Abstract

Infants born to HBsAg/HBeAg-positive mothers remain risk for hepatitis B virus vaccine breakthrough infection (VBI). In this multicenter prospective cohort study, we assessed whether increased neonatal vaccine dose (20 μg vs. 10 μg) or booster immunization could reduce VBI among these children. Infants were vaccinated after birth and followed up to age 5. The 20 μg non-booster group sustained higher anti-HBs levels and lower seronegative rates at all follow-ups compared to the 10 μg non-booster group. Booster immunization increased antibody levels in both dose groups. By age 5, VBI incidence was highest in the 10 μg non-booster group, whereas all overt/occult infections occurred among non-booster children. Multivariate analysis suggested that both higher neonatal dose and booster immunization were associated with a reduced VBI risk, with the lowest risk observed when both strategies were combined. These findings suggest that increased neonatal vaccine dose and booster immunization may help sustain anti-HBs and reduce VBI in high-risk population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains a critical global health burden. In 2022, an estimated 254 million people were infected with HBV worldwide, with 1.1 million deaths primarily attributed to HBV-related cirrhosis and liver cancer1. The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a global strategy aimed at eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 20302. Mother-to-child transmission represents a major route of HBV infection. Vaccination against HBV, administered starting at birth is the primary preventive measure recommended by the WHO3.

The successful implementation of China’s HBV vaccination program serves as a notable example in HBV prevention. Since 1992, HBV vaccination has been implemented in newborns in China, and in 2002, it was included in the national childhood immunization schedule4. Prior to the program’s implementation, China ranked among the highest HBV-prevalence countries globally. Notable reductions in HBV prevalence have been documented through program implementation. The prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the general population decreased significantly from 9.75% in 1992 to 5.86% in 2020, whereas a dramatic decline from 9.7% to 0.3% was observed in children under 5 years of age5.

However, concerns persist regarding the long-term protective efficacy of the Hepatitis B vaccine (HB vaccine). Long-term follow-up studies in adults vaccinated during adulthood have demonstrated a gradual decline in hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) levels while immune memory is retained6,7. However, the immune response following infant immunization differs. Following birth-dose vaccination, seroprotective anti-HBs levels decline more rapidly in young children compared to adults8. Studies have indicated that a subset of vaccinated children fails to sustain adequate long-term anti-HBs levels, raising concerns about potential loss of immunological memory against HBsAg9,10. As anti-HBs levels wane, particularly when falling below protective thresholds, the risk of vaccine breakthrough infection (VBI) increases. This risk is particularly increased in children born to HBsAg-positive mothers, especially those co-positive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)11. Early-life maternal-child exposure may occur when protective antibody levels are insufficient, which may increase the risk of VBI in these children. Studies report a 1% incidence of VBI in children under 18 years of age who completed the primary full HB vaccine immunization12. However, among children born to HBV-infected mothers, VBI incidence can reach 8% by the age of 513. And the consequences of HBV infection are more severe in children, with chronicity risks significantly higher than in adults14. Therefore, HBV vaccine breakthrough infection represents challenges within current immunization program.

This study, based on a multicenter prospective long-term follow-up cohort, aims to evaluate the feasibility of optimizing existing HBV immunization strategies in high-risk population to mitigate the risk of VBI. The children born to mothers positive for both HBsAg and HBeAg were followed up over the long term, with different doses of the HB vaccine administered after birth. The study monitored dynamic changes in anti-HBs levels and the incidence of VBI. The primary objective was to assess whether increased neonatal HB vaccine dose could delay anti-HBs decline in high-risk children, thereby reducing the risk of VBI. Additionally, the efficacy of booster immunization in preventing VBI was analyzed. This study aims to provide real-world evidence for further optimization of HBV immunization strategies and to explore more precise and effective approaches to HBV prevention for high-risk populations.

