Abstract

Correlated materials are known to display qualitatively distinct emergent behaviors at low energy. Conveniently, upon absorbing rapid quantum fluctuations, these rich low-energy behaviors can always be effectively described by dressed particles with fully quantized charge, spin, and orbital structure. Such a powerful and simple description is, however, difficult to access through bare particles used in most many-body computations, especially when fluctuations are strong such as in 4d and 5d compounds. To decipher the dominant quantized structure, we propose an easy-to-implement ‘interaction annealing’ approach that utilizes suppressed charge fluctuation through enhancing ionic charging energy. We establish its theoretical foundation using an exactly treated two-site Hubbard model as a generic example. We then demonstrate its applications with more affordable density functional calculations to a representative 3d Mott insulator La2CuO4 and a highly fluctuating 5d semi-metal WTe2. In the latter, it reveals an emergent local electronic structure that makes possible an unprecedented explanation of several experimental observations. Finally, we demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach in studying competing local electronic structures in functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modern functional materials1,2 display a rich variety of qualitatively distinct behaviors3, sometimes even switchable under weak change of external conditions, such as temperature, pressure, or external fields4,5,6,7. Generically speaking, such rich physical properties are almost always associated with the underlying many-body correlation in the electronic charge, orbital, spin, or lattice degrees of freedom8. Particularly, the ability to qualitatively switch the properties of these functional materials indicates the existence of multiple competing electronic structures with significantly different coupling strengths to various external conditions3,9,10.

For complex systems like these, fortunately, there generally exist effective descriptions capable of exactly capturing the essential low-energy dynamics using only the most relevant quantized degrees of freedom8,11,12,13. Such simplification originates from the discrete energies of states spanning the significantly reduced low-energy subspace8. Consequently, the physically more relevant slow dynamics of the system is rigorously mappable to those of a few dominant many-body objects with quantized valence and orbital structure, upon absorbing rapid quantum fluctuations into their internal structure11,12,13. In explicit many-body treatments, such “dressing” is many-body in nature11,12,13, while in typical density functional theory (DFT)14,15 calculations, these fluctuations are absorbed in “tails” of Wannier orbitals16,17. The existence of such quantized effective description, for example, explains the great success of integer valence count in determining the stability of chemical compounds18,19,20,21,22.

Since these fully quantized dressed objects are the building blocks of the low-energy many-body states, they are essential for an intuitive understanding of the low-energy electronic structure of strongly correlated materials. On the one hand, their dynamics give the observed elementary charge-, orbital-, and spin-excitations of the system. On the other hand, their correlation and ordering define those of the system. As such, their spatial structures correspond to the “form factors” of inelastic and elastic scattering measurements23,24,25. Therefore, seeking these fully quantized dressed objects, as often exercised in chemistry, is not simply for convenience, but rather an important task to gain direct access to the essential low-energy physics.

However, such simple quantized effective descriptions are not easily accessible in standard many-body treatments, when the quantum fluctuation (or hybridization) is strong. Indeed, in terms of bare particles employed in most numerical many-body treatments, the results always contain non-quantized expectation values of charge, orbital, and spin structures26 See Methods for details. It is therefore highly desirable to seek a simple mean for direct access to such fully quantized dressed objects within the existing computational frameworks. Specifically, we aim to find such dressed objects that emerge below the ionic charging energy in functional materials.

Here, to address this important issue, we propose an ‘interaction annealing’ approach easily adaptable in standard many-body computations. We first establish its rigorous theoretical foundation using an exactly treated two-site Hubbard model as a generic example. We then demonstrate its applications with more affordable DFT calculations via two representative examples, 3d Mott insulator La2CuO4 and 5d semi-metal WTe2 that hosts strong charge fluctuation. For the latter, this approach reveals a dominant ferro-orbital order in the DFT ground state, with W ions in a d2 spin-0 orbital-polarized configuration, which explains several experimental observations27,28,29,30. Finally, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach in studying competing local electronic structures, which functionalize many modern materials.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the main idea of our proposed “interaction annealing” approach. Given a system with a dominant interaction that dictates the highest-energy dynamics of the system, for example intra-atomic Coulomb repulsion U, we aim at obtaining the well-quantized dressed objects that constitute its physically most relevant dynamics slower than time scale 2π/U31. To this end, one can suppress the fluctuations through adiabatically32,33,34 (slowly) increasing the interaction, until the bare particles of the fictitious system display well-defined quantization. Owing to the adiabatic connection between low-energy emergent objects belonging to the same stable “fixed point” of slower dynamics35 (in the sense of renormalization group36), the structure of the well-quantized dressed objects, \({\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\), in the real system can be revealed by the bare objects, \({d}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\), of the fictitious system. Below, we establish the theoretical foundation via an exact many-body treatment of a simple model, followed by demonstrations via two representative examples.

Realistic Hamiltonian H for bare particle \({c}_{i}^{\dagger }\) typically contains strong fluctuation that masks the dominant physics. Equivalently, the low-energy dynamics can always be described by fully quantized effective \(\tilde{H}\) upon absorbing rapid fluctuations into dressed particles \({\tilde{c}}_{i}^{\dagger }\). The desired effective description can be obtained through the bare description, \({H}^{{\rm{(a)}}}[\{{d}_{i}^{\dagger }\}]\), of a fictitious `interaction annealed' system with suppressed fluctuation, given \({d}_{i}^{\dagger }\)'s resemblance to the dressed particles \({\tilde{d}}_{i}^{\dagger }\) and the “adiabatic connection” between \({\tilde{d}}_{i}^{\dagger }\) and \({\tilde{c}}_{i}^{\dagger }\) (see text).

