., Nomoto, T., Arita, R. & Margine, E.R. Efficient anisotropic Migdal-Eliashberg calculations with an intermediate representation basis and Wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 110, 064505 (2024).

Kogler, E. et al. IsoME: Streamlining high-precision Eliashberg calculations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 315, 109720 (2025).

Morel, P. & Anderson, P.W. Calculation of the superconducting state parameters with retarded electron-phonon interaction. Phys. Rev. 125, 1263–1271 (1962).

Allen, P.B. & Dynes, R.C. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors reanalyzed. Phys. Rev. B 12, 905–922 (1975).

Cappelluti, E. & Pietronero, L. Electron-phonon interaction and breakdown of the adiabatic principle in fullerides and MgB2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 67, 1941–1947 (2006).

Heid, R. in Electron-phonon Coupling. Lecture Notes of the Autumn School on Correlated Electrons (eds Pavarini, E. et al.) 399–427 (2017).

Szabó, P. et al. Evidence for two superconducting energy gaps in MgB2 by point-contact spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 137005 (2001).

Tomassetti, C.R., Kafle, G.P., Marcial, E.T., Margine, E.R. & Kolmogorov, A.N. Prospect of high-temperature superconductivity in layered metal borocarbides. J. Mater. Chem. C 12, 4870–4884 (2024).

Margine, E., Lambert, H. & Giustino, F. Electron-phonon interaction and pairing mechanism in superconducting Ca-intercalated bilayer graphene. Sci. Rep. 6, 21414 (2016).

Mishra, S.B., Marcial, E.T., Debata, S., Kolmogorov, A.N. & Margine, E.R. Stability-superconductivity map for compressed Na-intercalated graphite. Phys. Rev. B 110, 174508 (2024).

Heil, C. et al. Origin of superconductivity and latent charge density wave in NbS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 087003 (2017).

Das, S., Paudyal, H., Margine, E.R., Agterberg, D.F. & Mazin, I.I. Electron-phonon coupling and spin fluctuations in the Ising superconductor NbSe2. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 66 (2023).

Duan, D. et al. Pressure-induced metallization of dense (H2S)2H2 with high-Tc superconductivity. Sci. Rep. 4, 6968 (2014).

Bernstein, N., Hellberg, C.S., Johannes, M.D., Mazin, I.I. & Mehl, M.J. What superconducts in sulfur hydrides under pressure and why. Phys. Rev. B 91, 060511 (2015).

Quan, Y. & Pickett, W.E. Van Hove singularities and spectral smearing in high-temperature superconducting H3S. Phys. Rev. B 93, 104526 (2016).

Akashi, R. Archetypical “push the band critical point” mechanism for peaking of the density of states in three-dimensional crystals: theory and case study of cubic H3S. Phys. Rev. B 101, 075126 (2020).

Thomsen, S.R. & Goesten, M.G. Symmetry-SHaped Singularities in High-temperature Superconductor H3S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18298–18305 (2024).

Mozaffari, S. et al. Superconducting phase diagram of H3S under high magnetic fields. Nat. Commun. 10, 2522 (2019).

Drozdov, A.P., Eremets, M.I., Troyan, I.A., Ksenofontov, V. & Shylin, S.I. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature 525, 73–76 (2015).

Nakao, H. et al. Superconductivity of pure H3S synthesized from elemental sulfur and hydrogen. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 88, 123701 (2019).

Du, F. et al. Superconducting gap of H3S measured by tunnelling spectroscopy. Nature 641, 619–624 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Accurate Electron-phonon Interactions from Advanced Density Functional Theory Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.08192 (2024).

Aynajian, P. et al. Energy gaps and Kohn anomalies in elemental superconductors. Science 319, 1509–1512 (2008).

Liu, A.Y. & Quong, A.A. Linear-response calculation of electron-phonon coupling parameters. Phys. Rev. B 53, 7575–7579 (1996).

Heid, R., Bohnen, K.-P., Sklyadneva, I.Y. & Chulkov, E.V. Effect of spin-orbit coupling on the electron-phonon interaction of the superconductors Pb and Tl. Phys. Rev. B 81, 174527 (2010).

Townsend, P. & Sutton, J. Investigation by electron tunneling of the superconducting energy Gaps in Nb, Ta, Sn, and Pb. Phys. Rev. 128, 591–595 (1962).

Khasanov, R., Das, D., Gawryluk, D.J., Gupta, R. & Mielke, C. Isotropic single-gap superconductivity of elemental Pb. Phys. Rev. B 104, 100508 (2021).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Hamann, D.R. Optimized norm-conserving Vanderbilt pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 88, 085117 (2013).

Perdew, J.P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Methfessel, M. & Paxton, A.T. High-precision sampling for Brillouin-zone integration in metals. Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616–3621 (1989).

Zacharias, M., Giustino, F. Theory of the special displacement method for electronic structure calculations at finite temperature. Phys. Rev. Res. 2 (2020).

Marzari, N., Mostofi, A.A., Yates, J.R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions: Theory and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1419–1475 (2012).

Pizzi, G. et al. Wannier90 as a community code: new features and applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 165902 (2020).

Marrazzo, A. et al. Wannier-function software ecosystem for materials simulations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 045008 (2024).

Einaga, M. et al. Crystal structure of the superconducting phase of sulfur hydride. Nat. Phys. 12, 835–838 (2016).

Acknowledgements