Abstract

The implementation of information processing on a quantum device is a fundamental challenge for many technologies. As a matter of fact, the faster one wants to implement a quantum operation, the higher is the thermodynamic cost of realizing the quantum process. Here, we theoretically propose and experimentally verify a trade-off between quantum speed and energy cost using Schatten 2-norm. Our findings demonstrate that this trade-off remains tight for any instant of time, whether dealing with initial eigenstates or initial thermal equilibrium states, as illustrated by the Landau-Zehner model. This observation underscores the significance of coherence of the evolved states. By extending our method to open system, we find that quantum speed can be significantly affected by environmental decoherence effect. These results illuminate the fundamental limits of quantum state dynamics and hold promise for potential applications in quantum sensing and quantum computing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leveraging the unique properties of quantum superposition and entanglement, quantum information processing (QIP) offers significant advantages for performing tasks that are beyond the reach of usual information processing, as can be seen in areas such quantum computation1,2, secure communication3, quantum metrology4, quantum thermodynamics5,6,7,8, and quantum energy storage9,10,11,12. However, even before the arrival of universal and general-purpose quantum computers13, questions about the rate at which a quantum device could process information or the energy costs associated with maintaining a certain operational speed were prevalent14,15,16,17. In this sense, the Mandelstam-Tamm (MT) bound18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, described by τ = ℏπ/(2ΔE) where \(\Delta E=\sqrt{\langle {H}^{2}\rangle -{\langle H\rangle }^{2}}\), delineates the temporal limit on how fast closed systems can evolve between two orthogonal quantum states, establishing a trade-off between the time duration and the energy cost in such process. These constraints are referred to as quantum speed limits (QSL).

Matrix norms are important tools for analyzing the QSL26,27,28,29 and the associated energy cost rate15,30,31,32 of the dynamic process. Within this context, based on Schatten p-norms, some QSL applicable to arbitrary physical processes have been theoretically established33,34,35. Additionally, the concept of energy cost has been linked to the time-averaged Frobenius norm of the Hamiltonian, tailored to specific scenarios30. In addition, a fundamental relationship between quantum speed and energy cost rate has been both theoretically and experimentally studied for transitionless quantum driving in closed quantum systems36,37. However, the trade-off relationship is generally not tight or practically attainable36,37, which cannot accurately reflect the true dynamical process of quantum system. Moreover, there are few experimental analysis in real laboratory scenarios38,39,40 which would be important to investigate and enhance the performance of, at least, quantum devices prototypes9.

Here, we establish and experimentally validate a trade-off between quantum speed and its associated energy cost rate based on Schatten 2-norm in Hilbert space. This approach offers a versatile method for handling both unitary and nonunitary dynamics. It distinctly separates the contribution of populations and coherences of the evolved state, thereby elucidating their individual roles in driving the evolution. We find for unitary dynamics it is the creation of quantum coherence in the basis of the generator of the control Hamiltonian. Noteworthy, for pure states evolving along a geodesic in Hilbert space, we find that the quantum speed saturates to the energy cost rate for N-level quantum systems. Particularly, we also have VQSL = P ∂tC for arbitrary single-qubit states, where P is the polarization of quantum state, VQSL is the quantum speed and ∂tC is the energy cost rate. Hence, our result demonstrate that this trade-off significantly outperforms previous models that lacks such tightness36,37,41. We substantiate our results experimentally using a solid spin in diamond, whose effective dynamics can be described by the time-dependent Landau-Zener (LZ) model42. Furthermore, when we expand our method to encompass open quantum systems, our experimental investigations reveal how the speed of quantum evolution can be affected by decoherence effect of environment36,37. These findings provide a comprehensive and powerful approach to implement solid-state QIP at QSL, with potential impact on the characterization and control of quantum technologies43,44,45,46,47.

Results

QSL and energy cost rate for unitary dynamics

We consider general unitary dynamics and seek to determine the minimal time τ required for evolution from an initial state ρ0 to a final state ρτ as shown in Fig. 1. Hereafter, we set ℏ = 1. The dynamics for state ρt is governed by the Liouville-von Neumann equation \({\dot{\rho }}_{t}=i\left[{\rho }_{t},H\right]\), where \({\dot{\rho }}_{t}=d{\rho }_{t}/dt\), and H is the time-dependent Hamiltonian of the system. In this setting, we directly define the quantum speed as

where \({\left\Vert \bullet \right\Vert }_{2}\) is the Schatten 2-norm34,35. We note that the quantum speed can be cast as \({V}_{QSL}=\sqrt{2{{\mathcal{I}}}_{L}({\rho }_{t},H)}\), where \({{\mathcal{I}}}_{L}({\rho }_{t},H)=-(1/4)\,\text{Tr}\,({[{\rho }_{t},H]}^{2})\) is a quantum coherence measure introduced in Ref. 48. To make Eq. (1) more explicit, we can write the density operator ρt in its spectral decomposition, \({\rho }_{t}={\sum }_{j}{\lambda }_{j}\left\vert j\right\rangle \left\langle j\right\vert\), with 0 ⩽ λj ⩽ 1 and ∑jλj = 1, and get \({V}_{QSL}=\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{i\ne j}{\left({\lambda }_{i}-{\lambda }_{j}\right)}^{2}{\left\vert \left\langle i\right\vert H\left\vert j\right\rangle \right\vert }^{2}}\).

