Abstract

Temporal succession of active and total microbial communities driving microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) on copper-nickel (CuNi) 90/10 and titanium (Ti) exposed to natural seawater over 16 weeks was investigated. Electrochemical analysis revealed increasing corrosion resistance of CuNi until 12 weeks, but showed corrosion signs at 16 weeks; Ti exhibited steadily increasing corrosion resistance. Raman spectroscopy confirmed unprotective cupric oxide (CuO) and hydroxide (Cu(OH)₂) presence on CuNi, while Ti maintained protective TiO₂. Pitting analysis identified pits on CuNi but none on Ti. Next-generation sequencing of complementary and genomic DNA identified Halomonas and Marinobacter as early colonizers on CuNi, and increasing species diversity over time. Ti exhibited decreasing diversity, with Aestuariibacter, Methylophaga, and predatory bacteria as early colonizers. Sulfate-reducing and acid-producing bacteria initially showed a declining trend on CuNi but increased from 12 weeks, indicating increased MIC susceptibility; they remained less/undetectable on Ti. Overall, findings highlight the role of early colonizers in driving MIC and distinct microbial succession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corrosion presents a major global challenge, with an estimated economic impact of around 3.4% global Gross National Product, equating to $2.9 trillion in 20181,2. In marine environments, microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) caused by microfouling organisms significantly contributes to material degradation3. These organisms, including bacteria, archaea, fungi, and microalgae4, adhere to metal surfaces and form biofilms of microbial cells and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS), and can create corrosion rates one to two orders of magnitude higher than abiotic corrosion, posing a significant threat to the structural integrity and economic stability of marine infrastructure, industrial facilities, and transportation systems worldwide5.

MIC impacts various industrial systems and marine structures, including drinking water and sewer networks, oil and gas pipelines, heat exchangers, and aviation fuel tanks, contributing to ~20% of corrosion losses in aqueous environments6. In marine settings, microbial biofilms can create a distinctive microenvironment enabling reactions that are not anticipated by thermodynamic interpretations of the surrounding medium7. While bacteria are considered primary MIC contributors, with sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and acid-producing bacteria (APB) identified as key causative agents8,9, most studies focus on single-strain mechanisms that do not fully capture the complexity of microbial interactions within biofilms. For instance, apart from SRB and bacteria involved in the reduction of thiosulfate to sulfide, sulfate-reducing archaea have also been reported to produce sulfide9. Furthermore, filamentous fungi are widely distributed in marine environments and have shown resistance to high concentrations of copper10, a material of particular interest for this study, yet were underexplored for their contribution to MIC11. Therefore, exploring all microbial contributors from three domains of life is necessary to fully understand the MIC mechanisms and complex microbial interactions.

MIC can take place under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions, driven by various mechanisms12,13. In general, anaerobic MIC, such as in stagnant water where oxygen is limited and maybe intermittently available or consumed by microorganisms, is considered more economically damaging, and extensive research to explore its mechanistic aspects were mostly carried out on Fe-based alloys, with mechanisms including extracellular electron transfer (EET-MIC) and metabolite MIC (M-MIC) being widely reported14. Although recent studies support M-MIC as a more plausible corrosion mechanism for copper and its alloys15,16, these study models are single SRB strain-induced MIC mechanisms. Therefore, identifying all microbial contributors of corrosion on copper and its alloys has significant potential for developing and testing MIC mechanism models that can more accurately replicate real-world conditions. Currently, next-generation sequencing methods including targeted sequencing (16S/18S amplicon sequencing) are widely used for analysing microbial communities involved in MIC17. Recent advancements with primer sets have improved the amplification of small subunit (SSU) rRNA genes across bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes, facilitating broader microbial detection18,19. Additionally, complementary DNA/RNA-based amplicon sequencing offers superior accuracy in identifying active microbial community members compared to traditional 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Recent MIC research on carbon steel found a stronger correlation between corrosion characteristics and active microflora than with total cell counts from conventional methods, thereby enhancing the understanding of the microbial communities involved in corrosion20.

Copper and its alloys are widely used in marine environments for structures such as heat exchangers, ship piping systems, and offshore installations such as power plants21. Titanium and its alloys are widely employed in the aerospace industry, medical and dental applications, as well as marine and offshore infrastructures due to their superior corrosion resistance, high strength-to-weight ratio, and notable biocompatibility22. Although titanium exhibits significant corrosion resistance, copper and its alloys are reported to have more MIC issues11,21. In general, copper and its alloys are resistant to microbial growth due to their antimicrobial properties23. However, studies demonstrate that selective microorganisms have evolved mechanisms to survive copper toxicity, including copper-binding proteins in EPS that facilitate corrosion24. SRBs are regarded as key MIC contributors in anaerobic environments, but mechanistic insights are mainly based on single-strain studies5,15. In real-world aerobic conditions, SRBs require interactions with other microorganisms that colonize on copper or its alloys and provide a conducive anaerobic microenvironment. Therefore, identifying initial colonizers along with the temporal succession of key microbial contributors to corrosion on copper or its alloys, is crucial for developing accurate MIC models. To the best of our knowledge, such studies were not carried out on copper and its alloys so far, despite some field studies analysing the microbial communities of mature biofilms11. Moreover, there has been minimal data on the correspondence between results obtained from electrochemical and microbiological assays for MIC on metal surfaces. In this regard, this study primarily aimed at characterizing the temporal succession and diversity of total (includes dead cells, resting cells, and extracellular DNA) and metabolically active microfouling communities and their corrosion behavior on Copper-Nickel (CuNi) 90/10 and Titanium (Ti) (Grade 2) metals exposed to natural seawater under stagnant conditions for a time period of 16 weeks. The specific objectives include, (1) to investigate the electrochemical behavior and corrosion resistance of CuNi and Ti metals under stagnant seawater conditions, (2) to characterize the morphological features and composition of biofilms and corrosion products formed on metal surfaces, and (3) to elucidate the microbial diversity, and temporal succession patterns of microfouling communities on the tested metals, along with functional genes for copper resistance and biofilm formation. Electrochemical techniques including open circuit potential (OCP), linear polarization resistance (LPR), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were used to provide quantitative measurements of corrosion susceptibility and biofilm influence on metal surfaces. Surface characterization methods included Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for biofilm and corrosion morphology assessment, Raman spectroscopy for corrosion product identification, and optical profilometry and SEM for pitting analysis. Microbial analysis employed quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for quantification of Cu tolerance and biofilm formation genes, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) to track temporal succession of both total and metabolically active microfouling communities. This multi-technique approach provides novel insights into the initial microflora associated with Cu resistance during initial biofilm formation involved in MIC and subsequent corrosion dynamics, establishing a clear link between biofilm growth and electrochemical behavior of the metal surfaces. Furthermore, this study provides one of the first systematic evaluations of the temporal dynamics of metabolically active and total microflora involved in the biofilm formation on CuNi and Ti metals through the analysis of both DNA- and RNA-based microbial communities, which is vital for the comprehensive understanding of MIC mechanisms on these metals but has not been thoroughly investigated.

Results

OCP and LPR measurements of CuNi and Ti metals

CuNi exhibited an initial increase in OCP to below −100 mV vs. Ag/AgCl (mVSSC) after 1 week of exposure, but subsequently demonstrated a declining trend and reached −234.4 mV after 16 weeks (Table 1 and Fig. S2), suggesting an increased susceptibility to corrosion. Similarly, although there is a notable decrease in current density (icorr) to 1.2 µA/cm2 and an increase in polarization resistance (Rp) values to 2.4 × 104 Ω cm2 after 12 weeks, an increase in icorr to 6.1 µA/cm2 and a reduction in Rp to 7.4 × 103 Ω cm2 at 16 weeks suggest an increased level of corrosion in CuNi samples. In contrast, Ti demonstrated superior corrosion resistance compared to CuNi. The OCP of Ti shifted steadily in the positive direction from around −341 mVSSC to +130 mVSSC, indicating ennoblement of the surface over time. Similarly, icorr remained extremely low and stable, decreasing from 107 nA/cm2 to 34.2 nA/cm2, while Rp values increased from 2.35 × 105 Ω cm2 to 7.65 × 105 Ω cm² after 16 weeks of exposure, reflecting minimal corrosion activity on Ti surfaces.

