Abstract

Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder present burdens to patients and health systems through elevated healthcare resource utilization (HCRU) and costs. However, there is a paucity of evidence describing these burdens across payor types. To identify unmet needs, this study characterized patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder by payor type. We identified patients aged 12–94 years with newly diagnosed schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (index date) between 01/01/2014 and 08/31/2020 with continuous enrollment for 12 months before and after index date from the Healthcare Integrated Research Database. After stratifying by post-index relapse frequency (0, 1, or ≥2) and payor type (commercial, Medicare Advantage/Supplemental (Medigap)/Part D, or managed Medicaid), we examined patient characteristics, treatment patterns, HCRU, costs, and relapse patterns and predictors. During follow-up, 25% of commercial patients, 29% of Medicare patients, and 37% of Medicaid patients experienced relapse. Atypical antipsychotic discontinuation was most common among Medicaid patients, with 65% of these patients discontinuing during follow-up. Compared to commercial patients, Medicare and Medicaid patients had approximately half as many psychotherapy visits during follow-up (12 vs. 5 vs. 7 visits, respectively). Relative to baseline, average unadjusted all-cause costs during follow-up increased by 105% for commercial patients, 66% for Medicare patients, and 77% for Medicaid patients. Patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder had high HCRU and costs but consistently low psychotherapy utilization, and they often discontinued pharmacologic therapy and experienced relapse. These findings illustrate the high burden and unmet need for managing these conditions and opportunities to improve care for underserved patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are complex psychiatric conditions that present considerable challenges for patients and health systems. Within a given year in the United States (US), schizophrenia occurs with a prevalence of 0.3–1.6% in the general population and more frequently among vulnerable subgroups, such as among Medicaid enrollees where the annual prevalence ranges from 2.3–2.7%1,2,3,4. Large-scale epidemiologic data on schizoaffective disorder in the US are lacking, but limited evidence from abroad suggests a lifetime prevalence of 0.3%5. In addition, there is considerable overlap between how the two conditions present in terms of cognitive, social cognitive, and neural measures, so findings specific to patients with schizophrenia may also inform our understanding of schizoaffective disorder6. While relatively rare, these conditions are associated with substantial healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). For example, the annual rates of inpatient and emergency room (ER) admissions among commercially insured patients with schizophrenia in the US are more than 13 times the rates among those without schizophrenia7. As a direct result of high HCRU as well as other indirect consequences (e.g., disability-related caregiving and unemployment), the cost of schizophrenia in the US reached an estimated $343.2 billion in 20198. To mitigate the health and economic burdens schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder pose to patients and health systems, efforts are needed to more effectively manage and treat these conditions.

Current guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder recommend person-centered treatment plans including both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic (i.e., psychosocial) interventions9,10. As a first-line pharmacologic intervention, patients can be treated with either first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) or second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). However, evidence suggests these medications may predominantly treat only the positive symptoms of the condition, potentially leaving the negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms untreated unless used in combination with psychotherapy or other non-pharmacologic interventions11,12. Moreover, pharmacologic interventions are often associated with serious and debilitating side effects, including extrapyramidal motor symptoms and tardive dyskinesia for FGAs and cardiometabolic adverse effects for SGAs13. As a result, treatment discontinuation and subsequent relapse (i.e., acute exacerbation of positive symptoms with psychotic break often resulting in ER visit or hospitalization) are common among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, with evidence suggesting up to 80% and 95% of patients relapse within 12 and 24 months of treatment discontinuation, respectively13,14,15,16.

