Abstract

We investigated the genetic landscape of Parkinson’s disease (PD) on the island of Crete. DNA samples from 360 PD patients and 251 controls were analyzed using a combination of genotyping, whole-exome sequencing, and targeted screening for GBA1 variants p.N409S and p.L483P. A molecular diagnosis (heterozygous dominant/homozygous recessive pathogenic/likely pathogenic non-GBA1 variant) was identified in 3.1% of patients, including LRRK2-PD (n = 4) and SNCA-PD (n = 1). A novel homozygous PINK1 variant (p.Y295Ter) and a rare homozygous FIG4 variant (p.I41T) were detected in two early-onset cases. About 10.3% of patients carried a GBA1 variant, including four rare variants (p.C55S, p.H294Q, p.K237T, p.R502H), and had an adjusted earlier disease onset of 7.3 years. GBA1 carriers had a 4.3-fold higher risk for PD compared to non-carriers. The proportion of GBA1 in Crete highlights the distinct genetic PD profile in this population and supports targeted genetic testing and counseling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic factors play a crucial role in the pathogenesis and phenotypic variations of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Rare, highly penetrant variants represent one end of the genetic spectrum and are considered high-risk, or even causal, for the development of PD1. Such single-gene mutations, often flagged through family studies or atypical case reports, underlie the ‘monogenic’ forms of PD. These cases align more closely with Mendelian inheritance patterns and account for 5–10% of all PD cases2,3. Conversely, although more common low-penetrance variants contribute only mildly to individual lifetime risk, their cumulative effect may significantly influence the development of sporadic PD, particularly in early-onset cases1,4. These variants are primarily detected by Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS).

Identifying disease-associated variants is valuable for preclinical mechanistic studies that employ cellular (in vitro) or transgenic animal (in vivo) models to mimic the disease5, thereby deepening our understanding of underlying pathogenetic mechanisms. Early-stage and pre-clinical PD patients or asymptomatic carriers of pathogenic variants constitute the ideal subpopulation for gene-targeting therapy trials. The suboptimal results of such initiatives, including ongoing trials on GBA1- or LRRK2-PD6,7, have been largely attributed to low enrollment of genetically characterized PD patients8. The frequency of certain variants in these two genes often exceeds the 1% threshold used to flag rare variants with particularly high percentages found in groups of distinct genetic heritage (e.g., Ashkenazi Jewish, North African Arab-Berber)9. Genetic heterogeneity of PD has been repeatedly documented with large-scale studies stressing the need for underrepresented ethnic/geographical groups to be included10. Consequently, while the clinical impact of certain variants has been consistently demonstrated in large-scale meta-analyses (LRRK2: p.G2019S, p.R1441H, p.L1795F; GBA1: p.N409S, p.T408M, p.E365K, p.R502C, p.R296Q, p.D179H; PRKN: p.R275W)3, the pertinence of others remains controversial due to lack of replication studies, often attributed to their low frequency.

Geographically isolated populations, even with relatively small sample sizes, are essential for studying the genetic basis of complex diseases like PD. Their relative genetic homogeneity, often shaped by founder effects and shared environmental influences, makes them particularly informative for detecting recessively inherited factors11. The island of Crete, located at the juncture of the Aegean and the Libyan Sea, is the fifth-largest island in the Mediterranean basin and the largest in Greece, with a population of approximately 620,00012. Due to the small size and mountainous terrain, the Cretan population presents characteristics of a ‘closed population’13,14. Cretan inhabitants retain strong family ties and share a common environmental, cultural, and religious background, with nearly half of the population residing in rural areas, some of which are poorly accessible12,15,16. Although the strategic location of the island at the crossroads of three continents has historically attracted numerous conquerors, including Arabs and Venetians, modern analyses have shown stronger genetic links with the Central, Northern and Eastern Europeans, Anatolia, North Africa, and ancient Minoan populations15,17,18,19.

Crete has historically and geopolitically been distinct from mainland Greece, with reports of ancestral discrepancies raising questions about the degree of genetic affinity between modern Cretan and mainland Greek populations18,20. Previous studies have revealed a high prevalence of familial PD in Crete21. Clustering of familial PD patients in small geographical areas of the island led to bilineal inheritance of the disease in several families, with segregation analysis suggesting an oligogenic inheritance pattern13. On the other hand, mutations in LRRK2, but not in SNCA, were identified in the Cretan population, while the opposite has been reported for familial PD in the Greek mainland21,22.

In this study, we aimed to determine the spectrum of potentially pathogenic variants located in 29 Parkinsonism-related genes in a cohort of PD patients and controls residing in Crete using a combination of screening methods. Additionally, we explored associations between these variants and age at disease onset/diagnosis (AAO) or family history.

Results

Participants and variants overview

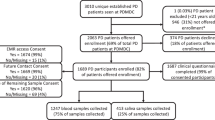

DNA samples from 360 index patients and 251 controls were included (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). Patients and controls were matched for sex and age at enrollment (Table 1). A minority of patients (n = 11, 3.1%), though permanent residents of Crete, were of non-Greek ethnicity. About one-sixth of PD patients were deceased at the time of data analysis, with an average disease duration of 15 years. These patients were significantly older than the surviving patients at the time of enrollment (72.7 vs 68.4 years, p-value < 0.0001).

Genotyping data were obtained for all patients and controls. PCR-RFLP (polymerase chain reaction-mediated approach of restriction fragment length polymorphisms) results for GBA1 variants p.N409S and p.L483P were available for all patients, and whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed in 43 patients with strong suspicion of genetic etiology (based on positive family history or early-onset disease). Ultimately, 32 pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) variants and 75 variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were detected across 26 Parkinsonism genes (Fig. 2, Supplementary Tables S1, S2). The GBA1 variant p.L483P was identified exclusively through PCR-RFLP, having been excluded during the genotyping quality control (QC) process. The GBA1 variant p.N409S passed the predefined QC thresholds; results from both genotyping and PCR-RFLP assays were considered. No discrepancies were observed between results obtained from different genetic methods applied to the same samples.

a Variant distribution in high-confidence genes in the patient cohort using all screening methods (red color represents pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in patients, blue color represents VUS in patients); b variant distribution in high-confidence genes in both patients and controls detected solely via genotyping (yellow color represents pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in controls, and dark green represent VUS in controls); c variant distribution in low-confidence genes in the patient cohort using all screening methods; d variant distribution in low-confidence genes in both patients and controls detected solely via genotyping. The differences in total variant counts and the genes identified between panels reflect the smaller number of variants genotyped in both patients and controls. Controls were genotyped exclusively by GP2. Although both laboratories (NINDS and GP2) employed the same genotyping array, some variants were genotyped only by one laboratory, likely due to differences in quality control settings.

Pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants and clinical associations

A P/LP variant was detected in a Parkinsonism-related gene in 15% of patients. The P/LP variants detected in high-confidence genes led to a molecular diagnosis in 5.9% of patients, including 15 heterozygous carriers of well-established P/LP GBA1 variants (p.L483P [n = 11]; p.N409S [n = 2]; p.D448H [n = 1]; p.H294Q [n = 2]), four heterozygous carriers of LRRK2 variants (p.G2019S [n = 3]; p.R1441H [n = 1]), one heterozygous carrier of the p.A53T variant in SNCA, and one homozygous carrier of a PINK1 variant (p.Y295Ter) (Fig. 3, Table 2).

a Molecular diagnostic yield stratified by variant pathogenicity (colors in the pie chart are listed in clockwise order. Dark red: heterozygous carriers of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in high-confidence genes inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; black: homozygous carriers of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in high-confidence genes inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern; green: heterozygous carriers of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in low-confidence genes inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; red: homozygous carriers of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in low-confidence genes inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern; blue: heterozygous carriers of VUS in high-confidence genes inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; pink: heterozygous carriers of VUS in low-confidence genes inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern); b molecular diagnostic yield stratified by specific PD-related genes (colors in the pie chart are listed in clockwise order. Dark green: pathogenic/likely pathogenic GBA1 variants; light green: GBA1 VUS; red: pathogenic/likely pathogenic LRRK2 variants; yellow: pathogenic/likely pathogenic SNCA variants; black: homozygous pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in autosomal recessive genes).

The phenotype of the above cases resembled commonly reported manifestations of GBA1-PD, LRRK2-PD, and SNCA-PD, respectively. The homozygous case (P#221) involved a novel, stop-gain variant in PINK1 (PINK1:NM_032409:exon4:c.885C>A:p.Y295Ter) in a patient with early-onset, akinetic PD (AAO 34). He initially presented with gait impairment, markedly asymmetrical Parkinsonism, dystonic posture of the lower limb, and an abnormal result in dopamine transporter imaging (DaTscan). Motor symptoms were relatively mild with a slowly progressive course and excellent dopaminergic response. Approximately a decade after diagnosis, he started experiencing mild motor fluctuations and choreiform/dystonic dyskinesias on the most affected side without any balance problems 12 years post-diagnosis. His non-motor profile included depression, mild dysautonomia, and sleep disturbances. A prominent feature was the early onset of severe impulse control disorder (ICD), precipitated by dopaminergic agonists, which significantly interfered with treatment adherence and exerted a negative impact on his quality of life over the ensuing years.

The molecular diagnostic yield increased to 7.3% when all P/LP variants were considered, introducing though the uncertainty of low-confidence genes (Fig. 3). Among the additional cases was a patient with sporadic early-onset PD (EOPD) (AAO 42) (P#081), who was homozygous for the p.I41T variant in FIG4 (FIG4:NM_014845:exon2:c.T122C:p.I41T)23. She exhibited a strikingly asymmetrical Parkinsonian syndrome, corroborated by an abnormal DaTscan, along with coexisting Parkinsonian tremor, pyramidal signs, and unilateral dystonic posture of the lower limb. Despite a suboptimal response to dopaminergic therapy, her disease followed a relatively benign and slowly progressive course with peak-dose dystonic dyskinesia five years after diagnosis. She remains functionally independent and cognitively intact 14 years post-diagnosis.

The remaining four cases were all carriers of dominantly inherited GCH1 variants, including one homozygous case of p.T94M (GCH1:NM_000161:exon1:c.C281T:p.T94M) (P#212), one heterozygous case of the start-loss variant p.M1? (GCH1:NM_000161:exon1:c.A1T:p.M1?) (P#304), and two double heterozygous cases of p.T94M and either the dominant variant p.M1? (GCH1:NM_000161:exon1:c.A1G:p.M1?) (P#336) or the recessive variant p.C18Ter (GCH1:NM_000161:exon1:c.C54A:p.C18Ter) (P#278). All of them had typical PD with an excellent levodopa response, albeit with heterozygous presentations. P#104, who carried the heterozygous GCH1 variant p.T94M, was also heterozygous for the GBA1 variant p.L483P, and demonstrated an excellent levodopa response. None of the above GCH1 variants were genotyped in the control group.

Variants of uncertain significance and clinical associations

A VUS was detected in a known Parkinsonism-related gene in 25.3% of patients. The presence of VUS in high-confidence genes further increased molecular diagnostic yield by 6.9% (n = 25), with nearly 90% of these cases involving GBA1 variants (21 heterozygous, one homozygous) (Fig. 3). The variant p.C55S (GBA1:NM_001005741:exon4:c.G164C:p.C55S), identified in a patient with mixed-type familial PD (AAO 60), was not genotyped in the control group. Four GBA1 VUS were more common in patients than controls with p.T408M (GBA1:NM_000157:exon8:c.C1223T:p.T408M) being the most frequently encountered variant in our cohort. The majority of p.T408M carriers had a positive family history (63.6%), a typical presentation with mixed- or tremor-dominant PD, an excellent response to levodopa, and a relatively benign disease course without early cognitive impairment. A homozygous case (P#407) of p.T408M was diagnosed with tremor-dominant PD (AAO 54), early impairment of postural reflexes, pain, and thought rigidity, though without cognitive deficits. She had an extensive bilineal family history of PD, tremor and dementia.

Eight patients were heterozygous for the variant p.Ε365Κ (GBA1:NM_000157:exon8:c.G1093A:p.E365K). One-quarter of them had a third-degree relative affected by PD, another 25% reported a family history of undiagnosed tremor, and half were diagnosed with sporadic EOPD. Most patients had a benign, tremor-dominant or mixed phenotype with occasional symptoms of anxiety, depression, or mild ICD. The rare heterozygous variant p.K237T (GBA1:NM_000157:exon6:c.A710C:p.K237T) was found in a patient (P#288) with akinetic sporadic EOPD (AAO 47.6) and a rather malignant disease course, including an early emergence of complications, such as severe motor fluctuations, troublesome dystonic dyskinesia, and cognitive impairment four years post-diagnosis. A similar motor and neuropsychiatric profile, though without early cognitive impairment, was noted in P#208, who was heterozygous for the rare variant p.R502H (GBA1:NM_000157:exon10:c.G1505A:p.R502H) and was diagnosed with akinetic sporadic late-onset PD (LOPD) (AAO 51).

Regarding non-GBA1 VUS in high-confidence genes, one patient (P#408) was heterozygous for the p.A737V variant in VPS35 (VPS35:NM_018206:exon16:c.C2210T:p.A737V). Her clinical presentation and family history did not suggest a genetic etiology, while another heterozygous carrier was detected in the control group. Additionally, the LRRK2 variant p.L119P (LRRK2:NM_198578:exon4:c.T356C:p.L119P), found in two heterozygous patients (P#064, P#343), was more than three times as frequent in controls. The above findings suggest either incomplete penetrance or a likely benign effect of these variants, at least in our population3.

Variant segregation in blood-related individuals

We genotyped 37 blood-related patients, of whom only one per family was retained as an index case for the analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2). Among them, 28 patients were grouped into second-degree relative pairs and the remaining nine were related up to the third degree according to kinship analysis. A shared PD-related genetic substrate was confirmed only in six patients, including two sibling pairs sharing the GBA1 p.N409S variant and the LRRK2 p.G2019S variant, respectively, and a pair of aunt–nephew both carrying the GBA1 p.L483P variant. In another sibling pair, both patients were heterozygous for a likely pathogenic PINK1 variant, although one of them also carried the GBA1 variant p.L483P. Additionally, a sibling pair shared a heterozygous pathogenic PRKN variant. No clear genetic cause could be identified in either member of the remaining cases, even after WES.

