Abstract

The relationship between systemic inflammation and centripedal obesity in predicting mortality risk among patients with Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRISm) has garnered increasing interest. This study aims to elucidate the joint effects of these factors on mortality risk in this patient population. This study included data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of U.S. adults collected from 2007–2012, calculating both the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) and the weight-adjusted waist index (WWI). Lung function parameters were used to define PRISm cases. Generalized linear models and logistic regression were used to assess the individual and combined effects of SIRI and WWI, and further explored the mediating role of the SIRI. A total of 1454 PRISm patients were included in this study, with a median follow-up period of 9.5 years, during which 10.9% died from all causes and 3.6% from cardiovascular diseases. The restricted cubic spline curves for SIRI and WWI showed J-shaped associations with mortality. Participants with both high WWI (≥11.18) and high Ln SIRI (≥0.13) had significantly higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality compared with those with low WWI and low SIRI. In the discordant groups, high WWI with low SIRI was associated with increased all-cause mortality (HR = 1.795, 1.050–3.064), while low WWI with high SIRI was linked to higher cardiovascular mortality (HR = 4.844, 1.505–15.591). This effect was more pronounced in the smoking subgroup. Additionally, SIRI mediated 9% of the association between WWI and all-cause mortality, and 12.94% of the association with cardiovascular mortality. Our study provides evidence for the relationship between SIRI and WWI with mortality in PRISm patients. The joint association of these factors provide potential insights for additional information for prognostic prediction and may contribute to identifying risk stratification in PRISm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

PRISm (Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry) represents a unique respiratory phenotype characterized by reduced forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁) but preserved FEV₁ to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio1,2. PRISm is prevalent among middle-aged and elderly populations, with an estimated incidence ranging from 4.7–25.2%3. While PRISm has not yet reached the threshold for diagnosing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), it represents a distinct group of individuals who exhibit early-stage functional abnormalities in the lungs. PRISm is a heterogeneous condition, with some individuals showing stable lung function over time, while others progress to full-blown COPD and even experience mortality4,5. This variability has generated significant debate in the literature, as PRISm encompasses individuals at different stages of disease progression.

Emerging evidence indicates that respiratory mortality is markedly higher in PRISm patients than in those with normal spirometry, with nearly a two-fold increased risk (adjusted HR 1.95–1.97) and more frequent respiratory events, including hospitalizations. This elevated risk contributes substantially to overall all-cause and cardiovascular mortality and remains significant across populations, even in cases of mild lung function impairment6,7,8. The identification of such high-risk individuals is crucial for effective management, as it offers an opportunity for early intervention before irreversible damage occurs. As the prevalence of PRISm continues to grow, particularly among aging populations, it is essential to further explore the underlying pathophysiology of this condition and identify the specific biomarkers or clinical characteristics that can help predict the progression to disease and the risk of cardiovascular events7. Moreover, stratifying high-risk populations in PRISm could help in both economic and clinical terms, providing a cost-effective strategy to prevent future exacerbations, hospitalizations, and ultimately, mortality9,10.

In this context, biomarkers such as the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) and the weight-adjusted waist index (WWI) have gained prominence as potential predictors of disease outcomes. SIRI is a novel composite marker that integrates three independent subtypes of white blood cells. Initially, SIRI was used to assess tumor prognosis11. However, recent studies have shown that elevated SIRI is closely associated with poor outcomes in acute coronary syndrome, cardiovascular mortality, arrhythmias in stroke patients, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)12,13,14. WWI, a metric of central obesity and body composition, have demonstrated significant roles in various chronic diseases, including asthma, cardiovascular disorders and metabolic syndrome15,16,17. Their potential relevance in PRISm is particularly intriguing, as systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation are likely contributors to the observed mortality risks. However, the specific contributions of SIRI and WWI to the mortality risks associated with PRISm disease remain unexplored, necessitating further investigation.

