Abstract

Schizophrenia has been linked to reduced cortical thickness and abnormal gene expression. While antipsychotic treatment has been found to affect cortical morphology and gene expression, its impact on subject-specific deviations in cortical morphometric similarity and the underlying genetic mechanisms remain unclear. To quantify risperidone-related changes in morphometric similarity at the individual level and test their spatial alignment with cortical transcriptomic patterns. Twenty-four drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia patients and 30 healthy controls underwent T1-weighted imaging scans. Patients were scanned before and after 12 weeks of treatment with risperidone; symptoms and cognitive function were assessed with PANSS and MCCB scale. For each scan, cortical morphometric similarity matrices were built from regional cortical thickness distributions using the Wasserstein distance. We defined Morphometric Similarity Deviation (MSD) as a subject-level, normative-referenced departure from the healthy morphometric similarity pattern, derived from node-wise fingerprint correlations with the healthy template. Partial least squares regression related treatment-induced MSD changes to cortical transcriptomic data obtained from the Allen Human Brain Atlas. Patients exhibited high MSD in the frontal, temporal, and temporoparietal regions. Greater baseline MSD across the whole brain and multiple networks were associated with more severe positive symptoms. After treatment, MSD decreased, and reductions within the salience/ventral attention network associated with improved Emotional Intelligence. Moreover, risperidone-induced changes in MSD were spatially correlated with the expression of specific genes enriched in neurotransmission, cell adhesion, immune function, and schizophrenia. Specific expression analyses revealed that these genes were specifically expressed in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, and spanned almost all developmental stages. Risperidone reduces MSD, reflecting convergence toward a normative cortical morphometric similarity pattern. These changes were spatially aligned with gene expression patterns involved in neurotransmission and immune processes, suggesting a molecular basis for treatment-linked structural normalization and its cognitive benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder primarily treated with antipsychotic medications. Previous studies have examined the relationship between antipsychotics and cortical morphology1,2. Xiao et al. reported that antipsychotic drugs may protect white matter in chronic schizophrenia patients, particularly in the corpus callosum, as untreated patients exhibit more severe white matter damage and faster deterioration with age3. A prospective longitudinal study indicated that short-term acute phase treatment with risperidone significantly increased cortical thickness, with greater increases being associated with better clinical responses4. A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies showed a correlation between gray matter volume decreases and cumulative exposure to antipsychotic treatments5. Although these studies have highlighted the effects of antipsychotic medications on specific brain regions, they do not address the coordinated interactions between regions, a gap that is particularly pronounced in drug-naive first-episode (DNFE) schizophrenia patients. Investigating DNFE patients reduces the confounding effects of disease duration and previous treatments, providing clearer insights into the impact of antipsychotic medications on brain structural networks.

Schizophrenia is characterized by widespread cortical thinning with a prominent frontotemporal pattern6,7, suggesting disrupted cross-regional morphometric coordination and an imbalance of large-scale network organization. Traditional morphometric metrics focus on local abnormalities and thus provide limited insight into the global inter-regional associations underlying structural change. In contrast, “statistical connectivity” approaches based on structural covariance or morphometric similarity capture coordinated structural patterns across regions and have been closely linked to clinical symptoms, cognition, and illness progression in schizophrenia. This network-based framework offers a valuable perspective for understanding structural dysregulation in schizophrenia and its potential plasticity under antipsychotic treatment. A recent review highlighted reorganized structural coordination within frontotemporal, frontoparietal, and thalamo-frontal networks in schizophrenia, with such abnormalities closely associated with symptomatology and cognitive impairment8. The observed reductions in whole-brain morphometric similarity, especially the pronounced weakening of frontotemporal coupling, highlight disrupted inter-regional coordination as a key expression of system-level imbalance9. Although still limited, emerging evidence has begun to outline how antipsychotic treatment may influence morphometric similarity. Jiang et al. reported that treatment responders showed strengthened cortico-cortical covariance and higher global efficiency after 12 weeks, with stabilized covariance centered on frontotemporal hubs10. Similarly, Tsugawa et al. found increased covariance along frontotemporal and fronto-occipital pathways in non-treatment-resistant patients—changes that were negatively correlated with symptom severity—whereas treatment-resistant patients lacked such patterns11. Collectively, these findings suggest that antipsychotic medications may promote partial recovery of network-level organization by reshaping inter-regional structural coordination, and that these effects may be closely tied to clinical improvement.

Despite providing important insights into disrupted structural coordination in schizophrenia, existing frameworks have notable limitations in individualized and fine-grained characterization. Structural covariance relies on group-level correlation estimates and therefore cannot be constructed at the individual level12,13,14. Although morphometric similarity networks integrate multiple structural features, they are derived from region-averaged measurements and inevitably lose vertex-level granularity15. Meanwhile, schizophrenia is marked by substantial inter-individual heterogeneity, and traditional case–control designs primarily capture group differences rather than delineating abnormal brain maps or treatment-related changes at the single-subject level16. To address these limitations, we leverage a vertex-level, distribution-based similarity modeling approach and derive an individualized morphometric similarity deviation (MSD) index. Specifically, for each participant, we compare the empirical distributions of cortical thickness within pairs of regions and quantify their divergence using the Wasserstein distance17. Unlike traditional divergence-based measures, this metric does not require one-to-one vertex correspondence, does not assume overlapping value ranges, is robust to differences in vertex counts, and provides a geometrically interpretable notion of minimal transport cost. The resulting morphometric similarity network is constructed at the individual level and aligned to a normative reference network to obtain subject-specific deviation maps. This approach offers a promising individual-level quantitative framework for characterizing abnormalities in structural coordination and their plasticity under antipsychotic treatment.

Increasing evidence indicates that the effects of antipsychotic medications are not limited to classical receptor blockade, but also involve remodeling of postsynaptic density architecture, restoration of dendritic spine formation, and reversal of synaptic damage induced by inflammation or glutamatergic imbalance18,19. Howes et al. further propose that immune–synaptic interactions may represent a viable therapeutic target, drawing on evidence from multiple immune-related genetic risk factors, increased microglial density, and reduced synaptic terminal density in schizophrenia20. Drug-induced synaptic plasticity remodeling is often mirrored at the systems level by concomitant alterations in resting-state functional connectivity and large-scale network organization21,22,23,24, suggesting that these macroscopic network effects may reflect modulation of the immune–synaptic pathway. Moreover, imaging–transcriptomic analyses have shown that cortical patterning of abnormal morphometric similarity in psychosis correlates with the expression of genes enriched for nervous system development and synaptic signaling, as well as genes previously associated with schizophrenia and antipsychotic treatment9,25. Based on this framework, we hypothesize that risperidone-induced convergence of individual MSD toward a healthy pattern may be related to the spatial expression profiles of neurotransmission- and immune-related gene sets.

