Abstract

The current research utilized a unique material design of nanostructured medium-entropy alloys with numerous defect sinks, offering great potential to withstand extreme conditions in advanced nuclear reactors. Hence, this work examined oxide dispersion strengthened (ODS)-NiCoFeCr alloy with nanosized grains after Ni+2 irradiation at 580 °C up to a peak damage of 101 displacements per atom. The alloy showed insignificant hardening and no detectable void formation following irradiation. Also, oxide nanoprecipitates and grains exhibited a limited growth of ~2 and ~5 nm, respectively, with irradiation. The volume-averaged dislocation length density remained on the order of ~1014 m−2, and the mean dislocation length showed a slight increase from 89 to 97 nm, with irradiation. A lower level of radiation-induced segregation was observed at the grain boundaries; however, the extent of RIS depended on the misorientation angles, with a maximum at 45.7° among the grain boundaries analyzed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concentrated solid solution alloys (CSAs) are metallic alloys that have garnered significant scientific interest over the past one to two decades1. Unlike conventional dilute solid solution alloys, CSAs contain several principal elements, mostly in equiatomic proportions. Sometimes, CSAs are non-equiatomic; however, the elemental proportions are high enough to facilitate significant interaction between the elements. Single-phase (SP) transition metal (TM) based CSAs with face-centered cubic (FCC), body-centered cubic (BCC), or hexagonal close-packed structures have been topics of great interest recently1. The TM-based SP-CSAs are tunable and can achieve different levels of chemical disorder by varying the TMs1. High-entropy alloys with five or more principal elements and medium-entropy alloys (MEAs) with generally three to four principal elements are popular examples of SP-CSAs1,2,3. By altering the elemental compositions, the alloys can exhibit various properties, such as high thermal stability, high strength-to-weight ratio, high-temperature strength4,5, hardness6, fatigue and wear resistance, and corrosion resistance7.

SP-CSAs can additionally possess favorable radiation tolerant properties; hence the development of structural materials for advanced nuclear reactor designs such as the Gen IV reactors can benefit from SP-CSAs1,2,8. The designs involve severe environments, including radiation damage greater than 50 displacements per atom (dpa), high temperatures (>500 °C), high structural stresses, and corrosive conditions9,10,11. Therefore, studying material degradation under high-temperature irradiation conditions is critical for assessing novel materials such as SP-CSAs. Preliminary studies show that TM-based SP-CSAs exhibit better radiation damage resistance than conventional alloys with lower swelling12, better phase stability, resistance to irradiation defect formation, and minimal irradiation hardening8.

One such TM-based SP-CSAs of interest is NiCoFeCr, which have demonstrated phase stability and relatively lower radiation-induced segregation (RIS) at 400 °C up to 1 dpa electron irradiation13. Also, NiCoFeCr exhibits He bubble growth resistance due to higher energy barriers for diffusion compared to pure Ni, as demonstrated by first-principles calculations14. In single-crystal NiCoFeCr, irradiated with 3 MeV Ni ions up to a fluence of 5 × 1016 ions/cm2, preferential diffusion of vacancies via Cr and Fe causes depletion of Fe/Cr and enrichment of Ni/Co around voids. This preferential diffusion also leads to a variation in matrix composition along the depth, as vacancies migrate to deeper regions to form voids15. Even though NiCoFeCr showed suppression of void formation in the peak damage region up to 54 dpa, the alloy exhibited substantial growth of voids at higher doses, up to 250 dpa, with 3 MeV Ni ion irradiation to a fluence of 8 × 1016 ions/cm2 at 500 °C16. Similarly, dislocation sizes drastically increased from ~30 nm at 54 dpa to ~90 nm at 86 dpa16. To address these drawbacks and further enhance radiation resistance, some of the proposed strategies include introducing substitutional dopants to tune local chemistry17 and incorporating structural complexities such as nanosized grains and oxide-precipitates18. Compared to coarse-grained alloys, alloys with nanometer-sized grains exhibit superior radiation tolerance due to the increased grain boundary area that enhances recombination and absorption of irradiation-induced defects such as vacancies and interstitials19,20. In addition, finer grains impart better mechanical properties due to the strengthening effect provided by dislocation pile-up19,20. Similarly, oxide dispersion-strengthened (ODS) alloys, primarily containing Y2O3 particles and Y-Ti-O clusters/oxide nanoprecipitates, demonstrated superior mechanical properties and radiation resistance18,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, as the particles/precipitates can strengthen the material via dislocation pinning, and their interfaces with the matrix act as sinks for defects induced by irradiation.

The current work uniquely designed and examined a novel nanostructured ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy with oxide nanoprecipitates and nanosized grains. However, the current understanding and assessment of such ODS-CSAs following high-temperature irradiation are limited18,21,22,23,24,25. Hence, such ODS-CSAs warrant significant attention for the development of innovative materials for advanced reactor concepts. Consequently, the present research explores the effects of high-temperature irradiation on the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy, including key material degradation phenomena such as irradiation hardening, swelling, and instability of nanostructures.

Results

SRIM calculations

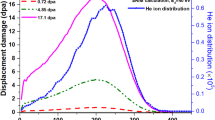

Figure 1 shows the full-damage cascade Stopping and Range of Ions in Matter (SRIM)28 calculations used to estimate the dpa and Ni2+ concentration along the depth of the sample from the irradiation surface. The SRIM calculations measure atomic displacements and reveal a damage profile where the irradiation damage (in dpa) gradually increases to a maximum before decreasing sharply. In NiCoFeCr, the results show a peak damage of ~101 dpa at a depth of ~0.90 µm. Additionally, Ni2+ irradiation leads to a minor accumulation of ions. Therefore, the SRIM calculations reveal a steady increase in Ni2+ concentration to a maximum of ~1.19% at ~1.16 µm, followed by a decrease to zero at ~1.7 µm.

