Abstract

Nigrosome-1, a substructure in the dorsolateral substantia nigra, is characterized by the “swallow tail sign” (STS)—a dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity (DNH)—on susceptibility-weighted MRI in healthy individuals. Loss of the STS reflects degeneration of nigrosome-1 and serves as a recognized diagnostic marker for Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, its value in predicting disease severity and deep brain stimulation (DBS) outcomes remains unclear. We retrospectively analyzed 27 PD patients who underwent 3 T susceptibility map-weighted imaging (SMWI) derived from quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) prior to DBS. Nigrosome integrity was graded on a four-point scale, and patients were grouped as fully abnormal (Grade 4) or non-fully abnormal (Grades 1–3). No significant group differences were found in baseline motor severity or postoperative improvement, although the non-fully abnormal group showed lower absolute postoperative UPDRS III scores. Nigrosome grading showed no consistent association with symptom lateralization, including contralateral tremor severity or DBS responsiveness. These findings suggest that nigrosome integrity assessed by SMWI MRI—while a validated diagnostic biomarker for PD—showed no moderate-to-large effects with either disease severity or DBS outcomes. Although small effects cannot be excluded, their clinical relevance would be uncertain. Nigral imaging should be interpreted within a broader multimodal framework including clinical, imaging, and biochemical data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) remains one of the most prevalent and debilitating movement disorders, caused by progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc)1. Although deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or globus pallidus internus (GPi) is an established intervention, clinical outcomes remain highly variable. Approximately one quarter of patients experience suboptimal motor improvements (<30%)2,3,4,5 despite accurate electrode placement3,6,7. These disparities highlight the need for more refined patient selection strategies. Neuroimaging may offer objective biomarkers for predicting DBS outcomes8.

Current selection of candidates for DBS relies heavily on clinical assessments, including motor severity scales such as the Movement Disorder Society – Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), lengthy tests such as responsiveness to levodopa, and expert neurological evaluations9,10. However, symptom variability and subjective interpretation limit predictive accuracy11,12,13. While fluid-based biomarkers, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood-based assays, have been explored for PD diagnosis14,15,16, their utility in DBS selection is constrained by cost and invasiveness. In contrast, neuroimaging—already integrated into routine clinical care—offers a more practical, objective, and scalable solution to enhance patient stratification.

Recent advances in functional and metabolic imaging—such as 18F-fluorodopa po-sitron emission tomography (PET) and dopamine transporter (DaT) single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT)—have enhanced our understanding of disease burden and informed clinical decision-making17,18. However, few pre-operative imaging features have demonstrated consistent associations with postoperative outcomes following DBS.

Given that the degeneration of the SNpc is a pathological hallmark of PD, imaging techniques that enable direct visualization of nigral structures—particularly nigrosome-1—may offer valuable biomarkers for both disease progression and DBS outcome prediction19.

The swallow-tail sign (STS)20, a distinct dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity (DNH)21 observed on susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) in healthy individuals, histologically corresponds to nigrosome-122. Loss of this signal is a promising biomarker with high diagnostic accuracy for PD, reflecting underlying nigrosome-1 degeneration19. Cao et al. employed routine SWI, with STS disappearance detected in 67–77% of PD patients and interrater reliability κ = 0.82–0.86. Accuracy improved markedly when combined with neuromelanin-sensitive MRI and T2 mapping (AUC 0.958; sensitivity 97%)23. Blazejewska et al. showed consistent STS absence in all 10 PD patients at 7 T, albeit in a small cohort24. Schwarz et al. reported >90% accuracy at 3 T SWI (sensitivity 100%, specificity 95%, κ ≈ 0.82)25, confirming robustness at clinical field strength. Emerging imaging modalities, including susceptibility map-weighted imaging (SMWI/tSWI) derived from quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM), offer enhanced visualization of nigral substructures and may enable grading of nigrosome-1 integrity26,27.

Despite these diagnostic advances, the role of nigrosome-1 integrity in predicting DBS outcomes is unknown. Leveraging advanced imaging techniques for nigrosome visualization, this study aims to determine whether pre-operative nigrosome-1 integrity is associated with (1) baseline clinical features, including symptom severity and motor asymmetry, and (2) postoperative motor outcomes following DBS in PD patients. Identifying such associations could establish nigrosome-1 integrity as a critical biomarker, shifting the paradigm toward personalized neuromodulation strategies and optimized therapeutic outcomes in PD.