The blue (L1) and red (L2) curves denote different evolution paths in Hilbert space representing a generic evolution between an initial state ρ0 and a final state ρτ, parameterized by time τ. In particular, the blue curve depicts the geodesic connecting ρ0 to ρτ. QSL originate from the fact that the geodesic amounts to the path of shortest length among all physical evolutions between the given initial and final states.

Obviously, there is an intimate relation between QSL and metrology, in which the best precision in estimating parameter encoded into a state depends on how quickly the state evolves49. Specifically, the quantum speed based on Schatten 2-norm serves as a nontrivial lower bound of the quantum Fisher information (QFI) \({\mathscr{F}}=\frac{1}{2}{\sum }_{i\ne j}\frac{{({\lambda }_{i}-{\lambda }_{j})}^{2}}{{\lambda }_{i}+{\lambda }_{j}}{\left\vert \left\langle i\right\vert H\left\vert j\right\rangle \right\vert }^{2}\geqslant {V}_{QSL}^{2}\) to detect metrologically useful asymmetry of quantum resources50,51. For pure states \({\rho }_{t}=\left\vert {\psi }_{t}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{t}\right\vert\) with \(t\in \left[0,\tau \right]\), we will have \({\rho }_{t}^{2}={\rho }_{t}\), \(\,\text{Tr}\,{\left({\rho }_{t}H\right)}^{2}={\text{Tr}}^{2}({\rho }_{t}H)\), and \({\mathscr{F}}={V}_{QSL}^{2}\). Particularly, for a given time-dependent pure state, one finds that VQSL, QFI, and the Wigner-Yanase skew information (WY) \({\mathcal{I}}({\rho }_{t},H)=-(1/2)\,\text{Tr}\,({[\sqrt{{\rho }_{t}},H]}^{2})\) are equal to each other except for a constant factor. However, the measurement of QFI is extremely challenging for general physical processes52, which is completely different from our quantity VQSL. Indeed, for open quantum systems, the quantities VQSL, QFI and WY are expected to exhibit different behaviors as the quantum state loses coherence. Let \(H={\sum }_{n}{E}_{n}\left\vert n\right\rangle \left\langle n\right\vert\) be the Hamiltonian that drives the dynamics of a finite-dimensional quantum system. The arbitrary instantaneous state ρt can be decomposed into two components with respect to the eigenbasis of H53: an incoherent part (δt), and a coherence matrix (coht = ρt − δt). The incoherent part is diagonal matrix in the eigenbasis of H. In this setting, we have \(\left[{\rho }_{t},H\right]=\left[co{h}_{t},H\right]\), with \(\left[{\delta }_{t},H\right]=0\). Therefore, Eq. (1) reduces to \({V}_{QSL}=\sqrt{\,\text{Tr}\,[co{h}_{t}^{2}{H}^{2}-{(co{h}_{t}H)}^{2}]}\). Importantly, this result clearly highlights the contribution of the coherences of the evolved state to our QSL, underscoring the significance of quantum coherence as a vital resource for maintaining coherent dynamics.

When disregarding the setup constant, the energy cost rate or power15,31 associated with control field H based on Schatten 2-norm can be written in general as36

Next, by rewriting Eq. (2) with respect to the eigenstates of the density matrix ρt, we have that \({\partial }_{t}C=\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}{{\sum }_{i,j}\left\vert \left\langle i\right\vert H\left\vert j\right\rangle \right\vert }^{2}}\). Hence, for N-level quantum systems, one finds that the quantum speed is upper bounded by the energy cost rate, i.e., VQSL ⩽ ∂tC. This result shows that the energy cost rates poses a maximum value to the quantum speed of the system, which holds for any mixed state. Particularly, for arbitrary two-level systems, we also have VQSL = P∂tC, where \(P=\left\vert {\lambda }_{1}-{\lambda }_{2}\right\vert\) is the polarization of the general single-qubit state. This result shows that, the faster one wants to implement a quantum operation, the higher the thermodynamic cost of realizing the quantum process becomes. Next, we discuss the saturation of the above bound for pure states of N-level systems. In Fig. 1 we depict the evolution of the state ρt along a geodesic path that connects initial ρ0 and final ρτ states of the dynamics. In this setting, one finds that the so-called transversality condition \(\left\langle i\right\vert H\left\vert i\right\rangle =0\) is satisfied for all i = {1, …, N}15,54,55, which implies that Eq. (2) reduces to \({\partial }_{t}C=\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}{{\sum }_{i\ne j}\left\vert \left\langle i\right\vert H\left\vert j\right\rangle \right\vert }^{2}}\). Therefore, for pure states, it turns out that the quantum speed and the energy cost rate collapse to the same value, VQSL = ∂tC, thus saturating the above-mentioned bound. And the tightness of our established bound can be leveraged to eliminate the redundant information of H, thereby demonstrating that time-optimal control is realized with low energy cost.

