Abstract

Data-driven models often neglect the underlying physical principles, limiting generalization capabilities in water distribution systems (WDSs). This study presents a novel spatio-temporal graph physics-informed neural network (ST-GPINN) for water quality prediction in WDSs, integrating hydraulic simulations, physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), and graph neural networks (GNNs) to capture dynamics and graph-based network connectivity while approximating partial differential equations (PDEs). ST-GPINN discretizes WDSs using virtual nodes to enhance spatial granularity, employs an Encoder-Processor-Decoder architecture for predictions. Validated on Network A (a small-scale network with 9 junctions and 11 pipes) and Network B (a real large-scale WDS with 920 junctions and 1032 pipes), ST-GPINN outperforms others, achieving a MAE of 0.0073 mg/L, RMSE of 0.0121 mg/L, and R2 of 88.91% in Network A, and a MAE of 0.008 mg/L, RMSE of 0.0098 mg/L, and R² of 98.91% in Network B. Its scalability and accuracy highlight ST-GPINN’s potential for water quality predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water quality is crucial for ensuring the safety and health of populations in water distribution systems (WDSs)1,2,3. The ability to continuously monitor and assess water quality allows authorities to detect potential contaminants, mitigate risks, and promptly respond to emergencies. Moreover, effective water quality management contributes to maintaining chlorine residual concentrations, thereby preventing pollution during water transport4,5. As urbanization and industrialization progress, the complexity of WDSs increases, intensifying the need for accurate water quality prediction.

Traditionally, water quality calculations in WDSs have relied on the finite difference method, with one of the most widely used tools being the Environmental Protection Agency Network Evaluation Tool (EPANET), hydraulic simulation software developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency6. EPANET, which applies the global gradient algorithm (GGA)7 and the Lagrangian transport algorithm (LTA)8,9, is designed to simulate the hydraulic and water quality behavior in networks offering efficient performance for extended-period simulation (EPS)10. The LTA is a time-based approach proposed by refs. 11,12 that uses discrete volume elements to estimate the water quality transport process using Eq. 1 and the mixing process at nodes by Eq. 213. The process of LTA is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Where \({C}_{i}^{L}(x,t)\) is the concentration in link \(i\) at distance \(x\) and time \(t\); \({u}_{i}\) is flow velocity; \(r\) is the rate of reaction that is a function of concentration, containing pipe wall and bulk phases.

Where, \({C}_{j}^{N}(t)\) is the concentration at node \(j\) and time \(t\); \({I}_{j}\) represents the set of links flowing into node \(j\); \({Q}_{l}(t)\) is the flow from link \(l\) to node \(j\) at time \(t\); \({C}^{L}({L}_{l},t)\) is the concentration of link \(l\) flowing into node \(j\) at time \(t\); \({L}_{l}\) is the length of link \(l\); \({Q}_{j,{ext}}(t)\) and \({C}_{j,{ext}}(t)\) are the flow and concentration from outside to node \(j\), or from node \(j\) to outside at time \(t\).

Although EPANET is widely recognized and serves as a standard for water quality modeling, the LTA suffers from relatively low computational efficiency, especially in large-scale networks. As the size of the WDS increases or the time step decreases, EPANET’s computational efficiency declines, making real-time analysis increasingly difficult. This is primarily because the partial differential equations (PDEs) in Eq. 1 that govern water quality lack closed-form analytical solutions. Therefore, there is a need to develop alternative models that can integrate physical laws and topological information to maintain accuracy and improve efficiency.

In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and Internet of Things (IoT)-based approaches have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional water quality modeling14,15. Deep learning (DL) frameworks, a subset of AI techniques, can learn intricate patterns in data by employing multiple layers of abstraction. This hierarchical structure enables them to mimic the human brain’s architecture16. DL includes models such as deep belief networks (DBN)17, convolutional neural networks (CNN)18, and recurrent neural networks (RNN)19, among others. These models could effectively improve the computational efficiency of water quality prediction20. For instance, Saeed et al. employed the CNN model, clockwork RNN, and M5 Model Trees to enhance the accuracy of water quality parameter predictions21. Similarly, Ehteram et al. applied Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to forecast the water quality index, demonstrating their effectiveness in capturing temporal dependencies in water quality data22. However, these models are inherently data-driven and do not account for the physical principles governing hydraulic states and contaminant transport in WDSs.

Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) have gained attention for their ability to integrate physical laws with DL23. PINNs embed principles of physics, such as conservation equations or diffusion models, directly into the neural network training process, yielding a hybrid modeling approach that respects the governing physical constraints. Several studies have successfully applied PINNs to WDS modeling, showcasing their ability to solve inverse problems, optimize hydraulic and water quality calculations, and improve the overall accuracy of system modeling. For instance, Ashraf et al. presented a PINN model to efficiently emulate hydraulic state estimation in WDSs24. This model significantly reduces hydraulic computation times compared to traditional simulators like EPANET while maintaining high accuracy, making it a promising tool for WDS planning and optimization. Daniel et al. proposed a universal surrogate model to predict water quality in WDSs25. This model aims to bypass spatial discretization challenges by employing a PINN to predict water quality parameters across any WDS, providing a more efficient and universally applicable solution for water quality predictions.

While PINNs hold significant promise, their application to WDSs still faces some challenges. These include difficulties in training the model on complex topologies and limitations in scalability for large-scale networks. Additionally, the lack of consideration for spatial-temporal dependencies limits the model’s potential to capture real-world dynamics. Another notable limitation of PINNs is that they typically solve one pipe segment at a time in a sequential manner, and thus cannot model the entire network topology. For a WDS with \(N\) links, \(N\) separate PINN models would need to be trained, which increases computational complexity and reduces the model’s efficiency.

To address these issues, graph-based models like graph neural networks (GNNs) have been proposed to incorporate the spatial relationships between network components26,27. Unlike traditional models that treat each pipe or node as an independent unit, GNNs model the WDS as an integrated graph structure, enabling information to propagate along connected edges. This enables the model to capture long-range dependencies, dynamic flow interactions, and contamination spread paths that are difficult to represent using conventional numerical schemes. Recent advancements in GNN applications for water quality predictions have shown promising results. Salem et al. proposed both static and dynamic GNN prediction models for chlorine levels in real WDSs, demonstrating high accuracy across various sensor configurations28. Li et al. utilized a gated graph neural network (GGNN) incorporating hydraulic flow and network topological information for real-time water quality forecasting5. In particular, spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks (ST-GCNs)29,30 can help capture both spatial and temporal dependencies in nodes and links, enhancing the model’s ability to predict water quality changes over time31. Integrating PINNs with GNNs would make it possible to obtain more accurate and efficient water quality predictions. The GNN component captures spatial dependencies across the network, while the PINN component incorporates governing physical laws, resulting in a hybrid model that leverages the strengths of both approaches.

Therefore, this paper proposes a novel method, spatio-temporal graph physics-informed neural network (ST-GPINN), for predicting water quality in WDSs by combining the strengths of PINNs with the spatial and temporal modeling capabilities of GNNs. Experimental results demonstrate that the ST-GPINN model, through integration with EPANET hydraulic simulation and a physics-informed loss function, achieves superior performance in water quality predictions. The model learns a physically consistent representation, providing a robust and adaptive solution for water resource management.

Results

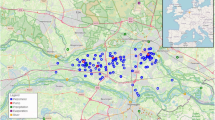

Two case studies are employed to verify the practicability of ST-GPINN. Network A, shown in Fig. 2, is first applied. The network has 9 junctions, 11 pipes, one pump, and one reservoir. The total average demand is 69.40 L/s. The chlorine concentration in the reservoir is set to\(\,{C}_{{bc}}=1.0\) mg/L and the \({Pattern}(t)\) is fixed to 1 in each time step. The initial concentrations of 9 junctions are set to 0.5 mg/L. Assuming water quality sensors are installed at all 9 junctions, these junctions are treated as observed nodes. The corresponding observations are used to compute the data loss term \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{Data}}}\) in the loss function defined by Eq. 20. Network B, a large-scale case study, is conducted using the WDS of City F, located in southern China2,32,33. This network has 920 junctions, 1032 pipes, six pumps, and one reservoir. The total system demand ranges from a minimum of 956.64 L/s to a peak of 2,408.69 L/s. The topology of WDS is illustrated in Fig. 3. The chlorine concentration in the reservoir is set to\(\,{C}_{{bc}}=1.0\) mg/L, and the \({Pattern}(t)\) is fixed to 1 in each time step, and the initial concentrations of 920 junctions are set to 0.5 mg/L.

The experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel i7-13700K CPU, 128 GB DDR5 RAM, a 1 TB Intel SSD, and an RTX 4060 GPU. The operating system is Ubuntu 22.04, and the development environment includes Visual Studio Code 1.81.0 and Python 3.9. In addition, the EPANET-OWA toolbox is employed to process hydraulic calculations34. The time interval for hydraulic calculations in the EPS process is set to one hour, with a total simulation duration of 24 h. In the EPANET-based water quality simulation, the second-order Rosenbrock method is employed for numerical integration35. The hydraulic conditions are assumed to be constant or pre-determined, and the water quality simulation is conducted independently, without feedback from the water quality results (chlorine concentrations) to the hydraulic model. The water quality simulation time step is set to \(\varphi =300{s}\). The relative tolerance of the water quality solver is specified as 0.01. The pipe bulk reaction coefficient is set to –0.5, the pipe wall reaction coefficient to –1.0, and the reaction order to \(n=1\).

Network A

The network is first discretized into a series of segments, each with a length of \(\sigma\)=100 ft (30.48 m). This segmentation ensures that the spatial resolution is sufficient for capturing localized variations in water quality properties. At the boundaries of each segment, virtual nodes are inserted to improve the granularity of the network representation. These virtual nodes are assigned zero water demand and initialized with zero chlorine concentration. To calculate the elevation of these virtual nodes, the linear interpolation method is applied. The elevations of the inlet and outlet nodes of each pipe segment serve as reference points for the interpolation. The result of discretization is shown in Fig. 4. Pipes 2 through 11 each have a length of 5280 ft, resulting in 52 inserted virtual nodes per pipe. Pipe 1, with a length of 10,530 ft, contains 105 inserted nodes. In total, 625 virtual nodes are added to the network.

After the network segmentation is completed, the next step is to perform hydraulic calculations. The original EPANET model is utilized for this purpose, and the hydraulic analysis is performed using the EPANET-Open Water Analytics (OWA) toolbox. These hydraulic calculations generate the flow velocities for each pipe segment, with results provided at each hourly time step. This step is essential for determining key flow conditions, including water velocity and pressure, as they directly influence the transport of water quality parameters within the system. The velocity results for each pipe at hourly intervals are summarized in Table S1. Comparative simulations in EPANET verify that the flow and pressure values at all original nodes remain unchanged, thereby preserving the physical fidelity of the refined graph structure.

Upon completion of the hydraulic calculations, the water quality simulation is performed. This fine temporal resolution allows the model to capture dynamic variations in water quality throughout the network. The simulation specifically targets 9 junctions, at which water quality predictions are generated at each time step. Since real-world sensor measurements at these junctions are unavailable, the water quality outputs from EPANET are adopted as surrogate ground truth values. These predictions are employed in calculating the supervised loss term during model training.

The hydraulic data and water quality conditions are integrated into the ST-GPINN model. For each pipe segment, relevant node features containing residual chlorine concentrations and node types (interior is 0 or boundary node is 1), edge features containing relative displacement and Euclidean distances, are extracted as input variables. These features represent the state of the system at the initial time step and provide critical context for the water quality prediction task. Additionally, the velocity of each pipe is incorporated as a feature for solving the PDE constraints.

Subsequently, these features are fed into the Encoder module of the ST-GPINN. The Encoder transforms this input information into high-dimensional embeddings (with a dimension size of 128), facilitating the model’s ability to learn spatial relationships among nodes and capture the hydraulic dynamics that govern contaminant transport36. The Encoder processes the feature vectors corresponding to each node and pipe segment and generates the initial representations of the system’s state.

Next, the embeddings produced by the Encoder are passed through the Processor module, which consists of 10 GNN layers. These layers are designed to capture both spatial dependencies and temporal interactions in the water quality data. The Processor aggregates information from neighboring nodes and previous time steps, updating the node states iteratively. At each iteration, the updated embeddings reflect spatial interactions among nodes and the evolving temporal patterns of water quality. Once the embeddings are updated in the Processor, they are passed to the Decoder module. The Decoder predicts the concentration at each node at the next time step using the final embeddings produced by the Processor. For each node \(i\), the predicted concentration \({C}_{i}(t+\varDelta t)\) at the next time step \(t+\varDelta t\) is computed.

The model iteratively processes the data in this manner for each time step, updating the water quality at each junction every 300 s. This process continues until the maximum simulation time is reached. At each time step, the predicted concentrations are compared against the reference EPANET simulation results, and the discrepancy is used to compute the total loss function. This loss function incorporates both data-driven loss terms, which measure the difference between the predicted and observed concentrations, and physics-informed loss terms (the \(\alpha\) is set to 0.3), which ensure that the model adheres to the physical laws governing advective transport and chemical reactions within the network.

Model parameters are optimized via backpropagation to minimize the total loss, thereby improving the accuracy of water quality predictions. The model is trained for 100 epochs, or until convergence is achieved, defined as reaching a loss value below 0.01 or exceeding the maximum allowed number of iterations. In the absence of observed sensor data, EPANET-calculated values are used as surrogate references to evaluate the final water quality results predicted by the ST-GPINN model at the 9 junctions. The objective of this comparison is not to replicate EPANET results, but rather to assess the predictive capability of ST-GPINN using simulation data as a benchmark. An illustrative example of the predicted chlorine concentration at Junction 2 over the 0–24 h simulation period is presented in Fig. 5, with results for other junctions summarized in Table S2.

To evaluate the performance of the ST-GPINN model, the predicted water quality values are compared with those obtained from the EPANET model, which are treated as the ground truth. The error metrics, including mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), are calculated to assess the prediction accuracy. Table 1 summarizes the comparison of these error metrics between the ST-GPINN predictions and the EPANET results, averaged over a 24-h simulation period.

The performance analysis of the ST-GPINN model reveals that it performs excellently at most junctions, with high R2 values (above 99%) for Nodes 2 through 9, indicating that the model captures almost all of the variance in water quality at these locations. The MAE and RMSE values for these nodes are consistently low, indicating that the model’s predictions are consistently close to the reference values. These results demonstrate that the model is highly effective for the majority of nodes, where water quality dynamics are stable and predictable.

However, node 1 presents a distinct challenge. Despite the relatively low MAE (0.0018 mg/L) and RMSE (0.0288 mg/L), the corresponding R2 value is notably low at 3.63%, indicating that the model fails to capture the variance in water quality at this location. The MAPE (0.35%) for node 1 also indicates a significant discrepancy between predicted and observed values. This is likely due to the unique hydraulic configuration at node 1, where it is connected directly to the water source via a pump with negligible pipe length. This setup introduces transient flow behaviors that are challenging for the model to resolve, thereby resulting in reduced predictive accuracy at this junction.

While these issues at node 1 suggest a limitation in the model’s ability to handle specific system dynamics, they exert minimal impact on the overall model performance. The high accuracy and consistency across the other nodes (especially those with R2 values above 99%) indicate that the model remains accurate in water quality across the network. The deficiencies observed at node 1 should be regarded as localized anomalies and do not substantially impair the overall predictive capability of the model. Therefore, the overall effectiveness of the ST-GPINN model in water quality prediction is preserved, with minor refinements warranted for special cases such as node 1.

To further assess the model’s performance during the training process, Fig. S1 illustrates the changes in train loss over the 100 training epochs. The loss function data demonstrates a compelling training performance for water quality prediction. Over the 100 iterations, the loss plummets from 23.5058 to approximately \(0.01\), a 99.92% reduction, indicating rapid optimization as the model captures the spatio-temporal dynamics and PDE constraints of the 9 junctions and 625 virtual nodes. The final loss approached the predefined threshold, indicating convergence of the training process. Fluctuations between 0.0159 and 0.3131, with occasional increases (e.g., iteration 13 from 0.0734 to 0.2320), reflect realistic gradient descent behavior, driven by the composite loss function balancing physics-informed and data-driven terms. These oscillations align with challenges in modeling complex WDS topologies and transient flows, particularly at junction 1, where lower R2 (3.63%) is noted due to its unique pump connection.

