Abstract

Although muscle mass loss is an emerging public health concern, its prevalence, associated factors, and clinical significance in Parkinson’s disease (PD) remain unclear. This matched case-control study aimed to investigate the prevalence of low muscle mass (LMM) and to examine its association with orthostatic hypotension (OH) and orthostatic symptoms in 409 PD patients with Hoehn and Yahr stage ≤3, compared with 2045 age-, sex-, and height-matched controls from a nationwide database. OH was defined according to the international consensus. LMM was more prevalent in PD patients than in controls, particularly among men and those aged ≥70 years. Among PD patients, the prevalence of OH did not differ between those with and without LMM. Although LMM was linked to greater orthostatic blood pressure reductions at 30 s after standing, there were no differences in the frequency or severity of orthostatic symptoms according to LMM status. These findings suggest that although mild to moderate PD is associated with an increased risk of LMM, its impact on OH and related symptoms appears to be modest. Further longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the clinical implications of LMM in PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Muscle mass loss is a key parameter of sarcopenia that is emerging as a critical health issue, contributing to reduced mobility and poor quality of life1,2. In patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD), this condition may be attributed to overlapping pathomechanisms, including disruptions in the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy3,4, along with common risk factors such as chronic inflammation, physical inactivity, and weight loss5,6. Of note, a recent study has shown that α-synuclein aggregation, a hallmark of PD pathology, at the neuromuscular junction induces intramuscular mitochondrial oxidative stress and subsequent muscle atrophy7. In this context, low muscle mass (LMM) is expected to become more prevalent as PD progresses, particularly in its advanced stages. However, it remains unclear whether such a condition occurs even during the relatively mild stages of the disease. Although previous studies investigated the prevalence of LMM in patients with PD, results were inconsistent, primarily due to small sample sizes in both case and control groups8. In addition, how the prevalence of LMM in PD varies by demographic and clinical factors has not been investigated.

Orthostatic hypotension (OH) is one of the most frequent non-motor features in PD that occurs from the early stages of the disease and sometimes develops before the onset of motor symptoms9,10. Accumulating evidence suggests that the presence of OH is closely associated with negative outcomes in PD11,12,13,14. Mechanisms underlying OH in PD are not fully understood; however, reduced norepinephrine release from postganglionic efferent sympathetic nerves due to α-synuclein deposition leads to impaired vasoconstriction, which may exacerbate the inability to maintain blood pressure (BP) upon assuming an upright posture15. Furthermore, functional MRI studies have revealed disruptions in the central autonomic network involving the hypothalamus, insular cortex, and limbic areas, in patients with PD, leading to autonomic dysfunction16,17.

Inadequate muscle mass does not effectively counteract the increased venous pooling and decreased cardiac preload induced by gravity upon abrupt standing18,19,20, and has also been associated with hypoperfusion in key hubs of the central autonomic network within the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum21. Accordingly, muscle mass volume may play a pivotal role in modulating OH and related symptoms in patients with PD and could represent a potentially modifiable risk factor for their management. However, whether LMM is associated with OH and related symptoms in PD remains unexplored.

To address the above issues, we compared the prevalence of LMM in patients with mild to moderate PD, using prospectively collected single-center data, with that in the general population based on a large national health survey. We further examined whether orthostatic BP changes and symptoms differ according to the presence of LMM in patients with PD. We hypothesized that LMM is prevalent even in mild to moderate stages of PD and that it is closely linked to OH and related symptoms.

Results

Participant characteristics

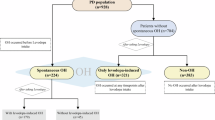

We initially identified 409 patients with PD enrolled at Inha University Hospital during the study period, along with 8226 controls from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) data, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplementary Fig. S1). Subsequently, a 1:5 matching ratio was applied based on age, sex, and height, resulting in the inclusion of 409 patients and 2045 matched controls in the final analysis. Their demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean (± standard deviation) age and disease duration of the patients with PD were 71.1 ± 9.5 years and 4.8 ± 4.7 years respectively, and 214 (52.3%) patients were men. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or height between the PD and control groups, confirming the adequacy of the matching process.