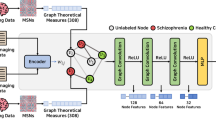

To test this hypothesis, we examined individual MSD maps in DNFE patients with schizophrenia before and after acute risperidone treatment, and assessed whether treatment-related changes in MSD were associated with improvements in clinical symptoms and cognitive function. To strengthen the robustness of our findings, we reconstructed an independent normative morphometric similarity network using the large-scale HCP dataset and repeated the MSD analyses, and additionally recalculated similarity using the Jensen–Shannon (JS) divergence in place of the Wasserstein distance to evaluate whether the core results were consistently supported across different similarity measures. Furthermore, leveraging the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA), we performed partial least squares (PLS) regression to link individual MSD changes to cortical gene expression, thereby identifying treatment-related gene sets and conducting functional enrichment and cell-type–specific expression analyses. A schematic overview of the analysis pipeline is shown in Fig. 1.

A Individual cortical thickness similarity network constructed using the Wasserstein distance to produce a 400 × 400 matrix (depicted by a subdivision of the Schaefer 400-parcels). B Morphometric Similarity Deviation (MSD) were calculated to characterize the deviation in cortical thickness similarity of specific brain regions to the rest of the brain in single patient relative to healthy controls. C T-statistic map was constructed using paired t-tests. Partial least squares (PLS) regression was then used to identify imaging-transcriptomic associations. Finally, enrichment analysis was performed on the gene list associated with the first component of PLS (PLS1). SZ0W, schizophrenia at baseline; SZ12W, schizophrenia at 12 weeks post-treatment.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study included 24 patients with DNFE schizophrenia, selected from an initial cohort of 39, who completed 12 weeks of treatment with risperidone and follow-up MRI scans26. Of the 39 enrolled, 27 completed the protocol; 5 discontinued due to medication switch, and 7 lacked post-treatment MRI data. Three of these 27 were excluded for excessive head motion in the resting-state fMRI scan. The remaining 24 patients constituted the final sample and were used for all subsequent analyses. Patient inclusion criteria were: (1) met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, with the diagnosis established by two trained psychiatrists using the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID)27; (2) illness duration < 5 years; and (3) no prior exposure to antipsychotics.

Thirty healthy control subjects without any family or personal history of mental disease were recruited from the local community during the same period through advertisements. The control group was meticulously matched with DNFE patients in terms of gender, age, and education. The demographic and clinical characteristics of all participants are summarized in Table 1.

Medication and clinical assessments

In this study, all schizophrenia patients were hospitalized and received risperidone as a monotherapy for a duration of 12 weeks. Dosing started at 1 mg/day and gradually increased to 3–6 mg/day based on the individual’s response and tolerability within the first week. Additional procedural details are available in our prior report28. Psychiatric symptoms and cognitive functions were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)29 and the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB)30, respectively. These evaluations were performed both prior to the baseline (SZ0W) and after the 12-week treatment period with risperidone(SZ12W).

Data acquisition and preprocessing

T1w images were obtained using a 3 T General Electric scanner with 8-channel brain phased array and a 3D fast spoiled gradient-echo (FSPGR) sequence. Main imaging parameters were: TR = 6.2 ms, TE = 2.8 ms, slice thickness=1.2 mm, flip angle = 8°, field of view = 240 × 240 mm2, matrix = 256 × 256, voxel size = 0.94 × 0.94 × 1.2 mm3, and 142 sagittal slices. No parallel acceleration was applied. The total acquisition time was approximately 5–6 min.

All MRI data were processed using FreeSurfer (V6.0, http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/) with the default recon-all pipeline, without any manual intervention or additional smoothing applied prior to analysis. The pipeline includes tissue intensity inhomogeneity normalization, nonbrain tissue removal, transformation to Talairach-like space, and segmentation of gray/white matter tissue. Cortical thickness measurements were obtained by calculating the shortest distance from the gray/white boundary to the gray/cerebrospinal fluid boundary at each vertex on the tessellated surface31. Manual editing was not performed for any subject; all FreeSurfer outputs underwent visual inspection, with no apparent errors in skull stripping, intensity normalization, or tissue segmentation. Quality control of FreeSurfer reconstructions additionally used the Euler number as an index of surface reconstruction quality; following established practice, subjects with median-centered absolute Euler numbers > 25 were excluded. No participants exceeded this threshold.

Construction of single-subject cortical thickness similarity network

In this study, we constructed a single-subject cortical thickness similarity matrix for each participant, where nodes represented brain regions and edges denoted the morphological similarity between them. Brain regions were defined using the Schaefer 2018 atlas (7-network, 400 parcels)32, which parcellates the cortical surface into 400 regions of interest assigned to seven functional networks: visual (Vis), somatomotor (SomMot), dorsal attention (DorsAttn), salience/ventral attention (SalVentAttn), limbic, control (Cont), and default.

To quantify the edges between the nodes, we employed the Wasserstein distance due to the discrete nature of brain region morphological features17. For each subject, vertex-wise cortical thickness values within each region were first cleaned by removing zero-valued vertices and then z-scored, and the resulting empirical distributions were used to characterize regional cortical morphology. The Wasserstein distance measures the minimal “effort” required to transform one probability distribution into another, which in this context reflects the dissimilarity between the cortical thickness distributions of two brain regions. Specifically, for brain regions A and B, with cortical thickness distributions represented by \({P}_{A}\) and \({P}_{B}\), the Wasserstein distance \(W\left({P}_{A},{P}_{B}\right)\) is calculated as follows:

Where \({\gamma }_{{ij}}\) represents the transfer probability between the i-th vertex in \({P}_{A}\) and the j-th vertex in \({P}_{B}\), and \(d\left(i,j\right)\) denotes the distance between vertex i and j. \(\Pi \left({P}_{A},{P}_{B}\right)\) represents the set of all possible ways to match vertices between the two regions, from which the minimum value is selected to compute the distance. We adopted the Wasserstein distance because it accommodates unequal vertex counts and nonoverlapping value ranges, and provides clear geometric interpretability, making it well suited for comparing independently sampled cortical thickness distributions.

