Abstract

Physical activity (PA) improves dyspnoea, psychological wellbeing and quality of life (QoL) for people with COPD reducing their risk of exacerbation. However, engagement in PA is low especially amongst those with anxiety and depression, and PA programmes are limited in countries with limited resources such as Brazil. We explored perceptions of 21 people with COPD about the impact of their disease on taking part in community-based PA programmes in Sao Paulo, Brazil through semi-structured telephone interviews from October 2020 to April 2021. Discussions were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analysed using the Framework method. Five themes were identified: Knowledge about COPD and its management; Self-perception of life with COPD; Knowledge and experiences of depression and anxiety; Opinions on PA and repercussions of COVID-19. PA was considered to be important in bringing physical and mental health benefits but there were barriers in accessibility of formal PR programmes and therefore local community PA programmes were considered to be important. People with mental health conditions tended to view PA more negatively. COVID-19 had reduced PA opportunities, access to COPD treatment and social interaction, and was associated with more exacerbations and emotional suffering. In general, this study showed an urgent need to improve knowledge about COPD and its risk factors and management among both patients, the public and primary healthcare professionals. We provide important content for the formulation of public policies for the implementation of specific activity programmes for people with COPD in community spaces using local resources and intersectoral partnerships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the fifth leading cause of death among all ages in Brazil, after ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, lower airway infection, and Alzheimer’s or other dementias and the eighth most important cause of healthy years of life lost (YLL) in 20161,2. Chronic exposure to tobacco is the main cause of the disease, but environmental pollutants such as particles and gases (biomass burning) are also important2. It is currently the fifth leading cause of hospitalisation in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) among patients over 40 years old, corresponding to 200,000 hospitalisations and an annual cost of R$72 million ($14 million)2.

Symptoms arising from progressive airflow limitation, such as dyspnoea, chronic cough with or without sputum production, reduced exercise capacity, muscle strength and quality of life (QoL), defining the daily burden of COPD2,3,4,5. Its evolution is marked by exacerbations, which are responsible for more than 70% of all healthcare costs related to the disease, worsening dyspnoea symptoms, exercise tolerance, functional status, and QoL, leading to clinical deterioration of patients3,4,6.

People with COPD tend to have multiple comorbidities; on average three to four per patient, with osteoporosis, cancer, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, depression, anxiety, and fatigue being the most common3,7,8,9,10,11. It is estimated that 80% of patients with COPD have at least one comorbid chronic condition10. The presence of comorbidities is associated with worse outcomes, such as impaired QoL, increased frequency of hospitalisations, poorer therapeutic response, and even increased morbidity and mortality8,9,10,11. The burden of comorbidities is more substantial in individuals with severe disease7,8,10.

Anxiety and depression are very common in patients with COPD, being more frequent than in the general population or in patients with other chronic diseases. The prevalence of anxiety and depression ranges from 12% to 96% and 27% to 79% respectively, affecting well-being, emotional, social, and physical functioning and are associated with worse outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality, increased disability, and greater health expenses. Furthermore, there is a complex interaction between anxiety and dyspnoea12,13,14. Symptoms of anxiety and depression are often neglected and undertreated12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, and further compounded by their relationship with tobacco smoking, the main cause of COPD.

Whilst stopping smoking improves both COPD outcomes and mental health, physical activity has been shown to be very beneficial22,23, where regular PA is related to reduced risk of hospitalisations and mortality24,25,26,27,28. However, physical inactivity (PI) is common among people with COPD and anxiety and depression interfere further with participation29,30.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a well-established intervention for the management of patients with stable COPD and is considered a standard non-pharmacological recommendation, being a comprehensive intervention, with careful evaluation and adapted therapies, which include physical training, education, and behaviour change31,32. Successful PR reduces symptoms, exacerbations and mortality, promotes economic benefits, improvement in lung function, exercise capacity and QoL and supports family adjustment to the disease12,31,33. The physical activity component is known to be one of the most important elements. However, PR remains highly inaccessible in Brazil and other LMICs due to lack of knowledge of its benefits, lack of referrals, and difficult access, especially to hospitals34. Additionally, barriers to uptake and adherence such as cost and distance to centres are common. Low uptake and adherence are more marked in people with co-existing depression.

Community based PA programmes are therefore an important alternative option, and sometimes the only option, for people who cannot access PR or who need to maintain their activity following PR. There is evidence that social support and adequate training can reduce barriers, resulting in greater participation in PA practice32.

The perception of PA among people with COPD has been studied in high-income countries, but not in Brazil. In this study we aimed to explore the experiences of living with COPD and participation in PA in a sample of people with COPD in an urban setting in Brazil, including participants with anxiety and depression who are the least likely to participate but have the most to gain.

Methods

A qualitative study using semi-structured telephone interviews was conducted between October 2020 and April 2021 with the approval of the ethics committees of the University Center ABC Medical School (CAAE: 24994819.4.0000.0082; Seem n° 4.258.048) and University of Birmingham (ERN_19-1901). All aspects of the qualitative methodology were supervised by specialists in qualitative methods (EM, RA and NG).

Participant sampling and recruitment

Patients eligible for the study included those with established COPD and those with newly diagnosed COPD who were being followed up at primary care centres, known as Basic Health Units (BHU) (BHUs are the primary care centres of the Brazilian National Health Service, Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS)35,36, and/or specialised polyclinics in the city of São Bernardo do Campo, São Paulo, Brazil. Patients with newly diagnosed COPD were recruited from a COPD screening study conducted by the authors29 and invited during assessment visits. Those with established COPD were identified by health professionals during routine appointments at the BHU and invited to participate in this study. Participants were not known to the research team prior to recruitment.

