Abstract

This review examines machine learning approaches for predicting pipeline residual strength, which is crucial for assessing operational lifespan and safety in industrial applications. We analyze various machine learning models, data preprocessing methods, and evaluation metrics used in existing research. The study highlights how data characteristics and model selection influence prediction accuracy, providing practitioners with guidelines for model implementation, while discussing current challenges and future research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pipelines are pivotal in the transportation system, serving as the primary means of conveying oil and gas1,2,3. As the operational time of pipelines increases, they inevitably suffer from corrosion4,5,6,7,8. Corrosion can significantly diminish the structural integrity of pipelines, ultimately resulting in the possibility of pipeline leakage or fracture9,10,11. The failure of oil and gas steel pipelines can result in catastrophic economic and environmental consequences12,13,14,15. Figure 1 shows oil and gas pipeline incidents reported by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) of the U.S. Department of Transportation16. The residual strength of a pipeline refers to its maximum capacity to withstand loads17,18. Considering the severe consequences of failure, accurately predicting the residual strength of corroded pipelines holds significant importance.

Predicting residual strength in pipelines typically involves three primary methods: empirical formula, finite element analysis, and machine learning. Introduced in the late 1960s, the NG-18 formula was instrumental in calculating pipeline residual strength and served as a foundation for the development of later empirical formulas19. The ASME introduced the ASME B31G evaluation criteria, which were established through a combination of theoretical research and extensive burst test20,21,22. Formulated in the 1980s, the formula relies on a limited amount of corrosion data, which reduces its versatility. Due to the conservatism of ASME B31G, which often leads to unnecessary pipeline replacements, Kiefner proposed the ‘0.85dl’ method in the PRCI report23. DNV and BG Technology jointly developed DNV RPF-101 by integrating data from full-scale burst tests and 3D nonlinear finite element simulations. This model accounts for the impact of external loads on the pipeline’s load-bearing capacity, and extensive empirical research has validated the DNV formula as one of the most effective methods for predicting pipeline residual strength24. However, this method is inapplicable to pipelines with X80 or higher grades. Liu et al. extended this formula by introducing a modified defect depth to account for the impact of defect quantity on the results24. The Battelle Laboratory in the United States developed the renowned PCORRC method, based on the theory of plastic collapse failure, for calculating residual strength of medium to high-toughness corroded pipelines25. Due to the simplicity of these formulas, they have been widely applied in engineering practice26. These formulas show considerable evaluation errors and a high degree of conservatism. Although greater conservatism enhances pipeline operational safety, it may reduce operational efficiency.

Due to the significant errors in empirical formulas, more researchers in recent years have adopted finite element analysis to evaluate the residual strength of corroded pipelines. In the early years, limited computational power led researchers to use 2D finite element models to calculate pipeline residual strength27,28. The use of 2D finite element analysis models cannot account for defect shapes and geometries, which substantially reduces prediction accuracy. With advancements in computational power, more researchers have shifted to using 3D finite element modeling to study pipeline residual strength. Zhang et al. incorporated a safety factor into the pipeline assessment process and employed 3D finite element analysis to model the pipeline under triple failure pressure29. Phan et al. utilized the finite element method to calculate and analyze the burst pressure of corroded pipelines under different conditions30. Ma et al. developed a novel finite element-based predictive formula to estimate the failure pressure of high-strength pipelines, demonstrating strong agreement with experimental data31. However, this approach does not consider defect width and is not applicable for evaluating low-strength pipelines. Huang et al. proposed a finite element-based model to calculate the failure pressure of pipelines with dent corrosion defects. The results indicate that dents reduce the failure pressure32. Qin et al. developed a model that considers mechanical-electrochemical (ME) interactions to predict the variation of failure pressure over time and investigated the effects of parameters such as internal pressure, axial tensile stress, and initial defect length33. While FEA has provided satisfactory results, it is essential to consider the specific characteristics of real-world pipelines and various failure criteria. Achieving high accuracy requires a large number of meshes, which significantly increases computational load and time. Additionally, changes in defect parameters require model reconstruction, making this method inconvenient and inefficient.

With advancements in artificial intelligence technology, numerous researchers have integrated machine learning methods into the prediction of pipeline residual strength. The general framework for predicting residual strength of pipelines using machine learning is shown in Fig. 2. Unlike empirical formulas, machine learning methods can learn the complex relationship between corrosion influencing factors and residual strength from abundant observational data. The research paradigm of residual strength assessment has shifted from the “reasoning” and “knowledge” stages to the current “learning” stage. Ma et al. developed an ensemble learning model using existing empirical formulas to optimize LightGBM through TPE, aimed at studying the impact of varying pipeline and corrosion conditions on pipeline burst pressure34. Using ensemble learning to optimize empirical formulas effectively addresses the issue of overly conservative empirical formulas. The presence of empirical formulas can also help mitigate the poor interpretability of machine learning models. Ma et al. incorporated empirical formulas into the neural network training process, leveraging the prior knowledge from these formulas to guide the training, thereby proposing a theory-guided machine learning model35. Lu et al. proposed a novel theoretical formula, specifically designed for multipoint corroded pipelines, by modifying the existing pipeline corrosion criterion. In addition, a residual strength prediction model for multipoint corroded pipelines was developed using RBFNN and data from existing literature machine learning models6. Lu et al. combined PCA and SVM techniques, optimized SVM parameters through multi-objective optimization methods, and introduced a novel pipeline residual strength prediction framework, achieving higher accuracy and stability18. Wang and Lu integrated the prediction outputs of multiple individual models through the Stacking model, establishing a residual strength prediction model with higher accuracy and generalization performance17.

Machine learning has become a research hotspot in the field of residual strength prediction for oil and gas pipelines. Nevertheless, the field currently lacks a comprehensive systematic review. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive review of the current development and application scope of machine learning technologies in this field. To address this issue, this paper provides a comprehensive review of the application of machine learning techniques in predicting the residual strength of oil and gas pipelines. The review aims to highlight the most widely used techniques, emphasizing the essential machine learning approaches for residual strength prediction. Covering topics from raw data acquisition and preprocessing techniques to commonly used prediction models and their performance evaluation. This review emphasizes the limitations of current machine learning research in predicting the residual strength of corroded oil and gas pipelines, while providing comprehensive and innovative perspectives on future advancements in the field.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The “Research methodology” section introduces the research methods used in this study. The “Data collection and preprocessing” section reviews methods for collecting and processing data for machine learning. The “Machine learning models” section summarizes commonly used machine learning models, including single and hybrid models. The “Evaluation metrics” section provides an overview of the indicators that have been used to evaluate model performance in existing studies. The “Discussion” section discusses the impact of data size and division ratio, and machine learning model type on model performance, and summarizes the frequency of use of each evaluation metric. The “Challenges and perspectives” section identifies the challenges in current research and outlines directions for future studies. The meanings of the abbreviations in the text are found in Table 1.

Research methodology

The methodology of previous research reviews provides valuable guidance for this research14,36,37. The methodology used in this research is the systematic literature review (SLR)14 and consists of three essential stages: databases and keywords, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and analysis of publications.