Quantized effective description

As a simple yet generic illustration, consider a two-site Hubbard model37,38,

containing two electrons, where t denotes the hopping of particles \({c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }\) at site 1, of spin μ (↑ or ↓), to site 2 and back, and U the charging energy when a site is doubly occupied. Let’s examine the emergent low-energy effective theories (See Methods for details) of this system in its correlated (4t ≤ U) regime.

In this regime, states with doubly occupied orbitals are of high energy. Upon decoupling these states from the remaining low-energy sector via a unitary transformation of the basis39,40,41,42 (denoting − μ as \(\bar{\mu }\) and the site next to i as \({i}^{{\prime} }\)),

into the dressed particles in a “many-body Wannier orbital”, \({\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\), with \({\mathcal{U}}=\exp (\frac{\theta }{2}\,{\sum }_{\mu }\frac{1}{2}({c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{2\mu }-{c}_{2\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{1\mu })({n}_{2\bar{\mu }}-{n}_{1\bar{\mu }}))\) with \(\theta =\arctan (\frac{4t}{U})\), the resulting effective theory for the remaining low-energy subspace,

contains one dressed particle in each site i = 1, 2 interacting via anti-ferromagnetic super-exchange coupling of strength \({\tilde{J}}_{12}=\frac{1}{2}(\sqrt{{U}^{2}+{(4t)}^{2}}-U)\), where \({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{i}={\sum }_{\mu \nu }{\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }{{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_{\mu \nu }{\tilde{c}}_{i\nu }\) denotes the total spin of the dressed particles via Pauli matrices σμν. (See Methods “Obtaining low-energy effective Hamiltonian via numerical canonical transformation” for the transformed full H containing both of the decoupled low- and high-energy sectors).

Notice that the low-energy dynamics of all systems of different U are exactly described by the same effective description, Eq. (3), containing only fully quantized charge, orbital, and spin degrees of freedom (just with different renormalized parameter \({\tilde{J}}_{12}\)). For example, consider a “realistic” system with intermediate 4t/U = 1. For all low-energy eigenstates below the scale of U, the spin \(\langle {\tilde{S}}^{2}\rangle =\frac{3}{4}\) of the dressed particles corresponds to a quantized spin-1/231. In essence, the simplification through quantized effective descriptions rigorously results from fully absorbing the rapid fluctuations into the internal structure of the dressed particles \({\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\), such that dynamics of the latter is no longer sensitive to such fluctuation in their representative time scale (longer than 2π/U). The existence of such fully quantized effective description(s) is therefore a generic characteristic of quantum many-body systems and generally applies to materials with open d- and f-shells having significant intra-atomic interactions.

However, such a fully quantized picture is not directly accessible from properties of bare particles, as typically computed in most many-body calculations. Indeed, for 4t/U = 1, the spin \(\langle {S}^{2}\rangle \sim 0.64 < \frac{3}{4}\) of the bare particles in the ground state deviates significantly from a quantized value, due to strong charge fluctuation, \(\langle {c}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{i\bar{\mu }}^{\dagger }{c}_{i\bar{\mu }}{c}_{{i}^{{\prime} }\mu }\rangle \sim 0.18 > 0\), involving bare particles oscillating between sites and temporarily double-occupying one site.

Adiabatic connection around a dominant structure

To find a simple approach to access such quantized effective description, one can take advantage of the “adiabatic connection”32,33,34 between the low-energy subspace of systems that share identical structure of slow dynamics (c.f. Fig. 1). For example, the above “realistic” system (4t/U = 1) and systems with larger U all share the same Hamiltonian Eq. (3), indicating qualitatively identical low-energy subspace (composed of \({\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\)) between these systems, only with different degree of many-body dressing according to Eq. (2). In technical terms, this means that the renormalization of slow dynamics in these systems shares the same stable “fixed point”35 and therefore they are adiabatically32,33,34 connected.

Furthermore, in systems with larger U (closer to the fixed point), charge fluctuations are systematically suppressed. Therefore, in fictitious “interaction annealed” systems with large enough U, the dressed particles, \({\tilde{d}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\), would become well resembled by the corresponding bare particles \({d}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\).

The above generic properties of many-body emergence together provide direct access to the symmetries and quantum numbers of the dressed particles \({\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\) of a system, through “adiabatically annealing” (slowly increasing) the strength of the dominant interaction (e.g., U) until a clear quantized structure is obtained from the bare \({d}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }\). Indeed, in the above representative example, as U grows from 4t to 20t the charge fluctuation, \(\langle {c}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{i\bar{\mu }}^{\dagger }{c}_{i\bar{\mu }}{c}_{{i}^{{\prime} }\mu }\rangle\) reduces from 0.18 to 0.05, displaying the expected t/U decay. Consistently, 〈S2〉 grows from 0.64 to 0.74, approaching the value \(\frac{3}{4}\) of a well-quantized spin-1/2, exactly revealing the desired fully quantized structure of the dressed particles in the ‘realistic’ system.

Practical applications under uncertainty of the dominant interaction

Recall that the proposed approach aims at obtaining the emergent objects resulting from a “dominant interaction” of the system. Without loss of generality, the above model example has demonstrated the conceptual existence of such effective description via fully quantized emergent objects, and furthermore the robust adiabatic connection between systems of different strength of the dominant interaction, as long as they belong to the same fixed point (namely the dominance of the interaction remains).

In practice, however, which interaction dominates the highest-energy dynamics of a system might not be obvious. (As an example, see Methods “The other (weakly correlated) stable fixed point” for the other fixed point of the model system.) In that case, instead of a super-expensive full-blown many-body RG flow13,43, the proposed approach offers a much affordable route for practical studies. One can simply explore various potential dominant interactions via the proposed approach and compares the corresponding emergent objects against experimental observations (See Section “Application to competing electronic structures” for a demonstration). Given the qualitative distinct characteristics of the emergent objects from different dominant interactions, it is unlikely that more than one of such emergent objects can be consistent with all the observed physical properties of the systems of interest.

