Abstract

Organic and inorganic phosphonates often co-exist in municipal sewage, and it is a challenge to remove them simultaneously. Nanoparticle Fe3O4 (Fe3O4 NPs) has attracted significant attention due to its high adsorption activity, low cost, environmental friendliness, and magnetic separation. Herein, the adsorption performance and mechanism of hydroxyethylidene diphosphonic acid (HEDP) and orthophosphate (PO43−) onto Fe3O4 NPs were systematically investigated. When the dosages were 0.4 g/L, the removal efficiencies of HEDP and PO₄³− reached 96.3% and 95.1%, respectively. pH had no significant impact on the adsorption, whereas the presence of HCO3−/CO32− markedly suppressed the removal of HEDP and PO43−. The adsorption of HEDP and PO43− onto Fe3O4 NPs conformed to the pseudo-second-order kinetics and Langmuir isotherm models in single and binary P systems. HEDP consistently inhibited the removal of PO43− in the binary P system. The adsorption mechanisms were primarily driven by the combined effect of electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and coordination complexation. DFT molecular simulation showed higher adsorption energy between HEDP and Fe3O4 NPs, and the simulation outcomes were in excellent agreement with the experimental data. Although the adsorption of HEDP and PO43− was competitive, total phosphorus in the effluent of municipal sewage could still meet the discharge standard.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is a vital element and required by all living organisms, widely used in many industries, which inevitably generates large amounts of industrial wastewater containing P, such as textile wastewater, papermaking wastewater, circulating cooling water, and membrane concentrates1,2. When this wastewater enters the centralized wastewater treatment plants or municipal sewage treatment plants for treatment, the effluent still contains a certain amount of total phosphorus (<0.3 mg/L), and even occasionally exceeds the discharge standards due to incomplete treatment by current processes3,4. Among these P species, inorganic P usually exists in the form of orthophosphate (PO43−), above 0.02 mg-P/L of which could trigger eutrophication2,5. On the other hand, the global consumption of organic phosphates (OP) has reached 10.183 million tons as of 20236. Each year, over 9000 tons of substances like hydroxy ethylidene diphosphonic acid (HEDP) are released into aquatic environments, posing a significant risk of eutrophication due to their potential conversion into bioavailable PO43− (refs. 7,8). As a result, it is essential to develop and implement advanced technologies that can effectively remove OP and PO43− from wastewater to address the growing challenges of stricter discharge regulations.

Traditional phosphorus removal techniques employed in municipal wastewater treatment plants encompass biological and chemical processes9,10,11,12. Nevertheless, these methods predominantly target PO43− removal, with OP often being excluded as a primary pollutant of concern11. The presence of OP renders it challenging to consistently achieve discharge standards for total P in the effluent13. Therefore, various advanced oxidative methods (e.g., ozone, Fenton, and ultraviolet oxidation) have been employed to convert OP into PO43− (refs. 14,15,16). However, the generation of PO43− requires additional removal. In comparison to other methods, adsorption presents a promising alternative for simultaneously eliminating both OP and PO43− in a single step. This approach is particularly advantageous due to its high efficiency and low cost in treating wastewater with low phosphorus concentrations17,18,19.

Nanomaterials are widely utilized in adsorption applications due to their exceptional adsorption efficiency under optimized conditions, such as nano-alumina, nano-magnesium oxide, and nano-manganese oxide20,21,22. However, the practical application of these materials is significantly hindered by the challenges associated with the recovery of adsorbents. Magnetic nanomaterials not only exhibit excellent adsorption properties but, most importantly, their strong magnetic characteristics enable easy solid-liquid separation under an external magnetic field16,23. Oxides of iron, acting as a natural adsorptive material for phosphorus (P), play a substantial role in influencing the phosphorus cycle within aquatic environments due to their interactions. The hydroxyl groups and iron ions formed on the surface of the adsorbent by iron elements are the key active sites for phosphorus adsorption. These sites can react with phosphate ions through complexation or precipitation, thereby achieving highly efficient phosphorus removal24. Thus, magnetic iron oxide nanomaterials are prepared and employed for the efficient removal of P from wastewater matrices. Li Lai et al. synthesized lanthanum-loaded Fe3O4 materials, exhibiting a remarkable adsorption capacity for orthophosphate, reaching up to 27.8 mg/g25. Wang Zhe et al. developed a composite material consisting of Zr and Fe3O4, which exhibits a removal efficiency of 95% for orthophosphate under an initial concentration of 2 mg/L12,26. Iqra Irfan et al. synthesized a biochar loaded with Fe and La, which achieved an adsorption capacity of 26.02 mg/g for PO43− (ref. 27). Sabolc Pap et al. synthesized a biochar loaded with Ce and La, which achieved an adsorption capacity of 40 mg/g for PO43− (ref. 28). However, research on the adsorption of organic phosphorus by Fe, especially the simultaneous removal of organic and inorganic phosphorus, is rarely reported.

