Abstract

Claims of detections of gases in exoplanet atmospheres often rely on comparisons between models including and excluding specific chemical species. However, the space of molecular combinations available for model construction is vast and highly degenerate. Only a limited subset of these combinations is typically explored for any given detection. As a result, apparent detections of trace gases risk being artefacts of incomplete modelling rather than robust identification of atmospheric constituents, especially in the low-signal-to-noise regime. Here, using the sub-Neptune K2-18 b as a case study, we show that recent biosignature claims vanish when the model space is expanded, with numerous alternatives providing equally good or better fits. We demonstrate that the significance of a claimed detection relies on the choice of models being compared, and that model preference does not in itself imply the presence of a specific gas. We recommend treating model comparisons instead as relative adequacy tests, which should be supported by theoretical predictions and complementary metrics of statistical significance to attribute a signal to a particular gas.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The JWST/MIRI LRS transmission spectrum of K2-18 b, reduced with the JExoRES and JexoPipe pipelines, are available at https://osf.io/gmhw3.

Code availability

The self-consistent modelling framework ScCHIMERA is adapted from CHIMERA, which is available at https://github.com/mrline/CHIMERA. The chemical equilibrium modelling framework PICASO is available at https://github.com/natashabatalha/picaso/.

References

Gardner, J. P. et al. The James Webb Space Telescope. Space Sci. Rev. 123, 485–606 (2006).

Benneke, B. & Seager, S. How to distinguish between cloudy mini-Neptunes and water/volatile-dominated super-Earths. Astrophys. J. 778, 153 (2013).

Sedaghati, E. et al. Detection of titanium oxide in the atmosphere of a hot Jupiter. Nature 549, 238–241 (2017).

Fu, G. et al. Hydrogen sulfide and metal-enriched atmosphere for a Jupiter-mass exoplanet. Nature 632, 752–756 (2024).

Wilson, T. J. On the use of evidence and goodness-of-fit metrics in exoplanet atmosphere interpretation. Res. Not. Am. Astron. Soc. 5, 265 (2021).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 27, 1413–1432 (2017).

Welbanks, L., McGill, P., Line, M. & Madhusudhan, N. On the application of Bayesian leave-one-out cross-validation to exoplanet atmospheric analysis. Astron. J. 165, 112 (2023).

Nixon, M. C., Welbanks, L., McGill, P. & Kempton, E. M. R. Methods for incorporating model uncertainty into exoplanet atmospheric analysis. Astrophys. J. 966, 156 (2024).

Seager, S., Welbanks, L., Ellerbroek, L., Bains, W. & Petkowski, J. J. Prospects for detecting signs of life on exoplanets in the JWST era. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2416188122 (2025).

Benneke, B. et al. Water vapor and clouds on the habitable-zone sub-Neptune exoplanet K2-18b. Astrophys. J. Lett. 887, L14 (2019).

Foreman-Mackey, D. et al. A systematic search for transiting planets in the K2 data. Astrophys. J. 806, 215 (2015).

Trotta, R. Bayes in the sky: Bayesian inference and model selection in cosmology. Contemp. Phys. 49, 71–104 (2008).

Sharpe, S. W. et al. Gas-phase databases for quantitative infrared spectroscopy. App. Spectrosc. 58, 1452–1461 (2004).

Gordon, I. E. et al. The HITRAN2020 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 277, 107949 (2022).

JWST Transiting Exoplanet Community Early Release Science Team et al. Identification of carbon dioxide in an exoplanet atmosphere. Nature 614, 649–652 (2023).

Welbanks, L. et al. A high internal heat flux and large core in a warm Neptune exoplanet. Nature 630, 836–840 (2024).

Bell, T. J. et al. Methane throughout the atmosphere of the warm exoplanet WASP-80b. Nature 623, 709–712 (2023).

Bean, J. L. et al. The Transiting Exoplanet Community Early Release Science Program for JWST. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 130, 114402 (2018).

Lodders, K. Titanium and vanadium chemistry in low-mass dwarf stars. Astrophys. J. 577, 974–985 (2002).

