Abstract

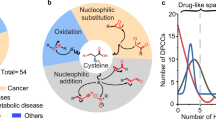

Covalent inhibitors that do not rely on hijacking enzymatic activity have mainly been limited to those targeting cysteine residues. The development of such cysteine-directed covalent inhibitors has greatly profited from the use of competitive residue-specific proteomics to determine their proteome-wide selectivity. Several probes have been developed to monitor other amino acids using this technology, and many more electrophiles exist to modify proteins. Nevertheless, there has been a lack of direct, proteome-wide comparisons of the selectivity of diverse electrophiles. Here we developed an unbiased workflow to analyse electrophile selectivity proteome-wide and used it to directly compare 56 alkyne probes containing diverse reactive groups. In this way, we verified and identified probes to monitor a total of nine different amino acids, as well as the protein amino terminus, across the proteome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Covalent inhibitors are powerful entities in drug discovery with key advantages including increased binding affinity to the target, the potential to generate selectivity among closely related proteins and improved pharmacodynamic properties1. Nevertheless, careful optimization of the reactivity and selectivity of these inhibitors is essential to avoid toxicity and possible immunogenic reactions1.

Competitive residue-specific proteomics provides essential tools for assessment of the proteome-wide selectivity of covalent inhibitors targeting cysteines based on the isotopic tandem orthogonal proteolysis-activity-based protein profiling platform2,3,4. Our isotopically labelled desthiobiotin azide (isoDTB) tags enable a streamlined experimental workflow (Fig. 1a) in which two samples of a proteome of interest are treated with a covalent ligand or with the corresponding solvent as a control5. Next, a broadly reactive alkyne probe is applied that labels many residues with alkynes. Residues already engaged by the ligand are blocked from this reactivity. In the next step, isotopically differentiated isoDTB tags are attached using copper-catalysed azide–alkyne cycloaddition6 to differentiate the proteins originating from the compound-treated and vehicle-treated samples. Then, the two samples are mixed, enriched and proteolytically digested, and the modified peptides are eluted, before being identified and quantified using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). Peptides containing residues that are engaged by the covalent ligand will show high ratios (R) between the two samples (R ≫ 1), whereas unaffected peptides will have ratios close to 1. In this way, target engagement and selectivity of covalent inhibitors can be investigated proteome-wide in a quantitative fashion5.

a, Workflow for competitive, residue-specific chemoproteomic experiments using the isoDTB-ABPP workflow5. b, Unbiased workflow to comprehensively investigate electrophile reactivity in the proteome using the MSFragger-based FragPipe computational platform31,32. RG, reactive group. D, desthiobiotin; CuAAC, copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition.

Covalent inhibitors that do not rely on hijacking enzyme activity have so far almost exclusively targeted cysteine residues7. However, as cysteine is a very rare amino acid, many binding pockets contain no suitable cysteine for covalent engagement8. Furthermore, various other nucleophilic residues (for example, lysines9,10, histidines11,12, and aspartates and glutamates13) represent targets of interest, as they are key to the mechanisms of action of many enzymes and can be posttranslationally modified (for example, by ubiquitination14, acylation15, methylation16 or phosphorylation17). Many reactive groups have been developed that target residues other than cysteines18, but global investigation of their targets and amino acid selectivity remains a challenge. Use of alkyne, azide or (desthio)biotin derivatives enables such investigations using direct enrichment19, but making these derivatives can be synthetically challenging, and this method requires the resulting modification to be stable at all residues. By contrast, use of a broadly reactive alkyne probe enables competitive residue-specific proteomics of unmodified covalent inhibitors regardless of the stability of their adducts. Use of such probes has been reported for cysteines2,3,20,21, lysines22,23, aspartates and glutamates8,24, methionines25,26 and tryptophans27,28, as well as tyrosines29,30. However, various different strategies have been used for the affinity tags, isotopic labelling, mass spectrometric instrumentation and data analysis in different studies, making it impossible to directly compare the reactivity and selectivity of the reported probes. To address this challenge, we directly compared a large variety of electrophiles and established their amino acid selectivity using the isoDTB activity‐based protein profiling (isoDTB-ABPP) workflow5. We enhanced and developed features for the MSFragger-based31,32 FragPipe computational platform so that proteome-wide electrophile selectivity could be studied in a completely unbiased fashion (Fig. 1b). Using this modified platform, we verified or identified probes to study nine different amino acids, as well as the protein amino terminus, proteome-wide. This set of probes will enable competitive profiling of covalent inhibitors against a variety of reactive amino acids, thereby guiding covalent ligand development. As we were most interested in antibacterial applications5, we performed the main part of our analysis in the lysate of Staphylococcus aureus SH1000 (ref. 33).

Results and discussion

Unbiased analysis of proteome-wide electrophile selectivity

We tailored the MSFragger-based FragPipe computational platform for competitive residue-specific proteomics31,32. FragPipe’s ultrafast fragment-ion indexing method is especially powerful for the complex data analyses needed to identify and localize modifications on peptides in an unbiased fashion. To validate additional features, we used a published dataset5, in which 1 mM iodoacetamide alkyne (IA-alkyne) was used in a noncompetitive isoDTB-ABPP workflow (Fig. 1b).

First, we optimized FragPipe’s open search to investigate which masses of modification were found on the detected peptides. In this workflow, the peptide is identified on the basis of the MS2 level, and the MS1 mass information is used to deduce the mass of the respective modification. Owing to the complex underlying data analysis, the open search31,32,34,35 implements extensive data filtration34,36,37,38, deisotoping39, mass calibration32 and summation of mass shifts35 to produce the final output. MSFragger efficiently handles the resulting large search space and enables discovery of unknown modifications.

In addition to the expected modification (Δmexp) by alkylation with IA-alkyne, we detected formylation (Δmf) of the modified peptides; this can occur during elution, redissolving or storage of peptides in solutions containing formic acid40 (Fig. 2a,b). Further, we identified smaller peaks corresponding to oxidation of the formed thioether (Δmox) or carbamidomethylation at a second cysteine (ΔmCAM). The detection of these minor modifications verified that MSFragger could identify different probe modifications proteome-wide in an unbiased fashion. As the highest deviation of all these masses of modification from the expected value was 0.0044 Da (6.9 ppm), the molecular formula could be directly deduced from the mass spectrometry (MS) data for unknown modifications.

a, Labelling of the proteome of S. aureus SH1000 with 1 mM IA‑alkyne and analysis using the isoDTB-ABPP workflow5 (Fig. 1b) resulted in generation of MS data for analysis of proteome-wide reactivity and selectivity. b, Through analysis with an open search in MSFragger31,32, the masses of modification that occurred proteome-wide were assigned. The peaks highlighted in red are the expected modifications (Δmexp) resulting from alkylation and modification with the light and heavy isoDTB tags, respectively. Further modifications of the alkylated peptides by oxidation (Δmox), formylation (Δmf) or carbamidomethylation on a second cysteine (ΔmCAM) were also detected. c, One peak pair (Δmexp) was selected for an MSFragger mass offset search to localize this modification to the modified amino acid(s), allowing selectivity to be assessed across all proteinogenic amino acids. The bar graph represents the fraction of all modified sites that were modified at the indicated amino acid. The same data are also presented in a letter plot, in which the size of the letter is scaled by the fraction of all modified sites that were modified at the indicated amino acid. All amino acids that were modified in fewer than 5% of cases are summarized as ‘Others’. The total number of modified sites is given as a bar graph on top of the letter plot. d, One amino acid (cysteine) was selected for quantification at the selected masses (Δmexp) using MSFragger closed search and the IonQuant quantification module42. Here, two datasets were analysed, in which the heavy and light samples were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and 4:1, respectively. Grey solid lines indicate the expected values of log2(R) = 0 and log2(R) = 2. Grey dashed lines indicate the respective preferred window of quantification (−1 < log2(R) < 1 for the 1:1 ratio; 1 < log2(R) < 3 for the 4:1 ratio). The total number of quantified sites is given at the top of the plot. The mass spectrometric experiments used for this analysis were performed as part of an earlier study5. All data are based on technical duplicates. C-term, C-terminal modification; N-term, N-terminal modification; PSM, peptide spectrum match.