Understanding the mechanisms through which SIRI and WWI influence all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in PRISm disease is essential for developing effective preventive strategies. Unraveling these pathways could provide valuable insights into targeted interventions that address systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, thereby reducing the burden of mortality in this population. By pinpointing these high-risk groups within the PRISm population, we can not only improve early diagnosis but also design targeted interventions to reduce the burden of disease and improve long-term outcomes.

Materials and methods

Data source

This study analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). NHANES uses a stratified, multi-stage sampling method to collect health and nutrition data from a representative U.S. civilian population. The study protocol was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (ERB), and participants provided written informed consent. As this secondary analysis used de-identified, publicly available data, no additional ethical approval or consent was required. Further details are available on the NHANES website. This study utilized three NHANES data waves—2007–2008, 2009–2010, and 2011–2012—selected for their inclusion of spirometry measurements.

Study population

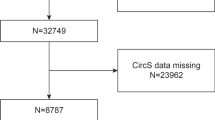

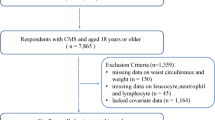

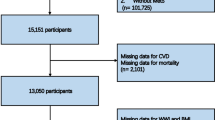

Preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) was defined as an FEV1/FVC ratio ≥0.70 in the presence of abnormal spirometry, indicated by an FEV1 < 80% predicted18. The prevalence of PRISm was estimated in U.S. adults aged 20–79 who were eligible for spirometry testing19. The age range was determined based on Hankinson’s predictive equation for lung function, which applies to males starting at age 20 and females at age 1820, with an upper limit of 79, reflecting the maximum eligible age for NHANES spirometry. Of the 1903 participants, 222 were excluded because they were pregnant (n = 17), lost to follow-up (n = 3), had missing SII measurements (n = 139), or missing WWI measurements (n = 63). Finally, 1681 individuals were included in the analysis. In addition, due to missing data on Marital status (n = 1), education (n = 1), drinking (n = 102) and PIR (n = 148), SII and WWI analyses were available for 1454, (Fig. 1).

Measurement of WWI and SIRI

WWI (Waist-to-Weight Index) is an obesity measurement method that combines waist circumference (WC) and weight. Higher WWI values correspond to greater levels of obesity. Certified health technicians measured participants’ weight and WC in a mobile examination center (MEC). WWI was calculated by taking the square root of waist circumference (cm) and dividing it by weight (kg). For analysis, participants were categorized into tertiles based on their WWI, which was also analyzed as a continuous variable. In this study, WWI was considered the primary exposure factor. SIRI was calculated using the formula: (neutrophil count × monocyte count) / lymphocyte count. To address the right-skewed distribution of these inflammatory markers, SIRI was log2-transformed prior to performing regression analyses21,22,23.

Ascertainment of mortality

Mortality data were obtained from the NHANES mortality dataset, updated through December 31, 2019. Causes of death were classified using ICD-10 codes, with cardiovascular disease mortality (e.g., ischemic heart disease, stroke, and heart failure) identified under codes I00–I09, I11, I13, I20–I51, and I60–I69.)

Assessment of covariates

This study included variables related to dental health: age, sex, race, marital status, education, poverty index ratio (PIR), BMI, diabetes, hypertension, drinking, smoking, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Diabetes was diagnosed based on doctor diagnosis, HbA1c > 6.5%, fasting blood sugar >7.0 mmol/L, random blood sugar ≥11.1 mmol/L, 2-h OGTT ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or use of diabetes medication. Hypertension was determined by doctor diagnosis, antihypertensive use, or abnormal blood pressure. Physical activity was classified as vigorous, moderate, or none based on NHANES questionnaire responses. Other variables were sourced from NHANES data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis followed NHANES design guidelines, using appropriate sampling weights. Baseline differences were analyzed with weighted t-tests for continuous variables and weighted χ2 tests for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier analysis explored the association between SIRI, SII, WWI levels, and all-cause and CVD mortality in PRISm patients. Cox Proportional Hazards models, adjusted for covariates, assessed the impact of exposure levels on mortality, presenting results as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis evaluated nonlinear relationships, with inflection points determined when applicable. While RCS does not directly provide cut-off values, it enables visualization of dose–response patterns and identification of potential inflection points where risk begins to change significantly. To formally determine these threshold values, we combined RCS findings with a recursive algorithm for piecewise regression. Missing covariate data were handled by deletion. All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.3.2, with significance set at P < 0.05.)

