Abstract

Flexible wearable sensors are crucial for health monitoring and motion detection, but they are often hindered by inadequate breathability and comfort. Here, we present a breathable pressure sensor that combines MXene nanosheets with a porous polyester textile, achieving high sensitivity (652.1 kPa⁻¹), a broad detection range (0–60 kPa), and a fast response/recovery time (36 ms/20 ms). The serpentine electrode pattern enhances tensile strength and sensitivity, while electrospun TPU nanofiber membranes improve breathability and signal recovery. A 4 × 4 electrode array allows for precise pulse localization, while machine learning algorithms enable real-time blood pressure prediction. This innovative design demonstrates significant potential for wearable health monitoring and cardiovascular diagnostics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flexible sensors have emerged as a key technology in wearable device development due to their lightweight, bendable, and stretchable characteristics, enabling them to effectively conform to the complex surfaces of the human body1,2,3. These sensors not only adhere comfortably to the skin, maximizing wearer comfort, but they also demonstrate high detection robustness, allowing for user freedom of movement4,5,6,7. This makes the flexible wearable sensor unparalleled in applications for continuous health monitoring, particularly for tracking physiological signals such as heart rate and pulse8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Compared to traditional rigid sensors, wearable flexible sensors address the challenges of large instrument sizes and uncomfortable wear. They easily adapt to various wearing scenarios and individual daily healthcare needs15,16, particularly in personalized health management solutions and medical institutions in a precise and real-time manner17,18.

Pressure sensors are crucial for health monitoring as they can accurately detect changes in the body19,20,21,22, monitor physiological signals such as breathing, pulse, joint movement23, and muscle contraction, and provide real-time data to help identify abnormalities or health issues24,25,26. Wearable pressure sensors allow continuous, real-time tracking, offering advantages over traditional, bulky equipment. The detection range must cover pressures from small to large movements, while the sensitivity needs to detect subtle pressure changes during dynamic activities. So, effective pressure monitoring requires sensors with a wide detection range and high sensitivity. Microstructural designs, such as porous layers, micropatterned structures, and multi-layered encapsulation, are commonly used to enhance sensitivity. For example, micro-patterns inspired by crocodile skin structures can significantly enhance sensitivity (3.60 kPa⁻¹)27. Some multi-layer sensors, such as MXene/Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) films28 demonstrate high performance, achieving sensitivities of up to 151.4 kPa⁻¹ and sensing ranges of 15 kPa. However, pressure sensors face limitations due to their rigidity and non-conformable characteristics, restricting their capability to monitor skin deformation and soft areas, thereby limiting their application in high-sensitivity dynamic monitoring. Polymers, such as Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and PDMS29,30, are commonly used substrates in traditional flexible wearable pressure sensors. However, their poor breathability limits the sensors’ comfort and fit, potentially leading to skin discomfort and inflammation during wear. To overcome these challenges, paper and textile materials have been explored as substrates; the sensitivity of the flexible pressure sensor is closely related to the substrate’s modulus of elasticity. Materials with a lower modulus undergo greater deformation under pressure, leading to larger resistance variations and enhanced sensitivity. Based on this point, the sensitivity of these sensors remains relatively low (1.5–298.4 kPa⁻¹)31,32, primarily because the modulus of elasticity of the material is too high. Consequently, the limited deformation under pressure leads to minimal resistance changes, reducing the sensor’s sensitivity. However, achieving high sensitivity and a broad sensing range for detecting pulses and dynamic motion remains a challenge, as the materials used must be able to deform significantly under pressure while maintaining their structural integrity, which is challenging to accomplish without compromising either sensitivity or durability33.

In this work, we leveraged the unique advantages of a two-dimensional (2D) layered wearable pressure sensor and proposed a novel piezoresistive pressure sensing system capable of monitoring joint movement and predicting blood pressure, aiming to play a key role in human health monitoring applications. The sensor combined the excellent electrical conductivity of MXene nanosheets with the distinctive structure of polyester textile and featured a specially designed serpentine electrode pattern that ensured stable performance under complex deformations. It enabled accurate detection of joint motion and grip distribution, as well as high-precision data acquisition in dynamic environments. Experimental results demonstrated the sensor’s outstanding performance, including high sensitivity (652.1 kPa⁻¹), a wide sensing range (60 kPa), and fast response and recovery times (36 ms and 20 ms, respectively). Moreover, the sensor accurately captured arterial pulse waveforms. To enhance its practical application, we further developed a high-speed data acquisition and real-time recognition system, complemented by machine learning algorithms, enabling precise pulse and blood pressure monitoring across large populations and diverse environments. This innovation not only provided valuable data for early diagnosis of cardiovascular diseases but also highlighted the significant potential of wearable smart devices in portable diagnostics and health management.

Results

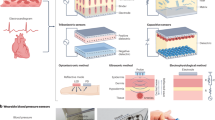

Production of MXene-Based Pressure Sensor

Polyester fiber dust-free cloth was selected as the core material and was integrated into a Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) substrate after the MXenelization to develop a fully textile-based flexible pressure sensor. The sensor obtained good breathability and suitable tensile properties through the materials, making it ideal for wearable applications (Fig. 1a). To obtain Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene nanosheets, the MXene was produced by selectively etching the aluminum (Al) layer from the MAX phase. This process produces MXene nanosheets with surface oxygen-containing groups (e.g., -OH, -F, and =O), enhancing their compatibility with polymer substrates and yielding single-layer MXene nanosheets (Fig. 1b). The TPU substrate was prepared by electrospinning, and the stretchable silver ink was screen-printed onto the TPU fiber membrane (Fig. 1c) and then dried in an oven to complete flexible serpentine electrodes. The samples were then dried in an oven to prepare flexible serpentine electrodes, which serve as the electrode layer of the sensor. Next, the lint-free fabric was immersed in a pre-prepared MXene solution to impart the required conductivity to the sensing electrodes. The fabric was subsequently dried in an oven at 60 °C for 20 min to produce the MXene-modified conductive fabric (Fig. 1d). To verify the effect of the number of immersion cycles on conductivity, we conducted a comparative analysis across multiple immersion rounds. The results showed that after repeating the immersion and drying process twice, the conductivity stabilized (Fig. S1). Therefore, the immersion process was carried out twice to further enhance the conductivity of the sensing layer. Finally, the electrode layer was combined with the fabric sensing layer, completing the assembly of the MXene Fabric (MF) pressure sensor (Fig. 1e). The sensor is designed to measure pressure distribution on the palm, focusing on accurately locating the pulse signal using a 4 ×:4 electrode array (Fig. 1f). This concept of pressure distribution monitoring is integrated into the design of a flexible sensor that can accurately capture the subtle radial artery pulse waves on the human wrist for healthcare applications. The MF sensor utilizes a 4 × 4 electrode array to pinpoint the location of the strongest pulse signal, ensuring accurate detection. The flexible piezoelectric pressure sensor placed on the wrist responds sensitively to periodic arterial pulses, generating electrical signals that accurately reflect blood pressure (BP) waveforms (Fig. 1g). This setup forms the conceptual framework for predicting blood pressure, collecting pulse signals and extracting key feature values for model training. The trained model is then used to predict blood pressure, and the results are compared with measurements from a commercial sphygmomanometer to evaluate the accuracy of the blood pressure calculations based on the Wearable Predictive Blood Pressure System (WPBPS) model (Fig. 1h).