Results

The baseline characteristics between groups

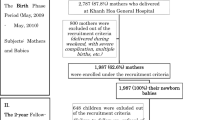

Of the 874 infants born to HBsAg and HBeAg-positive mothers who were HBsAg-negative at 7 months of age, 352 consented to participate in the long-term follow-up and were enrolled. As detailed in the Fig. 1, 150 mothers and 150 infants in the 10 μg HB vaccine group, and 199 mothers and 202 infants were the in the 20 μg HB vaccine group (3 twins). As presented in the Table 1, the mothers in the 20 μg HB vaccine group were older than those in the 10 μg HB vaccine group (median age in years: 28 vs. 23, P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed in maternal HBV DNA levels between groups (P = 0.892). In terms of baseline characteristics of infants, there were no differences in gender, birth weight, and feeding mode between groups (P > 0.05). The 20 μg HB vaccine group exhibited a higher cesarean delivery rate than the 10 μg group (76.2% vs. 60.0%, P = 0.001). Both groups followed the passive–active immunization protocol. All infants in the 20 μg HB vaccine group received 100 IU HBIG, compared to 43.3% and 56.7% of infants in the 10 μg group receiving 100 IU and 200 IU HBIG, respectively (P < 0.001, Table 1). No differences in baseline characteristics were observed between participants with and without long-term follow-up (Table S1 and Table S2). A total of 130 children (36.9%) received a booster HB vaccine during follow-up, including 55 (36.7%) in the 10 μg HB vaccine group and 75 (37.1%) in the 20 μg HB vaccine group. The booster vaccination rates were comparable between groups (P = 0.929). Specifically, in the 10 μg HB vaccine group, 12, 21, and 22 children received booster at 1–2, 2–3, and 3–5 years of age, respectively, while in the 20 μg HB vaccine group, the corresponding numbers were 6, 15, and 54. Details were shown in Fig. 1.

The longitudinal anti-HBs dynamics across immunoprophylaxis pattern groups

Given variations in vaccine dose and booster immunization, children were categorized into different immunoprophylaxis patterns for subsequent analysis. Dynamic changes of anti-HBs levels across groups were analyzed. At 7 months of age (before any booster immunization), the geometric mean concentration (GMC) of anti-HBs was 660.5 mIU/mL in the 10 μg group. In the 10 μg non-booster group, GMC of anti-HBs was 40.1, 34.8 and 88.4 mIU/mL at 2, 3 and 5 years of age, respectively; while in the 10 μg booster group, the GMC of anti-HBs maintained higher levels (392.3, 391.3, and 368.7 mIU/mL, respectively. Table 2). In the 20 μg group, the GMC of anti-HBs was 1679.9 mIU/mL at 7 months of age. Among non-booster children, GMC decreased to 208.1, 139.4, and 121.6 mIU/mL at ages 2, 3, and 5 years, respectively. While the 20 μg booster group maintained higher antibody levels, with GMCs of 567.7, 307.8, and 948.6 mIU/mL at the same time points (Table 2). Consistently higher anti-HBs levels were observed in booster-immunized children compared to non-booster children across both vaccine dose groups (all P < 0.05). Further analysis revealed significantly higher GMCs in the 20 μg non-booster group compared to the 10 μg non-booster group at ages 2 (P < 0.001) and 3 (P < 0.001), with comparable GMCs observed at ages 5 (P = 0.056).

At 7 months of age, all children in the 10 μg group were seropositive for anti-HBs. In the 10 μg non-booster group, seronegative rates were 21.0%, 25.6%, and 16.8% at ages 2, 3, and 5 years, respectively. In the 10 μg booster group, seronegative rates were 0%, 3.0%, and 1.8% at the corresponding ages (Table 2; Fig. 2; Fig. S1). Seronegative rates in the 20 μg non-booster group were 0%, 3.6%, 2.8%, and 3.1% at corresponding time points, whereas the 20 μg booster group maintained no seronegativity throughout follow-up (Table 2, Fig. 2 and Fig. S1). Booster-immunized children in the 10 μg group exhibited significantly lower seronegative rates compared to non-booster children from 7 months onward (all P ≤ 0.001), whereas this difference emerged after 2 years in the 20 μg group (all P < 0.05). Non-booster children in the 20 μg group maintained consistently lower seronegative rates compared to the 10 μg non-booster group across all time points (Fig. 2, all P < 0.001). No significant differences in seronegative rates were observed between the two dose groups among booster-immunized children across follow-up time points (Fig. S1, all P > 0.05).

