Abstract

Advances in machine learning have transformed materials discovery, yet challenges remain due to the lack of informatics-ready data and the complexity of numerical descriptors. Scientific knowledge is scattered across publications, making comprehensive data extraction difficult. This study presents a large language model (LLM)-driven framework to accelerate organic solar cell (OSC) materials discovery by extracting structured data from literature and predicting device performance using natural language embeddings. Trained on a curated dataset of 422 OSC devices, the fine-tuned LLM demonstrated strong predictive accuracy across key performance metrics: power conversion efficiency (PCE, R2: 0.87), short-circuit current (JSC, R2: 0.82), open-circuit voltage (VOC, R2: 0.89), and fill factor (FF, R2: 0.59). The models are then used to explore the space of 1.4 million combinations of materials, experimental variables and device architectures. The analysis provides data-driven design guidelines, identifying optimal donor-acceptor combinations and processing conditions that consistently yield higher device performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic solar cells (OSCs) are pioneering renewable energy technologies, offering unique advantages such as lightweight design, semitransparency, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness. These features make OSCs ideal for diverse applications, including wearable electronics, building-integrated photovoltaics, and solar power fabrics1,2,3. Despite this remarkable progress, a critical gap persists, with OSCs trailing behind their inorganic counterparts in terms of both efficiency and stability4,5. The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of an OSC is the ratio of maximum electrical power output to incident light intensity under standard conditions, which is determined by the open-circuit voltage (VOC), short-circuit current (JSC), and fill factor (FF). VOC primarily depends on the energy offset between the donor’s HOMO and the acceptor’s LUMO6 but is also influenced by electrode work function7, active layer composition, and device architecture. JSC is governed by light absorption, determined by its optical bandgap, while the fill factor (FF) reflects charge carrier extraction efficiency, influenced by carrier mobility and recombination. Since these parameters are highly sensitive to device architecture, material properties, and processing conditions, achieving precise control remains a significant challenge.

OSCs typically rely on organic semiconductor polymers or small molecules with a π-conjugated carbon backbone, enabling the delocalization of electrons across the molecular structure8. This unique configuration facilitates light absorption in the visible and near-infrared regions. However, the challenge arises from the low dielectric constant of organic materials, leading to the formation of Frenkel excitons with a high hole-electron binding energy instead of generating free charge carriers upon photon absorption. To overcome the inherent limitation, organic solar cells employ a combination of electron donor and acceptor materials, creating a junction where the energy offsets between them drive the separation of the hole-electron pair. While this strategy proves effective, bilayer devices often face challenges due to a high rate of hole-electron recombinations. Addressing this issue requires the use of a blend-an interpenetrating network of donor and acceptor materials. This approach significantly enhances the efficiency of charge carrier separation and transport, ensuring optimal performance in OSCs.

While fullerene and its derivatives have been widely used as acceptors in combination with donors, they come with significant drawbacks. These include limited energy level tunability, poor absorption ability, and poor thermal stability, often leading to excessive aggregation under thermal stress9. In contrast, non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) are considered superior due to their facile energy level tuning through molecular modification, providing desired orbital energies and a narrow bandgap with broader absorption10. Unlike the isotropic charge transport observed in fullerenes, NFAs facilitate intermolecular charge transport, thanks to favorable π-π stacking between neighboring molecules. The rigid molecular structure of NFAs not only ensures good molecular planarity but also side-chain engineering offers greater control over the film’s morphology, presenting more opportunities for optimizing the performance of OSCs.

The performance of OSCs is heavily influenced by the morphology of the bulk heterojunction (BHJ) active layer, which plays a pivotal role in two critical processes: (1) exciton diffusion and (2) charge transport and collection11. Given the relatively short lifetime and diffusion length of excitons in organic materials, it’s essential to maintain a recommended domain size within the range of 5-30 nm to ensure efficient dissociation into free-charge carriers. Moreover, achieving high domain purity and a fine 3D bicontinuous interpenetrating network of donor-acceptor materials is crucial for facilitating rapid carrier transport to transport layers or electrodes while limiting charge recombination. Tuning the nanomorphology of the active layer can be accomplished through molecular design strategies for donor and acceptor polymers/molecules, such as optimizing regioregularity12,13,14, molecular weight15,16, side chains17,18, and molecular backbone19,20, which influence molecular packing and phase separation. Additionally, the blending ratio of organic materials significantly impacts morphology and is often optimized for specific combinations of donor and acceptor components21. The choice of processing solvent also plays a vital role in film morphology, as it affects the solubility of organic components and the film-forming dynamics22,23,24. Furthermore, the incorporation of additives21,23, not exceeding 3% of the solution volume, has been shown to benefit nanomorphology. Post-treatments such as thermal annealing and solvent vapour annealing can further refine crystallinity, domain size, and phase separation of the active layer, making them frequently employed techniques for optimizing nanomorphology in OSCs25,26,27,28.

