Abstract

Wide linear range and fast response of tactile sensors are crucial for simplifying signal conversion and enhancing real-time perception. However, traditional tactile sensors struggle to control force-electric response and viscoelastic hysteresis, limiting linear range and response speed. Inspired by the motion of the sea urchin tooth plate, this study proposes a tooth plate flexible tactile sensor (TPFTS), which integrates a bio-inspired elastomeric structure with conductive foam to achieve stress–strain tunability. The sensor achieves linear regulation of force-electric response, with a wide liner range (80-606 kPa with R2 = 0.988), fast response and recovery time (29/24 ms), and excellent stability (over 20000 cycles). Additionally, TPFTS maintains stable signal output even with severe physical damage (signal stability >95% with 8% volume loss). With superior performance, TPFTS has been applied in multi-degree-of-freedom force sensing, omnidirectional motion control, and wearable sensing, demonstrating its potential in health monitoring and human-machine interaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tactile sensors are capable of quickly perceiving, collecting, and converting environmental information, making them widely applicable in fields such as human-machine interaction1,2,3,4, smart healthcare5,6,7, intelligent control8,9,10,11, and robotic sensing12,13,14,15. Among various types of tactile sensors, capacitive tactile sensors have gained increasing attention from researchers due to their simple structure, low manufacturing cost, and ease of integration16,17,18. To meet the diverse application environments and the demand for fast and efficient perceptual interactions, there are rising expectations for capacitive tactile sensors to offer wide linear ranges and fast response capabilities19. The wide linear range helps the sensor maintain stable and predictable output responses over a large stress range, thus supporting data acquisition and processing in multi-level force sensing and complex operation scenarios. Fast response capability, on the other hand, determines whether the sensor can quickly capture and feedback external stimuli in dynamic contact and real-time control tasks, which is crucial for improving the immediacy and accuracy of interaction.

The customizable sensing performance of tactile sensors is primarily influenced by their mechanical properties, such as Young’s modulus, hysteresis, and the creep and relaxation of the active layer. Adjusting the Young’s modulus of the active layer allows for the transmission of different tactile feedback, enabling the sensor to provide specific responses for target applications. Therefore, wide modulatability is crucial for customizing sensor performance. Additionally, traditional tactile sensors with soft elastomers exhibit viscoelastic behavior, which limits the sensor’s performance, resulting in significant signal drift, high hysteresis, and slow response times. In summary, enhancing the mechanical properties of the sensor to achieve high-performance capacitive tactile sensors with both a wide linear range and fast response is a key challenge in current soft perception research. Structural design is a critical approach to improving the performance of capacitive tactile sensors20,21,22,23. Compared to enhancing intrinsic material properties, structural-level modulation offers greater flexibility, especially in optimizing stress conduction paths, deformability, and the linear relationship of capacitance response24. Researchers have proposed various microstructural design strategies to enhance sensory performance. These strategies include microarray structures, such as micro pyramids25,26, micro cages27, micro hemispheres28,29, and micro cracks30,31,32,33, which enhance localized stress concentration and improve sensor sensitivity. Other approaches involve porous foam structures34,35,36,37,38 and wrinkled configurations39,40,41 to adjust the overall compression modulus and deformation recovery ability. Additionally, gradient structures37 or multi-layered designs42 are employed to achieve multi-stage stress responses and tunable range. Moreover, novel designs like programmable deployable structures43,44 are utilized to enhance multi-dimensional sensing and control deformation paths. Nevertheless, existing design approaches continue to encounter difficulties in simultaneously optimizing both the wide linear range and rapid response characteristics. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a novel structural strategy that can precisely control stress-strain behavior while ensuring consistent and stable responses.

In nature, many organisms have developed efficient structures through long-term evolution that combine controllable compliance deformation with response stability, providing rich inspiration for the design of flexible sensors45,46,47,48,49,50,51. This work is inspired by the sea urchin’s feeding mechanism, where the coordinated motion of tooth plates and muscles creates a helical contraction. Using this principle, we design a tooth plate flexible tactile sensor (TPFTS) with stress-strain tunability and programmable sensing features. The research path of this work is as follows: First, the deformation mechanism of the elastomer is analyzed; Then, its structure is optimized algorithmically and the sensor’s performance is rigorously tested under various conditions; Finally, the TPFTS is validated in practical applications such as physiological monitoring and robotics. Furthermore, the experimental and fabrication details are elaborated in the Supporting Information.

The innovation of this work is introducing a sea urchin tooth plate-inspired elastomer for controllable helical deformation, integrated with CNTs (Carbon Nanotubes) foam for a rigid–soft hybrid tactile sensor. This biomimetic design enables programmable optimization of performance metrics, offering significant potential for wearable devices, health monitoring, and human–machine interaction.

Results

Inspiration and design of the TPFTS structure

The sea urchin’s tooth plate system enables precise movement via a spiral mechanism driven by its muscle-tooth structure. Our sensor’s design is bio-inspired precisely in its structural configuration, which mimics this natural principle. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, similar to how the muscle’s action on the tooth results in spiral motion, the specific geometry of our elastomer is designed to undergo controlled helical deformation under compression. This bio-inspired structural approach enhances the sensor’s mechanical performance.

a Bio-inspired elastomer-based TPFTS design, inspired by the sea urchin tooth plate mechanism. b Response speed and wide linear range collaborative optimization strategy. c Analysis of TPFTS’s robustness under physical damage. d Performance comparison of TPFTS with related studies. e Multi-channel sensing and intelligent interaction applications.

