Abstract

Patients with schizophrenia (SCZ) face multiple health challenges due to the complication of chronic diseases and psychiatric disorders. Among these, cardiovascular comorbidities are the leading cause of their life expectancy being 15–20 years shorter than that of the general population. Identifying comorbidity patterns and uncovering differences in immune and metabolic function are crucial steps toward improving prevention and management strategies. A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted using electronic medical records of inpatients discharged between 2015 and 2024 from a municipal psychiatric hospital in China. The study included patients diagnosed with Schizophrenia, Schizotypal, and Delusional Disorders (SSDs) (ICD-10: F20–F29). Comorbidity patterns were identified through latent class analysis (LCA) based on the 20 most common comorbid conditions among SSD patients. To investigate differences in peripheral blood metabolic and immune function, linear regression or generalized linear models were applied to 44 laboratory test indicators collected during the acute episode. The Benjamini-Hochberg method was used for p-value correction, and the false discovery rate (FDR) was calculated, with statistical significance set at FDR < 0.05. Among 3,697 inpatients with SSDs, four distinct comorbidity clusters were identified: SSDs only (Class 1), High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders (Class 2, n = 39), Low-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders (Class 3, n = 573), and Sleep Disorders (Class 4, n = 205). Compared to Class 1, Class 2 exhibited significantly elevated levels of apolipoprotein A (ApoA; β = 90.62), apolipoprotein B (ApoB; β = 0.181), mean platelet volume (MPV; β = 0.994), red cell distribution width–coefficient of variation (RDW-CV; β = 1.182), antistreptolysin O (ASO; β = 276.80), and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC; β = 0.306), along with reduced apolipoprotein AI (ApoAI; β = –0.173) and hematocrit (HCT; β = –35.13). Class 3 showed moderate increases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C; β = 0.113), MPV (β = 0.267), white blood cell count (WBC; β = 0.476), and absolute neutrophil count (ANC; β = 0.272), with decreased HCT (β = –9.81). Class 4 was characterized by elevated aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI; β = 81.07), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR; β = 0.465), and systemic inflammation response index (SIRI; β = 0.346), indicating a heightened inflammatory state. The comorbidity patterns of patients with SCZ can be distinctly classified. During the acute episode, those with comorbid metabolic disorders exhibit a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases and immune system abnormalities, while patients with comorbid sleep disorders present a pronounced systemic inflammatory state and immune dysfunction. This study provides a basis for the chronic disease management and anti-inflammatory treatment, while also offering objective biomarker insights for transdiagnostic research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder are classified as serious mental illnesses (SMI), with affected individuals experiencing a life expectancy 15–20 years shorter than that of the general population. Among SMI patients, those with SCZ exhibit the highest mortality rates, with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) identified as the leading cause of death1,2,3. Patients with SMI face substantial health challenges due to the high prevalence of chronic diseases and psychiatric comorbidities, underscoring the significance of comorbidity as a critical and emerging concept in understanding disease burden. The growing body of research on comorbidities in SMI highlights their pivotal role in reducing disease burden and promoting the integration of physical and mental healthcare4.

Increasing evidence suggests that early interventions targeting physiological health parameters are essential for mitigating morbidity and premature mortality. However, compared to other SMI subtypes, the burden of comorbid conditions in patients with SCZ may be underestimated5,6. Meta-analyses indicate that the prevalence of hypertension in SCZ patients is approximately 39%, and nearly one-third of individuals meet the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome7,8.

SCZ is a chronic disorder in which the side effects of antipsychotic medications contribute to adverse health outcomes and may increase mortality risk during the progression of comorbid conditions9. However, research indicates that disease-related risk factors and abnormalities emerge early in the course of the illness, including biological factors such as chronic inflammation, patient-related factors such as excessive smoking, and healthcare system-related factors such as stigma and discrimination. These factors collectively contribute to an unfavorable cardiovascular risk profile in SCZ patients2,10. Moreover, a significant bidirectional relationship has been observed between psychiatric disorders and physical illnesses11. Epilepsy, nutritional or metabolic disorders, and various physical conditions have been associated with an increased risk of SCZ12. Emerging evidence suggests that inflammatory responses may play a fundamental role in the pathophysiology of SCZ13 and are also implicated in SCZ-related cardiovascular health complications14. In clinical practice, biomarkers related to metabolic dysfunction, cardiovascular damage, and inflammation serve as potential diagnostic and therapeutic indicators15. Additionally, these biomarkers may provide prognostic insights for SCZ patients. For example, cohort studies have demonstrated that higher basophil counts are associated with an increased risk of relapse over a three-year follow-up period16, while an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) has been linked to greater symptom improvement following 12 weeks of antipsychotic treatment17. In summary, alterations in blood parameters among SCZ patients are closely associated with immune and metabolic dysfunction, as well as the comorbidity of multiple system. These findings highlight the necessity of adopting a multidisciplinary, transdiagnostic, and personalized care model for SCZ patients2,18,19,20,21.

Estimating the prevalence of comorbidities, identifying comorbidity patterns, and uncovering their underlying differences are critical first steps in understanding how comorbid conditions impact the physical health, quality of life, and mortality of SCZ subgroups. These efforts serve as essential prerequisites for advancing future research on the prevention and management of comorbidities in SCZ. Previous studies have rarely conducted systematic investigations into the overall comorbidity landscape of SCZ patients. Most existing research has primarily focused on differences in metabolic and inflammatory markers between SCZ patients and healthy controls. Therefore, this study aims to identify distinct comorbidity patterns among SCZ patients and further explore differences in immune and metabolic functions within these subgroups.

