Abstract

Two distinct molecular machineries, T4SS and T6SS, have been found within the order Xanthomonadales to be involved in outcompeting other bacterial species through the secretion of toxic effector proteins. However, the ecological and evolutionary basis leading xanthomonads to evolve two secretion systems with such similar functions remain unclear. Here we show that Xanthomonas translucens (Xt) lineages have switched from an X-T4SS-mediated to T6SS-i4-mediated bacterial killing strategy. T6SS-i4 was only found in Xt strains lacking X-T4SS and vice versa, resulting in a patchy distribution of the two nanoweapons along the Xt phylogeny. Using genetic and fluorescence-based methods, we demonstrated that X-T4SS and T6SS-i4 are crucial for interbacterial competition in Xt, but not Xt T6SS-i3. Combined comparative genetic and phylogenetic analyses further revealed that the X-T4SS gene clusters have been subject to degradation and had several loss events, while T6SS-i4 was inserted through independent gain events. Overall, this research supports the ancestral state of X-T4SS and provides new insights into the mechanisms promoting Xt survival within their ecological niches.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the paper and Supplementary Information and as source data files via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15367606 (ref. 69). Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to C.B. (claude.bragard@uclouvain.be). Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study can be made available on request following the signing of a material transfer agreement.

Code availability

Code for the data statistical analyses is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15367606 (ref. 69).

References

Granato, E. T., Meiller-Legrand, T. A. & Foster, K. R. The evolution and ecology of bacterial warfare. Curr. Biol. 29, R521–R537 (2019).

Booth, S. C., Smith, W. P. J. & Foster, K. R. The evolution of short- and long-range weapons for bacterial competition. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 2080–2091 (2023).

Jacques, M. A. et al. Using ecology, physiology, and genomics to understand host specificity in Xanthomonas. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 54, 163–187 (2016).

An, S. Q. et al. Mechanistic insights into host adaptation, virulence and epidemiology of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44, 1–32 (2020).

Souza, D. P. et al. Bacterial killing via a type IV secretion system. Nat. Commun. 6, 6453 (2015).

Zhu, P. C. et al. Type VI secretion system is not required for virulence on rice but for inter-bacterial competition in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. Res. Microbiol. 171, 64–73 (2020).

Bayer-Santos, E., DeMoraes Ceseti, L., Farah, C. S. & Alvarez-Martinez, C. E. Distribution, function and regulation of type 6 secretion systems of Xanthomonadales. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1635 (2019).

Sgro, G. G. et al. Bacteria-killing type IV secretion systems. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1078 (2019).

Boyer, F., Fichant, G., Berthod, J., Vandenbrouck, Y. & Attree, I. Dissecting the bacterial type VI secretion system by a genome wide in silico analysis: what can be learned from available microbial genomic resources? BMC Genomics 10, 104 (2009).

Bernal, P., Llamas, M. A. & Filloux, A. Type VI secretion systems in plant-associated bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 1–15 (2018).

Gallique, M., Bouteiller, M. & Merieau, A. The type VI secretion system: a dynamic system for bacterial communication? Front. Microbiol. 8, 1454 (2017).

Costa, T. R. D. et al. Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 343–359 (2015).

Allsopp, L. P. & Bernal, P. Killing in the name of: T6SS structure and effector diversity. Microbiology 169, 001367 (2023).

Alvarez-Martinez, C. E. et al. Secrete or perish: the role of secretion systems in Xanthomonas biology. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 279–302 (2020).

Sgro, G. G. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the bacteria-killing type IV secretion system core complex from Xanthomonas citri. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 1429–1440 (2018).

Souza, D. P. et al. A component of the Xanthomonadaceae type IV secretion system combines a VirB7 motif with a N0 domain found in outer membrane transport proteins. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002031 (2011).

Bragard, C. et al. Xanthomonas translucens from small grains: diversity and phytopathological relevance. Phytopathology 87, 1111–1117 (1997).

