Abstract

Introduction: When high-risk patients present lung cancer symptoms (LCSs) in general practice, Computed Tomography of the thorax (CT thorax) is recommended, but chest X-ray (CXR) may still be used often. This population-based study aims to 1) compare the proportion of patients who completed diagnostic evaluation, and 2) analyse the associations between smoking status, symptom burden and first choice of imaging among patients who presented LCS to their general practitioner (GP) in 2012 and 2022.

Methods: Two random samples of 100,000 individuals ≥20 years were invited to a survey about symptoms and healthcare seeking in 2012 and 2022, respectively, with subsequently linkage to register data. We included individuals ≥40 years old who reported GP contact with LCSs. Descriptive statistics and multivariable regression models were applied.

Results: A total of 5910 (16%) and 4883 (22%) individuals reported at least one LCS in 2012 and 2022, respectively, and 2538 (43%) and 2229 (46%), respectively, had contacted their GP. Diagnostic imaging was completed by 2538 (24%) in 2012 and 2229 (22%) in 2022. CXR was the most common first choice of imaging in both years (22% and 15%, respectively), although CT thorax as first choice increased from 2% to 7%. Higher symptom burden and former smoking increased the odds of completing diagnostic imaging while current smoking did not.

Conclusion: One out of five patients with lung cancer symptoms completed diagnostic evaluation. CXR remained first choice, although more completed CT thorax in 2022. GPs may need tools to support risk stratification and choice of imaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most diagnostics of lung cancer are initiated in general practice1. Although lung cancer screening has been introduced in some countries, most cancers must still be diagnosed based on symptoms presented to general practitioners (GPs)2,3. GPs possess valuable insights into their patients’ lifestyles and health risk behaviours, which provides them with a unique opportunity to assess each individual’s cancer risk and make stratified clinical decisions. It is essential for timely diagnosis that patients seek care when they experience symptoms indicative of lung cancer, and that GPs refer these for diagnostic evaluation when relevant1,4. Significant improvements in overall survival rates for patients with lung cancer have been observed during the recent decades due to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatments5,6. However, two out of three patients with lung cancer are still diagnosed at advanced stage, where treatment options are limited and prognosis poor5,6.

In several countries, fast track cancer care pathways (CCPs) have been implemented to optimise the time between first symptom to diagnosis to the treatment of cancer7,8,9. The Danish lung CCP was established in 2009 with a minor update in 201210. The CCP recommends that GPs refer patients presenting with lung cancer symptoms for diagnostic imaging. Symptoms included in the first CCP were prolonged coughing, dyspnoea, haemoptysis and prolonged hoarseness, and the recommended first choice of diagnostic imaging was chest X-ray (CXR). In 2018, the CCP underwent a thorough revision that altered three overall features: 1) the lung cancer symptoms were expanded with changes in a familiar cough and non-specific symptoms such as weight loss, loss of appetite and tiredness; 2) the risk group was narrowed to individuals who were 40 years or older with a relevant history of tobacco use and 3) the recommended first choice of imaging was changed to Computed Tomography scan of the thorax (CT thorax)11. Whether these changes have been implemented successfully in clinical practice remains unknown. In addition to referral to a CT thorax when suspecting lung cancer, Danish GPs may also choose to refer for a non-specific cancer care pathway (NS-CCP), which often includes a CT thorax, if the symptoms don’t clearly point to a specific illness. Additionally, they can directly refer patients for a CT thorax and abdomen on suspicion of other diseases, through a pathway called the third track12.

Most studies exploring the usage of CT scans and diagnostic pathways are based on data on patients already diagnosed with lung cancer13,14,15,16. Hence, they lack information about individuals who did not undergo diagnostic imaging or were ultimately not diagnosed with lung cancer. As the strongest risk factor, smoking history plays a crucial role in both the appraisal and management of symptoms in the general population17,18,19 and in the suspicions raised by healthcare professionals20,21. Additionally, symptom burden can affect the interpretations and actions taken20,22. Danish register studies cannot include smoking history or symptom burden as explanatory variables, resulting in limited knowledge about their influence on referral patterns.

Knowledge about how the diagnostic evaluation of patients presenting with lung cancer symptoms in general practice is conducted could be important for improving lung cancer guidelines and the development of educational initiatives for GPs and other healthcare professionals.

Using data from two population-based surveys and related register data, this study aims to 1) compare the proportion of patients who have completed diagnostic evaluation in terms of imaging in 2012 and 2022, and 2) analyse the associations between smoking status, symptom burden and first choice of diagnostic imaging among patients who presented lung cancer symptoms to their GP in 2012 and 2022.