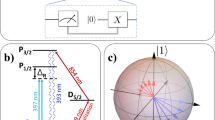

We experimentally validate our findings using a single nitrogen-vacancy (NV) center in diamond using the time-dependent LZ Hamiltonian, characterized by its instantaneous eigenvalues {εn(t)} and eigenstates {nt(t)}. The spin state is initialized to the ground state and read out via 532 nm laser pumping56. To suppress the photon shot noise of NV center, we repeated the experimental cycle for 1 × 107 times (See Experimental Setup in Method). Our basis states are encoded into \(\left\vert {m}_{s}=+1\right\rangle \equiv \left\vert 1\right\rangle\) and \(\left\vert {m}_{s}=0\right\rangle \equiv \left\vert 0\right\rangle\) of ground state. The coherence time of qubit is \({T}_{2}^{* } \sim 1.4\,\mu {\rm{s}}\). The LZ model is described by \({H}_{LZ}=\frac{\Gamma (t)}{2}{\sigma }_{z}+\frac{\Omega }{2}{\sigma }_{x}\), where σx, σy, σz are the Pauli matrices. In our study, the scan field Γ(t) takes a linear shape and Ω is a constant. By adding an ancillary counterdiabatic field (CD) of the form \({H}_{CD}=i\left[{\partial }_{t}\left(\left\vert {n}_{t}\right\rangle \left\langle {n}_{t}\right\vert \right),\left\vert {n}_{t}\right\rangle \left\langle {n}_{t}\right\vert \right],\) the quantum system is driven precisely through the adiabatic manifold of the drift Hamiltonian HLZ, hence realizing a transitionless quantum driving (TQD)6,30 on timescales shorter than decoherence times (\({T}_{2}^{* }\)). It is evident that, in the context of TQD, the instantaneous cost rate reduces to6\({\partial }_{t}C=\sqrt{\langle {\partial }_{t}{n}_{t}| {\partial }_{t}{n}_{t}\rangle }\). Thus, the total Hamiltonian is given by Ht = HLZ + HCD. By precisely modulating the frequency and phase of a microwave (MW) pulse, the LZ model can be accurately implemented in experiment (See Hamiltonian Engineering in Method).

In the experiment, we begin by considering a closed quantum system (\(\tau\;\ll\;{T}_{2}^{* }\)), where the initial state ρ0 undergoes a unitary evolution \({\rho }_{t}={U}_{t}{\rho }_{0}{U}_{t}^{\dagger }\), with \({U}_{t}={{\mathcal{T}}}_{\leftarrow }\exp (-i\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{t}{H}_{t}d{t}_{1})\), while \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{\leftarrow }\) is the time-ordering operator. The amplitude, frequency, and phase of the MW is directly generated by an arbitrary waveform generator. After applying the MW pulses, we measure the quantum system with quantum state tomography (QST) and the results are presented in Fig. 2a. We investigate the trade-off between quantum speed (VQSL) and energy cost rate (∂tC) and our quantum speed reaches the theoretical upper limit over the entire protocol duration τ, as illustrated in Fig. 2b and c. In ref. 37, the researchers define a quantum speed \({V}_{rp}=\vert \,\text{tr}\,({\rho }_{0}{\dot{\rho }}_{t})\vert\) based on relative purity, which deviates from the curve of energy cost rate as shown in Fig. 2b. It is worth noting that QSL was investigated using a similar figure of merit that takes into account the ratio of the Schatten speed \(\parallel {\dot{\rho }}_{t}{\parallel }_{2}\) to the purity \(\parallel {\rho }_{0}{\parallel }_{2}^{2}=\,\text{Tr}\,({\rho }_{0}^{2})\) of the probe state29. Hence, our trade-off relationship between quantum speed and energy rate is tighter than those reported in previous studies36,37, thus more accurately reflecting the actual dynamics. When the quantum system approaches the avoided crossing point (t = τ/2), both the energy cost rate and the quantum speed increase when utilizing CD fields. This phenomenon can be explained using the Fermi golden rule for time-dependent perturbations, which indicates that the transition probabilities are proportional to the time-integrated perturbation36,38. Far from the avoided crossing, the energy cost rate of the CD field remains largely constant with respect to evolution time, resulting in an instantaneous energy cost rate close to zero. Figure 2d demonstrates that the energy cost rate scales consistently with the quantum speed for various passage times, illustrating that faster quantum control necessitates higher energy consumption.

a The experimental steps for LZ model starting from the initialization to the final QST. The state trajectories represented by \({P}_{n}=\,\text{tr}\,\left({\rho }_{t}{\sigma }_{i}\right)\) and n = {x, y, z} under the Hamiltonian Ht. Discrete points in the figures denote experimental results, whereas solid lines represent theoretical predictions. b Time evolution of our quantum speed VQSL (red dots) and energy cost rate ∂tC (solid blue curve, theoretical prediction). The solid gold line denotes quantum speed based on relative purity. c Time evolution of our trade-off VQSL/∂tC within the LZ crossing time window. d The instantaneous quantum speed (red dots) and energy cost rate (solid blue line, theoretical prediction) for t = 0.48τ as a function of different passage times τ. The parameters used in the scan process are Γ = 16(t/τ − 0.5) MHz and Ω = 2 MHz for a-d.