Methods

Study population

We employed a retrospective cross-sectional design, utilizing clinical electronic medical records from a tertiary public psychiatric hospital in China. This research was conducted as part of a multicenter scientific collaboration led by Beijing Huilongguan Hospital. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University Huilongguan School of Clinical Medicine [(2023) Research No. 104], and all data have been anonymized to ensure patient confidentiality.

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria. First, their admission and discharge occurred between January 1, 2015, and August 31, 2024. Second, during hospitalization, at least two attending psychiatrists or higher-ranked specialists confirmed the diagnosis of Schizophrenia, Schizotypal, and Delusional Disorders (SSDs) based on the 10th Revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), with corresponding diagnostic codes F20–F29. Third, complete demographic and clinical information, including age and sex, was available. Fourth, for patients with multiple hospitalizations within the study period, only data from the first hospitalization were included. Lastly, peripheral blood test results collected at the time of hospital admission, reflecting pre-treatment biomarker levels, were required for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following conditions. First, they had a concurrent diagnosis of any of the following: organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders (F00–F09), mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10–F19), infectious and parasitic diseases (A00–B99), neoplasms (C00–D48), diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism (D50–D89), acute respiratory infections (J00–J22), congenital malformations of the nervous system (Q00–Q07), injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes (S00–T98), or other unspecified conditions (U00–Z99). Second, patients who received antibiotics or immunosuppressive agents, such as corticosteroids or antineoplastic drugs. Third, individuals with incomplete clinical data. Lastly, patients who died during hospitalization.

As illustrated in the sample selection flowchart (Fig. 1), we implemented a rigorous data curation and quality control process. First, patient medical records were collected based on the inclusion criteria, and a unique identifier was assigned to each patient using their ID code. Patients with missing identity information were excluded. Next, cases that did not meet the diagnostic and medication criteria were systematically removed based on the exclusion criteria. Finally, patients with missing laboratory test data were excluded. For each variable, outliers were identified according to the data distribution and validated through a retrospective review of the medical records system. Medication use during hospitalization was classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification System, allowing for the identification of antibiotic use, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs for each patient.

Identification of the top 20 most common comorbidities

To systematically investigate the comorbidity patterns of somatic and psychiatric disorders in patients with SSDs and to minimize potential misclassification of specific diagnoses, we categorized diagnoses based on the Block level within the five-tier structure of the ICD-10 classification system (i.e., Chapter, Block, Category, Subcategory, and Detailed Code). Diagnoses were aggregated and ranked according to their frequency. Based on this ranking, the top 20 Block-level ICD-10 diagnoses were identified as the most common comorbidities in SSD patients and were included in the comorbidity pattern analysis (Details in Table S1).

Potentially associated variables

Demographic, clinical treatments, and laboratory indicators related to systemic immunity and metabolism were collected. Demographic variables included age, sex, education level, marital status, work status, ethnicity, payment method, and number of hospital admissions.

To systematically explore immune and metabolic differences across different comorbidity clusters in SSD patients, a total of 36 peripheral blood biomarkers were collected. These included C-reactive protein (CRP), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), free fatty acids (FFA), triglycerides (TG), apolipoprotein AI (ApoAI), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), apolipoprotein A (Apo A), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), platelet-larger cell ratio (P-LCR), mean platelet volume (MPV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), red blood cell (RBC), red cell distribution width coefficient of variation (RDW-CV), red cell distribution width-standard deviation (RDW-SD), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), hematocrit (HCT), platelet count, platelet distribution width (PDW), plateletcrit (PCT), hemoglobin (Hb), neutrophil percentage, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), monocyte percentage, absolute monocyte count (AMC), basophil percentage, absolute basophil count (ABC), antistreptolysin O (ASO), lymphocyte percentage, absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), white blood cell (WBC) count, rheumatoid factor (RF), and serum amyloid A (SAA).

In addition, eight composite immune-inflammatory indices were calculated to further characterize systemic immune dysregulation. These included the monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (MHR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), systemic immune-inflammation index (SII), systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), aggregate index of systemic inflammation (AISI), and derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (dNLR). These indices were derived as follows: MHR = monocytes / HDL-C; MLR = monocytes / lymphocytes; PLR = platelets / lymphocytes; NLR = neutrophils / lymphocytes; SII = (platelets × neutrophils) / lymphocytes; SIRI = (neutrophils × monocytes) / lymphocytes; AISI = (neutrophils × monocytes × platelets) / lymphocytes; and dNLR = neutrophils / (WBC - neutrophils).

Statistical analysis

Latent class analysis (LCA) is a statistical approach that explains the associations among observed categorical variables by identifying latent categorical variables. This method estimates the relationships between observed variables through latent classes, summarizing and interpreting their probabilistic distributions using a smaller number of mutually exclusive latent categories, making it a form of dimensionality reduction technique22. In this study, 20 comorbidity variables were analyzed using LCA. Models with 1 to 10 latent classes were fitted, and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was used as the primary criterion for selecting the optimal classification model. In addition, other model fit indices and clinical interpretability were considered to determine the best categorization. Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize patient characteristics and comorbidity profiles. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations. For non-normally distributed variables, the 25th percentile (P25), median (P50), and 75th percentile (P75) were reported. Prevalence estimates of comorbid conditions refer to diagnoses documented during the index hospitalization.

