Abstract

The hypoactivity of parvalbumin-containing interneurons (PV-interneurons) is a pathogenetic mechanism of schizophrenia according to the glutamatergic theory, and PV-interneurons are necessary for the generation of EEG/MEG gamma-frequencies (30–100 Hz). The present study aims to a literature synthesis on resting-state gamma-frequency changes in patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls, and to examine the relationship between these changes and severity of symptoms. A protocol was enregistered in PROSPERO and a systematic search was conducted in PubMed, PsycINFO and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, following PRISMA guidelines. An exploratory meta-analysis was realized. Out of 1391 records, 43 were included for a qualitative synthesis (N = 2133 [11–185], females 37.4%, age 33.9 ± 9.2). Results on power spectra were heterogeneous: in 12 studies gamma power was increased, involving the whole brain (N = 3), multiple regions (N = 6) or only frontal (N = 1), central (n = 1) and temporal (N = 1) areas; in 3 studies gamma power was reduced, involving multiple areas (N = 2) or the right temporal region (N = 1); one study revealed mixed results and 13 studies showed no differences. The meta-analysis on 4 studies (N = 211) showed non-significant differences between patients and controls and a large heterogeneity. The functional connectivity picture consists of sparse patterns of decreases and/or increases, widespread to multiple regions. Relationships emerged between gamma power and connectivity and severity of psychotic and cognitive symptoms. Theta-gamma coupling was increased in patients, with limited evidence for other changes in phase-amplitude coupling. Resting-state gamma-frequencies alterations in schizophrenia were inconsistent across studies; the heterogeneity of patients and methods could partially explain this outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex disorder consisting of several dimensions: positive symptoms (i.e., delusions and hallucinations), cognitive dysfunction (involving executive functions, memory, complex attention, language and social cognition), amotivation (including anhedonia, avolition and asociality) and diminished expression (including blunted affects and alogia)1. With a lifetime prevalence of 0.7–1%, the personal and societal burden of the disease is high2.

The glutamatergic theory of schizophrenia proposes the hypoactivity of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptors located on the gamma amino-butyric acid (GABA) parvalbumin-containing interneurons (PV-interneurons) as a core pathogenetic process. NMDA receptor hypofunction is sensed by PV-interneurons as a lack of pyramidal neurons activity, leading to a decrease in inhibitory tone3. The consequent excitation/inhibition imbalance leads to the hyperactivation of cortical pyramidal neurons4,5, which in turn also disrupts the activities of the dopaminergic mesolimbic and mesocortical systems6,7.

Electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) are neuroimaging techniques, with high temporal and spatial resolutions, which detect brain activity as an ensemble of electro-magnetic oscillations8. MEG allows for a better spatial resolution, because the magnetic signal is not distorted when passing through tissues with different conductivities, differently from EEG, and is also not prone to contaminations from muscle and cardiac artifacts. However, MEG cannot detect sources located radially to the sensor; thus, EEG and MEG can be considered as complementary for an accurate signal modeling9.

EEG/MEG gamma frequencies are brain oscillations in the 30–100 hz range9,10, originating from a complex interplay between pyramidal neurons and PV-interneurons, and are linked to the abovementioned glutamatergic theory of schizophrenia. In fact, according to the pyramidal-interneuron network gamma model (PING), gamma activity is generated through feedback inhibition on pyramidal neurons by PV-interneurons10,11 occurring in all regions10,11; the decay rate of this inhibition, approximately 25 ms, particularly contributes to the generation of 40 Hz oscillations12,13. The PING model has mostly replaced other models explaining the origin of gamma frequencies: the interneuron gamma model (ING), which posits a simultaneous firing of pyramidal cells and interneurons14, and the I-I model, based on a network of only two inhibitor interneurons connected11.

Gamma frequencies could represent an in vivo marker of the pathophysiological process underlying schizophrenia, and are easily accessible via EEG/MEG, even if it remains uncertain whether this reflects the primary pathophysiological mechanism or a downstream phenomenon. The relevance of gamma oscillations is corroborated by their physiological increase during adolescence, the typical age of onset of schizophrenia15, and by their abnormality already at illness onset16,17,18.

Gamma frequencies have been associated with sensation, perception, attention, memory, cognitive processing, consciousness and to synaptic plasticity, indicating their key role in brain functioning, and their possible implication in whole-brain diseases, such as schizophrenia3,16,19,20,21. Neuroimaging studies have suggested that treatment-resistant schizophrenia may rely more on a glutamatergic than on a dopaminergic dysfunction22.

Several studies have investigated the modification of gamma frequencies in patients with schizophrenia and their relationship with perceptual, affective and cognitive functioning. The resting state was the most common experimental setting, but a synthesis of evidence is missing; fewer studies evaluated task-related EEG, and they have already been summarized in important systematic reviews23,24,25.

Resting-state gamma frequencies and their relationship with the NMDA receptor functioning were analyzed in preclinical settings, as summarized by a recent review and perspective paper by Bianciardi and Uhlhaas. Their review indicates that in both animal models and healthy human subjects the pharmacological antagonism to the NMDA receptor results in an increase in resting-state gamma-band activity26, which was also related to psychotic symptoms in one study27. Moreover, a genetically determined reduction in the NMDA receptor activity, provoked an increased gamma power28,29,30,31 which was correlated with schizophrenia-like behaviors in animal models32,33,34, and with schizophrenia in humans35.

Following these lines of evidence, an increased resting-state gamma power in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy subjects would be expected. However, the review of Uhlhaas and Bianciardi revealed a more complex picture, with resting-state studies on patient with schizophrenia showing an increase or a decrease of power and functional connectivity across brain areas26. With the present paper, we aimed to update the work of Bianciardi and Uhlhaas on patients with schizophrenia, concerning the following three aspects: (i) inclusion of task related studies involving a resting-state phase; (ii) association of gamma-band alteration with symptoms’ severity; (iii) inclusion of studies on phase amplitude coupling and on functional connectivity measures not considered before.

In fact, the objective of the present systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis was to evaluate resting-state gamma-band related features in patients with schizophrenia, including differences from a comparator group (i.e., controls subjects, first-degree relatives or patients with another mental disorder), and their relationship with disease duration and severity, in several psychopathology domains.

Methods

Study design

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement was followed to design and conduct the systematic review. We performed a comprehensive literature search on EEG and MEG resting-state studies evaluating the gamma frequency range.

A review protocol was enregistered in PROSPERO (CRD 42024511291).

Article search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in three electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews since inception to 30th of September 2024 with no time limit and with the English language as the only selected filter. Moreover, a snowball search (i.e., a research method where an initial source, such as a relevant article or study, is used to find additional sources by examining its references or citing articles) was performed.

The following combination of search terms was used:

(“EEG” OR “electroencephalography” OR “electroencephalogram” OR “MEG” OR “magnetoencephalography”) AND “resting-state” AND (“schizophrenia” OR “first episode of psychosis”).

Selection process and criteria

First, any duplicate data from the combination of the three databases were excluded. The remaining articles were included in the systematic review only if they met the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Clinical trials, case-control and cohort studies;

-

2.

studies carried out in humans;

-

3.

studies published in the English language;

-

4.

studies conducted on patients affected by a disorder included in the DSM5 chapter “schizophrenia spectrum disorder”

-

5.

studies including subjects aged between 18 and 65 years

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

books chapters, comments, editorials, case reports, theses, proceedings, letters, short surveys, notes;

-

2.

studies focused on EEG changes induced by a treatment (e.g., medications, psychotherapy, or meditative practices);

-

3.

studies on sleep EEG;

-

4.

studies in which first-episode of psychosis patients did not transition to schizophrenia, or focused on individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis;

-

5.

studies irrelevant to the topic.

Two researchers (MDP and MS) independently screened for the eligibility all of the articles based on titles and abstracts and then proceeded to read the full text. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by the decision of a third reviewers.

Data extraction

MDP and MS recorded the following variables from each included article: author(s), year of publication, sample size, study design, sociodemographic and clinical features, assessment instruments for diagnosis, current and past pharmacological treatments, EEG methods and results, and statistical calculations.

The Assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews (AMSTAR 2 checklist)36 and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized case control studies37 were used to assess the quality and completeness of the data. Some of the NOS items were rule out and scoring was adapted, given that they were not applicable to the observational, cross-sectional studies reviewed here.

Data files and the R script for the meta-analysis can be found on the open science framework (OSF).

Summary measures

Statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio (RStudio team, Version: 2023.12.1 + 402) using R (R Core Team, 2024, version 4.3.3). We used the esc package to compute the effect sizes and the meta, metaphor and dmetar packages to conduct the meta-analyses.

Hedge’s g statistics were calculated for the standardized mean difference in bandwidth power between patients and control subjects; Hedge’s g was preferred to Cohen’s d in order to adjust for the small sample size bias38. Given that all effect sizes should be independent, we conducted 4 separate meta-analyses on the four main brain regions. We focused on the gamma1 band (i.e., 30–50 Hz), which has been more consistently reported across studies, while data were insufficient to conduct meta-analyses in the gamma2 and gamma3 subbands.

Synthesis of results

Given the high methodological heterogeneity among studies, a random effect model was used to combine and weight effect sizes across studies, using inverse variance methods. Heterogeneity was quantified using the percentage of variability in the effect size (i.e., the I2 statistic). A value ≥ 75% indicates high heterogeneity, a value of 50% indicates moderate heterogeneity, a value of 25% indicates a low heterogeneity39. Additionally, the between-study variance estimator τ2 using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method was calculated, and heterogeneity was moreover statistically assessed with the Cochran’s Q statistic. An influence analysis was carried out by visual inspection of Baujat40 and Viechtbauer-Cheung41 graphs.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

Figure 1 shows the selection process. The combined outcome of the three databases yielded a total of 1651 records, and no studies were added by hand search. Of the total studies, 260 were duplicates, leaving 1391 articles. After reading the titles and abstracts, 1331 articles were excluded because they were not relevant to the topic or did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of 60 articles were examined in detail. Six studies were excluded because they focused on EEG-bands other than gamma, 7 were excluded because the results did not report any positive or negative results on gamma-related features, 1 was excluded because the study was conducted on clinical high risk for psychosis patients only, and 1 was excluded because the study reported on children. Three studies using machine learning methods were excluded because they did not report the link between each feature under study and the variable of interest. No studies were excluded due to full-text unavailability or unavailability of English full-text.

A total number of 43 studies were ultimately identified as eligible for inclusion in the current review.

Tables 1–3 summarize the characteristics of the studies, including sociodemographic, clinical and EEG-related features.

Thirty-six studies used EEG, 7 used MEG; the total sample size was 2133 patients, ranging from 11 to 185 subjects per study and 37.6% of the participants were females. The mean age was 33.8 ± 9.2 years. Forty-one studies included a control group, for a total of 2040 participants (38% of females) with a mean age of 32.5 ± 7.8 years.

The AMSTAR checklist36 was used to foster the quality of this review and the meta-analysis. The included studies were described in detail (in the text or in the tables) concerning population, intervention, comparators (i.e., control group, different diagnostic groups, same patient on different time points), outcomes and research design. Methods were established prior to the review, and all studies suitable to investigate the variable of interest (i.e., gamma-band oscillation related to schizophrenia and its clinical features) were included. Study selection and data extraction were performed in duplicate. The exclusion of initially retrieved studies was explained. Funding and authoring were clearly reported.

The Newcastle Ottawa scale for case-control studies was used to rate the quality of each included study, as detailed in Supplementary Table S1. The quality was overall good, with an average score of 5.78 ± 1.4, in a reduced scale including only 6 out of 8 items.

Overview

Table 4 comprehensively reports the findings of each study in detail, and Supplementary Table S2 reports region-specific positive findings specific for each brain area. In the following sections, a synthesis of results is offered, delineating common patterns emerging across studies. Different aspects of gamma dynamics were collected in sections on power spectra, functional connectivity and phase-amplitude coupling. In each section, sub-headings are used to separate findings on the difference between patients and controls, and on the relationship of gamma frequencies with clinical features. In each sub-heading, we first report the number of studies observing positive, negative or null associations, then, the brain area, the lateralization, the gamma subband and the source localization method. In the relative section, functional connectivity measures are reported. Then, differences recording, preprocessing and analysis methods are reported in the text, and extensively described in Tables 5 and 6 (for studies on power spectra and functional connectivity, respectively). Secondary findings related to the topic of each section are reported at its end.

The meta-analysis on the difference in gamma1 spectral power between patients and controls follows the other results on power spectra.

Power spectra

Power spectra are the power distribution of EEG signal, decomposed in bands of frequency. The local electrical power is classically divided into 5 bands: delta (0–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz) and gamma (30–100 Hz)8; this latter is further divided in gamma1 (30–49 Hz), gamma2 (50–70 Hz), gamma3 (71–100 Hz) and supergamma ( >100 Hz) subbands.

While the generation mechanisms at the cellular level do not change across the gamma spectrum, low-gamma and high-gamma oscillations are considered to have different functional specialization, with lower frequencies linked to attention and sensory processing, and higher gamma associated with more complex cognitive functions, such as language, memory and consciousness11,42.

Patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls

Twelve studies indicated an increase in resting-state gamma power in schizophrenia43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54, 3 studies a reduction55,56,57, 1 study yielded mixed results (i.e., increase and decrease in spectral power in different brain regions), and 13 showed no difference in patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70.

Concerning studies having found an increase in gamma power in patients vs controls, the difference involved the whole brain (N = 3)43,44,45, multiple different regions (N = 6)46,47,49,50,53,54, or only the frontal (N = 1)48, central (N = 1)52 or temporal (N = 1)51 regions, in the left (N = 3)48,51,52, the right (N = 1)57 or both (N = 8)43,45,46,49,50,53,54,71 the hemispheres.

Significant differences between patients and controls were found in the gamma1 (N = 6)43,46,52, gamma1 and gamma2 (N = 3)45,53,54, or in the full gamma band (N = 2)51,71.

Concerning studies having found a decrease in gamma power in patients vs controls, the difference was localized in multiple regions (N = 2)55,56 or in the temporal lobe only (N = 1)57, involving the right hemisphere (N = 1)57 or both (N = 2)55,56, in the gamma1 (N = 1)57, gamma3 (N = 1)55 or the full gamma band (N = 1)56.

One study showed a pattern of increases and decreases of the whole-band gamma power, widespread to multiple regions in both hemispheres. This study also suggested that findings could depend on phase and duration of the disorder: in fact, compared to healthy controls, first episode of psychosis patients showed decreased prefrontal and increased occipital gamma1 activity, while chronic patients showed a decreased gamma1 in the frontal, temporal and sensorimotor areas71.

Studies detecting no differences between patients and controls in gamma spectral power analyzed specific regions (i.e., frontal, temporal, central, parietal and occipital) in both hemispheres, with few exceptions: one study focused on whole brain measures60, one study only considered regions belonging to the default mode network (i.e., posterior cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, lateral inferior parietal cortex, precuneus and anterior cingulate cortex)62, and two study focused on the auditory cortex64,65.

Gamma1 (N = 9)66,69,70, gamma1 and gamma2 (N = 2)67,72 or the whole band (N = 2)64,65 were analyzed.

Of the reviewed studies, only 5 used MEG53,56,62,67,71, while the others were conducted with an EEG, and several different methods were used for source localization: LORETA (low resolution brain electromagnetic tomography; N = 548,54,57,62,63), dynamic imaging of coherence sources (DICS; N = 259,71), BESA (brain electric source analysis; N = 2)64,65, equivalent current dipole (ECD) methods (N = 3)43,49,51, others (N = 4)53,56,60,67. These studies conducted the analysis at the source level, while the others at the sensor level, with 2 investigations using both54,63. Nine studies were conducted in eyes open conditions43,49,50,59,62,67,70,71, 1 study in both eyes open and closed53, the others (N = 22) with eyes closed. Further details on differences in recording, preprocessing and analysis are provided in the Table 5.