The rapid decline and subsequent stabilization of the loss around 0.022 (mean loss across iterations 51-100) further confirm the model’s convergence toward the 0.01 threshold by the 100th epoch, aligning with the high R2 values (>99%) achieved for junctions 2-9.

Above all, by combining hydraulic simulations with detailed water quality predictions and leveraging the ST-GPINN architecture, the model provides a robust framework for accurately forecasting water quality dynamics in WDSs. The iterative process of updating node states and integrating physical constraints ensures that the model produces reliable and physically consistent results, enabling better management and decision-making for Network A.

Network B

Network B is spatially discretized into a series of pipe segments, each with a length of\(\,\sigma =10{m}\). The result of the discretization is depicted in Fig. S2. A total of 51,502 virtual nodes are inserted into the network. Subsequently, hydraulic simulation is performed, and the resulting flow velocities for each pipe segment are summarized in Table S3. Then, the ST-GPINN is trained for 500 epochs or convergence is achieved, defined by either reaching a specified loss threshold (0.002 in this case) or completing the maximum number of iterations. The predicted chlorine concentration results are presented in Table S4.

Compared with the water quality by EPANET, the MAE, RMSE, and MAPE, are calculated to assess the prediction accuracy. The results are shown in Table S5. The ST-GPINN model demonstrates excellent performance in predicting water quality across Network B, achieving consistently low error metrics and high R2 values. The MAE value is 0.0080 mg/L, indicating that the predictions are close to the actual values. The RMSE value (0.0100 mg/L) further confirms that there are minimal large prediction errors. Meanwhile, the MAPE suggests the model’s predictions deviate by only about 3% on average. R2 values above 98.91% across most junctions indicate that the model effectively captures the majority of the variance in water quality dynamics. These results demonstrate the reliability of the ST-GPINN model for water quality predictions in large-scale networks.

The loss function demonstrates robust training performance over 500 epochs in Fig. S3, with the loss plummeting from an initial 2.23359 to a final value of approximately \(0.002\), achieving a 99.91% reduction. The final loss reaches the predefined threshold, indicating convergence. The rapid decline, particularly within the first 50 epochs, reflects effective optimization as the model captures spatio-temporal dynamics and satisfies PDE constraints across 920 junctions and 51,502 virtual nodes. Stabilization around 0.0022 (mean loss from epochs 51-100) and further convergence to below 0.002 by epoch 400 underscore the model’s robustness, supporting high R2 values (>95%) for most junctions, despite minor oscillations persisting due to the large-scale network’s complexity. Therefore, the consistently high performance indicates the model’s reliability and effectiveness in water quality predictions in large-scale networks.

Effect of pipe segment length

The segment length \(\sigma\) of links in WDSs has a significant impact on the accuracy and efficiency of the model. Shorter segments enable finer-grained modeling of water quality dynamics but require significantly more training time, whereas longer segments result in reduced accuracy.

To evaluate the influence of spatial resolution on model performance, experiments were conducted on Network A using pipe segment lengths ranging from 150 ft to 50 ft, in 10 ft decrements. As shown in Fig. 6a, decreasing the segment length consistently improved model accuracy across all evaluation metrics, including MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2. When using the coarsest segmentation (150 ft), the model yielded an MAE of 0.0085 mg/L and an RMSE of 0.0136 mg/L. As the segment length decreased, the prediction errors gradually declined, reaching an MAE of 0.0061 mg/L and an RMSE of 0.0107 mg/L at 50 ft. These improvements can be attributed to the finer granularity in spatial modeling, which allowed the ST-GPINN to better capture localized water quality variations. Furthermore, the R2 value improved steadily from 87.30% at 150 ft to 90.31% at 50 ft, indicating an increasing degree of agreement between model predictions and EPANET simulations.

However, this gain in predictive performance comes at a significant computational cost. As shown in Fig. 6b, the training time increased as the segment length decreased. For instance, the total training time for the 150 ft segmentation is 2142 s, while the time rose to 5432 s for the 50 ft configuration. This exponential increase in training time reflects the larger number of graph segments and the corresponding growth in computing complexity, which collectively escalates the overall computational burden.

Therefore, a classic trade-off between model precision and computational feasibility. While shorter segment lengths yield more accurate and physically consistent predictions, they introduce significant training overhead, which may not be practical in real-time or resource-constrained scenarios. From a practical perspective, the segmentation in the range of 100 ft appears to offer a favorable balance, achieving RMSE values below 0.0121 mg/L while maintaining training times under 3,941 s. These findings highlight the importance of carefully tuning the spatial granularity in the model for water quality prediction.

In Network B, the experiments are conducted using pipe segment lengths ranging from 50 m to 5 m, decreasing in 5 m increments. As shown in Fig. 6c, reducing the segment length consistently improved model accuracy across all metrics. Shorter segments improved accuracy metrics (MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2). At 50 m, the model achieved an MAE of 0.00921 mg/L and RMSE of 0.01156 mg/L; these decreased to 0.00792 mg/L and 0.00989 mg/L, respectively, at 5 m. The R2 value increased from 97.80% to 99.14%, reflecting better alignment with EPANET results, owing to the finer spatial granularity that more effectively captured localized water quality dynamics.

Meanwhile, shorter segments increased computational demands. Figure 6d shows training time growing from 52,710 s at 50 m to 102,845 s at 5 m, driven by heightened computational complexity in the larger network. This highlights a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. Short segments offer precise predictions but are computationally intensive, challenging for real-time applications. A segment length of 10 m balances accuracy (RMSE < 0.001 mg/L) with manageable training times (<100,000 s), optimizing performance for large-scale systems like Network B.

Impact of loss function coefficient

The coefficient α in the loss function plays a pivotal role in balancing the contribution of the physics-informed PDEs and the data-driven components. Higher α values emphasize physical consistency, ensuring that the model follows the expected physical laws. Lower α values, however, allow the model to focus more on fitting the data, which may lead to a loss in physical accuracy.

The impact of α on the ST-GPINN model’s performance in Network A is evaluated by varying α from 0.1 to 1.0 in 0.1 increments, with performance metrics including MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and R2. The results in Fig S4a demonstrate that α = 0.3 yields optimal performance, achieving the lowest errors (MAE = 0.0073 mg/L, RMSE = 0.0121 mg/L, MAPE = 0.97%) and highest R2 (88.91%), effectively balancing data-driven and physics-informed loss components. For α < 0.3, such as α = 0.1, metrics deteriorate significantly (MAE = 0.0085 mg/L, RMSE = 0.0145 mg/L, MAPE = 1.17%, R2 = 87.41%) due to insufficient enforcement of physical constraints, compromising model accuracy. Conversely, for α > 0.3, over-regularization leads to increased errors (e.g., MAE = 0.0093 mg/L, RMSE = 0.0166 mg/L, MAPE = 1.42%, at α = 1.0) and reduced R2 (86.41%), as the model overly prioritizes PDE compliance at the expense of data fitting. This parabolic trend underscores the critical role of tuning α to achieve an optimal trade-off between physical consistency and empirical accuracy in water quality predictions.

Similarly, in Network B, optimal performance is achieved at α = 0.3 in Fig. S4b. The model attained peak performance, with minimal errors (MAE = 0.008 mg/L, RMSE = 0.01 mg/L, MAPE = 3.11%) and the highest R2 (98.91%), effectively balancing data-driven and physics-informed loss components in this large-scale network. For α < 0.3, the model exhibited degraded performance, as inadequate physical regularization impaired accuracy. Conversely, values above 0.3 result in higher errors and lower R2 due to over-prioritization of PDE adherence, restricting data-driven flexibility.

Thus, α = 0.3 ensures that the model respects the underlying physical laws while still being flexible enough to fit the data accurately, which is critical for real-world applications, particularly in large-scale systems such as Network B.

Effect of time step size on water quality predictions

The time step size \(\varphi\) also plays a significant role in the ST-GPINN model, as it determines how frequently the PDE updates its predictions over time. Smaller time steps (100 s) provide a finer temporal resolution, allowing the model to capture fast fluctuations in water quality, but they also increase computational load. Larger time steps (3600 s) reduce computational time but might fail to capture important short-term variations, leading to a loss of accuracy.