Next, we performed a mass offset search, which involves searching at the mass with an indicated offset from the mass of the unmodified peptide31,32. The modification is computationally localized to an amino acid residue or a stretch of amino acids without previous specification of which amino acids might be modified32. Thus, FragPipe allows analysis of selectivity towards all amino acid residues and protein termini simultaneously. As expected, the offset corresponding to alkylation with IA-alkyne (Δmexp) showed high cysteine selectivity (89%; Fig. 2c).

Finally, the relative intensities of the light and heavy channels need to be accurately quantified. Previously, complex in-house software3,41 or workarounds in existing software5 often had to be used. Therefore, we extended FragPipe’s IonQuant42 to allow relative quantification of isotopically labelled modified peptides. Using a mass offset search, we quantified 1,896 modified peptides, with 99% in the preferred quantification window of −1 < log2(R) < 1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). We also used a closed search, in which the potentially modified amino acid(s) are specified before the search and one modification with the probe per peptide is allowed (Supplementary Discussion), to quantify 1,260 cysteines (>99% in the preferred window; Fig. 2d). The total number of modified sites, which is used for selectivity analysis based on a mass offset search (here 1,056 total modified sites; Fig. 2c), and the number of quantified residues in a closed search (here 1,260 cysteines) or mass offset search (here 1,896 peptides; Supplementary Fig. 1) is expected to differ because of differences in data analysis and filtering.

We also analysed a published dataset5 in which the heavy and light samples were mixed at a ratio of 4:1. Using a closed search, we quantified 989 cysteines, with 98% in the preferred quantification window of 1 < log2(R) < 3 (Fig. 2d). The high quality of this quantification data was comparable with that obtained by data evaluation with MaxQuant43 using our previously described workaround5 or pFind 3 (ref. 44) using a custom script for downstream analysis41 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Importantly, our automated FragPipe workflow simplifies the data analysis and allows analysis for probes that are not selective for a certain amino acid type.

Overall, the optimized FragPipe computational platform enables completely unbiased analysis of residue-specific proteomic data obtained with various probes, including identification of the mass of the modification, its amino acid selectivity and its use for quantitative applications. While this manuscript was under consideration, the pChem computational platform45 was reported; this platform produced similar results using our benchmarking data (Supplementary Discussion).

Having our unbiased analysis workflow at hand, we applied a standardized sample preparation protocol for all probes throughout this project to directly compare the proteome-wide reactivity and selectivity of diverse alkyne-containing probes (Supplementary Discussion). Two identical samples of S. aureus lysate were treated with 100 µM of the respective probe, modified with 100 µM of the light or heavy isoDTB tag, mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and analysed. A concise overview of the reactions of all electrophiles used in this study with proteinogenic amino acids is given in Supplementary Table 1.

Diverse chemistries allow monitoring of cysteines

Using the standard conditions for IA-alkyne3 (Fig. 3a), we detected 95% selectivity for cysteines and quantified 1,197 cysteines (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Notably, using the full workflow allowed us to study many more sites than was possible in an attempt to monitor modifications without enrichment (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Fig. 5). An increase in the concentration to 1 mM resulted in 86% selectivity for cysteines. Chloroacetamide CA-alkyne3 and α-bromomethyl ketone BMK-alkyne46 (Fig. 3a) also demonstrated high selectivity for cysteines (96% and 89%, respectively) and allowed quantification of 230 and 976 cysteines, respectively (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). A chloroacetamide negative control lacking the alkyne (CA-nitrile; Fig. 3a) did not yield any clear modification (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a–c,e,f, Structures of alkyne probes containing α-halocarbonyl (a), SNAr (b), hypervalent iodine (c), SN2 (e) or Michael acceptor (f) electrophiles that were investigated for their proteome-wide amino acid selectivity. Orange circles indicate the initial site of electrophilic reactivity. d,g, Amino acid selectivity of probes targeting cysteines (d) and reacting as Michael acceptors (g) upon treatment of the proteome of S. aureus SH1000 at a probe concentration of 100 µM. The data are presented as letter plots, in which the size of each letter is scaled by the fraction of all modified sites that were modified at the indicated amino acid. All amino acids that were modified in fewer than 5% of cases are summarized as ‘Others’. The total numbers of modified sites are given as a bar graph on top of the letter plot. aNo clear mass of modification was detected, and therefore no analysis of the amino acid selectivity was possible. bData for the indicated probe at 1 mM are shown. All data are based on technical duplicates.

Nucleophilic aromatic substitution (PFPSA-alkyne47, BrBT-alkyne, MSBT-alkyne, MST-alkyne and MSOD-alkyne20; Fig. 3b) showed high cysteine selectivity (70–92%) and allowed quantification of 362–1,061 cysteines (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). We also investigated hypervalent iodine reagents that have been described for labelling of cysteines in the proteome21. Whereas EBX1-alkyne48,49 introduced different modifications to cysteine, EBX2-alkyne50 selectively led to the minimal modification with an ethynyl group (85%, 1,251 cysteines; Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Figs. 8–11). Finally, nucleophilic substitution at unactivated sp3-carbon centres (Ep-alkyne and Ts-alkyne; Fig. 3e) showed a clear preference for cysteines, although substantial modification of glutamates was also found for Ts-alkyne (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13).

In aggregate, these probes quantified 1,941 cysteines, covering 37% of the 5,268 cysteines encoded in the S. aureus genome. IA-alkyne can still be considered the gold standard for monitoring of cysteine residues with residue-specific proteomics. Nevertheless, we verified the existence of many other complementary probes that could further increase coverage, with EBX2-alkyne and MSBT-alkyne being especially powerful (Supplementary Fig. 14).

Michael acceptors preferentially react with cysteines

Michael acceptors are mainstays of the design of covalent inhibitors (Fig. 3f). For a maleimide probe (MI-alkyne, after hydrolysis of the resulting succinimide (Supplementary Fig. 15)) and propiolamides (AlkPA-alkyne and ArPA-alkyne), we detected high selectivity (93–95%) and quantified a total of 283–752 cysteines (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17). We also observed the expected modification and strong proteomic labelling (160–1,174 localized sites; Fig. 3f,g and Supplementary Figs. 18–21) for all acceptor-substituted terminal alkenes except for AlkFAA-alkyne. Whereas AlkAA-alkyne labelled cysteine residues with 97% selectivity, fewer than 60% of labelled sites were cysteines for ArVSA-alkyne and ArVS-alkyne (>20% lysines, ~9% histidines, ~5% protein N-termini). Notably, N-terminal labelling occurred preferentially on prolines, when the initial methionine was removed51 (Supplementary Fig. 21). Although Michael acceptors can be designed to also target other amino acid residues such as lysines52, cysteines as the major modification sites need to be monitored carefully.

Studying lysine residues proteome-wide

The activated ester probe STP-alkyne (Fig. 4a) allows monitoring of many lysine residues in the proteome22. We verified its selectivity (78%; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23) and quantified 3,277 lysines. The remaining peptides were mainly labelled at serines (9%), threonines (2%) or N-termini (5%). This selectivity was retained even at a probe concentration of 1 mM. Four additional acylation reagents (TFP-alkyne22, NHS-alkyne23, ATT-alkyne53 and NASA-alkyne54; Fig. 4a) displayed similar selectivity and allowed quantification of 2,145–4,404 lysines (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 22 and 24). STP-alkyne also quantified 428 serines, 165 threonines and 152 protein N-termini.

a,c–g,j,k Structures of alkyne probes containing or producing activated ester (a), squaric acid ester (c), ethynylbenzaldehyde (d), nitrosobenzaldehyde (e), heteroaryl aldehyde (f), nitrilimine (g), ketoketenimine (j) or azirine (k) electrophiles that were investigated with respect to their proteome-wide amino acid selectivity. Orange circles indicate the initial site of electrophilic reactivity. For probes oNBA-alkyne, PhTet-alkyne, AmTet-alkyne, MeTet-alkyne, HC-alkyne and Isx-alkyne, the reactions leading to the reactive intermediate are also shown. b,h,i, Amino acid selectivity of probes targeting lysines (b), N-termini (h) or carboxylic acid residues (i) upon treatment of the proteome of S. aureus SH1000 at 100 µM probe concentration. The data are represented as letter plots, in which the size of each letter is scaled by the fraction of all modified sites that were modified at the indicated amino acid. All amino acids that were modified in fewer than 5% of cases are summarized as ‘Others’. The total numbers of modified sites are given as a bar graph on top of the letter plot. aLabelling was performed using UV activation at 280–315 nm (PhTet-alkyne, AmTet-alkyne and MeTet-alkyne) or 365 nm (oNBA-alkyne) for 10 min. bData for the indicated probe at 1 mM are shown. All data are based on technical duplicates.

