Abstract

A novel high-throughput platform enabling high-efficient preparation of droplet microarray and automatic characterization of corrosion morphologies was employed to investigate droplet corrosion on carbon steel. One hundred droplets with different compositions (NaCl and Na2SO4), concentrations (from 0.4 wt.% to 4 wt.%) and pH values (3, 7 and 10) were obtained within 2 h. The average height of accumulated corrosion products (H) in neutral NaCl droplets decreased as NaCl concentration exceeded 2.4 wt.%, while H value in neutral Na2SO4 droplets increased continuously with the increasing Na2SO4 concentration. Finite element modelling confirmed that the high surface coverage of corrosion products in high-concentration NaCl droplets prohibited corrosion products accumulation. The less aggressive SO42− resulted in a low surface coverage thereby enabling continuous corrosion products formation. For the influence of pH values, the corrosion rate in acidic environment (pH=3) was the largest due to the formation of non-protective γ-FeOOH and FeCl2, while the alkaline environment (pH=10) showed the least corrosion rate as more protective α-FeOOH was generated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atmospheric corrosion is a ubiquitous problem that widely affects infrastructure, transportation, energy and other industries1,2,3. According to the recent analysis, the overall cost of corrosion is estimated to be 3.4% of global GDP, among which atmospheric corrosion accounts for approximately half the annual cost of all types of metal corrosion4,5,6. Generally, the atmospheric corrosion process is initiated by wetting of the metal surface, where atmospheric moisture condenses as liquid phase due to temperature changes. Elliptical droplets subsequently evolve as a result of the hygroscopic properties of surface contaminants deposited on the metal surface7,8,9,10. These droplets are usually different both in chemical compositions and solute concentrations11,12,13,14, as regional and seasonal differences could significantly affect the compositional diversity and abundance of atmospheric contaminants. The diversity of droplet chemistry could significantly influence the metal dissolution rate, the type of corrosion products and so on. Besides, the elliptical geometry of the droplets also leads to different oxygen diffusion path between the droplet edge and the droplet center, which was proved by U.R. Evans in the 192015. The varying O2 concentration along the electrode surface would further influence the kinetics of atmospheric corrosion and also induces the localized corrosion effect. Therefore, the diversity of droplet chemistry and the uniqueness of droplet geometry make the droplet corrosion behavior in atmospheric environment highly complicated.

Recent studies have investigated droplet corrosion behavior with a focus on the effects of droplet chemistry and geometry. For example, Steven et al.16 found that the initial MgCl2 concentration in the droplet is primarily responsible for the pit location of 314 L stainless steel during atmospheric corrosion, which could be attributed to the “differential aeration” and voltage drop effects originated from the solution resistance. The pits were predominantly formed in the droplet center for MgCl2 concentrations higher than 4 M, while the pits were closer to the perimeter for MgCl2 concentrations ranging from 1.5 M to 3 M. Rahimi et al.17 proposed a new micro-sized three-electrode-cell for atmospheric corrosion monitoring, recording the droplet geometry change during evaporation from 5 μL to 1.5 μL at 0.1 M and 0.2 M NaCl. In this process, the type of corrosion also changed from uniform corrosion to more localized one. This could be explained by the change in O2 diffusion from a two-dimensional process to a one-dimensional process, which resulted in a high level and uniform O2 distribution along the electrode surface. He et al.18 studied the settling dynamics of salt water contaminant oil onto the M50 bearing steel surface and its influencing mechanism on the corrosion behavior. The larger NaCl droplet would induce an isolated localized corrosion area at the outer zone of the metal, which could be attributed to its higher approaching velocity in oil and thereby the longer duration on the metal surface. Despite the progress in previous research, droplets samples with various geometries, compositions and concentrations have been artificially created one by one, involving labor-intensive solution preparation and repetitive single-droplet fabrication. Such an approach was time-consuming, inefficient and lacks precise control, thereby constraining the efficient investigation of droplet corrosion behavior, especially for the study involving multivariate and simultaneous corrosion tests.

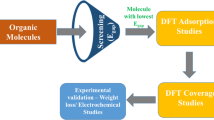

Lately, the emergence of high-throughput method has addressed these limitations by enabling the parallel fabrication and evaluation of numerous droplet samples. Ren et al.19 employed a high-throughput method based on droplet microarray, which could create more than 200 corrosion micro-environments containing different concentrations of BTA and Ce(NO3)3 within 2 min. This method was especially beneficial in rapid evaluation and assessment of the optimal corrosion inhibitor combinations. Besides, a multi-droplet condition was successfully developed based on the spraying method in Zhang’s work20. By real-time monitoring of the corrosion rate and geometry change of numerous droplets, the critical factor relating to carbon steel corrosion during different corrosion stages was rapidly discovered. As a result, the high-throughput approach could dramatically reduce time and labor, while allowing precise and multivariate corrosion tests under controlled environments, thereby greatly enhancing the efficiency and scope of droplet corrosion investigations.