Results

Baseline characteristics of study participants

The baseline characteristics of participants grouped by tertiles of the SIRI index are depicted in Table 1. Among the 1454 participants, with each tertile based on 485 individual observations. 46.2% were male, with an average age of 47 ± 0.6 years. Diabetes was reported in 427(27.05%) individuals. Compared to those in the lower tertiles, participants in the higher tertiles were generally older, more likely to be female, had lower educational levels, were more likely to have hypertension, and had fewer cases of cardiovascular disease. Participants in the higher SIRI tertiles had increased weight, waist circumference, lymphocyte counts, and neutrophil counts, but lower FEV1 and FVC compared to those in the lower tertiles. The baseline characteristics of participants stratified by tertiles of the WWI index are shown in Table S1.

Associations between SIRI and WWI with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the PRISm population

Three models were developed to assess the independent functionality of SIRI and WWI in relation to mortality (Table 2). In the Crude Model, no covariates were adjusted. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, race, PIR, marital status, and educational level. Model 2 further adjusted for smoking, drinking, diabetes, hypertension, physical activity, and CVD. The Cox regression results indicate that higher SIRI and WWI levels are associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (T3 vs. T1). Participants in the third tertile of SIRI had a 1.41-fold increase in cardiovascular mortality risk and a 2.83-fold increase in all-cause mortality risk compared to those in the first tertile.

During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, 11.4% of the 1454 participants died, with 3.3% of deaths attributed to cardiovascular disease. The Kaplan–Meier curves confirm this trend as mentioned above, showing that participants with higher SIRI and WWI scores had significantly lower survival rates compared to those with lower scores in the PRISm population (log-rank P for trend < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). Restricted cubic spline analyses demonstrated a J-shaped association between the SIRI index and mortality in individuals with PRISm, with a significant increase in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality observed when the SIRI index exceeded 0.13. Interstingly, for WWI, a linear relationship was observed with both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (non-linear p = 0.121 and p = 0.117, respectively). As WWI increased, the hazard ratio (HR) rose correspondingly, surpassing 1.0 when WWI exceeded the threshold of 11.18 (Fig. 3).

Association between the combination of the SIRI index and WWI and mortality in individuals with PRISm

Previous analyses revealed that both SIRI and WWI influence all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in PRISm populations. However, the combined effect of these indices and the extent to which each dominates require further clarification. To address this, we performed additional analyses using the inflection points identified through RCS analysis as grouping thresholds. When participants were stratified into four groups according to combinations of WWI and SIRI, clear differences in mortality risk were observed. The reference group was defined as individuals with both low WWI and low SIRI. The results indicate that individuals in the high SIRI and high WWI group (SIRI > 0.13 and WWI > 11.18) showed the highest risk of all-cause mortality (mortality rate: 17.8 vs. 5.3%; HR = 2.784, 95% CI 1.584–4.892) and cardiovascular mortality (mortality rate: 5.8 vs. 0.6%; HR = 6.991, 95% CI 2.615–18.687) compared with individuals in the low SIRI and low WWI group (SIRI < 0.13and WWI < 11.18) (Fig. 4). To be specific, higher LnWWI poses a greater risk for all-cause mortality compared to higher LnSIRI, whereas higher LnSIRI shows a more significant association with CVD mortality compared to higher LnWWI (Fig. 4, Table S2).