a The sensor is designed for breathability, flexibility, and comfort. b MXene nanosheets are prepared by etching MAX phases with LiF and HCl, followed by delamination. c Electrospinning TPU creates a fibrous membrane, and serpentine electrodes are screen-printed for conductivity. d The MXene sensing layer is made by depositing nanosheets onto a substrate. e The MF sensor is assembled by combining the electrode substrate with the MXene layer for pressure and strain detection. f The 4 × 4 sensor monitors palm pressure distribution. g The 4 × 4 array detects pulse waves on the wrist, generating BP waveforms. h BP prediction involves pulse signal collection, feature extraction, and accuracy validation with sphygmomanometer measurements.

The uniformity of the MXene on the fabric is crucial because it significantly influences properties such as conductivity, mechanical strength, and sensitivity32. Variations in uniformity can result in inconsistent sensor performance and unreliable measurements33. Therefore, conducting scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is essential to assess the uniformity of MXene distribution on the fabric. SEM images demonstrate that the nanosheets were uniformly distributed on the fibers of the cloth, forming a continuous two-dimensional layered structure (Fig. 2a–c). The chemical composition of the MXene nanosheets was further tested using energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The EDS spectrum and mapping indicated that titanium (Ti) and carbon (C) were uniformly distributed on the dust-free cloth surface. At the same time, the peaks of oxygen (O) and fluorine (F) originate from functional groups introduced on the MXene surface after HF etching (Fig. 2d). Additionally, the energy spectrum analysis demonstrated the distribution of elemental compositions at different energy levels, in which C exhibited a mighty peak in the low energy region (around 0.3 KeV), indicating a high concentration of carbon in the sample (Fig. 2e). O and F elements display peaks at slightly higher energies, typically between 0.5 and 1 KeV. Ti peaks in the energy region of approximately 4.5–5 KeV. To further analyze the surface chemical state of the MXene nanosheets, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted (Fig. S2). The XPS spectra, which marked the presence of C, O, Ti, and F were displayed. C showed a significant peak in the binding energy region (around 280 eV), indicating a high carbon content in the sample. O and F exhibit pronounced peaks at approximately 530 eV and 680 eV, respectively, indicating their presence in the sample. A Ti peak was observed at around 460 eV, which is consistent with the Ti signal commonly found in MXene materials (Fig. S3).

a SEM image showing the uniform distribution of MXene on the fabric surface (Scale: 20 μm). b Close-up of MXene flakes adhering to individual fibers, forming a continuous conductive layer (Scale: 10 μm). c MXene uniformly integrated on the fabric surface (Scale: 1 μm). d EDS mapping: Carbon (green) highlights MXene regions, Titanium (violet) confirms MXene presence, Oxygen (yellow) shows uniform distribution, and Fluorine (cyan) from the etching process. e EDX spectrum confirming the presence of C, O, F, and Ti on the fabric surface. f, g Electro-spun TPU structure forming a uniform nanometer-scale 3D porous network (Scale: 1 μm in f, 200 nm in g).

SEM was also used to observe the morphology of the TPU fiber membrane. The surface of the TPU fiber membrane illustrates a typical three-dimensional porosity network structure in the nanometer range (Fig. 2f, g). The elasticity and porosity of the TPU membrane provide high mechanical stability under external pressure and stretching, ensuring ample surface area for the adhesion of flexible electrode materials, which enhances detection sensitivity. The screen-printed serpentine silver layer is uniformly adhered to the TPU membrane, creating a robust conductive layer. The stretchability of the silver electrodes allowed the sensor to function under conditions of significant deformation. Experimental results demonstrated that the silver electrodes remain stably connected even when stretched to strains exceeding 50%, ensuring regular operation of the sensor under high-strain conditions (Fig. S4).

Pressure Sensing Performance

To evaluate the stress distribution and strain range of the MXene-based flexible pressure sensor under various pressure conditions, we conducted a static stress simulation using finite element analysis (FEA), beginning with the construction of a structural model of the dust-free fabric (Fig. 3a). The space between the MF electrodes decreases with increased pressure loading, resulting in tighter connections among the MXene nanosheets, further forming continuous conductive pathways (Fig. 3b). Within the pressure range of 0 to 15 kPa, the sensor’s strain distribution remained uniform, with the maximum strain reaching 85%. When this maximum was achieved, a noticeable local displacement occurred, with the color gradually shifting from blue to green and yellow, ultimately resulting in red areas appearing on the surface layer and at the contact points of the structure (Fig. 3c; movie S1). When different voltages were applied (0.2–1 V), the current-pressure (mA-Pa) curves exhibited a linear relationship, in which the current progressively increased with rising pressure (Fig. 3d). The growth was more pronounced when higher voltages (1 V and 0.2 V) were applied. Since the sensor material was a flexible, high-resistance conductor and the measurement system included current limiting, the current passing through the skin was maintained at the microampere level, well below the human sensory threshold. Therefore, a 1 V voltage was selected for sensing. We also examined how increasing the number of immersions affected the electrical signal at various pressures. The results further confirmed that the electrical signal plateaued after the third immersion, suggesting that conductivity had reached saturation. Further immersion cycles yielded no noticeable improvement (Fig. S5). Furthermore, we conducted comparative experiments to examine how different MXene solution concentrations (1 mg/mL, 3 mg/mL, 5 mg/mL, and 10 mg/mL) affect resistance changes under a constant pressure of 560 Pa. The findings revealed that the greatest resistance variation occurred at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. Excessive MXene loading caused the sensing layer to reach performance saturation, leading to a plateau in resistance change. Consequently, we chose the 5 mg/mL solution for fabricating the sensing layer (Fig. S6).