Calculation of morphometric similarity deviation

After acquiring the cortical thickness similarity matrix of cortical thickness, the average standard cortical thickness similarity matrix for the healthy control group, denoted as \({{\rm{W}}}_{\mathrm{Mean}\mathrm{HCs}}\), was obtained by averaging the cortical thickness similarity matrices. For each patient \({\rm{p}}\) and each brain region \({\rm{i}}\), the row-wise correlation between the pre-and post-treatment cortical thickness similarity matrix \({\rm{Wp}}({\rm{i}})\) and the corresponding row of \({{\rm{W}}}_{\mathrm{Mean}\mathrm{HCs}}\left({\rm{i}}\right)\) was calculated. Subsequently, the MSD value for each region was then derived by subtracting this correlation value from 1, using the formula:

Here, \({MSD}(\text{i})\) represents the degree to which the cortical thickness similarity for each brain region in the patient deviates from the average similarity observed in healthy controls.

Construction of t-statistic maps

We constructed t-statistic maps to investigate treatment-related differences in MSDs using paired t-tests, providing insight into the temporal dynamics of morphological changes within the studied population. False positive effects were controlled using False Discover Rate (FDR, P < 0.05) correction.

Validation analyses

To assess robustness and generalizability, we performed two complementary validations: (1) We repeated the pipeline with alternative parcellations (Schaefer-200/600) and, as a complementary metric, substituted the 1-Wasserstein distance with Jensen–Shannon divergence while keeping data and parcellations identical. (2) We reconstructed the normative model using the Human Connectome Project –Young Adult dataset (N = 1071) and recomputed MSD in our cohort under Schaefer-400 and Destrieux atlas33 (the latter mapped to Yeo-7 networks via vertex-wise winner-take-all, Fig. S1). Detailed methods are provided in the Supplement Materials.

Correlation analyses of MSD with symptoms and cognition

Additionally, Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the association between baseline MSD and clinical symptoms or cognitive performance (PANSS scores and MCCB scores), and longitudinal alterations in MSD and corresponding changes in clinical symptoms and cognitive performance (SZ12W – SZ0W). Multiple comparisons were controlled using FDR correction at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Imaging-transcriptomic analysis

We used the AHBA transcriptomic dataset with gene expression measurements in six post mortem adult brains (http://human.brain-map.org) ages 24–57 years. Then, the abagen toolbox in Python was used to create a whole-genome expression atlas by probe-to-gene and sample-to-region strategies using the following steps: (1) intensity-based filtering of microarray probes to remove those that do not exceed background noise of 50%; (2) selection of a representative probe for each gene across each hemisphere; (3) matching of microarray samples to brain parcels from the Schaefer-400 atlas; and (4) normalization, and aggregation within parcels and across donors. This resulted in a 2D matrix that showed gene expression levels of 15631 genes on 400 Schaefer cortical regions.

We used PLS to relate the regional morphometric similarity treatment-related differences (t-statistic from the 400 cortical regions) to the post mortem gene expression measurements for all 15631 genes. PLS uses the gene expression measurements (the predictor variables) to predict the regional morphometric similarity treatment-related t-statistics. The first component (PLS1) detected in the PLS analysis was the linear combination of gene expression that was most robustly related to t-statistic map. To assess the significance of this association, we performed 10,000 permutations using spherical rotations of the t-statistic map to account for spatial autocorrelation, testing the null hypothesis that PLS1 explained no more covariance between gene expression and the observed t-statistics than would be expected by chance. Bootstrapping (1000 resamples) was performed to estimate the variability of each gene’s weight on PLS1. For each gene, the ratio of its weight to the bootstrap-estimated standard error was calculated to derive a Z-score, which reflects the stability and contribution of that gene to the PLS1 component. Genes were then ranked based on their absolute Z-scores to identify the most strongly contributing genes.

Functional enrichment analysis

We conducted functional enrichment analysis from the genes with PLS1 weight Z > 3 or Z < -39, using ToppGene-ToppFun (https://toppgene.cchmc.org/), a computational online free-access tool for functional enrichment analysis of the candidate genes. Gene ontology (GO) was adopted to assess biological functions including molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components. The disease was used to assess the related diseases. Furthermore, cell-type-specific expression analysis (CSEA) Web tool (http://genetics.wustl.edu/jdlab/csea-tool-2/) were utilized to conduct cell type and temporal specific expression analyses, with the aim of determining the specific cortical cell types and developmental stages in which these genes were overrepresented. A specificity index probability (pSI) was used to index how genes are more enriched in specific terms relative to others and four pSI thresholds (0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001) were employed in this analysis. For the aforementioned enrichment analyses, Fisher’s exact tests were conducted to evaluate their statistical significance, and multiple testing was corrected using the Benjamini and Hochberg method for false discovery rate (BH-FDR correction) with a corrected p value of 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing HuiLongGuan hospital (No. SCH-A01). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Results

Risperidone treatment effects on MSD

Spatial analysis revealed higher MSD in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and temporoparietal junction. After 12 weeks of risperidone treatment, there was a notable reduction in MSD across the whole brain (Fig. 2A). Positive and negative t-values indicated increases or decreases in MSD post-treatment compared to pre-treatment. No significant difference was found at the brain level after FDR correction.

A Group-averaged z-maps of MSD at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment, along with the paired t-statistic map. Warm colors (red) in the first two maps indicate greater variability; cool colors (blue) indicate lower variability. In the t-map, red denotes increases and blue denotes decreases in MSD following treatment. B Boxplots showing group-level individual variability at the whole-brain and functional network levels. Orange and blue represent SZ0W and SZ12W, respectively. Asterisks denote statistically significant reductions after FDR correction (*pFDR < 0.05). Network labels: Vis, visual; SomMot, somatomotor; DorsAttn, dorsal attention; SalVentAttn, salience/ventral attention; Cont, control; SZ0W, schizophrenia at baseline; SZ12W, schizophrenia at 12 weeks post-treatment.