In this work, a novel experimental platform allowing for high-throughput dispensing of droplet microarray and automatic characterization of corrosion morphologies was developed to investigate atmospheric corrosion of carbon steel under different droplets. Benefiting from this platform, 100 droplets (80 nL) with various concentrations of NaCl or Na2SO4 and different pH values could be prepared within 1 h. The three-dimensional morphologies of these corrosion sites were obtained automatically using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) equipped with a self-designed computer program. To better understand the effect of corrosion products formation on mass transfer and the kinetic process inside the droplet, finite element modeling (FEM) method was employed to simulate droplet corrosion process of the carbon steel. The distribution of corrosion products and their compositions formed in different pH environments were also examined experimentally.

Results and discussion

Effect of droplet composition on droplet corrosion behavior

The 3D morphologies of the carbon steel after corrosion in different droplets were recorded using CLSM characterization (Fig. 1). It could be seen from Fig. 1a that the corrosion products developed in 0.4 wt.%. NaCl droplet showed a typical circular morphology. According to the Evan’s droplet corrosion model15, the difference in oxygen concentration between the center and the edge of the droplet was the main driving force governing droplet corrosion, where the droplet center and the droplet edge were located as the anode and the cathode, respectively. In this condition, Fe2+ mainly generated around the center of the droplet and migrated towards the edge of the droplet, while OH- mainly formed at the edge of the droplet and then migrated to the center part21,22,23. Once they reacted with each other during the migration process, hydroxide precipitates formed, thereby presenting the nearly round-shape corrosion morphology. Besides, according to Fig. 1b, H value of the corrosion products in 0.4 wt.% NaCl droplet is about 14 μm/cm2. When increasing NaCl concentration to 2.4 wt.%, the morphology of the corrosion products still exhibits a circular characteristic, indicating the formation of oxygen concentration cell in the process of droplet corrosion. The H value of the corrosion products increases to about 26 μm/cm2 (Fig. 1b), which implies that corrosion has intensified with increasing NaCl concentration. However, further increase in NaCl concentration to 4.0 wt.% induced a quite different droplet corrosion morphology, with the feature of typical corrosion product ring being weakened (Fig. 1a). This verifies that the formation of oxygen concentration corrosion cell is suppressed. Besides, H value of the corrosion products formed in 4.0 wt.% NaCl droplet has decreased to 18 μm/cm2. In contrast, in the droplets containing different concentrations of Na2SO4 from 0.4 wt.% to 4.0 wt.%, the morphologies of corrosion products all exhibit typical ring characteristic (Fig. 1a). H value of the corrosion ring increased from 18 μm/cm2 to 28 μm/cm2 when Na2SO4 concentration reaches up to 4.0 wt.%. This indicates that the degree of droplet corrosion in Na2SO4 environment is gradually aggravated by the increasing Na2SO4 concentration, which is quite different from that in the NaCl solution.

To further investigate the influence of pH on droplet corrosion behavior of carbon steel, the droplet microarray with different pH values was also dispensed on the steel surface using the same method. Figure 2 shows the corrosion morphologies and H values evolved in the droplets with different solute concentrations and pH values. Particularly, when the solute concentration was smaller than 2.4 wt.%, the corrosion products generated in the droplets with a pH value of 3 and 10 were too unstable to be measured, therefore only the droplets with the solute concentration higher than 2.4 wt.% were characterized here. As observed from Fig. 2a, only a small amount of corrosion products was generated in NaCl droplet with a pH value of 3, and accordingly the H value is also the lowest among all the different pH groups (Fig. 2b). From the existing literature, acidic environment is more likely to induce carbon steel corrosion compared to neutral environment24,25,26. Specifically, abundant H+ in the acidic environment could accelerate both the hydrogen evolution and the metal dissolution reactions, and the corrosion products generated in this environment are usually soluble salts rather than a protective oxide film27,28. That’s why droplet corrosion in an acidic NaCl environment exhibit limited corrosion products accumulation and lower H value. By contrast, Fig. 2 also shows that when the pH value is 10 in the NaCl droplets, the corrosion morphology again exhibits the typical ring characteristic, and the H value increases to about 20 μm/cm2, which is quite similar to that formed in the neutral environment. For droplets containing different concentrations of Na2SO4, decreasing the pH value to 3 in the droplet also leads to minimal corrosion product precipitation, indicating the effect of H+ on promoting the formation of soluble corrosion products. When the pH value increases to 10 in Na2SO4 droplets, the corrosion morphology becomes irregular (Fig. 2c), and H value is slightly lower than that in the neutral environment, which might be ascribed to the formation of protective corrosion products formed in alkaline environment.

a 3D morphologies of the corrosion sites evolved in NaCl droplets with different concentrations and pH values, and b corresponding H value; c 3D morphologies of the corrosion sites evolved in Na2SO4 droplets with different concentrations and pH values, and d corresponding H value (Scale bar: 100 μm).

In particular, the resulting corrosion morphology reflects the collective contribution of several processes occurred during droplet corrosion, including electrode reactions, mass transport, corrosion product formation and so on. Therefore, FEM simulation and corrosion products characterizations are further carried out to gain a deeper understanding of droplet corrosion behavior.