Moses, J. I. et al. Compositional diversity in the atmospheres of hot Neptunes, with application to GJ 436b. Astrophys. J. 777, 34 (2013).

Feinstein, A. D. et al. Early Release Science of the exoplanet WASP-39b with JWST NIRISS. Nature 614, 670–675 (2023).

Carter, A. L. et al. A benchmark JWST near-infrared spectrum for the exoplanet WASP-39 b. Nat. Astron. 8, 1008–1019 (2024).

Moran, S. E. et al. High tide or riptide on the cosmic shoreline? A water-rich atmosphere or stellar contamination for the warm super-Earth GJ 486b from JWST observations. Astrophys. J. Lett. 948, L11 (2023).

Bello-Arufe, A. et al. Evidence for a volcanic atmosphere on the sub-Earth L 98-59 b. Astrophys. J. Lett. 980, L26 (2025).

Schlawin, E. et al. Possible carbon dioxide above the thick aerosols of GJ 1214 b. Astrophys. J. Lett. 974, L33 (2024).

Kempton, E. M. R. et al. A reflective, metal-rich atmosphere for GJ 1214b from its JWST phase curve. Nature 620, 67–71 (2023).

May, E. M. et al. Double trouble: two transits of the super-Earth GJ 1132 b observed with JWST NIRSpec G395H. Astrophys. J. Lett. 959, L9 (2023).

Gressier, A. et al. Hints of a sulfur-rich atmosphere around the 1.6 R⊕ super-Earth L98-59 d from JWST NIRspec G395H transmission spectroscopy. Astrophys. J. Lett. 975, L10 (2024).

Madhusudhan, N. et al. Carbon-bearing molecules in a possible Hycean atmosphere. Astrophys. J. Lett. 956, L13 (2023).

Madhusudhan, N. et al. New Cconstraints on DMS and DMDS in the atmosphere of K2-18 b from JWST MIRI. Astrophys. J. Lett. 983, L40 (2025).

Damiano, M., Bello-Arufe, A., Yang, J. & Hu, R. LHS 1140 b is a potentially habitable water world. Astrophys. J. Lett. 968, L22 (2024).

Demangeon, O. D. S. et al. Warm terrestrial planet with half the mass of Venus transiting a nearby star. Astron. Astrophys. 653, A41 (2021).

Seligman, D. Z. et al. Potential melting of extrasolar planets by tidal dissipation. Astrophys. J. 961, 22 (2024).

Goldreich, P. & Soter, S. Q in the Solar System. Icarus 5, 375–389 (1966).

Fortin, M.-A., Gazel, E., Kaltenegger, L. & Holycross, M. E. Volcanic exoplanet surfaces. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 516, 4569–4575 (2022).

Spencer, J. R. et al. Mid-infrared detection of large longitudinal asymmetries in Io’s SO2 atmosphere. Icarus 176, 283–304 (2005).

Kislyakova, K. G. et al. Effective induction heating around strongly magnetized stars. Astrophys. J. 858, 105 (2018).

Tsiaras, A., Waldmann, I. P., Tinetti, G., Tennyson, J. & Yurchenko, S. N. Water vapour in the atmosphere of the habitable-zone eight-Earth-mass planet K2-18 b. Nat. Astron. 3, 1086–1091 (2019).

Welbanks, L. et al. Mass–metallicity trends in transiting exoplanets from atmospheric abundances of H2O, Na, and K. Astrophys. J. Lett. 887, L20 (2019).

Madhusudhan, N., Nixon, M. C., Welbanks, L., Piette, A. A. A. & Booth, R. A. The interior and atmosphere of the habitable-zone exoplanet K2-18b. Astrophys. J. Lett. 891, L7 (2020).

Bézard, B., Charnay, B. & Blain, D. Methane as a dominant absorber in the habitable-zone sub-Neptune K2-18 b. Nat. Astron. 6, 537–540 (2022).

Schmidt, S. P. et al. A comprehensive reanalysis of K2-18 b's JWST NIRISS+NIRSpec transmission spectrum. Astron. J. 170, 298 (2025).

