Abstract

The nature of dark matter is a fundamental puzzle in modern physics. A major approach of searching for dark matter relies on detecting feeble noise in microwave cavities. However, the quantum advantages of common quantum resources such as squeezing are intrinsically limited by the Rayleigh curse—a constant loss places a sensitivity upper bound on these quantum resources. In this paper, we propose an in situ transient control to mitigate such Rayleigh limit. The protocol consists of three steps: in-cavity quantum state preparation, axion accumulation with tunable time duration, and measurement. For the quantum source, we focus on the single-mode squeezed state (SMSS), and the entanglement-assisted case using signal-ancilla pairs in two-mode squeezed state (TMSS), where the ancilla does not interact with the axion. From quantum Fisher information rate evaluation, we derive the requirement of cavity quality factor, thermal noise level and squeezing gain for quantum advantage. When the squeezing gain becomes larger, the optimal axion accumulation time decreases, which reduces loss and mitigates the Rayleigh curse—i.e., the quantum advantage increases with the squeezing gain. Overall, we find that TMSS is more sensitive in the low-temperature limit. In the case of SMSS, as large gain is required for an advantage over vacuum, homodyne detection is sufficient to achieve optimality. Whereas, for TMSS, anti-squeezing and photon counting is optimal. Thanks to recent advances in magnetic field-resilient in-cavity squeezing and rapidly coupling out for photon counting, the proposed protocol is compatible with axion detection scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microwave quantum engineering offers unprecedented quantum control1,2, facilitating broad applications in quantum computing and quantum sensing. This capability enables high-fidelity state preparation, such as the creation of squeezed states, Fock states, and Gottesman–Kitaev–Preskill state3,4, and nontrivial detection strategies, such as the counting of individual microwave photons. Microwave photon counting, which can be implemented in situ1 or for traveling photons5,6,7, is crucial for quantum sensing and has gained recent prominence as a vital technology for precision measurements in high energy and particle physics8,9.

A notable example where quantum techniques are expected to markedly impact fundamental physics10 is the search for new particles beyond the standard model, such as the axion, a promising dark matter (DM) candidate11,12,13,14. Photon counting has been considered for quantum-enhanced DM searches with cooled microwave cavity receivers15,16. In axion DM searches, a cavity is immersed in a strong magnetic field (thus precluding the use of in-cavity Josephson-junction-based superconducting devices), inducing axion-to-photon conversion at an extremely feeble rate. The goal is to detect a faint excess of photons amidst the weak thermal background of the cooled cavity.

Photon counting is advantageous as it allows for bypassing the vacuum noise inherent to linear detectors15,17,18. Recently, photon counting was performed in situ for a dark photon DM search by ref. 19 and on traveling microwaves for an axion DM search by ref. 20. The quantum-enhanced sensitivity is remarkable in these setups, with Fisher information enhancements over linear detection strategies scaling as 1/NT, where NT is the residual thermal background. (For reference, NT ~10−4 for a 6 GHz cavity at 40 mK.) Nevertheless, the systems of refs. 19,20 operate as passive receivers with measurement bandwidths that are ultimately limited by the linewidth of the microwave cavity, thus restricting the search speed for DM candidates.

The ability to engineer quantum probes for active sensing—i.e., stimulating the cavity—provides an extra degree of utility. Squeezing is known to improve the detection bandwidth for linear (homodyne) detectors without sacrificing sensitivity16,21,22,23; a concept that can be further extended to a quantum sensor network24. However, the performance of linear detectors is very limited even when enhanced with squeezing: it requires larger than 30 dB of squeezing for a homodyne scheme to match a passive scheme based on photon counting25. Fortunately, replacing homodyne with photon-counting, squeezing is also capable of improving the measurement bandwidth of photon-counting schemes without sacrificing sensitivity. Indeed, in the absence of loss, a squeezed state photon-counting receiver was proven optimal for noise sensing, when the phase-sensitive amplification is applied before photon-counting25,26. However, it was subsequently shown that the squeezed state receiver can be quite sensitive to cavity loss25,27, and therefore limited by practical constraints.

To mitigate the vulnerability to loss, ref. 25 proposed an entanglement-assisted receiver based on two-mode squeezing and photon counting. In that setup, a signal mode is entangled with an idler mode, the idler is stored in a separate high-Q cavity, and photon counting is implemented on the signal (see Fig. 1b). With perfect idler storage, this configuration was shown to be quantum optimal, predicting a quantum-enhanced scan rate beyond all passive sensing configurations. However, there spectral photon counter (capable of counting the photons in each frequency bin) is assumed, which is beyond the capability of near-term devices. Moreover, when taking the idler storage cavity loss into consideration, the performance is still cursed by the Rayleigh limit—ref. 27 shows that such Gaussian sources are all subject to a limit set by loss, lowering the performance below the diverging 1/NT advantage from passive receivers with photon counting when noise NT is low. We note that the conventional Rayleigh curse states that the mean square error MSE(σ) of estimating the standard deviation σ goes to infinity when σ → 027, while here we consider estimating the variance σ2 of which the mean square error MSE(σ2) is lower bounded by a constant when σ2 → 0. This asymptotic behavior is consistent because \({\rm{MSE}}({\sigma }^{2})={({\partial }_{\sigma }{\sigma }^{2})}^{2}{\rm{MSE}}(\sigma )=4{\sigma }^{2}{\rm{MSE}}(\sigma )\). Therefore, the way towards large quantum advantage seems to rely on non-Gaussian-state engineering, which generally requires Josephson-junction-based superconducting microwave cavities that are incompatible with magnetic field in axion haloscopes28.

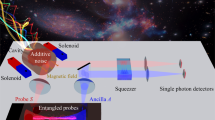

a Squeezing-enhanced protocol using single-mode squeezed state (SMSS); b Entanglement-assisted protocol using two-mode squeezed state (TMSS). The quantum source states are generated from thermal background states of mean photon number NT by single-mode squeezer \({\mathcal{S}}(G)\) (or two-mode squeezer \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}(G)\)) of quadrature squeezing gain G. Then the dark matter of per-mode mean photon number NA couples into the cavity (homogeneously to each quadrature) and accumulates for waiting time T, while the in-cavity mode suffers intrinsic loss at rate Γ and gets mixed with an environment mode of thermal background photon number NT. After the accumulation, the optimal quantum measurement, which is known to be the nulling receiver25, is made over the in-cavity mode, which composes first anti-squeezing \({{\mathcal{S}}}^{-1}({G}^{\star })\) (or two-mode anti-squeezing \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{2}^{-1}({G}^{\star })\)) of optimized gain G⋆ and then rapidly coupling-out for photon counting. The information carried in the ancilla is extremely weak; thus, the idler photon detector (colored in gray) is optional. PD: number-resolving photon detector. c Mitigation of Rayleigh curse at NT ≪ 1. The quantum advantages over the vacuum-state T-optimized quantum Fisher information rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{{\rm{VAC}}\star }\) of T-optimized cases (solid lines) are compared with the T-fixed cases (dot-dashed lines) where T is fixed to vacuum optimum TVAC⋆, for SMSS (blue) and TMSS (red), respectively. Asymptotic predictions Eqs. (10, 16) assuming G → ∞, NT ≪ 1, ΓτA ≪ 1 are provided in dashed lines for SMSS (purple) and TMSS (orange). Squeezing gain G is numerically optimized. Cavity parameters: ΓτA = 10−4, ΓidlerτA = 10−8.

In this paper, we propose an axion DM search protocol with in situ transient control to mitigate the effect of Rayleigh curse27 in DM detection, without relying on any non-Gaussian source. In particular, the proposed protocol completely circumvents the Rayleigh curse when the axion signal is fully incoherent. Our proposal prepares the quantum probe in a cavity, accumulates the axion signal in a cavity, and detects the accumulated signal, e.g., by rapidly coupling out the cavity field to a transmission line and counting itinerant photons by, e.g., fast tuning of the base frequency29, as shown in Fig. 1. The in-cavity probe preparation avoids injection losses from coupling traveling-wave microwave quantum states with the signal and idler cavities. Furthermore, we formulate the transient cavity dynamics, which allows us to optimize the accumulation time. We find the optimal accumulation time decreases with increasing squeezing strength of the quantum probe, and eventually diminishes if the axion coherence time is negligible. Therefore, the overall cavity loss, which is proportional to the accumulation time, can be reduced by increasing the squeezing strength, thereby the Rayleigh curse is mitigated.