Squaric acid derivatives also react with amines under physiological conditions55,56. Both AlkSq-alkyne and ArSq-alkyne demonstrated very high selectivity for lysines (93% and 90%, respectively; Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26). Therefore, ArSq-alkyne is a promising broadly reactive alkyne probe for lysines (2,990 quantified lysines), whereas structures like AlkSq-alkyne show potential for use in covalent inhibitor design owing to their tempered reactivity (1,339 quantified lysines)56. Another reactivity of lysines is the formation of imines with aldehydes. Previously, 2-ethynyl-benzaldehyde-based probes including EBA-alkyne (Fig. 4d) were shown to form imines that cyclized to stable isoquinolinium salts57 (Supplementary Fig. 27). EBA-alkyne exhibited high lysine selectivity and good proteomic coverage (81%, 3,796 quantified lysines; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29). Similarly, the nitrosobenzaldehyde formed by irradiation of oNBA-alkyne reacted irreversibly with lysines in cells58 (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 30). We detected highly selective modification of lysine by oNBA-alkyne, which was retained even at 1 mM probe concentration (93%; 1,456 lysines; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32). Importantly, several of these probes also quantified a substantial number of protein N-termini (243 for AlkSq-alkyne, 252 for ArSq-alkyne, 253 for EBA-alkyne and 35 for oNBA-alkyne).

Virtually none (0.05–0.68%) of the modifications with any of the lysine-directed probes occurred next to a proteolysis site, which indicates that the modified lysines are not recognized as cleavage sites by trypsin. As this could affect the detectability of some sequences59, the use of complementary proteases to increase lysine coverage may be particularly useful. Taking the data of all lysine-directed probes together, we quantified 9,129 lysines, covering 15% of the 62,166 lysines encoded in the genome of S. aureus. Although STP-alkyne remains the reagent of choice to study lysines for standard applications, ArSq-alkyne, EBA-alkyne and oNBA-alkyne also displayed high selectivity using complementary chemistries (Supplementary Fig. 33).

Global monitoring of N-termini of proteins

Although several lysine-directed probes allow monitoring of protein N-termini, selective chemistry is highly desirable. Carboxaldehydes of electron-poor heteroaromatics have previously been used to modify proteins (TCA-alkyne60 and PCA-alkyne61; Fig. 4f). Although we were not able to detect more than a few sites for TCA-alkyne in the proteome, PCA-alkyne showed high selectivity for the protein N-terminus (93%) and allowed quantification of 167 protein N-termini at 1 mM probe concentration (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Figs. 34–36). The coverage certainly needs to be improved; however, PCA-alkyne is a suitable starting point for selective monitoring of the protein N-terminus proteome-wide. Combining the data for PCA-alkyne (1 mM), STP-alkyne, ArSq-alkyne and EBA-alkyne, we were able to quantify 464 protein N-termini in 412 proteins (some proteins were detected with and without clipping of the N-terminal methionine), covering 14% of the 2,959 proteins encoded in the S. aureus genome.

Monitoring aspartates and glutamates across the proteome

Previously, we developed 2,5-disubstituted tetrazoles (Fig. 4g) to globally study aspartates and glutamates8. We verified the expected modification by formation of a nitrilimine upon light irradiation and the subsequent reactivity leading to a diacylated hydrazine (PhTet-alkyne, AmTet-alkyne and MeTet-alkyne; Fig. 4g and Supplementary Figs. 37 and 38). This modification showed a strong preference for aspartates and glutamates (79–94%), with MeTet-alkyne quantifying 2,192 aspartates and glutamates (Fig. 4i, Supplementary Figs. 38–40 and Supplementary Discussion). Hydrazonoyl chlorides liberate the same nitrilimine species without irradiation62, and we obtained exquisite reactivity and selectivity with HC-alkyne (91%, 2,450 aspartates and glutamates; Fig. 4g,i and Supplementary Figs. 37, 41 and 42).

Isoxazolium salts such as Isx-alkyne can modify glutamates in proteins63, but we also detected substantial labelling at lysines and the protein N-terminus (Fig. 4i,j and Supplementary Figs. 43 and 44). The use of 2H-azirines to target aspartates and glutamates has been described (Az-alkyne24; Fig. 4k and Supplementary Fig. 45). Using our workflow, we found that besides the expected reactivity (Δmexp), these probes showed a modification with a mass of Δmexp + 1 Da (Supplementary Figs. 46 and 47). We further analysed their combined selectivity (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Figs. 46 and 47) and found that 75% of all modifications were at aspartates and glutamates and 18% at cysteines. Therefore, Az-alkyne is a valuable probe for study of aspartates and glutamates, but care must be taken to account for cysteine off-targets.

Notably, MeTet-alkyne and HC-alkyne showed strong preferences for labelling glutamates (77% and 71%, respectively) over aspartates (17% and 19%, respectively), whereas Az-alkyne demonstrated a smaller difference (44% for glutamates versus 30% for aspartates), indicating that it reacted more readily with the more sterically hindered aspartate. Taking all carboxylic-acid-directed probes together, we quantified 7,811 aspartates and glutamates, corresponding to 7.8% of the 100,780 aspartates and glutamates encoded in the S. aureus genome. Specifically, MeTet-alkyne, HC-alkyne and Az-alkyne constitute a set of complementary probes that allow deep profiling of these amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 48). Considering that no probes exist to selectively monitor protein carboxyl termini proteome-wide, it is also noteworthy that all carboxylic-acid-directed probes together quantified 179 protein C-termini, with MeTet-alkyne and HC-alkyne at 1 mM being the most promising (101 and 109 quantified protein C-termini, respectively).

Residue-specific proteomics at tyrosines

Tyrosines offer a unique opportunity for various selective chemistries through reactions with the hydroxyl group, as well as with the electron-rich aromatic system. Sulfonylation of the hydroxyl group using sulfur–fluoride (SuFEx-alkyne)64,65 and sulfur–triazole (SuTEx1-alkyne and SuTEx2-alkyne)29,30 exchange chemistry has been established for proteome-wide approaches (Fig. 5a). We verified the tyrosine reactivity of these probes (55–71%; Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 49 and 50) and found lysine residues to be the most prominent off-targets (26–41%). Consistent with the findings of a previous study in human proteomes, SuTEx2-alkyne showed the highest tyrosine selectivity and allowed quantification of 2,653 tyrosines in bacterial lysates.

a,b,f–j, Structures of alkyne probes containing or producing sulfur (VI) exchange (a), triazolinedione (b), diazonium (f), oxaziridine (g), carbamoyl (h), o-quinone methide (i) or glyoxal (j) electrophiles that were investigated with respect to their proteome-wide amino acid selectivity. Orange circles indicate the initial site of electrophilic reactivity. For probes HMN-alkyne, HMP-alkyne, MMP-alkyne and PhGO-alkyne, the reactions leading to the reactive intermediate are also shown. c–e,k,l, Amino acid selectivity of the probes targeting tyrosines (c), aromatic residues (d), methionines (e), tryptophans and histidines (k) or arginines (l) upon treatment of the proteome of S. aureus SH1000 at 100 µM probe concentration. The data are represented as letter plots, in which the size of each letter is scaled by the fraction of all modified sites that were modified at the indicated amino acid. All amino acids that were modified in fewer than 5% of cases are summarized as ‘Others’. The total numbers of modified sites are given as a bar graph on top of the letter plot. aNo clear mass of modification was detected and therefore no analysis of the amino acid selectivity was possible. bLabelling was performed using UV activation at 280–315 nm (CP-alkyne, HMP-alkyne and MMP-alkyne) or 365 nm (HMN-alkyne) for 10 min. cData for the indicated probe at 1 mM are shown. dLabelling was performed in degassed lysate under argon. All data are based on technical duplicates.

Reagents including PTAD-alkyne have been established for labelling of the aromatic system of tyrosines66 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 51). We identified the expected adduct that showed high selectivity for tyrosines (95%; Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 52 and 53). We also detected a modification that corresponded to fragmentation of PTAD-alkyne to the isocyanate and subsequent reactivity, which showed some selectivity for lysines and protein N-termini and could be strongly reduced through addition of excess primary amine67 (Supplementary Figs. 52 and 53). Given the exquisite selectivity of the expected modification, it would be interesting to optimize the stability of these reagents to further reduce this side reactivity.