Methods

Study samples and logistics

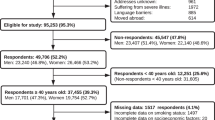

This study utilises data from two nationwide surveys: the Danish Symptom Cohort (DaSC) study from 2012 and a follow-up and expansion, the DaSC II study, from 2022, combined with register data23,24. In each study, a random sample of 100,000 individuals aged 20 years or over was selected through the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) using the unique personal identification number (CRS number) assigned to each individual living in Denmark25. The invitees were invited to participate in a survey about symptoms and healthcare-seeking behaviour by post in 2012 and by digital mail in 2022. Non-respondents received reminders after fourteen days in 2012, and after an additional fourteen days they were contacted by phone by a marketing agency encouraging participation and asking for reasons for non-participation. In 2022, reminders were sent via digital mail after seven and fourteen days. Data were collected from June to December in 2012 and from May to July in 2022. The study populations and logistics have been described in further detail elsewhere23,24. Reporting followed the Strobe Checklist for Cohort Studies.

Setting

The Danish healthcare system is universal and primarily financed by taxation. More than 98% of all citizens are listed with a general practice, and GPs serve as gatekeepers who can refer patients to both out- and inpatient hospital contacts, private practicing specialists and other healthcare providers, including diagnostic imaging and cancer diagnostic pathways26. The GPs refer patients for diagnostic imaging at the hospitals, and the majority of lung specialists are located at the hospitals, whereas only few private lung clinics exist27.

Questionnaire development and data

The development of both questionnaires followed the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN)28. Prior to data collection, both questionnaires were pilot tested several times and subsequently field tested in a random sample, resulting in minor changes in content and wording. Both questionnaires showed good comprehensibility and content validity. Details of the conceptual frameworks and questionnaire development are described elsewhere23,24.

In the present study, we included questionnaire data regarding four predefined lung cancer symptoms: prolonged coughing ( > 4 weeks); dyspnoea; haemoptysis; and prolonged hoarseness ( > 4 weeks). We chose to limit the symptoms to the four symptoms contained in the Danish lung CCP both before and after the 2018 revision to ensure comparability11. Further, we included questionnaire data on smoking status. The wording of each question is shown in the supplementary materials, Table S1.

Register data

Questionnaire data were linked to register data using the CRS numbers. Data on sex, age and vital status were obtained from the Danish Health Data Authority29. Socioeconomic data were obtained from Statistics Denmark30,31,32. The variables of interest were marital status, highest obtained level of education, labour market affiliation and ethnicity. Details on registers and coding are provided in the supplementary materials, Table S1.

Data on diagnostic imaging were obtained from the Danish National Patient Register33 and included CXR (Codes: UXRC and UXRC00) and CT thorax (Codes: UXCC, UXCC00 and UXCC75). Data on first choice of imaging, i.e. CXR or CT thorax, were evaluated six months prior to and post survey data collection, with the median of the collection periods as index dates. Hence, the time periods of interest were 1 March 2012 to 28 February 2013 and 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2022, Fig. 1. Details on registers and coding are provided in the supplementary materials, Table S1.

Study population

Individuals who died or migrated prior to the data collection period or did not have digital mail were excluded prior to invitation34. We only included respondents 40 years or older in the analyses, in accordance with the current Danish lung CCP11, and applied list-wise deletion of individuals with incomplete questionnaire data. Individuals who had contacted their GP about at least one lung cancer symptom were of main interest in the study population.

Outcome measures

We constructed three outcome measures: 1) Total imaging including individuals who completed either CXR or CT thorax as first choice modalities of imaging in the diagnostic course; 2) CXR as first choice modality, and 3) CT thorax as first choice modality to enable evaluation of both the absolute number of patients who completed diagnostic imaging and comparison of the first choice of imaging in 2012 and 2022. We only included one imaging per patient within the study period, even though some had completed more. To ensure that the imaging conducted during these periods was the first imaging procedure in this diagnostic course, individuals with a registered imaging in a three-month washout period, prior to the observation period, were excluded, Fig. 1. For patients who had completed more than one diagnostic imaging, only the first was included in the analyses. Procedures that were registered as performed acute were excluded, as these are related to visits to the emergency department or hospital admissions35.

Covariates

We calculated the number of symptoms reported by each individual to evaluate symptom burden. Individuals with missing socioeconomic data were assigned to the largest group within each variable. The covariates included were categorised as follows. Age: 40-54 years; 55-69 years; 70+ years. Smoking status: never – individuals who never smoked; former – individuals who formerly smoked; and current – individuals who currently smoke36. Symptom burden: 0 symptoms; 1 symptom; 2 symptoms; and ≥3 symptoms.

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of the study population were calculated using descriptive statistics and compared using chi square tests. To provide an overview of the diagnostic activity, the total number of individuals who had completed diagnostic imaging and their first-choice modality was calculated for the study sample, the respondents, and the study population of main interest: patients who had contacted their GP about at least one lung cancer symptom. The remaining analyses were only conducted among the main study population. We calculated the proportion of patients who had completed diagnostic imaging and the first choice of imaging in total and for each covariate. The associations between sex, age, smoking status, symptom burden and diagnostic imaging were analysed in uni- and multivariable logistic regression models. Due to significant differences in the crude and adjusted results for smoking status, we explored the potential confounders post hoc by implementing them stepwise in the multivariable regression model. Further, we tested post hoc for interaction between smoking status and symptom burden.

