Abstract

Objective

This study explored the application of Machine Learning (ML) techniques to cluster patients with suspected sleep apnea (SA), based on clinical-demographic data, with the aim of optimizing diagnostic pathways and enabling more personalized management.

Methods

A cohort of 5385 patients referred for suspected SA to a Sleep-Disordered Breathing Unit in northwest Spain was analyzed. Demographic, anthropometric, comorbidity, and symptom data were collected. Patients were grouped using the k-prototypes algorithm, with the elbow method determining the optimal number of clusters. These clusters were then correlated with cardiorespiratory polygraphy outcomes and continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) prescription rates. Finally, we developed an Intelligent Clinical Decision Support System (ICDSS) based on Random Forest to assign new patients to clusters using a reduced set of variables.

Results

Five distinct clusters were identified: one of middle-aged men with low symptom burden; a cluster predominantly comprising symptomatic women with high use of psychotropic drugs; a group mainly of young men with severe daytime sleepiness; a cluster of middle-aged men with moderate symptoms; and a group of older men with high comorbidity yet low subjective symptomatology. Significant differences in apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) distributions and CPAP indications were observed among these clusters. The integration of polygraphic findings, CPAP prescription rates, and the distinct clinical features of each cluster supports the formulation of tailored diagnostic and therapeutic strategies according to the specific clinical profile of each subgroup. Using the ICDSS, we accurately assigned patients to their respective clusters based solely on clinical variables, achieving area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values ranging from 0.87 to 0.95, reliably guiding precise diagnostic and therapeutic management.

Conclusions

ML techniques applied to routine data allow the identification of meaningful clinical clusters in patients with suspected SA. These clusters can guide differential diagnostic testing and personalized treatment strategies. The ICDSS enables early and accurate patient classification, supporting a precision medicine approach in sleep medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep apnea (SA) is an increasingly common condition in hospital consultations, not only due to its high prevalence1, but also because of its impact on public health2. This has led to a progressive increase in consultation demand, generating long waiting lists3. Although the severity of SA has traditionally been classified using the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI; <5 events/h no SA, 5–14.9 events/h mild, 15–29.9 events/h moderate, ≥30 events/h severe)4, this metric presents significant limitations as it fails to capture the clinical heterogeneity of the disease. Patients with similar AHI values often exhibit different clinical profiles, ranging from snorers with excessive daytime sleepiness to asymptomatic individuals with hypertension or cardiovascular conditions5.

The heterogeneous and complex nature of SA is influenced by a variety of risk factors, pathophysiological mechanisms6, diverse symptoms, and a strong association with multiple comorbidities7 and mortality8. Despite this complexity, the diagnosis and treatment of SA still largely depend on the AHI, while continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) remains the standard therapy for most patients9. This generalized approach, although effective, fails to address the specific characteristics of different patient subgroups, thereby limiting the potential for personalized treatments.

In recent years, new strategies have been explored to better characterize SA patients. Among these, clustering techniques have proven to be effective in identifying patient subgroups with similar characteristics within the heterogeneous spectrum of diseases10,11,12. However, much of the prior literature is limited by small samples13, restriction to preselected severity levels14, or a narrow focus on isolated polysomnographic parameters15,16. Even studies that combine clinical and polygraphic data or leverage large cohorts have often restricted analyses to confirmed SA, excluding individuals with AHI < 5 (and, in some large datasets, even <15), which hinders generalizability to the pre-test clinical pathway. To address this gap, we deliberately included the full AHI spectrum—including AHI < 5—so that clustering reflects real-world pre-test heterogeneity.

The primary objective of this study is to identify the diverse clinical presentations of patients referred to a Sleep-Disordered Breathing Unit for suspected SA, using clinical-demographic data through unsupervised learning approaches. Once the clusters are identified, the results of sleep studies and CPAP prescriptions will be integrated to evaluate the differences among them. Finally, we aimed to develop an intelligent clinical decision support system (ICDSS) to facilitate the early and personalized management of patients prior to sleep studies.