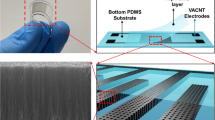

As illustrated in Fig. 1b, a bio-inspired elastomeric structure is designed based on the motion characteristics of the sea urchin tooth plate, leading to the development of the TPFTS. The TPFTS consists of a TPU (Thermoplastic Polyurethane) encapsulation layer, soft wires, an elastomer, and a sensing layer. In this design, the TPU layers serve as flexible encapsulation, protecting the internal components while ensuring mechanical integrity. The soft wires provide stable electrical transmission from the sensing layer to the external measurement system. The core functionality arises from the synergistic interaction between the embedded elastomer and the sensing layer: the bio-inspired elastomer modulates the capacitive response of the sensor by regulating the deformation distribution within the conductive foam sensing layer. Furthermore, the superior mechanical properties of the elastomer contribute to extending the sensing range by bearing part of the external load, while its strain regulation on the sensing layer enhances both sensitivity and stability. This synergy effectively governs the relationship between applied stress and output electrical signals. The sensing layer is fabricated from foamed silicone rubber, with CNTs attached to the pore surfaces to form a conductive network (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The sensing component of the TPFTS primarily consists of an elastomer and CNTs foam. The foam, made from silicone rubber, has CNTs attached to its pore surfaces, forming a conductive network. Detailed microstructure characterization and elemental content analysis of the sensor are provided (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). The elastomer, embedded inside the foam, undergoes a V beam motion that mimics the spiral contraction of the tooth, enabling controlled regulation of the foam’s volume. Additionally, the elastomer’s cross beam undergoes a spiral downward motion during compression, similar to the muscle’s role in the sea urchin, providing circumferential constraints on the foam and adjusting the TPFTS’s overall stiffness, effectively enhancing its range (Supplementary Movie 1). As the bio-inspired elastomer guides the foam’s deformation, the changes in the conductive CNTs network alter the TPFTS’s force-electric response. Furthermore, the structural design of the elastomer allows programmable control of foam compression, optimizing both the range and linearity of the TPFTS. Thanks to the bio-inspired elastomer’s excellent mechanical properties and spiral contraction-based compression mechanism, the viscoelastic hysteresis of traditional foam materials is greatly reduced, improving the TPFTS’s response speed.

As shown in Fig. 1b, the capacitance of the single conductive foam exhibits super nonlinear decay with the applied compressive strain. The capacitance change is directly related to the foam volume. We introduce f(V) to demonstrate how adjusting the volume change can control the sensor’s response time, Tr.

where σ represents the stress applied to the sensor, while α and γ are constants related to the structural characteristics of the TPFTS, which can be fitted based on experimental results. Moreover, f(V) is the function that describes the effect of volume change on the response time of the TPFTS, and E denotes the elastic modulus of the TPFTS. Similarly, the range of TPFTS can also be expressed by f(V):

where ∆C and C0 represent the change in capacitance and the initial capacitance, respectively, and β is a constant related to the structural characteristics of the TPFTS, which can be fitted based on experimental results.

Based on the guiding effect of the bio-inspired elastomer structure on the foam, the volume change function of the TPFTS can be expressed in terms of the structural parameters as follows:

where D represents the outer diameter of the elastomer, h denotes the height, N is the number of V beams, w2 and w3 are the width and thickness of the V beams, respectively, and θ2 is the bending angle of the V beams. Equations (1–3) indicate that the volume-controllable guidance of the elastomer allows for the collaborative optimization of the TPFTS’s response speed and linear range. The detailed derivation of the equations can be found (Supplementary Note 1).

Figure 1c demonstrates the exceptional performance of the TPFTS in terms of robust sensing capabilities. Even with a volume loss of up to 8%, the signal stability of the TPFTS remains above 95%, indicating its remarkable fault tolerance and adaptability under harsh conditions. As shown in Fig. 1d, the TPFTS achieves a wide liner range (80-606 kPa with R² = 0.988) and fast response and recovery time (29/24 ms). Owing to its superior performance in both linear range and response speed, the TPFTS can demonstrate in experimental tests for health monitoring, multi-degree-of-freedom force feedback, robotic motion control, and human–machine interaction, as shown in Fig. 1e. In particular, the 4-DOF (four degrees of freedom) force feedback system refers to translational motion along the z-axis combined with rotational motions around the x, y, and z axes. In conclusion, the sensor effectively mitigates external interference, enabling precise decoupling measurements of external torque and force in multi-dimensional spaces. This capability significantly extends the application of flexible tactile sensors in fields such as robotic collaboration and omnidirectional force sensing.

Elastomer structural design and characterization

Figure 2 illustrates the design principles and structural optimization methods for the bio-inspired elastomer. As shown in Fig. 2a, the structural parameters of the elastomer directly affect the sensing performance of the TPFTS. The key parameters of the elastomer are defined and described as follows: The elastomer consists of a hollow ring with a fixed height H and a variable height h, an inner diameter d, and an outer diameter D. Six parallelogram-shaped cutouts are evenly distributed along the cylindrical surface of the ring. The width of each cutout is w1, and the angle is θ1. The V beam is centrally placed within each cutout, with a width of w2, thickness of w3, initial angle of θ2, and length l.

a Loading method of TPFTS and elastomer structural parameters. b Elastomer structural spiral compression motion simulation and experimental analysis. c Simulation of pressure on the elastomer. d Simulation of elastomer volume change rate. e Experimental verification of pressure based on simulation optimization. f Experimental verification of volume change based on simulation optimization.

