Abstract

While decarbonizing road transport is crucial for global climate goals, there is limited quantitative evidence on the economic viability and life-cycle emissions of low-carbon passenger vehicles in Africa, where motorization is rising. Here we study the economic cost and life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of low-carbon passenger transport in Africa across six segments in 52 African countries through 2040. Using Monte Carlo and optimization models, we compare the total cost of ownership and life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of battery electric vehicles powered by solar off-grid systems and synthetic fuelled vehicles to that of fossil-fuelled ones, neglecting policy-induced cost distortions. Whereas past reports suggested fossil fuel vehicles would dominate in Africa by mid-century, our results show that battery electric vehicles with solar off-grid chargers will have lower costs and negative greenhouse gas abatement costs well before 2040 in most countries and segments. Financing is identified as the key action point for governments and global financial institutions to accelerate Africa’s transition to battery electric vehicles with solar off-grid charging offering a cost-effective, viable solution to electricity infrastructure challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Decarbonizing road passenger transport is crucial for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions globally1. Passenger vehicles are a major contributor to road transport emissions2. Advances in battery technology, manufacturing and supportive policies are driving battery electric vehicle (BEV) adoption, while synthetic fuels are also being explored as a complementary low-carbon option3,4, notably by major automakers such as Volkswagen5. Policies in advanced markets such as Europe and California aim to fully electrify new car sales by the 2030s, with some exceptions for carbon-neutral synthetic fuel vehicles6,7.

However, much of the momentum around BEV deployment and low-carbon transport policy strategy more broadly has thus far been concentrated in upper middle- or high-income economies such as China, the European Union and the USA. In contrast, African countries have often been overlooked or simplified in global energy and transport models. Several influential studies assume continued internal combustion engine (ICE) dominance in Africa through mid-century, often disregarding local conditions for a transition to electric mobility4,8,9. Where passenger transport electrification in Africa has been examined, research is typically limited to case studies of single countries or application segments8,9,10,11,12. Furthermore, existing techno-economic projection models rarely reflect context-specific factors, such as high financing costs or limited grid access, when calibrating vehicle ownership or technology competitiveness parameters for Africa13.

For instance, many African countries face high up-front investment costs due to limited access to stable and affordable financing14,15, disproportionately disadvantaging low-carbon technologies with substantial up-front investment requirements. Despite this, regional differences in financing costs, development objectives and uncertainties in energy system trajectories are seldom accounted for in models13,16,17. Similarly, projections frequently rely on grid-connected technologies for decarbonization, neglecting both power grid constraints and the potential of solar off-grid or hybrid mini-grid systems. These alternatives are expected to play a pivotal role in electrifying current and future settlements and residential areas in Africa14 and illustrate the limitations of overlooking Africa’s unique conditions and clean energy future. This can ultimately distort model projections and hinder the development of effective policy for transitioning to low-carbon passenger transport in the region. With vehicle demand projected to rise steeply across nearly all African countries by 205018, assessing the continent’s road transport decarbonization potential is crucial for global net-zero goals.

To address these shortcomings, our study investigates which technologies may suit specific segments and in which timeframes though a continent-wide analysis combining a probabilistic total cost of ownership (TCO) analysis with a prospective environmental life-cycle assessment (LCA). Unlike previous studies, our model incorporates country-specific financing costs and the potential of solar off-grid (SOG) charging systems to improve cost projections across a wide range of countries and vehicle segments in the African context. Our results show that BEVs charged by a solar photovoltaic off-grid (SOG) system meeting their daily energy demands will outperform ICE vehicles for passenger road transport in the African continent, in some cases already by 2030. In short, the cost of reducing emissions from passenger road vehicles per km becomes not only economically viable but also negative. For accelerated adoption, financing costs remain the primary barrier to the economic competitiveness of BEVs in the region. We therefore discuss how they may be alleviated by local policymakers and development financial institutions.

Total cost of ownership across technologies

To evaluate the viability of low-carbon passenger road vehicles in Africa, we conduct a probabilistic TCO analysis using a Monte Carlo method. The analysis compares three competing technologies: ICEs fuelled by fossil fuels (ICE-Fos), ICEs fuelled by synthetic fuels (ICE-Syn) and BEVs paired with a standalone SOG system (BEV-SOG). The BEV-SOG system concept overcomes grid infrastructure limitations in many African countries, where unreliable electricity supply is a common challenge. We focus on BEV-SOG systems due to their scalability, transparent and modular costs, minimal land requirements, lower life-cycle emissions in fossil-heavy grids and growing use in off-grid energy and transport applications across Africa19,20. We assume charging through a solar PV off-grid system sized to meet the vehicle’s daily energy demand, depending on the application segment (Methods). The SOG set-up assumes a solar PV panel (DC) connected to a stationary battery (DC), with both components feeding into an inverter. In contrast to BEV-SOG, ICE-Syn vehicles may leverage existing fuelling infrastructure. Hydrogen-powered passenger vehicles are excluded from the analysis due to their limited uptake in other countries21.

Our analysis focuses on six distinct passenger vehicle application segments most relevant for the African landscape: two-wheelers (small and large), four-wheelers (small, medium and large) and a minibus segment representing informally operated ‘public’ transport vehicles. Driving patterns modelled within each segment are primarily urban-centric, though we account for potential rural and off-road usage by incorporating high probabilistic uncertainty in vehicle energy consumption and in annual kilometres travelled, which are differentiated by application segment (Methods). Notably, we exclude commercial passenger fleets, such as taxis, due to their distinct on-road usage patterns, commercially driven financing structures and differing purchase decision rationales, though these are some of the earlier segments to electrify in the region as they profit most from lower BEV TCO22. The model projects costs for three time horizons—2025, 2030 and 2040. Despite playing a prominent role in African vehicle markets, we evaluate only new vehicles due to lack of reliable used vehicle data, particularly for BEVs but also for ICEs.

Importantly, this TCO assessment excludes policy-induced costs such as taxes, import fees and subsidies aligning with an approach that focuses on resource costs. It does not incorporate externalities related to road transport, typically included in social cost evaluations. In this sense, the results of our analysis provide a policy baseline, offering a reference point against which the effects of future policies can be assessed. Additionally, financing is assumed to follow third-party ownership—that means, we take the financing cost faced by a leasing company, financial institution or fleet operator, rather than by a private individual. This set-up simulates what would be expected in a well-working market that operates without policy distortions and where vehicles are predominantly owned by third parties. For financing cost assumptions, we follow the approach from Agutu et al.14, who provide country-specific weighted average cost of capital (WACC) estimates for energy investments in sub-Saharan Africa that account for key risk premiums. We adapt their approach to reflect the comparable risk profile of third-party owned BEVs with slight parameter adjustments (Methods). Beyond TCO, we also quantify life-cycle GHG emissions of all technologies applying the prospective LCA framework premise23, to account for future technological and market developments under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway 2 (SSP2) scenario from the integrated assessment model REMIND24 extrapolated till the respective year (Methods). On the basis of lifetime TCO and life-cycle GHG emissions, we quantify life-cycle GHG abatement costs.