Hindrance effect of corrosion products on the electrode reactions

It is accepted that corrosion products formed on the steel surface could suppress anodic dissolution reaction by covering the active sites on the electrode surface, and cathodic O2 reduction reaction by slowing down the mass transfer process of O229,30,31,32. To evaluate the hindrance effect of corrosion products, the surface coverage of corrosion products on the electrode formed in different droplets was calculated by FEM33 (taking the neutral droplets as an example). Figure 3a shows that the surface coverage of corrosion products gradually increases with the increasing corrosion duration and NaCl concentration in the droplet. Notably, the surface coverage values in 0.4 wt.% and 2.4 wt.% NaCl droplets reach 0.5 and 0.9, respectively, after 2 h of corrosion, whereas in 4 wt.% NaCl droplets, the surface coverage reaches 1.0 after only 1 h. This could be explained by the higher corrosion rate induced by the higher NaCl concentration. Once the surface coverage reaches 1, the subsequent formation rate of corrosion products could significantly decline since both the anodic and cathodic reactions are largely impeded. That’s the reason why H value observed by CLSM decreases as the NaCl concentration increases to 4 wt.% in the droplet (Fig. 1b). Additionally, Fig. 3b further illustrates that the maximum surface coverage of corrosion products in Na2SO4 solution is lower than 1 (nearly 0.9) even for the droplets containing 4 wt.% Na2SO4. The less pronounced steric hindrance effect could be attributed to the fact that SO42- is less aggressive than Cl- for carbon steel corrosion34,35. Such a variation trend in surface coverage is also consistent with that observed by previous CLSM measurements (Fig. 1b). Apart from the surface coverage, the anodic current density, the cathodic current density and the O2 distribution along the electrode surface could also reflect the steric hindrance effect of corrosion products (Supplementary Figs. S1, S2). Although both the electrode current density and O2 concentration decline with the increasing corrosion period and solute concentration due to the increment in surface coverage of the corrosion products36,37, the difference of these variables between the droplet center and the edge is minimal in the current model, indicating a less pronounced localized corrosion effect. Similar models in the literature that investigate metal corrosion under a droplet or thin electrolyte film generally employ larger geometries and longer corrosion durations20. Therefore, the possible reasons for the slight localized corrosion effect could be the small size and the short corrosion duration (only 2 h) in the current model, where O2 could diffuse rapidly throughout the droplet and thereby leading to a deviation from localized corrosion behavior.

To further amplify the localized corrosion effect of droplet corrosion, the model geometry was further expanded with a droplet diameter of 7 mm and a droplet height of 5 mm. Figure 4a1–a3 exhibits the total amount of precipitated corrosion products on the steel surface after 2 h of corrosion in different NaCl droplets. In both 0.4 wt.% and 2.4 wt.% NaCl droplets, the corrosion products exhibit the typical ring morphology, with the total amount increasing from about 0.15 mg/m2 to 0.4 mg/m2. When the NaCl concentration further increased to 4 wt.%, the accumulated corrosion products decreased to about 0.2 mg/m2 and the corrosion ring also weakened. And the corrosion products tend to accumulate more at the droplet center rather than at the edge. This variation is also consistent with the previous CLSM results (Fig. 1a). Figure 4b1–b3 further exhibits the surface coverage of the corrosion products on the steel. In all the calculated cases, the surface coverage of corrosion products gradually increases with the increasing corrosion time, among which the surface coverage in 4 wt.% NaCl droplet exhibits the most pronounced increase from 0 to nearly 1. Additionally, the surface coverage at the droplet edge is more pronounced than the droplet center with the extending corrosion duration, indicating a gradually intensified localized corrosion effect. This effect is also verified by the O2 concentration across the electrode surface, which could reflect the influence of accumulated corrosion products on mass transfer38,39. As observed from Fig. 4c1, the O2 concentration at the droplet edge in 0.4 wt.% NaCl is nearly equal to the saturation solubility of oxygen in the droplet (0.18 mol·m−3) during the initial 1 h of corrosion, which is higher than that in the droplet center. This could be explained by the timely replenishment of O2 at the droplet edge due to its much shorter diffusion path compared to the droplet center. However, as the corrosion time extends to 2 h, the oxygen concentration along the electrode surface has dropped to 0.09 mol·m−3 both at the droplet edge and the center, indicating limited O2 diffusion due to more accumulated corrosion products. For the 2.4 wt.% NaCl droplet, O2 concentration begins to decline along the whole electrode surface after corrosion for 1 h (Fig. 4c2). The hindrance effect is most evident in the 4 wt.% NaCl droplets as indicated by the lowest O2 concentration (nearly 0 mol·m−3, Fig. 4c3) and the highest surface coverage (1.0, Fig. 4b3) on the electrode surface after 2 h of corrosion.

a1–a3 Total amount of the precipitated corrosion products formed in the droplets with 0.4 wt.%, 2.4 wt.% and 4 wt.% NaCl (the arrow presents the direction of current density), b1–b3 Coverage of the electrode surface by corrosion products in the droplets with 0.4 wt.%, 2.4 wt.% and 4 wt.% NaCl, c1–c3 O2 concentration along the electrode surface in the droplets with 0.4 wt.%, 2.4 wt.% and 4 wt.% NaCl.

