Abstract

Cognitive impairment is a core symptom of schizophrenia (SZ), with GABAergic dysfunction in the brain potentially serving as a critical pathological mechanism underlying this condition. Intracortical inhibition (ICI), which includes short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) and long-interval intracortical inhibition (LICI), can be used to assess the inhibitory function of cortical GABAergic neurons. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between ICI and cognitive function, as well as psychopathological symptoms, in SZ patients. We recruited 130 SZ patients and 105 healthy controls (HCs). All subjects underwent paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (ppTMS) measurements, which included resting motor threshold (RMT), SICI and LICI. The cognitive function of all subjects was assessed using the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). The psychopathological symptoms of the SZ group were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). We examined group differences in MCCB scores, RMT, SICI, and LICI. Within the SZ group, we assessed the relationship between ICI and cognitive function, as well as psychopathological symptoms. Two-way ANOVA, Mann–Whitney U test, Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and partial Spearman correlation analysis were performed. The SZ group showed a worse cognitive score in all 6 cognitive dimensions of the MCCB compared to the HC group (all p < 0.05). The SZ group had lower degree of SICI and LICI compared to the HC group (both p < 0.05). ROC curves analysis showed that SICI and LICI all displayed good performance in differentiating SZ patients and HCs (both p < 0.05), and SICI exhibited a better performance, yielding an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.856 (95% CI 0.807–0.904). Furthermore, in the SZ group, SICI demonstrated a significant negative correlation with PANSS positive score, negative score, general psychopathology score, and total score (all pBonferroni < 0.05), and LICI demonstrated a significant negative correlation with PANSS positive score, general psychopathology score and total score (all pBonferroni < 0.05). Additionally, in the SZ group, SICI demonstrated a significant positive correlation with speed of processing score, working memory score, verbal learning score, visual learning score, and reasoning and problem-solving score of the MCCB (all pBonferroni < 0.05), while LICI was only weakly positive correlated with speed of processing score of the MCCB (r = 0.247, p = 0.005, pBonferroni = 0.03). Our results demonstrate that the reduction of ICI could serve as a trait-dependent in-vivo biomarker of GABAergic deficits for SZ and related cognitive impairments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ), a chronic and debilitating disorder, affects approximately 1% of the world’s population, imposing significant burdens on patients and their families. The primary symptoms of SZ are categorized into positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive deficits1. Current research suggests that cognitive deficits may constitute the core symptom of SZ2,3, often present in the prodromal stage before the full manifestation of positive and negative symptoms4,5. Deficits in cognition exert serious adverse effects on the functional outcomes and long-term prognosis of patients with SZ6,7. However, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying cognitive deficits in SZ remain unclear.

Emerging evidence indicates that central GABAergic inhibitory interneuron (GI) dysfunction in the brain may be a critical pathological mechanism in the onset of SZ8,9. Postmortem brain studies have demonstrated a reduction in the number and density of parvalbumin-positive (PV+) GIs in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with SZ10,11,12. The most consistent finding is the functional impairment of PV+ GIs in layer 3 of the prefrontal cortex. Gamma (γ) oscillations, which are ubiquitous neuroelectric activities in the brain, are closely linked to cognitive processes13,14,15,16,17. Studies have shown that GABAergic inhibitory function is crucial for the generation of γ oscillations, with PV+ GIs playing a prominent role18.

Intracortical inhibition (ICI) is a paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (ppTMS)-based measure that can serve as an indicator of the inhibitory function of the cerebral cortex. Research has indicated that ICI can reflect the function of GIs in the cortex19,20. By adjusting the stimulation interval to 1–4 ms or 50–200 ms, short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) or long-interval intracortical inhibition (LICI) can be induced, respectively. Studies have found that SICI may reflect the effects of GABAA receptors, which induce rapid inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs)21, while LICI may reflect the effects of GABAB receptors, which induce slow IPSPs22.