EIS of CuNi and Ti metals

The EIS spectra generated for CuNi and Ti metals exposed to natural seawater for 16 weeks at 25 oC under stagnant conditions are presented as Nyquist and Bode plots (Fig. 1). The diameters of the semicircle (capacitive arc) in the Nyquist plot for CuNi (Fig. 1A) increased over the initial 12 weeks, indicating an increase in charge transfer resistance (Rct) in seawater, but significantly decreased at 16 weeks, reflecting a reduction in Rct. Similarly, the Bode plots indicate that the total impedance of CuNi (Fig. 1B) increased during the first 12 weeks and then underwent a notable decline at 16 weeks. The reduction in Rct and total impedance of CuNi at 16 weeks suggests a partial degradation or thinning of the passive layer. In contrast, Ti exhibited significantly higher and constant semicircle diameters in Nyquist plots (Fig. 1D) and stable total impedance in Bode plots over 16 weeks (Fig. 1E), indicating exceptionally stable and protective passive behavior. The phase angle behavior correlates with the previous observations. For CuNi (Fig. 1C), the phase angle values stay above −70o with presence of multiple inflection points, which is characteristic of a defective non-uniform layered passive film composed of an inner compact layer and an outer porous layer. Ti exhibits a high phase angle plateau near −80 to −90o (Fig. 1F), indicating the presence of a stable, uniform, and protective passive film.

The Nyquist plots (Fig. 1A, D) show a semicircle characteristic of a charge transfer control process, while the phase angle plots (Fig. 1C, F) display two-time constants at medium and low frequencies, indicating porous passive layers on both metals, with the Ti layer being more protective than CuNi. Consequently, the equivalent circuit model for EIS data fitting (Fig. S3) included a two-time constant associated with surface film formation and charge transfer processes25. In the equivalent circuit model, Q represents the constant phase element (CPE), which is used to model the non-ideal behavior of the system and can be calculated from the equation described by Chen et al.26. Rs, Rf, and Rct represent the solution resistance, the resistance of the surface film, and the charge transfer resistance of the electrical double layer, while Qf and Qdl represent the CPEs related to the film layer and the electric double layer, respectively. The fitting quality of the model was evaluated through the chi-square (χ2) value, which measures the fitting accuracy, which was found to be in the order of 10−3 or below, indicating a good fit. The fitted parameters obtained from the EIS data of CuNi and Ti are summarized in Table 2.

The EIS findings for CuNi reveal a dynamic change in surface properties, suggesting a developing, but unstable passive film. The low Rs indicates minimal interference from the electrolyte. The film capacitance (Yf) and film exponent (nf) values notably increased over time, reaching their maximum at 12 weeks, which indicates the development of a more capacitive and relatively uniform surface film. However, the fluctuations in Rf, reaching a peak of 29.5 × 102 Ω cm2 at 8 weeks and declining at 16 weeks, suggest a partial deterioration or thinning of the passive layer. The Rct, which is a critical measure of corrosion resistance, significantly increases from 3.9 kΩ cm2 at 2 weeks to 54.8 kΩ cm2 at 12 weeks, demonstrating enhanced corrosion resistance through passivation, but the subsequent decrease to 18.5 kΩ cm2 at 16 weeks suggests possible degradation or porosity development in the passive layer, potentially exposing the metal to localized corrosion. The initial rise and subsequent decline of double-layer capacitance (Ydl) also suggest the development and eventual degradation of a protective oxide layer. In contrast, Ti demonstrated a remarkably stable and protective passivation behavior during the entire exposure period. The film parameters (Yf and nf) indicate the presence of a dense, compact, and stable film, with nf values remaining close to 0.85–0.87, which indicates a highly capacitive and homogeneous oxide layer with minimal imperfections. The Rf initially remains low but significantly increases, reaching a highest of 90.8 × 102 Ω cm2 at 16 weeks, indicating continuous thickening and improvement of the passive film. Consistently, the Rct values are significantly high, ranging from 1187.2 to 2103.5 kΩ cm2, indicating superior corrosion resistance. The consistently high ndl values (>0.95) further demonstrate the existence of a stable and compact double layer. Over all, when Rf and Rct values are combined to compare total corrosion rate trends (Fig. S4), the Ti values significantly surpass those of CuNi, highlighting its capacity to maintain its passivation state even with extended exposure.

Biofilm morphology and corrosion products composition

The temporal succession of biofilm growth on CuNi and Ti metals during natural seawater exposure for 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks under stagnant conditions at 25 oC is presented in Figs. S5 and S6, respectively and a comparison of biofilm morphology formed on CuNi and Ti metals after 16 weeks of exposure is shown in Fig. 2. After 2 weeks of exposure, the biofilms on CuNi were predominantly in the early stages of development, with only a few clusters showing features of mature biofilms, such as elevated EPS levels and microbial density (Fig. S5). Over the period of 2 to 16 weeks, biofilm growth on CuNi surfaces significantly increased, resulting in denser and more mature biofilm structures. A higher magnification of a biofilm cluster (Fig. 2 and Fig. S5) revealed the presence of rod- and cocci-shaped bacteria wrapped with EPS and fungal hyphae-like structures. Overall, biofilm formation significantly altered the original state of the CuNi surface. In contrast, no biofilm structures were observed on Ti after 2 weeks of exposure, although individual bacteria were present. Microbial aggregation started only after 4 weeks and appeared to form more visible clusters after 12 weeks (Fig. S6). The higher magnification of these biofilms revealed microbial structures resembling fungal hyphae or filamentous bacteria (Fig. 2). Overall, biofilms formed on CuNi exhibited significantly more growth compared to Ti, with notable differences in microbial structures between the two metals.

Images from the top row (A–D) represent CuNi metal coupons with biofilms at different magnifications. Images from the bottom row (E, F) represent Ti metal coupons with biofilms at different magnifications. The yellow, red, and black arrows in image (D) indicate rod-shaped bacteria, cocci-shaped bacteria, and EPS, respectively. White arrow marks in the images (G, H) represent filamentous bacteria or fungal hyphae-like structures.

Raman spectroscopy was performed to investigate the corrosion products and biofilm composition of CuNi and Ti metals (Fig. 3). Raman spectra for CuNi demonstrated a higher presence of protective cuprous oxide (Cu2O) with peaks at 151 and 636 cm-127,28 during the initial exposure stages (2 and 4 weeks, Fig. 3A), along with the detection of unprotective cupric oxide (CuO) at 511 cm−129 and hydroxide (Cu(OH)2) at 292 and 488 cm−1 27. The reduced detection of protective Cu2O at 16 weeks may be due to increased biofilm formation, as indicated by higher levels of protein and DNA structures (785–1093 cm−130). Furthermore, Raman spectra identified the presence of CuCl (peak at 1079 cm−1), γ-FeOOH (peaks at 250 and 349 cm−1), ᾳ-FeOOH (peak at 392 cm−1), and NiO (peak at 735 cm−1) in the biofilms, suggesting changes in the corrosion products over time. Throughout the exposure, Ti exhibited detection of the protective TiO2, specifically Rutile at 127 cm−1 and Brookite at 241 cm−1 (Fig. 3B). Protein and DNA structures were found to be minimal on the Ti surface, indicating reduced biofilm formation, which suggests that Ti has a more stable and protective oxide layer in comparison to CuNi.

Pitting corrosion morphology analysis

The pitting morphology on CuNi and Ti metals was analysed after removing the biofilms and corrosion products using an optical profilometer (Fig. S7) and SEM (Fig. 4). The results indicated corrosion on CuNi after 16 weeks and showed a maximum depth of 5.8 µm (Fig. S8), and the area of the largest pit is 294.2 µm2 (Fig. S7). The SEM image of the CuNi surface after 16 weeks of exposure shows a relatively smooth appearance (Fig. 4A), although the formation of pits was more distinctly observed at higher magnification. The pits are relatively shallow and sparse, but they indicate localized corrosion. After 16 weeks, the Ti coupon revealed minor pits with depth recorded below 2 µm, indicating insignificant pits (Fig. S8). The SEM image of the Ti surface reveals a relatively smooth appearance, with no detectable pits, indicating that Ti is less susceptible to corrosion compared to CuNi under identical conditions (Fig. 4B). No visible pits were observed at higher magnification, demonstrating that Ti has excellent corrosion resistance in seawater under the conditions tested.