a Three-dimensional woven structure of the flexible fabric sensor for effective pressure sensing. b Structural changes in textile fibers before and after pressure application, showing fiber deformation and alignment. c FEA results showing stress distribution within the sensor under pressure, indicating material response. d Linear variation of current output with applied pressure, demonstrating consistent electrical response. e Dynamic response at different pressure levels, showing time-dependent electrical signal changes. f Pressure sensitivity curve highlighting the sensor’s wide operational range across low and high pressures. g Sensor sensitivity comparison with similar devices, showing superior performance in detecting subtle pressure changes. h Response and recovery times were evaluated, showing rapid pressure detection and baseline return. i Performance stability after multiple stretching cycles, demonstrating durability and consistent functionality. j LED activation upon pressure application, showing the sensor’s response to pressing forces. k Increased LED brightness with stretching, indicating the sensor’s ability to detect tensile deformation. l Long-term stability tests confirming the sensor’s robustness and reliability for extended use.

According to the FEA, a 1 V voltage was applied to the MF pressure sensor to perform the pressure response test under a large pressure range (0–702 Pa, Fig. 3e), and the current response increased significantly as the applied pressure increased. We observed that within the pressure range of 250–300 Pa, the slope of the resistance response increases significantly compared to other regions. This is because, at around 250 Pa, the compression between fibers rapidly intensifies, causing some previously non-contact areas to close gradually. As a result, the number of conductive paths increases significantly, leading to a faster rate of resistance change and a sharp rise in the slope. Within the range of 1 to 5 kPa, the relative current change exhibits a monotonic upward trend (Fig. S7). After the pressure reaches 5 kPa, the current trend gradually flattens out. Notably, the MF pressure sensor stably generated a corresponding current response under a minimal pressure of 1 Pa, with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) sufficient to distinguish the signal from baseline fluctuations. Baseline noise analysis under no applied pressure showed a noise level of approximately 1.72 ± 0.27 μA, which is significantly lower than the response amplitude under 1 Pa pressure, thereby confirming the sensor’s reliable ultra-low pressure detection capability (Fig. S8). The sensitivity of the MF sensor varied with pressure and could be categorized into three distinct operating stages. In Fig. 3f, the low-pressure range (S1, 0–2.5 kPa) demonstrated an extremely high sensitivity of 652.1 kPa⁻¹. As pressure increased further (S2, 2.5–7.5 kPa), the sensitivity decreased and became linear at 130.8 kPa⁻¹. In the high-pressure stage S3 (7.5–60 kPa), the sensitivity decreased to a lower value of 15.3 kPa⁻¹ (Fig. S1). Compared to previously reported pressure sensors, the MF pressure sensor exhibits superior pressure-sensing performance in sensitivity (652 kPa⁻¹ at 0-2.5 kPa) (Fig. 3g; Table S1). For example, 53.5 times of the pressure sensor based on carbon nanotube/cotton fabric (14.4 kPa⁻¹ at 0–3.5 kPa in linear)34, 7.7 times of MXene/Au/PET film (99.5 kPa⁻¹ at 0–1 kPa in linear)35, 158.3% higher than MXene/silk fibroin nanofiber film (298.4 kPa⁻¹ at 1.4–15.7 kPa in linear)32, and 51.3% higher than MXene/tissue paper (509.5 kPa⁻¹ at 0.5–10 kPa in linear)36. We set the upper limit of the sensing range to 60 kPa, primarily considering that this study is focused on real-world human skin pressure monitoring scenarios, where the maximum pressure generated on the skin’s surface during dynamic movement is typically below 60 kPa.

The sensor exhibited a response time of 36 ms and a recovery time of 20 ms (Fig. 3h), showing the ability to rapidly respond to pressure changes and quickly return to the initial state after pressure (537 Pa) is released. Subsequently, we observed that when the sensing layer underwent 8000 stretching cycles with a strain exceeding 85%, the resistance change remained within 3% (Fig. 3i). Additionally, we conducted 8000 stretching tests to monitor the variation in the electrical signal. The results showed that the sensor’s response current did not exhibit significant attenuation during the tests (Fig. S9), indicating its excellent electrical stability even under significant deformation. Furthermore, to evaluate the influence of human motion and sweat on sensing performance, artificial sweat was applied during the 8000 stretching cycles while monitoring the resistance. The results showed that the artificial sweat had minimal impact on resistance, and by the third application, its effect was negligible (Fig. S10). Additionally, the sensor underwent 8000 twisting cycles, during which it also maintained stable electrical performance (Fig. S11). Additionally, the sensor was used as a conductor to power an LED light with a 3 V voltage. The LED brightness was adjusted by pressing (6.5 kPa) and stretching the dust-free cloth, demonstrating that the MXene pattern possesses excellent conductivity and performs pressure-responsive properties (Fig. 3j, k). An intermittent pressure of 7.23 kPa was applied to the MF sensor for 18000 s, with 1-s intervals, to test the long-term cyclic stability. The response current of the sensor exhibited no significant degradation over the test (Fig. 3l), indicating the exceptionally high stability of the bonding between MXene and the dust-free cloth substrate. After continuous wear on the human body for 7 days, the sensor retained 90.2% of its initial sensitivity, demonstrating excellent environmental stability (Fig. S12).