Given the variable HBIG doses administered to children in the 10 μg HB vaccine group at birth, subgroup analysis of the 10 μg group evaluated potential HBIG doses effects (100 IU vs. 200 IU) on anti-HBs levels. Results presented in Table S3 indicated no significant association was observed between HBIG doses and anti-HBs levels at any time point.

Comparative analysis of VBI across the different immunoprophylaxis pattern groups

As shown in Table 3, VBI (anti-HBc positivity, either isolated or combined with HBsAg and/or HBV DNA positivity) rates did not differ significantly across different immunoprophylaxis pattern groups at 2 and 3 years of age (P = 0.826 and P = 0.250), with no cases of overt or occult HBV infection detected during these periods. By age 5, a significant difference was observed in VBI rates among groups (P = 0.035). A trend toward higher VBI rates was observed in the 10 μg HB vaccine non-booster group (14.7%) compared with the 10 μg booster group (3.6%, P = 0.034) and with both 20 μg groups (with booster: 4.0%, P = 0.021; without booster: 6.3%, P = 0.037). However, these differences did not remain statistically significant after adjustment (αadjust = 0.008). Similarly, within the 20 μg group, VBI rates showed a slight upward trend in non-booster children (6.3%) compared with booster ones (4.0%, P = 0.750). Additionally, overt (positive for both anti-HBc and HBsAg: 3 cases in the 10 μg HB vaccine group and 2 cases in the 20 μg HB vaccine group) and occult HBV infection (positive for both anti-HBc and HBV DNA, but negative for HBsAg:1 case in the 20 μg HB vaccine group) occurred exclusively in non-booster children at age 5.

Furthermore, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with VBI at age 5. Univariate analysis showed immunoprophylaxis patterns was associated with VBI risk (P = 0.033; Table 4). Following adjustment for maternal age, HBV DNA levels, infant gender, and HBIG dose, multivariate analysis still revealed a significant association between immunoprophylaxis patterns and VBI risk: compared to the 10 μg non-booster group, the 10 μg booster group exhibited reduced VBI risk (OR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.05–0.97). Increasing vaccine dose (regardless of booster administration) significantly reduced VBI risk compared to the 10 μg non-booster group, with greater reductions observed in booster-immunized children (20 μg non-booster: OR = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.09–0.78; 20 μg booster: OR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.04–0.68).

Discussion

The effectiveness of HBV vaccination programs is evident with a trend toward a decrease in HBV disease burden globally. However, concerns have been raised that high-risk population may experience breakthrough infection after vaccination, given that the persistence of vaccine-induced protection over the long term has not been fully established. This study focused on the long-term protection of the different dose of HB vaccine on newborns born to HBsAg and HBeAg positive mothers, evaluated the effectiveness of HB vaccine dose and booster vaccination in preventing VBI.