Quantification of Functional Genes for Cu Resistance and Biofilm Formation

The absolute abundance of 16S rRNA gene, and functional genes for Cu resistance and biofilm formation detected in the biofilms of CuNi is presented in Fig. S9. The 16S rRNA gene marker, which serves as a marker for total bacterial/archaeal and fungal abundance, remained relatively constant throughout the 16-week exposure period, suggesting stable microbial abundance. The Cu resistance genes, copA and cusA, exhibited a pattern similar and varied over time, with peaking at 4 and 16 weeks. The increase in copA,and cusA gene copies likely reflects the microbial community’s response to the biofilm’s heavy metal stress to copper. The DG-1 and DG-2 genes, which are associated with biofilm formation, exhibited distinct pattern. The DG-2 gene followed a similar trend to copA and cusA, suggesting they might have originated from the same specific microorganisms that thrive in the biofilm environment and have adapted to the conditions created by exposure to CuNi metal. DG-1 gene, however, did not follow a similar pattern and was relatively less abundant.

Total (gDNA) and active (cDNA) microfouling communities on CuNi and Ti metals

A total of 20 samples (ten samples for each of CuNi and Ti, including cDNA and gDNA extracted at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks) were sequenced and analyzed for microbial community composition by NGS. In total, 8,047,425 sequence reads were generated for bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA and fungal/eukaryotic 18S rRNA present in the cDNA and gDNA of CuNi and Ti samples. The rarefaction curves resulting from the total count of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) using normalized sequence reads (n = 284,400 sequence reads per sample) are presented in Fig. S10. A total of 5803 ASVs were generated from cDNA and gDNA samples of CuNi (n = 10), with a range of 142 to 1811 ASVs. Similarly, 9046 ASVs were generated for cDNA and gDNA samples of Ti (n = 10), ranging from 539 to 1303 ASVs. The feature classifier assigned all ASVs from CuNi and Ti samples to 47 phyla across archaea (n = 4), bacteria (n = 35), and eukaryotes (n = 9), with their relative abundances varying based on sample type. In CuNi samples, Proteobacteria, Planctomycetota, and Bacteroidetes were the main phyla, representing approximately 90% of the overall relative abundance in both cDNA and gDNA (Fig. 5). Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetota, and Cyanobacteria collectively constituted ~90% of the total relative abundance in Ti samples (Fig. 5). At the genus level, Halomonas and Marinobacter were predominantly abundant in both cDNA and gDNA samples from CuNi, especially at 2 and 4 weeks (Fig. 6). Other important genera included members of Rhodobacteraceae, Planctomycetales, and the genus Methylophaga, with the latter two detected from 4 weeks and increasing over time (Table S6 and Fig. 6). In contrast, the Ti samples initially exhibited higher levels of Aestuariibacter, Methylophaga, Alteromonas, and members of Planctomycetota, as well as predatory bacteria from Bradymonadales and Bdellovibrionaceae (Table S6 and Fig. 6). Over time, the genera were replaced by genus Salinisphaera and members of Phycisphaerae, Planctomycetales, and Symphothece.

The alpha diversity indices of microbial communities, including the Faith and Pielou evenness index, for cDNA and gDNA samples of CuNi and Ti are illustrated in Fig. 7A, B, respectively while the Shannon diversity index (H) values for each sample are presented in Table S5. All alpha diversity indices exhibited significant variations between sampling events (p < 0.05). Overall, the values of Faith (species richness) and Pielou’s evenness (species evenness) were found to be lower in CuNi compared to Ti, for both cDNA and gDNA, suggesting that the biofilm on CuNi is less diverse than Ti. Further analysis of Shannon’s index values for individual samples demonstrates an increase in microbial diversity over time, with cDNA values rising from 3.12 at 2 weeks to 3.9 at 16 weeks, and gDNA values increasing from 4.05 at 2 weeks to 4.34 at 16 weeks for CuNi (Table S5), indicating an increase in both active and total microbial communities. In contrast, the microbial diversity in both cDNA (H = 6.15 at 2 weeks to 5.66 at 16 weeks) and gDNA (H = 7.03 at 2 weeks to 5.64 at 16 weeks) of Ti demonstrates a decline in active and total microbial communities over time. The beta diversity indices, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and principle coordinate analysis (PCoA), were employed to assess the similarities in the structure and composition of microbial communities across cDNA and gDNA samples derived from CuNi and Ti metals. HCA revealed two distinct clusters with CuNi and Ti samples showing a clear separation in the dendrogram (Fig. 7C), indicating that the microbial communities associated with CuNi and Ti samples are notably different. In the CuNi cluster, the 2-week cDNA and gDNA samples and the 4-week cDNA sample clustered separately from the samples of later time points, suggesting that the microbial community in the early stages (2 and 4 weeks) is different from later stages. Similarly, in the Ti cluster, the 2- and 4-week cDNA and gDNA samples formed distinct clusters from the later time points, highlighting the differences in microbial communities during the early stages. In the PCoA analysis, PC1 (39.03%) and PC2 (18.97%) explain the majority of the variance observed in the data (Fig. 7D), and the results also indicated that the microbial communities on the CuNi and Ti metals are different, along with the distinction in early colonizers (2 and 4 weeks) of these metals.

While the feature classifier assigned all ASVs from CuNi and Ti samples to around 400 different genera, this study mainly focused on microfouling and important genera from archaea, bacteria, and eukaryote. Subsequently, genera related to early colonizers, sulfur oxidizing bacteria (SOB), Archaea, SRB, and APB detected in the cDNA and gDNA extracted from CuNi and Ti metals are reported here. The classification of these groups (SOB, SRB, and APB) was primarily based on the taxonomic affiliation of genera reported in the literature for respective categories. Regarding early colonizing microflora, the CuNi samples showed a significant presence of Halomonas, a nitrate-reducing bacterium with significant copper resistance31, in both cDNA and gDNA during the early stages (2–4 weeks) (Fig. 8A), with cDNA samples exhibiting close to 40% abundance at 2 weeks. However, their relative abundance reduced over time, particularly in cDNA samples during the 12–16-week period. CuNi also exhibited a high relative abundance of Marinobacter, which is recognized for its role in hydrocarbon degradation and biofilm formation32, during initial stages (2 to 4 weeks) (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, despite a slight reduction in relative abundance over time, their notable presence was observed through the exposure period, highlighting its vital role in biofilm development. Overall, the results indicate that Halomonas and Marinobacter are the initial colonizers on CuNi. However, the decline of Halomonas in later stages indicates a shift in microbial community composition over time, with an increase in Methylophaga, a nitrate-reducing bacterium, in both cDNA and gDNA during later stages (12–16 weeks) (Table S6). In contrast, although Ti samples initially showed the presence of Halomonas and Marinobacter in both cDNA and gDNA at 2 weeks, they demonstrated a significant decline over time, suggesting distinct microbial community composition on Ti compared to CuNi. Ti initially exhibited diverse microbial composition with higher levels of Aestuariibacter, Methylophaga, Alteromonas, and members of Planctomycetota, as well as predatory bacteria from Bradymonadales and Bdellovibrionaceae. which were replaced over time by Salinisphaera and members of Phycisphaerae, Planctomycetales, and Symphothece (Table S6). Also, the filamentous structures observed on Ti under SEM were identified as Phormidium, a filamentous cyanobacterial genus.