Results

As described in the Methods section, a total of 27 patients were included in the analysis: 9 in the non-fully abnormal group (6 males, 3 females) and 18 age- and sex- matched controls in the fully abnormal group (12 males, 6 females). Within the non-fully abnormal group, one female patient exhibited bilaterally normal nigrosomes, while three patients had symmetric grade 3 findings, classified as probably abnormal. The remaining five patients demonstrated asymmetric nigrosome abnormalities bilaterally (detailed side-specific nigrosome grading per patient is available in Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, all patients in the fully abnormal group showed bilaterally abnormal nigrosomes (Grade 4).

Preoperative nigrosome and baseline clinical features

The 9 patients in the non-fully abnormal group—including a surgical subgroup of 6 (5 STN-DBS, 1 GPi-DBS)—were compared to all 18 patients in the fully abnormal group (10 STN-DBS, 8 GPi-DBS), as detailed in Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics—including age, sex, disease duration, levodopa responsiveness, and other motor-related measures—did not differ significantly between the two groups (Fig. 1).

Violin plots depict the distributions of clinical characteristics and nigrosome-related measures between the Fully Abnormal (pink) and Non-fully Abnormal (blue) groups. Each violin includes individual data points, boxplots showing the median and interquartile range, and the overall distribution shape. The color gradient of the points indicates Nigrosome Grading (total score, range 2–8). UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, FOG freezing of gait, LEDD levodopa equivalent daily dose.

When laterality was taken into consideration based on the presence or partial preservation of nigrosome structure, side-specific motor severity—assessed by contralateral UPDRS and tremor scores—also showed no significant differences between the groups. These findings suggest no apparent relationship between preoperative nigrosome integrity and baseline motor symptom severity.

As a final step, we explored the relationship between baseline clinical characteristics and the full four-point nigrosome integrity scale (Grades 1 to 4) for each hemisphere, rather than using a binary classification. No consistent trends were observed to indicate that greater structural degeneration was associated with more severe contralateral motor symptoms (See also Supplementary Table 2 for details).

Effect size analyses across clinical, side-specific, and graded comparisons further demonstrated small estimates with wide confidence intervals frequently crossing zero, underscoring the limited precision of these findings in the context of the available sample size (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). After FDR correction, only the group difference in total nigrosome grading remained significant (q = 0.015). All other comparisons and correlations did not survive correction (all q > 0.05; Supplementary Table 3).

These findings suggest that nigrosome structural changes on preoperative imaging did not exhibit a moderate-to-large association with the severity of baseline motor impairment in this cohort. The possibility of small effects cannot be ruled out. The absence of consistent baseline nigral imaging findings motivated further investigation into whether nigrosome integrity might instead be predictive of postoperative motor outcomes.

Preoperative nigrosome and postoperative outcomes

The 6 patients in the non-fully abnormal group who underwent DBS (5 STN-DBS, 1 GPi-DBS) were compared to all 18 patients in the fully abnormal group (10 STN-DBS, 8 GPi-DBS), as detailed in Table 2. The distribution of DBS targets did not differ significantly between groups. Baseline clinical features—including age, sex, follow-up duration, and response to the levodopa challenge—were comparable across groups. At the optimal postoperative status, the non–fullly abnormal group demonstrated significantly lower total UPDRS III scores (W = 96.5, P = 0.005, Mann-Whitney U test) and gait scores (W = 94.5, P = 0.004, Mann-Whitney U test) compared to the fully abnormal group (Supplementary Table 4). However, no significant differences were observed in score differences (Δ = preoperative – postoperative) for either total UPDRS III (W = 43, P = 0.483) or gait (W = 33.5, P = 0.149), respectively. Other clinical parameters—including freezing of gait, speech, tremor severity, and LEDD reduction—also showed no significant group differences (all P > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test; Fig. 2).

Violin plots illustrate baseline characteristics and postoperative motor outcomes in the Fully Abnormal group versus the Non-fully Abnormal surgical subgroup. Each violin displays the distribution of individual values, with boxplots indicating the median and interquartile range. The color gradient of individual data points reflects Nigrosome Grading (total score, range 2–8). Δ values indicate preoperative–postoperative score differences, with positive values representing clinical improvement. DBS deep brain stimulation; STN subthalamic nucleus, GPi globus pallidus internus, UPDRS Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, FOG freezing of gait, LEDD levodopa equivalent daily dose.