Databases and keywords

To conduct a detailed search for articles related to the application of machine learning in residual strength prediction of oil and gas pipelines, three databases were used in this research: Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect. By summarizing the keywords in the related articles, the search was performed using the following keywords: “pipeline” AND (“residual strength” OR “burst pressure” OR “failure pressure” OR “remaining strength”) AND (“machine learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “neural network”). The scope of the search was conference papers and journals published between 2000 and 2024.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

After the first search, the retrieved articles were organized based on PRISMA criteria38. The inclusion criteria include that the articles are peer-reviewed and in English, the articles are based on machine learning models, and the articles predict the residual strength of oil and gas pipelines. Articles that do not meet the above criteria will be excluded.

Analysis of publications

Through a detailed analysis of the retrieved articles, 36 papers closely aligned with the research content were manually selected. Figure 3 shows the yearly distribution of the research articles. As can be seen from the figure, more and more researchers have started to work in this field in the last few years. It also shows that the field is evolving and that it makes sense to engage in relevant research.

Data collection and preprocessing

Data parameters

Data plays a crucial role in machine learning, serving as the foundation for developing machine intelligence. Similar to the human learning and decision-making process, machine learning methods require large amounts of data to discover patterns, extract features, and generate accurate predictions. The quality, diversity, and comprehensiveness of data greatly influence the model’s performance and its ability to generalize. In machine learning, approximately 80% of the modeling time is spent on data-related tasks39. Therefore, data collection, cleansing, and processing are crucial steps for ensuring the success of machine learning. Table 2 summarizes the data parameters used in previous studies to predict pipeline residual strength using machine learning methods. These parameters are categorized into three main groups: Pipe size parameters, Material parameters, and Defect parameters. When investigating the residual strength of a pipeline under specific conditions, specific external condition parameters are required.

Data collection methods

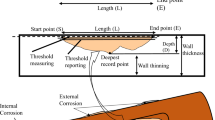

Full-scale burst test

The corroded pipeline full-scale burst test is the most important experimental method for evaluating the structural safety of pipelines. This test considers key parameters such as the material, pipe size, and corrosion of the pipeline to ensure the reliability and applicability of the test results. By utilizing advanced equipment such as high-speed cameras and pressure sensors to record and analyze critical data from the bursting process, researchers can gain insight into the pipeline’s load-bearing capacity, damage patterns, and causes of failure, as shown in Fig. 4. This testing methodology provides valuable reference and decision support for pipeline design and maintenance, while also offering substantial data and a foundation for pipeline safety management and risk assessment.

Full-scale burst test data plays a crucial role in predicting pipeline residual strength. On one hand, it directly supports the training and validation of models. On the other hand, it serves to verify the accuracy of models developed using finite element methods and other methods. To investigate the behavior of pipelines with corrosion defects, Benjamin et al. conducted burst tests on nine tubular samples, each featuring a single simulated external corrosion defect40. The experimentally measured burst pressures were compared and analyzed against the calculated results from empirical formulas, revealing that traditional empirical formulas tend to be overly conservative in estimating burst pressure. Benjamin et al. conducted full-scale burst tests on seven pipelines with corrosion defects and compared the results with six empirical formulas41. However, the availability of such data in open literature remains limited. On the one hand, due to the complexity and risks of testing, it is necessary to strictly comply with relevant safety standards and regulations under the guidance and supervision of professionals. On the other hand, conducting full-scale burst tests on corroded pipeline samples requires substantial time and financial resources. Machine learning requires a large amount of data, and insufficient data prevents the model from capturing nonlinear relationships in the data, which significantly impacts its performance.

Finite element model

Directly obtaining pipeline burst pressure data through burst tests is both inconvenient and costly. In such case, the finite element method serves as a crucial approach for obtaining pipeline burst pressure data. The finite element model simulates the mechanical behavior of pipelines under varying pressures by defining the geometric model, material properties, and operational boundary conditions. The accuracy of the model can be verified by comparing the finite element model with the real pipeline burst test data, facilitating the simulation of rupture pressure under different working conditions. Vijaya Kumar et al. generated data using a finite element model and developed an ANN model to predict the residual strength of corroded pipelines. The results demonstrated significant accuracy42. Zhang et al. obtained a burst pressure dataset through finite element analysis and utilized it to train neural networks for predicting pipeline failure pressure29.

While finite element models effectively generate burst pressure datasets, they face notable limitations in practical applications. Assumptions in the modeling process, material parameter determination, selection of ontological models, meshing strategies, and model complexity can influence the results. Moreover, finite element models require high-performance computing resources, and obtaining large amounts of data incurs significant time and financial costs. Therefore, these factors need to be carefully considered when using a finite element model to obtain pipeline burst pressure data and combined with other reliable information and methods for comprehensive evaluation and analysis.

Data generation model

Pipeline burst tests are time-consuming and costly, while finite element models have limited applicability to various pipeline configurations. Literature research indicates that many researchers employ data generation models to create previously unavailable datasets43,44. In recent years, GAN models have emerged as a new approach for generating synthetic data45,46,47,48,49,50. Figure 5 shows the basic framework of GAN. GAN is a deep neural network model that learns the data distribution from user-provided training data and generates synthetic data based on this learned distribution. Jain et al. utilized a GAN architecture to generate synthetic data representing six types of pipeline surface defects51. Xu et al. employed GAN to synthesize fault data, which was then used to evaluate and classify pipeline conditions, aiming to prevent leaks52. In the area of corroded pipeline burst pressure research, He and Zhou utilized 258 real burst pressure data collected from the literature to train a Table GAN model for generating a dataset of pipeline burst test pressures53. The generated database was used to train RF and DT models for predicting pipeline residual strength.

Compared to full-scale pipeline burst tests and finite element methods, GAN significantly reduces experimental and computational costs, enabling the rapid generation of large-scale datasets without additional expenses. However, as a machine learning model, the effectiveness of GANs also depends on the availability of extensive and reliable residual strength datasets for corroded pipelines.

Data processing

Employing appropriate data preprocessing methods is crucial for ensuring reliable and accurate research outcomes. Many researchers have applied standard methods or developed specific methods for data processing as it directly affects the prediction results and their accuracy and reliability. The main work of data processing is the processing of features, which consists of two main steps: feature engineering and normalization.

Feature engineering

An excess or deficiency of model features has the potential to diminish prediction accuracy, and the inclusion of redundant or repetitive features can likewise impact computational speed. Feature engineering enables identifying the most important features for the model, reducing feature count, lowering computational complexity, and improving both performance and interpretability14. The common feature engineering methods include feature selection and feature transform. Feature selection is primarily used to identify and rank the most relevant features in a model. The Pearson correlation coefficient is the most commonly used feature selection method. And it can be calculated using the Eq. (1)54:

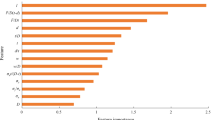

where \({x}_{i}\) is the feature value; \({y}_{i}\) is the label value. The larger the absolute value of \({p}_{c}\), the higher the correlation between the two factors55. Ma et al. used Pearson correlation coefficient to study the correlation of 14 features in the feature space and ranked the correlation of the features from small to large34. Ma et al. applied Pearson correlation analysis to select the three most relevant features out of eight for machine learning modeling to predict the residual strength of corroded oil and gas pipelines35.