Studies have indicated an association between SZ and altered ICI. However, conclusions have been varied23,24. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Lányi et al.25 has reported a robust inhibitory deficit in SICI among individuals diagnosed with SZ. However, the association between SZ and LICI, the effects of medication on ICI, and the association between ICI and cognitive function and other psychopathologies of SZ has not been thoroughly investigated. Preliminary studies have suggested that SICI may correlate with cognitive function in patients with SZ26,27. For instance, Takahashi et al.26 reported that SICI was negatively correlated with raw scores of the working memory component of the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS). Similarly, Mehta et al.27 found that SICI was negatively correlated with emotion processing and a global social cognition score. However, these studies involved small sample sizes and did not cover a more comprehensive range of cognitive dimensions as measured by the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS) Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB)28, which is a widely used cognitive assessment tool for SZ.

Based on the aforementioned research background, we hypothesize that ppTMS-based ICI may serve as a psychopathological marker of cognitive deficits in SZ. Our study has two primary aims: (1) to compare ICI and cognitive function between SZ patients and healthy controls (HCs), and (2) to explore the relationship between ICI, cognitive function, and psychopathological symptoms in SZ patients.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Patients were recruited from the Shanghai Pudong New Area Mental Health Center and the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Pudong New Area Mental Health Center (No. PDJWLL2021028), and all participants provided informed consent.

Participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) a diagnosis of SZ according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P)29; (2) aged between 18 and 60 years; (3) Han ethnicity; (4) right-handed; (5) had not taken benzodiazepines within the past 3 months; and (6) had not received transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or electroconvulsive therapy within the past 3 months. The exclusion criteria included: (1) pregnancy; (2) severe physical diseases; (3) any other major Axis I disorder; and (4) substance abuse or dependence. HCs were selected based on the absence of any major Axis I disorder diagnosis and no family history of mental disorders.

We recruited 130 SZ patients (male/female: 49/81; average age: 30.92 ± 9.56 years), with 70 from the Shanghai Pudong New Area Mental Health Center and 60 from the First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University. Among the SZ patients we enrolled, 46 were first-episode drug-naïve (FEDN), 84 were receiving stable dose of antipsychotic treatment, and the antipsychotics taken by the patients were all converted to chlorpromazine equivalent doses30. Additionally, we recruited 105 sex- and age-matched HCs (male/female: 48/57; average age: 30.39 ± 12.68 years), with 49 from Shanghai and 56 from Kunming.

Clinical assessments

Demographic and clinical data were collected using a self-designed questionnaire. Psychopathological symptoms were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)31,32, while cognitive functioning was evaluated using 6 cognitive dimensions of the MCCB. These dimensions included speed of processing, working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, reasoning and problem-solving, and social cognition. Both assessors underwent thorough training on these scales, achieving an inter-rater concordance of over 0.8.

Measurement of ICI

We used the same model of TMS machine (NS5000, YIRUIDE Group, CN) and set the same parameters in both Shanghai and Kunming sites. Subjects were seated in a comfortable chair with a headrest to stabilize their head position throughout the procedure, with their arms passively supported. An electrode was placed on the right first flexor pollicis brevis muscle to record electromyograms. Single and paired-pulse stimulation was administered using a 60-mm figure-of-eight coil, with the maximum magnetic field strength at the center being 3.5T. The coil was held tangentially to the hand area of the left motor cortex, with the handle oriented backward and away from the midline at a 45° lateral angle.

Electromyography (EMG) recordings were acquired using the YIRUIDE system. The stimulation site that produced the largest Motor Evoked Potential (MEP) in the right first flexor pollicis brevis muscle was marked to ensure a consistent coil position throughout the experiment. The resting motor threshold (RMT) was defined as the lowest intensity that produced MEPs with a peak-to-peak amplitude of greater than 50 μV in at least five out of ten trials.

Measurement of target MEP: the target MEP was obtained with a stimulus intensity set to 120% of RMT, recording 5 stimulations and calculating the average value.