The study primarily focuses on the removal of low-concentration, difficult-to-remove HEDP from wastewater using adsorption methods, as well as the simultaneous phosphorus removal from wastewater containing both organic and inorganic phosphates. Therefore, magnetic nanoparticles Fe3O4 were synthesized through the co-precipitation method and then applied for the simultaneous removal of low-concentration organic phosphorus and orthophosphate from wastewater in this study. The primary purposes of this study were to: (i) examine the adsorption behavior and the influencing parameters of Fe3O4 NPs on HEDP and PO43− via batch experiments, (ii) ascertain the adsorption kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamics of Fe3O4 in single and binary P systems, (iii) Uncover the fundamental adsorption mechanism by employing a range of material characterization methods alongside density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

Results

Characterization of Fe3O4 NPs

The specific surface area of adsorbents was a crucial factor influencing adsorption efficiency. The surface area of Fe3O4 NPs was 99.5 m²/g, which provided adsorption sites for organic phosphorus and orthophosphate.

The surface of the material could be comprehensively assessed through SEM characterization. Figure 1a illustrates that Fe3O4 NPs synthesized by co-precipitation are spherical. with an approximate size of 30.0 nm. Prior to the reaction, the adsorbent surface is characterized by numerous small spherical structures. Following the reaction, the interstitial spaces between the spherical structures on the surface are minimized, resulting in a smoother surface across the entire adsorbent. During the adsorption process, the rearrangement and bonding of surface atoms may lead to surface reconstruction, which further reduces surface defects and irregularities.

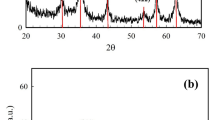

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was employed to investigate the phase structure of the synthesized Fe3O4 NPs, with a diffraction angle range of 0-85°, as illustrated in the Fig. 1d The results indicate that the XRD pattern of Fe3O4 NPs exhibits a total of six diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 30.1°, 35.5°, 43.1°, 53.4°, 47.0°, and 62.6°. These peaks correspond to the (200), (311), (400), (422), (511), and (440) planes of Fe3O4 NPs with a spinel-type structure, in accordance with the standard Fe3O4 NPs diffraction pattern (PDF19-0629). No additional impurity peaks were observed in the diffraction pattern, indicating high purity of the Fe3O4 NPs sample.

To clarify the adsorption mechanism of Fe3O4 NPs on HEDP and PO43−, FTIR spectroscopy was used to analyze the functional groups of the Fe3O4 NPs before and after adsorption. As shown in Fig. 1e, a peak at 3459 cm−1, corresponding to the hydroxyl O-H group, shifted slightly to 3478 cm−1 for HEDP and to 3512 cm−1 for PO43− after adsorption. This shift suggests the formation of hydrogen bond interactions between the adsorbent and phosphate species29. Specifically, the oxygen atom in the P-O bonds of HEDP and PO43− serves as a hydrogen bond acceptor, forming an intramolecular hydrogen bond with the hydroxyl hydrogen atom of the Fe3O4 material Additionally, prominent peaks at 1022 cm−1 and 1020 cm−1 were observed after the adsorption process, which may indicate the formation of an inner-sphere surface complex between phosphorus and Fe3O45. A peak at 580 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibration of the Fe-O bond, was also detected.

The Fig. 1f shows the hysteresis loop of Fe3O4 NPs. Under the scanning conditions of an external field ranging from −10.0 kOe to 10.0 kOe, the hysteresis loop exhibits an “S” shape, characteristic of most magnetic materials. This indicates that Fe3O4 NPs magnetization strength remains consistent when subjected to magnetic fields of the same magnitude in different directions. The sample’s saturation magnetization reached 50.0 emu/g, facilitating the easy separation of Fe3O4 NPs from wastewater.

Effect of adsorbent dosage, initial pH, and matrix

The removal of HEDP and PO43− in single P system at different Fe3O4 NPs dosage was given in Fig. 2a It was evident that the removal of HEDP or PO43− was significantly enhanced accompanied with the increase of adsorbent dosage from 0.1 g/L to 0.5 g/L, achieving a removal rate of 96.3% and 95.1%, respectively. When the Fe3O4 NPs dosage was ≥0.4 g/L, the residual concentration of HEDP or PO43− was reduced to below 0.05 mg/L. Therefore, considering both cost and treatment effectiveness, 0.4 g/L was selected as the optimal amount of Fe3O4 NPs in the experiments.

a The effect of different adsorbent dosages on the adsorption of HEDP and PO43−by Fe3O4 NPs in single P system; b the effect of different initial pH of wastewater on the adsorption of HEDP and PO43− by Fe3O4 NPs in single P system; c, d the effect of matrix of wastewater on the adsorption of HEDP and PO43− by Fe3O4 NPs in single P system (test conditions: initial P concentration = 1 mg-P/L, T = 298 K, t = 12 h; initial pH (a, c, d) = 7; Fe3O4 NPs dosage (b, c, d) = 0.4 g/L).

Figure 2b illustrates the effect of initial solution pH on the removal of HEDP and PO43− in a single P system. It is revealed that the removal efficiency decreased slowly as the pH increased from 3 to 11. Under low pH conditions, hydroxyl groups on the Fe3O4 NPs surface bind with hydrogen ions from the solution, resulting in a positively charged surface2. In aqueous solutions, the predominant forms of orthophosphate are H2PO4− and HPO42−. The positively charged Fe3O4 NPs particles attract negatively charged phosphorus species through electrostatic interactions, facilitating phosphorus adsorption. As the pH increases, the positive charge on the Fe3O4 NPs surface diminishes, leading to a reduced electrostatic attraction to the negatively charged phosphorus species. This decrease in electrostatic attraction hampers P adsorption, resulting in reduced efficiency of phosphorus removal by Fe3O4 NPs at higher pH values. This phenomenon was consistent with findings from Li Chuang et al. studies11.