Paired t-tests conducted on network-level MSD revealed that, compared to pre-treatment, post-treatment MSD decreased in the whole brain (t = −2.634, p = 0.0148, pFDR = 0.0303), Vis network (t = −2.636, p = 0.0148, pFDR = 0.0303), SomMot network (t = −2.442, p = 0.0227, pFDR = 0.0303), DorsAttn network (t = −2.850, p = 0.0091, pFDR = 0.0303), SalVentAttn network (t = −2.491, p = 0.0204, pFDR = 0.0303), Limbic system (t = −2.263, p = 0.0334, pFDR = 0.0382), and Default network (t = −2.508, p = 0.0197, pFDR = 0.0303), with no statistical difference observed in the Cont network (Fig. 2B).

The validation analyses (Supplementary Materials) showed that the Wasserstein distance consistently captured post-treatment MSD reductions across different parcellation schemes, reaching statistical significance at both whole brain and network levels after FDR correction. In contrast, although the JS divergence failed to detect significant treatment effects, it still revealed a consistent post-treatment downward trend in MSD. Additionally, spatial correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between the two methods in the spatial distribution of static abnormal patterns, but a lower consistency in the t-map reflecting treatment changes. Detailed results are provided in the supplementary materials (Figs. S2–S4). Moreover, validation using the HCP-based normative model revealed concordant MSD reductions at the whole-brain and network levels post-treatment (Figs. S5–S7).

Statistical power analyses indicated convergent evidence across normative references (original vs. HCP-based) and parcellations (Schaefer-400 vs. Destrieux), with post-treatment MSD reductions showing predominantly moderate-to-upper effect sizes and adequate statistical power for the FDR-significant contrasts. (Supplementary Tables S1–S4).

MSD correlates with clinical symptoms and cognitive performance

To test the relationship between the changes in MSD and the improvement of clinical symptoms and cognitive performance, correlation analysis was conducted. Before treatment, patients showed positive correlations between positive symptom scores and MSD at the whole brain level (r = 0.470, pFDR = 0.0368), within the Vis network (r = 0.500, pFDR = 0.0368), Cont network (r = 0.448, pFDR = 0.0375), SalVentAttn network (r = 0.462, pFDR = 0.0368), limbic system (r = 0.473, pFDR = 0.0368), and default network (r = 0.474, pFDR = 0.0368), as shown in Fig. 3.

After treatment, across all MCCB domains, only one significant association was observed: with increased Emotional Intelligence Test (EIT) score, the SalVentAttn network showed decreased MSD (r = 0.577, p = 0.015, uncorrelated; Fig. 4). No other domains reached significance; we noted nominal trends whereby greater improvement in Digit Sequencing score was associated with decreased MSD in the Limbic (r = 0.481, p = 0.059, uncorrelated) and Default (r = 0.434, p = 0.093, uncorrelated) networks.

Genes associated with treatment-induced MSD

We used PLS regression to identify patterns of gene expression that were correlated with the treatment-related MSD. PLS1, defined as the linear combination of genes most strongly associated with the regional t-statistic map, explained 23% of the variance in the t-statistics (pspin =0.0013, 10,000 spherical-rotation permutations to preserve spatial autocorrelation).The distribution of PLS1 weighted map reflects an anterior-posterior gradient of gene expression (Fig. 5A). Notably, We found that the PLS1 weighted gene expression map was spatially correlated with the treatment-related t-statistic map in the paired comparison between SZ0W and SZ12W (Pearson’s r(400) = 0.289, pspin < 0.0001; Fig. 5B). We ranked the normalized weights of PLS1 based on univariate one-sample Z tests. We found 430 PLS1 + (Z > 3) and 658 PLS1 − (Z < − 3) (all pFDR < 0.05; Fig. 5C) positively (or negatively) weighted gene expressions were overexpressed (or under-expressed) as increased (or decreased) regional changes in MSD, respectively. In total, 1088 genes constituted the regional change in MSD gene list in individuals with schizophrenia (Supplementary File 1). These positive correlations mean that genes positively weighted on PLS1 are overexpressed in regions where morphometric similarity was increased in patients, while negatively weighted genes are overexpressed in regions where morphometric similarity was decreased in patients (Fig. 5D).

A A weighted gene expression map of regional PLS1 scores. B A scatterplot of regional PLS1 scores and regional changes in MSD (r = 0.289, pspin < 0.0001, permutation tests with spatial autocorrelation corrected, 10,000 times). The shadow indicates the 95% confidence intervals. Each dot represents a region. C Ranked PLS1 loadings. D Genes that are strongly positively weighted on PLS1 (e.g., PRSS16) correlate positively with regional changes in MSD (r = 0.201, pspin = 7.5e-4), whereas genes that are strongly negatively weighted on PLS1 (e.g., PTPRZ1) correlate negatively with regional changes in MSD (r = -0.194, pspin = 0.01).

Gene enrichment results

To delineate the biological functions and diseases with alterations in individual MSD, we conducted functional enrichment analyses using the ToppGene portal. After correcting for multiple comparisons (pBH-FDR < 0.05), we identified the top fifteen significant GO terms across molecular functions, biological processes, and cellular components. As shown in Fig. 6A, the PLS1+ gene list showed high expression in cellular components such as the synapse, synaptic membrane, postsynapse, and neuron projections, and was enriched in biological processes like synaptic signaling, trans-synaptic signaling, and chemical synaptic transmission. Additionally, these genes were prominently enriched in molecular functions related to ion channels and transmembrane transporter activities. With respect to diseases, the PLS+ gene list was enriched in schizophrenia and epilepsy. Detailed enrichment results for the PLS1+ genes can be found in Supplementary File 2. As shown in Fig. 6B, the PLS1- gene list associated with MSD recovery primarily involves cellular interactions and immune regulation. Specifically, these genes were enriched in regulating cell adhesion, cell-cell adhesion, and the formation and function of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) protein complexes. Additionally, our observations indicate their involvement in the processing and presentation of exogenous antigens, particularly through the antigen processing and presentation via MHC class II molecules. Regarding diseases, the PLS- gene list was enriched in several psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Detailed enrichment results for the PLS1+ genes can be found in Supplementary File 3.