We then consider a more complex scenario by examining the trade-off in the context of an initially prepared mixed state, specifically a thermal equilibrium state (TES). This initial TES is more intricate compared to a pure state. Initially, we apply a gate \({\left(\theta \right)}_{x}={e}^{-i\theta {\sigma }_{x}/2}\) to a qubit. Subsequently, we allow this quantum state to evolve freely in a noisy environment for a duration of \(t=3{T}_{2}^{* }\) to eliminate quantum coherence39,53, effectively removing all off-diagonal elements of the quantum state. Finally, the initial TES \(\rho =\left(\begin{array}{cc}{\cos }^{2}\left(\theta /2\right)&0\\ 0&{\sin }^{2}\left(\theta /2\right)\end{array}\right)\) is well prepared with a degree of polarization \(P=\left\vert \cos \theta \right\vert\). Similar to the procedure for an initially prepared pure state, we design same operational MW sequences and measure the quantum tomographic results of ρt, see Fig. 3a. The test of our proposed trade-off is conducted similarly to the case of an initially pure state, except for the factor of polarization P = 0.9. From the observations in Fig. 3b, c, we can draw the same conclusions as in the case of the initially pure state: ∂tC represents the optimal upper bound of the VQSL, thereby achieving the optimal trade-off. Furthermore, for general initial TES with different polarizations, a new concise trade-off between the QSL and the energy cost rate based on Schatten 2-norm can be expressed as VQSL = P∂tC as shown in Fig. 3d, which implies that only the coherence of the quantum state has a contribution to the quantum speed for unitary evolution.

a The TES trajectories with P = 0.9 under the Hamiltonian Ht. b Time evolution of the quantum speed VQSL (red dots) and energy cost rate (solid blue curves, theoretical prediction) of panel a. The gold line denotes the time evolution of quantum speed based on relative purity. c The instantaneous quantum speed (red dots) and energy cost rate (solid blue line, theoretical prediction) of TES with P = 0.9 for t = 0.48τ as a function of different passage times τ. d The normalized quantum speed as a function of the polarization of TES, while keeping the parameters of scan process fixed. The blue dots are experimental results and blue line is theoretical prediction. The parameters used in the scan process are Γ = 16(t/τ − 0.5) MHz and Ω = 2 MHz for (a–d).

QSL and energy cost rate for nonunitary dynamics

We now examine a paradigmatic example of nonunitary physical processes acting on a single qubit: the Gaussian dephasing scenario57,58,59. In such noisy environment, the state evolution is governed by a master equation given by \({\dot{\rho }}_{t}=-i[H,\rho ]+{\mathscr{L}}(\rho )\), where \({\mathscr{L}}\) describes the environment noise. As shown in Fig. 4a, we further consider the Hamiltonian H = Δσz/2, which is pertinent to the Ramsey interference protocol in quantum sensing45,60,61,62. Here, Δ denotes the frequency shift that is to be measured. The Gaussian dephasing noise lets an initial state \({\rho }_{0}=\left(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle \right)\left(\left\langle 0\right\vert +\left\langle 1\right\vert \right)/2\) evolve as \({\rho }_{t}=\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{j = 0}^{1}{K}_{j}{\rho }_{0}{K}_{j}^{\dagger }\), where \({K}_{0}=\sqrt{{q}_{+}}\left(\begin{array}{cc}{e}^{-i\Delta t/2}&0\\ 0&{e}^{i\Delta t/2}\end{array}\right)\), \({K}_{1}=\sqrt{{q}_{-}}\left(\begin{array}{cc}{e}^{-i\Delta t/2}&0\\ 0&-{e}^{i\Delta t/2}\end{array}\right)\) are the Kraus operators, and q± = (1 ± α)/2 with \(\alpha ={e}^{-{\left(t/{T}_{2}^{* }\right)}^{2}}\). The effect of Gaussian dephasing is exactly the same as the one of phase flip and consists in shrinking the Bloch sphere onto the z axis of states diagonal in the computational basis, which are instead left invariant. In addition, Δ describes the rotation frequency around the z axis. Substituting the aforementioned expressions into Eq. (1) yields:

where \({V}_{coh,QSL}=\Delta {e}^{-{\left(t/{T}_{2}^{* }\right)}^{2}}/2\), and \({V}_{dec,QSL}=t{e}^{-{(t/{T}_{2}^{* })}^{2}}/{({T}_{2}^{* })}^{2}\) (See Decoherence Model in Method). However, the energy cost rate based on Schatten 2-norm does not change in this situation. The first term Vcoh,QSL is the energy fluctuation which characterizes the velocity for a unitary time-evolution generated by the system Hamiltonian. And the trade-off between coherent quantum speed and the energy cost rate in the Gaussian dephasing model is still given by Vcoh,QSL = α∂tC. When the inevitable quantum dephasing effect occurs in dissipative open quantum systems, the coherent quantum speed Vcoh,QSL exhibits a monotonic decay alongside the loss of quantum coherence. However, an additional term, Vdec,QSL emerges specifically due to the quantum dephasing effect. Interestingly, Vdec,QSL does not change monotonically with the evolution time, which elucidates the characteristics of the noise spectral density within a limited bandwidth of the decoherence environment. In experiment, the NV center electron spin decoherence is not limited by the spin-lattice relaxation, and therefore the decoherence effect of phonon scattering can be neglected. The coupling to electron or dark nuclear spins in diamond can induce faster decoherence. Since the NV center has a zero-field splitting in the order of GHz, which is much larger than the typical hyperfine interaction strength (<MHz), the electron spin can hardly be flipped by the hyperfine interaction. Due to lager energy mismatching between NV center and dark nuclear spin bath environment, the dynamics can be regarded as a pure dephasing process. In the pure dephasing regime, the system-bath coupling operator commutes with the system Hamiltonian, so the coherent evolution and dephasing contributions act independently. Hence, Vtot,QSL can always be divided into coherent and incoherent quantum speeds.