Relapse is common and costly, therefore some studies have begun to explore patterns of relapse and the associated HCRU and costs14,17,18,19. However, if these findings are to be used to inform how schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder should be managed, more research is needed to better characterize these conditions among a broad, nationwide population of insured patients. Specifically, given the unique composition and needs of patients with different types of insurance, direct comparisons of characteristics between these distinct patient populations would be informative. For example, it is known that schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are more common among Medicaid enrollees relative to the general population, but there is a paucity of studies exploring how unmet needs for these patients may differ from those for commercial and Medicare enrollees. If such comparisons were available, efforts could be made to develop more cost-effective, payor-specific strategies to improve care. To address this gap and highlight opportunities to improve care, this study aimed to use claims data from a nationwide population of commercial-, Medicare-, and managed Medicaid-insured patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder to characterize these conditions by payor type in terms of patient characteristics, treatment patterns, HCRU, costs, and patterns and predictors of relapse.

Methods

This retrospective, observational cohort study used data from the Healthcare Integrated Research Database (HIRD), a geographically diverse longitudinal database of closed administrative medical and pharmacy claims. Included in the HIRD are data dating back to January 2006 from commercial, Medicare Advantage/Supplemental (Medigap)/Part D, and managed Medicaid health plan members across the US. We accessed these data in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and received an exemption from Institutional Review Board oversight requirements.

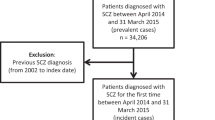

After stratifying by payor type, patients were potentially eligible for inclusion in the study if they had ≥1 inpatient/ER claim or ≥2 outpatient claims (between 30 and 183 days apart) with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder between 01 January 2014 and 31 August 2020 (patient identification period). The date of the first qualifying diagnosis was the index date. From the potentially eligible patients, the final sample included those who: (1) were aged 12–94 years on the index date, (2) did not have a neurocognitive disorder between 01 January 2013 and 31 August 2021 (study period), (3) did not have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder prior to the index date, and (4) had ≥12 months of continuous medical and pharmacy health plan enrollment both before and after the index date. See Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1 for details regarding the diagnosis codes and assessment periods used for sample selection.

In the 12 months following the index diagnosis, we considered a patient to have relapsed if they had either an ER visit claim with any diagnosis of a psychiatric condition or an inpatient hospitalization claim with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder20. To qualify as a unique relapse episode, the ER visit or inpatient hospitalization must have started ≥30 days following the index diagnosis for the first relapse or ≥14 days following the end of the prior relapse episode for all subsequent relapses21. For each payor type, we then stratified patients based on whether they had 0, 1, or ≥2 relapses during follow-up. See Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Fig. 2 for the diagnosis codes used to define relapse and illustrative examples. For patients in each stratum of relapse frequency and overall, we documented demographic characteristics on the index date and baseline clinical characteristics, HCRU, and costs in the 12-month period prior to the index date. In the 12-month period including and following the index date, we documented pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment patterns, overall and mental health-related HCRU and costs, and patterns and predictors of relapse. We calculated healthcare costs as the sum of health-plan-paid, patient-paid, and coordination-of-benefits (third-party payor-paid) costs adjusted to 2020 US dollars based on the most recent medical care price index information provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics22. See Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Table 3, and Supplemental Table 4 for relevant medication and diagnosis codes.

We reported means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and compared these statistics across relapse frequency strata for each payor type via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-squared tests. For each payor type, we constructed multivariable generalized linear models using a gamma distribution and log link function to estimate adjusted post-index costs by relapse frequency. We included age and sex in each model regardless of statistical significance; we selected all other variables using a bidirectional stepwise selection process requiring a p-value of 0.25 or lower to enter and stay in the model. To identify predictors of relapse, we first constructed three regression models using the same variable selection process as above separately for each payor type: (1) a logistic model of predictors of any post-index relapse, (2) a negative binomial model of time-invariant predictors of the number of post-index relapses, and (3) a Cox model of the time to first post-index relapse. We used the results of these models and a review of the literature to select the covariates to be included in our final model for predictors of relapse, which estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using time-varying multi-level logistic regression separately for each payor type. These models included time-invariant covariates measured at baseline and time-varying covariates measured quarterly to estimate the odds of relapse at the subsequent quarter.