Subgroup analysis of the association between the combination of the SIRI index and WWI index and mortality

For all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, consistent results were observed across subgroups stratified by gender, FVC% (<80% vs. ≥80%), and diabetes history. Interaction tests revealed that Ln SIRI > 0.13 and WWI > 11.18 significantly increased the risk of all-cause mortality, particularly among individuals with a history of smoking. For cardiovascular mortality, the effect of Ln SIRI > 0.13 and WWI > 11.18 was more pronounced in individuals aged >60 years and those who smoked (P for interaction < 0.05; Table S3).

Mediation effects of SIRI on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

Given the significant intercorrelations observed between the WWI, SIRI and the risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, additional mediation analyses were conducted to better understand the underlying mechanisms of these associations (Fig. 5). These analyses revealed that SIRI plays a mediating role, accounting for 9.08% of the association between WWI and all-cause mortality (Fig. 5A) and 12.98% of the association between WWI and cardiovascular mortality (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

This study comprehensively analyzed the associations of WWI and SIRI with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the PRISm population using multiple analytical approaches. By examining data from 1456 PRISm patients in the NHANES dataset, we found that both elevated WWI and SIRI were significantly associated with increased risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. These associations remained robust even after adjusting for potential confounders. Moreover, our findings highlighted a synergistic effect between WWI and SIRI, with their combined elevation further amplifying mortality risks. The combination of Ln SIRI ≥ 0.13 and WWI ≥ 11.18 can effectively identify individuals at the highest risk of mortality in the Prism population. Mediation analysis further demonstrated that SIRI acts as a mediator in the relationship between WWI and mortality, emphasizing the pivotal role of systemic inflammation in linking central obesity to adverse health outcomes.

Previous studies have explored the relationship between inflammation and mortality within the respiratory system, particularly in chronic airway diseases such as COPD and asthma3,24. Inflammation is widely recognized as a key driver of disease progression and is associated with poorer outcomes, including increased mortality25. Inflammatory biomarkers from complete blood counts, such as elevated NLR and PLR correlate with higher mortality, worse prognosis, and exacerbation frequency, while higher Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) predicts poorer outcomes in older patients26,27. Although studies have shown that PRISm, despite being an early-stage condition, is associated with a relatively high mortality risk, many specific risk factors contributing to this outcome remain unknown.

In our study, we observed that high levels of the SIRI were strongly associated with increased mortality risk, consistent with previous findings linking inflammation to poor outcomes in chronic respiratory conditions28,29. However, SII did not show a similar association (Table S4), suggesting that SIRI may be a more sensitive marker of systemic inflammation. SIRI, which includes neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts, reflects the interplay between innate and adaptive immunity, potentially offering a more accurate picture of inflammation driving disease progression30,31. In contrast, SII, which incorporates platelets, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, may not capture the specific inflammatory pathways contributing to mortality in this cohort. Additionally, we observed a J-shaped relationship between SIRI and all-cause mortality (P for nonlinearity < 0.0001), where both low and high SIRI levels were associated with increased risk. High SIRI reflects chronic inflammation and immune exhaustion, while low SIRI may indicate immunodeficiency or immunoparalysis, often seen in frail or chronically ill individuals. These findings highlight the importance of immune balance, with very low SIRI potentially signaling vulnerability rather than a favorable inflammatory status.

We also examined the association between WWI and mortality in the PRISm cohort. WWI, a relatively recent metric, has been gaining attention for its ability to provide a more accurate assessment of body composition compared to traditional indices such as Body Mass Index (BMI). Recent studies have highlighted the utility of WWI, particularly in the context of chronic respiratory diseases, due to its ability to better reflect central obesity and fat distribution, which are critical factors influencing health outcomes32. In our study, we targeted a PRISm cohort defined by pulmonary function parameters, and as pulmonary function is significantly correlated with height, the use of WWI helped mitigate potential confounding effects associated with height, which is often a limitation when using BMI. More importantly, we also performed restricted cubic spline analyses of BMI in relation to mortality among PRISm patients, and the results did not demonstrate a consistent positive association, further underscoring the added value of WWI in this population (Figure S1).