We find neat qualitative benchmarks for next-generation axion DM searches that are capable of leveraging a swath of quantum resources (including inter-cavity entangling operations, bandpass-limited photon counters, and high-Q cavities) in unison. To quantify the advantage, we derive quantum precision limits of the single-mode squeezed state (SMSS) source and the entanglement-assisted two-mode squeezed state (TMSS) source, which are easily accessible Gaussian-state sources30,31, and show that they are achievable by the nulling receiver (anti-squeezing followed by photon counting) in the low-temperature limit NT → 0. The entanglement-assisted TMSS protocol enjoys better robustness than the SMSS protocol. In the case of SMSS, as a quantum advantage over vacuum requires a large gain GNT ≳ 1, homodyne can, in fact, already achieve close-to-optimal performance, not requiring photon counting. It is noteworthy that such robustness against loss rate circumvents (but does not violate) the Gaussian-state Rayleigh curse predicted in ref. 27, because the transient cavity dynamics here is no longer a fixed quantum channel in ref. 27, and the overall loss here can be suppressed by optimizing waiting time. Our protocol requires the generation of squeezing in large magnetic fields, which can be done using a kinetic inductance parametric amplifier (KIPA)32,33,34 with single-mode squeezing gain up to 8 dB in current experimental conditions. For practical application, we demonstrate significant advantages at feasible parameter setups for near-term devices. In contrast, non-Gaussian-state preparation typically requires Josephson-junction-based superconducting elements within the signal cavity, which are forbidden in an axion search due to the strong magnetic field.

Results

Overview

To detect axion DM, a microwave haloscope (a microwave cavity in a strong magnetic field13) converts the DM field signals to feeble excess microwave power in the cavities. Therefore, DM search in such haloscopes becomes a noise-sensing problem in the weak signal limit. In this regard, the Rayleigh limit curses the performance of DM search27,35 in the presence of loss: for any active detector with a Gaussian source subject to loss on all modes, the sensitivity measured by quantum Fisher information (QFI) demonstrates saturation to a constant value. For example, given a thermal loss channel with loss 1 − η and additive noise NB, an infinitely squeezed single-mode squeezed state (SMSS) generated from a thermal state of photon number NT, has the QFI of noise parameter NB saturated to (See the Supplementary Information of ref. [25] for Gaussian-state statistics and ref. [36] for Gaussian-state QFI calculation.)

when NB = (1 − η)NT is at the same temperature as the input, which is limited to 2/(1−η)2 in the weak noise limit. From quantum Cramer–Rao bound, this limits the estimation precision of any additional noise—the means-square error \({\Delta }^{2}{N}_{B}\ge 1/{{\mathcal{J}}}_{{\rm{SV}}}\). While for a passive detector with vacuum source, the performance in terms of QFI is divergent, \({{\mathcal{J}}}_{{\rm{V}}\;{\rm{L}}}\sim 1/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\,\gg\,{{\mathcal{J}}}_{{\rm{SV}}}\), when the noise NT is small. This casts a shadow on the promise of any quantum advantage. One way out of the dilemma seems to be reducing loss: consider a short duration of detection such that the microwave cavities do not induce much loss. However, a shorter duration of detection also limits the signal accumulation from axion DM conversion and it is not clear if any quantum advantage can be achieved. In addition, the finite coherence time of axion DM becomes important in such a scenario and requires a systematic treatment.

In this work, we perform a complete analyses of such a strategy and show that indeed by optimally tuning the accumulation time in a cavity, the Rayleigh curse can be largely mitigated. To consider a finite signal accumulation, we first refine the physical model of the dark matter field. We investigate the continuous-time model of random-phase dark matter field, and derive the time evolution of its coupling into the cavity mode in the Heisenberg picture: after interaction time T, contributed from a virtual in-cavity dark matter mode aA(T), a thermal bath mode aB(T), and the initial cavity mode A(0), the final cavity mode A(T) is

where \(\eta (T)=\exp -\Gamma T\) is the transmissivity of the cavity mode, Γ is the loss rate of the cavity, and γA ≪ Γ is the coupling rate of the axion field. The full derivation is in Methods. The photon number of aA(T) is proportional to the axion occupancy number NA as \(\langle {a}_{A}^{\dagger }{a}_{A}\rangle ={N}_{A}\cdot g(T,\Gamma ,{\omega }_{A},{\tau }_{A}),\) where g is a dimensionless coupling gain from the physical axion mode outside cavity to the in-cavity mode, which depends on the axion frequency detuning and coherence time ωA, τA (for full formula see Supplementary Note 1). Here, a phase jump in the axion mode happens probabilistically, which yields a Lorentzian lineshape in the steady-state limit37, instead of a simple additive noise model as in refs. 25,27. The phase jump leads to a finite coherence time τA (bandwidth 1/τA) for the axion and modulates the axion coupling gain g. Such a quantitative model of temporal dynamics allows us to consider the optimization of signal accumulation time rigorously.

With the theoretical model refined, we consider possible improvements to the squeezing-based detection protocol. As the coupling loss is the major obstacle that degrades the squeezing advantage, we consider the in-cavity protocol with the state generation conducted in the cavity, instead of an input-output protocol that injects external quantum resources through a transmission line as proposed in ref. 25. The conceptual schematic is shown in Fig. 1. We consider two choices of quantum sources: (a) squeezing-enhanced protocol using SMSS and (b) entanglement-assisted protocol using TMSS. The entangled ancilla does not interact with the dark matter, but it benefits the detection by increasing the purity of the final state of the signal mode. In both cases, the quantum sources are generated in cavity, then interact with the dark matter field for an optimized accumulation (or waiting) time T. Finally, the cavity mode is processed by anti-squeezing, then rapidly coupled out for detection. Such arrangement allows for axion search where the detection cavity is bathed in a strong magnetic field, for which we provide a detailed explanation at the end of this section.

In this paper we consider the occupancy number NA of the axion dark matter as the parameter of interest. We first focus on narrowband performance, assuming the frequency of the dark matter signal is known. At the end of this paper, we discuss broadband performance assuming the frequency of the dark matter signal is a priori unknown, and the signal must be searched for. As the total QFI \({\mathcal{K}}(T)\) increases with the signal accumulation time T, in both cases, we consider the QFI rate \({\mathcal{R}}\equiv {\mathcal{K}}(T)/T\) as the figure of merit. The requirement of quantum advantage for the in-cavity detection protocol considered in this work can be formulated as the following.

Result 1

For any small but fixed thermal noise NT, fixed cavity loss rate Γ, the detection of the axion signal can be quantum enhanced over the vacuum limit by a single-mode squeezed state (SMSS) source of quadrature squeezing gain G when

where \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\propto {\tau }_{A}\), \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\propto 1/\Gamma\) are the quality factors of axion signal and the cavity.

For the two-mode squeezed state (TMSS), of EPR quadrature squeezing gain G, which is defined for quadrature variances analogous to the SMSS, the quantum advantage requirement is

for lossy idler storage \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{idler}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\ll 1/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\) where \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{idler}}}\) is the idler storage cavity quality factor. With an ideal idler \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{idler}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\to \infty\), the quantum advantage requirement reduces to

In the limit of incoherent signal \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\to 0\) (i.e., τA → 0) and large squeezing G ≫ 1, quantum advantage can always be achieved by tuning a proper signal accumulation time, therefore circumventing the Rayleigh limit. In fact, the advantage is infinite \(\propto {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\to \infty\) with unlimited G → ∞. This is because a smaller accumulation time reduces the overall loss 1 − η(T) ≃ ΓT (at small T ≪ 1/Γ), and indeed we find the optimal accumulation time T⋆ → τA → 0 at the limit of G → ∞, τA → 0 as shown later in Asymptotic Regimes of Squeezing Gain G. For finite-value of parameters, the Rayleigh limit is mitigated, as we show in Fig. 1c. We plot the G-optimized quantum advantages over vacuum-state QFI rate using SMSS (blue solid) and TMSS (red solid) respectively. With a small signal coherence time ΓτA = 10−4, by optimizing T we achieve an advantage ≃ 1/ΓτA. In contrast, with fixed T, i.e., fixed loss, we observe the Rayleigh curse (dashed lines): for any G, the squeezed-state QFI rate never surpasses the vacuum-state QFI rate for small NT. Here, the TMSS demonstrates a much larger quantum advantage than SMSS, almost independent of NT, while the finite idler loss Γidler = 10−4Γ begins to limit such advantage as NT decreases below 10−4. It is remarkable that, when squeezing G and the relative quality of idler memory \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{idler}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\) are fixed, the quantum advantage decays with decreasing NT, which is consistent with the Rayleigh curse predicted in ref. 27.