When analyzed by hemisphere, both right- and left-sided Postoperative UPDRS scores were significantly lower in the non–fully abnormal surgical subgroup compared to the fully abnormal group (right: W = 92, p = 0.012; left: W = 88.5, p = 0.023; Mann–Whitney U test; Supplementary Table 5). Nevertheless, the relative improvement on each side remained statistically comparable between groups (right: W = 32.5, p = 0.161; left: W = 43.5, p = 0.503; Mann–Whitney U test). These findings suggest that the therapeutic benefit of DBS is not significantly influenced by the degree of preoperative nigrosome integrity.

In a more detailed analysis of laterality using the four-point nigrosome grading scale, a correlation was found between left-sided nigrosome grade and right-sided postoperative UPDRS scores (Spearman r = 0.50, 95% CI 0.12–0.77; p = 0.013); however, the explained variance was low (R² = 0.183), suggesting limited predictive value (Supplementary Table 6). Notably, this association did not hold when analyzing improvement scores difference (Δ), and the same was true for left-sided postoperative UPDRS and tremor scores, whether assessed by hemisphere or using overall nigrosome grades. These findings suggest that preoperative nigrosome integrity, as assessed by structural imaging, has limited utility in predicting side-specific postoperative motor outcomes.

Effect size analyses of postoperative improvement across group-wise, side-specific, and graded comparisons further demonstrated small estimates with wide confidence intervals frequently crossing zero, underscoring the limited precision of these findings and providing no consistent evidence that preoperative nigrosome grading predicts postoperative motor gains (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 3). After FDR correction, all comparisons and correlations did not survive correction (all q > 0.05; Supplementary Table 7).

Collectively, postoperative analyses indicated that preoperative nigrosome integrity—whether classified categorically or on a graded scale—did not demonstrate a moderate-to-large effect in predicting side-specific motor improvements or overall DBS benefit. Small effects cannot be excluded. While a weak hemispheric trend was noted, its negligible effect size and limited explanatory power highlight the minimal clinical utility of nigrosome grading as a predictive biomarker in this context.

Discussion

In this study, aside from a modest lateralized correlation between left nigrosome score and contralateral motor outcome, no significant associations were found between preoperative nigrosome integrity—as visualized using advanced 3 T MRI techniques—and baseline clinical features or postoperative motor outcomes. Our study was sufficiently powered to detect moderate-to-large effects. Any small associations would likely be of limited clinical utility relevant to DBS patient selection. These findings imply that, although nigrosome imaging has diagnostic utility, this marker alone may have limited prognostic value as a selection criterion for DBS surgery.

Notably, we identified 9 PD patients (out of 68) who exhibited non-fully abnormal nigrosomes yet were deemed suitable candidate for DBS surgery. This subgroup even included a patient with bilaterally normal nigrosomes who demonstrated a favorable response to DBS. Importantly, effect size analyses consistently yielded small estimates with wide confidence intervals frequently crossing zero, which argues against the presence of a large or clinically meaningful effect. Nevertheless, smaller associations cannot be definitively excluded, underscoring the need for larger cohorts to fully evaluate the predictive value of nigrosome grading.

Although Ultra-high-field 7 T MRI enhances visualization of fine-grained, iron-rich subcortical nuclei and achieves over 90% diagnostic accuracy for nigrosome-1 loss28,29,30, our 3 T findings align with emerging evidence that nigral degeneration correlates poorly with functional reserve in advanced PD31. From an imaging standpoint, while SWI can detect nigral hyperintensity, it lacks quantification capabilities, limiting its usefulness for monitoring Parkinsonism progression. In contrast, DaT imaging, such as 123I-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-N-(3-fluoropropyl)-nortropane (123I-FP-CIT) SPECT, provides quantifiable striatal uptake, enabling both diagnosis and longitudinal monitoring of disease progression. Recent advancements in deep learning have further enhanced the integration of SPECT and MRI to predict nigrostriatal dopaminergic degeneration. If nigral hyperintensity loss on MRI proves to correlate with declining DaT uptake, combining SWI and SPECT may allow MRI to function as a predictive biomarker for Parkinsonism32.

Another critical factor is the role of compensatory mechanisms, spanning from local synaptic plasticity to reorganization of the basal ganglia–thalamocortical circuit33,34. In some cases, preserved striatal dopamine terminals may sustain motor function through mechanisms like DaT downregulation or increased dopamine synthesis35,36. These adaptations may help explain the frequent mismatch between tracer uptake and motor symptom severity. Beyond subcortical processes, Johansson et al. recently demonstrated that clinical variability in PD is more closely linked to compensatory activity in the parieto-premotor cortex than to basal ganglia dysfunction. While striatal dopamine preservation may support basal ganglia plasticity, cortical compensation plays a central role in shaping clinical outcomes37. Taken together, this growing body of evidence supports the notion that nigral pathology alone is unlikely to be sufficient to reliably predict disease severity or therapeutic responsiveness in PD.