Fortney, J. J., Barstow, J. K. & Madhusudhan, N. in ExoFrontiers: Big Questions in Exoplanetary Science (ed. Madhusudhan, N.) Ch. 17 (IOP, 2021).

Madhusudhan, N. Exoplanetary atmospheres: key insights, challenges, and prospects. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 57, 617–663 (2019).

Moses, J. I. et al. Photochemistry of Saturn’s atmosphere. I. Hydrocarbon chemistry and comparisons with ISO observations. Icarus 143, 244–298 (2000).

Maguire, W. C., Hanel, R. A., Jennings, D. E., Kunde, V. G. & Samuelson, R. E. C3H8 and C3H4 in Titan’s atmosphere. Nature 292, 683–686 (1981).

de Graauw, T. et al. First results of ISO-SWS observations of Saturn: detection of CO2, CH3C2H, C4H2 and tropospheric H2O. Astron. Astrophys. 321, L13–L16 (1997).

Fouchet, T. et al. Jupiter’s hydrocarbons observed with ISO-SWS: vertical profiles of C2H6 and C2H2, detection of CH3C2H. Astron. Astrophys. 355, L13–L17 (2000).

Burgdorf, M., Orton, G., van Cleve, J., Meadows, V. & Houck, J. Detection of new hydrocarbons in Uranus’ atmosphere by infrared spectroscopy. Icarus 184, 634–637 (2006).

Meadows, V. S. et al. First Spitzer observations of Neptune: detection of new hydrocarbons. Icarus 197, 585–589 (2008).

Waite, J. H. et al. Ion neutral mass spectrometer results from the first flyby of Titan. Science 308, 982–986 (2005).

Sousa-Silva, C., Petkowski, J. J. & Seager, S. Molecular simulations for the spectroscopic detection of atmospheric gases. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 18970–18987 (2019).

Huang, Z. et al. Probing cold-to-temperate exoplanetary atmospheres: the role of water condensation on surface identification with JWST. Astrophys. J. 975, 146 (2024).

Luque, R. et al. Insufficient evidence for DMS and DMDS in the atmosphere of K2-18 b. From a joint analysis of JWST NIRISS, NIRSpec, and MIRI observations. Astron. Astrophys. 700, A284 (2025).

Hu, R. et al. A water-rich interior in the temperate sub-Neptune K2-18 b revealed by JWST. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.12622 (2025).

Jaziri, A. Y., Sohier, O., Venot, O. & Carrasco, N. Unraveling the non-equilibrium chemistry of the temperate sub-Neptune K2-18 b. Astron. Astrophys. 701, A33 (2025).

Palle, E. et al. Ground-breaking exoplanet science with the ANDES spectrograph at the ELT. Exp. Astron. 59, 29 (2025).

Bevington, P. R. & Robinson, D. K. Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences 3rd edn (McGraw-Hill, 2003).

Taylor, J. Are there spectral features in the MIRI/LRS transmission spectrum of K2-18b? Res. Not. Am. Astron. Soc. 9, 118 (2025).

Andrae, R., Schulze-Hartung, T. & Melchior, P. Dos and don’ts of reduced chi-squared. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1012.3754 (2010).

Buchner, J. et al. X-ray spectral modelling of the AGN obscuring region in the CDFS: Bayesian model selection and catalogue. Astron. Astrophys. 564, A125 (2014).

D’Agostino, R. B. & Stephens, M. A. Goodness-of-fit Techniques (Marcel Dekker, 1986).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. I. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (MIT Press, 2006).

Rotman, Y. et al. Enabling robust exoplanet atmospheric retrievals with Gaussian processes. Astrophys. J. 989, 201 (2025).

Cloutier, R. et al. Confirmation of the radial velocity super-Earth K2-18c with HARPS and CARMENES. Astron. Astrophys. 621, A49 (2019).

Rackham, B. V., Apai, D. & Giampapa, M. S. The transit light source effect: false spectral features and incorrect densities for M-dwarf transiting planets. Astrophys. J. 853, 122 (2018).