In terms of experimental requirements, while cavity quantum electrodynamics (QED) techniques for state preparation requires Josephson-junction-based superconducting conditions that is incompatible with magnetic field, recent experimental efforts have demonstrated magnetic field-resilient in-cavity squeezing based on kinetic inductance parametric amplifier (KIPA)32,33,34, which paves the way for in-cavity squeezing and anti-squeezing in the presence of strong magnetic field. In comparison, non-Gaussian states such as Fock state28 or GKP states3,27 generally requires Josephson-junction-based superconducting cavity that is incompatible with magnetic field. By rapidly coupling the signal out at the overcoupling limit, the photon counting can be implemented outside the cavity using Josephson photon-number amplifier38 without loss of information. It is noteworthy to point out that in the case of SMSS, as quantum advantage over vacuum requires a large gain GNT ≳ 1 in Ineq. (3), homodyne can, in fact, already achieve close-to-optimal performance, not requiring photon counting.

Current axion DM searches (wherein the spectral scan rate is the figure of merit39) typically operate in the regime \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\lesssim 1\)15, with \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}} \sim 1{0}^{6}\). This constrains discovery potential and, crucially, precludes further enhancements to be gained from photon-counting schemes via quantum probes, in accordance with Ineq. (5). However, this paradigm is beginning to change20,40 (i.e., \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}} \sim {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\)) setting the stage for quantum-enhanced stimulated axion DM searches.

In the TMSS protocol, the assumption of a good quantum memory for idler storage is plausible for an axion DM search because the signal cavity is typically copper (or, more generally, non-superconducting), and the idler storage cavity—which need not be bathed in a strong magnetic field—can be superconducting. Indeed, recent progress on coupling two cavities, e.g., in refs. 41,42, demonstrates similar capabilities necessary for an entanglement-assisted scheme dedicated to axion DM searches.

Due to the advantage requiring \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\,\gtrsim\,{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\), the scan-rate is approximately the same as the on-resonance axion signal case, and therefore all the results generalize to the scan-rate as well, which we will elaborate in broadband performance in scan-rate.

We formulate the transient in-cavity dynamics and detection in Methods. A summary of notations and parameters is provided in Table 1.

Quantifying measurement sensitivity

Our goal is to estimate the per-mode axion mean occupation number NA, based on measurement on the final state A(T). To enhance the performance, we propose to engineer the input state as SMSS and TMSS (joint with ancilla), which are compatible with the strong magnetic field32. In this section, we analyze the performance of the protocols in terms of sensitivity. We begin with the evaluation of the QFI \({\mathcal{K}}\) given SMSS and TMSS input, which provide an asymptotically achievable performance for all possible measurements on the final state, and then address the measurement scheme to achieve the bound. As axion signals are accumulated within a finite time T, we further convert the QFI results into the QFI rate \({\mathcal{R}}\equiv {\mathcal{K}}(T)/T\) as the figure of merit in choosing the optimal system setup. Furthermore, for each choice of quantum state, we optimize the waiting time T and define the T-optimized QFI rate as \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{\star }\equiv \mathop{\max }\limits_{T}{\mathcal{R}}(T)\), with the corresponding optimal waiting time \({T}^{\star }\equiv {{\rm{argmax}}}_{T}{\mathcal{R}}(T)\).

First, we provide analyses for the classical benchmark of passive detectors, where vacuum input (subject to thermal photon NT) and homodyne detection are adopted (resulting in the “standard quantum limit” for noise estimation21). For the axion signal at detuning ωA and waiting time T, we can solve the QFI \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{V\; AC-HOM}}}({\omega }_{A},T)\) analytically. However, as the full formula is lengthy (see Supplementary Note 1), we present the simplified on-resonance (ωA = 0) Fisher information

As homodyne is not the optimal measurement for vacuum input, we also evaluate the QFI of the in-cavity protocol using vacuum state as \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{V\; AC}}}({\omega }_{A},T)\) in Supplementary Note 1, which is known to be achievable by photon counting measurement25 (see Fig. 6). We use the vacuum-state QFI as a benchmark for the classical sources and demonstrate quantum advantages over it with squeezed sources. Given detuning ωA, the vacuum QFI is

where \({n}_{A}^{{\rm{eff}}}(T)\) is the effective in-cavity axion photon number Eq. (28). Plugging in Eq. (28), the on-resonance vacuum QFI is

At the asymptotic limit of incoherent axion signal ΓτA → 0, we can show that the on-resonance vacuum-state QFI rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{VAC}}}({\omega }_{A}=0,T)\equiv {{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{VAC}}}({\omega }_{A}=0,T)/T\) is optimized at \({T}_{{\rm{VAC}}}^{\star }\simeq [-{W}_{-1}(-\frac{1}{2\sqrt{e}})-\frac{1}{2}]/\Gamma \approx 1.256/\Gamma\), where W−1(x) is the Lambert W function, which gives the -1th solution of w for equation x = wew. Such an asymptotic solution of \({T}_{{\rm{V\; AC}}}^{\star }\) can be understood as the following. Starting from time zero, the axion signal first coherent accumulates, and due to the coherence, one prefers to increase T ≳ τA. Afterward, axion signals can be modeled as incoherent additive noise with mean occupation number in Eq. (29), which increases with T linearly, ∝ TNA when T ≳ τA. However, due to the weak coupling γA ≪ 1, \({n}_{A}^{{\rm{eff}}}\,\ll\,{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\), and the overall noise is still dominated by the thermal noise NT. Therefore, the QFI for estimating NA is ∝ T2/NT(NT + 1), where T2 comes from change of variable. This leads to a linear increase of QFI rate with T until the cavity loss comes into play when T ~ 1/Γ and stops increasing thereafter.

For the quantum squeezed sources, we denote the QFIs using SMSS and TMSS as \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{SMSS}}}({\omega }_{A},T)\), \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}({\omega }_{A},T)\). We derive and put the formulas of \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{SMSS}}}({\omega }_{A},T)\) and \({{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}({\omega }_{A},T)\) in Supplementary Note 1 as they are too lengthy. Below we provide asymptotic analyses and numerical evaluations to support Result 1.

Asymptotic regimes of squeezing gain G

We expect the performance to be enhanced by squeezing, while at low squeezing gain G → 1, the squeezed state can perform even worse than the vacuum state in noise sensing since the loss destroys the purity of the squeezed states and induces extra noise, as predicted in refs. 25,27. Thus, we are interested in the break-even threshold GTH where \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{SMSS/TMSS}}}^{\star }({G}_{{\rm{TH}}})={{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{V\; AC}}}^{\star }\) overcomes the optimal passive detector of vacuum photon counting. Prior results25 indicate that \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\) may be much larger than unity while \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\) may be close to unity. On the other hand, we expect the advantage from squeezing bounded at the limit of G → ∞, due to imperfections of the system and finite axion coherence time. Thus we are also interested in the saturation point GSAT. In sum, there are two asymptotic regimes of interest for both SMSS and TMSS:

-

sufficiently large gain G but not saturated, i.e. GTH ≪ G ≪ GSAT;

-

saturated gain G → ∞.

The optimal waiting time T⋆(G) decreases as G increases, because the quantum advantage is vulnerable to loss 1 − η(T) ∝ T. For the same reason, T⋆ also depends on Γ, NT, while we focus on its dependence on G here as G is tunable. In the strong squeezing regime (G ≳ GSAT), the waiting time converges to the axion coherence time, \({T}^{\star }(G\to \infty )\to {\tau }_{A}^{+}\), because the axion coherence is concentrated within τA thus T⋆ ≳ τA is required to sufficiently extract the axion coherence by coherent accumulation of duration T⋆ (see Supplementary Note 2).