Variant burden and molecular diagnostic yield among patient subgroups

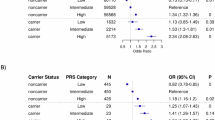

In high-confidence genes, familial PD patients carried a significantly higher burden of P/LP variants than sporadic LOPD (Table 3, Fig. 4). In contrast, patients with apparently sporadic EOPD exhibited a significantly higher burden of VUS compared to sporadic LOPD. The higher frequency of GBA1 variants in this group may have contributed to this association. These findings were also supported by multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusted for sex, ethnicity, and disease duration (Supplementary Tables S3a-c). Familial PD patients were 2.4 times more likely than sporadic LOPD to have a molecular diagnosis due to P/LP variants in high-confidence genes, although this association was only marginally significant (OR = 2.39, 95% CI: 0.93–6.22, p = 0.068). When VUS in high-confidence genes were considered, sporadic EOPD patients were 3.4 more likely than sporadic LOPD to have genetic PD (OR = 3.37, 95% CI: 1.14–9.47, p = 0.022). Moreover, sporadic EOPD patients were almost three times more likely to carry a GBA1 variant (OR = 2.97, 95% CI: 1.15–7.32, p = 0.02).

a Stratification based on pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants (red dots) vs. VUS (blue dots); b stratification based on variants in high-confidence genes (yellow dots) vs. low-confidence genes (blue dots). The overall variant burden of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants or VUS did not differ significantly between groups when both high- and low-level confidence genes were considered. However, variants in high-confidence genes (both pathogenic/likely pathogenic and VUS) were significantly enriched in familial PD patients (adjusted p = 0.014) and in sporadic EOPD patients (adjusted p = 0.032), each compared with sporadic LOPD (p-values from Kruskal-Wallis test).

Age at disease onset and clinical associations

AAO differed significantly among the three subgroups (sporadic EOPD < familial PD < sporadic LOPD) (Table 3). In multiple linear regression analysis, the presence of GBA1 variants was associated with an earlier AAO by 7.3 years (95% CI: -10.8 to -3.8, p < 0.0001). When GBA1 variants were analyzed separately, P/LP were associated with an earlier AAO by 6.5 years (95% CI: -11.8 to -1.3, p = 0.015) and VUS by 7.8 years (95% CI: -12.3 to -3.4, p < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 5). These associations persisted after adjusting for other variant categories, none of which significantly affected AAO (Supplementary tables S4a-c). Non-Greek ethnicity and shorter disease duration at enrollment were also linked to diagnosis at a younger age. These findings may, at least partly, reflect methodological particularities, as early-onset patients and non-Greek participants may be more likely to seek care at a tertiary movement disorders center, or be informed about research opportunities and participate in research sooner after diagnosis.

Variant burden analysis among patients and controls

PD patients carried significantly more variants compared to controls (Table 4). This difference became more pronounced when restricting the analysis to high-confidence genes, underscoring their contribution to PD pathogenesis, and suggesting greater heterogeneity within the group of low-confidence genes (Fig. 6). This trend was most likely mediated by the effect of GBA1 variants, while the burden of autosomal recessive variants did not differ significantly between patients and controls. The presence of a GBA1 variant, whether classified as P/LP or VUS, was strongly linked to PD, with carriers having nearly 4.3 times the odds of a PD diagnosis compared to non-carriers (OR = 4.29, 95% CI: 1.61 –14.8, p = 0.0084). This association remained robust even after adjusting for the presence of other non-GBA1 variants (Supplementary Tables S5a-b).

a Stratification based on pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants (yellow dots) vs. variants of uncertain significance (blue dots); b stratification based on variants in high-confidence genes (red dots) vs. low-confidence genes (green dots). The overall variant burden of pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants or VUS did not differ significantly between groups when both high- and low-level confidence genes were considered. However, variants in high-confidence genes (both pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants and VUS) were significantly enriched in patients (p-values from Kruskal-Wallis test).

Discussion

We present the spectrum of genetic variations found in a cohort of PD patients and controls from the island-based population of Crete, which demonstrates characteristics of an ‘isolated’ population. Over a four-year period, we combined data from genotyping, WES and PCR-RFLP assays to maximize the yield of genetic screening. An underlying genetic substrate justifying a molecular diagnosis was revealed in 13.4% of patients, including PD cases linked to GBA1, LRRK2, SNCA and homozygous P/LP variants in recessive genes (PINK1, FIG4). This diagnostic yield is comparable to that reported in the ROPD study (~14.0%), an international large-scale effort focused on identifying genetic PD, including GBA1-related, through targeted screening24.

This relatively high yield in our cohort was largely driven by GBA1 carriers, who represented 10.3% of all patients, similarly to reports in other series (5–15%), including Mediterranean countries25,26,27. This proportion is comparable to previous estimates of GBA1 frequency in the mainland Greek population28,29. The enrichment of GBA1 in the Cretan population is illustrated by the identification of one patient with rapid disease progression, who was homozygous for the GBA1 risk variant p.T408M. Another patient with an aggressive PD course, early dementia and severe neuropsychiatric manifestations carried two GBA1 variants, p.D448H and p.H294Q. Though it was not possible to determine whether these variants were in cis or in trans, they have been previously reported together as a “double-mutant allele” in a Serbian cohort30. Our patient’s Albanian origin raises the possibility of a shared Balkan ancestry for this allele combination, given that the variant p.H294Q was also reported in a Greek cohort as either a double-mutant allele (p.D448H;p.H294Q) or alone28.

The variant burden analysis between patients and controls underscored GBA1 as an important risk factor in our cohort, aligning with global trends. GBA1 carriers exhibit a 5- to 30-fold higher risk of developing PD depending on age, ethnicity, and the specific GBA1 variants involved25. Consistent with this, GBA1-carriers in our cohort were approximately 4.3 times more likely to be diagnosed with PD compared to non-carriers, after adjusting for sex and age. VUS in GBA1 also emerged as a significant risk factor, as they were associated with a markedly earlier AAO of almost 8 years when adjusting for other genetic and demographic factors. Carriers of the rare GBA1 variants p.K237T and p.C55S resembled the GBA1-related phenotype31; while both these variants are reported in the GBA1-PD Browser as ‘severe’, we did not detect any published cases of carriers in our literature search. On the other hand, few PD patients carrying the rare variant p.R502H have been reported, including one patient in a Greek familial PD cohort29. Moreover, and in line with our observations, a recent large meta-analysis identified both p.T408K and p.E365K as significant risk factors for PD3, further supporting their pathogenic relevance.

Genetic differences between the Cretan population and the Greek mainland were further implied by the fact that the only SNCA mutation carrier in our cohort was of Greek, non-Cretan background. Two cases of homozygous recessive P/LP variants were identified, both involving patients with EOPD and clinical features suggestive of monogenic PD. One patient carried a novel loss-of-function variant in PINK1 (p.Y295Ter), detected through WES. The other was homozygous for the rare FIG4 variant (p.I41T), a genetic substrate which has been associated with childhood-onset, demyelinating Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 4J (CMT4J)32. To date, our patient is the second reported homozygous case with parkinsonism33 and the only one with PD, benign progression, and no signs of neuropathy in serial neurophysiological studies, shedding light on the multifarious role of FIG4 in neurodegeneration.