Unlike feature selection, feature transform maps the original features to a lower-dimensional space to achieve feature dimensionality reduction. Dimensionality reduction minimizes data dimensions while retaining its essential information, with PCA being a widely adopted method for this purpose56,57. PCA maps high-dimensional data to a lower-dimensional subspace while maximizing the variance of the data. The principal components’ ability to explain the variance in the original data is represented by Eq. (2)58:

where \({g}_{i}\) denotes the explained variance of principal component \(i\); \(m\) denotes the number of principal components; \({\lambda }_{i}\) denotes the feature value of the principal component.

Lu et al. utilized PCA to reduce eight features from the raw pipeline burst pressure data and ranked the contribution of each parameter to burst pressure in descending order. The results show that the top seven features account for 99.235% of the contribution to burst pressure. These parameters were selected as input variables to reduce the model’s complexity18. Phan and Duong combined PCA with ANFIS to predict pipeline burst pressure, and the ANFIS-PCA model outperformed existing models, achieving a determination coefficient of 0.9919 and reducing the RMSE to 0.9883 MPa59.

In recent years, several manifold learning algorithms have been developed for data dimensionality reduction, including ISOMAP60, LLE, and KPCA61. Li et al. utilized LLE to reduce the dimensionality of submarine pipeline corrosion data and then employed the preprocessed data to train a BRANN model for predicting the residual strength of underwater pipelines with dual corrosion defects61. The LLE-processed data and KCPA-processed data were separately fed into the BRANN for comparison. The BRANN model trained with raw data alone exhibited the lowest predictive performance, highlighting the importance of data dimensionality reduction.

Normalization

Due to the different data dimensions of each parameter, normalization helps ensure the consistency of scales between different features and variables, speeding up the training process, and reducing the model’s sensitivity to specific features. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. (3)62.

where \({z}_{n}\) is the normalized data, range from 0 to 1; \({z}_{i}\) is the original data; \({z}_{\max }\) is the maximum original data; \({z}_{\min }\) is the minimum original data.

Data division

Since the accuracy of predictions cannot be predetermined, validation is usually performed using established datasets. The raw data needs to be divided into a training set, a validation set, and a test set before model training. The training set is used to train the model, the validation set is used to tune the model’s hyperparameters and for performance evaluation, and the test set is used for the final evaluation of the model’s performance. In this paper, the data sizes and test set ratios of the 30 literature collected are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3 indicates that during the modeling process for predicting the residual strength of pipelines, the available data is significantly limited. Dividing the dataset into three subsets enables an accurate evaluation of the model’s generalization ability and mitigates overfitting. In scenarios with limited data, the dataset is often divided into a training set and a test set, and K-fold cross-validation is used to optimize the model on the training set. This approach provides a more stable evaluation of the model’s performance under limited data conditions. Figure 6 shows the dataset splitting strategy using 5-fold cross-validation.

Machine learning models

In the context of pipeline residual strength prediction, a machine learning model refers to an algorithm that transforms pipeline data with fixed characteristics into predictions of burst pressure. Common machine learning models can be classified into “Single Models” and “Hybrid Models”. The former involves a straightforward prediction process using a single algorithm, while the latter combines multiple simple models to enable more complex predictions. Hybrid models can be further divided into “Ensemble Models” and “Improved Models”. “Ensemble model” combines multiple machine learning techniques into a unified predictive model, whereas “Improved model” integrates a single machine learning model with an optimization method.

Single models

Single model refers to an approach that uses only one machine learning model for prediction. Based on a review and analysis of the literature, the commonly used single models for pipeline residual strength prediction are outlined below.

Statistical regression model

Statistical regression models are employed to model the relationship between one or more independent variables and a dependent variable. The linear regression model is the simplest statistical regression model, as shown in Fig. 7a. The linear model predicts the residual strength by establishing a linear relationship, as shown in the Eq. (4) and Eq. (5):

where \({w}_{n}\) is the weight; \({x}_{n}\) is the characteristic value; \(b\) is bias. \(y\) is the predicted value; \({y}_{i}\) is the real value; \(J(W,b)\) is the value of the loss function.

Linear models assume linear relationships, which means they may fail to capture complex nonlinear relationships accurately. For high-dimensional data like pipeline data, linear models need more degrees of freedom to fit the data, which may lead to overfitting. Regularization penalties are typically applied to prevent overfitting. Cai used three regression methods with different regularization strategies, including Ridge63, Lasso64 and ElasticNet65 for model training66. As shown in Fig. 8, the ElasticNet strategy shows high accuracy on the training set, validation set, and test set. A comparison of ANN, SVR, and LR models revealed that the ANN model achieved the highest training accuracy but exhibited significant overfitting. The training accuracy of the LR model decreased slightly, but it maintained relatively high validation accuracy. Among the three models, the linear model demonstrated the best predictive performance. However, this conclusion is based on a limited dataset and may not always be generalizable. Additional experiments are needed to confirm its reliability. Another statistical regression model applied in the field of pipeline residual strength prediction is GPR67.

K nearest neighbor

KNN performs regression prediction by calculating the distance between a given data point and its nearest K neighbors in the training set, enabling it to handle data intuitively and straightforwardly68, as shown in Fig. 7b.

A review of the existing literature reveals that Wang et al.69 and Abyani et al.67 used the KNN method in their studies. However, it was primarily used as a benchmark for comparison against the main models discussed in the respective works. Because KNN is sensitive to the selection of K value and high computational complexity, it is not very effective in practical application. The DT is a frequently employed classification-based technique. The literature review has revealed a scarcity of studies utilizing a single DT for modeling in the domain of pipeline residual strength prediction. It is common to use multiple decision trees for ensemble learning, which will be detailed in the following sections.

Support vector machine

SVM performs classification and regression tasks by determining a hyperplane that best fits the data while minimizing prediction errors70,71, as shown in Fig. 7c. SVR was introduced as an extension of SVM to deal with regression problems by fitting a function that closely approximates the actual data points. Since residual strength prediction is a regression task, SVR is widely used in the prediction of pipeline residual strength.

There are three important parameters in SVR, including the regularization coefficient (C), the kernel width coefficient (γ), and the type of kernel, all of which are used for grid search. Cai et al. found that the SVR model with an RBF kernel outperformed other models when compared with SVR models using different kernel types66, as shown in Fig. 9.

To address the issues of excessive support vectors and challenging hyperparameter selection in traditional SVM, Tipping proposed the sparse kernel method known as RVM72. Lu et al. was the first to apply RVM to pipeline residual strength prediction, optimizing the correlation vector machine using the multi-objective salp swarm algorithm, which enhanced both the accuracy and stability of the prediction13.

Artificial neural networks

ANN, a widely used technique in pipeline residual strength prediction, consists of three layers: input, hidden, and output, as illustrated in Fig. 7d. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. (6):

where \({w}_{l}\) represents the weight, \({b}_{l}\) represents the bias, \(\sigma\) is the activation function, and \({H}_{l}\) is the output of the neural network.

ANN is a generic term encompassing various specific types of networks tailored for different situations, each with varying complexity and accuracy levels. Table 4 lists the ANN models commonly used in pipeline residual strength prediction.