Application with density functional theory: 3d Mott insulator La2CuO4

The above “interaction annealing” approach is supported by generic emergent properties of many-body systems and is thus generally applicable to all many-body calculations using bare particle representation, such as variational Monte Carlo44, density matrix renormalization group45, and tensor network46. We now demonstrate with two examples its applicability to more affordable DFT14,15 calculations.

Considering the representative Mott insulator La2CuO4, we employ the standard LDA+U implementation47 that employs an effective Hartree–Fock treatment48. This self-interaction corrected implementation47 accounts for the effective self-interaction in the double counting term, such that the energetic sequence relative to the ligand orbitals is retained upon suppressing charge fluctuations via enlarged U.

With the realistic U = 8 eV49, the one-body density matrix of the anti-ferromagnetic ground state gives a fluctuating \(\langle {d}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{d}_{\downarrow }\rangle \sim 0.31\) for Cu \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbital and \(\langle {p}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{p}_{\downarrow }\rangle \sim 0.91\) for O px-orbital for the minority spin. The un-quantized occupations of the former reflect considerable charge fluctuation \(\langle {d}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{p}_{\downarrow }\rangle \sim 0.22\). Upon slowly increasing U to 20 eV to suppress the charge fluctuation, \(\langle {d}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{p}_{\downarrow }\rangle\) indeed smoothly reduces to 0.14. Correspondingly, \(\langle {d}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{d}_{\downarrow }\rangle\) decreases to 0.09 and \(\langle {p}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{p}_{\downarrow }\rangle\) increases to 0.96, indicating a well-quantized \(\left\vert {d}^{9}{p}^{6}\right\rangle\) structure in agreement with the well-established “charge transfer insulator”50,51 characteristic of this material.

Note that since the dressed particles emerge at the scale of the dominant interaction U, as in the first example they generically constitute all the lower-energy states. Essentially, the lower-energy physics (such as long-range orders) simply form larger emergent objects using the emergent objects of higher energy as building blocks. Therefore, the above ‘interaction annealing’ procedure is immune to further emergence occurring at lower energy and insensitive to differences among the low-energy states. Indeed, while having slightly higher energy, a ferromagnetic ground state can be stabilized under the realistic U and yet slowly annealing U to 20 eV gives very similar results and an identical \(\left\vert {d}^{9}{p}^{6}\right\rangle\) quantized structure.

5d semi-metallic WTe2

For the above representative case of La2CuO4, an experienced researcher might be able to guess the obtained \(\left\vert {d}^{9}{p}^{6}\right\rangle\) quantized structure without applying the proposed procedure, owing to the simplicity of the charge quantization in the remaining low-energy subspace. Realistic functional materials, however, often contain much richer degrees of freedom to simply relying on experience-based guessing.

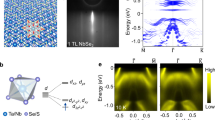

As a representative example, consider the semi-metallic material WTe252,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 with lattice structure shown in Fig. 2. Table 1 gives the local one-body density matrix \({\rho }_{nn^{\prime} }\equiv \langle {c}_{n}^{\dagger }{c}_{{n}^{{\prime} }}\rangle\) of orbital n for the DFT ground state under a reasonable value of U = 3 eV61,62 and the experimentally observed Td lattice structure52. Since the intra-atomic interaction is generally not overwhelmingly large in 5d compounds, the result shows enormous charge fluctuation that makes it impossible to identify a purely quantized valence and orbital structure desired for the physical understanding of low-energy dynamics (See Methods “Strong reduction of inter-atomic charge fluctuation” for quantification of inter-atomic charge fluctuation).

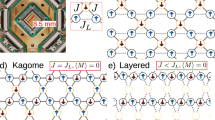

a Top view of the Td lattice structure of WTe2, represented via distortion (black arrows) of the higher symmetry 1T lattice structure, together with the local coordinate axis of W orbitals. b Color scheme for labeling the phase factor of orbitals. c Symmetry related (degenerate) \(e^{{\prime} }_{g}\) orbitals of W69, and their superposition, \(\left\vert e^{{\prime\prime} }_{g1}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert e^{{\prime} }_{g1}\right\rangle +\left\vert e^{{\prime} }_{g2}\right\rangle )\) and \(\left\vert e^{{\prime\prime} }_{g2}\right\rangle =\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\left\vert e^{{\prime} }_{g1}\right\rangle -\left\vert e^{{\prime} }_{g2}\right\rangle )\) emerged in orbital polarized states that spontaneously break the symmetry. d The stable local electronic structures found using LDA+U, including low-spin (LS), orbital-polarized (OP), and high-spin (HS) configurations of W ions.

Upon steadily suppressing the fluctuation via slowly “heating up” U to 20 eV, one finds a much cleaner \({\rho }_{nn^{\prime} }\) as in the lower half Table 1. In the \({e}_{g}^{{\prime\prime} }\) basis [c.f. Fig. 2c], \({\rho }_{nn^{\prime} }\) gives a well-quantized valence, orbital, and spin structure, corresponding to a dressed d2 orbital-polarized (OP2) structure shown in Fig. 2(d). One thus can reliably describe the electronic structure of the real material via an effective OP2 structure with dressed particles in the effective \({\tilde{e}}_{g}^{{\prime\prime} }\) orbitals (plus remaining fluctuation to \(\left\vert {d}^{3}\underline{L}\right\rangle\) associated with the metallicity).