In addition, based on the loading method shown in Fig. 2a, static simulations and actual compression tests of the elastomer were conducted. Figure 2b demonstrates the deformation simulation and experimental analysis of the elastomer under initial parameters. During the 0-80% compression process, the static finite element simulation deformation and the actual compression experiments show good consistency, confirming that finite element simulation provides a reliable basis for guiding the structural optimization of the elastomer. This enabled us to reduce experimental trial-and-error and to systematically identify key parameter influences prior to fabrication. The volume change of the hollow region inside the biomimetic elastomer, f(V), is related to the degree of convergence of the V beams towards the center. Since the arrangement angles of the inclined rods are related to θ1 and θ2, their ends converge toward the center during the compression process. The central cavity volume can be approximated as a hollow cylinder, and during compression, the cavity volume is equivalent to the hollow cylinder minus the swept volume of all V beams. Considering the limitations of general manufacturing processes and the demand for industrial robot interaction scenarios, the basic dimensions H, h, d, w2, w3, and D are set as constants.

Due to the geometric constraints inherent in the elastomer, the optimized parameters, θ1, θ2, w1, and l, can be simplified to just θ1 and θ2. The pressure represents the potential operational range of the TPFTS, while a high-volume change rate indicates that the foam can achieve greater compression and demonstrate a faster response during recovery. Additionally, for a given set of structural parameters, the volume-pressure relationship during the 0-80% compression phase directly influences the linearity of the TPFTS.

Based on the validated simulation framework, Fig. 2c, d present the results of the multi-parameter optimization of the elastomer’s structure. Figure 2e and f compare the experimental and simulation results for six different structural configurations, with an average pressure deviation of less than 0.4% and an average volume change rate deviation of less than 0.2%. These results confirm the reliability and effectiveness of the simulation-based optimization method. Detailed optimization results and the corresponding structural parameter sets are provided (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Through the simulation-guided multi-parameter optimization process, Group 1 is identified as the optimal structural configuration, which directly informed the subsequent experimental validation and sensor fabrication.

Dielectric and mechanical behavior of TPFTS

Figure 3 presents the mechanical and inductive characteristics of the TPFTS. As shown in Fig. 3a, compression was evaluated up to 80%, beyond which the response is dominated by silicone rubber densification rather than elastomer-guided deformation. At this strain, the TPFTS sustains a pressure of 692 kPa, approximately 3.02 times higher than that of pure foam (229 kPa). The increase in pressure can be attributed to two factors. First, the embedded biomimetic elastomer, with its superior mechanical properties, provides higher resistance to external deformation compared to foam material under the same strain. Second, unlike pure foam that exhibits positive Poisson’s ratio deformation under compression, which restricts lateral contraction and slows down the contact of CNTs particles, the biomimetic elastomer is designed with a helical contraction mechanism that enables near-zero or even negative Poisson’s ratio behavior. This structural regulation allows more efficient lateral deformation, facilitating rapid CNTs contact and promoting a more linear sensing response. As a result, under the same compression limit, the foam in the TPFTS undergoes a higher degree of compression, thereby extending the effective sensing range.

a Strain-pressure analysis during the 0-80% compression process. b Cyclic load mechanical response analysis of TPFTS at 10%, 25%, 40%, 55%, and 70% compression strain. c Capacitance response analysis of TPFTS during 0–80% compression strain. d Capacitance response analysis of pure foam sensor during 0–80% compression strain. e Response time and recovery time testing of TPFTS. f Signal variation of TPFTS under step-change loading pressure. g Response analysis of TPFTS under cyclic loading with speeds of 0.5–2 mm/s. h Stability analysis of TPFTS under 20,000 cyclic loadings. i Performance comparison of TPFTS with related sensors52,53,54,55,56.

Further details of the Poisson’s ratio effect and its influence are analyzed. Conventional tactile sensors exhibit positive Poisson’s ratio deformation under compression, which restricts lateral contraction and delays the effective contact of CNTs particles, thereby reducing response speed. In contrast, the structure shown in Fig. 2b enables zero Poisson’s ratio behavior. This design facilitates more efficient lateral deformation, allowing CNTs particles to establish contact more rapidly during compression, while simultaneously enabling capacitive tuning that extends the linear sensing range (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 3b shows the mechanical response of the TPFTS under variable cyclic compression between 10% and 70% strain. A maximum strain of 70% is selected to avoid material densification and potential structural damage that may occur beyond this level, thereby ensuring reliable evaluation within the effective deformation range of the elastomer. The mechanical signals demonstrate excellent consistency under these conditions, confirming that the TPFTS possesses good durability during prolonged cyclic loading.

