Abstract

Therapeutic deep brain stimulation (DBS) rebalances local motor circuitry activity in Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, the mechanistic understanding of how DBS impacts global macroscale dynamic functional network states remains limited, particularly regarding its effects on motor and non-motor networks. To address this, we employed an algorithm for dynamic functional connectivity co-activation patterns (DFCCAP) based on fMRI data to identify intrinsic macroscale neural states in the brain of healthy elderly individuals. Furthermore, by conducting a statistical analysis of the spatiotemporal properties of these patterns under different acquisition parameters and regional parcellation resolutions, we demonstrated the reproducibility of the results. Building on this, we examined 27 PD patients to investigate abnormalities in these dynamic macroscale state patterns and explored the modulatory effects of subthalamic stimulation. Our findings revealed that DBS induces selective activation and inhibition of macroscale states within specific functional networks across the whole brain. These states were characterized by four distinct classes of dynamic functional connectivity co-activation patterns. Subthalamic stimulation modulated abnormal dynamic features in PD, facilitating a shift from extensive functional brain network engagement to motor network dominance. This study provides novel insights into the intrinsic mechanisms underlying brain dynamics modulated by subthalamic stimulation. These findings illuminate how motor function recovery is supported while highlighting potential trade-offs in non-motor functional networks. This research enhances our understanding of brain network dynamics in PD, providing a foundation for refining therapeutic strategies and exploring innovative approaches to treating brain disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The human brain is a highly complex dynamic system that constantly engages in intrinsic cortical neural activity, even during the resting state1,2,3. Resting-state cortical neural activity exhibits various macroscale states and dynamics, characterized by different distribution properties and interconversion probabilities, which are associated with specific physiological or behavioral states4,5,6. They are influenced by the dynamic characteristics of cortical neural activity across different brain regions at the macro level as well as the functional connectivity of the entire brain5,7,8,9. However, the generalization of these recurrent brain activity macroscale states and their accurate portrayal of the intrinsic internal states of the human brain are still not thoroughly explored, especially in Parkinson’s disease (PD), limiting our understanding of brain diseases and their therapeutic mechanisms. Unsurprisingly, it is critical and necessary to fill in the gaps in how deep brain stimulation (DBS) specifically alters these dynamic states.

In searching for the neural correlates of PD brain activity modulated by subthalamic stimulation, investigators typically examine connections between discrete brain regions rather than intrinsic functional network interaction rules that continue to reflect the dynamic brain activity process10,11,12,13. In view of the clear sign of motor function improvement in PD14,15, we hypothesized that dynamic brain activity is encoded by multiple macrostates with motor cortex as the seed interacting with multiple motor and non-motor functional networks, and that subthalamic stimulation improves motor symptoms in PD by changing the dynamics of interaction between motor and non-motor networks during dynamic brain activity. This may also be the root cause of the side effects of emotional, cognitive, and other non-motor function impairment in patients after receiving long-term subthalamic stimulation16,17,18,19,20.

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data have been widely utilized over the past few decades to study the human brain’s functional connectivity and innate functional organization21,22,23. Global functional connectivity analyses have identified resting-state functional brain networks comprising sets of time-dependent brain regions24,25,26. Recent empirical research has further revealed that there are brain dynamics in resting brain networks that constantly shape and reshape functional configurations, and that spatial patterns of functional connectivity evolve over time. The dynamic changes in functional connectivity patterns within these brain networks reveal the organizational function of brain development27,28, human behavior29, and the internal mechanisms of brain diseases30. Thus, understanding the covariation between spatial connectivity patterns and temporal factors might shed light on the neural basis of subthalamic stimulation that regulates the extensive functional network connectivity patterns of PD.

In this work, we propose the “Dynamic Functional Connectivity Co-activation Pattern” (DFCCAP) approach. DFCCAP is designed to extract stable and reproducible macroscale brain states from dynamic functional connectivity matrices, thereby systematically characterizing instantaneous co-activation patterns at the whole-brain level. To validate its robustness, we first assessed the reproducibility of the spatiotemporal characteristics of DFCCAP under different data acquisition parameters and brain parcellation schemes. Building on this, we conducted a two-stage analytical application: First, we compared dynamic metrics of DFCCAP states—such as frequency of occurrence, state duration, and fractional coverage—between healthy elderly individuals and PD patients during resting state, aiming to identify disease-related disruptions in network dynamics. Subsequently, using fMRI data acquired from PD patients under both on and off conditions of DBS, we quantitatively evaluated the modulatory effects of DBS on these DFCCAP dynamic features, thereby elucidating its potential network-level mechanisms of action. An overview of the study design is presented in Fig. 1.

We included two healthy groups and two groups of PD patients targeting STN, and one group (16 cases) used the same 1.5 T functional MRI scanning parameters as the PD patient cohort. The intrinsic dynamic functional connectivity co-activation patterns were calculated, and validated internal state categories were obtained using different cortical segmentation resolutions. We found that STN-DBS can regulate the dynamic pattern characteristics of functional brain networks in PD patients. The schematic diagram used in the figure was originally created by the author using the biorender tool and can be used for publication in the paper (there is no copyright conflict).

Results

Spatial DFCCAP in a healthy brain

Based on a healthy control cohort (composed of 16 people whose fMRI acquisition parameters were consistent with those of the PD group [see Methods and Group 2 in Fig. 1), the SMC-based DFCCAP macroscale states within the whole cerebral cortex were calculated to characterize the internal brain states of neural activity in a healthy brain. The DFCCAP set of this group was used as the basic reference for reproducibility and generalization of DFCCAP macrostates and for comparison with the results of PD patients in the DBS on/off state.