Regarding SOBs, CuNi showed their higher relative abundance in cDNA (~8%) and gDNA(~4%) samples at 4 weeks (Fig. 8C), but with a gradual decrease over time (from 4 weeks to 16 weeks), indicating that SOB is still a part of the active microbial community. The SOB genera were identified as Thioalkalispira, Thiohalophilus, Sulfitobacter, and Sulfurimonas. However, Ti showed a minimal or absence of SOB during the exposure period, indicating that Ti is less favorable for their growth. The archaeal genera, such as a Nitrosopumilus (ammonia-oxidizing archaea) and Haloterrigena, along with anaerobic methanogen, Methanosarcina, were detected in the highest abundance at 2 weeks in the gDNA samples (~0.26%) of CuNi (Fig. 8D), while cDNA shows a relatively lower abundance (~0.02%). After 2 weeks, no detectable archaea were observed at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks in cDNA and very low abundance in gDNA (0.01–0.04%), indicating they are less active. In contrast, these archaeal genera are detected at very low levels in Ti samples, with the highest gDNA abundance of 0.01% at 2 weeks. However, they were not detected in either cDNA or gDNA samples from 4 weeks, suggesting Ti may not support archaeal growth compared to CuNi. The relative abundance of SRBs is highest at 2 weeks in the gDNA samples (~0.035%) of CuNi (Fig. 8E), but they showed a gradual decrease over time, with the no abundance detected at 8 weeks and a slight increase at 12 and 16 weeks (~0.001–0.002%), indicating a reestablishment of these groups during later stages. While cDNA has a much lower abundance (~0.005%), its abundance reduced significantly with no detectable SRBs in cDNA samples from 4 weeks. The genera or members of SRBs include Desulfovibrio, Desulforhopalus, Desulfobacter, Desulfobulbus, Desulfobacca, Desulfobacterium, Desulfopila, and members of Desulfosarcinaceae, Desulfobulbaceae, and Desulfocapsaceae, Desulfobacteraceae, Desulfurivibrionaceae, Desulfovibrionales, and Desulfuromonadia, which are obligate anaerobic bacteria. Regarding Ti, the abundance of SRBs is very low during the exposure period, and the highest abundance is detected in gDNA at 2 weeks (~0.0011%). SRBs were not detected in any of the cDNA samples and also in gDNA samples from 4 weeks onwards, indicating Ti surfaces do not support SRB colonization as effectively as CuNi. In case of APBs, their relative abundance is low at 2 weeks for CuNi samples (~0.002% in gDNA, 0% in cDNA), but increased during 4 and 8 weeks (Fig. 8F) with a noticeable increase in gDNA at 8 weeks (~0.008%). A slight decrease at later weeks was observed, but it remained detectable until 16 weeks (~0.005% in gDNA), indicating active and long-term colonization of these groups on CuNi samples. The genera detected for this group of microorganisms include Thiobacillus, Clostridium, and Acidicaldus. In the case of the Ti sample, their abundance is minimal across the 16-week exposure period. The highest abundance is detected at 12 weeks in cDNA (~0.0014%), and no APBs were detected in gDNA of Ti samples, which suggests that Ti supports less APB colonization compared to CuNi.

Discussion

The colonization and biofilm formation on surfaces provide significant advantages to microorganisms that support vital ecological and biogeochemical functions in dynamic marine environments, although they can also result in detrimental effects such as biofouling. Numerous research studies emphasize how specific microbe-surface interactions and inter- and intraspecies communications influence microbial community’s composition, structure, temporal patterns, and functions33. Furthermore, early or primary colonizing microorganisms differ based on several physicochemical surface properties; for instance, copper surfaces exhibit slower colonization due to their toxicity to microorganisms when compared to non-toxic metals, with colonizing species releasing significant amounts of EPS to mitigate the effects of copper34. In the context of MIC in marine settings, the aerobic early colonizers can establish anaerobic niches that support the growth of anaerobic microorganisms, such as SRBs, which are associated with increased corrosion13. While research on primary colonizers and the temporal succession of microbial communities on copper and its alloys is currently limited, this study examined the early colonizers, temporal succession, and diversity of total and active microfouling communities on CuNi and Ti metals in natural seawater, alongside their corrosion behaviors, by utilizing a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach that included electrochemical, surface, and biological analyses to elucidate the mechanisms of MIC.

In the case of CuNi, during the 2-week (early) exposure, Halomonas (a nitrate-reducing primarily aerobic bacteria) and Marinobacter (aerobic bacteria) were significantly found in cDNA (active microorganisms) and gDNA (total microorganisms) with a relative abundance of ~75 and ~60%, respectively. Previous studies reported that microbial communities on copper surfaces employ various mechanisms to mitigate copper toxicity, such as efflux pump systems that facilitate the export of toxic copper ions from cells35. This mechanism features two types of efflux pumps to maintain low intracellular copper levels: (1) ATPase membrane pumps, which utilize ATP to export copper ions through the action of the CopA and CopB genes that encode Cu+- and Cu2+-exporting ATPases, and (2) chemiosmotic membrane pumps, specifically the CusABC complex, which facilitates the transport of Cu+ out of the cell while importing protons across the inner, periplasmic, and outer membranes11,36. In the current study, the detection of copA and cusA genes (Fig. S9) along with biofilm-forming (DG-1 and DG-2) genes in early stages suggests that the copper resistance mechanisms are present in Halomonas and Marinobacter, along with EPS production, that may have facilitated their survival against the antimicrobial effects of copper31,32. In addition to these two bacteria, members of the Rhodobacteraceae family that are known for biofilm formation37 were also abundantly found in the cDNA (~16%) and gDNA (~18%) from CuNi biofilms. While previous research on mature biofilms developed on copper and its alloys after 30 to 44 months of exposure to natural seawater revealed a variety of bacterial genera abundance38, a field study in Italy on CuNi (70/30 alloy) condenser tubes exposed to both short (2 days) and long (12 months) durations of natural seawater showed the presence of Marinobacter, Alteromonas, and Pseudomonas in the biofilms, as identified through conventional denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and sequencing21. Although the current NGS-based study also identified Alteromonas and Pseudomonas on CuNi, they accounted for a small fraction of active and total microorganisms (<1%). Biofilms formed in oxygenated seawater can create localized anaerobic conditions at metal interfaces, enabling the survival of anaerobic bacteria, such as SRBs, within these anaerobic niches34. In the current study, although the abundance of SRBs, APBs, and Archaea was very low in cDNA and gDNA (Fig. 8), the detection of obligate anaerobic SRBs during 2-week seawater exposure confirms the existence of anaerobic niches in the biofilms grown on CuNi. While the critical role of early colonizing microbial communities in adapting to the antimicrobial properties of CuNi was evident, detection of protective Cu2O by Raman spectroscopy and the absence of significant pit formation suggest no substantial corrosion on CuNi after the two-week exposure period, despite the observed low values of polarization resistance (Rp), film resistance (Rf), and charge transfer resistance (Rct).

Cell division and the recruitment of planktonic cells play an important role in diversifying microbial communities and biofilm growth, which can be influenced by factors such as pH, temperature, nutrient concentration, and microorganism densities39. Furthermore, studies have shown that chemotaxis, quorum sensing, cooperation, and competition play crucial roles in biofilm development in marine environments33. Although the mechanism of planktonic cells' recruitment to the biofilm is not known, microbial community diversification was evident in CuNi biofilms from weeks 4 to 16. This was reflected in the increasing Shannon diversity index values from 3.12 to 3.9 for active communities (cDNA) and 4.05 to 4.34 for total communities (gDNA) (Table S5). Over the 16-week exposure, the relative abundance of Halomonas and members of the Rhodobacteraceae family gradually declined, while Marinobacter maintained a notable presence (Fig. 8 and Table S6). In contrast, the genus Methylophaga, which was first detected at 4 weeks, exhibited a steady increase in relative abundance from ~4 to 16% in cDNA and from ~21 to 27% in gDNA. Methylophaga, a nitrate-reducing aerobic bacterium like Halomonas, is known for its biofilm-forming capabilities and has been associated with corrosion of carbon steel surfaces40,41. Similarly, SOBs were predominantly detected starting from week 4; however, their relative abundance declined over time from ~8 to 3% in cDNA and from ~3 to 1% in gDNA (Fig. 8C). SOBs can oxidize elemental sulfur and reduced sulfur compounds, such as H2S metabolized by SRBs, resulting in the production of sulfuric acid that can create corrosive environment42. Furthermore, the synergistic interaction between SOBs inhabiting biofilms with SRBs can further enhance metal dissolution. Among the facultative anaerobic SOBs (Thioalkalispira, Thiohalophilus, and Sulfurimonas) detected in this study, Thiohalophilus were reported to establish symbiotic relationships with SRBs, resulting in distinct spatial arrangements with SRBs located in the inner layer and Thiohalophilus in the outer layer43. In the current study, SRBs started to reduce following early colonization at 2 weeks and were mainly detected in the gDNA-derived communities (Fig. 8E). They were observed at a low relative abundance in week 4, undetectable by week 8, and reappeared in weeks 12 and 16, suggesting a temporal niche adaptation linked to the establishment of anaerobic microenvironments within the maturing biofilm matrix. In contrast, APBs showed an increase after early colonization (2 weeks) and were found in both cDNA- and gDNA-derived communities, although their abundance was relatively low (Fig. 8F). Among the identified APBs, the genus Clostridium, an anaerobic acid producer known for producing acetic acid44, and Thiobacillus, a strictly aerobic bacterium that produces sulfuric acid and is also classified as a SOB9, were more frequently observed than Acidicaldus. In addition, the microbial communities on CuNi surfaces exhibited further diversification by week 16, incorporating genera such as Legionella, Porticoccus, and Balneola, reflecting a shift toward more complex microbial consortia.