Results

After applying the selection criteria, we identified 4974 commercially insured, 1660 Medicare, and 4858 Medicaid patients aged 12–94 years with newly diagnosed schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (Supplemental Table 5). Of the commercially insured patients, 75% had no relapses, 17% had 1 relapse, and 8% had ≥2 relapses during follow-up. The respective percentages were 71%, 16%, and 13% for Medicare patients and 63%, 19%, and 18% for Medicaid patients.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

In general, demographic and baseline clinical characteristics across payor types were reflective of the populations served (Table 1). The mean age was 55 years for Medicare patients versus 33 and 35 years for commercial and Medicaid patients, respectively. Medicaid patients tended to be of a lower socioeconomic status (SES), with 43% of Medicaid patients being in the lowest quartile of the SES index versus 17% of commercial patients and 28% of Medicare patients. While commercial patients were less likely to have comorbidities than Medicare and Medicaid patients, the prevalence of comorbidities increased with frequency of relapse across all payor types. Behavioral health comorbidities were particularly common, with anxiety disorders, depression, and bipolar disorder each diagnosed in ≥26% of patients across all strata of payor type and relapse frequency.

Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment patterns

Patients across all strata of payor type and relapse frequency displayed similar post-index pharmacologic treatment patterns (Table 2). The daily antipsychotic pill burden ranged from an average of 1.1–1.8 across all strata of payor type and relapse frequency and was consistently higher among patients with more relapses (all p < 0.001). Similarly, patients across all strata were more likely to have a fill for an atypical antipsychotic compared to other types of antipsychotics, and treatment with atypical antipsychotics was even more common among patients with more relapses (all p < 0.001). In addition, patients who were adherent to typical and atypical antipsychotics tended to have fewer relapses, and this was consistent across payor types (all p ≤ 0.002). However, the proportion of patients who discontinued use of an atypical antipsychotic within 12 months of their index diagnosis differed by payor type. Among those who had at least one fill for an atypical antipsychotic, the percentage of Medicaid patients who discontinued during follow-up was 7 percentage points higher than that of commercial patients and 24 percentage points higher than that of Medicare patients.

Commercial patients were the most likely to receive treatment through non-pharmacologic psychiatric services (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Among these patients, 77% had at least one non-pharmacologic treatment visit in the 12 months following their index diagnosis. This percentage was 51% for Medicare patients and 69% for Medicaid patients. This trend was also reflected in a 94% pre- to post-index increase in the average number of non-pharmacologic treatment visits for commercial patients, versus a 71% and 59% increase for Medicare and Medicaid patients, respectively. Access to psychotherapy in particular also varied by payor type and followed the same trend, with the number of patients who had at least one post-index psychotherapy visit accounting for 65%, 37%, and 46% of commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid patients, respectively. However, among those who had at least one visit, regular utilization of psychotherapy was consistently uncommon, with at least half of patients across all payor types having fewer than 10 psychotherapy visits during the 12-month follow-up period.

Healthcare Resource Utilization

Across all payor types, post-index inpatient hospitalizations, ER visits, outpatient visits, and prescription fills tended to increase with relapse frequency, though there were some differences in magnitude by payor type (Supplemental Table 6). For example, 58–87% of commercial patients across relapse strata had at least one all-cause inpatient hospitalization, compared to 46–82% of Medicare patients and 48–82% of Medicaid patients. In contrast, Medicaid patients were the most likely to have at least one all-cause ER visit (i.e., 46–95% versus 28–84% of commercial patients and 37–94% of Medicare patients). Trends for mental health-related utilization were similar. Comparing pre- and post-index utilization, Medicare patients had the greatest relative increase in the average number of inpatient and ER visits, while commercial patients had the greatest relative increase in the average number of outpatient office visits (Fig. 1).