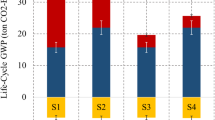

We begin by visualizing results across technologies, for the representative small four-wheeler segment averaged across Africa, then expand the analysis to explore cross-country and cross-application variations. Figure 1 breaks down the TCO and life-cycle GHG emissions for the three vehicle technologies in the small four-wheeler segment for the year 2030, additionally showing TCO bars for 2025 and 2040 in Fig. 1a–c. To first compare BEV-SOG with ICE-Fos, we see that BEV-SOG vehicles remain uncompetitive in 2025, but by 2030, our model projects economic competitiveness on a TCO basis with ICE-Fos. Looking ahead to 2040, projected advancements in battery technology and electric vehicle manufacturing, coupled with reduced financing costs (Methods), further improve the economics of BEV-SOG, thus dropping the TCO below US$24 per 100 km (Fig. 1b). As shown in Fig. 1e, financing costs are the most critical factor for BEV competitiveness, with total financing expenditures surpassing 100% of the vehicle’s capital cost. Furthermore, on a life-cycle GHG emissions basis, BEV-SOG substantially outperform ICE-Fos vehicles. By contrast, we project that ICE-Syn will remain rather uncompetitive compared to BEV-SOG on both a TCO and GHG emissions basis, even in our idealized extreme case where synthetic fuel is produced as cheaply and cleanly as possible.

a–c, TCO bars for each technology in model years 2025, 2030 and 2040. ICE-Syn vehicles are not shown for the year 2025 as we assume a functioning synthetic fuel market only by 2030. d–f, Waterfall charts for TCO components for all technologies in 2030. g–i, Waterfall chart for life-cycle GHG emissions for all technologies in 2030 broken into vehicle production and operation emissions. Operation emissions of fossil fuels include combustion and fuel production and supply to the pump. Operation emissions of BEVs include embedded emissions of the SOG system, which are minor. Combustion emissions of synthetic fuels are assumed to be CO2 neutral. For the life-cycle GHG emissions comparison, 225,000 lifetime kilometres are assumed for all technologies within the small four-wheeler segment. Bars in a–f show the mean country-level values weighted by motorization rate across 52 countries; error bars indicate one standard deviation. Estimates are based on 10,000 Monte Carlo draws per country. Bars in g–i show mean emissions intensities (across two SSP2 scenarios); error bars mark high–low range. Values are uniform across countries; no Monte Carlo applied. The ‘vehicle operation’ GHG emissions for ICE-Syn in i represents the life-cycle GHG emissions to produce and transport to the African continent the required amount of synthetic fuel for the assumed lifetime km travelled (Methods). CAPEX, capital expenditure; CoC, cost of capital; O&M, operation and maintenance costs.

BEV cost competitiveness across dimensions

Zooming out, our model results reveal that the competitiveness of BEV-SOG and ICE-Syn technologies against ICE-Fos varies greatly across application segments, countries and timeframes, where several key patterns emerge. Here we focus on the comparison between BEV-SOG and ICE-Fos, as ICE-Syn has already been shown to be uncompetitive both economically and environmentally. Over time, BEV-SOG is projected to achieve cost competitiveness across all passenger vehicle segments by 2040 (Fig. 2m–r), and in some segments already by 2030, driven largely by rapid reductions in vehicle capital expenditure (CAPEX). These findings challenge conservative estimates from prominent sources25,26, though our results are notably here modelled absent cost distortions such as taxes or duties. Differences across application segments further highlight the complexity of the transition. Two-wheelers achieve BEV-SOG cost competitiveness already by 2030 while larger vehicles, particularly small and medium four-wheelers, lag behind—mirroring EV adoption trends in developed and emerging economies25. Country-level disparities, largely driven by financing costs, further delay economic feasibility, underscoring the importance of financial de-risking. Overall, BEV-SOG competitiveness is uneven across model dimensions. The small four-wheeler segment warrants particular focus for accelerated BEV uptake and may benefit from lessons learned in the faster-adopting two-wheeler market.

a–r, Colour scale unit for each country shows the TCO percentage difference of BEV-SOG and ICE-Fos vehicles. Countries displayed in dark grey (Djibouti, Seychelles and Western Sahara) are not modelled. Supplementary Fig. 1 provides TCO comparison of ICE-Syn vs ICE-Fos vehicles. Maps generated using Cartopy (https://scitools.org.uk/cartopy) with data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

Key drivers of technological competitiveness

TCO parameters that influence the competitiveness of the two low-carbon vehicle technologies (Fig. 1d–f) are the following. For BEV-SOG, our model indicates that vehicle financing costs (Vehicle CAPEX CoC) considerably impede the economics of BEV-SOG in Africa, not only in the small four-wheeler segment, as shown in Fig. 1e, but also in the other four-wheeler and minibus segments. In some segments, financing costs can surpass 150% of the vehicle’s capital expenditure (CAPEX), driving up the TCO. In contrast, model results show that charging costs for BEV-SOG are relatively minor, contributing less than 4% of the TCO for small four-wheelers in 2030, despite the modelling set-up, which assumes outright purchase of the SOG together with the vehicle. This outcome largely reflects the efficient sizing of the SOG, which our nonlinear optimization model specifically calibrates to supply at least 90% of the annual energy demanded of each vehicle application segment. The optimized SOG capacity is based on a minimum reliability of 90%, under niche financing cost assumptions, with an additional 40% system oversizing to account for potential extremes in daily use cases (Methods). For a small four-wheeler assumed to drive ~50 km per day, the SOG costs ~US$2,700 (including installation costs). Despite these conservative assumptions, SOG electricity cost as a portion of the TCO remains low, highlighting the affordability and potential of off-grid charging for electric vehicles. Figure 3 demonstrates the results of our SOG sizing optimization, depicting the pan-African levelized cost of charging (LCOC) in high resolution. Comparing these results to the average grid-based electricity price for all countries in Africa in 2022, inclusive of all taxes and duties (Supplementary Fig. 5), SOG charging costs appear to be quite reasonable.

Countries displayed in white (Djibouti, Seychelles and Western Sahara) are not modelled. Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3 provide undistorted LCOC projection maps of the African continent in 2030 and 2040. Map generated using Cartopy (https://scitools.org.uk/cartopy) with data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

For ICE-Syn vehicles, fuel cost remains a critical limitation and uncertainty. Our model follows an extremely optimistic scenario, assuming ultra-low-cost synthetic fuel production in the Chilean desert, where the renewable energy potential is high and financing conditions favourable. Nevertheless, ICE-Syn vehicles face higher TCO when compared to both BEV-SOG and ICE-Fos vehicles. Doubling the assumed production cost of synthetic fuel—a reasonable scenario—would increase the ICE-Syn TCO by US$10 per 100 km, reaching over US$40 per 100 km for the small four-wheeler segment in 2030. On the fuel cost side for ICE-Fos vehicles, as our analysis assumes a global benchmark cost reflecting today’s functioning oil market but excludes fuel taxes, we model a relatively low average gasoline price across the continent (Methods). Whereas some countries in Africa heavily subsidize fossil fuels at the pump (for example Sudan, Algeria), most countries tax, meaning the distorted fuel prices are higher than here modelled (Supplementary Fig. 4), again giving ICE-Fos an economic advantage over BEV-SOG in our analysis.

A Sobol sensitivity analysis of TCO model parameters, illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 6–11, reveals that financing cost is among the most influential variables, accounting for nearly 10% of the first-order variance in the TCO difference between BEVs and ICEs in most application segments. Vehicle CAPEX, annual kilometres travelled (AKT) and vehicle operations and maintenance (O&M) are other key parameters impacting total output variance, closely followed by parameters related to the vehicle’s consumption of total energy, namely lifetime kilometres travelled, energy efficiency and energy cost. Given the uncertainty in real-world usage patterns and the associated AKT input parameter, we conduct an extended sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figs. 12–23), running the model under extreme high and low AKT assumptions. The results indicate that large AKT variation has only a modest impact on comparative vehicle cost and emissions outcomes as compared to base assumptions.

Off-grid solar electric vehicles exhibit substantially low GHG emissions

From a life-cycle GHG emissions perspective (Fig. 1g–i), BEV-SOG decisively outperforms both internal combustion engine vehicles, a finding that has previously and consistently been confirmed for other regions in the literature27. Our model projects this trend already from today (Supplementary Figs. 24 and 25 for 2025 and 2040).

By 2040, the analysis indicates that for all countries and all segments within the study, BEV-SOG exhibits a negative GHG abatement cost—within a margin of error (Supplementary Fig. 24). This result implies that in the absence of policy-induced distortions, the cost of reducing emissions from passenger road vehicles per km travelled in Africa not only becomes economically viable but also represents a net saving. In Fig. 4, we present GHG abatement cost results for the small four-wheeler segment across all model years, emphasizing the critical role of financing costs. By 2040, negative GHG abatement costs are achieved in all countries, reflecting the economic and environmental advantages of BEV-SOG. However, by 2030, only one country reaches this mark. Reducing financing costs, which are highly correlated with abatement costs, could enable more countries in this segment to achieve negative abatement costs by 2030. For ICE-Syn vehicles, the GHG abatement costs across all applications and countries remain positive even in 2040 (Supplementary Fig. 25).

Coloured bars represent the life-cycle GHG abatement cost for BEV-SOG in the years 2025, 2030, 2040 calculated as the TCO difference (US$ per km) divided by the difference in life-cycle GHG emissions (tCO2eq per km), which ensures that the denominator remains positive in all cases. Red dots indicate the financing cost for BEV-SOG vehicles in each country in 2025. Countries are ordered top down according to the life-cycle GHG abatement cost in 2025, largest to smallest. Supplementary Figs. 24 and 25 provide life-cycle GHG abatement cost model results in all application segments and time periods, comparing both BEV-SOG and ICE-Syn with ICE-Fos vehicles.

Overcoming financing costs for off-grid solar electric vehicles

As previously shown, financing costs emerge as the most critical factor influencing TCO competitiveness of BEV-SOG vehicles. To further explore this barrier in the small four-wheeler segment, we model the ‘maximum’ financing cost required in each country for BEV-SOG to achieve cost parity with ICE-Fos vehicles by 2030 (Fig. 5), using linear bisection optimization (Methods). Our findings reveal large variation across countries. In lower-risk states such as Botswana, Mauritius and South Africa, the financing conditions today are already close to required levels for BEV-SOG cost parity. Conversely, in higher-risk countries such as Sudan, Guinea or even Ghana, financing costs would need to be reduced by 7–15 percentage points to achieve parity within the same timeframe. Figure 5 highlights these disparities not to suggest a need for subsidies, but to emphasize the importance of targeted de-risking measures. While subsidies that reduce up-front costs may improve affordability, they do not fundamentally lower the investment risk associated with EV markets in the region. True de-risking requires addressing the barriers that make EV investments riskier in many African economies.

The solid red dot represents the BEV–SOG financing cost in 2030; the hollow red circle represents the maximum BEV–SOG financing cost in 2030 for which the TCO equals that of ICE-Fos vehicles.

Discussion

The results of this study hold important implications for African policymakers and international (finance) institutions. We highlight three key implications. First, the transition to electric vehicles in Africa makes sense from both a cost and life-cycle GHG emissions perspective, particularly when considering SOG systems. Reducing emissions from passenger road vehicles in Africa is both economically viable and cost saving, well before 2040. In fact, BEVs would appear cost competitive by 2030 were it not for elevated financing costs—under a cash-purchase scenario, they would already present a financially viable option. On the basis of these findings, policymakers can decide to lay the groundwork proactively, with local policy support focusing on addressing key adoption barriers including vehicle and charging-infrastructure availability, which drive high financing costs. Second, charging using SOG systems adds minimally to the total cost of BEV-SOG ownership while also circumventing the need for expensive grid upgrades. Ensuring widespread availability and access to off-grid charging options remains a challenge, though not an impossibility, given the increased battery and solar PV manufacturing capacity globally. Third, synthetic fuel vehicles are unlikely to serve as a viable transition technology for Africa. Even under optimistic cost assumptions, synthetic fuel vehicles fail to compete economically or environmentally with BEV-SOG vehicles. Moreover, the uncertainty surrounding large-scale availability of low-cost synthetic fuels further diminishes their feasibility. These fuels are better suited for hard-to-abate sectors, whereas passenger road transport in Africa may rather be electrified.

We discuss several policy considerations that emerge from these implications. First, to accelerate the electrification of personal road transport in Africa well before 2040, financial de-risking should be addressed. Here we outline key observations and potential solutions, though recognize that further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of financial de-risking mechanisms for electric mobility in Africa. On the upside, traditional de-risking measures—such as guarantees, concessional capital and blended finance—may work better for electric vehicles than for development finance in other sectors. Namely, financial de-risking of electric vehicles could be led by the private sector, which can help to establish early trust in technologies such as electric two-wheelers in low-risk contexts and pave the way for public sector involvement in higher-risk countries later. Further, the private sector could also take the lead in building pan-African portfolios to help spread risk across countries, starting again with lower-risk countries that may also have higher ‘EV readiness levels’28. Building on this point, as both cars and charging stations are highly standardized products, this allows for packaging of vehicle loans into securities and placing them, for example, as corporate green bonds. This could bring down the overall risk of the package, which could then be included in the portfolios of higher-risk countries such as Sudan or Niger. Multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank or the African Development Bank and impact investors should support in building these portfolios and structuring packaged securities. Here specifically, further research is required to understand mobility sector financing in high-risk countries and the role of private vs public institutions.

Second, given the cross-country heterogeneity of our results, tailored policy solutions may look quite different depending on the relative preparedness of the country or on the application segment. With the assumed off-grid charging set-up in our analysis, low-risk but also high-solar-energy-availability countries such as Botswana and Namibia or even Kenya and Ethiopia may require comparatively less direct policy support for increased BEV adoption by 2030. In these countries, private sector development of e-mobility business models for increased BEV adoption and charging such as battery swaps (for example, Ampersand, Powerhive) or pay-as-you-go (for example, Ecobodaa) is not only crucial for development of a home BEV market, but already evident. Conversely, less-prepared countries such as Sudan, Mauritania and the DRC may require greater policy support to ensure BEV availability through incentives (for example, subsidies, import tax exemptions) and ICE disincentives (for example, fuel taxes, phased-out sales or bans such as in Ethiopia). Alongside de-risking, governments can adopt complementary measures such as targeted subsidies, import duty exemptions, or carbon taxes or bans on ICE vehicles. These policies should be cost-conscious—using caps or periodic reviews—as BEV prices decline. In the longer term, policies such as ICE scrappage programmes or sales bans can support full fleet turnover. Scrappage schemes paired with purchase subsidies may also improve equity by supporting lower-income buyers. Careful policy sequencing and regular evaluation will be key to balancing adoption goals with fiscal sustainability.