Following full immunization with the HB vaccine, the anti-HBs levels in children exhibit a gradual decline over time15. A Chinese study evaluating primary HB vaccine immunization during infancy reported seropositivity rates (≥10 mIU/mL) of 86.5% in 1-year-olds and 71.0% in 5-year-olds, with GMCs of 296.6 mIU/mL and 51.6 mIU/mL, respectively16. A meta-analysis focusing on the general population evaluated the immunogenicity of the HB vaccine in children and showed that anti-HBs persistence fell below 75.0% in children 5 years after HB vaccine immunization17. Among high-risk populations, a cohort of children born to HBV-infected mothers exhibited a decline in anti-HBs positivity from 98.3% at 12 months to 89.8% at 5 years post-primary vaccination18. Consistent with prior findings, this study demonstrated an overall age-related decline in anti-HBs levels among participants. Seropositivity rates declined from 100% at 7 months post-vaccination to 94.0% by 5 years of age in the overall children. Notably, the 20 μg HB vaccine non-booster group maintained higher anti-HBs levels compared to the 10 μg HB vaccine non-booster group before 5 years old, with significantly higher seropositivity rates observed at all post-7-month time points. We hypothesize that the sustained higher anti-HBs levels associated with the 20 μg HB vaccine group may be attributed to the elevated peak concentrations achieved following primary immunization. Anti-HBs levels at 7 months of age likely represent post-vaccination peak concentrations. At this time point, the 20 μg HB vaccine group exhibited significantly higher GMCs (1679.9 mIU/mL vs. 660.5 mIU/mL) and a greater proportion of infants with high antibody levels (≥1000 mIU/mL: 61.4% vs. 34.7%). These findings suggest that the higher initial vaccine dose may increase peak anti-HBs concentrations, prolonging antibody persistence. It is also important to consider the potential influence of passively acquired antibodies from the HBIG on early anti-HBs titers. The passively transferred anti-HBs from HBIG has an estimated half-life of approximately 3–4 weeks and typically declines to undetectable levels within a few months after birth19. Consistent with this pharmacokinetic profile, our study found no significant difference in anti-HBs levels at 7 months between infants in the 10 μg vaccine group who received 100 IU and those who received 200 IU of HBIG. Considering both the rapid decline of passively acquired antibodies and our own data, the contribution of HBIG to anti-HBs measured at 7 months is expected to be minimal. In addition, consistent with expectations, booster-immunized children in both dose groups showed higher anti-HBs levels and lower seronegative rates, confirming the efficacy of booster vaccinations in enhancing antibody levels.

The decline in anti-HBs levels, particularly following post-seroconversion, may inadequately protect against HBV VBI in children due to their immature immune systems. In this study, some children who did not receive booster immunization exhibited elevated anti-HBs levels at subsequent follow-up assessments, which suggested potential natural boostering20. It appeared that children born to mothers positive for both HBsAg and HBeAg exhibited evidence of exposure to HBV, suggesting a potentially higher susceptibility to VBI in this population. Given the higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in vaccinated children with HBV infection compared to pre-vaccination era HBV carriers21, VBI among children born to HBeAg-positive mothers necessitate heightened clinical vigilance and proactive intervention strategies. Anti-HBc positivity is a well-recognized marker of HBV exposure22. In children younger than 2 years, it mainly reflects transplacental transfer of maternal antibody, whereas positivity beyond 2 years of age may indicate HBV VBI23,24. Previous studies have reported that the incidence of VBI among general children at the age of 5 varies across studies, approximately ranging from 0.5% to 6%12,25. Children born to HBV-infected mothers, particularly those with high viral loads and HBeAg positivity, face higher risk of VBI. The results of a study, focusing on children born to HBeAg-positive mothers and vaccinated with the HB vaccine after birth, showed that the incidence of VBI could reach 13% at the age of 526. This VBI rate was comparable to that observed in the 10 μg HB vaccine non-booster group (14.7%) but higher than other immunoprophylaxis pattern groups in our study, which indicated that the administration of higher vaccine doses or booster immunization might both have contributed to the lower incidence of VBI. Considering the changing trends of anti-HBs levels in these children, it is suggested that for high-risk children, increasing the HB vaccine dose for the primary immunization was associated with prolonged higher anti-HBs levels, which correlated with a reduction in subsequent VBI.