Nanoindentation hardness

Figure 2 illustrates a column chart showing the average hardness values of ODS-NiCoFeCr measured using nanoindentation from the pristine and irradiated regions. As indicated in Fig. 2, the pristine regions of the ODS-NiCoFeCr exhibit an average nanoindentation hardness of 5.70 + 0.54 GPa, which is significantly higher than the reported hardness of single-crystal NiCoFeCr (~2.5 GPa)29. This enhancement in hardness highlights the contribution of nanostructures such as the nano-sized grains and nanoprecipitates formed due to the addition of nanoparticles (Y2O3 + ZrO2 and Ti) in conjunction with the conventional Cr3C7-type carbide precipitates. In the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy, Cr3C7-type carbide formation occurred during ball milling, as a result of carbon contamination introduced by the ethyl alcohol solvent, which was used as a process control agent to minimize oxidation and prevent cold welding22. The nanostructures and Cr3C7 precipitates collectively improve the hardness of the alloy by more than twofold. Subsequently, the hardness of pristine ODS-NiCoFeCr is comparable to or greater than that of various well-known potential structural materials, such as the ODS steel alloys30,31,32,33. As shown in Fig. 2, the irradiated regions of ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy exhibited an average hardness value of 5.63 + 0.87 GPa. Therefore, the results indicate no significant enhancement of hardness with irradiation in ODS-NiCoFeCr, suggesting the absence of discernable irradiation hardening. Additionally, the nanoindentation results indicate elastic moduli of 239 + 38 GPa and 236 + 27 GPa for the pristine and irradiated ODS-NiCoFeCr, respectively. Consequently, the corresponding elastic modulus (E) to hardness (H) ratios (E/H) are calculated to be 42.1 ± 6.1 and 42.5 ± 6.2 for the pristine and irradiated ODS-NiCoFeCr. These results indicate that irradiation has an insignificant effect on both the elastic modulus and the E/H ratio.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterization of the defects

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the irradiation dose (in dpa) varies with the distance from the surface; hence, each grain in the sample endured different levels of irradiation dose depending on the location of the grain from the surface. Therefore, we examined several grains located at varying depths from the surface within the irradiated region of ODS-NiCoFeCr. Figure 3 depicts the images of these grains, indicated by black arrows, captured using the defocus TEM technique. Defocus TEM imaging such as under-focus and over-focus are well-known techniques for examining irradiation-induced voids16. Typically, bubbles and voids appear as bright spots surrounded by dark fringes in underfocus images, and as dark spots with bright fringes in overfocus images34. As shown in Fig. 3, the images do not reveal any voids induced by irradiation resolvable via TEM in all the grains located at various depths from the surface to the end-of-the irradiation range at 1.6 µm. However, the loop-like contrast marked by blue arrows in Fig. 3b, e, h, k, n is attributed to oxide nanoprecipitates. The formation and coalescence of the voids could lead to detrimental material swelling and the material can eventually fail. Thus, the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy demonstrates resistance to void swelling even after irradiation to a fluence of 5 × 1016 ions/cm2 at 580 °C.

Infocus, underfocus, and overfocus images illustrate the no occurrence of irradiation-induced voids in various grains at the depths of a–c 0.27 µm, d–f 0.5 µm, g–i 0.72 µm, j–l 1 µm, and m–o 1.5 µm from the surface. The black arrows indicate the location of the grains under examination and the blue arrows represent the oxide nanoprecipitates with loop-like contrast.

Figure 4 presents the scanning (S)TEM-bright field (BF) two-beam condition images, captured using the g{200} diffracted beam and the transmitted beam, from different grains in the irradiated and pristine regions. Figure 4a–g shows images of seven grains located at various depths within the irradiated region of the ODS-NiCoFeCr sample, while Fig. 4h depicts a grain from the pristine region. Similar to Fig. 3, we examined multiple grains in the irradiated region to capture areas to different irradiation doses. Additionally, grains were chosen such that diffraction originated exclusively from the selected grains, enabling proper two-beam conditions. Also, finding multiple dislocations is challenging in smaller grains. Therefore, we used grains larger than the average grain size to obtain a dislocation statistic. The micrographs reveal the presence of dislocation lines and oxide nanoprecipitates, indicated by blue and green arrows, respectively. In addition, Fig. 4 highlights the pinning of dislocations at the oxide nanoprecipitates, represented by yellow arrows. We will discuss the characteristics and evolution of oxide nanoprecipitates in the following sections. Since ODS-NiCoFeCr did not exhibit a noticeable presence of voids (Fig. 3), dislocations appear to be the major defect structures, as shown in Fig. 4.

The two-beam conditions images captured with g{220} illustrate the presence of irradiation-induced dislocation microstructures in various grains at a depth of a 0.3 µm, b 0.4 µm, c 0.5 µm, d 0.7 µm, e 0.9 µm, f 1.0 µm, g 1.5 µm, and h 3.5 µm from the surface. The blue, green, and yellow arrows represent the dislocations, oxide nanoprecipitates, and the pinning of dislocations at the oxide nanoprecipitates, respectively.

Table 1 describes the dislocation length densities and mean dislocation lengths of each selected grain (shown in Fig. 4) and single-crystal NiCoFeCr16. We utilized STEM-BF two-beam condition images, captured using the g{220} diffracted beam and the transmitted beam, for these estimations. The calculations show variations in dislocation length densities and mean dislocation lengths among the selected grains; however, no clear trend is observed with respect to the dpa level in these grains. The variations in dislocation length densities and mean dislocation lengths mentioned in Table 1 arise primarily due to the STEM-BF two-beam condition imaging technique used for quantification, combined with the depth-dependent variation in irradiation dose. Ideally, multiple two-beam condition images using different diffraction vectors would be needed to fully capture dislocation networks. However, achieving multiple diffraction conditions via tilting is particularly challenging in nanosized grains of the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy. Consequently, only partial dislocation lines are visible in the images shown in Fig. 4 and the reported values represent a partial estimation. Nonetheless, since our study focuses on the comparison between pristine and irradiated conditions within the same sample, using a consistent diffraction condition ensures validity and reliability of the relative trends. Furthermore, the regions near the surface are influenced by surface fluxes, while those near the peak damage experience significant defect annihilation, necessitating the identification of a “safe” region for reliable analysis in the irradiated ODS-NiCoFeCr. Accordingly, we confined our analysis to grains located at depths of 0.3 µm, 0.4 µm, 0.5 µm, and 0.7 µm for the calculation of volume-averaged dislocation length density and volume-averaged mean dislocation length, which were found to be 5.2 × 10¹⁴ m−2 and 71 nm, respectively. These values indicate a slight increase in dislocation line density and a slight decrease in mean dislocation length compared to the pristine region (4.6 × 10¹⁴ m−2 and 89 nm). Hence, the contribution of irradiation-induced dislocations is minimal.