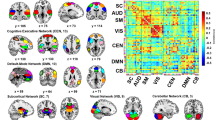

It is clear that the regions of interest (ROI) within the same functional brain network tend to be suppressed or activated synchronously, as shown in Fig. 2. Specifically, DFCCAP-1 showed that the somatomotor network (SMN), dorsal attention network (DAN), and ventral attention network (VAN) were activated, whereas the default mode network (DMN) and frontoparietal networks (FPN) were inhibited. In the DFCCAP-2 trial, the DMN, DAN, and FPN were activated, whereas the SMN and visual network (VN) were inhibited. DFCCAP-3 showed that the DMN, FPN, and limbic network (LN) were activated, while the SMN and VN were inhibited. DFCCAP-4 showed that the SMN and VN were activated, whereas the DMN and FPN were inhibited. Notably, the internal brain macrostates in the healthy cohort had SMN and DMN + FPN in opposite activity patterns simultaneously, i.e., the SMN was activated, whereas the DMN and FPN were inhibited, and vice versa. Moreover, the results of evaluating the spatial correlation between the DFCCAP macrostates showed no significant correlations among the four types of DFCCAP in the healthy elderly cohort (Supplementary Fig. S2 of the Supplementary File), indicating that there were four classes of specific internal brain macroscale states that did not repeat with each other in the normal human brain.

The Z-score of each ROI indicates the degree of activation or inhibition relative to the baseline neural activity. For example, a Z-score of ROI greater than 0 indicates that the average activity intensity of the region is greater than the overall baseline activity intensity, meaning the ROI is active.

In this study, the reproducibility of four DFCCAP macroscale states based on the SMC seed in the normal human brain was verified at different cortico-cerebral resolutions. Specifically, this study used a healthy control group with fMRI data acquisition parameters consistent with those of PD patients as the research cohort. Schaefer’s 400-ROIs cortical-brain region division rule was used as the standard segmentation scheme for subsequent studies and for comparing parameters between groups. In addition, for the healthy control group, standardized functional connectivity maps were calculated using the 100, 200, and 800 Schaefer ROI cortical partitioning schemes as independent groups, according to the above procedure (Methods). Pearson’s spatial correlation was calculated between the DFCCAP macrostates obtained from the three groups and the 400-ROI group, and the reproducibility of the four DFCCAP classes was verified.

Reproducibility performance

As shown in Fig. 3a, four independent and distinct DFCCAP macroscale states were obtained using Schaefer’s four cortical-brain cutting schemes with ROI resolutions of 100, 200, 400, and 800. The brain spectra of the activation/inhibition distribution for the same type of DFCCAP were significantly similar across different ROI resolutions (each column of the DFCCAP topographic map in Fig. 1). In addition, compared with the 400-ROI group, the 100-ROI group showed a more concentrated distribution of functional brain networks in activation/inhibition, with greater intensity of activation/inhibition activity. In contrast, the four DFCCAP classes obtained in the 200- and 800-ROI groups were closer to those in the 400-ROI group. The above results indicate that the four classes of SMC-based DFCCAP macroscale states obtained in this study are stable and repeatable in healthy controls under the segmentation rules of different ROI resolutions. This demonstrates the reproducibility of these four distinct internal brain states, which are non-repetitive and specific.

Based on the reproducibility of the four DFCCAP states with different cortical region segmentation resolutions, this study further explored whether the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics of the DFCCAP state sequences obtained by matching the original functional connectivity activation map to specific DFCCAP state classes under the cortical brain region segmentation rules with 100, 200, 400, and 800 ROI resolutions differed between groups. If the resolution of cortical brain region segmentation does not affect the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics of DFCCAP states in the healthy control group, this indicates that the four types of DFCCAP states demonstrate the reproducibility of internal brain states and uniform spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics, thereby showing the reproducibility of spatiotemporal dynamic characteristics.

The intergroup reproducibility verification results of the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution feature parameters for the different cortical brain region segmentation resolutions are shown in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table S3. Under various DFCCAP states, the feature parameters (1) occurrence frequency, (2) total proportion, and (3) duration did not show significant inter-group differences (p > 0.05), indicating that the resolution of cortical brain region segmentation did not affect the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics of DFCCAP states in the healthy control group. In other words, this study proved that the spatiotemporal dynamic characteristics of the healthy elderly human brain, with four typical cortical functional connectivity based on SMC seed points as internal brain states, have excellent reproducibility.

Generalization performance

In this study, we included another healthy control cohort, healthy control group 1, with different fMRI data collection parameters (as a standalone dataset, used only to validate mode generalization and not for subsequent analysis; see Methods and Group 1 in Fig. 1) to verify the generalization of the four classes of DFCCAP macroscale states. First, based on the same calculation steps, the optimal number of K-means cluster categories was independently calculated for the healthy control group 1 and healthy control group 2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. The optimal number of clusters for both groups was w4. Second, Pearson’s spatial correlation between the DFCCAP maps obtained from the two independent queues was calculated, and the generalizability of four DFCCAP macrostates based on SMC seed points was verified.

As shown in Fig. 4a, healthy control group B exhibited four independent and distinct types of SMC seed-based DFCCAP macroscale states, similar to those in healthy control group A, which was composed of 16 participants, and the activation/inhibition of functional brain networks corresponding to each DFCCAP was similar. Specifically, the spatial correlation results between the two pairs are shown in Fig. 4b. The spatial correlation between each DFCCAP in the two groups shows that each DFCCAP has only one macroscale state that is significantly similar to it. These results indicate that the four classes of non-repetitive DFCCAP obtained in this study, based on the healthy elderly cohort, express specific internal brain states that are stable in the brains of the healthy elderly group and demonstrate significant generalizability.

The generalized verification results of the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristic parameters of the healthy control group under different collection parameters are presented in Fig. 4b. The characteristic parameters of the different healthy elderly groups were as follows: (1) frequency of occurrence (/s), (2) state duration (s), and (3) fractional coverage (%) did not differ significantly between the groups (p > 0.05) indicating that there were similar spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics of the DFCCAP macroscale states among the different healthy control groups, as shown in Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table S4. Overall, this study demonstrated that the inherent spatiotemporal dynamic states of the brain in healthy elderly individuals are characterized by four classes of typical cortical DFCCAP macroscale states based on SMC-seed, validated through excellent reproducibility and generalization performance across different cohorts.