Another feature investigated was the relative amount of gamma power compared to the whole spectral power. In one investigation, patients’ activity was the greatest in gamma1, unlike in healthy controls, for whom activity was the greatest in alpha248.

In one study the distribution of gamma power across the brain was different between patients and healthy controls in gamma1 and gamma2 subbands73, but no differences emerged in this respect in another study, focused on gamma146.

In summary, the results were heterogeneous and do not allow to draw solid conclusions: while almost half of the studies detected no significant difference in gamma power between patients and controls, others suggested that schizophrenia is associated with altered gamma power. Twelve studies indicated an increased gamma activity in several regions and subbands, and only 3 observed a reduction.

Symptom severity

Several studies, already reported in the previous paragraph, have also assessed the relationship between symptom severity and resting state gamma-band power spectra, including positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and other dimensions, such as cognition and insight. Findings hereafter enumerated derive from single studies, without replication from one to the other.

Overall severity of disease positively correlated to gamma power either in the whole brain71, or in the prefrontal62 and the occipital cortex46; overall severity of disease also negatively correlated to gamma1 and gamma2 power in the temporal region44. Differences were lateralized to the left44,46 or to both62,71 the hemispheres. Subbands involved were gamma1 and gamma371, gamma1 and gamma244, or gamma1 only46,62. A negative correlation emerged between right temporal gamma3 power and social anhedonia55.

Gamma1 power significantly correlated with insight in left frontal and central regions52, but not with negative symptoms52.

Eight studies, whose methods are summarized in the previous paragraph and in Tables 1–3, revealed no significant relationship between the resting-state gamma-band and positive and negative psychotic symptoms severity48,52,53,61,62,67,72,74.

Concerning cognition, overall measures as the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia scale (BACS) and the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States negatively correlated with gamma power in posterior areas in patients with a first episode of schizophrenia, while frontal and central areas showed the opposite relationship. In chronic schizophrenia, BACS score was positively correlated with gamma-power, especially with gamma171.

Other studies found no association of gamma power with working memory49 and with verbal learning43.

In summary, research provides heterogeneous and non-replicated findings, with both positive and negative correlations observed in different brain regions, across several gamma subband. Such results cast doubts on the existence of a sound relationship between gamma-related spectral features and symptoms of schizophrenia.

Other results

Gamma-power negatively correlated with the duration of illness in the bilateral frontal regions in the gamma1 and gamma3 bands and in the right temporal region for gamma3 only45.

One investigation observed an increase in whole-brain gamma1 power in bipolar disorder compared to schizophrenia60.

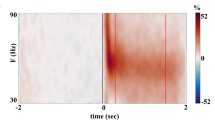

Gamma1 power spectra meta-analysis

All the records were initially included for meta-analyses on power spectra or functional connectivity differences between patients and controls. Only 19 studies provided exhaustive quantitative data in the text and in Supplementary Materials. Parameters for whom at least 3 studies had a comparable method (i.e., power spectra values in the whole brain or in single regions; specific measures of functional connectivity) were kept. Following this procedure only papers focused on power spectra remained (N = 7), but they were inhomogeneous for the frequency subband analyzed and for the use of absolute or relative power. In the end, the meta-analyses was conducted on studies providing measures of absolute power in the gamma1 band (N = 4), in specific brain regions (i.e., frontal, central, parietal, temporal). Individual study (k = 4) and aggregate effect sizes and measures of heterogeneity are presented in detail in Fig. 2.

Gamma1 power was not significantly increased in patients vs controls, in any region under study. Although all effect sizes were positive (i.e., higher gamma in patients vs controls), they were small and had broad confidence intervals. No outliers were detected.

An influence analysis with a leave-one-out method did not allow for a significant reduction of heterogeneity. The low number of studies included in the meta-analysis (n = 4) prevented subgroup analysis, meta regression, and the assessment of publication bias39.

Functional connectivity

EEG functional connectivity is the temporal coincidence of spatially distant neural activities that likely reflects the dynamic interregional communications in the brain, and it is calculated for all the frequency bands8.

Patients with schizophrenia vs healthy controls

Four studies observed an increase44,63,74,75, 6 studies a reduction51,57,62,73,76,77, 3 mixed results54,76,78 and 5 no difference between patients and controls53,60,63,66,79. Table 4 provides details on the localization and extension of the seed regions for the connectivity analysis, and on the regions with whom functional connectivity was reduced or increased.

An increased gamma-band connectivity was observed in the whole brain (N = 3)44,74,78 or involving multiple regions (N = 3)63,75,76. Differences were lateralized to the right in one case75, and involving both the hemispheres in the others.

A reduction in functional connectivity emerged in the whole-brain (N = 3)73,76,77, in multiple bilateral brain regions (N = 2)51,62, or in the right temporal and parietal regions (N = 1)57. Gamma subbands involved were gamma1 (N = 3)57,62,76, gamma1 and gamma2 (N = 2)73,77, or the full band (N = 1)51.

Three studies observed a complex pattern of decrease and increase in gamma connectivity across multiple bilateral brain regions, involving the gamma1 (N = 1)76, or gamma1 and gamma2 bands (N = 2)54,78. One study analyzing the functional connectivity at the whole brain level using multiple measures at the same time showed a complex pattern of increases or decreases in the various indexes considered54.

Four studies reported no significant differences in gamma band functional connectivity between patients and controls across all the brain regions, involving gamma1 (N = 3)60,79,80 or gamma1 and gamma2 bands (N = 1)53.

Differences in connectivity could also depend on the duration of disease, as suggested by one study reporting that patients with a more recent disease onset (< 5 years) had a diffuse increase in gamma1 and gamma2 connectivity compared to more chronic patients75. However, another study found no differences in the gamma1 connectivity between first-episode patients and chronic patients66.

Only 4 studies used MEG53,62,77,79, while the remaining 12 were conducted with EEG. For source localization, 7 studies used LORETA54,57,62,63,75,76,80, 2 minimum norm estimates (MNE)53,77 and two other methods51,79. While the studies enumerated conducted the analysis at the source level, the others were realized at the sensor level, with three exceptions using both54,63,80. Various methods were adopted for functional connectivity analysis, with 4 studies66,73,76,78 using the phase lag index (i.e., a bivariate measure of functional connectivity that and can be defined in terms of the Hilbert transformation of bandpass filtered signals, or in terms of the time-frequency representation of the broadband data81), 4 studies44,51,60,62 using measures of coherence (i.e., the consistency of the relative amplitude and phase between signals detected in coils or electrodes within a set frequency band82), 2 studies63,79 power envelope correlates (i.e., the relationship between the amplitude of the oscillatory brain activity and the temporal dynamics of that activity across different regions of the brain83), one study integrating several different analysis methods54 and 5 studies using other techniques53,57,74,75,80. In two cases the recording was with eyes open62,77, in other two with both eyes open and closed53,78, and with eyes closed only in the remaining studies (N = 14). Further details on differences in recording, preprocessing and analysis are provided in the Table 6.

In summary, the findings regarding gamma-band functional connectivity in schizophrenia are mixed and not conclusive, in some case partly overlapping from one study to the other, but without a consistent replication. Both increase and decrease in functional connectivity were described within and across brain areas, involving the three gamma subbands.

Symptom severity

Concerning positive psychotic symptoms, 3 studies produced disparate evidences.

Patients with more severe disorganization, delusions and hallucinations showed a lower gamma1 connectivity in a network including the left rolandic operculum, the left temporal regions and bilateral parietal, lateral frontal and orbitofrontal cortex63. In contrast, gamma1 and gamma2 whole brain connectivity was greater in patients having auditory verbal hallucinations than in controls84. Last, mixed results emerged in a study showing a positive correlation of PANSS total score with gamma1 and gamma2 local efficiency (i.e., he local information transmission capability of the network) in the frontal lobe and a negative correlation of the PANSS negative score with node degree (i.e., the number of edges connected to a node in a graph)78.