Measurement of SICI: a pre-stimulus (80% of RMT) was administered 2 milliseconds before the target stimulus (120% of RMT)33, recording 5 stimulations and calculating the average value as MEP1. SICI was calculated using the formula: [1 − (MEP1/target MEP)] * 100%.

Measurement of LICI: a pre-stimulus (120% of RMT) was administered 150 milliseconds before the target stimulus (120% of RMT)34, recording 5 stimulations and calculating the average value as MEP2. LICI was calculated using the formula: [1 − (MEP2/ target MEP)] * 100%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 25.0. Continuous variables were initially assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov one-sample test. The normally distributed demographic data were compared using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and described as mean ± standard deviation, whereas non-normally distributed data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. The categorical variables between groups were compared using the Chi-square test/Fisher exact test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were utilized to explore the potential of using ICI factors as biomarkers to differentiate between SZ patients and HCs. Correlations between PANSS scores, MCCB scores, and ICI were evaluated using partial Spearman correlation analysis. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (two-tailed).

Results

Demographic, ICI, and clinical characteristics between patients and HCs

The proportion of SZ patients recruited in Shanghai is not significantly different from that of the subjects recruited in Kunming (χ2 = 1.20, p = 0.296). The demographic data of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. No significant differences in age, education, or sex distribution were observed between the SZ patient group and the healthy control group (all p > 0.05). SZ patients displayed worse cognitive scores of the MCCB compared to HCs, including lower scores in speed of processing, working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, reasoning and problem-solving, and social cognition (all p < 0.05). Additionally, SZ patients exhibited a lower degree of both SICI and LICI compared to HCs (both p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the RMT between SZ patients and HCs (p > 0.05). Aside from significant differences in age and illness duration, no other demographic information or clinical characteristics showed statistical differences between the FEDN SZ group and the medicated SZ group.

SICI performs better than LICI in discriminating SZ patients from HCs as a biomarker

ROC curves were analyzed to evaluate the diagnostic value of SICI and LICI for distinguishing SZ patients from HCs. As depicted in Fig. 1, both SICI and LICI demonstrated acceptable area under the curve (AUC) for classifying SZ patients and HCs (both p < 0.05). The cutoff for SICI was 22.00 (AUC: 0.856, 95% CI: 0.807–0.904) with 68.6% sensitivity and 89.2% specificity (p < 0.001). The cutoff for LICI was 19.60 (AUC: 0.730, 95% CI: 0.665–0.795) with 68.6% sensitivity and 73.8% specificity (p < 0.001).

Relationship between ICI and psychopathological symptoms in SZ patients

As shown in Fig. 2, controlling the age as covariate, partial Spearman correlation analysis showed that SICI was negative associated with PANSS positive score, negative score, general psychopathology score and total score in SZ patients (r = −0.226, p = 0.002, pBonferroni = 0.008; r = −0.278, p = 0.001; pBonferroni = 0.004; r = −0.311, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05; r = −0.316, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05, respectively). As shown in Fig. 3, controlling the age as covariate, partial Spearman correlation analysis showed that LICI was negative associated with PANSS positive score, general psychopathology score and total score in SZ patients (r = −0.222, p = 0.011, pBonferroni = 0.044; r = −0.289, p = 0.001, pBonferroni = 0.004; r = −0.257, p = 0.003, pBonferroni = 0.012, respectively). While, LICI was not associated with PANSS negative score in SZ patients after Bonferroni correction (r = −0.180, p = 0.041, pBonferroni = 0.164).

a There were significant negative association between SICI and PANSS positive score (r = −0.266, p = 0.002, pBonferroni = 0.008). b There were significant negative association between SICI and PANSS negative score (r = −0.278, p = 0.001, pBonferroni = 0.004). c There were significant negative association between SICI and PANSS general psychopathology score (r = −0.311, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05). d There were significant negative association between SICI and PANSS total score (r = −0.316, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05).

a There were significant negative association between LICI and PANSS positive score (r = −0.222, p = 0.011, pBonferroni = 0.044). b There were no significant negative association between LICI and PANSS negative score (r = -0.180, p = 0.041, pBonferroni > 0.05). c There were significant negative association between LICI and PANSS general psychopathology score (r = −0.289, p = 0.001, pBonferroni = 0.004). d There were significant negative association between LICI and PANSS total score (r = −0.257, p = 0.003, pBonferroni = 0.012).