DBS regulates the DFCCAP macroscale state distribution in Parkinson’s disease

After completing the SMC-based DFCCAP macrostate cluster analysis in the 16 healthy control participants in this study, the four classes of CAP states were mapped to each standardized original functional connectivity activation map under the on/off state of DBS in each patient with PD. By evaluating three characteristic indicators of the dynamic activity of these internal brain states, we quantified the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics of the four types of DFCCAP macrostates based on the SMC seed: (1) frequency of occurrence (/s), (2) fractional coverage (%), and (3) state duration (s). First, the regulatory effect of the STN-DBS on the dynamic activity of the internal brain states in PD patients was explored, as shown in Fig. 5 and Table 1.

Specifically, when STN-DBS was turned off, the occurrence frequency of DFCCAP-1, DFCCAP-3, and DFCCAP-4 macroscale states in PD patients was significantly higher than in the healthy control group, and the duration of DFCCAP-4 was significantly lower than the healthy level, while the three spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics parameters of DFCCAP-2 didn’t show any significant abnormalities. After STN-DBS was turned on, the occurrence frequency of abnormal DFCCAP-3 and DFCCAP-4 macroscale states in PD patients was recovered, as shown in Fig. 5. In addition, STN-DBS had a significant remodeling effect on brain functional network dynamics, mainly reflected in the DFCCAP-1, DFCCAP-2, and DFCCAP-4 macroscale states. Specifically, STN-DBS significantly reduced the occurrence frequency, fractional coverage, and state duration of DFCCAP-1 and decreased the occurrence frequency and fractional coverage of DFCCAP-2, whereas the fractional coverage and state duration of DFCCAP-2 significantly increased. This indicated that the DFCCAP-1 and DFCCAP-4 macroscale states in PD patients were significantly reduced, whereas the DFCCAP-2 was significantly increased in PD patients induced by STN-DBS. However, STN-DBS stimulation in PD patients did not regulate the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution of all DFCCAP macroscale states; for example, STN-DBS had no significant effect on the duration of DFCCAP-4. Table 1 presents these statistics.

In general, PD patients showed abnormal frequency of occurrence and state duration when DBS was turned off, whereas the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution of DFCCAP macroscale states partially or completely returned to healthy levels when DBS was turned on. That is, the overall distribution range of the parameters was close to or reached the parameter values of the healthy control group. In addition, some parameter values show that when the DBS is turned on, the corresponding characteristic parameters are adjusted to be significantly different from both the DBS-off state and the healthy control state.

The state transition probability of DFCCAP macroscale states in healthy elderly subjects and PD patients, with STN-DBS on and off, describes the DFCCAP state transition characteristics of PD (Fig. S4 in the supplementary file) and the regulatory effects of STN-DBS (Fig. 6a). Overall, STN-DBS restored the abnormal transition probability of DFCCAP macroscale states in PD patients and reshaped multiple-state transition configuration rules. Specifically, compared to the healthy control group, the transition probability of DFCCAP-4 to DFCCAP-1 in PD patients was significantly increased (p = 0.012, Z = −3.371), and the transition probability between those macrostates was significantly reduced (p = 0.022, Z = −2.990). In addition, STN-DBS induced a remodeling effect on various state transitions, as shown in Table 2. The transition probability of the DFCCAP-1 state to itself and the DFCCAP-3 state, as well as the transition probability of DFCCAP-2, DFCCAP-3, and DFCCAP-4 to DFCCAP-1 decreased significantly.

a The red line represents an increase in the state transition, the blue line represents a decrease in the state transition, the green line represents a relief in the state transition, and the gray line represents no significant differences between the groups; b DBS induced the decrease of DFCCAP-1 and the increase of DFCCAP-2; c Subthalamic stimulation modulates abnormal dynamic characteristics in PD, indicating a shift from extensive functional brain network support to motor network dominance.

Additionally, the transition probability of other states to DFCCAP-1 was significantly reduced by STN-DBS. At the same time, STN-DBS significantly increases the transition probabilities of DFCCAP-4 to DFCCAP-2 and the transition probabilities within DFCCAP-2. The above phenomena indicate that STN-DBS can significantly regulate the dynamic transition characteristics between abnormal DFCCAP macroscale states in PD patients to restore their health level and has a significant reshaping effect on the dynamic transition characteristics between broader DFCCAP macroscale states, as manifested by a shift from DMN and FPN supporting SMN activities to stronger SMN internal connectivity (Fig. 6b, c). Emphasizing that subthalamic stimulation modulates abnormal dynamic characteristics in PD, indicating a shift from extensive functional brain network support to motor network dominance.

The Spearman’s correlation between changes in the spatiotemporal dynamic characteristics of DFCCAP macroscale states induced by STN-DBS and the improvement rate of clinical motor symptoms is shown in Fig. 7a–c. According to the Uniform Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-III (UPDRS-III), significant correlations were detected between (1) changes in the frequency of DFCCAP-1, (2) changes in the total proportion of DFCCAP-3, and (3) changes in the duration of DFCCAP-2 induced by STN-DBS, and the rate of improvement in motor symptoms severity. Specifically, the change in the frequency of DFCCAP-1 after STN-DBS activation was positively correlated with improvement in bradykinesia (p = 0.013, R = 0.547). The total proportion of DFCCAP-3 was positively correlated with improvement in speech (p = 0.040, R = 0.488). Changes in the duration of DFCCAP-2 were inversely associated with improvements in action tremors (p = 0.037, R = -0.403). In addition, compared to PD patients without STN-DBS, no significant correlation was observed between changes in the spatiotemporal dynamic distribution characteristics of other DFCCAP macroscale states and the improvement rate of motor symptom severity after DBS was turned on.

The Spearman’s correlation between the changes in the probability of DFCCAP state transition induced by STN-DBS and the improvement rate of clinical motor symptoms is shown in Fig. 7d. There was a significant positive correlation between the change in the probability of the DFCCAP-2 state transitioning to the DFCCAP-1 state induced by STN-DBS and the improvement rate of clinical motor symptom severity. Specifically, when STN-DBS was turned on, the transition probability of the PD patients’ internal brain state from DFCCAP-2 to DFCCAP-1 was reduced, and the symptoms of bradykinesia improved (p < 0.001, R = 0.695). In addition, no significant correlation was observed between the change in the probability of state transitions between other DFCCAP macroscale states and the rate of improvement in motor symptom severity after DBS was turned on, compared to PD patients with STN-DBS off.