Prevalence of LMM in PD compared to controls

The prevalence of LMM in the overall population and in subgroups stratified by age and sex is shown in Fig. 1. Among 409 patients with PD, 143 (35.0%) met the criteria for LMM, which was significantly higher compared with the control group (24.8% [507 of 2045]; P < 0.001). Multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusting for age and sex showed that the estimated odds ratio (OR) for having LMM was 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29–2.03) for patients with PD. Sensitivity analyses showed that the prevalence of LMM in the control group decreased slightly to 21.7%, and the findings supported the primary results (Supplementary Fig. S2).

In sex-specific analyses, men with PD had a significantly higher prevalence of LMM compared with controls (43.9% vs 29.6%; P < 0.001), whereas no significant difference was observed between women with PD and controls (25.1% vs 20.0%; P = 0.105). The estimated OR for having LMM was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.35–2.49) for men with PD. When stratified by age, the prevalence of LMM in the PD group was 38 of 176 (21.6%) among individuals younger than 70 years and 105 of 233 (45.1%) among those aged 70 years or older. Compared with controls, the prevalence of LMM in the PD group was significantly higher among individuals aged 70 years or older (45.1% vs 29.9%; P < 0.001), but not among those younger than 70 years (21.6% vs 17.8%; P = 0.232). The estimated OR for having LMM was 1.93 (95% CI, 1.42–2.61) for patients with PD aged 70 years or older. These results remained consistent in the sensitivity analyses (Supplementary Fig. S2).

In the PD group, the prevalence of LMM was significantly higher in men (P < 0.001) and in individuals aged 70 years or older (P < 0.001), while no significant differences were observed according to disease duration (≥3 years, 35.0% vs. <3 years, 34.7%; P = 0.920), disease severity (Hoehn and Yahr [H&Y] stage 1–2, 32.0% vs. H&Y 2.5–3, 42.3%; P = 0.603) or cognitive status (Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] score ≥21, 30.2% vs. <21, 40.0%; P = 0.912).

Association of LMM with OH and orthostatic symptoms in PD

Among the enrolled patients with PD, 4 had missing orthostatic BP data; thus, 405 patients were included in this analysis. Of these, 141 patients were assigned to the LMM group, while the remaining 264 patients were assigned to the normal muscle mass (NMM) group. Compared with the NMM group, the LMM group was older, had a later age at disease onset, greater height, weight, and body mass index, and showed a trend toward more severe motor impairment (Table 1). Subgroup analyses by sex showed baseline characteristics similar to those of the total population (Supplementary Tables S1, S2).

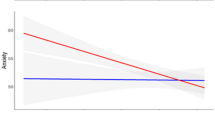

OH was present in 46.8% of the LMM group and 38.6% of the NMM group, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.412) (Table 2). Similarly, the prevalence of systolic OH did not differ significantly between the groups (LMM, 26.2% vs NMM, 17.8%; P = 0.359). Although diastolic OH also did not reach statistical significance, there was a trend toward higher prevalence in the LMM group (LMM, 25.5% vs NMM, 14.8%; P = 0.064). Figure 2 illustrates the changes in BP after transitioning from the supine to the upright position. There were significant differences in orthostatic changes over time in systolic BP (SBP) (P = 0.036) and diastolic BP (DBP) (P = 0.009) between the LMM and NMM groups. Exploratory analyses showed a significant decrease in BP at 30 seconds after standing, with greater reductions observed in the LMM group compared to the NMM group; SBP decreased by −18.7 ± 1.7 mmHg vs. −13.0 ± 1.1 mmHg (P = 0.020), and DBP decreased by −7.8 ± 1.1 mmHg vs. −4.2 ± 0.6 mmHg (P = 0.012) (Table 2). Following adjustment for multiple comparisons, the reduction in DBP remained statistically significant (Bonferroni-corrected P = 0.048), whereas the reduction in SBP did not (Bonferroni-corrected P = 0.080). There were no significant differences in orthostatic BP changes at 1, 3, and 5 min. The LMM group showed greater increases in heart rate (HR) during the head-up tilt test compared with the NMM group (P = 0.043), but the magnitude of this difference was minimal (Supplementary Fig. S3). With respect to orthostatic symptoms, although they were more frequent and severe across all items in the LMM group, no statistically significant differences were observed between the groups (Table 3).