Similarly, the relationship between nigrosome asymmetry and clinical laterality remains uncertain. Several studies have established a strong association between nigrosome-1 abnormalities and clinical motor asymmetry in PD. Stezin et al. reported that poorly visualized nigrosome-1 correlated with greater contralateral motor asymmetry in 64.8% of cases38, while Noh et al. found high concordance between clinical asymmetry and contralateral nigrosome loss39. In contrast, our findings do not support a lateralizing effect of nigrosome-1 abnormalities, aligning more closely with the results of Kathuria et al., who demonstrated that nigrosome imaging with 3 T MRI and 18F-DOPA PET failed to consistently predict the predominant clinical side40. The lack of correlation may stem from heterogeneous compensatory responses across different disease stages, reinforcing the need for multimodal imaging approaches to improve prognostic accuracy in PD.

Among the non-fully abnormal nigrosome cohort, one particularly noteworthy case is that of a 69-year-old patient with an 11-year history of PD. Despite exhibiting completely normal nigrosome imaging, her diagnosis was confirmed through a comprehensive neurological assessment and clinical evaluation. At baseline, her OFF-medication UPDRS III score was 71, yet she demonstrated a 77% improvement in the levodopa challenge test. Consequently, she underwent bilateral GPi DBS implantation in consideration of her prominent axial symptoms, particularly impairments in balance and phonation. Postoperatively, her UPDRS III score improved to 20, reflecting a remarkable 72% improvement. Importantly, this case underscores the value of a multimodal biomarker approach, such as DaT imaging, to refine diagnostic accuracy and optimize patient stratification41. The absence of DaT-SPECT imaging in this patient is a key limitation, as it could have provided critical insight into the relationship between nigrosome integrity and presynaptic dopaminergic function. The observed discordance may reflect compensatory mechanisms or extranigral pathology, reinforcing the need for integrative imaging strategies in assessing DBS candidates.

Beyond DaT imaging, advanced modalities such as perfusion SPECT42, dopaminergic PET43,44, and diffusion-based microstructural MRI techniques45,46,47 offer complementary perspectives on disease biology. When integrated with connectomic analyses, these techniques enhance the precision of DBS targeting48. While each modality contributes unique strengths, converging evidence supports a multimodal strategy that synthesizes structural, functional, and network-level data as the most promising pathway toward personalized outcome prediction in PD neuromodulation.

Reviewing the application of the STS on SWI MRI, most studies report fair-to-high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing PD from healthy controls49, largely due to improved visualization of the nigrosome and reduced confounds from vascular and anatomical variants50. However, diagnostic performance remains inconsistent due to factors such as low field strength (e.g., 1.5 T)51, protocol heterogeneity52, disease duration53, and the need for experienced raters. Given these limitations, few studies have advanced to rigorously evaluate whether detailed STS grading correlates with disease severity or predicts DBS outcomes. Our findings address this gap, albeit with negative results, emphasizing the need for a more comprehensive imaging framework.

Several limitations warrant consideration. The absence of DaT imaging in this cohort limited opportunities for direct comparison with dopaminergic imaging, which could have provided complementary validation. At the same time, reliance on visual nigrosome grading may still entail a degree of reader bias, highlighting the value of future quantitative or automated approaches. Our cohort encompassed both STN and GPi targets and included a spectrum of clinical presentations, reflecting a typical phenotypic diversity inherent to Parkinson’s disease when selecting DBS patients. This reflects real-world clinical diversity and thus enhances the external validity of our observations. However, detailed characterization of tremor predominance, motor fluctuations, and dyskinesias was not systematically available. As such, potential influences of these features on DBS target selection and postoperative outcomes could not be assessed, which should be addressed in future studies. More fundamentally, the retrospective design and relatively small number of patients without fully abnormal nigrosomes increase the risk of Type II errors, particularly in subgroup analyses (e.g., lateralized outcomes). Although small effects cannot be excluded, such effects are typically difficult to translate into meaningful clinical uses. The 2:1 controls/cases matching approach is consistent with common methodological practice, but instead of using the entire available control group, this may have reduced statistical power, potentially obscuring subtle effects. Independent replication in larger, prospectively acquired datasets will be critical to corroborate and generalize these preliminary findings. Additionally, the ≤2-year follow-up period limits the evaluation of long-term DBS outcomes, where disease progression and neuroadaptive plasticity may further influence the relationship between baseline nigrosome integrity and treatment response.