Methods

Study cohort

The data used in this study were collected from a prospective cohort gathered between November 2014 and November 2024. The study included 5385 patients who were consecutively referred for suspected SA to the Sleep Respiratory Disorders Unit of Álvaro Cunqueiro Hospital in Vigo (Galicia, Spain). The study was approved by the Galicia Ethics and Research Committee (code 2022/256).

Patients were referred to the Sleep Unit only if they fulfilled a minimum set of symptoms and/or signs typically associated with SA. The essential requirement was habitual snoring or inability to report it (in those sleeping alone). In addition, patients were required to present at least one of the following: excessive daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale17,18 > 10), witnessed apneas, recurrent nocturnal choking awakenings, or resistant hypertension; alternatively, at least two of the following: multiple nocturnal awakenings without clear cause, non-restorative sleep, unexplained concentration problems, or significant unexplained fatigue. Referrals from primary care were standardized using a structured questionnaire that included these symptoms as well as anthropometric data and cardiovascular risk factors.

All patients were evaluated by expert pulmonologists and underwent diagnostic sleep studies through cardiorespiratory polygraphy. Only patients over 18 years of age were included, while cases with insufficient sleep study quality were excluded. A summary of the variables included can be found in the first column of Tables 1 and 2.

The information collected included demographic data, clinical characteristics, and sleep-related symptoms. The recorded variables included sex, age, employment status and shift work, body mass index (BMI), and neck circumference. Additionally, sleep-related symptoms were assessed, such as snoring, witnessed apneas, episodes of nocturnal asphyxia, nocturia, non-restorative sleep, morning grogginess, daytime fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and nocturnal awakenings. Their severity was rated using Likert-type scales (ranging from None/Never, Sometimes, Often, to Daily). Excessive daytime sleepiness was measured using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).

Comorbidities such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, rhinitis, and depression were documented, along with toxic habits like smoking and alcohol consumption. Regular medications were also recorded, including benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and hypnotics or muscle relaxants.

Regarding sleep studies, all patients underwent tests following SEPAR guidelines9. All patients underwent home or hospital-based cardiorespiratory polygraphy using Embletta devices (ResMed, Bella Vista, NSW, Australia). The AHI was established as the central parameter for both confirming the diagnosis of SA and determining its severity. In addition, we recorded Tc90 (time with peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) < 90% during the recording) and ODI3 (oxygen desaturation index using ≥ 3% drops in SpO₂).

Signals acquired during cardiorespiratory polygraphy were first auto-scored by the Embletta software (automatic detection of respiratory events and derived indices) and then underwent full visual review and manual correction by qualified staff. Segments with obvious artifacts (e.g., sensor disconnections) were marked and excluded during this manual review.

Conceptual design of the study

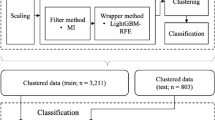

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram detailing the methodology of this study, which consists of two main blocks.

The first block focuses on the clustering of the cohort, resulting in five clusters (A, B, C, D, and E). Following this, a comparative analysis of the characteristics of individuals across the different clusters is conducted. The second block involves the development of the intelligent clinical decision support system, designed to facilitate the assignment of new patients to the clusters based on a reduced set of variables, thereby streamlining subsequent decision-making processes.

Block 1

Block 1 consists of two stages. In the first stage, the clustering of patients is carried out using the variables described in Table 1. Prior preprocessing was performed, including the rescaling of continuous variables and the analysis of possible asymmetric distributions. When necessary, the Box-Cox transformation19 was applied to normalize these distributions. Clustering was then performed with the k-prototypes algorithm —an extension of k-means for mixed-type data. Its objective function combines squared Euclidean distances for numeric variables with simple-matching dissimilarity for categorical variables, balanced by a weighting parameter (γ). Cluster prototypes are defined by means and modes20,21.