Corrosion behavior resulting from the metal-microbe interactions during microbial succession was evaluated through an integrated analysis of electrochemical and surface characterization data. CuNi exhibited a complex and biphasic corrosion pattern: an initial phase of passivation followed by increased corrosion susceptibility. Electrochemical data revealed enhanced corrosion resistance during the first 12 weeks, as reflected by decreasing icorr and increasing Rp (Table 1). However, this trend reversed at 16 weeks, indicated by a notable drop in corrosion resistance. Consistent with this observation, EIS data showed that Rct reached a highest at 12 weeks (54.8 kΩ·cm²) and subsequently declined to 18.5 kΩ·cm² by week 16, while phase angle values stayed above −70o with presence of multiple inflection points, suggested a breakdown or destabilization of the passive oxide film. Furthermore, the underlying mechanism driving the corrosion behavior of CuNi can be explained by integrating surface characterization data with microbial community dynamics. Raman spectroscopy revealed a transition in the composition of the protective oxide layer (Fig. 3). At 4 weeks, the formation of protective Cu₂O was dominant, serving as an effective barrier against corrosion. However, the Fe-based compound, like γ-FeOOH, which can act as both an electron donor and electron carrier in the anaerobic respiratory chain of SRB45, was also detected. Furthermore, there was a noticeable increase in unprotective CuO and Cu(OH)2 over time. Previous studies reported that the occurrence of a consortium of microorganisms with biofilm formation capabilities promotes the precipitation of copper hydroxide and is anticipated to lower the protective capacity of the oxide layer46. Consistent with these findings, the protective Cu2O was less detected after 16-week exposure, which could be due to the increased biofilm formation, that is evident by the detection of higher protein & DNA structures in Raman spectra and SEM image analysis. Furthermore, the development of visible pitting corrosion, reaching depths of 5.8 µm by week 16, suggests that the mature biofilm created conditions that ultimately compromised the protective oxide layer. Over all, this degradation was likely driven by enhanced production of corrosive metabolites by diverse and synergetic microbial communities, such as consortia formed by the reappearance of SRBs alongside detectable APBs at 16 weeks, coupled with the activity of SOBs could have contributed to the establishment of a corrosive microenvironment beneath the biofilm and potentially accelerated MIC processes44. Previous research has indicated that SRBs can destabilize the passive layer on copper-nickel alloys and cause localized corrosion primarily through the release of corrosive hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and sulfide metabolites47,48. Also, SOBs are known to accelerate corrosion by converting sulfur compounds into corrosive sulfuric acid, and APBs may cause localized acidification that destabilizes the protective passive layer on metals9,34. While SRBs typically serve as a reliable indicator for their metabolic role in corrosion, linking the acidogenic activity of APBs to corrosion strictly through their taxonomy has considerable uncertainty, as these functions can vary among different species and environmental contexts.

In contrast to CuNi, Ti exhibited distinctly different microbial communities, as confirmed by clear separation in both HCA and PCA (Fig. 7C, D). Also, Ti initially supported greater microbial diversity than CuNi, with higher Shannon diversity index values of 6.15 for cDNA and 7.03 for gDNA at 2 weeks (Table S5). However, microbial diversity declined to 5.66 for cDNA and 5.64 for gDNA by week 16, indicating a selective pressure may have reduced the diversity49,50. Early colonizers (during 2 and 4 weeks) included a wide range of bacterial genera such as Aestuariibacter, Methylophaga, Alteromonas, Marinobacter, and bacterial predators from Bradymonadales and Bdellovibrionaceae. In contrast, Halomonas and members of the Rhodobacteraceae family, which dominated as early colonizers and contributed to biofilm formation on CuNi, were detected at much lower abundances or completely absent on Ti (Fig. 8A and Table S6), and this may explain the reduced biofilm structures during initial stages. Over time, the microbial community composition shifted to Salinisphaera, which dominated during weeks 8 and 12, followed by an increase in the members of the Phycisphaerae family, filamentous cyanobacteria (Phormidium), and a small fraction of Salinisphaera and Rhodobacteraceae family members by week 16. Notably, Ti showed minimal colonization by SRBs, which were detected at very low levels at 2 weeks and became undetectable after 4 weeks, while APBs were rarely detected, and SOBs remained largely absent throughout the exposure period. This represents a distinctly different microbial successional pattern from that observed on CuNi, and the presence of predatory bacterial members from Bradymonadales and Bdellovibrionaceae on Ti in the early stages suggests bacterial competition may have played a significant role in microbial community development, along with metal-microbe interactions49,51. Members of Bradymonadales and Bdellovibrionaceae are known bacterial predators and exhibit a strong preference for preying on Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria52,53, which includes the aforementioned initial and other colonizers of Ti (Aestuariibacter, Methylophaga, Alteromonas, Marinobacter, and Salinisphaera).

Ti demonstrated exceptional corrosion resistance over the 16-week exposure period in natural seawater. Electrochemical measurements revealed a constant increase in OCP from −341 mVSSC to +130 mVSSC and Rp from 2.35 × 105 to 7.65 × 105 Ω·cm2, indicating improved surface passivation (Table 1). Consistently, EIS also revealed a steady increase in Rct, reaching 2103.5 kΩ·cm2 by week 16 (Table 2) and exhibited a high phase angle plateau near -80 to -90o. This superior corrosion resistance can be attributed to the formation of dense, impermeable TiO2 film, which acts as a barrier against metal ion release and microbial attack22. Raman spectroscopy confirmed the continuous presence of protective TiO₂ (rutile and brookite) throughout the exposure period, with minimal detection of DNA and protein structures, indicating a stable oxide layer (Fig. 3). SEM analysis corroborated these findings, revealing significantly less biofilm development on Ti than CuNi, with microbial colonization remaining less even after 16 weeks. Additionally, minimal pitting confirmed the integrity of the passive layer on Ti. Previous studies reported that the introduction of predatory microorganisms into a MIC system results in the predation and elimination of corrosive microorganisms and their biofilms, thereby inhibiting the entire MIC process54. Qiu et al. 201655 reported that Bdellovibrio effectively mitigated corrosion of X70 steel caused by sulfate-reducing bacteria, thereby recommending predator-based biocontrol as an economical and environmentally friendly approach that requires further validation in complex environments, such as crude petroleum and other real-world structures. Furthermore, studies reported that the damaged passive oxide film can spontaneously regenerate even in environments with low oxygen or water levels, ensuring continued protection of the Ti56. Overall, Ti’s superior corrosion resistance could be attributable to the dense, self-repairing TiO2 passive film together with the potential of predator-based biocontrol to further inhibit MIC. However, the latter necessitates further validation in complex real-world settings. While the current study demonstrates the superior corrosion resistance of Ti, conflicting findings exist regarding its susceptibility to MIC57,58,59,60. Little, et al.57 and Javed, et al.58 reported that Ti and its alloys exhibit resistance to MIC. In contrast, studies by Rao, et al.59 and Unsal, et al.60 documented pitting corrosion on Ti surfaces following exposure to Desulfovibrio vulgaris, suggesting that MIC may still occur under specific conditions.

In summary, the findings highlight the significant role of early microbial colonization in driving MIC and the distinct microbial succession along with their associated corrosion behavior on these metals. CuNi underwent dynamic microbial succession with increasing susceptibility to MIC, characterized by biofilm maturation involving SRBs, SOBs, and APBs, gradual shifts in microbial composition, and further degradation of unstable protective oxide layer (due to presence of unprotective corrosion products CuO, Cu(OH)₂) as indicated by declining Rp and Rct values at 16 weeks. In contrast, Ti exhibited exceptional corrosion resistance, characterized by a progressive increase in OCP and Rp values, and high, stable Rct values in EIS analysis, supported by the consistent presence of protective TiO₂ detected by Raman spectroscopy and minimal microbial colonization. These findings emphasize the critical role of metal-specific microbe interactions in governing long-term corrosion outcomes in marine environments. Future studies using metagenomics or metatranscriptomics could provide a comprehensive understanding of the active metabolic pathways involved in MIC, particularly those linked to copper resistance, sulfur metabolism, acid production, and biofilm formation. Ecological investigations into the roles of predatory bacteria such as members of Bradymonadales and Bdellovibrionaceae, including their prey specificity, interactions with biofilm-forming species, and potential to inhibit microbial colonization, may offer novel strategies for MIC control and biofilm disruption.