Scanning precession electron diffraction (SPED)-ASTAR grain analysis

Figure 5a, b shows the grain equivalent diameter histograms for the pristine and irradiated regions of the sample, obtained via the SPED-ASTAR TEM technique. The equivalent grain diameter histograms exhibit a log-normal distribution trend for pristine and irradiated regions, shown as blue and red curves, respectively. Figure 5a indicates a peak in the 20–30 nm bin for the pristine region, whereas Fig. 5b shows a peak in the 30–40 nm bin for the irradiated region. Consequently, the mean (geometric mean) grain equivalent diameters are 54 + 2 nm for the pristine and 59 + 2 nm for the irradiated region, indicating a slight grain growth upon irradiation at 580 °C. Grains smaller than 30 nm contribute to 26% of the grains in the pristine region; while such small grains add up to 18% in the irradiated region. In contrast, grains larger than 90 nm constitute 23% and 29% in pristine and irradiated regions, respectively. Furthermore, the irradiated region contained 249 grains within the same scan area, compared to 269 grains in the pristine region. Thus, these observations suggest the coarsening of relatively larger grains at the expense of smaller ones with irradiation at 580 °C in ODS-NiCoFeCr. Figure 5c, d presents the misorientation angle distributions of grain boundaries in the pristine and irradiated regions, respectively. The plots illustrate an increase in relatively lower misorientation angles (up to 20°) from 16% in the pristine to 22% in the irradiated region, along with a decrease in higher-angle misorientations (50°–65°) from 55% in the pristine to 42% in the irradiated region. This redistribution of misorientation angles is attributed to the grain boundary movement associated with irradiation-induced grain growth. Such an increase in lower angle misorientations has been reported during conventional thermally driven grain growth as well34,35.

STEM-Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) analysis

Figure 6a, b depicts the STEM-EELS Oxygen composition maps, illustrating the presence and distribution of oxide nanoprecipitates (bright contrast) in the pristine and irradiated regions, respectively. The nanoprecipitate distribution is homogeneous throughout the sample; however, the precipitate sizes vary. Figure 6a, b shows a total of 422 and 330 nanoprecipitates in the pristine and irradiated regions, respectively. The nanoprecipitate number densities corresponding to Fig. 6a, b are 1.95 × 1023 m−3 for the pristine and 1.92 × 1023 m−3 for the irradiated regions of ODS-NiCoFeCr. The equivalent diameter distribution of the nanoprecipitates, illustrated in Fig. 6c, closely follows a typical lognormal distribution (see inset), characterized by a long tail. The equivalent diameter distribution shifts rightward, indicating precipitate growth upon irradiation. For instance, the peak in equivalent diameter shifts from the 2–4 nm bin for the pristine region to the 4–6 nm bin for the irradiated region. Subsequently, this precipitate size growth is further validated by the mean (geometric mean) equivalent diameter calculations of the nanoprecipitates, where 5 + 2 nm and 7 + 2 nm are the mean values for pristine and irradiated regions, respectively. Furthermore, the cumulative number fraction of smaller precipitates (equivalent diameter less than 4 nm) decreases from 38% in the pristine to 17% in the irradiated region. In contrast, the number fraction of larger precipitates (equivalent diameter greater than 10 nm) increases significantly from 9% in the pristine region to 22% in the irradiated region. The findings collectively indicate coarsening of oxide nanoprecipitates due to irradiation at 580 °C in ODS-NiCoFeCr.

Figure 7a–d presents the STEM-EELS compositional maps for Ni, Co, Fe, and Cr, respectively, obtained from the irradiated region of the ODS-NiCoFeCr sample. Unlike in single-crystal NiCoFeCr, we do not observe any substantial chemical segregation along the irradiation depth profile15. However, the compositional maps reveal RIS at grain boundaries: Ni and Co show enrichment (bright contrast), whereas Fe and Cr exhibit depletion (dark contrast) relative to the surrounding matrix. The orange arrows in Fig. 7a–d indicate the RIS phenomenon at a representative grain boundary. Further insight is provided by Fig. 7e, f, which shows the line profile analyses of elemental composition across two distinct grain boundaries, marked by blue and yellow dotted lines in Fig. 7a. The composition profiles confirm Ni and Co enrichment and Fe and Cr depletion at grain boundaries relative to the matrix, with the extent of elemental variation depending on the specific type of grain boundary. For instance, Fig. 7e indicates a higher degree of elemental segregation compared to Fig. 7f. The grain boundary with a misorientation of 45.7°, shown in Fig. 7e, demonstrates a Fe depletion of ~16.3 at%, whereas the grain boundary with a misorientation of 53°, shown in Fig. 7f, shows a lower Fe depletion of ~12.5 at%. Figure 7g–j displays the compositional maps for Ni, Co, Fe, and Cr, respectively, in the pristine region, and do not reveal any observable elemental segregation at the grain boundaries, indicating that the segregation is irradiation-induced. The Cr composition maps shown in Fig. 7d, j also reveal the presence of Cr3C7—type carbide precipitates, as indicated by the bright contrast. As a result, the Cr content in the NiCoFeCr matrix grains is reduced to ~15 at%, as observed at distances of around 30 nm on either side of the grain boundaries in Fig. 7e, f. Figure 8 describes the correlation between elemental segregation and grain boundary misorientation for 13 grain boundaries, including the boundaries shown in Fig. 7e, f. The plot reveals a gradual increase in the relative change in atomic % of segregated elements with increasing grain boundary misorientation angles, reaching a maximum at 45.7°. Beyond 45.7° misorientation angle, elemental segregation drops to lower values. At twin boundaries with a 60° misorientation, element segregation is significantly reduced and the boundary composition closely resembles that of the surrounding matrix.