Simple ANN structures face significant limitations in addressing highly nonlinear problems. With advancements in technology, deep learning models are increasingly being applied to pipeline residual strength prediction73,74. Deep learning models contain multiple hidden layers that enable deeper feature extraction from data, significantly enhancing the model’s representational capacity and performance. Chen et al. utilized MLP and PSO-FFNN models to predict the residual strength of the pipeline75. The MSE of the MLP model was only 0.15, demonstrating strong predictive performance on the dataset. Gholami et al. utilized MLP and SVR with spline and Gaussian kernel to build ANN models and predict pipeline burst pressure. The results indicate that MLP-ANN is moderately accurate for predicting actual results but is less accurate compared to the Gaussian kernel76. Miao and Zhao proposed a novel method for predicting the residual strength of defective pipelines using DELM and enhanced the model’s performance through HTLBO optimization. The model achieved a relative error of less than 6%, indicating superior predictive accuracy compared to other models77. Su et al. developed a deep neural network with seven hidden layers, each comprising 250 nodes. The results demonstrate that this deep learning model delivers high prediction accuracy26.

Hybrid models

Ensemble models

To improve predictive models, strategies such as ensemble modeling can be used. Instead of a single machine learning algorithm, ensemble learning enhances the predictive performance by integrating multiple individual models. By reviewing literature, the ensemble methods applied in the field of pipeline residual strength prediction are RF, ETR, GBDT, AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM, and Stacking.

RF is a robust machine learning method capable of performing regression analysis by integrating a collection of decision trees to improve the accuracy of predictive results78,79. The core concept of RF involves training multiple distinct decision tree models independently and averaging their outputs to predict the test example80.

ETR is a regression model based on the concept of random forests, proposed by Geurts et al. in 200681. Its core idea is to build decision trees by introducing additional randomness on top of random forests, aiming to enhance the model’s generalization ability and reduce training time. The primary difference from traditional random forests is that ETR randomly selects split thresholds at node splitting instead of performing optimal split searches on candidate features.

GBDT is a gradient boosting algorithm based on decision trees. Its core idea is to gradually optimize model performance through ensemble learning82,83,84. GBDT combines the iterative optimization ability of weak learners with the theoretical foundation of gradient descent. By using the negative gradient of the loss function under the current model as pseudo-labels, it builds a series of independent decision trees, enabling the model to continuously approximate the true target function.

AdaBoost is an ensemble learning method based on the weighted combination of weak learners, proposed by Freund and Schapire in 199582,85,86,87. Its core idea is to combine multiple weak learners into a strong learner by progressively adjusting sample weights and learner weights, thereby improving the model’s generalization performance. Unlike traditional simple weighted averaging, the key to AdaBoost lies in iteratively focusing on samples that are difficult to classify, enabling the model to progressively optimize its performance on these samples.

XGBoost is an efficient gradient boosting framework proposed by Chen and Guestrin in 2016, focusing on balancing computational performance and model predictive capability. As an extension of GBDT, XGBoost incorporates techniques such as regularization, parallel computing, and distributed training, offering significant advantages in large-scale data analysis and high-dimensional feature learning88,89,90.

LightGBM is an efficient gradient boosting framework proposed by the Microsoft team, focusing on improving training efficiency on large-scale datasets and high-dimensional sparse data82,91,92,93. Compared to traditional GBDT, LightGBM introduces unique optimization strategies, such as histogram-based decision tree construction and efficient data sampling methods, significantly reducing computational and memory overhead while maintaining model prediction accuracy.

Stacking is an ensemble learning method that combines the predictions of multiple base learners to construct a final strong learner93,94,95. Unlike traditional ensemble methods, stacking does not simply rely on voting or weighted averaging of base learners, but rather merges the predictions of base learners by training a new learner, often referred to as a meta-learner. The core idea of this method is to improve model prediction performance by utilizing the strengths of different models through multi-level learning.

Ma et al. utilized LightGBM to build an oil and gas pipeline burst pressure prediction model, and the prediction results showed that this model can significantly improve the prediction accuracy34, which was found to be the most accurate by comparing this method with other ensemble learning methods such as RF and XGBoost. Xiao et al. modeled various machine learning models, including RF, AdaBoost, and GBDT, and among all the models, the ANN model exhibited the best predictive performance85. Wang and Lu established a Stacking model for predicting the residual strength of corroded oil and gas pipelines. Compared to a single model, the Stacking model exhibits higher prediction accuracy and generalizability17.

Ensemble methods are divided into three categories: Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking. Categorically, RF and ETR belong to the Bagging algorithm in ensemble learning, GBDT, AdaBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM belong to the Boosting algorithm in ensemble learning, as shown in Fig. 10. Bagging divides the dataset into multiple datasets by sampling with putbacks to train multiple models separately. For regression problems such as residual strength prediction, Bagging gives a prediction by averaging the results of multiple tests. Boosting employs the same weak learners as Bagging but trains them sequentially in an adaptive manner, with each new learner relying on the previous model and integrating them based on a specific deterministic strategy.

Improved models

Improved models enhance performance through advanced hyperparameter optimization techniques, significantly improving prediction accuracy. The use of improved models in the literature is shown in Table 5.

Evaluation metrics

Supervised learning models for pipeline residual strength prediction inherently face a trade-off between bias and variance96. Variance measures the degree to which a model’s predictions vary when applied to different datasets. A higher variance suggests the model is more prone to overfitting, as it struggles to generalize across different data distributions. In contrast, high bias often leads to underfitting, where the model fails to capture the underlying patterns, resulting in poor performance on both training and new datasets.

Adjusting model complexity is key to addressing this trade-off. Increasing complexity can reduce bias but may lead to higher variance, while simplifying the model decreases variance at the cost of greater bias. Therefore, achieving good generalization performance requires finding an optimal balance between bias and variance.

The performance of supervised learning models can be evaluated using the following metrics:

where \(i\) represents each sample; \(n\) represents the total number of samples; \({y}_{i}\) is the true value, \({p}_{i}\) is the predicted value, \(\bar{y}\) is the mean value of the samples.

Discussion

The previous section covered data collection and processing, commonly used models for pipeline residual strength prediction, and model evaluation metrics. In practice, the performance of a machine learning model is influenced by factors such as dataset size, preprocessing methods, and model type. This section will explore these aspects in detail.

Data size and division ratio

The size of the dataset is a critical factor that influences the accuracy of the model. The largest dataset of pipeline burst pressure in the reviewed literature contains 1843 data points. These data are far from sufficient for machine learning models. Generally, the performance of a model increases with the size of the data. However, the accuracy of the model does not continuously improve with an increase in data size, and there is a limit to how much data size can enhance the model’s accuracy. In most of the literature, the burst pressure data used for predicting pipeline residual strength is very limited. Without the utilization of FEM and other data generation methods, relying solely on data from full-scale burst tests may result in predictions that fall short of the required accuracy.

In machine learning, the original data is typically divided into three parts: training set, validation set, and test set. A review of the literature reveals that only 12 out of 30 papers employed this three-part division, while the remaining 18 papers divided the data into only training and test sets, as illustrated in Fig. 11. Due to the limited dataset, the original data is often divided into training and test sets only. K-fold cross-validation is employed during training for hyperparameter tuning, which helps mitigate the accuracy limitations caused by the insufficient data volume. As shown in Fig. 11, in pipeline residual strength prediction, the training set typically constitutes more than 70% of the dataset to ensure a high degree of model accuracy.