To explore alternative partitions, we evaluated k from 2–10 using the k-prototypes algorithm (Cao initialization22) with multiple random restarts per k until convergence. The optimal number of clusters was selected via the elbow method23 applied to the k-prototypes cost, complemented by the mean silhouette24 computed on the Gower25 dissimilarity matrix. No hard statistical threshold was imposed; further subdivision was halted when cost reductions beyond k = 5 were marginal and the silhouette plateaued, while clinical interpretability remained highest at k = 5. For visualization only, we projected the data to two dimensions using UMAP26 (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) on the Gower matrix (neighbors = 30, minimum distance = 0.3); the embedding did not inform clustering or k selection (Figs. 2 and 3).

Two-dimensional embedding illustrates the distribution of patients, colored by k-prototypes cluster assignment. Parameters: neighbors = 30, minimum distance = 0.3. This visualization is for illustration only and did not inform clustering or k selection; 2D distances are not directly comparable to the original feature space.

In the second stage, a comparative statistical analysis was conducted to identify significant differences among the patients in the different clusters. The Chi-square test27 was used for categorical variables, while the Mann-Whitney U test27 was applied for continuous variables.

Block 2

Once the clusters were identified and their clinical value analyzed, Block 2 focused on the development of the ICDSS. The ICDSS was conceived as a triage tool rather than a deterministic classifier. Clusters were interpreted as population-level patterns, not as rigid categories for individual decision-making. To avoid over-interpretation, the ICDSS suggests the most probable cluster assignment for each patient, while confirmatory testing and clinician oversight remain essential. The system was designed to use a reduced set of clinical-demographic variables, ensuring feasibility for real-world clinical implementation.

To define the inference engine, the dataset from the cohort used in Block 1 was employed, where each patient is associated with the corresponding cluster, which serves as a label. The cohort was divided into two subsets: a training subset comprising 80% of the cases and a test subset with the remaining 20%.

To determine the reduced set of predictive variables, the recursive feature elimination (RFE) technique28 was used in combination with the Random Forest algorithm. This iterative process successively eliminated variables with lower predictive power until the desired number of variables was obtained. Two scenarios were analyzed, one with 5 variables and another with 10. Beyond these prespecified scenarios, we explored multiple larger sets (>10 top-ranked variables) and found no clear or consistent AUC improvement over the 10-variable set. On this basis—and to preserve clinical usability—we adopted 10 variables as an adequate and manageable feature set. The ICDSS assigns each new patient to one of the five clusters based on the selected clinical-demographic variables. All diagnostic and therapeutic decisions remained under clinician responsibility, and no automated actions were implemented.

The analysis was performed using the Python environment (version 3.10.13). The libraries used for clustering and statistical analysis included kmodes (version 0.12.2), scipy (version 1.11.4), and scikit-learn (version 1.3.0).

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of Galicia approved this study (2022/256, 2 July 2022).

Results

Study population

Of the 5385 patients, 65·57% are men, with a mean age of 55·04 ± 12·98 years. The clustering process, based on the variables shown in Table 1, identified five clusters.

The number of clusters was selected in a data-driven approach: across k = 2–10, the k-prototypes cost curve showed an elbow at k = 5 (Fig. 2), and the mean silhouette was highest at k = 5 (0·09). A two-dimensional UMAP projection computed on the Gower matrix is provided for visualization only and did not inform clustering or k selection (Fig. 3).

As an illustrative aid, Fig. 4 displays synthetic portraits created after cluster derivation and clinical interpretation; images are independent of the analytic pipeline and not intended to represent demographic attributes.

Cluster A – middle-aged men, paucisymptomatic and non-sleepy (23·1%)

Majority of men (69·73%), with an average age of 55·47 years and BMI of 32·81. They exhibit few symptoms and have the lowest Epworth score (6·07). Their low prevalence of comorbidities reinforces their benign clinical profile.