While nigrosome-1 integrity assessed via 3 T SMWI MRI remains diagnostically informative for PD, no moderate-to-large associations were observed with baseline clinical features or postoperative DBS outcomes in this small and heterogeneous cohort. Although small effects cannot be excluded, such effects are generally difficult to translate into meaningful clinical benefits. These findings suggest that nigral imaging may have limited predictive value as a standalone biomarker and should instead be interpreted within the context of broader clinical and imaging measures. Future efforts should focus on validating these observations in larger, prospective cohorts and integrating nigrosome assessment into multimodal biomarker frameworks to support individualized DBS planning.

Methods

DBS patient population

Upon approval by the University Health Network (UHN) Research Ethics Board (REB #24-5181.0), we retrospectively identified 70 consecutive patients with suspected PD who were deemed eligible for DBS surgery and underwent pre-operative 3.0 T MRI for DBS planning using a standardized movement disorders protocol at UHN between February 2022 and February 2024. Given its retrospective design and use of de-identified clinical data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Of the initial cohort, two patients were subsequently diagnosed with essential tremor and excluded, yielding a final cohort of 68 patients with confirmed PD. Eligible participants were adults (≥18 years) with comprehensive clinical documentation and longitudinal follow-up. Clinical data collected included age, sex, disease duration, levodopa responsiveness, motor severity, and daily dopaminergic medication burden. Motor severity was assessed using the MDS-UPDRS Part III, and daily dopaminergic medication burden was quantified as levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD), calculated using standardized conversion formulas54. DBS eligibility assessment and surgical procedures were performed according to our previously published institutional protocol55. Target selection (STN vs GPi) followed established criteria as described in Dallapiazza et al.56. Postoperative motor severity was evaluated at each patient’s optimal clinical state, defined as the time point of best motor response occurring between 3 and 12 months following surgery. To assess symptom laterality, total appendicular MDS-UPDRS and tremor subscores from the side contralateral to DBS implantation were analyzed.

MRI acquisition and nigrosome identification

MRI was performed using a 3 T Siemens Vida scanner following a standardized movement disorders protocol. Nigrosome-1 imaging was acquired using an axial 3D multi-echo spoiled gradient echo sequence with 0.5 × 0.5 mm in-plane resolution and 1 mm slice thickness (voxel size 0.5 × 0.5 × 1 mm; 36 slices per slab). Imaging parameters included TR = 48.0 ms, TE = 39.00 ms, flip angle = 20°, and GRAPPA (acceleration factor = 2), with a 5:18 min acquisition time. Post-processing was conducted using STI Suite in MATLAB (R2019a) and SmWI Tools v0.9257, which enhances contrast based on magnetic susceptibility differences. Processing included root sum of squares image generation, Laplacian phase unwrapping, harmonic background phase removal (HARPERELLA), and QSM reconstruction, ultimately producing the susceptibility map-weighted image58,59.

All MRI scans were independently reviewed by a board-certified neuroradiologist, a neuroradiology fellow, and a radiology resident, all blinded to clinical data. Interrater reliability was calculated between two readers, with discrepancies adjudicated by a senior neuroradiologist with over 13 years of experience. In our own cohort of 248 patients including 133 with PD, absence of nigral hyperintensity on SMWI had sensitivity of 92.0%, specificity of 95.8%, accuracy of 93.1%, and interrater reliability of κ = 0.88 (unpublished, manuscript submitted).

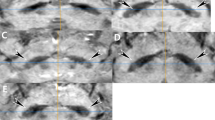

The STS was assessed using a four-point scale derived from the original five-point ordinal scale proposed by Shams et al., where Grade 0 = unsure, 1 = definitely normal, 2 = probably normal, 3 = probably abnormal, and 4 = definitely abnormal60 (Fig. 3). In this modified version, only Grades 1 to 4 were used, with Grade 0 excluded from analysis to ensure consistency in applying a four-point scale throughout the study. Patients were subsequently categorized as fully abnormal (Grade = 4) or non-fully abnormal (Grades = 1-3). Although prior studies have consistently shown nigrosome abnormalities in PD—both on susceptibility-based imaging with SMWI61 and on 7 T neuromelanin imaging with near-perfect diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity 95–100%, specificity 96–100%)62—we unexpectedly observed that nine patients in our DBS cohort exhibited non–fullly abnormal nigrosome findings. To investigate these subgroups, we identified an age- and sex- matched control group (n = 18) from the fully abnormal cohort. We first evaluated the relationship between preoperative nigrosome integrity and baseline motor function, followed by an analysis of its association with postoperative outcomes. For the latter analysis, three patients from the non–fully abnormal group were excluded due to either not undergoing surgery or lacking postoperative MDS-UPDRS III data (Fig. 4).