Through combination of the data for all tyrosine probes, we quantified 3,968 tyrosines covering 12% of the 32,172 tyrosines encoded in the S. aureus genome. Although SuTEx2-alkyne is currently the probe of choice for tyrosines, reagents such as PTAD-alkyne should enable the development of optimized complementary probes in the future (Supplementary Fig. 54).

Diazonium salts perform arylation chemistry

During our investigation of tyrosine-directed chemistries, we also considered aryl diazonium salts that have been shown to lead to azo coupling on tyrosines68 (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 55). Proteome-wide, we detected only minor azo coupling and almost exclusively arylation, corresponding to a formal loss of molecular nitrogen69 (Supplementary Figs. 55 and 56 and Supplementary Discussion). Strikingly, next to modifications on cysteines70, this led to up to 75% of all modifications being localized to aromatic amino acids for DA3-alkyne (1,218 total, 19% phenylalanines, 19% histidines, 8% tryptophans, 30% tyrosines; Fig. 5d and Supplementary Figs. 56 and 57).

A tool for global monitoring of methionine residues

Hypervalent iodine reagents to monitor methionines have been described but require an additional reaction step to give a stable modification26. Therefore, we focused on oxaziridines25 (Supplementary Fig. 58). OxMet1-alkyne did not result in detection of the expected modification (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 59). Implementing previously described design principles for more stable methionine modification71, we synthesized OxMet2-alkyne (Fig. 5g), which led to the detection of a high number of modified peptides, with a preference for methionine modification (73%, 1,838 quantified methionines, 8.5% of 21,677 encoded in the S. aureus genome; Fig. 5e and Supplementary Figs. 59 and 60). Thus, OxMet2-alkyne could be used as a tailored reagent for proteome-wide monitoring of methionines.

Proteome-wide monitoring of tryptophans and histidines

N-carbamoylpyridinium salts such as CP-alkyne (Fig. 5h) can photochemically label tryptophans in proteins through photoinduced electron transfer27,28 (Supplementary Fig. 61). Upon irradiation under protective gas, CP-alkyne showed the expected mass of modification in the proteome, with almost complete selectivity for tryptophans (55%) and histidines (35%; Fig. 5k and Supplementary Figs. 62 and 63), allowing quantification of 467 tryptophans and 797 histidines. This selectivity was retained when the reaction was run open to air or with 1 mM CP-alkyne (Supplementary Figs. 62 and 63). The reactivity with histidines was especially noteworthy, as we were unsuccessful in detecting the expected modification with reported histidine-selective thiophosphorodichloridates (TPAC-alkyne; Supplementary Fig. 64), probably owing to instability of the conjugate72. The fraction of >35% for histidine labelling with CP-alkyne was the highest we detected for any probe, making it the probe of choice to study histidines proteome-wide. Taking all conditions for CP-alkyne together, we quantified 1,697 histidines, covering 9.1% of the 18,746 histidines in the S. aureus genome (Supplementary Fig. 65).

Simultaneously, we investigated UV-activatable o-quinone methide precursors for tryptophan labelling through a formal [4 + 2]-cycloaddition (HMN-alkyne, HMP-alkyne and MMP-alkyne; Fig. 5i and Supplementary Fig. 66). We observed a preference for tryptophans (47–53%; Fig. 5k and Supplementary Figs. 67 and 68), with cysteines (14–29%), histidines (5–13%) and tyrosines (7–10%) being the main off-targets. Therefore, HMN-alkyne and MMP-alkyne could be used as complementary probes to study tryptophans proteome-wide. Through combination of the data for all probes, we quantified a total of 701 tryptophans covering 11% of the 6,183 tryptophans encoded in the S. aureus genome (Supplementary Fig. 65). While this manuscript was under consideration, N-sulfonyl oxaziridines were demonstrated to have strong potential to further expand this probe selection73.

Monitoring arginines across the whole proteome

Although arginine has been targeted with glyoxal-based reagents for bioconjugation74 and cross-linking75, no method was available to globally monitor arginines with residue-specific proteomics. Therefore, we synthesized PhGO-alkyne based on the known reactivity of phenylglyoxals with arginines that eventually produces a stable imidazole derivative (Fig. 5j and Supplementary Fig. 69). We detected only minor modification of the proteome, with the expected modification accompanied by an oxidation product76 (Supplementary Fig. 70). At an increased concentration of 1 mM PhGO-alkyne, however, we detected many modifications of the proteome (1,544 arginines were quantified, 5.4% of the 28,550 arginines encoded in the S. aureus genome), with the expected mass and high arginine selectivity (91%), alongside some oxidation (Fig. 5l and Supplementary Figs. 70 and 71). Almost none of the modified arginines were at the position of proteolytic cleavage (<0.2%), indicating that modified arginines are not recognized by trypsin as cleavage sites and that complementary proteases may help to increase coverage.

Probes to study nine amino acids and the protein N-terminus

Through screening of 56 alkyne probes, we identified a set of 17 probes that we currently consider to be ideal for profiling nine different amino acids and the protein N-terminus proteome-wide (Fig. 6). In total, we were able to quantify 20,558 different sites in the proteome using our probe selection. These sites covered 1,399 of the 2,959 proteins encoded in the S. aureus genome (47%) and 85% of the annotated essential proteins (301 of 353)77. Thus, our probe selection enables us to gain very deep insights into the bacterial proteome.

The heatmap shows the selectivities of a selection of the probes that allow study of diverse residues in the proteome of S. aureus. The colour is scaled by the fraction of all modified sites that were modified at the indicated amino acid. aLabelling was performed using UV-activation at 280–315 nm (MeTet-alkyne, CP-alkyne and MMP-alkyne) or 365 nm (oNBA-alkyne and HMN-alkyne) for 10 min. bData for the indicated probe at 1 mM are shown. cLabelling was performed in degassed lysate under argon. All data are based on technical duplicates.

To show that the applications of our probe selection are not restricted to bacterial systems, we also applied the probes in lysates of the human cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. We reproduced similar selectivities to those seen in the bacterial system for all probes (Supplementary Figs. 72–80) except PCA-alkyne78,79 (Supplementary Discussion).

Conclusions

We report a universal workflow that can be used to study the reactivity and amino acid selectivity of electrophilic probes in a proteome-wide setup. By extending and developing components of the MSFragger-based FragPipe computational platform31,32, we were able to identify masses of modification, amino acid selectivity and relative abundance in an unbiased fashion. As well as studying all probes at 100 µM, we studied 14 of them at 1 mM to compare the effects on selectivity and coverage (Supplementary Discussion).

Although our selection of 56 alkyne probes was certainly not comprehensive, we covered most chemistries that had more broadly been applied for protein labelling and did not require additional reagents. In this way, we verified and identified tailored probes to study nine different amino acids and the protein N-terminus proteome-wide. Within our set of probes, we verified the selectivity of IA-alkyne and EBX2-alkyne for cysteines2,3, STP-alkyne for lysines22, SuTEx2-alkyne for tyrosines29, CP-alkyne for tryptophans and PCA-alkyne for protein N-termini, as well as MeTet-alkyne8 and Az-alkyne24 for aspartates and glutamates. For several of these amino acids, we identified additional probes based on complementary chemistries, including ArSq-alkyne, EBA-alkyne and oNBA-alkyne for lysines; HC-alkyne for aspartates and glutamates; PTAD-alkyne for tyrosines; and HMN-alkyne and MMP-alkyne for tryptophans. In addition, we developed a tailored probe for methionines (OxMet2-alkyne) and identified probes to study histidines (CP-alkyne) and arginines (PhGO-alkyne) in a residue-specific fashion across the proteome.

The selectivities and reactivities of the studied probes (Supplementary Tables 9 and 10) represent a valuable guide for the selection of suitable electrophiles for various applications in protein labelling and ligand monitoring. It is now possible to directly compare the amino acid selectivity of all these different chemotypes. Furthermore, we are convinced that the number of quantified sites can be used as a measure to estimate the reactivity of a certain chemotype in the whole proteome and thus to choose candidate electrophiles for different applications that require various levels of reactivity.

To investigate whether the selectivities were reproduced in a cellular environment, we performed a preliminary experiment in which we treated S. aureus cells with our panel of 17 probes. Strikingly, 15 of the 17 probes also allowed monitoring of sites in this setup with very similar overall selectivity (Supplementary Figs. 81–85, Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Discussion).

Important residues for which no selective broadly reactive alkyne probes could be established here included serines and threonines, as well as protein C-termini. Neither the fluorophosphonate FP-alkyne80 nor the phosphorus–sulfur incorporation chemistry of PSI-alkyne81,82 yielded (stable) modifications at serine or threonine (Supplementary Figs. 86 and 87). In our view, STP-alkyne is the best probe for monitoring of at least some serines and threonines in a residue-specific fashion. For protein C-termini, the aspartate- and glutamate-directed probes allowed us to quantify 179 protein C-termini, but increased coverage and selective probes are surely desirable.

We stress that the reported selectivities only refer to the modifications that were stable enough to survive the entire isoDTB-ABPP workflow. Some probes are likely to produce additional, more labile modifications that we did not detect directly but that will be important to consider for covalent inhibitor design. To obtain more complete information about the initial selectivity of covalent inhibitors, an important application of our probe selection will be to competitively study target engagement for any covalently reactive protein ligand regardless of its amino acid selectivity and adduct stability.

These studies have enabled the profiling of established, tailored and previously unreported probes for residue-specific proteomics, which now allow monitoring of a total of nine different amino acids and the protein N-terminus. We expect our workflow and probe selection to be instrumental in the identification of selectively reactive groups for discovery and design of covalent ligands targeting diverse amino acids, thereby advancing the development of covalent inhibitors for the many protein binding sites that lack a suitable cysteine residue for engagement with the currently dominant acrylamide-based chemistry.

Methods

Cultivation and lysis of bacterial and human cells

S. aureus SH1000 (ref. 33) was a gift from S. J. Foster at the Krebs Institute, Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, University of Sheffield. Overnight cultures were inoculated with 5 µl of a glycerol stock into 5 ml of B medium (10 g l−1 peptone, 5 g l−1 NaCl, 5 g l−1 yeast extract, 1 g l−1 K2HPO4) and grown overnight (200 rpm, 37 °C). B medium was inoculated 1:100 with an overnight culture and incubated (200 rpm, 37 °C) until 1 h after it reached the stationary phase (optical density ~6). Cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min, 8,000g, 4 °C), and pellets of 100 ml initial culture were pooled and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl; pH = 7.4) before either immediate use or storage at −80 °C. The bacterial pellets were resuspended in 5 ml PBS and transferred into 7-ml tubes containing 0.1 mm ceramic beads (Peqlab, 91-PCS-CK01L). Cells were lysed in a Precellys 24 bead mill (3 × 30 s, 6,500 rpm) while cooling with an airflow that had been precooled with liquid nitrogen. The suspension was transferred into a microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged (30 min, 20,000g, 4 °C). The supernatants of several samples were pooled and filtered through a 0.45-µm filter. The protein concentration of the lysate was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (typical concentrations were between ~2 mg ml−1 and ~3 mg ml−1), and the concentration was adjusted to 1 mg ml−1 with PBS. The lysates were used immediately for all MS experiments.

MDA-MB-231 cells (ATCC, catalogue no. HTB-26) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM glutamine at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination. For preparation of lysates, cells were grown to confluence, scraped into PBS, collected by centrifugation (5 min, 800g) and washed with PBS. Pellets from 12 15-cm dishes were pooled. The pellets were either used immediately or stored at −80 °C. The pellets were resuspended in 5 ml PBS. Cells were lysed using sonication, and the suspension was transferred into a microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged (30 min, 20,000g, 4 °C). The supernatants of several samples were pooled. The protein concentration of the lysate was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (typical concentrations were between ~2 mg ml−1 and ~3 mg ml−1), and the concentration was adjusted to 1 mg ml−1 with PBS. The lysates were used immediately for all MS experiments.

isoDTB-ABPP experiments with constitutively active probes in lysate

Two technical replicates were prepared separately as distinct samples starting from the same lysate. Two samples of 1.00 ml freshly prepared lysate of the indicated cells were incubated with 20 µl of the respective probe—5 or 50 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (for HC-, SuFEx-, SuTEx1-, SuTEx2-, PTAD-, DA1-, DA2-, DA3-, OxMet1-, OxMet2- and TPAC-alkyne, dimethylformamide was used as the solvent instead of DMSO) at a final concentration of 100 µM or 1 mM, respectively—for 1 h at room temperature (for one control experiment with PTAD-alkyne, Tris (200 mM final concentration, pH = 7.4) was added to both samples before incubation). One sample was clicked to the heavy and one to the light isoDTB tag by addition of 120 µl of a solution consisting of 60 µl TBTA ligand (0.9 mg ml−1 in 4:1 tBuOH/DMSO), 20 µl CuSO4⋅5H2O (12.5 mg ml−1 in H2O), 20 µl TCEP (13 mg ml−1 in H2O, freshly prepared) and 20 µl of the respective isoDTB tag (5 mM in DMSO). After incubation of the samples (1 h at room temperature), the light- and heavy-labelled samples were combined in 8 ml cold acetone to precipitate all proteins. Precipitates were stored at −20 °C overnight.

isoDTB-ABPP experiments with photoactivated probes in lysate

Two technical replicates were prepared separately as distinct samples starting from the same lysate. Two samples of 1.20 ml freshly prepared lysate of the indicated cells were incubated with 24 µl of the respective photoprobe (5 or 50 mM stock in DMSO at a final concentration of 100 µM or 1 mM, respectively) for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were transferred to a six-well plate and irradiated for 10 min with either a Luzchem LZC-UVB lamp (280–315 nm; CP-, HMP-, MMP-, PhTet-, AmTet- and MeTet-alkyne) or a Philips TL-D BLB 18 W lamp (365 nm; oNBA- and HMN-alkyne). During irradiation, the six-well plate was placed on an ice pack, which had been precooled to 4 °C, for cooling. Then, 1.00 ml of each sample was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube, and one was clicked to the heavy and the other to the light isoDTB tag by addition of 120 µl of a solution consisting of 60 µl TBTA ligand (0.9 mg ml−1 in 4:1 tBuOH/DMSO), 20 µl CuSO4⋅5H2O (12.5 mg ml−1 in H2O), 20 µl TCEP (13 mg ml−1 in H2O, freshly prepared) and 20 µl of the respective isoDTB tag (5 mM in DMSO). After incubation of the samples at room temperature for 1 h, the light- and heavy-labelled samples were combined in 8 ml cold acetone to precipitate all proteins. Precipitates were stored at −20 °C overnight.

isoDTB-ABPP experiments with constitutively active probes in situ

Two technical replicates were prepared separately as distinct samples. S. aureus SH1000 pellets were freshly prepared and washed as described under ‘Cultivation and lysis of bacterial and human cells’. The bacterial pellets were resuspended in PBS to give a final optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm of 40. Two samples of 1.00 ml freshly prepared bacterial suspension were incubated with 20 µl of the respective probe—5 or 50 mM stock in DMSO (for HC-, SuTEx2-, PTAD- and OxMet2-alkyne, dimethylformamide was used as the solvent instead of DMSO) at a final concentration of 100 µM or 1 mM, respectively—for 1 h at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min, 8,000g, 4 °C) and washed twice with 1 ml PBS before storage at −80 °C. The pellets were thawed and resuspended in 1 ml PBS with 5 µl 10 mg ml−1 lysostaphin (recombinant from Staphylococcus simulans, dissolved in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH = 4.5). The samples were incubated with shaking at 200 rpm for 1 hour at 37 °C. Then, 20 µl 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate in PBS was added, and the samples were sonicated. Samples were then centrifuged at 21,100g for 30 min at room temperature, and 900 µl of the supernatant was taken for the further experiments. One sample was clicked to the heavy and one to the light isoDTB tag by addition of 108 µl of a solution consisting of 54 µl TBTA ligand (0.9 mg ml−1 in 4:1 tBuOH/DMSO), 18 µl CuSO4⋅5H2O (12.5 mg ml−1 in H2O), 18 µl TCEP (13 mg ml−1 in H2O, freshly prepared) and 18 µl of the respective isoDTB tag (5 mM in DMSO). After incubation of the samples (1 h at room temperature), the light- and heavy-labelled samples were combined into 8 ml cold acetone to precipitate all proteins. Precipitates were stored at −20 °C overnight.

isoDTB-ABPP experiments with photoactivated probes in situ

Two technical replicates were prepared separately as distinct samples. S. aureus SH1000 pellets were freshly prepared and washed as described in ‘Cultivation and lysis of bacterial and human cells’. The bacterial pellets were resuspended in PBS to give a final optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm of 40. Two samples of 1.30 ml freshly prepared bacterial suspension were incubated with 26 µl of the respective probe (5 mM stock in DMSO with a final concentration of 100 µM) for 30 min at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm. Then, 1.20 ml of each sample was transferred to a six-well plate and irradiated for 10 min with either a Luzchem LZC-UVB lamp (280–315 nm; CP-, MMP- and PhTet-alkyne) or a Philips TL-D BLB 18 W lamp (365 nm; oNBA- and HMN-alkyne). During irradiation, the six-well plate was placed on an ice pack precooled to 4 °C for cooling. Next, 1.00 ml of each sample was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. The cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min, 8,000g, 4 °C) and washed twice with 1 ml PBS before storage at −80 °C. The pellets were thawed and resuspended in 1 ml PBS with 5 µl 10 mg ml−1 lysostaphin (recombinant from S. simulans, dissolved in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH = 4.5). The samples were incubated with shaking at 200 rpm for 1 hour at 37 °C. Then, 20 µl 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate in PBS was added, and the samples were sonicated. The samples were centrifuged at 21,100g for 30 min at room temperature, and 900 µl of the supernatant was taken for the further experiments. One sample was clicked to the heavy and one to the light isoDTB tag by addition of 108 µl of a solution consisting of 54 µl TBTA ligand (0.9 mg ml−1 in 4:1 tBuOH/DMSO), 18 µl CuSO4⋅5H2O (12.5 mg ml−1 in H2O), 18 µl TCEP (13 mg ml−1 in H2O, freshly prepared) and 18 µl of the respective isoDTB tag (5 mM in DMSO). After incubation of the samples (1 h at room temperature), the light- and heavy-labelled samples were combined in 8 ml cold acetone to precipitate all proteins. Precipitates were stored at −20 °C overnight.

isoDTB-ABPP MS sample preparation

For all isoDTB-ABPP experiments, protein precipitates were centrifuged (3,500g, for 10 min at room temperature) and the supernatant was removed. The precipitates were resuspended in 1 ml cold MeOH by sonification and centrifuged (10 min, 21,100g, 4 °C). The supernatant was removed, and the washing step with MeOH was repeated once. The pellets were dissolved in 300 µl urea (8 M in 0.1 M aqueous triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB)) by sonification. Then, 900 µl TEAB (0.1 M in H2O) was added, and the solution was added to 1.2 ml of washed high-capacity streptavidin agarose beads (50 µl initial slurry, Fisher Scientific, catalogue no. 10733315) in NP40 substitute (0.2% in PBS). The samples were rotated for 1 h at room temperature to ensure binding to the beads.

The beads were centrifuged (1 min, 1,000g at room temperature) and the supernatant was removed. The beads were resuspended in 600 µl NP40 substitute (0.1% in PBS) and transferred to a centrifuge column (Fisher Scientific, catalogue no. 11894131). Beads were washed with 2 × 600 µl NP40 substitute (0.1% in PBS), 3 × 600 µl PBS and 3 × 600 µl H2O. The beads were resuspended in 600 µl urea (8 M in 0.1 M aqueous TEAB), transferred to a Protein LoBind tube (Eppendorf) and centrifuged (1 min, 1,000g). The supernatant was removed, and the beads were resuspended in 300 µl urea (8 M in 0.1 M aqueous TEAB) and incubated sequentially with 15 µl dithiothreitol (31 mg ml−1 in H2O) for 45 min (200 rpm, 37 °C), 15 µl iodoacetamide (74 mg ml−1 in H2O) for 30 min (200 rpm, room temperature) and 15 µl dithiothreitol (31 mg ml−1 in H2O) for 30 min (200 rpm, room temperature). The samples were then diluted with 900 µl TEAB (0.1 M in H2O) and centrifuged (1 min, 1,000g). After removal of the supernatant, the beads were resuspended in 200 µl urea (2 M in 0.1 M aqueous TEAB) and incubated with 4 µl trypsin (0.5 mg ml−1; Promega, V5113) overnight at 200 rpm and 37 °C.

The samples were diluted by addition of 400 µl NP40 substitute (0.1% in PBS) and transferred to a centrifuge column (Fisher Scientific, catalogue no. 11894131). Beads were washed with 3 × 600 µl NP40 substitute (0.1% in PBS), 3 × 800 µl PBS and 3 × 800 µl H2O. Peptides were eluted into Protein LoBind tubes with 1 × 200 µl and 2 × 100 µl formic acid (0.1% in 50% aqueous MeCN) or trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; 0.1% in 50% aqueous MeCN; used as an alternative to formic acid to avoid formylation of peptides40), followed by a final centrifugation (3 min, 3,000g). The solvent was removed in a rotating vacuum concentrator (~5 h, 30 °C), and the resulting residue was dissolved in 30 µl formic acid (1% in H2O) or TFA (0.1% in H2O) by sonification for 5 min. After washing filters (Merck, UVC30GVNB) with the resuspension buffer, the samples were loaded and filtered through them by centrifugation (3 min, 17,000g). The samples were then transferred to MS sample vials and stored at −20 °C until measurement.

Sample analysis by LC–MS/MS

We analysed 5 µl of each sample using a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) coupled to an Ultimate 3000 nano HPLC system (Dionex). Samples were loaded on an Acclaim C18 PepMap100 trap column (75 µm ID × 2 cm, Acclaim, PN 164535) and washed with 0.1% TFA. The subsequent separation was carried out on an AURORA series AUR2-25075C18A column (75 µm ID × 25 cm, serial no. IO257504282) with a flow rate of 400 nl min−1 using buffer A (0.1% formic acid in water) and buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The column was heated to 40 °C. Analysis started with washing in 5% buffer B for 7 min followed by a gradient from 5% to 40% buffer B over 105 min, a further increase to 60% buffer B in 10 min and final increase to 90% buffer B in 10 min. The concentration of buffer B was maintained at 90% for 10 min, then decreased to 5% in 0.1 min and held at 5% for another 9.9 min. The Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer was operated in TOP10 data-dependent mode. In the orbitrap, full MS scans were collected in a scan range of 300–1,500 m/z at a resolution of 70,000 and an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 3 × 106 with 80 ms maximum injection time. The most intense peaks were selected for MS2 measurement with a minimum AGC target of 1 × 103 and isotope exclusion and dynamic exclusion (exclusion duration: 60 s) enabled. Peaks with unassigned charge or a charge of +1 were excluded. Peptide match was ‘preferred’. MS2 spectra were collected at a resolution of 17,500, aiming for an AGC target of 1 × 105 with a maximum injection time of 100 ms. Isolation was conducted in the quadrupole using a window of 1.6 m/z. Fragments were generated using higher-energy collisional dissociation (normalized collision energy: 27%) and finally detected in the orbitrap. Proteomics data from the LC–MS/MS analyses were collected using Thermo Scientific Xcalibur (v.4.1).

Further experimental methods

All synthetic procedures, specialized sample preparation protocols that were used for individual samples only, and complete data analysis procedures can be found in Supplementary Information.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The mass spectrometric data for all proteomic analyses, which comprise all the raw data needed to reproduce our findings, have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository83 with dataset identifiers PXD024454 and PXD065811, where they are freely available. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for the MSFragger-based FragPipe analyses is available at https://fragpipe.nesvilab.org/. A custom script for downstream analysis of the pFind 3 data is available at https://github.com/morpheusliu/Post-processing-program-for-pFind3-results.

References

Singh, J., Petter, R. C., Baillie, T. A. & Whitty, A. The resurgence of covalent drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10, 307–317 (2011).

Backus, K. M. et al. Proteome-wide covalent ligand discovery in native biological systems. Nature 534, 570–574 (2016).

Weerapana, E. et al. Quantitative reactivity profiling predicts functional cysteines in proteomes. Nature 468, 790–795 (2010).

Kuljanin, M. et al. Reimagining high-throughput profiling of reactive cysteines for cell-based screening of large electrophile libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 630–641 (2021).

Zanon, P. R. A., Lewald, L. & Hacker, S. M. Isotopically labeled desthiobiotin azide (isoDTB) tags enable global profiling of the bacterial cysteinome. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2829–2836 (2020).

Rostovtsev, V. V., Green, L. G., Fokin, V. V. & Sharpless, K. B. A stepwise Huisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective “ligation” of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 2596–2599 (2002).

Sutanto, F., Konstantinidou, M. & Dömling, A. Covalent inhibitors: a rational approach to drug discovery. RSC Med. Chem. 11, 876–884 (2020).

Bach, K., Beerkens, B. L. H., Zanon, P. R. A. & Hacker, S. M. Light-activatable, 2,5-disubstituted tetrazoles for the proteome-wide profiling of aspartates and glutamates in living bacteria. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 546–554 (2020).

Carrera, A. C., Alexandrov, K. & Roberts, T. M. The conserved lysine of the catalytic domain of protein kinases is actively involved in the phosphotransfer reaction and not required for anchoring ATP. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 442–446 (1993).

Eliot, A. C. & Kirsch, J. F. Pyridoxal phosphate enzymes: mechanistic, structural, and evolutionary considerations. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 383–415 (2004).

Che, J. & Jones, L. H. Covalent drugs targeting histidine – an unexploited opportunity? RSC Med. Chem. 13, 1121–1126 (2022).

Rigden, DanielJ. The histidine phosphatase superfamily: structure and function. Biochem. J. 409, 333–348 (2007).

Kim, Y. et al. Glycosidase-targeting small molecules for biological and therapeutic applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 7036–7070 (2023).

Komander, D. & Rape, M. The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 203–229 (2012).

Shang, S., Liu, J. & Hua, F. Protein acylation: mechanisms, biological functions and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 396 (2022).

Wu, Q., Schapira, M., Arrowsmith, C. H. & Barsyte-Lovejoy, D. Protein arginine methylation: from enigmatic functions to therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 509–530 (2021).

Ubersax, J. A. & Ferrell Jr, J. E. Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 530–541 (2007).

Gehringer, M. & Laufer, S. A. Emerging and re-emerging warheads for targeted covalent inhibitors: applications in medicinal chemistry and chemical biology. J. Med. Chem. 62, 5673–5724 (2019).

Parker, C. G. & Pratt, M. R. Click chemistry in proteomic investigations. Cell 180, 605–632 (2020).

Motiwala, H. F., Kuo, Y.-H., Stinger, B. L., Palfey, B. A. & Martin, B. R. Tunable heteroaromatic sulfones enhance in-cell cysteine profiling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 1801–1810 (2020).

Abegg, D. et al. Proteome-wide profiling of targets of cysteine reactive small molecules by using ethynyl benziodoxolone reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10852–10857 (2015).

Hacker, S. M. et al. Global profiling of lysine reactivity and ligandability in the human proteome. Nat. Chem. 9, 1181–1190 (2017).

Ward, C. C., Kleinman, J. I. & Nomura, D. K. NHS-esters as versatile reactivity-based probes for mapping proteome-wide ligandable hotspots. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 1478–1483 (2017).

Ma, N. et al. 2H-azirine-based reagents for chemoselective bioconjugation at carboxyl residues inside live cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6051–6059 (2020).

Lin, S. et al. Redox-based reagents for chemoselective methionine bioconjugation. Science 355, 597–602 (2017).

Taylor, M. T., Nelson, J. E., Suero, M. G. & Gaunt, M. J. A protein functionalization platform based on selective reactions at methionine residues. Nature 562, 563–568 (2018).

Hoopes, C. R. et al. Donor–acceptor pyridinium salts for photo-induced electron-transfer-driven modification of tryptophan in peptides, proteins, and proteomes using visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6227–6236 (2022).

Tower, S. J., Hetcher, W. J., Myers, T. E., Kuehl, N. J. & Taylor, M. T. Selective modification of tryptophan residues in peptides and proteins using a biomimetic electron transfer process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9112–9118 (2020).

Hahm, H. S. et al. Global targeting of functional tyrosines using sulfur-triazole exchange chemistry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 150–159 (2019).

Brulet, J. W., Borne, A. L., Yuan, K., Libby, A. H. & Hsu, K.-L. Liganding functional tyrosine sites on proteins using sulfur–triazole exchange chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8270–8280 (2020).

Kong, A. T., Leprevost, F. V., Avtonomov, D. M., Mellacheruvu, D. & Nesvizhskii, A. I. MSFragger: ultrafast and comprehensive peptide identification in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nat. Methods 14, 513–520 (2017).

Yu, F. et al. Identification of modified peptides using localization-aware open search. Nat. Commun. 11, 4065 (2020).

Horsburgh, M. J. et al. σB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5457–5467 (2002).

Chang, H.-Y. et al. Crystal-C: a computational tool for refinement of open search results. J. Proteome Res. 19, 2511–2515 (2020).

Geiszler, D. J. et al. PTM-Shepherd: analysis and summarization of post-translational and chemical modifications from open search results. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 20, 100018 (2021).

Keller, A., Nesvizhskii, A. I., Kolker, E. & Aebersold, R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 74, 5383–5392 (2002).

Nesvizhskii, A. I., Keller, A., Kolker, E. & Aebersold, R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 75, 4646–4658 (2003).

da Veiga Leprevost, F. et al. Philosopher: a versatile toolkit for shotgun proteomics data analysis. Nat. Methods 17, 869–870 (2020).

Teo, G. C., Polasky, D. A., Yu, F. & Nesvizhskii, A. I. Fast deisotoping algorithm and its implementation in the MSFragger search engine. J. Proteome Res. 20, 498–505 (2021).

Lenčo, J., Khalikova, M. A. & Švec, F. Dissolving peptides in 0.1% formic acid brings risk of artificial formylation. J. Proteome Res. 19, 993–999 (2020).

Fu, L. et al. A quantitative thiol reactivity profiling platform to analyze redox and electrophile reactive cysteine proteomes. Nat. Protoc. 15, 2891–2919 (2020).

Yu, F. et al. Fast quantitative analysis of timsTOF PASEF data with MSFragger and IonQuant. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 19, 1575–1585 (2020).

Cox, J. & Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 (2008).

Chi, H. et al. Comprehensive identification of peptides in tandem mass spectra using an efficient open search engine. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 1059–1061 (2018).

He, J.-X. et al. A modification-centric assessment tool for the performance of chemoproteomic probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 904–912 (2022).

Abo, M. & Weerapana, E. A caged electrophilic probe for global analysis of cysteine reactivity in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 7087–7090 (2015).

Embaby, A. M., Schoffelen, S., Kofoed, C., Meldal, M. & Diness, F. Rational tuning of fluorobenzene probes for cysteine-selective protein modification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 8022–8026 (2018).

Frei, R. et al. Fast and highly chemoselective alkynylation of thiols with hypervalent iodine reagents enabled through a low energy barrier concerted mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16563–16573 (2014).

Tessier, R. et al. “Doubly orthogonal” labeling of peptides and proteins. Chem 5, 2243–2263 (2019).

Tessier, R. et al. Ethynylation of cysteine residues: from peptides to proteins in vitro and in living cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 10961–10970 (2020).

O’Shea, J. P. et al. pLogo: a probabilistic approach to visualizing sequence motifs. Nat. Methods 10, 1211–1212 (2013).

Pettinger, J., Jones, K. & Cheeseman, M. D. Lysine-targeting covalent inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15200–15209 (2017).

Hirata, T. et al. Synthesis and reactivities of 3-indocyanine-green-acyl-1,3-thiazolidine-2-thione (ICG-ATT) as a new near-infrared fluorescent-labeling reagent. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 6, 2179–2184 (1998).

Tamura, T. et al. Rapid labelling and covalent inhibition of intracellular native proteins using ligand-directed N-acyl-N-alkyl sulfonamide. Nat. Commun. 9, 1870 (2018).

Ivancová, I., Pohl, R., Hubálek, M. & Hocek, M. Squaramate-modified nucleotides and DNA for specific cross-linking with lysine-containing peptides and proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13345–13348 (2019).

Taylor, K. I., Ho, J. S., Trial HO, Carter, A. W. & Kiessling, L. L. Assessing squarates as amine-reactive probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25056–25060 (2023).