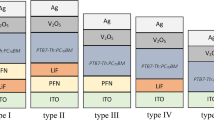

In addition to advancements in tuning the active layer, significant efforts have been directed towards modifying the conventional device architecture of OSCs29. This has led to the design of inverted OSCs, a transformative approach that enhances stability and further reduces costs by circumventing the energy-intensive deposition of the top metal electrode. In traditional OSCs, the organic layer is sandwiched between a low work function metal electrode (such as aluminum, calcium, or barium) and a high work function transparent conducting anode (typically indium-tin oxide). In contrast, inverted OSCs utilize a transparent electrode as the cathode, with high work function metals like gold, silver, or copper serving as the top anode.

In the realm of OSCs, a majority of devices reported in the literature are of small device size, presenting several challenges when it comes to scaling up to large-area devices30. While spin-coating remains the predominant solution-based technique for OSC fabrication due to its simplicity and reproducibility, it is incompatible with large-scale continuous roll-to-roll (R2R) production. Consequently, scalable techniques such as blade-coating, slot-die coating, gravure printing, and inkjet printing are being explored30,31. However, OSCs fabricated using these techniques often exhibit lower PCE compared to spin-coating-based devices, primarily due to difficulties in controlling uniformity, thickness, and crystallization. For large-scale production, thick-active layers are preferred as they can capture more light and are compatible with scalable printing techniques32,33. Therefore, there is a need to identify spin-coated OSCs that exhibit thickness-independent characteristics. Additionally, the use of halogenated solvents and additives in OSC fabrication poses environmental concerns. Hence, efforts are underway to transition towards the development and adoption of non-halogenated green solvents and additives for large-scale production, aligning with sustainability objectives11.

Due to the inherent complexity of designing OSCs, data-driven approaches have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional hit-and-trial methods. Using labeled data collected from the literature, numerous machine-learning (ML) models have been developed to screen candidate materials based on chemical fingerprints derived from donor and acceptor structures and energy-level descriptors34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. Notably, a deep learning-assisted framework integrating graph neural networks with improved polymer fingerprint representations demonstrated high accuracy and good generalizability for predicting key OSC performance metrics45. Similarly, Sun et al. developed DeepAcceptor, combining graph-based representations with a customized BERT model (abcBERT), achieving an MAE of 1.78 and R2 of 0.67 for PCE prediction of small-molecule acceptors46. While these studies have advanced materials screening, they continue to face limitations, including (1) limited training data and (2) reliance on complex numerical fingerprints, with most models primarily focusing on structural features or intrinsic material properties while overlooking crucial processing parameters and device architectures. Addressing this specific gap, Wang et al.47 developed ML models based on processing parameters and achieved an R2 of 0.977 for PCE prediction in all-small-molecule BHJ solar cells, though their applicability was restricted to squaraine-based donor systems. Their study highlighted donor-acceptor ratio and annealing temperature as key performance-determining factors, emphasizing the importance of incorporating processing conditions into future ML frameworks.

Large Language Models (LLMs) offer a transformative approach for literature data extraction48,49 and property prediction50,51 by generating embeddings directly from natural language. While LLM-based tools like ChatExtract48 have shown impressive success for inorganic materials, and our recent work50 combining NER-based MaterialsBERT and GPT-3.5 has advanced polymer data extraction, their application to OSC materials remains unexplored. Additionally, LLMs have been fine-tuned for predicting polymer thermal52 and solubility51 properties using only SMILES representations. A similar strategy could be extended to OSCs by incorporating not just SMILES, but also device architecture and processing conditions - all of which critically influence device performance. Unlike traditional ML approaches that require large labeled datasets, engineered features, and machine-readable representations, LLM-based methods leverage natural language and transfer learning, greatly simplifying data preparation and model development for complex materials systems.

In this work, we leveraged LLMs to accelerate data extraction from the literature, including information on device performance, architecture, materials, and processing conditions. Following rigorous data curation and optimized prompt engineering, a fine-tuned LLM was developed to predict device performance. This model was subsequently used to explore a design space of 1.4 million candidates, providing insights into optimal experimental conditions, device architectures, and material selection. These findings highlight the potential of LLMs to significantly accelerate the design and optimization of OSCs, while offering a generalizable framework applicable across a broad range of materials and applications.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the workflow employed in this study. The required data-including device performance, chemical structures of organic materials, device architecture, and processing conditions-are scattered across research papers, making manual extraction highly challenging and time-consuming. To overcome this challenge, LLMs were strategically deployed with tailored prompts to efficiently extract the required information from the literature. The complete data extraction pipeline, along with details of curation and the training dataset, is provided in the Methods section. Following meticulous data curation, the extracted data was used to fine-tune an LLM to predict device performance in terms of PCE, JSC, VOC, and FF.

