Abstract

Chemical space is vast, and the space of physical properties derived from it even more so. Despite over a century of physical chemistry measurements, we still lack large, well-organised data sets of key physical properties such as the interfacial tension of surfactant solutions. Access to such data sets is essential to developing the next generation of predictive models for physicochemical properties using modern approaches such as artificial intelligence and machine learning (ML). Thus, we require experimental methods which can efficiently provide large, reproducible and informative data sets. In this work, we developed a robotic, automated pendant drop module for the efficient characterisation of the interfacial properties of surfactant-containing solutions. Provided with surfactant stock solutions, the module measures a surface tension isotherm, from which multiple important physical properties can be determined, including the critical micelle concentration and the maximum surface excess concentration. The module handles critical experimental challenges and decisions such as choosing an appropriate drop volume, detecting failed measurements and selecting concentration points to measure. To obtain a maximally informative dataset, the platform leverages an active learning algorithm combining Bayesian inference and mutual information to dynamically design experiments in response to collected data. We validate the platform by characterising a range of surfactants and demonstrate the effectiveness of its capabilities by mapping the surface tension of binary surfactant mixtures. This module lays the foundation for efficiently and autonomously generating informative datasets of the interfacial properties of surfactant formulations, paving the way to the next generation of ML models for the prediction of formulation properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Surfactants play a crucial role in a wide range of everyday products and industrial applications1,2. They are used in detergents3, microfluidic devices4, pharmaceuticals5 and food products6, among others, to stabilise emulsions, reduce surface tension and modify the wetting properties of surfaces. Individual surfactants are predominantly characterised by parameters such as critical micelle concentration (CMC), surface tension at the CMC (γcmc), and maximum surface excess concentration (Γmax). However, most formulation applications contain mixtures of surfactants, as well as additives such as salts, polymers or hydrotropes. Predicting the interfacial tension properties of these solutions is challenging due to their complexity and the lack of available data reporting on them. There is growing interest in employing machine learning models to predict surfactant properties7,8,9, but these have thus far been trained on solutions of a single surfactant in pure water. Hence, there is an urgent need to collect comprehensive, high-quality datasets upon which predictive models may be developed.

Several electrochemical, optical, spectroscopic and tensiometric techniques can be employed to characterise the interfacial tension of surfactants10. Tensiometric methods, such as the Du Noüy ring11 or Wilhelmy plate12 based techniques, directly measure the surface tension of air–water interfaces, typically with a precision of 0.1 mN/m13. Despite their precision, these force-based tensiometric techniques are not well suited for implementation in automated systems, requiring large sample volumes, careful cleaning between measurements, and laborious setup. On the other hand, image-based tensiometry methods, such as the pendant drop method, are more amenable to integration into robotic platforms, predominantly because the measurement device, a camera, does not come into contact with the solution, and thus minimises the requirement for cleaning and potential for cross-contamination. Furthermore, the pendant drop method requires only a small amount of sample, on the scale of microlitres, to create a drop, from which surface tension can be determined14.

Complete characterisation of a surfactant’s effect on surface tension requires multiple measurements over varying concentrations. This process is non-trivial and laborious for pendant drop tensiometry, requiring attention to be paid to the measurement process at every step. The experimenter must first select a set of concentrations for measurements that are sufficiently designed to allow accurate determination of key interfacial properties. The concentrations must then be formulated and an appropriate drop volume selected for each concentration measured according to the expected surface tension of the solution. The experimenter then performs the measurement whilst monitoring for erroneous measurements. This process must be repeated for each new surfactant. These challenges are further compounded when determining the properties of mixtures. The combinatorial explosion of possible component combinations, along with the complex, non-linear behaviour of the resulting surface tension landscape, hinders the efficient characterisation of such formulated mixtures.

Recent advances in self-driving labs15,16 have demonstrated the feasibility of closed-loop systems for measuring physical properties, such as solubility17 and viscosity18. Additionally, significant progress has been made in self-driven experimental design, employing active learning algorithms such as Bayesian optimisation to select the most informative experiments and accelerate formulation discovery19,20. However, such fully self-driving approaches have not yet been realised in the field of characterising the interfacial properties of surfactants, where complex interfacial phenomena and mixture behaviours present unique challenges for automation and algorithmic decision-making.

Creating informative experimental designs is challenging for high-dimensional, non-linear systems. Crucially, several theories relating surfactant concentration to surface tension, both for single- and multiple-surfactant solutions are available21,22,23. These theories are based on physical models of formulations containing surfactants, and provide a means to estimate the expected relationship between interfacial tension and solution composition. Thus, they can be used to guide experimental data collection, using their Bayesian variants to map the uncertainty in predictions of surface tension to surfactant concentration. This chemistry-aware approach capitalises on well-established theory as the basis for efficient active learning algorithms which aim to collect data which minimise the uncertainty in an equation’s parameters. This approach contrasts to Gaussian Process-based Bayesian optimisation frameworks widely adopted in chemical investigations24,25,26,27 which aim to find a maximum experimental outcome, such as a reaction yield, using a black-box model.

Here, we introduce an autonomous robotic module capable of efficiently characterising the interfacial tension of both single and binary surfactant solutions. The automated platform (i) ensures surface tension data acquisition with high precision and accuracy, and (ii) selects the most informative data points to measure for the characterisation of key surfactant physical properties.