Data analyses were conducted using Stata version 18 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All tests used a significance level of p < 0.05.

Ethics

The respondents were informed about the purpose and content of the study, that participation was voluntary and that there would be no clinical follow-up. They were further instructed to contact their doctor in case of concern. Respondents had the opportunity to contact the project group by phone or email if further clarification was needed. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Southern Denmark (case no. 21/29156) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency (j.no. 2011-41-6651) through the Research and Innovation Organisation (RIO), University of Southern Denmark (project number 10.104).

Results

Of the individuals eligible for invitation, 49,706 (52.2%) and 31,415 (33.9%) answered the questionnaire in 2012 and 2022, respectively; of these, 35,958 and 22,077, respectively, were ≥40 years old and had answered all questions of relevance, Fig. 2. A total of 5910 (16.4%) and 4883 (22.1%) individuals reported at least one lung cancer symptom in 2012 and 2022, respectively, and of these 2538 (42.9%) and 2229 (45.6%), respectively, had contacted their GP, Table 1. Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

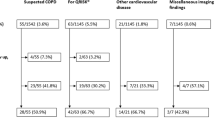

Table 2 shows the proportion of diagnostic imaging in the entire study samples, among respondents, and among subsamples. The total proportions of diagnostic imaging were similar in the two study samples (2012: 5931, 5.9%; 2022: 5412, 5.4%), among all respondents (2012: 2958, 6.0%; 2022: 2044, 6.5%) and among respondents ≥40 years (2012: 2568, 7.1%; 2022: 1691, 7.7%). The proportion of diagnostic imaging was higher among respondents reporting at least one lung cancer symptom (2012: 947, 16%; 2022: 693, 14.2%). The same tendencies were found in the analyses stratified on first choice of imaging, Table 2.

The proportion of diagnostic imaging among patients who had presented at least one lung cancer symptom to their GP is shown in Table 3. A total of 613 (24.2%) and 483 (21.7%) patients had completed diagnostic imaging in 2012 and 2022, respectively. The proportion of CXR as first choice of imaging was lower in 2022 (332, 14.9%) than in 2012 (552, 21.7%), whereas the proportion of CT thorax as first choice of imaging was higher in 2022 (151, 6.8%) than in 2012 (61, 2.4%), Table 3. Likewise, did the proportion of CT scans among those who completed imaging increase from 10.0 to 31.3% from 2012 to 2022. In general, the proportions of diagnostic imaging were higher among patients with high age, patients who had formerly smoked, and patients with high symptom burden in both 2012 and 2022. For single symptoms, the proportion of diagnostic imaging was highest for patients reporting haemoptysis in both 2012 (16, 69.6%) and 2022 (16, 43.2%), whereas it did not exceed 27% for the remaining symptoms, Table 3.

Table 4 shows the adjusted associations between patient characteristics and diagnostic imaging in 2012 and 2022. Patients who formerly smoked had higher odds of having completed diagnostic imaging and CXR in 2012 (ORtotal 1.47, 95% CI: 1.08;1.82 and ORCXR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.17;1.88) and in 2022 (ORtotal 1.26, 95% CI: 1.00;1.58 and ORCXR 1.33, 95% CI: 1.02;1.73) compared to patients who never smoked. No differences in the likelihood of having completed diagnostic imaging were found between patients who currently and never smoked, Table 4. In crude analyses, current smoking increased the odds of having completed diagnostic imaging (OR2022 1.43, 95% CI 1.21-1.68) as well as CXR (OR2022 1.39, 95% CI 1.13-1.72) and CT thorax (OR2022 1.43, 95% CI 1.11-1.84) in both 2012 and 2022, Supplementary Table S2. The post hoc stepwise implementation of potential confounders revealed that symptom burden significantly confounded the association between current smoking and diagnostic imaging. No interactions were found between symptom burden and smoking status.

Patients who reported two lung cancer symptoms were more likely to have completed diagnostic imaging in 2012 (ORtotal 1.25, 95% CI: 1.01;1.55) and in 2022 (ORtotal 1.26, 95% CI: 1.00;1.58), and patients reporting three or more symptoms had two and a half times higher odds of having completed diagnostic imaging in 2012 (ORtotal 2.66, 95% CI: 1.87;3.80) compared to patients reporting only a single symptom, Table 4.

Discussion

Main findings

About 24% of those who contacted general practice about lung cancer symptoms were referred and completed diagnostic imaging, in terms of CXR or CT thorax in 2012. In 2022, the proportion of diagnostic imaging was slightly lower (22%). CXR was the most common first choice of imaging in both years, but the proportion of patients completing CXR decreased from 22% in 2012 to 15% in 2022, whereas the proportion of patients completing CT thorax as first choice of imaging increased from 2% in 2012 to 7% in 2022. The percentage of patients who initiated with a CT thorax out of those who completed a diagnostic imaging increased from 10% in 2012 to 31% in 2022.