A The bubble diagram showing the enrichment of GO terms and disease PLS1+ genes. B The bubble diagram showing the enrichment of GO terms and disease PLS1- genes. The x-axis shows rich factor and the y-axis shows items. The x-axis represents -log10(adj. p value) corrected by BH-FDR method. The globule size represents the number of genes overlapping with those belonging to each item, and the globule color represents statistical significance. The rich factor refers to the ratio of the number of significant genes annotated to the item to the number of all genes annotated to the item. GO, gene ontology.

Cell specific expression analysis revealed that PLS1- gene list was specifically expressed in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells and astrocytes of cortex (Fig. 7A). For the PLS1+ genes, no significant enrichment was observed in any cell types. As shown in Fig. 7B, temporal specific expression analysis revealed that PLS1+ genes were expressed in the brain from neonatal early infancy. The PLS1- genes were expressed predominantly in early fetal and early middle fetal.

A The CSEA analysis revealed a significant association between the PLS1- genes and both oligodendrocyte and astrocytes. B Temporal specific expression analysis indicated that PLS1+ genes express post-late fetal stage, whereas PLS- genes express earlier. The color represents adjusted p values (BH-FDR). The sizes of the hexagons denote temporal specificity across different specificity index probability (pSI) statistic thresholds ranging from 0.05 to 1e-4. The outer hexagons correspond to the least specific test for a cell type (pSI threshold = 0.05), whereas the innermost hexagon reflects the most specific test for a cell type (pSI threshold = 1e-4). OPC, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells; Immu, immune cells; Pnoc + , prepronociceptin-expressing neurons; Ntsr + , corticothalamic neurons; Glt25d2, corticopontine neurons; Astro, Astrocytes; Cort + , corticosterone-expressing neurons; Myeli, myelinating oligodendrocytes; pSI, specificity index probability.

Discussion

This study constructs maps of MSD in patients with DNFE schizophrenia before and after risperidone treatment using cortical thickness similarity networks and investigates the genetic mechanisms underlying risperidone-induced changes in morphological similarity through transcriptome-neuroimaging spatial correlation. The results indicate that patients exhibit higher MSD in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and the temporoparietal junction. Additionally, higher baseline MSD across the whole brain and multiple network levels were associated with more severe positive symptoms. Following treatment, the reduction in MSD was observed across the entire brain and multiple networks. Notably, the change in MSD within the SalVentAttn network was positively associated with the change of EIT score. Furthermore, the changes of MSD were spatially associated with the expression of 1088 genes, which were enriched for neurotransmission, cell adhesion, immune function, and psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia. Specific expression analyses demonstrated that PLS- genes were specifically expressed in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. On the other hand, PLS- genes were expressed before late fetal stages, while PLS+ genes were expressed thereafter, spanning almost all developmental stages. In conclusion, our findings indicate that, in DNFE schizophrenia, risperidone treatment is associated with reduced MSD—reflecting a convergence toward the normative cortical morphometric similarity pattern—and that the spatial distribution of these changes aligns with gene-expression programs enriched for neurotransmission, cell adhesion, immune processes, and psychiatric disorders.

Previous studies have reported significant reductions in cortical thickness in patients with schizophrenia34,35, especially in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes6,36,37,38, along with higher structural covariance compared to HCs11,39,40,41. Wannan et al. found that regions with reduced cortical thickness in schizophrenia exhibit higher structural covariance than regions without significant differences, indicating that morphological changes in the brain are interrelated rather than occurring in isolation6. Our results support this, revealing greater MSD in these regions, reflecting inconsistency in connectivity patterns and reduced overall network coordination. Additionally, higher MSD at both whole brain and network levels are linked to more severe positive symptoms. Previous studies have already established a correlation between widespread cortical morphological abnormalities and positive symptoms; for instance, reduced thickness in the lateral prefrontal and temporal regions correlates with positive thought disorders42, while thinning in the temporal cortex relates to hallucinations43. These findings indicate that structural abnormalities in specific regions may contribute to positive symptoms. Our results further suggest that the link between higher MSD and symptom severity reflects network-level dysfunction. Specifically, local morphological changes may disrupt brain network coordination by altering connectivity patterns6, leading to functional imbalances44 and more pronounced positive symptoms in schizophrenia.

Accumulating evidence shows that antipsychotic medications can induce brain morphological alterations45,46, with effects varying across regions and spatial scales. Goghari et al. found that short-term treatment with risperidone or quetiapine increases cortical thickness in the prefrontal cortex of DNFE patients with schizophrenia47. Furthermore, typical (FGA) and atypical (SGA) antipsychotics exhibit divergent effects on cortical thickness: higher cumulative FGA exposure is associated with more pronounced cortical thinning, whereas higher SGA exposure corresponds to attenuated thinning, suggesting that SGAs may partly counteract cortical thinning48. Beyond the cortex, meta-analytic and subgroup studies have demonstrated that greater medication exposure is linked to reduced parietal volumes and enlarged basal ganglia49, with gray matter reductions observed in frontal and temporal regions and volume increases in the putamen, caudate, and globus pallidus50. Diffusion tensor imaging studies further indicate that treatment modulates white matter microstructure, reflected in fractional anisotropy reductions within frontal and parietal tracts, radiations, and the corpus callosum51,52, some of which correlate with changes in positive symptoms and processing speed53. It is worth noting, however, that other reviews and longitudinal studies have reported no consistent relationship between antipsychotic dose/type and cortical change1,54, implying that these effects likely depend on disease stage, cumulative exposure, and individual treatment response. At the network level, accumulating evidence indicates that antipsychotic treatment can drive reorganization of structural brain networks and that such reconfiguration is closely linked to clinical response. Diffusion-tensor tractography suggests partial reversal of anatomical connectivity following treatment55. Jiang et al. reported enhanced cortico-cortical structural covariance and higher global efficiency in treatment responders, with weaker or absent changes in non-responders10. Tsugawa et al. further showed that non-treatment-resistant patients exhibit increased covariance along fronto-temporal and fronto-occipital pathways that correlates negatively with symptom severity, a pattern not observed in treatment-resistant patients11. In addition, longitudinal studies of morphometric similarity networks have linked convergence toward normative patterns with improvements in cognition and general psychopathology56. Our study found that after 12 weeks of risperidone treatment, MSD at both whole-brain and network levels significantly decreased, consistent with convergence toward a more normative morphometric similarity pattern and with improved large-scale coordination. This effect extends beyond specific cortical areas to the network level10,11. Aligning with evidence that antipsychotic treatment engages multilevel structural plasticity, our results provide a normative-referenced, network-level quantitative complement to treatment-related morphometric plasticity.