The results of sex-stratified analyses are shown in Supplementary Tables S3, S4. The prevalence of OH, as well as systolic and diastolic OH, did not differ significantly between the LMM and NMM groups in both men and women. Orthostatic BP changes over time significantly differed between the LMM and NMM groups in men (P = 0.022 for SBP and P = 0.041 for DBP), but not in women (P = 0.303 for SBP and P = 0.487 for DBP). In men, the LMM group showed greater SBP (−21.6 ± 1.7 mmHg vs. −16.1 ± 1.7 mmHg; P = 0.026) and DBP (−9.4 ± 1.1 mmHg vs. −5.4 ± 1.0 mmHg; P = 0.030) reductions at 30 s after standing compared with the NMM group. However, these associations did not remain significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. The prevalence and severity of orthostatic symptoms were not significantly different between the LMM and NMM groups in both sexes (Supplementary Tables S5, S6).

Discussion

In the current study, we found that the prevalence of LMM was 35% among patients with mild to moderate PD, a rate significantly higher than that observed in well-matched controls from a nationally representative dataset. These findings are in line with previous meta-analyses on sarcopenia in PD8,22. Notably, our results suggest that muscle mass status in patients with PD is influenced more strongly by age and sex than by disease severity, highlighting the importance of routine monitoring to detect and manage muscle mass decline, particularly in older male patients. Reported prevalence rates of LMM in PD range from 7.4% to 47.7%, with studies in Asia documenting rates between 20.4% and 36.2% (Supplementary Table S7)23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, existing data are mainly driven from Asian countries, and reported prevalence across studies varies substantially due to differences in diagnostic criteria, measurement tools (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry [DXA] vs. bioelectrical impedance analysis [BIA]), and population demographics. Moreover, the small sample sizes of previous studies limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions. In this study, we enrolled a relatively large number of consecutive patients from an outpatient clinic, with enrollment blinded to muscle mass status. This approach likely provides a more accurate estimate of LMM prevalence, particularly in mild to moderate stages of PD.

While the mechanisms underlying LMM in PD remain incompletely understood, multiple contributing factors have been proposed. Aggregation of α-synuclein at neuromuscular junctions and within intramuscular motor neuron axons may disrupt synaptic transmission, impair acetylcholine release, and induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction7. These processes can result in motor unit degeneration and muscle atrophy, suggesting that LMM in PD may not be merely a secondary complication but also an intrinsic consequence of disease progression. Alternatively, circulating inflammatory mediators, including C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor, have been shown to mediate the progression of both PD and sarcopenia, indicating that elevated inflammatory activity may play a role in muscle degradation in PD5. In addition, as the disease progresses, patients with PD often experience reduced physical activity due to motor impairments and malnutrition caused by dysphagia and metabolic alterations, all of which collectively accelerate muscle mass loss5,6. However, these factors are particularly prevalent in advanced PD. Since this study included only patients with mild to moderate PD who were able to maintain a relatively stable level of daily activity, such influences are less likely to have affected our results.

One important finding of the present study was the association between LMM and greater orthostatic BP reductions, particularly during the early phase of standing. This relationship may be mediated by two mechanisms through which LMM contributes to orthostatic BP decline: central autonomic dysfunction and peripheral hemodynamic impairment. The central mechanism involves dysfunction of the central autonomic network responsible for cardiovascular autonomic control. A previous study showed that individuals with LMM had reduced cerebral blood flow to key regions of the central autonomic network, including the insula, anterior cingulate cortex, subcallosal area, gyrus rectus, hypothalamus, amygdala, and caudate nucleus21. Accordingly, it is postulated that LMM may further impair the already disrupted connectivity of the central autonomic network in patients with PD. The peripheral mechanism suggests that muscle wasting impairs venous return, leading to orthostatic BP instability. Skeletal muscle supports central blood volume maintenance during postural change through muscle pumping action20,31,32. Reduced muscle mass weakens this function, which results in decreased venous return, cardiac preload, stroke volume, and ultimately cerebral perfusion. Additionally, the loss of muscle-derived vasoactive mediators may impair peripheral vasoconstriction33,34, thereby exacerbating orthostatic BP reductions.