The necessity of booster immunization post-hepatitis B vaccination may vary across populations. The WHO does not recommend booster doses after the primary HB vaccination in immunocompetent individuals27. According to Chinese guidelines, children born to HBeAg-positive mothers are recommended to receive timely booster immunization28. As previously discussed, booster immunization significantly increases anti-HBs concentrations. Notably, VBI incidence trended lower in booster-immunized children across both 10 μg HB vaccine and 20 μg HB vaccine groups, with overt and occult infection exclusively reported in non-booster children. And the 10 μg HB vaccine group exhibited a more pronounced divergence in VBI rate between booster and non-booster children, though statistical significance was not achieved. These findings suggested that HB vaccine booster immunization may reduce the incidence of VBI, as well as overt and occult HBV infections, particularly in children who received standard postnatal vaccine doses among high-risk popilation. Our data highlight the potential importance of evaluating booster strategies in children born to HBsAg/HBeAg-positive mothers. However, this raises a critical question: what is the optimal timing for booster administration? Ideally, routine anti-HBs monitoring in high-risk children would inform personalized booster schedules. Cost-effectiveness challenges arise, as many medium- and high-endemic regions for HBV are low to middle-income countries, where frequent regular testing may not be feasible. Our data indicate that after completing the full vaccination schedule at birth, anti-HBs levels declined most rapidly before the age of 2, with the highest incidence of VBI observed at the 5 years old. Therefore, administering a booster immunization either before the age of 2 or before 5 years old appears to be the more effective strategy, but further verification is still needed. Under the current circumstances, our findings support the consideration of a two-tiered approach for this population. For regions where regular monitoring of antibody levels is impractical, increasing the dose of HB vaccine administered to high-risk newborns after birth may help maintain higher protective antibody levels for a longer duration, thereby reducing the incidence of subsequent VBI. For areas where follow-up monitoring is feasible, a standardized protocol for regular anti-HBs level testing should be implemented for high-risk children, with personalized booster immunization schedules tailored according to individual anti-HBs levels, thus preventing the occurrence of VBI. Indeed, if achievable, as demonstrated by the multivariate analysis results of this study, increasing the neonatal vaccine dose for high-risk children coupled with childhood booster immunization represents a combined strategy that may minimize the risk of HBV breakthrough infection.

While our findings support the benefits of an increased vaccine dose or timely booster to sustain protective anti-HBs levels, the magnitude of improvement remains biologically constrained by the inherent properties of current recombinant HBsAg vaccines. It is conceivable that these vaccines have reached their upper limit in eliciting durable humoral immunity. In this context, novel adjuvant systems, such as aluminum–manganese–based formulations, may enhance antigen presentation and immune memory without escalating antigen quantity. Manganese acts as a cofactor in innate immune signaling pathways and can potentiate STING-mediated responses, thereby strengthening the link between innate activation and adaptive antibody formation. Early preclinical data support their superior immunogenicity and safety profile29. Continued translational research exploring such next-generation vaccines could therefore redefine the long-term prevention landscape of HBV mother-to-child transmission.

This study has several limitations. First, as an observational study rather than a randomized controlled trial (RCT), participants were not randomly assigned to study groups, and follow-up protocols could not achieve the rigor of an RCT design. However, as a multi-center cohort study, we made every effort to ensure that all centers adhered strictly to a unified research protocol throughout the study. And there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the two groups. While acknowledging potential bias inherent to observational design, we consider such bias minimized. Second, a portion of the children agreed to participate in the long-term follow-up. However, there were no differences in the baseline characteristics between the children who participated in the long-term follow-up and those who did not, indicating that this potential bias is limited. Third, due to limitations in sample size, as well as the racial and regional characteristics of the study population, future research with larger sample sizes and more diverse populations is needed to explore and validate these findings. In addition, hemoglobin concentration and iron status were not assessed prior to vaccination. Given evidence that iron deficiency may increase systemic retention of aluminum adjuvants, regular monitoring of hematologic and iron parameters could help mitigate potential aluminum accumulation or toxicity, especially in infants from resource-limited regions30,31. Future studies incorporating these evaluations would further enhance both the safety and interpretability of HBV vaccine research. Finally, hepatic biochemical parameters were not measured in this study. As the research design focused primarily on evaluating immunological responses, data on liver function were not collected during follow-up. We acknowledge that the absence of hepatic monitoring limits our ability to assess potential subclinical liver changes. Future studies incorporating systematic hepatic assessments would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of vaccine safety.