Piskorz, D. et al. Ground- and space-based detection of the thermal emission spectrum of the transiting hot Jupiter KELT-2Ab. Astron. J. 156, 133 (2018).

Mansfield, M. et al. A unique hot Jupiter spectral sequence with evidence for compositional diversity. Nat. Astron. 5, 1224–1232 (2021).

Iyer, A. R., Line, M. R., Muirhead, P. S., Fortney, J. J. & Gharib-Nezhad, E. The SPHINX M-dwarf spectral grid. I. Benchmarking new model atmospheres to derive fundamental M-dwarf properties. Astrophys. J. 944, 41 (2023).

Toon, O. B., McKay, C. P., Ackerman, T. P. & Santhanam, K. Rapid calculation of radiative heating rates and photodissociation rates in inhomogeneous multiple scattering atmospheres. J. Geophys. Res. 94, 16287–16301 (1989).

McKay, C. P., Pollack, J. B. & Courtin, R. The thermal structure of Titan’s atmosphere. Icarus 80, 23–53 (1989).

Gordon, S. & McBride, B. J. Computer Program for Calculation of Complex Chemical Equilibrium Compositions and Applications. Part 1: Analysis Technical Report 19950013764 (NASA Lewis Research Center, 1994).

Karman, T. et al. Update of the HITRAN collision-induced absorption section. Icarus 328, 160–175 (2019).

Polyansky, O. L. et al. ExoMol molecular line lists XXX: a complete high-accuracy line list for water. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 2597–2608 (2018).

Li, G. et al. Rovibrational line lists for nine isotopologues of the CO molecule in the X1Σ+ ground electronic state. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 216, 15 (2015).

Huang, X., Schwenke, D. W., Tashkun, S. A. & Lee, T. J. An isotopic-independent highly accurate potential energy surface for CO2 isotopologues and an initial 12C16O2 infrared line list. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 124311 (2012).

Hargreaves, R. J. et al. An accurate, extensive, and practical line list of methane for the HITEMP database. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 247, 55 (2020).

Coles, P. A., Yurchenko, S. N. & Tennyson, J. ExoMol molecular line lists—XXXV. A rotation–vibration line list for hot ammonia. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 490, 4638–4647 (2019).

Azzam, A. A. A., Tennyson, J., Yurchenko, S. N. & Naumenko, O. V. ExoMol molecular line lists—XVI. The rotation–vibration spectrum of hot H2S. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 460, 4063–4074 (2016).

Harris, G. J., Tennyson, J., Kaminsky, B. M., Pavlenko, Y. V. & Jones, H. R. A. Improved HCN/HNC linelist, model atmospheres and synthetic spectra for WZ Cas. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 367, 400–406 (2006).

Chubb, K. L., Tennyson, J. & Yurchenko, S. N. ExoMol molecular line lists—XXXVII. Spectra of acetylene. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 493, 1531–1545 (2020).

Allard, N. F., Spiegelman, F., Leininger, T. & Molliere, P. New study of the line profiles of sodium perturbed by H2. Astron. Astrophys. 628, A120 (2019).

Allard, N. F., Spiegelman, F. & Kielkopf, J. F. K-H2 line shapes for the spectra of cool brown dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 589, A21 (2016).

Underwood, D. S. et al. ExoMol molecular line lists—XIV. The rotation–vibration spectrum of hot SO2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 459, 3890–3899 (2016).

Husser, T. O. et al. A new extensive library of PHOENIX stellar atmospheres and synthetic spectra. Astron. Astrophys. 553, A6 (2013).

Stassun, K. G. et al. The revised TESS input catalog and candidate target list. Astron. J. 158, 138 (2019).

Tsai, S.-M. et al. VULCAN: an open-source, validated chemical kinetics Python code for exoplanetary atmospheres. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 228, 20 (2017).

Tsai, S.-M., Lee, E. K. H. & Pierrehumbert, R. A mini-chemical scheme with net reactions for 3D general circulation models. I. Thermochemical kinetics. Astron. Astrophys. 664, A82 (2022).