Relationship between ICI and cognitive function in SZ patients

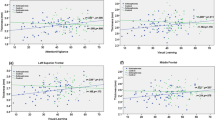

Controlling for age as a covariate, partial Spearman correlation analysis revealed no significant relationship between SICI and MCCB social cognition score in SZ patients (r = 0.147, p = 0.095). Similarly, controlling for age as a covariate, partial Spearman correlation analysis showed no significant relationship between LICI and working memory score, verbal learning score, visual learning score, reasoning and problem-solving score, or social cognition score of the MCCB in SZ patients (all p > 0.05). As illustrated in Fig. 4, controlling for age as a covariate, partial Spearman correlation analysis indicated a positive association between SICI and speed of processing score, working memory score, verbal learning score, visual learning score, and reasoning and problem-solving score of the MCCB in SZ patients (r = 0.552, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05; r = 0.418, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05; r = 0.325, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05; r = 0.304, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05; r = 0.337, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05, respectively), while, LICI was positively associated with MCCB speed of processing score (r = 0.247, p = 0.005, pBonferroni = 0.03), only.

a There were significant positive association between SICI and MCCB speed of processing score (r = 0.552, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05). b There were significant positive association between SICI and MCCB working memory score (r = 0.418, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05). c There were significant positive association between SICI and MCCB verbal learning score (r = 0.325, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05). d There were significant positive association between SICI and MCCB visual learning score (r = 0.304, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05). e There were significant positive association between SICI and MCCB reasoning and problem-solving score (r = 0.337, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.05). f There were significant positive association between LICI and MCCB speed of processing score (r = 0.247, p = 0.005, pBonferroni = 0.03).

Correlations between ICI and clinical characteristics in FEDN SZ and medicated SZ patients

Partial Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between ICI and clinical characteristics in FEDN SZ and medicated SZ patients, controlling for age (Table 2). In both groups, no significant correlation was found between ICI and illness course or chlorpromazine equivalent dose (both p > 0.05). After Bonferroni correction, we found a significant negative correlation between SICI and the PANSS positive score in the FEDN SZ patient group (r = −0.418, p = 0.004, pBonferroni = 0.016). Additionally, in the medicated SZ patient group, significant negative correlations were found between SICI and the PANSS general psychopathology score and total score after Bonferroni correction (r = −0.289, p = 0.008, pBonferroni = 0.032; r = −0.279, p = 0.011, pBonferroni = 0.044, respectively). After Bonferroni correction, we found a significant positive correlation between SICI and speed of processing score, working memory score, verbal learning score and problem-solving score of the MCCB in the FEDN SZ patient group (r = 0.548, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.01; r = 0.593, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.01; r = 0.409, p = 0.005, pBonferroni = 0.030; r = 0.497, p = 0.001, pBonferroni = 0.006, respectively). In the medicated SZ patient group, significant positive correlations were found between SICI and speed of processing score and working memory score of the MCCB after Bonferroni correction (r = 0.510, p < 0.001, pBonferroni < 0.01; r = 0.321, p = 0.003, pBonferroni = 0.018, respectively).

Discussion

The main findings of the present study can be summarized as follows: (1) SZ patients exhibited a lower degree of SICI and LICI compared to HCs. Furthermore, SICI demonstrated superior diagnostic value for distinguishing between SZ patients and HCs compared to LICI. (2) The degree of ICI was associated with psychopathological symptoms in SZ patients; (3) The degree of ICI was also associated with cognitive function in SZ patients; (4) Antipsychotic treatment may not impact the degree of ICI in SZ patients.