To our knowledge, this study is the first long-term follow-up multi-center study to evaluate the effect of different neonatal HB vaccine doses and booster immunization on the anti-HBs levels and the incidence of VBI among children born to mothers who are positive for both HBsAg and HBeAg. In this cohort, an increased dose of HB vaccine after birth was associated with higher levels of protective anti-HBs and reduced occurrence of VBI among high-risk children. Meanwhile, booster immunization was associated with a lower risk of VBI, including overt and occult HBV infection, especially in children who received the standard vaccine dose. To mitigate HBV vaccine breakthrough infections among high-risk children, regionally tailored strategies may be considered, such as enhanced birth-dose vaccination and/or periodic anti-HBs monitoring to guide timely booster immunization, particularly for those receiving standard postnatal vaccination.

Methods

Study participants and design

This study based on a multicenter, prospective cohort study, recruited HBsAg-positive mothers and their infants from the First Hospital of Jilin University, Jiangsu Maternal and Child Health Care Center, and Henan Maternal and Child Health Care Center between 2009 and 2017. Neonates in the cohort received combined active-passive immunization after birth and was suggested to return for post-vaccination serologic testing at 7 months of age. All participating centers strictly adhered to the standardized research protocol, which governed the implementation of participant screening based on predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria, vaccine administration, laboratory testing procedures, and follow-up management throughout the study32.

This study included infants in this cohort born to HBsAg (+) and HBeAg (+) mothers, who were HBsAg negative at 7 months of age and completed the full longitudinal follow-up. Infants with maternal co-infections (hepatitis A/C/D/E or human immunodeficiency virus) was excluded. The procedures of the studies followed were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (2012-098), and the Ethics Committees of the Peking University Health Science Center (IRB00001052-12041 and IRB00001052-12042). Written informed consent was obtained prior to their involvement in the study.

Vaccination

All infants received a combined regimen of passive and active immunization. Infants from Jilin Province received a 20 μg recombinant yeast-derived HB vaccine (Dalian Hissen Bio-Pharm, Dalian, China), whereas those from Jiangsu and Henan received a 10 μg recombinant HB vaccine (standard vaccine dose; Dalian Hissen Bio-Pharm, Dalian, China, or Shenzhen Kangtai Biological Products, Shenzhen, China), each administered at 12 hours after birth, 1 month of age, and 6 months of age. All newborns received hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) within 12 h of birth as part of standard passive immunization. In Jilin Province, all infants received 100 IU HBIG; in Jiangsu and Henan, infants received either 100 IU or 200 IU (assigned by birth order). During the follow-up period, a booster dose of HB vaccine was recommended for children exhibiting anti-HBs antibody levels <10 mIU/mL.

Follow-up and data collection

Infants who were HBsAg negative at 7 months of age and consented to participate in the long-term follow-up were assessed at the ages of 2, 3, and 5 years. Blood samples were collected from children at each follow-up visit. The questionnaire covered demographic data that was collected via questionnaires when pregnant woman visited the outpatient clinic (age, HBV DNA levels and ALT during pregnancy). After delivery, mothers were followed up by telephone four times (24 h, 14 days, 1 month and 6 months after birth) to obtain the following information: delivery mode, feeding mode (breastfeeding or mixed feeding was defined as breastfeeding; otherwise, feeding mode was defined as nonbreastfeeding), infant gender, infant weight, and HBIG and HBV vaccination dose and the time of injection. Data on booster vaccination records were obtained at the 2-, 3-, and 5-year follow-up.

Laboratory examinations

HBV serological markers (including HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe) and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc)), were quantified using the Abbott Architect i2000SR analyzer (Abbott Diagnostic, Chicago, IL, USA) via chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA). The HBsAg assay exhibited a detection range of 0.05–250 IU/mL. Samples exceeding the HBsAg upper detection limit (>250 IU/mL) underwent manual dilution prior to retesting. Anti-HBs level ≥ 10 mIU/mL were classified as seroprotective. For HBeAg, anti-HBe and anti-HBc assays, results were expressed as the ratio of the relative light unit (RLU) to the cut of RLU (S/CO). An S/CO values < 1.0 were interpreted as negative for HBeAg and anti-HBc, whereas S/CO > 1.0 indicated anti-HBe negativity. HBV DNA quantification was performed using the Abbott Real Time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Assaym2000 (m2000sp + m2000rt) system (Abbott Molecular, Green Oaks, IL, USA). The assay’s lower and upper limits of quantification (LLOQ and ULOQ) were 1.18 log10 IU/mL and 9.00 log10 IU/mL, respectively. Samples with HBV DNA levels below the LLOQ (<1.18 log10 IU/mL) were classified as negative.

Definitions

HBV immunoprophylaxis failure was defined as HBsAg seropositivity at 7 months; success was defined as HBsAg negativity and anti-HBs levels ≥10 mIU/mL. HBsAg-negative individuals with anti-HBs levels <10 mIU/mL were categorized as non-responders. Anti-HBs levels were stratified as follows: <10 mIU/mL (negative), 10 to <100 mIU/mL (low), 100 to <1000 mIU/mL (medium), and ≥1000 mIU/mL (high). HBV vaccine breakthrough infection was defined as anti-HBc positivity (isolated or combined with HBsAg/HBV DNA positivity) detected from age 2 years23. Among them, overt infection was defined as HBsAg positivity, whereas occult infection required HBsAg negativity with detectable HBV DNA.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as either mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data, and differences among groups were evaluated using t test or Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages and analyzed using χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. When performing multiple pairwise comparisons between groups, the significance threshold was established according to Bonferroni’s method. The odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using logistic regression analysis to identify risk factors for VBI. Statistical analysis and plotting were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 26.0), and software R version 4.4.3. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The raw data generated from this study can be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Global prevalence cascade of care, and prophylaxis coverage of hepatitis B in 2022: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8, 879–907 (2023).

World Health Organization. “Global Hepatitis Programme,” Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016–2021: towards ending viral hepatitis. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2016.06 (2016).

World Health Organization. Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper: July 2017.92, 369.4.(2017).

Cui, F. et al. Prevention of chronic hepatitis B after 3 decades of escalating vaccination policy, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 23, 765–772 (2017).

Hui, Z. et al. New progress in HBV control and the cascade of health care for people living with HBV in China: evidence from the fourth national serological survey, 2020. Lancet Reg Health—West Pac. 51 (2024).

Van Damme, P. Long-term protection after hepatitis B vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 1–3 (2016).

Bruce, M. G. et al. Antibody levels and protection after hepatitis B vaccine: results of a 30-year follow-up study and response to a booster dose. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 16–22 (2016).

Scheifele, D. W. Will infant hepatitis B immunization protect adults? Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 38, S64–s6 (2019).

Klinger, G., Chodick, G. & Levy, I. Long-term immunity to hepatitis B following vaccination in infancy: real-world data analysis. Vaccine 36, 2288–2292 (2018).

Hammitt, L. L. et al. Hepatitis B immunity in children vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine beginning at birth: a follow-up study at 15 years. Vaccine 25, 6958–6964 (2007).

Chang, K. C. et al. Survey of hepatitis B virus infection status after 35 years of universal vaccination implementation in Taiwan. Liver Int. 44, 2054–2062 (2024).

Ni, Y. H. et al. Two decades of universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan: impact and implications for future strategies. Gastroenterology 132, 1287–1293 (2007).

Song, Y. et al. A booster hepatitis B vaccine for children with maternal HBsAg positivity before 2 years of age could effectively prevent vaccine breakthrough infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 22, 863 (2022).

Hu, Y. & Yu, H. Prevention strategies of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Pediatr. Investig. 4, 133–137 (2020).

Zhao, Y. L. et al. Immune persistence 17 to 20 years after primary vaccination with recombination hepatitis B vaccine (CHO) and the effect of booster dose vaccination. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 482 (2019).

Shen, S. et al. Persistence of immunity in adults after 1, 5 and 10 years with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in Beijing in 2010–2020. Vaccines 10 (2022).

Ramrakhiani, H. et al. Long-term immunity and anamnestic response following hepatitis B vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Viral Hepat. 32, e70003 (2025).

Poovorawan, Y., Sanpavat, S., Chumdermpadetsuk, S. & Safary, A. Long-term hepatitis B vaccine in infants born to hepatitis B antigen positive mothers. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal neonatal Ed. 77, F47–F51 (1997).

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Hepatitis B Immune Globulin (Human) Nabi-HB, Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/74707/download (2007).

Roznovsky, L. et al. Long-term protection against hepatitis B after newborn vaccination: 20-year follow-up. Infection 38, 395–400 (2010).

Chang, M. H. et al. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma by universal vaccination against hepatitis B virus: the effect and problems. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 7953–7957 (2005).

Allain, J. P. & Opare-Sem, O. Screening and diagnosis of HBV in low-income and middle-income countries. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 643–653 (2016).

Lee, P. I., Lee, C. Y., Huang, L. M. & Chang, M. H. Long-term efficacy of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and risk of natural infection in infants born to mothers with hepatitis B e antigen. J. Pediatr. 126, 716–721 (1995).

Roushan, M. R. H., Saedi, F., Soleimani, S. & Baiany, M. Changes in the anti-HBc profile of infants born to HBV-infected mothers from Iran. Vaccine 34, 4475–4477 (2016).

Yang, Y. T., Huang, A. L. & Zhao, Y. The prevalence of hepatitis B core antibody in vaccinated Chinese children: a hospital-based study. Vaccine 37, 458–463 (2019).

Chen, H. L. et al. Effects of maternal screening and universal immunization to prevent mother-to-infant transmission of HBV. Gastroenterology 142, 773–81.e2 (2012).

World Health Organization Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper, July 2017—recommendations. Vaccine 37, 223–225 (2019).

You, H. et al.Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B (2022 version)[in Chinese]. Chin. J. Infect. Dis. 41, 3–28 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Manganese-modified aluminum adjuvant enhances both humoral and cellular immune responses. Adv. Health. Mater. 13, e2401675 (2024).

Cirovic, A., Cirovic, A., Ivanovski, A. & Ivanovski, P. Neonatal hepatitis B vaccination: reevaluating timing and adjuvants for enhanced safety and effectiveness. Pediatr. Discov. 1, e47 (2023).

Cirovic, A. & Cirovic, A. Aluminum bone toxicity in infants may be promoted by iron deficiency. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 71, 126941 (2022).

Pan, Y. C. et al. The role of caesarean section and nonbreastfeeding in preventing mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus in HBsAg-and HBeAg-positive mothers: results from a prospective cohort study and a meta-analysis. J. Viral Hepat. 27, 1032–1043 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Jilin Provincial Health Commission (2015Z003). The authors would like to thank all of those who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J. and J.L. designed and planned the study. Y.C.P., Y.H.W., J.W., Y.R.S., Y.L., C.W. were involved in the management of participants and data collection. Y.C.P., Y.H.W. and Z.F.J. contributed to interpretation and data analysis. Y.C.P. drafted the manuscript, J.J. and J.L. modified the draft. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Y., Wu, Y., Wang, J. et al. Increased neonatal vaccine dose or booster immunization prevents hepatitis B vaccine breakthrough infection in children from HBsAg and HBeAg positive mothers. npj Vaccines 11, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01327-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01327-2