Healthcare costs

The impact of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder on increasing healthcare costs was greatest for commercial patients and lowest for Medicare patients. Among commercial patients, the average unadjusted total costs in the 12 months following the index diagnosis increased by 105% compared to baseline costs, with greater increases observed among those with more relapses. In contrast, Medicare patients had a 66% increase and Medicaid patients had a 77% increase, but similarly observed greater increases among those with more relapses (Supplemental Table 7). For mental health-related costs, trends were similar with greater magnitude. In adjusted models, total post-index costs for commercial patients with ≥2 relapses were 143% higher than those with 0 relapses (cost ratio [CR] = 2.43, 95% CI = [2.21–2.68]). For the same comparison, the increase was 64% (CR = 1.64, 95% CI = [1.42–1.90]) for Medicare patients and 116% (CR = 2.16, 95% CI = [2.01–2.32]) for Medicaid patients (Fig. 2, Supplemental Tables 8–10).

Patterns and predictors of relapse

Characteristics of each relapse, up to four relapses, were similar across payor types (Supplemental Table 11). For example, for all payor types, there was little variation in the duration of relapse across episodes, with each relapse lasting about a week on average. The proportion of patients who were adherent to antipsychotics prior to relapse was low across all payor types and episodes (≤58%), but it was particularly low among Medicaid patients where adherence peaked at 42% prior to the first relapse and dropped to 34% prior to the fourth relapse. In contrast, patterns around cost of relapse differed by payor type. The average all-cause cost of the first relapse for commercial patients was 2.5 times the cost for Medicare patients and 3.5 times the cost for Medicaid patients. Trends for mental health-related costs were similar.

Many of the predictors of relapse were the same across all payor types (Fig. 3). The strongest predictor was consistently the index diagnosis location. Those first diagnosed in an inpatient or ER setting had more than 4 times the odds of relapse compared to those diagnosed in an outpatient setting (commercial: OR = 5.95, 95% CI = [5.32–6.66]; Medicare: OR = 5.93, 95% CI = [4.90–7.18]; Medicaid: OR = 4.13, 95% CI = [3.76–4.54]). Baseline comorbidities also predicted relapse, but the strongest of these predictors varied by payor type. For commercial patients, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was the strongest predictor (OR = 1.59, 95% CI = [1.24–2.05]); for Medicare patients, it was asthma (OR = 1.73, 95% CI = [1.40–2.14]); and for Medicaid patients, it was substance use disorder excluding alcohol use disorder and nicotine dependence (SUD) (OR = 1.32, 95% CI = [1.20–1.46]). Among the time-varying covariates, the number of prior relapses was the only consistently statistically significant predictor across payor types. For each additional prior relapse in each quarter, the odds of relapse in the subsequent quarter increased by 11% (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = [1.03–1.19]), 25% (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = [1.13–1.37]), and 34% (OR = 1.34, 95% CI = [1.28–1.41]) for commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid patients, respectively. Quarterly medication adherence significantly predicted relapse less consistently across payor types. For example, adherence to atypical antipsychotics in each quarter predicted a 15% lower odds of relapse in the subsequent quarter (OR = 0.85, 95% CI = [0.77–0.93]) for commercial patients. For Medicare (OR = 0.94, 95% CI = [0.80–1.10]) and Medicaid (OR = 0.97, 95% CI = [0.88–1.06]) patients, trends were similar but not statistically significant.