Moreover, we observed that the reduction in MSD within the SalVentAttn network after treatment was positively associated with improved emotional regulation. Prior research has indicated that the salience network plays a pivotal role in modulating emotions by selectively inhibiting the processing of emotional information and responses57,58. The prefrontal cortex regions within this network are interconnected with neural circuits implicated in emotional regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex-subcortical-amygdala pathway59, contributing to the modulation of emotional information processing and responses60. The improvement in MSD may reflect a restoration of emotional regulation functions, suggesting that recovery within the SalVentAttn network helps patients cope with emotions more effectively and enhances their emotional management abilities.

Our imaging-transcriptome association analysis established a link between risperidone-related changes in MSD and gene expression enriched in neurotransmission, cell adhesion, and immune function. The PLS+ gene list is primarily involved in synaptic transmission and ion channel activity. Atypical antipsychotics, including risperidone, primarily treat schizophrenia by modulating neurotransmitters such as dopamine and 5-HT2A. Dendritic spines, the main sites on postsynaptic neurons that receive neurotransmitters released from presynaptic neurons, contain a high density of ion channels, including NMDA receptors, AMPA receptors, voltage-gated calcium channels, and potassium channels. Morphology changes in dendritic spines are driven by swelling caused by Ca2+-dependent actin polymerization61,62 and ion influx63,64. Antipsychotics may regulate NMDA receptor function through their signal transduction pathways, affecting Na+ and Ca2+ influx, which in turn alters dendritic spine morphology and density, thereby modulating the efficiency and strength of synaptic transmission65. Our results revealed a spatial correspondence between risperidone-related structural reconfiguration and cortical transcriptional patterns linked to synaptic and membrane functions. These findings highlight a potential alignment between the macroscale reconfiguration of cortical morphology and the intrinsic molecular architecture supporting neurotransmission and synaptic remodeling. Additionally, the enrichment of the PLS- gene list indicates involvement in processes related to cell adhesion and MHC protein complex-mediated antigen presentation. Intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM) play a crucial role in the interaction between T cells and antigen-presenting cells or target cells. ICAM-3, by binding to lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 on dendritic cells (DCs), can trigger the rearrangement of the cytoskeleton (primarily actin) within DCs, leading to the aggregation of MHC-II molecules on the DC surface, ultimately forming an immunological synapse at the site of DC-T cell contact, thereby enhancing antigen presentation and T cell activation66. Similarly, the effective binding of ICAM-1 on target cells leads to the recruitment of MHC-I proteins to the contact area and enhances the presentation of homologous peptide-MHC-I complexes to cytotoxic T cells67,68. By modulating these adhesion molecules and related antigen presentation processes, risperidone may reduce neuroinflammation, protect the normal functions of neurons and glial cells, and mitigate inflammation-induced disruption with neural networks. Overall, our results point to a spatial alignment between risperidone-related cortical reconfiguration and gene expression programs involved in neurotransmission, cellular adhesion, and immune regulation, providing a molecular context for understanding treatment-associated structural plasticity in schizophrenia.

Specific expression analysis demonstrated that genes associated with changes in MSD are specifically expressed in neurons and glial cells, enhancing confidence in interpreting our findings. Oligodendrocytes and astrocytes, two key types of glial cells, are crucial for maintaining neuronal function and regulating the extracellular environment. Specifically, oligodendrocytes are primarily involved in neuronal energy metabolism and nutrient supply69, while astrocytes regulate ion concentrations in the synaptic cleft, clear neurotransmitters, and remove metabolic waste, all of which are essential for maintaining neuronal function and homeostasis70. These glial-cell enrichments point to pathways that shape the neuronal milieu—including neuronal support and neurotransmitter handling—providing a plausible biological context for the observed changes. Notably, PLS⁺/PLS⁻ genes are expressed across multiple developmental stages, consistent with the ‘two-hit’ hypothesis of schizophrenia71. This theory posits that genetic or environmental disruptions during early brain development (the “first hit” in the prenatal and perinatal periods) set the stage for later vulnerabilities. The expression of PLS- genes during this period may be associated with initial abnormalities in brain structure and function. These initial disruptions lead to long-term susceptibilities that, when combined with additional stressors during adolescence and early adulthood (the “second hit”), can culminate in the onset of full-blown psychosis72,73. The expression of PLS+ genes during this latter period may influence brain plasticity and stress response. Overall, these gene expression patterns highlight the importance of genetic regulation across different developmental stages in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.

Our findings must be explained in light of some limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small due to the challenging requirement of DNFE schizophrenia individuals treated with risperidone. Therefore, results should be interpreted with caution, and future researches with large sample sizes are warranted. Second, this study only assessed MSD based on cortical thickness, and future research should consider a comprehensive range of morphological features. Third, the AHBA gene -expression maps are derived from postmortem tissue of six healthy donors, which constrains cross-group transcriptome–neuroimaging inference. Larger, patient-based datasets from DNFE schizophrenia cohorts are needed to validate the observed connectome–transcriptome associations. An additional limitation is that the residual motion/segmentation confounds cannot be entirely excluded for T1-weighted data; however, two-step quality control (visual inspection + Euler number) did not indicate excessive motion or segmentation failures in this cohort. Finally, the HCP-based normative model was used solely as a supplementary robustness check; although the HCP cohort differs from our clinical sample in demographic and site characteristics, our primary inferences rely on the normative model derived from our own healthy controls.

Conclusion

In summary, our neuroimaging findings suggest that individual-level structural connectivity heterogeneity in DNFE patients with schizophrenia is reduced following 12 weeks of risperidone treatment, with concurrent improvements in cognitive performance. Transcriptomic analysis further revealed that these imaging changes are spatially associated with genes involved in neurotransmission, cell-cell interaction, and immune function. This study highlights the relevance of assessing individual MSD in brain structural organization and suggests that antipsychotic treatment may partially normalize these patterns. Moreover, our findings provide insight into potential molecular processes associated with treatment-related changes, offering implications for developing more personalized therapeutic strategies.