GCH1 variants were detected in 4.7% (n = 17) of patients, with four cases meeting the criteria for a molecular diagnosis in the absence of a more plausible genetic cause. All four carried one or two copies of the rare variants p.T94M or/and p.M1?. While few heterozygous cases have linked these variants to dopamine-responsive dystonia (DRD) with incomplete penetrance34,35,36, their association with familial PD remains unconfirmed. Consistent with our patients’ presentation, GCH1 has been implicated in adult-onset Parkinsonism with abnormal DaTscan, even without a family history for either DRD or PD/Parkinsonism37. Notably, the p.T94M variant was found in one of our patients who also carried the GBA1 variant p.L483P, presenting with severe tremor-dominant sporadic EOPD (AAO 41.9) and early cognitive decline. Whether GCH1 variants exert an independent pathogenic effect or act synergistically with other genetic or environmental factors warrants further investigation in larger datasets.

The fact that the majority of patients with familial PD (82.5%) and sporadic EOPD (76.6%) remained without a molecular diagnosis, even after WES, highlights the degree of genetic uncertainty in PD and the need for in-depth genetic analysis. The horizontal inheritance pattern observed in two sibling pairs in our extended cohort (including blood-related relatives) suggests that undetected pathogenic variants (e.g., residing in non-coding regions or involving structural variations) may be present, particularly given that these sibling pairs already shared a P/LP heterozygous PINK1 or PRKN variant, respectively. Much controversy surrounds distinct mono-allelic cases (e.g., p.R275W in PRKN), which can increase in cohorts of high consanguinity, creating a pseudo-dominant effect and overlooking the role of cryptic biallelic mutations38,39,40.

This is the largest genetic study conducted in a Mediterranean island-based population. A Sardinian case-control study found no major contribution from known PD-causing genes, with the exception of GBA1, which showed modest enrichment, though much lower than that observed in our cohort (~4.4%)41. A similar frequency was reported in a study involving PD patients of Sicilian ancestry (4.0–4.8%)42, whereas no shared variants were identified in a case-control study from Cyprus43.

Investigation of variant pathogenicity is a challenging and delicate process, requiring several layers of evidence to strengthen any findings. The ACMG criteria were introduced to provide consistency in variant interpretation, as they integrate multiple sources of evidence, stratified according to escalating confidence levels44. Different combinations of these criteria can result in the same pathogenicity annotation, reflecting an inclusive approach without rigid cutoff points. This is particularly important for variants lacking data in specific categories, such as functional studies, which may be unavailable for rare variants, and aligns with the nuanced nature of clinical genetics. Family studies, case-control studies, cohorts of specific clinical characteristics, and atypical case reports can offer clinical validation in these occasions. However, such approaches are often constrained by statistical power and lack detailed clinical information45, as observed in our literature search. Of note, 27 variants from the final list had no reported pathogenicity in ClinVar or Ensembl for PD, Parkinsonism or any other phenotype, including five classified as P/LP (Supplementary Table S2). No population frequency data was available in the referenced databases for 11 variants, including four P/LP. Finally, six P/LP variants and 36 VUS had no associated publications at the time of analysis, highlighting the uncertainty surrounding numerous genetic factors. Information on the loss-of-function variants was particularly scarce with all of them being either extremely rare ( < 0.001) or unreported.

Predictive tools are routinely utilized as an initial step in variant interpretation to assess potential pathogenicity of missense variants and indicate their tolerance to variation46. ACMG recommends applying the computational criterion only when multiple predictive tools agree, without specifying which or how many tools are required. Nevertheless, many of these tools rely on similar methodologies, often yielding similar outputs without offering greater confidence47. Conversely, potential discrepancies among them can result in higher rates of VUS, prompting researchers to adopt a majority-vote rule48. This approach can enhance performance, however, it does not eliminate subjectivity, while no tool combination was found to outperform others49. Meta-predictors were developed to address this issue. By providing a cumulative score of integrated predictors, the ACMG suggestion of overall agreement is honored, while single meta-predictors were found to perform better than a consensus-based approach49. REVEL, trained on pathogenic and neutral missense variants, outperformed its component tools and other meta-predictors, even when applied in unbalanced datasets (type II circularity)48,50. AlphaMissense integrates protein structural features and frequency data using an unsupervised deep learning model, thereby minimizing inherited errors and biases from prior classifications (type I circularity)46,51. With REVEL exceling in evaluating well-known variants and AlphaMissense offering advantages in the interpretation of variants with limited evidence, both tools were incorporated into our methodology.

While meta-predictors’ thresholds in our study were based on developer recommendations and published data, the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Working Group has recently reported that same genome-wide thresholds may be unreliable across different genes52. About 70% of the regions tested in 3668 disease-related genes did not match the expected accuracy based on genome-wide thresholds, suggesting that gene-specific calibration is needed for more precise classification. Though REVEL was identified as the best-performing predictor in this process, 22% of the ClinVar VUS fell into gene regions with poor fit. After using the web tool created by the same group to evaluate genome-wide thresholds’ reliability (https://calibration.gs.washington.edu/shiny/calibration/), we found that the majority of the genes studied in our cohort lacked sufficient information about whether the genome-wide thresholds were suitable for use, while few discordant areas were present, highlighting the need for more focused studies in neurodegenerative disorders and PD with clinical and functional validation.

Despite its small numbers, our cohort represents a clinically relevant dataset, which demonstrates distinct differences from open datasets commonly utilized in genetic research. Analysis of large-scale genomic databases can provide sufficient power to draw safer conclusions, while they are necessary to improve predictions of newer machine learning techniques. However, big datasets often include too much unverified data (e.g., lack of clinical information), producing numerous missense variants with unclear biological significance47. Pathogenic annotations from well-established sources, like ClinVar, are often provided directly by submitters and aggregated to reflect consensus or disagreement53, while predictions from in silico tools might also be considered, further emphasizing data circularity and biased interpretations. Clinically representative datasets contain variants found in medical and diagnostic settings in real-world patients. Predictive tools often perform better in open datasets, as they are more controlled and curated, while clinically representative datasets reflect the real-world complexity of genetic testing and challenges faced by clinicians when interpreting results49.

Our study is not without limitations. Genotyping arrays, while cost-effective and informative for recurrent P/LP variants in relatively homogeneous populations like ours, are restricted to predefined loci and may miss novel, structural, or intronic changes. Although we complemented this approach with WES in a subset of individuals with strong suspicion of genetic etiology, future steps should expand to include whole-genome sequencing or long-read sequencing, where indicated, to improve variant detection, uncover cryptic biallelic mutations, and increase diagnostic yield, particularly in unresolved familial and EOPD cases. Although the relatively small sample size of the control group limited statistical power, the use of sex- and age-matched controls from the same population offered valuable insight into the genetic particularities of the Cretan population, including potential founder effects for specific GBA1 and LRRK2 variants. Incorporating copy number variant analysis, haplotype analysis or identity-by-descent metrics in future studies may help clarify patterns of genetic drift and shared ancestry in the Cretan population. Finally, the classification of variant pathogenicity remains an evolving process, subject to updates as new functional and population data emerge. Establishing longitudinal variant reclassification at few years intervals in coordination with the information provided by curated resources (e.g., ClinGen) could refine diagnostic interpretation over time, and strengthen genotype-phenotype correlations by incorporating additional clinical follow-up data.