We validate this module by fully characterising the surface tension isotherms of 11 surfactants, obtaining key physical properties (CMC, γcmc and Γmax) that fall within the ranges reported in the literature. Furthermore, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the platform for efficient, automated data collection by mapping the surface tension of two binary mixtures in which non-ideal behaviour is observed, highlighting the potential of such self-driving approaches to uncover complex behaviour in mixtures.

Results and discussion

Overview of the self-driving pendant drop module

We first provide an overview of the platform’s operation, before describing each of its component processes in detail. The self-driving pendant drop module is built around an Opentrons OT-2 liquid handling robot and integrates a camera for imaging pendant droplets, along with a sensor for monitoring environmental conditions, including temperature and humidity. All components are controlled by a central orchestrator computer, which simultaneously manages instrument coordination, real-time data analysis and the storage of both raw image data and derived physicochemical properties. A schematic overview of the complete module is shown in Fig. 1a, with photographs of the robotic platform provided in Supplementary Fig. S1.

a Illustration of the control and data flow architecture of the robotic platform. The platform is supplied with a surfactant stock solution and sample information by the user. The orchestrator then calculates target concentrations, instructs the robotic system to prepare samples, and performs surface tension measurements by imaging and analysing the pendant drop profile. Based on prior results, a Bayesian model proposes new formulations for measurement. This loop continues for a set number of iterations. Surface tension data, associated images and derived properties are stored in a database. b Plot of a typical surface tension isotherm, with coloured regions indicating physical interpretations of parameters in the Szyszkowski equation. This equation is fitted to experimentally determined surface tension measurements (black crosses), using three fitting parameters: critical micelle concentration (CMC, green), the maximum surface excess concentration (Γmax, orange) and the Langmuir constant (KL, blue).

The module’s objective is to efficiently characterise surfactant solutions by measuring their surface tension isotherms, data reporting on surface tension as a function of surfactant concentration at constant temperature (Fig. 1b). The Szyszkowski equation describes this relationship between surface tension and surfactant concentration (Eq. 1).

Here, \({\gamma }_{{eq}}\) is the air–water surface tension at equilibrium, \({\gamma }_{0}\) is the surface tension of water, \(R\) is the ideal gas constant, \(T\) is the temperature, \({\Gamma }_{\max }\) is the maximum surface excess concentration, \({K}_{L}\) is the Langmuir adsorption constant and \([{S}_{1}]\) is the monomeric surfactant concentration. The monomeric surfactant concentration can be modelled using an equation developed by Al-Soufi et al. (Eq. 5 in Methods) which accounts for the change in free surfactant concentration considering micelle formation and requires the CMC as input parameter28.

Given the surface tension of water at room temperature (73.08 mN/m at 20 °C29), the Szyszkowski equation can be fitted with three key surfactant properties: CMC, Γmax and KL. The CMC represents the concentration at which micelle formation occurs, generally indicated by a plateau in the surface tension isotherm beyond this concentration. Γmax quantifies the maximum adsorption capacity of the surfactant at the air–water interface and is reflected in the slope of the surface tension isotherm prior to micelle formation. Finally, KL corresponds to the equilibrium constant for adsorption and is related to the concentration at which a noticeable reduction in surface tension begins. From these key properties, several additional surfactant properties can be calculated, including γcmc, surface pressure at CMC (πcmc), adsorption efficiency (C20) and the minimum area per surfactant molecule at the air–water interface (Amin).

To characterise a surfactant and obtain the surface tension isotherm, the operator provides a physical surfactant solution, along with specifications of the solution concentration and labware necessary for the experiment (tip racks, water reservoir and well plates). The orchestrator computer calculates sets of solution concentrations for measurement and instructs the robot to prepare them. After sample formulation, the robot picks up a dispensing needle which aspirates a small amount of surfactant solution before dispensing a pendant droplet in front of a camera integrated into the platform. The orchestrator then activates the camera, initiating the recording of droplet images. These images are analysed to extract droplet profiles from which the surface tension is calculated (see below for more details). The platform records surface tension measurements alongside sensor data, including temperature, pressure, and humidity. If required, the orchestrator formulates additional surfactant solutions based on previous surface tension measurements to optimise the collection of data which lower the uncertainty of the CMC, Γmax and KL estimated by the model. This process yields a complete isotherm characterising the variation in solution surface tension with varying solution composition. Upon completion of surfactant characterisation, an informative surface tension isotherm is obtained, describing the surface tension as a function of the bulk surfactant concentration in solution.

Surface tension extraction from pendant drop profiles

To extract surface tension data, the pendant drop images are processed and analysed to extract two parameters: de, the maximum horizontal diameter of the droplet, and ds, the diameter measured at a vertical distance equal to de from the droplet’s bottom edge (see Fig. S2 for the image analysis pipeline). The ratio of these geometric parameters characterises the shape of the droplet and is often referred to as the shape parameter. This shape parameter is converted to the dimensionless shape factor H via consultation of a table of values30. The surface tension (γ) is then calculated using Eq. 2.

Here, \(g\) refers to the gravitational constant and \(\Delta \rho\) refers to the density difference between the droplet and the surrounding medium.

Optimising surface tension measurement precision via adaptive drop volume

To ensure precise and accurate surface tension measurements of diluted surfactant solutions, the robotic platform is designed to make a series of intelligent, self-driving decisions. The first of these decisions is to choose a drop volume which is appropriate for measuring the surface tension of the solution. Dispensed drop volumes should be as large as possible. However, if the drop is too large, it will detach from the needle due to the force of gravity.