Specifically, this energetically favored OP2 configuration contains double occupation of one of the symmetry-related dressed W \({\tilde{e}}_{g}^{{\prime\prime} }\) orbitals, as adiabatically connected to the one-body density matrix of a high-U configuration shown in the lower part of Table 1. In the absence of long-range order, there would be another symmetry-related configuration with double occupation in the other dressed \({\tilde{e}}_{g}^{{\prime\prime} }\) orbitals. Correspondingly, the low-energy dynamics must then contain that of an effective pseudo-spin-1/2 orbital fluctuation, or “orbiton”63.

Furthermore, our DFT ground contains a ferro-orbital ordering of the dressed \({\tilde{e}}_{g2}^{{\prime\prime} }\) orbitals of W. Such a ferro-orbital order of our identified OP2 structure offers a natural explanation for the experimentally observed octahedral deformation in Td lattice structure of this material below ~550K of temperature27 and 6 GPa of pressure28, since the lattice couples to the electronic charge and would follow the electronic ordering.

For consistency with experimental observations, it is easy to verify (See Methods for details) that the experimental observation of octahedral lattice distortion agrees much better with simple estimation using ionic radius of d2 W ion than that via d3 W ion29. Similarly, the spin-0 structure of OP2 agrees perfectly with the experimentally observed diamagnetic response in WTe230. These agreements with experiments confirm that the ferro-orbital ordered spin-0 picture obtained from our proposed ‘interaction annealing’ procedure indeed captures the dominant higher-energy short-range correlation of WTe2. Such physical understandings are clearly not possible from the heavily fluctuating density matrix of the bare particles at U = 3 eV.

Application to competing electronic structures

The proposed “interaction annealing” procedure is even more valuable for systems hosting competing local electronic structures that functionalizes modern materials. Specifically, one can identify the potential emergent ionic configurations of well-defined valence and orbital structures using an artificially large U. Furthermore, one can follow the adiabatic connection as U reduces to the physical strength and identify the stable emergent ionic structure for each surviving configuration in real materials.

To give an example, consider a fictitious system of WTe2 in an idealized 1T structure of higher symmetry shown in Fig. 2a without the distortion of the Td structure. As in many correlated materials, one finds multiple stable configurations, some of which may even appear extremely similar. For example, the right columns of Table 1 give \({\rho }_{n{n}^{{\prime} }}\) of two such stable configurations, containing charge fluctuation too strong to decipher the fully quantized emergent pictures even at a fictitious U = 8 eV (upper part of Table 1), let alone to distinguish their corresponding physical properties and low-energy dynamics.

In spite of their strong similarity, however, their adiabatically connected interaction-annealed counterparts at U = 20 eV (lower part of Table 1) display distinctive quantized local electronic structures. The former corresponds to an OP2 structure, while the latter contains fully occupied \({e}_{g}^{{\prime\prime} }\) orbitals, corresponding to the low-spin d4 (LS4) configuration of W ion in Fig. 2d. This LS4 configuration, while also diamagnetic, does not host the twofold local orbital freedom of the OP2 configuration. Therefore, it does not have low-energy “orbiton” dynamics, nor can it form a long-range orbital order. This great contrast in physics nicely illustrates the value of our proposed procedure, especially when the fluctuation in real materials is strong enough to mask the essential physical distinction between stable configurations.

In fact, in functional materials, one expects multiple competing stable electronic structures that are sensitive to slightly different external conditions, such as temperature, pressure, or external fields4,5,6,7. It is the qualitative distinct physical properties of these switchable stable configurations that grant the rich functionality of these materials. Below, we proceed with this example to demonstrate that the ‘interaction annealing’ procedure is not only valuable in deciphering the robust dressed objects, but also useful in identifying potential competing ones.

Exploring more thoroughly the interaction annealed (U = 20 eV) case, one finds even more stable structures (fixed points), as shown in Fig. 2d, all with distinct well-defined ionic valence, orbital, and spin structures. In addition to the OP2 and LS4 configuration, these also include a low-spin d2 (LS2), a high-spin d3 (HS3), and a orbital polarized d3 (OP3) configurations. One can also stabilize different spatial ordering of these ionic structures, such as ferro-orbital order (FO), antiferro-orbital order (AFO), ferromagnetic order (FM), and antiferromagnetic order (AFM). This demonstrates that, indeed, interaction annealing is an efficient way to identify stable emergent electronic structures that compete to dictate the physical properties under various external conditions.

One can even use the interaction annealed systems to observe the competition between these stable structures, under a given external condition (the fixed lattice structure in this demonstration). As shown in Fig. 3a, these different stable structures naturally split into groups of distinct energy. As the value of U slowly “cools down”, their physical quantities, such as total energy, smoothly evolve. Eventually, some of them become unstable and fall to other more stable ones, as indicated by the abrupt change in the total energy (and more in the density matrices), as emphasized in the inset of Fig. 3a. As illustrated in Fig. 3b, such destabilization is associated with the vanishing of the corresponding fixed points manifesting as local energy minima in the phase space. In functional materials, modulation of external conditions can alter the surviving local structures through varying the energy contour, thus enabling qualitative change of physical properties.

Illustration of competing structures under the symmetric 1T structure of WTe2, through a smooth evolution of a total energy (for 4 chemical formula units) upon reduction of U and b local minimum in the energy contour against density matrices. The inset highlights the destabilization of some of the structures, corresponding to the vanishing of local energy minimum in (b). Due to the large energy scale of intra-atomic physics, configurations of distinct local structures separate into four groups, OP2+LS2 (red), HS3 (green), OP3 (blue), and LS4 (yellow) [c.f. Fig. 2d], but less sensitive to long-range ferro-orbital (FO), anti-ferro-orbital (AFO), ferromagnetic (FM), and antiferromagetic (AFM) long-range orders.