We observed a significantly reduced degree of SICI in SZ patients, and SICI exhibited better discriminatory performance for distinguishing between patients and HCs, which is consistent with findings from previous related studies26,35,36,37. For instance, Mehta et al. reported lower SICI in both acute episode SZ and chronic SZ patients compared to HCs, suggesting the potential utility of SICI as a biomarker for SZ27. This finding is further supported by some meta-analysis that focused on SICI in SZ patients22,25. However, some studies did not find reduced SICI in patients38,39. Fitzgerald et al.38 and Peter et al.39 reported non-significant differences in SICI among their patient cohorts, which may be attributed to confounding factors such as patient characteristics, disease heterogeneity, sample size, illness duration, and medication status. Additionally, we observed a significantly reduced degree of LICI in SZ patients, although it has a lower specificity in discriminating patients from HCs. Our findings confirmed previous meta-analysis results22,25, while providing novel evidence supporting LICI deficits in SZ patients with a larger sample size from two independent sites. Overall, our results confirmed the validity of using ICI as biomarkers for SZ.

Few studies have explored the relationships between ICI and the psychopathologies of SZ. For example, Wobrock et al.36 reported a negative correlation between cortical inhibition and total PANSS score, and Liu et al.37 found that SICI was inversely associated with positive symptoms. In our present study, we discovered that SICI was negatively correlated with PANSS positive, negative, general psychopathology, and total score in SZ patients, while LICI was negatively correlated with PANSS positive, general psychopathology, and total score in patients. This suggests that reduced cortical inhibition is inversely associated with symptom severity in SZ patients, a finding consistent with prior studies. Our results imply a stable correlation between symptom severity and deficits in both SICI and LICI. Therefore, our observation of decreased ICI in SZ patients may represent a characteristic marker of psychopathology. Future research should focus on replicating these findings and further exploring the nature of this relationship.

Our study found that the cognitive performance in 6 dimensions of the MCCB (speed of processing score, working memory score, verbal learning score, visual learning score, reasoning and problem-solving score, and social cognition score) were significantly impaired in SZ patients. SICI was positively associated with the performance in speed of processing, working memory, verbal learning, visual learning, and reasoning and problem-solving, while LICI was positively associated with speed of processing only. Our results support that abnormal ICI may be the neurophysiological mechanisms of cognitive impairment in SZ patients and may affect different cognitive dimensions through different neural or regional circuits. γ oscillation in the brain is a neurophysiological feature observed in cognitive activities40, which is closely related to cognitive processes, such as sensation and perception, information storage, retrieval, and encoding13,14. Especially, γ oscillation exhibits a prominent role in learning and memory15,16,17. Studies have found that GABAergic inhibitory function plays an important role in the generation of γ oscillation18, with PV+ GI playing a prominent role. Abnormal γ oscillation in the prefrontal cortex of SZ patients has been widely reported18. Animal experiments have found that activation and inhibition of PV+ GI in mice brains can selectively enhance and inhibit γ oscillation, respectively41,42. The frequency of γ oscillation is determined primarily by GABAA receptor-induced inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSC)43. While SICI is mainly influenced by GABAA receptors and based on the induction of IPSPs44. And this mechanism may be the reason why SICI is related to more cognitive dimensions in our study, and supporting the validity of SICI as biomarker of cognitive deficits in SZ. In contrast, LICI, which is primarily determined by GABAB receptor-induced slow IPSCs, involves slower inhibitory effects due to the metabotropic nature of G protein-coupled GABAB receptors45. A few small sample size studies have explored the LICI alterations in SZ patients and demonstrated consistent deficits in the dorsal-lateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) using TMS-EEG (electroencephalography) paradigms, but failed to found significant changes in the motor cortex46. With a larger sample size, we found significant decrease in LICI and correlation with some dimensions of the symptoms and cognitive deficits in SZ, even at a smaller extent than SICI. These results indicate that GABAB receptors may also be involved in the pathogenesis of SZ, possibly through a more distal pathway than GABAA receptors. Accordingly, prior studies have shown that LICI can inhibit the level of SICI through a presynaptic mechanism47, and hence may confer an indirect effect on the core pathological mechanisms of SZ.