Figure 3c, d compare the capacitance–pressure characteristics of the TPFTS and the pure foam sensor during the 0–80% compressive strain process. For the pure foam sensor, two quasi-linear regions are observed: a sensitivity of 0.019 kPa⁻¹ in the 25–100 kPa range and 0.020 kPa⁻¹ in the 173–214 kPa range. By contrast, the TPFTS demonstrated a much broader and more stable sensing performance. Specifically, across the full 0–606 kPa range, the TPFTS exhibited a sensitivity of 0.245 kPa⁻¹ with an overall linearity of R² = 0.984, representing superior linear response and pressure sensitivity. Furthermore, a more detailed segmented analysis is conducted to refine the evaluation of linearity. When the fitting criterion is raised to R² > 0.985, the sensor response is more appropriately described by two quasi-linear regions: 0–70 kPa with R² = 0.994, and 80–606 kPa with R² = 0.988. This analysis confirms that the elastomer embedded within the TPFTS effectively regulates foam deformation, enabling not only higher sensitivity but also a significantly wider linear sensing range compared with the pure foam sensor.

To ensure the reliability of these results, 10 independently fabricated TPFTS devices are tested. For each device, cyclic compression tests are performed with 50 cycles of uniform loading from 0–80% strain. The reported R² value is obtained from the averaged results across these devices. Each compression cycle provided 80 data points, and for clarity of presentation while maintaining statistical validity, the fitting curve in Fig. 3c is reconstructed using 500 uniformly distributed data points.

In addition, the hysteresis behavior is evaluated by comparing the loading and unloading pressure–capacitance responses during cyclic compression. The results indicate that the hysteresis ratio is below 1% across the 0–606 kPa range. Because the loading and unloading curves almost completely overlap, the hysteresis loop is visually indistinguishable, and the results are therefore reported descriptively rather than graphically. These findings confirm that the TPFTS exhibits negligible hysteresis and excellent repeatability under repeated loading–unloading cycles.

Furthermore, the macroscopic control of the contraction characteristics by the biomimetic elastomer also imparts a rapid response capability to the TPFTS. Figure 3e shows the response time (29 ms) and recovery time (24 ms) of the TPFTS. The results reveal a highly linear and reproducible relationship between the applied pressure (0–40 kPa) and the capacitive signal in Fig. 3f. Each pressure step produces a stable and proportional signal response, unequivocally confirming the sensor’s excellent linearity under controlled conditions. Each pressure step produces a stable and proportional signal response, unequivocally confirming the sensor’s excellent linearity under controlled conditions. Figure 3g illustrates the stable and repeatable pressure response of the TPFTS at varying compression speeds. The signal response of the TPFTS during 20,000 loading cycles is shown in Fig. 3h. During the initial 500 cycles, the sensor exhibited a cyclic stability error of about 4%, which is due to the settling of the foam–electrode interface and the structural preconditioning of the elastomer. After this short adjustment stage, the response stabilized, and the overall cyclic stability error across 20,000 cycles is maintained at only 0.24%, confirming the excellent durability and long-term reliability of the TPFTS. The calculation methods for sensor sensitivity and cyclic stability error are provided (Supplementary Note 2). Figure 3i compares the comprehensive performance of the TPFTS with related studies, highlighting its excellent overall performance. Detailed parameters for each performance indicator are provided (Supplementary Table 3).

More importantly, a notable phenomenon is observed: the strain–stress behavior of pure foam sensors becomes highly unstable when subjected to irreversible mechanical damage, such as surface scratches or partial material removal, leading to signal drift, distortion, and complete failure. In contrast, owing to the reliable constraint and guidance provided by the biomimetic elastomer, the TPFTS can maintain stable sensing performance even under these damage conditions. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, both types of sensors were intentionally damaged in a controlled manner, with defects including linear scratches, triangular notches, semicircular notches, and rectangular notches. Their force response was then evaluated under 0–80% cyclic compression. The degree of signal deviation was quantitatively evaluated using the correlation coefficient (R²), mean square error (MSE), and integral absolute error (IAE). Furthermore, a comprehensive deviation index, f, is introduced to systematically assess the impact of mechanical damage on sensing performance. Detailed descriptions of the size categories and evaluation metrics for controlled damage are provided (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Note 3).

a Mechanical cyclic performance analysis of the pure foam sensor after damage. b Mechanical cyclic performance analysis of the TPFTS after damage. c Comprehensive mechanical performance evaluation of the pure foam sensor and TPFTS under different physical damages. d Capacitance signal deviation of the pure foam sensor after damage. e Capacitance signal deviation of the TPFTS after damage. f Relationship between the maximum signal deviation of TPFTS and the volume loss. g Relationship between the average signal deviation of TPFTS and the volume loss.

The greater the impact of physical damage on the structural mechanical stability, the higher value of the f. Figure 4a and b show the mechanical cyclic performance of the pure foam sensor and TPFTS under the same physical damage conditions. Figure 4c further demonstrates the effect of different types of physical damage on the mechanical properties of the pure foam sensor and TPFTS under identical damage forms and scales. Compared to the pure foam sensor, the TPFTS exhibits superior mechanical stability, indicating that the TPFTS retains the potential to maintain its original strain characteristics even when damaged in harsh environments.