The performance of the ST-GPINN model for Network A reveals a pronounced sensitivity to the time step Δt over a range of 100 s to 3600 s, as evidenced by the MAE, RMSE, MAPE, R2, and training time in Figs. S5a, b. The optimal performance occurs at Δt = 300 s, where MAE = 0.0073 mg/L, RMSE = 0.0121 mg/L, MAPE = 0.97%, R2 = 88.91%, and training time = 3941 s, indicating a balance between high accuracy and reasonable computational cost. This time step effectively captures the water quality dynamics critical for accurate predictions in Network A due to its accuracy. However, as Δt deviates from this optimum, accuracy metrics exhibit a steep parabolic trend, with MAE, RMSE, and MAPE increasing dramatically and R2 plummeting, particularly at larger time steps. At Δt = 3600 s, the model’s performance collapses, with MAE = 0.3128 mg/L, RMSE = 0.3614 mg/L, MAPE = 39.60%, and R² = 31.26%. These correspond to increases of 4285%, 2987%, and 4082% in error metrics and a 64.8% reduction in R2 compared to the optimal case, reflecting the model’s failure to capture transient water quality dynamics and rendering the predictions nearly unusable. This severe degradation underscores the critical need for an appropriate Δt to maintain temporal resolution in water quality modeling.

The trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency is evident. For Δt < 300 s, error metrics unexpectedly increase despite a doubling of training time, likely due to numerical instability or overfitting. Conversely, larger Δt values significantly reduce training time but at the cost of catastrophic accuracy loss, as coarse time steps fail to resolve dynamic behaviors. For practical applications, Δt = 300 s is recommended to optimize accuracy and computational cost.

In Network B, model performance across time steps from 100 s to 3600 s exhibits a sharp trade-off between accuracy and training efficiency in Fig. S5c, d. Optimal results are observed at Δt = 300 s, with MAE = 0.00787 mg/L, RMSE = 0.00985 mg/L, MAPE = 3.11%, R2 = 98.91%, and training time = 92230 s. For Δt < 300 s, accuracy slightly improves, but training time surges; for Δt > 300 s, errors escalate dramatically, reaching MAE = 0.2422 mg/L, RMSE = 0.2604 mg/L, MAPE = 28.82%, and R2 = 39.54% at Δt = 3600 s, a 3050%, 2607%, 921%, and 60% deterioration, respectively, rendering predictions unreliable, while training time drops to 7882 s. Compared to Networks A and B’s higher accuracy at smaller Δt and slower degradation reflects its complexity, but Δt = 300 s remains optimal, balancing accuracy and computational cost.

Thus, Δt = 300 s is recommended as the universal time step for both networks, ensuring reliable water quality predictions with efficient computation.

Robustness analysis

To evaluate the robustness of the ST-GPINN model under input uncertainty, we introduced the measurement noise model37 in networks A and B to simulate realistic errors from sensor noise. Three types of noise are introduced: (1) zero-mean Gaussian white noise with a specified standard deviation is applied to the pipe flow rates after the EPANET hydraulic simulation; (2) a similar Gaussian noise is added to the initial chlorine concentrations at source nodes; and (3) both of the above noise types are applied simultaneously at each perturbation level.

For flow rate perturbations, zero-mean Gaussian noise with standard deviations of ±3%, ±5%, and ±10% of the true values is directly added after the hydraulic simulation. The perturbed hydraulic and quality parameters are then used as inputs to the trained ST-GPINN model. For each noise type and level, we trained the ST-GPINN model independently three times with different random seeds to ensure statistical reliability. All models are trained using the same hyperparameters and training protocol. During testing, we used unperturbed hydraulic data as input and compared the predicted chlorine concentrations with the ground truth generated by EPANET under clean conditions. The average prediction performance (MAE, RMSE, and R²) in Networks A and B across three repeated trials for each noise type and level is shown in Table S6. In both networks, ST-GPINN maintained reasonable accuracy under ±3% noise, with an average MAE, RMSE of 0.0478 mg/L, 0.0585 mg/L in Network A, and 0.08 mg/L, 0.0981 mg/L in Network B. This indicates that the model is resilient to mild sensor perturbations. Error increased moderately in both networks as ±5% noise is added (MAE, RMSE reached 0.0735 mg/L, 0.0899 mg/L in Network A, and 0.0842 mg/L, 0.1031 mg/L in Network B). The degradation is significant with ±10% noise. Network A reached 0.0846 mg/L MAE, 0.1035 mg/L RMSE, while Network B experienced 0.1163 mg/L MAE, 0.1425 mg/L RMSE. These results verify that ST-GPINN is robust to common levels of measurement noise, particularly for noise within ±5%.

For initial water quality perturbations, zero-mean Gaussian noise with standard deviations of ±3%, ±5%, and ±10% of the true values is directly added to the chlorine concentrations at the source node. For each noise type and level, we trained the ST-GPINN model independently twice with positive and negative perturbations to capture symmetric effects. The average prediction performance (MAE, RMSE, and R²) in Networks A and B across three repeated trials for each noise type and level is shown in Table S7. In Network A, where the system size is relatively small, the model demonstrates high resilience to low-level noise. At ±3% perturbation, the average MAE and RMSE are only 0.0018 and 0.0022 mg/L, respectively, indicating negligible deviation from the baseline. As the noise level increases to ±5%, the errors rise slightly, with MAE reaching 0.0044 and RMSE 0.0054 mg/L. Under the highest noise level (±10%), the average MAE and RMSE grow significantly to 0.0146 and 0.0179 mg/L, respectively. These remain within an acceptable range, showing that the model retains satisfactory predictive performance even under considerable uncertainty in the initial conditions. Network B exhibits greater sensitivity to initial condition perturbations. At ±3% noise, the average MAE and RMSE already reach 0.0643 and 0.0787 mg/L, which is substantially higher than Network A under the same conditions. This discrepancy reflects the amplified effect of local perturbations in high-dimensional systems, where errors can propagate more diffusively. The degradation continues with increased noise: at ±5%, MAE and RMSE reach 0.1276 mg/L and 0.1563 mg/L, and at ±10%, they increase further to 0.1444 and 0.1769 mg/L.

The ST-GPINN model under combined noise conditions, where both hydraulic flow variables and initial water quality concentrations are simultaneously perturbed, is shown in Table S8. Three noise levels are considered (±3%, ±5%, and ±10%), with each level repeated across three random trials. For Network A, the model maintains relatively stable performance under ±3% combined noise, with an average MAE of 0.0552 mg/L and RMSE of 0.0676 mg/L. These errors represent a slight increase compared to the case of individual noise types. As the noise level increases to ±5%, average errors rise to 0.0855 mg/L MAE and 0.1046 mg/L RMSE, indicating a noticeable degradation in predictive accuracy. At the highest level of ±10% combined noise, the model still performs reasonably, with MAE and RMSE reaching 0.1041 and 0.1275 mg/L, respectively. In Network B, the impact of combined noise is significantly amplified. Even at ±3%, the average MAE reaches 0.1515 mg/L and RMSE 0.1856 mg/L, nearly three times higher than Network A under the same conditions. This trend escalates at ±5% (MAE = 0.2224 mg/L, RMSE = 0.2724 mg/L) and becomes most severe at ±10%, with the model reporting MAE = 0.2738 mg/L and RMSE = 0.3354 mg/L. These findings suggest that in large-scale WDSs, the compounding effect of noisy hydraulic and water quality inputs can severely challenge model generalizability.

Overall, the analysis supports the claim that ST-GPINN generalizes well under imperfect input, making it suitable for deployment in practical sensing environments. However, accuracy declines significantly under strong noise conditions (±10%), suggesting the need for future enhancements in noise-robust regularization techniques.

Embedding size and model depth selection

To validate the selection of embedding size and model depth, we conducted a series of experiments on Networks A and B using different configurations. The embedding size is varied among 64, 128, and 256 dimensions, while the number of GNN layers is tested at 6, 8, 10, and 12 layers. All other parameters were kept the same as those used in the case studies.

The model performance for each setting in terms of MAE, RMSE, and R2 on the validation dataset is shown in Table S9. For Network A, the results show that increasing either embedding size or model depth improved predictive accuracy. When the embedding size was fixed at 64, increasing the GNN layers from 6 to 12 reduced the MAE from 0.0080 to 0.0077 mg/L and improved the R² from 86.42% to 87.79%. A similar trend is observed at higher embedding sizes. The best performance is achieved with an embedding size of 256 and 12 GNN layers, yielding the lowest RMSE of 0.0114 mg/L and the highest R2 of 89.30%. While the 256-12 configuration slightly outperformed 256-10 on Network A, the gain in accuracy is not substantial. Considering training efficiency and generalization ability, the 256-10 configuration was selected, as it consistently performed well across networks while offering lower complexity and improved computational efficiency.

For Network B, the effect of embedding size and GNN depth is even more pronounced due to its larger scale and higher topological complexity. At an embedding size of 64, increasing the GNN layers from 6 to 12 reduced MAE from 0.0086 to 0.0082 mg/L and improved R2 from 97.00% to 98.79%. At an embedding size of 128, the model with 12 GNN layers achieved the best accuracy (MAE = 0.0081 mg/L, RMSE = 0.0097 mg/L, R2 = 99.29%). However, further increasing the embedding size to 256 did not bring additional benefits: although the model with 12 layers had the lowest RMSE (0.0095 mg/L), its R2 slightly dropped to 97.71%, indicating potential overfitting.

In both networks, configurations with an embedding size of 128 and 10 GNN layers consistently offered a strong balance between accuracy and stability. Although slightly better accuracy was achieved with 256 dimensions or 12 layers in Network A, the increased model complexity introduced greater training time and potential risks of overfitting. Therefore, we selected the 128-dimensional embedding and 10-layer GNN configuration as the default in ST-GPINN, based on its robust and efficient performance across diverse network sizes.

Comparison with other models

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed ST-GPINN model, a comparative analysis is conducted against four alternative models: ST-GCN, PINN, LSTM, and Backpropagation (BP). These models are evaluated based on their architectural characteristics, key parameters, and predictive accuracy using the case studies of Networks A and B.

The ST-GCN model29 is designed to capture spatio-temporal dependencies through five spatio-temporal blocks. Each block comprises graph convolutional layers for spatial feature extraction, coupled with a fully convolutional network (FCN) with a kernel size of 3 for temporal feature learning. The model employs 64 filters per block, utilizes the ReLU activation function, and is trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. Unlike ST-GPINN, ST-GCN does not incorporate any physical constraints into its learning process. The input to ST-GCN contains the node features (water quality time series) and the topological graph, while the output is the predicted water quality at each node in the next time step.

The PINN is a fully connected feedforward neural network that directly incorporates physical laws into its loss function. It consists of four MLP layers with 1024, 512, 256, and 128 neurons, respectively, and uses the Tanh activation function. The physics-informed loss follows the formulation given in Eq. 18, and the model is trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001.

In the context of the WDS, each pipe segment is trained independently using the PINN model. The training process follows a spatio-temporal sequence starting from the source node. For each pipe, the boundary condition is defined as the concentration at the upstream node, while the initial condition is consistent with that used in the ST-GPINN model. After training the model for a specific time step, the resulting node concentrations are used as the initial conditions for the subsequent time step. For example, in Network A, comprising 11 pipe segments over a 24-h period, training begins with the first-hour model for each of the 11 pipes in sequence, starting from the reservoir. Once completed, the predicted concentrations at the end of the first hour serve as the initial conditions to train the second-hour models for all pipe segments. This process continues iteratively, ultimately yielding 11 × 24 = 264 independently trained models. However, due to the large number of pipes in Network B, resulting in 1032 × 24 = 24,768 independently trained models, it is computationally infeasible to conduct PINN-based modeling for this network within the scope of the present study. Therefore, the PINN is applied only to Network A.

The LSTM model is a recurrent neural network designed for sequential data processing. It consists of three LSTM layers, each with 128 units, and includes a dropout rate of 0.2 to mitigate overfitting. The input to the LSTM model comprises node-level water quality time series, with a kernel size of 3 employed for temporal pattern extraction. The Tanh activation function is used, and the model is trained using the Adam optimizer at a learning rate of 0.001. Although LSTM performs well in time series forecasting, it lacks the ability to model spatial dependencies and physical constraints.

The BP serves as a baseline model, consisting of a multilayer perceptron with 4 hidden layers, each containing 1024, 512, 256, 128 neurons. The input features for the BP model consist of the node’s water quality time series, where a window size of 3 is used for temporal analysis. It utilizes the Tanh activation function and is trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001.

The iterations of all models are set to 100 epochs in Network A and 500 epochs in Network B. Model performance is evaluated on both Networks A and B using average performance metrics, including MAE, RMSE, MAPE, and R². The results are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3.

The ST-GPINN model exhibits superior performance in water quality prediction compared to alternative approaches, including ST-GCN, PINN, LSTM, and BP, across both Networks A and B. In Network A, ST-GPINN achieves the lowest MAE (0.0073 mg/L) and RMSE (0.0121 mg/L), MAPE (3.13%), and the highest R2 value (88.91%), indicating that it provides the most accurate predictions among the models tested. This can be attributed to the hybrid architecture of ST-GPINN, which combines graph-based modeling to capture spatial dependencies and PINN to ensure compliance with the physical laws governing water quality dynamics. By contrast, ST-GCN incorporates spatial graph features but lacks integration of physical constraints, resulting in moderately higher prediction errors, with an MAE of 0.0080 mg/L and an RMSE of 0.0130 mg/L. Furthermore, although the PINN model incorporates physics-based loss functions, it produces a higher RMSE of 0.0140 mg/L and a lower R2 of 85.43%. This reduced performance is primarily due to its limited capacity to capture spatio-temporal dependencies, as it lacks graph-based structures to represent node-level interactions within the network.

As tested on Network B, which is significantly more complex with 920 junctions and 1032 pipes, ST-GPINN continues to outperform the other models, with an MAE of 0.008 mg/L, RMSE of 0.0098 mg/L, and R2 of 98.91%. This model’s ability to capture both spatial and temporal dependencies, along with its integration of physical constraints, allows it to manage the increased complexity of Network B effectively. In contrast, alternative models such as ST-GCN, LSTM, and BP exhibit substantially degraded performance, with significantly higher error metrics across all evaluated indicators. Specifically, the ST-GCN model, yielding an MAE of 0.0174 mg/L and RMSE of 0.021 mg/L, underperforms in large-scale settings due to its lack of physics-informed mechanisms, which represents a notable limitation when modeling complex hydraulic and water quality interactions. The LSTM and BP models, as purely data-driven architectures lacking spatial dependency modeling, perform even worse. Their RMSE values reach 0.0542 mg/L and 0.0993 mg/L, respectively, with MAPE values of 7.05% and 16.21%, highlighting their limited capacity to generalize in complex network scenarios. This performance gap underscores the inherent limitations of traditional data-driven models in accurately predicting water quality within large-scale and structurally complex WDSs.

A critical factor contributing to the superior performance of ST-GPINN is its integration of physical constraints and data-driven learning components. The inclusion of PDEs ensures that the model’s predictions respect the governing physical laws of water flow and contaminant transport in the network, which is essential for accurate water quality modeling. In Network A, the integration of physical constraints via the PINN framework resulted in a slight improvement in model accuracy. However, the absence of spatio-temporal modeling ultimately limited its overall performance compared to ST-GPINN. The ST-GPINN is particularly advantageous when modeling complex systems with intricate spatial relationships between nodes, such as those found in WDSs.

Moreover, ST-GPINN demonstrates exceptional scalability, as evidenced by its performance in Network B. The large-scale network, with over 51,502 virtual nodes and 1,032 pipes, presents significant computational challenges. However, ST-GPINN continues to deliver robust results with MAE values ranging from 0.0001 to 0.0091 mg/L and R2 values above 94% across all nodes. This performance is a testament to the model’s ability to handle large networks efficiently. The integration of virtual nodes and the segmentation of the network into localized computational domains enable ST-GPINN to preserve high prediction accuracy.

Discussion

Two case studies validate its efficacy. ST-GPINN achieves superior performance, with MAE of 0.73%, RMSE of 1.21%, MAPE of 0.97%, and R² of 88.91% in Network A, and MAE of 0.80%, RMSE of 0.99%, MAPE of 3.13%, and R² of 98.90% in Network B. Comparative analysis with ST-GCN (MAE: 0.80% Network A, 1.74% Network B), PINN (MAE: 0.82% Network A), LSTM (MAE: 0.95% Network A, 3.81% Network B), and BP (MAE: 1.13% Network A, 7.58% Network B) confirms ST-GPINN’s superior accuracy and stability.

Based on the results, the following conclusions are drawn: (1) ST-GPINN effectively captures WDS connectivity and spatial-temporal dependencies while enforcing PDE-based physical constraints, ensuring high accuracy in small and large-scale systems; (2) Virtual node insertion and spatial discretization (100 ft in Network A, 10 m in Network B) enhance prediction granularity, resolving localized water quality variations; (3) The optimized loss function coefficient (α = 0.3) and time step (Δt = 300 s) balance data-driven and physics-informed components, achieving robust convergence with minimal errors.

However, the following limitations are identified: (1) ST-GPINN’s reliance on hydraulic data constrains its effectiveness under transient flow conditions, evidenced by poor performance at node 1 in Network A (R² = 3.63%), where numerical anomalies, such as zero-length links, impair simulation accuracy; (2) Retraining for different WDS topologies reduces generalizability, requiring significant computational resources for diverse networks. Also, any changes in the topology, such as adding, removing, or modifying pipes and nodes, require retraining the entire model. ST-GPINN is currently constrained to application within fixed network structures; (3) In the absence of real-world observations data, EPANET results serve only as a surrogate benchmark. Observational data should be incorporated to further validate and enhance model robustness.

Therefore, ST-GPINN provides a transformative framework for water quality predictions, demonstrating high accuracy, scalability, and robustness. Nevertheless, its adaptability to dynamically evolving WDSs remains limited. Future efforts should focus on improving computational efficiency and developing generalizable architectures to reduce the need for retraining across varied network topologies.

Methods

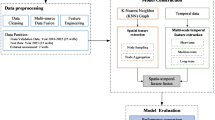

General frameworks

The proposed ST-GPINN model for water quality predictions in WDSs integrates both physics-informed and data-driven approaches, without relying on EPANET’s water quality simulations. The general framework is illustrated in Fig. 7a. The process begins by establishing an initial network model. Hydraulic simulation is then performed using the EPS provided by EPANET, in order to obtain flow rates for each network link across time steps. These calculations are crucial for understanding the water flow dynamics and serve as the foundation for subsequent water quality predictions.

Illustrates the sequential steps: a Schematic diagram for node concentration prediction, showing the workflow for spatial discretization, virtual node insertion, and iterative forward-backward optimization; b Details of the Encoder-Processor-Decoder architecture, capturing spatio-temporal dependencies and predicting node concentrations with physical consistency.

After the hydraulic simulation, the network is discretized by dividing each selected link into segments based on a defined grid size, denoted as \(\sigma\). This segmentation is essential for improving the spatial resolution of the water quality predictions. This allows the model to capture more detailed variations in hydraulic properties along the pipe length. This finer resolution is particularly important for accurate water quality predictions in large and complex networks.

Virtual nodes are inserted at the boundaries of each segment. These virtual nodes are designed to represent intermediate positions along the segment. The elevation of these virtual nodes is determined by interpolating between the elevations of the adjacent inlet and outlet nodes. The demand at these virtual nodes is set to zero, ensuring that they do not affect the overall demand calculations. The other properties of the link segment, such as diameter and roughness, are retained, ensuring consistency with the overall link characteristics. This virtual node insertion procedure is systematically applied to all link segments in the WDS. This results in a fine-grained spatial discretization of the entire network.

To capture the temporal dynamics of water quality, the simulation period is divided based on a predefined time step parameter, denoted as \(\varphi\). This parameter governs the temporal resolution of the simulation. Adjusting the time step allows the model to accurately capture temporal changes in water quality while preserving computational efficiency. The time intervals are chosen to strike a balance between model accuracy and computational cost.

After completing spatial and temporal discretization, the generated WDS topology and initial water quality conditions are input into the ST-GPINN algorithm. The algorithm utilizes an Encoder module to process the input data, followed by a Processor module where the model incorporates the underlying physical laws governing water quality and hydraulic flow. The final Decoder module predicts the water quality values at each node for the next time step36.

The calculation of water quality is carried out iteratively across all time steps. As each new time step is computed, the water quality at each node is updated based on the preceding time step’s results. This iterative process continues until all time steps in the simulation are completed.

To optimize the model’s performance, loss functions are constructed to incorporate both data-driven and physics-based components. These functions measure both the discrepancy between predicted and observed water quality values at each node and the deviation from the governing physical principles. During training, losses are minimized through backpropagation, adjusting the model parameters to improve prediction accuracy. The optimization process continues until the loss function reaches a predefined threshold or the maximum number of iterations is exceeded. This ensures that the model converges to an accurate and physically consistent solution for water quality prediction.

Finally, the effectiveness of the ST-GPINN model is evaluated by comparing its predictions against observed water quality data and benchmark models.

Water quality modeling

The WDS could be regarded as a directed graph where links are edges \(E=\left\{{e}_{i}\right|{i}\in {N}^{+},{i}\in [1,m]\}\) and nodes are vertices \(V=\{{v}_{j}|{j}\in {N}^{+},{j}\in [1,n]\}\), where \(m\) and \(n\) are the total number of links and nodes. Junctions, reservoirs, and tanks are regarded as nodes, while pipes, valves, and pumps are links.

In WDSs, dissolved substances are transported through pipes by the carrier water flow, with average velocities obtained from hydraulic simulations. These substances simultaneously undergo reactions, such as decay or growth, at predefined rates. Under standard operational conditions, longitudinal dispersion is typically negligible, indicating minimal mass transfer between adjacent water parcels. The mathematical representation of this transport in pipes is governed by the partial differential equation in Eq. 1.

Substances traveling through the pipe bulk flow may undergo chemical reactions described by a power-law kinetic model, as shown in Eq. 313.

Where \({K}_{b}\) is the bulk reaction constant; \(n\) is the reaction order.

If a limiting concentration is present, the reaction rate is modified according to the formulations presented in Eqs. 4–5, which correspond to the decay and growth processes, respectively38.

Where \({C}_{L}\) is the limiting concentration, which constrains the ultimate growth or decay of the substance.

Meanwhile, reactions at pipe walls involve substances transported from the bulk fluid to the pipe wall, interacting with materials like corrosion products or biofilms present near or on the wall surface. This wall reaction process is quantified by incorporating the pipe’s surface area per unit volume and the mass transfer rate between the bulk fluid and the pipe wall. The reaction rate at the pipe wall, considering first-order kinetics, is described by Eq. 639.

Where \({k}_{w}\) is the wall reaction rate constant; \({k}_{f}\) is the mass transfer coefficient, typically expressed using the dimensionless Sherwood number (Sh) by Eq. 739; \(R\) is the pipe radius.

Where \(D\) is the molecular diffusivity of the transported species (length²/time); \(d\) is the pipe diameter.

The Sherwood number depends on the Reynolds number (Re), the fully developed laminar flow (\(\mathrm{Re} < 2300\)), and transitional flow and turbulent flow (\(\mathrm{Re} > 2300\)) can be expressed as Eq. 8 and Eq. 9, respectively39.

Where \(\mathrm{Re}\) is the Reynolds number; \({Sc}\) is the Schmidt number.

The initial and boundary conditions adopted in the proposed simulation framework are explicitly defined as follows. Initially, the concentration of the contaminant or water quality parameter along each pipe segment is assumed to be uniformly zero, expressed mathematically as \(C(x,0)=0\). This condition represents a scenario in which the pipes are initially free of any contaminants or chemical substances, thereby establishing a clear baseline for subsequent water quality analysis. The concentrations at the junctions are set to predefined initial values.

For the boundary condition, the concentration at the reservoir node (source node) of the WDS is prescribed to initiate the contaminant transport simulation40. This boundary concentration is defined either as a constant value or as a time-dependent value following a pre-determined hourly pattern. Specifically, this pattern-based boundary condition is mathematically expressed as \(C(0,t)={C}_{{bc}}\times {Pattern}(t),\) where \({C}_{{bc}}\) indicates the baseline concentration at the reservoir, and \({Pattern}(t)\) denotes the hourly coefficients that modulate this baseline concentration. The hourly pattern reflects realistic operational scenarios, accounting for variations in water quality arising from periodic source fluctuations, treatment processes, or external influences.

Spatial discretization and virtual node insertion

The ST-GPINN process begins by discretizing the network into smaller spatial elements to enable fine-grained modeling of contaminant transport and water quality processes. Each pipe segment is subdivided using a pre-determined discretization length \(\sigma\), which is chosen to accurately capture variations in hydraulic and water quality dynamics. The spatial discretization length directly influences the resolution and precision of subsequent water quality predictions, with shorter segment lengths generally enhancing the accuracy of transport and reaction modeling.

Mathematically, a pipe segment with an original total length \({L}\) is divided into multiple shorter sub-segments, each approximately equal to \(\sigma\). The number of sub-segments \(N\) used to discretize the pipe is calculated as:

Where \({ceil}(\cdot )\) is the ceiling function, ensuring complete coverage of the original pipe length by the discrete segments.

Virtual nodes are systematically introduced at each subdivision boundary along the discretized segments. These virtual nodes functioned as intermediate computational nodes, significantly refining the network topology and enhancing the representation of spatial variations within each pipe. The elevations of these virtual nodes are computed using linear interpolation41 between the elevations of adjacent original inlet \({E}_{{\rm{inlet}}}\) and outlet \({E}_{{\rm{outlet}}}\) nodes of each pipe segment. Specifically, the elevation \({E}_{j}\) at the \(j\)-th virtual node, located a distance \({x}_{j}\) from the pipe inlet, is obtained by Eq. 11.

Where \({x}_{j}\) is the position of the virtual node relative to the inlet node along the segment.

The inserted virtual nodes are assigned zero demand to prevent artificial interference with system hydraulics across the network. Other pipe attributes, such as diameter, roughness, and chemical reaction coefficients, are kept consistent throughout all subdivided segments. The flowchart of spatial discretization and virtual node insertion is shown in Fig. 8. The hydraulic simulation results (pressure, flow velocity, and water quality) remain exactly consistent before and after virtual node insertion since all virtual nodes are assigned zero demand and pipe segments are linearly interpolated without altering the physical network topology.

Illustrates the methodologies for enhancing the granularity of WDS topology model: a Shows the spatial discretization process, where pipe segments are divided into sub-segments of length, enabling high-resolution capture of hydraulic and water quality variations. b Depicts the insertion of virtual nodes at sub-segment boundaries, with elevations computed via linear interpolation, refining the network for precise water quality predictions.

ST-GPINN model

The ST-GPINN combines the strengths of GNN and PINNs to accurately simulate water quality in WDSs. This approach is specifically designed to integrate spatial and temporal dependencies inherent in water transport processes, as well as to leverage physical laws governing advective transport, pipe wall reactions, and bulk reactions. The architecture consists primarily of three key modules: the Encoder, Processor, and Decoder, shown in Fig. 7b.

First, the Encoder is responsible for transforming the initial state of the WDS, including hydraulic parameters, pipe attributes, and water quality conditions, into a structured graph representation suitable for neural network processing. Relative displacement vectors that represent the spatial displacement between connected nodes (e.g. \({x}_{{ij}}={x}_{j}-{x}_{i}\), where \(i,{j}\) are the start and end nodes indices), and Euclidean distances between connected nodes (e.g. ||\({x}_{{ij}}\)||) are regarded as edge features. These node and edge features are passed through multilayer perceptrons (MLPs)37 to produce high-dimensional embeddings, facilitating the extraction of essential spatio-temporal relationships within the network, expressed as Eq. 1231.

Where \({h}_{j}^{(l)}\) is the node features at node \(i\) and layer \(l\); \({\mathscr{N}}{\mathscr{(}}i)\) is the set of neighboring nodes to node \(i\), and \({W}_{{ij}}^{(l)}\) and \({b}_{i}^{(l)}\) are learnable parameters and biases, respectively; \(\delta\) is the activation function.

Second, the Processor module applies a series of GNN layers31. This module utilizes message-passing mechanisms to propagate water quality information between interconnected nodes, effectively capturing complex interactions and dependencies within the network structure as defined in Eq. 1336. For each edge \({e}_{{ij}}\) connecting nodes \(i\) and \(j\), a message is computed based on the current features of the start node \({h}_{i}\), the end node \({h}_{j}\), and the edge itself.

Where \({\phi }_{e}\) is a learnable function, as a neural network, like Eq. 12, that determines how information is transmitted across the edge, \({\widetilde{h}}_{i},{\widetilde{h}}_{j}\) and\(\,{\widetilde{e}}_{{ij}}\) are features of \({h}_{i}\), \({h}_{j}\) and \({e}_{{ij}}\).

Then, each node \(i\) aggregates incoming messages from its neighboring nodes \(N(i)\), expressed as Eq. 1436.

Where \({\rho }_{m}\) is a permutation-invariant function, such as summation or averaging, ensuring that the aggregation is independent of the order of neighbors.

The node features are then updated by combining the aggregated message \({a}_{i}\) with the current node feature hi, expressed as Eq. 1536.

Where \({\phi }_{v}\) is another learnable function that determines how the node’s state evolves based on the aggregated features.

Thirdly, the Decoder serves to project the final latent node representations into physically interpretable predictions for the next time step. Specifically, it estimates the temporal evolution of the solution variable \({C}^{L}({{\bf{x}}}_{i},t)\) at each spatial node \({{\bf{x}}}_{i}\) based on the updated feature vector \({{\boldsymbol{h}}}_{i}^{(L)}\), where \(L\) denotes the number of GNN layers. The predicted temporal increment at each node is computed as shown in Eq. 16. This equation enables the Decoder to represent the spatio-temporal evolution of the system through graph-embedded representations36.

Where \({\phi }_{{\rm{dec}}}\) is a learnable MLP acting as the Decoder; \(\Delta {C}^{L}({{\bf{x}}}_{i},t)\) approximates the temporal change in the solution variable over one time step \(\varDelta t\).

To update the solution for the next time step, a forward Euler integration scheme is adopted, expressed as Eq. 17, which incrementally advances the system state over time. This explicit update rule ensures compatibility with the graph-discretized representation of the PDE system and facilitates rollout over multiple time steps in an autoregressive fashion.

The Decoder bridges the gap between high-dimensional latent embeddings and the physically constrained predictions required for PDE-based modeling. When combined with the physics-informed loss function, this structure enables accurate forecasting of pollutant transport.

Furthermore, to improve training stability and ensure numerical consistency across features, all physical variables are normalized prior to model training. Specifically, chlorine concentrations are scaled by dividing by the maximum reservoir concentration, resulting in a normalized range of [0, 1]. Flow velocities, pipe lengths, and other hydraulic attributes are normalized using min-max scaling across a network. Node features (node type, initial concentration) and edge features (relative displacement, Euclidean distance) are likewise rescaled to lie within [0, 1]. Following inference, the predicted concentrations are restored to their original physical units. This normalization strategy ensures stable gradient propagation and accelerates convergence during training.

Loss function

To ensure that ST-GPINN adheres to the physical laws governing WDSs, the model is trained using a composite loss function that incorporates both data fidelity and physical consistency. This dual-objective formulation enables the network to accurately capture spatio-temporal dynamics by enforcing compatibility with the known PDE in Eq. 1.

The physics-informed loss quantifies the discrepancy between the model predictions and the governing PDE at a set of collocation nodes \(\{{\left(x,t\right)}_{i}{\}}_{i=1}^{{N}_{p}}\), which are sampled throughout the spatio-temporal domain. The PDE residual is computed using numerical approximations of differential operators, and the residual loss is given by Eq. 18. This equation ensures that the learned solution remains physically plausible and satisfies the underlying dynamics of flow or transport within the network.

Where \({N}_{p}\) is the total number of nodes.

To incorporate available measurements (e.g., sensor observations of pressure or concentration), a data-driven supervision loss is introduced. Let \(\{({x}_{d},t,{C}_{{obs},d}^{N}(t)){\}}_{d=1}^{{N}_{d}}\) denote a set of observed data points. The data loss is defined as the mean squared error between the predicted and observed values, expressed as Eq. 19. This term enforces consistency with empirical measurements and anchors the learning process to real system behavior.

Where \({C}_{{obs},d}^{N}(t)\) is the concentration observed value at node \({d}\) and time \(t\); \({C}_{d}^{N}(t)\) is the concentration of model prediction at node \({d}\) and time \(t\); \({N}_{d}\) is the total number of observed values.

The overall training objective is to minimize a weighted combination of the physics-informed loss and the data-driven supervision loss:

Where \(\alpha > 0\) is a tunable hyperparameter that balances the influence of the physical constraints relative to the observational data.

In practice, \(\alpha\) can be selected based on the density and reliability of the available data, with larger values emphasizing physics consistency in low-data regimes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Pan, R. et al. Insight into mixed chlorine/chloramines conversion and associated water quality variability in drinking water distribution systems. Sci. Total Environ. 880, 163297 (2023).

Mu, T., Huang, M., Tan, H., Chen, G. & Zhang, R. Pressure and water quality integrated sensor placement considering leakage and contamination intrusion within water distribution systems. ACS EST Water 1, 2348–2358 (2021).

Li, Z., Liu, H., Zhang, C. & Fu, G. Generative adversarial networks for detecting contamination events in water distribution systems using multi-parameter, multi-site water quality monitoring. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 14, 100231 (2023).

Abokifa, A. A., Yang, Y. J., Lo, C. S. & Biswas, P. Investigating the role of biofilms in trihalomethane formation in water distribution systems with a multicomponent model. Water Res. 104, 208–219 (2016).

Li, Z., Liu, H., Zhang, C. & Fu, G. Real-time water quality prediction in water distribution networks using graph neural networks with sparse monitoring data. Water Res. 250, 121018 (2024).

Burkhardt, J. B., Szabo, J., Klosterman, S., Hall, J. & Murray, R. Modeling fate and transport of arsenic in a chlorinated distribution system. Environ. Model. Softw. 93, 322–331 (2017).

Qiu, M., Simpson, A. R., Elhay, S. & Alexander, B. Bridge-block partitioning algorithm for speeding up analysis of water distribution systems. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 145, 04019036 (2019).

Clark, R. M. & Sivaganesan, M. Predicting chlorine residuals and formation of TTHMs in drinking water. J. Environ. Eng. 124, 1203–1210 (1998).

Liou, C. P. & Kroon, J. R. Modeling the propagation of waterborne substances in distribution networks. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 79, 54–58 (1987).

Mu, T., Lu, Y., Tan, H., Zhang, H. & Zheng, C. Random walks partitioning and network reliability assessing in water distribution system. Water Resour. Manag. 35, 2325–2341 (2021).

Rossman, L. A. & Boulos, P. F. Numerical methods for modeling water quality in distribution systems: a comparison. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 122, 137–146 (1996).

Rossman, L. A., Brown, R. A., Singer, P. C. & Nuckols, J. R. DBP formation kinetics in a simulated distribution system. Water Res. 35, 3483–3489 (2001).

Rossman, L. A., Boulos, P. F. & Altman, T. Discrete volume-element method for network water-quality models. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 119, 505–517 (1993).

Zhang, Q. et al. Deep fuzzy mapping nonparametric model for real-time demand estimation in water distribution systems: a new perspective. Water Res. 241, 120145 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Developing stacking ensemble models for multivariate contamination detection in water distribution systems. Sci. Total Environ. 828, 154284 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Deep representation learning enables cross-basin water quality prediction under data-scarce conditions. npj Clean. Water 8, 33 (2025).

Dong, B., Shu, S. & Li, D. Optimization of secondary chlorination in water distribution systems for enhanced disinfection and reduced chlorine odor using deep belief network and NSGA-II. Water 16, 2666 (2024).

Liu, R., Zayed, T. & Xiao, R. Contrastive learning method for leak detection in water distribution networks. npj Clean. Water 7, 118 (2024).

Brazil, G. R. M. et al. Long duration forecasting and its performance capability for seasonal variation modelling of residual chlorine concentrations: a comparative evaluation of two small-scale water distribution systems in Japan. Water Res. 268, 122766 (2025).

Mao, R. et al. Joint majorization of waterworks and secondary chlorination points considering the chloric odor and economic investment in the DWDS using machine learning and optimization algorithms. Water Res. 220, 118595 (2022).

Saeed, A., Alsini, A. & Amin, D. Water quality multivariate forecasting using deep learning in a West Australian estuary. Environ. Model. Softw. 171, 105884 (2024).

Ehteram, M., Ahmed, A. N., Sherif, M. & El-Shafie, A. An advanced deep learning model for predicting water quality index. Ecol. Indic. 160, 111806 (2024).

Falas, S., Konstantinou, C. & Michael, M. K. Special session: physics-informed neural networks for securing water distribution systems. In: 2020 IEEE 38th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD). 37–40 (IEEE, 2020).

Ashraf, I., Hermes, L., Artelt, A. & Hammer, B. Spatial Graph Convolution Neural Networks for Water Distribution Systems. In Advances in Intelligent Data Analysis XXI. IDA 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (eds Crémilleux, B., Hess, S. & Nijssen, S.) vol 13876. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-30047-9_3 (Springer, Cham., 2023).

Daniel, I., Abhijith, G. R., Kutz, J. N., Ostfeld, A. & Cominola, A. Physics-informed machine learning for universal surrogate modelling of water quality parameters in water distribution networks. Eng. Proc. 69, 205 (2024).

Xing, L. & Sela, L. Graph neural networks for state estimation in water distribution systems: application of supervised and semisupervised learning. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 148, 04022018 (2022).

Kipf, T. & Welling, M. J. A. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. International Conference on Learning Representations. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1609.02907 (2017).

Salem, A. K., Taha, A. F. & Abokifa, A. A. Graph neural networks-based dynamic water quality state estimation in water distribution networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 138, 109426 (2024).

Yan, S., Xiong, Y. & Lin, D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 32, 1 (2018).

Yu, B., Yin, H. & Zhu, Z. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: a deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI). https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.04875 (2018).

Mu, T., Zhang, C., Huang, M., Ning, B. & Wang, J. Partitioning leakage detection in water distribution systems: a specialized deep learning framework enhanced by spatial–temporal graph convolutional networks. ACS EST Water 4, 3453–3463 (2024).

Mu, T., Ye, Y., Tan, H. & Zheng, C. Multistage iterative fully automatic partitioning in water distribution systems. Water Supply 21, 299–317 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Leakage zone identification in large-scale water distribution systems using multiclass support vector machines. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 142, 04016042 (2016).

Klise, K. A. et al. Water Network Tool for Resilience (WNTR) User Manual: Version 0.2.3. U.S. EPA Office of Research and Development, Washington, DC, EPA/600/R-20/185, 82p (2020).

Verwer, J. G., Spee, E. J., Blom, J. G. & Hundsdorfer, W. A second-order rosenbrock method applied to photochemical dispersion problems. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 20, 1456–1480 (1999).

Zhang, H. et al. Combining physics-informed graph neural network and finite difference for solving forward and inverse spatiotemporal PDEs. Comput. Phys. Commun. 308, 109462 (2025).

Dong, B., Shu, S. & Li, D. A unified spatial-pressure sensitivity partitioning and leakage detection method within a deep learning framework. Water 16, 542 (2024).

Rossman, L. A. EPANET 2: User’s Manual. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Risk Management Research Laboratory. (Cincinnati, OH, 2000).

Rossman, L. A., Clark, R. M., Grayman, W. M. & Grayman Modeling chlorine residuals in drinking-water distribution systems. J. Environ. Eng. 120, 803–820 (1994).

Maheshwari, A., Abokifa, A. A., Gudi, R. D. & Biswas, P. Coordinated decentralization-based optimization of disinfectant dosing in large-scale water distribution networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 144, 04018066 (2018).

Sitzenfrei, R., Möderl, M. & Rauch, W. Automatic generation of water distribution systems based on GIS data. Environ. Model. Softw. 47, 138–147 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the Liaoning Provincial Education Department Fund Project: Digital twin-driven global resilience assessment model and dynamic simulation research, No.202464252-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft; funding acquisition; F.D.: software, inspection; B.Z.: project administration; B.N.: validation, resources; J.L.: investigation; M.H.: data curation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions