Abstract

This study investigates the effect of microstructure on short-term and long-term oxidation behaviours of GH3536 superalloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion (LPBF), in which the superalloy is isothermally oxidised at 950 °C for 6 h and 500 h in air. The LPBF sample exhibits improved oxidation resistance compared with a wrought counterpart after long-term exposure. The effect of microstructure diversity between LPBF and wrought samples on oxidation behaviour is discussed. The cellular structure produced during the LPBF process acts as a rapid diffusion path to accelerate the formation of a protective film in the initial stage, leading to an enhancement in oxidation resistance for extended exposure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

GH3536 (also known as Hastelloy X), a Ni-based superalloy strengthened by a solid solution of Cr and Mo elements, is widely used in gas turbine engines and petrochemical reactors owing to its exceptional high-temperature strength, toughness, and corrosion resistance1,2,3. Most GH3536 alloys are used in extreme climates with high temperatures, oxidation levels, and long-term thermal cycles4. One scientific consensus is that corrosion is the main failure mode of superalloy components at high temperature5. Several efforts have been made to strengthen understanding of oxidation behaviour and determine a strategy for enhancing oxidation resistance6,7,8. Experiments exposing wrought GH3536 to high temperatures suggested that the dense Cr2O3 scale formed in air acts as a protective layer to inhibit further corrosion, whereas the porous Cr3C2 scale formed in a carbon-rich atmosphere was unable to hinder the consumption of Cr from the matrix7. In an air atmosphere, the GH3536 oxide thickness exhibited a parabolic time dependence where the variation in oxide film thickness was controlled by diffusion9. After long-term exposure to high-temperature air, an oxidation scale composed of an outer layer of Mn-rich spinel and an inner layer of Cr2O3, which creates a significant protective barrier, was formed on the surface. That is, as time increased, the oxidation rate gradually slowed down until it almost ceased10.

Layer-by-layer laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) is used to fabricate high-end and near-net-shape components11,12. Several studies have reported a range of LPBF alloys, including aluminium alloys, titanium alloys, stainless steel, and nickel-based superalloys13,14,15,16. The ultrafine microstructures formed by extremely rapid solidification during LPBF have been demonstrated to have impacts on material performance, including improved mechanical properties17 and good corrosion resistance18,19 in stainless steel and titanium alloys20, as well as excellent fatigue strength in aluminium alloys and nickel-based superalloys21,22. Meanwhile, this rapid manufacturing method using laser as the heat source is also widely used in machine parts repairing and functional coating23,24. The fabrication of superalloys such as GH3536 by LPBF technology can effectively enhance the material utilisation and design freedom25. However, the variation in observed properties, especially because of high-temperature oxidation in LPBF superalloys, also need to be investigated, and a specific microstructure should be considered. Some works on pure Cr26 and Nb–Si alloys27 conclude that there is a beneficial effect of refinements in microstructure and texture intensity generated during the LPBF process on corrosion resistance. The improvement of oxidation resistance in the LPBF Hastelloy X is observed after oxidisation for 500 h at a high temperature, and this is attributed to the low Mn and Si contents in the alloys28. Meanwhile, the manufacturing parameters play an important role on microstructure and thus possible to influence the oxidation resistance. The processing defects induced by inappropriate parameters is suggested to have an adverse effect on the oxidation performance in LPBF GH3536 alloy, especially the micro-cracks defects can promote localized oxidation29. In contrast, another work on LPBF superalloy 718 revealed that there was a decrease in intergranular oxidation resistance because of the decreased content of special grain boundaries generated during the LPBF process when compared to the wrought samples30.

Despite a significant progress in elevating the oxidation performance at high temperature in superalloys manufactured using LPBF technology, the impact of microstructure on oxidation kinetics, the structure of products, and especially related mechanisms has not yet been comprehensively explored. In this study, we investigate the high-temperature isothermal oxidation behaviour of LPBF GH3536 superalloy. The influences of microstructure and its evolution on oxidation behaviour are clarified by a comparison with conventional wrought GH3536 through isothermal exposure tests at a high temperature of 950 °C. Short-term oxidation tests were conducted via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) for 6 h to reveal the effect of microstructure at an early stage.

Results

Characterisation of material microstructure

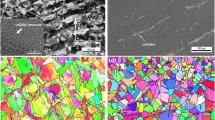

Figure 1(a) illustrates the metallurgical micrographs and microstructures of LPBF GH3536. A typical fish-scale melting pool is observed on the vertical plane parallel to the building direction. The depth and width of the molten pool are approximately 50–80 μm and 160–200 μm, respectively. The magnified observations shown in the white dash frames indicate that there is a specific microstructure of sub-grain cells. The ultrafine cellular structure has a cell size of around 0.5 μm with some granular precipitates distributed at the cellular boundaries. Figure 1(b) presents a comparison of the common equiaxial grains in the wrought sample. EBSD equipment is used for further analysis of the microstructure, including the grain-size distribution and crystal orientation (Fig. 2). The inverse-pole figure in Fig. 2(a) shows a weak preferential orientation of dendritic crystallites along the building direction in the LPBF GH3536 superalloy, compared with the randomly distributed crystalline orientation observed in wrought GH3536 (Fig. 2(b)). Kernel average misorientation (KAM) mapping, which is obtained based on the average misorientation between every point and its surrounding six points, is typically used to display the local residual strain distribution inside the grains. The wrought sample exhibits an obviously lower local strain concentration when compared with the LPBF sample (Fig. 2(c) and (d)). A weak texture intensity in the <001> direction is formed with a maximum intensity of 8.479 in the LPBF GH3536 compared with an intensity of 3.119 in the wrought sample (Fig. 2(e) and (f)), which conforms with the preferred growth direction of the columnar dendritic crystals along the building direction.

The TEM images shown in Fig. 3 illustrate the fine microstructures in LPBF and wrought GH3536 samples. A large number of cellular sub-grains with an average size of approximately 0.5 μm are characterised with some precipitates inside or along the subgrain boundaries (Fig. 3(a)). The magnified images of sub-grains and precipitates in the red-dashed frames show some detailed information (Fig. 3(b–d)). The cellular grain boundaries are composed of high-density dislocation tangling, corresponding to the high residual strain seen in KAM mapping. Uniformly distributed spherical precipitates with a size of approximately 50 nm are identified as (Cr, Mo)-rich precipitates via TEM-EDS measurement. These (Cr, Mo)-rich precipitates are formed in-situ during the manufacturing process. The trace oxygen retained in the raw powders and in the forming chamber even under Ar inert atmosphere protection during LPBF process are inevitable and not easy to completely remove, which will react with the Cr elements due to the high oxygen affinity. By contrast, the metallurgical structure of the wrought GH3536 samples is mainly characterised by regular-sized grains, micrometre-scale carbide precipitates, and a few annealing twins. The TEM-EDS chemical composition analysis reveals two types of carbides, a Mo-rich suborbicular carbide and a strip-shape carbide containing more Cr than Mo. The wrought sample has more carbide content than the LPBF samples, leading to an inhomogeneous local composition, such as Cr and Mo dilution near the grain boundaries.

Short-term oxidation behaviour

A short-term TGA test is conducted to understand the oxidation behaviour at the initial stage. The TGA diagrams (Fig. 4(a)) of both LPBF and wrought samples demonstrate a classic parabolic time dependence of the oxide film. The LPBF sample has more weight gains during early-stage exposure within 6 hours. According to the parabolic law, the oxidation rate constant is calculated by Eq. 1 (Fig. 4(b)), where \(\left( {\frac{{\Delta m}}{A}} \right)\) is the weight gain per unit area (mg.cm−2), t is the exposing time (h), and kp(t) is the instantaneous rate constant.

Though the oxidation rate of the LPBF sample is obviously higher than that of the wrought sample, the rate reaches the maximum value initially at around 1.5 h, and then begins to slow down gradually. In contrast, the oxidation rate in the wrought sample increases with exposure time, and no turning point is reached in the initial 6 h stage.

Figure 5 shows the plain-view surface morphology in the two types of samples after TGA testing. The LPBF sample is covered with a layer of uniform and dense oxide scale. In the wrought sample, some oxide particles are present, and they tend to accumulate on the grain boundary rather than form a film layer.

Cross-sectional samples are prepared in both the LPBF and wrought samples. The diversity in scale morphology and thickness between the two variants of samples are shown in Fig. 6. After 6 h oxidation at 950 °C in air, a protective and compact oxide film around 1.3 μm thick is preferentially formed on the surface of LPBF sample whereas there are only scattered large oxide particles formed on the surface of wrought sample.

Long-term isothermal oxidation behaviour

Long-term oxidation tests are conducted at 950 °C for 500 h to investigate the corrosion behaviour and products structure for an extended duration. The surface morphology, layer construction, and oxidation products are investigated using SEM, XRD, and EPMA for both the wrought and LPBF GH3536 samples.

Figure 7 displays the overall plan view of the surface morphology at low and high magnifications with specific locations marked as a, b, and c detected via EDS spot analysis. A notable difference in oxide scale is observed between the LPBF and wrought samples. In the wrought sample, a uniform and dense oxide scale is formed, with thicker products accumulated at grain boundaries when compared to grain interiors (Fig. 7(a, b)). EDS analysis identified the thicker products as (Cr, Fe, Ni, Mn)-rich oxides with spinel shapes and the thinner ones as mainly Cr-rich oxides (Table 1). As for the LPBF sample shown in Fig. 7(c, d), a uniform oxide scale is formed on the surface with grey scale, which likely indicates the ranking of the scale thickness and corrosion products. The oxide films are divided into three regions marked as a, b, and c according to the grey scale. EDS analysis of different regions reveals that the region with the deepest colour is mainly composed of a thicker Cr2O3 oxide layer, whereas the other two regions are almost bare, with a thinner layer thickness and low content of oxygen which may result from local exfoliation (Table 1).

The phase structures of the oxidation products are identified by XRD. The XRD patterns (Fig. 8) of wrought GH3536 indicate a spinel layer of (Fe, Ni, Mn) Cr2O4 and a film layer of Cr2O3. The main component of the scale is Cr2O3 with a minute spinel peak in the LPBF samples. The peak of matrix phase was detected in both wrought samples and LPBF samples, whereas the intensity of latter is higher.

Cross-sectional samples with Cu-plated protection are prepared and polished to a mirror finish for the scale-film measurement of wrought and LPBF GH3536 (Fig. 9). The oxide scale of the wrought sample is thicker with a better continuity and uniformity (Fig. 9(a, b)), corresponding to the denser coverage of oxidation products shown in Fig. 7. The magnified image in Fig. 9(b) presents the film structure and thickness measurement of the oxide film. The overall thickness is approximately 10 μm with a three-layered lamination, consisting of outer spinel particles, a middle compact film, and an inner loose layer. The oxide scale in the LPBF sample exhibits a thinner and more compact film with an average thickness of approximately 4 μm (Fig. 9(c, d)). This conforms well with the plan-view morphology shown in Fig. 7(c) and further explains the difference of phase structures of the oxidation products in XRD patterns. In the wrought sample, the oxide scale is thicker and the matrix phase is mainly derived from spallation. Compared with the wrought sample, the oxide scale formed in the LPBF sample is thinner, which enabled the matrix phase to be detected during the scanning process.

a SEM images of the cross-section of the wrought sample at low magnifications. b SEM images of the cross-section of the wrought sample at high magnifications. c SEM images of the cross-section of the LPBF sample at low magnifications. d SEM images of the cross-section of the LPBF sample at high magnifications.

The chemical composition and stoichiometry of the oxide scale are measured and quantified using the EPMA technique. The cross-section element distribution mappings confirm the presence of a three-layer lamination structure in the wrought sample (Fig. 10). A uniform oxide scale composed of Cr, Fe, Ni, and Mn is formed in the outermost surface with a dense Cr-rich middle layer and a loose (Fe, Cr, Ni) inner layer. Combining the cross-section chemical composition and plan-view morphology, it can be concluded that the oxide scale in wrought GH3536 is thick and is comprised of outer spinel particles and an inner compact protective film.

a The EPMA cross-sectional morphology of the wrought sample. b O element distribution of the scale formed on the wrought sample. c Cr element distribution of the scale formed on the wrought sample. d Ni element distribution of the scale formed on the wrought sample. e Fe element distribution of the scale formed on the wrought sample. f Mn element distribution of the scale formed on the wrought sample.

The EPMA maps in Fig. 11 present the morphology and element distribution of the cross-sections in the LPBF samples. The oxide scales are dense and continuous, with a slightly localised non-uniformity which may result from peeling during sample preparation. Compared with the wrought samples, the LPBF GH3536 sample may undergo a comparable oxidation process because of the oxide scale structure and stratification. A three-layered oxide film can also be observed in the local oxidisation areas, but with a smaller thickness of approximately 7 μm. Another difference is that the outer spinel layer possesses a lower Mn content, which is attributed to the higher Mn content in the wrought sample28.

a The EPMA cross-sectional morphology of the LPBF sample. b O element distribution of the scale formed on the LPBF sample. c Cr element distribution of the scale formed on the LPBF sample. d Ni element distribution of the scale formed on the LPBF sample. e Fe element distribution of the scale formed on the LPBF sample. f Mn element distribution of the scale formed on the LPBF sample.

Discussion

During the LPBF manufacturing process, raw alloy powders are melted layer-by-layer and then solidified at an ultrafast cooling rate. Therefore, this process forms a more hierarchical microstructure when compared to a conventionally manufactured superalloy11,31. In addition to the general fine crystalline structure, the rapid cooling rate and steep thermal gradient result in the formation of a nanoscale cellular sub-structure surrounded by high-density dislocations and a substantial compressive residual stress in the component’s interior32,33. Formation of nanoscale Cr-oxide inclusions can also be observed in LPBF samples by consuming the residual oxygen in the processing environment and raw material powders34. The oxide inclusions are presumed to consume Cr to some extent but do not cause a significant localisation of Cr dilution because they are relatively uniformly distributed. Large carbide particles, which normally lead to localised Cr depletion, are rarely formed in LPBF GH3536 because of the rapid solidification rate (typically ∼107 K/s). In contrast, the nucleation and diffusion growth of large Cr- and Mo-rich carbides have sufficient time to form because of the relatively low solidification rate of 273–373 K/s in the wrought counterpart35. The strong <001> texture could be attributed to preferential grain growth along the temperature-gradient direction during extremely fast solidification in the LPBF process.

The specific microstructure of the LPBF superalloy plays an important role in its oxidation performance. Considering the microstructure evolution of the matrix during high-temperature exposure, the oxidation behaviour is investigated via short- and long-term tests to comprehensively understand the specific effects on LPBF GH3536 in this study.

The main exposure process of a Ni-based superalloy in a high-temperature dry-air environment can be divided into two stages. First, the microstructure undergoes external oxidation, wherein the oxidisable elements (e.g., Cr, Fe, and Ni) at the air–surface interface react with oxygen from the environment to form a thin oxide film through the following reactions:

In the second stage, oxidation continues through reactions at the interface between the alloy elements and oxygen diffusing from the matrix and atmosphere, respectively. The oxidation rate is mainly controlled by the Cr element diffusion process, which normally occurs through lattice and grain-boundary diffusions. In the LPBF GH3536 samples, the impact of the hierarchical structure, especially the cell boundaries that are composed of high-density dislocations, on the element diffusion process should be considered.

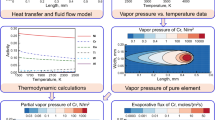

To further clarify the role of cell boundaries on element diffusion and then on oxidation behaviour, especially in the very early stage, molecular dynamics (MD) is used to simulate the diffusion paths of Cr atoms under different local environments (Fig. 12), that is, bulk, screw/edge/60°-mixed 1/2 <110> dislocations, and along the grain boundary, based on the activation-relaxation technique (ART)36,37,38,39. The interatomic potentials used in the present calculations are based on the potential function developed by G. Bonny et al.40,41. The entire diffusion process is comprised of the formation of vacancies and the diffusion of Cr atoms, in which the total diffusion activation energy is controlled by Eq. (4):

where Ef is the vacancy formation energy and Em is the diffusion barrier of Cr atom.

The total diffusion activation energy of Cr under various conditions is shown in Fig. 13(a–e), wherein each point corresponds to a different diffusion path. The initial and final positions of Cr atoms during each diffusion processes (Fig. 12(a–e)) are shown in Fig. 12(f).

According to the results shown in Fig. 13, the Eact of Cr dislocation along the dislocations is between that of the grain boundary and bulk. In a real LPBF sample, the diffusion process is affected by the massive number of dislocations that have accumulated on the cellular boundaries, which would provide a lower total diffusion activation energy than that of a single dislocation. Therefore, cellular boundaries play a crucial role in the formation of an oxide film by promoting the diffusion rate40. The oxidation rate constant of the LPBF samples increases dramatically at the beginning and then drops rapidly when the protective oxide film forms on the surface.