The robotic module selects an optimal droplet volume via an iterative process (Fig. 2a) which aims to optimise the Worthington number (\({Wo}\)), a dimensionless parameter defined as the ratio of the actual droplet volume (\({V}_{{droplet}}\)) to the theoretical maximum volume (\({V}_{\max }\), Eq. 3), which quantifies balance between droplet size and gravitational stability14.

a Schematic of the closed-loop process for selecting the optimal droplet volume. A pendant drop is initially formed by dispensing a small volume (Vdroplet) from a needle with a known diameter (Dneedle). Subsequently, the Worthington number (Wo) is calculated. If Wo is below a given threshold, more solution is dispensed. This process is iterated in a loop until the given Wo threshold is reached and the surface tension measurement is initiated. b Example time course of a surface tension measurement for a solution of C12E4 at 46 µM and 23 °C. Surface tension measurements for each drop are determined from the plateau region of the time course (annotated by \({\gamma }_{{eq}}\)).

Equation 4 gives the maximum droplet volume (\({V}_{\max }\)) for a given needle diameter (\({D}_{n}\)).

Here, \(\gamma\) is the apparent surface tension, \(\Delta \rho\) is the density difference between the droplet and the surrounding medium and \(g\) is the gravitational constant. The apparent surface tension may be estimated from the drop profile, although this approach is less accurate when the droplet volume substantially deviates from \({V}_{\max }\). Nevertheless, it provides a reasonable approximation for calculating the Worthington number, given the known droplet volume (as dispensed by the robotic pipette) and the needle diameter. Droplets with a Worthington number of 0.6 or higher result in more precise surface tension measurements14. To that end, the module incrementally dispenses the surfactant solution until this threshold is reached (see Methods for the procedure and Fig. S3), and a surface tension measurement is started.

During measurement, the surface tension of the pendant droplet is continually monitored by analysing each frame of the video feed from the camera. These measurements capture the droplet’s dynamic behaviour over a predefined measurement period (Fig. 2b). We observed that surface tension can change significantly over time in the first phase of the measurement, with a rate depending on the surfactant. To account for these interfacial dynamics, the measurement duration is set between 1 and 15 min, with times selected based on prior scoping experiments. The surface tension reported by the platform is determined from the equilibrium region of the surface tension–time curve. If a droplet falls from the needle during measurement, the orchestrator detects this event and automatically generates a new droplet with a slightly reduced volume. This adjustment helps prevent premature detachment and ensures successful completion of the measurement cycle.

With these droplet measurement procedures in place, the robotic module can perform precise and reproducible surface tension measurements without any human intervention. To assess its precision and accuracy, the surface tension of both water and a surfactant solution of 34 mM sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) were measured 24 times (Fig. S4a). Standard deviations of 0.07 mN/m and 0.22 mN/m were obtained for the water sample and SDS sample, respectively, which match literature values31,32 (deviations of +0.8% and −2.1%, respectively). Furthermore, the precision of the experimentally obtained surface tension isotherm is evaluated (Fig. S4b), and its accuracy is assessed by comparing it to a surface tension isotherm measured using Du Noüy ring tensiometry (Methods and Fig. S4c).

Efficient, informative data collection via Bayesian inference

We next considered how to efficiently drive autonomous data collection in the module by minimising the number of concentration points needed to characterise the surface tension isotherm. We developed an active learning process consisting of two phases, beginning with exploration, which is performed via grid-sampling, followed by exploitation, in which data points are selected based on the mutual information between the inferred distributions of the parameters CMC, Γmax and KL and surface tension. In the exploration phase, the platform performs a set of dilutions in which the stock solution is serially diluted eight times by a factor of two, resulting in a final concentration that is 1/128th of the original. The stock concentration is selected near the solubility limit to ensure that at least some measurements fall within a concentration range exceeding CMC. These ‘explore’ points are subsequently used to initialise the active learning algorithm for the exploitation phase.

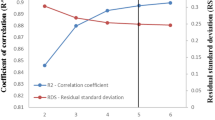

In the exploitation phase, a Hamiltonian Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm is used to infer posterior distributions of the fitting parameters (CMC, Γmax and KL) and dependent variable (surface tension) in the Szyszkowski equation (Eq. 1). During the active learning step, data points that fall outside two standard deviations of the posterior predictive distribution of surface tensions are excluded as input for the active learning algorithm. However, all recorded data were manually inspected and included in a data set for further analysis (complete data is available on Zenodo33). The posterior distributions are then used to determine which concentrations would be most informative in reducing their uncertainty. To find this most informative concentration, the mutual information is calculated between the posterior distribution of the fitting parameters and the posterior distribution of the surface tension across a continuous range of surfactant concentrations. The concentration that yields the highest total mutual information is identified as the most informative (Fig. 3a) and is passed to the orchestrator for formulation.

a Surface tension isotherm of SDS, measured at 23°C, including eight experimental points of the explore phase and a fit based on the Szyszkowski equation, using the maximum likelihood estimates for parameters as determined by Bayesian inference. The mutual information is given for each fitting parameter as a function of surfactant concentration, including the sum over all parameters. The concentration corresponding to the maximum mutual information is formulated for measurement the exploit phase. b Illustration of decreasing model uncertainty per active learning cycle based on simulated data.

To reduce experimental error and increase material efficiency, the orchestrator automatically determines how to prepare the requested concentration by identifying a previously formulated sample which is closest, but higher in concentration than the target sample. The target sample is then made via a one-step dilution of the existing sample. This approach minimises the need for multiple pipetting steps and pipetting very small volumes, thereby reducing the potential for experimental error. Once formulated, the surface tension of the new dilution is measured, and the process is repeated. Typically, this cycle is performed three times, although the number of iterations can be adjusted as required, decreasing the uncertainty of the fitting parameters rapidly (Fig. 3b).

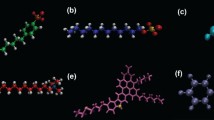

Characterisation of solutions containing a single surfactant

To demonstrate the validity of the self-driven module, 11 surfactant isotherms were measured in triplicate (see Fig. 4 for six examples, Table 1 for determined properties for each surfactant). Each characterisation run was performed with two to four exploit points except for the non-ionic polyethoxylates C12E3 and C12E4. For these surfactants, exploit points were not collected due to their slow surface tension equilibration times. The time taken for measurement made it challenging to formulate reliable exploit points, most likely because the concentration of previously prepared samples (used for formulating the exploit points) changed over time due to evaporation. The interfacial property parameters were determined by fitting Eq. 1 to the data (see Methods for more information). The time taken to characterise each reported surfactant is given in Table 1, ranging from 90 min to 4 h. This time difference is primarily attributed to variations in the pendant drop measurement time. For instance, some surfactant solutions, such as those containing polyethoxylates, have slow equilibration times, thus necessitating longer wait periods before an equilibrium surface tension measurement to be made. These equilibration times place limitations on the throughput rate of the platform which are dependent on the type of surfactant used. Literature values are reported for comparison in Table 1 if available, otherwise estimates were calculated using a previously reported graph neural network (GNN) trained on the SurfPro database (see Methods for the procedure)9.

Overall, the experimentally determined properties generally agree well with literature values, except for TTAB. Some of the measured surface tensions of TTAB immediately below CMC are lower than after CMC, resulting in a ‘dip’ in surface tension (Fig. S5). This anomaly is typically attributed to impurities34 and results in erroneous fit of the Szyszkowski equation, and inaccurate determination of surfactant properties. Furthermore, we note that the standard deviation in the determined Γmax values for C12E3 and C12E4 is higher in comparison to the other surfactants. This discrepancy is most likely due to omission of the exploit phase as described above. The agreement between experimentally determined properties and the corresponding predictions from the GNN model trained on SurfPro varies depending on the surfactant and property. This variability highlights the need for additional experimental data in the SurfPro database and, consequently, the importance of developing an autonomous characterisation platform.

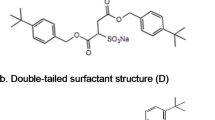

Characterisation of binary surfactant solutions

Having validated the ability of the platform to autonomously collect precise and accurate data on the surface tension isotherm of single-surfactant solutions, we next investigated its data collection abilities for binary binary surfactant mixtures. In most formulation applications, solutions are made using two or more surfactants to optimise stability, viscosity, material use or cost. Mixed surfactants frequently show synergistic or antagonistic interactions, and well-chosen mixtures often perform significantly better than single components23. The precise properties of surfactant mixtures are strongly influenced by the chemical structures of the surfactants, their mixing ratios and the total amount of surfactant used. Thus, the number of experiments required to fully explore the performance of mixtures is often too large to perform manually, necessitating automated measurements.

We explored two binary mixtures. One system consisted of sodium octyl sulphate (SOS) and sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS, Fig. 5), and the other of benzyldimethylhexadecyl ammonium chloride (16-BAC) and dodecyltetraethylene glycol ether (C12E4, Fig. S6). Stock solutions of mixtures of each binary surfactant mixture were supplied to the robotic module, and characterisation was performed following the same protocol used for single-surfactant systems, resulting in surface tension isotherms at different molar ratios (Fig. 5a and Fig. S6a). Here, the Szyszkowski equation (Eq. 1) was used as a guide to collect data on ‘slices’ of constant surfactant ratio in the two-dimensional concentration landscape. Though the parameters that the algorithm estimated are not valid (as the model is only valid for single compound solutions), they still produce predictions with a response that we would expect of a constant-ratio slice through the two-dimensional concentration landscape.

a Surface tension isotherms of the binary mixture SOS/SDS at different molar fractions of SOS, with exploration points shown as circles and exploitation points as crosses. Surface tension isotherms were measured at 23 °C. b Critical micelle concentration (CMC) and c adsorption efficiency (C20) as a function of the molar fraction of SOS (α). The dashed line represents the ideal behaviour, the solid line is a fit using Rubingh’s model23 to determine the interaction parameter (β) between both surfactants, either for micellization (βM = −2.3) or adsorption (βσ = −1.1).

To account for the effect of the micellar interaction between the two surfactants upon the monomeric surfactant concentration, we used the Rubingh mixed micelle model23. This model accounts for the interactions between different surfactant types in micelles via an interaction parameter (βM, Eq. 5). Negative values for β reflect attractive interactions (synergism), while the positive β reflects repulsive interaction (antagonism). The magnitude of β reflects the strength of the interaction, where a β of zero reflects an ideal mixing process (purely entropy driven).

Here, \(\alpha\) is the molar fraction of surfactant 1 in the total bulk surfactant mixture, \({{CMC}}_{{mix}}\) is the CMC of the binary mixture, \({{CMC}}_{1}\) is the CMC of surfactant 1 and \({x}_{1}\) denotes the mole fraction of surfactant 1 in the micelle (see Methods on how this parameter is estimated). Using Eq. 5, we determined the micellar interaction parameter (βM) by performing a least-squares fit of the experimentally measured \({{CMC}}_{{mix}}\) values obtained from the surface tension isotherms, as a function of \(\alpha\) (Fig. 5b and Fig. S6b).

Furthermore, to evaluate the interaction between the two surfactants with respect to adsorption, the Rubingh mixed micelle model can be adapted by replacing \({{CMC}}_{{mix}}\), which reflects micellization, with the concentration at which the surface tension of water is reduced by 20 mN/m (C20), which reflects surfactant surface adsorption efficiency35. The adsorption interaction parameter (βσ) is determined according to the same procedure as for the micellar interaction parameter (Fig. 5c and Fig. S6c).

The determined interaction parameters for both micellisation and adsorption for both characterised binary mixtures are reported in Table 2. The total characterisation times for the SOS/SDS mixture and BAC/C12E4 mixture were 9 h and 12 h, respectively. This difference in characterisation time was due to the longer pendant drop measurement time for the C12E4 surfactant. The SOS/SDS mixture exhibited clear deviations from ideality in both micellization and adsorption, whereas the 16-BAC/C12E4 mixture showed non-ideal behaviour in the adsorption process. The determined interaction parameters are in line with those reported for similar binary surfactant systems. For anionic–anionic surfactant pairs, such as the SOS/SDS mixture, βM values typically range from 2 to –4, while βσ values range from 2 to –2.536,37. In the case of cationic-nonionic pairs, like the 16-BAC/C12E4 mixture, βM spans –4.5 to 0.5 and βσ spans –3 to –136,37,38. For example, a solution of SDS and sodium decyl sulphate (SDeS), which is analogous to the SOS/SDS mixture reported here, has a reported micellar interaction parameter of βM = −1.0539.

These findings demonstrate that our approach is capable of efficiently collecting data on surfactant mixtures, even if they deviate from ideal surfactant behaviour. Additionally, we note that the Szyszkowski equation (Eq. 1) can practically be used to guide the experimental space for mixtures, even though it is theoretically valid only for single-surfactant systems.

In this work, we developed an autonomous module to efficiently characterise the surface tension properties of a wide range of surfactants and surfactant mixtures using pendant drop tensiometry. The module is designed to tackle the various in operando experimental challenges, taking action to optimise for the precision and accuracy of surface tension data, as well as choosing experimental data points which optimise for the estimation of key parameters which characterise the surface activity of compounds.

To ensure precise and accurate surface tension measurement, the module automatically determines the optimal droplet volume for each sample, balancing gravitational forces and surface tension. Using this procedure, standard deviations of 0.07 mN/m and 0.22 mN/m were achieved for measurements of the surface tensions of water and SDS samples, respectively.

Furthermore, to efficiently characterise surfactants, we implemented an active learning approach that combines Bayesian inference with mutual information calculations to guide the selection of further concentrations for measurement. This algorithm enables the autonomous selection of the most informative formulations based on the Szyszkowski equation, resulting in rapid and accurate characterisation.

We demonstrated the ability of the self-driving module by characterising 11 diverse surfactants. Our measurements show good agreement with literature values for CMC, γCMC and Γmax while also providing new property data for surfactants not yet included in the database. Furthermore, we show the capability of the module to characterise surfactant mixtures by mapping the surface tension of two binary surfactants mixtures.

Given the vast chemical space of mixtures and the even larger space of their associated physical properties, autonomous modules are essential to explore and understand this complex design space. Building on the current active learning framework, future work will focus on extending the use of physical models to explore and characterise multi-component surfactant mixtures. We envision that this self-driving platform will open new avenues for navigating and accelerating discovery in the dynamic field of formulations.

Methods

Materials

Surfactants were used as received without further purification. Supplier information and purities are detailed in Table 3. Stock solutions were prepared gravimetrically using ultrapure water (resistivity: 18.2 MΩ·cm) in 15 mL or 50 mL polypropylene (PP) Falcon tubes (Greiner Bio-One). Automated formulations were performed using a robotic platform with P1000 and P20 tips (Sarstedt), dispensing into 96-well PP plates with chimney wells and clear, transparent bottoms (Greiner Bio-One). Droplet measurements were conducted in an enclosure constructed from a standard 1 cm polystyrene cuvette (Greiner Bio-One), filled with 1 mL of ultrapure water to minimise evaporation of the pendant droplet. A blunt-ended stainless steel needle (gauge 23, SAI Industries) was used to dispense the pendant droplets.

Instrumentation and setup

An Opentrons OT-2 liquid-handling robot equipped with P1000 and P20 Gen2 pipettes was used for automated sample preparation and pendant drop measurements. For imaging, a Basler Ace U acA2500-60um camera, zoom 6000 Navitar Lens System and a white led with a glass diffuser plate was used. Pipette tips racks and falcon tube racks were 3D printed and the corresponding designs can be found via GitHub (https://github.com/BigChemistry-RobotLab/PendantProp). Pictures of the robotic setup are given in the Supplementary information (Fig. S1).