Application Demonstration

In Fig. 4a, the system gathers pressure and pulse signals through the sensor interface, generating an initial signal. This signal is processed in the signal processing unit shown in Fig. 4b, which includes a TIA, adder, filter, and amplifier to enhance and filter the signal. The microcontroller unit (MCU) shown in Fig. 4c converts the analog signal into a digital format through an ADC and enables communication through UARTs. The processed data is then wirelessly transmitted through the NFC module (Fig. 4d) to an application for predicting blood pressure. Figure 4e displays the PCB design for sensor data processing and wireless communication, incorporating a microcontroller, signal conditioning components, and an NFC module for data transfer. This paper presents a modular pressure measurement system with advanced signal processing techniques (Fig. 4f). The design of the circuit board includes both single-channel and multi-channel types, featuring flexible layout planning customized for various application needs and scenarios (Fig. S13). For flexible devices, breathability is crucial in achieving long-term wearing comfort37. The high porosity, resulting from the interlaced structure of nanofibers, allows gases and water vapor to permeate through the TPU nanofiber substrate. In practical applications, we utilize medical-grade polyurethane (PU) double-sided adhesive tape at the four corners of the sensor to ensure good contact with the skin for stable fixation. To assess the impact of this adhesive on breathability, we conducted comparative tests involving sensors without adhesive, sensors with medical-grade PU double-sided adhesive tape, and other reference materials. The breathability of each membrane was indirectly evaluated by placing the samples in sealed containers and measuring the rate of moisture loss over seven days (Fig. S14). The MF sensor (60.1 mm/s, thickness: 50 µm) exhibited significantly higher breathability than nylon (10.3 mm/s, thickness: 50 µm). It showed a minimal difference compared to the MF sensor with medical-grade PU double-sided adhesive tape (59.2 mm/s, thickness: 50 µm). In contrast, PDMS film (0.92 mm/s, thickness: 50 µm) and medical nonwoven adhesive tape (8.41 mm/s, thickness: 50 µm) demonstrated much lower breathability. These results suggest that the MF sensor is well-suited for long-term wear (Fig. S15). Furthermore, we carried out a one-week practical wear test on six volunteers, comparing their physical activity levels before and after using the device. The results indicated that the volunteers experienced no noticeable discomfort or foreign body sensation during daily activities, and there were no abnormal reactions such as redness or swelling on the skin surface and no significant sweating was observed after exercise (Fig. S16). To further evaluate the potential risks of the sensor layer material to the skin, we examined the effects of its extract on the vitality of human skin keratinocytes. The experimental findings showed that, at various concentrations, the sensor layer extract had no significant effect on the vitality and proliferation of keratinocytes (Fig. S17, 18). In conclusion, compared to other piezoelectric sensors, this study employs a microporous MXene sensing layer, which not only boosts sensitivity but also enhances breathability and comfort. The system’s adaptability and skin compatibility were demonstrated through wearing tests. Additionally, the feasibility and stability of the system for real-world use were confirmed via volunteer wearing tests, exercise assessments, and biocompatibility evaluations.

a Signal Generation Module. b Signal Processing System. c Microcontroller Unit (MCU). d Data Transmission and Prediction. e Design of Multi-channel and Single-channel Circuit Boards. f The circuit board is paired with a smartphone displaying real-time data labeled ‘MF sensor’ and the customer-made flexible printed circuit board (FPCB) records the signal. g Actual appearance of the MXene-based flexible sensor, with the electrode of 13.52 mm × 12.99 mm. h, i The sensor is attached to the knee and the elbow joints, testing current signal variations at different bending angles. j, k The sensor attached to the wrist tests signal variations at multiple bending angles. l By attaching the sensor to the finger and monitoring the change in the electrical signal generated when it presses the mouse. m Conceptual diagram of the sensor arranged on the palm, a 4 × 4 sensor array, and a pressure sensor on the fingertips to design for monitoring gripping actions. n, o, p Grip the cups in different sizes (n in small, o in medium, p in large); the data shows a curve. q, r, s Represent the 4 × 4 pressure distribution when gripping small, medium, and large cups, respectively, showcasing the sensor array’s precision in capturing pressure distribution patterns across different gripping conditions.

The sensors featuring electrodes measuring 13.52 mm × 12.99 mm were attached to a human surface to test the performance of the movement (Fig. 4g; Fig. S19). A custom-made FPCB was designed to collect, digitize and transfer the signals generated by the MF sensor during movement. The digitized signals were transferred to a smart device or PC in real-time. With the knees and elbows fully extended (bending angles were 0 degrees), the sensors are attached to the surfaces of these joints. The measurements were conducted under different bending angles, which means the movements could be accurately detected with our sensor. The pressure was in the range of 1–5 kPa on the knee movement and 0.5–3 kPa on the elbow movement, which are similar to previous reports38 (Fig. 4h, i). With the sensors on the finger and wrist, the sensor detected repeated bending, and the current density was highly repeated by bending at the same angle (Fig. 4j, k). The sharp peaks correspond to the application of pressure, demonstrating the pressure sensor’s sensitive response capability under dynamic conditions (Fig. 4l). The results demonstrated that the sensor has the potential to be used in robot and human motion monitoring. Meanwhile, a gentle breeze was applied to the pressure sensor to test its ability to detect and transmit signals successfully, thereby validating its performance and sensitivity (Fig. S20).

Robot motion monitoring has evolved from simple pressure detection to encompass more complex areas, including human-machine interaction and object grasp recognition. To achieve multipoint sensing of the complex mechanical distribution on the hand, this study employs a specialized electrode pattern (4 × 4 array) on the palm (Fig. S21). Specifically, a 4 × 4 electrode array was arranged in the palm area, with each electrode unit connected to an MXene sensing layer, forming independent pressure detection units. We validate the effectiveness of the sensor’s multipoint sensing capability by real-time monitoring of pressure variations at different positions on the palm while grasping cups of various sizes. Furthermore, by attaching the sensor to the fingertips, the local pressure exerted by the fingers on the object’s surface during grasping can be accurately detected. Each sensor unit is connected to the data acquisition system through independent electrodes, enabling real-time collection and processing of multipoint pressure signals (Fig. 4m). To evaluate the sensor system’s response to pressure distribution during various hand movements, a hand equipped with the sensor grasped cups of three sizes: large, medium, and small (Fig. 4n, o, p). When grasping a small-sized cup, the pressure distribution on the fingers was relatively uniform. In contrast, the pressure on the palm area was negligible, indicating that the thumb, middle finger, and index finger bear the majority of the gripping force, with relatively smaller contributions from other regions. Due to the small contact area between the cup and the palm, precise fingertip force is required during gripping, resulting in minimal local pressure on the palm, which is mainly concentrated in the little finger area (Fig. 4q). For medium-sized cups, the pressure distribution at the fingertips remains dominant, while the pressure on the palm increases significantly. The results showed that the pressure at the fingertips was relatively concentrated, with the middle finger and thumb bearing the majority of the load. Their pressure values were significantly higher than those in other regions. The pressure distribution on the palm was broader compared to that of the small cup, primarily originating from the palm’s edge and concentrating around the index finger area. The gripping force still mainly relied on the fingers; however, compared to the small cup, the force concentration on the fingers was less pronounced during the grasping of the medium-sized cup (Fig. 4r). When grasping a large cup, the pressure distribution across the palm and fingertips was relatively even. The pressure on the palm was primarily concentrated around the edges of the palm and near the thumb, while the central area of the palm experienced relatively lower pressure. Due to the extensive contact between the palm and fingers, a large cup applies pressure simultaneously to both the palm and fingertips, with pressure concentrated along the edges of the palm and on the larger contact surfaces of each fingertip. The recorded data show that the thumb, index finger, and middle finger experience the highest pressure, while the ring and little fingers experience relatively lower pressure (Fig. 4s). The pressure distribution across the palm when holding a large cup differs markedly from that of a medium-sized cup. This distribution pattern indicated that the cooperation between the palm and fingers was significant when grasping larger objects, resulting in a more uniform pressure distribution and greater force exertion. These results demonstrate that the sensor system is capable of generating detailed pressure distribution maps when grasping objects of different sizes. This highlights its potential wide application in flexible electronics, smart gloves, and human-computer interaction39.

Extracting Blood Pressure Signals from Pulse

Even though the sensor array captures pulse waves with exact and unique characteristics, extracting accurate blood pressure information from pulse signals remains challenging. In response to this challenge, a 4 × 4 electrode array was developed to monitor pressure changes at different locations, enabling precise identification of the strongest pulse wave signals. A machine learning-based linear regression model was also introduced to predict blood pressure. Specifically, the Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression method was used to establish a mapping between blood pressure and pulse signal characteristics, helping to make accurate blood pressure predictions from pulse features. PLS regression is suitable for high-dimensional, highly collinear, small sample data, effectively avoiding the curse of dimensionality and prediction instability. Compared to traditional regression, PLS enhances prediction stability by extracting latent variables. Compared to methods like Support Vector Regression (SVR), Lasso, and others, PLS requires fewer and more robust samples. It is also more interpretable than Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), making it easier to analyze how inputs influence outputs. PLS trains quickly and is suitable for real-time use in wearable devices. Here, an MF pressure sensor integrated with an FPCB was placed on the radial artery of the wrist, while a commercially available blood pressure monitor was applied to the contralateral arm for comparison of blood pressure measurements (Fig. 5a).

a BP measurement validation with MF sensor near the radial artery, compared to a commercial blood pressure monitor. b Arterial stiffness progression from healthy (I) to advanced stages (IV). c Physical configuration of the multifunctional sensor, emphasizing flexibility for human body compatibility. d Android app data interface displaying sensor signals for an intuitive performance overview. e, f Pulse signal measurement on the wrist, with pulse rate at 90/min and extracted parameters: PTT, RWTT, UT, P-wave, T-wave, and D-wave. g Subplots comparing predicted and actual BP values (SBP, DBP, MAP) with optimization adjustments. h Violin plot showing the distribution of predicted (blue) and reference (pink) BP values for SBP, DBP, and MAP. i SBP R² value of 0.983, indicating high prediction accuracy. j DBP R² value of 0.847, indicating moderate correlation and good prediction performance. k MAP R² value of 0.909, showing strong predictive performance. l SBP Bland-Altman plot: mean error of 0.20 mmHg, SD of 1.77 mmHg, consistency limit ± 1.96 SD. m DBP Bland-Altman plot: mean error of 0.82 mmHg, SD of 2.72 mmHg, consistency limit ± 1.96 SD. n MAP Bland-Altman plot: mean error of 0.40 mmHg, SD of 3.99 mmHg.

Given the intimate association between blood pressure and arteriosclerosis, a condition characterized by the thickening, loss of elasticity, and progressive hardening of arterial walls (Fig. 5b), arteriosclerosis has a direct impact on hemodynamics and alterations in blood pressure40,41. Therefore, we extracted pulse feature parameters related to blood pressure, including Pulse Transit Time (PTT), Reflected Wave Transit Time (RWTT), and Upstroke Time (UT)42,43,44,45,46. These parameters were then correlated with changes in blood pressure using regression analysis, and the sensor’s output was compared with reference blood pressure measurements obtained from a sphygmomanometer47,48,49,50. The circuit board features a flexible design, enabling it to conform more closely to the skin, which not only enhances wearing comfort and adaptability but also facilitates real-time monitoring and visualization of pulse waveforms (Fig. 5c). The real-time detected pressure signal was displayed on a smartphone-based user interface (Fig. 5d, movie S2). We successfully monitored periodic and stable pulse signals by detecting the physiological signals generated by pulse oscillations. Upon further amplification, the pulse waveform exhibited the characteristic structure of human pulse waves, comprising the P-wave, T-wave, and U-wave51,52,53,54 (Fig. 5e, f). We extracted significant physiological features from the pulse data via MATLAB signal processing (Fig. S22). The extraction process involved advanced signal processing techniques, including peak detection, filtering, and the calculation of time intervals. The pulse frequency and amplitude characteristics recorded by the sensor served as critical inputs for the linear regression model, enabling a subsequent correlation analysis with the data obtained from the commercial device (u703 blood pressure monitor, Fig. 5g). PLS regression was used to model the relationship between the feature matrix X (P-wave, T-wave, D-wave, RWTT, PTT) and the target matrix Y, which consisted of Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) and Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP)55,56. By extracting latent variables that maximize the covariance between X and Y, PLS effectively reduces dimensionality and addresses multicollinearity issues. The optimal number of components was determined through cross-validation to ensure model robustness57,58,59. This approach identified key variables and provided a predictive framework for analyzing the dataset Fig. S2.

To distinguish blood pressure variations between healthy individuals and those with atherosclerosis, we conducted multiple pulse waveform measurements using the sensor on different volunteers. Based on the degree of arterial stiffness, the participants were roughly divided into five groups (5–7 people per group): healthy young adults (18–24 years), middle-aged adults (30–35 years), older middle-aged adults (45–55 years), middle-aged adults with atherosclerosis (45–55 years), and elderly individuals with atherosclerosis (60–65 years). Representative and typical pulse waveforms were selected from each group for analysis. As shown in (Fig. S23), there are apparent differences in pulse waveforms at different stages, with noticeable waveform distortion and significantly shortened pulse transit time in individuals with advanced atherosclerosis. Furthermore, the blood pressure prediction results revealed a continuous increase in blood pressure levels with the progression of arterial stiffness. To verify the accuracy of the system, we compared the sensor measurements with those obtained using a commercial blood pressure (SBP, DBP) monitor (Fig. S24, 25). The results demonstrated good agreement between the two methods.