Visual representation of the patient selection process for this study. A total of 70 patients with suspected PD underwent SMWI; 68 were confirmed with PD. Of these, 9 had non-fully abnormal nigrosome signals, while 59 showed fully abnormal grading. After matching, 18 patients were selected from the 59 with fully abnormal nigrosome grading to serve as the control group. These were compared to the 9 patients with non-fully abnormal signals, and postoperative outcomes were further analyzed in the surgical subgroup of 6 patients. DBS deep brain stimulation, SMWI susceptibility map-weighted imaging, PD Parkinson’s disease.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data are reported as counts and percentages. For continuous data, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality. Non-normally distributed variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Descriptive statistics were reported as means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and counts with corresponding percentages for categorical variables. We analyzed the relationship between nigrosome grading and contralateral baseline, as well as postoperative UPDRS scores, primarily focusing on score differences (Δ), calculated as: preoperative – postoperative values. In this context, positive Δ values indicate clinical improvement. Effect sizes (Hedges’ g with 95% CIs) were calculated for group-wise and side-specific comparisons at baseline and postoperatively. Associations were assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r) with 95% CIs derived from Fisher’s z transformation. Statistical analysis was conducted using R (version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with a two-tailed significance threshold set at p < 0.05. P-values were also adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) method.

Data availability

Due to privacy and ethical restrictions, the datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with appropriate institutional approvals.

References

Tanner, C. M. & Ostrem, J. L. Parkinson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med 391, 442–452 (2024).

Krack, P. et al. Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med 349, 1925–1934 (2003).

Schuepbach, W. M. et al. Neurostimulation for Parkinson’s disease with early motor complications. N. Engl. J. Med 368, 610–622 (2013).

Bratsos, S., Karponis, D. & Saleh, S. N. Efficacy and Safety of Deep Brain Stimulation in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus 10, e3474 (2018).

Pauls, K. A. M. et al. Causes of failure of pallidal deep brain stimulation in cases with pre-operative diagnosis of isolated dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 43, 38–48 (2017).

Weaver, F. M. et al. Randomized trial of deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: thirty-six-month outcomes. Neurology 79, 55–65 (2012).

Habets, J. G. V. et al. Multicenter Validation of Individual Preoperative Motor Outcome Prediction for Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 100, 121–129 (2022).

Peng, S., Dhawan, V., Eidelberg, D. & Ma, Y. Neuroimaging evaluation of deep brain stimulation in the treatment of representative neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Bioelectron. Med. 7, 4 (2021).

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

Heinzel, S. et al. Update of the MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 34, 1464–1470 (2019).

Angelini, L., Paparella, G. & Bologna, M. Distinguishing essential tremor from Parkinson’s disease: clinical and experimental tools. Expert Rev. Neurother. 24, 799–814 (2024).

Borghammer, P., Okkels, N. & Weintraub, D. Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies: One and the Same. J. Parkinsons Dis. 14, 383–397 (2024).

Shin, H. W., Hong, S. W. & Youn, Y. C. Clinical Aspects of the Differential Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease and Parkinsonism. J. Clin. Neurol. 18, 259–270 (2022).

Hall, S. et al. CSF biomarkers and clinical progression of Parkinson disease. Neurology 84, 57–63 (2015).

Bridel, C. et al. Diagnostic Value of Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Protein in Neurology: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 76, 1035–1048 (2019).

Parnetti, L. et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 18, 573–586 (2019).

Bega, D. et al. Clinical utility of DaTscan in patients with suspected Parkinsonian syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 7, 43 (2021).

Hsiao, I. T. et al. Correlation of Parkinson disease severity and 18F-DTBZ positron emission tomography. JAMA Neurol. 71, 758–766 (2014).

Damier, P., Hirsch, E. C., Agid, Y. & Graybiel, A. M. The substantia nigra of the human brain. I. Nigrosomes and the nigral matrix, a compartmental organization based on calbindin D(28K) immunohistochemistry. Brain 122, 1421–1436 (1999).