The hindrance effect of corrosion products could further influence the kinetics process of carbon steel corrosion under a droplet. Therefore, the distributions of anodic dissolution current density and cathodic oxygen reduction current density along the electrode surface were also investigated by FEM. As shown in Fig. 5a1–a3, the anodic dissolution current density continuously drops with the increasing corrosion duration in all the calculated cases. The current density in 4 wt.% NaCl droplet exhibits the most pronounced decline, highlighting the strongest hindrance effect of corrosion products. Similarly, Fig. 5b1–b3 further illustrates that the cathodic reduction current density also declines with the increasing corrosion time in different NaCl droplets, which could be ascribed to the limited O2 diffusion along the electrode surface. By further establishing the correlation between the evolution of surface coverage and the current density of electrode reactions, it is revealed that a large surface coverage leads to a significant suppression of the electrode reaction kinetics. Additionally, the initial corrosion rate in the 4 wt.% NaCl droplet is the highest as verified by the largest electrode current density (Fig. 5a3, b3), which leads to significant accumulation of corrosion products and increased surface coverage on the steel surface. These corrosion products could suppress subsequent corrosion rate and also reduce the formation of additional corrosion products, which aligns with the results obtained by previous CLSM measurements.

a1–a3 Anodic current density of droplets containing 0.4 wt.%, 2.4 wt.% and 4 wt.% NaCl as a function of time, b1–b3 cathodic current density of droplets containing 0.4 wt.%, 2.4 wt.% and 4 wt.% NaCl as a function of time, c1–c3 total current density of droplets containing 0.4 wt.%, 2.4 wt.% and 4 wt.% NaCl as a function of time.

To further investigate the formation of local anodes and cathodes during droplet corrosion, the total current density distribution along the electrode surface in different droplets is calculated (Fig. 5c1–c3). Specifically, the total current density higher than 0 corresponds to the anode, while the total current density lower than 0 represents the cathode. As observed, the droplet edge region functions as the cathode, whereas the area near the center acts as the anode. It is also obvious that the anode-cathode boundary to the droplet center remains almost unchanged (from 6 mm to 5.5 mm) when the NaCl concentration increases from 0.4 wt.% to 4 wt.% after corrosion for 2 h. Therefore the localized corrosion effect influenced by the area ratio of the anode and cathode is almost the same in all the NaCl droplets29. In contrast, it can be found that the difference in the anodic dissolution current density between the anode and cathode regions is the largest in 4 wt.% NaCl droplet, which is primarily responsible for the strongest localized corrosion effect and therefore leading to abundant corrosion products precipitation in the early stage of droplet corrosion29.

As for the droplets containing different concentrations of Na2SO4, FEM simulation proves that the accumulated corrosion products on the steel surface all exhibit the typical corrosion ring morphology, where the maximum deposition amount of corrosion products gradually increases from 0.09 mol/m2 to 0.324 mol/m2 with increasing the Na2SO4 concentration (Fig. 6a1–a3). Other than that, Fig. 6b1–b3 shows that the extent of corrosion product coverage also expands progressively with prolonged corrosion duration and increased Na2SO4 concentration. However, the maximum surface coverage of corrosion products on the steel in Na2SO4 droplets (0.6) is significantly smaller than that in NaCl droplets (1.0), resulting in a less pronounced steric hindrance effect both on the anodic dissolution reaction and the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction. Such an alleviated steric hindrance effect was also verified by the higher O2 concentration along with higher anodic and cathodic current densities across the electrode surface in Na2SO4 droplets (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Finally, comparison of the two models with different droplet sizes and geometries shows that the trend in surface coverage is nearly identical, increasing consistently with corrosion duration and solute concentration. However, the model with a larger geometry exhibits a more evident localized effect due to the prolonged oxygen diffusion pathway under the same corrosion duration40,41,42,43, which is in agreement with the experimental results.

Corrosion rate prediction and corrosion products characterization

The corrosion depth of carbon steel after corrosion for 2 h under various droplets was further calculated by FEM method. It is observed in Fig. 7a,b that in both NaCl and Na2SO4 droplets, the corrosion depth of carbon steel is the greatest in acidic environments, followed by neutral environments, and the smallest in alkaline environments. The largest corrosion depth in NaCl droplets is 0.010 μm, while the largest corrosion depth in Na2SO4 droplets is 0.005 μm. Additionally, the average annual corrosion rate of carbon steel calculated by the FEM model is between 0.00876 mm/a to 0.0438 mm/a, which is similar to the actual corrosion rate of carbon steel in the industrial atmospheric environment (e.g., Hebei and Sichuan Province, 0.0236 mm/a and 0.0284 mm/a)44,45. This indicates that the developed FEM model can serve as a practical tool to semi-quantitatively predict metal corrosion rates.

Furthermore, to elucidate the difference in corrosion rate in different pH environments, the corrosion products were also detected by Raman characterization. Generally, the characteristic peak at 287 cm−1 is assigned to the formation of FeCl246. The peak positions at 217 cm−1 and 252 cm−1 correspond to γ-FeOOH47,48,49, while the peak positions at 300 cm−1, 387 cm−1 and 1003 cm−1 represent α-FeOOH50. As observed from Fig. 7c, the corrosion products formed in acidic environment mainly composed of FeCl2 and γ-FeOOH, while the corrosion products developed in neutral and alkaline environment primarily consist of γ-FeOOH and α-FeOOH. Notably, the peaks of γ-FeOOH and α-FeOOH in neutral environment are relatively weak compared to that in alkaline environment, indicating a small amount of corrosion products. From literature, γ-FeOOH is an unstable iron oxide which could convert into other corrosion products and lacks protective functionality. In contrast, α-FeOOH shows the best stability among all the corrosion products and thereby providing good corrosion protection for the steel substrate38,51. Therefore, the corrosion rate of carbon steel is more intensive in acidic environment than in neutral environment due to the inferior protectiveness of the corrosion products. This analysis could be further verified by the SEM results shown in Fig. 8. From Fig. 8a, the corrosion products in the acidic environment contain granular FeCl2 and multiple strips of γ-FeOOH. However, in Fig. 8b, c, it is seen that the signal of Cl mainly originates from NaCl crystals rather than FeCl2 in neutral and alkaline environment. And the corrosion products in these two environments are both made up of multiple strips of γ-FeOOH and spheres of α-FeOOH, with a larger proportion of protective α-FeOOH in the alkaline environment.