LLM fine-tuning strategy for predictive modeling

We employed TinyLlama-1.1B53 for model training, as its compact size (1.1 billion parameters) offers a favorable balance between computational efficiency and representational capacity, making it well-suited to capture the required semantic relationships given our limited dataset size. The dataset was divided into training and test sets, with five different splits considered to ensure robust generalization. The model was fine-tuned using Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA)54, which freezes the pre-trained model weights and injects trainable rank decomposition matrices into each layer of the transformer architecture, significantly reducing the number of trainable parameters for downstream tasks. The training data were used to fine-tune the model, and its performance was evaluated against the test set to assess predictive accuracy and generalization capabilities. To optimize performance, hyperparameters were systematically varied, including the number of epochs (10 to 120), rank (r) (8 to 128), and alpha (α), which was set to either the same as or half of the rank. The optimal hyperparameters were selected based on performance metrics averaged across all five splits, ensuring a robust and efficient property prediction model.

The prompt for predicting PCE was carefully crafted to capture the key parameters influencing device performance. Various prompts were tested to ensure clear and concise retrieval of all necessary information. Following systematic prompt engineering, the optimal version used for PCE prediction is shown in Fig. 2. This prompt specifically incorporates smiles_donor and smiles_acceptor, which represent the SMILES strings of donor and acceptor materials, respectively. Additionally, blend_ratio denotes the ratio between donor and acceptor in the active layer, while solvent specifies the solvent name, including percentages when multiple solvents or additives are involved. The processing_technique describes the thin-film preparation method, such as “spin coating” and “doctor blade coating”. For thermal annealing (TA) or solvent vapor annealing (SVA), the prompt captures specific conditions (e.g., “TA at 150° for 10 minutes”) when applicable. Furthermore, thickness indicates the active layer’s thickness in nm, and molecular_weight corresponds to the polymer’s molecular weight in g/mol. In cases where values for blend_ratio, solvent, processing_technique, TA, SVA, thickness, or molecular_weight were missing from the literature, the corresponding entries in the prompt were assigned the label “Unknown”. The start and end tokens, <S> and </S>, were used to delimit the input sequence. During fine-tuning, the PCE value was provided but omitted during prediction. Notably, for predicting other device properties such as JSC, VOC, and FF, a similar prompt structure was employed, with the target property adjusted accordingly.

Prompt for predicting power conversion efficiency (PCE). smiles_donor and smiles_acceptor are SMILES strings for donor and acceptor materials, respectively. blend_ratio denotes the ratio between donor and acceptor in the active layer. solvent specifies the solvent name, including percentages if multiple solvents or additives are present. processing_technique indicates the thin-film preparation method, such as “spin coating”. For thermal annealing (TA) or solvent vapor annealing (SVA), if True, provide the condition, for example “TA at 150°C for 10 minutes”. thickness_nm represents the active layer’s thickness in nm, while molecular_weight is the polymer’s molecular weight in g/mol. If information for blend_ratio, solvent, processing_technique, TA, SVA, thickness_nm, or molecular_weight is unavailable, it is marked as unknown. During fine-tuning, the PCE value is provided but omitted during prediction. < s > and < /s > denote start and end tokens. For JSC, VOC, and FF, similar prompts are used, with PCE replaced by the corresponding property.

Model performance

The fine-tuned TinyLlama-1.1B model demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting key device parameters for OSCs, including PCE, JSC, VOC, and FF. Figure 3a illustrates the model’s performance for the best set of hyperparameters, highlighting the consistency between train and test R2 values for PCE and other device parameters. The models were trained and evaluated on five different splits for each parameter, and the best set of hyperparameters were chosen based on the average R2 values to ensure predictive accuracy and generalization. Detailed model performance, including average R2 values across all five splits with varying epochs, rank (r), and alpha (α) for train/test sets, is provided in SI Figs. S5–S12.

a Bar plot of average R2 values for Train and Test sets across five splits for PCE, JSC, VOC, and FF, with error bars indicating the range of R2 values. Parity plots comparing predicted and actual values for Train and Test sets in a representative split: b PCE, c JSC, d VOC, and e FF. Insets in each plot show the distribution of prediction errors, calculated as the difference between predicted and actual values.

For PCE, the optimal configuration was achieved with r = 16, α = 16, and 100 training epochs. Under these conditions, the model delivered an impressive average test R2 of 0.83, ranging from 0.77 to 0.92. The high predictive capability across multiple data splits underscores the model’s robustness and generalization. A representative parity plot for a single split is shown in Fig. 3b, where the model achieved R2, RMSE, and Pearson correlation coefficient (r) values of 0.96/0.92, 0.64/1.06, and 0.98/0.96 for the train/test sets, respectively. The inset shows an error distribution plot of predicted PCE minus actual PCE, indicating a nearly normal distribution.

The model also demonstrated high predictive accuracy for JSC, achieving the best performance with r = 128, α = 64, and 50 training epochs. The average test R2 was 0.81, with a standard deviation of 0.10 across the splits, indicating reliable generalization. A corresponding parity plot for a single split is presented in Fig. 3c. For VOC, the optimal configuration involved r = 32, α = 32, and 60 training epochs, yielding an average test R2 of 0.83. The model maintained consistent performance across different data splits, with values ranging from 0.78 to 0.87, as depicted in Fig. 3a, d. In contrast, the model exhibited comparatively lower performance for FF. The best results were obtained using r = 64, α = 32, and 120 training epochs, achieving an average test R2 of 0.60 with a broader variability (range: 0.46 to 0.81, median: 0.56). The model’s lower performance in predicting FF can be attributed to the complex interplay of multiple factors influencing FF, including series resistance (Rs), shunt resistance (Rsh), charge recombination, carrier mobility, and interfacial effects, all of which intricately interact and make FF less understood compared to VOC and JSC55,56,57. Despite this, the model effectively captured the essential trends for FF prediction. Figure 3e shows a parity plot for FF, where R2, RMSE, and r values for the train/test sets were 0.90/0.81, 0.04/0.06, and 0.95/0.90, respectively. The error distributions of predicted minus actual values for all models, shown in the insets, exhibit a nearly normal distribution without noticeable skewness. This indicates unbiasedness in the predictions, confirming the reliability and accuracy of the models.

Overall, the fine-tuned TinyLlama-1.1B model demonstrated outstanding predictive accuracy and generalization for PCE, JSC, and VOC, highlighting its potential to accelerate materials discovery for organic photovoltaics. Finally, production-ready models were developed by fine-tuning TinyLlama-1.1B on the full dataset using the optimal hyperparameters identified in the preceding analysis, making them ready for downstream predictions.

It is worth noting, however, that although the current dataset covers a diverse range of donor/acceptor materials—including 21 NFAs—and a variety of processing conditions, it does not yet include some of the most recent high-performance Y-series58 NFAs. A substantial amount of relevant data remains embedded in the literature, particularly in supplementary information files, and incorporating this will further strengthen model performance. Future work will focus on expanding the dataset and refining the data extraction pipeline to incorporate ternary and higher-order OSC systems, as well as additional process parameters such as the rotational speed of spin coating, effective device area, and electrode materials. These efforts will further enhance the model’s predictive capabilities and generalizability.

Optimizing materials and processing conditions

The developed models were employed to investigate the parameter space encompassing donor-acceptor material combinations, experimental conditions, and device architectures. To manage computational costs, a defined subset of variables was selected, including five donor and five acceptor materials (both fullerene and non-fullerene types). The donor-acceptor blend ratio was varied systematically across 20 values ranging from 0.17 to 2.0, with most increments of 0.1. Solvents included o-dichlorobenzene and chlorobenzene, both with and without 2% DIO additives. Thermal annealing temperatures ranged from 25 °C to 180 °C in 10 °C increments for a duration of 10 minutes, while the active layer thickness was varied from 50 nm to 250 nm in steps of 10nm. Both conventional and inverted device architectures were considered. Parameters such as film processing technique were kept constant with no solvent vapor annealing, and polymer molecular weight was marked as “Unknown”. This comprehensive combination of variables resulted in a dataset comprising 1.4 million samples, which was utilized to predict PCE using the developed model.

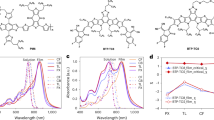

Figure 4a presents a heatmap of the predicted PCEs for combinations of five donors and five acceptors under optimal processing conditions. Notably, the donor D2 blended with acceptor A1 is predicted to achieve a PCE of 16% at a blend ratio of 1.87, with a film thickness of 140 nm, processed in a solvent mixture of 98% o-dichlorobenzene (DCB) and 2% DIO, and annealed at 25 °C for 10 minutes in an inverted architecture. Meanwhile, the same donor D2, when paired with acceptor A5, is predicted to yield a maximum PCE of 14.6% under a different set of optimized conditions, suggesting a pathway for achieving optimal performance.

The screening results using our fine-tuned LLM revealed several key factors influencing the PCE of OSCs, as summarized in Table 1. Apart from identifying the top three donor-acceptor combinations (D2-A1, D2-A5, and D4-A3), the model highlighted the critical role of 2% DIO additives, which consistently enhanced device performance when combined with solvents such as o-dichlorobenzene and chlorobenzene. This trend is exemplified in Fig. 4c for the D2-A1 system, with comparable improvements observed across other combinations. The average optimal film thickness was determined to be 100 nm. Figure 4d illustrates the variation of PCE with respect to film thickness in inverted device architectures. Devices with active layers thinner than 50nm exhibited poor performance, while increasing the thickness initially led to improved efficiency. However, a noticeable decline in PCE was observed as the thickness increased beyond 100 nm, which aligns with the established understanding that thicker films increase the likelihood of exciton trapping and hinder charge transport. Similar trends were also observed in conventional device architectures, further supporting the robustness of the model’s predictions. Regarding thermal annealing conditions, the optimum was centered around 125 ± 20 °C for 10 minutes, with the majority of instances achieving PCE values exceeding 8% under these conditions. It is important to note that this analysis was limited to annealing durations of 10 minutes, and variations in annealing time were not considered in this study.

a Heatmap of predicted power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) for all combinations of five donor and five acceptor materials under their respective optimal processing conditions. b Chemical structures of selected key donor-acceptor materials. c Comparison of predicted PCEs for the D2-A1 blend with and without the addition of DIO in the processing solvent. d Predicted PCE as a function of film thickness for all donor-acceptor systems for the inverted device architecture.

The donor-acceptor blend ratio was found to be highly system-dependent, with no clear universal trend emerging across different combinations. Additionally, while the model did not identify any significant performance advantage of inverted architectures over conventional ones, it is important to note that inverted architectures are generally considered more stable59,60,61 —a critical factor that was not considered within the scope of this screening.

Discussion

In this work, we introduce a large language model (LLM)-driven informatics framework that bridges the gap between unstructured literature data and predictive modeling for organic solar cell (OSC) materials discovery. By fine-tuning a language model on a curated dataset of 422 OSC devices, we demonstrate that natural language embeddings can serve as powerful descriptors for accurately forecasting key device performance metrics. Our model achieved good predictive performance for power conversion efficiency (PCE), short-circuit current (JSC), open-circuit voltage (VOC), and fill factor (FF). Beyond predictive modeling, we harness the fine-tuned LLM to explore an expansive design space comprising 1.4 million hypothetical combinations of donor-acceptor pairs, processing conditions, and device architectures. This high-throughput screening not only identified the most promising donor-acceptor combinations but also provided valuable data-driven design guidelines, highlighting optimal processing conditions and device configurations that consistently lead to higher device performance.

These results validate the efficacy of the LLM in capturing the complex interdependencies among device architecture, active layer composition, and processing parameters through literature-derived embeddings. By circumventing the need for traditional numerical descriptors, the proposed framework provides a scalable and adaptable approach for predicting OSC performance under diverse conditions, thereby accelerating the discovery of next-generation sustainable energy materials. More broadly, this work establishes a generalizable paradigm for employing LLMs in materials science, where language-derived representations not only substitute for numerical descriptors but also serve as powerful tools for knowledge extraction and exploratory analysis.

Methods

Literature data mining via a semi-automated LLM-based Pipeline

To capture OSC performance comprehensively, our data collection strategy targets key device metrics, including PCE, VOC, JSC, and FF. We account for various influencing factors, such as device architecture (conventional or inverted), active layer components, thickness, and molecular properties. Additionally, factors influencing thin-film morphology-such as solvent choice, deposition methods, annealing conditions, additives, and co-solvents-were also taken into account.

We developed a data extraction pipeline to systematically retrieve structured information on OSC materials from scientific literature. A schematic overview of the workflow is presented in Fig. 5. This pipeline integrates advanced natural language processing (NLP) models and heuristic algorithms to extract key details, including device architecture, morphology, active layers, and material properties. It begins with named entity recognition (NER) using MaterialsBERT62, a BERT-based model tailored for materials science, to identify relevant entities such as material names, device components, and property values. The pipeline then scans each paragraph, generating a list of recognized entities and their corresponding tags, which are subsequently aggregated for consistent and accurate extraction, and eliminate irrelevant paragraphs. To complement NER, the pipeline utilizes heuristic methods with regular expressions and context-specific keywords to categorize device architectures and processing techniques, while NLP-based queries and LLM-driven extraction identify active layer components and device properties along with their values and units. To enhance extraction accuracy, the pipeline integrates Llama-350,63, formulating context-aware queries to request tabular representations of material properties, processing techniques, and performance metrics. The extracted data is then normalized and structured for subsequent analysis, ensuring consistency and uniformity across varied terminologies used in different articles. Additionally, the pipeline supports the extraction of tabular data by parsing tables from the literature, inferring the semantic meaning of table columns, and reconfiguring them into structured datasets.

By leveraging the combined capabilities of NLP models, heuristic rules, and LLM integration, the pipeline effectively extracted comprehensive datasets from diverse scientific articles, including detailed information on device architectures, material properties, processing techniques, and morphological characterizations. Throughout the process, human supervision was always involved, ensuring that the pipeline functioned as a supportive tool, with overall accuracy reflecting human accuracy. An example snapshot of the portal is provided in Figs. S1–S3, illustrating how it collects data with an example paper. It is worth noting that experimental details with varying parameters are often provided within the Supplementary Information (SI) sections, which are largely unstructured and available in different file formats. As the pipeline does not support processing SI documents, these were meticulously collected through human effort.

Data curation

To prepare the extracted data ready for LLMs, further curation is required to correct any errors introduced by the pipeline and to obtain Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings for the organic materials in the active layer. SMILES strings provide a standardized notation for encoding molecular structures. Among all curation steps, the generation of SMILES strings proved to be the most time-consuming. The dataset includes devices with conventional and inverted architectures, small molecules and polymers in the active layer, donor-acceptor blend ratios, active layer thickness, solvents (including additives), thin-film coating methods, and post-processing techniques such as thermal and solvent vapor annealing. However, ternary and quaternary devices, as well as those with modified architectures or graphene-based electrodes, were excluded from the dataset.

Given the considerable variability in process conditions reported across different studies, each unique combination of donor, acceptor, and process parameters associated with a reported performance metric (e.g., PCE) was treated as an independent data instance. This approach preserves the context-dependent nature of device performance and allows the model to learn how specific process variables influence outcomes. Furthermore, in cases where multiple PCE values were reported for the same material pair and processing conditions, the average value was used to avoid optimistic bias and better represent the expected device performance under those conditions.

Dataset

The dataset comprises 422 data points for BHJ solar cells with two components in the active layer. The dataset includes 73 unique donors, 42 unique acceptors, and 120 distinct donor-to-acceptor (D:A) combinations. Key device performance metrics-PCE, JSC, VOC, and FF-were collected, and the corresponding histograms are shown in Fig. 6a-d. As can be seen, PCE values exhibit considerable variability, ranging from a low of 0.02% to a high of 13%, with a median of 4.12%. JSC spans from 0.07 mA/cm2 to 24.50 mA/cm2, with a median of 9.93 mA/cm2, reflecting wide variation in current output. VOC shows moderate variation, ranging from 0.24 V to 1.36 V and centered around 0.75 V. The fill factor spans from 0.20 to 0.83 with a median of 0.61.

Histogram plots showing the distribution of (a) PCE, b VOC, c JSC, d FF, e donor-acceptor blend ratio, f active layer film thickness, and g molecular weight of donor polymers. h Bar plot illustrating the counts for conventional versus inverted solar cell architectures, presence or absence of 1,8-diiodooctane (DIO) in the solvent, and whether thermal or solvent vapor annealing was performed. i Histogram of thermal annealing temperatures.

The dataset includes important experimental parameters such as the donor-acceptor blend ratio, the thickness of the active layer, and the molecular weight of the donor materials, all of which exhibit considerable variability, as depicted in Fig. 6e-g. The blend ratio, calculated as the donor-to-acceptor ratio, which ranges from 0.17 to 3.00. Most data points are concentrated around the lower range, with 25% of the values falling below 0.67 and 75% below 1.00, suggesting a prevalence of lower blend ratios in the dataset. The active layer thickness spans from 50 nm to 480 nm, with a median of 100 nm. While the data distribution is centered around thinner layers, with 75% of the data falling below 137.5 nm, the standard deviation (63.96 nm) reveals significant variability in thickness. The molecular weight of donor polymers is heavily skewed toward lower molecular weights, as 75% of the values fall below 83,000 g/mol. As shown in Fig. 6h, i, thermal annealing was performed on 117 samples, with temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 180 °C and annealing times varying from 2 to 30 minutes. Solvent vapor annealing (SVA) was conducted on 30 samples, with varying solvent types and processing conditions. The processing solvents used include chlorobenzene, dichlorobenzene, trichlorobenzene, chloroform, xylene, ethanol, and their combinations. Additionally, 1,8-diiodooctane (DIO) was used as an additive in 123 cases to improve film morphology. The dataset reports two film coating methods: (i) spin coating and (ii) doctor-blade coating. Lastly, device architecture was reported for 358 samples, with 67 employing an inverted architecture and the remaining following a conventional design.

Among the device performance metrics, strong correlations were observed between PCE and JSC (r = 0.95), PCE and FF (r = 0.79), and JSC and FF (r = 0.69), consistent with previously reported trends(see Fig. S4 in SI)64,65. However, the correlations between VOC and PCE, JSC, or FF are poor, indicating that the factors influencing VOC are likely distinct from those governing the other performance parameters.

Data availability

The training dataset used in this study is publicly available at OPVPerfPredictor GitHub repository. The same repository also provides the fine-tuned model weights and a script to predict device performance for new cases.

References

Constantinou, S., Al-naemi, F., Alrashidi, H., Mallick, T. & Issa, W. A review on technological and urban sustainability perspectives of advanced building-integrated photovoltaics. Energy Sci. Eng. 12, 1265–1293 (2024).

Solak, E. K. & Irmak, E. Advances in organic photovoltaic cells: a comprehensive review of materials, technologies, and performance. RSC Adv. 13, 12244–12269 (2023).

Tripathy, M., Sadhu, P. & Panda, S. A critical review on building integrated photovoltaic products and their applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 61, 451–465 (2016).

Riede, M., Spoltore, D. & Leo, K. Organic solar cells-the path to commercial success. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2002653 (2021).

Cheng, P. & Zhan, X. Stability of organic solar cells: challenges and strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2544–2582 (2016).

Qi, B. & Wang, J. Open-circuit voltage in organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 24315–24325 (2012).

Ma, H., Yip, H.-L., Huang, F. & Jen, A. K.-Y. Interface engineering for organic electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 1371–1388 (2010).