The blood pressure predictions generated by our custom-developed model and those obtained from a commercially available blood pressure monitor were compared. The violin plots visually illustrated the discrepancies between the predicted outcomes and the measurements obtained from the commercial device (Fig. 5h). This unequivocally indicated a high degree of concordance between the two detections, with the median error confined within the 0.1% to 1% range. These results further confirm the accuracy and reliability of our prediction model, providing strong support for its broader application in practical scenarios. Furthermore, to evaluate the fitting performance of the PLS model, we introduced linear regression to verify the accuracy of the results. The coefficients of determination (R²) for SBP, DBP, and Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) are 0.983, 0.847, and 0.909, respectively (Fig. 5i, j, k). These findings suggest that the PLS model demonstrates high accuracy in predicting blood pressure, with particularly strong performance in estimating SBP and MAP.

The pulse-blood pressure transfer function for various volunteers indicates that the sensor can accommodate individual blood pressure monitoring requirements. In the Bland–Altman analysis, we compared the blood pressure values estimated by the linear regression model with reference measurements obtained from a commercial blood pressure monitor. The results showed mean errors of –0.20, 0.82, and 0.40 mmHg for SBP, DBP, and MAP, respectively, with corresponding standard deviations of 6.17, 6.72, and 3.59 mmHg (Fig. 5l, m, n). Continuous monitoring of pulse waves could capture dynamic blood pressure variations, offering a more comprehensive understanding of blood pressure fluctuations compared to intermittent measurements. According to the (Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation) AAMI standard, the mean errors of SBP, DBP, and MAP (-0.20, 0.82, and 0.40 mmHg) and their standard deviations (6.17, 6.72, and 3.59 mmHg) all meet the requirements of ≤5 mmHg for mean error and ≤8 mmHg for standard deviation. The system also achieves Grade A under the (British Hypertension Society) BHS evaluation criteria.

Based on WPBPS measurements, the integrated monitoring of pulse and blood pressure provides substantial insights into the onset and progression of cardiovascular diseases. Importantly, the capability to continuously monitor blood pressure allows for more precise identification of blood pressure fluctuation patterns, which is crucial for the early diagnosis60,61,62,63, monitoring, and intervention of cardiovascular diseases53,54,64,65,66,67,68,69.

Discussion

This study presents a microfluidic pressure sensor based on MXene nanosheets and a TPU nanofiber substrate, combining excellent flexibility, breathability, and high sensitivity. The sensor exhibits superior performance metrics, including high sensitivity (652.1 kPa⁻¹), a wide sensing range (0–60 kPa), and a low detection threshold (1 Pa), alongside rapid response and durability under cyclic loading. It successfully captures multi-point pressure distributions and shows potential for precise blood pressure monitoring by correlating pulse wave features with arterial stiffness and vascular elasticity. In summary, the developed MXene-based pressure sensor offers significant potential for applications in smart wearables and health monitoring, particularly in continuous activity tracking and accurate blood pressure prediction.

Methods

Materials

Lithium fluoride (LiF, 99.99 wt%) was purchased from Zhengzhou Feiman Biotechnology Co. Ethanol (99.7 wt%) and hydrochloric acid were provided by China National Pharmaceutical Chemical Reagent Co. Ti3AlC2 MAX was purchased from 11 Technology Co. Dust-free cloth (80 g/m²) was provided by Dongguan Zhuo fang Industry Co. Thermoplastic polyurethane precursor (TPU) was purchased from Kexin Materials Co. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Mw: 1450 000), N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), Co3O4, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were purchased from McLean Chemical Co. All chemicals were purchased upon receipt without further purification.

Preparation of MXene solution

Add 1.5 g of LiF to 10 mL of 6 mol/L HCl and stir for 5 minutes to prepare the etching solution. Then, slowly add 2 g of Ti₃AlC₂ powder to the etching solution at 35 °C and stir for 24 hours. Wash the acidic suspension with deionized water and centrifuge at 3500 rpm (5 minutes per cycle), discarding the supernatant after each cycle, until the pH reaches 6. Finally, collect the MXene nanosheets by centrifuging at 3500 rpm for 5 min.

Preparation of TPU substrate

TPU (approximately 22 wt%) was added to a mixed solvent of THF and DMF (THF/DMF weight ratio of 1:1) and stirred at 70 °C for about 2 h until completely dissolved. The prepared solution was transferred into a syringe equipped with a 19-gauge needle. Electrospinning was performed at a voltage of 15 kV, with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/h, for approximately 3 hours. The environmental conditions were controlled at 35% humidity and 40 °C. The TPU solution was electrospun onto the surface of a rotating drum, whose rotation speed was optimized to ensure uniform deposition of nanofibers and to prevent the fibers from forming circular deposition tracks on the drum surface. The distance between the nozzle and the rotating drum was set to 20 cm. Continuous rotation of the drum allowed the fibers to uniformly cover the entire surface, achieving a consistent nanofiber membrane.

Screen printing of interdigital electrodes

We use a commercially available, scalable screen printing method to fabricate stretchable interdigitated electrodes (13 × 30 mm) using stretchable silver paste. First, we design screens with varying mesh counts and patterns. Then, a fibrous TPU membrane is placed beneath the screen, and both components are securely fixed onto the printer. After setup, the silver paste is precisely applied to the screen, and a squeegee is used to pass over the screen at an optimal speed (5 cm/s) to print the cross-pattern onto the fabric. The printed nanofiber is transferred to an oven and dried at 60 °C for 15 min. Finally, we used silver-based conductive adhesive to connect the stretchable silver interdigital electrodes to the wires.

MXene-based sensing layer fabrication

The MXene-based sensing layer was fabricated through a soaking method. Initially, the dust-free fabric was immersed in a self-prepared 5 mg/mL MXene aqueous dispersion, followed by drying at 60 °C for 30 minutes. This procedure was repeated 2 times to achieve the desired MXene sensing fabric.

Fabrication of MXene-based pressure sensor

The MXene-based composite fabric and stretchable silver interdigital electrodes functioned as the sensing and electrode layers, respectively. A polyurethane adhesive was applied at the four corner points to connect the fabric and TPU fiber membrane, thereby constructing the pressure sensor.