Purposive sampling37 was employed based on the following characteristics: history of anxiety and/or depression, severity of symptoms/illness and recent or established diagnosis of COPD, and a mix of age groups, gender, exercise/activity levels, and educational level.

Following invitation, an eligibility screening questionnaire was administered and for those patients who were included, the researcher (SM) read and explained the informed consent form. Participants were informed that the research contributed to SM’s PhD and was part of a portfolio of studies looking at COPD and primary care. Participants were reassured about the confidentiality and anonymity of their responses. They were told that participation was voluntary, with the freedom to skip questions or withdraw at any time. Patients were excluded if they were unable to give valid informed consent, had moderate/severe cognitive impairment or a diagnosis of asthma. Patients who consented were scheduled for a telephone interview.

Data collection

Patients were interviewed by telephone in their own homes by the principal investigator (SM, female, primary health care (PHC) physician and PhD student), who has extensive experience of treating COPD patients. Data collection was supported by ER (male, sociologist, qualitative researcher, post doc in in Political Economy), with day to day supervision from RA (female nurse with extensive experience of qualitative research involving COPD patients, PhD). NG (female, professor of health policy and sociology and experienced qualitative health researcher, PhD), RJ (female, epidemiologist with a special interest in COPD, PhD) and PAd (female clinical academic public health professor with mixed methods research expertise, MD) oversaw all aspects of data collection and analysis.

Baseline data collected included: sociodemographic questionnaire containing personal information and smoking status, medical records containing information on comorbidities and the results of the spirometry test such as expiratory volume in the first minute (FEV1)3, the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale to measure breathlessness38 and the COPD assessment test (CAT)39 to identify the impact/severity of the disease. In addition, baseline data included: Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) for the assessment, diagnosis and monitoring of depressive disorder (9 questions scored using a 4 point Likert scale, scores range from 0 to 27 with higher scores indicating more severe depression)40,41, a questionnaire for Generalised Anxiety (GAD-7) for assessment, diagnosis, and monitoring of anxiety (7 questions scored using a 4 point Likert scale, scores range from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety)42,43, the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, to assess the frequency and intensity of PA performed in a week44,45, and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) for the detection of minor mental disorders (12 questions, using a 4 point Likert scale, scores range from 0 to 36 with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress)46,47. Answers were recorded and stored in Google spreadsheets, and only the researchers were able to access the individual data48.

Using semi-structured interviews guided by a tested and revised topic guide (see supplement 1) we assessed and explored patients’ knowledge and understanding of COPD, anxiety and depression, PA and their opinions about the practice of some type of PA in the community. Participants were encouraged to share their honest experiences. Additionally, support and contact information for any follow-up questions or concerns were provided. Data collection stopped after 21 interviews when thematic saturation was reached. The interviews lasted approximately 60 min. No repeat interviews were carried out.

A reflective approach was used to increase the rigour of the research49,50. Interviews were audio-recorded, anonymised, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis, and field notes documented. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comments or corrections. All questions were adapted to each participant’s level of literacy, and any doubts about what the interviewee had said were clarified during the interview.

Sample size and analysis

23 patients were invited to participate in this study, of which 2 patients consented to and completed the screening questionnaires, but withdrew from the interview process. No other patients declined to participate. A total of 21 interviews were transcribed clean verbatim by EM. Data were analysed thematically using the Framework method by SM & ER51,52. The Framework method allows for a methodical yet versatile approach suitable for large data sets, novice qualitative researchers and multidisciplinary research teams52. Data were managed in NVvivo 11 (version 12.6.1). Familiarisation with the data was achieved by reading the transcripts several times (by SM) and a draft coding framework developed. To ensure the reliability of the data, coding was discussed between the researchers and the steering group at the University of Birmingham (SM, ER, RJ, PAd, NG, RA). Once a coding framework was agreed (Fig. 1) it was applied to the remaining transcripts (SM & ER). The data were then summarised, themes identified and discussed with the team.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

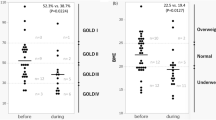

21 participants were interviewed and their baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants’ average age was 67 (ranging from 52 to 85), 11 were female and COPD severity varied. Only 23.8% of the participants performed some type of PA on a regular basis (moderately active)44,45. 16 (76.2%) were experiencing severe psychological distress on the GHQ-12 scale46,47 (scoring > 20) (Table 2). The GHQ-12 anxiety scale (GAD-7)42,43 and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)40,41, used to screen for anxiety and depression revealed higher prevalence of depression than participants’ self-reports of diagnosed depression (Table 2).

Figure 2 visually displays the themes and subthemes generated from the interviews. The following themes and subthemes about the practice of PA were identified:

THEME 1: Knowledge about COPD and its management

This theme shows the participants’ knowledge about the disease, its signs and symptoms, its cause, management, as well as the barriers and facilitators for the adequate care of COPD. Most patients were unaware of the cause of COPD symptoms, attributing them, for example, to age, obesity and sedentary lifestyle and not seeking appropriate health care.