Single-mode squeezing

In Fig. 2, we explore the on-resonance advantage of the SMSS source over the vacuum under various squeezing gain, G, and background thermal noise, NT. When \(G\le {G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\) is small, we see the performance of SMSS is worse than vacuum limit, until the condition \(G\,\gtrsim\,{G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\) is satisfied, as shown in subplot (a). After crossing the threshold, the advantage of SMSS grows linearly with gain G till saturation at \({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\). We can obtain the analytic results of \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\simeq 1/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\) and \({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\simeq 2\sqrt{2{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}/\Gamma {\tau }_{A}\) from asymptotics (see below), which agree well with the numerical results as indicated by the two triangle points in Fig. 2a.

Performance (a, b) versus squeezing gain G with NT = 10−2 fixed; c, d versus thermal background photon number NT with G = 40 dB fixed. a, c Advantage (in dB unit) of T-optimized quantum Fisher information rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{\star }\equiv \mathop{\max }\limits_{T}{\mathcal{J}}(T)/T\) over vacuum state input; b, d optimal waiting time T⋆ normalized by axion coherence time τA (in log10 scale). Solid lines: T numerically optimized; Dot-dashed lines: asymptotic prediction with \(T=2\sqrt{2{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}{\tau }_{A}/\Gamma {\tau }_{A}G\). Purple dashed lines: asymptotic prediction of linear advantage Eq. (9) assuming non-saturated strong squeezing GSAT ≫ G ≫ GTH, NT ≪ 1, ΓτA ≪ 1. In subplot (a, b) we mark GTH (≃20 dB here) and GSAT (≃55 dB here) by right-pointing triangle and left-pointing triangle respectively. Gray dashed lines: 0dB advantage and G-saturated advantage Eq. (10). Cavity parameters: ΓτA = 10−8.

To understand the above behavior, we first perform asymptotic analyses to obtain the asymptotic optimal waiting time for \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\,\ll\,G\,\ll\,{G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\) where there is a quantum advantage. Assuming the above asymptotic formula of \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\) and \({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\), we find that the on-resonance SMSS QFI rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{SMSS}}}({\omega }_{A}=0,T)\equiv {{\mathcal{K}}}_{{\rm{SMSS}}}({\omega }_{A}=0,T)/T\) is optimized at \({T}_{{\rm{SMSS}}}^{\star }\simeq 2\sqrt{2{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}/\Gamma G\), in the incoherent axion and low noise limits, ΓτA → 0, NT → 0. The asymptotic optimal waiting time is verified in the numerical evaluations in Fig. 2b, d. Compared with the vacuum result, we see that larger squeezing requires a shorter optimal waiting time, as squeezing is more sensitive to loss. This decrease of optimal waiting time saturates towards τA when \(G\,\gtrsim\,{G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\). By solving \({T}_{{\rm{SMSS}}}^{\star }={\tau }_{A}\simeq 2\sqrt{2{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}/\Gamma {G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\), we can obtain \({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\simeq 2\sqrt{2{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}/\Gamma {\tau }_{A}\), which is confirmed by the triangle point in Fig. 2a. On the other hand, a larger thermal background increases the optimal waiting time, as a thermal background makes the performance more tolerant to anti-squeezing noise. Note that the discontinuity in the waiting time is due to the competition between two local maximums, as we detail in Supplementary Note 3.

Under the asymptotic optimal waiting time, we can perform further asymptotics to confirm the numerical observations in Fig. 2a. First, when \({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\,\gg\,G\,\gg\,{G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\), we obtain the advantage over the vacuum state

which linearly grows with G. At the same time, Eq. (9) also confirms the threshold of advantage \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\simeq 1/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\). In Fig. 2c, we verify the scaling of advantage versus NT. Equation (9) indicates that in order for SMSS to provide a quantum advantage, we need GNT ≳ 1, which confirms the second part of Ineq. (3) in Result 1.

With \(G\ge {G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{SMSS}}}\) and optimal waiting time T⋆ = τA, the ultimate advantage of the on-resonance SMSS QFI rate over the vacuum QFI rate can be well approximated by

The result above then places a requirement for quantum advantage as NT/ΓτA ≳ 1. Considering the cavity quality factor \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\propto 1/\Gamma\) and axion quality factor, we obtain \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\,\lesssim\,{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\), which is the first part of Ineq. (3) in Result 1. Combining Eq. (9), we have obtained the condition of Ineq. (3) in Result 1.

Note that our physical model differs from the loss-fixed channel in ref. 27. As shown in Eq. (2) and Eq. (27), the interaction time T determines both the loss and the axion coupling gain into the cavity, thus the optimization of T is nontrivial and heterogeneous for different probe quantum state. Hence, each quantum advantage shown in this paper is a ratio of QFI rates optimized at different time, e.g., T = τA for SMSS and T = 1/Γ for vacuum in Eq. (10), and thus under different bosonic loss channels. In contrast, each ratio in ref. 27 is calculated under the same loss channel.

Two-mode squeezing

We first derive results for imperfect idler storage Γidler/Γ ≫ NT. For sufficiently large but not saturated G, i.e., \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\,\ll\,G\ll\,{G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\), we find that the on-resonance TMSS QFI rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}({\omega }_{A}=0,T)\) is optimized at

when ΓτA → 0 and NT → 0, as verified in Fig. 3b, d. Setting the waiting time saturating to the axion coherence time, \({T}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}^{\star }({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}})={\tau }_{A}\), we can solve the saturation gain

Similar to SMSS, the TMSS advantage over the vacuum state linearly grows with G as

We plot the predictions of linear growing advantage in dashed lines in Fig. 3a, c, which agree with the numerical evaluation well within \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\,\ll\,G\ll\,{G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\). When Γ = Γidler, as both cavities has the same loss, TMSS can be reduced to SMSS under balanced beamsplitter, and indeed we find the rate advantage for TMSS ~2.566GNT in Eq. (13), which is almost equal to that of SMSS in Eq. (9). From equation \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}(G={G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}})={{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{V\; AC}}}\) we solve the threshold gain \({G}_{{\rm{TH}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\simeq {[{N}_{{\rm{T}}}(1+\Gamma /{\Gamma }_{{\rm{idler}}})]}^{-1}\). When G approaches the saturation gain \({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}}^{{\rm{TMSS}}}\), the QFI rate is no longer represented by Eq. (13). Instead, asymptotic analyses at G → ∞ leads to

We plot the saturated advantage in the gray dashed line in Fig. 3a, which agrees with the numerical evaluations at large G. The results above enforce constraints for TMSS to be advantageous as NT/ΓidlerτA ≳ 1. Note that \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\propto 1/\Gamma\), \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\propto {\tau }_{A}\), we obtain \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\,\lesssim\,{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{idler}}}\), which is the first part of Ineq. (4) in Result 1. Combining it with Eq. (13), we obtain the condition of Ineq. (4) in Result 1.

Performance with lossy idler storage: a, b versus squeezing gain G, with NT = 10−2 fixed; c, d versus thermal background photon number NT, with G = 40 dB fixed. a, c Advantage (in dB unit) of T-optimized quantum Fisher information rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{\star }\equiv \mathop{\max }\limits_{T}{\mathcal{J}}(T)/T\) over vacuum state input; b, d optimal waiting time T⋆ normalized by axion coherence time τA (in log10 scale). Dashed lines: asymptotic predictions Eq. (13) assuming non-saturated strong squeezing GSAT ≫ G ≫ GTH, NT ≪ 1, ΓτA ≪ 1 (Here \(1.283(1+\frac{\Gamma }{{\Gamma }_{{\rm{idler}}}})=2.566\)). Dot-dashed lines: Asymptotic predictions on waiting time \(T=\frac{2\sqrt{{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}}{\Gamma G}\cdot \frac{\sqrt{1+{\Gamma }_{{\rm{idler}}}^{2}/{\Gamma }^{2}}}{1+{\Gamma }_{{\rm{idler}}}/\Gamma }\). Cavity parameters: ΓτA = 10−8, ΓidlerτA = 0.5 × 10−8.