Furthermore, the relationship between WWI and inflammation has been of particular interest in recent research33. Central obesity, as reflected by WWI, is associated with elevated systemic inflammation, which is a known contributor to both respiratory diseases and mortality34. In our work, we examined the potential synergistic effect of WWI and SIRI on mortality risk. The combined impact was particularly pronounced, with the high WWI–high SIRI group representing a markedly elevated-risk subgroup compared with the low WWI–low SIRI group. Interestingly, the results showed that, for all-cause mortality, the effect of WWI was stronger than that of SIRI, whereas in cardiovascular mortality, SIRI had a greater effect than WWI. Mechanistically, mortality risk reflects distinct but complementary pathways: low SIRI with high WWI drives all-cause mortality mainly via adipose tissue dysfunction, insulin resistance, and local inflammation, thereby increasing the risk of all-cause mortality, including but not limited to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer35,36. Conversely, in individuals with high SIRI and low WWI, heightened systemic inflammation represents a key driver, destabilizing atherosclerotic plaques and promoting cardiovascular events, which significantly elevates cardiovascular mortality risk37,38. These findings emphasize the value of jointly assessing WWI and SIRI for risk stratification, identifying PRISm individuals at particularly high risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. This approach may inform early intervention strategies—such as closer monitoring, regular follow-up, and proactive management of metabolic and inflammatory risks—supporting more personalized care to improve outcomes.

We further examined the effects of WWI and SIRI on mortality through subgroup analyses. These analyses, stratified by sex, diabetes status, and FVC% (<80 vs. ≥80%), revealed no significant interaction between WWI combined with SIRI and mortality risk across these subgroups. This indicates that, after adjusting for confounders, the association between high WWI combined with elevated SIRI levels and mortality remains robust and consistent, regardless of sex, diabetes status and lung function. Interestingly, when analyzing mortality, significant interactions were observed with smoking status, with interaction p-values of 0.045 and 0.038, respectively. This highlights the amplified effect of smoking on the relationship between WWI, SIRI, and CVD mortality.

Additionally, age was found to independently affect the combined impact of WWI and SIRI levels on CVD mortality. Specifically, individuals under 60 years of age with both high WWI and high SIRI levels exhibited a higher mortality risk. Although previous research has indicated that COPD prevalence increases with age, this pattern did not hold for PRISm, where the highest prevalence was observed in individuals aged 40–6439. Other studies in the US have similarly reported a higher prevalence of PRISm among subjects aged 49–6340. Individuals with PRISm in middle age may transition to COPD before reaching 65, thereby “diluting” the prevalence of PRISm in older age groups as FEV1 and FVC decline at different rates8. Alternatively, individuals with PRISm may experience higher mortality rates at younger ages due to the increased mortality risk associated with PRISm. Therefore, it is crucial to pay heightened attention to the PRISm population under 60 years old, recognizing their elevated risk and the need for targeted interventions.

Although there is a well-recognized connection between WWI and inflammation, the intricate relationship between the two in the PRISm population requires further exploration. Our study confirmed that SIRI acts as a mediator in the relationship between WWI and mortality, shedding light on a potential mechanism underlying these associations. The mediation role of SIRI suggests that the pro-inflammatory state associated with central obesity could be a critical driver of the adverse outcomes observed in PRISm patients. Adipose tissue in individuals with high WWI is known to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which contribute to systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction41,42. This inflammatory cascade can promote cardiovascular events and exacerbate existing respiratory pathologies, leading to higher mortality. Furthermore, PRISm patients often exhibit impaired pulmonary function and heightened susceptibility to inflammatory insults43. The interplay between chronic inflammation and impaired lung function may amplify the deleterious effects of obesity, creating a feedback loop that accelerates disease progression and mortality risk. Future studies are needed to further unravel the complex biological pathways linking WWI, SIRI, and mortality, which could inform the development of more effective interventions and risk stratification strategies in PRISm patients.