Based on the identified SSD comorbidity patterns, group comparisons were conducted. Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, while continuous variables were tested for normality to determine whether analysis of variance (ANOVA) or non-parametric rank-sum tests were appropriate. To explore differences in systemic immune and metabolic profiles across comorbidity patterns, linear regression models or generalized linear models were applied, adjusting for age, gender, and admission count to estimate the corresponding regression coefficients and p-values for each variable. To control for false-positive findings, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons via false discovery rate (FDR) correction. A significance threshold of FDR < 5% was applied to determine statistically significant effects. Results with a raw p-value < 0.05 that did not remain significant after FDR adjustment were considered indicative of potential associations.

All data processing and statistical analyses were conducted using R software (Version 4.4.1). Categorical variables were described using frequency (n) and percentage (%), while continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on their distribution. All statistical tests were two-sided, with a significance level set at 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 show the distribution of disease diagnoses and demographic characteristics of the 3,697 hospitalized SSD patients. Among them, 2,880 patients (77.90%) were diagnosed solely with SSDs, with no recorded comorbid conditions, while 817 patients (22.10%) had at least one additional diagnosis. Based on the ICD-10 classification, aside from mental and behavioral disorders, the most frequently co-diagnosed condition was endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (1.60%), followed by diseases of the digestive system (0.73%). Notably, 10.87% of SSD patients had comorbid endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases, the highest proportion among comorbid conditions, followed by diseases of the nervous system (8.41%). Regarding demographic characteristics, 52.50% of the patients were female. The majority were married (62.10%), and most were blue-collar workers (83.42%). The predominant age group was 40–59 years (47.42%). In terms of ethnicity, 81.17% were Han Chinese, while 52.99% had a secondary school education. Most patients (73.33%) used urban and rural resident medical insurance. Additionally, 50.09% of the patients were first-time hospitalizations at this institution.

Comorbidity patterns in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders

As shown in Table S1, among the comorbid conditions in SSD patients, metabolic disorders had the highest diagnostic frequency (1.11%), with the largest proportion of patients (8.22%) presenting with this comorbidity, followed by episodic and paroxysmal disorders (7.33%) and symptoms and signs involving the circulatory and respiratory systems (4.08%). Based on the LCA results for the top 20 comorbid diagnoses, combined with clinical interpretability (Fig. 2, Tables S2, S3), a three-class model was identified as the optimal classification. Class 1 was characterized by the highest probability of metabolic disorders (conditional probability = 0.88) and disorders of the thyroid gland (conditional probability = 0.61). Additionally, cerebrovascular diseases, other degenerative diseases of the nervous system, other disorders of the kidney and ureter, hypertensive diseases, and other forms of heart disease all had conditional probabilities exceeding 0.25. This cluster was labeled “High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders”, accounting for 4.77% of the total sample. Class 2 was primarily characterized by metabolic disorders (conditional probability = 0.42), with lower probabilities of comorbid conditions from other systems. This group was named “Low-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders”, representing 70.13% of the sample. Class 3 was distinguished by episodic and paroxysmal disorders, with a conditional probability of 1.00, indicating that all patients in this category had this comorbidity. According to Table S2, the primary diagnosis within this category was sleep disorders, leading to its designation as the “Sleep Disorders”, comprising 25.09% of the total sample.

E00-E07: Disorders of thyroid gland; E10-E14: Diabetes mellitus; E70-E90: Metabolic disorders; F40-F48: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders; G20-G26: Extrapyramidal and movement disorders; G30-G32: Other degenerative diseases of the nervous system; G40-G47: Episodic and paroxysmal disorders; I10-I15: Hypertensive diseases; I30-I52: Other forms of heart disease; I60-I69: Cerebrovascular diseases; J30-J39: Other diseases of upper respiratory tract; K20-K31: Diseases of oesophagus, stomach and duodenum; K55-K64: Other diseases of intestines; K70-K77: Diseases of liver; K80-K87: Disorders of gallbladder, biliary tract and pancreas; N20-N23: Urolithiasis; N25-N29: Other disorders of kidney and ureter; R00-R09: Symptoms and signs involving the circulatory and respiratory systems; R10-R19: Symptoms and signs involving the digestive system and abdomen; R90-R94: Abnormal findings on diagnostic imaging and in function studies, without diagnosis.

Associations between patient characteristics and comorbidity clusters in schizophrenia spectrum disorders

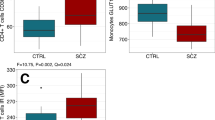

As shown in Table 2, significant differences were observed in the demographic characteristics among the four comorbidity clusters in SSD patients, including sex, age group, work status, marital status, ethnic group, and education level. In particular, the proportion of female patients was slightly higher in the High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders Cluster (53.85%) and the Sleep Disorders Cluster (58.54%), while male patients were predominant in the other groups. Across all categories, SSD patients were predominantly married, engaged in blue-collar occupations, aged 40–59 years, of Han ethnicity, and covered under urban and rural resident insurance, with most being first-time hospitalizations. Length of hospital stay did not differ significantly among the groups (P = 0.092). Among the peripheral blood test results, blood group, LDL-C, Apo B, and Apo A, which are metabolism-related markers, showed significant differences between groups (P < 0.05). Additionally, immune function-related indicators, including WBC count, neutrophil percentage, MLR, NLR, SII, SIRI, AISI, and dNLR, also showed significant intergroup differences (P < 0.05).