Deng, J.-R. et al. N-terminal selective modification of peptides and proteins using 2-ethynylbenzaldehydes. Commun. Chem. 3, 67 (2020).

Guo, A.-D. et al. Light-induced primary amines and o-nitrobenzyl alcohols cyclization as a versatile photoclick reaction for modular conjugation. Nat. Commun. 11, 5472 (2020).

Li, H., Frankenfield, A. M., Houston, R., Sekine, S. & Hao, L. Thiol-cleavable biotin for chemical and enzymatic biotinylation and its application to mitochondrial TurboID proteomics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 32, 2358–2365 (2021).

Onoda, A., Inoue, N., Sumiyoshi, E. & Hayashi, T. Triazolecarbaldehyde reagents for one-step N-terminal protein modification. ChemBioChem 21, 1274–1278 (2020).

MacDonald, J. I., Munch, H. K., Moore, T. & Francis, M. B. One-step site-specific modification of native proteins with 2-pyridinecarboxyaldehydes. Nat. Chem. Bio. 11, 326–331 (2015).

Zengeya, T. T. et al. Co-opting a bioorthogonal reaction for oncometabolite detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15813–15816 (2016).

Martin-Gago, P. et al. Covalent protein labeling at glutamic acids. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 589–597.e585 (2017).

Dong, J., Krasnova, L., Finn, M. G. & Sharpless, K. B. Sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEx): another good reaction for click chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9430–9448 (2014).

Cuesta, A., Wan, X., Burlingame, A. L. & Taunton, J. Ligand conformational bias drives enantioselective modification of a surface-exposed lysine on Hsp90. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3392–3400 (2020).

Ban, H., Gavrilyuk, J. & Barbas, C. F. Tyrosine bioconjugation through aqueous ene-type reactions: a click-like reaction for tyrosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1523–1525 (2010).

Ban, H. et al. Facile and stabile linkages through tyrosine: bioconjugation strategies with the tyrosine-click reaction. Bioconjug. Chem. 24, 520–532 (2013).

Zhang, J., Ma, D., Du, D., Xi, Z. & Yi, L. An efficient reagent for covalent introduction of alkynes into proteins. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 9528–9531 (2014).

Nothling, M. D. et al. Bacterial redox potential powers controlled radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 286–293 (2021).

Naveen, N., Sengupta, S. & Chandrasekaran, S. Metal-free S-arylation of cysteine using arenediazonium salts. J. Org. Chem. 83, 3562–3569 (2018).

Christian, A. H. et al. A physical organic approach to tuning reagents for selective and stable methionine bioconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12657–12662 (2019).

Jia, S., He, D. & Chang, C. J. Bioinspired thiophosphorodichloridate reagents for chemoselective histidine bioconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 7294–7301 (2019).

Xie, X. et al. Oxidative cyclization reagents reveal tryptophan cation–π interactions. Nature 627, 680–687 (2024).

Dovgan, I. et al. Arginine-selective bioconjugation with 4-azidophenyl glyoxal: application to the single and dual functionalisation of native antibodies. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 1305–1311 (2018).

Jones, A. X. et al. Improving mass spectrometry analysis of protein structures with arginine-selective chemical cross-linkers. Nat. Commun. 10, 3911 (2019).

Thompson, D. A., Ng, R. & Dawson, P. E. Arginine selective reagents for ligation to peptides and proteins. J. Pept. Sci. 22, 311–319 (2016).

Chaudhuri, R. R. et al. Comprehensive identification of essential Staphylococcus aureus genes using transposon-mediated differential hybridisation (TMDH). BMC Genomics 10, 291 (2009).

Soppa, J. Protein acetylation in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes. Archaea 2010, 820681 (2010).

Meyer, B. et al. Characterising proteolysis during SARS-CoV-2 infection identifies viral cleavage sites and cellular targets with therapeutic potential. Nat. Commun. 12, 5553 (2021).

Simon, G. M. & Cravatt, B. F. Activity-based proteomics of enzyme superfamilies: serine hydrolases as a case study. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11051–11055 (2010).

Vantourout, J. C. et al. Serine-selective bioconjugation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17236–17242 (2020).

Knouse, K. W. et al. Unlocking P(V): reagents for chiral phosphorothioate synthesis. Science 361, 1234–1238 (2018).

Perez-Riverol, Y. et al. The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D442–D450 (2019).

Acknowledgements

S.M.H. and P.R.A.Z. acknowledge funding from the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie through a Liebig Fellowship and a Ph.D. fellowship and from the TUM Junior Fellow Fund. S.M.H. acknowledges the Dutch Research Council (NWO) for funding through a VIDI grant (VI.Vidi.213.057). A.I.N. acknowledges financial support from the US National Institutes of Health (R01-GM-094231 and U24-CA271037). F.D.T. thanks the Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research and the Novartis-Berkeley Center for Proteomics and Chemistry Technologies for supporting this work. P.Z.M. thanks the American Cancer Society for a postdoctoral fellowship (PF-18-132-01-CDD). M.Z. acknowledges funding by the Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes through a Ph.D. fellowship; and K.L. received support from the collaborative research centre SFB1035 (German Research Foundation DFG, Sonderforschungsbereich 1035, Projektnummer 201302640, project B10). C.J.C. acknowledges funding from the National Institutes of Health (ES 28096 and GM139245). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We thank S. A. Sieber and his group (Technical University of Munich) for their generous support; the group of J. Waser (EPFL) for providing EBX1-alkyne; K.-L. Hsu and J. W. Brulet (University of Virginia) for providing SuTEx1-alkyne and SuTEX2-alkyne; and the group of P. S. Baran (Scripps Research Institute) for providing PSI-alkyne. We also thank S. Kollmannsberger and M. Iglhaut (Technical University of Munich) for assistance with the synthesis of probes; K. Bäuml and M. Wolff (Technical University of Munich) for technical assistance; and D. Geiszler, F. da Veiga Leprevost, D. Avtonomov and D. Polasky (University of Michigan) for useful discussions and technical assistance regarding developments in FragPipe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R.A.Z. and S.M.H. designed the research, planned experiments, and performed proteomics experiments and analysed the results. F.Y. and A.I.N. designed, developed and benchmarked data analysis software. P.R.A.Z. synthesized the majority of the probes. P.Z.M., L.L., M.Z., K.K., D.M., P.R., T.E.M. and M.C. contributed the synthesis of individual probes. K.L., C.J.C. and F.D.T. designed individual probes. P.R.A.Z. and S.M.H. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.I.N. is the founder of Fragmatics and serves on the scientific advisory boards of Protai Bio, Infinitopes and Mobilion Systems. A.I.N. is also a paid consultant for Novartis. A.I.N. and F.Y. have financial interests owing to the licensing of MSFragger and IonQuant to commercial entities. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Edward Tate and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion, Figs. 1–87, Tables 6–11, synthetic experimental procedures, Methods and NMR spectra.

Supplementary Table 1

Overview of the chemical mechanisms of the electrophiles used.

Supplementary Table 2

Overview of electrophile reactivity. A summary of the key information on masses of modification, amino acid selectivity and quantification for all probes.

Supplementary Table 3

Mass of modification data for all probes. Masses of modification were determined using an open search in MSFragger-based FragPipe.

Supplementary Table 4

Amino acid selectivity data for all probes. Amino acid selectivity was determined using a Mass offset search in MSFragger-based FragPipe.

Supplementary Table 5

Quantification using all probes. Quantification was mainly performed using MSFragger closed search and IonQuant labelling-based quantification. Individual datasets are also included that were quantified using MSFragger mass offset search and IonQuant labelling-based quantification or using MaxQuant or pFind 3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Numerical data to reproduce the plots in Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Numerical data to reproduce the plots in Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Numerical data to reproduce the plots in Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Numerical data to reproduce the plots in Fig. 5.

Source Data Fig. 6

Numerical data to reproduce the plots in Fig. 6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanon, P.R.A., Yu, F., Musacchio, P.Z. et al. Profiling the proteome-wide selectivity of diverse electrophiles. Nat. Chem. 17, 1712–1721 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01902-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01902-z

This article is cited by

-

Global profiling of arginine reactivity and ligandability in the human proteome

Nature Chemistry (2026)

-

A pipeline for proteome-wide analysis of electrophile selectivity

Nature Chemistry (2025)