Furthermore, Fig. 4(d-g) presents a simulation of potential sensor damage under harsh operational conditions, achieved through artificially controlled damage behaviors. The capacitive signals of the damaged sensors under standard loading conditions were compared with the ideal signals to assess the degree of signal deviation. Figure 4d and e show the signal shifts of the pure foam sensor and TPFTS after L5, T5, S5, and R5 scratches, highlighting the relationship between the volume loss and the corresponding signal deviation. After damage, the signal deviation of the pure foam sensor increases significantly. In contrast, the TPFTS exhibits strong robustness under the same damage conditions. Figure 4f and g provide a detailed analysis of the capacitive signal shifts for TPFTS. When the maximum volume loss does not exceed 8% of the total volume, different notch shapes result in minimal signal disturbance, with a maximum deviation of approximately 0.08 and an average deviation of 0.06. Notably, in the linear scratch test, even when the scratch length exceeded 60% of the TPFTS diameter (L5), the signal deviation remained well within acceptable limits, with the maximum deviation only 0.001%. Different notch shapes caused only minimal signal disturbance to the TPFTS. With a maximum volume loss not exceeding 8% of the total volume, the maximum deviation is approximately 0.08, and the average deviation is 0.06. The experimental results demonstrate that the TPFTS exhibits exceptional fault tolerance and robustness, maintaining reliable sensing capabilities even under harsh operational conditions. This exciting phenomenon has not been reported in previous studies.

Potential applications of TPFTS

The bio-inspired structural design of TPFTS (Supplementary Table 5) delivers outstanding performance for applications in human motion monitoring and human-computer interaction. Figure 5 illustrates the application scenarios of the TPFTS in human motion monitoring and human-computer interaction. As shown in Fig. 5a, TPFTS can achieve the monitoring of nine different human physiological signals, including muscle movement (muscle force in the face, biceps, and forearms) and joint motion signals (fingers, neck, wrist, elbows, ankles, and knees). Furthermore, the TPFTS can be used to explore and understand various physiological activities and related parameters in detail (Supplementary Fig. 5). It is important to note that, in all human monitoring experiments, the sensor does not directly contact the skin. Instead, medical-grade, skin-friendly breathable tape is used to isolate the sensor from direct contact with the skin, thus minimizing potential risks associated with direct exposure of the TPFTS to human skin. The usage method and specific specifications of the tape are provided (Supplementary Fig. 6). Figure 5a presents a multifunctional wireless sensing system based on TPFTS. The capacitive signal variation is collected by a custom circuit board centered on the ESP32-S3-WROOM-1-N8 module, which integrates both control and wireless communication (Supplementary Fig. 7). For stable operation, the board is powered by a 5 V input and employs an LD1117-3.3 V regulator to supply the ESP32 and peripheral components. Additional features include LED indicators for status monitoring and multi-channel acquisition interfaces connected to GPIO pins. The system supports real-time Bluetooth transmission of physiological signals to smart devices for daily activity tracking, as well as data transfer via a TTL-to-USB module. The digital signal refers to the converted output after the ESP32 microcontroller processes the analog signal via its internal ADC (analog-to-digital converter). When transmitted to a computer through the TTL-to-USB module, the signals are in digital form (serial data stream), allowing for efficient storage.

Additionally, TPFTS is integrated into a wearable electronic glove that the user wears on their hand. The capacitive response signal from the finger flexion is used to determine the state of finger bending, allowing for the perception of hand motion. In Fig. 5b, seven different hand gestures were recognized 350 times, with an accuracy of 99.71%, demonstrating excellent motion recognition capabilities. Moreover, the electronic glove enables the user to intuitively control the movement of a robotic hand simply by moving their fingers. The glove uses capacitive changes from the TPFTS as input signals, which are then processed to generate a PWM (Pulse width modulation) signal, effectively controlling the movement of the robotic hand. This system allows for accurate representation of seven standard American gestures (as shown in Fig. 5b). The demonstration in further confirms that the robotic hand can rapidly and accurately follow and respond to the user’s hand movements (Supplementary Movie 2), highlighting the system’s vast application potential and innovative possibilities in the field of smart interaction.

Figure 6 illustrates the application of TPFTS in the field of soft robot collaboration, particularly in the areas of soft robot bending angle and grasping force sensing. Figure 6a shows the composition of the robot collaboration system, including the robot body, soft gripper, sensors, pneumatic tubing, and data acquisition card. Figure 6b presents the workflow of the soft robot control system based on TPFTS. The system controls the robot’s movement and grasping by sensing both the angle and force. When the sensor signal experiences a decline in response, the system provides feedback through the signal processing module and adjusts the pneumatic pressure of the soft robot. By integrating the sensing module with the robot control system, stable grasping functionality is achieved. The sensing module detects object contact through pressure sensors and conducts pressure monitoring in conjunction with the signal processing results. Ultimately, the system adjusts the pneumatic pressure through the feedback mechanism to enhance the stability of grasping and bending angle control.

a Soft robot and industrial robot integrated system based on TPFTS. b Robot collaboration workflow. c Perception of soft robot bending angle during pressure variation. d Perception of contact force on the same object by the soft robot during pressure variation. e Perception of contact force on different objects by the soft robot under constant pressure.

As shown in Fig. 6c, TPFTS enables soft robot bending angle perception. By adjusting the pneumatic pressure, the soft robot’s bending is driven. As the air pressure increases from 0 MPa to 0.18 MPa, the TPFTS sensor generates significant capacitive signal changes, directly reflecting the variations in the soft robot’s bending angle. This indicates that TPFTS can accurately perceive the bending angle of the soft robot under different air pressures, providing crucial data support for precise control of soft robots in complex operational environments. Figure 6d demonstrates TPFTS’s ability to sense the grasping force of the soft robot. By controlling the variation in pneumatic pressure, the soft robot can achieve different levels of grasping force. As the air pressure increases, the soft robot’s ability to grasp objects is enhanced, and the capacitive signal from the TPFTS sensor undergoes a noticeable change.

