Abstract

Visceral adiposity is an important characteristic of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) that affects its development. Curcumin (Cur) attenuates MASH through microbial biotransformation. However, antibiotics (Abx) do not weaken but rather enhance the resistance to weight gain of Cur on MASH rats. The resistance to weight gain mechanism of Cur is different from its anti-MASH effect, which may relate to alleviate visceral adiposity. Here we investigated the mechanism of Cur against visceral adiposity in high-fat diet-induced MASH rats. The results demonstrated that Cur and Abx reduced body, liver and visceral fat weights of MASH rats. Unlike Abx, which induces resistance to weight gain by reducing appetite, Cur mainly reduced the weight of visceral fat, especially that of perirenal fat. Intriguingly, the reduction in perirenal fat caused by Cur was attributed to its specific inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) release. The Cur-induced decrease in intestinal GIP release inhibited the activation of GIP receptors to alleviate adipogenesis and inflammation in perirenal adipose tissue. Moreover, Cur alleviated intestinal epithelium and vascular barrier disruption-mediated hypoxia to inhibit GIP release. In summary, the pharmacological effects of Cur on visceral adiposity were mainly contributed by inhibiting gut barrier disruption-mediated hypoxia to attenuate GIP release.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Visceral adiposity is the abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat that poses health risks. High-carbohydrate, high-fat diets and insufficient exercise cause energy imbalance resulting in visceral adiposity1,2. In recent decades, visceral adiposity has surged globally among adults and children, become epidemic3, and has been accompanied by an increase in metabolic diseases such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)4,5. MASH is the malignant stage of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MAFLD) that is characterized by hepatocyte damage and inflammation6,7. This progressive process can lead to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and other complications8. Statistically, 65–90% of MASH patients that achieve remission experience weight loss of 7% or more9. It follows that weight loss, especially visceral fat reduction, is crucial for the treatment of MASH. Currently, lifestyle intervention is the primary approach for weight loss, but poor compliance makes it difficult for most patients to persevere10. Drug intervention is therefore necessary to help patients achieve their weight loss goals. Resmetirom is the only drug that has been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of MASH, but its long-term efficacy and safety are yet to be determined11. Orlistat (OST) is an orally available over-the-counter antiobesity medication approved by the FDA for chronic weight management12, however, resistance to orlistat has emerged, and this medication also causes renal dysfunction13. With the increasing number of obese individuals and the importance of preventing weight gain when treating metabolic disease, including MASH, new strategies for visceral adiposity treatment are urgently needed.

Visceral adiposity arises from excessive fat accumulation, with the gastrointestinal tract being key for fat absorption. The gastrointestinal tract acts as the primary site for food absorption, regulating food intake, and maintaining energy balance. The gastrointestinal tract serves as both the source and recipient of appetite signals and communicates with the brain and other energy homeostasis organs14. Food intake triggers physiological responses in the digestive system, including the release of gut hormones by intestinal endocrine cells involved in appetite signaling. Gut hormones play pivotal roles in the regulation of hunger and satiety. Visceral adiposity affects the expression of gut hormones and alters short-term diet-related signals. Gut hormone release is closely related to the intestinal barrier15. An improper diet increases intestinal permeability and facilitates increased nutrient passage, potentially due to the disruption of barrier function, especially impaired integrity of the intestinal vascular barrier16,17. The extensive vasculature in the gut makes barrier damage lead to reduced blood flow, inflammation, and tissue hypoxia18. Hypoxia-induced intestinal damage can induce the release of gut hormones to exacerbate lipogenesis19. Thus, inhibiting the release of gut hormones from hypoxia-damaged intestinal tissue is vital for visceral fat loss.

Curcumin (Cur) is derived primarily from the roots and rhizomes of the plant Curcuma longa L. and is its principal bioactive polyphenolic constituent20. Cur is commonly used as a food additive to enhance coloring and flavoring21. Cur has anti-inflammatory and lipid-lowering pharmacological effects22. Our previous research revealed that Cur exerts an anti-MASH effect through microbial biotransformation and that its efficacy is weakened by the action of antibiotics23. Intriguingly, the Cur-mediated resistance of MASH rats to weight gain cannot be counteracted by antibiotics, and its administering Cur in combination with antibiotics has a synergistic effect. These findings suggest that the mechanisms of the weight gain resistance and anti-MASH effects of Cur are different, suggesting the need for further study. Cur has been shown to regulate the release of gut hormones24 and protect the intestinal barrier25,26. Since inhibiting gut hormone release from hypoxia-damaged intestinal tissue is key to visceral fat loss, we investigated the mechanism by which Cur protects against visceral adiposity in high-fat diet-induced MASH rats.

Results

Coadministration of Cur and antibiotics further prevented weight gain in MASH rats

Liver tissues were stained with H&E and Oil red O to confirm the successful establishment of the MASH model27. The results of hepatic H&E staining revealed hepatocytes with obvious balloon-like lesions, irregular arrangements, and fat vacuoles of varying sizes in MASH rats (Fig. 1B). Compared with that of the Control group, the rats′ histological MAFLD activity score (RMAS) of the HFD group significantly (P < 0.01) increased. Compared with those in the Control group, the hepatocytes of the rats in the HFD group were filled with red lipid droplets accompanied by a significant (P < 0.01) increase in the red lipid droplet area after staining with Oil red O (Fig. 1C). Cur, Orlistat (OST) and Abx treatment alleviated the hepatic pathological changes caused by MASH and significantly (P < 0.05) reduced the RMAS and red lipid droplet areas. Further determination of the obesity phenotype in MASH was performed via H&E staining images of epididymal adipose tissues. The adipocytes and their spaces were significantly enlarged in the HFD group (Fig. 2A). The volume and diameter of adipocytes were significantly reduced in the Cur, OST and Abx groups, and the intercellular spaces were dense.