Immune-metabolic differences across comorbidity clusters in acute schizophrenia spectrum inpatients

As shown in Tables 3 and S4, differences in immune and metabolic markers among the four SSD comorbidity patterns were analyzed after adjusting for age, gender, and admission count, using the SSD Only group as the reference. In the High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders Cluster, several markers were significantly elevated, including ApoB (β = 0.181, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), ApoA (β = 90.62, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), MPV (β = 0.994, P = 0.002, FDR = 0.01), RDW-CV (β = 1.182, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), PCT (β = 0.035, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), Basophil percentage (β = 0.294, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), ABC (β = 0.03, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), Eosinophil percentage (β = 0.983, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), AEC (β = 0.075, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), ASO (β = 276.795, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), and ALC (β = 0.306, P = 0.004, FDR = 0.01). Conversely, ApoAI (β = -0.173, P = 0.002, FDR = 0.01), Hct (β = -35.131, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), PDW (β = -3.966, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), and Neutrophil percentage (β = -4.315, P = 0.012, FDR = 0.03) were significantly lower.

In the Low-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders Cluster, significantly lower levels were observed for Hct (β = -9.807, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001) and PDW (β = -1.344, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001). In contrast, multiple immune and metabolic markers were significantly higher, including LDL-C (β = 0.113, P = 0.009, FDR = 0.03), ApoA (β = 35.407, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), MPV (β = 0.267, P = 0.008, FDR = 0.02), RDW-CV (β = 0.294, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), PCT (β = 0.012, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), ANC (β = 0.272, P = 0.007, FDR = 0.02), AMC (β = 0.025, P = 0.006, FDR = 0.02), Basophil percentage (β = 0.068, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), ABC (β = 0.009, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), Eosinophil percentage (β = 0.182, P = 0.009, FDR = 0.03), AEC (β = 0.015, P = 0.004, FDR = 0.01), ALC (β = 0.155, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), WBC (β = 0.476, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), and PLR (β = -11.294, P = 0.006, FDR = 0.02).

In the Sleep Disorders Cluster, immune-inflammatory markers were notably elevated, including AISI (β = 81.065, P = 0.006, FDR = 0.02), NLR (β = 0.465, P = 0.016, FDR = 0.04), SIRI (β = 0.346, P = 0.003, FDR = 0.01), Neutrophil % (β = 2.721, P = 0.001, FDR < 0.001), ANC (β = 0.606, P < 0.001, FDR < 0.001), and WBC (β = 0.568, P = 0.001, FDR < 0.001). Conversely, Eosinophil percentage (β = -0.298, P = 0.005, FDR = 0.01) and Lymphocyte percentage (β = -2.277, P = 0.002, FDR = 0.01) were significantly lower.

Discussion

This study analyzed nearly ten years of electronic medical record data from a tertiary psychiatric hospital in a municipal city in China, systematically identifying comorbidity patterns in SCZ patients. Four distinct categories were classified: SSDs Only, High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders, Low-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders, and Sleep Disorders. After adjusting for age, gender, and admission count, significant differences were observed across comorbidity subtypes in peripheral blood markers related to endocrine, metabolic, and inflammatory levels, as well as immune and cardiovascular functions in acutely symptomatic SCZ patients.

This study found that the majority of patients (77.90%) were diagnosed with SSDs only, while nearly one-quarter (22.10%) had comorbid conditions, primarily endocrine, metabolic, and CVDs. This finding aligns with a meta-analysis, which reported that 25% of patients with SMI had somatic comorbidities, and 14% had psychiatric comorbidities6. Another meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) in SMI patients at 32.6%8. However, the comorbidity rate observed in this study was notably lower than rates reported in other datasets, including medicaid claims in New York (74.9%)23, UK primary care data (60.70%)24, and hospital records from 186 hospitals in Beijing, China (86.9%)25. In contrast, a study in Xinjin District, Chengdu, China, found that 37.8% of SMI patients had at least one physical illness, reflecting variability across regions26. The relatively lower comorbidity rate observed in this study may stem from data limitations, as the records were derived from a single psychiatric hospital without access to comprehensive claims or insurance databases. Previous research has indicated that certain physical health conditions in patients with schizophrenia may be underdiagnosed compared to those with other severe mental illnesses5. Moreover, the study site—located in Yunnan Province, a border region in China—faces economic constraints and limited healthcare resources, which may further contribute to diagnostic gaps. These findings highlight the need to consider regional equity in the allocation of healthcare resources. Additionally, the lack of multidisciplinary care in psychiatric hospitals underscores the importance of strengthening general medical training and promoting integrated care models within mental health institutions.

This study found that metabolic multisystem disorders were the predominant comorbidities in SCZ patients, aligning with previous research23. MetS, hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic diseases are highly prevalent in SCZ patients, largely due to the systemic dysregulation associated with SCZ, including inflammation and oxidative stress27,28,29. Increasing evidence suggests a shared etiology between SMI and CVDs, involving biological, genetic, and behavioral mechanisms30. Prior studies indicate that SCZ patients face cardiometabolic risks as early as the first episode of psychosis and the initial stages of antipsychotic treatment31,32. Antipsychotic exposure can rapidly increase lipid metabolism risks, with some drugs like clozapine, while highly effective, being linked to myocarditis and cardiomyopathy33. Additionally, the risk of comorbidities varies by antipsychotic type8. Genetic studies suggest that shared loci between SCZ and CVD risk factors contribute to differences in CVD comorbidity patterns among SCZ subgroups34. Mendelian randomization studies also support an increased heart failure risk in individuals with SCZ susceptibility35. However, other research suggests that SCZ-MetS comorbidity is primarily influenced by environmental factors, such as antipsychotic medication, lifestyle changes, and physical inactivity, rather than genetic predisposition36. This study further found that most patients fell into the relatively low-risk metabolic multisystem disorders category, while a smaller proportion had high-risk metabolic profiles, highlighting the importance of endocrine, metabolic, and cardiovascular screening for early detection and intervention in SCZ patients. The small size of the High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders cluster (n = 39) may be partly due to the composition of the study sample, in which 50% of patients were first-time admissions to the hospital rather than predominantly chronic cases. In addition, it may reflect both true rarity and underdiagnosis in settings with limited multidisciplinary care. Patients in this group were predominantly older (46% ≥60 years) and mostly covered by the urban and rural resident health insurance (97%), suggesting delayed access to comprehensive services. These findings highlight structural barriers to early detection and underscore the need for improved screening and integrated care in schizophrenia37. Additionally, one-fourth of patients were classified in the Sleep Disorders Cluster, consistent with reports that sleep disturbances are a common clinical feature in SCZ38 and a key physiological mechanism of psychiatric disorders39. Previous studies estimate that 80% of SCZ patients experience at least one sleep disorder, with insomnia and nightmare being the most common40. This suggests that sleep disorders remain significantly underdiagnosed, underscoring the need for targeted interventions41.