In Fig. 6e, when the soft robot performs grasping on cucumber, banana, and bottled water under the same pressure, the sensor shows distinct and measurable capacitive signal variations, indicating that TPFTS plays a crucial role in the precise perception and differentiation of objects during the soft robot’s grasping process. Through real-time monitoring and analysis of the capacitive signals, TPFTS effectively senses and controls the soft robot’s grasping force. This provides high-precision sensing feedback for soft robot collaboration, offering technical support for more accurate operations and efficient cooperation.

Figure 7 showcases the TPFTS’s capability for multidimensional force/torque decoupling under 4-DOF and 6-DOF loading. As illustrated in Fig. 7a, a 4-DOF force/torque measurement device was designed using TPFTS (Supplementary Fig. 8). The device comprises three SPS (spherical-prismatic-spherical) branches and one PS (prismatic-spherical) branch, with TPFTS acting as the prismatic joint in each. The SPS branches allow free movement, while the PS branch permits translation along the z-axis and rotation about three axes. Under external loads, the resulting motion compresses or stretches the TPFTS, generating corresponding signal responses.

The differential signals from the four branches can achieve precise decoupling of the four-degree-of-freedom force/torque (Supplementary Note. 4). The mapping relationship between the force and capacitive signals is as follows.

Where Fx, Fy, Fz, and Mz represent the external force/torque applied to the device, and ∆Ci (i = 1,…4) represents the capacitive response signals from the four sensors All parameters are known structural and mechanical parameters of TPFTS. There exists a mapping relation-ship between the four-degree-of-freedom external load and the capacitive variation. Therefore, by analyzing the changes in the capacitive signals from the four TPFTS units, precise decoupling of the four external force/torque dimensions can be directly achieved.

Furthermore, the decoupling perception capability of TPFTS is extended to six degrees of freedom. As shown in Fig. 7b, a measurement device with six-degree-of-freedom external force/torque decoupling capability has been designed. This system is expected to achieve omnidirectional movement perception and control feedback for special vehicles in harsh operational environments at long distances. The device consists of six SPS branches, with TPFTS serving as the prismatic joint in each branch (Supplementary Fig. 9). When subjected to external forces/torques, the six TPFTS units generate different capacitive signal responses. Decoupling analysis of the differential signals is performed to achieve precise decoupling of the six-degree-of-freedom external forces/torques. Which can achieve the control of omnidirectional movement of the Mecanum wheel vehicle (Supplementary Movie 3). When external forces or torques act on the device, the six TPFTS branches sense and convert them into capacitive signal changes. These signals are then pre-processed by a signal processing unit, which filters and amplifies the weak capacitive signals, converting them into voltage signals that are easier to handle. Next, a decoupling algorithm is used to analyze the capacitive signals from each branch, distinguishing the forces/torques in different degrees of freedom directions. Mathematical modeling and computational methods are applied to decouple the differences between the signals, ultimately achieving accurate decoupling of the six-degree-of-freedom forces and torques (Supplementary Note 5). The mapping relationship between the force and capacitive signals is as follows.

In summary, the multidimensional decoupling capability of TPFTS flexible tactile sensing technology holds significant potential for external force/torque perception. Through precise decoupling under four-degree-of-freedom and six-degree-of-freedom external loads, TPFTS can provide high-precision external force sensing and real-time feedback for industrial robots and intelligent control systems under complex conditions.

Discussion

This study presents a composite flexible tactile sensor inspired by the tooth plates of sea urchins. Through the geometric control and mechanical constraints of the biomimetic elastomer, the developed sensor demonstrates excellent rapid response capabilities (29/24 ms) within a wide linear range (0–606 kPa with R² = 0.984), alongside good sensitivity (0.25 kPa⁻¹) and cyclic stability (over 20,000 stable cycles). Experimental results reveal an unprecedented robust characteristic of the sensor, owing to the strong deformation constraint ability of the biomimetic elastomer. Even with over 8% volume loss, the sensor maintains stable signal responses superior to 95% of its original performance, indicating exceptional environmental adaptability and reliable operational potential. As a proof of concept, the sensor’s significant application potential in tactile sensing for robotic operations, human-machine interaction, and health monitoring has been successfully demonstrated. The design strategy, which integrates rapid response and a wide linear range, relies on the synergistic interaction between mechanical and electrical behaviors. This strategy significantly enhances sensor performance and suggests that new regulation strategies based on biomimetic elastomers may have broad applications in the future development of flexible tactile sensors.

Methods

Experimental material

Silicone rubber with the Shore hardness of 45 was sourced from Hongcheng Materials Company Ltd, China. Conductive TPU materials were provided by YouSu Company Ltd, China. Both the casting molds and conductive TPU components were fabricated using the Bambu Lab A1 3D printer, supplied by Top Bamboo Technology Company (Shenzhen, China). The HY-F662 two-component expandable foam silicone rubber was procured from Hongcheng Materials Company, Ltd, China. A water-based carbon nanotubes slurry with a solid content of 13% was obtained from Suzhou Carbon Ink Technology Co., Ltd., China. Hongsheng medical skin-friendly breathable tape (Hongsheng Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Model: HS-1234) was used to isolate the sensor from direct contact with human skin, ensuring safety during physiological monitoring experiments. Sensor fabrication was conducted under controlled temperature and pressure conditions using a DZF-6050 vacuum drying oven from Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd.