Gao, H. et al. Recent progress in all-small-molecule organic solar cells. Small 19, 2205594 (2023).

Speller, E. M. et al. From fullerene acceptors to non-fullerene acceptors: prospects and challenges in the stability of organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 23361–23377 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Lang, Y. & Li, G. Recent advances of non-fullerene organic solar cells: From materials and morphology to devices and applications. EcoMat 5, e12281 (2023).

Zhao, F., Wang, C. & Zhan, X. Morphology control in organic solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1703147 (2018).

Kim, S. W. et al. Synergistic effects of terpolymer regioregularity on the performance of all-polymer solar cells. Macromolecules 52, 738–746 (2019).

Zhong, H. et al. A regioregular conjugated polymer for high performance thick-film organic solar cells without processing additive. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 10517–10525 (2017).

Woo, C. H., Thompson, B. C., Kim, B. J., Toney, M. F. & Fréchet, J. M. J. The influence of poly(3-hexylthiophene) regioregularity on fullerene-composite solar cell performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16324–16329 (2008).

Mori, H., Hara, S., Nishinaga, S. & Nishihara, Y. Solar cell performance of phenanthrodithiophene-isoindigo copolymers depends on their thin-film structure and molecular weight. Macromolecules 50, 4639–4648 (2017).

Ma, P. et al. Optimization of PDTS-DTffBT-based solar cell performance through control of polymer molecular weight. J. Phys. Chem. C. 120, 19513–19520 (2016).

Hu, H. et al. Over 19% efficiency organic solar cells enabled by manipulating the intermolecular interactions through side chain fluorine functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.e202400086 (2024).

Zhang, T. et al. Trifluoro alkyl side chains in the non-fullerene acceptors to optimize the phase miscibility and vertical distribution of organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 8837–8845 (2022).

Wang, J.-L. et al. Difluorobenzothiadiazole-based small-molecule organic solar cells with 8.7% efficiency by tuning of π-conjugated spacers and solvent vapor annealing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1803–1812 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Mobility-controlled performance of thick solar cells based on fluorinated copolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15566–15576 (2014).

Schwaiger, D. M., Lohstroh, W. & Müller-Buschbaum, P. The influence of the blend ratio, solvent additive, and post-production treatment on the polymer dynamics in ptb7:pcbm blend films. Macromolecules 54, 6534–6542 (2021).

Guo, S. et al. Solvent-morphology-property relationship of PTB7:PC71BM polymer solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 3740–3748 (2017).

Wang, J. & Liang, Z. Synergetic solvent engineering of film nanomorphology to enhance planar perylene diimide-based organic photovoltaics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 22418–22424 (2016).

Guo, S. et al. Influence of solvent and solvent additive on the morphology of ptb7 films probed via x-ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 344–350 (2014).

Xie, Y. et al. Post-annealing to recover the reduced open-circuit voltage caused by solvent annealing in organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 6158–6166 (2016).

Harreiß, C. et al. Understanding and controlling the evolution of nanomorphology and crystallinity of organic bulk-heterojunction blends with solvent vapor annealing. Sol. RRL 6, 2200127 (2022).

Lilliu, S. et al. Dynamics of crystallization and disorder during annealing of p3ht/pcbm bulk heterojunctions. Macromolecules 44, 2725–2734 (2011).

Verploegen, E. et al. Effects of thermal annealing upon the morphology of polymer-fullerene blends. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 3519–3529 (2010).

Wang, K., Liu, C., Meng, T., Yi, C. & Gong, X. Inverted organic photovoltaic cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2937–2975 (2016).

Wang, G., Adil, M. A., Zhang, J. & Wei, Z. Large-area organic solar cells: Material requirements, modular designs, and printing methods. Adv. Mater. 31, 1805089 (2019).

Zhang, B., Yang, F. & Li, Y. Recent progress in large-area organic solar cells. Small Sci. 3, 2300004 (2023).

Jin, Y. et al. A novel naphtho[1,2-c:5,6-c’]bis([1,2,5]thiadiazole)-based narrow-bandgap π-conjugated polymer with power conversion efficiency over 10%. Adv. Mater. 28, 9811–9818 (2016).

Jin, Y. et al. Thick film polymer solar cells based on naphtho[1,2-c:5,6-c]bis[1,2,5]thiadiazole conjugated polymers with efficiency over 11%. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700944 (2017).

Shetty, P., Adeboye, A., Gupta, S., Zhang, C. & Ramprasad, R. Accelerating materials discovery for polymer solar cells: Data-driven insights enabled by natural language processing. Chem. Mater. 36, 7676–7689 (2024).

Sahu, H., Rao, W., Troisi, A. & Ma, H. Toward predicting efficiency of organic solar cells via machine learning and improved descriptors. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801032 (2018).

Padula, D., Simpson, J. D. & Troisi, A. Combining electronic and structural features in machine learning models to predict organic solar cells properties. Mater. Horiz. 6, 343–349 (2019).