To conclude, this case-control study explored the genetic landscape of PD on the island of Crete with particular focus on familial PD and sporadic EOPD. Our findings strengthen the role of GBA1 as a major genetic contributor in the Cretan population, and could inform targeted genetic testing and counseling in this region54, especially given the growing relevance of GBA1 in clinical trials and emerging therapeutic interventions. Our results highlight the complex and heterogeneous nature of PD, even among subpopulations within the same country. These insights underscore the need for region-specific healthcare policies (e.g., GBA1 screening as part of routine diagnostic panels) to effectively capture the full spectrum of patients’ needs, particularly in the context of the rising global prevalence of PD55.

Methods

Study participants

Participants were enrolled over a 3.5-year period (11/2020-05/2024) from the Cretan PD Cohort (CPDC), an expanding registry comprising individuals diagnosed with clinically probable PD according to the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) criteria56. Patients in the CPDC are recruited from the Movement Disorders Outpatient Clinic of the University General Hospital of Heraklion (UGHH), a tertiary referral center for Southeast Greece. Sex, ethnicity, and age at symptom onset/diagnosis/death were systematically recorded. Ethnicity was self-reported by participants and, where available, verified using medical records. Self-reported family history of PD was documented and confirmed via medical records, where available. Based on their family history and AAO, patients were grouped into three categories: (1) familial PD (positive family history up to second-degree kinship); (2) sporadic EOPD (AAO < 50 years); and (3) sporadic LOPD. Age- and sex-matched controls from the Cretan population without prior diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorder were recruited during the same period.

Whole blood samples were collected from each participant at the time of enrollment. Patients whose diagnosis changed or presented atypical characteristics during follow-up were excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the UGHH (14452/18-11-2020) and the University of Crete (179/28-09-2020). All research procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using the QIAGEN DNA purification kit (51206 FlexiGene DNA Kit Qiagen 250 ml), as per manufacturer’s instructions. Three genetic screening methods were used, including a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping array, the PCR-RFLP approach, and WES.

DNA samples were genotyped in two different laboratories due to separate institutional agreements at the time of participant enrollment (Fig. 1). Patient samples collected until May 2023 were genotyped at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland, USA (NINDS) (Dataset A); those collected during the following year, plus all control samples were genotyped by the Global Parkinson’s Genetic Program (GP2) (Dataset B). Both batches were processed using the Infinium™ Global Diversity NeuroBooster Array (v.1.0)57, developed by Illumina, following the standard protocol for Infinium LCG Genotyping Assay. This microarray is a high-throughput genotyping platform, which is enriched for variants associated with neurological diseases, enabling rapid and cost-effective screening of large cohorts.

For data preparation and QC, GenomeStudio (version 2.0), the PLINK software (version 1.9.0-beta4.4 and 3.6-alpha), and GenoTools v1.2.3 with the default settings were utilized. The LiftOver tool was used to convert the genotyping data from the hg19 to the hg38 reference genome version. Filters for missingness (>0.05), heterozygosity (>0.01), sex discrepancies, and relatedness up to second degree were applied under standard protocols. Relatedness was assessed using Genetic Relationship Matrix (GRM) analysis. Thresholds of 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 were set to indicate third-, second- and first-degree relationships, respectively, and verify information recorded from participants’ interviews. Samples with pairwise pihat values close to 1.0 were removed as duplicates. Control samples were excluded if their pairwise pihat value with a patient’s sample exceeded 0.25. If two control or patient samples had a pairwise pihat value greater than 0.25, only one was retained. Relatedness control was performed separately for each dataset due to technical constraints stemming from genotyping being conducted in different laboratories. Individuals in Dataset B who were identified through interviews as being related (up to third degree) to those in Dataset A were also excluded.

We prioritized 15 genes with robust evidence to support their association with PD/Parkinsonism (identified in at least four unrelated families, no negative reports)1 or if they were reported as pathogenic for PD/Parkinsonism in the MDSGene database (https://www.mdsgene.org/g4d, assessed on 18/11/2024). Four autosomal dominant [LRRK2 (chr12:40,196,744-40,369,285); VPS35 (chr16:46,656,132-46,689,518); SNCA (chr4:89,724,099-89,837,161); GBA1 (chr1:155,234,452-155,244,699)] and 11 autosomal recessive genes [PARK7 (chr1:7,954,291-7,985,504); ATP13A2 (chr1:16,985,958-17,011,928); PINK1 (chr1:20,633,458-20,651,511); FBXO7 (chr22:32,474,676-32,498,829); SYNJ1 (chr21:32,628,759-32,728,040); PLA2G6 (chr22:38,111,495-38,214,778); VPS13C (chr15:61,852,389-62,060,473); DNAJC6 (chr1:65,248,219-65,415,871); DCTN1 (chr2:74,361,154-74,392,087); POLG (chr15:89,305,198-89,334,861); PRKN (chr6:161,347,417-162,727,775)], classified as high-confidence genes, were included. An additional 12 genes with varying levels of evidence showing an association with PD/parkinsonism (Supplementary Table S3) were included [autosomal dominant: TMEM230 (chr20:5,068,232-5,113,087; LRP10 (chr14:22,871,740-22,881,713); VCP (chr9:35,053,928-35,072,668); GCH1 (chr14:54,842,008-54,902,826); CHCHD2 (chr7:56,094,567-56,106,479); PSAP (chr10:71,816,298-71,851,251); ATXN2 (chr12:111,443,485-111,599,676); DNAJC13 (chr3:132,417,502-132,539,032); RAB32 (chr6:146,543,833-146,554,953); GIGYF2 (chr2:232,697,299-232,860,605) and autosomal recessive: PNPLA6 (chr19:7,534,004-7,561,764); SPG7 (chr16:89,490,719-89,557,766)], plus two genes with reports linking them to parkinsonism in the Greek population [autosomal dominant: SORL1 (chr11:121,452,314-121,633,763) and autosomal recessive: FIG4 (chr6:109,690,609-109,878,098)], all classified as low-confidence genes. We used ANNOVAR (version 2020-06-08) for variant annotations (http://www.openbioinformatics.org/annovar/) of exonic regions. Synonymous and duplicate variants were removed.

Additionally, DNA samples from all PD patients were analyzed at the University of Crete to detect the GBA1 variants p.N409S or p.N370S (c.1226A>G, rs76763715) and p.L483P or p.L444P (c.1448T>C, rs421016), using the PCR-RFLP approach58,59. Both variants are considered problematic or low quality in the NeuroBooster Array analysis due to high rates of missingness57.

Finally, as part of a national initiative (National Precision Medicine Network for Neurodegenerative Disease, EDIA-N), selected DNA samples from Dataset A (strong suspicion of genetic etiology, indicated by a positive family history or early AAO < 50 years) underwent further analysis with WES. Library preparation was performed using the Twist Biosciences Comprehensive Exome Panel and Library Preparation EF Kit 2.0, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, according to Twist Comprehensive Exome Panel guides and recommendations. Bioinformatic analysis of the data was mainly based on the Genome Analysis ToolKit’s (GATK) best practices. The data quality was evaluated using FastQC (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) to assess read quality and adapter contamination, followed by quality and adapter trimming of the reads using Fastp (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp). Trimmed reads were then aligned to the human genome reference (hg19) using BWA-MEM (https://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml). The .sam file produced by the alignment was converted to .bam file that is sorted and indexed using samtools (https://www.htslib.org/). PCR duplicates were marked with Picard’s MarkDuplicates tool (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/index.html), and base quality scores recalibration was performed using GATK’s BQSR, as recommended in best practices. Exonic coverage was assessed using Mosdepth (https://github.com/brentp/mosdepth) in threshold mode. GATK’s HaplotypeCaller was used for variant calling in all exonic regions using the appropriate .bed file. Finally, functional and clinical annotation was performed using ANNOVAR (version 2020-06-08) with the latest public databases, including but not limited to ClinVar, COSMIC, OMIM, gnomAD and dbSNP.