Preparation process

Equal masses (3 g each) of expandable foam silicone A-Liquid and B-Liquid were mixed and stirred at 60 rpm for 5 min using a magnetic stirrer to produce a foaming silicone mixture with vulcanization and foaming properties. The elastomer was prepared using silicone rubber with the Shore hardness of 45, and insulating TPU with the Shore hardness of 95, along with conductive silver glue, were used for bonding. The assembled structure was then placed in a mold. Next, the foaming silicone mixture was poured into the mold and left to cure in a sealed environment at 25 °C for 12 h, forming the sensor without CNTs. The sensor was subsequently immersed in a CNTs solution with a solid content of 13% and kept under 0.1 kPa pressure at 25 °C for 48 h. It was then placed in a drying oven at 120 °C for 8 h. Unattached CNTs and other impurities generated during preparation were removed using ultrasonic cleaning in ethanol. The resulting sensor is a cylindrical structure with dimensions of 10 mm in height and 20 mm in diameter.

Characterizations and measurements

The microstructure of the foam materials was observed using a Zeiss Gemini 360 field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM), and elemental composition mapping of the foam was analyzed with an Oxford Xplore 30 energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS). Mechanical performance testing of the sensors was carried out using an FBS-200N tensile testing machine from FURBS Company, while capacitance variations were measured by using LCR meter (IM 3570, HIOKI, Japan).

Consent for use of identifiable images

A 22-year-old healthy male was recruited from Yanshan University and gave informed consent before participation in the study. All figures containing potentially identifiable images of individuals were captured with the participants’ full awareness and cooperation. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals involved, granting permission to use and publish their images in this research.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format, they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Xu, Y. et al. In-sensor touch analysis for intent recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2411331 (2024).

Cho, J.-Y. et al. Tactile near-sensor computing systems incorporating hourglass-shaped microstructured capacitive sensors for bio-realistic energy efficiency. npj Flex. Electron 9, 34 (2025).

Sun, Z., Zhu, M., Shan, X. & Lee, C. Augmented tactile-perception and haptic-feedback rings as human-machine interfaces aiming for immersive interactions. Nat. Commun. 13, 5224 (2022).

Chun, S. et al. An artificial neural tactile sensing system. Nat. Electron 4, 429–438 (2021).

Luo, Y. et al. Motion-interference free and self-compensated multi-receptor skin with all gel for sensory enhancement. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2502196 https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202502196. (2025).

Song, X. et al. Omnidirectional and size-adaptive soft bending sensor for accurate human joint motion monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 71, 8069–8079 (2024).

Ma, Y. et al. Flexible hybrid electronics for digital healthcare. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902062 (2020).

Lin, W. et al. Highly programmable haptic decoding and self-adaptive spatiotemporal feedback toward embodied intelligence. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2500633 https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202500633. (2025)

Wei, C. et al. Octopus tentacle-inspired in-sensor adaptive integral for edge-intelligent touch intention recognition. Adv. Mater. 2420501 https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202420501. (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Self-powered and degradable humidity sensors based on silk nanofibers and its wearable and human–machine interaction applications. Chem. Eng. J. 497, 154443 (2024).

Dai, H. et al. Split-type magnetic soft tactile sensor with 3D force decoupling. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310145 (2024).

Li, N. et al. Fingertip-inspired spatially anisotropic inductive liquid metal sensors with ultra-wide range, high linearity and exceptional stability. Adv. Mater. (2025).

Li, T. et al. Robust and sensitive conductive nanocomposite hydrogel with bridge cross-linking–dominated hierarchical structural design. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk6643 (2024).

Qu, J. et al. Recent progress in advanced tactile sensing technologies for soft grippers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2306249 (2023).

Xie, Z. et al. A proprioceptive soft tentacle gripper based on crosswise stretchable sensors. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 25, 1841–1850 (2020).

Han, S. et al. Research progress of flexible piezoresistive sensors based on polymer porous materials. ACS Sens 9, 3848–3863 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Tactile sensing technology in bionic skin: A review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 220, 114882 (2023).

Gabbett, C. et al. Understanding how junction resistances impact the conduction mechanism in nano-networks. Nat. Commun. 15, 4517 (2024).

Chen, R. et al. Nonlinearity synergy: An elegant strategy for realizing high-sensitivity and wide-linear-range pressure sensing. Nat. Commun. 14, 6641 (2023).

Ji, B. et al. Bio-inspired hybrid dielectric for capacitive and triboelectric tactile sensors with high sensitivity and ultrawide linearity range. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100859 (2021).

Bai, N. et al. Graded intrafillable architecture-based iontronic pressure sensor with ultra-broad-range high sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 11, 209 (2020).

Qin, J. et al. Flexible and stretchable capacitive sensors with different microstructures. Adv. Mater. 33, 2008267 (2021).

Hong, Q. et al. 3D dual-mode tactile sensor with decoupled temperature and pressure sensing: Toward biological skins for wearable devices and smart robotics. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 404, 135255 (2024).

Zhao, Z. et al. Bicontinuous vitrimer heterogels with wide-span switchable stiffness-gated iontronic coordination. Sci. Adv. 10, eadl2737 (2024).

Ruth, S. R. A. et al. Rational design of capacitive pressure sensors based on pyramidal microstructures for specialized monitoring of biosignals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1903100 (2020).

