Abstract

ABN3-type nitride perovskites offer a rich platform for multifunctional materials but remain synthetically elusive. Here, we develop a machine learning (ML)-guided framework to expand the library of nitride perovskites and identify multiferroic candidates. By integrating positive-unlabeled (PU) learning with crystal graph convolutional neural networks (CGCNN), we screen 1465 ABN3 compositions and predict 96 synthesizable compounds. Further symmetry and magnetic filtering yield 4 altermagnetic ferroelectric (AM-FE) perovskites. Among them, CeCrN3 emerges as a promising candidate, exhibiting a bandgap of 0.30 eV, a spontaneous polarization of 0.59 μC/cm2, a high Curie temperature of 650 K, and a low polarization switching barrier of 53 meV, as confirmed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. In addition, CeCrN3 demonstrates a pronounced bulk photovoltaic effect (BPVE), with the shift current reaching 44 μA/V2 and an injection current reaching 2.4 × 109 A/V2, both of which reverse upon FE switching. These findings not only advance the understanding of nitride perovskites but also provides a validated ML-DFT framework to guide experimental efforts in realizing novel functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitride perovskites (ABN3) represent an emerging frontier for multifunctional materials1,2,3,4,5. Their mixed covalent-ionic bonding and tunable bandgaps endow them with potential for diverse phenomena6,7,8,9, including magnetism, ferroelectricity, and strong nonlinear optical responses with potential impacts in spintronics and energy conversion10,11,12,13. However, experimental progress has been limited by the intrinsic inertness of nitrogen, which makes synthesis extremely challenging. To date, only a few ABN3 compounds have been realized, leaving their vast functional potential largely unexplored2,14,15.

Traditional high-throughput screening typically filters candidates by thermodynamic descriptors16,17,18,19,20,21, such as energy above hull (Ehull) or formation energy22,23,24,25. However, this approach fails to capture the broader synthesizability window of nitrides, many of which exist in metastable but accessible phases26. This challenge calls for predictive strategies beyond stability-based filters. Here, we develop a machine-learning framework that integrates crystal graph convolutional neural networks (CGCNN) with positive-unlabeled (PU) learning27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Unlike conventional supervised models, PU learning directly addresses the lack of reliable negative synthesis data, enabling a more realistic evaluation of synthesizability across a wide chemical space.

Applying this framework to 1465 ABN3 compositions, we predict 96 synthesizable nitrides and uncover a previously overlooked class of functional materials: altermagnetic ferroelectrics (AM-FEs). This newly identified magnetic phase is distinct from both ferromagnetism and antiferromagnetism36,37,38,39,40,41, featuring zero net magnetization alongside a unique momentum-dependent spin splitting that opens exciting possibilities for spintronic and memory devices42,43,44,45. From our screening, we identify 4 AM-FE candidates, with CeCrN3 standing out for robust polarization, high Curie temperature, and strong bulk photovoltaic effect. These findings not only expand the landscape of nitride perovskite but also provide a route guided by PU-learning to discover synthesizable materials with targeted quantum functionalities.

Results

Workflow for PU learning

In the ABN3 structure with the Pna21 (No. 33) space group, the nitrogen atoms are situated at the vertices of the octahedral networks. The B-site cations occupy the centers of the octahedra, while the A-site cations reside within the interstitial cavities formed by the octahedral framework. For dataset construction, we substitute chemically equivalent elements at the A and B sites to generate a diverse set of ABN3 perovskite structures. To ensure charge neutrality, we employ the SMACT package to screen for stoichiometrically balanced compositions46,47. In addition, we apply a geometric constraint requiring the ionic radius of the B-site cation to be less than or equal to that of the A-site cation, a strategy intended to enhance structural stability and increase the likelihood of successful synthesis. Following these criteria, we generate 1465 ABN3 structures, which are treated as unlabeled samples (denoted as set U). From this pool, we randomly select samples to construct a set of pseudo-negative examples (denoted as N). By repeating the random sampling n times, we construct n distinct negative datasets, each of which serves as the training set for a separate ML model. A schematic overview of the PU learning workflow is presented in Fig. 1a.

The positive samples P are selected from the ICSD database, which represents crystalline structures that are amenable to experimental synthesis. Here, we select a set of 300 synthetic oxide perovskites and 1000 nitride materials from the ICSD dataset. The oxides, belonging to the space group Pna21, are specifically chosen to complement the relatively fewer nitrides with the same space group arrangement. This selection strategy aims to enhance the model’s capacity to generalize across different types of perovskite structures. By using the positive samples P and the negative samples N as the training set, n binary classifiers are fitted. These classifiers are then used to predict the class affiliation of the samples within U, thereby estimating the probability of each sample belongs to either P or N. In this work, we adopt CGCNN as our classifier of choice.

The CGCNN model begins by encoding the crystal structure using a one-hot encoding approach (refer to Table S1 and Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information for details). Once encoded, the crystal graph is transformed into a vector matrix, which serves as an attribute of the crystal and acts as the input for the neural network. In Fig. 1b, we illustrate the schematic diagram of CGCNN. Within this network, the representation undergoes a series of convolutional layers (L1), refining the atomic vectors to capture local environmental influences. The refined atomic vectors are then processed through additional convolutional layers (L2) followed by a pooling layer, ultimately generating a comprehensive feature vector that encapsulates the structural characteristics of the crystal. This feature vector guides the model in producing an accurate predictive probability, denoted as P. To assess the classifier’s performance, the area under the curve (AUC) is employed as a quantitative evaluation metric. In our PU learning, the boxplot of the AUC for CGCNN classifiers is shown in Fig. S2. Notably, the average AUC is 0.86, demonstrating strong predictive capability.

Finally, the probability scores garnered for each sample across the n subsets are averaged and normalized, yielding the sample’s Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore). Specifically, a CLscore close to 1 indicates a high likelihood of the sample being positively labeled (i.e., synthesizable), whereas a score approaching 0 suggests the contrary. In PU learning, the CL score is an important metric that will be used to categorize the samples. Therefore, selecting an appropriate CLscore threshold is a critical factor. Figure 2a shows the distribution of materials across different CLscores. To determine a robust threshold, we evaluate the model’s performance on a validation set. A CLscore of 0.7 is selected as it optimally balances the rate of successful synthesis predictions (based on the training data) with the stability confirmed by phonon spectrum calculations (see Supplementary information for more details), thereby minimizing false positives while maintaining a high recall.

a Proportion of ABN3 materials with different CLscore. b The number of A atoms (in red) and B atoms (in black) among ABN3 compounds with CLscore > 0.7. c Schematic illustration of screening workflow for identifying AM-FE ABN3 candidates. d Predicted synthesizable ABN3 perovskite compositions mapped by A-site (vertical axis) and B-site (horizontal axis) elements. Black boxes denote AM-FE ABN3 candidates.

Based on this threshold, we identify 96 potential ABN3 candidates. Their predicted synthesizability is visualized as a periodic table map shown in Fig. 2b. Among these synthesizable compounds, the A-site elements mainly include Group IA alkali metals and lanthanide-series elements. These elements readily adopt ionic forms compatible with the cationic sublattice, benefiting from their suitable size and charge characteristics. In contrast, the B-site is typically occupied by main-group elements from Groups IIIA to IVA (such as Al, Ge), which contribute to covalent bonding or framework formation, as well as transition metals (e.g., Cr, Cu, and W), whose variable oxidation states and coordination environments enhance the structural and chemical versatility of the compounds. Figure 2d presents the distribution of CLscores for all ABN3 materials, which can serve as a guiding reference for experimental synthesis. The CLscores are widely scattered, with no clear clustering around specific elements, implying that synthesizability is determined by complex multi-element interactions rather than any single elemental property.

Catalogue of AM-FE ABN3

As shown in Fig. 2c, we further search for synthesizable AM-FE ABN3 compounds based on the 96 candidates identified above. The screening process is constrained to non-centrosymmetric space group, i.e., Pna21 (the focus of this study), which breaks the inversion symmetry and can enable ferroelectricity. In particular, we focus on compounds containing magnetic atoms such as Fe, Co, Ni, Mn, V, and Cr, whose partially filled d-orbitals can facilitate magnetic exchange interactions essential for realizing multiferroicity. To identify configurations that host an AM phase, we perform spin-polarized DFT calculations (Fig. 2c), which are implemented in the VASP48,49. Following this screening procedure, we identify 4 AM-FE ABN3 compounds, as highlighted in the boxed region of Fig. 2d and tabulated in Table S3, corresponding to 3.6% of the synthesizable set.

Representative material: CeCrN3

Multiferroic properties

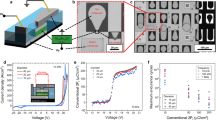

Following the model predictions, we further investigate the magnetic, FE, and nonlinear optical properties of selected candidates to identify multifunctional materials. Here, CeCrN3 is presented as a representative case study. As shown in Fig. 3a, CeCrN3 crystallizes in an orthorhombic perovskite structure with lattice parameters of a = 5.54, b = 5.37, and c = 7.66 Å. In this structure, Cr atoms occupy off-center positions within the octahedral coordination, breaking inversion symmetry and giving rise to ferroelectricity. Meanwhile, an AM ground state is identified, in which the magnetic moments of neighboring Cr atoms with 1.6 μB are antiparallel. The projected density of states (PDOS) analysis of CeCrN3, as depicted in Fig. 3b, reveals that the conduction band minimum (CBM) primarily originates from hybridization between the Ce, Cr and N atoms, while the valence band maximum (VBM) is mainly attributed to the N atoms. To further characterize its electronic properties, we perform band structure calculations using hybrid functionals (HSE06), which confirm a semiconducting behavior with a bandgap of 0.30 eV. As presented in Fig. 3c, d, the VBM is located along the Γ-X path, while the CBM is located at the X point.

a Crystal structure of CeCrN3 in the FE phase. Electronic properties obtained from HSE06 calculations, including b the projected density of states (PDOS), c band structures along high-symmetry k-paths, d band structures along general k-paths, and the corresponding spin-splitting distributions (E↑ − E↓ ) for e the valence band and f the conduction band. g Energy profile of the polarization switching pathway calculated via the CI-NEB method. h Simulated polarization-electric field (P-E) hysteresis loop. i Calculated temperature dependence of spontaneous polarization.

Clearly, along high-symmetry k-paths, the spin-up and spin-down bands remain degenerate due to crystal symmetry. However, along general k-paths, spin splitting is observed. In Fig. 3e, f, we illustrate the spin splitting distribution (E↑–E↓ ) of the valence band and conduction band, with magnitudes reaching 180 meV and 370 meV, respectively. This splitting originates from local non-centrosymmetry induced by non-magnetic atoms, which induces distortions in the magnetization density around the Cr sublattices, leading to the breaking of \({\mathcal{P}}{\mathcal{T}}\) symmetry. Importantly, although the sign of spin splitting alternates across the Brillouin zone, the magnitude respects the overall crystal symmetry, ensuring spin compensation. As a result, CeCrN3 in its AM phase exhibits zero net magnetization, as clearly demonstrated by its DOS shown in Fig. 3b.

In the FE phase of CeCrN3, the displacement of Cr atoms can drive the system into a non-polar paraelectric (PE) phase, or into an opposite polarization phase (FE’). To investigate this phase transition, we employ the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method. The energy profile along the transition path is shown in Fig. 3g, starting from the initial FE state, intermediate PE configuration, and reaching the final FE’ state. The calculated energy barrier is only 53 meV/f.u., indicating that the transition between these states can be easily triggered by an external electric field. We further evaluated the spontaneous polarization (PS) of CeCrN3 using the modern Berry phase approach. As shown in Fig. 3g, the PS value, defined as the polarization difference between the FE and PE phases, is computed to be 0.59 μC/cm². This result underscores the potential of CeCrN3 for FE applications, where low switching barriers and finite polarization are both critical for device performance.

In addition, we simulate the polarization hysteresis loop for CeCrN3 based on the perturbation approach, as illustrated in Fig. 3h. The critical electric field for the phase transition is 2.0 MV/cm, beyond which the FE′ phase becomes unstable and reverts to the FE ground state. Notably, this switching field is comparable to that of conventional oxide perovskites50,51, suggesting that CeCrN3 exhibits a similarly accessible switching behavior under practical electric fields. To further characterize the FE behavior, we evaluate the Curie temperature (TC) of CeCrN3. As shown in Fig. 3i, the polarization gradually diminishes with increasing temperature, and the fitted TC is approximately 650 K, highlighting the robustness of ferroelectricity at elevated temperatures.

BPVE

Beyond its AM-FE properties, CeCrN3 exhibits a strong nonlinear optical response through the BPVE, enabling the generation of photocurrent in the absence of p-n junctions. To assess the nonlinear photoresponse, we investigate the BPVE in CeCrN₃ under different light polarizations. The photocurrent can be decomposed into two distinct components: the shift current (\({J}_{{SC}}^{a}\)) induced by linearly polarized light and the injection current (\({J}_{{IC}}^{a}\)) generated by circularly polarized light. Given the tensorial nature of the shift current conductivity \({\sigma }_{{bc}}^{a}\) and injection current response \({\eta }_{{bc}}^{a}\), we present only the largest component, i.e., \({\sigma }_{{zz}}^{z}\) and \({\eta }_{{yz}}^{y}\), as shown in Fig. 4a, d. The shift current reaches a peak value of 44 μA/V², which is much larger than that of traditional ferroelectric materials, such as BiFeO3 (0.05 μA/V2) and BiTiO3 (5 μA/V2)52,53. And the injection current peaks at 2.4 \(\times\)109 A/V², surpassing the values reported for wurtzite semiconductors (CdSe: 1.5 \(\times\)108 A/V² and CdS: 4 \(\times\)108 A/V²)54. To explore the effect of FE polarization on the photocurrent response, we also calculate the shift and injection currents for the reversed-polarization FE′ phase of CeCrN3. As shown in Fig. 4a, d, reversing the polarization direction leads to a clear reversal in the sign of both the shift and injection currents. This indicates that the photocurrent direction can be effectively controlled by switching the FE order, which offers a microscopic mechanism for electric-field-tunable photodetection and energy conversion.

To further investigate the microscopic origin of the BPVE, we analyze the momentum-resolved distribution of the shift current SC(k) and injection current IC(k) across the Brillouin zone, as shown in Fig. 4b–f. Here, we focus on the first peaks, occurring at 0.52 eV for the shift current and 0.46 eV for the injection current. In both the FE and FE′ phases, the overall magnitudes of the responses are identical, but the shift vector changes sign with polarization switching, consistent with the observed photocurrent reversal. Figure 4b, c reveal that the dominant contributions to the shift current arise from inter-band transitions near general k-points rather than high-symmetry paths. Similarly, Fig. 4e, f indicate that the injection current arises primarily from transitions at general k-points as well. Notably, both currents are fundamentally governed by the band structure and underlying quantum geometry. Their magnitude and direction depend sensitively on the Berry connection and the geometric phase of electrons. This quantum‑geometric mechanism accounts for the polarization‑dependent current reversal and underlies the pronounced BPVE in CeCrN3, establishing it as a promising platform for nonlinear optical applications.

Discussion

The integration of PU-learning with CGCNN provides an efficient and generalizable route for identifying synthesizable inorganic compounds from large and incomplete datasets. In contrast to conventional stability-based screening that relies mainly on formation energy, the PU-learning framework implicitly incorporates synthesis information by learning from both positive and unlabeled samples. When applied to the nitride perovskites, this approach yields a set of 96 candidates with high CLscore. The subsequent phonon calculations confirm that compounds with CLscore above 0.7 exhibit no imaginary frequencies, demonstrating a strong correlation between the model predictions and dynamical stability. This consistency indicates that the data-driven CLscore can serve as a reliable proxy for evaluating synthesizability, effectively bridging the gap between statistical learning and first-principles validation.

From the set of synthesizable candidates, four multiferroic compounds exhibiting coupled ferroelectric and altermagnetic orders were identified, among which CeCrN3 was selected for detailed investigation. The DFT results reveal that CeCrN3 combines a moderate bandgap, robust polarization, and structural stability, highlighting its potential as a prototype multiferroic nitride. These findings suggest that the PU-learning-driven CGCNN framework offers a practical and transferable strategy for accelerating the discovery of synthesizable functional materials. By efficiently linking data-driven screening with physical verification, this workflow can be extended to other material families, providing a foundation for the rational exploration of experimentally realizable compounds with targeted functionalities.

Methods

DFT calculation

All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP)48,55. We employed the projected augmented wave method to accurately describe the electron-ion interactions56, in conjunction with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional for the exchange-correlation energy, providing a robust framework for our simulations57. A moderate plane-wave cutoff energy of 400 eV was chosen to balance computational efficiency and accuracy. For the Brillouin zone integration during structural optimization, a dense 4 × 4 × 3 k-point mesh was utilized to ensure precise results58. The calculations were considered converged when the energy and force thresholds reached stringent limits of 10−5 eV per atom and 0.01 eV/Å, respectively. The GGA-PBE tends to underestimate band gaps and related electronic properties. In response, the state-of-the-art hybrid functional (HSE06) is employed in this work, in which the hybrid functional is mixed with 25% exact Hartree–Fock exchange59,60. To test for ABN3 dynamical stability, the phonons dispersion relations are calculated using phonopy software61,62, in which \(2\times 2\times 1\) supercells are used.

Electric enthalpy

To elucidate the underlying mechanism of field-induced ferroelectric phase transition, we adopt the electric enthalpy model, which accounts for the energy landscape under the application of a finite homogeneous electric field ε. Here, the phase stability is determined by the relative electric enthalpy, which is evaluated using the perturbation approach63,64,65.

where \(\left\{{\psi }^{\left(\varepsilon \right)}\right\}\) are field-polarized Bloch functions, \({E}_{B}\left[\left\{{\psi }^{\left(\varepsilon \right)}\right\}\right]\) is the energy barrier, \(P\left[\left\{{\psi }^{\left(\varepsilon \right)}\right\}\right]\) is the electric polarization, and Ω is the volume.

Curie temperature

We employ Monte Carlo (MC) simulations within the Landau-Ginzburg theoretical framework to determine the Curie temperature. The total energy associated with the electric polarization can be formulated as66,67:

where Pi is the electric polarization of the ith unit cell. A, B, C, and D are constant coefficients based on the DFT results for CeCrN3. The first three terms characterize the anharmonic double-well potential within the unit cells, while the last term represents the interaction between electric dipoles between different unit cells. Utilizing this effective model, we have conducted MC simulations to study the phase transition behavior. The temperature dependence of the electric polarization P(T) is typically described by the following relationship63,67:

where TC is the Curie temperature, δ is the critical exponent, and μ is a constant.

Shift current and Injection current

Under illumination with different polarizations of light, the photocurrent can be decomposed into two distinct components: the shift current (\({J}_{{sc}}^{a}\)) induced by linearly polarized light and injection current (\({J}_{{ic}}^{a}\)) induced by circularly polarized light. These two components can be determined using the following expressions68,69:

where a, b, and c denote cartesian directions. σabc is the shift current conductivity and \({\eta }_{{bc}}^{a}\) is the injection current conductivity, expressed as70:

where \(\hslash {\omega }_{{nm}}={E}_{n}-{E}_{m}\) represents the energy difference between different bands. \({f}_{{nm}}={f}_{n}-{f}_{m}\) is the difference of Fermi occupations. \({r}_{{mn}}^{a}=\frac{{v}_{{mn}}^{a}}{i{\omega }_{{mn}}}\,(m\ne n)\) is the interband Berry connection, \({v}_{{mn}}^{a}=\left\langle {m|}\frac{{dH}}{d{k}_{a}}{|n}\right\rangle\) is interband velocity matrix. The gauge covariant derivative for \({r}_{{mn}}^{b}\) is \({r}_{{mn;a}}^{b}=\frac{\partial {r}_{{nm}}^{b}}{\partial {k}_{a}}-i{r}_{{nm}}^{b}\left({A}_{{nn}}^{a}-{A}_{{mm}}^{a}\right)\), where \({A}_{{nn}}^{a}\) is the intraband Berry connection. The group velocity difference is \({\Delta }_{{nm}}^{a}=v-{v}_{{mm}}^{a}\). The commutative relation between Berry connections is \(\left[{r}_{{mn}}^{b},{r}_{{nm}}^{c}\right]={r}_{{mn}}^{b}{r}_{{nm}}^{c}-{r}_{{mn}}^{c}{r}_{{nm}}^{b}\).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code for PU learning with CGCNN will be released soon on https://github.com/wtolocc/PU_learning_with_CGCNN.

References

Grosso, B. F., Davies, D. W., Zhu, B., Walsh, A. & Scanlon, D. O. Accessible chemical space for metal nitride perovskites. Chem. Sci. 14, 9175–9185 (2023).

Sherbondy, R. et al. High-throughput selection and experimental realization of two new Ce-based nitride perovskites: CeMoN3 and CeWN3. Chem. Mater. 34, 6883–6893 (2022).

Ha, V.-A., Lee, H. & Giustino, F. CeTaN3 and CeNbN3: prospective nitride perovskites with optimal photovoltaic band gaps. Chem. Mater. 34, 2107–2122 (2022).

Zi, X. et al. First-principles study of ferroelectric, dielectric, and piezoelectric properties in the nitride perovskites CeBN3 (B = Nb, Ta). Phys. Rev. B. 109, 115125 (2024).

Ghosh, S. & Chowdhury, J. Predicting band gaps of ABN3 perovskites: an account from machine learning and first-principle DFT studies. RSC Adv. 14, 6385–6397 (2024).

Fuertes, A. Nitride tuning of transition metal perovskites. APL Mater. 8, 020903 (2020).

Han, J. et al. Effect of the A-site cation on the lattice thermal conductivity of nitride perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 20505–20511 (2024).

Jacoby, M. Introducing polar nitride perovskites. Chem. Eng. N. 100, 12 (2022).

Smaha, R. W. et al. GdWN3 is a nitride perovskite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 112902 (2024).

Geng, S. & Xiao, Z. Can nitride perovskites provide the same superior optoelectronic properties as lead halide perovskites?. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2051–2057 (2023).

Flores-Livas, J. A., Sarmiento-Perez, R., Botti, S., Goedecker, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Rare-earth magnetic nitride perovskites. J. Phys. Mater. 2, 025003 (2019).

Gui, C., Chen, J. & Dong, S. Multiferroic nitride perovskites with giant polarizations and large magnetic moments. Phys. Rev. B 106, 184418 (2022).

Peng, Y., Deng, Z., Song, S., Tang, G. & Hong, J. First-principles investigation of auxetic piezoelectric effect in nitride perovskites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 27, 10652–10659 (2025).

Zhou, X. et al. Polar nitride perovskite LaWN3- δ with orthorhombic structure. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205479 (2023).

Talley, K. R., Perkins, C. L., Diercks, D. R., Brennecka, G. L. & Zakutayev, A. Synthesis of LaWN3 nitride perovskite with polar symmetry. Science 374, 1488–1491 (2021).

Pohls, J.-H. et al. Experimental validation of high thermoelectric performance in RECuZnP2 predicted by high-throughput DFT calculations. Mater. Horiz. 8, 209–215 (2021).

Emery, A. A. & Wolverton, C. High-throughput DFT calculations of formation energy, stability and oxygen vacancy formation energy of ABO3 perovskites. Sci Data 4, 170153 (2017).

Diao, X. et al. High-throughput screening of stable and efficient double inorganic halide perovskite materials by DFT. Sci Rep. 12, 12633 (2022).

Khandy, S. A. & Gupta, D. C. Investigation of structural, magneto-electronic, and thermoelectric response of ductile SnAlO3 from high-throughput DFT calculations. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 117, e25351 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Design of organic–inorganic hybrid heterostructured semiconductors via high-throughput materials screening for optoelectronic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 16656–16666 (2022).

Gill, D., Bhumla, P., Kumar, M. & Bhattacharya, S. High-throughput screening to modulate electronic and optical properties of alloyed Cs2AgBiCl6 for enhanced solar cell efficiency. J. Phys. Mater. 4, 025005 (2021).

Quan, L. N. et al. Ligand-stabilized reduced-dimensionality perovskites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2649–2655 (2016).

Wang, T., Li, J., Jin, H. & Wei, Y. Tuning the electronic and magnetic properties of InSe nanosheets by transition metal doping. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 7532–7537 (2018).

Setayandeh, S. S. et al. A DFT study to determine the structure and composition of e-W2B5-x. J. Alloys Compd. 911, 164962 (2022).

Ghosh, G. Phase stability and cohesive properties of Au-Sn intermetallics: a first-principles study. J. Mater. Res. 23, 1398–1416 (2008).

Pohls, J.-H., Heyberger, M. & Mar, A. Comparison of computational and experimental inorganic crystal structures. J. Solid State Chem. 290, 121557 (2020).

Jang, J., Gu, G. H., Noh, J., Kim, J. & Jung, Y. Structure-based synthesizability prediction of crystals using partially supervised learning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18836–18843 (2020).

Mordelet, F. & Vert, J.-P. A bagging SVM to learn from positive and unlabeled examples. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 37, 201–209 (2014).

Bekker, J. & Davis, J. Learning from positive and unlabeled data: a survey. Mach. Learn. 109, 719–760 (2020).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Schmidt, J., Pettersson, L., Verdozzi, C., Botti, S. & Marques, M. A. L. Crystal graph attention networks for the prediction of stable materials. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7948 (2021).

Cheng, G., Gong, X.-G. & Yin, W.-J. Crystal structure prediction by combining graph network and optimization algorithm. Nat. Commun. 13, 1492 (2022).

Choudhary, K. & DeCost, B. Atomistic line graph neural network for improved materials property predictions. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 185 (2021).

Karamad, M. et al. Orbital graph convolutional neural network for material property prediction. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 093801 (2020).

Louis, S.-Y. et al. Graph convolutional neural networks with global attention for improved materials property prediction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 18141–18148 (2020).

Nunez, A. S., Duine, R. A., Haney, P. & MacDonald, A. H. Theory of spin torques and giant magnetoresistance in antiferromagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. B. 73, 214426 (2006).

Isidori, A. Altermagnetism arising from a spontaneous electronic instability. Commun. Mater. 5, 134 (2024).

Guk, Y.-S., Ryu, D.-C., Kim, B. & Kang, C.-J. Altermagnetism: fundamental concepts, experimental discoveries, and future directions. J. Korean Magn. Soc. 34, 151–158 (2024).

Rathore, D. Altermagnetism: symmetry-driven spin splitting and its role in spintronic technologies. J. Alloy. Compd. 1034, 181292 (2025).

Sun, W. et al. Designing spin symmetry for altermagnetism with strong magnetoelectric coupling. Adv. Sci. 12, e03235 (2025).

Pan, B. et al. General stacking theory for altermagnetism in bilayer systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 166701 (2024).

Sun, W. et al. Altermagnetism induced by sliding ferroelectricity via lattice symmetry-mediated magnetoelectric coupling. Nano Lett. 24, 11179–11186 (2024).

Khan, I., Bezzerga, D., Marfoua, B. & Hong, J. Altermagnetism, piezovalley, and ferroelectricity in two-dimensional Cr2SeO altermagnet. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 9, 18 (2025).

Khan, I., Bezzerga, D. & Hong, J. Coexistence of altermagnetism and robust ferroelectricity in a bulk MnO wurtzite structure. Mater. Horiz. 12, 2319–2327 (2025).

Sun, W. et al. Proposing altermagnetic-ferroelectric type-III multiferroics with robust magnetoelectric coupling. Adv. Mater. 37, 2502575 (2025).

Davies, D. W., Butler, K. T., Isayev, O. & Walsh, A. Materials discovery by chemical analogy: role of oxidation states in structure prediction. Faraday Discus. 211, 553–568 (2018).

Davies, D. et al. SMACT: semiconducting materials by analogy and chemical theory. JOSS 4, 1361 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Liu, C., Chen, Y. & Dames, C. Electric-field-controlled thermal switch in ferroelectric materials using first-principles calculations and domain-wall engineering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 044002 (2019).

Acharya, M. et al. Exploring the Pb1-xSrxHfO3 system and potential for high capacitive energy storage density and efficiency. Adv. Mater. 34, 2105967 (2022).

Young, S. M., Zheng, F. & Rappe, A. M. First-principles calculation of the bulk photovoltaic effect in bismuth ferrite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 236601 (2012).

Young, S. M. & Rappe, A. M. First principles calculation of the shift current photovoltaic effect in ferroelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 116601 (2012).

Laman, N., Bieler, M. & Van Driel, H. M. Ultrafast shift and injection currents observed in wurtzite semiconductors via emitted terahertz radiation. J. Appl. Phys. 98, 103507 (2005).

Blochl, P. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. & Pack, J. Special points for brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Paier, J. et al. Screened hybrid density functionals applied to solids. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 154709 (2006).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with Phonopy and Phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2023).

Togo, A., Chaput, L., Tadano, T. & Tanaka, I. Implementation strategies in phonopy and phono3py. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 35, 353001 (2023).

Wan, W., Liu, C., Xiao, W. & Yao, Y. Promising ferroelectricity in 2D group IV tellurides: a first-principles study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 132904 (2017).

Souza, I., Íñiguez, J. & Vanderbilt, D. First-principles approach to insulators in finite electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 117602 (2002).

Fu, H. & Bellaiche, L. First-principles determination of electromechanical responses of solids under finite electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 057601 (2003).

Cowley, R. A. Structural phase transitions I. Landau theory. Adv. Phys. 29, 1–110 (1980).

Fei, R., Kang, W. & Yang, L. Ferroelectricity and phase transitions in monolayer group-IV monochalcogenides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 097601 (2016).

Sipe, J. E. & Shkrebtii, A. I. Second-order optical response in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 61, 5337–5352 (2000).

von Baltz, R. & Kraut, W. Theory of the bulk photovoltaic effect in pure crystals. Phys. Rev. B 23, 5590–5596 (1981).

Ibañez-Azpiroz, J., Tsirkin, S. S. & Souza, I. Ab initio calculation of the shift photocurrent by Wannier interpolation. Phys. Rev. B 97, 245143 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the Shenzhen Natural Science Fund (the Stable Support Plan Program 20231121110218001) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M742403) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J. and T.W. conceived the central ideas, designed the overall workflow, and developed the ML model. T.W. and J.L. carried out the DFT calculations. T.W. and H.J. prepared the initial manuscript draft, and H.J. and B.W. supervised the research. All authors contributed to data analysis, interpretation of results, and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Li, J., Wang, B. et al. PU-learning-guided discovery of synthesizable multiferroic nitride perovskites with altermagnetic order. npj Comput Mater 11, 386 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01876-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01876-z