Variant annotation and filtering

Each variant was searched in the ClinVar database (retrieved on 16/10/2024) and the Ensembl genome browser (Release 113, October 2024) (https://www.ensembl.org/index.html), using their HGVS nomenclature60. Clinical significance of each variant was noted alongside their relevant phenotypes and the provided level of assertion. Moreover, all variants were evaluated in the Franklin database (retrieved on 05/02/2025) (https://franklin.genoox.com). Throughout the above processes, rs identification numbers and maximum population frequencies were extracted. Related publications in the above databases and PubMed/MEDLINE were reviewed for each variant (until 16/01/2025), focusing on original research (not reviews or solely in silico predictions). Standard variant nomenclature was used as free text (e.g., “ATP13A2” AND (“rs1057519291” OR “T512I” OR “T517I” OR “Thr512Ile” OR “Thre517Ile”)).

Prediction scores for the computational tools REVEL50, AlphaMissense51 and SpliceAI61 were retrieved from the relevant sites (https://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics/, https://alphamissense.hegelab.org/, https://spliceailookup.broadinstitute.org/) (retrieved on 31/01/2025). Scores range from zero to one with higher values indicating a greater likelihood of a deleterious effect. Generalized, genome-wide thresholds were used to filter all variants and prioritize those potentially impactful. For REVEL, variants with a value above 0.77 were classified as ‘likely pathogenic’ with at least moderate level of evidence62. For AlphaMissense, this was provided for each variant by the developer, alongside their score. For SpliceAI, a score higher than 0.2 was suggested to distinguish potentially splice-altering variants with at least moderate level of evidence61. Interpretation of null variants was performed using the automatic classification tool AutoPVS1, developed by BGI Genomics63.

We further classified variants according to pathogenicity level, following the general principles set by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG)44. The terms ‘pathogenic’ and ‘likely pathogenic’ were merged to account for uncertainty in both directions. The following levels of evidence for each variant were taken into consideration:

-

a.

their highest frequency, as reported in the GnomAD database and the Regeneron Genetic Center (RGC) Million Exome Variant Browser (downloaded on 28/05/2024), and the databases of ClinVar, Ensembl and Franklin (sources of GnomAD, 1000 Genomes Phase 3, Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), Turkish Variome). A maximum threshold of 0.01 was used to identify ‘rare’ variants (PM2). Variants with a higher frequency were excluded (BA1/BS1), unless they presented more often among patients compared to controls, as demonstrated by well-structured meta-analyses (PS4). For recessive variants, the presence of homozygotes was also taken into consideration as a benign indication (BS2).

-

b.

their clinical significance, as reported in ClinVar or Ensembl, regarding PD or any other neurodegenerative phenotype (PP5/BP6).

-

c.

their biological impact on protein function (PS3/BS3). Pathology studies were also considered. Intolerance of each gene to variation introduced by missense variants was evaluated with a missense constraint z-score greater than 3.09 signifying increased intolerance (PP2)64 (z-scores retrieved from GnomAD v4.1.0 on 14/02/2025).

-

d.

their segregation with disease, as demonstrated by family studies, including trio and quad studies (BS4/PP1). Studies with an index patient and one parent/child or two siblings were noted but not used as a segregation criterion.

-

e.

their association with relevant phenotypes. For variants of recessive inheritance, their detection in compound heterozygous or homozygous cases with atypical phenotypes was documented (PM3). Heterozygous or compound heterozygous (with VUS) variants detected in cohorts or case reports of symptomatic individuals were noted, if there was no conflicted evidence (e.g., high frequency) (PP4). Variant detection in cases with alternative genetic causes was considered a benign indicator (BP5). Since no de novo cases were encountered for any of the assessed variants in our cohort, the PM6/PS2 criteria were not applied.

-

f.

their potential impact on the produced protein. The computational tools were used as supporting evidence in line with the ACMG guidelines. The PP3 criterion was applied when either REVEL or AlphaMissense suggested a pathogenic effect (at least moderate level of evidence). Both tools predicting a benign outcome was considered a benign indicator (BP4) (at least supporting level of evidence). PP3 was also applied when SpliceAI predicted a significant impact on splicing (at least moderate level of evidence). Loss-of-function variants (PVS1) and the presence of an alternative, likely pathogenic missense variant in the same location (PM5) were also considered.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.3). Statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed), and odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated where applicable. Categorical variables were summarized using contingency tables and compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence with Yate’s continuity correction, or Fisher’s exact test with the confidence level set at 99% in case of small sample size (expected cell count <5). Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and summarized with mean and standard deviation (SD), or median and range values in case of non-normality. Comparisons were performed using independent sample t-test or the Kruskal-Wallis test, depending on data distribution and sample size per group (Central Limit Theorem). For each variant, allele frequency was computed by dividing the number of variant alleles by the total number of alleles assessed in each dataset. The numerator was the sum of heterozygous carriers (each contributing one variant allele) and homozygous individuals (each contributing two variant alleles). This total was then divided by twice the number of individuals in the respective group (reflecting the diploid genome). A molecular diagnosis or the presence of genetic PD was defined by the identification of a heterozygous dominant or a homozygous recessive variant.

Variant burden across the three clinical groups (familial PD, sporadic EOPD, and sporadic LOPD) was assessed using Kruskal-Wallis test. Pairwise Wilcoxon test was subsequently applied for head-to-head comparisons, producing adjusted p-values. Total variant count for each category was expressed with mean values, as the median variant count was zero in nearly all cases due to the positive skewness of the density plots, masking nuanced underlying trends. The likelihood of a molecular diagnosis (dependent variable) was assessed using a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for sex, age, and ethnicity. Notably, AAO and family history were excluded, as these variables were used a priori to define the three clinical subgroups. Most patients were enrolled shortly after their initial diagnosis, making AAO the primary driver of age-related differences and positioning age at enrollment as a mediator of AAO. Therefore, to account for age without introducing bias, we adjusted our models using disease duration (time interval between AAO and age at enrollment), as a proxy for age.

A multiple linear regression model was used to investigate the association between the presence of GBA1 variants (presence of P/LP variants or VUS as predictors) and AAO (dependent variable), after adjusting for sex, ethnicity, and disease duration. Model diagnostics were assessed through residual plots to evaluate linear regression assumptions. In an earlier exploratory model, we had additionally adjusted for the presence of non-GBA1 variants potentially accounting for a genetic cause of PD (P/LP or VUS) and for the presence of autosomal recessive variants in heterozygous state. However, these additional variables were not significantly associated with AAO and were omitted from the final model to improve interpretability. The lack of association in the preliminary model could be attributable to the small sample size of these subcategories, the heterogeneity in the variants/genes included, or to a genuine lack of effect in this patient population. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated from an ordinary least squares model to assess the absence of multicollinearity.

Only variants shared among Datasets A and B were included in the variant burden analysis between PD patients and controls. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to estimate the effect size of different variant categories on the odds of having PD, adjusted for sex and age at enrollment. To minimize population stratification and ensure genetic comparability, and since all controls were Greek, patients of non-Greek ethnicity were excluded. Following removal, patients and controls were still matched for sex and age at enrollment. Given the low frequency of variant counts, binary variables indicating the presence or absence of variants were created. This was done to capture potential non-linear associations between variant burden and the log-odds of the outcome. Model assumptions were considered valid given the sample size and nature of the predictors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the University of Crete and the University General Hospital of Heraklion, Crete, given the sensitive nature of genetic data. However, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. In addition, the subset of data analyzed by the Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2) (release 9.0) may be made available to qualified researchers through the AMP PD portal after obtaining access permission.

Change history

21 January 2026

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-026-01267-1

References

Blauwendraat, C., Nalls, M. A. & Singleton, A. B. The genetic architecture of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 19, 170–178 (2020).

Jia, F., Fellner, A. & Kumar, K. R. Monogenic Parkinson’s disease: genotype, phenotype, pathophysiology, and genetic testing. Genes 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13030471 (2022).

Pitz, V. et al. Analysis of rare Parkinson’s disease variants in millions of people. NPJ Park. Dis. 10, 11 (2024).

Escott-Price, V. et al. Polygenic risk of Parkinson disease is correlated with disease age at onset. Ann. Neurol. 77, 582–591 (2015).

Dawson, T. M., Golde, T. E. & Lagier-Tourenne, C. Animal models of neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1370–1379 (2018).

Schneider, S. A., Hizli, B. & Alcalay, R. N. Emerging targeted therapeutics for genetic subtypes of Parkinsonism. Neurotherapeutics 17, 1378–1392 (2020).

Zhu, H., Hixson, P., Ma, W. & Sun, J. Pharmacology of LRRK2 with type I and II kinase inhibitors revealed by cryo-EM. Cell Discov. 10, 10 (2024).

Cook, L. et al. Parkinson’s disease variant detection and disclosure: PD GENEration, a North American study. Brain 147, 2668–2679 (2024).

Smith, L. J., Lee, C. Y., Menozzi, E. & Schapira, A. H. V. Genetic variations in GBA1 and LRRK2 genes: biochemical and clinical consequences in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurol. 13, 971252 (2022).

Junker, J. et al. Understanding monogenic Parkinson’s disease at a global scale. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.03.12.24304154 (2024).

Heutink, P. & Oostra, B. A. Gene finding in genetically isolated populations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 2507–2515 (2002).

Hellenic Statistical Authority. Census Results of Population and Housing, https://www.statistics.gr/el/2021-census-res-pop-results?inheritRedirect=true (2021).

Spanaki, C. & Plaitakis, A. Bilineal transmission of Parkinson’s disease on Crete suggests a complex inheritance. Neurology 62, 815–817 (2004).

Dhar, D. et al. Islands and neurology: an exploration into a unique association. Neuroscientist, 10738584241257927 https://doi.org/10.1177/10738584241257927 (2024).

Hughey, J. R. et al. A European population in Minoan Bronze Age Crete. Nat. Commun. 4, 1861 (2013).

Skourtanioti, E. et al. Ancient DNA reveals admixture history and endogamy in the prehistoric Aegean. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 290–303 (2023).

Drineas, P. et al. Genetic history of the population of Crete. Ann. Hum. Genet. 83, 373–388 (2019).

King, R. J. et al. Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian influences on the Greek and Cretan Neolithic. Ann. Hum. Genet. 72, 205–214 (2008).

Arnaiz-Villena, A. et al. Cretan HLA genetics supports its early Minoan culture as a link between North Africa and Europe. Hum. Immunol. 85, 110799 (2024).

Panoutsopoulou, K. et al. Genetic characterization of Greek population isolates reveals strong genetic drift at missense and trait-associated variants. Nat. Commun. 5, 5345 (2014).

Spanaki, C., Latsoudis, H. & Plaitakis, A. LRRK2 mutations on Crete: R1441H associated with PD evolving to PSP. Neurology. 67, 1518–1519 (2006).

Kara, E. et al. Assessment of Parkinson’s disease risk loci in Greece. Neurobiol. Aging. 35, 442.e449–442.e416 (2014).

Boura, I. Mitsias, P., Erimaki, S., Papadaki, E., Spanaki, C. A new phenotype-genotype correlation for FIG4 and Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.70319 (2025).

Skrahina, V. et al. The Rostock International Parkinson’s Disease (ROPAD) study: protocol and initial findings. Mov. Disord. 36, 1005–1010 (2021).

Smith, L. & Schapira, A. H. V. GBA1 Variants and Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and treatments. Cells 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11081261 (2022).

Petrucci, S. et al. GBA1-related parkinson’s disease: dissection of genotype-phenotype correlates in a large Italian cohort. Mov. Disord. 35, 2106–2111 (2020).

Gómez-Garre, P. et al. Understanding Parkinson’s disease in Spain: genetic and clinical insights. Eur. J. Neurol. 32, e16499 (2025).

Moraitou, M. et al. β-Glucocerebrosidase gene mutations in two cohorts of Greek patients with sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Genet Metab. 104, 149–152 (2011).

Bozi, M. et al. Genetic assessment of familial and early-onset Parkinson’s disease in a Greek population. Eur. J. Neurol. 21, 963–968 (2014).

Kumar, K. R. et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in a Serbian Parkinson’s disease population. Eur. J. Neurol. 20, 402–405 (2013).

Menozzi, E. & Schapira, A. H. V. Exploring the genotype-phenotype correlation in GBA1-Parkinson disease: clinical aspects, biomarkers, and potential modifiers. Front. Neurol. 12, 694764 (2021).

Boura, I. et al. FIG4-related Parkinsonism and the particularities of the I41T mutation: a review of the literature. Genes 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15101344 (2024).

Georgiades, M. J. et al. Not so smooth sailing: FIG4-related disease is a differential diagnosis of rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.70049 (2025).

Ahn, T. B. et al. Residual signs of DOPA-responsive dystonia with GCH1 mutation following levodopa treatment are uncommon in Korean patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 65, 248–251 (2019).

Lee, J. H. et al. Dopa-responsive dystonia with a novel initiation codon mutation in the GCH1 gene misdiagnosed as cerebral palsy. J. Korean Med. Sci. 26, 1244–1246 (2011).

Naiya, T. et al. Occurrence of GCH1 gene mutations in a group of Indian dystonia patients. J. Neural Transm. 119, 1343–1350 (2012).

Mencacci, N. E. et al. Parkinson’s disease in GTP cyclohydrolase 1 mutation carriers. Brain 137, 2480–2492 (2014).

Lubbe, S. J. et al. Assessing the relationship between monoallelic PRKN mutations and Parkinson’s risk. Hum. Mol. Genet. 30, 78–86 (2021).

Zhu, W. et al. Heterozygous PRKN mutations are common but do not increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 145, 2077–2091 (2022).

Sharma, K. et al. A Novel p.F385S loss-of-function mutation in an Indian family with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 39, 1217–1225 (2024).

Quadri, M. et al. An exome study of Parkinson’s disease in Sardinia, a Mediterranean genetic isolate. Neurogenetics 16, 55–64 (2015).