a The modified Ramsey interference protocol for investigating QSL in nonunitary dynamics with a non-zero detuning Δ. In this protocol, the first \({\left(\pi /2\right)}_{y}\) gate rotates the qubit from a initiate state \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle\) into a coherent superposition state \(\left(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle \right)/\sqrt{2}\), which then evolves for a given time τ. After evolution, the last π/2 gate of the standard Ramsey interference protocol is replaced by QST. The dynamic process is shown with a Bloch-sphere. b Quantum state evolutions during the Ramsey interference with Δ = 0.3 MHz. Experiment results are fitted with different solid lines. c The instantaneous total quantum speed (red dots) and energy cost rate (solid blue line, theoretical prediction) for modify Ramsey interference protocol with Δ = 0.3 MHz. d, e Similar results of Fig. 4b and Fig. 4c with different detuning Δ = 2 MHz. Experiment results are denoted with red dots, while the remaining dashed lines represent theoretical predictions.

Figure 4b illustrates the measurement results of state evolution during the Ramsey interference protocol. The qubit loses coherence on the \({T}_{2}^{* }\) timescale for quantum sensing process. We then calculate the total quantum speed Vtot,QSL based on Eq. (1) with a numerical derivative method, and the results are depicted in Fig. 4c. The actual measured total quantum speed lies between Vcoh,QSL and Vtot,QSL in experiment. We observe a discrepancy between experimental data and theoretical predictions of the Gaussian dephasing model for Ramsey interferometry measurement. In fact, the quantum fluctuation caused by the nearby 13C spins is comparable to the thermal fluctuation for a solid single spin system in diamond, and thus remains hidden within the ensemble average of the conventional nuclear magnetic resonance experiment40,63,64. Consequently, this observed discrepancy reveals the anisotropic nature of the hyperfine coupling of spin defect in solid. By increasing the frequency shift Δ, the Vcoh,QSL will increase proportionally and eventually tend to the total speed Vtot,QSL as shown in Fig. 4d, e. However, the Vdec,QSL, which is dominated by intrinsic dark nuclear spin bath environment of NV center, does not change with Δ in this situation.

Discussion

In summary, we have established an optimal trade-off between the quantum speed and the energy cost rate of quantum control based on Schatten norm. Using spin defect in diamond, we have theoretically and experimentally validated that this new trade-off stands out from previous relations by being tight in closed quantum systems. Indeed, only quantum coherence contributes to the quantum speed in unitary dynamics. Our bound??s tightness allows for the removal of control field’s redundant information, indicating that time-optimal control is realizable at low energy cost. Additionally, we have identified a new form of incoherent quantum speed in open quantum systems, driven by quantum decoherence effects. The time-dependent behavior of this incoherent quantum speed differs significantly from that of coherent quantum speed. The relative deviation quantifies the extent to which the dynamical evolution deviates from the Gaussian dephasing associated with the considered metric. Furthermore, in the future, the solid-state spin defects could be used to explore the impact of non-Markovian effects65,66,67, such as structured environmental spectral densities, nonlocal correlations between environmental degrees of freedom, and correlations in the initial system-environment state, on this trade-off relationship beyond elaborate engineering quantum systems. And based on our previous experimental results65, the non-Markovian environment has a non-trivial effect on the trace distance between two different quantum states. Coincidentally, the QSL can be defined by the change rate of the trace distance34. Hence, one can realized certain quantum states transformation by the non-Markovian effect with less energy cost of quantum control, which would beyound the current theoretical framework.

Methods

Experimental setup

A 532-nm laser (MLL-III-532-nm, New Industries Optoelectronics) is used to optically excite NV centers and read their states. The optical setup employed for all the measurements is a homebuilt scanning confocal microscope. The single crystal (100) diamond sample used in this work is chemical vapor deposition grown, electronic-grade type IIa-crystal (Element 6). The NV centers are generated by 40 keV 14N+ ion implantation followed by annealing in high vacuum at 1000 0C. The boiling tri-acid solution (a balanced mix of nitric, sulfuric, and perchloric acids) is used to clean the diamond sample and is eventually diluted by deionized water. The estimated average depth of the NV is about 40 nm. The laser beam is focused on a spot with a diameter of 400 nm using a Olympus objective with an NA = 0.95. Fluorescence photons are collected into a fiber and detected by the singlephoton counting module (SPCM-AQRH-15-FC, Excelitas), with a counting rate of 70 kHz and a signal-to-noise ratio of 50:1. It is separated from the excitation light by a Semrock dichroic mirror, a long-pass filter with a 650 nm cutoff, and spatially filtered through a 15 μm pinhole. The MW pulses for controlling the NV center are generated by an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) (Keysight M8190a), and fed into the coplanar waveguide microstructure on the quartz glass. The driving MW is amplified by an amplifier (Mini-circuits ZHL-25W-63+). A SpinCore programmable pulse generator (Pulse Blaster ESR-PRO 500) controls the MW switch and acoustic-optic modulator. The position of the NV center is adjusted using a piezo stage (P-611.3, Physik Instrument). The position of the permanent magnet is controlled by a 3D motorized translation stage.