Cluster B – symptomatic women, with psychotropic drugs and non-restorative sleep (16·9%)

Predominantly women (82·49%), with an average age of 52·89 years and the highest BMI (33·19). Higher rates of depression (14·43%), use of relaxants/hypnotics (15·97%), and antidepressants (7·27%). High prevalence of non-restorative sleep (68·17%), daytime fatigue (57·71%), lack of concentration (41·5%), and sleepiness (28·74%), all reported daily. Moderate sleepiness with an Epworth score of 11·49. Lower prevalence of hypertension (22·9%) and diabetes (7·27%).

Cluster C – young, highly symptomatic, and sleepy men (17·3%)

Primarily men (71·92%), the youngest group (average age of 49·83 years) with a BMI of 32·06. They exhibit severe sleepiness, with the highest Epworth score (16·70). Prominent symptoms include daily witnessed apneas (25·51%), daily non-restorative sleep (79·74%), and daytime fatigue (69·13%). This group also shows the highest prevalence of active smoking (32·58%).

Cluster D – middle-aged men with moderate symptomatology (22·3%)

Mainly men (76·37%), with an average age of 51·93 years and the lowest BMI (31·36). Mild sleepiness with an Epworth score of 10·59. Key symptoms include non-restorative sleep, fatigue, and morning grogginess, reported occasionally or frequently by 70–82% of patients. High rate of witnessed apneas (reported frequently or daily by 47%), similar to Cluster C (46%).

Cluster E – older, retired, comorbid, and paucisymptomatic men (20·4%)

This group has the highest proportion of men (83·36%) and the oldest average age (64·17 years), with a BMI of 32·20. They have the highest prevalence of hypertension (36·18%) and diabetes (9·82%). They exhibit few symptoms but report frequent nocturia (57·91%) and witnessed apneas frequently or daily (31%), though at lower rates than Clusters C and D. They have no significant sleepiness, with an average Epworth score of 9·50.

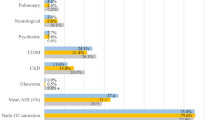

Association of clusters with polygraphic test results

Table 2 presents the results of the sleep studies. Cluster E exhibits the highest burden of respiratory disturbance, with the highest values of AHI (32·57), Tc90 (19·95), and obstructive apneas (72·21), reflecting greater severity. It also has the highest proportion of severe (27%) and very severe (20%) SA, justifying the high CPAP indication rate (65·55%). In contrast, Cluster B shows a more benign clinical profile, with the lowest average AHI (20·29) and the highest proportion of mild (30·40%) or absent (20·93%) SA. However, 56·06% of patients in this cluster received a CPAP prescription. Cluster C, with an average AHI of 29·41, has a severe and very severe SA rate of 37%, similar to Clusters A (37·76%) and D (34·53%). However, it stands out due to the highest CPAP prescription rate (77·71%), attributed to its high symptomatic burden. Cluster A (average AHI of 27·58) presents the lowest CPAP indication rate (47·99%), despite a considerable proportion of severe SA cases (37·76%). This suggests a perceived lower clinical impact and a less aggressive therapeutic approach. Finally, Cluster D shows a moderate clinical profile, with an AHI of 27·12 and a proportion of severe and very severe SA (34·53%) similar to Clusters A and C. Other polysomnographic parameters, such as Tc90 (14·91), obstructive apneas (52·85), supine AHI, and lateral AHI, reflect an intermediate severity. The CPAP indication rate of 58·82% aligns with the symptomatic intensity of this group.

Intelligent clinical decision support system

As previously mentioned, once the cohort was characterized, the goal was to develop an ICDSS to assign new patients to the clusters using a reduced set of variables. Two scenarios were considered, one with 5 variables and the other with 10. Figure 5 presents the ROC curves, along with a graph highlighting the importance of the selected variables in both scenarios. The importance was determined by averaging the reduction in impurity at each node of the Random Forest model trees.

The Random Forest algorithm was used as the inference engine. The upper graphs display the ROC curves for the test set, showing the model’s performance in assigning new patients to the clusters using the 5 and 10 most predictive variables, selected through RFE analysis. The lower graph illustrates the relative importance of each variable within the Random Forest model.