Discussion

This study identified patients with commercial, Medicare Advantage/Supplemental (Medigap)/Part D, or managed Medicaid health plans who had incident schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and described key characteristics and predictors of relapse by payor type. Overall, most patients did not have any relapses in the 12 months following their initial diagnosis, but relapse was most common among Medicaid patients. The majority of patients received atypical antipsychotic medications to treat their condition and adherence to typical and atypical antipsychotics over the duration of follow-up was bivariately associated with fewer relapses, but treatment discontinuation was common, especially among Medicaid patients. In addition, although current guidelines recommend both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments, less than half of Medicare and Medicaid patients received any psychotherapy and even fewer patients received psychotherapy regularly (i.e., 10+ visits in the 12 months following their index diagnosis). Overall, HCRU and costs consistently increased with relapse frequency. However, even among patients who had no relapses, the burden was considerable, with approximately half of these patients being hospitalized at least once after their index diagnosis regardless of payor type. Finally, while some characteristics were strong predictors of relapse across all payor types, others were less consistent. For example, having an index diagnosis in an inpatient or ER setting, having certain baseline comorbidities (i.e., nicotine dependence, suicidal ideation, and asthma), and the number of prior relapses consistently predicted an increased risk of relapse and being at least 45 years of age on the index date consistently predicted a reduced risk of relapse. In contrast, accounting for other predictors, time-varying medication adherence and other characteristics did not consistently predict relapse across payor types (e.g., quarterly adherence to atypical antipsychotics significantly predicted a reduced risk of relapse only for commercial patients).

Prior research has shown that, despite being rare, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder are associated with considerable HCRU and costs; our findings support and add nuance to this point7,8,23. For example, Nicholl and colleagues found that 22% of newly diagnosed commercial patients with schizophrenia were hospitalized during the 12 months following the index diagnosis23. We found this percentage was considerably higher (65%) and additionally observed similarly high utilization among Medicare and Medicaid patients (54% and 59%, respectively). Regarding costs, Kadakia and colleagues found that, on average, annual healthcare costs for patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder amounted to about $30,000 across payor types, with Medicare patients having the highest average cost at $34,3918. In contrast, we found average unadjusted total post-index costs to be highest among commercial patients (commercial: $43,412; Medicare: $29,970; Medicaid: $22,952). Given that we restricted our analysis to newly diagnosed patients while Kadakia and colleagues did not, this difference in findings may suggest that trends in costs across payor types vary at different points throughout the course of disease.

In addition, our findings provide valuable insights that may aid in hypothesis generation for research on the predictors of relapse. First, our findings corroborate conclusions from prior studies regarding the tendency for many patients with schizophrenia to be non-adherent to their antipsychotic medications13. Prior research has found non-adherence to be a significant predictor of relapse after first episode psychosis24,25, and results from our bivariate analyses align with this finding by showing that patients who were adherent to typical and atypical antipsychotics over the duration of follow-up tended to have fewer relapses. However, in our final predictive models, we found that quarterly measures of non-adherence to antipsychotic medications typically did not significantly predict relapse after accounting for other predictors. While this finding may be partially attributable to different study designs (e.g., length of follow-up) and definitions of non-adherence (e.g., time-invariant vs. time-varying) and relapse, it may also indicate a difference between patient populations that is worth exploring further. Specifically, for Medicare and Medicaid patients, we found adherence to any class of antipsychotic medication was not associated with a reduced risk of relapse. For commercial patients, however, we found adherence to atypical antipsychotics was associated with a lower risk of relapse. Therefore, while prior findings may be more aligned with our findings for the commercial population, the difference observed for Medicare and Medicaid patients highlights the importance of considering the unique aspects of different patient populations when aiming to characterize the nature of relapse. The utility of such information has been demonstrated in recent work that used knowledge about the predictors of relapse to inform the creation of a claims-based algorithm to identify high-risk patients and implement targeted interventions20. However, the sensitivity and positive predictive value of this algorithm were suboptimal and the authors acknowledged the need for further refinement of their algorithm. Given this context, our findings may be used to inform and improve such algorithms. For example, the previously published algorithm did not consider including baseline nicotine dependence, suicidal ideation, or asthma as potential predictors of relapse, but our findings suggest these conditions consistently predict relapse across all payor types, so their inclusion in future algorithms may be beneficial.