Notably, female patients had higher proportions of High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders and Sleep Disorders. Research has consistently shown that SMI in females is associated with an elevated risk of CVD compared to the general female population42. A large-scale epidemiological cohort study in Japan also reported a stronger association between schizophrenia and subsequent CVD events in females than in males43. These findings align with our results and suggest that sex-specific vulnerability, potentially driven by hormonal, behavioral, and psychosocial factors, may contribute to the clustering of comorbidities. In addition, this study identified significant differences across comorbidity clusters in age group, marital status, employment, ethnicity, education level, and insurance type, consistent with prior findings43,44. The predominance of patients in the 40–59 age group, with blue-collar occupations and coverage under the urban and rural resident health insurance scheme, suggests delayed healthcare access and long-term accumulation of physical health risks. These demographic patterns may reflect broader structural barriers to early detection and integrated care in schizophrenia. Together, the findings underscore the need for broader data sources and prospective studies to clarify the epidemiology and sex-specific trajectories of comorbidities in schizophrenia.

After adjusting for age, gender, and admission count, the analysis revealed significant differences in lipid metabolism and cardiovascular function among SCZ patients with comorbid Metabolic Multisystem Disorders during the acute episode. Notably, the greater the comorbidity risk, the larger the variation in laboratory test results, aligning with the clinical characteristics of these metabolic and cardiovascular conditions. With increasing metabolic multisystem disorders risk, ApoA showed a substantial increase, suggesting a higher risk of liver metabolism abnormalities in these patients, indicating its potential as a predictive biomarker for comorbidities. Importantly, only in the High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders Cluster, ApoA1 significantly decreased, while ApoB significantly increased. ApoA1 is the primary apolipoprotein of HDL-C and plays a key role in reverse cholesterol transport, phospholipid efflux, and lipoprotein metabolism. ApoB represents the total concentration of atherogenic lipoprotein particles in circulation and provides a more accurate measure of atherosclerotic burden than LDL-C45. Previous studies have reported a significant association between ApoA1, ApoB levels, and cognitive function in SCZ, regulated by ApoE rs429358 polymorphism46,47. Lower ApoA1 levels and activity may contribute to immune inflammation and oxidative stress pathways in SCZ48, particularly affecting mRNA expression in peripheral blood leukocytes during acute episodes49. One study found that first-episode SCZ patients experienced significant increases in body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol, and ApoB levels after treatment50. Peripheral blood cells have been proposed as an accessible model to study intracellular signaling changes in SCZ, offering potential for stratifying subgroups of patients at higher risk for metabolic and cardiovascular side effects following antipsychotic treatment51. These findings suggest that identifying these biomarkers can help refine clinical risk prediction and preventive strategies for MetS in SCZ patients52. Further research is needed to develop risk stratification approaches and implement differentiated cardiovascular care strategies for SMI patients2.

Growing evidence supports the critical role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of SCZ53,54,55. This study found that as metabolic multisystem disorders risk increased, several peripheral blood markers significantly elevated in SCZ patients, including MPV, PCT, RDW-CV, basophil percentage, ABC, eosinophil percentage, AEC, ASO, lymphocyte percentage, ALC, and WBC. These findings align with previous studies56,57,58,59,60,61, as these hematological parameters are widely used inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, reflecting systemic inflammation and potentially increased risks for thrombosis, MetS, or CVDs. Although a healthy control group was not included, comparisons across comorbidity subgroups enabled the identification of relative biomarker shifts within the patient population. The marked elevations and large β-values observed in the High-Risk Metabolic Multisystem Disorders cluster likely reflect a distinct physiological state characterized by cumulative multisystem burden and heightened inflammatory activity. These biomarkers may represent indicators of disease complexity and comorbidity severity, offering potential clinical value for risk stratification and targeted intervention.