Chau, M. T., Todd, G., Wilcox, R., Agzarian, M. & Bezak, E. Diagnostic accuracy of the appearance of Nigrosome-1 on magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 78, 12–20 (2020).

Reiter, E. et al. Dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity on 3.0T susceptibility-weighted imaging in neurodegenerative Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 30, 1068–1076 (2015).

Haller, S., Haacke, E. M., Thurnher, M. M. & Barkhof, F. Susceptibility-weighted Imaging: Technical Essentials and Clinical Neurologic Applications. Radiology 299, 3–26 (2021).

Cao, Q. et al. Diagnostic value of combined magnetic resonance imaging techniques in the evaluation of Parkinson disease. Quant. Imaging Med Surg. 13, 6503–6516 (2023).

Blazejewska, A. I. et al. Visualization of nigrosome 1 and its loss in PD: pathoanatomical correlation and in vivo 7 T MRI. Neurology 81, 534–540 (2013).

Schwarz, S. T. et al. The ‘swallow tail’ appearance of the healthy nigrosome - a new accurate test of Parkinson’s disease: a case-control and retrospective cross-sectional MRI study at 3T. PLoS One 9, e93814 (2014).

Liu, S. et al. Improved MR venography using quantitative susceptibility-weighted imaging. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 40, 698–708 (2014).

He, N., Chen, Y., LeWitt, P. A., Yan, F. & Haacke, E. M. Application of Neuromelanin MR Imaging in Parkinson Disease. J. Magn. Reson Imaging 57, 337–352 (2023).

Middlebrooks, E. H. et al. Enhancing outcomes in deep brain stimulation: a comparative study of direct targeting using 7T versus 3T MRI. J. Neurosurg. 141, 252–259 (2024).

van Laar, P. J. et al. Surgical Accuracy of 3-Tesla Versus 7-Tesla Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson Disease. World Neurosurg. 93, 410–412 (2016).

Gupta, R. et al. The Swallow Tail Sign of Substantia Nigra: A Case-Control Study to Establish Its Role in Diagnosis of Parkinson Disease on 3T MRI. J. Neurosci. Rural Pr. 13, 181–185 (2022).

Chen, M. et al. Free water and iron content in the substantia nigra at different stages of Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Radio. 167, 111030 (2023).

Bae, Y. J. et al. Deep learning regressor model based on nigrosome MRI in Parkinson syndrome effectively predicts striatal dopamine transporter-SPECT uptake. Neuroradiology 65, 1101–1109 (2023).

Palmer, S. J., Li, J., Wang, Z. J. & McKeown, M. J. Joint amplitude and connectivity compensatory mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 166, 1110–1118 (2010).

Blesa, J. et al. Compensatory mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease: Circuits adaptations and role in disease modification. Exp. Neurol. 298, 148–161 (2017).

Ribeiro, M. J. et al. Dopaminergic function and dopamine transporter binding assessed with positron emission tomography in Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 59, 580–586 (2002).

Thobois, S., Prange, S., Scheiber, C. & Broussolle, E. What a neurologist should know about PET and SPECT functional imaging for Parkinsonism: A practical perspective. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 59, 93–100 (2019).

Johansson, M. E., Toni, I., Kessels, R. P. C., Bloem, B. R. & Helmich, R. C. Clinical severity in Parkinson’s disease is determined by decline in cortical compensation. Brain 147, 871–886 (2023).

Stezin, A. et al. Clinical utility of visualisation of nigrosome-1 in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Eur. Radio. 28, 718–726 (2018).

Noh, Y., Sung, Y. H., Lee, J. & Kim, E. Y. Nigrosome 1 Detection at 3T MRI for the Diagnosis of Early-Stage Idiopathic Parkinson Disease: Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy and Agreement on Imaging Asymmetry and Clinical Laterality. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 2010–2016 (2015).

Kathuria, H. et al. Utility of Imaging of Nigrosome-1 on 3T MRI and Its Comparison with 18F-DOPA PET in the Diagnosis of Idiopathic Parkinson Disease and Atypical Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 8, 224–230 (2021).

Haller, S., Davidsson, A., Tisell, A., Ochoa-Figueroa, M. & Georgiopoulos, C. MRI of nigrosome-1: A potential triage tool for patients with suspected parkinsonism. J. Neuroimaging 32, 273–278 (2022).

Hayashi, Y. et al. Unilateral GPi-DBS Improves Ipsilateral and Axial Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease as Evidenced by a Brain Perfusion Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography Study. Front Hum. Neurosci. 16, 888701 (2022).