Our study also adds to the discussion around treatment by highlighting the consistently low use of non-pharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy, among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. In accordance with guidelines, an ideal treatment regimen should include such treatments to help address negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms that may otherwise go untreated by pharmacologic treatments alone9,10,11. However, even among commercial patients, where the average number of psychotherapy visits among those with at least one visit was approximately double that of Medicare and Medicaid patients, fewer than half of patients received psychotherapy regularly (i.e., 10+ visits in the 12 months following their index diagnosis). This highlights an important gap in real-world treatment practices and an opportunity to improve care by making psychotherapy more accessible to patients. Recent work from the United Kingdom found similarly low utilization of psychotherapy among an overall population of patients with first episode psychosis and even lower utilization among the subset of patients from racial/ethnic minority groups26. Within this context, our finding of less frequent use of psychotherapy among Medicare and Medicaid patients supports the idea that improvements in treatment access should be prioritized for demographically and socially vulnerable populations.

The results of this study should be interpreted with acknowledgement of its limitations. First, this study utilized data from administrative insurance claims. These claims are intended to be used for insurance payment purposes and not for research. Given the potential for administrative coding errors, non-compliance with prescribed medications, and lack of access to medical care, claims data may not reflect a patient’s full medical and treatment history. As a result, while this study used ER visits and inpatient hospitalizations as indicators of relapse, the relapse status of some patients may have been mischaracterized. Second, related to the issue of potentially missing or inaccurate data from claims, we attempted to identify patients with incident disease, but it is possible that the true onset of disease occurred prior to the first recorded claim for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in the HIRD. If this were the case, the 12 months of post-index data we used to characterize the patient would reflect trends from a later period in their disease trajectory rather than the first 12 months of disease as intended. Third, our estimates of the prevalence of relapse may be underestimates given that we did not capture relapse events that occurred outside of inpatient or ER settings. Fourth, a portion of our study period overlapped with the COVID-19 era, and trends in HCRU often fluctuated during this period27. As a result, data from patients who entered our study around this time may have skewed our HCRU results such that they do not perfectly reflect HCRU trends before and after the pandemic. However, the majority of patients in our study had their index diagnosis prior to this period, so the impacts of COVID-19 on our overall conclusions are likely modest.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a robust, in-depth assessment of patients with incident schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder across three different payor types in the US. Based on this assessment, the high burden of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and the unmet needs for patients with these conditions in the US are evident. Specifically, we found that patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder had high levels of comorbidities and HCRU. These patients incurred elevated costs but received suboptimal treatment (e.g., frequent treatment discontinuation and infrequent psychotherapy) and often experienced relapse, which suggests the need to further improve patient treatment options and outcomes. The low utilization of non-pharmacologic treatments among these patients also suggests that future studies should explore clinical and economic characteristics of patients who have symptoms best addressed through such treatments (i.e., patients with negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms) so that we can better understand this gap in care. In all of these findings, we also identified similarities and differences in trends by payor type (e.g., relapse was most common among Medicaid patients), thereby highlighting opportunities to inform disease management and care for these underserved patients according to the nuanced needs of different payor populations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Carelon Research, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data to external sources, and therefore they are not publicly available. Data may be made available through the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of Carelon Research.

References

Simeone, J. C., Ward, A. J., Rotella, P., Collins, J. & Windisch, R. An evaluation of variation in published estimates of schizophrenia prevalence from 1990-2013: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychiatry 15, 193 (2015).

Pilon, D. et al. Prevalence, incidence and economic burden of schizophrenia among Medicaid beneficiaries. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 37, 1811–1819 (2021).

Charlson, F. J. et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophr. Bull. 44, 1195–1203 (2018).

Schizophrenia and Psychosis Action Alliance. Societal Costs of Schizophrenia & Related Disorders (2021).

Perala, J. et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64, 19–28 (2007).

Hartman, L. I., Heinrichs, R. W. & Mashhadi, F. The continuing story of schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: one condition or two? Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 16, 36–42 (2019).

Fitch, K., Iwasaki, K. & Villa, K. F. Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. Am. Health Drug Benefits 7, 18–26 (2014).