Additionally, evidence suggests immune dysregulation in SCZ patients62. However, within the Metabolic Multisystem Disorders Cluster, Hct, PDW, neutrophil percentage, and PLR were significantly lower, while AISI, NLR, and MLR showed no significant differences. These results contrast with previous studies that reported positive associations between inflammatory markers and cardiovascular risk63,64, which may be due to undetected metabolic and cardiovascular conditions in the SSDs-only group in this study. Additionally, prior research suggests a nonlinear relationship between systemic inflammatory markers and CVD risk65. Some studies also report that non-treatment-resistant schizophrenia (NTRS) patients exhibit higher PLR levels than treatment-resistant cases66, while SCZ patients generally have lower platelet and PLR levels compared to healthy controls56. These findings highlight the complexity of SCZ comorbidities, emphasizing the need for further investigation and supporting the potential value of blood parameters in assessing metabolic risk in SCZ patients. Notably, in the Sleep Disorders Cluster, patients showed significantly higher AISI, NLR, SIRI, neutrophil percentage, ANC, and WBC levels, while eosinophil percentage and lymphocyte percentage were significantly lower, compared to the SSDs-only group. These findings suggest impaired immune function and oxidative stress in SCZ patients with comorbid sleep disorders, consistent with previous studies67,68,69, which also report gender differences, with female patients being more affected70. A close relationship exists between sleep deprivation and activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis71. Research indicates that sleep deprivation increases HPA axis activity, leading to elevated cortisol levels, which in turn suppresses immune cell function, including lymphocytes and eosinophils, potentially weakening immune defense72. Moreover, HPA axis overactivation is a key contributor to insomnia, creating a vicious cycle that may contribute to long-term health problems such as metabolic dysfunction and CVD73. These findings suggest that improving sleep quality may help regulate inflammation in SCZ patients, aligning with previous research19,67.

This study also has several limitations. First, the data were collected from a single-center hospital in Yunnan Province, a border region of China, with a limited sample size and potential diagnostic bias. Furthermore, the exclusion of patients with substance use disorders may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader psychiatric populations. Future multi-center studies across China are needed to systematically investigate comorbidity patterns in SCZ patients and validate the observed metabolic and immune differences. Second, due to missing data, important laboratory indicators such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and other cytokines were excluded. Future research should explore these key inflammatory biomarkers to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the inflammatory mechanisms involved. Third, this study only examined metabolic and inflammatory differences in peripheral blood across different comorbidity patterns, establishing associations rather than causation. Prospective studies are needed to determine whether these biomarkers can predict comorbidity progression and mediate differences in SCZ comorbidity patterns. Fourth, this study focused on acutely symptomatic patients, lacking data on disease duration and medication use, which are critical factors influencing comorbidities, metabolic changes, and immune function. Antipsychotic treatment has a significant impact on metabolic and immune function, and future studies should incorporate these factors, particularly focusing on first-episode patients9,74. Fifth, the study population was limited to a single racial group in China, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Genetic and physiological differences across racial groups may influence biomarker profiles and treatment responses, warranting caution in applying these results to other populations.

Conclusions

Based on electronic medical record data from hospitalized patients, this study comprehensively identified four distinct comorbidity clusters in SCZ patients and systematically explored immune and metabolic differences in peripheral blood during the acute phase. Patients with comorbid metabolic disorders exhibited a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and immune system dysfunction, with greater metabolic risk correlating with larger biomarker fluctuations. In contrast, patients with comorbid sleep disorders demonstrated significant systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction. These findings provide insights for personalized treatment strategies in SSD patients, highlighting the clinical relevance of comorbidity patterns in disease management. Additionally, this study offers objective biomarker evidence for transdiagnostic research in SCZ.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request due to ethical limitations.

References

Nielsen, R. E., Banner, J. & Jensen, S. E. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 136–145 (2021).

Polcwiartek, C. et al. Severe mental illness: cardiovascular risk assessment and management. Eur. Heart J. 45, 987–997 (2024).

Lambert, A. M. et al. Temporal trends in associations between severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 19, e1003960 (2022).

Halstead, S., Siskind, D. & Warren, N. Making meaning of multimorbidity and severe mental illness: a viewpoint. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 58, 12–20 (2024).

Launders, N., Kirsh, L., Osborn, D. P. J. & Hayes, J. F. The temporal relationship between severe mental illness diagnosis and chronic physical comorbidity: a UK primary care cohort study of disease burden over 10 years. Lancet Psychiatry 9, 725–735 (2022).

Halstead, S. et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in people with and without severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 11, 431–442 (2024).

Gardner-Sood, P. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in people with established psychotic illnesses: baseline data from the IMPaCT randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 45, 2619–2629 (2015).

Vancampfort, D. et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 14, 339–347 (2015).

Burschinski, A. et al. Metabolic side effects in persons with schizophrenia during mid- to long-term treatment with antipsychotics: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 22, 116–128 (2023).

Sudarshan, Y. & Cheung, B. M. Y. Hypertension and psychosis. Postgrad. Med. J. 99, 411–415 (2023).

Dragioti, E. et al. Impact of mental disorders on clinical outcomes of physical diseases: an umbrella review assessing population attributable fraction and generalized impact fraction. World Psychiatry 22, 86–104 (2023).

Sorensen, H. J., Nielsen, P. R., Benros, M. E., Pedersen, C. B. & Mortensen, P. B. Somatic diseases and conditions before the first diagnosis of schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based cohort study in more than 900 000 individuals. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 513–521 (2015).

Hwang, Y. et al. Gene expression profiling by mRNA sequencing reveals increased expression of immune/inflammation-related genes in the hippocampus of individuals with schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 3, e321–e321 (2013).

Hung, W. C. et al. FABP3, FABP4, and heart rate variability among patients with chronic schizophrenia. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1165621 (2023).

Kinoshita, M. et al. Effect of clozapine on DNA methylation in peripheral leukocytes from patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 632 (2017).

Llorca-Bofí, V. et al. Inflammatory blood cells and ratios at remission for psychosis relapse prediction: a three-year follow-up of a cohort of first episodes of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 267, 24–31 (2024).