Riahi, F. & Fesharaki, S. The role of nuclear medicine in neurodegenerative diseases: a narrative review. Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 14, 34–41 (2025).

Burkett, B. J., Johnson, D. R. & Lowe, V. J. Evaluation of Neurodegenerative Disorders with Amyloid-β, Tau, and Dopaminergic PET Imaging: Interpretation Pitfalls. J. Nucl. Med 65, 829–837 (2024).

Loehrer, P. A. et al. Microstructure predicts non-motor outcomes following deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 104 (2024).

Hermann, M. G. et al. The connection of motor improvement after deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease and microstructural integrity of the substantia nigra and subthalamic nucleus. Neuroimage Clin. 42, 103607 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Predicting Motor Outcome of Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease Using Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping and Radiomics: A Pilot Study. Front. Neurosci. 15, 731109–731109 (2021).

Frey, J. et al. Past, Present, and Future of Deep Brain Stimulation: Hardware, Software, Imaging, Physiology and Novel Approaches. Front Neurol. 13, 825178 (2022).

Tseriotis, V. S. et al. Is the Swallow Tail Sign a Useful Imaging Biomarker in Clinical Neurology? A Systematic Review. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.14304 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Swallow tail sign on susceptibility map-weighted imaging (SMWI) for disease diagnosing and severity evaluating in parkinsonism. Acta Radio. 62, 234–242 (2021).

Grossauer, A. et al. Dorsolateral Nigral Hyperintensity on 1.5 T Versus 3 T Susceptibility-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Neurodegenerative Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 10, 914–921 (2023).

Prasuhn, J. et al. Clinical MR imaging in Parkinson’s disease: How useful is the swallow tail sign?. Brain Behav. 11, e02202 (2021).

McKinley, J., O’Connell, M., Farrell, M. & Lynch, T. Normal dopamine transporter imaging does not exclude multiple system atrophy. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20, 933–934 (2014).

Tomlinson, C. L. et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 25, 2649–2653 (2010).

Lozano, C. S. et al. Imaging alone versus microelectrode recording-guided targeting of the STN in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosurg. 130, 1847–1852 (2019).

Dallapiazza, R. F. et al. in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects (eds T. B. Stoker & J. C. Greenland) (Codon PublicationsCopyright: The Authors, 2018).

Nam, Y., Gho, S. M., Kim, D. H., Kim, E. Y. & Lee, J. Imaging of nigrosome 1 in substantia nigra at 3T using multiecho susceptibility map-weighted imaging (SMWI). J. Magn. Reson Imaging 46, 528–536 (2017).

Li, W., Avram, A. V., Wu, B., Xiao, X. & Liu, C. Integrated Laplacian-based phase unwrapping and background phase removal for quantitative susceptibility mapping. NMR Biomed. 27, 219–227 (2014).

Li, W. et al. A method for estimating and removing streaking artifacts in quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage 108, 111–122 (2015).

Shams, S. et al. MRI of the Swallow Tail Sign: A Useful Marker in the Diagnosis of Lewy Body Dementia?. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 38, 1737–1741 (2017).

Jin, L. et al. Combined Visualization of Nigrosome-1 and Neuromelanin in the Substantia Nigra Using 3T MRI for the Differential Diagnosis of Essential Tremor and de novo Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurol. 10, 100 (2019).

Lakhani, D. A. et al. Diagnostic utility of 7T neuromelanin imaging of the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinson’s Dis. 10, 13 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors received no specific funding for this work. We are deeply grateful to our colleagues at Toronto Western Hospital and Mackay Memorial Hospital for their guidance and support throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.K.H.: study conceptualization, data analysis, manuscript drafting, figure preparation (Figures 1, 2, and 4). W.B.M. and F.S.: clinical data collection and organization. Y.B. and J.G.: statistical validation, data analysis, data interpretation, manuscript revision. T.A.R.: manuscript review and editing. S.K.K.: DBS surgeries and perioperative patient care. A.F.: patient evaluation, clinical management, stimulation, and medication adjustments. P.A.L.: imaging interpretation, figure preparation (Figure 3). A.B.: study design, critical manuscript revision, co-corresponding author. A.M.L.: project supervision, critical manuscript revision, co-corresponding author. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, CK., B. Mohammed, W., Bai, Y. et al. Limited predictive value of preoperative nigrosome integrity for motor outcomes in Parkinson’s disease deep brain stimulation. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 343 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01191-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01191-w