In particular, our analysis shows that policies that directly target up-front vehicle costs—such as an increase in purchase subsidies or a decrease in import duty exemptions, or financial de-risking instruments (for example, guarantees)—are most effective in accelerating domestic BEV adoption. To enhance fairness, limiting such incentives to small four-wheelers rather than larger, higher-end models could spur uptake among first-time buyers in lower- and middle-income brackets. In the medium term, higher-level regulatory measures, for example, planned bans on ICE vehicle sales, can serve as important complements to these policies, and targeted incentives and investment in charging infrastructure will be critical to ensuring that the diffusion of BEVs continues29,30. On the charging-infrastructure side, countries may adopt diverse approaches, with grid-based solutions suitable for some urban areas and standalone solar systems more practical in rural settings, and perhaps in urban ones. Effectively implementing these solutions would require careful planning31, particularly as infrastructure needs and energy demands vary across regions.

Finally, our results indicate that BEVs may become cost competitive independent of policy or financial assistance well before 2040 across all countries and segments. For countries where climate policy is not a top development priority, a reality for many economies in the global south32,33, waiting rather than taking early action on the BEV transition may be preferable as the global shift towards electrification will naturally drive down BEV costs without requiring local intervention. Further, transitioning to BEVs offers clear economic, environmental and energy-system co-benefits for African societies which could be reaped sooner by addressing BEV adoption barriers now. One potential co-benefit is the development of a local BEV manufacturing industry, which would require targeted efforts to establish vehicle assembly lines, integrate a sustainable supply chain and build a skilled workforce. African policymakers could incentivize this through tax breaks, subsidies or low-interest financing. However, they must also recognize the challenge of competing with low-cost Chinese manufacturing. For African countries committed to climate goals, our results provide strong justification for setting more ambitious transport sector climate targets for 2050.

Several future research areas remain. Importantly, we note that the exclusion of all cost distortions is a major assumption that can affect the competitiveness of BEVs in African markets. Our extended sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Figs. 26–28) highlights the implications of this assumption. In particular, the omission of vehicle import duties represents a key limitation of our study, as such duties are known to be high in several African countries, which can negatively impact the BEV TCO. This underscores the need for future research to investigate how policy-induced costs may affect BEV competitiveness on a country-specific basis. Next, the availability of BEV maintenance infrastructure and technical expertise is not captured in our quantitative model and requires further empirical research. Presently, most BEV owners in Africa rely on grid-based charging, yet our analysis focuses on solar off-grid system charging. To evaluate the impact of grid electricity prices on BEV TCO competitiveness, we conduct a sensitivity analysis with BEVs charged directly from the grid (Supplementary Figs. 29–31), to highlight that even high grid prices have minimal effects on most vehicle segments, with the minibus segment being the notable exception. Additionally, the second-hand vehicle market presents a crucial area for further study. The emergence of a second-hand BEV market—though currently absent—could transform affordability and access, with businesses already developing strategies in preparation34. Notwithstanding some concern and discussion around future resource limits of BEV demand and subsequent production35,36,37,38, this dynamic is only expected to grow as international export flows of used BEVs increase (namely from China)39, warranting dedicated analysis. Indeed, in the near term, the continued inflow of cheap, used ICE vehicles may delay the transition by undercutting BEV demand40. Moreover, growing regulatory pressure in manufacturing regions such as China and the European Union to retain and recycle EV batteries could limit the export of used BEVs to Africa41,42. How these dynamics will evolve remains uncertain and requires further research. Lastly, societal co-benefits of BEV adoption, such as the potential reduction of local air pollution, are critical yet understudied aspects in the African context.

Methods

Total cost of ownership calculation

The TCO is a comparative lifetime cost metric widely employed by transport modellers to assess technology competitiveness in both the passenger and commercial vehicle segments43,44,45,46,47. Here we evaluate passenger vehicle TCO for three technologies, in six application segments, 52 African countries and three time horizons. We follow the TCO methodology from Noll et al.45, which builds on two other studies39,43,and adjust parameters to fit the context of our study.

where TCO is the total cost of ownership per kilometre (US$ per km), CAPEX is the capital expenditure or initial purchase cost of the vehicle and the SOG system (only for BEV-SOG) (US$), RV is the residual value of the vehicle, OPEX is the operating expenditure or annual operating cost of the vehicle and the SOG system (only for BEV-SOG) (US$), N is the lifetime of the vehicle (years) and AKT is the annual kilometres travelled. For the discounting terms, CRF is the capital recovery factor \(=({i\left(1+i\right)}^{N})/({\left(1+i\right)}^{N}-1)\), and i is the financing cost. The CRF represents the factor used to annualize the vehicle CAPEX over its lifetime, accounting for the financing cost and ensuring the total purchase cost is distributed evenly across the vehicle’s operational years. Subscripts t, a, c and y refer to the technology, application, country and year dimensions, respectively.

All model input parameters, their dimensional dependence (technology, application, country), type of Monte Carlo simulation (probabilistic or deterministic) and type of projection (dynamic or static) are displayed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

The CAPEX consists of the vehicle cost for all technologies and the SOG component costs for the BEV-SOG technology only as in equation (2).

The vehicle CAPEX (in US$) is assumed to be the same across all modelled African countries as we remove all taxes, fees and import duties, reflecting the resource cost for vehicle production. Vehicle CAPEX costs are dynamic in time and probabilistically determined. Note that we do not include battery replacement over the lifetime of the vehicle, owing to the fact that modern vehicle batteries are now capable of at least 15 years of operational lifetime48. The section on vehicle CAPEX database and projections and Supplementary Table 3 provide further detail.

The SOG CAPEX consists of four hard-cost components, the solar PV panel, inverter, stationary lithium-ion battery and balance of system (BOS), and one soft-cost component, installation. Each hard-cost component is sized to the application-specific use case in the SOG sizing optimization model (details below). Costs for the solar PV panel (in US$ per kWp), the inverter (in US$ per kWp) and the BOS hardware (US$ per system unit), current and projected, are sourced from the Danish Energy Agency’s technology catalogue report on Technology Data for Generation of Electricity and District Heating49. For the stationary battery we use current and projected costs (in US$ per kWh) based on data from BloombergNEF’s (BNEF) automotive battery price survey50 and use a 150% cost multiplier given that stationary lithium-ion battery packs deployed in electricity-sector applications are typically 50% above the reported cost for automotive packs51. We project lithium-ion battery pack costs using a 22% learning rate, calculating future costs based on an own extrapolated demand scenario projection between BNEF’s base case ‘economic transition scenario’ (ETS)52 and their ‘green scenario’, which depicts optimistic growth of renewable electricity and green hydrogen53. This own extrapolated demand projection is therefore neither conservative nor optimistic but rather assumes a medium future battery demand across all use applications globally. Initial cumulative capacity of lithium-ion battery packs for the base year 2025 is an own estimate based on data from BNEF50 and Avicenne Energy54,55. Taking results from the SOG sizing optimization model, we multiply unit cost for each of the SOG components by their optimized capacity to calculate system capital expenditure. We also include an installation cost, which is assumed a constant 25% of the capital expenditure for all SOG components, based on discussions with local service providers in Ghana, Namibia and South Africa and relevant literature and sources56,57,58. Additionally, we assume a 40% oversize factor for all hard-cost components to account for potential extremes in daily use cases. Overall, this gives a total cost for the SOG system of US$400–550 for a 0.35 kWp solar + 0.825 kWh battery system for the two-wheeler segment, US$2,500–3,500 for a 2.5 kWp solar + 6.0 kWh battery system for the four-wheeler segment and US$7,500–8,500 for a 7 kWp solar + 17 kWh battery system for the minibus segment in 2025. In Supplementary Note 1, we compare these cost ranges with real-world quotations and market estimates, demonstrating that our assumptions are reasonable. An overview of SOG cost and system parameter assumptions is available in Supplementary Table 4.

Vehicle residual value is determined as the share of purchase price (CAPEX) remaining after vehicle use over a certain distance. We use vehicle depreciation percentages based on BNEF’s ‘vehicle total cost of ownership model’ 59 and fit these to an exponential function for all case countries as in equation (3)

where \(y\) is the residual value factor (in %), \(x\) is the total lifetime vehicle mileage, \(a\) and \(b\) are fitting factors specific to each case country and \({y}_{0}\) and \({x}_{0}\) are initial value factors. Because the depreciation percentages from BNEF’s vehicle TCO model are applicable primarily for four-wheelers, different fitting factors are determined for the two-wheeler and minibus segments such that the vehicle maintains between 8–10% residual value at the end of its operational lifetime. Residual value fitting factors are constant over time and deterministic.

The OPEX parameter includes the following components—fuel costs (both fossil fuel and synthetic fuel), vehicle operation and maintenance (O&M) costs, insurance costs and SOG O&M costs (only for BEV-SOG) as in equation (4).

For the undistorted fossil fuel cost (that is, absent all taxes and duties), we follow the approach from Ross et al.60, which involves selecting a global benchmark cost, such as international spot prices for motor fuels, to determine the unsubsidized fuel cost. Here we select conventional refined gasoline at the New York harbour (in US$ per gallon) as the benchmark cost as reported by the US Energy Information Agency (EIA)61. A volumetric conversion factor of 3.785 litre per gallon is used. To introduce stochastic uncertainty, we establish a normal distribution taking the most recently available data, 2024 average conventional refined gasoline (in US$ per litre), as the mean and the standard deviation of three, three-year period averages before 2024 (2021–2023, 2018–2020, 2015–2018) as the standard deviation for the model base year. Additionally, we assume a constant shipping and distribution margin of US$0.10 per litre on top of the benchmark, as the cost of bringing refined gasoline to retailers60. Distribution costs are assumed to be constant across all African countries and constant over time. Future fossil fuel costs are then derived based on unrefined crude oil cost projections from the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) World Energy Outlook. We assume an average crack spread of US$0.5 per gallon to convert the IEA crude oil projections to the refined gasoline benchmark cost, based on historical crack spread averages. For crude oil projection costs, we follow the IEA’s stated policies scenario. Supplementary Table 5 provides fossil fuel costs.

For synthetic fuel costs (in US$ per litre), we source minimum selling price (MSP) data from the meta-analysis by Allgoewer et al.62, taking values from the ‘Chile near-term future scenario for 2030’ and the ‘long-term future scenario for 2040’. For both scenarios, the MSP range reflects a combination of the lowest and the highest possible MSP by combining the different sources with respective projections. We use this range to form a normal distribution, with the mean value corresponding to the midpoint between the lowest and highest MSP values. The MSP includes the transportation of fuel to the final location62. The interest rate assumed for Chile was 4.6% (ref. 62). Synthetic fuel costs are not differentiated by application or country of use. Supplementary Table 5 provides synthetic fuel costs.

Vehicle O&M costs (in US$ per year) are sourced from ref. 47. They are differentiated by application but not by country, are static over time and probabilistically determined based on empirical data from ref. 47 to construct a program evaluation and review technique (PERT) distribution. ICE-Fos and ICE-Syn vehicles are assumed to have the same annual O&M cost. Supplementary Table 6 provides vehicle O&M costs.

SOG O&M costs are comprised of solar PV O&M costs (in US$ per kWp per year) and a combined inverter and stationary battery O&M cost (in US$ per kWh per year) sourced from ref. 6. SOG O&M costs are not differentiated by application or country, are static over time and probabilistically determined using mode values sourced from ref. 6 and are assumed ± 20% bound for the maximum and minimum values. Supplementary Table 4 provides SOG O&M (OPEX) costs.

Energy consumption values (in l/km and kWh/km) are sourced from the vehicle CAPEX database and thus averaged across a variety of vehicle brands and models within each application segment. As both the ICE and BEV technologies are projected to become more energy efficient in the future, we assume a 0.5% and 1.5% annual efficiency gain for ICE-Fos/Syn and BEV-SOG, respectively, congruent with similar projections for vehicle efficiency gains from BNEF63. In addition, we assume a wide probabilistic distribution (± 25% bound for the maximum and minimum values in the PERT distribution) to (1) account for uncertainty in future energy consumption values and (2) account for high variation in on-road conditions (that is, paved vs dirt roads), terrains (flat vs mountainous) and use cases (that is, urban vs rural). Supplementary Table 7 provides energy-consumption values.

Insurance costs are included as a percentage of the vehicle CAPEX for each technology. Calculation of insurance premiums in Africa vary across countries and depend upon a number of contributing factors such as initial value of the vehicle, resale value, risk profile of the purchasing individual, location of driving and vehicle use (distance travelled and type of use), among others. In South Africa and Nigeria average insurance premiums range between 1.5% and 5%, in Kenya between 3.5% and 7%, in Egypt and Morocco between 1% and 3%, in Ethiopia between 2% and 4% and in Rwanda and Ghana between 1% and 2%. To account for this variance, we assume a PERT distribution with a mode insurance premium cost of 2.4% of the vehicle CAPEX and a max/min insurance premium cost of 4% and 0.8%, respectively. To remain consistent with the approach of our analysis, these percentages include the removal of all taxes and fees typically included in insurance premiums such as value added tax (VAT) or other levies (assumed 20% of quoted premium). In a nascent but expanding market for BEVs in Africa, factors such as battery replacement costs, a limited resale market and restricted access to spare parts or qualified repair services have been shown to further elevate insurance premiums64,65,66. To account for these factors, we apply a percentage markup to the BEV insurance cost as compared to ICE vehicles. Specifically, we assume a 50% markup in 2025, 25% in 2030 and no markup by 2040, as we expect the BEV market to slowly stabilize, leading to equal insurance premiums across all vehicle technologies in the final model year. Supplementary Table 8 provides vehicle insurance costs.

Vehicle lifetime (in years) and annual kilometres travelled (AKT, in km per year) are differentiated only by application segment. We assume longer-than-global-average vehicle lifetimes to reflect the African use case based on refs. 39,67 but do not assume different lifetimes for the different vehicle technologies. Vehicle lifetime is defined as the full operational lifespan of the vehicle up to the point of scrappage—that is, when the vehicle becomes inoperable and is removed from service. This definition does not include extended second-hand use beyond typical functional life. We assume different average vehicle lifetimes by segment: 8 years for two-wheelers, 12 years for minibuses and 15 years for four-wheelers, each modelled using a wide PERT distribution around the mode. To assess the implications of longer-than-average use, we include a targeted analysis in Supplementary Note 2, exploring how extended lifetimes affect cost competitiveness between BEV-SOG and ICE-Fos technologies (Supplementary Fig. 33).

To calculate annual km travelled, we assume daily driving distances (in km per day) for each application segment, constant across technologies in the same segment and years. This gives application-specific values for annual km travelled on par with similar studies examining passenger vehicle TCO in Africa10,11,68. Supplementary Tables 9 and 10 provide vehicle lifetime and AKT values, respectively.