Free monomeric surfactant model

The free monomeric surfactant concentration (\({S}_{1}\) in Eq. 1) was estimated using an empirical model developed by Al-Soufi et al. (Eq. 6)28.

Here, \({s}_{0}\) is the total surfactant concentration, \({CMC}\) is the CMC, \(r\) is the relative transition width, quantifying the sharpness of the transition between the pre-CMC and post-CMC regimes, and ‘\(\text{erf}\)’ denotes a sigmoidal error function. We chose a constant relative transition width (\(r\) = 0.01), to model a sharp transition in the surface tension isotherm around CMC.

Image analysis pipeline

Raw pendant drop images (Fig. S2a) were processed using a Gaussian blur kernel (kernel dimensions 9 × 9, Fig. S2b). Subsequently, the edges were extracted by a Canny edge detection algorithm with a threshold of 10 pixels (Fig. S2c). The edges were dilated and eroded (Fig. S2d and Fig. S2e). Contours were extracted and the largest contour was assumed to be the droplet profile. From this contour two geometric parameters were extracted (Fig. S2f). The maximum horizontal diameter (de) was determined by calculating the largest horizontal diameter in the extracted contour. The position of bottom edge of the droplet contour was extracted (ylower), and the horizontal diameter (ds) was measured as the distance between the vertical contours of the droplet at a height of ylower + de. The geometric parameters were converted from pixels to millimetres (mm) using a measurement of the needle diameter. The needle diameter in pixels was determined as the width of the contour at the top of the frame in pixels, divided by the manufacturer specified diameter of the needle.

Worthington number threshold

Optimal droplet volumes were determined by evaluating the Worthington number while dispensing in 0.1 μL intervals (Fig. S3). Dispensing was stopped if the Worthington number threshold of 0.6 was reached. If the solution contained surfactant, the initial droplet wetted the dispensing needle. These cases were identified by an algorithm that checked whether the measured needle diameter fell within a predefined range relative to the expected diameter of needle measured in the absence of a solution. If wetting occurred, the Worthington number was set to zero, prompting additional dispensing.

As the droplet volume was increased, gravitational forces eventually overcame wetting forces, allowing a pendant droplet to form. At this stage, surface tension was computed and the Worthington number was evaluated. If the Worthington number remained below the 0.6 threshold, more solution was dispensed until the threshold was reached. Once a stable pendant droplet yielded a Worthington number greater than 0.6, dispensing was stopped and the corresponding surface tension value was recorded over time.

Du Noüy ring tensiometry

The Du Noüy ring tensiometry experiments were performed using a Biolin Scientific force tensiometer (Sigma 700/701) equipped with a platinum Du Noüy ring probe (Biolin Scientific, ISO 301). The probe was cleaned with isopropanol and subsequently heated until red-hot using a torch. Samples were prepared by serial dilution in 15 mL Falcon tubes and transferred to a measurement vessel (the base of a petri dish with a diameter of 35 mm). Each sample was measured for 5 min, and the average surface tension over the final 1 min was taken as the equilibrium value.

Determination of surfactant properties from surface tension isotherms

Property values for CMC, \({{\rm{\gamma }}}_{{CMC}}\) and \({\Gamma }_{\max }\) were estimated by fitting Eq. 1 to each data set of surface tension vs. surfactant concentration. For fitting, a Hamiltonian Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm, using the the No-U-Turn Sampler40, was used to infer the posterior distributions of the fitting parameters (CMC, Γmax and KL) and dependent variable (surface tension). The CMC value was determined by calculating the mean of the posterior distribution of the CMC. The \({{\rm{\gamma }}}_{{CMC}}\) was obtained by evaluating the mean of the posterior distribution of the surface tension at the inferred CMC value. For the determination of \({\Gamma }_{\max }\), the Gibbs adsorption equation (Eq. 7) was used.

Here, \(n\) is one, plus the number of counter ions brought to the interface (n = 1 for non-ionic surfactants and generally n = 2 for charged surfactant), \(R\) the ideal gas constant, \(T\) the temperature and \({\left(\frac{\partial \gamma }{\partial \mathrm{ln}{C}}\right)}_{\max }\) corresponds to the maximum slope of the surface tension (\(\gamma\)) as a function of the natural logarithm of the total surfactant concentration (\(C\)). The \({\left(\frac{\partial \gamma }{\partial \mathrm{ln}{C}}\right)}_{\max }\) was estimated by calculating the slope over small intervals, \(\left(\frac{\partial \,\gamma }{\partial \,\mathrm{ln}{C}}\right)\), across the surface tension isotherm, using the mean of the posterior distributions of the surface tensions and the corresponding natural logarithms of the concentrations, and subsequently identifying the maximum value. Given the temperature and the charge of the surfactant, \({\Gamma }_{\max }\) was estimated, using Eq. 7.

Micellar and adsorption interaction in binary surfactant mixtures

Interaction parameters in binary mixtures were estimated using Eq. 5. The mole fraction of surfactant 1 in the mixed micelle (\({x}_{1})\) is estimated by solving Equation 8 iteratively for \({x}_{1}\).

Here, \(\alpha\) is the molar fraction of surfactant 1 in the total bulk surfactant mixture, \({{CMC}}_{{mix}}\) is the CMC of the binary mixture, \({{CMC}}_{1}\) is the CMC of surfactant 1 and \({{CMC}}_{2}\) is the CMC of surfactant 2. Given the experimentally \({{CMC}}_{{mix}}\) value at different molar fraction \(\alpha\), equation 8 was solved for \({x}_{1}\) numerically with the Nelder-Mead method41.

The ideal behaviour line represented in Fig. 5a and Fig. S6a, was calculated by Clint’s equation15 (Eq. 9).

SurfPro predictions

The SurfPro data and model code were pulled from GitHub9 on 30/6/2025. For literature values of \({CMC}\), \({\gamma }_{{CMC}}\) or \({\Gamma }_{\max }\) which were not available in the database, as well as for surfactant structures not present in SurfPro, estimates were obtained using SurfPro \({{AttentiveFP}}_{{all}}^{64d}\) GNN ensemble model9. The model was trained using the supplied pipeline to produce 10 models trained for the ‘all’-property training task on 10 folds of the training data, with a hidden dimension of 64. Other hyperparameters were reproduced as specified in the SurfPro publication. A Python script (predict.py available via Zenodo33) was created to obtain predictions for structures not found in the SurfPro database, as well as for imputation of missing values. The ensemble model was then used to provide estimates, as the mean ensemble prediction, for the missing surfactant structures and values using the surfactant SMILES representations as input (Table S1).

Data availability

All data required to reproduce the figures and results in this manuscript are available in a Zenodo repository available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1723276333.

Code availability

The version of the code used to run the robotic platform and to produce the results in this manuscript has been archived in a Zenodo repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17232763). The most recent version, along with ongoing updates, can be found at the GitHub repository (https://github.com/BigChemistry-RobotLab/PendantProp). The SurfPro models9 are available via GitHub (https://github.com/BigChemistry-RobotLab/SurfPro).

References

Summers, M. & Eastoe, J. Applications of polymerizable surfactants. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 100–102, 137–152 (2003).

De, S., Malik, S., Ghosh, A., Saha, R. & Saha, B. A review on natural surfactants. RSC Adv. 5, 65757–65767 (2015).

Yu, Y., Zhao, J. & Bayly, A. E. Development of surfactants and builders in detergent formulations. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 16, 517–527 (2008).

Baret, J.-C. Surfactants in droplet-based microfluidics. Lab Chip 12, 422–433 (2012).

Ceresa, C., Fracchia, L., Fedeli, E., Porta, C. & Banat, I. M. Recent advances in biomedical, therapeutic and pharmaceutical applications of microbial surfactants. Pharmaceutics 13, 466 (2021).

Kralova, I. & Sjöblom, J. Surfactants used in food industry: a review. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 30, 1363–1383 (2009).

Seddon, D., Müller, E. A. & Cabral, J. T. Machine learning hybrid approach for the prediction of surface tension profiles of hydrocarbon surfactants in aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 625, 328–339 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Prediction of critical micelle concentration (CMC) of surfactants based on structural differentiation using machine learning. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 703, 135276 (2024).

Hödl, S. L. et al. SurfPro—a curated database and predictive model of experimental properties of surfactants. Digit. Discov. https://doi.org/10.1039/D4DD00393D (2025).

Scholz, N., Behnke, T. & Resch-Genger, U. Determination of the critical micelle concentration of neutral and ionic surfactants with fluorometry, conductometry, and surface tension—a method comparison. J. Fluoresc. 28, 465–476 (2018).

du Noüy, P. L. An interfacial tensiometer for universal use. J. Gen. Physiol. 7, 625–631 (1925).

Volpe, C. D. & Siboni, S. The Wilhelmy method: a critical and practical review. Surf. Innov. 6, 120–132 (2018).

Cottingham, M. G., Bain, C. D. & Vaux, D. J. Rapid method for measurement of surface tension in multiwell plates. Lab. Investig. 84, 523–529 (2004).

Berry, J. D., Neeson, M. J., Dagastine, R. R., Chan, D. Y. C. & Tabor, R. F. Measurement of surface and interfacial tension using pendant drop tensiometry. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 454, 226–237 (2015).

Pandi, A. et al. A versatile active learning workflow for optimization of genetic and metabolic networks. Nat. Commun. 13, 3876 (2022).

Seifrid, M. et al. Autonomous Chemical experiments: challenges and perspectives on establishing a self-driving lab. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2454–2466 (2022).

Shiri, P. et al. Automated solubility screening platform using computer vision. iScience 24, 102176 (2021).

Soh, W. et al. Automated pipetting robot for proxy high-throughput viscometry of Newtonian fluids. Digit. Discov. 2, 481–488 (2023).

Liang, Q. et al. Benchmarking the performance of Bayesian optimization across multiple experimental materials science domains. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 188 (2021).

Lei, B. et al. Bayesian optimization with adaptive surrogate models for automated experimental design. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 194 (2021).

Rosen, M. J. Adsorption of surface-active agents at interfaces, adsorption isotherms. in Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

Szyszkowski, Bvon Experimentelle Studien über kapillare Eigenschaften der wässerigen Lösungen von Fettsäuren. Z. Phys. Chem. 64U, 385–414 (1908).

Rubingh, D. N. Mixed micelle solutions. in Solution Chemistry of Surfactants Vol. 1 (ed. Mittal, K. L.) 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-7880-2_15 (Springer New York, 1979).

Wu, Y., Walsh, A. & Ganose, A. M. Race to the bottom: Bayesian optimisation for chemical problems. Digit. Discov. 3, 1086–1100 (2024).

Slattery, A. et al. Automated self-optimization, intensification, and scale-up of photocatalysis in flow. Science 383, eadj1817 (2024).

Pomberger, A. et al. Automated pH adjustment driven by robotic workflows and active machine learning. Chem. Eng. J. 451, 139099 (2023).

Shields, B. J. et al. Bayesian reaction optimization as a tool for chemical synthesis. Nature 590, 89–96 (2021).

Al-Soufi, W., Piñeiro, L. & Novo, M. A model for monomer and micellar concentrations in surfactant solutions: application to conductivity, NMR, diffusion, and surface tension data. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 370, 102–110 (2012).

Gittens, G. J. Variation of surface tension of water with temperature. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 30, 406–412 (1969).

Misak, M. D. Equations for determining 1/H versus S values in computer calculations of interfacial tension by the pendent drop method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 27, 141–142 (1968).

Kalová, J. & Mareš, R. Temperature dependence of the surface tension of water, including the supercooled region. Int. J. Thermophys. 43, 154 (2022).

Hernáinz-Bermúdez de Castro, F., Gálvez-Borrego, A. & Calero-de Hoces, M. Surface tension of aqueous solutions of sodium dodecyl sulfate from 20 °C to 50 °C and pH between 4 and 12. J. Chem. Eng. Data 43, 717–718 (1998).

Dankloff, P. F. J. et al. An autonomous robotic module for efficient surface tension measurements of formulations. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17232763 (2025).

El-Hefian, E. A., & Yahaya, A. H. Investigation on some properties of SDS solutions. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 5, 1221–1227 (2011).

Hua, X. Y. & Rosen, M. J. Calculation of the coefficient in the Gibbs equation for the adsorption of ionic surfactants from aqueous binary mixtures with nonionic surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 87, 469–477 (1982).

Rosen, M. J. Molecular interactions and synergism in mixtures of two surfactants. in Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

Suzuki, N. Interaction parameters for the formation of mixed micelles and partitioning of solutes in them: a review. AppliedChem 4, 1–14 (2024).

Serafini, P. et al. The aqueous Triton X-100—dodecyltrimethylammonium bromidemicellar mixed system. Experimental results and thermodynamic analysis. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 559, 127–135 (2018).

Maneedaeng, A., Haller, K. J., Grady, B. P. & Flood, A. E. Thermodynamic parameters and counterion binding to the micelle in binary anionic surfactant systems. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 356, 598–604 (2011).

Hoffman, M. D. & Gelman, A. The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1593–1623 (2014).

Nelder, J. A. & Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J. 7, 308–313 (1965).

Ricardo, F. et al. Estimation and prediction of the air–water interfacial tension in conventional and peptide surface-active agents by random Forest regression. Chem. Eng. Sci. 265, 118208 (2023).

Rosen, M. J., Cohen, A. W., Dahanayake, M. & Hua, X. Y. Relationship of structure to properties in surfactants. 10. Surface and thermodynamic properties of 2-dodecyloxypoly(ethenoxyethanol)s, C12H25(OC2H4)xOH, in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. 86, 541–545 (1982).

Liu, X.-G., Xing, X.-J. & Gao, Z.-N. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of star-like cationic trimeric surfactants. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 457, 374–381 (2014).

Yatcilla, M. T. et al. Phase behavior of aqueous mixtures of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) and sodium octyl sulfate (SOS). J. Phys. Chem. 100, 5874–5879 (1996).

Shah, S. K., Chatterjee, S. K. & Bhattarai, A. The effect of methanol on the micellar properties of dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) in aqueous medium at different temperatures. J. Surfactants Deterg. 19, 201–207 (2016).

Lin, I. J. & Marszall, L. C. M. C. HLB, and effective chain length of surface-active anionic and cationic substances containing oxyethylene groups. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 57, 85–93 (1976).

Woolfrey, S. G., Banzon, G. M. & Groves, M. J. The effect of sodium chloride on the dynamic surface tension of sodium dodecyl sulfate solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 112, 583–587 (1986).

Kaneshina, S., Tanaka, M., Tomida, T. & Matuura, R. Micelle formation of sodium alkylsulfate under high pressures. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 48, 450–460 (1974).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the National Growth Fund project “Big Chemistry” (1420578), funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. This project was also supported by the European Union and the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract numbers 22.00017 and 22.00034 (Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Project CORENET).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.F.J.D., W.T.S.H., P.A.K. and W.E.R. conceived the research. P.F.J.D., M.v.R. and W.E.R. developed the robotic module. M.G.B. developed the active learning algorithm, and P.F.J.D. implemented the active learning algorithm in the module. E.v.d.V. performed initial research on active learning with surfactants. P.F.J.D., M.v.R. and D.H.W.K. performed the experiments and P.F.J.D. performed the analysis. S.L.H. performed the SurfPro predictions. P.A.K., W.T.S.H. and W.E.R. supervised the project. The first draft was written by P.F.J.D. and edited by P.A.K., W.T.S.H. and W.E.R.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no Non-Financial Competing Interests, but the following Financial Competing Interests: a patent application covering aspects of the automated platform presented in this work has been filed by the Big Chemistry consortium, with the following inventors: P.F.J.D., M.v.R., M.G.B., W.T.S.H. and W.E.R.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dankloff, P.F.J., van Rossum, M., Baltussen, M.G. et al. An autonomous robotic module for efficient surface tension measurements of formulations. npj Comput Mater 11, 358 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01842-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01842-9