In this idealized structure with higher symmetry, all other configuration fall to the OP2 ones before U is cooled to 5 eV (See Methods for details). That is, for real material the Rydberg-scale electronic correlation already develops a strong tendency toward local orbital polarization (and long-range ferro-orbital order at a lower energy scale). The experimentally observed Td structure should, therefore, be considered driven by such electronic correlation, followed by further energy gain via lattice relaxation.

Using currently available many-body treatments, the proposed approach aims to reveal the dominant dressed objects that describe the slow dynamics of the system. While this approach is not intended to improve these results (at least not by itself), as well demonstrated in the above examples, the obtained physical understanding is extremely valuable.

Discussion

In summary, based on existing many-body computation methods, we propose a generic ‘interaction annealing’ approach to decipher the local electronic structure that dominates the low-energy dynamics. We establish its robust theoretical foundation and its applications using an exact treatment of a two-site Hubbard model and DFT calculations of two representative materials, 3d Mott insulator cuprate La2CuO4 and 5d semi-metal WTe2. For the most fluctuating case of WTe2, the obtained emergent local electronic structure makes possible an unprecedented explanation of several experimental observations52,53,54,55,57,58,59,60. Finally, we demonstrate its effectiveness in studying competing local electronic structures in functional materials. This approach is straightforward to implement in standard many-body computations for correlated materials.

Methods

Obtaining low-energy effective Hamiltonian via numerical canonical transformation

Low-energy effective theory is one of the most effective means to capture and understand the key physics of a quantum system within a well-defined energy scale. Conceptually, it can be rigorously constructed by integrating out the high-energy states in the path integral formulation. Equivalently, it can also be derived by decoupling the remaining low-energy states from the high ones. Specifically, one finds a unitary transformation39,40, \({\mathcal{U}}[\{{c}_{i},{c}_{i}^{\dagger }\}]\), of the second quantized basis, ci, spanning the one-body space indexed by i,

such that the Hamiltonian has a “block diagonal” form, \(\tilde{H}\), in the new “many-body dressed” representation, \(\tilde{{c}_{i}}\) (freeing the low-energy subspace from the influence of the high-energy subspace),

Given

the unitary transformation \({\mathcal{U}}\) can thus be found by demanding

to possess the desired block diagonal form.

As a simple illustration for such an emergent structure, consider a two-site Hubbard model in Eq. (1), containing two electrons. Let’s first examine the emergent low-energy effective theories of this system in its correlated (t ≪ U) regime. In this regime, states with doubly occupied orbitals are the high-energy ones, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 4. By defining the unitary transformation \({\mathcal{U}}=\exp (\frac{\theta }{2}{\sum }_{\mu }\frac{1}{2}({c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{2\mu }-{c}_{2\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{1\mu })({n}_{2\bar{\mu }}-{n}_{1\bar{\mu }}))\) with \(\theta =\arctan (\frac{4t}{U})\), the resulting effective Hamiltonian,

cleanly separates the dynamics of the low-energy sector in the first line and high-energy one in the second. The former no longer contains charge dynamics but only an emergent effective inter-site anti-ferromagnetic super-exchange of strength \({\tilde{J}}_{12}=\frac{1}{2}(\sqrt{{U}^{2}+{(4t)}^{2}}-U)\), while the latter contains only effective inter-site charge dynamics of strength \(\frac{{\tilde{J}}_{12}}{2}\) for the “doublon”, \({\tilde{c}}_{i\uparrow }^{\dagger }{\tilde{c}}_{i\downarrow }^{\dagger }\), two electrons tightly bound into a hard-core boson. Here, \({\tilde{{\bf{S}}}}_{i}={\sum }_{\mu \nu }{\tilde{c}}_{i\mu }^{\dagger }{{\mathbf{\sigma }}}_{\mu \nu }{\tilde{c}}_{i\nu }\) denotes the effective spin with Pauli matrices σμν, \({\tilde{n}}_{i}={\tilde{c}}_{i\uparrow }^{\dagger }{\tilde{c}}_{i\uparrow }+{\tilde{c}}_{i\downarrow }^{\dagger }{\tilde{c}}_{i\downarrow }\) the net dressed particle number at site i, and \(\tilde{U}=U+\frac{{\tilde{J}}_{12}}{2}\) the effective intra-site repulsion, or the effective potential energy of the doublon. For clarity, Fig. 4 gives the matrix presentation of the Hamiltonian in product states of the original \({c}_{i}^{\dagger }\) basis (left panel) and the dressed particles \({\tilde{c}}_{i}^{\dagger }\) (right panel).

One sees that the low-energy dynamics can always be exactly described by an effective theory containing only quantized charge, orbital, and spin degrees of freedom, as the effective spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) shown here.

The other (weakly correlated) stable fixed point

Concerning the highest-energy scale of the two-site Hubbard model, the other (weakly correlated) fixed point emerges for t ≫ U. In this regime, the (high-energy) rapid dynamics is now the inter-site kinetic process instead. One thus first performs a canonical transformation via \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{1}\equiv \exp \left(\frac{\pi }{4}\,{\sum }_{\mu }\frac{1}{2}({c}_{2\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{1\mu }-{c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }{c}_{2\mu })\right)\), to decouple the energy of the bonding (\({b}_{\mu }^{\dagger }\)) and anti-bonding (\({a}_{\mu }^{\dagger }\)) orbitals at the one-body level,

where \({b}_{\mu }^{\dagger }\equiv {{\mathcal{V}}}_{1}^{\dagger }{c}_{2\mu }^{\dagger }{{\mathcal{V}}}_{1}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }+{c}_{2\mu }^{\dagger })\), and \({a}_{\mu }^{\dagger }\equiv {{\mathcal{V}}}_{1}^{\dagger }{c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }{{\mathcal{V}}}_{1}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}({c}_{1\mu }^{\dagger }-{c}_{2\mu }^{\dagger })\) are the bonding and anti-bonding orbitals, respectively.