A Chemical structure of Cur. B H&E staining images of hepatic tissues (magnification 100×; scale bar = 100 μm) and histological MAFLD score in rats. C Oil red O staining images of hepatic tissues (magnification 100×; scale bar = 100 μm) and quantification of Oil red O staining. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ##P < 0.01, vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the HFD group.

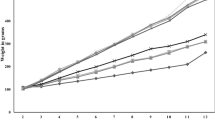

A Adipose tissue histopathology (magnification 100×, scale bar = 100 μm). B Body weight. C Food intake. D Abx solution intake. E Cumulative intake of Abx solution. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ##P < 0.01, vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the HFD group; &P < 0.05, vs. the Abx group.

Weight gain is the most common indicator of obesity. Compared with the control group, the HFD group presented a significant (P < 0.01) increase in body weight from the fourth week (Fig. 2B). However, the body weights of the rats in the Cur and OST groups were significantly (P < 0.05) lower than those in the HFD group beginning in the sixth week. Additionally, compared with the HFD group, both the Abx and Abx+Cur100 groups presented significant (P < 0.01) decreases in body weight after an aqueous Abx solution was consumed beginning in the ninth week. The resistance of the Abx+Cur100 group to weight gain was greater than that of the Cur100 group beginning at the tenth week, even though the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). Based on these findings, we conclude that curcumin and antibiotics synergistically mitigate HFD-induced weight gain in MASH rats.

Cur reduced GIP release, whereas antibiotics promoted the release of GLP-1 and CCK to decrease food intake in MASH rats

There were no significant differences in food intake among the groups fed the HFD. Food intake by the HFD-fed groups was lower than that of the Control group fed a normal diet, possibly because of the potential impacts on appetite caused by the high-fat content and caloric density of the HFD (Fig. 2C). Notably, the rats that drank the Abx solution consumed less food than did those in the other groups. There was no significant difference observed between the Abx solution consumption by the two groups from weeks nine to twelve (Fig. 2D). However, the cumulative intake of Abx solution was different between the two groups, with lower intake in the Abx+cur100 group than in the Abx group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2E). These findings further emphasized the role of curcumin in preventing weight gain in MASH rats.

Gut hormones play a vital role in the regulation of food intake28. Compared with those in the Control group, the serum levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and cholecystokinin (CCK) were significantly (P < 0.01) lower in the HFD group, whereas the serum levels of GIP and motilin (MLN) were significantly (P < 0.01) greater (Fig. 3A–D) After combined treatment with Abx and Cur, the serum levels of GLP-1 and CCK reduced by HFD feeding were increased significantly (P < 0.01), whereas the elevated serum levels of GIP and MLN induced by the HFD decreased significantly (P < 0.01). Moreover, the serum levels of GLP-1 and CCK were significantly (P < 0.01) greater and the serum MLN level was significantly lower (P < 0.01) in the Abx group than in the HFD group. Cur treatment significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the HFD-induced increase in the serum levels of GIP and MLN. Consistent with the serum GIP levels, the fluorescence intensity of GIP in the small intestine was significantly (P < 0.01) greater in the HFD group than in the Control group (Fig. 3E, F). Compared with that in the HFD group, the fluorescence intensity of GIP in the small intestine was significantly (P < 0.01) lower in the Abx+Cur100, Abx, Cur50 and Cur100 groups. These results suggest that, unlike antibiotics, Cur tends to reduce the release of GIP to prevent weight gain in MASH rats.

Serum levels of A GLP-1, B CCK, C GIP and D MLN. E Quantitative analysis of intestinal GIP immunofluorescence. F Representative immunofluorescence images of intestinal GIP expression (magnification 200×, scale bar = 50 μm). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). ##P < 0.01, vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the HFD group.

Cur prevented weight gain by decreasing perirenal adipose tissue production in MASH rats

Liver, epididymal and perirenal adipose tissues are closely related to obesity. We therefore analyzed their weights and indices to investigate the mechanism of weight gain in MASH rats. The liver, epididymal and perirenal adipose tissue weights and indices were significantly (P < 0.01) greater in the HFD group than in the Control group, except for the liver index (Fig. 4A–F). Compared with those in the HFD group, the weights of the livers and perirenal adipose tissues were lower (P < 0.05) in the Cur100 group. A dose of 50 mg/kg Cur significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the increase in perirenal adipose tissue weight caused by HFD feeding. In particular, the perirenal adipose tissue index was reduced (P < 0.05) in the Cur100 group. After combined treatment with Abx and 100 mg/kg Cur, the HFD-induced increases in the weights of the livers and perirenal adipose tissues were ameliorated. Additionally, the perirenal adipose tissue weights and indices were significantly (P < 0.01) lower in the OST group than in the HFD group. These results show that OST, Abx and Cur can reduce liver and adipose tissue weights, among which Cur can effectively reduce the production of perirenal adipose tissue.

A Liver weight (n = 6). B Epididymal adipose tissue weight (n = 6). C Perirenal adipose tissue weight (n = 6). D Liver index (n = 6). E Epididymal adipose tissue index (n = 6). F Perirenal adipose tissue index (n = 6). G TNF-α and H IL-1β levels in epididymal adipose tissue (n = 6). I Representative Western blot bands of SREBP-1c, PPAR-γ, CAV-1 and PLIN1. J Quantitative analysis of the Western blot band densities of SREBP-1c, PPAR-γ, CAV-1 and PLIN1 (n = 3). K Representative Western blot bands of GIPR. L Quantitative analysis of the Western blot band densities of GIPR (n = 3). The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the HFD group.