Certainly, there are still several limitations in our study. First, the observational design of our study limits the ability to establish causal relationships. The impact of WWI and SIRI on mortality requires confirmation through future randomized clinical trials. Second, we were unable to assess the prognostic impact of dynamic changes in the SIRI index and WWI. Third, our study population was derived exclusively from the United States, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other regions. Notably, additional data are urgently needed, particularly from Chinese populations, to deepen the understanding of PRISm and its implications for this unique group.

Conclussion

Our study demonstrates that both WWI and SIRI are independently associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, and their combined assessment further amplifies this risk. SIRI also partially mediates the effect of WWI on mortality. These findings highlight the potential utility of jointly evaluating WWI and SIRI as a practical and accessible approach for risk stratification in patients with PRISm.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Wan, E. S. et al. Epidemiology, genetics, and subtyping of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm) in COPDGene. Respir. Res. 15, 89 (2014).

Wan, E. S. The clinical spectrum of PRISm. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206, 524–525 (2022).

Wijnant, S. R. A. et al. Trajectory and mortality of preserved ratio impaired spirometry: the rotterdam study. Eur. Respir. J. 55, 1901217 (2020).

Washio, Y. et al. Risks of mortality and airflow limitation in Japanese Individuals with preserved ratio impaired spirometry. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206, 563–572 (2022).

Krishnan, S. et al. Impaired spirometry and COPD increase the risk of cardiovascular disease: a Canadian Cohort study. Chest 164, 637–649 (2023).

Li, M. et al. Association of preserved ratio impaired spirometry with mortality and cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 13, 171 (2024).

Zheng, J. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in relationship to cardiovascular outcomes: a large prospective cohort study. Chest 163, 610–623 (2023).

Wan, E. S. et al. Association between preserved ratio impaired spirometry and clinical outcomes in US adults. JAMA 326, 2287–2298 (2021).

Wan, E. S. et al. Significant spirometric transitions and preserved ratio impaired spirometry among ever smokers. Chest 161, 651–661 (2022).

Marott, J. L. et al. Impact of the metabolic syndrome on cardiopulmonary morbidity and mortality in individuals with lung function impairment: a prospective cohort study of the Danish general population. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 35, 100759 (2023).

Cao, Y. et al. Levels of systemic inflammation response index are correlated with tumor-associated bacteria in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 14, 69 (2023).

Xiao, S. et al. Association of systemic immune inflammation index with all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer-related mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 941–961 (2023).

Adamo, L., Rocha-Resende, C., Prabhu, S. D. & Mann, D. L. Reappraising the role of inflammation in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 269–285 (2020).

Lin, K., Lan, Y., Wang, A., Yan, Y. & Ge, J. The association between a novel inflammatory biomarker, systemic inflammatory response index and the risk of diabetic cardiovascular complications. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 33, 1389–1397 (2023).

Jiang, D., Wang, L., Bai, C. & Chen, O. Association between abdominal obesity and asthma: a meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 15, 16 (2019).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Associations between weight-adjusted waist index and abdominal fat and muscle mass: multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Diabetes Metab. J. 46, 747–755 (2022).

Han, X. et al. The association of asthma duration with body mass index and weight-adjusted-waist index in a nationwide study of the U.S. adults. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28, 122 (2023).

Schwartz, A. et al. Preserved ratio impaired spirometry in a spirometry database. Respir. Care 66, 58–65 (2021).

Cooper, B. G. et al. The Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) network: bringing the world’s respiratory reference values together. Breathe 13, e56–e64 (2017).

Hankinson, J. L., Odencrantz, J. R. & Fedan, K. B. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159, 179–187 (1999).

Feng, C. et al. Log-transformation and its implications for data analysis. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 26, 105–109 (2014).

Curran-Everett, D. Explorations in statistics: the log transformation. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 42, 343–347 (2018).