Hamiltonian engineering

By tuning the MW frequency resonant with the \(\left\vert 0\right\rangle \leftrightarrow \left\vert 1\right\rangle\) transition, a pseudo-spin-1/2 system is realized in experiment. The Hamiltonian of a continuous phase-modulated MW driving field on the NV center is given by:

where f1 = D − γeB0, a(t) = γeB(t). After transforming the Hamiltonian to an appropriate rotating frame defined by the following unitary:

and adopting the rotating-wave approximation (RWA), the Hamiltonian for the qubit is simplified to the standard form: \({H}_{H}={U}_{1}^{\dagger }{H}_{S}{U}_{1}+i(\partial {U}_{1}^{\dagger }/\partial t){U}_{1}.\)

If we set f1 − g(t) = Γ(t), \(\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{t}g({t}^{{\prime} })d{t}^{{\prime} }-{\varphi }_{1}(t)=0\), a(t) = Ω(t), we will get

which is equivalent to the Landau-Zener (LZ) Hamiltonian \({H}_{LZ}=\frac{\Gamma (t)}{2}{\sigma }_{z}+\frac{\Omega (t)}{2}{\sigma }_{x}\).

Decoherence model

The abundance of 13C in diamond plate is at the nature level of 1%. This diamond material contains less than 5 ppb nitrogen concentration (P1 centers). The dephasing effect of 13C nuclear spin is approximately equivalent to the decoherence of P1 centers with a concentration of 10 ppm. Therefore, the dephasing effect of P1 centers in our experiment can be neglected. At room temperature, the 13C nuclear spins in diamond are totally unpolarized. Thus the bath can be described by a density matrix

with M being the number of 13C included in the bath, I is a unity matrix of dimension 2M, \(\left\vert J\right\rangle ={\otimes }_{m}\left\vert {j}_{m}\right\rangle\) is an eigenstate of the nuclear spin bath, and ProbJ is the probability distribution. We neglect the slow dynamics related to dipolar interactions between nuclear spins within the bath, which is at most 2 kHz for nearest-neighbor interaction. Indeed, the interaction between the nitrogen-vacancy center spin and the bath induces decoherence at a much faster rate than the dipolar coupling between 13C’s within the bath. Without the flip-flop dynamics for nuclear spin bath, the nuclear spin ensemble would be a random distribution of frozen configurations, which, as a standard multinomial distribution for a large system, leads to a Gaussian distribution of the nuclear Overhauser field

where E0 denotes the averaged local field and \({\Gamma }_{2}^{* }\) is the width of inhomogeneous broadening. This so-called inhomogeneous broadening would cause a Gaussian decay of the solid spin coherence, \({e}^{-{(t/{T}_{2}^{* })}^{2}}\) with the dephasing time \({T}_{2}^{* }\). Usually at high-temperatures, the thermal fluctuations of nuclear spin bath are much stronger than the quantum fluctuations. However, in the case of strong system-bath coupling, the quantum fluctuation can be comparable to the thermal fluctuation. The quantum fluctuations can induce notable effects on Ramsey interference measurement results even at room temperature (which can be regarded as infinite for the nuclear spin baths). Hence, the dephasing would be in general non-Gaussian under the competition between the thermal and quantum fluctuations.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Harrow, A. W. & Montanaro, A. Quantum computational supremacy. Nature 549, 203–209 (2017).

Markov, I. L. Limits on fundamental limits to computation. Nature 512, 147–154 (2014).

Xu, F., Ma, X., Zhang, Q., Lo, H.-K. & Pan, J.-W. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92, 025002 (2020).

Braun, D., Adesso, G., Benatti, F., Floreanini, R., Marzolino, U., Mitchell, M. W. & Pirandola, S. Quantum-enhanced measurements without entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035006 (2018).

Deffner, S. & Campbell, S. Quantum Thermodynamics: An introduction to the thermodynamics of quantum information (Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2019).

Yan, L.-L., Bu, J.-T., Zeng, Q., Zhang, K., Cui, K.-F., Zhou, F., Su, S.-L., Chen, L., Wang, J., Chen, G. & Feng, M. Experimental verification of demon-involved fluctuation theorems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 090402 (2024).

Yan, L. L., Xiong, T. P., Rehan, K., Zhou, F., Liang, D. F., Chen, L., Zhang, J. Q., Yang, W. L., Ma, Z. H. & Feng, M. Single-atom demonstration of the quantum Landauer principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 210601 (2018).

Pires, D. P. & de Oliveira, T. R. Relative purity, speed of fluctuations, and bounds on equilibration times. Phys. Rev. A 104, 052223 (2021).

Campaioli, F., Gherardini, S., Quach, J. Q., Polini, M. & Andolina, G. M. Colloquium: Quantum batteries. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 031001 (2024).

García-Pintos, L. P., Hamma, A. & del Campo, A. Fluctuations in extractable work bound the charging power of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 040601 (2020).

Gyhm, J.-Y., Šafránek, D. & Rosa, D. Quantum charging advantage cannot be extensive without global operations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 140501 (2022).

Campaioli, F., Pollock, F. A., Binder, F. C., Céleri, L., Goold, J., Vinjanampathy, S. & Modi, K. Enhancing the charging power of quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 150601 (2017).

De Leon, N. P., Itoh, K. M., Kim, D., Mehta, K. K., Northup, T. E., Paik, H., Palmer, B., Samarth, N., Sangtawesin, S. & Steuerman, D. W. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science 372, eabb2823 (2021).

Nicholson, S. B., García-Pintos, L. P., del Campo, A. & Green, J. R. Time–information uncertainty relations in thermodynamics. Nat. Phys. 16, 1211–1215 (2020).

Garcia, L., Bofill, J. M., Moreira, Id. P. R. & Albareda, G. Highly adiabatic time-optimal quantum driving at low energy cost. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 180402 (2022).

Sørensen, J. J. W., Pedersen, M. K., Munch, M., Haikka, P., Jensen, J. H., Planke, T., Andreasen, M. G., Gajdacz, M., Mølmer, K. & Lieberoth, A. et al. Exploring the quantum speed limit with computer games. Nature 532, 210–213 (2016).

Bofill, J. M., Sanz, A. S., Albareda, G., Moreira, Id. P. R. & Quapp, W. Quantum Zermelo problem for general energy resource bounds. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033492 (2020).

Mandelstam, L. The uncertainty relation between energy and time in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics. J. Phys. (USSR) 9, 249 (1945).

Deffner, S. & Campbell, S. Quantum speed limits: from Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to optimal quantum control. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 50, 453001 (2017).

Pires, D. P., Cianciaruso, M., Céleri, L. C., Adesso, G. & Soares-Pinto, D. O. Generalized geometric quantum speed limits. Phys. Rev. X 6, 021031 (2016).

Ness, G., Lam, M. R., Alt, W., Meschede, D., Sagi, Y. & Alberti, A. Observing crossover between quantum speed limits. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj9119 (2021).

Fogarty, T., Deffner, S., Busch, T. & Campbell, S. Orthogonality catastrophe as a consequence of the quantum speed limit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 110601 (2020).

Ness, G., Alberti, A. & Sagi, Y. Quantum speed limit for states with a bounded energy spectrum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 140403 (2022).

Xu, T.-N., Li, J., Busch, T., Chen, X. & Fogarty, T. Effects of coherence on quantum speed limits and shortcuts to adiabaticity in many-particle systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023125 (2020).

Lam, M. R., Peter, N., Groh, T., Alt, W., Robens, C., Meschede, D., Negretti, A., Montangero, S., Calarco, T. & Alberti, A. Demonstration of quantum brachistochrones between distant states of an atom. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011035 (2021).

Deffner, S. Geometric quantum speed limits: a case for Wigner phase space. New J. Phys 19, 103018 (2017).

Campaioli, F., Pollock, F. A., Binder, F. C. & Modi, K. Tightening quantum speed limits for almost all states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 060409 (2018).

Deffner, S. & Lutz, E. Quantum speed limit for non-Markovian dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 010402 (2013).

del Campo, A., Egusquiza, I. L., Plenio, M. B. & Huelga, S. F. Quantum speed limits in open system dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 050403 (2013).

Guéry-Odelin, D., Ruschhaupt, A., Kiely, A., Torrontegui, E., Martínez-Garaot, S. & Muga, J. G. Shortcuts to adiabaticity: Concepts, methods, and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 045001 (2019).

Zheng, Y., Campbell, S., De Chiara, G. & Poletti, D. Cost of counterdiabatic driving and work output. Phys. Rev. A 94, 042132 (2016).

Campbell, C., Li, J., Busch, T. & Fogarty, T. Quantum control and quantum speed limits in supersymmetric potentials. New J. Phys 24, 095001 (2022).

Gessner, M. & Smerzi, A. Statistical speed of quantum states: Generalized quantum Fisher information and Schatten speed. Phys. Rev. A 97, 022109 (2018).

Rosal, A. J., Soares-Pinto, D. O. & Pires, D. P. Quantum speed limits based on Schatten norms: Universality and tightness. Phys. Lett. A 534, 130250 (2025).

Wang, H. & Qiu, X. Generalized coherent quantum speed limits. arXiv:2401.01746 (2024).

Campbell, S. & Deffner, S. Trade-off between speed and cost in shortcuts to adiabaticity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 100601 (2017).

Zhang, J.-W. et al. Single-atom verification of the optimal trade-off between speed and cost in shortcuts to adiabaticity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 213602 (2024).

Yadin, B., Imai, S. & Gühne, O. Quantum speed limit for states and observables of perturbed open systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 230404 (2024).

Shen, Y., Wang, P., Cheung, C. T., Wrachtrup, J., Liu, R.-B. & Yang, S. Detection of quantum signals free of classical noise via quantum correlation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 070802 (2023).

Pires, D. P., deAzevedo, E. R., Soares-Pinto, D. O., Brito, F. & Filgueiras, J. G. Experimental investigation of geometric quantum speed limits in an open quantum system. Commun. Phys. 7, 142 (2024).

Meng, W. & Xu, Z. Quantum speed limits in arbitrary phase spaces. Phys. Rev. A 107, 022212 (2023).

Cui, J.-M., Gómez-Ruiz, F. J., Huang, Y.-F., Li, C.-F., Guo, G.-C. & del Campo, A. Experimentally testing quantum critical dynamics beyond the Kibble–Zurek mechanism. Commun. Phys. 3, 44 (2020).

Wang, J.-F. et al. Coherent control of nitrogen-vacancy center spins in silicon carbide at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 223601 (2020).

Guo, N.-J., Li, S., Liu, W., Yang, Y.-Z., Zeng, X.-D., Yu, S., Meng, Y., Li, Z.-P., Wang, Z.-A. & Xie, L.-K. et al. Coherent control of an ultrabright single spin in hexagonal boron nitride at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 14, 2893 (2023).

Yan, F.-F., Yi, A.-L., Wang, J.-F., Li, Q., Yu, P., Zhang, J.-X., Gali, A., Wang, Y., Xu, J.-S. & Ou, X. et al. Room-temperature coherent control of implanted defect spins in silicon carbide. npj Quantum Inf. 6, 38 (2020).

Wang, J.-F., Liu, L., Liu, X.-D., Li, Q., Cui, J.-M., Zhou, D.-F., Zhou, J.-Y., Wei, Y., Xu, H.-A. & Xu, W. et al. Magnetic detection under high pressures using designed silicon vacancy centres in silicon carbide. Nat. Mater. 22, 489–494 (2023).

Auffèves, A. Quantum technologies need a quantum energy initiative. PRX Quantum 3, 020101 (2022).

Girolami, D. Observable measure of quantum coherence in finite dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 170401 (2014).

Yuan, H. Sequential feedback scheme outperforms the parallel scheme for Hamiltonian parameter estimation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 160801 (2016).

Streltsov, A., Adesso, G. & Plenio, M. B. Colloquium: Quantum coherence as a resource. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 041003 (2017).

Marvian, I. & Spekkens, R. W. Extending noether’s theorem by quantifying the asymmetry of quantum states. Nat. Commun. 5, 3821 (2014).

Yu, M., Liu, Y., Yang, P., Gong, M., Cao, Q., Zhang, S., Liu, H., Heyl, M., Ozawa, T. & Goldman, N. et al. Quantum Fisher information measurement and verification of the quantum Cramér–Rao bound in a solid-state qubit. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 56 (2022).

Baumgratz, T., Cramer, M. & Plenio, M. B. Quantifying coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 140401 (2014).

Zhang, J. W., Yan, L.-L., Li, J. C., Ding, G. Y., Bu, J. T., Chen, L., Su, S.-L., Zhou, F. & Feng, M. Single-atom verification of the noise-resilient and fast characteristics of universal nonadiabatic noncyclic geometric quantum gates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 030502 (2021).

Carlini, A., Hosoya, A., Koike, T. & Okudaira, Y. Time-optimal quantum evolution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 060503 (2006).

Dong, Y., Feng, C., Zheng, Y., Chen, X.-D., Guo, G.-C. & Sun, F.-W. Fast high-fidelity geometric quantum control with quantum brachistochrones. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043177 (2021).

Yang, W., Ma, W.-L. & Liu, R.-B. Quantum many-body theory for electron spin decoherence in nanoscale nuclear spin baths. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 016001 (2016).

Zhao, N., Ho, S.-W. & Liu, R.-B. Decoherence and dynamical decoupling control of nitrogen vacancy center electron spins in nuclear spin baths. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115303 (2012).

Maze, J. R., Dréau, A., Waselowski, V., Duarte, H., Roch, J.-F. & Jacques, V. Free induction decay of single spins in diamond. New J. Phys 14, 103041 (2012).

Wang, J. et al. High-sensitivity temperature sensing using an implanted single nitrogen-vacancy center array in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 91, 155404 (2015).

Herb, K. & Degen, C. L. Quantum speed limit in quantum sensing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 210802 (2024).

Dong, Y., Feng, C., Zhang, S.-C., Zheng, Y., Chen, X.-D., Guo, G.-C. & Sun, F.-W. Breaking the measurement-sensitivity–maximum-range limit of quantum metrology using two sequences. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 064022 (2023).

Du, J., Shi, F., Kong, X., Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Single-molecule scale magnetic resonance spectroscopy using quantum diamond sensors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 025001 (2024).

Ma, W.-L. & Liu, R.-B. Angstrom-resolution magnetic resonance imaging of single molecules via wave-function fingerprints of nuclear spins. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 024019 (2016).

Dong, Y., Zheng, Y., Li, S., Li, C.-C., Chen, X.-D., Guo, G.-C. & Sun, F.-W. Non-Markovianity-assisted high-fidelity Deutsch–Jozsa algorithm in diamond. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 3 (2018).

Haase, J. F., Vetter, P. J., Unden, T., Smirne, A., Rosskopf, J., Naydenov, B., Stacey, A., Jelezko, F., Plenio, M. B. & Huelga, S. F. Controllable non-Markovianity for a spin qubit in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 060401 (2018).

Lu, Y.-N., Zhang, Y.-R., Liu, G.-Q., Nori, F., Fan, H. & Pan, X.-Y. Observing information backflow from controllable non-Markovian multichannels in diamond. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 210502 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0303200), CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (Grant No. YSBR-049), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52130510, 62225506, and 62305324), and the Key Research and Development Plan of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BE2022066-2). D. P. P. and D. O. S. P. would like to acknowledge the Brazilian ministries MEC and MCTIC, and the Brazilian funding agencies CNPq, and Coordena¸c~ao de Aperfei¸coamento de Pessoal de N´ıvel Superior-Brasil (CAPES) (Finance Code 001). The sample preparation was partially conducted at the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.D., and F.-W.S. conceived the idea. F.-W.S. supervised the project. W.J. fabricate diamond samples. Y.D. performed the experiments. Y.D., D. P. P., and D. O. S. P. wrote the manuscript, with input and corrections from all authors. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and corrected multiple iterations of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Y., Jiang, W., Liu, ZW. et al. Experimental investigation of the trade-off between quantum speed and energy cost. npj Quantum Inf 11, 199 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01149-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-025-01149-z