Cur reduced lipogenesis and inflammation in perirenal adipose tissue by inhibiting GIPR expression in MASH rats

Adipose inflammation is induced by fat production29. Since Cur mainly reduces the body weight of MASH rats by inhibiting perirenal fat production, inflammation and lipogenesis in perirenal adipose tissues were investigated. Compared with those in the Control group, the levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) were significantly (P < 0.01) increased in the HFD group (Fig. 4G, H). Cur treatment significantly (P < 0.05) decreased the elevated levels of TNF-α and IL-1β caused by the HFD, except for in the 50 mg/kg Cur treatment group, in which the TNF-α level was not significantly different (P > 0.05). Moreover, in contrast with those in the Control group, the expression of adipogenesis-related proteins, including sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1c, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ and caveolin-1 (CAV-1), increased (P < 0.05) in the HFD group, whereas perilipin 1 (PLIN1) expression was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased (Fig. 4I, J). Treatment with 100 mg/kg Cur significantly (P < 0.05) attenuated the upregulation of SREBP-1c, PPAR-γ and CAV-1 induced by the HFD and restored the decrease in PLIN1 protein expression. Moreover, the expression levels of PPAR-γ and CAV-1 were significantly (P < 0.05) lower in the Cur50 group than in the HFD group.

Cur affects obesity in MASH rats by regulating the release of small intestinal GIP. The released GIP may activate the GIP receptor (GIPR) in perirenal adipose tissue to promote adipogenesis, thus, the expression of GIPR was investigated. Compared with that in the Control group, GIPR expression was significantly (P < 0.01) increased in the HFD group (Fig. 4K, L). However, 100 mg/kg Cur dramatically (P < 0.05) ameliorated the increase in GIPR expression caused by the HFD. Accordingly, we concluded that Cur reduces GIP production to inhibit GIPR activation and thus reduces adipogenesis and inflammation in perirenal adipose tissue.

Cur reduced GIP release by alleviating hypoxic injury in the small intestines of MASH rats

The release of GIP is associated with the hypoxic conditions of intestinal tissue30,31. Compared with those in the Control group, the integrated optical density (IOD) of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) were significantly (P < 0.01) elevated in the HFD group (Fig. 5A–D). However, the IODs of HIF-1α and HIF-2α were significantly (P < 0.01) lower in the Cur50, Cur100, Abx and Abx+Cur100 groups than in the HFD group. Moreover, there was a strong correlation (|r|>0.9, P < 0.01) between small intestinal GIP production and the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α (Fig. 5E, F). These results indicate that Cur suppresses the secretion of hypoxic factors, thereby mitigating hypoxia-induced damage to reduce GIP generation in the small intestine.

A IHC staining images of HIF-1α in the small intestine (magnification, 200×; scale bar = 50 μm). B IOD of small intestinal HIF-1α expression. C IHC staining images of HIF-2α in the small intestine (magnification 200×; scale bar = 50 μm). D IOD of small intestinal HIF-2α expression. E Spearman correlation between HIF-1α and GIP production. F Spearman correlation between HIF-2α and GIP production. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 6). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the HFD group.

Cur attenuated hypoxia by protecting the epithelial and vascular barriers of the small intestine in MASH rats

Intestinal hypoxia is often caused by disruption of the intestinal epithelial and vascular barriers32. In the HFD group, the structure of the small intestines was damaged with sparsely arranged and detached intestinal villi and glands and inflammatory infiltration in the mucosal layer (Fig. 6A). Compared with that of the Control group, the histological score of the HFD group was significantly (P < 0.01) greater (Fig. 6B). Compared with the HFD group, the Cur treatment groups presented closely arranged intestinal villi and glands without noticeable inflammatory infiltration, resulting in a significant (P < 0.01) decrease in the histopathology score.

A H&E staining images of the small intestine (magnification 100×; scale bar = 100 μm). B Histopathological scores of the small intestine were determined from the H&E staining images (n = 6). C Occludin and D ZO-1 mRNA expression in the small intestine (n = 3). E Representative Western blot bands of VE-cadherin, Integrin-β1, Talin, and PV-1. F Quantitative analysis of the Western blot band densities of VE-cadherin, Integrin-β1, Talin, and PV-1 (n = 3). G Spearman analysis of the relationships among intestinal barrier proteins (ZO-1, Occludin, VE-cadherin, Integrin-β1, Talin, and PV-1) and HIFs (HIF-1α and HIF-2α) presented as a heatmap. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. the control group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. the HFD group.

Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) and Occludin are important tight junction proteins in the intestinal epithelial barrier33. Compared with those in the control group, the small intestinal mRNA expression levels of ZO-1 and Occludin were significantly (P < 0.01) lower in the HFD group (Fig. 6C, D). Cur treatment significantly (P < 0.01) increased the reductions in ZO-1 and Occludin mRNA expression caused by the HFD. Additionally, the mRNA expression of Occludin was significantly (P < 0.05) elevated in the Abx+Cur100 group compared with the HFD group. In addition, VE-cadherin, Integrin-β1, Talin-1 and PV-1 are important vascular barrier-related proteins. Compared with those in the Control group, VE-cadherin, Integrin-β1, and Talin-1 expression in the small intestine of HFD-fed rats significantly (P < 0.05) decreased, whereas PV-1 expression significantly (P < 0.01) increased (Fig. 6E, F). Conversely, Cur treatment significantly (P < 0.05) increased the expression of VE-cadherin, Integrin-β1, and Talin-1 reduced by HFD feeding and decreased the PV-1 expression, except for the effect of 50 mg/kg Cur on Integrin-β1 expression, which was not significantly different. In addition, the expression of Integrin-β1 and PV-1 was lower (P < 0.05) in the Abx+Cur100 group than in the HFD group. Abx treatment significantly (P < 0.01) decreased only the increase in PV-1 expression caused by the HFD. Correlation analysis (Fig. 6G) revealed that the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α (|r| >0.6, P < 0.01) was significantly correlated with the mRNA expression of ZO-1 and Occludin and the protein expression of PV-1. These findings show that Cur protects the intestinal epithelial and vascular barriers to alleviate intestinal hypoxia damage.