Less than one third of the patients with a smoking history had completed diagnostic imaging. Noticeably, individuals who currently smoked did not have higher odds of having completed diagnostic imaging in either 2012 or 2022. In contrast, individuals who formerly smoked were more likely to have completed diagnostic imaging compared to individuals who had never smoked in both cohorts. Higher symptom burden also increased the odds of having completed diagnostic imaging.

Discussion of the results and comparison with other literature

The slight decrease in the proportion of diagnostic imaging from 2012 to 2022 found in the present study was unexpected and contrasts with the general national increase in the use of radiology37. However, more patients who contacted their GP about lung cancer symptoms had imaging compared to the general population. The discrepancy between the national tendencies may be due to differences in methodology. Whereas the national statistics include all imaging procedures, we examined the first choice of imaging. Thus, we only included one imaging per individual within the study period, even though some had completed more. Furthermore, we only included non-acute examinations in the present study because we aimed to explore the diagnostic interval from symptom presentation in general practice to referral to diagnostic evaluation of potential lung cancer7.

The 2018 revision of the Danish lung CCP provided GPs with direct access to referring to CT scans. This revision did not induce a significantly increased use of scans in our study, which is in line with the findings by Guldbrandt et al.38. This contradicts previous theories, which suggests increased referral for diagnostic imaging by GPs due to diagnostic uncertainties39 and thus leading to overdiagnosis40. In the present study, a substantial number of individuals with symptoms, potentially indicative of lung cancer, did not undergo diagnostic imaging. There are likely several good explanations for this. For instance, another reason for the symptom(s) might have been found during the consultation, the physical examination was normal, or the GP hesitated for other reasons30. For some of the patients, diagnostic imaging might though have been relevant. Bradley et al. have suggested that the gatekeeper system can impede timely referral and risk stratification31. Yet increasing referral rates in general for lung cancer would probably not be beneficial, as the conversion rate is stably low32 and most early stage cancers are found by coincidence15. This implies that tools or initiatives capable of improving the detection rate among GPs and choice of imaging could be relevant41.

It is emphasised in the Danish lung CCP that suspicion of lung cancer among high-risk patients should lead to referral to CT thorax11. However, although the percentage of CT thorax increased, CXR was still the most common first choice of imaging in 2022, implying that GPs may not fully comply with the guideline. This is in line with Wiering et al., who found inconsistencies in the concordance with cancer guidelines among GPs in the UK42. The dissemination of the changes in the Danish lung CCP was limited, but for some GPs, referral to CT scans have probably become a part of everyday diagnostics, whereas others may prefer referral to CXR43,44. Implementation may also have been challenged at the radiology departments, who have authority to dismiss referrals from general practice. Therefore, some referrals to CT thorax may have been dismissed ultimately imposing the GPs to refer to CXR as standard instead. Although clinical decision making is based on extensive knowledge along with the patient´s history, clinical and laboratory findings, as suggested in the hypothetic-deductive approach45, cognitive bias is unavoidable in everyday clinics. Many clinical decisions are based on an intuitive process, making it challenging to change clinical habits46,47. The frequency of contacts to general practice often increases prior to a cancer diagnosis48, supporting that some opportunities for diagnosing cancer may be missed. The risk of biased clinical decision making is higher in primary care, where patients are undifferentiated and consultation time is often limited46,49, yet appropriate dissemination of information and awareness of possible pitfalls may be beneficial in the implementation of new and the alteration of previous clinical practices50,51.

Harris et al. suggested lack of availability of tests as a limitation for improving timely diagnosis of cancer52. The CT capacity in Denmark is high and access to radiology departments is relatively straightforward, hence it cannot solely explain the results in the present paper. Some GPs may consider CT scan as an extensive examination and prefer CXR; others may initiate with CXR and follow-up with a CT scan44. Some of the CXR may have been conducted on suspicion of pneumonia. However, for the prolonged symptoms, infection is less likely, why it seems reasonable to consider CT thorax relevant. Because we examined first choice imaging, some, but far from all, of those who completed CXR as first choice of imaging in our study may subsequently have completed a CT thorax. One in four to five lung cancers are undetectable on CXR53,54. Therefore, ruling out lung cancer based on a CXR might induce a kind of search satisfying bias46,47 and possibly inhibit the chance of timely diagnosis.

Stratification in general practice is challenging, despite GPs possessing extensive knowledge about their patients and their risk profiles. In the present study, less than one third of the patients with a smoking history had completed diagnostic imaging. Further, most of those had completed a CXR. The present results are in line with vignette studies showing that risk profile does not influence the decision of referral55,56. This is partly in contrast to Kostopoulou et al., who showed that older age, smoking history and coughing were associated with a lower chance of missing relevant referral, whereas breathlessness and non-specific symptoms such as loss of appetite and fatigue increased the risk57. Another considerable factor is pre-existing chronic disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which has been emphasised as a delaying factor in both healthcare seeking and decision of referral58,59.