For an easier visualization, the left panel of Fig. 5 represents H in the corresponding many-body basis. One sees that states with the bonding and anti-bonding orbitals both singly occupied are perfectly decoupled from those with fully occupied bonding or anti-bonding orbitals. However, the lowest-energy state with doubly occupied bonding orbitals and the highest-energy state with doubly occupied anti-bonding orbital are still coupled in the two-body level through the last term in Eq. (9).

Same as Fig. 4 but for the uncorrelated (t ≫ U) regime, where the emergent objects resides in the effective bonding \({\tilde{b}}_{\mu }^{\dagger }\) and anti-bonding \({\tilde{a}}_{\mu }^{\dagger }\) orbitals.

We then perform another transformation via \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{2}\equiv \exp (\frac{\phi }{2}({a}_{\uparrow }^{\dagger }{a}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{b}_{\downarrow }{b}_{\uparrow }-{b}_{\uparrow }^{\dagger }{b}_{\downarrow }^{\dagger }{a}_{\downarrow }{a}_{\uparrow }))\) with \(\phi =\arctan (U/4t)\), to further decouple them,

such that the slower dynamics is now cleanly separated into the lower (first line), middle (second line) and higher (third line) energy sectors, where \({\tilde{\epsilon }}_{b}=-\frac{1}{4}(\sqrt{{(4t)}^{2}+{U}^{2}}-U)\) and \({\tilde{\epsilon }}_{a}=\frac{1}{4}(\sqrt{{(4t)}^{2}+{U}^{2}}+U)\) denotes the emergent doublon potential energy for the effective bonding and anti-boding orbitals. The only remaining slow dynamics is now the emergent ferromagnetic inter-orbital Hund’s coupling of strength \({\tilde{J}}_{ba}=U\) between the effective orbitals. See Fig. 5 for the matrix representation of this canonical transformation.

As advocated in this manuscript, such an exact emergent description for the slower dynamics is always possible upon absorbing the rapid dynamics into the internal structure of the emergent objects, such as the effective bonding and anti-bonding orbitals,

for this example. Again, these emergent objects contain fully quantized effective charge, orbital, and spin degrees of freedom.

Notice that such energy separation and the residual dynamics is again adiabatically connected to the t ≫ U fixed point. Indeed, boosting up the dominant kinetic process, or more conveniently reducing \(\frac{U}{t}\) toward 0+, one finds that the main structures of Eqs. (10) and (11) remain qualitatively intact, with only quantitative change in the renormalized coefficients. Therefore, the emergent objects share the characteristics of those with negligible intra-atomic interaction. One can thus apply the “interaction annealing” procedure, but toward smallerU, to access the characteristics of emergent objects belong to this weakly correlated fixed point. This nicely explains the great success in application of LDA Wannier orbitals within the DFT framework: their qualitative characteristics represent those of the emergent objects in weakly correlated systems, even those with weak intra-atomic interactions.

Computational details of density functional calculation

Our first-principles calculations were performed using DFT-based14,15Wien2k package64 with the spin-polarized LDA+U47,65 and the linearized augmented plane wave (LAPW)66 implementation67. Monkhorst–Pack k-point grids for Brillouin zone sampling are set to 8 × 15 × 3 for bulk WTe2 with both 1T and Td structures. WTe2 crystallizes in an orthorhombic Bravais lattice, with a Td structure and space group Pmn21 (No. 31). We used the experimental lattice constants reported by Brown et al.68, a = 6.28Å, b = 3.50Å, c = 14.07Å, which were also confirmed by other experiments52. As the higher-symmetry 1T structure has not been observed in experiments, we built the structure with the same interlayer thickness as the experimental Td structure and optimized the intralayer lattice parameters through atomic relaxation. The lattice constants used for calculations in this work are a = 6.06Å, b = 3.50Å, c = 14.07Å, with the same space group Pmn21 (No. 31).

In the interaction annealing process, we set the effective U on W d-orbitals within the range of 3−20 eV. The “heat up” and “cool down” processes correspond to smoothly increasing and decreasing the interaction strength U in 0.2 eV and 0.1 eV per step with a mix factor of 0.05.

One-body density matrix \({\rho }_{n{n}^{{\prime} }}\) among the local W t 2g orbitals

At the high-U (~20 eV) regime, one finds many stable structures in the LDA+U calculations, all with distinct well-defined ionic valence, orbital, and spin structures. In order to reveal the potential spontaneous symmetry breaking of the system, the idealized 1T structure of higher symmetry with doubled W in one unit cell is thus built. Table 2 lists the one-body density matrix \({\rho }_{n{n}^{{\prime} }}\) among the local t2g orbitals of two W atoms with index n for different U ~ 20 eV configurations in 1T structure.

Illustration of competing configurations

Figure 6 shows the detail information of competing structures under the symmetric 1T structure of WTe2 and its adiabatic connection upon “decreasing” the interaction strength U. Through a smooth evolution of total energy (for 4 chemical formula units) upon reduction of U from the large limit ~20 eV to the realistic value ~3 eV, the total energy evolves smoothly until some configurations become unstable and fall to other more stable ones, as indicated by the abrupt ‘jump’ in the total energy curves. All other configurations fall to the OP2 ones before U is cooled to 5 eV.

Stable configuration via electron-lattice coupling in T d structure

With the help of lattice distortion towards lower symmetry, which is consistent with the symmetry-broken electronic state, this electronic configuration would be further stabilized. Figure 7 shows the stable configuration of WTe2 and its adiabatic connection upon “heating up” the interaction strength U. As U slowly increases from the realistic value 3 eV to large limit 20 eV, the configuration is OP2 with ferro orbital order, corresponding to the two electrons both occupying one of the two degenerate orbitals eg″2 with long-range ferro-orbital order.