Discussion

This study decoded four macrostates of cortical brain activity that describe the activity dynamics of cortical functional brain networks serve as inherent brain states. Importantly, the inherent brain states decoded in this study exhibit robust reproducibility and generalizability. The inherent states were mapped to the original functional connectivity activation maps of the cortical functional brain network in PD patients under the STN-DBS on- and off-states, respectively, revealing the regulatory mechanism of DBS with different targets on the dynamic activity of the functional brain network in PD patients.

Over the past decade, co-activation pattern analysis based on fMRI data has been used to explore internal brain states that alternate and follow specific dynamic distribution rules31,32,33,34,35. Liu and Duyn developed a classical voxel co-activation pattern research method based on the posterior cingulate gyrus as the seed point and found that the DMN in the human brain has a time-varying spatial pattern36. Furthermore, researchers adopted ROI-based co-activation pattern analysis and identified an internal state with opposite activation rules in the human brain9. In recent years, the exploration of repeatable and stable inherent brain states has become an important topic of attention in brain science and other fields37,38. In this study, the reproducibility and generalization of the four DFCCAP macrostates were proven from the perspectives of different cortical spatial resolutions and different fMRI acquisition cohorts. The results showed that the four typical inherent brain states in this study were stable, and their dynamic characteristics met the requirements of reproducibility and generalization in included healthy elderly individuals. DBS reduces this compensatory response in PD patients and returns motor function to the activation of the motor network, showing functional centrality. In addition, recent studies have shown that DBS and dopamine have similar functions; that is, they accelerate the response of neural activity in the initial stages of movement, which is reflected in our study by the transformation of the activation characteristics of connections between brain networks.

In this study, a reproducible and generalized DFCCAP analysis algorithm was applied to PD patients to explore the abnormal dynamic characteristics of pathological DFCCAP macrostates in PD patients compared with healthy controls and the regulatory mechanism of DBS on the dynamic characteristics of DFCCAP macrostates. We found that although the total time proportion of various DFCCAP macrostates in PD patients was not significantly different from that in healthy subjects, these DFCCAP macrostates exhibited more frequent switching in the brain dynamic activity of PD patients, and the duration of each macrostate was shorter. This finding indicates that the dynamic brain activity of PD patients has more frequent functional connectivity fluctuations and instability in the functional connectivity network, similar to the dynamic rule of switching between two types of dense functional connectivity modes found in Kim et al.’s study on the dynamics of the internal brain functional network in PD patients39. Moreover, the findings of this study confirm the vulnerability of the functional connectivity network of the resting brain to neurodegenerative diseases40,41,42.

The regulatory effect of STN-DBS on inherent brain states in PD patients was mainly manifested as restoration of the frequency of DFCCAP-3 and DFCCAP-4 macrostates, but the amount of change was not significantly related to the improvement of clinical motor function. More importantly, the regulatory effect of STN-DBS was reflected in the reshaping of the dynamic characteristics of DFCCAP-4. STN-DBS significantly reduced the proportion of the DFCCAP-1 state in dynamic brain activity during scanning, as shown by the lower frequency, duration, and total proportion. The conversion probability of other macrostates to DFCCAP-1 was also significantly reduced. In addition, DFCCAP-4 showed a significant reduction in frequency, total proportion, and conversion probability. At the same time, during STN-DBS stimulation, there was a significant increase in DFCCAP-2, manifested by a longer duration and a higher total proportion. The STN-DBS increases functional connectivity to the SMC network, implying that voluntary movement in patients is improved with DBS stimulation due to this effect. In addition, DMN connectivity was reduced, which tells us to improve movement in PD patients, this network needs to be inhibited. The prokinetic aspect benefits voluntary movement, and the inhibition of the DMN suppresses involuntary movement.

The macrostate DFCCAP-2 showed that the SMC had strong functional connectivity with the sensorimotor network but weak functional connectivity with the DMN. In contrast, DFCCAP-1 showed that the SMC had strong functional connectivity with the DMN but weak functional connectivity with itself. Based on the dynamic characteristics, the results showed that STN-DBS reduced the functional connectivity between the SMC and DMN while transitioning into a state of strong functional connectivity within the SMC in the dynamic brain activity of PD patients. Previous studies have shown that alterations in SMC activation or connectivity are correlated with motor planning ability rather than with actual motor execution ability43,44. On the other hand, increased connectivity in the DMN, particularly the ability to redirect attention processes from self-reflective to goal-directed behavior45, may suggest that higher functional connectivity between the SMC and DMN represents an initial cognitive compensatory response associated with changes in motor function in PD. Functional compensation as a manifestation of cognitive cortical plasticity has been demonstrated not only in PD46,47,48, but also in other neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that STN-DBS shifts the internal brain states of PD patients, that is, in the PD state, increased mental effort expenditure is necessary to maintain the same level of motor function performance and STN-DBS switches this state into internal motor capacity. The clinical correlation analysis of this study confirmed this hypothesis by showing the correlation between the dynamic characteristics of the internal brain state and bradykinesia and motor tremor, respectively (i.e., the more the frequency of occurrence of the DFCCAP-1 state decreases, the more the probability of transition from the DFCCAP-2 to the DFCCAP-1 state decreases, the higher the improvement rate of bradykinesia, and the higher the rate of improvement of bradykinesia). Simultaneously, the greater the duration of the DFCCAP-2 state, the higher the rate of improvement in motor tremor. Therefore, we can explain the complex symptom behavior in PD patients. The interplay between increased SMN network connectivity and decreased DMN connectivity explains this paradox in PD patients. Specifically, movement speed is increased by the SMC, and the interaction of the somatosensory cortex with the DMN reduces involuntary tremors in PD.