Discussion

In this study, curcumin (Cur) was first revealed to have a protective effect against visceral adiposity, which was achieved through a mechanism different from that of its anti-MASH effect. Cur prevented weight gain by decreasing the perirenal adipose tissue index by inhibiting gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) release. Inhibiting GIP release further alleviated lipogenesis and inflammation in perirenal adipose tissue. Moreover, Cur attenuated small intestinal hypoxia to reduce GIP release by protecting the epithelial and vascular barriers. These findings provide strong evidence that Cur alleviates visceral adiposity by inhibiting GIP release caused by hypoxia-induced intestinal damage in MASH rats.

On the basis of previous studies and preliminary experiments, 50 and 100 mg/kg Cur were used in the present study, corresponding to human equivalent doses of 8.36 and 16.72 mg/kg, respectively. Research has shown that ingesting 8.33 mg/kg Cur for 8 weeks can reduce hepatic lipid levels in MAFLD patients34. Although this dose exceeds the safe range of 3 mg/kg recommended by the World Health Organization, animal experiments have shown that the oral LD50 of Cur, which is considered a nontoxic substance, is greater than 2000 mg/kg in rats. Moreover, no significant side effects were observed when high doses, such as 8–12 g/day, were administered in short-term human trials, but perennial and excessive use of Cur can irritate the gastrointestinal tract and cause allergic reactions35. The potential side effects of perennial and excessive Cur administration deserve further investigation in future studies. Numerous studies on metabolic diseases in rats have shown that the Cur safe dosage range is 40–100 mg/kg36,37. The dosage selected in the present study is consistent with these studies, and no adverse reactions were observed in the rats treated with Cur. These findings indicate that the dosage of Cur used in this study is safe and reasonable. The main dietary sources of Cur are turmeric powder and curry. However, it is not feasible to consume an effective dosage of Cur through the diet, as approximately 32.3 g of turmeric powder or 172 g of curry powder would need to be consumed daily. Thus, Cur should be administered as a supplement. In this study, to assess Cur’s effect on reducing visceral fat, Orestat (OST) was included in the study group as a positive control. OST, an oral over-the-counter anti-obesity drug12, serves as a reference to better evaluate Cur’s impact on visceral fat. Inhibiting gut hormones release from hypoxic intestinal damage is key to visceral fat loss, and Cur has been shown to regulate the release of gut hormones and protect the intestinal barrier24,25,26. Thus, we investigate the mechanism of Cur against visceral adiposity from this perspective. OST induces weight loss by inhibiting lipase in the stomach, small intestine, and pancreatic mucus. This prevents triglycerides from being broken down into fatty acids and absorbed in the intestine38,39, a mechanism distinct from that of Cur. Therefore, in the study of Cur’s anti-visceral fat mechanism, we did not establish an OST group. Further consideration reveals that in future experiments, positive control drugs should be included in the study group to improve the comprehensiveness of the research, which may lead to more important findings, such as discovering new mechanisms of positive control drugs.

In our prior study, Cur improved liver injury and lipid accumulation in MASH rats via microbial biotransformation, which was inhibited by Abx23. Intriguingly, compared with the administration of Cur alone, the administration of 100 mg/kg Cur with Abx solution significantly reduced weight gain from week 9 until the end of the experiment. Abx did not inhibit the Cur-mediated prevention of weight gain in MASH rats but had a synergistic effect. Moreover, the prevention of weight gain by Cur in MASH rats differs from its anti-MASH effect.

In the development of MASH-related visceral adiposity, dysregulated fatty acid intake and metabolism contribute to hepatic lipid accumulation, whereas insulin resistance in adipose tissue promotes lipolysis and the subsequent release of free fatty acids into the liver40,41. This exacerbates fat deposition in hepatocytes and worsens MASH symptoms42,43. In addition to its effects on the liver, MASH-associated visceral adiposity induces systemic insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disorders44,45. Thus, treating visceral adiposity in MASH is crucial.

Currently, visceral adiposity results mainly from overeating, which is driven by a gut hormone-mediated increase in appetite. Gut hormones are vital in the treatment of visceral adiposity and weight homeostasis disorders46. GIP is an incretin released from intestinal endocrine K cells that enhances appetite and food intake. GLP-1, a potent food intake inhibitor, controls both food intake and energy absorption with GIP26. CCK can reduce the quantity and timing of food intake47, whereas MLN maintains gastrointestinal function and transmits hunger signals48. The secretion of these gut hormones, which interact with each other, has been linked to visceral adiposity. Interestingly, our study revealed that the combined administration of Abx and Cur normalized intestinal hormone levels in rats with MASH-related visceral adiposity. Abx treatment alone affected the release of gastrointestinal hormones to impact rat appetite and reduce body weight. Cur alone regulated gastrointestinal hormone release, but its effects were inferior to those of the Abx, except on GIP. The significant effect of Cur on reducing GIP release confirmed the distinct mechanisms of Cur and Abx underlying weight gain resistance.