Methods

Preparation of specimens

CuNi-90/10 alloy (UNS C70600) and Ti (Grade 2, UNS R504) metal coupons with dimensions of 2.54 × 5.08 × 0.16 cm3 were purchased from the MetaSpec Company (San Antonio, TX). The chemical composition of the metal coupons is presented in Tables S1, S2. Metal coupons were mounted with epoxy resin on one side (for electrochemical test coupons, copper electrodes were embedded within), and the other side was epoxy-free with an experimental exposure area of 11.16 cm2. Each metal coupon’s surface was sequentially polished with 400, 600, and 800 grit silicon carbide papers, followed by rinsing with deionized water, degreasing with ethanol in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min, and dried using hot air according to ASTM G1-03 standards61. The metal coupons were placed immediately in a vacuum desiccator until exposure to natural seawater.

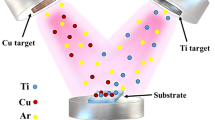

Microcosm setup and sample collection

Microcosm setups simulating the marine environment were designed to evaluate the impact of stagnant seawater conditions on the temporal succession and microbial diversity of total and active microflora, as well as their effects on oxide composition and corrosion of CuNi and Ti metal coupons (Fig. S1). The experiments were conducted using natural seawater collected from the port of Corpus Christi (TX, USA) in September 2023. The chemical composition of the seawater is provided in Table S3. The seawater was collected from 2 m below the water surface at the ship docking site (latitude/longitude: 27°49'25.8“N/97°25'59.5“W), transported immediately to the University of Texas at San Antonio, and stored at 4 °C cold room until use. For each metal type (CuNi and Ti) tested, the respective metal coupons were placed in an individual rectangular acrylic tank (38 × 25 × 20 cm³ in dimension) separately and filled with 16 L of seawater, positioned about 5 cm below the water surface and 2.5 cm above the bottom of the microcosm, without any agitation, to mimic a stagnant marine water ecosystem (Fig. S1). In each microcosm tank, a total of 32 metal coupons (12 for electrochemical and surface characterization and 20 for molecular analysis) were exposed to natural seawater for 16 weeks. During the exposure period, 4 L of seawater was replaced biweekly from each microcosm tank with fresh natural seawater to avoid nutrient depletion. Coupons from each tank were retrieved for analysis at the following exposure times: 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 12 weeks, and 16 weeks. At each sampling time, six coupons for each metal type (CuNi and Ti) were collected: two for surface characterization, and three for molecular analysis (remaining one was stored at −80 oC as backup).

Electrochemical characterization

To evaluate the corrosion performance of the CuNi and Ti metals, electrochemical corrosion tests were carried out using the conventional three-electrode system, with respective metal coupons as the working electrode (WE), a platinum mesh as the counter electrode (CE), and a 4 M KCl saturated Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode (RE). A Gamry 1010E Potentiostat/Galvanostat workstation was used to perform all the electrochemical tests, which include OCP, LPR, and EIS. OCP and LPR were measured in situ every 2 h during the initial 12 h exposure, then followed by twice-per-week measurements. The LPR measurements were performed from −20 to 20 mV from OCP at a scan rate of 0.167 mV/s62,63,64. The EIS was carried out at once-per-week intervals by applying a sinusoidal potential of 10 mV within a frequency range of 100 kHz–0.01 Hz under stable OCP, and the data was analyzed and fitted using the Gamry Framework/ZView2 software63,65. All the electrochemical tests were performed at 25 oC and repeated on at least four coupons to validate the reproducibility of the results.

Surface morphology characterization

The biofilm and corrosion morphologies on CuNi and Ti metal coupons were examined using SEM (ZEISS Crossbeam 340, Germany). For this purpose, the coupons were pre-treated with a biofilm fixation process: coupons were submerged in 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 M phosphate (pH 7) at 4 °C for 8 h, washed with 0.1 M phosphate (pH 7), post-fixed with 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide for 1 h, washed with 0.1 M phosphate (pH 7), gradually dehydrated with different concentrations of ethanol (50, 70, 90, 100%) and dried using critical point carbon dioxide dryer (CPD) as described by de Romero, et al.66, with a minor modification by replacing cacocdylate buffer with 0.1 M phosphate buffer due to hazardous nature of the former. The CDP-dried samples were coated with gold to guarantee an alteration-free and prevent charging of the surface for microscopic observation. The gold-coated metal coupons were examined under SEM at 30x, 300x, 3000x, and 10000x magnification to analyse biofilm morphology.

Raman spectroscopy was utilized to identify the composition of the corrosion products and biofilm on the coupons using a Horiba/Jobin Yvon iHR320 Raman Imaging Spectrometer (Horiba, France). Excitation wavelengths of 785 and 532 nm were applied for CuNi and Ti metals for obtaining clear Raman spectra from corrosion products or microbial residues, respectively. The incident beam was concentrated on the samples with a spot size diameter of 1 µm (high confocality mode). The corrosion product film was analysed in a backscattering configuration utilizing a 50× objective, and spectra were recorded from 100 to 1200 cm−1, with a typical acquisition time of 180 s28,67,68.

Finally, after removing the biofilm and corrosion products, the pit distribution and dimension analysis on the coupons were performed using an Optical Profilometer (Bruker Contour GT-K 3D, Germany) and ZEISS Crossbeam 340 SEM. CuNi metal coupons were cleaned following the ASTM G1 standard61. As standard ASTM cleaning procedures were not available for Ti metals, a protocol developed and tested at the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL, MS, United States) was applied. Ti coupons were treated with a 10% HCl solution containing 1000 ppm FeCl3 for one minute. Subsequently, the pit distribution and dimension on the cleaned coupon surface were analysed using an Optical Profilometer (Bruker Contour GT-K 3D, Germany) and ZEISS Crossbeam 340 SEM (ZEISS, Germany)69.

Molecular analyses

After removing the coupons from the microcosm tanks, the biofilm was carefully scraped off from the coupon surfaces using sterile nylon flocked swabs70 and transferred into 2.0 mL tubes containing RLT Plus buffer with β-mercaptoethanol (Qiagen). Genomic DNA (gDNA) and total RNA in the biofilm samples were extracted using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the modified protocol as described by Okazaki et al.71. The purity and concentration of DNA and RNA extracts were determined using a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and were immediately stored at −80 °C until further analysis. A total of four qPCR assays were selected to quantify functional genes involved in copper (Cu) resistance (copA and cusA) and biofilm formation (DG-1 and DG-2) using gDNA as template (Table S4). The qPCR assays were conducted using a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using a 20 μL reaction volume comprising 10 μL of SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 200 nM of each forward and reverse primer, and 2 μL of gDNA template. The qPCR amplification protocol comprised an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C (and 63 °C for copA). Following amplification, a melting curve analysis was performed to assess the specificity of the amplified products by gradually increasing the temperature from 60 to 95 °C at a rate of 0.4 °C per min. Samples were classified as positive when their melting point aligned with the qPCR standards within a permissible deviation of 0.5 °C72. The gBlock DNA fragments containing the target sequence for each assay were acquired from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Skokie, IL) and utilized as qPCR standards. All samples, standards, and negative controls were tested in duplicate for each assay, with quantities determined based on the standard curve generated using serially diluted plasmid standards (106 to 101 copies/reaction). The absolute gene copy numbers of the markers were determined by averaging the concentration of duplicate reactions and expressed as gene copies per ng of gDNA.