Our findings indicate that STN-DBS reduces abnormal functional connectivity patterns and restores the dominance of the motor network. This is consistent with previous research findings: from the perspective of the loop, studies have shown that DBS improves motor symptoms by regulating the basal ganglia-thalamus-cortex loop4; from the perspective of brain networks, a PET study on DBS treatment for PD indicates that DBS can correct abnormal motor network activities49. However, our use of DFCCAP provides more granular insights into how these changes occur dynamically across different brain states. In addition, in contrast to earlier studies that suggested DBS primarily affects motor circuits, our results indicate that DBS has widespread effects on global brain networks, particularly shifting the balance between motor and non-motor networks. This divergence could be due to our use of dynamic functional connectivity measures, which capture temporal fluctuations not accounted for in static analyses. Overall, our study reveals that subthalamic stimulation can modulate abnormal dynamic characteristics in PD, indicating a shift from extensive functional brain network support to motor network dominance.

Our research findings reveal a more complex effect than normalization: we did observe evidence of partial normalization. Specifically, the regulatory effect of STN-DBS was manifested as a restoration of the aberrant occurrence frequencies of the DFCCAP-3 and DFCCAP-4 macrostates in PD patients to levels more closely resembling those seen in healthy controls. This finding indicates that DBS does correct certain specific abnormalities in brain network dynamics associated with PD. However, our further analysis revealed that the extent of this restoration in frequency of occurrence was not significantly correlated with the improvement in clinical motor function. This key result suggests that simple “normalization” is likely insufficient to explain the therapeutic effects of DBS. Instead, it strongly implies that STN-DBS operates through a mechanism of functional remodeling. In other words, rather than merely “resetting” the brain to a pre-disease pattern, DBS may help the brain reconfigure its functional networks into a new, more efficacious dynamic equilibrium that bypasses the network dysfunction caused by the disease. This remodeled state may be qualitatively different from the baseline state of a healthy brain but is functionally optimized to support improved motor performance. In conclusion, our study supports a multi-modal effect of STN-DBS on brain network dynamics: it involves the partial restoration of certain abnormal metrics, but more importantly, it drives a predominant process of adaptive remodeling. The latter is likely the primary mechanism underlying the alleviation of motor symptoms. This understanding frames the mechanism of DBS not just as “restoring normality” but as “guiding the brain into a new, functionally superior operational state”, which aligns with the growing perspective in neuromodulation that emphasizes network reconfiguration over simple normalization.

Moreover, our results indicated that the specific spatial maps of the identified DFCCAPs did show some variation with the change in window length (as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4). This finding is consistent with previous studies which suggest that the choice of window length can influence the captured dynamics, as different windows act as filters that emphasize temporal fluctuations at different scales50,51. Different window lengths may be preferentially sensitive to distinct neural processes operating at various timescales. The patterns we identified with our original window are robust representations of sustained co-activation states within the network at that specific temporal scale. The variation observed with a different window does not invalidate our main findings but rather complements them by suggesting that the network also exhibits dynamic behaviors at other timescales worthy of future investigation.

Prior research primarily focused on static network changes10, while our study introduces novel insights into the temporal dynamics of these shifts. For instance, we observed that STN-DBS not only reduces abnormal co-activation patterns but also selectively enhances motor-related network activity while suppressing default mode network activity—a finding not previously reported. Still, this work has inspired us that subthalamic stimulation has a significant motor tilt effect on motor and non-motor networks, but has failed to fully explain the quantifiable features of DBS on emotional, cognitive, and other non-motor networks, we will continue to explore the long-term motor and non-motor cross-action mechanism of DBS. In addition, future studies with larger cohorts are necessary to confirm the reliability and generalizability of these results and to further investigate the deeper mechanisms underlying this remodeling effect. Moreover, although we have taken the utmost measures to ensure the safety of patients during the MRI scanning process when the DBS system is either turned on or off, it is necessary to pay attention to the specific equipment model and operational details of the method, and this is only applicable to the system used in this study.

Methods

Participants

This study included 27 patients (6 females and 21 males; aged 64.8 ± 7.6 years) with PD who underwent STN DBS, and these patients were right-handed individuals with idiopathic PD received two quadrupole DBS electrodes (Medtronic 3387, Medtronic, USA; SceneRay 1210, SceneRay, China). We confirm that all experiments were conducted with the utmost regard for safety. The DBS systems used are MRI-conditional. All of the PD patients included in the study had a monopolar electrical configuration. Although only bipolar stimulation during MRI acquisition is recommended by the DBS vendor guidelines (http://mriquestions.com/uploads/3/4/5/7/34572113/dbs_medtronics_contrib_228155.pdf), we specifically used the native stimulation settings (monopolar stimulation) according to a successful application research52. Moreover, during the entire MRI scan process under the condition of DBS on, the specific absorption rate (SAR) value indicating safety was continuously monitored and remained within the safe range. Additionally, the clinician verified that none of the study participating patients developed complications related to MRI scanning during the course of the follow-up.

Disease severity was assessed using the Motor Part of the Movement Disorders Society (MDS) UPDRS-III53. The study excluded patients with excessive tremors during DBS and drug cessation, other serious psychiatric disorders meeting the DSM-5 criteria (such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder), major neurological disorders, unstable vital signs, or any postoperative complications detected on postoperative MRI. The Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital (Shanghai, China) approved all procedures for this study (approval number: 2018017). All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Details of the PD patients can be found in our previous study10.

To verify the reproducibility and generalizability of the DFCCAP macroscale states proposed in this study, we included two independent fMRI datasets of healthy elderly individuals (Group 1: 15 females and 15 males; aged 57.0 ± 5.5 years; Group 2: 8 females and 8 males; aged 60.3 ± 7.4 years), distinguished by different magnetic field strengths (Group 1 with a 3T fMRI scanner and Group 2 with a 1.5T fMRI scanner, as shown in Fig. 1). An analysis of group differences by age and sex is provided in the Supplementary file (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). In this study, the algorithm was applied to the fMRI dataset of PD patients, with DBS on and off, to explore the specific indicators of PD and the regulatory mechanism of DBS. In addition, the healthy elderly group with fMRI collection parameters consistent with those of the fMRI collection parameters of the patient with PD group and matching in age and gender was selected as the reference group for statistical analysis with the patient with PD group. A two-sample t-test was used for age differences, and a chi-square test was used for sex differences. p < 0.05.was considered statistically significant.