Attention had a significant positive association with gamma1 connectivity between the right cuneus and two regions: the transverse temporal gyrus and the superior temporal gyrus85.

No differences emerged in other investigations (N = 6) when considering the associations of gamma1 connectivity with severity of psychotic symptoms54,74, cognitive processing speed76, performance initiation57, and performance on arithmetic tasks61,76.

In summary, the literature provides only hints to a link between severity of schizophrenia symptoms and functional connectivity alterations, without replicated findings.

Phase amplitude coupling

A core mechanism of brain functioning is that low-frequency characteristics such as phase, amplitude and power, influence and synchronize those of higher frequency, an effect called phase-amplitude coupling86. This mechanism underlies the brain’s ability to integrate information across different frequency bands, allowing for coordinated processing among neural networks87.

Patients had higher values of theta-gamma coupling than controls in the whole brain88, in bilateral prefrontal areas89 or in the posterior cingulate cortex90. A study focused on the auditory cortex found no significant differences between patients and controls concerning theta-gamma coupling, that was however lateralized to the left in healthy subjects, but not in patients with schizophrenia65.

Moreover, theta-gamma coupling values in the posterior cingulate cortex were correlated with the results of the trail-making A, trail-making B, immediate recall and delayed recall tests90.

Delta-band phase synchronization with high gamma power91 was decreased in patients compared to healthy subjects in a wide region including bilateral frontocentral and temporoparietal electrodes.

Alpha-gamma coupling was greater in controls than in patients, in the whole brain89.

In summary, theta-gamma coupling was more often increased in patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls, at the whole brain or at the local level, with hints to a relationship with cognitive functioning. Other forms of phase amplitude coupling were rarely studied.

Discussion

Overall, our systematic review of 2133 patients and 2040 controls shows the heterogeneity of the existing literature on resting-state gamma frequency in patients with schizophrenia, concerning both methods and results. Although several studies have suggested an increased power and disrupted connectivity of resting-state gamma frequencies in schizophrenia, findings were not consistent across investigations, and not supported by our preliminary meta-analysis. The overall picture is inconsistent, with complex patterns of increased and decreased gamma power and connectivity. These patterns were either extended to the whole brain or located in specific regions. The reproducibility of the results from one study to the other was low, also partly due to the use of different methods for EEG/MEG analysis and brain area segmentation.

Power spectra

Twelve studies reported increased gamma-power in patients versus controls. Even with a significant heterogeneity concerning lateralization and region, the difference was widespread to most brain regions, more often involving multiple areas at the same time, and more consistently localized in the bilateral frontal and temporal cortex. However, three studies revealed reduced gamma-power in key regions such as prefrontal cortex, precuneus, cuneus, cingulate gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex and postcentral gyrus55,56,57. Finally, 13 studies did not find differences between patients and controls. These findings mostly concerned the gamma1 band, with a fewer reports on gamma2 and gamma3. We were only able to include 4 studies in an exploratory meta-analysis, that did not support the hypothesis of an increased gamma1 power in schizophrenia. Only minor differences between patients and controls emerged in frontal, temporal, parietal and central areas, not leading to statistical significance and with heterogeneity values of 98–99%.

One study71 suggested that gamma-band features could change according to the phase and duration of the disease. The severity of the disease correlated with gamma activity in the whole brain71, or in the frontal62, temporal44, and occipital46 regions, however 8 studies found no associations in this respect.

Concerning cognition, one study gave initial hints of a relationship between overall functioning and the gamma activity in frontal and occipital regions71, but 2 other investigations led to non-significant results.

The inconclusive findings on resting-state gamma frequencies in patients with schizophrenia are surprising, because in contrast with a large body of coherent preclinical evidences, indicating that an increase in gamma power (related to a glutamatergic dysfunction) leads to schizophrenia-like symptoms in both animal models and healthy volunteers. In fact, an increase in the excitatory input to parvalbumin interneurons in rodents via selective optogenetic stimulation leads to an increase in gamma activity, and the inhibition of parvalbumin interneurons leads to an immediate gamma suppression92,93. Moreover, the baseline gamma band in animal models of schizophrenia is elevated94. In rodents, pyramidal cell excitability and spontaneous gamma power are increased by NMDA-R antagonists95,96,97,98 and by a genetic loss-of-function of NMDA-R subunits28,29,30 or of functionally related genes such as ErbB231. Additionally, mutant mice expressing 5–10% of the obligatory NMDAR1 subunit exhibited electrophysiological and behavioral deficits consistent with schizophrenia32,33,34. A consistently replicated postmortem finding in the cortex of individuals with schizophrenia is the reduced expression of mRNA encoding the 67 kD isoform of GAD35. The use of NMDA-R antagonists (e.g., ketamine, PCP and MK-801) was associated with increased auditory-evoked gamma oscillation99, motor cortex excitability, psychotic symptoms and cognitive impairment in healthy volunteers27. Last, limbic encephalitis due the autoimmune antibodies binding to NMDA receptor can present with symptoms of schizophrenia, fostering the role of NMDA in the pathogenesis of this disorder100.

Functional connectivity and phase amplitude coupling

Gamma oscillatory activity is thought to be a fundamental mechanism that integrates neural networks within and across brain structures, facilitating coherent sensory elaboration and cognitive operations101. In particular, gamma frequencies are the key for feature binding (i.e., the ability to integrate different sensory features of a stimulus into a single coherent neural representation102).

In the studies included in this review, several different measures were used, leading to inconsistent findings. The few studies reporting significant effects suggest a complex global picture, with patterns of a decreased and/or increased functional connectivity across the whole brain, involving multiple different brain regions in each study. Disease severity correlated with frontal63 or whole brain84 gamma connectivity, but with contradictory results in another study78, and no significant associations in the others. Concerning cognition, only one study observed an association between attention and temporal lobe connectivity85.

Phase amplitude coupling was the focus of several investigations, with some studies suggesting increased theta-gamma coupling in patients with schizophrenia88,89,90, while in single studies delta-band phase synchronization with high-gamma was decreased91 and alpha-gamma coupling was increased89 in patients compared to healthy controls.

Evidence on the abnormal coordination of gamma oscillations in schizophrenia103,104 points toward a disconnection hypothesis, characterized by an aberrant synaptic modulation both between brain regions and between the layers of cortical columns105,106, leading to the disruption of networks underlying cognition and emotional processing107,108. Even if low-frequency oscillations impose fewer constraints on the precision of timing109 and are therefore probably more relevant for long-range synchronization, also gamma plays a role in this respect11,110.

Resting-state and task related gamma frequencies in schizophrenia

While our review of resting state gamma oscillation does not yield consistent effects, findings on task-related gramma responses seem to be more conclusive, as indicated by recent systematic reviews. Task-related responses in the gamma range were investigated especially in the auditory modality, with only one study dealing with the visual evoked response, which was reduced in schizophrenia111. The 40 Hz auditory steady state response (ASSR) in schizophrenia has deficient intertrial phase coherence and power, and is phase delayed compared to the norm; moreover, auditory steady-state response propagation across cortical sources was aberrant25. The consistent pattern for the ASSR indicates that circuits involved in the generation of high frequency oscillations are compromised; the inconclusive findings on resting state gamma suggest that the impairment involves mechanisms that are specific for task induced oscillations, not involving the resting-state.

Preclinical studies based on the administration of ketamine held the potential to better ascertain the link of the NMDA receptor activity with changes in gamma band oscillations. While in the resting state an increased gamma power after ketamine administration was observed in most of the studies26 results on task related recordings were mixed. In healthy controls, studies reported an increased gamma during an auditory paired click task112 and during a visual motor task113, but also a reduction during an auditory evoked gamma band response task114. During a visual grating task, ketamine induced an increase in gamma activity in healthy controls and a reduction in participants with schizophrenia115. These contradictory results indicate a complex dynamic between ketamine, NMDA receptor activity, and gamma band oscillations.