As shown, the dominant variables are: Age, Epworth score, BMI, neck circumference, daily perception of non-restorative sleep, absence of morning grogginess, absence of concentration issues, daily perception of sleepiness, being exempt from work, and being woman. Using these variables, AUC values between 0·87 and 0·95 were achieved for patient assignment in the test set. The 10-variable model yielded a clear AUC improvement relative to the 5-variable model; larger sets (>10) did not provide clear or consistent AUC gains over the already high performance, supporting 10 as an adequate feature set for bedside use.

Additionally, to streamline the management of patients within each cluster, Fig. 6 provides a summary of the diagnostic approach, which includes sleep studies, targeted questionnaires, and a more thorough evaluation by an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) or maxillofacial specialist.

To anchor these suggestions in the empirical findings, we provide a concise rationale for each cluster, linking the proposed early tests to the observed clinical–demographic and polygraphic patterns. These suggestions are exploratory and intended to support triage; individual decisions should be tailored to clinical context and confirmatory testing:

-

Cluster A. Low symptom burden and absence of marked sleepiness, with a broad AHI distribution and no specific enrichment of severe AHI, supports prioritizing a two-channel device to quantify early nocturnal respiratory disturbance and hypoxic burden (e.g., ODI3/Tc90), with escalation as clinically indicated.

-

Cluster B. High symptom burden (non-restorative sleep, daily fatigue) with the lowest proportion of severe AHI (~22%) and a high share with AHI < 15 (51%; 20.9% < 5), predominantly female (~83%)—often perimenopausal—and frequent central-acting medications, favors targeted anxiety/depression/insomnia screening and, when appropriate, referral to a menopause specialist; if a sleep study is pursued, polysomnography may be preferred to assess sleep fragmentation, sleep efficiency, and REM-predominant SA beyond AHI alone.

-

Cluster C. Very high sleepiness (highest ESS), male predominance (~72%), age <50 years, and ~37% with AHI < 15 justify initial cardiorespiratory polygraphy with escalation to polysomnography as needed; given age/airway profile, upper-airway/orofacial assessment may identify candidates for non-CPAP alternatives (e.g., mandibular advancement devices, maxillofacial surgery).

-

Cluster D. Prominent sleep fragmentation/nocturnal awakenings without consistent enrichment of severe AHI suggests prioritizing comprehensive clinical review of fragmentation drivers (sleep hygiene, substances, comorbid insomnia) and selecting polygraphy vs. polysomnography according to clinical context.

-

Cluster E. Low symptom burden with high cardiometabolic comorbidity and substantial respiratory disturbance supports prioritizing a two-channel device for early quantification; in patients with cardiovascular disease, polygraphy may be preferred to identify central hypopneas/Cheyne–Stokes respiration, potentially informing device selection.

Discusion

This study applies machine learning to clinical–demographic data collected before sleep testing to address the heterogeneity and varied healthcare needs of patients with suspected SA. Using unsupervised learning, we identified five clinically meaningful clusters differing in symptom profile, comorbidities, and demographic characteristics. These were subsequently used to develop an ICDSS based on a reduced set of variables, facilitating early and personalized triage before confirmatory testing.

The identified clusters reflect the broad phenotypic variability of SA and suggest that different pathophysiological mechanisms may underlie symptom expression and comorbidity burden. In our cohort, mean AHI and the proportions of patients with AHI ≥ 30 and ≥50 were similar between low-symptom clusters (A and E) and highly symptomatic clusters (B and C), consistent with previous studies5,16. These findings underscore the limited predictive power of pre-test clinical–demographic data for estimating objective SA severity.

Cluster-specific observations further support this complexity. Cluster E, composed of older patients with comorbidities, showed the highest proportion of severe SA (27%) and very severe SA (20%), along with elevated hypoxemia (Tc90:19·95). However, their low daytime sleepiness and few cardinal symptoms suggest that the severity of respiratory events does not always translate into evident symptomatology. This finding supports the hypothesis that certain groups respond physiologically differently to sleep fragmentation and nocturnal hypoxemia, affecting symptom perception, CPAP indication, tolerance, and benefit29.