GIP is mainly secreted by K cells on intestinal villi49, but the immunohistochemical staining results of GIP in the rat intestine in this study showed that GIP staining seemed to extend to a wider area than expected for K cell secretion (Fig. 3E). The changes in K cell count and GIP staining range under high-fat diet conditions may be attributed to the activation of non-K cell GIP secretion potential. A high-fat diet might prompt other cell types to secrete GIP by modulating the molecular expression patterns of intestinal endocrine cells, such as through the regulatory effect of KCNH2 potassium channels. KCNH2 is expressed in various intestinal endocrine cells, including K cells, L cells, and Paneth cells. Recent research shows that KCNH2 knockout mice have higher GIP secretion levels on high-fat diets, indicating that non-K cells may release GIP via this channel50. Thus, under high-fat diet conditions, non-K cells may exhibit functional overlap or plasticity, leading to GIP secretion. This may be the reason for the expanded secretion range of GIP after consuming HFD. Further experimental confirmation is needed, which is a key focus of our future research.

In the presence of high levels of sugar and fat, GIP secretion increases to promote adipogenesis and inflammation51. GIPR is a direct GIP receptor that is present in adipose tissue. In GIPR gene knockout mice, the adipocyte count decreases despite high-fat diet feeding52. Antagonizing GIPR attenuates lipid accumulation in the liver, muscle and adipose tissue46. Elevated GIP levels stimulate GIPR to increase inflammatory cytokine secretion in perirenal adipose tissue53, which alters the expression of adipogenesis-related proteins. Once activated, PPAR-γ increases SREBP-1c transcription to promote the conversion of pyruvate to fatty acids20,54. Additionally, increased PLIN1 expression promotes lipolysis53, whereas increased CAV-1 expression exacerbates fat inflammation55. In our study, Cur reduced the body, liver, and adipose tissue weights and the related indices, especially the perirenal fat coefficient, in MASH rats. By inhibiting GIP release, Cur antagonizes GIPR in adipose tissue to inhibit the expression of lipid-related proteins and the release of inflammatory factors, thus attenuating adipogenesis and inflammation. Cur alone was more effective than antibiotics in reducing GIP release and alleviating adipogenesis and inflammation in perirenal adipose tissue.

GIP release is correlated with intestinal tissue hypoxia and is regulated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), including HIF-1α and HIF-2α56. In the MASH state, intestinal hypoxia exacerbation is accompanied by a significant increase in the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α19,57. The results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies. Moreover, Cur treatment significantly attenuated MASH-induced intestinal hypoxia. Hypoxia is common in inflammatory microenvironment58 and results from intestinal barrier disruption with epithelial and vascular barrier destabilization59. Intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction is associated with altered expression of tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and Occludin16, which are crucial for maintaining the integrity and permeability of the intestinal epithelium60. Such dysfunction can impact the intestinal vascular barrier, which regulates substance transport from the intestinal lumen to the systemic circulation61. PV-1 regulates endothelial homeostasis and permeability, and its expression is increased in patients with an impaired intestinal vascular barrier. Endothelial Talin1, which stabilizes the vascular system, is vital for intestinal microvessel maintenance62,63. Previous studies have shown that Cur not only attenuates endothelial dysfunction64 but also protects the intestinal vascular barrier through its effects on vascular endothelial cells65. Consistent with these studies, our findings demonstrated that Cur restored the expression of tight junction and intestinal vascular barrier-related proteins to improve intestinal barrier function in MASH rats, thereby reducing GIP generation caused by intestinal hypoxia damage, and ultimately inhibiting GIPR-mediated lipogenesis and inflammation.

Currently, studies on the development and application of GIP antagonists and their receptor GIPR are limited. Notably, GLP-1, another gastrointestinal hormone, plays an important role in weight gain resistance. GLP-1 is a therapeutic target for obesity and type 2 diabetes66, and agonists of its receptor have entered clinical trials for the prevention of weight gain and treatment of metabolic diseases. GLP-1 receptor agonists have also been used to alleviate MASH but do not improve fibrosis. While GIP enhances appetite, GLP-1 suppresses appetite; thus, these factors exert complementary effects on appetite regulation, energy expenditure, and glucose metabolism67. Furthermore, the development of GLP-1/GIP dual agonists further highlights the important role of GIP in weight gain resistance. The findings of this study on the therapeutic effect of Cur on MASH-related visceral adiposity, which is mediated via GIP, provide scientific evidence that GIP is a therapeutic target for obesity and other metabolic diseases; however, further clinical research is needed for confirmation.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

Curcumin (Cur, purity ≥98%, CID: 969516, Fig. 1A) and orlistat (OST, purity ≥98%, Lot#: O830939) were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Metronidazole (Lot#: M109874), vancomycin (Lot#: V301569), ampicillin (Lot#: A102048) and neomycin sulfate (Lot#: N109017) were purchased from Aladdin Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The antibiotic (Abx) solution was composed of vancomycin (0.25 g/L), neomycin sulfate (0.5 g/L), metronidazole (0.5 g/L), and ampicillin (0.5 g/L). The high-fat diet (HFD, consisting of 20% carbohydrates, 20% protein, and 60% fat, 7 kcal/g, Lot#: D12492) was acquired from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Foshan, China) (Supplementary Table 1). SREBP-1c (Lot#: AF4728), PPARγ (Lot#: AF4728), β-actin (Lot#: AF4728), PV-1 (Lot#: DF13415), Integrin-β1 (Affinity, Lot#: AF5739), GIPR (Lot#: DF5176), CAV-1 (Lot#: AF6386), VE-cadherin (Lot#: AF6265), HIF-1α (Lot#: AF1009) and HIF-2α (Lot#: DF2928) were purchased from Affinity Biosciences (OH, USA). PLIN1 (Lot#: ab172907) and Talin (Lot#: ab11188) were acquired from Abcam Co., Ltd. (Cambridge, United Kingdom). GIP (Lot#: A6230) was purchased from ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Hematoxylin staining solution (Lot#: H913272) and eosin staining solution (Lot#: E775932) were obtained from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Oil red O staining solution (Lot#: G1015) and DAPI staining solution (Lot#: G1012) were purchased from Servicebio Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). All chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and endotoxin-free.