The translational potential of resting-state gamma frequencies

Resting-state gamma frequencies hold the potential for being a translational biomarker. On one hand, they could be useful for the diagnosis of schizophrenia and the assessment of its severity; however, heterogeneity of findings, as discussed, hinders such an application. On the other hand, gamma frequencies configure as a neurophysiology features to target with therapeutic interventions, such as medications and non-invasive brain stimulation.

Several approaches were developed to pharmacologically correct the activity of the NMDA receptor; the major challenge in this respect being that, while NMDA receptors are widespread to the whole brain, the pathophysiology of schizophrenia may be confined to specific brain regions and to discrete cell types, such as the PV-interneurons. Moreover, potentiating the glutamatergic synaptic activity may lead to excitotoxicity22. For these reasons, several compounds were developed to augment NMDA signaling indirectly, by enhancing glycinergic neurotransmission. Even if initial evidence of an efficacy on positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms emerged, larger clinical trials and meta-analyses revealed a modest overall effect22,116.

An opposite approach consists in antagonizing the activity of the NMDA receptor: riluzole showed a modest potential for treating negative symptoms117,118, while lamotrigine had a limited efficacy as an adjunctive medication for clozapine-resistant schizophrenia119. Enhancing the activity of the alpha-2 subunit containing GABA-A receptor leads to a reduced downstream glutamate release: a partial agonist at alpha 2 and alpha 3 GABA-A receptor subunits (MK-0777) improved cognition in patients with schizophrenia, but no effect on positive and negative symptoms was observed120.

Several studies showed an effect of antipsychotic medications on resting state gamma oscillations, and some of these related to response to treatment47,121,122, making it worth to further study their predictive power on response to medications.

The limited effectiveness of pharmacological interventions targeting glutamate prompts clinical trials on different therapeutic approaches, especially the ones based on non-invasive brain stimulation.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation proved to be effective in the treatment of positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, especially when applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal and the temporal cortex123,124.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation and direct current stimulation can entrain brain oscillations and modulate brain areas in a frequency-dependent and long-lasting manner125, and this effect seems to be mostly mediated by GABAergic interneurons activity11,126. TMS demonstrated to interact with gamma frequencies127,128,129, and a pilot study indicates that a modification of gamma frequencies by mean of TMS correlates with an improvement of disrupting behaviors in patients with autism130. However, a similar investigation focused on working memory in schizophrenia led to no significant results131. Further clinical trials are warranted to assess if an intervention targeting the resting-state gamma to make their pattern closer to the one of healthy controls can be an effective treatment of schizophrenia.

Limitations

Our systematic review and meta-analysis was limited by the methodological heterogeneity of included studies which does not allow to draw univocal and generalizable conclusions. Clinical and demographic variables and recording, preprocessing and analysis methods of the EEG/MEG data were considered as potential bias on results, possibly explaining the different and sometimes contradictory outcomes of different studies.

Intersubjective variability in sociodemographic and clinical features such age, sex, educational level, duration, and severity of disease was considerable and these parameters have been demonstrated to influence EEG in schizophrenia132. Some studies did not report relevant data about sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and patients were studied in different phases, concerning duration of disease and inpatient/outpatient status. Since EEG features are likely to change along the course of the disorder, this inhomogeneity represents a major limitation71. Patients were treated with different antipsychotic medications: the effect of each one on EEG trace can be specific and the responder vs non-responder to treatment status is associated with different EEG patterns133, leading to further heterogeneity. Many important pieces of information about medication were often missing, such as the dose, duration of treatment, concurrent and previous medications; when these informations were offered, large variability was observed among studies and subjects under study.

In the eyes-closed condition, there is a notable change in the dynamics of gamma band activity, which typically decreases, while alpha activity increases; this shift in frequency band activity can potentially drive a difference in results of studies conducted in the eyes open or eyes closed condition, which could be relevant given that the proportion of studies in the two conditions was not equal (eyes open: N = 11; eyes closed: N = 30; both: N = 3).

In some of the studies the duration of recording could be considered as suboptimal46,61,67.

The choice of source localization methods significantly influences EEG/MEG results due to varying precision and sensitivity to artifacts. Techniques such as Synthetic Aperture Magnetometry (SAM) and DICS excel in spatial resolution and network connectivity insights, respectively; however, both can be affected by noise. eLORETA and sLORETA provide stable localization at the cost of spatial specificity, while the Current Source Density (CSD) method effectively captures local activity but is sensitive to reference choices and heavily rely on an accurate head model. The ECD model may oversimplify complex activity patterns, and methods like MNE can struggle in underdetermined scenarios134.

Moreover, brain segmentation and techniques for attributing activity to sources differed by study, making it hard to exactly compare topographies, even when findings were in overlapping regions.

The intra- and intersubject variability of EEG/MEG recordings was another major concern: studies are generally characterized by a high variability within and even more between subjects, which might not always be indicative of any pathological status, making it difficult to generalize reports without applied normalization.

Functional connectivity techniques were different and non-comparable among different studies. Moreover, features as coherence, correlation and mutual information are highly subject to the volume conduction effect (i.e., at the level of each EEG channel, the effect of a mixture of active brain and nonbrain electrical sources whose activities are conducted to the scalp), which could produce results incorrectly indicating a functional connectivity or hemispheric asymmetries135. While we do not anticipate volume conduction to affect patients and controls differently, its impact could lead to more heterogeneous and less precise results, increasing uncertainty and reducing comparability between groups.

Gamma frequencies are subjected to contamination by muscular sources, especially in the gamma2 and gamma3 subbands8; for example, the myogenic activity from oculomotor and cranium foramen muscles generates biphasic sharp potential transients at the onset of a saccade, generating a broadband power increase in the 20–200 Hz range136,137.

This systematic review and meta-analysis present a significant risk of publication bias, which however was mitigated by the fact that several studies were not focused on resting-state gamma band, but also on other outcomes, which led to positive findings and, as a consequence, more likely to publication.

The small number of studies included in the meta-analysis precludes the generalizability of findings; only few were sufficiently homogeneous to conduct a meta-analysis, and potentially included data were not available for some studies. In addition, by including only studies published in peer-reviewed journals it is possible that some data available in the literature may have been excluded (i.e., gray literature, non-English language). According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews138, the low number of studies hindered second-level analysis useful to individuate bias and to moderate their effect, such as meta-regression and subgroup analysis. Also, publication bias was not assessed with a rigorous method (e.g., Egger’s linear regression139). In the end, this meta-analysis should be considered as purely exploratory.

When evaluating the relationship to positive and negative symptoms, studies included often used the PANSS positive and negative subscales, an approach that is now considered outdated; a more meaningful analysis would imply the use of the five factors model140.

Last, while EEG and MEG activity have been predominantly interpreted in the terms of the distribution of frequency along power spectra, as reflected in the present review, recent time have seen a renewed interest in the non-oscillatory, aperiodic component of the signal, as a unitary measure accounting for brain spectral power across frequencies141. The change in gamma band power in schizophrenia could manifest as a change in the aperiodic component, especially when accompanied by an inverse change in lower frequency bands. Only few studies to date evaluated the aperiodic component in schizophrenia, with only two studies in the resting state142, a number unsuitable for a systematic review. More importantly, the concept of aperiodic component involves gamma band only as a part of a broader phenomenon, and does not represent a gamma-band parameter in itself. For these reasons, we decided to not to include this aspect in the present paper.

Conclusions

Resting gamma-frequencies in schizophrenia were studied in a number of studies, leading to heterogeneous results. In our opinion, further investigations are needed. On one side they should be enlightened by novel theories on brain functioning and organization are needed for a unitary interpretation of the findings; on the other side, a standardization of methods and reporting would be necessary for a better interpretation of brain activity, and to determine its relevance for schizophrenia pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, the heterogeneity of findings could be “real”, depending on the existence of different subgroups of patients with schizophrenia, having a distinctive pathophysiology and, accordingly, different EEG and MEG features. Schizophrenia is a heterogenous disorder, and the glutamatergic dysfunction underlying the dysregulation of gamma frequencies in some individuals may not be relevant, or may play a role only as one of several pathological mechanisms22.