Total RNA extracted from biofilms was converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using the SuperScript™ IV First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen) and stored at −80 °C until further use. The gDNA represents the total microflora, while the cDNA represents only the active microflora of biofilms. The community composition of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes in the extracted gDNA and cDNA was analyzed through NGS employing the AVITI sequencing platform from Element Bioscience (San Diego, CA). PCR amplification and sequencing were performed at the Genomics Core facility of the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA, San Antonio, TX, USA). The improved primer set targeting the V4 and V5 hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was reported to amplify a ~400 bp gene fragment for bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA and ~600 bp gene fragments for fungal 18S rRNA (Table S4)18,19. The PCR reaction was performed using barcoded primers (515 F and 926 R) in triplicate for each sample in a 25 µL reaction volume containing 2× NEBNext® Ultra™ II Q5® Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), 1 µM forward and reverse primers, and 5 ng of template DNA. The PCR cycling conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of 45 s at 95 °C, 45 s at 50 °C, 90 s at 68 °C, and a final elongation step at 68 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel, purified with the AMPure XP beads kit (Beckman Coulter, USA), and quantified in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines using the Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies, USA). The purified PCR products were combined in equimolar concentrations, and gene libraries were constructed utilizing the Elevate Enzymatic Library Prep Kit (Element Bioscience, San Diego, CA). Sequencing was carried out on the AVITI benchtop system utilizing paired-end 300 bp Cloudbreak sequencing kits (Element Bioscience, San Diego, CA).

Bioinformatics analyses

Sequences were processed through a bioinformatics pipeline developed by Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology 2 (QIIME2)73. Forward and reverse primers were removed with cutadapt74 and trimming and truncation of paired-end sequences was performed with DADA2, which also facilitated sequence denoising, merging of reads, and chimera removal75. Representative sequences produced by DADA2 were utilized to construct a phylogenetic tree with mafft76, which subsequently facilitated the calculation of diversity metrics through the core-metrics-phylogenetic plugin in QIIME2. This plugin produced a weighted Unique Fraction (UniFrac) distance matrix, which integrates phylogenetic information based on relative abundance77, and this matrix was exported from QIIME2 for statistical analysis. A feature classifier was trained to improve taxonomic assignment using reference reads extracted from the SILVA database version 132 with 99% similarity according to the primer set employed for sequencing78, and this classifier was subsequently utilized by VSEARCH79 to assign taxonomy to the amplicon sequence variant (ASV) feature table generated by DADA2. To improve the accuracy of SRB and APB detection, the taxonomy generated by the GreenGenes reference database (v 13.8)80 was also used. The microbiome data was transformed into relative frequency (relative abundance) and exported for subsequent analyses.

Statistical analyses

The alpha diversity for each sample, including species diversity and richness, was assessed using Faith’s PD, Pielou evenness, and Shannon (H‘) diversity indices81. The weighted UniFrac distance matrix from the QIIME2 core-metrics plugin was imported into R program82 and beta diversity metrices such as hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) and principle coordinate analysis (PCoA), enabling the visualization of relationships and differences between the microbial communities linked to CuNi and Ti metal coupons over time was analyzed83. The Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test was employed to assess the statistical significance of the bacterial diversity indices and electrochemical parameters48,84.

Data availability

The sequences generated in this study were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI) Short Read Archive database with BioProject Number PRJNA1269211.

References

Little, B. J. et al. Microbially influenced corrosion—any progress?. Corros. Sci. 170, 108641 (2020).

NACE. NACE International impact study http://impact.nace.org/economic-impact.aspx (2016).

Muthukrishnan, T. et al. Monthly succession of biofouling communities and corresponding inter-taxa associations in the North- and South-West of the Arabian Gulf. Front. Marine Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.787879 (2022).

Blackwood, D. J. An electrochemist perspective of microbiologically influenced corrosion. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 1, 59–76 (2020).

Pu, Y. et al. Biogenic H2S and extracellular electron transfer resulted in two-coexisting mechanisms in 90/10 Cu-Ni alloy corrosion by a sulfate-reducing bacteria. Corros. Sci. 211, 110911 (2023).

Amendola, R. & Acharjee, A. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of copper and its alloys in anaerobic aqueous environments: a review. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.806688 (2022).

Dexter, S. C. & Chandrasekaran, P. Direct measurement of ph within marine biofilms on passive metals. Biofouling 15, 313–325 (2000).

Yuan, S., Liang, B., Zhao, Y. & Pehkonen, S. Surface chemistry and corrosion behaviour of 304 stainless steel in simulated seawater containing inorganic sulphide and sulphate-reducing bacteria. Corros. Sci. 74, 353–366 (2013).

Lee, J., Brown, T. & Little, B. in Failure Analysis of Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion Ch. 5 (CRC Press, 2021).

Corcoll, N., Yang, J., Backhaus, T., Zhang, X. & Eriksson, K. M. Copper affects composition and functioning of microbial communities in marine biofilms at environmentally relevant concentrations. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03248 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Metagenomic resolution of functional diversity in copper surface-associated marine biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2863 (2019).

Blackwood, D. J. An electrochemist perspective of microbiologically influenced corrosion. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 1, 59–76 (2018).

Knisz, J. et al. Microbiologically influenced corrosion—more than just microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuad041 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Anaerobic microbiologically influenced corrosion mechanisms interpreted using bioenergetics and bioelectrochemistry: a review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 34, 1713–1718 (2018).

Lu, S. et al. Eutrophication of seawater intensified biocorrosion of copper caused by Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 194, 110–123 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Distinguishing two different microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) mechanisms using an electron mediator and hydrogen evolution detection. Corros. Sci. 177, 108993 (2020).

Kotu, S. P., Mannan, M. S. & Jayaraman, A. Emerging molecular techniques for studying microbial community composition and function in microbiologically influenced corrosion. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 144, 104722 (2019).

Parada, A. E., Needham, D. M. & Fuhrman, J. A. Every base matters: assessing small subunit rRNA primers for marine microbiomes with mock communities, time series and global field samples. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1403–1414 (2016).

Milke, F. et al. Composition and biogeography of planktonic pro- and eukaryotic communities in the Atlantic Ocean: primer choice matters. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.895875 (2022).

Salgar-Chaparro, S. J., Darwin, A., Kaksonen, A. H. & Machuca, L. L. Carbon steel corrosion by bacteria from failed seal rings at an offshore facility. Sci. Rep. 10, 12287 (2020).

Carvalho, M. L., Doma, J., Sztyler, M., Beech, I. & Cristiani, P. The study of marine corrosion of copper alloys in chlorinated condenser cooling circuits: the role of microbiological components. Bioelectrochemistry 97, 2–6 (2014).

Yan, S. et al. A state-of-the-art review on passivation and biofouling of Ti and its alloys in marine environments. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 34, 421–435 (2018).

Sato, T. et al. Assessment of the anti-biofouling potentials of a copper iodide-doped nylon mesh. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 95, 1043–1050 (2012).

Miller, C. et al. Copper and cadmium: responses in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 49, 775–783 (2009).

Lu, S. et al. Extracellular electron transfer corrosion mechanism of two marine structural steels caused by nitrate reducing Halomonas titanicae. Corros. Sci. 217, 111125 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. The effects of Methanococcus maripaludis on the corrosion behavior of EH40 steel in seawater. Bioelectrochemistry 140, 107824 (2021).

Liu, M. & Li, J. In-situ Raman characterization of initial corrosion behavior of copper in neutral 3.5% (wt.) NaCl solution. Materials 12, 2164 (2019).

Ma, A. L., Jiang, S. L., Zheng, Y. G. & Ke, W. Corrosion product film formed on the 90/10 copper–nickel tube in natural seawater: Composition/structure and formation mechanism. Corros. Sci. 91, 245–261 (2015).

Frost, R. L. Raman spectroscopy of selected copper minerals of significance in corrosion. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 59, 1195–1204 (2003).

Thomas, G. J. Jr. Raman spectroscopy of protein and nucleic acid assemblies. Annu Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 28, 1–27 (1999).

Yu, T., Qin, M., Shao, Z., Zhao, Y. & Zeng, X. Isolation of highly copper-resistant bacteria from deep-sea hydrothermal fields and description of a novel species Marinobacter metalliresistant sp. nov. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1390451 (2024).

Mugge, R. L., Salerno, J. L. & Hamdan, L. J. Microbial functional responses in marine biofilms exposed to deepwater horizon spill contaminants. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.636054 (2021).

Dang, H. & Lovell, C. R. Microbial surface colonization and biofilm development in marine environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 91–138 (2016).

Little, B. J. & Lee, J. S. LaQue’s Handbook of Marine Corrosion (Wiley, 2022).

Chacón, K. N., Mealman, T. D., McEvoy, M. M. & Blackburn, N. J. Tracking metal ions through a Cu/Ag efflux pump assigns the functional roles of the periplasmic proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 15373–15378 (2014).

Affandi, T. & McEvoy, M. M. Mechanism of metal ion-induced activation of a two-component sensor kinase. Biochem. J. 476, 115–135 (2019).