Strong reduction of inter-atomic charge fluctuation

The strong charge fluctuation (and its suppression by intra-atomic repulsion U) is reflected in difficulty in deciphering the dominant characteristics of the emergent quantized objects. Microscopically, such charge fluctuation is more directly reflected in the inter-atomic one-body density matrix ρ. To quantitatively demonstrate the effect of charge fluctuations and their suppression at larger U, Table 3 gives a few representative elements of ρpd between Te p-orbitals and W d-orbitals, which are computed via symmetry respecting atomic Wannier orbitals16.

Consider for example the first row. At realistic U ~ 3 eV, \(\frac{{\rho }_{pd}}{{\rho }_{pp}-{\rho }_{dd}} \sim 1.33 >\) 1, indicating a strong inter-atomic charge fluctuation between these two orbitals. In contrast, under the increased U ~ 20 eV, \(\frac{{\rho }_{pd}}{{\rho }_{pp}-{\rho }_{dd}} \sim 0.29\ll\) 1, reflecting a dramatic suppression of the inter-atomic charge fluctuation, which makes it much easier to decipher the low-energy emergent objects.

Estimated octahedral distortion from ionic radius29 for d 2 and d 3 configurations in WTe2 with T d structure

Table 4 gives the calculated average deviations of both W-Te bond length, \(\Delta =\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{6}\left\vert {d}_{i}-{d}_{{\rm{mean}}}\right\vert\), and the Te-W-Te intersection angle ϕi, \(\Sigma =\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{12}\left\vert 9{0}^{\circ }-{\phi }_{i}\right\vert\), of the local WTe6 octahedron. Evidently, compared with \({{\rm{W}}}^{3+}{{\rm{Te}}}_{2}^{1.5-}\) (d3), \({{\rm{W}}}^{4+}{{\rm{Te}}}_{2}^{2-}\) (d2) gives a superior agreement with the experimental structure. In fact, the negligible Δ for \({{\rm{W}}}^{3+}{{\rm{Te}}}_{2}^{1.5-}\) indicates that W3+ ion is too large to be compatible with the Td structure.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Cahn, R. W. Functional Materials, Vol. 5 (Pergamon, Amsterdam, 2001).

Sahu, D. Functional Materials (IntechOpen, London, 2019).

Dagotto, E. Complexity in strongly correlated electronic systems. Science 309, 257–262 (2005).

Kawai, M., Nabeshima, F. & Maeda, A. Transport properties of FeSe epitaxial thin films under in-plane strain. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1054, 012023 (2018).

Kushnirenko, Y. S. et al. Anomalous temperature evolution of the electronic structure of FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 96, 100504(R) (2017).

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493–498 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Anderson, P. W. More is different: Broken symmetry and the nature of the hierarchical structure of science. Science 177, 393–396 (1972).

Taillefer, L. Scattering and pairing in cuprate superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 1, 51–70 (2010).

Dagotto, E. Correlated electrons in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 763–840 (1994).

Schrieffer, J. R. & Wolff, P. A. Relation between the Anderson and Kondo Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. 149, 491–492 (1966).

Zaanen, J. & Oleś, A. M. Canonical perturbation theory and the two-band model for high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 37, 9423–9438 (1988).

Jiang, R., Hou, J., Fan, Z., Lang, Z.-J. & Ku, W. Pressure driven fractionalization of ionic spins results in cupratelike high-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 126503 (2024).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Ku, W., Rosner, H., Pickett, W. E. & Scalettar, R. T. Insulating ferromagnetism in La4Ba2Cu2O10: An ab initio wannier function analysis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 167204 (2002).

Kanungo, S., Yan, B., Jansen, M. & Felser, C. Ab initio study of low-temperature magnetic properties of double perovskite Sr2FeOsO6. Phys. Rev. B 89, 214414 (2014).

Bellaiche, L. & Vanderbilt, D. Electrostatic model of atomic ordering in complex perovskite alloys. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 1318–1321 (1998).

Wu, Z. & Krakauer, H. Charge transfer model of atomic ordering in complex perovskite alloys. AIP Conf. Proc. 535, 121–128 (2000).

Stevanović, V., d’Avezac, M. & Zunger, A. Simple point-ion electrostatic model explains the cation distribution in spinel oxides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 075501 (2010).

Stevanović, V., d’Avezac, M. & Zunger, A. Universal electrostatic origin of cation ordering in A2BO4 spinel oxides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11649–11654 (2011).

Jiang, R., Li, X., Zhang, X. & Ku, W. In preparation.

Larson, B. C. et al. Nonresonant inelastic x-ray scattering and energy-resolved Wannier function investigation of d–d excitations in NiO and CoO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 026401 (2007).

Walters, A. et al. Effect of covalent bonding on magnetism and the missing neutron intensity in copper oxide compounds. Nat. Phys. 5, 867–872 (2009).

Abbamonte, P. et al. Dynamical reconstruction of the exciton in LiF with inelastic x-ray scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 12159–12163 (2008).

Nelson, R., Berlijn, T., Moreno, J., Jarrell, M. & Ku, W. What is the valence of Mn in Ga1−xMnxN? Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 197203 (2015).

Tao, Y., Schneeloch, J. A., Aczel, A. A. & Louca, D. Td to \(1{T}^{{\prime} }\) structural phase transition in the WTe2 weyl semimetal. Phys. Rev. B 102, 060103 (2020).

Zhou, Y. et al. Pressure-induced Td to 1T' structural phase transition in WTe2. AIP Adv. 6, 075008 (2016).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. A 32, 751–767 (1976).

Yang, L. et al. Highly tunable near-room temperature ferromagnetism in Cr-doped layered Td-WTe2. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008116 (2021).