The slight difference between patients with and without a smoking history contributes to the discussion on the use of health resources. Although the CT capacity in Denmark is high, it is not inexhaustible, and in an overstretched healthcare system resources must be prioritised16. Bradley et al. concluded that high specificity and negative predictive values make CXR sufficient to rule out lung cancer among low-risk patients60. However, diagnostic imaging is just a snapshot and does not provide long term guarantees of patients being disease free61. Thus, tools that can support risk stratification and prioritization in general practice based on both symptoms and risk factors are warranted. Some instruments have been developed62, but to our knowledge none have been fully implemented in general practice. Additionally, testing for circulating tumour DNA among symptomatic patients has been found feasible in assisting GPs with their clinical decision-making and stratification of the diagnostic evaluation of patients presenting possible symptoms of cancer63, but challenges still exist and it is still not applicable for implementation.

In the present study, higher symptom burden increased the likelihood of completing diagnostic imaging and confounded the influence of smoking status. A reason for this could be that it is easier for both patients and GPs to dismiss or overlook a single symptom than multiple symptoms64, and multiple symptoms may cause more concern and increase the GP’s suspicion of cancer regardless of smoking status65. Several other factors could also influence the decision of referral, such as the relation and communication between GPs and patients as well as the patient’s wishes or demands regarding diagnostic evaluation21,66. Some patients may insist on further examination, whereas others find interaction with the healthcare system difficult or inconvenient, due to factors such as distance to the hospital, and avoid contact19, which potentially contributes to the inequities seen in lung cancer diagnostics and prognoses.

Strengths and limitations

The possibility of investigating diagnostic evaluation among patients who had contacted their GP about lung cancer symptoms regardless of whether they had subsequently been diagnosed with lung cancer is considered a strength of this study. The study adds to existing evidence on the use of diagnostic imaging and lung cancer diagnostics by providing insights into the likelihood of patients being examined when contacting general practice about lung cancer symptoms and highlights potential improvements. Further, the results enable discussions about the extent to which the changes made in the Danish lung CCP in 2018 have been implemented in clinical practice and add perspectives to the trends of time with focus on diagnostic uncertainties and timely, under- and overdiagnosis67,68.

The combined questionnaire and register-based study design enables investigation of subgroups with different smoking history. However, the study design also has some limitations. It is not known what happened during the consultations in general practice or what led to the decision of whether or not to refer the patient for diagnostic imaging. We did not have information on non-imaging procedures performed in general practice, such as spirometry, blood tests or electrocardiograms, which may have explained the patients’ symptoms and facilitated treatment in general practice making diagnostic imaging unnecessary. Further, we do not know the number of patients who did not complete diagnostic imaging after they had been referred, as the Danish registers do not contain information on non-attendance at the radiology departments. The chosen period for diagnostic imaging might also be debatable. We do not have a certain link between the GP contact reported in the questionnaire and the diagnostic imaging extracted from the registers. However, as some of the symptoms could have been prolonged and some patients may have consulted their GP several times before referral48, we chose a broad time span to ensure the inclusion of all possible relevant imaging. This may cause an overestimation of the proportion of diagnostic imaging. On the other hand, we excluded imaging performed acutely, as it is linked to imaging ordered by the emergency departments. However, some of the patients who contacted their GP may have had severe symptoms, thus prompting the GP to admit the patient immediately. Such cases have been excluded, which may induce an underestimation of diagnostic imaging and indicate that the GP did not refer for diagnostic evaluation even though their actions were clinically relevant. It is not possible to differentiate between causes of admission or indications of diagnostic imaging in the registers. Hence, we do not know whether the CT scans were performed in the CCP, NS-CCPs or in the third track run, but any of these pathways would result in diagnostic evaluation. Despite the large sampling frames, some of the analyses may be underpowered due to few CT scans, for example, and risk of type II error cannot be rejected.

The development of the questionnaire followed the COSMIN taxonomy28, and both questionnaires showed good content validity and feasibility. The response rates were higher in 2012 than in 2022, likely due to time trends of decreasing participation in surveys and because the reminder procedures differed significantly23,24. In both studies, more of the respondents were female, cohabiting and had higher educational level than the non-respondents. The differences were more pronounced in 2022 than in 201224,69. Selection bias cannot be ruled out, but both study populations comprised individuals of different sexes, ages and socioeconomic status, enabling the analysis of subgroups. In the present study, the two study populations were comparable apart from differences in educational level and smoking status.