Finally, few studies have evaluated the relationship between gamma frequency and symptoms, including the positive, negative and cognitive dimensions; this sparseness of the literature further prompts future investigations.

Data availability

The data used in this systematic review and meta-analysis are sourced from the published studies revised. All relevant data supporting the findings of this study are included within the manuscript and its Supplementary Materials. Specific datasets analyzed during the study can be obtained from the respective articles referenced in the review. No original raw data were generated during this research, as it synthesized existing literature. Data files and the R script for the meta-analysis can be found on the open science framework (OSF).

Change history

12 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00611-3

References

McCutcheon, R. A., Reis Marques, T. & Howes, O. D. Schizophrenia—An overview. JAMA Psychiatry 77, 201 (2020).

Solmi, M. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02138-4 (2023).

McNally, J. M. & McCarley, R. W. Gamma band oscillations. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 29, 202–210 (2016).

McNally, J. M., McCarley, R. W. & Brown, R. E. Impaired GABAergic neurotransmission in Schizophrenia underlies impairments in cortical gamma band oscillations. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 15, 346 (2013).

Uhlhaas, P. J. & Singer, W. Neuronal dynamics and neuropsychiatric disorders: toward a translational paradigm for dysfunctional large-scale networks. Neuron 75, 963–980 (2012).

Stahl, S. M. Beyond the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia to three neural networks of psychosis: dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. CNS Spectr.23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852918001013 (2018).

Schwartz, T. L., Sachdeva, S. & Stahl, S. M. Glutamate neurocircuitry: theoretical underpinnings in schizophrenia. Front. Pharmacol.,3, https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2012.00195 (2012).

Michel, C.M., Koenig, T., Brandeis, D., Gianotti, L. R. R. & Wackermann, J. (eds) Electrical Neuroimaging. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511596889 (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

Uhlhaas, P. J. et al. Magnetoencephalography as a tool in psychiatric research: current status and perspective. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2, 235–244 (2017).

Tamás, G., Buhl, E. H., Lörincz, A. & Somogyi, P. Proximally targeted GABAergic synapses and gap junctions synchronize cortical interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 366–371 (2000).

Buzsáki, G. & Wang, X. J. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 35, 203–225 (2012).

Fernandez-Ruiz, A., Sirota, A., Lopes-dos-Santos, V. & Dupret, D. Over and above frequency: gamma oscillations as units of neural circuit operations. Neuron 111, 936–953 (2023).

Dienel, S. J. & Lewis, D. A. Alterations in cortical interneurons and cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neurobiol. Dis. 131, 104208 (2019).

Gonzalez-Burgos, G., Cho, R. Y. & Lewis, D. A. Alterations in cortical network oscillations and parvalbumin neurons in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 1031–1040 (2015).

Uhlhaas, P. J. The adolescent brain: implications for the understanding, pathophysiology, and treatment of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 480–483 (2011).

Reilly, T. J. et al. Gamma band oscillations in the early phase of psychosis: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 90, 381–399 (2018).

Kerins, S. et al. Identifying electroencephalography biomarkers in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis in an international multi-site study. Front. Psychiatry. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.828376 (2022).

Perrottelli, A., Giordano, G. M., Brando, F., Giuliani, L. & Mucci, A. EEG-based measures in at-risk mental state and early stages of schizophrenia: a systematic review. Front. Psychiatry. 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.653642 (2021).

Bosman, C. A., Lansink, C. S. & Pennartz, C. M. A. Functions of gamma-band synchronization in cognition: from single circuits to functional diversity across cortical and subcortical systems. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1982–1999 (2014).

Uhlhaas, P. J. Dysconnectivity, large-scale networks and neuronal dynamics in schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 23, 283–290 (2013).

Wespatat, V., Tennigkeit, F. & Singer, W. Phase sensitivity of synaptic modifications in oscillating cells of rat visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 24, 9067–9075 (2004).

McCutcheon, R. A., Krystal, J. H. & Howes, O. D. Dopamine and glutamate in schizophrenia: biology, symptoms and treatment. World Psychiatry 19, 15–33 (2020).

Schielke, A. & Krekelberg B. Steady state visual evoked potentials in schizophrenia: a review. Front. Neurosci. 16, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.988077 (2022).

Kim, H. K., Blumberger, D. M. & Daskalakis, Z. J. Neurophysiological biomarkers in schizophrenia—P50, mismatch negativity, and TMS-EMG and TMS-EEG. Front. Psychiatry. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00795 (2020).

Grent-’t-Jong, T., Brickwedde, M., Metzner, C. & Uhlhaas, P. J. 40-Hz auditory steady-state responses in schizophrenia: toward a mechanistic biomarker for circuit dysfunctions and early detection and diagnosis. Biol. Psychiatry 94, 550–560 (2023).

Bianciardi, B. & Uhlhaas, P. J. Do NMDA-R antagonists re-create patterns of spontaneous gamma-band activity in schizophrenia? A systematic review and perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 124, 308–323 (2021).

Orliac, F. et al. Links among resting-state default-mode network, salience network, and symptomatology in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 148, 74–80 (2013).

Belforte, J. E. et al. Postnatal NMDA receptor ablation in corticolimbic interneurons confers schizophrenia-like phenotypes. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 76–83 (2010).

Billingslea, E. N. et al. Parvalbumin cell ablation of NMDA-R1 causes increased resting network excitability with associated social and self-care deficits. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 1603–1613 (2014).

Carlén, M. et al. A critical role for NMDA receptors in parvalbumin interneurons for gamma rhythm induction and behavior. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 537–548 (2012).

del Pino, I. et al. Erbb4 deletion from fast-spiking interneurons causes schizophrenia-like phenotypes. Neuron 79, 1152–1168 (2013).

Dzirasa, K. et al. Hyperdopaminergia and NMDA receptor hypofunction disrupt neural phase signaling. J. Neurosci. 29, 8215–8224 (2009).

Halene, T. B. et al. Assessment of NMDA receptor NR1 subunit hypofunction in mice as a model for schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav. 8, 661–675 (2009).

Mohn, A. R., Gainetdinov, R. R., Caron, M. G. & Koller, B. H. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression display behaviors related to schizophrenia. Cell 98, 427–436 (1999).

Guidotti, A. et al. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 1061 (2000).

Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008 (2017).

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 (2010).

Hedges, L. V. Distribution theory for glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 6, 107–128 (1981).

Higgins, J. P. & Green, S, (eds) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184 (Wiley, 2008).

Baujat, B., Mahé, C., Pignon, J. & Hill, C. A graphical method for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: application to a meta-analysis of 65 trials. Stat. Med. 21, 2641–2652 (2002).

Viechtbauer, W. & Cheung, M. W. L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1, 112–125 (2010).

Uhlhaas, P. J. & Singer, W. The development of neural synchrony and large-scale cortical networks during adolescence: relevance for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and neurodevelopmental hypothesis. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 514–523 (2011).

Tanaka-Koshiyama, K. et al. Abnormal spontaneous gamma power is associated with verbal learning and memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00832 (2020).

Tikka, S. K. et al. Evaluation of spontaneous dense array gamma oscillatory activity and minor physical anomalies as a composite neurodevelopmental endophenotype in schizophrenia. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 40, 43–51 (2015).

Yadav, S., Haque Nizamie, S., Das, B., Das, J. & Tikka, S. K. Resting state quantitative electroencephalogram gamma power spectra in patients with first episode psychosis: An observational study. Asian J. Psychiatr. 57, 102550 (2021).

Baradits, M. et al. Alterations in resting-state gamma activity in patients with schizophrenia: a high-density EEG study. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 269, 429–437 (2019).

Mitra, S., Nizamie, S. H., Goyal, N. & Tikka, S. K. Evaluation of resting state gamma power as a response marker in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 69, 630–639 (2015).

Ramyead, A. et al. Neural oscillations in antipsychotic-naïve patients with a first psychotic episode. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 17, 296–307 (2016).