Sakurai, J. J. Modern Quantum Mechanics; rev. edn (Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1994).

Kato, T. On the adiabatic theorem of quantum mechanics. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 5, 435–439 (1950).

Eshuis, H., Bates, J. & Furche, F. Electron correlation methods based on the random phase approximation. Theor. Chem. Acc. 131, 1–18 (2012).

Pernal, K. Electron correlation from the adiabatic connection for multireference wave functions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 013001 (2018).

Granas, A. & Dugundji, J. Fixed Point Theory (Springer, New York, 2003).

Goldenfeld, N. Lectures on Phase Transitions and The Renormalization Group, (CRC Press, 1992).

Hubbard, J. Electron correlations in narrow energy bands. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 276, 238–257 (1963).

Arovas, D. P., Berg, E., Kivelson, S. A. & Raghu, S. The Hubbard model. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 13, 239–274 (2022).

Chao, K., Spalek, J. & Oles, A. Kinetic exchange interaction in a narrow s-band. J. Phys. C Solid State Phys. 10, L271 (1977).

White, S. Numerical canonical transformation approach to quantum many-body problems. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 7472–7482 (2002).

Feist, J. contributors. Quantumalgebra.jl https://github.com/jfeist/QuantumAlgebra.jl (2021).

Sánchez-Barquilla, M., Silva, R. E. F. & Feist, J. Cumulant expansion for the treatment of light-matter interactions in arbitrary material structures. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 034108 (2020).

Jiang, R., Fan, Z., Monserrat, B. & Ku, W. Pressure-induced trans-proximate correlation in La4Ni3O10 and possible routes to enhance its superconductivity. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.13442 (2025).

Yokoyama, H. & Shiba, H. Variational Monte-Carlo studies of Hubbard model. i. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 56, 1490–1506 (1987).

Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 259–315 (2005).

Evenbly, G. & Vidal, G. Tensor network states and geometry. J. Stat. Phys. 145, 891–918 (2011).

Anisimov, V. I., Solovyev, I. V., Korotin, M. A., Czyżyk, M. T. & Sawatzky, G. A. Density-functional theory and NiO photoemission spectra. Phys. Rev. B 48, 16929–16934 (1993).

Anisimov, V. I., Aryasetiawan, F. & Lichtenstein, A. I. First-principles calculations of the electronic structure and spectra of strongly correlated systems: the LDA + U method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 9, 767–808 (1997).

Anisimov, V. I. et al. Computation of stripes in cuprates within the LDA + U method. Phys. Rev. B 70, 172501 (2004).

Zaanen, J., Sawatzky, G. A. & Allen, J. W. Band gaps and electronic structure of transition-metal compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 418–421 (1985).

Moskvin, A. S. True charge-transfer gap in parent insulating cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075116 (2011).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Tungsten ditelluride: a layered semimetal. Sci. Rep. 5, 10013 (2015).

Das, P. K. et al. Electronic properties of candidate type-II Weyl semimetal WTe2. a review perspective. Electron. Struct. 1, 014003 (2019).

Fei, Z. et al. Ferroelectric switching of a two-dimensional metal. Nature 560, 336–339 (2018).

Sharma, P. et al. A room-temperature ferroelectric semimetal. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax5080 (2019).

Gu, F., Jiang, R. & Ku, W. 2D ferroelectricity accompanying antiferro-orbital order in semi-metallic WTe2. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.18438 (2025).

Ali, M. et al. Large, non-saturating magnetoresistance in WTe2. Nature 514, 205–208 (2014).

Soluyanov, A. A. et al. Type-II Weyl semimetals. Nature 527, 495–498 (2015).

Ma, Q. et al. Observation of the nonlinear Hall effect under time-reversal-symmetric conditions. Nature 565, 337–342 (2019).

Wang, H. & Qian, X. Ferroelectric nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in few-layer WTe2. npj Comput. Mater. 5, 119 (2019).

Kirchner-Hall, N. E., Zhao, W., Xiong, Y., Timrov, I. & Dabo, I. Extensive benchmarking of DFT + U calculations for predicting band gaps. Appl. Sci. 11, 2395 (2021).

Linnartz, J. F. et al. Fermi surface and nested magnetic breakdown in WTe2. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, L012005 (2022).

Allen, P. B. & Perebeinos, V. First glimpse of the orbiton. Nature 410, 155–158 (2001).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k: an APW+lo program for calculating the properties of solids. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 074101 (2020).

Liechtenstein, A. I., Anisimov, V. I. & Zaanen, J. Density-functional theory and strong interactions: orbital ordering in Mott-Hubbard insulators. Phys. Rev. B 52, R5467–R5470 (1995).

Singh, D. J. & Nordström, L. Planewaves, Pseudopotentials and the LAPW Method (Springer, New York, 2006).

Blaha, P., Schwarz, K., Sorantin, P. & Trickey, S. Full-potential, linearized augmented plane wave programs for crystalline systems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 59, 399–415 (1990).

Brown, B. E. The crystal structures of WTe2 and high-temperature MoTe2. Acta Crystallogr. 20, 268–274 (1966).

Qian, Z. & Khaldoon, G. Spherical Harmonics (WebGL, OpenGL, 2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grants No. 12274287 and No. 12042507 and the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology No. 2021ZD0301900. R.J. acknowledges additional support by UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship [MR/V023926/1].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.J. conducted the exact many-body treatment of the two-site Hubbard model. R.J. and F.G. carried out and analyzed the DFT calculations. W.K. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the project, methodology design, discussion of the results, and the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, R., Gu, F. & Ku, W. ‘Interaction annealing’ to determine effective quantized valence and orbital structure: an illustration with ferro-orbital order in WTe2. npj Comput Mater 12, 39 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01904-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-025-01904-y