In summary, a novel high-throughput platform enabling high-efficient dispensing of droplet microarray and automatic measurement of corrosion morphology was developed to investigate atmospheric corrosion behavior of Q235 carbon steel under varying corrosive droplets. Compared with traditional artificial experiments, 100 droplets with independent composition together with corrosion products characterization could be realized with the efficiency increased by hundreds of times. The results indicated that the average height of corrosion products per area (H) exhibited an initial increase and followed by a subsequent decline when NaCl concentration increased from 0.4 wt.% to 4 wt.% in the droplet, where the maximum H value appeared in the 2.4 wt.% NaCl droplet. For the Na2SO4 droplets, H value gradually increases with the increasing Na2SO4 concentration (from 0.4 wt.% to 4 wt.%). FEM analyses proved that the surface coverage of corrosion products on the steel is responsible for the deposition morphology. For the 4 wt.% NaCl droplets, the largest difference in anodic dissolution current density between the droplet edge and the center considerably contributed to the localized corrosion effect, which resulted in a rapid increase in surface coverage and thereby inhibiting further corrosion products accumulation. Since SO42- are less aggressive than Cl-, the increment in surface coverage is relatively slow, which led to continuous corrosion products accumulation. The unstable γ-FeOOH and non-protective FeCl2 accounted for the highest corrosion rate in acidic environment, while a larger amount of protective α-FeOOH generated in alkaline environment resulted in the least corrosion rate.

Methods

Materials and solutions

Q235 carbon steel was selected as the metal substrate in this work (purchased from Dongguan Hengde Steel Co., Ltd.), with the specific chemical composition shown in Table 1. The dimension of the carbon steel sheet was 60 mm × 80 mm × 1 mm. All specimens were mechanically abraded by 800 SiC paper, followed by polishing using W20 and W7.5 water-based diamond polishing pastes with a roughness of 16–20 μm and 5–7 μm, respectively. After each grinding and polishing operation, the steel sheets were ultrasonically cleaned in deionized water and ethanol to remove residue sample particles and polishing pastes. Prior to all tests, the samples were put in a desiccator to keep dry and avoid any changes in properties due to the presence of moisture in the atmosphere.

The corrosion media used in this work were Na2SO4 and NaCl dissolved in deionized water, each in the concentration of 8 wt.%. All chemicals were obtained from Aladdin Chemical Co., Ltd. Additionally, to evaluate the influence of pH value on the corrosion behavior, HCl (pH = 3) and NaOH (pH = 10) solutions were also employed to obtain the acidic and alkaline droplet microarray, respectively.

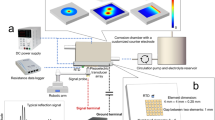

High-throughput droplet dispensing on the carbon steel sheet

The corrosive droplet microarray was obtained by a non-contact droplet microarray printer (GESIM Nano Plotter 2.1, Germany). The printer featured a piezoelectric pipetting tip for software-controlled automated droplet dispensing, along with a high-speed stroboscope camera for real-time imaging to ensure precise droplet placement. During the droplet dispensing process, the pipetting tip squeezed and ejected the solution at a frequency of 400 times per second (400 pL per ejection). By adjusting the number of ejections, droplets of different volumes could be quickly prepared on the steel surface. Before each dispensing, the inner and outer surfaces of the pipetting tip was fully cleaned by deionized water to avoid contamination. During the droplet dispensing process, an ultrasonic humidifier was employed to prevent water evaporation in the droplet.

The dispensing strategy of the droplet microarray on the steel surface was presented in Fig. 9. Taking neutral NaCl droplet microarray as an example, different volumes of 8 wt.% NaCl solution were firstly dispensed on the steel surface, with 40 nL in the first row, 36 nL in the second row, 32 nL in the third row, etc. (Fig. 9a). Water in the droplets evaporated rapidly due to the small volume and large specific area of the droplet, leaving the solute in solid state at the corrosion site (Fig. 9b). Finally, by adding 80 nL deionized water to each corrosion site, the solutes re-dissolved and the corrosive droplet microarray with different solute compositions was successfully prepared, with five parallel droplets for each concentration (Fig. 9c). The dispensing process of the droplet microarray with a pH of 3 or 10 was similar to that presented in Fig. 9, where the difference is that the remaining solutes were re-dissolved with corresponding HCl or NaOH solutions instead of deionized water. The steel sheet was then kept at ambient temperature with 100% relative humidity for 2 h (Supplementary Fig. S4), where corrosion reactions initiated and accordingly corrosion products were formed on the steel surface.