Animals and treatments

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (160–180 g, No. 44005900002746) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (Guangzhou, China). All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (No. 20200723001) and performed according to the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments and the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals in China. The rats were housed in an environment at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C with a humidity of 50 ± 10% and a 12-h light-dark cycle. After one week of adaptive feeding, the rats were randomly divided into seven groups (n = 6) : (1) Control group (fed a normal diet); (2) HFD group (fed a high-fat diet); (3) Abx + Cur100 group (fed a HFD, treated with 100 mg/kg Cur per day, and supplied water with Abx); (4) Abx group (fed a HFD and supplied water with Abx)); (5) Cur50 group (fed a HFD and treated with 50 mg/kg Cur per day); (6) Cur100 group (fed a HFD and treated with 100 mg/kg Cur per day); and (7) OST group (fed a HFD and treated with 10 mg/kg OST per day). All of the rats, except those in the control group, were fed a high-fat diet daily for 12 weeks. Moreover, the Abx + Cur 100 group, Cur 50 group and Cur 100 group were orally administered the appropriate amounts of curcumin, while the other groups were orally administered saline. The material was intragastrically administered once a day for 12 weeks. Moreover, all the rats were allowed to drink purified water without antibiotics from weeks 1 to 8. From weeks 9 to 12, the Abx group and Abx + Cur 100 group were given purified water containing antibiotics, whereas the other groups continued to drink purified water without antibiotics. At the end of the experiment, rats were euthanized by asphyxiation in a vessel filled with carbon dioxide. The rats were euthanized after blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta, and their small intestines, livers, epididymal adipose tissues and perirenal adipose were collected and weighed for further analyses. The following indices were calculated: 68

Histopathological analysis

Paraffin sections of epididymal adipose tissues, small intestines and livers were stained with hematoxylin-eosin for histopathological analysis. Hepatic and small intestinal pathological evaluations were conducted using a previously reported scoring system (Tables 1 and 2)69,70. In addition, frozen hepatic slices were stained with Oil red O. Subsequently, a hematoxylin staining solution was used to stain the cell nuclei blue to facilitate cell observation. The accumulation of lipid droplets in the sections was analyzed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software. All stained sections were checked with 5 microscopic fields each.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The perirenal adipose levels of TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as the serum levels of GIP, MLN, CCK, and GLP-1, were detected using ELISA kits (Mlbio, Shanghai, China).

GIP immunofluorescence analysis

Paraffin sections of the small intestine were dewaxed, and antigen retrieval was performed. These sections were subsequently incubated with primary (GIP, 1:200) and secondary antibodies. DAPI was used to stain the nuclei, followed by the addition of a fluorescence quenching reagent and section sealing. The sections were visualized using a fluorescence microscope and analyzed using ImageJ software.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of HIF-1α and HIF-2α

Paraffin sections of the small intestines were dewaxed, and antigen retrieval was performed. These sections were incubated with the corresponding primary (HIF-1α, 1:500; and HIF-2α, 1:400) and secondary antibodies. After staining with hematoxylin, the sections were dehydrated and sealed. The sections were observed and photographed under a microscope before quantitative analysis using ImageJ software to determine the integrated optical density (IOD).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA from the small intestines was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Thermo, MA, USA). The extracted total RNA was subsequently reverse-transcribed into cDNA using cDNA reverse transcription reagent (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The mRNA expression levels of ZO-1, Occludin and β-actin were measured using a ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The primer sequences of the target genes are shown in Table 3. β-actin was used as the internal reference gene, and relative gene expression was calculated via the 2-ΔΔCt method.

Western blot analysis

Total protein from the small intestine was extracted with RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors and quantified with a BCA protein assay kit following the manufacturer’s instructions (BestBio Science, Shanghai, China). The protein samples were separated by SDS‒PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were subsequently blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk in TBST and incubated with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. The protein bands were detected using an ECL Advanced kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Shanghai, China). β-Actin served as an internal reference to verify equal loading of the samples. The working dilutions of the primary antibodies were as follows: SREBP-1c, PPARγ, β-actin, PLIN1, PV-1, Talin, Integrin-β1 and GIPR were diluted 1:2000, while CAV-1 and VE-cadherin were diluted 1:1000.

Statistical analysis

All the data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and were statistically analyzed using SPSS software 26.0. If the data exhibited a normal distribution, intragroup differences were analyzed via one-way ANOVA. The Bonferroni method was used when the variances were homogeneous; otherwise, Dunnett’s T3 method was applied. Two groups were analyzed by Student’s t test. If the data were not normally distributed, the nonparametric Kruskal‒Wallis H test was used to analyze the differences. P < 0.05 indicated a statistical significance. Spearman correlations were calculated to analyze the associations between the indices.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Chooi, Y. C., Ding, C. & Magkos, F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism 92, 6–10 (2019).

Stranahan, A. M. Visceral adiposity, inflammation, and hippocampal function in obesity. Neuropharmacology 205, 108920 (2022).

Huang, W. et al. Octreotide promotes weight loss via suppression of intestinal MTP and apoB48 expression in diet-induced obesity rats. Nutrition 29, 1259–1265 (2013).

Akbari, M. et al. The effects of curcumin on weight loss among patients with metabolic syndrome and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Pharm. 10, 649 (2019).

Bansal, S. K. & Bansal, M. B. Pathogenesis of MASLD and MASH – role of insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Alimentary Pharmacol. Therapeutics 59, S10–S22 (2024).

Piras, C. et al. Contribution of metabolomics to the understanding of NAFLD and NASH syndromes: a systematic review. Metabolites 11, 694 (2021).

Zhang, T., Nie, Y. & Wang, J. The emerging significance of mitochondrial targeted strategies in NAFLD treatment. Life Sci. 329, 121943 (2023).