Clinical assessment

The MDS UPDRS-III scale scores were used to evaluate disease severity. Specifically, the evaluation process for patients with DBS on and off was as follows. An experienced neurologist performed an initial clinical assessment over the phone a few days before the scan. On the day of the fMRI scan, the patient was in an overnight discontinuation state, and the motor function in the DBS-on state was assessed by a movement disorder specialist using the UPDRS-III. After the fMRI scan was performed with the DBS on, it was turned off, and participants waited for an hour or until the motor symptoms reappeared for a second motor function assessment, followed immediately by an fMRI scan in the DBS-off state. Clinical scale improvement rates were measured by the percentage change in the UPDRS-III score between the DBS-on and DBS-off states. The demographics, clinical characteristics and stimulation parameters are shown in the Supplementary Material. The process of eliminating fMRI voxels exhibiting severe magnetic susceptibility artifacts caused by the DBS apparatus is described in our previous study10.

Functional MRI data acquisition

Structural MRI and resting-state BOLD data from healthy controls and postoperative structural MRI and resting-state BOLD data from patients with Parkinson’s were obtained using a 1.5 T Siemens magnetic resonance scanner (Aero, Siemens, Germany). The MP-RAGE image acquisition sequence was adopted for T1-weighted structural images, with the following parameters: repetition time = 3400 ms, echo time = 3 ms, inversion time = 900 ms, inversion Angle = 8°, voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3, matrix size = 224 × 216, number of layers = 192.

The image acquisition parameters of the resting-state function MR EPI were as follows: a total of 210 images were collected, repetition time = 2100 ms, echo time = 40 ms, turnover Angle = 90°, voxel size = 3.0 × 3.0 × 3.0 mm3, matrix size = 66 × 66, and number of layers = 37.

The dataset of healthy subjects used to validate the generalization of the algorithm and the internal state results in this study was obtained using a 3.0 T Philips magnetic resonance scanner (Ingenia, Philips, Netherlands). The MP-RAGE image acquisition sequence was adopted for T1-weighted structural images, and the parameters were as follows: repetition time = 7.0 ms, echo time = 3.2 ms, inversion time = 900 ms, inversion Angle = 7°, voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3, matrix size = 256 × 256, number of layers = 192.

The image acquisition parameters of the resting-state function MR EPI are as follows: a total of 240 images are collected, repetition time = 2000 ms, echo time = 30 ms, turnover Angle = 90°, voxel size = 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 mm3, matrix size = 256 × 256, and number of layers = 39.

Functional imaging data preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI data were processed using the Data Processing and Analysis of Brain Imaging (DPABI) toolbox (version 4.1; http://rfmri.org/dpabi). The first 10 volumes of functional images were excluded to eliminate unstable data. After slice timing correction, the images were realigned to correct for head movement. The functional images were normalized to the MNI space using the method of Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration Through Exponentiated Lie Algebra. Spatial smoothing was performed with a gaussian kernel of 6 × 6 × 6 mm3 fullwidth at half maximum. White matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals and Friston 24 head motion parameters were regressed out as nuisance covariates. A bandpass filter was used to extract signals between 0.009 and 0.08 Hz.

SMC-seed-based spatial dynamic functional connectivity co-activation pattern

In this study, the somatosensory motor cortex (SMC) was chosen as the seed because it is the hub network that could play a pivotal role in the derangement of networks in PD, and the SMC was found in our previous studies to be a response region where DBS significantly improved motor function10. Seed-point-based DFCCAP analysis is a BOLD signal analysis based on each region of interest (ROI). The objects analyzed in this study were cortical brain regions composed of 400 ROIs from the Schaefer cortical segmentation54. These cortical regions correspond to the seven functional brain networks of Yeo-201155, namely, the VN, MN, DAN, DAN, VAN, LN, FPN, and DMN, as shown in Fig. 1.

The cortical brain regions of the healthy elderly group (the control group, with the same collection specifications as the PD patient group) were re-divided into 100, 200, 400, and 800 ROIs according to the Schaefer cortical segmentation rule to verify the reproducibility of the DFCCAP macroscale states. By verifying the repeatability of the DFCCAP macroscale states in the brains of healthy elderly individuals under different ROI resolutions, it was proven that the algorithm in this study can identify the stable inherent states of the healthy elderly brain.

Taking the entire cerebral cortex of healthy elderly group 2, divided into 400 ROI as an example, the DFCCAP analysis process based on SMC-seed was calculated. The specific calculation steps were as follows: (1) Extracting BOLD sequences from the 400 ROIs of the whole cerebral cortex and the SMC; (2) calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the signals of each ROI and the SMC based on a uniform sliding window with a window length of 20 sampling points56 and a step length of one sampling point, and then obtaining a dynamic functional connectivity matrix based on the seed points. For subject i, the matrix was expressed as xi (400 × n), where 400 represents the number of ROIs and n represents the number of sliding windows; (3) The Z-value was obtained using the fractional standardization method to standardize the amplitude of the dynamic functional connectivity matrix based on the SMC-seed, and the Z-value represented the relative strength change of dynamic functional connectivity; Xhc was used as an input for DFCCAP analysis; (5) The K-means clustering algorithm was used to calculate the N DFCCAP sub-states9, and the standardized original functional connectivity activation graphs of the N sub-states were assigned to the corresponding DFCCAP based on similarity.

In this study, correlation distances were used to evaluate the spatial similarity between the activation maps of the standardized original functional connectivity. For example, the spatial similarity between Xi1 and Xi2 was 1-corr (Xi1, Xi2), where corr denotes Pearson’s correlation., This study set the range of the number of clustering categories M from 1 to 10 with a step size of 1 to obtain the most suitable number of DFCCAP states. For each M, the K-means clustering process was repeated 100 times, and a new initial center point of each cycle was selected randomly. The clustering results with the least errors were selected for subsequent analysis9. The clustering results corresponding to each M in the range of 1 to 10 were evaluated using the silhouette score57. The optimal number of states was determined using the elbow method. As shown in the left panel of Supplementary Fig. S2, M = 4 was selected in this study. (6) The spatial DFCCAP for each group level was obtained by averaging all the original functional connectivity activation graphs clustered into the pattern and dividing by the standard deviation within the pattern group to obtain a standardized DFCCAP graph (composed of Z-values, size 400 × 1). (7) After obtaining the four types of DFCCAP states for the healthy control group by K-means clustering, Pearson’s correlation was used to calculate the spatial similarity between the activation maps of each standardized original functional connectivity and the DFCCAP states in the on-off state of DBS of PD patients obtained using the same analysis pipeline as above. The maps of each substrate were matched to the DFCCAP with the highest spatial similarity. The algorithm flow chart of this work is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1 of the supplementary file.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 25; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MATLAB (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). In this study, a paired-sample t-test was used to analyze the differences between the two groups based on the degree of centrality of whole-brain voxels. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the DFCCAP characteristic parameters between the groups of paired patients in the on-off state of DBS, and the Mann–Whitney test was used to assess DFCCAP parameter differences between the PD and control groups. If the p-value of the FDR after multiple comparisons is less than 0.05, it can be considered that there is a significant difference between the two groups. In addition, determining the seed area requires calculating the clinical correlation between the degree of centrality change between the two states of DBS on/off and the improvement rate of the total score on the MDS-UPDRS-III clinical scale. The Spearman’s correlation test was used to determine the clinical correlation between the change in DFCCAP characteristic parameters and the improvement rate of the MDS-UPDRS-III score. The test parameters met p < 0.05, indicating a significant correlation, and FDR multiple comparison corrections were performed. After multiple comparisons and corrections using the Gaussian random field (GRF) method embedded in the Viewer module of DPABI, the results were reduced to p < 0.05; an alpha level of 0.05 (2-tailed) was considered significant. Voxel maps generated within the range of the cerebral cortex were overlaid using the BrainNet Viewer (version 1.7, https://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/) tool, which provides a brain atlas in the template and the axial section view drawn by the DPABI Viewer module.

Data availability

The anonymized data used in this study are available online as a supplementary file.

Code availability

The code used in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Change history

14 January 2026

In this article the affiliation details for Chencheng Zhang were incorrectly given as ' Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China; Clinical Neuroscience Center, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, China ' but should have been ' Clinical Neuroscience Center, Ruijin Hospital Luwan Branch, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China'. The original article has been updated.

References

Kringelbach, M. L. & Deco, G. Brain states and transitions: insights from computational neuroscience. Cell Rep. 32, 108128 (2020).

Amoruso, L. et al. Decoding bilingualism from resting-state oscillatory network organization. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1534, 106–117 (2024).

Schwalm, M. et al. Functional states shape the spatiotemporal representation of local and cortex-wide neural activity in mouse sensory cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 128, 763–777 (2022).

Chu, C. G. et al. Subthalamic stimulation modulates motor network in Parkinson’s disease: recover, relieve and remodel. Brain 146, 2780–2791 (2023).

Chen, J. E., Chang, C., Greicius, M. D. & Glover, G. H. J. N. Introducing co-activation pattern metrics to quantify spontaneous brain network dynamics. NeuroImage 111, 476–488 (2015).

Choi, E. Y., Yeo, B. T. T. & Buckner, R. L. The organization of the human striatum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 108, 2242–2263 (2012).

Zalesky, A., Fornito, A., Cocchi, L., Gollo, L. L. & Breakspear, M. Time-resolved resting-state brain networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 10341–10346 (2014).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Intrinsic functional connectivity is organized as three interdependent gradients. Sci. Rep. 9, 15976 (2019).

Yang, H. et al. Reproducible coactivation patterns of functional brain networks reveal the aberrant dynamic state transition in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 237, 118193 (2021).

Zhang, C. C. et al. Subthalamic and pallidal stimulations in patients with Parkinson’s disease: common and dissociable connections. Ann. Neurol. 90, 670–682 (2021).

Hollunder, B. et al. Mapping dysfunctional circuits in the frontal cortex using deep brain stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 573–586 (2024).

Rajamani, N. et al. Deep brain stimulation of symptom-specific networks in Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 15, 4662 (2024).

Achtzehn, J. et al. Changes in functional connectivity relate to modulation of cognitive control by subthalamic stimulation. Human Brain Mapping 45, e70095 (2024).

Nakamura, K., Christine, C. W., Starr, P. A. & Marks, W. J. Effects of unilateral subthalamic and pallidal deep brain stimulation on fine motor functions in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 22, 619–626 (2007).

Aman, J. E., Abosch, A., Bebler, M., Lu, C. H. & Konczak, J. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation improves somatosensory function in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 29, 221–228 (2014).

Trost, W. et al. Subthalamic deep brain stimulation influences complex emotional musical experience in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia 117, 278–286 (2018).

Homer, M. A., Rubin, S. S., Horowitz, T. D. & Richter, E. Linguistic testing during ON/OFF states of electrical stimulation in the associative portion of the subthalamic nucleus. Neuromodulation 15, 238–245 (2012).

Radhakrishnan, D. M. & Goyal, V. Parkinson’s disease: a review. Neurol. India 66, S26–S35 (2018).

Bick, S. K. B. et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation alters prefrontal correlates of emotion induction. Neuromodulation 20, 233–237 (2017).

Reich, M. M. et al. A brain network for deep brain stimulation induced cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 145, 1410–1421 (2022).

Ogawa, S., Lee, T. M., Kay, A. R. & Tank, D. W. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast-dependent blood oxygenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9868–9872 (1990).

Vafaii, H. et al. Multimodal measures of spontaneous brain activity reveal both common and divergent patterns of cortical functional organization. Nat. Commun. 15, 229 (2024).

Logothetis, N. K. & Wandell, B. A. Interpreting the BOLD signal. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66, 735–769 (2004).