However, while LMM was associated with a greater early orthostatic BP decline, the association was modest, and the mean reduction remained below the diagnostic threshold for OH. Similarly, LMM was not clearly associated with orthostatic symptoms. This near-threshold decline may not be sufficient to provoke OH or orthostatic intolerance in patients with PD. The early BP drop observed at 30 s after standing may reflect a transient hemodynamic instability, which can be partially buffered by compensatory mechanisms such as autonomic adjustments and the skeletal muscle pump, potentially limiting its clinical impact. Importantly, given that initial OH, which occurs within 15 s of standing, is closely linked to orthostatic symptoms35, the inability to capture these very early BP changes in our study may partly explain the disconnect between early BP reductions and orthostatic symptoms. Moreover, previous studies have highlighted that risk factors for OH in PD differ partly from those in the general population, with disease-specific mechanisms such as sympathetic noradrenergic denervation being particularly important12,36. Nevertheless, the proximity of the mean SBP reduction in the LMM group (−18.7 mmHg) to the diagnostic threshold (−20.0 mmHg) suggests that other factors beyond muscle mass are likely to play a more substantial role in the development of orthostatic symptoms in PD. HR changes may be an important compensatory factor in the relationship between orthostatic BP changes and related symptoms. However, we observed only a modestly greater increase in HR during the head-up tilt test, which is unlikely to be adequate to mitigate the symptomatic impact of larger orthostatic BP declines.

Alternatively, although our study focused on muscle mass, which is a core component of sarcopenia1,2, muscle function, including strength, power, and endurance, may also be critical for orthostatic BP regulation. Indeed, reduced muscle function can impair the efficacy of the skeletal muscle pump34, thereby exacerbating venous pooling and limiting compensatory hemodynamic mechanisms while standing. Supporting this mechanistic link, exercise training that enhances lower-extremity muscle performance has been shown to improve skeletal muscle pump function and venous return, which alleviate suboptimal hemodynamics and related symptoms37. In addition to LMM, accumulating evidence indicates that reduced muscle strength is common in PD8 and is associated with key motor features such as gait disturbances and falls38. However, it remains unclear how muscle function contributes to orthostatic BP dynamics in PD. Future research incorporating both structural and functional assessments of muscle health will be important to clarify their combined contribution to OH and orthostatic intolerance in PD.