Anstee, Q. M., Reeves, H. L., Kotsiliti, E., Govaere, O. & Heikenwalder, M. From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 411–428 (2019).

Polyzos, S. A., Kountouras, J. & Mantzoros, C. S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism 92, 82–97 (2019).

Pucci, A. & Batterham, R. L. Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different. J. Endocrinol. Invest 42, 117–128 (2019).

Lazarus, J. V. et al. Opportunities and challenges following approval of resmetirom for MASH liver disease. Nat. Med. 30, 3402–3405 (2024).

Jin, J. et al. Orlistat and ezetimibe could differently alleviate the high-fat diet-induced obesity phenotype by modulating the gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 13, 908327 (2022).

Tak, Y. J. & Lee, S. Y. Anti-obesity drugs: long-term efficacy and safety: an updated review. World J. Mens. Health 39, 208–221 (2021).

Acosta, A. et al. Quantitative gastrointestinal and psychological traits associated with obesity and response to weight-loss therapy. Gastroenterology 148, 537–546 e534 (2015).

Farhadipour, M. & Depoortere, I. The function of gastrointestinal hormones in obesity-implications for the regulation of energy intake. Nutrients 13, 1839 (2021).

Teixeira, T. F., Collado, M. C., Ferreira, C. L., Bressan, J. & Peluzio Mdo, C. Potential mechanisms for the emerging link between obesity and increased intestinal permeability. Nutr. Res. 32, 637–647 (2012).

Jiang, B. et al. Advances in the interaction between food-derived nanoparticles and the intestinal barrier. J. Agric. Food Chem. 72, 3291–3301 (2024).

Shao, T. et al. Intestinal HIF-1alpha deletion exacerbates alcoholic liver disease by inducing intestinal dysbiosis and barrier dysfunction. J. Hepatol. 69, 886–895 (2018).

Chen, S., Okahara, F., Osaki, N. & Shimotoyodome, A. Increased GIP signaling induces adipose inflammation via a HIF-1alpha-dependent pathway and impairs insulin sensitivity in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 308, E414–E425 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. PPAR-γ signaling in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Pharmacol. Therapeutics 245, 108391 (2023).

Tsuda, T. Curcumin as a functional food-derived factor: degradation products, metabolites, bioactivity, and future perspectives. Food Funct. 9, 705–714 (2018).

Du, S. et al. Curcumin alleviates hepatic steatosis by improving mitochondrial function in postnatal overfed rats and fatty L02 cells through the SIRT3 pathway. Food Funct. 13, 2155–2171 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Curcumin alleviates high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis via improving hepatic endothelial function with microbial biotransformation in rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 71, 10338–10348 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Oral curcumin has anti-arthritic efficacy through somatostatin generation via cAMP/PKA and Ca(2+)/CaMKII signaling pathways in the small intestine. Pharm. Res. 95-96, 71–81 (2015).

Cao, S. et al. Curcumin ameliorates oxidative stress-induced intestinal barrier injury and mitochondrial damage by promoting Parkin dependent mitophagy through AMPK-TFEB signal pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 147, 8–22 (2020).

Drucker, D. J. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of glucagon-like peptide-1. Cell Metab. 27, 740–756 (2018).

Nie, K. et al. Diosgenin attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes through regulating SIRT6-related fatty acid uptake. Phytomedicine 111, 154661 (2023).

Hu, X. et al. A gut-derived hormone regulates cholesterol metabolism. Cell 187, 1685–1700.e1618 (2024).

Kolb, H. Obese visceral fat tissue inflammation: from protective to detrimental? BMC Med. 20, 494 (2022).

Yamane, S. & Harada, N. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide signaling in adipose tissue. J. Diabetes Investig. 10, 3–5 (2019).

Zhang, Q. et al. The glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) regulates body weight and food intake via CNS-GIPR signaling. Cell Metab. 33, 833–844.e835 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Melatonin attenuates chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in mice. Microbiological Res. 276, 127480 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. A Novel Role of SLC26A3 in the Maintenance of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Integrity. Gastroenterology 160, 1240–1255.e1243 (2021).

Kunnumakkara, A. B. et al. Role of turmeric and curcumin in prevention and treatment of chronic diseases: lessons learned from clinical trials. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 6, 447–518 (2023).

Peng, Y. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin in the inflammatory diseases: status, limitations and countermeasures. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 15, 4503–4525 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Curcumin attenuates collagen-induced rat arthritis via anti-inflammatory and apoptotic effects. Int. Immunopharmacol. 72, 292–300 (2019).

Fan, C. et al. Neuroprotective effects of curcumin on IL-1β-induced neuronal apoptosis and depression-like behaviors caused by chronic stress in rats. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12, 516 (2019).

Tak, Y. J. & Lee, S. Y. Long-term efficacy and safety of anti-obesity treatment: where do we stand?. Curr. Obes. Rep. 10, 14–30 (2021).

Son, J. W. & Kim, S. Comprehensive review of current and upcoming anti-obesity drugs. Diabetes Metab. J. 44, 802–818 (2020).

da Cruz, N. S., Pasquarelli-do-Nascimento, G., ACP, E. O. & Magalhaes, K. G. Inflammasome-mediated cytokines: a key connection between obesity-associated NASH and liver cancer progression. Biomedicines 10, 2344 (2022).

Salvoza, N. et al. The potential role of omentin-1 in obesity-related metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: evidence from translational studies. J. Transl. Med. 21, 906 (2023).

Navik, U., Sheth, V. G., Sharma, N. & Tikoo, K. L-Methionine supplementation attenuates high-fat fructose diet-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by modulating lipid metabolism, fibrosis, and inflammation in rats. Food Funct. 13, 4941–4953 (2022).