Koshiyama, D. et al. Abnormal phase discontinuity of alpha- and theta-frequency oscillations in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 231, 73–81 (2021).

Freche, D. et al. Phase-amplitude markers of synchrony and noise: a resting-state and TMS-EEG study of schizophrenia. Cereb. Cortex Commun. 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/texcom/tgaa013 (2020).

Soni, S., Muthukrishnan, S. P., Sood, M., Kaur, S. & Sharma, R. Altered parahippocampal gyrus activation and its connectivity with resting-state network areas in schizophrenia: An EEG study. Schizophr. Res. 222, 411–422 (2020).

Arikan, M. K., Metin, B., Metin, S. Z., Tülay, E. E. & Tarhan, N. High frequencies in QEEG are related to the level of insight in patients with schizophrenia. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 49, 316–320 (2018).

Alamian, G. et al. Patient, interrupted: MEG oscillation dynamics reveal temporal dysconnectivity in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 28, 102485 (2020).

Gordillo, D. et al. The EEG multiverse of schizophrenia. Cereb. Cortex. 33, 3816–3826 (2023).

Umesh, S., Nizamie, S. H., Goyal, N., Tikka, S. & Bose, S. Social anhedonia and gamma band abnormalities as a composite/multivariate endophenotype for schizophrenia: a dense array EEG study. Early Inter. Psychiatry 12, 362–371 (2018).

Rutter, L. et al. Magnetoencephalographic gamma power reduction in patients with schizophrenia during resting condition. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 3254–3264 (2009).

Krukow, P., Jonak, K., Grochowski, C., Plechawska-Wójcik, M. & Karakuła-Juchnowicz, H. Resting-state hyperconnectivity within the default mode network impedes the ability to initiate cognitive performance in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 102, 109959 (2020).

Venables, N. C., Bernat, E. M. & Sponheim, S. R. Genetic and disorder-specific aspects of resting state EEG abnormalities in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 826–839 (2009).

Hanslmayr, S., Staudigl, T., Fellner, M. C. Oscillatory power decreases and long-term memory: the information via desynchronization hypothesis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00074 (2012).

Kam, J. W. Y., Bolbecker, A. R., O’Donnell, B. F., Hetrick, W. P. & Brenner, C. A. Resting state EEG power and coherence abnormalities in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 47, 1893–1901 (2013).

Garakh, Z. et al. EEG correlates of a mental arithmetic task in patients with first episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126, 2090–2098 (2015).

Kim, J. S. et al. Power spectral aspects of the default mode network in schizophrenia: an MEG study. BMC Neurosci. 15, 104 (2014).

Andreou, C. et al. Increased resting-state gamma-band connectivity in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 930–939 (2015).

Hirano, Y. et al. Spontaneous gamma activity in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 813 (2015).

Hirano, S. et al. Phase-amplitude coupling of the electroencephalogram in the auditory cortex in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging3, 69–76 (2018).

Jonak, K., Krukow, P., Jonak, K. E., Grochowski, C. & Karakuła-Juchnowicz, H. Quantitative and qualitative comparison of EEG-based neural network organization in two schizophrenia groups differing in the duration of illness and disease burden: graph analysis with application of the minimum spanning tree. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 50, 231–241 (2019).

Zeev-Wolf, M. et al. MEG resting-state oscillations and their relationship to clinical symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuroimage Clin. 20, 753–761 (2018).

Vignapiano, A. et al. Reward anticipation and trait anhedonia: An electrophysiological investigation in subjects with schizophrenia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 127, 2149–2160 (2016).

Kim, S. et al. Altered cortical functional networks in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a resting-state electroencephalographic study. Front Psychiatry. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00661 (2020).

Jacob, M. S. et al. The scanner as the stimulus: deficient gamma-BOLD coupling in schizophrenia at rest. Schizophr. Bull. 49, 1364–1374 (2023).

Grent-’t-Jong, T. et al. Resting-state gamma-band power alterations in schizophrenia reveal E/I-balance abnormalities across illness-stages. Elife. 7, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.37799 (2018).

Vignapiano, A. et al. Disorganization and cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: New insights from electrophysiological findings. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 145, 99–108 (2019).

Takahashi, T. et al. Abnormal functional connectivity of high-frequency rhythms in drug-naïve schizophrenia. Clin. Neurophysiol. 129, 222–231 (2018).

Kikuchi, M. et al. Frontal areas contribute to reduced global coordination of resting-state gamma activities in drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 130, 187–194 (2011).

Di Lorenzo, G. et al. Altered resting-state EEG source functional connectivity in schizophrenia: the effect of illness duration. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00234 (2015).

Krukow, P. et al. Disturbed functional connectivity within the left prefrontal cortex and sensorimotor areas predicts impaired cognitive speed in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging275, 28–35 (2018).

Tagawa, M. et al. Disrupted local beta band networks in schizophrenia revealed through graph analysis: a magnetoencephalography study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 76, 309–320 (2022).

Chang, Y. et al. Temporal hyper-connectivity and frontal hypo-connectivity within gamma band in schizophrenia: a resting state EEG study. Schizophr. Res. 264, 220–230 (2024).

Lottman, K. K. et al. Examining resting-state functional connectivity in first-episode schizophrenia with 7 T fMRI and MEG. Neuroimage Clin. 24, 101959 (2019).

Andreou, C. et al. Resting-state theta-band connectivity and verbal memory in schizophrenia and in the high-risk state. Schizophr. Res. 161, 299–307 (2015).

Stam, C. J., Nolte, G. & Daffertshofer, A. Phase lag index: assessment of functional connectivity from multi channel EEG and MEG with diminished bias from common sources. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 1178–1193 (2007).

Shaw, J. C., O’Connor, K. P. & Ongley, C. The EEG as a measure of cerebral functional organization. Br. J. Psychiatry 130, 260–264 (1977).

O’Neill, G. C., Barratt, E. L., Hunt, B. A. E., Tewarie, P. K. & Brookes, M. J. Measuring electrophysiological connectivity by power envelope correlation: a technical review on MEG methods. Phys. Med. Biol. 60, R271–R295 (2015).

Sun, Q. et al. Hyper-activated brain resting-state network and mismatch negativity deficit in schizophrenia with auditory verbal hallucination revealed by an event-related potential evidence. Front. Psychiatry. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00765 (2020).

Yeh, T. C. et al. Resting-state EEG connectivity at high-frequency bands and attentional performance dysfunction in stabilized schizophrenia patients. Medicina59, 737 (2023).

Munia, T. T. K. & Aviyente, S. Time-frequency based phase-amplitude coupling measure for neuronal oscillations. Sci. Rep. 9, 12441 (2019).

Hülsemann, M. J., Naumann, E. & Rasch, B. Quantification of phase-amplitude coupling in neuronal oscillations: comparison of phase-locking value, mean vector length, modulation index, and generalized-linear-modeling-cross-frequency-coupling. Front. Neurosci. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00573 (2019).

Won, G. H. et al. Theta-phase gamma-amplitude coupling as a neurophysiological marker in neuroleptic-naïve schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 260, 406–411 (2018).

Ibáñez-Molina, A., Crespo Cobo, Y., Soriano Peña, M. F., Iglesias-Parro, S. & Ruiz de Miras, J. Mutual information of multiple rhythms in schizophrenia. Brain Struct. Funct. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-023-02744-6 (2023).

Lee, T. H. et al. Relationship between resting-state theta phase-gamma amplitude coupling and neurocognitive functioning in patients with first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 216, 154–160 (2020).

Koshiyama, D., Miyakoshi, M., Tanaka-Koshiyama, K., Sprock, J. & Light, G. A. High-power gamma-related delta phase alteration in schizophrenia patients at rest. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 76, 179–186 (2022).

Cardin, J. A. et al. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature 459, 663–667 (2009).

Sohal, V. S., Zhang, F., Yizhar, O. & Deisseroth, K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature 459, 698–702 (2009).

White, R. S. & Siegel, S. J. Cellular and circuit models of increased resting-state network gamma activity in schizophrenia. Neuroscience 321, 66–76 (2016).