Liu, B., Wang, J., Li, Y. Y., Li, K. P. & Zhang, Q. The association between systemic immune-inflammation index and rheumatoid arthritis: evidence from NHANES 1999-2018. Arthritis Res. Ther. 25, 34 (2023).

Wan, E. S. et al. Longitudinal phenotypes and mortality in preserved ratio impaired spirometry in the COPDGene study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 198, 1397–1405 (2018).

Huang, P., Mai, Y., Zhao, J., Yi, Y. & Wen, Y. Association of systemic immune-inflammation index and systemic inflammation response index with chronic kidney disease: observational study of 40,937 adults. Inflamm. Res. 73, 655–667 (2024).

Wang, R. H. et al. The clinical value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the occurrence and severity of pneumonia in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Immunol. 14, 1115031 (2023).

Ke, J., Qiu, F., Fan, W. & Wei, S. Associations of complete blood cell count-derived inflammatory biomarkers with asthma and mortality in adults: a population-based study. Front. Immunol. 14, 1205687 (2023).

Xu, F. et al. Association between the systemic inflammation response index and mortality in the asthma population. Front. Med. 11, 1446364 (2024).

Gao, H., Cheng, X., Zuo, X. & Huang, Z. Exploring the impact of adequate energy supply on nutrition, immunity, and inflammation in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 19, 1391–1402 (2024).

Balk, R. A. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): where did it come from and is it still relevant today?. Virulence 5, 20–26 (2014).

Kaukonen, K. M., Bailey, M., Pilcher, D., Cooper, D. J. & Bellomo, R. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 1629–1638 (2015).

Kim, N. H., Park, Y., Kim, N. H. & Kim, S. G. Weight-adjusted waist index reflects fat and muscle mass in the opposite direction in older adults. Age Ageing 50, 780–786 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Weight-adjusted waist index as a practical predictor for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and non-accidental mortality risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 34, 2498–2510 (2024).

Zhang, T. Y. et al. Relationship between weight-adjusted-waist index and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 26, 5621–5629 (2024).

Park, M. J. et al. A novel anthropometric parameter, weight-adjusted waist index represents sarcopenic obesity in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32, 130–140 (2023).

Kuchay, M. S., Martinez-Montoro, J. I., Kaur, P., Fernandez-Garcia, J. C. & Ramos-Molina, B. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related fibrosis and sarcopenia: an altered liver-muscle crosstalk leading to increased mortality risk. Ageing Res. Rev. 80, 101696 (2022).

Zhu, D. et al. The associations of two novel inflammation biomarkers, SIRI and SII, with mortality risk in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Inflamm. Res. 17, 1255–1264 (2024).

Song, B. et al. Inflammatory factors driving atherosclerotic plaque progression new insights. J. Transl. Int. Med. 10, 36–47 (2022).

Cadham, C. J. et al. The prevalence and mortality risks of PRISm and COPD in the United States from NHANES 2007–2012. Respir. Res. 25, 208 (2024).

Higbee, D. H. et al. Genome-wide association study of preserved ratio impaired spirometry (PRISm). Eur. Respir. J. 63, 2300337 (2024).

Aromolaran, K. A., Corbin, A. & Aromolaran, A. S. Obesity arrhythmias: role of IL-6 trans-signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 8407 (2024).

Luan, D. et al. Adipocyte-secreted IL-6 sensitizes macrophages to IL-4 signaling. Diabetes 72, 367–374 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. Associations of dietary inflammation index and composite dietary antioxidant index with preserved ratio impaired spirometry in US adults and the mediating roles of triglyceride-glucose index: NHANES 2007–2012. Redox Biol. 76, 103334 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The China International Medical Foundation-Practical Research Project on Respiratory Diseases (Z-2017-24-2301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuning Huang and Min Zhang wrote the main manuscript text and Xue Zhang, Hui Zhu prepared figures 1-5 and Tables. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Zhu, H. et al. The joint association between inflammation and centripedal obesity with mortality risk in patients with preserved ratio impaired spirometry. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 50 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00453-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00453-7