Automated detection and analysis of corrosion sites

The 3D morphology of each high-throughput corrosion site on the steel surface was characterized using CLSM (VK-X, Keyence). A computer vision-based program incorporating the Canny filter was developed to enable CLSM to automatically detect, localize and record the morphological characteristics of the corrosion sites with high precision19. In the 3D topography of each corrosion site, the height of the substrate outside the droplet coverage area was defined as the reference plane (0 μm). In order to mitigate the possible influence of slight polishing scratches, only the volume (V) of the corrosion products above 5 μm of the reference plane was recorded, while the corrosion area (S) with a height of 5 μm was also documented during measurements (Supplementary Fig. S5). The average height of corrosion products per area (H) generated on different corrosion sites was further calculated by dividing the volume of corrosion products by the corrosion area (H = V/S). Compared with the traditional method of artificially preparing different-concentration solutions, dispensing droplets and characterizing corrosion sites one by one, the combination of high-throughput droplet microarray preparation and automated corrosion sites characterization could significantly improve the experimental efficiency and precision.

The morphology and composition of corrosion products generated in specific droplets were further characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, MIRA, TESCAN) and Raman spectrometer (iRaman plus 785 s, Switzerland) of 785 nm laser wavelength.

Finite element modeling of droplet corrosion

To further understand the underlying mechanism of droplet corrosion occurred on the carbon steel, FEM was used with the model geometry presented in Fig. 10. The geometry was developed with two dimensions. One was identical to the actual dimension of the droplet with a diameter of 400 μm and a height of 250 μm. The other was larger than the actual droplet to exhibit a more pronounced localized effect, with a diameter of 7 mm and a height of 5 mm. The entire outer surface of the droplet was set as the gas-liquid exchange interface, which accounted for oxygen transport from the ambient environment to the inside of the droplet (CO2 = 0.18 mol·m−3)20. The bottom boundary in contact with the carbon steel substrate was set as the electrode surface, where localized electrochemical reactions were shown in the following equations. It should be noted that the specific cathode or anode regions were not artificially set in this model, therefore both the anodic metal dissolution reaction and the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction could occur on the entire electrode surface. The local anode or cathode region would only appear when the current density of the cathode and anode was unbalanced, which was essentially the coupling results of electrode reactions, oxygen concentration cells and the influence of corrosion products.

Anodic reaction:

Cathodic reactions:

The kinetic parameters of the electrode reactions were obtained using the potentiodynamic polarization tests (Supplementary Figs. S6, S7). The variation of anode and cathode current density due to the coupling of the electrochemical reactions within the droplet are calculated based on the classical Butler–Volmer equation, which is presented as below52:

where \({i}_{0,a}\) and \({-i}_{0,c}\) are the exchange current densities for the anode and the cathode reactions, respectively; \({E}_{{eq},a}\) and \({E}_{{eq},c}\) are the equilibrium potentials for the anode and the cathode reactions, respectively; \({b}_{a}\) and \({b}_{c}\) are the Tafel slope for the anode and the cathode reactions, respectively; \({I}_{L}\) is the limited diffusion current density.

The total current density is also calculated by the sum of the cathode and anode current densities. Besides, the homogeneous reactions involved in the droplets and corresponding reaction equilibrium constants were summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The mass transfer process in the droplet was governed by Nernst-Planck equation, where the diffusion coefficients of the species in the droplet were listed in Supplementary Table S2. Particularly, Fe(OH)2 in the aqueous phase (Fe(OH)2,aq) firstly generated when Fe2+ reacted with OH−. When the local concentration of Fe(OH)2,aq exceeded its solubility in the droplet, Fe(OH)2,s precipitation occurred to form corrosion products on the electrode surface. The steric hindrance effect of the corrosion product precipitation was described by the surface coverage (\(\theta\), \(\theta \le 1\))52,53, which was artificially defined in Eq. (4). The inhibition effect of metal dissolution caused by corrosion product precipitation is modeled by multiplying the local current density of the anodic reaction by the fraction of uncovered surface (1-θ).

where ctot was the total molar concentration of corrosion products precipitated per unit surface area, cavailable was the molar concentration available for metal dissolution per unit surface area.

In addition, several assumptions were made during modeling for better calculational convergence29,30,54: (1) the condensation and evaporation processes of the droplets were not considered, (2) only the formation of Fe(OH)2,s was considered without further oxidation or conversion, (3) the anodic dissolution reaction was inhibited by the corrosion product precipitation, while the oxygen reduction reaction could still occur.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to their use in an ongoing study, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, Y., Mu, X., Dong, J., Umoh, A. J. & Ke, W. Insight into atmospheric corrosion evolution of mild steel in a simulated coastal atmosphere. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 76, 41–50 (2021).

Pei, Z. et al. Understanding environmental impacts on initial atmospheric corrosion based on corrosion monitoring sensors. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 64, 214–221 (2021).

Zhi, Y. et al. Improving atmospheric corrosion prediction through key environmental factor identification by random forest-based model. Corros. Sci. 178, 109084 (2021).

Koch, G. et al. Cost of corrosion. Trends in oil and gas corrosion research and technologies. 3-30 (2017).