Hoheisel, L. et al. Alterations of Functional Connectivity Dynamics in Affective and Psychotic Disorders. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 9, 765–776 (2024).

Zhang, J. H. et al. What have we really learned from functional connectivity in clinical populations? Neuroimage 242, 118466 (2021).

Shen, L. H. et al. Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation modulates 2 distinct neurocircuits. Ann. Neurol. 88, 1178–1193 (2020).

Sun, H. L. et al. Brain age prediction and deviations from normative trajectories in the neonatal connectome. Nat. Commun. 15, 10251 (2024).

Dosenbach, N. U. F. Prediction of individual brain maturity using fMRI (vol 329, pg 1358, 2010). Science 330, 1358–1361 (2010).

Finn, E. S. et al. Functional connectome fingerprinting: identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1664–1671 (2015).

Hacker, M. L. et al. Connectivity profile for subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in early stage Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 94, 271–284 (2023).

Chu, C. Y. et al. Co-activation Probability Estimation (CoPE): an approach for modeling functional co-activation architecture based on neuroimaging coordinates. Neuroimage 117, 397–407 (2015).

Ke, M., Hou, L. & Liu, G. Y. The co-activation patterns of multiple brain regions in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy. Cogn. Neurodyn 18, 337–347 (2024).

Cohen, A. D., Chang, C. T. & Wang, Y. Using multiband multi-echo imaging to improve the robustness and repeatability of co-activation pattern analysis for dynamic functional connectivity. Neuroimage 243 (2021).

Chen, J. E., Chang, C., Greicius, M. D. & Glover, G. H. Introducing co-activation pattern metrics to quantify spontaneous brain network dynamics. Neuroimage 111, 476–488 (2015).

Eickhoff, S. B. et al. Co-activation patterns distinguish cortical modules, their connectivity and functional differentiation. Neuroimage 57, 938–949 (2011).

Liu, X. & Duyn, J. H. Time-varying functional network information extracted from brief instances of spontaneous brain activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 4392–4397 (2013).

Botvinik-Nezer, R. et al. Variability in the analysis of a single neuroimaging dataset by many teams. Nature 582, 84 (2020).

Cao, J., Ball, I., Humburg, P., Dokos, S. & Rae, C. Repeatability of brain phase-based magnetic resonance electric properties tomography methods and effect of compressed SENSE and RF shimming. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 46, 753–766 (2023).

Kim, J. et al. Abnormal intrinsic brain functional network dynamics in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 140, 2955–2967 (2017).

Deco, G., Jirsa, V. K. & McIntosh, A. R. Emerging concepts for the dynamical organization of resting-state activity in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 43–56 (2011).

Kucyi, A., Hove, M. J., Esterman, M., Hutchison, R. M. & Valera, E. M. Dynamic brain network correlates of spontaneous fluctuations in attention. Cereb. Cortex 27, 1831–1840 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. Default mode network mediates low-frequency fluctuations in brain activity and behavior during sustained attention. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 5478–5489 (2022).

Giordano, A. et al. Functional connectivity underpinnings of fatigue in “drug-naive” patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 31, S398–S398 (2016).

Esmaeili, V. et al. Rapid suppression and sustained activation of distinct cortical regions for a delayed sensory-triggered motor response. Neuron 109, 2183 (2021).

Deiber, M. P., Ibanez, V., Sadato, N. & Hallett, M. Cerebral structures participating in motor preparation in humans: a positron emission tomography study. J. Neurophysiol. 75, 233–247 (1996).

Gorges, M. et al. To rise and to fall: functional connectivity in cognitively normal and cognitively impaired patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1727–1735 (2015).

Nonnekes, J., Tibben, M., van de Venis, L. & Bloem, B. R. Functional freezing of gait: lessons from compensation. Pract. Neurol. 24, 161–164 (2024).

Zhou, C. et al. Structural covariance network disruption and functional compensation in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 199 (2020).

Eckert, T., Tong, C. & Eidelberg, D. Assessment of the progression of Parkinson’s disease: a metabolic network approach. Lancet Neurol. 6, 926–932 (2007).

Tan, J. -w, Wang, L. -x & Zhu, Z. -h Entropy of information based dynamic Allan variance algorithm with adaptive window Length. Electron. Opt. Control 24, 47-49–47-68 (2017).

Kirsch, W. & Kunde, W. The size of attentional focus modulates the perception of object location. Vis. Res. 179, 1–8 (2021).

Boutet, A. et al. Predicting optimal deep brain stimulation parameters for Parkinson's disease using functional MRI andmachine learning. Nat. Commun. 12, 3043 (2021).

Antonini, A. et al. Validation of the Italian version of the movement disorder society-unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Neurological Sci. 34, 683–687 (2013).

Schaefer, A. et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb. Cortex 28, 3095–3114 (2018).

Buckner, R. L., Krienen, F. M., Castellanos, A., Diaz, J. C. & Yeo, B. T. T. The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 2322–2345 (2011).

Patil, A. U. et al. Static and dynamic functional connectivity supports the configuration of brain networks associated with creative cognition. Sci. Rep. 11, 165 (2021).

Rousseeuw, P. J. A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 20, 53–65 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 82401483 and 62173241, the funding of STI2030-Major Projects+2022ZD0205300 and open research fund of Key Laboratory of Machine Intelligence and System Control, Ministry of Education(No.MISC-202404), the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number GZC20230529 and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant Number 2023M740711.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chencheng Zhang conducted the experiment and collected all the datasets. Chunguang Chu and Chen Liu designed the study. Chunguang Chu analyzed all datasets, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. Zhen Zhang, Jiang Wang, Yuxin Wang, Hao Ding and Muthuraman Muthuraman interpreted the data and optimized the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.Z. serves as an Associate Editor and Muthuraman Muthuraman as an Deputy Editor for npj Parkinson’s Disease but had no involvement in the editorial review or publication decision of this article. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, C., Zhang, Z., Wang, J. et al. Subthalamic stimulation shifts brain network dynamics from extensive functional support to motor dominance in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01184-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01184-9