Cluster C consists mainly of young men with a high symptomatic burden and severe sleepiness. The literature indicates that excessive daytime sleepiness is not always correlated with AHI30 but may be modulated by factors such as ventilatory instability (high loop gain) and a low arousal threshold in response to respiratory stimuli6. Our findings are consistent with studies by Eckert et al.6, suggesting that these factors define SA subtypes with differentiated treatment responses.

Cluster B predominantly includes women who frequently use of psychotropic drugs, with a low prevalence of hypertension and diabetes but a high burden of symptoms related to non-restorative sleep and daytime fatigue. These findings suggest a possible interaction between hormonal factors, sleep patterns, and autonomic regulation in the clinical manifestation of SA in women. Previous studies have highlighted that SA in women tends to be underdiagnosed due to differences in symptomatology31 and the distribution of respiratory events, with a higher prevalence of hypopneas during REM sleep31. This phenotypic variability has important implications for treatment selection, as certain subgroups may benefit from alternatives to CPAP therapy.

Clusters A and D represent intermediate SA profiles. Cluster A, consisting of middle-aged men with few symptoms, may require less intensive treatment. Conversely, Cluster D, with moderate symptomatology, could benefit from a detailed evaluation of sleep fragmentation32 and complementary strategies to improve the quality of nighttime rest. These findings emphasize the importance of tailoring the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to the patient’s clinical profile33.

Our results align with prior cluster analyses in sleep apnea but differ in several key aspects. Earlier studies often relied on clinical and polygraphic or polysomnographic data, included only confirmed SA cases (typically with AHI ≥ 5 or ≥15), and generally applied clustering post-diagnosis16,34,35,36. For instance, Romero-Peralta et al.34 identified five clinical clusters based on symptoms, comorbidities, and anthropometric measures, which are valuable for detecting atypical profiles and guiding initial management. However, they included sleep study results and excluded patients with AHI < 5. Gasa et al.16 focused exclusively on polysomnographic metrics, identifying three pathophysiological clusters emphasizing hypoxemia burden, body position, and sleep architecture. Bailly et al35. applied hierarchical clustering to over 18,000 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA (AHI > 15/h or ODI3 > 15/h), using only clinical, anthropometric, and comorbidity variables—but likewise excluded patients with AHI < 15. Ferreira-Santos et al. used a mixed approach, combining clinical, demographic, and polysomnographic data to define four clusters, aiming to capture overall OSA heterogeneity rather than provide early-stage clinical utility36.

In contrast, our study takes a different approach by using only pre-test clinical and demographic data, deliberately including the full AHI spectrum—including patients with AHI < 5—and applying clustering prior to diagnostic testing. This strategy supports real-world, pre-test decision-making and better reflects the diagnostic uncertainty present at the time of initial evaluation.

Our assistance-based cohort (n = 5385) is broadly consistent with other Spanish cohorts16,34 in terms of age, sex, BMI, Epworth scores, and AHI. Differences in hypertension prevalence and oxygenation metrics are likely due to the inclusion of AHI < 5 patients and differences in diagnostic modality (e.g., higher polysomnography usage in Gasa et al.35). Overall, the observed similarities support the generalisability of our findings to wider Spanish referral populations, although external validation remains necessary.

The ICDSS system is designed as a triage tool, not a diagnostic classifier. Clusters represent population-level patterns, not rigid individual categories. As shown in section 3.3, the system can aid in early resource allocation (e.g., two-channel devices, polygraphy, polysomnography), but clinician judgement and confirmatory testing remain essential. Internal validity was supported by the elbow method and silhouette index (mean ≈ 0.09 at k = 5), a modest value expected in large, heterogeneous clinical datasets with overlapping profiles. The UMAP projection (Fig. 3) offers visual support for cluster separation.

Nonetheless, limitations must be acknowledged. We did not include sleep architecture data, nor did we assess anxiety, depression, or insomnia, which may influence symptom profiles—particularly in clusters B and D. ENT evaluations were not performed, despite their potential relevance (e.g., in Cluster C). Longitudinal outcomes are unavailable, limiting our ability to assess treatment response. Physiological metrics such as hypoxic burden were not calculated, and standardized patient-reported outcome instruments (e.g., PSQI, ISI, FOSQ-10, HADS) were not used—although planned for future analyses. Finally, generalisability may be affected by our single-center design and diagnostic modality (polygraphy vs. polysomnography).

Future directions include:

-

Implementing automated hypoxic burden pipelines to assess added value over AHI/ODI3/Tc90.

-

Refining symptom modeling using composite factors and validated PRO instruments.

-

Externally validating the ICDSS across Spanish regions and subgroups (by age, sex, BMI, comorbidities).

In conclusion, unsupervised learning applied to clinical–demographic data can enhance early phenotypic classification in suspected SA, supporting a more tailored, efficient care model. Our ICDSS prototype offers a scalable triage tool, pending external validation. This approach could accelerate the shift toward more personalized, efficient, and need-based SA care.

Data Availability

This study uses a private dataset, which cannot be shared at this stage as the research is still ongoing and has not yet been completed.

References

Benjafield, A. V. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir. Med 7, 687–698 (2019).

Marin, J. M., Carrizo, S. J., Vicente, E. & Agusti, A. G. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 365, 1046–1053 (2005).

Flemons W. W., Douglas N. J., Kuna S. T., Rodenstein D. O., Wheatley J. Access to Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with Suspected Sleep Apnea. 101164/rccm200308-1124PP 169:668–672. Available from: www.statcan.ca (2012).

Berry, R. B. et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events. deliberations of the sleep apnea definitions task force of the american academy of sleep medicine. J. Clin. Sleep. Med 8, 597–619 (2012).

Ye, L. et al. The different clinical faces of obstructive sleep apnoea: a cluster analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 44, 1600 (2014).

Eckert, D. J., White, D. P., Jordan, A. S., Malhotra, A. & Wellman, A. Defining phenotypic causes of obstructive sleep apnea: identification of novel therapeutic targets. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 188, 996–1004 (2013).

Robichaud-Hallé, L., Beaudry, M. & Fortin, M. Obstructive sleep apnea and multimorbidity. BMC Pulm. Med 12, 1–7 (2012).

Punjabi, N. M. et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 6, e1000132 (2009).

Mediano, O. et al. Documento internacional de consenso sobre apnea obstructiva del sueño. Arch. Bronconeumol. 58, 52–68 (2022).

Casal-Guisande, M. et al. Clinical and social characterization of patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation using machine learning tools. Arch. Bronconeumol. 61, 264–273 (2024).

Villar-Aguilar, L. et al. Characterisation of patients with Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency using unsupervised machine learning tools. Respir. Med 247, 108278 (2025).

Muñoz-Martínez, M.-J., Casal-Guisande, M., Torres-Durán, M., Sopeña, B. & Fernández-Villar, A. Clinical characterization of patients with syncope of unclear cause using unsupervised machine-learning tools: a pilot study. Appl Sci. 15, 7176 (2025).

Lacedonia, D. et al. Characterization of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (OSA) population by means of cluster analysis. J. Sleep. Res 25, 724–730 (2016).

Keenan, B. T. et al. Recognizable clinical subtypes of obstructive sleep apnea across international sleep centers: a cluster analysis. Sleep 41, zsx214 (2018).

Zinchuk, A. V. et al. Polysomnographic phenotypes and their cardiovascular implications in obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 73, 472–480 (2018).

Gasa, M. et al. Polysomnographic phenotypes of obstructive sleep apnea in a real-life cohort: a pathophysiological approach. Arch. Bronconeumol. 59, 638–644 (2023).