Tao, K. et al. Deep-learning enabled active biomimetic multifunctional hydrogel electronic skin. ACS Nano 17, 16160–16173 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Localizing strain via micro-cage structure for stretchable pressure sensor arrays with ultralow spatial crosstalk. Nat. Commun. 14, 1252 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Bioinspired MXene-based piezoresistive sensor with two-stage enhancement for motion capture. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214503 (2023).

Wang, D., Li, B., Niu, S., Han, Z. & Ren, L. Novel iontronic pressure sensor coupling high sensitivity and wide-range for stiffness identification and long-distance precise motion control. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2413551 (2025).

Park, J., Kim, M., Lee, Y., Lee, H. S. & Ko, H. Fingertip skin–inspired microstructured ferroelectric skins discriminate static/dynamic pressure and temperature stimuli. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500661 (2015).

Wang, D. et al. A selective-response bioinspired strain sensor using viscoelastic material as middle layer. ACS Nano 15, 19629–19639 (2021).

Li, J. et al. High-fidelity, low-hysteresis bionic flexible strain sensors for soft machines. ACS Nano 18, 2520–2530 (2024).

Guo, Y. et al. Multifunctional hydrogel sensor with curved macro cracks: a strategy for high sensitivity and wide detection range. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2306820 (2023).

Guo, H. et al. Artificially innervated self-healing foams as synthetic piezo-impedance sensor skins. Nat. Commun. 11, 5747 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Stretchable and negative-Poisson-ratio porous metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 15, 392 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. High-performance foam-shaped strain sensor based on carbon nanotubes and Ti3C2 T x MXene for the monitoring of human activities. ACS Nano 15, 9690–9700 (2021).

Ha, K. et al. Highly sensitive capacitive pressure sensors over a wide pressure range enabled by the hybrid responses of a highly porous nanocomposite. Adv. Mater. 33, 2103320 (2021).

Sun, Q. et al. Highly stretchable MXene-based meta-aerogels with near-zero and negative Poisson’s ratios. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2308537 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202308537.

Du, D. et al. Rapid-response and highly sensitive piezocapacitive pressure sensor based on micro buckling periodic layers for wearable applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 5, 6149–6156 (2023).

Zhang, F. et al. Stress controllability in thermal and electrical conductivity of 3D elastic graphene-crosslinked carbon nanotube sponge/polyimide nanocomposite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901383 (2019).

Lv, C. et al. Ultrasensitive linear capacitive pressure sensor with wrinkled microstructures for tactile perception. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206807 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Highly robust and self-adhesive soft strain gauge via interface design engineering. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406432 (2024).

Jing, H. et al. Sign-switchable Poisson’s ratio design for bimodal strain-to-electrical signal transducing device. Adv. Mater. 37, 2413774 (2025).

Jin, Q. et al. 3D printing of capacitive pressure sensors with tuned wide detection range and high sensitivity inspired by bio-inspired kapok structures. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 45, 2300668 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. A star-nose-like tactile-olfactory bionic sensing array for robust object recognition in non-visual environments. Nat. Commun. 13, 79 (2022).

Guo, Z. H. et al. Bioinspired soft electroreceptors for artificial precontact somatosensation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo5201 (2022).

Zhou, J. et al. Mormyroidea-inspired electronic skin for active non-contact three-dimensional tracking and sensing. Nat. Commun. 15, 9875 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Finger-inspired rigid-soft hybrid tactile sensor with superior sensitivity at high frequency. Nat. Commun. 13, 5076 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Bionic recognition technologies inspired by biological mechanosensory systems. Adv. Mater. 2418108 https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202418108. (2025).

Liao, X. et al. A bioinspired analogous nerve towards artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 11, 268 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Bioinspired, omnidirectional, and hypersensitive flexible strain sensors. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200823 (2022).

Tian, Y. et al. Highly sensitive, wide-range, and flexible pressure sensor based on honeycomb-like graphene network. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 67, 2153–2156 (2020).

Xia, X. et al. Structural design and DLP 3D printing preparation of high strain stable flexible pressure sensors. Adv. Sci. 11, 2304409 (2024).

Huang, A. et al. A unique, flexible, and porous pressure sensor with enhanced sensitivity and durability by synergy of surface microstructure and supercritical fluid foaming. Appl. Surf. Sci. 618, 156661 (2023).

Feng, Z. et al. Capacitive sensors with hybrid dielectric structures and high sensitivity over a wide pressure range for monitoring biosignals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 6217–6227 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Skin-inspired capacitive flexible tactile sensor with an asymmetric structure for detecting directional shear forces. Adv. Sci. 11, 2305883 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 52375030, 52305308, 52505071); the S&T Program of Hebei (Project No. 246Z1802G); the Hebei Natural Science Foundation (Project No. E2024203254, No. E2024203067, No. E2025203232); the Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department(Project No. QN2025183); the Fundamental Innovative Research Development Project of Yanshan University(Project No. 2024LGQN008); the Opening Project of the Key Laboratory of Bionic Engineering (Ministry of Education, Jilin University; Grant Number KF2023003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y., D.W., and G.M. supervised the research. W.G. designed and performed the experiments. W.G., X.F., and X.Y. carried out the device fabrication and the performance measurement. W.G., C.L., and C.G. performed the theoretical analysis. W.G. and X.F. analyzed the data. W.G., D.W., Z.H., and L.R. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, W., Yao, J., Fei, X. et al. Sea urchin-inspired rigid-soft hybrid tactile sensor with wide linear range, fast response speed, and excellent robustness. npj Flex Electron 10, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00513-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41528-025-00513-5