Salemi, M. et al. A next-generation sequencing study in a cohort of Sicilian patients with Parkinson’s disease. Biomedicines 11 (2023).

Georgiou, A. et al. Genetic and environmental factors contributing to Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study in the Cypriot population. Front. Neurol. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01047 (2019).

Richards, S. et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424 (2015).

Rodrigues, E. D. S. et al. Variant-level matching for diagnosis and discovery: challenges and opportunities. Hum. Mutat. 43, 782–790 (2022).

Grimm, D. G. et al. The evaluation of tools used to predict the impact of missense variants is hindered by two types of circularity. Hum. Mutat. 36, 513–523 (2015).

Hicks, S., Wheeler, D. A., Plon, S. E. & Kimmel, M. Prediction of missense mutation functionality depends on both the algorithm and sequence alignment employed. Hum. Mutat. 32, 661–668 (2011).

Ghosh, R., Oak, N. & Plon, S. E. Evaluation of in silico algorithms for use with ACMG/AMP clinical variant interpretation guidelines. Genome Biol. 18, 225 (2017).

Gunning, A. C. et al. Assessing performance of pathogenicity predictors using clinically relevant variant datasets. J. Med. Genet. 58, 547–555 (2021).

Ioannidis, N. M. et al. REVEL: an ensemble method for predicting the pathogenicity of rare missense variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 877–885 (2016).

Cheng, J. et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 381, eadg7492 (2023).

Tejura, M. et al. Calibration of variant effect predictors on genome-wide data masks heterogeneous performance across genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 111, 2031–2043 (2024).

Landrum, M. J. et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D862–D868 (2016).

Vieira, S. R. L. et al. Consensus guidance for genetic counseling in GBA1 variants: a focus on Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 39, 2144–2154 (2024).

Su, D. et al. Projections for prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and its driving factors in 195 countries and territories to 2050: modelling study of Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMJ 388, e080952 (2025).

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

Bandres-Ciga, S. et al. NeuroBooster array: a genome-wide genotyping platform to study neurological disorders across diverse populations. Mov. Disord. 39, 2039–2048 (2024).

Todd, R., Donoff, R. B., Kim, Y. & Wong, D. T. From the chromosome to DNA: restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and its clinical application. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 59, 660–667 (2001).

Kanellopoulou, V., Panayotopoulou, N., Skoula, I. & Spanaki, C. Phenotype-genotype correlations of GBA1 mutations in Parkinson disease patients from the Island of Crete. J. Neurol. Sci. 357, e288 (2015).

Hart, R. K. et al. HGVS Nomenclature 2024: improvements to community engagement, usability, and computability. Genome Med. 16, 149 (2024).

Jaganathan, K. et al. Predicting splicing from primary sequence with deep learning. Cell 176, 535–548.e524 (2019).

Pejaver, V. et al. Calibration of computational tools for missense variant pathogenicity classification and ClinGen recommendations for PP3/BP4 criteria. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 109, 2163–2177 (2022).

Xiang, J., Peng, J., Baxter, S. & Peng, Z. AutoPVS1: an automatic classification tool for PVS1 interpretation of null variants. Hum. Mutat. 41, 1488–1498 (2020).

Harrison, S. M., Biesecker, L. G. & Rehm, H. L. Overview of specifications to the ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 103, e93 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out within the framework of the Action ‘Flagship Research Projects in challenging interdisciplinary sectors with practical applications in Greek industry’, implemented through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan Greece 2.0 and funded by the European Union— NextGenerationEU (project code: TAEDR-0535850), and within the framework of the Project CHAangeing—Connected Hubs in Ageing: Healthy Living to Protect Cerebrovascular Function, funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Program (Excellence Hubs Call – Horizon-WIDERA-2022-ACCESS-04-01 under grant agreement No 101087071). This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) (program #: ZIANS003154). The contributions of the NIH authors were made as part of their official duties as NIH federal employees, are in compliance with agency policy requirements, and are considered words of the United States Government. However, the findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Part of the data used in the preparation of this manuscript was obtained from Global Parkinson’s Genetics Program (GP2). GP2 is funded by the Aligning Science Across Parkinson’s (ASAP) initiative and implemented by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (https://gp2.org). For a complete list of GP2 members see https://gp2.org. We gratefully acknowledge all individuals who participated in this study. We also thank the neurologists across the island of Crete who referred patients to our center for research participation. We are especially grateful to I. Skoula, Chief Technician of the Neurology Laboratory at the University of Crete, for training members of our team in research procedures, including laboratory techniques and sample storage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization & study design: I.B., G.X. and C.S. conceived and designed the study; Data collection: I.B. collected clinical data and blood samples, performed DNA extraction, and organized samples shipment; Clinical data curation: I.B., P.MI. and C.S. organized and verified the clinical dataset; Genetic analysis: S.S., A.K., R.C., A.R. and S.W.S. performed genotyping, N.M.M., G.V., T.L. and P.M.A. performed WES, and V.P. performed PCR-based screening for selected GBA1 variants; Interpretation of genetic findings: I.B., S.S., N.M.M., G.X., P.M.A., S.W.S. and C.S. performed variant interpretation and classification; Statistical analysis: I.B., N.M.M., G.X., S.W.S. and C.S. conducted the statistical modeling and interpretation; Figure and table preparation: I.B. prepared all figures, tables, and supplementary material; Drafting the manuscript: I.B. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; Critical revision: N.M.M., P.MI., G.X., P.M.A., S.W.S. and C.S. reviewed and revised the manuscript; Supervision: P.MI., G.X., S.W.S. and C.S. supervised the project and provided overall guidance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

I.B. has received research funding from the Project CHAngeing - Connected Hubs in Ageing: Healthy Living to Protect Cerebrovascular Function (grant agreement 101087071), funded by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Program (Excellence Hubs Call—Horizon-WIDERA-2022-ACCESS-04-01, and the European Union-NextGeneration EU (project code: TAEDR-0535850), as well as honoraria for educational and travel grants from AbbVie. P.MI. has received research funding from the Hellenic Precision Medicine Network, the European Union Horizon 2020 research innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101007926 and the European Union’s Horizon Europe Program (Excellence Hubs Call – Horizon-WIDERA-2022-ACCESS-04-01 under grant agreement No 101087071). G.X. has received honoraria for lecturing, advisory fees, educational grants, and travel grants from ITF Hellas, Innovis, AbbVie, and Teva. S.W.S. receives research support from Cerevel Therapeutics, she is a scientific advisory board member of the Lewy Body Dementia Association, Mission MSA, and the GBA1 Canada Initiative, and an editorial board member of JAMA Neurology and the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease. C.S. has received research funding from the Greek National Precision Medicine Network, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101007926, the European Union-NextGeneration EU (project code: TAEDR-0535850), and the European Union’s Horizon Europe Program (Excellence Hubs Call – Horizon-WIDERA-2022-ACCESS-04-01 under grant agreement No 101087071), as well as honoraria for lecturing, advisory fees, educational grants, and travel grants from ITF Hellas, Innovis, Merck Serono, AbbVie, CSL Behring, Roche and Teva. All other authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boura, I., Sait, S., Marinakis, N.M. et al. The genetic architecture of Parkinson’s disease on the Island of Crete. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 354 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01192-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01192-9