Lu, X. et al. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in first-episode medication-naïve patients with schizophrenia: a 12-week longitudinal follow-up study. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 131, 110959 (2024).

Skou, S. T. et al. Multimorbidity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 8, 48 (2022).

Brinn, A. & Stone, J. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio across psychiatric diagnoses: a cross-sectional study using electronic health records. BMJ Open 10, e036859 (2020).

Moody, G. & Miller, B. J. Total and differential white blood cell counts and hemodynamic parameters in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 260, 307–312 (2018).

Pernow, J. & Yang, J. Red blood cells: a new target to prevent cardiovascular disease?. Eur. Heart J. 45, 4249–4251 (2024).

Collins, L. M. & Lanza, S. T. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences (Wiley, 2009).

Goldman, M. L. et al. Medical comorbid diagnoses among adult psychiatric inpatients. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 66, 16–23 (2020).

Launders, N., Hayes, J. F., Price, G. & Osborn, D. P. Clustering of physical health multimorbidity in people with severe mental illness: an accumulated prevalence analysis of United Kingdom primary care data. PLoS Med.19, e1003976 (2022).

Han, X. et al. Comorbidity combinations in schizophrenia inpatients and their associations with service utilization: a medical record-based analysis using association rule mining. Asian J. Psychiatry 67, 102927 (2022).

Wei, D.-N. et al. Physical illness comorbidity and its influencing factors among persons with severe mental illness in Rural China. Asian J. Psychiatry 71, 103075 (2022).

Hagi, K. et al. Association between cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive impairment in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 510 (2021).

Pillinger, T., D’Ambrosio, E., McCutcheon, R. & Howes, O. D. Is psychosis a multisystem disorder? A meta-review of central nervous system, immune, cardiometabolic, and endocrine alterations in first-episode psychosis and perspective on potential models. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 776–794 (2019).

Pillinger, T. et al. Cardiac structure and function in patients with schizophrenia taking antipsychotic drugs: an MRI study. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 163 (2019).

Goldfarb, M. et al. Severe mental illness and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 918–933 (2022).

Zhai, D. et al. Cardiometabolic risk in first-episode schizophrenia (FES) patients with the earliest stages of both illness and antipsychotic treatment. Schizophr. Res. 179, 41–49 (2017).

Correll, C. U. et al. Cardiometabolic risk in patients with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: baseline results from the RAISE-ETP study. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 1350 (2014).

Kritharides, L., Chow, V. & Lambert, T. J. Cardiovascular disease in patients with schizophrenia. Med. J. Aust. 206, 91–95 (2017).

Rødevand, L. et al. Characterizing the shared genetic underpinnings of schizophrenia and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am. J. Psychiatry 180, 815–826 (2023).

Veeneman, R. R. et al. Exploring the relationship between schizophrenia and cardiovascular disease: a genetic correlation and multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Schizophr. Bull. 48, 463–473 (2022).

Aoki, R. et al. Shared genetic components between metabolic syndrome and schizophrenia: genetic correlation using multipopulation data sets. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 76, 361–366 (2022).

Solmi, M. et al. Disparities in screening and treatment of cardiovascular diseases in patients with mental disorders across the world: systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 observational studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 178, 793–803 (2021).

Kaskie, R., Graziano, B. & Ferrarelli, F. Schizophrenia and sleep disorders: links, risks, and management challenges. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 9, 227–239 (2017).

Baglioni, C. et al. Sleep and mental disorders: a meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol. Bull. 142, 969–990 (2016).

Reeve, S., Sheaves, B. & Freeman, D. Sleep disorders in early psychosis: incidence, severity, and association with clinical symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 45, 287–295 (2019).

Chung, K.-F., Poon, Y. P. Y.-P., Ng, T.-K. & Kan, C.-K. Correlates of sleep irregularity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 270, 705–714 (2018).

Salvi, V. et al. Cardiovascular risk in patients with severe mental illness in Italy. Eur. Psychiatry 63, e96 (2020).

Komuro, J. et al. Sex differences in the relationship between schizophrenia and the development of cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e032625 (2024).

Carliner, H. et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among racial and ethnic minorities with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders: a critical literature review. Compr. Psychiatry 55, 233–247 (2014).

Soffer, D. E. et al. Role of apolipoprotein B in the clinical management of cardiovascular risk in adults: an expert clinical consensus from the national lipid association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 18, e647–e663 (2024).

Rao, W., Zhang, Y., Li, K. & Zhang, X. Y. Association between cognitive impairment and apolipoprotein A1 or apolipoprotein B levels is regulated by apolipoprotein E variant rs429358 in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Aging 13, 16353–16366 (2021).

Liu, H. et al. Association between lipid metabolism and cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 13, 1013698 (2022).

Morris, G. et al. The role of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein A and paraoxonase-1 in the pathophysiology of neuroprogressive disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 125, 244–263 (2021).

Fan, Y. et al. The Variants at APOA1 and APOA4 Contribute to the Susceptibility of Schizophrenia With Inhibiting mRNA Expression in Peripheral Blood Leukocytes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 785445 (2021).

Cortés, B., Bécker, J., Mories Álvarez, M. T., Marcos, A. I. S. & Molina, V. Contribution of baseline body mass index and leptin serum level to the prediction of early weight gain with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 68, 127–132 (2014).

Lago, S. G. et al. Peripheral lymphocyte signaling pathway deficiencies predict treatment response in first-onset drug-naïve schizophrenia. Brain. Behav. Immun. 103, 37–49 (2022).