Implications

This study indicates that efforts targeting better concordance with the lung CCP may be beneficial regarding both the timely diagnosis of lung cancer and prioritisation and stratification in an overstretched healthcare system with limited resources. Although studies have shown that many early stage lung cancers are found by coincidence on imaging conducted for other reasons15, conducting more examinations is not effective when the conversion rates are stably low32. Hence, focus should be on stratifying patients presenting with symptoms and referring for the most convenient diagnostic imaging, e.g. high-risk patients to CT thorax, in accordance with the guidelines. Risk stratification tools developed for use in general practice, or the analysis of circulating tumour DNA could be applicable to improve the chance of timely diagnosis of lung cancer62,63.

The present study indicates that the 2018 version of the Danish lung cancer guideline is not yet being fully implemented in clinical practice and emphasises a need to communicate the content of the cancer guidelines to GPs more explicitly. This could be done through the systematic education of GPs and staff in general practice. Furthermore, the radiology departments may also play an important role, as the radiologist could change the choice of imaging from CXR to CT thorax, and vice versa, when considered relevant44.

Conclusion

The proportion of diagnostic imaging among patients who had presented lung cancer symptoms to their GP was slightly lower in 2022 (22%) than in 2012 (24%). CXR remained the most common imaging, even though the proportion decreased over the decade. The proportion of patients completing CT thorax as first choice of imaging almost tripled from 2012 to 2022, but only 7% of the patients who had presented lung cancer symptoms in general practice had completed a CT thorax in 2022. A former smoking history and higher symptom burden was associated with higher likelihood of having completed diagnostic imaging, whereas current smoking did not alter the likelihood of having completed diagnostic imaging, as hypothesised.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed in the current study are not publicly available and cannot be shared due to the data protection regulations of the Danish Data Protection Agency. Access to data is strictly limited to the researchers, who have obtained permission for data processing. This permission was given to the Department of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark. Further enquiries can be made to PI Dorte Jarbøl, email: DJarbol@health.sdu.dk.

Code availability

The statistical analyses were performed on the servers of Statistics Denmark.

References

Guldbrandt, L. M., Fenger-Grøn, M., Rasmussen, T. R., Jensen, H. & Vedsted, P. The role of general practice in routes to diagnosis of lung cancer in Denmark: a population-based study of general practice involvement, diagnostic activity and diagnostic intervals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 15, 21 (2015).

Hoffman, R. M., Atallah, R. P., Struble, R. D. & Badgett, R. G. Lung cancer screening with low-dose CT: a meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 35, 3015–3025 (2020).

Amicizia, D. et al. Systematic review of lung cancer screening: advancements and strategies for implementation. Healthcare 11, 2085 (2023).

Koo, M. M. et al. Presenting symptoms of cancer and stage at diagnosis: evidence from a cross-sectional, population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 73–79 (2020).

Jacobsen, M. M. et al. Timeliness of access to lung cancer diagnosis and treatment: a scoping literature review. Lung cancer 112, 156–164 (2017).

Steding-Jessen, M., Engberg, H., Jakobsen, E., Rasmussen, T. R. & Møller, H. Progress against lung cancer, Denmark, 2008-2022. Acta oncologica 63, 339–342 (2024).

Weller, D. et al. The aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br. J. Cancer 106, 1262–1267 (2012).

Lynch, C. et al. Variation in suspected cancer referral pathways in primary care: comparative analysis across the international benchmarking cancer partnership. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 73, e88–e94 (2023).

Christensen, N. L., Jekunen, A., Heinonen, S., Dalton, S. O. & Rasmussen, T. R. Lung cancer guidelines in Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland: a comparison. Acta oncologica 56, 943–948 (2017).

Danish Health Authority Cancerpackage for Lung Cancer (Pakkeforløb for lungekræft). Copenhagen; 2012.

Danish Health Authority. Cancerpackage for Lung Cancer (Pakkeforløb for lungekræft). Danish Health authority; 2018. Report No.: 978-87-7014-022-5.

Danish Health Authority. Det Diagnostic package (Det Dianostiske pakkeforløb). Denmark: The Danish Health Authority; 2022.

Rankin, N. M. et al. Pathways to lung cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of patients and general practitioners about diagnostic and pretreatment intervals. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 14, 742–753 (2017).

Christensen, H. M. & Huniche, L. Patient perspectives and experience on the diagnostic pathway of lung cancer: A qualitative study. SAGE Open. Med. 8, 2050312120918996 (2020).

Borg, M. et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules may lead to a high proportion of early-stage lung cancer: but it requires more than a high CT volume to achieve this. Eur. Clin. Respir. J. 11, 2313311 (2024).

Ditte Skadhede, T. et al. Outcomes and characteristics of danish patients undergoing a lung cancer patient pathway without getting a lung cancer diagnosis. a retrospective cohort study. Eur. Clin. Respiratory J. 8, 1923390 (2021).

Friedemann Smith, C., Whitaker, K. L., Winstanley, K. & Wardle, J. Smokers are less likely than non-smokers to seek help for a lung cancer ‘alarm’ symptom. Thorax 71, 659–661 (2016).

van Os, S. et al. Lung cancer symptom appraisal, help-seeking and diagnosis - rapid systematic review of differences between patients with and without a smoking history. Psycho-Oncol. 31, 562–576 (2022).

Sele Sætre, L. M. et al Health literacy and healthcare seeking with lung cancer symptoms among individuals with different smoking statuses: a population-based study. 2024;2024:7919967.

Saab, M. M. et al. Primary healthcare professionals’ perspectives on patient help-seeking for lung cancer warning signs and symptoms: a qualitative study. BMC Prim. care 23, 119 (2022).

Saab, M. M. et al. A systematic review of interventions to recognise, refer and diagnose patients with lung cancer symptoms. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 32, 42 (2022).

Sætre, L. M. S., Balasubramaniam, K., Søndergaard, J. & Jarbøl, D. E. Smoking status, symptom significance and healthcare seeking with lung cancer symptoms in the danish general population. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 3 (2025).

Rasmussen, S. et al. The danish symptom cohort: questionnaire and feasibility in the nationwide study on symptom experience and healthcare-seeking among 100 000 individuals. Int. J. Fam. Med. 2014, 187280 (2014).

Sætre, L. M. S. et al. Revisiting the symptom iceberg based on the danish symptom cohort – symptom experiences and healthcare-seeking behaviour in the general danish population in 2022. Heliyon 10, e31090 (2024).

Pedersen, C. B. The danish civil registration system. Scand. J. Public. Health 39, 22–25 (2011).

Pedersen, K. M., Andersen, J. S. & Søndergaard, J. General practice and primary health care in denmark. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med.: JABFM 25(Suppl 1), S34–S38 (2012).

Jakobsen, E., Rasmussen, T. R. & Green, A. Mortality and survival of lung cancer in Denmark: results from the danish lung cancer group 2000–2012. Acta Oncologica 55(sup 2), 2–9 (2016).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 63, 737–745 (2010).

Jensen, H. A. R., Ekholm, O., Davidsen, M. & Christensen, A. I. The Danish health and morbidity surveys: study design and participant characteristics. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 19, 91 (2019).

Lauridsen, G. B. et al. Exploring GPs’ assessments of their patients’ cancer diagnostic processes: a questionnaire study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 73, e941–e948 (2023).

Bradley, S. H., Kennedy, M. P. T. & Neal, R. D. Recognising lung cancer in primary care. Adv. Ther. 36, 19–30 (2019).

Smith, L. et al. Trends and variation in urgent referrals for suspected cancer 2009/2010–2019/2020. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 72, 34–37 (2022).

Schmidt, M. et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin. Epidemiol. 7, 449–490 (2015).

Agency for Digital Government. Fritagelse for Digital Post (Excemption from Digital Mail) 2023 [Available from: https://www.borger.dk/internet-og-sikkerhed/digital-post/fritagelse-fra-digital-post.

Danish Health Authority. Registration in the National Danish Health Register. Copenhagen: The Danish Health Authority; 2019.

Williamson, T. J., Riley, K. E., Carter-Harris, L. & Ostroff, J. S. Changing the language of how we measure and report smoking status: implications for reducing stigma, restoring dignity, and improving the precision of scientific communication. Nicotine Tob. Res. 22, 2280–2282 (2020).

Borg, M., Hilberg, O., Andersen, M. B., Weinreich, U. M. & Rasmussen, T. R. Increased use of computed tomography in Denmark: stage shift toward early stage lung cancer through incidental findings. Acta oncologica 61, 1256–1262 (2022).

Guldbrandt, L. M., Fenger-Grøn, M., Folkersen, B. H., Rasmussen, T. R. & Vedsted, P. Reduced specialist time with direct computed tomography for suspected lung cancer in primary care. Dan. Med. J. 60, A4738 (2013).

Andersen, R. S., Høybye, M. T. & Risør, M. B. Expanding medical semiotics. Med. Anthropol. 43, 91–101 (2024).

Singh, H. et al. Overdiagnosis: causes and consequences in primary health care. Can. Fam. Physician 64, 654–659 (2018).

Holland, K., McGeoch, G. & Gullery, C. A multifaceted intervention to improve primary care radiology referral quality and value in canterbury. N. Zealand Med. J. 130, 55–64 (2017).

Wiering, B., Lyratzopoulos, G., Hamilton, W., Campbell, J. & Abel, G. Concordance with urgent referral guidelines in patients presenting with any of six ‘alarm’ features of possible cancer: a retrospective cohort study using linked primary care records. BMJ Qual. Saf. 31, 579–589 (2022).

Hardy, V. et al. Role of primary care physician factors on diagnostic testing and referral decisions for symptoms of possible cancer: a systematic review. BMJ open. 12, e053732 (2022).

Malvang, L. B., Trolle, C., Rasmussen, T. R. & Hyldgaard, C. Decision support to general practice in choice of chest imaging for patients with pulmonary symptoms. Dan. Med. J. 70, A12220769 (2023).

Yakubovich K. Clinical decision-making theories. Annals of Innovation in Medicine. 1, 3–7 (2023).

Croskerry, P. From mindless to mindful practice-cognitive bias and clinical decision making. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 2445–2448 (2013).

Bate, L., Hutchinson, A., Underhill, J. & Maskrey, N. How clinical decisions are made. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74, 614–620 (2012).

Guldbrandt, L. M., Møller, H., Jakobsen, E. & Vedsted, P. General practice consultations, diagnostic investigations, and prescriptions in the year preceding a lung cancer diagnosis. Cancer Med. 6, 79–88 (2017).

Singh, H., Schiff, G. D., Graber, M. L., Onakpoya, I. & Thompson, M. J. The global burden of diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 26, 484–494 (2017).

Croskerry, P. Adaptive expertise in medical decision making. Med. Teach. 40, 803–808 (2018).

Singh, H. et al. Exploring situational awareness in diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 21, 30–38 (2012).

Harris, M. et al. How European primary care practitioners think the timeliness of cancer diagnosis can be improved: a thematic analysis. BMJ open. 9, e030169 (2019).

Panunzio, A. & Sartori, P. Lung cancer and radiological imaging. Curr. Radiopharm. 13, 238–242 (2020).

Bradley, S. H. et al. Sensitivity of chest X-ray for detecting lung cancer in people presenting with symptoms: a systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract.: J. R. Coll. Gen. Practitioners 69, e827–e835 (2019).

Mitchinson, L. et al. Clinical decision-making on lung cancer investigations in primary care: a vignette study. BMJ open. 14, e082495 (2024).

Sheringham, J. et al. Variations in GPs’ decisions to investigate suspected lung cancer: a factorial experiment using multimedia vignettes. BMJ Qual. Saf. 26, 449–459 (2017).

Kostopoulou, O. et al. Referral decision making of general practitioners: a signal detection study. Med. Decis. Mak. 39, 21–31 (2019).

Dima, S., Chen, K. H., Wang, K. J., Wang, K. M. & Teng, N. C. Effect of comorbidity on lung cancer diagnosis timing and mortality: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 1252897 (2018).

Kaushal, A. et al. The role of chronic conditions in influencing symptom attribution and anticipated help-seeking for potential lung cancer symptoms: a vignette-based study. BJGP Open. 4, bjgpopen20X101086 (2020).

Bradley, S. H. et al. Estimating lung cancer risk from chest X-ray and symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract.: J. R. Coll. Gen. Practitioners 71, e280–e286 (2021).

Lykkegaard, J., Olsen, J. K., Wehberg, S. & Jarbøl, D. E. The durability of previous examinations for cancer: Danish nationwide cohort study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 42, 246–253 (2024).

Hippisley-Cox, J. & Coupland, C. Identifying patients with suspected lung cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br. J. Gen. Pract.: J. R. Coll. Gen. Practitioners 61, e715–e723 (2011).

Nicholson, B. D. et al. Multi-cancer early detection test in symptomatic patients referred for cancer investigation in England and Wales (SYMPLIFY): a large-scale, observational cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 24, 733–743 (2023).

Ly, D. P., Shekelle, P. G. & Song, Z. Evidence for anchoring bias during physician decision-making. JAMA Intern. Med. 183, 818–823 (2023).

Virgilsen, L. F., Pedersen, A. F., Vedsted, P., Petersen, G. S. & Jensen, H. Alignment between the patient’s cancer worry and the GP’s cancer suspicion and the association with the interval between first symptom presentation and referral: a cross-sectional study in Denmark. BMC Fam. Pract. 22, 129 (2021).

Harris, M. et al. Primary care practitioners’ diagnostic action when the patient may have cancer: an exploratory vignette study in 20 European countries. BMJ open. 10, e035678 (2020).

Dunn, B. K., Woloshin, S., Xie, H. & Kramer, B. S. Cancer overdiagnosis: A challenge in the era of screening. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2, 235–242 (2022).

Andersen, R. S. & Tørring, M. L. (eds). Cancer Entangled: Acceleration, Anticipation and The Danish State, 192 (Rutgers University Press, 2023).

Elnegaard, S., Pedersen, A. F., Sand Andersen, R., Christensen, R. D. & Jarbøl, D. E. What triggers healthcare-seeking behaviour when experiencing a symptom? results from a population-based survey. BJGP Open. 1, bjgpopen17X100761 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank Maria Storsveen, MSc, for statistical support and guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS, KB, DJ, SW and JS participated in the design of the study and collected the survey data. LS, KB, DJ, SW and CBL were a part of the conceptualisation of the present study. LS did the statistical analyses and wrote the original draft of the paper. All authors have contributed to the interpretation of the data and the further development of the paper. All authors have read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sætre, L.M.S., Balasubramaniam, K., Wehberg, S. et al. Changes in diagnostic evaluation of patients with lung cancer symptoms. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 35, 59 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00464-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-025-00464-4