Subtheme 1.1 Information needs and awareness about the disease

The disease was considered unknown until the diagnosis was confirmed, at which time many stressed the surprise that it was at an advanced stage:

“Look, unfortunately I don’t know anything yet, I just know it’s a lung problem…when I found out I was already like this.” P6

Subtheme 1.2 Behaviours contributing to COPD cause

Most of them started using cigarettes in childhood. Those who were still smoking reported difficulties in quitting, feelings of guilt and social stigma in relation to failure to quit smoking, seeing such failure as the result of a “character flaw” and recklessness:

“So all the doctors that I went to, attributed that most of it was the cigarette, of course and I cannot deny that, but it came suddenly, I don’t know why, I had never felt anything at all. I started smoking very early, I started smoking at the age of 14 to 15, so I smoked for 50 years.” P14

Subtheme 1.3 Physicians’ lack of knowledge about the disease

Some participants felt that PHC physicians did not realise that their frequent visits to the service for lung infections could be a sign of COPD:

“A lot of shortness of breath, to the point of having to go to BHU, having to call SAMU [abbreviation for Emergency Mobile Care Service] because I couldn’t stand to walk. So that’s where the doctor didn’t think it was normal, every time I went, I was diagnosed with pneumonia.” P11

Diagnostic confusion with bronchitis and asthma on the part of the physician were reported as a barrier to diagnosis and correct treatment:

“It’s like this, when I went to the doctor, I said, I couldn’t breathe, breathing is everything, they gave me medicine, this is bronchitis, I’ll give you a medicine for bronchitis, ah! this is asthma, and I was given medication for asthma and then I was always in that difficult situation and never got better, right? After a little while, I started using that little salbutamol pump, it's salbutamol, right?” P10

Subtheme 1.4 Case-finding for COPD in primary care and treatment opportunity

Case detection was considered important and beneficial for patients who had participated in the screening study. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients reported that the desire to undergo the examination for lung function/health, was the motivation for participating in the research. They expressed gratitude for the opportunity to access diagnosis and treatment at the BHU:

“I thought it was really good, because if I didn’t do that, I might not even be alive today. I didn’t know anything…I started to treat myself.” P18

Subtheme 1.5 Lack of adequate drug treatment

Free treatment and access to specialised health services were considered fundamental by the participants, but the waiting time for consultations with the specialist and sometimes the delay in delivering medication were seen as a barrier:

I take my medication; I never had a problem taking the medication.” P11

One patient felt that the medication used had no effect and questioned the existence of better therapeutic options:

“Look, all I know is that it makes me very sick, because I can’t breathe properly…I take inhalation, I take Alenia too and it still doesn’t solve it, it’s more difficult for us, if we had another means of having a better medicine that improved more, it would be better, but nobody knows, and I don’t know.” P19

Subtheme 1.6 Impact of smoking on treatment

Those who continue to smoke were aware that smoking worsens their symptoms and that the effect of medications decrease, and the disease worsens:

“It relieves when I pump, it relieves, a little later I smoke, then it all comes back again.” P17

THEME 2 - Self-perception of life with COPD

Participants’ experience of life with COPD and its impact.

Subtheme 2.1 Feelings and expectations about the future and impact on QoL

In the view of the participants, COPD is an incurable disease, however, they showed hope and confidence in the treatment:

“Well, what I know is what the doctor says, that it is a chronic disease, that there is no cure and that I will take these drugs for the rest of my life.” P13

Patients perceive COPD as an extremely limiting disease, which causes profound and negative impacts on their QoL, causing limitations in several areas. The disease has limited the ability to work:

“Look, it caused me a loss that I can no longer clean my house…I was an active person, I was a cleaning lady, I used to clean three times a day, and today I can’t do it anymore, I can’t sweep a house…I can’t walk long distances, depending on the place, the time I’m in, walking indoors also bothers me, because if I’m in a crisis, the shortness of breath is very big, so it totally damages my life, my mobility.” P11

Sex life is an aspect of QoL that can be affected in individuals with COPD because of the respiratory or physical symptoms that accompany it, such as dyspnoea, weakness, fatigue, and reduced PA. One participant showed suffering due to the effect of the disease on his sex life:

“I’ve had this problem [for a while], a sex problem, I can’t do it anymore.” P19

COPD negatively impacted participants’ social lives. Due to the persistence of dyspnoea and fatigue, patients tended to be more limited in their homes, failing to perform their activities due to fear, shame, a sense of loss of personal freedom and independence, often with changes in roles and responsibilities and self-inflicted psychological burden:

“It took away all my freedom…socialising with people. As I must take oxygen everywhere I go, it’s very annoying, it bothers me sometimes, so I stopped going to places I used to go, to the house of a son, a granddaughter, in short, people I know…even before the pandemic, I no longer went to places like that, very rarely, that is, I stopped doing the things I liked.” P14

THEME 3: Opinions on PA practice

This theme portrays the participants’ perception of PA practice and its impact on COPD symptoms and quality of life (QoL):

Subtheme 3.1 Well-being and improvement of respiratory symptoms

The benefits of PA perceived by the participants:

“…above all it’s the well-being that gives you…sometimes you go, suddenly you’re a little upset or you’re a little tired, but you go and then you change, your disposition is different, when you practise PA, the disposition you have is much better, and I think this is one of the biggest benefits, at least for me, it is this, and your disposition changes, you get full power…you start cleaning, you finish cleaning, and you’re still feeling good, you know?…unlike when you don’t do it, you get lethargic, you know, everything makes you tired, so I think your mood improves is…I improve 90% at my disposal.” P2

Subtheme 3.2 The practice of PA and the spaces and modalities used

Participants who performed PA reported using physical spaces in the community (squares, BHU, associations) in addition to their own homes:

“When we don’t do physical activity at the health centre, we do it in the square, we go to the church square” P21

Participants who performed PA used to perform it with an average frequency of 2 times a week:

“I like it and I feel very good every time I do it, the week I do it, I do it twice a week, I do it and I feel good, so, in general,…I do it for half an hour to a few 40 min.” P14