Ehrlichman, R. S. et al. N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor antagonist–induced frequency oscillations in mice recreate pattern of electrophysiological deficits in schizophrenia. Neuroscience 158, 705–712 (2009).

Lazarewicz, M. T. et al. Ketamine modulates theta and gamma oscillations. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 1452–1464 (2010).

Kocsis, B. Differential role of NR2A and NR2B subunits in N-Methyl-D-Aspartate receptor antagonist-induced aberrant cortical gamma oscillations. Biol. Psychiatry 71, 987–995 (2012).

Wood, J., Kim, Y. & Moghaddam, B. Disruption of prefrontal cortex large scale neuronal activity by different classes of psychotomimetic drugs. J. Neurosci. 32, 3022–3031 (2012).

Di Lazzaro, V. et al. Ketamine increases human motor cortex excitability to transcranial magnetic stimulation. J. Physiol. 547, 485–496 (2003).

Al-Diwani, A. et al. The psychopathology of NMDAR-antibody encephalitis in adults: a systematic review and phenotypic analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 235–246 (2019).

Gandal, M. J., Edgar, J. C., Klook, K. & Siegel, S. J. Gamma synchrony: towards a translational biomarker for the treatment-resistant symptoms of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology 62, 1504–1518 (2012).

Gray, C. M., König, P., Engel, A. K. & Singer, W. Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature 338, 334–337 (1989).

Spencer, K. M. et al. Abnormal neural synchrony in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 23, 7407–7411 (2003).

Uhlhaas, P. J. et al. Dysfunctional long-range coordination of neural activity during gestalt perception in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 26, 8168–8175 (2006).

Friston, K, Brown, H. R, Siemerkus, J & Stephan, K. E The dysconnection hypothesis. Schizophr. Res. 176, 83–94 (2016).

Stephan, K. E., Friston, K. J. & Frith, C. D. Dysconnection in schizophrenia: from abnormal synaptic plasticity to failures of self-monitoring. Schizophr. Bull. 35, 509–527 (2009).

Varela, F., Lachaux, J. P., Rodriguez, E. & Martinerie, J. The brainweb: Phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 229–239 (2001).

Fries, P., Reynolds, J. H., Rorie, A. E. & Desimone, R. Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science291, 1560–1563 (2001).

Kopell, N., Ermentrout, G. B., Whittington, M. A. & Traub, R. D. Gamma rhythms and beta rhythms have different synchronization properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA97, 1867–1872 (2000).

Guo, W. et al. Hyperactivity of the default-mode network in first-episode, drug-naive schizophrenia at rest revealed by family-based case–control and traditional case–control designs. Medicine 96, e6223 (2017).

Krishnan, G. P. et al. Steady state and induced auditory gamma deficits in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 47, 1711–1719 (2009).

Hong, L. E. et al. Gamma and delta neural oscillations and association with clinical symptoms under subanesthetic ketamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 632–640 (2010).

Shaw, A. D. et al. Ketamine amplifies induced gamma frequency oscillations in the human cerebral cortex. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25, 1136–1146 (2015).

Curic, S. et al. Reduced auditory evoked gamma-band response and schizophrenia-like clinical symptoms under subanesthetic ketamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 1239–1246 (2019).

Grent-‘t-Jong, T. et al. Acute ketamine dysregulates task-related gamma-band oscillations in thalamo-cortical circuits in schizophrenia. Brain 141, 2511–2526 (2018).

Stone, J. M. Glutamatergic antipsychotic drugs: a new dawn in the treatment of schizophrenia. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 1, 5–18 (2011).

Farokhnia, M, et al. A double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized trial of riluzole as an adjunct to risperidone for treatment of negative symptoms in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology 231, 533–542 (2014).

Pillinger, T, et al. Altered glutamatergic response and functional connectivity in treatment resistant schizophrenia: the effect of riluzole and therapeutic implications. Psychopharmacology 236, 1985–1997 (2019).

Tiihonen, J., Wahlbeck, K. & Kiviniemi, V. The efficacy of lamotrigine in clozapine-resistant schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 109, 10–14 (2009).

Lewis, D. A. et al. Subunit-selective modulation of GABA type A receptor neurotransmission and cognition in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 1585–1593 (2008).

Arıkan, M. K., Günver, G., İlhan, R., Öksüz, Ö. & Metin, B. Gamma oscillations predict treatment response to aripiprazole in bipolar disorder. J. Affect Disord. 294, 159–162 (2021).

Itil, T. M., Shapiro, D., Schneider, S. J. & Francis, I. B. Computerized EEG as a predictor of drug response in treatment resistant schizophrenics. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 169, 629–637 (1981).

Lorentzen, R., Nguyen, T. D., McGirr, A., Hieronymus, F. & Østergaard, S. D. The efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia 8, 35 (2022).

Cheng, P. W. C. et al. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on clinical symptoms in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J. Psychiatr. 53, 102392 (2020).

Helfrich, R. F. et al. Entrainment of brain oscillations by transcranial alternating current stimulation. Curr. Biol. 24, 333–339 (2014).

Benali, A. et al. Theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation alters cortical inhibition. J. Neurosci. 31, 1193–1203 (2011).

Santarnecchi, E. et al. High-gamma oscillations in the motor cortex during visuo-motor coordination: a tACS interferential study. Brain Res. Bull. 131, 47–54 (2017).

Moisa, M., Polania, R., Grueschow, M. & Ruff, C. C. Brain network mechanisms underlying motor enhancement by transcranial entrainment of gamma oscillations. J. Neurosci. 36, 12053–12065 (2016).

Maiella, M. et al. Simultaneous transcranial electrical and magnetic stimulation boost gamma oscillations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Sci. Rep. 12, 19391 (2022).

Casanova, M. F. et al. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy on evoked and induced gamma oscillations in children with autism spectrum disorder. Brain Sci. 10, 423 (2020).

Barr, M. S. et al. The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on gamma oscillatory activity in Schizophrenia. PLoS ONE6, e22627 (2011).

John, E. R. et al. Quantitative electrophysiological characteristics and subtyping of schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 36, 801–826 (1994).

De Pieri, M., Rochas, V., Sabe, M., Michel, C. & Kaiser, S. Pharmaco-EEG of antipsychotic treatment response: a systematic review. Schizophrenia 9, 85 (2023).

Asadzadeh, S., Yousefi Rezaii, T., Beheshti, S., Delpak, A. & Meshgini, S. A systematic review of EEG source localization techniques and their applications on diagnosis of brain abnormalities. J. Neurosci. Methods 339, 108740 (2020).

Brunner, C., Billinger, M., Seeber, M., Mullen, T. R. & Makeig S. Volume conduction influences scalp-based connectivity estimates. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fncom.2016.00121 (2016).

Jerbi, K. et al. Saccade related gamma-band activity in intracerebral EEG: dissociating neural from ocular muscle activity. Brain Topogr. 22, 18–23 (2009).

Kovach, C. K. et al. Manifestation of ocular-muscle EMG contamination in human intracranial recordings. Neuroimage 54, 213–233 (2011).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4. (Cochrane, 2023).

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Wallwork, R. S., Fortgang, R., Hashimoto, R., Weinberger, D. R. & Dickinson, D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 137, 246–250 (2012).

Pani, S. M., Saba, L. & Fraschini, M. Clinical applications of EEG power spectra aperiodic component analysis: a mini-review. Clin. Neurophysiol. 143, 1–13 (2022).

Earl, R. J., Ford, T. C., Lum, J. A. G., Enticott, P. G. & Hill, A. T. Exploring aperiodic activity in first episode schizophrenia spectrum psychosis: a resting-state EEG analysis. Brain Res. 1840, 149052 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the project: M.D.P. Interpretation and analysis of data: M.D.P., V.R., M.S., S.K. Original draft: M.D.P., V.R., M.S., M.K. Critical analysis and review of the draft: S.K., M.K., G.P., J.B. All the authors have approved the final article draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions