Abstract

Coulombic interactions can be used to assemble charged nanoparticles into higher-order structures, but the process requires oppositely charged partners that are similarly sized. The ability to mediate the assembly of such charged nanoparticles using structurally simple small molecules would greatly facilitate the fabrication of nanostructured materials and harnessing their applications in catalysis, sensing and photonics. Here we show that small molecules with as few as three electric charges can effectively induce attractive interactions between oppositely charged nanoparticles in water. These interactions can guide the assembly of charged nanoparticles into colloidal crystals of a quality previously only thought to result from their co-crystallization with oppositely charged nanoparticles of a similar size. Transient nanoparticle assemblies can be generated using positively charged nanoparticles and multiply charged anions that are enzymatically hydrolysed into mono- and/or dianions. Our findings demonstrate an approach for the facile fabrication, manipulation and further investigation of static and dynamic nanostructured materials in aqueous environments.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text of the paper, the Supplementary Information and also from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Sergeev, G. B. & Klabunde, K. J. Nanochemistry 2nd edn (Elsevier, 2013).

Ozin, G. A., Arsenault, A. & Cademartiri, L. Nanochemistry: A Chemical Approach to Nanomaterials 2nd edn (RSC Publishing, 2008).

Walter, M. et al. A unified view of ligand-protected gold clusters as superatom complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9157–9162 (2008).

Bedanta, S. & Kleemann, W. Supermagnetism. J. Phys. D 42, 013001 (2009).

Morup, S., Hansen, M. F. & Frandsen, C. Magnetic interactions between nanoparticles. Beilstein J. Nanotech. 1, 182–190 (2010).

Song, L. & Deng, Z. Valency control and functional synergy in DNA-bonded nanomolecules. ChemNanoMat 3, 698–712 (2017).

Wei, Y., Bishop, K. J. M., Kim, J., Soh, S. & Grzybowski, B. A. Making use of bond strength and steric hindrance in nanoscale ‘synthesis’. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 9477–9480 (2009).

Liu, K. et al. Step-growth polymerization of inorganic nanoparticles. Science 329, 197–200 (2010).

Liu, K. et al. Copolymerization of metal nanoparticles: a route to colloidal plasmonic copolymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2648–2653 (2014).

Klinkova, A., Thérien-Aubin, H., Choueiri, R. M., Rubinstein, M. & Kumacheva, E. Colloidal analogs of molecular chain stoppers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18775–18779 (2013).

Shevchenko, E. V., Talapin, D. V., Kotov, N. A., O’Brien, S. & Murray, C. B. Structural diversity in binary nanoparticle superlattices. Nature 439, 55–59 (2006).

Udayabhaskararao, T. et al. Tunable porous nanoallotropes prepared by post-assembly etching of binary nanoparticle superlattices. Science 358, 514–518 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Colloidal crystal ‘alloys’. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20443–20450 (2019).

Girard, M. et al. Particle analogs of electrons in colloidal crystals. Science 364, 1174–1178 (2019).

Vasquez, Y., Henkes, A. E., Bauer, J. C. & Schaak, R. E. Nanocrystal conversion chemistry: a unified and materials-general strategy for the template-based synthesis of nanocrystalline solids. J. Solid State Chem. 181, 1509–1523 (2008).

Krishnadas, K. R. et al. Interparticle reactions: an emerging direction in nanomaterials chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 1988–1996 (2017).

Yin, Y. et al. Formation of hollow nanocrystals through the nanoscale Kirkendall effect. Science 304, 711–714 (2004).

Son, D. H., Hughes, S. M., Yin, Y. & Alivisatos, A. P. Cation exchange reactions in ionic nanocrystals. Science 306, 1009–1012 (2004).

Park, J., Zheng, H., Jun, Y.-w & Alivisatos, A. P. Hetero-epitaxial anion exchange yields single-crystalline hollow nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13943–13945 (2009).

Skrabalak, S. E. et al. Gold nanocages: synthesis, properties, and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1587–1595 (2008).

Li, H. et al. Sequential cation exchange in nanocrystals: preservation of crystal phase and formation of metastable phases. Nano Lett. 11, 4964–4970 (2011).

Hong, S., Choi, Y. & Park, S. Shape control of Ag shell growth on Au nanodisks. Chem. Mater. 23, 5375–5378 (2011).

Buck, M. R. & Schaak, R. E. Emerging strategies for the total synthesis of inorganic nanostructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 6154–6178 (2013).

Kalsin, A. M. et al. Electrostatic self-assembly of binary nanoparticle crystals with a diamond-like lattice. Science 312, 420–424 (2006).

Kalsin, A. M., Kowalczyk, B., Smoukov, S. K., Klajn, R. & Grzybowski, B. A. Ionic-like behavior of oppositely charged nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 15046–15047 (2006).

Kalsin, A. M. & Grzybowski, B. A. Controlling the growth of ‘ionic’ nanoparticle supracrystals. Nano Lett. 7, 1018–1021 (2007).

Wang, L. Y., Albouy, P. A. & Pileni, M. P. Synthesis and self-assembly behavior of charged Au nanocrystals in aqueous solution. Chem. Mater. 27, 4431–4440 (2015).

Kostiainen, M. A. et al. Electrostatic assembly of binary nanoparticle superlattices using protein cages. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 52–56 (2013).

Liljeström, V., Seitsonen, J. & Kostiainen, M. A. Electrostatic self-assembly of soft matter nanoparticle cocrystals with tunable lattice parameters. ACS Nano 9, 11278–11285 (2015).

Hassinen, J., Liljeström, V., Kostiainen, M. A. & Ras, R. H. A. Rapid cationization of gold nanoparticles by two-step phase transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7990–7993 (2015).

Laio, A. & Parrinello, M. Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12562–12566 (2002).

Barducci, A., Bussi, G. & Parrinello, M. Well-tempered metadynamics: a smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 020603 (2008).

Beyeh, N. K. et al. Crystalline cyclophane–protein cage frameworks. ACS Nano 12, 8029–8036 (2018).

Schulze, H. Schwefelarsen in wässriger lösung. J. Prakt. Chem. 25, 431–452 (1882).

Hardy, W. B. A preliminary investigation of the conditions which determine the stability of irreversible hydrosols. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 66, 110–125 (1900).

Trefalt, G., Szilágyi, I. & Borkovec, M. Schulze–Hardy rule revisited. Colloid Polym. Sci. 298, 961–967 (2020).

Gasparotto, P., Meißner, R. H. & Ceriotti, M. Recognizing local and global structural motifs at the atomic scale. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 486–498 (2018).

Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

Gasparotto, P., Bochicchio, D., Ceriotti, M. & Pavan, G. M. Identifying and tracking defects in dynamic supramolecular polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 589–599 (2020).

Mackay, A. L. A dense non-crystallographic packing of equal spheres. Acta Crystallogr. 15, 916–918 (1962).

Garzoni, M., Cheval, N., Fahmi, A., Danani, A. & Pavan, G. M. Ion-selective controlled assembly of dendrimer-based functional nanofibers and their ionic-competitive disassembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3349–3357 (2012).

Astachov, V. et al. In situ functionalization of self-assembled dendrimer nanofibers with cadmium sulfide quantum dots through simple ionic-substitution. New J. Chem. 40, 6325–6331 (2016).

Julin, S. et al. DNA origami directed 3D nanoparticle superlattice via electrostatic assembly. Nanoscale 11, 4546–4551 (2019).

House, J. E. A TG study of the kinetics of decomposition of ammonium carbonate and ammonium bicarbonate. Thermochim. Acta 40, 225–233 (1980).

Lofton, C. & Sigmund, W. Mechanisms controlling crystal habits of gold and silver colloids. Adv. Funct. Mater. 15, 1197–1208 (2005).

Wang, D. et al. How and why nanoparticle’s curvature regulates the apparent pKa of the coating ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 2192–2197 (2011).

Boyer, P. D. Energy, life, and ATP (Nobel Lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37, 2297–2307 (1998).

van Rossum, S. A. P., Tena-Solsona, M., van Esch, J. H., Eelkema, R. & Boekhoven, J. Dissipative out-of-equilibrium assembly of man-made supramolecular materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 5519–5535 (2017).

Singh, N., Formon, G. J. M., De Piccoli, S. & Hermans, T. M. Devising synthetic reaction cycles for dissipative non-equilibrium self-assembly. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906834 (2020).

Ragazzon, G. & Prins, L. J. Energy consumption in chemical fuel-driven self-assembly. Nat. Nanotech. 13, 882–889 (2018).

Wang, G. & Liu, S. Strategies to construct a chemical-fuel-driven self-assembly. ChemSystemsChem 2, e1900046 (2020).

Weißenfels, M., Gemen, J. & Klajn, R. Dissipative self-assembly: fueling with chemicals versus light. Chem 7, 23–37 (2021).

Grötsch, R. K. et al. Dissipative self-assembly of photoluminescent silicon nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14608–14612 (2018).

Grötsch, R. K. et al. Pathway dependence in the fuel-driven dissipative self-assembly of nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9872–9878 (2019).

van Ravensteijn, B. G. P., Hendriksen, W. E., Eelkema, R., van Esch, J. H. & Kegel, W. K. Fuel-mediated transient clustering of colloidal building blocks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 9763–9766 (2017).

Hsu, C. C. et al. Role of synaptic vesicle proton gradient and protein phosphorylation on ATP-mediated activation of membrane-associated brain glutamate decarboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24366–24371 (1999).

Boekhoven, J. et al. Dissipative self-assembly of a molecular gelator by using a chemical fuel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4825–4828 (2010).

Leira-Iglesias, J., Sorrenti, A., Sato, A., Dunne, P. A. & Hermans, T. M. Supramolecular pathway selection of perylenediimides mediated by chemical fuels. Chem. Commun. 52, 9009–9012 (2016).

Wang, G., Sun, J., An, L. & Liu, S. Fuel-driven dissipative self-assembly of a supra-amphiphile in batch reactor. Biomacromolecules 19, 2542–2548 (2018).

Zhang, Y. X. & Zeng, H. C. Surfactant-mediated self-assembly of Au nanoparticles and their related conversion to complex mesoporous structures. Langmuir 24, 3740–3746 (2008).

Klajn, R. et al. Bulk synthesis and surface patterning of nanoporous metals and alloys from supraspherical nanoparticle aggregates. Adv. Funct. Mater. 18, 2763–2769 (2008).

Heo, K., Miesch, C., Emrick, T. & Hayward, R. C. Thermally reversible aggregation of gold nanoparticles in polymer nanocomposites through hydrogen bonding. Nano Lett. 13, 5297–5302 (2013).

Stolzenburg, P., Hämisch, B., Richter, S., Huber, K. & Garnweitner, G. Secondary particle formation during the nonaqueous synthesis of metal oxide nanocrystals. Langmuir 34, 12834–12844 (2018).

Reisler, E. & Egelman, E. H. Actin structure and function: what we still do not understand. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36133–36137 (2007).

Pfaendtner, J., Lyman, E., Pollard, T. D. & Voth, G. A. Structure and dynamics of the actin filament. J. Mol. Biol. 396, 252–263 (2010).

Senesi, A. J. & Lee, B. Small-angle scattering of particle assemblies. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 48, 1172–1182 (2015).

Macfarlane, R. J. et al. Nanoparticle superlattice engineering with DNA. Science 334, 204–208 (2011).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015).

Tribello, G. A., Bonomi, M., Branduardi, D., Camilloni, C. & Bussi, G. PLUMED 2: new feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604–613 (2014).

Houben, L. & Bar Sadan, M. Refinement procedure for the image alignment in high-resolution electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy 111, 1512–1520 (2011).

Houben, L., Weissman, H., Wolf, S. G. & Rybtchinski, B. A mechanism of ferritin crystallization revealed by cryo-STEM tomography. Nature 579, 540–543 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) (grants 820008 to R.K. and 818776 to G.M.P.), the Minerva Foundation with funding from the Federal German Ministry for Education and Research and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants 200021_175735 and IZLIZ2_183336 to G.M.P.). We acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 812868. Z.C. acknowledges support from the Planning and Budgeting Committee of the Council for Higher Education, the Koshland Foundation and a McDonald–Leapman grant. The authors acknowledge the computational resources provided by the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS). The support of the Irving and Cherna Moskowitz Center for Nano and Bio-Nano Imaging is gratefully acknowledged. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility, operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Extraordinary facility operations were supported in part by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on the response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.B. synthesized positively charged NPs, studied their interactions with oligoanions and developed a method to prepare crystalline NP aggregates. A.G. and C.P. performed the computational studies. J.G. developed the reverse system of negatively charged NPs and oligocations. B.L. performed and analysed the SAXS measurements. N.E. and L.H. performed cryo-STEM imaging and analysis. Z.C. contributed to the characterization of the NPs. R.K. supervised the project, coordinating with G.M.P., who supervised the computational studies. R.K. prepared the manuscript, with contributions from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Chemistry thanks Tobias Kraus, Asaph Widmer-Cooper and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Dependence of the titration behavior on nanoparticle size.

Differently sized TMA-functionalized Au NPs (4.8 nm, 8.8 nm, and 13.1 nm) at the same overall concentration of TMA in solution were titrated with the same solution of EDTA3– (the NPs were prepared analogously to those described in the Methods section). a, Left: Change in the position of Au·TMA’s SPR peak as a function of amount of EDTA3– added. In all cases, the amount of NP-adsorbed TMA was 20 nmol. The dashed red line denotes the point of electroneutrality (6.7 nmol of triply charged EDTA). Right: Relative dimensions of Au·TMA used in titration experiments. b, Normalized position of Au·TMA’s SPR peak as a function of amount of EDTA3– added (replotted from a). The normalized data show that the titration profiles are nearly the same irrespective of the NP size, indicating that the interparticle interactions are governed predominantly by electrostatics. The dashed red line denotes the point of electroneutrality (6.7 nmol of triply charged EDTA).

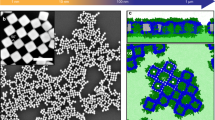

Extended Data Fig. 2 Representative SEM images of colloidal crystals co-assembled from TMA-functionalized Au NPs and various multiply charged anions.

The following anions were used: a–c, EDTA3–; d–j, citrate3–; k, l, pyrophosphate4–; m–s, triphosphate5–; t, u, trimetaphosphate3–; v, w, hexametaphosphate6–; x–z, ATP4–. The size of the NPs was 4.7 nm (panels n–r), 7.4 nm (panels a–f, j–m, and s–z), and 11.4 nm (panels g–i). In all cases, the counterion was Na+.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Nanoparticle packing on the faces of colloidal crystals.

SEM images of crystals co-assembled from TMA-functionalized 4.7 nm Au NPs and ATP. The magnified images in (b) and (e) show the hexagonal packing of NPs characteristic of the (111) facet of the face-centered cubic (fcc) structure. The magnified image in (g) shows the cubic packing of NPs characteristic of the (100) facet of the fcc structure.

Extended Data Fig. 4 SEM images of colloidal crystals co-assembled from negatively charged NPs and an organic trication.

The crystals were prepared using MUS-functionalized 4.7 nm Au NPs and triply charged cations, OMA3+, as described in the Methods section.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cryo-STEM images of aggregates of TMA-functionalized Au NPs and P3O105− or ATP.

a, Contrast-inverted bright-field cryo-STEM images of Au·TMA/P3O105− aggregates. Reconstruction and analysis of the aggregates denoted by circles are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6. b, Contrast-inverted bright-field cryo-STEM image of Au·TMA/ATP aggregates. Reconstruction and analysis of the aggregates denoted by circles are shown in Extended Data Fig. 7. All panels show single images at zero tilt, part of a tilt series spanning the tilt range of 60°.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Reconstruction and analysis of Au·TMA/P3O105− aggregates.

Labels a–d correspond to the locations indicated with the same labels in Extended Data Fig. 5. Left panel: ‘Atomistic’ models of the aggregates obtained after 3D reconstruction and particle coordinate refinement. Middle panel: Numbers of nearest neighbors in the first coordination shell in a color-coded representation for each NP. Average number of nearest neighbors = 6.4 (±0.8) (measured on ten different aggregates). Right panel: Pair correlation functions; the nearest-neighbor distance, Δ = 8.27 (±0.03) nm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Reconstruction and analysis of Au·TMA/ATP aggregates.

Labels a–d correspond to the locations indicated with the same labels in Extended Data Fig. 5. First panel: Contrast-inverted bright-field cryo-STEM images of individual Au·TMA/ATP aggregates. Second panel: ‘Atomistic’ models of the aggregates obtained after 3D reconstruction and particle coordinate refinement. Third panel: Numbers of nearest neighbors in the first coordination shell in a color-coded representation for each NP. Average number of nearest neighbors = 7.4 (±0.5) (measured on five different aggregates). Fourth panel: Pair correlation functions; the nearest-neighbor distance, Δ = 8.08 (±0.07) nm.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Detailed description of experimental and computational procedures, Supplementary Figs. 1–40 and references.

Supplementary Video 1

CG-MD simulation of citrate-mediated self-assembly of two TMA-decorated Au NPs.

Supplementary Video 2

CG-MD simulation of citrate-mediated self-assembly of four TMA-decorated Au NPs.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Fig. 1d,e.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Fig. 2b,d.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Fig. 4j,l.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data for Fig. 5c,d.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data for Fig. 6c,d,f–h,k,l.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bian, T., Gardin, A., Gemen, J. et al. Electrostatic co-assembly of nanoparticles with oppositely charged small molecules into static and dynamic superstructures. Nat. Chem. 13, 940–949 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-021-00752-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-021-00752-9

This article is cited by

-

Valence-free open nanoparticle superlattices

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Transforming an ATP-dependent enzyme into a dissipative, self-assembling system

Nature Chemical Biology (2025)

-

Direct observation and control of non-classical crystallization pathways in binary colloidal systems

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Intravitreal Bevacizumab nanoparticles ameliorates retinal vasculopathy in an in vivo mouse model of retinopathy of prematurity

Pediatric Research (2025)

-

Electrostatic enhanced terahertz metamaterial biosensing via gold nanoparticles integrated with biomolecules

Scientific Reports (2025)