Data preprocessing analyze

Preprocessing raw data has been demonstrated to enhance data quality, thereby increasing the model’s accuracy. Table 6 presents three sets of comparative data extracted from literature35,59,61, grouped as ①②③, ④⑤, and ⑥⑦. Comparison of the data in the table indicates that preprocessing techniques such as PCA, KPCA, and LLE enhance model accuracy, particularly when the initial accuracy of the model is relatively low. When the model’s accuracy is relatively low, certain data preprocessing techniques can significantly enhance predictive accuracy. However, when the model’s accuracy is already high, traditional preprocessing techniques show limited direct improvement in performance. Nonetheless, data processed by these techniques can serve as a foundation for further enhancing model performance.

Comparative analysis of models

This literature review categorizes models into two main types: single models and hybrid models. Statistical analysis of the literature has been conducted, and the test performance of single, ensemble, and improved models is summarized in Tables 7–9. Due to variations in external factors such as dataset size and quality across different studies, direct comparison and analysis of all statistics are not feasible. Therefore, this review adopts a “partial-then-whole” analysis strategy: first, comparing the performance of different models within the same study, followed by observing their performance under various application conditions. Phan compared the performance of SVR, ANN, and RF in predicting residual strength, and the experimental results showed that the SVR model achieved the best predictive performance97. However, in Cai’s study, the performance of the ANN model surpassed that of the SVR model66.

While ensemble models often perform well in practical applications, their performance is not always superior to that of single models. In the study by Abyani et al., the performance of the GPR and MLP models outperforms that of models like KNN and RF67. In the research by Wang and Lu, the performance of the SVR model outperforms that of ensemble models such as XGBoost and LightGBM17. In Xiao et al.’s study, the ANN model demonstrated the best performance among all models85.

Optimization algorithms can enhance model performance, but their applicability varies under different data conditions. Lu et al. used three optimization algorithms to optimize the SVM. The results showed that only NSGA-II-SVM reduced the RMSE and MAPE values, achieving model optimization, while the PSO and WOA optimization methods increased the RMSE and MAPE values, negatively affecting the model13.

According to the theorem of “No free lunch”, no one machine learning model is suitable for all situations. In practical applications, it is essential to compare different algorithms and select the most appropriate one based on the scale and quality of the available data.

Statistical analysis of evaluation metrics

Model evaluation metrics assess model performance, and five commonly used metrics were identified through a statistical analysis of the literature. Figure 12 shows that R2 is the most commonly used evaluation metric for the pipeline residual strength prediction model. In practical evaluations, model assessment typically involves the analysis of multiple metrics rather than relying on a single one. Among these evaluation metrics, MSE, RMSPE, and MAE vary with data dimensions and do not have fixed benchmarks. In contrast, R2 and MAPE represent relative errors and can be used to make comparisons in different scenarios. R2 ranges from 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating better model performance. The smaller the value of MAPE, the better the performance of the model. However, a higher R2 value does not necessarily imply higher predictive accuracy for the model. R2 is sensitive to outliers, and the presence of outliers may lead to an overestimation of the model’s fitting ability. In practical applications, potential outliers in the data can be identified using boxplots and scatter plots. For datasets that may contain outliers, caution should be exercised when using R2 as the sole performance evaluation metric. Supplementing R2 with additional metrics is recommended for a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance.

Chen categorized the predictive ability of the model into four classes based on the magnitude of the MAPE98. The MAPE of less than 10% indicates that the model is very accurate. The MAPE of between 11% and 20% indicates that the model performs well. The MAPE of between 21% and 50% indicates that the model performs reasonably well. The MAPE of greater than 50% indicates that the model performance is unacceptable. The maximum value of MAPE counted in this study is 31.520%, and the MAPE in the rest of the studies is lower than 20%. It shows that the machine learning model shows good performance in the field of pipeline residual strength prediction.

In addition to the five evaluation metrics mentioned above, other evaluation metrics have also been used to assess the accuracy of the corrosion oil and gas pipeline residual strength prediction models. Lu et al. used three new metrics—root mean squared percentage error (RMSPE), Theil U statistic 1 (U1), and Theil U statistic 2 (U2)—to evaluate the prediction accuracy of the model13. Since RMSPE and Theil U statistics are mainly used in specific fields, they are relatively complex and less intuitive. Specifically, RMSPE, which involves calculating the square root of percentage errors, may amplify errors when handling predictions close to zero, making it difficult to provide an intuitive performance interpretation. Although Theil U statistics can be used to measure the relative performance of model predictions compared to a baseline model, their involvement with baseline predictions and complex formulas means they are less commonly applied in general regression analysis, and may make interpretation of results more difficult. In contrast, commonly used metrics such as R2, MSE, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE not only have simple calculations but also have strong applicability in various regression tasks, making them widely familiar to researchers and engineers, and thus more frequently used for evaluating regression models.

Challenges and perspectives

Machine learning models have been widely used in residual strength prediction of corroded pipelines due to their high efficiency and accuracy. However, machine learning models for residual strength prediction of corroded pipelines face some challenges in practical applications, which may affect the accuracy, stability, and usefulness of the prediction models. Given the work done so far and its limitations, the following challenges in the field of pipeline residual strength prediction need to be addressed.

Interpretability of the model

The widespread use of machine learning methods enables the construction of complex and efficient predictive models. However, these models often lack interpretability, making it challenging to understand how predictions are made. In the field of pipeline management and maintenance, the challenge of model interpretability can have an impact on the trust and adoption of decision makers. Pipeline residual strength prediction models typically involve a large number of features and data, such as pipeline parameters, corrosion parameters, and material parameters. However, complex models may not be able to directly explain which features have influenced the prediction results and how they are related. By using model-agnostic interpretability tools such as SHAP and LIME, models can achieve greater reliability and transparency in practical applications. The SHAP method, based on the Shapley value theory in game theory, explains model outputs by allocating feature importance99,100,101. It not only quantifies each feature’s contribution to a single prediction but also provides insights into the model’s decision-making logic by plotting global feature importance or interaction effect graphs. LIME explains the prediction behavior of complex models for specific inputs by fitting an interpretable linear model based on locally perturbed data102.

Testing standards

In current research, the evaluation of machine learning model performance lacks unified standards, making it difficult to directly compare experimental results across studies. Researchers often build models based on independently collected datasets, which vary significantly in terms of scale, distribution, features, and preprocessing methods. This lack of standardized benchmarks not only limits fair comparisons of model performance but also hinders the promotion and application of the technology to some extent. To address this issue, authoritative organizations could lead the establishment of a model performance testing platform in the future. This platform could offer standardized datasets, evaluation metrics, and testing procedures to regulate the performance evaluation of machine learning models. Through this platform, researchers could validate model performance in a consistent environment, thereby facilitating the comparison and exchange of research outcomes and advancing the scientific development and practical application of machine learning technology in the residual strength prediction of corroded oil and gas pipelines.

Quality of data

From the review, it can be observed that most current studies focus on the development of machine learning algorithms, with relatively little attention given to model data research. Data quality directly affects the accuracy, stability and credibility of the prediction model. Problems in data quality may lead to distortion of the model’s prediction results, affecting the accurate judgment of the pipeline’s health status. To improve data quality and enhance the performance of predictive models, several measures can be implemented: Firstly, to address the class imbalance in datasets, the SMOTE can be employed to generate minority class samples, while random undersampling can be used to reduce majority class samples, achieving a more balanced class distribution and enhancing the model’s ability to recognize minority classes. Secondly, handling missing values is a critical step in improving data quality, and methods like multiple imputation can be applied to fill in missing values, preserving as much original information as possible.

Topicality

As urban infrastructures continue to develop and operate, real-time prediction of the residual strength of pipelines has become critical. In practical applications, achieving real-time prediction encounters various technical and operational challenges. Real-time prediction depends on instantaneous data acquisition and transmission. However, factors like network latency and data processing delays can compromise the real-time performance of sensor data acquisition and transmission. Delays can result in a time gap between prediction outcomes and actual conditions, compromising real-time accuracy. Additionally, complex predictive models often demand significant computational resources and processing time, conflicting with real-time requirements. In the future, edge computing technology and model compression techniques can be integrated to reduce model computational complexity and enhance data transmission speed, thereby meeting the real-time requirements of the model.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Ilman, M. N. & Kusmono, Analysis of internal corrosion in subsea oil pipeline. Case Stud. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2, 1–8 (2014).

Lu, H. & Cheng, Y. F. Detecting urban gas pipeline leaks using a vehicle–canine collaboration strategy. Nat. Cities https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-025-00197-y (2025).

Lu, H., Xi, D., Xiang, Y., Su, Z. & Cheng, Y. F. Vehicle-canine collaboration for urban pipeline methane leak detection. Nat. Cities. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44284-024-00183-w (2025).

Adumene, S., Khan, F., Adedigba, S., Zendehboudi, S. & Shiri, H. Dynamic risk analysis of marine and offshore systems suffering microbial induced stochastic degradation. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 207, 107388 (2021).

Bhandari, J., Khan, F., Abbassi, R., Garaniya, V. & Ojeda, R. Modelling of pitting corrosion in marine and offshore steel structures – A technical review. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 37, 39–62 (2015).

Lu, H. et al. Theory and machine learning modeling for burst pressure estimation of pipeline with multipoint corrosion. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 14, 04023022 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. The research progress and prospect of data mining methods on corrosion prediction of oil and gas pipelines. Eng. Fail. Anal. 144, 106951 (2023).

Shaik, N. B., Pedapati, S. R., Othman, A. R., Bingi, K. & Dzubir, F. A. A. An intelligent model to predict the life condition of crude oil pipelines using artificial neural networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 14771–14792 (2021).

Askari, M., Aliofkhazraei, M. & Afroukhteh, S. A comprehensive review on internal corrosion and cracking of oil and gas pipelines. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 71, 102971 (2019).

Shaik, N. B., Pedapati, S. R. & B. A. Dzubir, F. A. Remaining useful life prediction of a piping system using artificial neural networks: a case study. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13, 101535 (2022).

Shaik, N. B., Jongkittinarukorn, K., Benjapolakul, W. & Bingi, K. A novel neural network-based framework to estimate oil and gas pipelines life with missing input parameters. Sci. Rep. 14, 4511 (2024).

Ji, M., Yang, M. & Soghrati, S. A deep learning model to predict the failure response of steel pipes under pitting corrosion. Comput. Mech. 71, 295–310 (2023).

Lu, H., Iseley, T., Matthews, J., Liao, W. & Azimi, M. An ensemble model based on relevance vector machine and multi-objective salp swarm algorithm for predicting burst pressure of corroded pipelines. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 203, 108585 (2021).

Soomro, A. A. et al. Integrity assessment of corroded oil and gas pipelines using machine learning: a systematic review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 131, 105810 (2022).

Shaik, N. B. et al. Recurrent neural network-based model for estimating the life condition of a dry gas pipeline. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 164, 639–650 (2022).

Data and Statistics Overview | PHMSA. https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/data-and-statistics/pipeline/data-and-statistics-overview (Washington, DC, United States).

Wang, Q. & Lu, H. A novel stacking ensemble learner for predicting residual strength of corroded pipelines. npj Mater. Degrad. 8, 87 (2024).

Lu, H., Xu, Z.-D., Iseley, T. & Matthews, J. C. Novel data-driven framework for predicting residual strength of corroded pipelines. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 12, 04021045 (2021).

Zhou, R., Gu, X. & Luo, X. Residual strength prediction of X80 steel pipelines containing group corrosion defects. Ocean Eng. 274, 114077 (2023).

Cross, C. S. B31G - Manual for Determining the Remaining Strength of Corroded Pipelines Supplement to ASME B31 Code for Pressure Piping (ASME, 2012).

Guedes Soares, C., Garbatov, Y. & Zayed, A. Effect of environmental factors on steel plate corrosion under marine immersion conditions. Corros. Eng., Sci. Technol. 46, 524–541 (2011).

Huang, Y., Zhang, P. & Qin, G. Investigation by numerical modeling of the mechano-electrochemical interaction at a dent-corrosion defect on pipelines. Ocean Eng. 256, 111402 (2022).

Kiefner, J. F. & Vieth, P. H. A modified criterion for evaluating the remaining strength of corroded pipe. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/7181509 (1989).

Liu, H., Khan, F. & Thodi, P. Revised burst model for pipeline integrity assessment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 80, 24–38 (2017).

Amaya-Gómez, R., Sánchez-Silva, M., Bastidas-Arteaga, E., Schoefs, F. & Muñoz, F. Reliability assessments of corroded pipelines based on internal pressure – a review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 98, 190–214 (2019).

Su, Y., Li, J., Yu, B., Zhao, Y. & Yao, J. Fast and accurate prediction of failure pressure of oil and gas defective pipelines using the deep learning model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 216, 108016 (2021).

Hibbitt, H. D. ABAQUS/EPGEN—a general purpose finite element code with emphasis on nonlinear applications. Nucl. Eng. Des. 77, 271–297 (1984).

Mok, D. H. B., Pick, R. J., Glover, A. G. & Hoff, R. Bursting of line pipe with long external corrosion. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 46, 195–216 (1991).

Zhang, T. et al. Efficient prediction method of triple failure pressure for corroded pipelines under complex loads based on a backpropagation neural network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 231, 108990 (2023).

Phan, H. C., Dhar, A. S. & Mondal, B. C. Revisiting burst pressure models for corroded pipelines. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 44, 485–494 (2017).

Ma, B., Shuai, J., Liu, D. & Xu, K. Assessment on failure pressure of high strength pipeline with corrosion defects. Eng. Fail. Anal. 32, 209–219 (2013).

Huang, Y., Qin, G. & Hu, G. Failure pressure prediction by defect assessment and finite element modelling on pipelines containing a dent-corrosion defect. Ocean Eng. 266, 112875 (2022).

Qin, G., Cheng, Y. F. & Zhang, P. Finite element modeling of corrosion defect growth and failure pressure prediction of pipelines. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 194, 104509 (2021).

Ma, H. et al. A new hybrid approach model for predicting burst pressure of corroded pipelines of gas and oil. Eng. Fail. Anal. 149, 107248 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. Deeppipe: theory-guided neural network method for predicting burst pressure of corroded pipelines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 162, 595–609 (2022).

Hussain, M. et al. Review of prediction of stress corrosion cracking in gas pipelines using machine learning. Machines 12, 42 (2024).

Rachman, A., Zhang, T. & Ratnayake, R. M. C. Applications of machine learning in pipeline integrity management: a state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 193, 104471 (2021).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. & Group, T. P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6, e1000097 (2009).

Zhang, L. et al. A review of machine learning in building load prediction. Appl. Energy 285, 116452 (2021).

Benjamin, A. C., Vieira, R. D., Freire, J. L. F. & de Castro, J. T. P. Burst tests on pipeline with long external corrosion. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. Dig. Collect. https://doi.org/10.1115/IPC2000-193 (2016).

Benjamin, A. C., Freire, J. L. F., Vieira, R. D., Diniz, J. L. C. & De Andrade, E. Q. Burst tests on pipeline containing interacting corrosion defects. In 24th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Vol. 3 403–417 (ASMEDC, Halkidiki, Greece, 2005).

Vijaya Kumar, S. D., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. Failure pressure prediction of high toughness pipeline with a single corrosion defect subjected to combined loadings using artificial neural network (ANN). Metals 11, 373 (2021).

Oliva, J. B. et al. Bayesian nonparametric kernel-learning. In Proc. 19th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics 1078–1086 (PMLR, 2016).

Patki, N., Wedge, R. & Veeramachaneni, K. The synthetic data vault. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA) 399–410 https://doi.org/10.1109/DSAA.2016.49 (2016).

Aldosari, H., Rajasekaran, S. & Ammar, R. Generative adversarial neural network and genetic algorithms to predict oil and gas pipeline defect lengths. In Proc. of the ISCA 34th International Conference, Online 21–29 (2021).

Almustafa, M. K. & Nehdi, M. L. Machine learning prediction of structural response for FRP retrofitted RC slabs subjected to blast loading. Eng. Struct. 244, 112752 (2021).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144 (2020).

Marani, A., Jamali, A. & Nehdi, M. L. Predicting ultra-high-performance concrete compressive strength using tabular generative adversarial networks. Materials 13, 4757 (2020).

Park, N. et al. Data synthesis based on generative adversarial networks. Proc. VLDB Endow. 11, 1071–1083 (2018).

Xu, L. & Veeramachaneni, K. Synthesizing tabular data using generative adversarial networks. Preprint arXiv:1811.11264 (2018).

Jain, S., Seth, G., Paruthi, A., Soni, U. & Kumar, G. Synthetic data augmentation for surface defect detection and classification using deep learning. J. Intell. Manuf. 33, 1007–1020 (2022).

Xu, P., Du, R. & Zhang, Z. Predicting pipeline leakage in petrochemical system through GAN and LSTM. Knowl. Based Syst. 175, 50–61 (2019).

He, Z. & Zhou, W. Generation of synthetic full-scale burst test data for corroded pipelines using the tabular generative adversarial network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 115, 105308 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, Q., Singh, V. P. & Xiao, M. General correlation analysis: a new algorithm and application. Stoch. Environ. Res Risk Assess. 29, 665–677 (2015).

Baghban, A., Kahani, M., Nazari, M. A., Ahmadi, M. H. & Yan, W.-M. Sensitivity analysis and application of machine learning methods to predict the heat transfer performance of CNT/water nanofluid flows through coils. Int. J. Heat. Mass Transf. 128, 825–835 (2019).

Ding, Y., Zhang, Q., Yuan, T. & Yang, K. Model input selection for building heating load prediction: a case study for an office building in Tianjin. Energy Build 159, 254–270 (2018).

Li, X., Zhang, L., Khan, F. & Han, Z. A data-driven corrosion prediction model to support digitization of subsea operations. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 153, 413–421 (2021).

Qiang, G., Zhe, T., Yan, D. & Neng, Z. An improved office building cooling load prediction model based on multivariable linear regression. Energy Build 107, 445–455 (2015).

Phan, H. C. & Duong, H. T. Predicting burst pressure of defected pipeline with principal component analysis and adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 189, 104274 (2021).

Tenenbaum, J. B., de Silva, V. & Langford, J. C. A global geometric framework for nonlinear dimensionality reduction. Science 290, 2319–2323 (2000).

Li, X., Jia, R. & Zhang, R. A data-driven methodology for predicting residual strength of subsea pipeline with double corrosion defects. Ocean Eng. 279, 114530 (2023).

Lu, H., Matthews, J. C., Azimi, M. & Iseley, T. Near real-time HDD pullback force prediction model based on improved radial basis function neural networks. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 11, 04020042 (2020).

Hoerl, A. E. & Kennard, R. W. Ridge regression: biased estimation for nonorthogonal problems. Technometrics 12, 55–67 (1970).

Tibshirani, R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 58, 267–288 (1996).

Zou, H. & Hastie, T. Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 67, 301–320 (2005).

Cai, J., Jiang, X., Yang, Y., Lodewijks, G. & Wang, M. Data-driven methods to predict the burst strength of corroded line pipelines subjected to internal pressure. J. Mar. Sci. Appl. 21, 115–132 (2022).

Abyani, M., Bahaari, M. R., Zarrin, M. & Nasseri, M. Predicting failure pressure of the corroded offshore pipelines using an efficient finite element based algorithm and machine learning techniques. Ocean Eng. 254, 111382 (2022).

Mahmutoglu, Y. & Turk, K. Positioning of leakages in underwater natural gas pipelines for time-varying multipath environment. Ocean Eng. 207, 107454 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Status diagnosis and feature tracing of the natural gas pipeline weld based on improved random forest model. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 200, 104821 (2022).

Bennett, K. P. & Mangasarian, O. L. Robust linear programming discrimination of two linearly inseparable sets. Optim. Methods Softw. 1, 23–34 (1992).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Tipping, M. E. Sparse bayesian learning and the relevance vector machine. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 1, 211–244 (2001).

Silva, R. C. C., Guerreiro, J. N. C. & Loula, A. F. D. A study of pipe interacting corrosion defects using the FEM and neural networks. Adv. Eng. Softw. 38, 868–875 (2007).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Residual strength prediction of corroded pipelines using multilayer perceptron and modified feedforward neural network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 231, 108980 (2023).

Gholami, H., Shahrooi, S. & Shishesaz, M. Predicting the burst pressure of high-strength carbon steel pipe with gouge flaws using artificial neural network. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 11, 04020034 (2020).

Miao, X. & Zhao, H. Novel method for residual strength prediction of defective pipelines based on HTLBO-DELM model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 237, 109369 (2023).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Louppe, G. Understanding random forests: from theory to practice (Doctoral dissertation, Universite de Liege, Belgium, 2014).

Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 24, 123–140 (1996).

Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn. 63, 3–42 (2006).

Yingjie, Z., Yibo, A. & Weidong, Z. Physics informed ensemble learning used for interval prediction of fracture toughness of pipeline steels in hydrogen environments. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 130, 104302 (2024).

Yu, A. et al. Rapid accomplishment of cost-effective and macro-defect-free LPBF-processed Ti parts based on deep data augmentation. J. Manuf. Process. 120, 1023–1034 (2024).

Li, Q. & Song, Z. Prediction of compressive strength of rice husk ash concrete based on stacking ensemble learning model. J. Clean. Prod. 382, 135279 (2023).

Xiao, R., Zayed, T., Meguid, M. A. & Sushama, L. Predicting failure pressure of corroded gas pipelines: a data-driven approach using machine learning. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 184, 1424–1441 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. Interpretable machine learning for maximum corrosion depth and influence factor analysis. npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 9 (2023).

Liu, T. et al. Modeling the load carrying capacity of corroded reinforced concrete compression bending members using explainable machine learning. Mater. Today Commun. 36, 106781 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. XGBoost-based algorithm interpretation and application on post-fault transient stability status prediction of power system. IEEE Access 7, 13149–13158 (2019).