Kawaguchi, T. & Torimura, T. Is metabolic syndrome responsible for the progression from NAFLD to NASH in non-obese patients?. J. Gastroenterol. 55, 363–364 (2020).

Gutierrez-Cuevas, J., Santos, A. & Armendariz-Borunda, J. Pathophysiological molecular mechanisms of obesity: a link between MAFLD and NASH with cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 11629 (2021).

Wang, Y., Zheng, J., Long, Y., Wu, W. & Zhu, Y. Direct degradation and stabilization of proteins: new horizons in treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 220, 115989 (2024).

Ionut, V., Burch, M., Youdim, A. & Bergman, R. N. Gastrointestinal hormones and bariatric surgery-induced weight loss. Obesity21, 1093–1103 (2013).

Duca, F. A., Sakar, Y. & Covasa, M. The modulatory role of high fat feeding on gastrointestinal signals in obesity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 24, 1663–1677 (2013).

Kitazawa, T. & Kaiya, H. Motilin comparative study: structure, distribution, receptors, and gastrointestinal motility. Front. Endocrinol.12, 700884 (2021).

Lewis, J. E. et al. Stimulating intestinal GIP release reduces food intake and body weight in mice. Molecular Metabolism 84 (2024).

Yuan, Y.-C. et al. Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2 (KCNH2) is a promising target for incretin secretagogue therapies. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 9 (2024).

Holst, J. J. & Rosenkilde, M. M. Recent advances of GIP and future horizons. Peptides 125, 170230 (2020).

Vincent, R. P., Ashrafian, H. & le Roux, C. W. Mechanisms of disease: the role of gastrointestinal hormones in appetite and obesity. Nat. Clin. Pr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 268–277 (2008).

Miranda, C. S. et al. PPAR-alpha activation counters brown adipose tissue whitening: a comparative study between high-fat- and high-fructose-fed mice. Nutrition 78, 110791 (2020).

Pan, M. H. et al. Attenuation by tetrahydrocurcumin of adiposity and hepatic steatosis in mice with high-fat-diet-induced obesity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 12685–12695 (2018).

Al Madhoun, A. et al. Adipose tissue caveolin-1 upregulation in obesity involves TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB mediated signaling. Cells 12, 1019 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. HIF-1alpha: A potential therapeutic opportunity in renal fibrosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 387, 110808 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Hypoxia exacerbates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease via the HIF-2alpha/PPARalpha pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 317, E710–E722 (2019).

Taylor, C. T. & Scholz, C. C. The effect of HIF on metabolism and immunity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 573–587 (2022).

Lee, T. C., Huang, Y. C., Lu, Y. Z., Yeh, Y. C. & Yu, L. C. Hypoxia-induced intestinal barrier changes in balloon-assisted enteroscopy. J. Physiol. 596, 3411–3424 (2018).

Kuo, W. T., Odenwald, M. A., Turner, J. R. & Zuo, L. Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1514, 21–33 (2022).

Brescia, P. & Rescigno, M. The gut vascular barrier: a new player in the gut-liver-brain axis. Trends Mol. Med. 27, 844–855 (2021).

Pulous, F. E., Grimsley-Myers, C. M., Kansal, S., Kowalczyk, A. P. & Petrich, B. G. Talin-dependent integrin activation regulates VE-cadherin localization and endothelial cell barrier function. Circ. Res. 124, 891–903 (2019).

Giannotta, M., Trani, M. & Dejana, E. VE-cadherin and endothelial adherens junctions: active guardians of vascular integrity. Dev. Cell 26, 441–454 (2013).

Zhang, Z. B. et al. Curcumin’s metabolites, tetrahydrocurcumin and octahydrocurcumin, possess superior anti-inflammatory effects in vivo through suppression of TAK1-NF-kappaB pathway. Front. Pharm. 9, 1181 (2018).

Arogbokun, O., Sattarova, V. & Abel, A. S. Transient visual obscurations: a unique presentation of multiple myeloma. Ophthalmology 131, p854 (2023).

Mahapatra, M. K., Karuppasamy, M. & Sahoo, B. M. Therapeutic potential of semaglutide, a newer GLP-1 receptor agonist, in abating obesity, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and neurodegenerative diseases: a narrative review. Pharm. Res. 39, 1233–1248 (2022).

Alexiadou, K. & Tan, T. M. Gastrointestinal peptides as therapeutic targets to mitigate obesity and metabolic syndrome. Curr. Diab Rep. 20, 26 (2020).

Milić, S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity: Biochemical, metabolic and clinical presentations. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 9330–9337 (2014).

Liang, W. et al. Establishment of a general NAFLD scoring system for rodent models and comparison to human liver pathology. PLoS One 9, e115922 (2014).

Takenaka, K. et al. Correlation of the endoscopic and magnetic resonance scoring systems in the deep small intestine in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21, 1832–1838 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (82104472), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515011014), Cultivation project of Dongguan Institute of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (2023PY0202), Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (2024A04J10027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yingyi Liao: Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing, Data curation, Validation. Xingyu Xie: Validation, Investigation and Formal analysis. Zixin Lin: Formal analysis, Investigation. Ning Huang: Investigation. Guilan Wei: Investigation. Jiazhen Wu: Formal analysis. Yucui Li: Writing–review & editing. Jiannan Chen: Writing–review & editing. Ziren Su: Writing–review & editing. Xiuting Yu: Funding acquisition. Liping C¬hen: Writing–review & editing and Project administration. Yuhong Liu: Writing–review & editing, Project administration and funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, Y., Xie, X., Lin, Z. et al. Curcumin alleviates visceral adiposity via inhibiting GIP release from hypoxic intestinal damage in MASH rats. npj Sci Food 9, 99 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00466-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00466-z