Koch. G. et al. International Measures of Prevention, Application, and Economics of Corrosion Technologies Study (NACE International, 2016).

Hou, B. et al. The cost of corrosion in China. npj Mater. Degrad. 1, 4 (2017).

Hangarter, C. M. & Policastro, S. A. Electrochemical characterization of galvanic couples under saline droplets in a simulated atmospheric environment. Corrosion 73, 268–280 (2016).

Tang, X. et al. Atmospheric corrosion local electrochemical response to a dynamic saline droplet on pure Iron. Electrochem. Commun. 101, 28–34 (2019).

El-Mahdy, G. A., Al-Lohedan, H. A. & Issa, Z. Monitoring the corrosion rate of carbon steel under a single droplet of NaCl. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 9, 7977–7985 (2014).

Cole, I. S., Ganther, W. D., Furman, S. A., Muster, T. H. & Neufeld, A. K. Pitting of zinc: observations on atmospheric corrosion in tropical countries. Corros. Sci. 52, 848–858 (2010).

Zhang, X., He, W., Wallinder, I., Pan, J. & Leygraf, C. Determination of instantaneous corrosion rates and runoff rates of copper from naturally patinated copper during continuous rain events. Corros. Sci. 44, 2131–2151 (2002).

Cai, Y., Zhao, Y., Ma, X., Zhou, K. & Chen, Y. Influence of environmental factors on atmospheric corrosion in dynamic environment. Corros. Sci. 137, 163–175 (2018).

Schindelholz, E., Kelly, R. G., Cole, I. S., Ganther, W. D. & Muster, T. H. Comparability and accuracy of time of wetness sensing methods relevant for atmospheric corrosion. Corros. Sci. 67, 233–241 (2013).

Thierry, D., Persson, D., Luckeneder, G. & Stellnberger, K.-H. Atmospheric corrosion of ZnAlMg coated steel during long term atmospheric weathering at different worldwide exposure sites. Corros. Sci. 148, 338–354 (2019).

Evans, U. Oxygen distribution as a factor in the corrosion of metals. Ind. Eng. Chem. 17, 363–372 (1925).

Street, S., Cook, A., Mohammed-Ali, H., Rayment, T. & Davenport, A. The effect of deposition conditions on atmospheric pitting corrosion location under Evans droplets on type 304L stainless steel. Corrosion 74, 520–529 (2018).

Rahimi, E. et al. Atmospheric corrosion of iron under a single droplet: a new systematic multi-electrochemical approach. Corros. Sci. 235, 112127 (2024).

He, W. et al. Droplet size dependent localized corrosion evolution of M50 bearing steel in salt water contaminated lubricant oil. Corros. Sci. 208, 110620 (2022).

Ren, C. et al. High-throughput assessment of corrosion inhibitor mixtures on carbon steel via droplet microarray. Corros. Sci. 213, 110967 (2023).

Zhang, K. et al. Monitoring atmospheric corrosion under multi-droplet conditions by electrical resistance sensor measurement. Corros. Sci. 236, 112271 (2024).

Hao, L., Zhang, S., Dong, J. & Ke, W. Evolution of corrosion of MnCuP weathering steel submitted to wet/dry cyclic tests in a simulated coastal atmosphere. Corros. Sci. 58, 175–180 (2012).

Evans, U. The corrosion and oxidation of metals: scientific principles and practical applications, (1961).

McCafferty, E. Introduction to Corrosion Science (Springer, 2010).

Song, Y., Jiang, G., Chen, Y., Zhao, P. & Tian, Y. Effects of chloride ions on corrosion of ductile iron and carbon steel in soil environments. Sci. Rep. 7, 6865 (2017).

Mohammed, H. K. et al. Investigation of carbon steel corrosion rate in different acidic environments. Mater. Today: Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.03.792 (2023).

Garcés, P., Andrade, M. C., Saez, A. & Alonso, M. C. Corrosion of reinforcing steel in neutral and acid solutions simulating the electrolytic environments in the micropores of concrete in the propagation period. Corros. Sci. 47, 289–306 (2005).

Barmatov, E. & Hughes, T. Effect of corrosion products and turbulent flow on inhibition efficiency of propargyl alcohol on AISI 1018 mild carbon steel in 4 M hydrochloric acid. Corros. Sci. 123, 170–181 (2017).

He, F., Wang, X., Zhang, C., Hou, Y. & Liu, Y. Coupled effects of different sulfuric acid concentrations and treatment methods on the corrosion rate of concrete materials. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04696 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Numerical simulation and experimental verification on the kinetics of droplet corrosion of carbon steel. Electrochim. Acta 514, 145607 (2025).

Yin, L. et al. Numerical simulation of micro-galvanic corrosion of Al alloys: effect of density of Al(OH)3 precipitate. Electrochim. Acta 324, 134847 (2019).

Wang, Y., Yin, L., Jin, Y., Pan, J. & Leygraf, C. Numerical simulation of micro-galvanic corrosion in Al alloys: steric hindrance effect of corrosion product. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, C1035–C1043 (2017).

Yin, L., Jin, Y., Leygraf, C. & Pan, J. A FEM model for investigation of micro-galvanic corrosion of Al alloys and effects of deposition of corrosion products. Electrochim. Acta 192, 310–318 (2016).

Cole, I., Muster, T., Azmat, N., Venkatraman, M. & Cook, A. Multiscale modelling of the corrosion of metals under atmospheric corrosion. Electrochim. Acta 56, 1856–1865 (2011).

Ogunsanya, I. G. & Hansson, C. M. Influence of chloride and sulphate anions on the electronic and electrochemical properties of passive films formed on steel reinforcing bars. Materialia 8, 100491 (2019).

Xu, Y., He, L., Yang, L., Wang, X. & Huang, Y. Electrochemical study of steel corrosion in saturated calcium hydroxide solution with chloride ions and sulfate ions. Corrosion 74, 1063–1082 (2018).

Shi, L. et al. The change of cathode/anode roles and corrosion forms in 2024/Q235/304 tri-metallic couple with the variation of oxygen concentrations and area ratios. Corros. Sci. 184, 109400 (2021).

Shi, L. et al. Variations of galvanic currents and corrosion forms of 2024/Q235/304 tri-metallic couple with multivariable cathode/anode area ratios: experiments and modeling. Electrochim. Acta 359, 136047 (2020).

Marco, J., Gracia, M., Gancedo, J., Martin, M. & Joseph, G. Characterization of the corrosion products formed on carbon steel after exposure to the open atmosphere in the Antarctic and Easter Island. Corrs. Sci. 42, 753–771 (2000).

Sun, W., Liu, G., Wang, L., Wu, T. & Liu, Y. An arbitrary Lagrangian–Eulerian model for studying the influences of corrosion product deposition on bimetallic corrosion. J. Solid State Electr. 17, 829–840 (2012).

Wang, Y., Wang, W., Liu, Y., Zhong, L. & Wang, J. Study of localized corrosion of 304 stainless steel under chloride solution droplets using the wire beam electrode. Corros. Sci. 53, 2963–2968 (2011).

Li, S. & Hihara, L. H. The comparison of the corrosion of ultrapure iron and low-carbon steel under NaCl-electrolyte droplets. Corros. Sci. 108, 200–204 (2016).

Tsuru, T., Tamiya, K.-I. & Nishikata, A. Formation and growth of micro-droplets during the initial stage of atmospheric corrosion. Electrochim. Acta 49, 2709–2715 (2004).

Muster, T. H. et al. The atmospheric corrosion of zinc: The effects of salt concentration, droplet size and droplet shape. Electrochim. Acta 56, 1866–1873 (2011).

Wang, F., Wang, Z., Hai, C., Geng, Z. & Du, C. Study on corrosion behavior of carbon steel in typical atmospheric environment in Dazhou. Sichuan Electr. Power Technol. 47, 89–92 (2024).

Song, Z., Wang, Z., Wang, J., Peng, B. & Zhang, C. Atmospheric corrosion hebavior of Q235 steel in Northern Hebei Region. Mater. Mechnical Eng. 45, 46–51 (2021).

Li, S. & Hihara, L. H. In situ Raman spectroscopic identification of rust formation in Evans’ droplet experiments. Electrochem. Commun. 18, 48–50 (2012).

Wang, P. et al. Study of rust layer evolution in Q345 weathering steel utilizing electric resistance probes. Corros. Sci. 225, 111595 (2023).

Demoulin, A. et al. The evolution of the corrosion of iron in hydraulic binders analysed from 46- and 260-year-old buildings. Corros. Sci. 52, 3168–3179 (2010).

Neff, D., Bellot-Gurlet, L., Dillmann, P., Reguer, S. & Legrand, L. Raman imaging of ancient rust scales on archaeological iron artefacts for long-term atmospheric corrosion mechanisms study. J. Raman Spectrosc. 37, 1228–1237 (2006).

Li, Z. et al. Accelerated rust stabilization for weathering steels via a high-throughput approach. Corros. Sci. 244, 112645 (2025).

Yu, Q. et al. Layer-by-layer investigation of the multilayer corrosion products for different Ni content weathering steel via a novel pull-off testing. Corros. Sci. 195, 109988 (2022).

Sainz-Rosales, A. et al. Classic Evans’s drop corrosion experiment investigated in terms of a tertiary current and potential distribution. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 3, 270–280 (2022).

Koushik, B. G., Van den Steen, N., Mamme, M. H., Van Ingelgem, Y. & Terryn, H. Review on modelling of corrosion under droplet electrolyte for predicting atmospheric corrosion rate. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 62, 254–267 (2021).

Li, W. et al. Numerical simulation of carbon steel atmospheric corrosion under varying electrolyte-film thickness and corrosion product porosity. npj Mater. Degrad. 7, 3 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2025M770029), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFF0728902), and the Open Research Foundation of Southwest Technology and Engineering Research Institute (Grant No. HDHDW59CZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shiyao Du: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Chenhao Ren: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Lingwei Ma: Writing – review & editing, Validation. Zongbao Li : Methodology, Investigation. Dequan Wu: Methodology, Investigation. Kun Zhou: Methodology, Investigation. Jun Wang: Methodology, Investigation. Dawei Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, S., Ren, C., Ma, L. et al. High-throughput investigation and finite element modelling of atmospheric corrosion on carbon steel under varying droplets. npj Mater Degrad 9, 145 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00695-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41529-025-00695-3