Lopez, E. D. & Fortney, J. J. Understanding the mass–radius relation for sub-Neptunes: radius as a proxy for composition. Astrophys. J. 792, 1 (2014).

Skilling, J. Nested sampling. In American Institute of Physics Conference Series Vol. 735 (eds Fischer, R. et al.) 395–405 (American Institute of Physics, 2004).

Feroz, F., Hobson, M. P. & Bridges, M. MULTINEST: an efficient and robust Bayesian inference tool for cosmology and particle physics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 398, 1601–1614 (2009).

Welbanks, L. & Madhusudhan, N. Aurora: a generalized retrieval framework for exoplanetary transmission spectra. Astrophys. J. 913, 114 (2021).

Welbanks, L. & Madhusudhan, N. On degeneracies in retrievals of exoplanetary transmission spectra. Astron. J. 157, 206 (2019).

Mukherjee, S., Batalha, N. E., Fortney, J. J. & Marley, M. S. PICASO 3.0: a one-dimensional climate model for giant planets and brown dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 942, 71 (2023).

Madhusudhan, N. & Seager, S. A temperature and abundance retrieval method for exoplanet atmospheres. Astrophys. J. 707, 24–39 (2009).

Mukherjee, S. et al. The Sonora substellar atmosphere models. IV. Elf Owl: atmospheric mixing and chemical disequilibrium with varying metallicity and C/O ratios. Astrophys. J. 963, 73 (2024).

Wogan, N. F. photochem: chemical model of planetary atmospheres. Astrophysics Source Code Library ascl:2406.021 (2024).

Asplund, M., Grevesse, N., Sauval, A. J. & Scott, P. The chemical composition of the Sun. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 47, 481–522 (2009).

Richard, C. et al. New section of the HITRAN database: collision-induced absorption (CIA). J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 113, 1276–1285 (2012).

Lecavelier Des Etangs, A., Pont, F., Vidal-Madjar, A. & Sing, D. Rayleigh scattering in the transit spectrum of HD 189733b. Astron. Astrophys. 481, L83–L86 (2008).

Line, M. R. & Parmentier, V. The influence of nonuniform cloud cover on transit transmission spectra. Astrophys. J. 820, 78 (2016).

Rothman, L. S. et al. HITEMP, the high-temperature molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 111, 2139–2150 (2010).

Yurchenko, S. N. & Tennyson, J. ExoMol line lists—IV. The rotation–vibration spectrum of methane up to 1500 K. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 440, 1649–1661 (2014).

Yurchenko, S. N., Barber, R. J. & Tennyson, J. A variationally computed line list for hot NH3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 413, 1828–1834 (2011).

Barber, R. J. et al. ExoMol line lists— III. An improved hot rotation–vibration line list for HCN and HNC. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 437, 1828–1835 (2014).

Karlovets, E. V. et al. Addition of the line list for carbon disulfide to the HITRAN database: line positions, intensities, and half-widths of the 12C32S2, 32S12C34S, 32S12C33S, and 13C32S2 isotopologues. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 258, 107275 (2021).

Wilzewski, J. S., Gordon, I. E., Kochanov, R. V., Hill, C. & Rothman, L. S. H2, He, and CO2 line-broadening coefficients, pressure shifts and temperature-dependence exponents for the HITRAN database. Part 1: SO2, NH3, HF, HCL, OCS and C2H2. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 168, 193–206 (2016).

Sousa-Silva, C., Al-Refaie, A. F., Tennyson, J. & Yurchenko, S. N. ExoMol line lists—VII. The rotation–vibration spectrum of phosphine up to 1500 K. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 446, 2337–2347 (2015).

Rothman, L. S. et al. The HITRAN2012 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 130, 4–50 (2013).

Mant, B. P., Yachmenev, A., Tennyson, J. & Yurchenko, S. N. ExoMol molecular line lists—XXVII. Spectra of C2H4. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 478, 3220–3232 (2018).