To further explore whether ICI were trait or state dependent in SZ, and excluding the impacts of medication or illness course on ICI, we compared the ICI levels between FEDN SZ patients and medicated SZ patients. Additionally, we analyzed the correlation between ICI levels and chlorpromazine equivalent doses in medicated patients. As shown in Table 2, both medication and illness course had no significant correlation with SICI or LICI, while SICI was significantly correlated with multiple dimensions of the psychopathology and cognitive characteristics in both FEDN SZ patients and medicated SZ patients. Our result aligns with a 2024 meta-analysis25, which found no significant association between SICI and medication status or dosage. However, their conclusions were limited by differences in the characteristics of included cases and the lack of information on benzodiazepine using. Benzodiazepine treatment is known to enhance SICI23. To control for this variable, our inclusion criteria mandated that all participants should not use benzodiazepines within the three months prior to enrollment. Furthermore, the FEDN patients in our study were used to control for medication and illness course derived changes in ICI. Based on these findings, we may conclude that ICI, especially SICI, may serve as a stable trait dependent biomarker for SZ and the GABA-inhibition related cognitive deficits.

There were several limitations in this study. Firstly, the measurement of ICI was limited to the motor cortex rather than brain regions more closely related to SZ. Therefore, our findings may not fully capture the whole pathophysiological mechanisms of SZ. Additionally, even we have enrolled the largest sample size as far as we know in this research field, the limited sample size may have constraints the statistical power, especially in the stratification analyses for LICI correlations. Therefore, future research with larger longitudinal cohorts is needed to confirm and extend our findings.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the reduction of ICI could serve as a trait-dependent in-vivo biomarker of GABAergic deficits for SZ and related cognitive impairments.

Data availability

The authors declare that all relevant data of this study are available within the article or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- dlPFC:

-

Dorsal-lateral prefrontal cortex

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- EMG:

-

Electromyography

- FEDN:

-

First-episode drug-naïve

- GI:

-

GABAergic inhibitory interneurons

- HCs:

-

Healthy controls

- ICI:

-

Intracortical inhibition

- IPSP:

-

Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials

- IPSC:

-

Inhibitory postsynaptic currents

- LICI:

-

Long-interval intracortical inhibition

- MATRICS:

-

Measurement and treatment research to improve cognition in schizophrenia

- MCCB:

-

MATRICS consensus cognitive battery

- MEP:

-

Motor evoked potential

- NA:

-

Not available

- PANSS:

-

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- ppTMS:

-

Paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation

- PV+ :

-

Parvalbumin-positive

- RMT:

-

Resting motor threshold

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SCID-I/ P:

-

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SICI:

-

Short-interval intracortical inhibition

- SZ:

-

Schizophrenia

References

Zhu, MH., Liu, ZJ., Hu, QY., Yang, JY., Jin, Y. & Zhu, N. et al. Amisulpride augmentation therapy improves cognitive performance and psychopathology in clozapine-resistant treatment-refractory schizophrenia: a 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Mil. Med. Res. 9, 59 (2022).

Geyer, M. A., Olivier, B., Joels, M. & Kahn, R. S. From antipsychotic to anti-schizophrenia drugs: role of animal models. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 515–521 (2012).

Young, J. W. & Geyer, M. A. Developing treatments for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: the challenge of translation. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 178–196 (2015).

Green, M. F., Kern, R. S., Braff, D. L. & Mintz, J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull. 26, 119–136 (2000).