Gertz, M. et al. Using the XGBoost algorithm to classify neck and leg activity sensor data using on-farm health recordings for locomotor-associated diseases. Comput. Electron. Agric. 173, 105404 (2020).

Mo, H., Sun, H., Liu, J. & Wei, S. Developing window behavior models for residential buildings using XGBoost algorithm. Energy Build 205, 109564 (2019).

Geng, Z. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning-based predictive model for assessing the 90-day prognostic outcome of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Transl. Med. 22, 236 (2024).

Mesghali, H. et al. Predicting maximum pitting corrosion depth in buried transmission pipelines: insights from tree-based machine learning and identification of influential factors. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 187, 1269–1285 (2024).

Khan, A. A., Chaudhari, O. & Chandra, R. A review of ensemble learning and data augmentation models for class imbalanced problems: combination, implementation and evaluation. Expert Syst. Appl. 244, 122778 (2024).

Goliatt, L., Saporetti, C. M. & Pereira, E. Super learner approach to predict total organic carbon using stacking machine learning models based on well logs. Fuel 353, 128682 (2023).

Hajihosseinlou, M., Maghsoudi, A. & Ghezelbash, R. Stacking: a novel data-driven ensemble machine learning strategy for prediction and mapping of Pb-Zn prospectivity in Varcheh district, west Iran. Expert Syst. Appl. 237, 121668 (2024).

De Masi, G., Gentile, M., Vichi, R., Bruschi, R. & Gabetta, G. Machine learning approach to corrosion assessment in subsea pipelines. In OCEANS 2015 - Genova 1–6 https://doi.org/10.1109/OCEANS-Genova.2015.7271592 (2015).

Phan, H. C. & Dhar, A. S. Predicting pipeline burst pressures with machine learning models. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 191, 104384 (2021).

Chen, R. J. C., Bloomfield, P. & Fu, J. S. An evaluation of alternative forecasting methods to recreation visitation. J. Leis. Res. 35, 441–454 (2003).

Shen, Y., Wu, S., Wang, Y., Wang, J. & Yang, Z. Interpretable model for rockburst intensity prediction based on Shapley values-based Optuna-random forest. Underground Space https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2024.09.002 (2024).

Zhang, Y. l., Qiu, Y-g., Armaghani, D. J., Monjezi, M. & Zhou, J. Enhancing rock fragmentation prediction in mining operations: A Hybrid GWO-RF model with SHAP interpretability. J. Cent. South Univ. 31, 2916–2929 (2024).

Ding, H. et al. A hybrid approach for modeling bicycle crash frequencies: integrating random forest based SHAP model with random parameter negative binomial regression model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 208, 107778 (2024).

Ukwuoma, C. C. et al. Enhancing hydrogen production prediction from biomass gasification via data augmentation and explainable AI: a comparative analysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 68, 755–776 (2024).

Lo, M., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. Failure pressure prediction of a corroded pipeline with longitudinally interacting corrosion defects subjected to combined loadings using FEM and ANN. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 9, 281 (2021).

Li, X., Jing, H., Liu, X., Chen, G. & Han, L. The prediction analysis of failure pressure of pipelines with axial double corrosion defects in cold regions based on the BP neural network. Int. J. Press. Vessels Pip. 202, 104907 (2023).

Oh, D., Race, J., Oterkus, S. & Koo, B. Burst pressure prediction of API 5L X-grade dented pipelines using deep neural network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 8, 766 (2020).

Liu, P., Han, Y. & Tian, Y. Residual strength prediction of pipeline with single defect based on SVM algorithm. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1944, 012019 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. An ANN-based failure pressure prediction method for buried high-strength pipes with stray current corrosion defect. Energy Sci. Eng. 8, 248–259 (2020).

Lo, M., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. ANN- and FEA-based assessment equation for a corroded pipeline with a single corrosion defect. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 476 (2022).

Lo, M., Vijaya Kumar, S. D., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. An artificial neural network-based equation for predicting the remaining strength of mid-to-high strength pipelines with a single corrosion defect. Appl. Sci. 12, 1722 (2022).

Chin et al. Failure pressure prediction of pipeline with single corrosion defect using artificial neural network. Pipeline Sci. Technol. 4, 10–17 (2020).

Keshtegar, B. & el Amine Ben Seghier, M. Modified response surface method basis harmony search to predict the burst pressure of corroded pipelines. Eng. Fail. Anal. 89, 177–199 (2018).

Sun, C., Wang, Q., Li, Y., Li, Y. & Liu, Y. Numerical simulation and analytical prediction of residual strength for elbow pipes with erosion defects. Materials 15, 7479 (2022).

Tingke, L., Yuanchun, P., Jiadi, L., Dulin & Xingqin, L. Research on residual strength prediction model of corroded pipeline based on improved PSO-BP. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 687, 012007 (2021).

Vijaya Kumar, S. D., Lo, M., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. Failure pressure prediction of medium to high toughness pipe with circumferential interacting corrosion defects subjected to combined loadings using artificial neural network. Appl. Sci. 12, 4120 (2022).

Vijaya Kumar, S. D., Lo, M., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. Empirical failure pressure prediction equations for pipelines with longitudinal interacting corrosion defects based on artificial neural network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 764 (2022).

Xu, W.-Z., Li, C. B., Choung, J. & Lee, J.-M. Corroded pipeline failure analysis using artificial neural network scheme. Adv. Eng. Softw. 112, 255–266 (2017).

Zhang, H. & Tian, Z. Failure analysis of corroded high-strength pipeline subject to hydrogen damage based on FEM and GA-BP neural network. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 4741–4758 (2022).

Vijaya Kumar, S. D., Karuppanan, S. & Ovinis, M. Artificial neural network-based failure pressure prediction of API 5L X80 pipeline with circumferentially aligned interacting corrosion defects subjected to combined loadings. Materials 15, 2259 (2022).

Meng, H., Xu, N., Zhu, Y. & Mei, G. Generating stochastic structural planes using statistical models and generative deep learning models: a comparative investigation. Mathematics 12, 2545 (2024).

Nieto, P. J. G., Gonzalo, E. G., García, L. A. M., Prado, L. Á. & Sánchez, A. B. Predicting the critical superconducting temperature using the random forest, MLP neural network, M5 model tree and multivariate linear regression. Alex. Eng. J. 86, 144–156 (2024).

Ebrahimi, M. & Basiri, A. RACEkNN: a hybrid approach for improving the effectiveness of the k-nearest neighbor algorithm. Knowl. Based Syst. 301, 112357 (2024).

Wang, R., Zhang, M., Gong, F., Wang, S. & Yan, R. Improving port state control through a transfer learning-enhanced XGBoost model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 253, 110558 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This article is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52402421) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20220848).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing - original draft, H.L.: Conceptualization, Writing - Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Lu, H. Machine learning methods for predicting residual strength in corroded oil and gas steel pipes. npj Mater Degrad 9, 30 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00573-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00573-y

This article is cited by

-

Modeling of Residual Stress and Microstructure Evolution in Machining: A Review

International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing (2026)

-

Intelligent prediction of residual strength in blended hydrogen–natural gas pipelines with crack-in-dent defects

npj Materials Degradation (2025)

-

Advancing LightGBM with data augmentation for predicting the residual strength of corroded pipelines

npj Materials Degradation (2025)