The most frequent modalities were walking, dancing, bodybuilding, using outdoor, communal gym equipment and one patient mentioned gardening:

“The only thing I did was walk.” P1

“A gym class, abdominal, …Zumba class and bodybuilding, it was always in this line right there.” P2 “I do gypsy dance.” P21

“My physical activity is that I am a bricklayer…and I work in my garden, it’s a good thing.” P10

Subtheme 3.3 Community PA programme

In the opinion of the participants, the existence of a PA programme designed for COPD would be very important and all showed interest in participating:

“It would be good, yes. It would be excellent. Oh! I would definitely be the first to sign up to participate.” P12

Subtheme 3.4 Barriers and enablers to the regular practice of PA

Figure 3 visually displays the barriers and enablers for the practice of PA in patients with COPD. Participants reported that living close to the place that offers PA programmes facilitates the practice:

“…whereas if you are going to depend on a car, bus, then it is difficult… the location I think is very important.” P2

Lack of time, dyspnoea, accessibility, climatic conditions, physical comorbidities, and depression were cited as possible barriers to the regular practice of PA:

“If I walk in an open place, wow, I’ll go far, I’ll feel good, now, if I go up a ramp, if it’s a very aggressive ramp, I’ll get tired, you know? …not being able to walk is bad, for example, if I walk and if I get tired, I don’t want to go.” P20

The opinions about depression and PA varied. For some, depression is a deterrent, while for others, exercising leads to an improvement in mood and depressive symptoms:

“I believe that a person with depression will not even have the courage to do any exercise.” P3

“I think when I do exercises, PA, I feel better, right? Only if I’m too upset for me not to go, because I think a depressed person doesn’t want to, right? And this has happened to me, not wanting to go, but it’s very rarely.” P2

Subtheme 3.5 Perceptions about PR

PR was mentioned as a specific PA for COPD by four participants. Three out of four reported their positive perceptions referring to gains on physical and mental health and knowledge for self-management of the disease and one reported that there was no improvement in his clinical condition, probably because he was not using the required medicines.

The following were mentioned as barriers and enablers for carrying out the PR:

Barriers

Distance from PR referral centres and problems with public transport and non-optimised treatment:

“But there are times when he is late, I already think they do it on purpose, I think, I don’t know …we are depending, it’s very annoying, but even so, I accept, because I don’t have no way to pay the ticket, because I did it three times a week, so I wouldn’t be able to pay the ticket, so I accept.” P13

“Then in the evaluation I didn’t have much evolution from what I was, because I was really bad, then they asked me to go to the doctor, then he said it’s better for you to skip this physiotherapy a little and we’ll do it again in the future” P12

Enablers

Physical and mental well-being, improvement of respiratory symptoms and need for oxygen, breath control, feeling of belonging interpersonal interaction, anxiety control, role of the health team in self-care and local structure:

“I like it and I feel very good every time I do it, in the week I do it, which I do twice a week, I do it and I feel good, well, overall…I realised that I have to use a lot more oxygen, if I don’t exercise, that is, things that, if I stop exercising, decrease the intensity, I have to help myself with other things, in this case, oxygen, so I prefer to exercise and dispense a little oxygen.” P14

THEME 4: Knowledge and experiences about depression and anxiety

Subtheme 4.1 Perceptions about the causes and symptoms of depression and impact of QoL

Participants saw both depression and anxiety as conditions that worsen the symptoms of the disease:

“When I get really nervous, yes. Breathing is bad.” P15

“Because we get sad, we lean in a corner, we think bad, then it does affect the shortness of breath…worse.” P12

Only five participants showed knowledge about depression and its symptoms. Disappointments, financial problems, and personal losses have been identified as possible causes of the illness. The most reported symptoms were sadness, anguish, loss of ability to feel pleasure(anhedonia), lack of initiative, irritability, low tolerance, social isolation, difficulties in interpersonal relationships and loss of appetite:

“For me depression is sadness and anguish, lack of will, lack of initiative, lack of desire to relate to other people, to socialise with other people…I have no desire to do nothing, not even the things I have to do here at home…” P8

Some participants reported that depression can impair QoL and reduce interest and/or limit PA:

“…because if the person is depressed, he will not have the courage to do anything…he will be paralysed there in the corner and what he wants is to hide.” P20

THEME 5: Repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily life of people with COPD

This theme portrays the participants’ perception of the impact of the pandemic on their daily lives. The most affected areas in their view were access to PA practice, treatment and services, and health and social life.

Subtheme 5.1 Access to PA practice, treatment, and services

The pandemic negatively impacted access to health services, PR and PA practice:

“Then with the pandemic, there was no more consultation.” P12

“I stopped using gym equipment or hydro because I started this COVID campaign…so I have a sedentary life at home, I cannot go out.” P15

Subtheme 5.2 Impact on social life and mental health

For the participants, social isolation for the prevention of COVID-19 abruptly changed their routines, causing psychological distress, increased anxiety, and depressive symptoms:

“…because today I can’t perform the tasks I used to do, right? And especially now with this pandemic, that to leave the house you must put on a mask, it gets much more complicated for me, right? So I’m practically not leaving the house. Before this pandemic, I would open the door and go out, today I have to do that ritual of alcohol, mask, and not to mention, it is much harder to breathe, so I go from here to the bakery.” P8

Feelings of shame and fear of confusing COPD symptoms with COVID-19 were reported by 2 patients:

“Now with Covid-19, my cough bothers people a lot who keep looking … reluctantly, right?… and they think I have the disease, I imagine …so like this… I feel uncomfortable in public when I start coughing.” P5

Subtheme 5.3 Impact of mask use

Only one participant mentioned the use of a mask as a protective factor for respiratory infections in COPD, while another mentioned worsening of shortness of breath:

“Using the mask is doing me good. It was a barrier. Now I use it almost directly, I do not remove it for anything, because I am very afraid of this disease.” P10

“This whole mask-wearing thing makes me breathless, my goodness, it’s horrible.” P15

Discussion

We found that the participants had little or no knowledge about COPD, its implications, and its management, but there was unanimous recognition of smoking as the main cause of the disease. The initial symptoms of the disease were not recognised, and some considered coughing to be normal for a smoker. Those with newly diagnosed COPD expressed gratitude and relief for being tested at the BHU and undergoing treatment.

The benefits of PA were generally recognised by the participants, although lack of time, dyspnoea, accessibility, climatic conditions, physical comorbidities, and depression were cited as barriers to the regular practice of PA. Although some performed PA using physical spaces in the community (squares, BHU, associations) in addition to their own homes, they were very interested in a PA programme designed for COPD located close by.

Opinions about depression and PA varied. For some, depression was a deterrent, while for others, exercising led to an improvement in mood and depressive symptoms.

Overall, the pandemic negatively impacted access to health services, PR and PA practice. Social isolation abruptly changed their routines, causing psychological distress, increased anxiety, and depressive symptoms. There were also feelings of shame and fear that others would confuse COPD symptoms with COVID-19.

Despite the high prevalence and impact, COPD widely remains an under-recognised disease for patients and health care professionals53,54,55. The slow evolution and the lack of recognition of the symptoms in the beginning make it common for the diagnosis to occur when the disease is in an advanced stage, highlighting the need to raise awareness of the disease and provide training of health professionals and patients to reduce the negative impact of the disease55, and providing some justification for approaches to detect the disease earlier56. Our results may improve healthcare professionals’ understanding of important factors for increasing well-being among people living with COPD.

Participants’ self-perception of life with COPD reveals important insights into how the disease impacts their daily existence, affecting both physical and psychological well-being. These lived experiences underscore the multifaceted challenges faced by individuals with COPD, encompassing not only the physical limitations imposed by the disease but also the emotional and social ramifications. By delving into these personal narratives, this study offers valuable perspectives that can enhance healthcare professionals’ understanding of important factors that influence well-being among people living with COPD. Such insights are essential for developing more effective, holistic care strategies that address the complex needs of this population.

Trust and care centred on the specialist was common to all, suggesting that the PHC was not able to recognise the disease in its early stages. The lack of skills of PHC in dealing with COPD can be changed by adopting a collaborative care model between PHC and secondary care teams, improving the patient’s trajectory in the health network, outcomes, and healthcare utilisation57.

Chronic shortness of breath causes physical limitations and profound restrictions to various aspects of patients’ lives, compromising daily activities, QoL and generating psychosocial disbenefits. According to other studies, many patients adopt a sedentary lifestyle that predictably leads to extensive skeletal muscle deconditioning, social isolation and negative psychological sequelae5, emphasing the multidimensional subjective experience associated with anxiety and suffering16,58. Ongoing shortness of breath causes patients to develop fear and anxiety, leading them to avoid situations that worsen shortness of breath such as PA16,58,59. This cycle will lead to progressive physical deconditioning, and physiological deterioration that results in more dyspnoea and worsening illness59,60. Those with more severe conditions had more negative perceptions of the disease58. The impairment of QoL in patients with COPD is directly related to the increase in the severity of the disease61,62,63,64. Ability to cope with the disease and QoL are interrelated and should be considered in the self-management process64.

Anxiety and depression were seen as conditions that worsen the symptoms. Anxiety was associated with worsening shortness of breath and difficulty in quitting smoking. Anxiety and depression are the result of impaired QoL and inability to perform daily activities, difficulties with personal care and dependence on family3,13,14,16,17,18,64. We found that depression was associated with a lack of interest in daily activities and as a barrier to the practice of PA, corroborating with other studies6,27,64.

All participants considered PA to be very important for well-being and improved QoL, expressing enthusiasm at the prospect of a programme in the community designed for people with COPD. PA was common among participants but those who practised some type of PA reported a perception of well-being and improvement in respiratory symptoms and mood. The most used places for PA practice were squares, BHU and associations, in addition to the home itself. Walking, using gym equipment, weight training, dance, and gardening were the most performed modalities. Shortness of breath, lack of time, bad accessibility, open spaces harmed by weather conditions, the existence of physical comorbidities, lack of motivation, depression and obesity were considered as barriers to the practice of PA. The perception of physical and mental well-being, the improvement of respiratory symptoms, the proximity between home and PA place, group activities and social interaction as enablers. These results were also found in other studies, including a systematic review26,28,64,65, but here we provide specific information for the design of physical activity interventions adapted to our local context in urban areas of Brazil.

Increasing PA can improve disease outcomes as observed in other chronic diseases27,66, thus it is important to detect inactivity in patients20,26,63. Understanding of the health benefits of PA can be increased through information and education strategies64.

Patients who had attended PR valued the bond with health professionals but considered the distance to the place and the cost of public transport as barriers. Community-based PR intervention programmes can improve functional capacity, dyspnoea and QoL in people with COPD and these benefits are comparable to those obtained in PR performed in referral centres31,33,48. Considering the barriers to performing PR in specialised centres, community-based PR can be more accessible, sustainable and cost-effective. However, more studies are needed for stronger conclusions31,33,48.

A strength of our work is the relevance of physical activity and any community intervention specifically researched in an urban area of Brazil, a country of over 203 million people67, of which almost 85% live in a similar urban environment68. However, this research was carried out during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic making it difficult to identify people with COPD in health services due to isolation, with telephone contacts being made, making greater interaction with the participants. The repercussions of COVID-19 emerged as an important topic in the daily lives of people with COPD, findings which were also mentioned in other studies69,70.

In general, this study showed an urgent need to improve knowledge about COPD and its risk factors among both patients, the public and healthcare professionals, and to implement strategies to strengthen supported self-care to proactive coping with the disease. Training health professionals to improve early diagnosis and disease management, and to consider emotional aspects in the global assessment of patients, as such conditions affect disease evolution, adherence to treatment in PA practice, and disease progression. These findings provide important content for the formulation of public policies for the implementation of specific activity programmes for people with COPD in community spaces using local resources and intersectoral partnerships.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request, subject to completion of a data sharing agreement.

References

GBD 2016 Brazil Collaborators. Burden of disease in Brazil, 1990-2016: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 392, 760–775 (2018).

Rabahi, M. Epidemiology of COPD: facing challenges. Pulmão RJ 22, 4–8 (2013).

Christenson, S. A., Smith, B. M., Bafadhel, M. & Putcha, N. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 399, 2227–2242 (2022).

Miravitlles, M. & Ribera, A. Understanding the impact of symptoms on the burden of COPD. Respir. Res. 18, 67 (2017).

O’Donnell, D. E., Milne, K. M., James, M. D., de Torres, J. P. & Neder, J. A. Dyspnea in COPD: new mechanistic insights and management implications. Adv. Ther. 37, 41–60 (2020).

Machado, A. et al. Burtin C. Impact of acute exacerbations of COPD on patients’ health status beyond pulmonary function: a scoping review. Pulmonology 14, S2531–0437 (2022).

Putcha, N., Drummond, M. B., Wise, R. A. & Hansel, N. N. Comorbidities and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, influence on outcomes, and management. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 36, 575–591 (2015).

Laforest, L. et al. Frequency of comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and impact on all-cause mortality: a population-based cohort study. Respir. Med. 117, 33–39 (2016).

Garvey, C. & Criner, G. J. Impact of comorbidities on the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Med. 131, 23–29 (2018).

Kiani, F. Z. & Ahmadi, A. Prevalence of different comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among Shahrekord PERSIAN cohort study in southwest Iran. Sci. Rep. 11, 1548 (2021).

Santos, N. C. D. et al. Prevalence and impact of comorbidities in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 85, 205–220 (2022).

Yohannes, A. M., Kaplan, A. & Hanania, N. A. COPD in primary care: key considerations for optimized management: anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recognition and management. J. Fam. Pract. 67, S11–S18 (2018).

Lima, C. A. et al. Quality of life, anxiety and depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev. Bras Enferm. 73, e20190423 (2020).

YIN, H. L. et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: a meta-analysis. Medicine 96, e6836 (2017).

Pumar, M. I. et al. Anxiety and depression-Important psychological comorbidities of COPD. J. Thorac. Dis. 6, 1615–1631 (2014).

Wang, J., Willis, K., Barson, E. & Smallwood, N. The complexity of mental health care for people with COPD: a qualitative study of clinicians’ perspectives. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 31, 40 (2021).

Martínez-Gestoso, S. et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on the prognosis of copd exacerbations. BMC Pulm. Med. 22, 169 (2022).

Hernandes, N. A. et al. Profile of the level of physical activity in the daily lives of patients with COPD in Brazil. J. Bras Pneumol. 35, 949–956 (2009).

Pitta, F. et al. Comparison of daily physical activity between People with COPD from Central Europe and South America. Respir. Med. 103, 421–426 (2009).

Shin, K. C. Physical activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: clinical impact and risk factors. Korean J. Intern. Med. 33, 75–77 (2018).

Nyssen, S. M. et al. Levels of physical activity and predictors of mortality in COPD. J. Bras Pneumol. 39, 659–666 (2013).

Taylor, G. M. et al. Smoking cessation for improving mental health. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 3, CD013522 (2021).

Action on Smoking and Health [ASH], Royal College of Psychiatrists, Public Mental Health Implementation Centre. Public mental health and smoking. A framework for action. https://ash.org.uk/uploads/Public-mental-health-and-smoking.pdf?v=1659737441 (2022).

Gimeno-Santos, E. et al. Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Thorax 69, 731–739 (2014).

Dueñas-Espín, I. et al. Depression symptoms reduce physical activity in People with COPD: a prospective multicenter study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 1287–1295 (2016).

Xiang, X., Huang, L., Fang, Y., Cai, S. & Zhang, M. Physical activity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a scoping review. BMC Pulm. Med. 22, 301 (2022).

Machado, A., Oliveira, A., Valente, C., Burtin, C. & Marques, A. Effects of a community-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme during acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - A quasi-experimental pilot study. Pulmonology 26, 27–38 (2020).

Spruit, M. A., Pitta, F., McAuley, E., ZuWallack, R. L. & Nici, L. Pulmonary rehabilitation and physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 192, 924–933 (2015).

Strawbridge, W. J., Deleger, S., Roberts, R. E. & Kaplan, G. A. Physical activity reduces the risk of subsequent depression for older adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 156, 328–334 (2002).

Kaczynski, A. T., Manskem, S. R., Mannellm, R. C. & Grewal, K. Smoking and physical activity: a systematic review. Am. J. Health Behav. 32, 93–110 (2008).

Meshe, O. F., Claydon, L. S., Bungay, H. & Andrew, S. The relationship between physical activity and health status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease following pulmonary rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 39, 746–756 (2017).

Marques, A. et al. Improving access to community-based pulmonary rehabilitation: 3R protocol for real-world settings with cost-benefit analysis. BMC Public Health 19, 676 (2019).

Barbosa, M., Andrade, R., de Melo, C. A. & Torres, R. Community-based pulmonary rehabilitation programs in individuals with COPD. Respir. Care 67, 579–593 (2022).

Neves, L. F., Reis, M. H. & Gonçalves, T. R. Home or community-based pulmonary rehabilitation for individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cad. Saude Publica 32, e00085915 (2016).

D’Avila, O. P. et al. Use of health services and family health strategy households population coverage in Brazil. Cienc Saude Colet 26, 3955–3964 (2021).

Martins, S. M. et al. Accuracy and economic evaluation of screening tests for undiagnosed COPD among hypertensive individuals in Brazil. NPJ Prim Care Respir. Med. 32, 55 (2022).

Robinson, R. S. Purposive Sampling. in Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (eds Michalos, A. C.) (Springer, 2014).

Kovelis, D. et al. Validation of the Modified Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire and the Medical Research Council scale for use in Brazilian patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Bras Pneumol. 34, 1008–1018 (2008).

Silva, G. P. F., Morano, M. T. A. P., Viana, C. M. S., Magalhaes, C. B. A. & Pereira, E. D. B. Portuguese-language version of the COPD assessment test: validation for use in Brazil. J. Bras Pneumol. 39, 402–408 (2013).

Santos, I. S. et al. Sensitivity and specificity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) among adults from the general population. Cad Saude Publica 29, 1533–1543 (2013).

Bergerot, C. D., Laros, J. A. & Araujo, T. C. C. F. Avaliação de ansiedade e depressão em pacientes oncológicos: comparação psicométrica. Psico-USF 19, 187–197 (2014).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. & Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1092–1097 (2006).

Jordan, P., Shedden-Mora, M. C. & Löwe, B. Psychometric analysis of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) in primary care using modern item response theory. PLoS ONE 12, e0182162 (2017).

São-João, T. M. et al. Cultural adaptation of the Brazilian version of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity questionnaire. Rev. Saude Publica 47, 479–487 (2013).

Amireault, S., Godin, G., Lacombe, J. & Sabiston, C. M. The use of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire in oncology research: a systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 15, 60 (2015).

Gouveia, V. V., Lima, T. J. S., Gouveia, R. S. V., Freires, L. A. & Barbosa, L. H. G. M. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): the effect of negative items in its factorial structure. Cad Saude Publica 28, 375–384 (2012).

Anjara, S. G., Bonetto, C., Van Bortel, T. & Brayne, C. Using the GHQ-12 to screen for mental health problems among primary care patients: psychometrics and practical considerations. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 14, 1–13 (2020).

Moises, C. Jr Online data collection as adaptation in conducting quantitative and qualitative research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 7, 79–89 (2020).

Baillie, L. Promoting and evaluating scientific rigour in qualitative research. Nurs. Stand. 29, 36–42 (2015).

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D. & Chauvin, S. A review of the quality indicators of Rigor in Qualitative Research. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 84, 7120 (2020).

Smith, J. & Firth, J. Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach. Nurs. Res. 18, 52–62 (2011).

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S. & Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 13, 117 (2013).

de Queiroz, M. C. et al. Knowledge about COPD among users of primary health care services. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon. Dis. 10, 1–6 (2015).

Adeloye, D. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 10, 447–458 (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Disease knowledge and self-management behavior of People with COPD in China. Medicine 98, e14460 (2019).

Enocson, A. et al. Case-finding for COPD in primary care: a qualitative study of patients’ perspectives. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon. Dis. 13, 1623–1632 (2018).

Vachon, B. et al. Challenges and Strategies for Improving COPD Primary Care Services in Quebec: Results of the Experience of the COMPAS+ Quality Improvement Collaborative. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon. Dis. 17, 259–272 (2022).

Kharbanda, S. & Anand, R. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a hospital-based study. Indian J. Med. Res. 153, 459–464 (2021).

Von Leupoldt, A. Treating anxious expectations can improve dyspnoea in patients with COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 50, 1701352 (2017).

Spathis, A. et al. Cutting through complexity: the Breathing, Thinking, Functioning clinical model is an educational tool that facilitates chronic breathlessness management. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 31, 25 (2021).

Tiemensma, J., Gaab, E., Voorhaar, M., Asijee, G. & Kaptein, A. A. Illness perceptions and coping determine quality of life in People with COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 2001–2007 (2016).

Jarab, A., Alefishat, E., Mukattash, T., Alzoubi, K. & Pinto, S. Patients’ perspective of the impact of COPD on quality of life: a focus group study for patients with COPD. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 40, 573–579 (2018).

Zarghami, M., Taghizadeh, F., Sharifpour, A. & Alipour, A. Efficacy of smoking cessation on stress, anxiety, and depression in smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Addict. Health 10, 137 (2018).

Kosteli, M.-C. et al. Barriers and enablers of physical activity engagement for patients with COPD in primary care. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 12, 1019–1031 (2017).

Robinson, H., Williams, V., Curtis, F., Bridle, C. & Jones, A. W. Facilitators and barriers to physical activity following pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a systematic review of qualitative studies. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 28, 19 (2018).

Dogra, S. et al. Physical activity and sedentary time are related to clinically relevant health outcomes among adults with obstructive lung disease. BMC Pulm. Med. 18, 98 (2018).

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo 2022-Panorama https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/panorama/ (2022).

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Sinopse do Censo Demográfico 2010 https://www.ibge.gov.br/censo2010/apps/sinopse/index.php?dados=P9&uf=00 (2011).

Hume, E. et al. Impact of COVID-19 shielding on physical activity and quality of life in patients with COPD. Breathe 16, 200231 (2020).

Yohannes, A. M. People with COPD in a COVID-19 society: depression and anxiety. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 15, 5–7 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) NIHR global group on global COPD in primary care, University of Birmingham, (project reference: (16/137/95)) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The investigator and collaborative team include: R Jordan, P Adab (CIs), SM Martins, AP Dickens, P Adab, A Enocson, BG Cooper, RE Jordan, A Sitch, S Jowett, R Stelmach, R Adams, KK Cheng, C Chi, J Correia-de-Sousa, A Farley, N Gale, K Jolly, M Maglakelidze, T Maghlakelidze, K Stavrikj, AM Turner and S Williams. We thank the International Scientific Advisory Committee (Prof Debbie Jarvis, Dr Semira Manaseki-Holland, Prof David Mannino, Prof Niels Chavannes). We gratefully acknowledge the International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) for introducing us to the primary care networks involved in this study and for its continued facilitation of clinical engagement. We would also like to acknowledge Radmila Ristovska (1955–2020), also involved in the initiation of this study. Finally, we thank the 21 patients who participated in the study and to the Secretary of Health of the Municipality of São Bernardo do Campo for allowing the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.A., R.J., and P.Ad. co-led the study design, with contributions and advice from all other authors. N.G., V.N., and R.S. jointly oversaw all aspects of the study. S.M., V.N., and R.S. contributed to decisions on outcome measures. S.M. advised on involving Basic Health Units. SM coordinated the data collection, with support from A.D., R.J., and P.Ad.. S.M. and E.R. conducted the qualitative analysis, supported by R.A.. S.M., V.N., E.M., R.J., and R.A. wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors. Reflecting the UK-Brazil collaboration, S.M. was the local PI and oversaw all activities in Brazil. R.J., R.A., P.Ad., and R.S. are joint senior authors. As part of the Breathe Well Global Health Research Group, all authors contributed to the development and oversight of this study. All authors contributed to and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.Ad. declares grant funding paid to her institution from NIHR, MRC and Colt Foundation, funding to Institution and to cover expenses as Chair of NIHR Public Health Research Funding Committee, Deputy Director of NIHR School for Public Health Research, funding to cover expense as Member of Wellcome Trust Early Career Advisory Group in Population and Public Health, Output Assessor for Panel A, subpanel 2 in 2021 Research Excellence Framework, and unfunded contributions as Chair for several NIHR funded TSCs, Member of the MRC funded Natural Experiments Evaluations Project Oversight Group, Member of Obesity Health Alliance Independent Obesity Strategy Working Group, Member of NIHR palliative and End of Life Care Research Partnerships call Panel, NIHR/UKRI Long COVID funding call Panel, NIHR COVID-19 Recovery and Learning Funding Committee; J.C-De-S. declares grant funding to his institution from AstraZeneca and GSK, advisory board and consulting fees paid to himself from Boheringer Ingelheim, GSK, AstraZeneca, Bial, Medinfar, Payment for lectures from GSK, AstraZeneca and Sanofi Pasteur, support for attending meetings from Mundipharma and Mylan, leadership role for International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG); A Farley declares grant funding paid to her institution from NIHR GHR for the present manuscript, grant funding from NIHR HTA, NIHR EME, MRC and Ethicon (Johnson and Johnson) for other work, membership on DMEC for NIHR funded e-cigarette trial (no honorarium), leadership role for International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) and as expert funding panel member for Cancer Research UK personal funding for; K.J. declares grant funding paid to her institution from NIHR and MRC, participant in Data Safety Monitoring Board or advisory board for NIHR funded studies (no honorarium), Sub-committee chair of NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Health Research (payments to institution); R.J. declares grant funding to her institution from NIHR, membership of Boehringer Ingelheim Primary Care Advisory Board, unfunded leadership role for International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) – research sub-committee, membership of NIHR Global Health Group panel and RfPB COPD Highlight panel; S.J. declares grant funding to her institution from NIHR GHR for present manuscript and unfunded membership of the HTA Funding Committee Policy Group (formerly CSG) and the HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Committee; S.M.M. declares leadership or fiduciary do GEPRAPS (Respiratory Group of Study and Research in Primary Care) of Center for Public Health Studies (CESCO) at the University Center of the ABC Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil, IPCRG (Internacional Primary Care Respiratory Group); A Sitch declares grant funding to her institution from NIHR GHR for present manuscript, NIHR Birmingham BRC and AstraZeneca; A Turner declares grant funding to her institution from NIHR GHR for present manuscript, grant funding from AstraZeneca and Chiesi for other work, payment of honoraria from GSK and Boehringer, support for attending meetings and/or travel from AstraZeneca and Chiesi; S.W. declares grants from the University of Birmingham paid to her institution, her institution has received conference sponsorship and independent educational grants from Pfizer Global Medical Grants, AstraZeneca, GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, Vitalograph, Caire Diagnostics and Thorasys; R.A., K.K.C., C.Chi., B.C., A.D., A.E., N.G., T.M., M.M., K.S., S.R. declare grant funding to their institution from NIHR GHR for current manuscript; V.B.N., E.R. have no financial or non-financial conflicts to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martins, S.M., Adams, R., Rodrigues, E.M. et al. Living with COPD and its psychological effects on participating in community-based physical activity in Brazil: a qualitative study. Findings from the Breathe Well group. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 34, 33 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-024-00386-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-024-00386-7