Mugge, R. L., Lee, J. S., Brown, T. T. & Hamdan, L. J. Marine biofilm bacterial community response and carbon steel loss following deepwater horizon spill contaminant exposure. Biofouling 35, 870–882 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Analysis of marine microbial communities colonizing various metallic materials and rust layers. Biofouling 35, 429–442 (2019).

Lewandowski, Z. & Beyenal, H. Fundamentals of Biofilm Research (CRC Press, 2013).

Salerno, J. L., Little, B., Lee, J. & Hamdan, L. J. Exposure to crude oil and chemical dispersant may impact marine microbial biofilm composition and steel corrosion. Front. Marine Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00196 (2018).

Schwermer, C. U. et al. Impact of nitrate on the structure and function of bacterial biofilm communities in pipelines used for injection of seawater into oil fields. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2841–2851 (2008).

Okabe, S., Odagiri, M., Ito, T. & Satoh, H. Succession of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in the microbial community on corroding concrete in sewer systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 971–980 (2007).

Rajala, P., Cheng, D.-Q., Rice, S. A. & Lauro, F. M. Sulfate-dependant microbially induced corrosion of mild steel in the deep sea: a 10-year microbiome study. Microbiome 10, 4 (2022).

Little, B. J. & Lee, J. S. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion (John Wiley & Sons, 2007).

Javed, M. A., Neil, W. C. & Wade, S. A. Effect of ferrous sulfate treatment on microbially influenced corrosion of CuNi 70/30 marine pipeline alloy by sulfate reducing bacteria. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 10, 2597–2614 (2024).

Galarce, C. et al. Effect of hazardous bacteria isolated from copper plumbing system on microbiologically influenced corrosion of copper. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 14, 2305–2320 (2019).

Wang, J., Li, H., Du, M., Sun, M. & Ma, L. Study on mechanism underlying the acceleration of pitting corrosion of B30 copper–nickel alloy by sulfate-reducing bacteria in seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 928, 172645 (2024).

Javed, M. A., Neil, W. C. & Wade, S. A. From defence to damage: the impact of seawater passivation on microbially influenced corrosion in CuNi 70/30 alloy. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 10, 2929–2945 (2024).

Feng, S. et al. Predation by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus significantly reduces viability and alters the microbial community composition of activated sludge flocs and granules. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fix020 (2017).

Hibbing, M. E., Fuqua, C., Parsek, M. R. & Peterson, S. B. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 8, 15–25 (2010).

Mookherjee, A. & Jurkevitch, E. Interactions between Bdellovibrio and like organisms and bacteria in biofilms: beyond predator–prey dynamics. Environ. Microbiol. 24, 998–1011 (2022).

Wucher, B. R., Elsayed, M., Adelman, J. S., Kadouri, D. E. & Nadell, C. D. Bacterial predation transforms the landscape and community assembly of biofilms. Curr. Biol. 31, 2643–2651.e2643 (2021).

Mu, D.-S. et al. Bradymonabacteria, a novel bacterial predator group with versatile survival strategies in saline environments. Microbiome 8, 126 (2020).

Lou, Y. et al. Microbiologically influenced corrosion inhibition mechanisms in corrosion protection: a review. Bioelectrochemistry 141, 107883 (2021).

Qiu, L. et al. Inhibition effect of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus on the corrosion of X70 pipeline steel induced by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 63, 269–274 (2016).

Prando, D. et al. Corrosion of titanium: Part 1: aggressive environments and main forms of degradation. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 15, e291–e302 (2017).

Little, B. J., Wagner, P. A. & Ray, R. I. An evaluation of titanium exposed to thermophilic and marine biofilms. In Proceedings of the Corrosion 1993. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5006/C1993-93308 (New Orleans, LA,1993).

Javed, M. A., Neil, W. C., McAdam, G. & Wade, S. A. Effect of sulphate-reducing bacteria on the microbiologically influenced corrosion of ten different metals using constant test conditions. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 125, 73–85 (2017).

Rao, T., Kora, A. J., Anupkumar, B., Narasimhan, S. & Feser, R. Pitting corrosion of titanium by a freshwater strain of sulphate reducing bacteria (Desulfovibrio vulgaris). Corros. Sci. 47, 1071–1084 (2005).

Unsal, T. et al. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of titanium by Desulfovibrio vulgaris biofilm under organic carbon starvation. Bioelectrochemistry 149, 108307 (2023).

ASTM. Standard practice for preparing, cleaning, and evaluation corrosion test specimens. ASTM international. lggg (2017).

Zhang, D. et al. Multiscale characterization of seawater pipe erosion of B10 copper–nickel alloy welded joints. Sci. Rep. 12, 2164 (2022).

Dacio, L. J. P. et al. Evaluating 1-benzyl-4-phenyl-1H-1,2,3-triazole as a green corrosion inhibitor in a synthetic pore solution to protect steel rebars. Corrosion 79, 405–418 (2022).

ASTM. G59-97: Standard Test Method for Conducting Potentiodynamic Polarization Resistance Measurements. ASTM International (2014).

Gao, X. & Liu, M. Corrosion behavior of high-strength C71500 copper-nickel alloy in simulated seawater with high concentration of sulfide. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15238513 (2022).

de Romero, M. F. et al. Evaluation of Cathodic Protection in presence of Sulfate Reducing Bacteria mixed cultures. In Proceedings of Corrosion 2008. 1–18 (2008).

Jin, T. et al. Surface characterization and corrosion behavior of 90/10 copper-nickel alloy in marine environment. Materials https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12111869 (2019).

Lubas, M. et al. Raman spectroscopy of TiO2 thin films formed by hybrid treatment for biomedical applications. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 133, 867–871 (2014).

Carvalho, R. N., Rincon Troconis, B. C., Pioszak, G., Ynciarte, V. & Scully, J. R. Effect of microstructure on the pitting susceptibility of a martensitic-ferritic stainless steel: a corrosion-metallurgical study. Corros. Sci. 202, 110277 (2022).

Stamps, B. W. et al. In situ linkage of fungal and bacterial proliferation to microbiologically influenced corrosion in B20 biodiesel storage tanks. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00167 (2020).

Okazaki, Y. et al. A fast and easy method to co-extract DNA and RNA from an environmental microbial sample. Microbes Environ. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME22102 (2023).

Nutz, S., Döll, K. & Karlovsky, P. Determination of the LOQ in real-time PCR by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis: application to qPCR assays for Fusarium verticillioides and F. proliferatum. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 401, 717–726 (2011).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol 30, 772–780 (2013).

Lozupone, C., Lladser, M. E., Knights, D., Stombaugh, J. & Knight, R. UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J. 5, 169–172 (2011).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2012).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072 (2006).

Chao, A., Chiu, C.-H. & Jost, L. in Biodiversity Conservation and Phylogenetic Systematics: Preserving our evolutionary heritage in an extinction crisis (eds Pellens, R. & Grandcolas, P.) (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Team, R. C. R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/oxygen-consuming-substances-in-rivers/r-development-core-team-2006 (2020).

Moghadam, S. V., Vadde, K. K., Phan, D. C., Jafarzadeh, A. & Kapoor, V. Assessing the impact of flooding on bacterial community structure and occurrence of potentially pathogenic bacteria in Texas Rivers after Hurricane Harvey. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 3, 100058 (2022).

Pérez-Valdespino, A., Pircher, R., Pérez-Domínguez, C. Y. & Mendoza-Sanchez, I. Impact of flooding on urban soils: Changes in antibiotic resistance and bacterial community after Hurricane Harvey. Sci. Total Environ. 766, 142643 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research (ONR Code 332) under award number N00014-23-1-2325. The authors thank Dr. Brenda Little for her invaluable feedback and Sean Vargas at the UTSA Genomics Core for assistance with sequencing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.K.V.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft. J.E. and A.M.B.: Methodology. O.T.d.R.: Methodology, formal analysis, and writing—review & editing. J.S.L.: Conceptualization and writing—review & editing. B.R.T.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review & editing, funding acquisition, and supervision. V.K.: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review & editing, funding acquisition, project administration, and supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vadde, K.K., Escribano, J., Betancourt, A.M. et al. Temporal succession of microfouling communities in microbiologically influenced corrosion of copper-nickel and titanium in seawater. npj Mater Degrad 9, 140 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00687-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00687-3