Kadakia, A. et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States. J. Clin. Psychiatry 83, 43278 (2022).

Wy, T. J. P. & Saadabadi, A. In StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Keepers, G. A. et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 868–872 (2020).

Tsapakis, E. M., Dimopoulou, T. & Tarazi, F. I. Clinical management of negative symptoms of schizophrenia: an update. Pharm. Ther. 153, 135–147 (2015).

Goff, D. C., Hill, M. & Barch, D. The treatment of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 99, 245–253 (2011).

Zhang, J. P. et al. Efficacy and safety of individual second-generation vs. first-generation antipsychotics in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16, 1205–1218 (2013).

Emsley, R., Chiliza, B., Asmal, L. & Harvey, B. H. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 13, 50 (2013).

Miller, B. J., Bodenheimer, C. & Crittenden, K. Second-generation antipsychotic discontinuation in first episode psychosis: an updated review. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 9, 45–53 (2011).

Liu-Seifert, H., Adams, D. H. & Kinon, B. J. Discontinuation of treatment of schizophrenic patients is driven by poor symptom response: a pooled post-hoc analysis of four atypical antipsychotic drugs. BMC Med. 3, 21 (2005).

Huxley, P. et al. Schizophrenia outcomes in the 21st century: a systematic review. Brain Behav. 11, e02172 (2021).

Ascher-Svanum, H. et al. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 10, 2 (2010).

Pennington, M. & McCrone, P. The cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics 35, 921–936 (2017).

Waters, H. C., Ruetsch, C. & Tkacz, J. A claims-based algorithm to reduce relapse and cost in schizophrenia. Am. J. Manag. Care 25, e373–e378 (2019).

Lafeuille, M. H. et al. Patterns of relapse and associated cost burden in schizophrenia patients receiving atypical antipsychotics. J. Med. Econ. 16, 1290–1299 (2013).

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Measuring Price Change in the CPI: Medical Care. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/medical-care.htm. (2023).

Nicholl, D., Akhras, K. S., Diels, J. & Schadrack, J. Burden of schizophrenia in recently diagnosed patients: healthcare utilisation and cost perspective. Curr. Med Res. Opin. 26, 943–955 (2010).

Caseiro, O. et al. Predicting relapse after a first episode of non-affective psychosis: a three-year follow-up study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 46, 1099–1105 (2012).

Alvarez-Jimenez, M. et al. Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophr. Res 139, 116–128 (2012).

Schlief, M. et al. Ethnic differences in receipt of psychological interventions in Early Intervention in Psychosis services in England—a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 330, 115529 (2023).

Ziedan, E., Simon, K. I. & Wing, C. Effects of State COVID-19 Closure Policy on NON-COVID-19 Health Care Utilization. No. Working Paper 27621 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rachel Djaraher for providing project management support during the study on which this manuscript is based.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.C., P.X., J.L.S., L.N.P., T.G., and K.I. contributed to the conception and design of this study. C.L.C., Y.Y., and C.T. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data for this study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results. C.L.C. drafted the manuscript and all other authors provided critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.L.C., J.L.S., L.N.P., Y.Y., and C.T. were employees of Carelon Research at the time of the study, which received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. for the conduct of the study on which this manuscript is based. K.I. is an employee of Carelon Behavioral Health. C.L.C., J.L.S., and K.I. are Elevance Health shareholders. P.X. and T.G. are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Crowe, C.L., Xiang, P., Smith, J.L. et al. Real-world healthcare resource utilization, costs, and predictors of relapse among US patients with incident schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr 10, 86 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00509-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-024-00509-6

This article is cited by

-

Healthcare resource utilization burden associated with cognitive impairments identified through natural language processing among patients with schizophrenia in the United States

Schizophrenia (2025)

-

Dementia in older adults with schizophrenia: a 12-year analysis of prevalence, incidence, and treatment patterns in South Korea

Schizophrenia (2025)