Goettelmann, F. et al. Complete genome assemblies of all Xanthomonas translucens pathotype strains reveal three genetically distinct clades. Front. Microbiol. 12, 817815 (2022).

Bi, D. et al. SecReT4: a web-based bacterial type IV secretion system resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D660–D665 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. SecReT6 update: a comprehensive resource of bacterial Type VI secretion systems. Sci. China Life Sci. 66, 626–634 (2023).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Heiden, N., Roman-Reyna, V., Curland, R. D., Dill-Macky, R. & Jacobs, J. M. Comparative genomics of Minnesotan barley-infecting Xanthomonas translucens shows overall genomic similarity but virulence factor diversity. Phytopathology 113, 2056–2061 (2023).

Durfee, T. et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli DH10B: insights into the biology of a laboratory workhorse. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2597–2606 (2008).

Dubois, B. et al. PRONAME: a user-friendly pipeline to process long-read nanopore metabarcoding data by generating high-quality consensus sequences. Front. Bioinform. 4, 1483255 (2024).

Bayer-Santos, E. et al. The opportunistic pathogen Stenotrophomonas maltophilia utilizes a type IV secretion system for interbacterial killing. PLoS Pathog. 15, e1007651 (2019).

Campos, P. E. et al. Herbarium specimen sequencing allows precise dating of Xanthomonas citri pv. citri diversification history. Nat. Commun. 14, 4306 (2023).

Speare, L. et al. Bacterial symbionts use a type VI secretion system to eliminate competitors in their natural host. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E8528–E8537 (2018).

Dobrindt, U., Hochhut, B., Hentschel, U. & Hacker, J. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 414–424 (2004).

Bertelli, C. et al. IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W30–W35 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Transcriptional regulator Sar regulates the multiple secretion systems in Xanthomonas oryzae. Mol. Plant Pathol. 24, 16–27 (2023).

Garin, T. et al. The type VI secretion system of Stenotrophomonas rhizophila CFBP13503 limits the transmission of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris 8004 from radish seeds to seedlings. Mol. Plant Pathol. 25, e13412 (2024).

Shen, X. et al. Lysobacter enzymogenes antagonizes soilborne bacteria using the type IV secretion system. Environ. Microbiol. 23, 4673–4688 (2021).

Yu, M., Zhang, G., Jiang, J., Du, L. & Zhao, Y. Lysobacter enzymogenes employs diverse genes for inhibiting hypha growth and spore germination of soybean fungal pathogens. Phytopathology 110, 593–602 (2020).

Fronzes, R., Christie, P. J. & Waksman, G. The structural biology of type IV secretion systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 703–714 (2009).

Soufiane, B., Sirois, M. & Côté, J. C. Mutually exclusive distribution of the sap and eag S-layer genes and the lytB/lytA cell wall hydrolase genes in Bacillus thuringiensis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 100, 349–364 (2011).

Rossi, P. et al. Mutual exclusion of Asaia and Wolbachia in the reproductive organs of mosquito vectors. Parasit. Vectors 8, 278 (2015).

Zhang, X., Kupiec, M., Gophna, U. & Tuller, T. Analysis of coevolving gene families using mutually exclusive orthologous modules. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 413–423 (2011).

Cenens, W. et al. Bactericidal type IV secretion system homeostasis in Xanthomonas citri. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008561 (2020).

Che, S. et al. T6SS and T4SS redundantly secrete effectors to govern the virulence and bacterial competition in pectobacterium PccS1. Phytopathology 114, 1926–1939 (2024).

Liyanapathiranage, P., Wagner, N., Avram, O., Pupko, T. & Potnis, N. Phylogenetic distribution and evolution of type VI secretion system in the genus Xanthomonas. Front. Microbiol. 13, 840308 (2022).

Kirchberger, P. C., Unterweger, D., Provenzano, D., Pukatzki, S. & Boucher, Y. Sequential displacement of type VI secretion system effector genes leads to evolution of diverse immunity gene arrays in Vibrio cholerae. Sci. Rep. 7, 45133 (2017).

Taillefer, B., Giraud, J. F. & Cascales, E. No fitness cost entailed by type VI secretion system synthesis, assembly, contraction, or disassembly in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 205, e0035723 (2023).

Zhang, C., Datta, S., Ratcliff, W. C. & Hammer, B. K. Constitutive expression of the type VI secretion system carries no measurable fitness cost in Vibrio cholerae. Ecol. Evol. 14, e11081 (2024).

Robitaille, S. et al. Community composition and the environment modulate the population dynamics of type VI secretion in human gut bacteria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 2092–2107 (2023).

Unni, R., Pintor, K. L., Diepold, A. & Unterweger, D. Presence and absence of type VI secretion systems in bacteria. Microbiology 168, 001151 (2022).

Gluck-Thaler, E. et al. Repeated gain and loss of a single gene modulates the evolution of vascular plant pathogen lifestyles. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc4516 (2020).

Cesbron, S. et al. Comparative genomics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Xanthomonas arboricola unveil molecular and evolutionary events linked to pathoadaptation. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 1126 (2015).

de Assis, J. C. S. et al. Genomic analysis reveals the role of integrative and conjugative elements in plant pathogenic bacteria. Mob. DNA 13, 19 (2022).

Juhas, M., Crook, D. W. & Hood, D. W. Type IV secretion systems: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and virulence. Cell Microbiol. 10, 2377–2386 (2008).

Peñil-Celis, A. & Garcillán-Barcia, M. P. Crosstalk between type VI secretion system and mobile genetic elements. Front. Mol. Biosci. 6, 126 (2019).

Morgado, S. & Vicente, A. C. Diversity and distribution of type VI secretion system gene clusters in bacterial plasmids. Sci. Rep. 12, 8249 (2022).

García-Bayona, L., Coyne, M. J. & Comstock, L. E. Mobile type VI secretion system loci of the gut Bacteroidales display extensive intra-ecosystem transfer, multi-species spread and geographical clustering. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009541 (2021).

Bayer-Santos, E. et al. Xanthomonas citri T6SS mediates resistance to Dictyostelium predation and is regulated by an ECF σ factor and cognate Ser/Thr kinase. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 1562–1575 (2018).

Choi, Y. et al. Characterization of type VI secretion system in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae and its role in virulence to rice. Plant Pathol. J. 36, 289–296 (2020).

Schäfer, A. et al. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69–73 (1994).

Choi, K. H. & Schweizer, H. P. mini-Tn7 insertion in bacteria with single attTn7 sites: example Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Protoc. 1, 153–161 (2006).

Hadfield, J. D. MCMC methods for multi-response generalized linear mixed models: the MCMCglmm R package. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v033.i02 (2010).

Jain, C., Rodriguez-R, L. M., Phillippy, A. M., Konstantinidis, K. T. & Aluru, S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 5114 (2018).

Jalili, V. et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2020 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, W395–W402 (2021).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Sokal, R. & Michener, C. A statistical method for evaluating systematic relationships. Univ. Kans. Sci. Bull. 38, 1409–1438 (1958).

Pritchard, L. et al. Pyani: whole-genome classification using average nucleotide identity. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.594921 (2015).

Rodriguez-R, L. M. & Konstantinidis, K. T. The enveomics collection: a toolbox for specialized analyses of microbial genomes and metagenomes. PeerJ Preprints 4, e1900v1 (2016).

Gilchrist, C. L. M. & Chooi, Y. H. clinker & clustermap.js: automatic generation of gene cluster comparison figures. Bioinformatics 37, 2473–2475 (2021).

Trifinopoulos, J., Nguyen, L. T., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W232–W235 (2016).

Davis, E. W., Okrent, R. A., Manning, V. A. & Trippe, K. M. Unexpected distribution of the 4-formylaminooxyvinylglycine (FVG) biosynthetic pathway in Pseudomonas and beyond. PLoS ONE 16, e0247348 (2021).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W78–W82 (2024).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Peduzzi, C. & Bragard, C. Functional replacement of ancestral antibacterial secretion system in a bacterial plant pathogen. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15367606 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank The Ohio Supercomputer Center for providing high-performance computing resources and microscope and imaging specialist D. Ignacio from Hunt Optics and Imaging Inc. Olympus for his valuable help in designing and optimizing laser scanning confocal microscope parameters for time-lapse videos. We would like to thank J. Mahillon (UCLouvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium) for his precious advice and for enriching intellectual discussions and L. M. Rodriguez-R (University of Innsbruck, Austria) for fruitful discussions. C.P. was supported by the Foundation for Training in Industrial and Agricultural Research (FRIA, FNRS) (grant no. 40021596). Part of this article is based on work from COST Action CA16107 EuroXanth, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) (C.P., R.K. and C.B.). We are grateful for support from a Fulbright Scholar Award to Uruguay to J.M.J.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.P., C.B., R.K. and J.M.J. designed the study and C.B., R.K. and J.M.J. supervised the conducted research. C.P., J.B. and F.N. performed the experiments. C.P. performed bioinformatic analyses. C.P. and M.M. performed statistical analyses. J.B., N.H. and M.V.M. assisted with the experiments and V.R.-R. and R.K. assisted with the bioinformatic analyses. C.P. wrote the manuscript and all authors discussed the results and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks William Smith and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

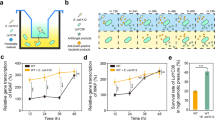

Extended Data Fig. 1 Xt (a) T6SS-i4 and (b) X-T4SS are required for inter-bacterial competition.

Representative NA plates with tenfold dilution series of the quantitative assay showing E. coli survival using Amersham Typhoon laser scanner.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Xt growth is not impacted by (a) T6SS and (b) X-T4SS mutations during bacterial competition assays against E. coli.

Quantitative competition assay with E. coli mixed in a 10:1 ratio (Xt:E. coli) for 10 h of co-cultivation. Boxplot represents Xt growth log CFU/ml after 0 h and 10 h of co-cultivation. All boxplots show 1st and 3rd quartiles around the median. Whiskers represent the smallest and largest value no further than 1.5 * IQR (inter-quartile range) from the hinge. Dots indicate independent biological replicates (n = 2 at 0 h; n = 6 at 10 h). Significance was tested by two-sided Student’s T-test. Significance codes: *** (P < 0.001), ** (P < 0.01), * (P < 0.05), only significant comparisons are shown (ΔT6SS-i3: P = 1, ΔT6SS-i4: P = 1, ΔT6SS-i3 ΔT6SS-i4: P = 1, Δhcpi3: P = 1, Δhcpi4: P = 1, Δhcpi3 Δhcpi4: P = 1, and Δhcpi4::hcpi4: P = 1; ΔvirD4: P = 1, and ΔvirD4::virD4: P = 1).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Phenotypic characterization of Xt UPB513 T6SS and X-T4SS mutants.

(a, b) In vitro growth curve of (a) Xt UPB513 WT and derived strains mutated in and complemented for T6SS, (b) Xt LMG728 WT and derived strains mutants in and complemented for T4SS, in NB medium at 28 °C, OD600 measured at 45-minute intervals. Dots represent mean and error bars show s.e.m (n = 8 replicates per strain). (c) Barley cv. Hercule leaves infiltrated with Xtu UPB513 WT or T6SS mutants show water-soaking and necrotic lesions at 6 dpi (n = 8 plants).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Xt T6SS-i4 and X-T4SS are required for inter-bacterial competition against Pseudomonas sp. and Pantoea sp.

Representative qualitative competition plate using Xt UPB513 WT, Δhcpi4, Xt LMG728 WT and ΔvirD4 as attacker cells and Pantoea agglomerans UPB1357 and Pseudomonas sivasensis UPB1354 Tn7::mNeonGreen as target cells after 16 h of competition on NA.

Extended Data Fig. 5 VirB8-based phylogeny reveals xanthomonads with atypical X-T4SS sequences.

(a) The phylogenetic tree was constructed using autoMLSA2, by extracting and aligning VirB8 amino acid sequences from each type/pathotype strain of each Xanthomonas species and pathovar possessing X-T4SS and using IQ-TREE to infer the phylogenetic tree. (b) Comparison of the T4SS gene clusters from X. campestris pv. incanae and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Most X-T4SS genes (except for virD4) of strain CFBP 1606 share higher sequence identity with the corresponding genes from strain X28 than with those in strain WHRI 8527.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Various decay and loss events occurred in the X-T4SS clusters.

The tree on the left side is based on average nucleotide identity (ANI) of Xt strains, whereas the right side provides an overview of the organization of the X-T4SS gene clusters and their neighboring genes uvrB and thrS. Letters and numbers above the genes correspond to the virD and virB genes. Scales for distance and percentage identity between genes are indicated below. Genes are color-coded according to homology. Pseudogenized genes are highlighted with an asterisk. Fragments of remnant X-T4SS genes are found within the corresponding genomic location in the X-T4SS-lacking strains. The three ANI clades Xt-I, Xt-II and Xt-III are indicated in the tree.

Extended Data Fig. 7 X-T4SS-lacking strains possess T4E-T4I pairs.

Comparison of candidate X-T4SS effector-immunity pairs across strains possessing either X-T4SS, T6SS-i4, or none of them. The asterisk indicates an in-frame STOP codon.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Incongruency between the T6SS-i4 and the pan-genome tree topology of strain Xt LW16 is caused by the tssM gene.

Comparison between species (left) and T6SS-i4 (right) phylogenies. The pan-genome SNP-based tree was constructed using kSNP3 (kmer of 23 bp). The T6SS-i4 tree was inferred by maximum likelihood using IQ-TREE based on concatenated alignment of tssA, tssB, tssC, tssD, tssE, tssF, tssG, tssH, tssK, tssL, (a) with or (b) without tssM genes. Amino acid sequences were aligned by ClustalW. The bootstrap supports were estimated based on 1000 replicates. Trees were visualized with iTOL.

Extended Data Fig. 9 T6SS-i4 and ICE in type-2 neighborhood are flanked by att sites in strains (a) Xcg T8, (b) Xt 01, Xt UPB886, Xt UPB820 and (c) Xce LPF602.

(Upper panel) Genes corresponding to the same ICE modules are represented in similar colors. Genes with unknown functions are indicated in gray. attL and attR sites flanking the GI and attP in the T6SS-i4 lacking strain are pointed with red bars. (Lower panel) attL, attR and attP sites sequences are shown, 16-bp direct repeat sequences are boxed with dashed lines and tRNA-Gly sequences are underlined.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–9, Tables 1–5 and Legends for Videos 1–16.

Supplementary Video 1

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 2

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 3

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 4

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 5

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 6

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 7

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 8

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens WT. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 WT, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt: to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 9

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 10

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 11

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 12

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 13

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 14

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 15

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Supplementary Video 16

Real-time monitoring of T6SS bacterial killing activity in X. translucens T6SS-i4 mutant. Time-lapse video of Xt UPB513 ΔT6SS-i4, expressing RFP in competition with E. coli DH10B expressing GFP, mixed in a 10:1 (Xt to E. coli) ratio, on solid agarose pad (25% LB). Bar representing 10 μm is shown on the right, while magnification and time are indicated on the left. Pictures were taken every 6 min for 4 h 48 min.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Peduzzi, C., Butchacas, J., Nikis, F. et al. Functional replacement of ancestral antibacterial secretion system in a bacterial plant pathogen. Nat Ecol Evol 9, 1393–1404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02773-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02773-w