Additionally, the oxide film thickness formed in the early 6 h stage in LPBF sample is estimated assuming Cr2O3 as the main component of the oxide film. The calculated thickness is 1.29 μm, which is found dividing a mass gain per unit area of 0.67293 mg^cm−2 using a Cr2O3 density of 5.21 g^cm−3, which corresponds well with the thickness measurement of 1.3 μm in the cross-section images (Fig. 6(b)). This approximate calculation demonstrates that a protective Cr2O3 scale forms and is stable and almost without spallation at the early stage in LPBF samples. The large amount of cellular grain boundaries and high-density dislocations act as fast diffusion paths to accelerate the nucleation of oxides and the quick formation of a dense film. In contrast, dispersed oxide particles are preferentially formed at a grain boundary while no uniform film is formed in the wrought sample. With a longer exposure time, oxidation products spread from the grain boundary to the grain interior and gradually form an oxide film.

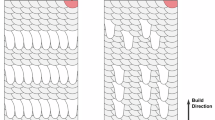

Notably, although the ultrafine subgrain structure has a significant impact on oxidation behaviour by acting as fast diffusing paths, its thermal stability during high-temperature exposure should be considered. The cellular structure in LPBF fabricated samples is reported to completely disappear after 6 h at 1000 °C42. Thomas et al. also reported that the cellular structure exhibits a high thermal stability and the cell walls disappear after dwelling for 2 h at temperatures up to 1000 °C43. From this perspective, the stability of the sub-grain structure is important for the formation of a dense and protective oxide film at the early stage. To confirm this view, the metallurgical structure of the LPBF sample after the TGA test is observed under SEM (Fig. 14). The cells remain visible but exhibit a slight coarsening after a 6 h exposure. The results confirm the hypothesis that the special cellular structure in LPBF samples plays an important role in the oxidation process. The oxide film that initially forms in the LPBF sample can quickly advance the oxidation process to a stable stage, which effectively impedes further oxidation.

As for long-term oxidation with increasing exposure time, the alloy elements continuously diffuse from the matrix through the protective layer to react with O at the film-environment interface. The dense and protective oxide film that forms in the early stage in the LPBF samples steadily decreases the oxidation rate and leads to thinner overall scales, whereas the oxidation rate increases during an extended exposure time until a protective scale forms in the wrought samples. A thicker oxide scale is formed until the Cr concentration decreases below the critical concentration, leading to a Cr-depleted zone underneath the surface.

An outer spinel layer containing Fe, Ni, and Mn is formed in the wrought sample, but few spinel particles are detected in the LPBF sample, which is attributed to the compactness and improved protectiveness of the oxide film. Spinel particles are formed through reactions between metal elements such as Mn, Fe, and Ni with Cr2O3 oxides. In the wrought sample, the formation of Mn-rich spinels is attributed to the higher Mn content in the matrix. First, the elements must diffuse across the compact Cr2O3 film and then generate spinels through the reactions. Defects in the Cr2O3 scale film and grain boundaries act as fast diffusion paths, likely leading to the accumulation of spinel oxide products at the grain boundaries in the wrought sample. Furthermore, the large carbides that precipitate along the grain boundary in the wrought sample lead to depletion of Cr, resulting in the accumulation of spinels on the grain boundaries.

Compared with the wrought sample, the uniformly distributed small-size Cr-rich precipitates formed along the cellular boundaries in LPBF sample could avoid local segregation of Cr. The nanoscale oxide inclusions generated during the LPBF process are also proven to enhance corrosion resistance by facilitating a homogeneous element distribution that prevents local Cr depletion28. Hence, the homogenously distribution of nanoscale Cr-rich oxide inclusions due to the ultra-fine cellular structure help improving the oxidation performance by localising Cr into themselves, thus avoiding the formation of dilution zones in the LPBF sample.

In summary, cellular sub-grains are the most significant influencing factor because they provide fast diffusion paths and nucleation sites to form a dense and protective film in early-stage oxidisation in the LPBF GH3536 alloy. Figure 15 illustrates a schematic of the specific oxidation mechanisms of the wrought and LPBF samples. In the LPBF sample, the metal elements, especially Cr atoms, diffuse more easily than lattice diffusion according to the activation energy calculation. The high-density accumulation of dislocations on the cellular boundaries provides a large fraction of fast diffusion path that accelerate the formation of a protective film in the very early stage. Consequently, LPBF GH3536 exhibits a better oxidation resistance than wrought GH3536.

The microstructure and high-temperature oxidation characteristics of the LPBF GH3536 superalloy are investigated. The main conclusions are summarised below:

A microstructure with a hierarchical pattern is identified in the LPBF samples. The sub-grain structure and nanoscale oxide inclusions strongly affect the oxidation resistance.

A protective and compact oxide film quickly forms on the surface of the LPBF sample at a very early stage, whereas large and scattered oxide particles form on the wrought sample.

After a 6 h exposure, cellular structures are still visible in the LPBF sample, which contributes to the rapid formation of a protective oxide film at a very early stage. The difference in short-term oxidation between the LPBF and wrought samples results in a remarkable impact on long-term oxidation.

The oxide scale formed on the LPBF sample is more protective than that of the wrought sample.

Methods

Materials and selective laser melting processing

The pre-alloyed atomised GH3536 powder used for the LPBF process was provided by the Institute of Metal Research (IMR), Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang, China. Table 2 summarises the chemical composition of the powder, and Fig. 16(a), (b) illustrates the particle size distributions and morphologies.

Cubic samples were manufactured using an EOS M280 LPBF system (Germany) equipped with a 400-W Yb:YAG fibre laser. Optimised processing parameters with a laser power of 225 W, scanning speed of 960 mm/s, and hatch distance of 0.11 mm were applied to obtain a good printing quality with a low amount of manufacturing defects. LPBF samples with size of around 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm were built and then cut from the substrate for subsequent analysis, as shown in Fig. 16(c). Conventional wrought samples were prepared as well for comparison. The chemical composition of the wrought GH3536 is provided in Table 3.

Material characterisation

The samples were abraded with SiC emery paper from 200 to 3,000 grits and polished with a diamond paste spray (3, 1.5, and 0.25 μm) to a mirror finish. The microstructures of the wrought and as-fabricated LPBF samples were etched in aqua regia (15 ml HCl and 5 ml HNO3). LEICA DMi8A was used to characterise the optical topography of the LPBF and wrought samples. Microstructure observations of LPBF samples were assessed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Quanta FEG450) to reveal the microstructure. The grain size and distribution of the wrought and LPBF samples were observed using electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) on a Hitachi SEM device equipped with an EDAX EBSD detector. The microstructure observations were carried out using an FEI Tecnai G2F20 transmission electron microscopy (TEM) device equipped with a field emission gun operating at 200 kV. Conventional bright fields were obtained to analyse the microstructures of the wrought and as-fabricated samples.

High-temperature oxidation experiments

Short-term and long-term exposure experiments were conducted in an air environment for both LPBF and wrought GH3536 alloy at 950 °C. The samples were subjected to TGA tests for 6 h and isothermal exposure tests for 500 h, respectively. To eliminate the effect of surface roughness and better observe the cross-sectional morphology, samples were abraded and polished to a mirror finish before oxidation. After exposure, all samples were cooled to room temperature and carefully taken out for examination.

TGA tests were performed by a Setaram high-temperature TGA analyser (Model: Setsys Evo TG) to measure the real-time changes in mass gains. X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies were conducted with a Cu–Ka source (k = 1.54 Å) in a scanning range of 20–120° at a step size of 0.02° (Make & model: BRUKER – D8 Advance) to characterise the phase composition of the oxidation scale after exposure. The oxidation morphology after isothermal exposure was assessed by SEM (Quanta FEG450) equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). The EDS measurement was conducted at least 3 times for each point and selected the average value as the final result to ensure the accuracy. The samples were then Cu-electroplated to produce a protective plating for cross-sectional observation and oxide-scale measurements. The scale thickness, chemical composition, and stratification of oxide films were assessed by SEM and electron probe microanalysis (EPMA, Shimadzu EPMA-1720).

Data availability

The data used that support the findings of this study are available upon request to Dr Juan Hou. (hou18217727686@163.com).

References

Kim, W. G., Yin, S. N., Kim, Y. W. & Chang, J. H. Creep characterization of a Ni-based Hastelloy-X alloy by using theta projection method. Eng. Fract. Mech. 75, 4985–4995 (2008).

Inc. Haynes International, Hastelloy X alloy (product brochure) Information http://www.haynes.ch, Ch. 16 (1997).

Aghaie-Khafri, M. & Golarzi, N. Forming behavior and workability of Hastelloy X superalloy during hot deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 486, 641–647 (2008).

Akande, I. G., Oluwole, O. O., Fayomi, O. S. I. & Odunlami, O. A. Overview of mechanical, microstructural, oxidation properties and high-temperature applications of superalloys. Mater. Today Proc. 43, 2222–2231 (2021).

Kong, D., Dong, C., Ni, X. & Li X. Corrosion of metallic materials fabricated by selective laser melting, NPJ Mater. Degrad. 3, 24 (2019).

Pillai, R., Dryepondt, S. & Pint, B. A. High temperature oxidation lifetime modeling of thin-walled components. Proc. ASME Turbo Expo. 6, 10 (2019).

Hayashi, S., Matsukawa, C., Yakuwa, H. & Kishikawa, T. Cyclic carburisation-oxidation behavior of Hastelloy-X at 1000 °C. Corros. Rev. 36, 75–85 (2018).

Olivares, R. I., Stein, W. & Marvig, P. Thermogravimetric study of oxidation-resistant alloys for high-temperature solar receivers. JOM 65, 1660–1669 (2013).

Angerman, C. L. Long-term oxidation of superalloys. Oxid. Met. 5, 149–167 (1972).

England, D. M. & Virkar, A. V. Oxidation kinetics of some nickel‐based superalloy foils and electronic resistance of the oxide scale formed in air Part I. J. Electrochem. Soc. 146, 3196–3202 (1999).

Liu, Z. et al. Additive manufacturing of metals: Microstructure evolution and multistage control. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 100, 224–236 (2022).

Zhang, J., Song, B., Wei, Q., Bourell, D. & Shi, Y. A review of selective laser melting of aluminum alloys: Processing, microstructure, property and developing trends. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 35, 270–284 (2019).

Liverani, E., Toschi, S., Ceschini, L. & Fortunato, A. Effect of selective laser melting (SLM) process parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L austenitic stainless steel. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 249, 255–263 (2017).

Singla, A. K. et al. Selective laser melting of Ti6Al4V alloy: Process parameters, defects and post-treatments. J. Manuf. Process. 64, 161–187 (2021).

Olakanmi, E. O., Cochrane, R. F. & Dalgarno, K. W. A review on selective laser sintering/melting (SLS/SLM) of aluminium alloy powders: Processing, microstructure, and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 74, 401–477 (2015).

Shaji Karapuzha, A., Fraser, D., Zhu, Y., Wu, X. & Huang, A. Effect of solution heat treatment and hot isostatic pressing on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Hastelloy X manufactured by electron beam powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 98, 99–117 (2022).

Hou, J., Chen, W., Chen, Z., Zhang, K. & Huang, A. Tensile properties and mechanical anisotropy of selective laser melted 304L stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 48, 63–71 (2020).

Chao, Q. et al. On the enhanced corrosion resistance of a selective laser melted austenitic stainless steel. Scr. Mater. 141, 94–98 (2017).

Sande, G. et al. On the corrosion and metastable pitting characteristics of 316L stainless steel produced by selective laser melting. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, C250–C257 (2017).

Zhang, D. et al. Additive manufacturing of ultrafine-grained high-strength titanium alloys. Nature 576, 91–95 (2019).

Wang, F. Mechanical property study on rapid additive layer manufacture Hastelloy® X alloy by selective laser melting technology. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 58, 545–551 (2012).

Rao, J. H., Zhang, Y., Huang, A., Wu, X. & Zhang, K. Improving fatigue performances of selective laser melted Al-7Si-0.6Mg alloy via defects control. Int. J. Fatigue 129, 105215 (2019).

Zhu, L., Wang, S., Pan, H., Yuan, C. & Chen, X. Research on remanufacturing strategy for 45 steel gear using H13 steel powder based on laser cladding technology. J. Manuf. Processs. 49, 344–354 (2020).

Zhu, L. et al. Recent research and development status of laser cladding: A review. Opt. Laser Technol. 138, 106915 (2021).

Tomus, D. et al. Controlling the microstructure of Hastelloy-X components manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Phys. Procedia 41, 823–827 (2013).

Gokcekaya, O. et al. Crystallographic orientation control of pure chromium via laser powder bed fusion and improved high temperature oxidation resistance. Addit. Manuf. 36, 101624 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Improvement in the oxidation resistance of Nb-Si based alloy by selective laser melting. Corros. Sci. 127, 260–269 (2017).

Romedenne, M., Pillai, R., Kirka, M. & Dryepondt, S. High temperature air oxidation behavior of Hastelloy X processed by electron beam melting (EBM) and selective laser melting (SLM). Corros. Sci. 171, 108647 (2020).

Min, S. et al. Influence of Defects on High-Temperature Oxidation Performance of Gh3536 Superalloys Fabricated by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 3, 100064 (2022).

Sanviemvongsak, T., Monceau, D., Desgranges, C. & Macquaire, B. Intergranular oxidation of Ni-base alloy 718 with a focus on additive manufacturing. Corros. Sci. 170, 108684 (2020).

Kong, D. et al. Anisotropic response in mechanical and corrosion properties of hastelloy X fabricated by selective laser melting. Constr. Build. Mater. 221, 720–729 (2019).

Pokharel, R. et al. Signatures of the unique microstructure of additively manufactured steel observed via diffraction. Scr. Mater. 155, 16–20 (2018).

Pourbabak, S. et al. Microscopic investigation of as built and hot isostatic pressed Hastelloy X processed by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Charact. 153, 366–371 (2019).

Hou, J. et al. Helium bubble nucleation in laser powder bed fusion processed 304L stainless steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 542, 152443 (2020).

Zhao, J. C., Larsen, M. & Ravikumar, V. Phase precipitation and time-temperature-transformation diagram of Hastelloy X. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 293, 112–119 (2000).

Bataillou, L., Desgranges, C., Martinelli, L. & Monceau, D. Modelling of the effect of grain boundary diffusion on the oxidation of Ni-Cr alloys at high temperature. Corros. Sci. 136, 148–160 (2018).

Barkema, G. T. & Mousseau, N. Event-Based Relaxation of Continuous Disordered Systems. Physrevlett 77, 4358–4361 (1996).

Wang, H., Rodney, D., Xu, D., Yang, R. & Veyssière, P. Pentavacancy as the key nucleus for vacancy clustering in aluminium. Phys. Rev. B - Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 84, 1–5 (2011).

Wang, H., Xu, D., Yang, R. & Veyssière, P. The transformation of edge dislocation dipoles in aluminium. Acta Mater. 56, 4608–4620 (2008).

Bonny, G., Castin, N. & Terentyev, D. Interatomic potential for studying ageing under irradiation in stainless steels: The FeNiCr model alloy. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 21, 085004 (2013).

Wang, K. et al. High-temperature oxidation behaviour of high chromium superalloys additively manufactured by conventional or extreme high-speed laser metal deposition. Corros. Sci. 176, 1–13 (2020).

Salman, O. O., Gammer, C., Chaubey, A. K., Eckert, J. & Scudino, S. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of 316L steel synthesized by selective laser melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 748, 205–212 (2019).

Voisin, T. et al. New insights on cellular structures strengthening mechanisms and thermal stability of an austenitic stainless steel fabricated by laser powder-bed-fusion. Acta Mater. 203, 116476 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52073176), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB3702503), Major Special Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Province (202002AB080001-3), Shanghai Engineering Research Center of High-Performance Medical Device Materials (No. 20DZ2255500), and the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. completed the experiment and the writing of the manuscript. J.H., K.Z. checked and improved the manuscript. H.L. and H.Z. assisted with the experimental work. Thanks for the powder raw materials provided by the Institute of Metal Research and the experimental equipment provided by the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Min, S., Liu, H., Yang, M. et al. High-temperature oxidation performance of Ni-based GH3536 superalloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. npj Mater Degrad 6, 66 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-022-00276-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-022-00276-8

This article is cited by

-

Additive Manufacturing of Hastelloy X Ni-Based Alloy: Current Trends, Challenges, and Perspectives

Metals and Materials International (2025)

-

A Comparative Study of Laser Additive Manufacturing of Ni-Base Superalloy and Low-Alloy High-Strength Steel

JOM (2024)