The STEM-EELS compositional maps illustrate the distribution of the elements a Ni, b Co, c Fe, and d Cr from the irradiated region. e, f The plots describe the compositional variation at two of the grain boundaries, along the blue and yellow dotted lines, respectively, shown in (a). The STEM-EELS compositional maps also illustrate the distribution of the elements g Ni, h Co, i Fe, and j Cr from the pristine region.

Discussion

The mechanisms primarily responsible for hardening are source hardening and friction hardening36. Source hardening refers to the resistance to initiating dislocation motion on the glide plane, while friction hardening is associated with resistance to dislocation movement due to interactions with other dislocations and microstructural obstacles. The ODS-NiCoFeCr specimen is densely packed with pre-irradiation dislocations, exhibiting a dislocation length density of the order ~1014 m−2, along with microstructural barriers such as grain boundaries, carbide precipitates, and oxide nanoprecipitates, as shown in Fig. 4. Therefore, in the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy, hardening occurs primarily through friction hardening during nanoindentation, via dislocation interactions and impediments to dislocation motion at nanoprecipitates and grain boundaries. In contrast, the single-crystal NiCoFeCr sample exhibits hardening mainly due to source hardening and friction hardening through dislocation interactions, in the absence of significant microstructural obstacles such as grain boundaries and precipitates. Consequently, the pristine ODS-NiCoFeCr exhibited a significantly higher hardness of 5.70 + 0.54 GPa compared to 2.5 GPa for the single-crystal NiCoFeCr29. The dislocation pinning observed at the nanoprecipitates, represented by yellow arrows in Fig. 4, confirms the hardening of ODS-NiCoFeCr compared to single-crystal NiCoFeCr. Moreover, the hardness values of pristine FCC ODS-NiCoFeCr are comparable to or greater than those of various BCC ODS steel alloys, which are the prominent alloys for similar applications, as reported in the literature30,31,32,33. However, the large standard deviations in the nano hardness values, as shown in Fig. 2, are attributed to the wide range of oxide nanoprecipitate sizes observed in Fig. 6, since the precipitate sizes within the indentation region influence the hardness calculations. Furthermore, the E/H ratios of 42.1 ± 6.1 and 42.5 ± 6.2 for pristine and irradiated ODS-NiCoFeCr, respectively, are comparable to those of ultrafine-grained metal alloys (~36)37, indicating that irreversible deformation mechanisms dominate over elastic deformation, thereby implying good ductility and toughness.

The oxide nanoprecipitate-matrix interfaces, carbide precipitate-matrix interfaces, and grain boundaries act as sinks for interstitial and vacancy defects and thus, avoid the accumulation of the defects and their evolution to form extended defects such as voids and dislocations under irradiation. Additionally, NiCoFeCr alloys exhibit relatively higher lattice stiffness due to the chemical complexity and solid-solution strengthening, which further inhibits the formation of extended defects such as dislocations38. Upon 101 dpa irradiation at 580 °C, the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy did not exhibit the formation of additional microstructural features such as voids, dislocation loops, or irradiation-induced precipitates, as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. The irradiation-induced microstructural features contribute to swelling and hardening, which are the two major material degradation mechanisms during irradiation that are detrimental to the structural material applications of high-temperature irradiation. Although the average dislocation length density and mean dislocation length of the selected grains indicate a slight increase of 13% and slight decrease of ~20% upon irradiation, the nanohardness of the alloy remained largely unchanged. Thus, the ODS-NiCoFeCr showed no significant irradiation hardening, unlike single-crystal NiCoFeCr, which showed ~12% irradiation hardening under a similar irradiation fluence of 5 × 1016 ions/cm2 and at a slightly lower temperature of 500 °C29. In addition, even the coarse-grained NiCoFeCr demonstrated a 96% irradiation hardening rate with He-ion irradiation39. Although the irradiated single-crystal NiCoFeCr exhibits a lower dislocation length density compared to both pristine and irradiated ODS-NiCoFeCr, as mentioned in Table 1, the relative increase is substantial16, unlike in ODS-NiCoFeCr. All dislocations observed in the irradiated single-crystal NiCoFeCr are irradiation-induced due to the absence of defect sinks, unlike in ODS-NiCoFeCr. Moreover, the mean dislocation lengths in single-crystal NiCoFeCr16 are nearly twice as long as those in both irradiated and pristine ODS-NiCoFeCr, thereby contributing to irradiation hardening. In addition, the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy demonstrates better resistance to void formation and hardening compared to the BCC ODS-steel alloys40,41,42,43, which are among the prime candidates for advanced reactors.

The stability of nanostructures, such as grains and nanoprecipitates, is critical for the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy to serve as effective defect sinks and impart radiation resistance. Previous studies illustrated the destabilization of nanocrystalline grains through grain growth36,44,45. In the current research, ODS-NiCoFeCr exhibited a marginal increase of ~5 nm in mean grain size and evidence of the movement of grain boundaries under Ni2+ irradiation up to a fluence of 5 × 1016 ions/cm2 at 580 °C. Since the grains in irradiated ODS-NiCoFeCr, with a mean size of 59 + 2 nm, are mostly larger than the irradiation damage volume (~10 nm), the defect-simulated mechanism may drive grain growth44. According to the defect-simulated mechanism, large defect concentration gradients created by heavy ion irradiation near the grain boundaries cause atomic jumps across grain boundaries, resulting in their movement44. Oxide nanoprecipitates also showed similar behavior, undergoing minor coarsening by ~2 nm. Several studies reported the physical instability of precipitates under irradiation, leading to either increase or decrease in the precipitate densities and corresponding changes in mean precipitate size for various advanced reactor structural materials, depending on irradiation parameters such as dose, dose rate, and temperature18,46,47,48. In ODS-CSAs such as ODS-NiCoCr, shrinkage of nano oxides was detected under Ni2+ irradiation up to a fluence of 5 × 1016 ions/cm2 (up to 132 dpa) at 580 °C18. In the current study, the slight increase in the mean size of oxide precipitates in ODS-NiCoFeCr can be attributed to Ostwald ripening, where larger precipitates grow at the expense of smaller precipitates47. This occurs because atomic diffusion dominates over ballistic dissolution caused by damage cascades, indicating that the irradiation temperature of 580 °C exceeds the critical threshold temperature for the physical stability of the nanoprecipitates. Even though the nanostructures undergo slight coarsening, the grain boundaries and the oxide nanoprecipitate-matrix interfaces remained effective as defect sinks, thereby contributing to irradiation hardening and swelling resistance.

Earlier literature suggested the occurrence of RIS in NiCoFeCr alloys, revealing trends of Ni and Co enrichment and Fe and Cr depletion, consistent with the findings of the current work49,50,51. A previous study revealed Ni segregation around monovacancies at very early stages of irradiation damage (less than 1 dpa) in Fe-or Cr-containing SP-CSAs49. Also, another study reported RIS at dislocations in single-crystal NiCoFeCr, indicating lower segregation levels compared to other SP-CSAs such as NiFe and NiCoFe, under irradiation conditions similar to the current research but at a slightly lower temperature of 500 °C50. Similarly, a previous work described RIS at He bubbles following 275 keV He+ ions at 600 °C to a fluence of 5.14 × 1016 ions/cm2 51. However, researchers did not extensively study RIS at grain boundaries in SP-CSAs such as NiCoFeCr, particularly at very high dpa levels approaching 101 dpa as in the current research. In this work, as shown in Fig. 8, Ni exhibits greater enrichment than Co at the grain boundaries, with Ni segregation levels approximately double those of Co, regardless of the grain boundary misorientation. However, Fe and Cr show similar levels of depletion. The mechanism of this RIS effect can be explained using the vacancy-dominated inverse Kirkendall effect51, wherein vacancy migration towards the grain boundaries causes the movement of atoms away from the grain boundary. Since, the diffusivities of Cr and Fe are higher than the diffusivities of Ni and Co, Cr and Fe deplete more rapidly, resulting in relative enrichment of Ni and Co, despite all elements migrating away from the grain boundaries. Thus, a defect concentration gradient is established from the matrix towards the grain boundary, contributing to grain boundary movement and growth, as explained earlier by the defect-simulated mechanism. As shown in Fig. 8, the RIS effect reaches a maximum at a misorientation angle of ~45.7° and is minimized at lower misorientation angles (<30°) and special boundaries such as Σ3 twin boundary with a 60° misorientation. This indicates that special boundaries, such as twin boundaries, absorb fewer defects compared to random high-angle boundaries and therefore exhibit minimal chemical segregation. An earlier work reported segregation levels similar to those in the current work, even at a dose of just 2 dpa irradiation51. Furthermore, RIS is known to be associated with the suppression of void formation, due to the substantial migration of vacancies to grain boundaries while interstitials preferentially move towards the dislocations52.

One of the key performance-limiting concerns for materials exposed to elevated-temperature irradiation environments is the potential for irradiation creep. The RIS observed at grain boundaries in the current study suggests that a substantial fraction of point defects are absorbed at grain boundaries, thereby increasing the likelihood of irradiation creep. The proposed mechanism for irradiation creep in nanostructured alloys is grain boundary flow53. According to this mechanism, the local atomic density at grain boundaries changes due to the absorption of point defects, resulting in a relaxed state analogous to shear transformation zones in amorphous metals. This process facilitates grain boundary flow under applied stress53. Moreover, the model predicts that irradiation-induced creep compliance increases with decreasing grain size (d), following a 1/d dependence, unlike Coble and Nabarro-Herring creep mechanisms, which exhibit stronger grain size dependencies of 1/d³ and 1/d², respectively53. Experimental studies have shown that nanocrystalline NiCoCrFeMn and Cu-W alloys exhibit creep compliance values up to an order of magnitude lower than those of coarse-grained counterparts, which primarily undergo dislocation-based creep54,55. Furthermore, nanocrystalline materials with grain sizes larger than the irradiation cascade size, such as those in the current study, demonstrate at least an order of magnitude lower creep compliance compared to materials with grain sizes below the cascade size, which approach the amorphous limit54. Moreover, the material investigated in the present study, ODS-NiCoFeCr, contains additional defect sinks in the form of oxide nanoprecipitates and carbide precipitates, which reduce the number of irradiation-induced defects migrating to the grain boundaries.

To summarize, the nanostructures present in ODS-NiCoFeCr, namely oxide nanoprecipitates, grain boundaries, and Cr₃C₇-type carbide precipitates, contribute to an effective two-fold increase in hardness compared to single-crystalline NiCoFeCr. Upon Ni²⁺ irradiation at 580 °C to a peak damage level of 101 dpa, the alloy exhibited minimal changes in nanoindentation hardness and elastic modulus, indicating a high degree of irradiation-induced hardening resistance. This behavior was supported by microstructural analyses, which revealed volume-averaged dislocation length densities on the order of ~1014 m−2 and only a minor decrease in the mean dislocation length from 89 nm to 71 nm post-irradiation. Moreover, the alloy exhibited excellent swelling resistance, with no observable voids, which is attributed to the efficient absorption of irradiation-induced defects at the densely distributed sinks provided by the nanostructures. The nanostructures themselves remained largely stable under irradiation, with only slight increases in nanoprecipitate and grain sizes (~2 nm and ~5 nm, respectively). The RIS at the grain boundaries was also relatively modest when compared to other multicomponent and steel alloys. Among the thirteen grain boundaries analyzed, the extent of RIS varied with the misorientation angle, with the highest level observed at a boundary exhibiting a misorientation angle of 45.7°. These findings underscore the effectiveness of the nanostructured medium-entropy alloy design in offering a high density of defect sinks, thereby supporting its potential for high-temperature irradiation applications and motivating further investigations.