Machine learning linear regression model

A pulse signal preprocessing algorithm was created in MATLAB. A two-step preprocessing process was used to remove noise from the raw pulse current signals. First, a Gaussian smoothing filter (window size = 50, σ = 1) was applied to reduce high-frequency noise. Then, a 4th-order Chebyshev Type I high-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of 0.5 Hz and a passband ripple of 0.5 dB was used to eliminate baseline drift caused by movement or electrode instability. The final filtered signal had better clarity and stability, making it suitable for further feature extraction and waveform analysis (Fig. S22). After preprocessing, features were extracted from the pulse signal for training and prediction. The average values of these features were correlated with the SBP and DBP measured by a blood pressure cuff. The MAP was calculated as MAP = (SBP + 2 × DBP)/3.

Pulse sensor measurements were collected with a 5-minute interval between two blood pressure tests to ensure the physiological stability of the subjects and the accuracy of the predictions.

Characterization and Measurement

The morphology and structure of the sensing layer and substrate were characterized using a scanning electron microscope (G300, Carl Zeiss Ag). Additional structural and compositional analysis of the MXene sensing layer, which constitutes the key material of the sensing layer, was performed using transmission electron microscopy (Talos F200X G2 TEM), X-ray diffraction (D8 ADVANCE), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (Thermo ESCALAB 250XI), and energy dispersive spectroscopy (G300, Carl Zeiss AG). The electromechanical performance of the pressure sensor was tested using an electrochemical workstation (PGSTAT204N Electrochemical Workstation) and a mechanical testing machine (ZQ-990B, Zhique). The blood pressure values predicted by the developed sensor were compared with those obtained from a commercial blood pressure monitor (YE680CR, Yuwell).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study [and training/validation datasets] is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Kim, Y. et al. A bioinspired flexible organic artificial afferent nerve. Science 360, 998–1003 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. Conjunction of triboelectric nanogenerator with induction coils as wireless power sources and self-powered wireless sensors. Nat. Commun. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13653-w (2020).

Sun, Q. et al. Active matrix electronic skin strain sensor based on piezopotential-powered graphene transistors. Adv. Mater. 27, 3411–3417 (2015).

Benjamin, E. J. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 137, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558 (2018).

Li, Z., Zhang, B., Li, K., Zhang, T. & Yang, X. A wide linearity range and high sensitivity flexible pressure sensor with hierarchical microstructures via laser marking. J. Mater. Chem. C. 8, 3088–3096 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Wide-humidity range applicable, anti-freezing, and healable zwitterionic hydrogels for ion-leakage-free iontronic sensors. Adv. Mater. 35, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202211617 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Self-powered ultrasensitive pulse sensors for noninvasive multi-indicators cardiovascular monitoring. Nano Energy 81, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.105614 (2021).

Baek, S. et al. Spatiotemporal measurement of arterial pulse waves enabled by wearable active-matrix pressure sensor arrays. ACS Nano 16, 368–377 (2021).

Panwar, M., Gautam, A., Biswas, D. & Acharyya, A. PP-Net: a deep learning framework for PPG-based blood pressure and heart rate estimation. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 10000–10011 (2020).

Elgendi, M. et al. The use of photoplethysmography for assessing hypertension. npj Digital Med. 2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0136-7 (2019).

Liu, T. et al. Multichannel flexible pulse perception array for intelligent disease diagnosis system. ACS Nano 17, 5673–5685 (2023).

Meng, K. et al. Kirigami-inspired pressure sensors for wearable dynamic cardiovascular monitoring. Adv. Mater. 34, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202202478 (2022).

Kaisti, M. et al. Hemodynamic bedside monitoring instrument with pressure and optical sensors: validation and modality comparison. Adv. Sci. 11, https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202307718 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Bioadhesive and conductive hydrogel-integrated brain-machine interfaces for conformal and immune-evasive contact with brain tissue. Matter 5, 1204–1223 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Engineering electrodes with robust conducting hydrogel coating for neural recording and modulation. Adv. Mater. 35, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202209324 (2022).

Yu, C. et al. Chronological adhesive cardiac patch for synchronous mechanophysiological monitoring and electrocoupling therapy. Nat. Commun. 14, 6226 (2023).

Lee, Y. et al. Standalone real-time health monitoring patch based on a stretchable organic optoelectronic system. Sci. Adv. 7, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abg9180 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Monitoring of the central blood pressure waveform via a conformal ultrasonic device. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 687–695 (2018).

Tian, G. et al. A nonswelling hydrogel with regenerable high wet tissue adhesion for bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 35, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202212302 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Flexible accelerated-wound-healing antibacterial MXene-based epidermic sensor for intelligent wearable human-machine interaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202208141 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Bioadhesive ultrasound for long-term continuous imaging of diverse organs. Science 377, 517–523 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. High-performance piezoresistive flexible pressure sensor based on wrinkled microstructures prepared from discarded vinyl records and ultra-thin, transparent polyaniline films for human health monitoring. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 13064–13073 (2022).

Xu, H. et al. A fully integrated, standalone stretchable device platform with in-sensor adaptive machine learning for rehabilitation. Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43664-7 (2023).

Ha, K.-H. et al. Stretchable hybrid response pressure sensors. Matter 7, 1895–1908 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Healable, degradable, and conductive MXene nanocomposite hydrogel for multifunctional epidermal sensors. ACS Nano 15, 7765–7773 (2021).

Kant, C., Mahmood, S., Seetharaman, M. & Katiyar, M. Large-area inkjet-printed flexible hybrid electrodes with photonic sintered silver grids/high conductive polymer. Small Methods 8, https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.202300638 (2023).

Lee, G. et al. Crocodile-Skin-Inspired Omnidirectionally Stretchable Pressure Sensor. Small 18, https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202205643 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. Bioinspired microspines for a high-performance spray Ti3C2Tx MXene-based piezoresistive sensor. ACS Nano 14, 2145–2155 (2020).

Huang, Y. et al. Arteriosclerosis assessment based on single-point fingertip pulse monitoring using a wearable iontronic sensor. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 12, https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202301838 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Wearable, washable, and highly sensitive piezoresistive pressure sensor based on a 3D sponge network for real-time monitoring human body activities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 46848–46857 (2021).

Ye, X. et al. All-textile sensors for boxing punch force and velocity detection. Nano Energy 97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107114 (2022).

Chao, M. et al. Breathable Ti3C2Tx MXene/protein nanocomposites for ultrasensitive medical pressure sensor with degradability in solvents. ACS Nano 15, 9746–9758 (2021).

Lei, D. et al. Roles of MXene in pressure sensing: preparation, composite structure design, and mechanism. Adv. Mater. 34, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202110608 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Large-Area All-textile pressure sensors for monitoring human motion and physiological signals. Adv. Mater. 29,https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201703700 (2017).