For ideal idler storage Γidler/Γ ≪ NT, the optimal waiting time is \({T}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}^{\star }\simeq 2/G\Gamma\), the advantage is

In this case, both the optimal waiting time and the advantage do not depend on NT at all. By setting \({{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}(G={G}_{{\rm{TH}}})={{\mathcal{R}}}_{{\rm{V\; AC}}}\) and \({T}_{{\rm{TMSS}}}^{\star }({G}_{{\rm{SAT}}})={\tau }_{A}\), we solve the threshold gain GTH ≃ 1/0.321 and the saturation gain GSAT ≃ 2/ΓτA. This explains the saturation at G ~80 dB in Fig. 4a. The saturated advantage is independent on NT:

The results above enforce constraints for TMSS to be advantageous as NT/ΓidlerτA ≳ 1. Note that \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\propto 1/\Gamma\), \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\propto {\tau }_{A}\), we obtain \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}/{N}_{{\rm{T}}}\,\lesssim\,{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{idler}}}\), which is the first part of Ineq. (4) in Result 1. Combining it with Eq. (13), we obtain the condition of Ineq. (4) in Result 1.

The layout is identical to Fig. 3: a, b versus squeezing gain G, with NT = 10-2 fixed; c, d versus thermal background photon number NT, with G = 40 dB fixed. a, c Advantage (in dB unit) of T-optimized quantum Fisher information rate over vacuum state input; b, d optimal waiting time T⋆ normalized by axion coherence time τA (in log10 scale). Here the asymptotic predictions of advantage (dashed lines) and T (dot-dashed lines) are evaluated from Eq. (15) and \(T=\frac{2}{\Gamma G}\) respectively. Cavity parameters: ΓτA = 10−8, ΓidlerτA = 10−12.

Result 1 and mitigating the Rayleigh curse

While our asymptotic analyses have confirmed Result 1, here we provide a direct contour plot to show case how these conditions limit the region of quantum advantage for resonant detection, i.e., ωA = 0.

In Fig. 5, we plot the contours of advantage versus the dimensionless loss rate ΓτA and pre-squeezing thermal background NT for G = 20dB. In subplot (a), we consider the SMSS source, the advantage is limited to the good cavity regime ΓτA ≪ 1, and the advantage significantly degrades as the environment thermal noise decreases NT → 0. Indeed, we can see the conditions in Ineqs. (3) (red dashed) precisely captures the region of quantum advantage (red solid). By contrast, in subplot (c), the TMSS source shows an advantage extending to noiseless case NT ≪ 1, which is the regime of our interest in typical microwave haloscopes cooled to low temperatures. At the bottom left corner in subplot (c), we observe a rapid degradation of advantage, this is because the idler loss rate ΓidlerτA = 10−6 begins to be comparable to the signal loss rate ΓτA at this disadvantageous corner. To keep the advantage, we see that Γidler/Γ ≲ GNT is required. Indeed, the boundary of quantum advantage (red solid) is well captured by the Ineqs. (4) as indicated by the red dashed curves. The additional condition in Ineq. (5) also shows up on the top of subplot (c) as in this region, the idler storage cavity is close to ideal, compared to the sensing cavity. The optimal waiting time for both SMSS and TMSS are shown in subplots (b) and (d) correspondingly.

a, b SMSS performance advantage in comparison with the asymptotic quantum advantage requirement Result 1. a Quantum advantage (in dB unit, x (dB) = 10 \({\log }_{10}x\)) of T-optimized quantum Fisher information rate \({{\mathcal{R}}}^{\star }\) over vacuum state input versus various cavity linewidth Γ (normalized by axion linewidth 1/τA) and thermal background noise NT. The break-even thresholds of 0dB quantum advantage are marked in red solid curves, while the asymptotic predictions on them in Ineq. (3) are indicated in red dashed curves. b Optimal normalized waiting time T⋆/(1/Γ). c, d TMSS performance in comparison with Result 1, with a similar layout with subplot (a, b), where the asymptotic predictions on break-even thresholds are from Ineqs. (4, 5). For all four subplots G = 20 dB. For TMSS, ΓidlerτA = 10−6.

Remarkably, in the limit of incoherent axion τA → 0, the SMSS advantage \(\propto G\sqrt{{N}_{{\rm{T}}}}\) in Eq. (9) circumvents the Rayleigh curse in ref. 27, as we have stated in Result 1. The reason is that here the overall cavity loss is 1 − η(T) = 1 − e−ΓT, which is always negligible for any finite cavity loss rate Γ at the large gain G limit such that T ∝ 1/G → 0. This conclusion also holds for TMSS with the advantage in Eq. (13) not even affected by noise NT. For strong squeezing limit G → ∞, similarly both SMSS and TMSS advantages in Eqs. (10, 16) can be significant even at NT ≪ 1 with ΓτA → 0.

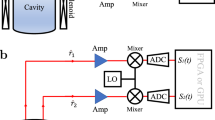

Measurement designs

With the input states and QFI rates in hand, we now proceed to analyze the measurement protocols. As shown in Fig. 6, we consider the linear homodyne measurement and the photon number counting measurement for the three inputs: vacuum, SMSS, and TMSS, respectively. For vacuum, we also consider heterodyne measurement as it has been found to yield a 3 dB advantage over homodyne when the environment is noisy. For SMSS and TMSS, we apply anti-squeezing S†, \({S}_{2}^{\dagger }\) respectively before photon counting to extract the quantum advantage from quantum coherence, which is known as nulling receiver25. As a benchmark, we also consider the homodyne measurement for SMSS and the Bell measurement (a balanced beamsplitter followed by two homodyne detectors) for the TMSS input43,44 Similarly, for each specific measurement, we adopt the same notation to denote the achievable classical Fisher information as \({\mathcal{K}}\) and the Fisher information rate \({\mathcal{R}}\).

Specifically, we plot the linear homodyne measurement (a, d, f), heterodyne measurement (b), and the photon number counting measurement (c, e, g), for the three inputs: vacuum (a–c), SMSS (d, e), and TMSS (f, g), respectively. All modes S and A are initially in vacuum (up to inevitable thermal noise due to limited cooling).

In Fig. 7, we plot the performance of each measurement and the corresponding numerically optimized waiting time. In subplot (a), we consider the low noise limit of NT = 0.01 and plot the QFI rate normalized by the vacuum homodyne QFI rate, versus different squeezing strength G. For the vacuum input, as no squeezing is involved, the QFI rate (black solid) has a constant advantage over the vacuum homodyne. At the same time, it is known that photon counting achieves this QFI rate. As we see in subplots (a) and (b), for the SMSS source, when G is small and NT is low, the SMSS-NULL detection (blue points) shows advantage over homodyne detection (blue dot-dash). However, SMSS only enjoy advantage over vacuum photon-counting when G is large, where we see homodyne detection provides the same QFI-achieving performance, similar to SMSS-NULL. This can be confirmed by asymptotic analyses in large G, and also agrees with the intuition that homodyne is optimal for states with large occupation number (as indicated by Ineq. (3) where GNT ≳ 1). Therefore, homodyne and SMSS21,25 provide a route to achieve quantum advantage without relying on photon counting in the large gain limit. On the other hand, the QFI of TMSS (red solid) can only be achieved by the TMSS-NULL (red points), while the homodyne-based TMSS-Bell measurement (red dot-dash) shows sub-optimal performance. In fact, TMSS-Bell has a similar performance to SMSS.

a, b Quantum advantage in Fisher information rate over the classical protocol using a vacuum-state source with homodyne measurement (VAC-HOM), with waiting time T optimized; c, d Optimal waiting time T⋆. a, c Plotted versus squeezing gain G in decibel unit, NT = 0.01; b, d Plotted versus noise NT in logarithmic scale, G = 10 dB. For all four cases, ΓτA = 10−4, ΓidlerτA = 10−6. Solid lines are independent of measurement. Dot-dashed lines are for conventional quantum measurements: SMSS-HOM, SMSS source with homodyne measurement; TMSS-Bell, TMSS source with Bell homodyne measurement43,44; VAC-HET, vacuum source with heterodyne measurement. Dots are for our measurement proposal: TMSS/SMSS-NULL, TMSS/SMSS source with nulling receiver measurement. For the nulling receiver, we choose the anti-squeezing gain G⋆ such that the support of the output state is the photon-number basis, which is asymptotically optimal at the limit NT → 049. For large G SMSS-HOM always achieves SMSS-QFI, verified by aymptotic analysis at G → ∞.