Methods

Sample preparation and irradiation

The ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy was manufactured with a nominal chemical composition of NiCoFeCr (1:1:1:1)—0.32 wt% Ti—1.5 wt% (Y2O3 + ZrO2) via mechanical alloying using ball milling, followed by spark plasma sintering and subsequent annealing. The synthesis process was carried out at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK), USA. Detailed procedures are available in Guo et al.22,23. The samples were then sectioned into ~5 mm × 5 mm × 2 mm and polished to achieve a mirror-like finish. Consequently, Ni2+ ion irradiation was conducted at 580 °C on selected regions of the samples at the Ion Beam Materials Laboratory, UTK52, as described by Jin et al.29. The irrdiation utilized an energy of 3 MeV to a fluence of 5 × 1016 ions/cm256. The SRIM simulations were employed to estimate the irradiation-depth profile as shown in Fig. 1. The calculations were performed with a target density of 8.553 g/cm3 utilizing a threshold displacement energy of 40 eV for Ni, Co, Fe, and Cr according to the ASTM standard57. The lattice binding energies used were 5.9 eV, 4.6 eV, 5.8 eV, and 7.8 eV for Ni, Co, Fe, and Cr, respectively, as reported by Agarwal et al.58. To avoid overestimating vacancy production, the final cut-off energy in the SRIM calculations was modified from the default 1 eV to 40 eV (threshold displacement energy)59. The dpa calculations were conducted based on the VACANCY.TXT method59.

Nanoindentation

Nanoindentation was performed to evaluate the local hardness of the ODS-NiCoFeCr sample in both the irradiated and pristine regions using the NanoTest Vantage system (platform 3) equipped with a Berkovich indenter. The nanoindentation experiments utilized hold times of 1.2 s and 2.2 s at the maximum load for the irradiated and pristine regions, respectively. Hardness was measured using the relationship H = Pmax/Ap, where Pmax is the maximum load and Ap is the projected area of the indentation. For indentation in the irradiated region, data were collected from a depth of ~150 nm, equivalent to about 10% of the irradiation depth (top 1.5 µm—Fig. 1), to ensure that the plastic deformation induced by indentation was confined within the irradiated region. To determine the appropriate load meeting this criterion, a series of indents with loads ranging from 1 mN to 10 mN were performed. As a result, a load of 2 mN was selected to assess irradiation hardening in both pristine and ion-irradiated samples. To minimize indentation size effects (ISE), the Diamond Area Function of the indenter for the 2 mN load and a polynomial describing the shape of the indenter were calculated60 at the corresponding depth. In addition, it was assumed that both the pristine and ion-irradiated regions of the sample experienced similar, though minimal, ISE. Furthermore, the elastic moduli of the pristine and irradiated samples were calculated from the nanoindentation data following the method described in Yang et. al.61. For these calculations, the Poisson’s ratio and elastic modulus of the diamond indenter were taken as 0.07 and 1140 GPa, respectively61. The Poisson’s ratio of the ODS-NiCoFeCr alloy was assumed to be 0.2662.

TEM sample preparation

A dual-beam scanning electron microscope/focused ion beam Helios 5 UX (Thermo Fisher Scientific), equipped with EasyLift™, was utilized to mill, cut, lift out, and prepare electron-transparent lamellae from the irradiated regions of ODS-NiCoFeCr sample for TEM studies. During lamellae preparation, a layer of carbon protection was deposited, and cuts were made to a depth of at least ~4 µm. Thus, the lamellae included both the irradiated (top 1.5 µm—Fig. 1) and pristine regions. For final thinning of the lamellae, the acceleration voltage of the beam was reduced to 2 kV to minimize damage caused by Ga+ ions.

TEM characterization

Several TEM instruments and techniques were used to investigate features such as voids, dislocation lines, and oxide nanoprecipitates, and obtain crystallographic orientation maps and chemical compositional maps in the ODS-NiCoFeCr lamellae. A 200 kV—FEI TalosTM F200X FEG (S)TEM microscope was employed to reveal dislocations in the irradiated and pristine regions of the lamellae. The lamellae were tilted to multiple angles to achieve STEM two-beam conditions with g-vectors {200} and {220} for various grains. Additionally, a coldFEG, probe and image spherical aberration corrected, JEOL ARM 200CF microscope, operated at 200 kV, was utilized to conduct STEM-EELS for identifying nanoprecipitates in both the irradiated and pristine regions of ODS-NiCoFeCr. STEM-EELS compositional maps were used to calculate nanoprecipitate density and sizes using ImageJ software63. STEM-EELS was also employed to determine the thickness of the regions of interest within the lamellae, facilitating nanoprecipitate density calculations. Furthermore, a JEOL 2100F microscope equipped with a SPED set-up was used to conduct orientation mapping via ASTAR in the irradiated and pristine regions of ODS-NiCoFeCr. The diffraction data for the matrix phase, NiCoFeCr, were indexed, and orientation mapping was carried out using NanoMegas ASTAR64. This study represents one of the earliest efforts to demonstrate the viability of this novel approach for microstructural characterization of nuclear materials. The orientation maps were subsequently analyzed using the MTEX MATLAB software65 to evaluate grain size, misorientation distribution, and grain orientation spread in the grains, providing insights into the physical stability of the nano-sized grains.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data related to the findings of this study are available within the paper and any other supporting data could be provided by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, Y., Osetsky, Y. N. & Weber, W. J. Tunable chemical disorder in concentrated alloys: defect physics and radiation performance. Chem. Rev. 122, 789–829 (2022).

Yeh, J. W. et al. Nanostructured high-entropy alloys with multiple principal elements: novel alloy design concepts and outcomes. Adv. Eng. Mater. 6, 299–303 (2004).

Ye, Y. F., Wang, Q., Lu, J., Liu, C. T. & Yang, Y. High-entropy alloy: challenges and prospects. Mater. Today 19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2015.11.026 (2016).

Zhang, Y., et al. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 61, 1–93 (2014).

Levo, E., Granberg, F., Fridlund, C., Nordlund, K. & Djurabekova, F. Radiation damage buildup and dislocation evolution in Ni and equiatomic multicomponent Ni-based alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 490, 323–332 (2017).

Yang, L. et al. Deformation mechanisms in single crystal Ni-based concentrated solid solution alloys by nanoindentation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 856, 143685 (2022).

Lach, T. G. et al. Dynamic substrate reactions during room temperature heavy ion irradiation of CoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloy thin films. npj Mater. Degrad. 6, 60 (2022).

Pickering, E. J. et al. High-entropy alloys for advanced nuclear applications. Entropy 23, 1–28 (2021).

Aguiar, J. A., Jokisaari, A. M., Kerr, M. & Allen Roach, R. Bringing nuclear materials discovery and qualification into the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16406-2 (2020).

Zhang, Y. Reassembled nanoprecipitates resisting radiation. Nat. Mater. 22, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01283-5 (2023).

Zinkle, S. J. & Busby, J. T. Structural materials for fission & fusion energy. Mater. Today 12, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1369-7021(09)70294-9 (2009).

Kombaiah, B. et al. Nanoprecipitates to enhance radiation tolerance in high-entropy alloys. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 3912–3924 (2023).

He, M. R. et al. Mechanisms of radiation-induced segregation in CrFeCoNi-based single-phase concentrated solid solution alloys. Acta Mater. 126, 182–193 (2017).

Zhao, S., Chen, D. & Kai, J. J. First-principles study of He behavior in a NiCoFeCr concentrated solid–solution alloy. Mater. Res. Lett. 7, 188–193 (2019).

Fan, Z. et al. Diffusion-mediated chemical concentration variation and void evolution in ion-irradiated NiCoFeCr high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Res. 36, 298–310 (2021).

Fan, Z. et al. From suppressed void growth to significant void swelling in NiCoFeCr complex concentrated solid-solution alloy. Materialia 9, 100603 (2020).

Zhao, S., Zhang, Y. & Weber, W. J. Engineering defect energy landscape of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloys by the introduction of additional dopants. J. Nucl. Mater. 561, 153573 (2022).

Lu, C. et al. High radiation tolerance of an ultrastrong nanostructured NiCoCr alloy with stable dispersed nanooxides and fine grain structure. J. Nucl. Mater. 557, 153316 (2021).

Esfandiarpour, A., Feghhi, S. A. H. & Shokri, A. A. Effects of atomic grain boundary structures on primary radiation damage in α-Fe. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 362, 1–8 (2015).

Du, C. et al. Ultrastrong nanocrystalline steel with exceptional thermal stability and radiation tolerance. Nat. Commun. 9, 5389 (2018).

Li, M., Guo, Y., Li, W., Zhang, Y. & Chang, Y. Property enhancement of CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy by introducing nano-scale features. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 817, 141368 (2021).

Guo, Y. et al. Microstructure and mechanical properties of oxide dispersion strengthened FeCoNi concentrated solid solution alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 820, 153104 (2020).

Guo, Y. et al. Oxide dispersion strengthened FeCoNi concentrated solid-solution alloys synthesized by mechanical alloying. Intermetallics 117, 106674 (2020).

Hadraba, H. et al. Oxide dispersion strengthened CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 689, 252–256 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Unveiling deformation behavior and damage mechanism of irradiated high entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 196, 71–87 (2024).

Moghadasi, M. A., Nili-Ahmadabadi, M., Forghani, F. & Kim, H. S. Development of an oxide-dispersion-strengthened steel by introducing oxygen carrier compound into the melt aided by a general thermodynamic model. Sci. Rep. 6, 38621 (2016).

Wu, Z. F. et al. Significant suppression of void swelling and irradiation hardening in a nanograined/nanoprecipitated 14YWT-ODS steel irradiated by helium ions. J. Nucl. Mater. 559, 153418 (2022).

Weber, W. J. & Zhang, Y. Predicting damage production in monoatomic and multi-elemental targets using stopping and range of ions in matter code: challenges and recommendations. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 23, 100757 (2019).

Jin, K. et al. Effects of compositional complexity on the ion-irradiation induced swelling and hardening in Ni-containing equiatomic alloys. Scr. Mater. 119, 65–70 (2016).

Wyszkowska, E. et al. Investigation of the mechanical properties of ODS steels at high temperatures using nanoindentation technique. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. with Mater. Atoms 444, 107–111 (2019).

Frelek-Kozak, M. et al. Mechanical behavior of ion-irradiated ODS RAF steels strengthened with different types of refractory oxides. Appl. Surf. Sci. 610, 155465 (2023).

Das, A. et al. Microstructural characterization of inhomogeneity in 9Cr ODS EUROFER steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 533, 152083 (2020).

Diao, S. Z. et al. The microstructure evolution and irradiation hardening in 15Cr-ODS steel irradiated by helium ions. Mater. Charact. 184, 111699 (2022).

Cui, L. J. et al. TEM characterization of irradiation-induced dislocation loops and voids in ion-irradiated pure chromium. J. Nucl. Mater. 569, 153920 (2022).

Holm, E. A., Hassold, G. N. & Miodownik, M. A. On misorientation distribution evolution during anisotropic grain growth. Acta Mater. 49, 2981–2991 (2001).

Was, G. S. Fundamentals of radiation materials science: Metals and alloys, second edition. Fundamentals of Radiation Materials Science: Metals and Alloys 2nd edn. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-3438-6 (2016).

Yan, C. et al. Nanoindentation of supercrystalline nanocomposites: linear relationship between elastic modulus and hardness. JOM 74, 2261–2276 (2022).

Mieszczynski, C. et al. Defect evolution in Ni and solid-solution alloys of NiFe and NiFeCoCr under ion irradiation at 16 and 300 K. J. Nucl. Mater. 534, 152138 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. NiCoCr-based medium-entropy alloys with superior resistance to radiation hardening and helium cavity growth. J. Nucl. Mater. 574, 154196 (2023).

Duan, B. et al. The effect of the initial microstructure in terms of sink strength on the ion-irradiation-induced hardening of ODS alloys studied by nanoindentation. J. Nucl. Mater. 495, 118–127 (2017).

Ding, Z. N. et al. Hardening of ODS ferritic steels under irradiation with high-energy heavy ions. J. Nucl. Mater. 493, 53–61 (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Microstructural changes and void swelling of a 12Cr ODS ferritic-martensitic alloy after high-dpa self-ion irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 467, 42–49 (2015).

Li, F. et al. Microstructure evolution and void swelling of ODS ferritic/martensitic steel under high damage irradiation. Mater. Charact. 205, 113272 (2023).

Bufford, D. C., Abdeljawad, F. F., Foiles, S. M. & Hattar, K. Unraveling irradiation induced grain growth with in situ transmission electron microscopy and coordinated modeling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 191901 (2015).

Zhou, J., Islam, M. I., Guo, S., Zhang, Y. & Lu, F. Radiation-induced grain growth of nanocrystalline alxcocrfeni high-entropy alloys. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 3509–3516 (2021).

Nori, S. T. et al. 4D evolution of Cr23C6 precipitates in neutron-irradiated and annealed HT-UPS steel observed via synchrotron micro-computed tomography. J. Mater. Res. 37, 208–224 (2022).

Ribis, J. et al. Nano-structured materials under irradiation: oxide dispersion-strengthened steels. Nanomaterials 11, 2590 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. Temperature dependent dispersoid stability in ion-irradiated ferritic-martensitic dual-phase oxide-dispersion-strengthened alloy: Coherent interfaces vs. incoherent interfaces. Acta Mater. 116, 29–42 (2016).

Tuomisto, F. et al. Segregation of Ni at early stages of radiation damage in NiCoFeCr solid solution alloys. Acta Mater. 196, 44–51 (2020).

Lu, C. et al. Radiation-induced segregation on defect clusters in single-phase concentrated solid-solution alloys. Acta Mater. 127, 98–107 (2017).

Lin, W. T. et al. He-enhanced heterogeneity of radiation-induced segregation in FeNiCoCr high-entropy alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 101, 226–233 (2022).

Barr, C. M. et al. Exploring radiation induced segregation mechanisms at grain boundaries in equiatomic CoCrFeNiMn high entropy alloy under heavy ion irradiation. Scr. Mater. 156, 80–84 (2018).

Ashkenazy, Y. & Averback, R. S. Irradiation induced grain boundary flow—a new creep mechanism at the nanoscale. Nano Lett. 12, 4084–4089 (2012).

Jawaharram, G. S. et al. Irradiation induced creep in nanocrystalline high entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 182, 68–76 (2020).

Tai, K., Averback, R. S., Bellon, P. & Ashkenazy, Y. Irradiation-induced creep in nanostructured Cu alloys. Scr. Mater. 65, 163–166 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. New ion beam materials laboratory for materials modification and irradiation effects research. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 338, 19–30 (2014).

ASTM Standard E521-16. Standard Practice for Investigating the Effects of Neutron Radiation Damage Using Charged-Particle Irradiation. In Annual Book of ASTM Standards. Vol. 12, 1-21 (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2016) https://doi.org/10.1520/E0521-16.

Agarwal, S., Lin, Y., Li, C., Stoller, R. E. & Zinkle, S. J. On the use of SRIM for calculating vacancy production: Quick calculation and full-cascade options. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 503, 11–29 (2021).

Lin, Y. R. et al. Predicting displacement damage for ion irradiation: origin of the overestimation of vacancy production in SRIM full-cascade calculations. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 27, 101120 (2023).

Qiao, X. G., Starink, M. J. & Gao, N. The influence of indenter tip rounding on the indentation size effect. Acta Mater. 58, 3690–3700 (2010).

Yang, L. et al. Nanoindentation study on early-stage radiation damage in single-phase concentrated solid solution alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 908, 146746 (2024).

Ali, M.dL., Haque, E. & Rahaman, M.dZ. Pressure- and temperature-dependent physical metallurgy in a face-centered cubic NiCoFeCrMn high entropy alloy and its subsystems. J. Alloy. Compd. 873, 159843 (2021).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019 (2012).

Rauch, E. F. et al. Automated nanocrystal orientation and phase mapping in the transmission electron microscope on the basis of precession electron diffraction. Z. Krist. 225, 103–109 (2010).

Nolze, G. & Hielscher, R. Orientations—perfectly colored. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 49, 1786–1802 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 857470 and from the European Regional Development Fund via Foundation for Polish Science International Research Agenda PLUS program Grant No. MAB PLUS/2018/8 and the initiative of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education “Support for the activities of Centers of Excellence established in Poland under the Horizon 2020 program” under agreement No. MEiN/2023/DIR/3795. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 823717—ESTEEM3. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 EURATOM Programme under grant agreement No. 10106008 via the OFFERR project. Y.Z. is supported through the CANADA EXCELLENCE RESEARCH CHAIRS (CERC) program. The authors acknowledge the computational resources provided by the High-Performance Cluster at the National Centre for Nuclear Research in Poland. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T.N. conceptualized the study, conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the original manuscript. P.F., D.K., R.B., P.E.V., K.M., W.C., M.L., and Y.C. conducted the experiments. Y.Z. conceptualized the study, acquired funding, provided the resources, and administered the project. R.H. provided the resources. L.K. conceptualized the study, acquired funding, provided the resources, supervised, and administered the project. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nori, S.T., Ferreirós, P.A., Kalita, D. et al. Nanostructured NiCoFeCr alloy with superior high-temperature irradiation resistance. npj Mater Degrad 9, 91 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00642-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00642-2