Furth, K. E., Mastwal, S., Wang, K. H., Buonanno, A. & Vullhorst, D. Dopamine, cognitive function, and gamma oscillations: role of D4 receptors. Front. Cell Neurosci. 7, 102 (2013).

Xue, K. K. et al. Impaired large-scale cortico-hippocampal network connectivity, including the anterior temporal and posterior medial systems, and its associations with cognition in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1167942 (2023).

Mihaljevic-Peles, A. et al. Cognitive deficit in schizophrenia: an overview. Psychiatr. Danub. 31, 139–142 (2019).

Schmidt, M. J. & Mirnics, K. Neurodevelopment, GABA system dysfunction, and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 190–206 (2015).

Cadinu, D. et al. NMDA receptor antagonist rodent models for cognition in schizophrenia and identification of novel drug treatments, an update. Neuropharmacology 142, 41–62 (2018).

Beasley, C. L. & Reynolds, G. P. Parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons are reduced in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Schizophr. Res. 24, 349–355 (1997).

Beasley, C. L., Zhang, Z. J., Patten, I. & Reynolds, G. P. Selective deficits in prefrontal cortical GABAergic neurons in schizophrenia defined by the presence of calcium-binding proteins. Biol. Psychiatry 52, 708–715 (2002).

Lewis, D. A., Hashimoto, T. & Volk, D. W. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 312–324 (2005).

Doiron, B., Litwin-Kumar, A., Rosenbaum, R., Ocker, G. K. & Josic, K. The mechanics of state-dependent neural correlations. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 383–393 (2016).

Colgin, L. L. Rhythms of the hippocampal network. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 239–249 (2016).

Csicsvari, J., Jamieson, B., Wise, K. D. & Buzsaki, G. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron 37, 311–322 (2003).

Voytek, B. et al. Oscillatory dynamics coordinating human frontal networks in support of goal maintenance. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1318–1324 (2015).

Honkanen, R., Rouhinen, S., Wang, S. H., Palva, J. M. & Palva, S. Gamma oscillations underlie the maintenance of feature-specific information and the contents of visual working memory. Cereb. Cortex 25, 3788–3801 (2015).

Uhlhaas, P. J. & Singer, W. Abnormal neural oscillations and synchrony in schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 100–113 (2010).

Assogna, M. et al. Effects of palmitoylethanolamide combined with luteoline on frontal lobe functions, high frequency oscillations, and GABAergic transmission in patients with frontotemporal dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 76, 1297–1308 (2020).

McClintock, S. M., Freitas, C., Oberman, L., Lisanby, S. H. & Pascual-Leone, A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a neuroscientific probe of cortical function in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 19–27 (2011).

Di Lazzaro, V. et al. GABAA receptor subtype specific enhancement of inhibition in human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 575, 721–726 (2006).

Radhu, N. et al. A meta-analysis of cortical inhibition and excitability using transcranial magnetic stimulation in psychiatric disorders. Clin. Neurophysiol. 124, 1309–1320 (2013).

di Hou, M., Santoro, V., Biondi, A., Shergill, S. S. & Premoli, I. A systematic review of TMS and neurophysiological biometrics in patients with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 46, E675–E701 (2021).

Kaskie, R. E. & Ferrarelli, F. Investigating the neurobiology of schizophrenia and other major psychiatric disorders with Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Schizophr. Res. 192, 30–38 (2018).

Lanyi, O. et al. Excitation/inhibition imbalance in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of inhibitory and excitatory TMS-EMG paradigms. Schizophrenia 10, 56 (2024).

Takahashi, S. et al. Reduction of cortical GABAergic inhibition correlates with working memory impairment in recent onset schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 146, 238–243 (2013).

Mehta, U. M., Thirthalli, J., Basavaraju, R. & Gangadhar, B. N. Association of intracortical inhibition with social cognition deficits in schizophrenia: findings from a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Schizophr. Res. 158, 146–150 (2014).

Nuechterlein, K. H. et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 203–213 (2008).

First, M., Spitzer, R., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV® Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2012).

Woods, S. W. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J. Clin. Psychiatry 64, 663–667 (2003).

Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. et al. Cognition and the five-factor model of the positive and negative syndrome scale in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 143, 77–83 (2013).

Wallwork, R. S., Fortgang, R., Hashimoto, R., Weinberger, D. R. & Dickinson, D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 137, 246–250 (2012).

Kujirai, T. et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 471, 501–519 (1993).

Valls-Sole, J., Pascual-Leone, A., Wassermann, E. M. & Hallett, M. Human motor evoked responses to paired transcranial magnetic stimuli. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 85, 355–364 (1992).

Daskalakis, Z. J. et al. Evidence for impaired cortical inhibition in schizophrenia using transcranial magnetic stimulation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 347–354 (2002).

Wobrock, T. et al. Reduced cortical inhibition in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 105, 252–261 (2008).

Liu, S. K., Fitzgerald, P. B., Daigle, M., Chen, R. & Daskalakis, Z. J. The relationship between cortical inhibition, antipsychotic treatment, and the symptoms of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 65, 503–509 (2009).

Fitzgerald, P. B., Brown, T. L., Daskalakis, Z. J. & Kulkarni, J. A transcranial magnetic stimulation study of the effects of olanzapine and risperidone on motor cortical excitability in patients with schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 162, 74–81 (2002).

Eichhammer, P. et al. Cortical excitability in neuroleptic-naive first-episode schizophrenic patients. Schizophr. Res. 67, 253–259 (2004).

Canali, P. et al. Shared reduction of oscillatory natural frequencies in bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia. J. Affect. Disord. 184, 111–115 (2015).

Cardin, J. A. et al. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459, 663–667 (2009).

Sohal, V. S., Zhang, F., Yizhar, O. & Deisseroth, K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 459, 698–702 (2009).

Guan, A. et al. The role of gamma oscillations in central nervous system diseases: mechanism and treatment. Front. Cell Neurosci. 16, 962957 (2022).

Kuo, H. I. et al. Acute and chronic noradrenergic effects on cortical excitability in healthy humans. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20, 634–643 (2017).

Timothy, R. R. & Kevin, W. Mechanisms and regulation of neuronal GABA(B) receptor-dependent signaling. Curr. Top Behav. Neurosci. 52, 39–79 (2020).

Fatih, P. et al. A systematic review of long-interval intracortical inhibition as a biomarker in neuropsychiatric disorders. Front. Psychiatry 12, 678088 (2021).

Jason, C., Carolyn, G. & Robert C. Possible differences between the time courses of presynaptic and postsynaptic GABAB mediated inhibition in the human motor cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 184, 571–577 (2007).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participants for assessments and interviews in our research. This work was supported by Shanghai Pudong New Area Health Committee Disciplinary Leader Training Program (No. PWRd2021-06), Science and Technology Development Fund of Shanghai Pudong New Area (No. PKJ2021-Y17), Outstanding Clinical Discipline Project of Shanghai Pudong (Nos. PWZzk2022-19, PWYgy2021-02), and the Clinical Research Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (No. 20204Y0173). All funding had no role in study design, data analysis, paper submission and publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xudong Zhao and Weiqing Liu were responsible for the study concept and design, as well as for revising and editing the manuscript. Minghuan Zhu, Yifan Xu, Qi Zhang, Xiaoyan Cheng, Lei Zhang, Fengzhi Tao, Jiali Shi, Xingjia Zhu and Zhihui Wang collected the data. Minghuan Zhu prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors have contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, M., Xu, Y., Zhang, Q. et al. Reduction of intracortical inhibition (ICI) correlates with cognitive performance and psychopathology symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr 10, 78 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00491-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00491-z