Figure 2b showed the variation in Zeta potential of Fe3O4 NPs across a range of pH values. Analysis of the figure reveals that as the pH of the solution decreases, the Zeta potential of Fe3O4 NPs exhibits a progressive increase. This observation suggests that a reduction in pH leads to a corresponding increase in the positive charge on the Fe3O4 NPs surface. Given that phosphate ions are present in the solution as negatively charged species, a lower pH enhances the affinity of Fe3O4 NPs for phosphorus adsorption.

Various anions and cations (e.g., Cl−, SO₄²−, NO₃−, HCO₃−, Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) are commonly present in wastewater, and they can either enhance or hinder the removal of total TP via adsorption. Figure 3c, d illustrates the impact of these ions (the concentrations are 0, 1, 5, and 10 mM) on the adsorption of PO₄³−and HEDP by Fe3O4 NPs in a single system, respectively. The presence of co-existing ions such as Cl−, SO₄²−, NO₃−, Ca²⁺, and Mg²⁺ had minimal effect on the adsorption of both phosphorus species. However, the presence of HCO₃−/CO₃²− in the solution significantly reduced the removal efficiency of both PO₄³− and HEDP. This may be due to the competition between HCO3−/CO32− and P, which makes HCO3−/CO32− easier to combine with iron on the adsorbent surface29. It is also possible that the higher concentration of HCO3−/CO32− increases the solution pH, which in turn reduces the adsorption capacity of Fe3O4 NPs11. The formation of a negatively charged layer on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs due to HCO3−/CO32− can lead to electrostatic repulsion with PO₄³− and HEDP, thereby inhibiting phosphate adsorption.

a Adsorption kinetics of HEDP on Fe3O4 NPs in single P systems. b Adsorption kinetics of PO43− on Fe3O4 NPs in single P systems. c Adsorption kinetics of HEDP on Fe3O4 NPs in binary P systems. d Adsorption kinetics of PO43− on Fe3O4 NPs in binary P systems (test conditions: Fe3O4 NPs = 0.4 g/L, initial pH = 7, T =298 K, t = 0~6 h, HEDP or/and PO43− = 1 mg-P/L).

Adsorption kinetics

Adsorption rate is a significant index in adsorption experiments. Figure 4 shows the HEDP and/or PO43− adsorption kinetics, and the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) kinetic models were adopted to model the experimental data. For the sole adsorption of HEDP or PO43−, approximately 90% of HEDP was rapidly adsorbed onto the Fe3O4 NPs surface within 60 min, and then gradually reached equilibrium; approximately 90% of PO43− were enriched on the Fe3O4 NPs surface within 90 min. As shown in Table 1, the PSO model presented a superior fit for the adsorption kinetics of HEDP or PO43− on Fe3O4 NPs (RPSO2 > RPFO2). A comparison of the adsorption rates reveals that the adsorption of HEDP onto Fe3O4 NPs occurs at a faster rate than that of PO43−. Compared with Wan’s and Shao’s research, we have a faster adsorption rate for HEDP20,21.

a Adsorption isotherms of HEDP on Fe3O4 NPs the isotherm models fitting under different temperatures. b Adsorption Isotherms of PO43− on Fe3O4 NPs the isotherm models fitting under different temperatures. c The adsorption isotherms of HEDP and in single and binary systems. d The adsorption isotherms of PO43− and in single and binary systems (Test conditions: Fe3O4 NPs = 0.4 g/L, initial pH = 7, T = 298 K, 308 K and 318 K, t = 12 h, HEDP or/and PO43− = 1 mg-P/L).

In the binary P system, approximately 90% of the PO43− species were adsorbed within 120 min, with the adsorption equilibrium being reached at 240 min, a time extension compared to the single P system. The adsorption equilibrium time for HEDP remained relatively constant, although a slight decrease in its adsorption capacity was observed. These findings indicate a significant competitive adsorption interaction between the two phosphorus-containing species on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs. Furthermore, the adsorption of PO43− was significantly inhibited by HEDP, in terms of both adsorption rate and capacity, whereas the adsorption of HEDP was also partially suppressed. These results suggest that HEDP exhibits a competitive advantage in the adsorption process. Kinetic analysis of the adsorption constants further reveals a substantial reduction in the adsorption rate within the binary system.

Adsorption isotherms and thermodynamics

The use of adsorption isotherms is a standard method for interpreting equilibrium adsorption data, which helps to disclose the basic traits and underlying mechanisms of the adsorption process by analyzing the isotherm’s shape, the amount adsorbed, and the equilibrium conditions. Figure 5 presents the adsorption isotherms for HEDP or PO43− on Fe3O4 NPs at different temperatures. The data suggest that the adsorption capacity of HEDP or PO43− species on Fe3O4 NPs increases with an increase in the initial concentration. Based on the classification system for adsorption isotherms by Giles et al.30, the P adsorption isotherm on Fe3O4 NPs is classified as Langmuir type L subgroup 2, indicating a Langmuir monolayer adsorption model. This suggested that as the initial concentrations of HEDP and PO43− increased, the adsorption sites on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs became limited and were fully occupied, leading to saturation. In the single system, an increase in temperature resulted in a decrease in the adsorption capacity of Fe3O4 NPs for both HEDP and PO43−.

Furthermore, the experimental data were analyzed using two prominent adsorption isotherm models: the Langmuir model and the Freundlich model. The constants derived from these isotherms are detailed in Table 2. Both models provided a good fit to the data, with the Langmuir model showing a more accurate fit than the Freundlich model, as evidenced by the correlation coefficients (RL2 > RF2 > 0.95). The superior fit of the Langmuir equation to the data supports the hypothesis of a monolayer adsorption of P molecules on the adsorbent, given that the Langmuir isotherm presupposes a homogeneous surface. The theoretical maximum monolayer adsorption capacities, qmax, were determined to be 35.5 mg/g for HEDP and 35.2 mg/g for PO43−. Moreover, the adsorption efficiency observed surpasses that of the modified kaolin as reported by Wan20.

Moreover, in the binary system, the adsorption capacities for both PO43− and HEDP were found to decrease relative to their individual adsorption processes, with a more pronounced reduction observed in the adsorption of PO43−. This pattern aligns with the findings from kinetic studies and indicates that HEDP possesses a competitive edge during the adsorption process.

Through the study of adsorption thermodynamics, a comprehensive understanding of the interactions and energy transformations involved in the adsorption process can be obtained, thereby elucidating the potential mechanisms underlying the distribution of adsorbates on the surface of the adsorbent. The data were subjected to thermodynamic analysis based on the established equations, with the results presented in Table 3. At varying temperatures, the ΔG values were positive, while both ΔS and ΔH were negative, suggesting that the adsorption process is exothermic in nature. As the temperature increased, the ΔG value progressively rose, implying that higher temperatures are unfavorable to the adsorption process.

Desorption regeneration performance

The Fig. 6 illustrates the results of the adsorption-desorption regeneration experiments of HEDP and PO43− on Fe3O4 NPs. The 1 mol/L NaOH solution used in the experiment effectively facilitated the release of HEDP and PO43−, achieving a release efficiency of up to 90%. The data indicated that the adsorption capacity of Fe3O4 NPs for HEDP and PO43− gradually decreased with increasing cycles of regeneration. This decrease in capacity is likely due to incomplete release of HEDP and PO43− during the alkaline washing process, where residual HEDP and PO43− occupied adsorption sites, thereby reducing the material’s adsorption efficiency. After five cycles, the material maintains an HEDP and PO43− removal efficiency of approximately 51.1% and 49.3%. Fe3O4 NPs possessed good cyclic regeneration capability in this study. Compared with the gel microspheres modified by lanthanum and nickel as studied by Yue Zhou et al.4, Fe3O4 NPs also maintained good phosphorus removal performance after five cycles of adsorption and desorption. (Fig. 7)

a The wide-scan XPS spectra of Fe3O4 NPs before adsorption. b The wide-scan XPS spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of HEDP c The wide-scan XPS spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of PO43−. d Fe2p spectra of Fe3O4 NPs before adsorption. e Fe2p spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of HEDP. f Fe2p spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of PO43−.

a P2p spectra of Fe3O4 NPs before adsorption b P2p spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of HEDP c P2p spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of PO43− d O1s spectra of Fe3O4 NPs before adsorption e O1s spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of HEDP f O1s spectra of Fe3O4 NPs after adsorption of PO43−.

Adsorption mechanisms

XPS analysis

To elucidate the adsorption mechanism of Fe3O4 NPs for HEDP, XPS characterization was performed. The survey spectra, as shown in panel (a), (b), and(c), display four peaks at 285, 530, and 710 eV, corresponding to C1s, O1s, and Fe2p, respectively. Panels (d), (e), and (f) present the high-resolution Fe2p XPS spectra of Fe₃O₄ before and after adsorption. The spectra exhibit characteristic peaks at 710.3 eV and 723.6 eV for Fe(II), 728.5 eV and 733.5 eV for Fe(III), as well as satellite peaks at 714.2 eV and 718.2 eV, further confirming the successful synthesis of Fe3O4 NPs. A comparison of the Fe2p peaks before and after adsorption reveals no new peaks but shows notable shifts, indicating the interaction of Fe3O4 NPs during the adsorption process.

The XPS spectra post-adsorption reveal a P2p peak. The high-resolution P2p spectrum Fig. 8a shows a characteristic peak at 133.3 eV corresponding to Fe-O-P31, confirming the adsorption of HEDP and PO43− onto Fe₃O₄. The survey spectra before and after adsorption show a 10.9% increase in the O1s peak area. The measured spectra before and after adsorption showed that the peak area of O1s increased by 10.9% and 9.5%, the proportion of Fe-O(O2−) decreased, and the proportion of OH− increased. This suggests an increase in the proportion of surface -OH, indicating the formation of Fe-O-P inner complexation through -OH and O-P between orthophosphate and HEDP32.

DFT analysis

The aforementioned pattern indicates that the adsorption of organic phosphorus and orthophosphate predominantly occurs through chemical adsorption mechanisms. The efficacy of adsorption for orthophosphate and organic phosphorus under acidic conditions significantly surpasses that observed under alkaline conditions. Consequently, to facilitate a comparative analysis of the adsorption effects of Fe3O4 NPs on HEDP and PO43−, The CASTEP module within the Materials Studio (MS) software was employed to optimize the energy and structural configuration of the specific system; furthermore, the adsorption characteristics of HEDP and PO43− were systematically investigated to compute the maximum adsorption energy. Its calculation formula is as follows:

In the formula (8), Eads represents the adsorption energy, E1 represents the total energy of the optimized phosphate, E2 represents the total energy of the optimized Fe3O4 molecule, and E represents the total energy of the system after the combination of phosphate and Fe3O4.

In order to better simulate the calculation, the optimized configurations of Fe3O4 molecule, HEDP molecule and phosphate are shown in the following Fig. 8. The Table 3 illustrates the adsorption characteristics of various phosphates in conjunction with Fe3O4.

The Fig. 8 illustrates notable differences in the adsorption energies of HEDP and PO4³− when associated with Fe3O4 molecules post-adsorption. The adsorption energy of HEDP bound to Fe3O4 NPs is measured at 298 eV, while the adsorption energy of PO4³− bound to Fe3O4 NPs is recorded at 274 eV. These findings indicate that the adsorption of HEDP onto Fe3O4 is more thermodynamically stable compared to that of PO4³−.

To elucidate the interaction points between Fe3O4 and HEDP as well as PO4³−, the electrostatic distribution was mapped, as illustrated in Fig. 9. The blue regions denote areas of low electron density, indicative of nucleophilic sites, while the red regions signify high electron density, also corresponding to nucleophilic sites. A continuous delocalized electron density is observed on the surfaces of both HEDP and PO43−, with negative electrostatic potential concentrated near the P-O bond, suggesting that the oxygen atom within the P-O bond may serve as a potential site for electrophilic attack33,34.

a The ESP mapping images of HEDP. b The ESP mapping images of PO43− (The red areas represent regions with negative electrostatic potential, while the blue areas represent regions with positive electrostatic potential). c, d The frontier orbital isosurface map of HEDP. e, f The frontier orbital isosurface map of PO43− (The yellow color represents the positive phase region of the wave function, while the blue color indicates the negative phase region of the wave function).

The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) represent the nucleophilic reaction site and the electrophilic reaction site of the molecule, respectively. The energy gap (Egap) is an important parameter for evaluating the adsorption process, reflecting the ability of electrons to transition from occupied orbits to empty orbits. As illustrated in the Fig. 9, the HOMO of both the HEDP molecule and the PO4³− ion is primarily localized around the oxygen atom, whereas the LUMO is predominantly situated near the phosphorus atom. The energy gap of HEDP is measured at 5.2 eV, while the energy gap of the PO4³− ion is recorded at 7.88 eV. The higher the energy gap, the lower the possibility of electron transition35.

P removal in actual municipal sewage by Fe3O4 NPs

It was most convincing to explore the treatment efficiency of Fe3O4 NPs for the actual phosphorus-containing wastewater. The concentrations of TP and PO43− in the actual municipal sewage were 2.80 mg/L and 2.52 mg/L, respectively. As shown in Fig. 10, it was evident that the removal of TP or inorganic P was significantly enhanced, accompanied by the increase of adsorbent dosage, achieving a high removal rate of 98.5% and 95.6% at 1.2 g/L of Fe3O4 NPs, respectively. Meanwhile, organic P were almost completely removed, and the residual phosphorus in the wastewater was mainly a small amount of inorganic P (IP). When adding 1.0 and 1.2 g/L of Fe3O4 NPs, the residual concentration of TP reduced to 0.23 and 0.15 mg/L, respectively, meeting the discharge standard of major water pollutants for municipal wastewater treatment plants in Zhejiang Province (DB 33/2169-2018). Moreover, these experiments indicated that using Fe3O4 NPs as an adsorbent to simultaneously remove organic and inorganic P is a promising method to treat actual wastewater. Their superparamagnetic properties allowed for easy separation from the treated wastewater under an external magnetic field, further enhancing the feasibility of their use in large-scale wastewater treatment processes. This not only ensured efficient phosphorus removal but also simplified the recovery of phosphorus resources, making Fe3O4 NPs a promising candidate for sustainable wastewater treatment and resource recovery applications.

Discussion

The individual and simultaneous adsorption of organic phosphonate (HEDP) and orthophosphate (PO43−) by Fe₃O₄ NPs were systematically explored. The adsorption rate and capacity of HEDP were higher in the single system, and remarkable competitive adsorption existed between HEDP and PO43− on the Fe₃O₄ NPs. The HEDP was the predominant species in the competitive adsorption, which severely suppressed PO43− adsorption. pH and the co-existing ions (e.g.Cl−, SO42−, NO3−, Mg2+, and Ca2+) had no significant effect on HEDP and PO43− adsorption, whereas the presence of HCO3−/CO32− markedly suppressed the removal of HEDP and PO43−. The adsorption mechanisms were primarily driven by the combined effect of electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and coordination complexation. DFT calculations demonstrated that the higher adsorption energy of HEDP-Fe3O4 resulted in the predominant species of HEDP in competitive adsorption, which were in excellent agreement with the experimental data. The material exhibited robust adsorption performance even after five cycles of adsorption-desorption regeneration. Moreover, Fe₃O₄ NPs demonstrated effective phosphorus removal from actual municipal sewage containing organic and inorganic P. These characteristics highlighted its promising potential for practical applications.

Methods

Chemicals and Fe3O4 NPs synthesis

The primary chemicals used in this study were provided by National Group Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd., including heptahydrate ferrous sulfate (FeSO₄·7H₂O), anhydrous ethanol (C₂H₅OH), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrochloric acid (HCl), hexahydrate ferric chloride (FeCl₃·6H₂O), hydroxy ethane diphosphonic acid (HEDP), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4), potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), potassium antimonate tartrate (C8H4K2OSb2), ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate ((NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O). All reagents used were of analytical grade, while deionized water was consistently employed throughout the experiments.

The Fe3O4 NPs used in the experiments were synthetized as follows: firstly, 0.1 mol of FeSO₄·7H₂O and 0.2 mol of FeCl₃·6H₂O were dissolved in 200 mL of deionized water at 40 °C until complete dissolution was achieved. Next, in order to adjust the pH to a range between 10 and 11, a 3 mol/L NaOH solution was added dropwise. After the reaction, leave to stand for 24 h. Subsequently, the solid phase is separated through filtration. The solid was then washed with anhydrous ethanol, followed by water. Finally, the solid was dried at 75 °C, ground, and sieved through a 200-mesh screen to yield magnetite powder.

Characterization of Fe3O4 NPs

The structural analysis of Fe3O4 NPs was performed using a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker Corporation, Germany). The scanning range is 5–90°, with a scanning speed of 2° per minute. The morphology and size of Fe3O4 Nps were examined using a scanning electron microscope. The magnification is 5000 times (SEM, ZEISS Sigma 300, Germany). The specific surface area of Fe3O4 NPs particles was measured using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 surface area analyzer (BET, Micromeritics, USA). The specific surface area was determined by nitrogen adsorption-desorption. The magnetic strength of Fe3O4 NPs was measured using a LakeShore 7404 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, LakeShore, USA). The testing was conducted at a room temperature of 25 °C and a magnetic field strength of ±2 T. The chemical bonding distribution of Fe3O4 NPs was analyzed using a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, Thermo Scientific, USA). The elements tested include carbon (C), oxygen (O), phosphorus (P), and iron (Fe). Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the Fe3O4 NPs were recorded using an infrared spectrometer(FTIR, Bruker, Germany). The functional groups were identified by measuring the absorbance. The surface charge of the Fe3O4 NPs was determined using a zeta potential analyzer.

Adsorption experiments

Mixing 100 mL of aqueous P solution (adsorbate) with a specified amount of Fe3O4 NPs (adsorbent). The objective was to investigate the influence of Fe3O4 NPs dosage, pH, reaction time, and pollutant concentrations on the adsorption of HEDP and PO43− in different P systems. Once equilibrium was reached, the concentration of phosphorus was determined following the filtration of the sample. Each experiment was conducted in triplicate to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The effect of adsorbent dosage was examined by adding varying amounts of Fe3O4 NPs (0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04, 0.05, 0.06, and 0.08 g) to 100 mL of single HEDP or PO43− solution (1 mg-P/L). The mixture was shaken for 12 h at 150 rpm and 298 K to achieve apparent equilibrium. To assess the influence of pH, the experiment was conducted within a pH range of 3 to 11, with a Fe3O4 NPs dosage of 0.4 g/L (0.04 g to 100 mL P solution). The pH was adjusted prior to adsorption using HCl and NaOH solutions. Examine the influence of competing ions on the adsorption process, common cations (Ca2+ and Mg2+) and anions (Cl−, SO42−, NO3−, and HCO3−)were individually added at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 mM to the PO43− or HEDP solution.

In order to evaluate the kinetic characteristics, 0.4 g of Fe3O4 NPs were added into 1 L of HEDP or PO43− solution with a mechanical stirrer in single systems. The concentrations of P in the solution were 1, 5, and 10 mg/L, respectively. 0.4 g of Fe3O4 NPs were added into 1 L of HEDP and PO43− solution with a mechanical stirrer in binary P systems. Samples were collected at different time intervals, filtered, and subsequently analyzed for phosphorus concentration. Pseudo-first/second-order models were used to evaluate adsorption kinetics36.

where qe (mg/g) is adsorption capacity at equilibrium; qt (mg/g) is adsorption capacity at each time; k1 (min−1) and k2 (g/(mg·min)) are pseudo-first rate constant and second-order rate constant.

The experiments for the adsorption isotherm were conducted similarly to those in the single P system, with the only differences being that the initial concentrations of HEDP or PO43− solutions ranged from 0 to 30 mg-P/L, and the temperatures were set at 298, 308, and 318 K. For the binary P system, the initial concentrations of HEDP and PO43− solutions also ranged from 0 to 30 mg-P/L, but the temperature was maintained at 298 K. The equilibrium adsorption capacity (qₑ) of the adsorbent and the corresponding equilibrium concentration (Cₑ) in solutions with varying concentrations were determined and subsequently modeled using the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherms, as outlined below37:

where Ce (mg/L) is equilibrium concentration in solution; KF (mg1−1/n L1/n gadsorption capacity at equilibrium1) is fluorescence constant; n is heterogeneity factor; qmax (mg/g) is maximum adsorption; qe (mg/g) is adsorption capacity at equilibrium; KL (g/L) is Langmuir constant.

The thermodynamic data of adsorption thermodynamics were fitted according to the thermodynamic formula. The thermodynamic formula is as follows:

where ΔG (kJ/mol) is the Gibbs free energy; ∆H (kJ/mol) is the enthalpy; ΔS (J/(mol·K)) is the entropy; R is the gas molar constant, 8.314 J/(mol·K); and T is the absolute temperature, K.

After Fe3O4 Nps have removed HEDP and PO43− from the aqueous solution, a desorption-regeneration study was performed. The adsorbed Fe3O4 Nps were separated from the solution using filter paper, then immersed in a 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution. After a 2 h reaction period to facilitate phosphorus release, the mixture was subjected to solid-liquid separation. The Fe3O4 Nps were then washed with ultrapure water until the wash solution approached neutrality. The cleaned Fe3O4 Nps were then reintroduced into a 1 mg/L HEDP and PO43− solution and allowed to react for 4 h. This procedure was repeated four times to evaluate the renewable utilization performance of Fe3O4 Nps.

Experiments of P removal in the actual sewage were conducted by adding Fe3O4 Nps into the influent of a certain municipal sewage treatment plant in Zhejiang Province, China. The water quality of the tested sewage was as follows: pH = 6.5, total P (TP) = 2.80 mg/L, [PO43−] = 2.52 mg/L, total N (TN) = 23.4 mg/L, SS = 62.3 mg/L. Specifically, different masses of Fe3O4 Nps (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.5, and 2.0 g) were added into 1 L of the tested sewage and stirred at 150 rpm and 298 K for adsorption experiments. After a reaction period of 12 h, the residual concentrations of TP and inorganic P (IP) were measured for each sample in order to evaluate the P removal performance of actual wastewater.

Analytical methods and density functional theory (DFT) calculations

The concentrations of P in water samples were determined using the molybdenum blue method. The concentration of HEDP was calculated as the difference between the total phosphorus and PO43− concentrations38,39.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Materials Studio software, providing insights into the adsorption mechanisms at the molecular level.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

The codes generated and/or used during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

04 August 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00501-2

References

Wang, S. et al. Occurrence and transformation of phosphonates in textile dyeing wastewater along full-scale combined treatment processes. Water Res. 184, 116173 (2020).

Rajoria, S., Vashishtha, M. & Sangal, V. K. Review on the treatment of electroplating industry wastewater by electrochemical methods. Mater. Today. Proc. 47, 1472–1479 (2021).

Rott, E. et al. Removal of phosphonates from synthetic and industrial wastewater with reusable magnetic adsorbent particles. Water Res. 145, 608–617 (2018).

Zhou, Y., Lin, F., Wang, X., Wang, H. & Xue, B. Three-dimensional porous chitosan gel microspheres loaded with Ni and La for the treatment of inorganic and organic phosphorus in the water environment. J. Water Process. Eng. 63, 105476 (2024).

Shao, Q. et al. Selective sorption of organic phosphonate HEDP by steel slag: Efficiency and mechanism. Process Saf. Environ. 186, 645–655 (2024).

Lei, Y., Saakes, M., van der Weijden, R. D. & Buisman, C. J. Electrochemically mediated calcium phosphate precipitation from phosphonates: Implications on phosphorus recovery from non-orthophosphate. Water Res. 169, 115206 (2020).

Huang, N. et al. Ozonation of phosphonate antiscalant 1-hydroxyethane-1, 1-diphosphonic acid in reverse osmosis concentrate: Kinetics, phosphorus transformation, and anti-precipitation property changes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 297, 121385 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Wang, P., Che, H., Liu, B. & Ao, Y. Effective degradation of organophosphorus pesticide by photo-Fenton and in-situ recovery/utilization of the generated phosphorus: Dual function of iron ions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 344, 127123 (2024).

Xiao, Z. et al. UV-activated calcium peroxide system enables simultaneous organophosphorus degradation, phosphate recovery, and carbon fixation. J. Hazard. Mater. 478, 135582 (2024).

Arnaldos, M. & Pagilla, K. Effluent dissolved organic nitrogen and dissolved phosphorus removal by enhanced coagulation and microfiltration. Water Res. 44, 5306–5315 (2010).

Li, C., Yang, Q., Lu, S. & Liu, Y. Adsorption and mechanism study for phosphonate antiscalant HEDP removal from reverse osmosis concentrates by magnetic La/Zn/Fe3O4@ PAC composite. Colloid. Surf. A 613, 126056 (2021).

Petzoldt, C. S., Lezcano, J. P. & Moreda, I. L. Removal of orthophosphate and dissolved organic phosphorus from synthetic wastewater in a combined struvite precipitation-adsorption system. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8, 103923 (2020).

Pourshadlou, S., Mobasherpour, I., Majidian, H. & Salahi, E. Facile preparation of bentonite/nano-gamma alumina composite as a cost-effective adsorbent for Ca2+ removal from aqueous solutions. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 127, 496–508 (2023).

Yang, S., Wang, C., Li, B., Chen, H. & Wang, J. Removal of Pb2+ from aqueous solution using an MgO nano-hybridized magnetic biochar from spent coffee grounds. Chem. Phys. Lett. 833, 140894 (2023).

Zhou, Z., Huang, L., Wang, H. & Chen, Y. Efficient removal of cadmium and lead in water by using nano-manganese oxide-loaded hydrochloric acid pretreated biochar. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 113548 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Simultaneous removal of dissolved inorganic and organic phosphorus by magnetic α-Fe2O3/LaOCl composites: Performance, mechanisms and applicability. Sep. Purif. Technol. 348, 127814 (2024).

Ren, J., Li, N., Wei, H., Li, A. & Yang, H. Efficient removal of phosphorus from turbid water using chemical sedimentation by FeCl3 in conjunction with a starch-based flocculant. Water Res. 170, 115361 (2020).

Li, C., Yang, Q., Liu, D., Nie, H. & Liu, Y. Removal of organic phosphonate HEDP by Eu-MOF/GO composite membrane. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 106895 (2021).

Li, C., Yang, Q., Nie, H., Liu, D. & Liu, Y. Adsorption removal of organic phosphonate HEDP by magnetic composite doped with different rare earth elements. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 9, 100221 (2022).

Wan, J. et al. Insights into simultaneous adsorption of orthophosphate (PO43−) and 1-hydroxyethane 1, 1-diphosphonic acid (HEDP) by kaolin/lanthanum carbonate composites: Experimental analysis and DFT calculations. Chem. Eng. J. 476, 146664 (2023).

Shao, Q. et al. Zirconium-loaded zeolite composites for selective sorption of 1-hydroxyethylidene-1, 1-diphosphonic acid (HEDP) from water: performance and mechanism. Process Saf. Environ. 185, 153–163 (2024).

Yang, X., Wang, B. & Cheng, F. Adsorption performance on tetracycline by novel magnetic adsorbent derived from hydrochar of low-rank coal and sewage sludge. Sep. Purif. Technol. 330, 125482 (2024).

Kumar, N. & Narayanasamy, S. Toxicological assessment and adsorptive removal of lead (Pb) and Congo red (CR) from water by synthesized iron oxide/activated carbon (Fe3O4/AC) nanocomposite. Chemosphere 294, 133758 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. Phosphate removal from water using freshly formed Fe–Mn binary oxide: adsorption behaviors and mechanisms. Colloid. Surf. A 455, 11–18 (2014).

Song, H. J., You, S., Jia, X. H. & Yang, J. MoS2 nanosheets decorated with magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles and their ultrafast adsorption for wastewater treatment. Ceram. Int. 41, 13896–13902 (2015).

Wei, J., Meng, X., Wen, X. & Song, Y. Adsorption and recovery of phosphate from water by amine fiber, effects of co-existing ions and column filtration. J. Environ. Sci. 87, 123–132 (2020).

Irfan, I., Inam, M. A. & Iftikhar, R. Comparative phosphate sorption and recovery potential of mono and bimetallic iron-lanthanum impregnated biochar derived via co-pyrolysis of sewage sludge and wheat straw: Highly effective phosphatic fertilizer. J. Water Process. Eng. 66, 106110 (2024).

Pap, S. et al. Lanthanum and cerium functionalised forestry waste biochar for phosphate removal: Mechanisms and real-world applications. Chem. Eng. J. 494, 152848 (2024).

Mpatani, F. M. et al. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous medium by citrate modified bagasse: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic study. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 11, 100463 (2020).

Giles, C. H. Studies in adsorption: Part X1. A system of classification of solution adsorption isotherms, and its use in diagnosis of adsorption mechanisms and in measurement of specific surface areas of solids. J. Chem. Soc. 111, 3973–3993 (1960).

Debord, J., Harel, M., Bollinger, J. C. & Chu, K. H. The Elovich isotherm equation: Back to the roots and new developments. Chem. Eng. Sci. 262, 118012 (2022).

Xing, B., Zhao, B., Liu, M., Graham, N. J. & Yu, W. The influence of crystal structure and formation path of precursor on phosphate adsorption during oxidation-hydrolysis phase transition of siderite. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133358 (2022).

Wan, J., Wu, B. & Lo, I. M. Development of Fe0/Fe3O4 composites with tunable properties facilitated by Fe2+ for phosphate removal from river water. Chem. Eng. J. 388, 124242 (2020).

Mirzapour, M. & Akhlaghian, F. Core/shell magnetic nanoparticles of Fe3O4/MnxZnyFe3–x–yO4 for phosphate adsorption from water: effects of adsorbent composition using response surface methodology. Desalin. Water Treat. 137, 114–124 (2019).

Ji, L., Yin, C., Chen, X., Liu, X. & Zhao, Z. Hydrogen peroxide coordination-calcium salt precipitation for deep phosphorus removal from crude sodium tungstate solution. Hydrometallurgy 91, 105189 (2020).

Lagergren, S. About the theory of so-called adsorption of soluble substances. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar 24,1–39 (1898).

Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 40, 1361–1403 (1918).

Men, J. et al. Preparation of poly (sodium 4-styrene sulfonate) grafted magnetic chitosan microspheres for adsorption of cationic dyes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 181, 810–823 (2021).

Rott, E. et al. Removal of phosphonates from synthetic and industrial wastewater with reusable magnetic adsorbent particles. Water Res. 145, 608–661 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Ningbo Municipal Public Welfare Science and Technology Plan Project (2022S119) and the Project entrusted by Government Department (HK2022000234).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yubo Liu: writing—original draft, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation. Min Yao: writing—review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, data curation, conceptualization. Zhihao Jin: visualization, methodology, data curation. Yun Zhang: methodology, data curation, conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Yao, M., Jin, Z. et al. Simultaneous adsorption of organic phosphonate and orthophosphate from municipal sewage on nanoparticle Fe3O4 with molecular simulation. npj Clean Water 8, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00453-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00453-7