Data availability

Data available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The codes for computing MSD in cortical similarity carried out in this paper are available at GitHub - liju-liu/Individual-difference.

References

Roiz-Santiañez, R., Suarez-Pinilla, P. & Crespo-Facorro, B. Brain structural effects of antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia: a systematic review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 13, 422–434 (2015).

Kubicki, M. & Lyall, A. E. Antipsychotics and their impact on cerebral white matter: part of the problem or part of the solution? Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 1056–1057 (2018).

Xiao, Y. et al. White matter abnormalities in never-treated patients with long-term schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 1129–1136 (2018).

Nelson, E. A. et al. A prospective longitudinal investigation of cortical thickness and gyrification in schizophrenia. Can. J. Psychiatry 65, 381–391 (2020).

Fusar-Poli, P. et al. Progressive brain changes in schizophrenia related to antipsychotic treatment? A meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 1680–1691 (2013).

Wannan, C. M. J. et al. Evidence for network-based cortical thickness reductions in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 552–563 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. Cortical thickness abnormalities at different stages of the illness course in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 560–570 (2022).

Prasad, K. et al. Structural covariance networks in schizophrenia: A systematic review Part I. Schizophr. Res. 240, 1–21 (2022).

Morgan, S. E. et al. Cortical patterning of abnormal morphometric similarity in psychosis is associated with brain expression of schizophrenia-related genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9604–9609 (2019).

Jiang, Y. et al. Antipsychotics effects on network-level reconfiguration of cortical morphometry in first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 48, 231–240 (2022).

Tsugawa, S. et al. Associations between structural covariance network and antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 50, 382–392 (2024).

Zielinski, B. A., Gennatas, E. D., Zhou, J. & Seeley, W. W. Network-level structural covariance in the developing brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18191–18196 (2010).

Alexander-Bloch, A., Raznahan, A., Bullmore, E. & Giedd, J. The convergence of maturational change and structural covariance in human cortical networks. J. Neurosci. 33, 2889–2899 (2013).

Evans, A. C. Networks of anatomical covariance. Neuroimage 80, 489–504 (2013).

Seidlitz, J. et al. Morphometric similarity networks detect microscale cortical organization and predict inter-individual cognitive variation. Neuron 97, 231–247.e7 (2018).

Marquand, A. F., Rezek, I., Buitelaar, J. & Beckmann, C. F. Understanding heterogeneity in clinical cohorts using normative models: beyond case-control studies. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 552–561 (2016).

Su, Z., Zeng, W., Wang, Y., Lu, Z.-L. & Gu, X. Shape classification using Wasserstein distance for brain morphometry analysis. Inf. Process Med Imaging 24, 411–423 (2015).

de Bartolomeis, A. et al. Linking inflammation, aberrant glutamate-dopamine interaction, and post-synaptic changes: translational relevance for schizophrenia and antipsychotic treatment: a systematic review. Mol. Neurobiol. 59, 6460–6501 (2022).

de Bartolomeis, A. et al. Antipsychotics-induced changes in synaptic architecture and functional connectivity: translational implications for treatment response and resistance. Biomedicines 10, 3183 (2022).

Howes, O., Cummings, C. & Heurich, M. Translation from genes to mechanism in schizophrenia: are immune-synaptic interactions the missing link? Biol. Psychiatry 90, 593–595 (2021).

Bassett, D. S. & Sporns, O. Network neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 353–364 (2017).

Huang, X.-F. & Song, X. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on neurites relevant to schizophrenia treatment. Med. Res. Rev. 39, 386–403 (2019).

Dzyubenko, E., Juckel, G. & Faissner, A. The antipsychotic drugs olanzapine and haloperidol modify network connectivity and spontaneous activity of neural networks in vitro. Sci. Rep. 7, 11609 (2017).

Barone, A. et al. A postsynaptic density immediate early gene-based connectome analysis of acute NMDAR blockade and reversal effect of antipsychotic administration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 4372 (2023).

Yao, G. et al. Cortical structural changes of morphometric similarity network in early-onset schizophrenia correlate with specific transcriptional expression patterns. BMC Med. 21, 479 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Glucose disturbances, cognitive deficits and white matter abnormalities in first-episode drug-naive schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 3220–3230 (2020).

First, M., Spitzer, R., Gibbon, M. & Williams, J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition. in (SCID-I/P) (2002).

Liu, L. et al. Neuroimaging markers of aberrant brain activity and treatment response in schizophrenia patients based on brain complexity. Transl. Psychiatry 14, 1–12 (2024).

Kay, S. R., Fiszbein, A. & Opler, L. A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261–276 (1987).

Shi, C. et al. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery (MCCB): co-norming and standardization in China. Schizophr. Res. 169, 109–115 (2015).

Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781 (2012).

Schaefer, A. et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb. Cortex 28, 3095–3114 (2018).

Destrieux, C., Fischl, B., Dale, A. & Halgren, E. Automatic parcellation of human cortical gyri and sulci using standard anatomical nomenclature. Neuroimage 53, 1–15 (2010).

Sun, S. et al. Meta-analysis of cortical thickness reduction in adult schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 48, E461–E470 (2023).

Rimol, L. M. et al. Cortical thickness and subcortical volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 41–50 (2010).

Shah, P. et al. Glutamatergic neurometabolites and cortical thickness in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: Implications for glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity. J. Psychiatr. Res. 124, 151–158 (2020).

Nesvåg, R. et al. Regional thinning of the cerebral cortex in schizophrenia: effects of diagnosis, age and antipsychotic medication. Schizophr. Res. 98, 16–28 (2008).

Goldman, A. L. et al. Widespread reductions of cortical thickness in schizophrenia and spectrum disorders and evidence of heritability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 467–477 (2009).

Yu, L. et al. Increased cortical structural covariance correlates with anhedonia in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia (Heidelb.) 9, 19 (2023).

Zugman, A. et al. Structural covariance in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: an approach based on graph analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res 71, 89–96 (2015).

Heinze, K. et al. Discrete alterations of brain network structural covariance in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 989–996 (2015).

Palaniyappan, L., Al-Radaideh, A., Gowland, P. A. & Liddle, P. F. Cortical thickness and formal thought disorder in schizophrenia: an ultra high-field network-based morphometry study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 101, 109911 (2020).

Cui, Y. et al. Auditory verbal hallucinations are related to cortical thinning in the left middle temporal gyrus of patients with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 48, 115–122 (2018).

Fornito, A., Zalesky, A. & Breakspear, M. The connectomics of brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 159–172 (2015).

Emsley, R. et al. Antipsychotic treatment effects and structural MRI brain changes in schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 53, 2050–2059 (2023).

Roiz-Santiáñez, R. et al. Effect of antipsychotic drugs on cortical thickness. A randomized controlled one-year follow-up study of haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine. Schizophr. Res. 141, 22–28 (2012).

Goghari, V. M. et al. Effects of eight weeks of atypical antipsychotic treatment on middle frontal thickness in drug-naïve first-episode psychosis patients. Schizophr. Res. 149, 149–155 (2013).

van Haren, N. E. M. et al. Changes in cortical thickness during the course of illness in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 871–880 (2011).

Smieskova, R. et al. The effects of antipsychotics on the brain: what have we learnt from structural imaging of schizophrenia?--a systematic review. Curr. Pharmaceutical Design 15, 2535–2549 (2009).

Jørgensen, K. N. et al. First- and second-generation antipsychotic drug treatment and subcortical brain morphology in schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 266, 451–460 (2016).

Szeszko, P. R. et al. White matter changes associated with antipsychotic treatment in first-episode psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 1324–1331 (2014).

Meng, L. et al. Widespread white-matter microstructure integrity reduction in first-episode schizophrenia patients after acute antipsychotic treatment. Schizophr. Res. 204, 238–244 (2019).

Zeng, B. et al. Abnormal white matter microstructure in drug-naive first episode schizophrenia patients before and after eight weeks of antipsychotic treatment. Schizophr. Res. 172, 1–8 (2016).

Fountoulakis, K. N. & Stahl, S. M. The effect of first- and second-generation antipsychotics on brain morphology in schizophrenia: a systematic review of longitudinal magnetic resonance studies with a randomized allocation to treatment arms. J. Psychopharmacol. 36, 428–438 (2022).

Leroux, E., Vandevelde, A., Tréhout, M. & Dollfus, S. Abnormalities of fronto-subcortical pathways in schizophrenia and the differential impacts of antipsychotic treatment: a DTI-based tractography study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 280, 22–29 (2018).

Zong, X. et al. Virtual histology of morphometric similarity network after risperidone monotherapy and imaging-epigenetic biomarkers for treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 80, 103406 (2023).

Ham, T., Leff, A., de Boissezon, X., Joffe, A. & Sharp, D. J. Cognitive control and the salience network: an investigation of error processing and effective connectivity. J. Neurosci. 33, 7091–7098 (2013).

Menon, V., Palaniyappan, L. & Supekar, K. Integrative brain network and salience models of psychopathology and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 94, 108–120 (2023).

Pessoa, L. A network model of the emotional brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 357–371 (2017).

Nejati, V., Majdi, R., Salehinejad, M. A. & Nitsche, M. A. The role of dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in the processing of emotional dimensions. Sci. Rep. 11, 1971 (2021).

Fischer, M., Kaech, S., Knutti, D. & Matus, A. Rapid actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Neuron 20, 847–854 (1998).

Matus, A. Postsynaptic actin and neuronal plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 9, 561–565 (1999).

Brünig, I., Kaech, S., Brinkhaus, H., Oertner, T. G. & Matus, A. Influx of extracellular calcium regulates actin-dependent morphological plasticity in dendritic spines. Neuropharmacology 47, 669–676 (2004).

Oertner, T. G. & Matus, A. Calcium regulation of actin dynamics in dendritic spines. Cell Calcium 37, 477–482 (2005).

Leveque, J. C. et al. Intracellular modulation of NMDA receptor function by antipsychotic drugs. J. Neurosci. 20, 4011–4020 (2000).

de la Fuente, H. et al. Synaptic clusters of MHC class II molecules induced on DCs by adhesion molecule-mediated initial T-cell scanning. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3314–3322 (2005).

Lebedeva, T. et al. Major histocompatibility complex class I-intercellular adhesion molecule-1 association on the surface of target cells: implications for antigen presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunology 113, 460–471 (2004).

Lebedeva, T., Dustin, M. L. & Sykulev, Y. ICAM-1 co-stimulates target cells to facilitate antigen presentation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17, 251–258 (2005).

Kuhn, S., Gritti, L., Crooks, D. & Dombrowski, Y. Oligodendrocytes in development, myelin generation and beyond. Cells 8, 1424 (2019).

Sofroniew, M. V. & Vinters, H. V. Astrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 119, 7–35 (2010).

Maynard, T. M., Sikich, L., Lieberman, J. A. & LaMantia, A. S. Neural development, cell-cell signaling, and the ‘two-hit’ hypothesis of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 27, 457–476 (2001).

Jones, P., Rodgers, B., Murray, R. & Marmot, M. Child development risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. Lancet 344, 1398–1402 (1994).

Cannon, M. et al. Evidence for early-childhood, pan-developmental impairment specific to schizophreniform disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 449–456 (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all participants for their time and contributions, which made this research possible. Funding. This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62373079), Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (2024ZYD0039), Health Commission of Sichuan Province(24CXTD11), Sichuan Medical Association (S23012), Chengdu Science and Technology Bureau (2022-YF05-01867-SN), Health Commission of Chengdu (2024141), CAS International Cooperation Research Program (153111KYSB20190004) and STI2030-Major Projects (2021ZD0202102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liju Liu: conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing-original draft. Mi Yang: supervision, investigation, resources, funding acquisition, writing—review & editing. Jinxing Chen: methodology, investigation, visualization. Chunchen Yi: methodology. Di Kong: supervision, formal analysis. Guocheng Zhao: formal analysis. Huafu Chen: supervision, writing—review & editing. Xiangyang Zhang: resources, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Yang, M., Chen, J. et al. Risperidone reduces individualized morphometric similarity deviation in schizophrenia and associates with cortical transcriptomic patterns. Schizophr 12, 19 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00724-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-025-00724-9