Mahmood, A., Irfan, A. & Wang, J.-L. Machine learning and molecular dynamics simulation-assisted evolutionary design and discovery pipeline to screen efficient small molecule acceptors for PTB7-th-based organic solar cells with over 15% efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 4170–4180 (2022).

Sun, W. et al. Machine learning-assisted molecular design and efficiency prediction for high-performance organic photovoltaic materials. Sci. Adv. 5, eaay4275 (2019).

Lee, M.-H. Predicting and analyzing the fill factor of non-fullerene organic solar cells based on material properties and interpretable machine-learning strategies. Sol. Energy 267, 112191 (2024).

Zhang, C.-R. et al. Machine learning study on organic solar cells and virtual screening of designed non-fullerene acceptors. J. Appl. Phys. 134, 153104 (2023).

Suthar, R., T, A. & Karak, S. Machine-learning-guided prediction of photovoltaic performance of non-fullerene organic solar cells using novel molecular and structural descriptors. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 22248–22258 (2023).

Huang, D. et al. A machine learning prediction model for quantitative analyzing the influence of non-radiative voltage loss on non-fullerene organic solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 475, 145958 (2023).

Sahu, H. et al. Designing promising molecules for organic solar cells via machine learning assisted virtual screening. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 17480–17488 (2019).

Abbasi Jannat Abadi, E., Sahu, H., Javadpour, S. M. & Goharimanesh, M. Interpretable machine learning for developing high-performance organic solar cells. Mater. Today Energy 25, 100969 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Deep learning-assisted design of novel donor-acceptor combinations for organic photovoltaic materials with enhanced efficiency. Adv. Mater. 37, 2407613 (2025).

Sun, J. et al. Accelerating the discovery of acceptor materials for organic solar cells by deep learning. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 181 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Design of experiments with the support of machine learning for process parameter optimization of all-small-molecule organic solar cells. FlexMat 1, 234–247 (2024).

Polak, M. P. & Morgan, D. Extracting accurate materials data from research papers with conversational language models and prompt engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 1569 (2024).

Dagdelen, J. et al. Structured information extraction from scientific text with large language models. Nat. Commun. 15, 1418 (2024).

Gupta, S., Mahmood, A., Shetty, P., Adeboye, A. & Ramprasad, R. Data extraction from polymer literature using large language models. Commun. Mater. 5, 269 (2024).

Agarwal, S., Mahmood, A. & Ramprasad, R. Polymer solubility prediction using large language models. ACS Mater. Lett. 7, 2017–2023 (2025).

Gupta, S., Mahmood, A., Shukla, S. & Ramprasad, R. Benchmarking large language models for polymer property predictions, Macromol. Rapid Commun. e00388 (2025).

Zhang, P., Zeng, G., Wang, T. & Lu, W. Tinyllama: An open-source small language model (2024). https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.02385.

Hu, E. J. et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models https://arxiv.org/abs/2106.09685 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. High fill factor organic solar cells with increased dielectric constant and molecular packing density. Joule 6, 444–457 (2022).

Qi, B. & Wang, J. Fill factor in organic solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 8972–8982 (2013).

Jao, M.-H., Liao, H.-C. & Su, W.-F. Achieving a high fill factor for organic solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 5784–5801 (2016).

Yang, Y. The original design principles of the y-series nonfullerene acceptors, from y1 to y6. ACS Nano 15, 18679–18682 (2021).

Duan, L. & Uddin, A. Progress in stability of organic solar cells. Adv. Sci. 7, 1903259 (2020).

Chander, N., Singh, S. & Iyer, S. S. K. Stability and reliability of p3ht:pc61bm inverted organic solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 161, 407–415 (2017).

Wang, W. et al. In operando morphology investigation of inverted bulk heterojunction organic solar cells by GISAXS. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 8324–8331 (2015).

Shetty, P. et al. A general-purpose material property data extraction pipeline from large polymer corpora using natural language processing. npj Comput. Mater. 9, 52 (2023).

Grattafiori, A. et al. The llama 3 herd of models https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.21783 (2024).

Sahu, H. & Ma, H. Unraveling correlations between molecular properties and device parameters of organic solar cells using machine learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 7277–7284 (2019).

Nagasawa, S., Al-Naamani, E. & Saeki, A. Computer-aided screening of conjugated polymers for organic solar cell: Classification by random forest. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 2639–2646 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research through grants N00014-19-1-2103 and N00014-20-1-2175.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. was the primary architect of the dataset, models, and screening workflow, and wrote the manuscript. A.M. contributed to the development of the data extraction pipeline. L.S. assisted with data collection. R.R. conceived the project, provided overall guidance, and supervised the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahu, H., Mahmood, A., Shafique, L.B. et al. From Corpus to Innovation: Advancing Organic Solar Cell Design with Large Language Models. npj Comput Mater 12, 27 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01896-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01896-9