Sung, K., Toon, G. C., Mantz, A. W. & Smith, M. A. H. FT-IR measurements of cold C3H8 cross sections at 7–15 μm for Titan atmosphere. Icarus 226, 1499–1513 (2013).

Pica-Ciamarra, L., Madhusudhan, N., Cooke, G. J., Constantinou, S. & Binet, M. A systematic search for trace molecules in exoplanet K2-18 b. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.10539 (2025).

Pinhas, A., Rackham, B. V., Madhusudhan, N. & Apai, D. Retrieval of planetary and stellar properties in transmission spectroscopy with AURA. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 5314–5331 (2018).

Welbanks, L. & Madhusudhan, N. On atmospheric retrievals of exoplanets with inhomogeneous terminators. Astrophys. J. 933, 79 (2022).

Nixon, M. C. & Madhusudhan, N. Assessment of supervised machine learning for atmospheric retrieval of exoplanets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 496, 269–281 (2020).

Nixon, M. C. & Madhusudhan, N. Aura-3D: a three-dimensional atmospheric retrieval framework for exoplanet transmission spectra. Astrophys. J. 935, 73 (2022).

Lunine, J. I. The atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 31, 217–263 (1993).

Jennewein, D. M. et al. in Practice and Experience in Advanced Research Computing 2023: Computing for the Common Good 296–301 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2023).

Acknowledgements

L.W. and M.C.N. were supported by the Heising-Simons Foundation through a 51 Pegasi b Fellowship. P.M. and M.C.N. were supported under grant JWST-AR 06347 (principal investigator M.C.N.). P.M. acknowledges that this work was performed under the auspices of the US Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. Computing support for this work came from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory 19th Institutional Computing Grand Challenge programm (principal investigator P.M.). The document number is LLNL-JRNL-2005017. L.W., L.J.T. and M.R.L. acknowledge support from NASA XRP Grant 80NSSC24K0160 (principal investigator L.W.). D.Z.S. is supported by an NSF Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellowship under award AST-2303553. This research award is partially funded by a generous gift of C. Simonyi to the NSF Division of Astronomical Sciences. The award is made in recognition of substantial contributions to Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time. S.M. is supported by the Templeton Theory-Experiment (TEX) Cross Training Fellowship from the Templeton foundation. S.M. also acknowledges use of the lux supercomputer at UC Santa Cruz, funded by NSF MRI grant AST 1828315. A.D.F. acknowledges funding from NASA through the NASA Hubble Fellowship grant HST-HF2-51530.001-A awarded by STScI. L.W., L.S.W., M.R.L. and Y.R. acknowledge Research Computing at Arizona State University118 for providing high-performance computing and storage. M.C.N. acknowledges University of Maryland high-performance computing resources used to conduct research presented in this paper. We thank T. Greene, J. Lunine and A. Bello-Arufe for helpful comments on the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W. led the development of the project and co-leads this publication with M.C.N. as both contributions were fundamental for the completion of this paper. L.W. and M.C.N. contributed equally to the study. L.W. performed the atmospheric modelling for the 33 parameter model, and validated the 1D RCTE and 1D RCPE models. L.W. contributed to the paper, figures and tables preparation, interpretation of observations, and statistical analysis. M.C.N. led the parametric atmospheric modelling and led the investigation of hydrocarbons as well as the production of relevant line lists and sources of opacity. M.C.N. contributed to the paper, figures and tables preparation, interpretation of observations, and statistical analysis. P.M. contributed to the discussions that shaped and formed this project, contributed to the production of atmospheric models, contributed to the statistical analysis in this paper and provided critical interpretation of the results. P.M. contributed to the paper, figures and tables preparation. L.J.T. created the grids of self-consistent models, both 1D RCTE and 1D RCPE. L.J.T. contributed to the analysis of the observations and performed part of the parameter estimation (retrievals). L.S.W. contributed to the statistical analysis and the production of the atmospheric models and grid-based methodology. Y.R. performed the GP analysis of the observations. L.T., L.S.W. and Y.R. contributed to the paper. A.D.F. contributed to the analysis of the observations, text and figures. S.M. computed the chemical equilibrium parametric model fits with PICASO and computed 1D chemical kinetic models for the atmosphere of K2-18 b using photochem. S.M. contributed to the text, figures and tables. S.S. helped develop the scope of the project and provided feedback on the paper. M.R.L. provided guidance and training to the team. M.R.L. developed the 1D RCPE and 1D RCTE methodology and contributed to the statistical analysis. B.B. contributed text and comments to the paper. T.G.B. contributed to the analysis of the observations and statistical analysis. T.G.B. contributed to the paper, figures and tables. D.Z.S. contributed to the text and provided feedback on the scope of the project. V.P. provided comments on the paper and provided input into the statistical analysis in the project. D.K.S. provided comments on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Dominique Petit dit de la Roche and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

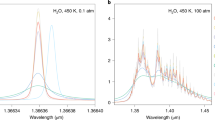

Extended Data Fig. 1 Posterior model and data realizations for MIRI observations of K2-18 b.

A Posterior data (gray) and model (orange) realizations generated from a flat-line model. Purple points indicate the median retrieved transit depth in each wavelength bin; vertical error bars represent the uncertainty in transit depth and horizontal bars indicate the bin width. B Residuals between the data realizations and the best-fit flat-line model. C As panel A, but for the model including a single-kernel Gaussian Process (GP) noise component. The GP identifies correlated structure near 7 μm and 8.5–9 μm, but this additional complexity is not statistically preferred over the flat-line model with white noise. D Residuals between the data realizations and the best-fit GP model.

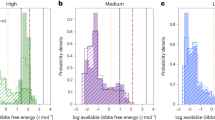

Extended Data Fig. 2 Normalized residuals of the JExoRES and JexoPipe spectra relative to flat-line models.

Histograms of normalized residuals, defined as ([data − model]/σ), for the JExoRES and JexoPipe reductions compared with their best-fit featureless spectra. Data represent single measurements per wavelength bin (n=1); bars show the frequency distribution of normalized residuals. The black curve indicates the standard Normal (Gaussian) distribution used for comparison.

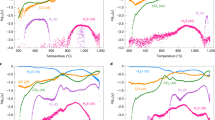

Extended Data Fig. 3 Predicted chemical composition of a K2-18 b-like atmosphere from radiative-convective-photochemical and kinetics models.

A Average volume mixing ratios of gases with abundances exceeding 1 ppm in the 1 mbar-1 μbar region, computed using two independent photochemical kinetics models, Photochem (blue) and Vulcan (red) for an atmosphere with metallicity [M/H] = +2.25 and C/O = 0.8. Only species with infrared-active bands are shown. B Vertical abundance profiles from the 1D radiative-convective-photochemical equilibrium (1D-RCPE) grid for the same composition ([M/H] = 2.25, C/O = 0.8) assuming full heat redistribution. Several hydrocarbons and sulfur-bearing products are present at non-negligible abundances in the observable atmosphere. These species arise from coupled thermochemical, photochemical, and vertical-mixing processes within the modeled atmosphere.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Median model fits for the JExoRES reduction of the K2-18 b transmission spectrum.

Median model evaluations for selected atmospheric models applied to the JExoRES dataset. Vertical error bars show 1σ standard deviations on the measured transit depth; horizontal bars indicate wavelength bin widths. Each point represents a single spectral bin. The Anderson-Darling and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests find the residuals statistically consistent with a Normal distribution, indicating that the data cannot distinguish between these models. Equivalent fits are obtained for the JexoPipe reduction (not shown).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Schematic representation of model comparisons and relative Bayesian evidence.

Diagram showing the models listed in Extended Data Table 3, connected by green lines representing the absolute difference in Bayesian evidence (\(| \ln (B)|\)) between model pairs. Each link illustrates how the apparent detection significance depends on the specific pair of models compared. Lines represent calculated differences in Bayesian evidence between models.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Welbanks, L., Nixon, M.C., McGill, P. et al. Challenges in the detection of gases in exoplanet atmospheres. Nat Astron (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02730-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02730-4