Our findings revealed sex differences in two key aspects among patients with PD. First, men had a significantly higher prevalence of LMM than women. This may be attributed to sex-specific hormonal and physiological differences. Testosterone plays a critical role in stimulating muscle protein synthesis and satellite cell activation, and its gradual decline with aging39, particularly in the context of PD40, is likely to contribute to progressive muscle atrophy. Additionally, men have a higher proportion of glycolytic muscle fibers and exhibit a more pronounced proinflammatory response41, which may increase their vulnerability to muscle mass loss. Second, men showed a more pronounced orthostatic BP decline associated with LMM. Although the precise mechanism underlying this sex difference remains unclear, men’s greater lower-extremity blood volume and higher peripheral vascular resistance may promote increased venous pooling upon standing42. In contrast, women tend to have a higher proportion of blood flow directed toward the upper body and splanchnic circulation42, which may buffer orthostatic responses. With respect to central autonomic dysfunction, LMM was associated with more widespread hypoperfusion within the central autonomic network in men compared to women21, suggesting that men may be more susceptible to central autonomic impairment associated with this condition. However, the relatively small number of women with LMM in this subanalysis may have reduced the statistical power to detect sex-related differences, and thus the negative findings in women should be interpreted with caution. Future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to better elucidate the role of sex in the relationship between muscle mass and orthostatic BP changes in PD.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively examine the association between muscle mass, OH, and its related symptoms in patients with PD. Key strengths of the present study are the relatively large sample of patients with PD, the inclusion of well-matched controls, and the standardized assessment of muscle mass and orthostatic BP changes. However, several limitations warrant consideration. First, BP measurements were obtained at discrete time points, limiting the ability to evaluate continuous BP fluctuations. Accordingly, transient BP changes and hemodynamic adaptations to postural shifts, such as short-term variability and compensatory responses, could not be fully captured. In particular, this approach did not allow for the detection of initial OH, as mentioned above. Future studies using continuous BP monitoring will be necessary to clarify how LMM affects the full spectrum of orthostatic BP responses. Second, temporal differences between the KNHANES data collection period (2008–2011) and our PD enrollment period (2023–2024) may have affected the overall prevalence of LMM. Specifically, changes in demographic structure, including an increasing proportion of older adults and women and average height gain, along with evolving dietary or lifestyle patterns could potentially act as confounders. However, to mitigate these effects, we adjusted for age, sex, and height in all comparative analyses. In addition, a 2022 KNHANES study using BIA reported LMM prevalence among individuals aged ≥70 years as 34.4% in men and 36.0% in women, and among those aged <70 years as 16.3–16.7% in men and 17.8–19.4% in women43. These values are closely aligned with those observed in our 2008–2011 control group. Thus, this temporal difference is unlikely to have significantly influenced our overall findings. Third, differences between the two DXA machines (GE Prodigy Fuga and Hologic QDR Discovery) may have introduced systematic bias in muscle mass measurements. However, the main findings remained consistent in the sensitivity analysis using a cross-calibration method between the two manufacturers, suggesting that this potential bias did not meaningfully affect our results. Fourth, because this study included only Korean patients with mild to moderate PD, the findings may not be generalizable to broader populations, particularly non-Asian individuals or those with more advanced disease stages. Further studies involving more ethnically diverse and representative PD populations are warranted to validate generalizability of these results. Lastly, although medications for hypertension and OH were withheld on the morning of testing, no standardized 24-h washout protocol was applied, which may have influenced the orthostatic BP measurements. However, most patients were taking their BP medications once daily in the morning, providing an approximate 24-h washout period by the time of testing. Furthermore, commonly used OH medications such as midodrine and pyridostigmine have a relatively short duration of action (typically within 6 h), suggesting that their residual effect at the time of testing was unlikely to be significant.

In conclusion, our observations suggest that mild to moderate PD is associated with an increased risk of LMM, particularly among males and older individuals. Although LMM was linked to greater early BP reductions after standing, the magnitude of this association was modest and did not translate into an increased prevalence of OH or orthostatic symptoms. These findings indicate that the clinical relevance of early BP changes associated with LMM remains uncertain. However, given the cross-sectional nature of this study, longitudinal research is needed to assess the impact of muscle mass loss on the development and progression of OH and its associated symptoms in patients with PD.

Methods

Participants and clinical evaluation

We prospectively recruited patients with PD aged 50 years or older, at stages 1–3 on the H&Y scale from the Department of Neurology at Inha University Hospital between March 2023 and February 2024. PD was diagnosed according to the United Kingdom PD Brain Bank criteria. Patients were excluded if they had a history of cancer or hematologic malignancy, required dialysis for end-stage renal disease, severe dyskinesia that interfered with the assessment of muscle mass, or severe cognitive dysfunction that impaired their ability to participate in the study.

For comparisons, we utilized data from the KNHANES, which is an ongoing, nationwide, cross-sectional survey designed to produce nationally representative health and nutrition data for the non-institutionalized civilian population of Korea. The survey has been conducted each year since 2007 using a stratified, multistage probability sampling design with assigned sampling weights to ensure representativeness. Approximately 192 primary sample units are selected annually from census blocks or resident registration addresses; within each unit, about 20 households are chosen, and all members aged ≥1 year are invited to participate. This design yields a total sample of ~10,000 individuals per year, with a target response rate of 75%. Details of the survey design have been published previously44,45. Considering that DXA was performed only between 2008 and 2011, we analyzed data collected during that period. In this study, we excluded individuals aged under 50 years, those with a history of neurodegenerative disease, major cardiovascular disease such as myocardial infarction or stroke, cancer, or end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, as well as those without DXA data. For each patient, five controls were matched using propensity scores based on age, sex, and height.

In patients with PD, overall parkinsonian severity was assessed using the Movement Disorder Society Unified PD Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS). MDS-UPDRS Parts 1 and 2 assess non-motor and motor experiences of daily living, respectively, while Part 3 assesses the severity of motor symptoms. Cognitive function was assessed using the MoCA. Depression was assessed using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale. Autonomic symptoms were assessed using the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease–Autonomic Dysfunction (SCOPA-AUT). All evaluations were performed without discontinuation of antiparkinsonian medications.

The study protocol for PD was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital (2022-09-043), and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The dataset for controls was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (approval numbers: 2008-04EXP-01-C, 2009-01CON-03-2C, 2010-02CON-21-C, and 2011-02CON-06-C). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Assessment of muscle mass

Muscle mass was measured using DXA: Prodigy Fuga (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI) for patients with PD and QDR Discovery (Hologic, Bedford, MA) for healthy controls from the KNHANES. Appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM) was calculated as the sum of lean mass in all four limbs, and the ASM index (ASMI) was derived by dividing ASM (kg) by height squared (m²). LMM was defined as an ASMI of <7.0 kg/m² in men and <5.4 kg/m² in women, according to the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia 2019 consensus1.

Assessment of OH and orthostatic symptoms

Orthostatic BP changes were assessed using a standardized head-up tilt test in patients with PD. After achieving a fully rested state in the supine position on a flat table, the table was tilted to a 70°. BP and HR were measured at baseline (supine position) and at 30 s, 1 min, 3 min, and 5 min after transitioning to the upright position. Medications for hypertension and OH were discontinued on the day of testing. According to the international consensus, OH was defined as a drop in SBP of ≥20 mmHg (≥30 mmHg in patients with supine hypertension) or DBP of ≥10 mmHg (≥15 mmHg in patients with supine hypertension) within 3 min of standing46. Supine hypertension was defined as a SBP ≥ 150 mmHg or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg in the supine position46. Orthostatic symptoms were assessed using items 14 (lightheadedness upon standing in the past month), 15 (lightheadedness after prolonged standing in the past month), and 16 (fainting episodes in the past 6 months) from the SCOPA-AUT questionnaire, which belong to the cardiovascular autonomic domain and capture the key symptomatic manifestations of orthostatic intolerance. The presence of orthostatic symptoms was defined as a score of 1 or higher on any of these three items13,47.

In this analysis, the primary outcome was the prevalence of OH. Secondary outcomes included the prevalence of systolic and diastolic OH, longitudinal changes in SBP and DBP over time after standing, and the prevalence and severity of orthostatic symptoms. Exploratory outcomes included the magnitude of SBP and DBP changes at each time point after standing: 30 s, 1 min, 3 min, 5 min.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using R version 4.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of the data. Demographic and clinical variables were compared with the use of Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney U test, or the chi-square test, as appropriate. The prevalence of LMM was compared using multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age and sex. Given the differences in DXA machines used for the PD and control groups, we performed sensitivity analyses to enhance the robustness of our main results, in which ASM values in controls were converted using a validated cross-calibration method48. For comparisons within the PD group, disease duration was additionally included as a covariate. Subsequently, subgroup analyses were conducted according to sex (male vs. female) and age (≥70 years vs. <70 years), and among patients with PD, disease duration (≥3 years vs. <3 years) disease severity (H&Y stage 1–2 vs. H&Y 2.5–3), and cognitive status (MoCA score ≥21 vs. <21)49.

In patients with PD, multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, and disease duration were applied to assess the association of LMM with the primary outcome and the prevalence of systolic and diastolic OH and orthostatic symptoms as secondary outcomes. For the remaining secondary and exploratory outcome analyses, linear mixed-effects models with cubic regression splines for time were applied to examine the association of LMM with nonlinear SBP and DBP changes over time after standing. These models included a random intercept for participants and were adjusted for age, sex, disease duration, and baseline SBP or DBP. We used non-parametric analysis of covariance adjusted for age, sex, and disease duration to compare the severity of orthostatic symptoms and the magnitude of SBP and DBP changes at predefined time points after standing between patients with LMM and those with NMM. Although adjustments for multiple comparisons in these analyses were not primarily applied to minimize the risk of type II error given their exploratory nature, post-hoc Bonferroni corrections were conducted as needed to evaluate the robustness of the findings. Sex-stratified subgroup analyses were then performed using the same approach. Two-sided P values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Data availability

The full dataset will be available on reasonable requests from any qualified investigator.

Code availability

R scripts may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Chen, L. K. et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 21, 300–307 (2020).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48, 16–31 (2019).

Duranti, E. & Villa, C. From brain to muscle: the role of muscle tissue in neurodegenerative disorders. Biology 13, 719 (2024).

Vinciguerra, M. Sarcopenia and Parkinson’s disease: molecular mechanisms and clinical management. In Sarcopenia, Ch. 4. (eds Muscaritoli, M.) 45–62 (CRC Press: Boca Raton (FL), 2019).

Yang, J. et al. Sarcopenia and nervous system disorders. J. Neurol. 269, 5787–5797 (2022).

Murphy, K. T. & Lynch, G. S. Impaired skeletal muscle health in Parkinsonian syndromes: clinical implications, mechanisms and potential treatments. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 14, 1987–2002 (2023).

Yang, Q. et al. α-Synuclein aggregation causes muscle atrophy through neuromuscular junction degeneration. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 14, 226–242 (2023).

Hart, A. et al. The prevalence of sarcopenia in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders- a systematic review. Neurol. Sci. 44, 4205–4217 (2023).

Palma, J. A. & Kaufmann, H. Orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson disease. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 36, 53–67 (2020).

Postuma, R. B. & Berg, D. Advances in markers of prodromal Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12, 622–634 (2016).

Matinolli, M. et al. Orthostatic hypotension, balance and falls in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 24, 745–751 (2009).

Hiorth, Y. H. et al. Orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson disease: a 7-year prospective population-based study. Neurology 93, e1526–e1534 (2019).

Choi, S. et al. Associations of orthostatic hypotension and orthostatic intolerance with domain-specific cognitive decline in patients with early Parkinson disease: an 8-year follow-up. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 25, 866–870 (2024).

De Pablo-Fernandez, E. et al. Association of autonomic dysfunction with disease progression and survival in Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 74, 970–976 (2017).

Goldstein, D. S. Dysautonomia in Parkinson’s disease: neurocardiological abnormalities. Lancet Neurol. 2, 669–676 (2003).

Dayan, E. et al. Disrupted hypothalamic functional connectivity in patients with PD and autonomic dysfunction. Neurology 90, e2051–e2058 (2018).

Conti, M. et al. Insular and limbic abnormal functional connectivity in early-stage Parkinson’s disease patients with autonomic dysfunction. Cereb. Cortex 34, bhae270 (2024).

Soysal, P. et al. Relationship between sarcopenia and orthostatic hypotension. Age Ageing 49, 959–965 (2020).

Wieling, W. et al. Physical countermeasures to increase orthostatic tolerance. J. Intern Med. 277, 69–82 (2015).

Smit, A. A. et al. Pathophysiological basis of orthostatic hypotension in autonomic failure. J. Physiol. 519, 1–10 (1999).

Demura, T. et al. Sarcopenia and decline in appendicular skeletal muscle mass are associated with hypoperfusion in key hubs of central autonomic network on 3DSRT in older adults with progression of normal cognition to Alzheimer’s disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 23, 16–24 (2023).

Cai, Y. et al. Sarcopenia in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 12, 598035 (2021).

Barichella, M. et al. Sarcopenia and dynapenia in patients with parkinsonism. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 17, 640–646 (2016).

Vetrano, D. L. et al. Sarcopenia in Parkinson disease: comparison of different criteria and association with disease severity. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 19, 523–527 (2018).

da Costa Pereira, J. P. et al. Sarcopenia and dynapenia is correlated to worse quality of life perception in middle-aged and older adults with Parkinson’s disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 27, 310–318 (2024).

Tan, A. H. et al. Altered body composition, sarcopenia, frailty, and their clinico-biological correlates, in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 56, 58–64 (2018).

Tan, Y. J. et al. Osteoporosis in Parkinson’s Disease: relevance of distal radius dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and sarcopenia. J. Clin. Densitom. 24, 351–361 (2021).

Kim, M. et al. A machine learning model for prediction of sarcopenia in patients with Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS One 19, e0296282 (2024).

Murakami, K. et al. Prevalence, impact, and screening methods of sarcopenia in Japanese patients with Parkinson’s disease: a prospective cross-sectional study. Cureus 16, e65316 (2024).

Liu, Q. W. et al. Sarcopenia is associated with non-motor symptoms in Han Chinese patients with Parkinson’s Disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 23, 494 (2023).

Fadil, R. et al. Effect of Parkinson’s disease on cardio-postural coupling during orthostatic challenge. Front. Physiol. 13, 863877 (2022).

van Wijnen, V. K. et al. Noninvasive beat-to-beat finger arterial pressure monitoring during orthostasis: a comprehensive review of normal and abnormal responses at different ages. J. Intern. Med. 282, 468–483 (2017).

Kaufmann, H. et al. Plasma endothelin during upright tilt: relevance for orthostatic hypotension?. Lancet 338, 1542–1545 (1991).

Korthuis, R. J. Regulation of vascular tone in skeletal muscle. In: Skeletal Muscle Circulation, Ch. 3, (Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, San Rafael (CA), 2011).

Christopoulos, E. M. et al. Initial orthostatic hypotension and orthostatic intolerance symptom prevalence in older adults: a systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. Hypertens. 8, 100071 (2021).

Espay, A. J. et al. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension and supine hypertension in Parkinson’s disease and related synucleinopathies: prioritisation of treatment targets. Lancet Neurol. 15, 954–966 (2016).

Camden, L. et al. Augmentation of the skeletal muscle pump alleviates preload failure in patients after Fontan palliation and with orthostatic intolerance. Cardiol. Young. 35, 227–234 (2025).

Allen, N. E. et al. Reduced muscle power is associated with slower walking velocity and falls in people with Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 16, 261–264 (2010).

Volpi, E. et al. Muscle tissue changes with aging. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 7, 405–410 (2004).

Okun, M. S. et al. Testosterone therapy in Men with Parkinson disease: results of the TEST-PD study. Arch. Neurol. 63, 729–735 (2006).

Rosa-Caldwell, M. E. & Greene, N. P. Muscle metabolism and atrophy: let’s talk about sex. Biol. Sex. Differ. 10, 43 (2019).

Cheng, Y. C. et al. Gender differences in orthostatic hypotension. Am. J. Med. Sci. 342, 221–225 (2011).

Kim, S., Ha, Y. C., Kim, D. Y. & Yoo, J. I. Recent update on the prevalence of sarcopenia in Koreans: findings from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Bone Metab. 31, 150–161 (2024).

Kim, Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiol. Health 30, e2014002 (2014).

Oh, K. et al. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 43, e2021025 (2021).

Freeman, R. et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin. Auton. Res. 21, 69–72 (2011).

Quarracino, C. et al. Prevalence and factors related to orthostatic syndromes in recently diagnosed, drug-naïve patients with Parkinson disease. Clin. Auton. Res. 30, 265–271 (2020).

Park, S. S., Lim, S., Kim, H. & Kim, K. M. Comparison of two DXA systems, Hologic Horizon W and GE Lunar Prodigy, for assessing body composition in healthy Korean adults. Endocrinol. Metab. 36, 1219–1231 (2021).

Dalrymple-Alford, J. C. et al. The MoCA: well-suited screen for cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease. Neurology 75, 1717–1725 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. 2021R1C1C1011822, RS-2021-NR061646 and RS-2023-00208906).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C.: design, execution, analysis, writing first draft of the manuscript. R.K.: design, execution, analysis, review of final version of the manuscript. S.K., J.S.J., K.B., N.K., K.P., J.Y.L. and B.J.: review of final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, S., Kim, R., Kwon, S. et al. Prevalence of low muscle mass and its association with orthostatic hypotension and related symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 12, 41 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01253-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-025-01253-z