Broadband performance in scan-rate

In the section, we compare the in-cavity protocol proposed in this paper, with the input-output protocol analyzed in ref. 25. In ref. 25, the probe is first coupled into the cavity, then the in-cavity probe is driven by the axion signal; finally, the probe is coupled out of the cavity for measurement. In the input-output model, one has access to a continuous temporal output, which consists of TΔω/2π modes for observation T within a frequency bin of width Δω ≫ 1/T. In contrast, for the in situ transient model proposed in this paper, only one output, i.e., the total accumulated in-cavity field A(T), is measured after a time T. Below, we introduce the spectral scan rate as the figure of merit of various dark matter search protocols.

Defining the spectral scan rate

In this section, we begin with a general derivation of the scan-rate, not assuming specific detection approaches; Then, we connect to the in-cavity detection approach. Consider the axion photons located in a lineshape \({N}_{A}^{{\omega }_{Ac}}(\omega )\) centered at an unknown specific frequency ωAc ∈ [−B/2, B/2]. We use the notation ωAc to distinguish from the previous notation ωA = ωAc − ωc, which is relative to cavity resonance frequency ωc. Also note that for in-cavity protocol, this is a delta function as the random-phase-induced linewidth has been already included in the calculation of QFI. To scan the spectrum for the axion, the cavity resonance frequency ωc is shifted at a constant interval ϵ after each detection, as a sequence [− B/2: ϵ: B/2]. To cover the whole bandwidth B, B/ϵ rounds of detection is needed. For each detection, we denote the general QFI rate as \({\mathcal{J}}({\omega }_{Ac}-{\omega }_{c},T)/T\), to distinguish from the in-cavity approach notation of \({\mathcal{K}}\). In each round, we assume that one can obtain information for various different frequencies jΔω. Note that in the in-cavity protocol, a delta-function \({N}_{A}^{{\omega }_{Ac}}(\omega )\) dictates that information is only for a single frequency. For N = B/ϵ rounds, the average QFI rate in the N measurements is

where \({\mathbb{J}}\) is the spectral scan rate defined in ref. 25:

which has the unit of Hz/sec, where \({\mathcal{J}}(\omega )={\mathcal{J}}(\omega ,T\to \infty )\). In the first “ ≃ ” of Eq. (17), we have taken the Δω → 0 limit; in the second “ ≃ ”, we have taken the ϵ → 0 limit. The last “ ≃ ” is taking the B → ∞ limit. Here, we define the coherent time of axion to be \({\tau }_{A}=1/\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{-\infty }^{\infty }\frac{d\omega }{2\pi }| {\partial }_{{N}_{A}}{N}_{A}^{{\omega }_{Ac}}(\omega ){| }^{2}\) in a general sense, consistent with the steady-state limit of the phase jump model which yields a Lorenztian lineshape45. Here, we have assumed a fixed axion resonant frequency ωAc and obtained the scan rate formula. If one assumes a prior on ωAc and takes a Bayesian approach, the same scan-rate formula can also be obtained due to the frequency translational symmetry of the problem, as we detail in Supplementary Note 5.

The per-measurement QFI in Eq. (17) general. In the input-output model of ref. 25, we have taken the steady-state limit T → ∞, because the per-measurement QFI \({\mathcal{J}}\cdot T\Delta \omega\) is proportional to T; while the in-cavity QFI \({\mathcal{K}}(\omega ,T)\) saturates for large T and we choose T that maximizes the QFI rate \({\mathcal{K}}(\omega ,T)/T\). Note that, in general one needs frequency-resolved spectral detection to achieve Eq. (18), different from current input-output experiments20.

For the in-cavity protocol, the first line of Eq. (17) (before the continuous limit) can be further simplified by taking a single mode TΔω/2π = 1 and \({N}_{A}^{{\omega }_{Ac}}(\omega )={N}_{A}{\delta }_{\omega ,{\omega }_{Ac}}\) (where δx,y is the Kronecker delta with discrete values variables x, y), because we have included the lineshape due to phase jump in the calculation of \({\mathcal{K}}\). Thus, the average QFI rate for the in-cavity protocol is

where we have defined the spectral scan rate \({\mathbb{K}}\) as the average spectral QFI rate-bandwidth product

which has the unit Hz/sec. We integrate the QFI rate over the bandwidth, because in the spectral scanning, both the spectral scanning speed and the precision (QFI) of each detection are desired to be maximized. As a figure of merit, the scan rate is the precision-bandwidth product per second.

To achieve the same precision requirement in terms of the square of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR2)24, the minimum scanning time is

for the input-output protocol and in-cavity protocol, respectively. Now, it is clear that \({\mathbb{J}},{\mathbb{K}}\) characterizes the rate of achieving a precision-bandwidth product.

Bandpass-limited detection versus spectral receivers

Now we compare a transient in-cavity scan rate versus the input-output scan rate, assuming spectral resolution for the latter. For simplicity, we consider vacuum input, as the relative advantages of SMSS and TMSS over the vacuum limit is understood in previous sections. Using Eq.(42) in ref. 25, we obtain the optimal scan rate of the input-output protocol with photon counting on each spectral mode,

In Fig. 8, we find that in-cavity detection \({\mathbb{K}}\) and input-output detection \({\mathbb{J}}\) are comparable at the good cavity limit of Γ ≪ 1/τA. Indeed, \({\mathbb{K}}\) beats \({\mathbb{J}}\) by a constant factor of 3dB.

The scan rate ratio of (in-cavity) bandpass-limited photon counting \({\mathbb{K}}\) over (input-output) spectral photon counting \({\mathbb{J}}\) in logarithmic scale, versus the cavity loss rate Γ, using a vacuum state input. NT = 10−4. For the input-output method, intrinsic loss rate γ0 = Γ is chosen to be equal to the in-cavity method, coupling out rate γc is optimized to be 2γ0.

On the other hand, at the bad cavity limit Γ ≫ 1/τA, spectral photon counting in the input-output protocol (\({\mathbb{J}}\)) beats in-cavity detection (\({\mathbb{K}}\)) by a factor of Γ/(1/τA). This is because for the input-output protocol, one obtains the output signal over a long integration time window T ≫ 1/Γ, 1/τA, and can presumably count photons in the Fourier domain, which effectively collects all temporal signal bins over a time duration of τA coherently. By contrast, the waiting time T in the in-cavity protocol is limited to 1/Γ ≪ τA, which effectively operates the parallel bin measurement strategy into N ≃ τA/(1/Γ) bins. As predicted by our comparison between the coherent accumulation strategy and the parallel bin measurement strategy (see Supplementary Note 2), coherent collection via spectral photon counting achieves an advantage by a factor \({\tau }_{A}\Gamma ={{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\) when \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\gtrsim {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\). Hence, one desires a spectral photon counter or high-quality signal cavity (\({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}}\lesssim {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}\)) in order to maximize discovery reach for axion DM searches.

While an enhancement via quantum probes are achievable for high-quality signal cavities (i.e., \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{cav}}}/{{\mathcal{Q}}}_{{\rm{axion}}} > 1\)), there exists a threshold squeezing (or, more generally, a threshold occupation, Ns, of the input quantum probe), above which no further enhancement can be gained. This is not an intrinsic limitation but, rather, an artifact of the detection methods currently used (and also considered in this paper). In particular, our detection scheme consists of counting the photons of the cavity mode \(\hat{A}(T)\) within a time T, thus effectively counting photons within a single bandpass ~1/T (cf. refs. 15,19,20). Consequentially, the sensitivity of such bandpass-limited measurements depends on the ratio of the axion bandwidth and the signal cavity bandwidth, respectively15. This stimulated bandpass effect, in turn, constrains the advantage to be gained from stimulated DM scanning protocols using bandpass-limited photon counters.

To bypass the bandpass limitation, a spectral photon counter, capable of counting photons in individual frequency bins, is warranted46. Such a device necessitates, e.g., coupling the signal to an array of narrowband single photon counters (each centered at different frequencies) or requires an advanced light-matter interface functioning as a multiplexed quantum memory (see, e.g., Section VI.A of ref. 27 for further discussion of the latter). A spectral microwave photon counter would be a powerful quantum technology but currently seems out of reach. We have therefore opted to investigate what can be achieved with minimal quantum resources (e.g., bandpass-limited photon counting, as well as Gaussian-state probes), demonstrating regimes of quantum enhancement even under such limitations. In contrast, note that linear detection schemes (e.g., HAYSTAC22,23) measure output fields continuously and, thus, can operate as spectral receivers15 (i.e., measure power spectral densities). However, as is well known, such linear detectors are limited by vacuum fluctuations and require large squeezing values to compete with optimal photon counting methods (cf. ref. 47).