Johns, M. W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14, 540–545 (1991).

Johns, M. W. Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea; the epworth sleepiness scale. Chest 103, 30–36 (1993).

Box, G. E. P. & Cox, D. R. An analysis of transformations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 26, 211–243 (1964).

Huang, Z. X. Clustering large datasets with mixed numeric and categorical values. In: First Pacific-Asia Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining Conference. p. 21–34 (World Scientific, Singapore, 1997).

Huang, Z. Extensions to the k-means algorithm for clustering large data sets with categorical values. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2, 283–304 (1998).

Cao F., Liang J., Bai L. A new initialization method for categorical data clustering. Expert Syst Appl 2009;36:10223–10228.

Han, J., Kamber, M., Pei, J. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques. Morgan kaufmann: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012). Third Edition.

Shahapure, K. R., Nicholas, C. Cluster quality analysis using silhouette score. Proceedings - 2020 IEEE 7th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics, DSAA 2020 2020;747–748.

Gower, J. C. A general coefficient of similarity and some of its properties. Biometrics 27, 857 (1971).

McInnes L., Healy J., Melville J. UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/pdf/1802.03426. (2018).

Samuels, Myra L., Witmer, Jeffrey A. & Schaffner, Andrew A. Statistics for the Life Sciences. Fifth Edition, (Pearson Education, London, 2016).

Jeon, H. & Oh, S. Hybrid-recursive feature elimination for efficient feature selection. Appl Sci. 10, 3211 (2020).

McEvoy, R. D. et al. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N. Engl. J. Med 375, 919–931 (2016).

Durán, J., Esnaola, S., Rubio, R., Iztueta, Á. Obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea and related clinical features in a population-based sample of subjects aged 30 to 70 Yr. 163, 685–689. 101164/ajrccm16332005065(2012).

Bonsignore, M. R., Saaresranta, T., Riha, R. L., Riha, R., Bonsignore, M. Sex differences in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir Rev. 28, 190030 (2019).

Palanca Sanchéz, I. et al. Grupo de Expertos Unidad del sueño: estándares y recomendaciones de calidad y seguridad Madrid. (Ministerio de Sanidad, Política Social e Igualdad, Spain, 2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Worldwide and regional prevalence rates of co-occurrence of insomnia and insomnia symptoms with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. Med Rev. 45, 1–17 (2019).

Romero-Peralta, S. et al. Defining the heterogeneity of sleep apnea syndrome: a cluster analysis with implications for patient management. Arch. Bronconeumol. 58, 125–134 (2022).

Bailly, S. et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: a cluster analysis at time of diagnosis. PLoS One 11, e0157318 (2016).

Ferreira-Santos, D. & Rodrigues, P. P. Obstructive sleep apnea: a categorical cluster analysis and visualization. Pulmonology 29, 207–213 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This paper is part of the research conducted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Ph.D. degree of Mar Mosteiro-Añón. This manuscript was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project PI24/00570 and co-funded by the European Union. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: M.M.-A., M.C.-G., A.F.-V. and M.T.-D.- Data curation: M.M.-A. and M.C.-G.- Investigation: M.M.-A., M.C.-G., A.F.-V. and M.T.-D.- Methodology: M.C.-G. and A.F.-V.- Visualization: M.M.-A. and M.C.-G.- Supervision: A.F.-V. and M.T.-D.- Writing – original draft: M.M.-A. and M.C.-G.- Writing – review & editing: A.F.-V. and M.T.-D.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT-4o for translation and to enhance the writing style. Additionally, Grok 2 was used to generate Fig. 4. After utilizing these tools, the author(s) thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as necessary and take full responsibility for the final publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mosteiro-Añón, M., Casal-Guisande, M., Fernández-Villar, A. et al. AI-driven clinical decision support for early diagnosis and treatment planning in patients with suspected sleep apnea using clinical and demographic data before sleep studies. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 51 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00455-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00455-5