Gao, Y. et al. Microchannel-confined MXene based flexible piezoresistive multifunctional micro-force sensor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201909603 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. Wearable pressure sensors based on MXene/tissue papers for wireless human health monitoring. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 60531–60543 (2021).

Zhao, P. et al. All-Organic Smart Textile Sensor for Deep-Learning-Assisted Multimodal Sensing. Advanced Functional Materials 33, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202301816 (2023).

Lu, L., Jiang, C., Hu, G., Liu, J. & Yang, B. Flexible noncontact sensing for human–machine interaction. Adv. Mater. 33, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202100218 (2021).

Tao, K. et al. Deep-learning enabled active biomimetic multifunctional hydrogel electronic skin. ACS Nano 17, 16160-16173,(2023).

Li, S. et al. Monitoring blood pressure and cardiac function without positioning via a deep learning–assisted strain sensor array. Sci. Adv. 9, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh0615 (2023).

Cheung, A. K. et al. International consensus on standardized clinic blood pressure measurement – a call to action. Am. J. Med. 136, 438-445–e431 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Wearable energy-smart ribbons for synchronous energy harvest and storage. Nat. Commun. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13319 (2016).

Mulvaney, S., Canali, S., Schiaffonati, V. & Aliverti, A. Challenges and recommendations for wearable devices in digital health: Data quality, interoperability, health equity, fairness. PLOS Digital Health 1, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000104 (2022).

Wu, P., Wang, W., Chang, F., Liu, C. & Wang, B. DSS-Net: dynamic self-supervised network for video anomaly detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 26, 2124–2136 (2024).

Imani, S. et al. A wearable chemical–electrophysiological hybrid biosensing system for real-time health and fitness monitoring. Nat. Commun. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11650 (2016).

Ma, K. et al. Therapeutic and prognostic significance of arachidonic acid in heart failure. Circulation Res. 130, 1056–1071 (2022).

Guo, W. et al. Bio-inspired two-dimensional nanofluidic generators based on a layered graphene hydrogel membrane. Adv. Mater. 25, 6064–6068 (2013).

Zhan, H. et al. Solvation-involved nanoionics: new opportunities from 2D nanomaterial laminar membranes. Adv. Mater. 32, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201904562 (2019).

Li, X. et al. A flexible Zn-ion hybrid micro-supercapacitor based on MXene anode and V2O5 cathode with high capacitance. Chem. Eng. J. 428, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130965 (2022).

Yue, Y. et al. 3D hybrid porous Mxene-sponge network and its application in piezoresistive sensor. Nano Energy 50, 79–87 (2018).

Ding, L. et al. Effective ion sieving with Ti3C2Tx MXene membranes for production of drinking water from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 3, 296–302 (2020).

Kang, Y., Xia, Y., Wang, H. & Zhang, X. 2D Laminar Membranes for Selective Water and Ion Transport. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201902014 (2019).

Kario, K. Management of hypertension in the digital era. Hypertension 76, 640–650 (2020).

Hua, J. et al. Wearable cuffless blood pressure monitoring: From flexible electronics to machine learning. Wearable Electron. 1, 78–90 (2024).

Wu, J., Qin, C., Sun, Q., Fu, C. & Wang, M. Accordion-inspired flexible pressure sensor based on folded interdigital electrode. IEEE Sens. J. 25, 4290–4297 (2025).

Lee, Y. & Ahn, J.-H. Biomimetic Tactile Sensors Based on Nanomaterials. ACS Nano 14, 1220–1226 (2020).

Shao, Q. et al. A sensitivity enhanced touch mode capacitive pressure sensor with double cavities. Microsyst. Technol. 29, 755–762 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. A wearable electrochemical biosensor for the monitoring of metabolites and nutrients. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 1225–1235 (2022).

Gao, Y. et al. Comparison of Transradial Access and Transfemoral Access for Diagnostic Cerebral Angiography in the Elderly Population. World Neurosurg. 181, e411–e421 (2024).

Zhang, S., Suresh, L., Yang, J., Zhang, X. & Tan, S. C. Augmenting Sensor Performance with Machine Learning Towards Smart Wearable Sensing Electronic Systems. Advanced Intelligent Systems 4, https://doi.org/10.1002/aisy.202100194 (2022).

Lai, Q.-T., Sun, Q.-J., Tang, Z., Tang, X.-G. & Zhao, X.-H. Conjugated Polymer-Based Nanocomposites for Pressure Sensors. Molecules 28, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28041627 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. High-precision flexible sweat self-collection sensor for mental stress evaluation. npj Flexible Electronics 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-024-00333-z (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Highly sensitive in-situ growth gold dendrite structure electrochemical sensor for early Alzheimer’s disease screening. Chemical Engineering Journal 490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.151644 (2024).

Alam, M. M. et al. Ultra-flexible nanofiber-based multifunctional motion sensor. Nano Energy 72, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2020.104672 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Flexible electronics for cardiovascular monitoring on complex physiological skins. iScience 27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.110707 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Synergy of Porous Structure and Microstructure in Piezoresistive Material for High-Performance and Flexible Pressure Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 19211–19220 (2021).

Blake, G. J., Rifai, N., Buring, J. E. & Ridker, P. M. Blood Pressure, C-Reactive Protein, and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Events. Circulation 108, 2993–2999 (2003).

Zheng, Y. et al. Smart Materials Enabled with Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare Wearables. Advanced Functional Materials 31, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202105482 (2021).

Wong, K. K. L., Fortino, G. & Abbott, D. Deep learning-based cardiovascular image diagnosis: A promising challenge. Future Gener. Computer Syst. 110, 802–811 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No.ZR2022QF120), Qingdao Postdoctoral Fund (No.QDBSH20230101005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C. led the conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software development, validation, and visualization. C.W. contributed to the software. W.W. and Y.L., and S.S.G., and L.Z. wrote the original draft and contributed to review and editing. H.K. supervised the project, acquired funding, and contributed to conceptualization, data curation, and writing. X.C. and H.K. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (QDU-HEC-2024457). Written informed consents were obtained from each of the individuals involved. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Wang, C., Wei, W. et al. Flexible and sensitive pressure sensor with enhanced breathability for advanced wearable health monitoring. npj Flex Electron 9, 101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00469-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00469-6

This article is cited by

-

Wearable sensors in health activity analysis: real-time monitoring and feedback

International Journal of Information Technology (2025)