Alver, M. et al. Genetic predisposition and antipsychotic treatment effect on metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia: a ten-year follow-up study using the Estonian Biobank. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 41, 100914 (2024).

Liang, J., Guan, X., Sun, Q., Hao, Y. & Xiu, M. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and cognitive performances in first-episode patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 135, 111092 (2024).

Gao, Z., Li, B., Guo, X., Bai, W. & Kou, C. The association between schizophrenia and white blood cells count: a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Psychiatry 23, 271 (2023).

Jackson, A. J. & Miller, B. J. Meta-analysis of total and differential white blood cell counts in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 142, 18–26 (2020).

Xu, H. et al. Relation between unconjugated bilirubin and peripheral biomarkers of inflammation derived from complete blood counts in patients with acute stage of schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 13, 843985 (2022).

Lappé, J. M. et al. Red cell distribution width, C-reactive protein, the complete blood count, and mortality in patients with coronary disease and a normal comparison population. Clin. Chim. Acta 412, 2094–2099 (2011).

Izzi, B., Bonaccio, M., De Gaetano, G. & Cerletti, C. Learning by counting blood platelets in population studies: survey and perspective a long way after Bizzozero. J. Thromb. Haemost. 16, 1711–1721 (2018).

Cabello-Rangel, H., Basurto-Morales, M., Botello-Aceves, E. & Pazarán-Galicia, O. Mean platelet volume, platelet count, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 14, 1150235 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Meta-analysis of peripheral mean platelet volume in patients with mental disorders: comparisons in depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Brain Behav. 13, e3240 (2023).

Özdin, S. & Böke, Ö Neutrophil/lymphocyte, platelet/lymphocyte and monocyte/lymphocyte ratios in different stages of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 271, 131–135 (2019).

De Campos-Carli, S. M. et al. Cannabinoid receptors on peripheral leukocytes from patients with schizophrenia: evidence for defective immunomodulatory mechanisms. J. Psychiatr. Res. 87, 44–52 (2017).

Tabata, N. et al. Predictive value of the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in cancer patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC CardioOncol. 1, 159–169 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Association of innate versus specific immunity with heart failure incidence: a prospective study. Heart 111, 76–82 (2025).

Yang, X. et al. Systemic inflammation indicators and risk of incident arrhythmias in 478,524 individuals: evidence from the UK Biobank cohort. BMC Med. 21, 76 (2023).

Khoodoruth, M. A. S. et al. Peripheral inflammatory and metabolic markers as potential biomarkers in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Insights from a Qatari Cohort. Psychiatry Res. 344, 116307 (2025).

Fang, S.-H. et al. Associations between sleep quality and inflammatory markers in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 246, 154–160 (2016).

Czekus, C. et al. Alterations in TRN-anterodorsal thalamocortical circuits affect sleep architecture and homeostatic processes in oxidative stress vulnerable Gclm−/− mice. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4394–4406 (2022).

Miller, B. J., McCall, W. V., McEvoy, J. P. & Lu, X.-Y. Insomnia and inflammation in phase 1 of the clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness study. Psychiatry Res. 305, 114195 (2021).

Lee, E. E. et al. Sleep disturbances and inflammatory biomarkers in schizophrenia: focus on sex differences. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 27, 21–31 (2019).

Van Dalfsen, J. H. & Markus, C. R. The influence of sleep on human hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity: a systematic review. Sleep. Med. Rev. 39, 187–194 (2018).

Marik, P. E. Glucocorticoids in sepsis: dissecting facts from fiction. Crit. Care 15, 158 (2011).

Rao, R., Somvanshi, P., Klerman, E. B., Marmar, C. & Doyle, F. J. Modeling the influence of chronic sleep restriction on cortisol circadian rhythms, with implications for metabolic disorders. Metabolites 11, 483 (2021).

Pillinger, T. et al. Antidepressant and antipsychotic side-effects and personalised prescribing: a systematic review and digital tool development. Lancet Psychiatry 10, 860–876 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the doctors, nurses, and IT technicians from the psychiatric hospitals for their support in generating and organizing the electronic clinical records. Additionally, we appreciate the Pineal Body Sleep Psychology Clinic in Kunming, Yunnan Province, China, for their assistance in facilitating communication for our multi-center research collaboration. Finally, we would like to express our gratitude for the support provided by the Beijing Research Ward Demonstration Project. Supports were received from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171507), Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (2022-1-2131), High-level public health technical talent construction project of Beijing Municipal Health Commission (Leading Talent-03-04), and the Research Project of Chuxiong Medical College (2024YYXM36).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P.W., Z.D. and Y.L.T. designed the study. G.P.W., Z.C.L., Q.X.Z., L.Q.H. and Y.R.Z. contributed to the data collection. G.P.W., Z.D., S.C., X.W., S.C., S.M.B. and Y.L.T. conducted data analysis and interpretation. G.P.W. and Z.D. drafted the manuscript. G.P.W., Z.C.L., Q.X.Z., L.Q.H., Q.D., B.P.T. and Y.L.T. contributed administrative, technical, or material support. Y.L.T. and H.B.L. supervised the draft and revision of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all the listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of the Ethics Committee of Peking University Huilongguan School of Clinical Medicine [(2023) Research No. 104].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, G., Dong, Z., Li, Z. et al. Comorbidity patterns and immune-metabolic differences in patients with acute-episode of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr 11, 102 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00646-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00646-6

This article is cited by

-

B cell pathways implicate shared genetic architecture between schizophrenia and immune-mediated diseases

Journal of Translational Medicine (2026)