Discussion

For entanglement-assisted protocols, a good idler storage cavity may be achieved by superconducting ones since that cavity does not need to be in the presence of the magnetic field. In addition, in the distributed sensor network24, where multiple sensors are deployed to search for axion, entanglement ancilla becomes even more practical as a single ancilla storage cavity is sufficient to enhance the entire sensor network’s performance.

Typical stimulated axion DM search experiments, primarily HAYSTAC’s squeezed state receiver22,23, engineer probe states in a different manner than that proposed here. In particular, HAYSTAC’s squeezed-state receiver22,23 engineers the quantum state of extra-cavity fields—i.e., input and output fields that impinge on and exit from the cavity, respectively—rather than in situ engineering of the intra-cavity field considered here (see also refs. 41,42) In principle, there is no difference between extra-cavity state engineering protocols versus in situ state engineering protocols. However, in practice, the former may introduce finite “injection” losses (e.g., transmission line losses, extra coupling losses, etc.) when reflecting itinerant probe states off the cavity. These injection losses will severely limit the performance of Gaussian probe states, in accordance with the Rayleigh curse27. Thus, in situ state engineering (analogous to the recent CEASEFIRE protocol41,42) is crucial for Gaussian-state probes when photon counting is implemented at the measurement stage.

Finally, we note that there exists other strategies for the quantum advantage that can bypass Rayleigh’s curse. For instance, a Fock state receiver was recently implemented for a dark photon DM search28 (for theoretical analyses, see refs. 26,27), which is more robust to loss 1 − η with optimized photon number at the asymptotic limit of weak signal and ideal cooling NT → 0 given fixed loss, due to the non-Gaussian nature of a Fock state27. However, in this paper, we point out that loss can also be optimized to 1 − η(T) → 0 to maintain the quantum advantage. Besides, with current technology, it requires Josephson-junction-based superconducting elements (e.g., a superconducting control qubit) within the signal cavity to generate the Fock state, thus presenting a hurdle for axion DM searches where the signal cavity is immersed in a strong magnetic field. One could instead prepare propagating microwave photons in a Fock state and count the photons reflected off the signal cavity. In principle, this flying Fock state technique is feasible with an external Josephson-junction-based superconducting device. Though, to the best of our knowledge, such has not been developed that demonstrates both high fidelity and low propagation (or injection) losses for the purpose of quantum sensing. Finally, when these technology barriers are resolved, one can also consider applying loss optimization in this work to the case of other quantum probe states (e.g., Fock states), to obtain the best quantum advantage.

Methods

Formulation of cavity dynamics and detection

Our overall protocol involves preparing the cavity mode A(0) in a certain quantum state, evolve for time T, and then perform measurement on the cavity field A(T) to infer information about axion. To begin our analyses, we solve the dynamics for the intra-cavity field, A(T). As T is finite, previous models based on long-time analyses24,25 does not apply.

We consider a resonator in a bath with thermal population \({N}_{B}={({e}^{\hslash {\omega }_{c}/{k}_{B}{T}_{B}}-1)}^{-1}\), where ωc is the resonator frequency and TB is the bath effective temperature. The resonator has a non-linear element able to operate in a large magnetic field. In addition, we assume that it is possible to generate high squeezing in a short time. This is the case, for instance, of KIPA32,33,34.

The cavity mode A(t) interacts with an axion field, governed by the Langevin equation

where aB,in(t) and aA,in(t) are respectively the bath field and the axion field, γB, γA, and Γ = γA + γB are the coupling rates, and the equation is written in the rotating frame of frequency ωc. For a summary of notations and parameters, please refer to Table 1. We assume aB,in(t) to be a white thermal noise, satisfying the commutation relation \([{a}_{B,in}(t),{a}_{B,in}^{\dagger }({t}^{{\prime} })]=\delta (t-{t}^{{\prime} })\) and having the autocorrelation \(\langle {a}_{B,in}^{\dagger }({t}^{{\prime} }){a}_{B,in}(t)\rangle ={N}_{{\rm{T}}}\delta (t-{t}^{{\prime}})\). The observable effect of the axion field is to displace the cavity mode with a random phase in time. This is modeled by choosing aA,in(t) in a coherent state with amplitude \(\alpha (t)=| \alpha | {e}^{i{\omega }_{A}t+i{\theta }_{A}(t)}\), where ωA is the detuning between the axion and the resonator frequencies. ∣α∣2 gives the photon flux of the axion field, which is determined by the axion mass and local DM density13. In this paper, we consider the estimation of the occupation number per axion mode, NA ≡ ∣α∣2τA, where τA is the axion coherence time. When the impinging direction of dark matter is unknown, the effective ∣α∣2 in phase with the detector spatial mode can be a random variable, we define \({N}_{A}\equiv \left\langle | \alpha {| }^{2}\right\rangle {\tau }_{A}\) as the mean occupation number in general. The phase θA(t) is a classical random variable. We heuristically model θ subject to a random phase jump as follows: If a jump has occurred at time t, the next jump will occur at time \(t+{t}^{{\prime} }\) with probability \(p({t}^{{\prime} })={e}^{-{t}^{{\prime} }/{\tau }_{A}}/{\tau }_{A}\), where τA is the coherence time of the axion. At each jump, the phase is sampled uniformly at random in [0, 2π). Since the initial phase is also unknown and sampled uniform at random, the amplitude α is randomly distributed over the circle of radius α in the phase space. The state of aA,in is thereby fully dephased and diagonal in the photon-number basis, which is defined by the central moments. We derive the two-time correlation of α(t) as

The solution to Eq. (23) is the linear relation (also shown in Eq. (2))

where η(t) = e−Γt. Here, we have assumed a very weak coupling of the resonator with the axion field, i.e., γA ≪ γB. Also, we have introduced the temporal-matched modes \({a}_{(A,B)}(T)=\sqrt{\frac{\Gamma }{1-\eta (T)}}\,\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{T}\sqrt{\eta (T-\tau )}{a}_{(A,B),in}(\tau )d\tau\). The mode aB is in a thermal state with an average photon number NT. The state of mode aA is fully dephased and defined by the central moments, due to the aforementioned random phase jump. The second moment of aA can be obtained via

Computing Eq. (26) using Eq. (24) we obtain

where g is a lengthy dimensionless expression (see Supplementary Note 1). Finally, the effective axion occupation number mixed in the cavity mode \(\hat{A}\) at time T is

At the good cavity limit of Γ → 0, we have

We see that the photon flux \({n}_{A}^{{\rm{eff}}}/T\) is maximized at T → ∞. Indeed, for T → 0, \({n}_{A}^{{\rm{eff}}}\propto {T}^{2}\), while for T → ∞, \({n}_{A}^{{\rm{eff}}}\propto T\).

In principle, all central moments are needed to define the state of aA. However, we note that the axion coupling is extremely weak such that \(\sqrt{{\gamma }_{A}}| \alpha | \ll 1\), thus the moments of \(\sqrt{{\gamma }_{A}}\alpha\) beyond second order are negligible. Thus we adopt the Gaussian approximation that ignores the higher order terms, which significantly simplifies the calculation workload as the resulting states are Gaussian and formulas of Gaussian-state QFIs are well known36. Specifically, we assume that the per-mode axion occupation number ∣α∣2τA is a random variable subject to an exponential distribution with mean NA. Indeed, we assume that \(\Pr (| \alpha {| }^{2}{\tau }_{A}=x)={e}^{-x/{N}_{A}}/{N}_{A}\), which means that aA is in a Gaussian thermal state with mean photon number NAg(T, Γ, ωA, τA). To justify such approximation, in Supplementary Note 4 we show that the quantum advantage curves of the exact non-Gaussian model with ∣α∣ fixed are approximately the same as in the case of Gaussian in ref. 25. With such approximation, Eq. (25) represents a bosonic thermal loss channel48 from the initial field, A(0), to the final field, A(T).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The theoretical results of the manuscript are reproducible from the analytical formulas and derivations presented therein. Additional code is available from the first author upon reasonable request.

References

Blais, A., Grimsmo, A. L., Girvin, S. M. & Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025005 (2021).

Casariego, M. et al. Propagating quantum microwaves: towards applications in communication and sensing. Quantum Sci. Technol. 8, 023001 (2023).

Gottesman, D., Kitaev, A. & Preskill, J. Encoding a qubit in an oscillator. Phys. Rev. A 64, 012310 (2001).

Brady, A. J., Eickbusch, A., Singh, S., Wu, J. & Zhuang, Q. Advances in bosonic quantum error correction with Gottesman–Kitaev–Preskill codes: theory, engineering and applications. Prog. Quantum Electron. 93, 100496 (2024).

Kono, S., Koshino, K., Tabuchi, Y., Noguchi, A. & Nakamura, Y. Quantum non-demolition detection of an itinerant microwave photon. Nat. Phys. 14, 546 (2018).

Besse, J.-C. et al. Single-shot quantum nondemolition detection of individual itinerant microwave photons. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021003 (2018).

Lescanne, R. et al. Irreversible qubit-photon coupling for the detection of itinerant microwave photons. Phys. Rev. X 10, 021038 (2020).

Ahmed, Z. et al. Quantum sensing for high energy physics. Preprint at arXiv:1803.11306 [hep-ex] (2018).

Bass, S. D. & Doser, M. Quantum sensing for particle physics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 329–339 (2024).

Ye, J. & Zoller, P. Essay: Quantum sensing with atomic, molecular, and optical platforms for fundamental physics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 190001 (2024).

Graham, P. W., Irastorza, I. G., Lamoreaux, S. K., Lindner, A. & van Bibber, K. A. Experimental searches for the axion and axion-like particles. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 65, 485 (2015).

Bertone, G. & Tait, T. M. A new era in the search for dark matter. Nature 562, 51 (2018).

Sikivie, P. Invisible axion search methods. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 015004 (2021).

Berlin, A. et al. Searches for new particles, dark matter, and gravitational waves with SRF cavities. Preprint at arXiv:2203.12714 [hep-ph] (2022).

Lamoreaux, S. K., van Bibber, K. A., Lehnert, K. W. & Carosi, G. Analysis of single-photon and linear amplifier detectors for microwave cavity dark matter axion searches. Phys. Rev. D 88, 035020 (2013).

Zheng, H., Silveri, M., Brierley, R., Girvin, S. & Lehnert, K. Accelerating dark-matter axion searches with quantum measurement technology. Preprint at arXiv:1607.02529 (2016a).

Caves, C. M. Quantum limits on noise in linear amplifiers. Phys. Rev. D 26, 1817 (1982).

Beckey, J., Carney, D. & Marocco, G. Quantum measurements in fundamental physics: a user’s manual. Preprint at arXiv:2311.07270 [hep-ph] (2023).

Dixit, A. V. et al. Searching for dark matter with a superconducting qubit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 141302 (2021).

Braggio, C. et al. Quantum-enhanced sensing of axion dark matter with a transmon-based single microwave photon counter. Preprint at arXiv:2403.02321 [quant-ph] (2024).

Malnou, M. et al. Squeezed vacuum used to accelerate the search for a weak classical signal. Phys. Rev. X 9, 021023 (2019).

Backes, K. et al. A quantum enhanced search for dark matter axions. Nature 590, 238 (2021).

Jewell, M. J. et al. New results from HAYSTAC’s phase II operation with a squeezed state receiver. Phys. Rev. D 107, 072007 (2023).

Brady, A. J. et al. Entangled sensor-networks for dark-matter searches. PRX Quantum 3, 030333 (2022).

Shi, H. & Zhuang, Q. Ultimate precision limit of noise sensing and dark matter search. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 27 (2023).

Górecki, W., Riccardi, A. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology of noisy spreading channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 240503 (2022).

Gardner, J. W. et al. Stochastic waveform estimation at the fundamental quantum limit, Preprint at arXiv:2404.13867 [quant-ph] (2024).

Agrawal, A. et al. Stimulated emission of signal photons from dark matter waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 140801 (2024).

Mahashabde, S. et al. Fast tunable high-q-factor superconducting microwave resonators. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 044040 (2020).

Vahlbruch, H., Mehmet, M., Danzmann, K. & Schnabel, R. Detection of 15 db squeezed states of light and their application for the absolute calibration of photoelectric quantum efficiency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 110801 (2016).

Eberle, T., Händchen, V. & Schnabel, R. Stable control of 10 db two-mode squeezed vacuum states of light. Opt. Express 21, 11546 (2013).

Xu, M., Cheng, R., Wu, Y., Liu, G. & Tang, H. X. Magnetic field-resilient quantum-limited parametric amplifier. PRX Quantum 4, 010322 (2023).

Frasca, S., Roy, C., Beaulieu, G. & Scarlino, P. Three-wave-mixing quantum-limited kinetic inductance parametric amplifier operating at 6 t near 1 k. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 024011 (2024).

Vaartjes, A. et al. Strong microwave squeezing above 1 tesla and 1 kelvin. Nat. Commun. 15, 4229 (2024).

Tsang, M. Quantum noise spectroscopy as an incoherent imaging problem. Phys. Rev. A 107, 012611 (2023).

Gao, Y. & Lee, H. Bounds on quantum multiple-parameter estimation with Gaussian state. Eur. Phys. J. D 68, 1 (2014).

Manley, J., Wilson, D. J., Stump, R., Grin, D. & Singh, S. Searching for scalar dark matter with compact mechanical resonators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 151301 (2020).

Albert, R. et al. Microwave photon-number amplification. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011011 (2024).

Chaudhuri, S., Irwin, K. D., Graham, P. W. & Mardon, J. Optimal electromagnetic searches for axion and hidden-photon dark matter. Preprint at arXiv:1904.05806 [hep-ex] (2019).

Alesini, D. et al. Galactic axions search with a superconducting resonant cavity. Phys. Rev. D 99, 101101 (2019).

Wurtz, K. et al. Cavity entanglement and state swapping to accelerate the search for axion dark matter. PRX Quantum 2, 040350 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Accelerated weak signal search using mode entanglement and state swapping. PRX Quantum 4, 020302 (2023).

Pirandola, S. Quantum reading of a classical digital memory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 090504 (2011).

Shi, H., Zhang, Z., Pirandola, S. & Zhuang, Q. Entanglement-assisted absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 180502 (2020).

Manley, J., Chowdhury, M. D., Grin, D., Singh, S. & Wilson, D. J. Searching for vector dark matter with an optomechanical accelerometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 061301 (2021).

Ng, S. et al. Spectrum analysis with quantum dynamical systems. Phys. Rev. A 93, 042121 (2016).

Zheng, H., Silveri, M., Brierley, R. T., Girvin, S. M. & Lehnert, K. W. Accelerating dark-matter axion searches with quantum measurement technology. Preprint at arXiv:1607.02529 [hep-ph] (2016b).

Weedbrook, C. et al. Gaussian quantum information. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 621 (2012).

Gefen, T., Rotem, A. & Retzker, A. Overcoming resolution limits with quantum sensing. Nat. Commun. 10, 4992 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center (SQMS) under contract No. DE-AC02-07CH11359. H.S., A.J.B., and Q.Z. also acknowledge the support from National Science Foundation CAREER Award CCF-2240641, National Science Foundation OMA-2326746, National Science Foundation Grant No. 2330310, Office of Naval Research Grant No. N00014-23-1-2296, and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) under MeasQUIT HR0011-24-9-0362. R.D. acknowledges support from the Academy of Finland, grants no. 353832 and 349199. Q.Z. acknowledges discussions with Roni Harnik.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Z. proposed the study in discussion with R.D.C. and L.M. and supervised the project. H.S. performed the analyses and generated the figures, with inputs from all authors. A.J.B. contributed to the quantum advantage analyses under different cavity conditions. W.G. contributed to the Gaussian approximation of QFI analyses in Supplementary Note 3. L.M. contributed to the analyses of sequential and parallel measurement in Supplementary Note 2. R.D.C. contributed to the cavity modeling and obtained Eq. (27). H.S., A.J.B., and Q.Z. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, H., Brady, A.J., Górecki, W. et al. Quantum-enhanced dark matter detection with in-cavity control: mitigating the Rayleigh curse. npj Quantum Inf 11, 48 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01004-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01004-1