Definition of vehicle application segments

We define small two-wheelers as having up to 150 cubic centimeters (cc) power (for example, Honda Elite 125, Bajaj Chetak) and medium two-wheelers as having between 150 and 350 cc power (for example, Bajaj Boxer 150, Zeehoev AE8). For the four-wheeler segment, we follow the Euro Car Segment classification system: small four-wheelers encompass the A-segment mini cars and B-segment small cars (for example, Toyota Aygo, Renault Zoe); medium four-wheelers encompass the C-segment medium cars (for example, VW Golf, BYD Seal); large four-wheelers encompass the D-segment large cars and J-segment sport utility cars (for example, Toyota Hylander, Toyota BZ4k). For the minibus segment, we assume an 8–12-seat minibus for passenger travel (for example, Toyota Quantum, Geely V5e).

Vehicle CAPEX database and projections

For vehicle CAPEX, we gather extensive data on vehicle costs for internal combustion engine and battery electric vehicle technologies across all six application segments. Specifically, we collect manufacturer suggested retail prices for new battery electric vehicles between the years 2019–2024 from over 40 different manufacturers in seven regional automotive markets. Owing to Africa’s heavy reliance on vehicle imports, we source vehicle costs from automakers in regions currently exporting to the continent—such as the USA, Europe, Japan, Korea and India67—and regions expected to increase exports, primarily China39. In total, 151 combustion engine vehicle costs and 114 battery electric vehicle costs were collected across application segments. All costs are converted from listed currency in the selling region to a base currency (US$) using a ten-year average International Monetary Fund (IMF) conversion rate. Vehicle cost distributions (mean and standard deviation) are derived from the collected data for each application segment and used as input parameters to the TCO Monte Carlo analysis. Supplementary Table 3 provides vehicle CAPEX values.

Vehicle cost projections for BEVs are based on projected battery cost improvements from BNEF out to 2040, assuming a mid-scenario annual total battery demand as described in the section above. Building on the vehicle cost projection methodology from BNEF and other relevant models, we assume that BEV chassis and powertrain costs remain constant over time, as they are not expected to undergo meaningful cost reductions. Costs for ICE vehicles are assumed constant over time.

Cost of financing assumptions

For financing cost assumptions, we follow the methodology from Agutu et al.14, who quantify the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for different electrification modes for all sub-Saharan African countries, taking into consideration additional risk factors such as equity risk, small cap, illiquidity, sovereign risk and debt risk premiums that more accurately represent the risk profile for energy-related investments in sub-Saharan Africa. This is the most recent and comprehensive study to differentiate financing costs for African countries, and though it is applied to investments in electrification modes such as grid extensions, mini-grids and standalone off-grid systems, we argue that similar assumptions for financing costs of third-party owned automotive vehicles would apply though with a few adjustments made to specific risk parameters detailed in the following. The basic expression for the WACC is given in equation (5).

Where WACC is the weighted average cost of capital (in %), \({K}_{{\rm{e}},{\rm{i}}}\) and \({K}_{{\rm{d}},{\rm{i}}}\) are the cost of equity and cost of debt, respectively, for investments in a specific country \({\rm{c}}\). \(E\), \(D\) and \(V\) denote total equity, debt and capital and the debt share equals \(\frac{D}{V}\). Agutu et al.14 further define the cost of equity and cost of debt as in equation (6) and (7).

Where \({r}_{{\rm{f}}}\) is the risk-free rate based on the five-year US treasury bond yield in 2019 ( ~ 1.4%), \({\mathrm{CRp}}_{{\rm{c}}}\) represents the country-specific risk premium, \(\mathrm{Dp}\) the corporate bond premium, \({\mathrm{ERp}}_{{\rm{c}}}\) the equity risk premium, \(\mathrm{Ip}\) the equity risk premium and \(\mathrm{SCp}\) the small cap premium.

In the Agutu et al.14 study, three financing scenarios are defined illustrating possible financing options to reach 100% electrification in sub-Saharan Africa under different combinations of public vs private sector investment. This study applies the niche financing scenario to three vehicle technologies in the passenger sector with a small alteration to the cost of equity for BEVs. The small cap premium accounts for the higher-risk profiles of niche, off-grid companies with relatively small market capitalizations compared to larger firms. Similarly, we assume that retailers of BEVs may face a higher-risk premium, as BEVs remain a niche product with large uncertainty surrounding their adoption, infrastructure and availability. As such, BEVs exhibit a small cap premium of 3.8% (as assumed by the ‘niche financing scenario’ of Agutu et al.14) in 2025, though we reduce this premium to 1.9% in 2030 and remove the premium by 2040, by which time BEVs would probably be considered a mature technology. For ICE-Fos and ICE-Syn vehicles, we assume 0% small cap premium for all three model years, reflecting the market maturity of combustion engine vehicles. We assume a constant illiquidity premium of 3.6% for all three technologies in all countries over time and a constant country-specific equity risk premium over time. For the cost of debt, we assume a constant country-specific sovereign risk premium over time (that is no convergence) and a constant debt premium of 1.2% for all countries over time as in ref. 14. Finally, we assume a debt ratio of 50%.

For African countries not represented in the Agutu et al.14 study, we follow the same methodology presented by the authors to obtain all WACC parameters, collecting necessary financial data from NYU Stern and other established financial services companies and institutions such as Moody’s, Wikiratings and Fitch where relevant.

Supplementary Tables 11 and 12 for calculated WACC values for each vehicle technology in each country and model year. Note that financing cost parameters for the SOG follow the assumed parameter values for BEVs as described above.

Monte Carlo analysis

The Monte Carlo method is used to simulate uncertainty in the model through repeated simulation of outputs with probabilistic inputs that have defined stochastic distributions. The model runs 10,000 probabilistic TCO calculations for each vehicle technology in each application, country and model year (Supplementary Table 1 provides model dimensions). TCO parameters are either statically or dynamically determined over time (Supplementary Table 2). Note that we do not perform a Monte Carlo analysis for the SOG sizing optimization model (below) but do include uncertainty for the cost components of the SOG as part of the TCO calculation.

Levelized cost of charging and SOG sizing optimization model

To produce Fig. 3, we calculate the levelized cost of charging (LCOC)69 for the SOG system. The sizing of the SOG is based on a nonlinear optimization, based on the hourly solar irradiation in each location. The time-period T consists of all hours (t) in a year that is 1 − 8,760 hours. The total electric energy output of the PV panel EPV in a specific location is calculated as shown in equation (8). This value is calculated as the product of the local solar irradiation-specific yield SY (kWh per kWp), that is, the energy output of the solar PV system per unit of its installed peak capacity and the capacity of the PV panels CPV (kWp) and by accounting for the system loss R. The inverter’s capacity CInv limits the maximum amount of transferable power at any point in time t. The model is formulated on discrete timesteps t of duration Δt = 1 h. This means that PPV can only be maximum CInv.

The battery of the SOG allows it to store energy when EPV(t) is higher than the electricity demand Edemand(t) by the vehicles in that hour and vice-versa provides power when it is lower. We assume a conservative but realistic demand pattern based on ref. 70 where demand peaks around 18:00, reflecting EV owners plugging in their vehicles after returning home from work (Supplementary Fig. 32).

The energy flow towards the battery at every hour t is expressed in equation (9).

EBat (kWh) represents the energy flow towards the battery and can be either positive or negative as this storage device can either be charged or discharged at a certain point of time t. A cumulative variable CEBat(t) represents the current energy stored in the battery and operates as expressed in equation (10). If EPV is higher than Edemand(t), the difference between these two, that is, surplus energy flow towards the battery EBat (kWh), is added to the cumulative variable CEBat(t − 1), charging the battery as much as possible. Otherwise, CEBat(t) discharges to the extent necessary to meet the demand Edemand(t).

Both EBat(t) and CEBat(t) are subject to operational constraints. Neither can be less than zero, EBat(t) is further limited by the inverter capacity CInv, and the battery energy CEBat(t) is constrained by the battery capacity, CBat.

Another important parameter considered for the sizing of the SOG is the reliability r, which we define as one minus the proportion of unmet electric energy demand compared to the total demanded energy over the timeframe T assumed to be equivalent to one year. Hereby, Eunmet demand(t) is an important parameter representing the amount of demanded electric energy, which cannot be supplied by the SOG. Equations (11) and (12), with r that has to be higher than rmin, set to be 90%.

The optimization aims to minimize the absolute cost of the SOG system, solving for the capacity of the components, to satisfy constraints stated in equations (11) and (12). LCOC (US$2020 per kWh) of the SOG is calculated as seen in equation (13), where the denominator is the discounted sum of the energy supplied by the SOG during its lifetime to the specific vehicle segment.

For the optimization SciPy’s optimization algorithm COBYLA (constrained optimization by linear approximations) is used. \({i}_{{\rm{c}}}\) is the country-specific cost of capital (WACC). The outputs of the optimization are the LCOC and capacities of the components CPV, CBat and CInv.

Solar irradiation and geographical data

The dataset utilized in this study comprises a 1° × 1° grid covering the entire African continent, encompassing a total of 2,560 data points. Each point is assigned to a country based on its geographic location. Owing to the resolution of the grid, certain small or insular nations such as Cabo Verde, Comoros, Equatorial Guinea (one additional point to include Bioko), Mauritius, São Tomé & Príncipe, Seychelles and The Gambia lack any territorial representation. To address this limitation, representative data points for these countries were manually selected to ensure comprehensive coverage across all nations in Africa. Solar PV specific output data were obtained using the Python-based ‘pvlib’ API71, which leverages the Photovoltaic Geographic Information System of the European Union (PVGIS). The data, derived from the ERA-5 irradiation database72, were collected for the year 2019, assuming optimal conditions such as no horizon shading and a free mounting location. Calculations considered photovoltaic output per kWp installed capacity, with no tracking system and no system losses included in the initial model. The module orientation was set to optimal angles for both azimuth and slope to maximize energy capture. Missing data points from PVGIS, in large part regarding coordinates near the equator, were substituted with values obtained from renewables.ninja73,74, which relies on the MERRA-2 model and adheres to the same assumptions to ensure consistency.

Maximum financing cost optimization

The ‘maximum’ financing cost is the cost of capital value for the BEV-SOG technology in each model country, the four-wheeler small-application segment and model year 2030 for which the TCO break-even point between the two vehicle technologies, BEV-SOG and ICE-Fos, is met. To identify the ‘maximum’ financing cost as depicted in Fig. 5, we run a linear bisection optimization on the TCO Monte Carlo model for the four-wheeler small-application segment in all model countries in 2030 for the base parameter assumptions. The convergence criterion is such that the mean TCO for BEV-SOG is equal to the mean TCO for ICE-Fos in all 52 modelled countries. We assume a convergence tolerance of US$0.001 per km, with 1,000 Monte Carlo draws. The optimization converges within 10–11 iterations.

Technical implementation

The TCO Monte Carlo and SOG sizing optimization models are implemented in Python, using an Excel spread sheet as the main user interface for input data. The complete model is provided as supplementary material (Code availability statement). The maps representing TCO comparison per country (for example, Fig. 2) are created with the Cartopy package for Python and use open-source basemap data.

Life-cycle GHG emissions calculation

To incorporate a future-oriented perspective for life-cycle GHG emissions, we modified the life-cycle background system for the life-cycle assessment (LCA) using the Python-based tool premise (version 2.1.0)23. In this study, premise extends the ecoinvent v3.10 database (system model: ‘allocation, cut-off by classification’) and other datasets from its own library into future scenarios based on projections from the integrated assessment model REMIND. Specifically, two contrasting scenarios were selected to represent a range within potential transition pathways: SSP2–RCP 2.6 (Representative Concentration Pathway 2.6), which aims to limit global temperature rise to below 2 °C relative to pre-industrial levels, and SSP2–RCP 6, a no-policy-mitigation scenario that projects temperature increases above 3.5 °C. By applying these scenarios, we aim to capture a spectrum of carbon footprint outcomes based on global warming potential for a time horizon of 100 years (GWP100), encompassing both ambitious climate mitigation and minimal-policy pathways. Characterization factors of individual greenhouse gases represent global warming potentials for a time horizon of 100 years (‘GWP100‘). The characterization factors of emissions were based on radiative forcing according to Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2021, baseline model75 as implemented in the Environmental Footprint 3.1 method developed by the European Commission76.

The entire overview of life-cycle inventory datasets used in this analysis with respective sources are available in Supplementary Tables 13 and 14. A summary of key variables and parameters is provided here. The analysed SOG charging system comprises PV panels, a battery and an inverter, all assumed to be sourced from global markets. Datasets incorporate impacts from transportation to the consumer and losses during processing. For the system’s batteries, we used the global market dataset for lithium-ion battery cells with lithium iron phosphate cathodes and graphite-based anodes. Inventory data for battery production are primarily sourced from ref. 77.

Life-cycle inventories for the production of small, medium and large passenger cars are based on ref. 78, whereas inventories for the production of two-wheelers were sourced from ref. 79. The production of a minibus was approximated with that of a van retrieved from ref. 78. The life-cycle carbon footprint of synthetic fuels was based on production in Chile (assuming production in Sierra Gorda62) with electricity supply from open-ground photovoltaic. The dataset from synthetic fuel production—including proton exchange membrane electrolyses, low-temperature adsorption–direct air capture of CO2 and the Fischer–Tropsch synthesis process units—was obtained from ref. 80. The only change applied to the original dataset was the rescaling of the impact of open-ground PV electricity by a factor 0.78 retrieved from JRC Photovoltaic Geographical Information System81 to reflect the ratio of yearly electricity productions for tracking PV between Sierra Gorda and Tabernas (location assumed for the production of synthetic fuels in the original dataset). Furthermore, 81 kg CO2eq per tonne (ref. 62) were added for the transoceanic transport of synthetic fuels from Sierra Gorda to the African continent. The resulting carbon footprint of 1 metric t of synthetic fuels delivered to the African continent is 866–1,070 and 565–872 kg CO2eq, respectively, for 2030 and 2040, with the range reflecting stringent (RCP 2.6) or modest global climate policies (RCP 6). These values exclude the carbon uptake from the air. The carbon footprint of the fossil fuel including delivery to final consumer was assumed to be the one of global petrol from the ecoinvent database v3.10. The combustion emissions of gasoline were assumed to be 3.1 kg CO2eq per kg of fuel burned82.

Life-cycle GHG abatement costs calculation

The life-cycle GHG abatement cost (GHGAC, US$ per tCO2eq) is calculated as the difference between the TCO of the low-carbon transport option (EVs or ICEs with synthetic fuels) and the TCO of the fossil fuel option ICE-Fos divided by the difference between the life-cycle GHG emissions (LCE) of the fossil transport option and those of the low-carbon transport option, as shown in equation (14). Combustion-related CO2 emissions of synthetic fuels are neglected as the same amount of CO2 has been extracted from the atmosphere via DAC for synfuel production.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data input files for the analysis are available in the article and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code needed to run the analysis is publicly available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15132262 (ref. 83). The Cartopy package for Python, used to create the maps of results in Figs. 2 and 3 and figures in the Supplementary Information, is publicly available for download from https://scitools.org.uk/cartopy and references the Natural Earth data. Free vector and raster map data are available at naturalearthdata.com.

References

Jaramillo, P. et al. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2023).

International Council on Clean Transport. Vision 2050: A Strategy to Decarbonize the Global Transport Sector by Mid-Century (2020).

Axsen, J., Plötz, P. & Wolinetz, M. Crafting strong, integrated policy mixes for deep CO2 mitigation in road transport. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 809–818 (2020).

International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2024 (2024).

Meza, E. Future Volkswagen boss renews backing for controversial synthetic fuels. Clean Energy Wire https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/future-volkswagen-boss-renews-backing-controversial-synthetic-fuels (2022).

Davenport, C. E.P.A. allows California to ban sales of new gas-powered cars by 2035. New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/18/climate/california-ban-new-gasoline-powered-cars.html (2024).

Liboreiro, J. In win for Germany, EU agrees to exempt e-fuels from 2035 ban on new sales of combustion-engine cars. Euronews https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/03/28/in-win-for-germany-eu-agrees-to-exempt-e-fuels-from-2035-ban-on-new-sales-of-combustion-en (2023).

Ayetor, G. K., Opoku, R., Sekyere, C. K. K., Agyei-Agyeman, A. & Deyegbe, G. R. The cost of a transition to electric vehicles in Africa: a case study of Ghana. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 10, 388–395 (2022).

Dixon, J. et al. How can emerging economies meet development and climate goals in the transport-energy system? Modelling co-developed scenarios in Kenya using a socio-technical approach. Energy Strat. Rev. 53, 101396 (2024).

Ayetor, G. K., Quansah, D. A. & Adjei, E. A. Towards zero vehicle emissions in Africa: a case study of Ghana. Energy Policy 143, 111606 (2020).

Dioha, M. O., Duan, L., Ruggles, T. H., Bellocchi, S. & Caldeira, K. Exploring the role of electric vehicles in Africa’s energy transition: a Nigerian case study. iScience 25, 103926 (2022).

Gammon, R. & Sallah, M. Preliminary findings from a pilot study of electric vehicle recharging from a stand-alone solar minigrid. Front. Energy Res. 8, 563498 (2021).

Mulugetta, Y. et al. Africa needs context-relevant evidence to shape its clean energy future. Nat. Energy 7, 1015–1022 (2022).

Agutu, C., Egli, F., Williams, N. J., Schmidt, T. S. & Steffen, B. Accounting for finance in electrification models for sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Energy 7, 631–641 (2022).

Ameli, N. et al. Higher cost of finance exacerbates a climate investment trap in developing economies. Nat. Commun. 12, 4046 (2021).

Lonergan, K. E. et al. Improving the representation of cost of capital in energy system models. Joule 7, 469–483 (2023).

Mutiso, R. M. Mapping Africa’s EV revolution. Science 385, eadr1055 (2024).

Johansson, D. & Mutiso, R. Africa’s vehicle fleet could double by 2050: what does this mean for EVs? Energy For Growth Hub https://energyforgrowth.org/article/africas-vehicle-fleet-could-double-by-2050-what-does-this-mean-for-evs/ (2025).

Off-grid electrification of mobility in Africa. Zero Carbon Charge https://charge.co.za (2025).

First off-grid electric vehicle charging station launches in South Africa. BusinessTech https://businesstech.co.za/news/motoring/801941/first-off-grid-electric-vehicle-charging-station-launches-in-south-africa (2024).

Plötz, P. Hydrogen technology is unlikely to play a major role in sustainable road transport. Nat. Electron. 5, 8–10 (2022).

Nigeria: powering electric mobility - developer guide. GET.Invest https://www.get-invest.eu/resources/market-insights/#nigeria (2024).

Sacchi, R. et al. PRospective EnvironMental Impact asSEment (premise): a streamlined approach to producing databases for prospective life cycle assessment using integrated assessment models. Renewable Sustain. Energy Rev. 160, 112311 (2022).

Baumstark, L. et al. REMIND2.1: transformation and innovation dynamics of the energy-economic system within climate and sustainability limits. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 6571–6603 (2021).

Greenpeace International. Energy Revolution. A Sustainable World Energy Outlook (2012).

International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2023: Catching up with Climate Ambitions (2023).

Bieker, G. A Global Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustion Engine and Electric Passenger Cars (International Council on Clean Transportation, 2021).

Africa EV readiness and impact index. Energy for Growth Hub https://energyforgrowth.org/article/africa-ev-readiness-and-impact-index-2024-desktop (2024).

Nsan, N., Obi, C. & Etuk, E. Bridging policy, infrastructure, and innovation: a causal and predictive analysis of electric vehicle Iitegration across Africa, China, and the EU. Sustainability 17, 5449 (2025).

Ajao, Q., Prio, M. H. & Sadeeq, L. Analysis of factors influencing electric vehicle adoption in sub-Saharan Africa using a modified UTAUT framework. Discover Electron. 2, 4 (2025).

Pappis, I. Strategic low-cost energy investment opportunities and challenges towards achieving universal electricity access (SDG7) in forty-eight African nations. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2, 035005 (2022).

World Bank Group. Trust, priority areas, and climate concerns - context data. https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/world-bank-country-opinion-surveys/context-data (2024).

Ramachandran, V. & Nordhaus, T. Trump is quitting the Paris Agreement. Poor countries should, too. Foreign Policy https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/01/06/trump-paris-agreement-climate-cop-global-south-africa-poor-countries (2025).

uYilo eMobility Programme - enabling Electric Mobility in South Africa. uYilo https://www.uyilo.org.za (2025).

Hao, H. et al. Impact of transport electrification on critical metal sustainability with a focus on the heavy-duty segment. Nat. Commun. 10, 5398 (2019).

Busch, P., Chen, Y., Ogbonna, P. & Kendall, A. Effects of demand and recycling on the when and where of lithium extraction. Nat. Sustain. 8, 773–783 (2025).

Zeng, A. et al. Battery technology and recycling alone will not save the electric mobility transition from future cobalt shortages. Nat. Commun. 13, 1341 (2022).

Bieker, E. L., Bieker, G. & Sen, A. Electrifying road transport with less mining: a global and regional battery material outlook. International Council on Clean Transportation https://theicct.org/publication/ev-battery-materials-demand-supply-dec24 (2024).

International Transport Forum. New but Used: The Electric Vehicle Transition and the Global Second-hand Car Trade (2023).

Ayetor, G. K., Mbonigaba, I., Sackey, M. N. & Andoh, P. Y. Vehicle regulations in Africa: impact on used vehicle import and new vehicle sales. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 10, 100384 (2021).

Hodgson, C. & Dempsey, H. UK faces mounting stockpile of used EV batteries. Financial Times https://www.ft.com/content/cc5ef169-fac1-4af0-9b99-1edd360325e4 (2025).

Li, P. et al. Can Chinese electric vehicles meet EU batteries regulation targets? A dynamic approach to assess the potential for recycled materials use in Chinese EV batteries. World Electr. Veh. J. 16, 342 (2025).

Wu, G., Inderbitzin, A. & Bening, C. Total cost of ownership of electric vehicles compared to conventional vehicles: a probabilistic analysis and projection across market segments. Energy Policy 80, 196–214 (2015).

Palmer, K., Tate, J. E., Wadud, Z. & Nellthorp, J. Total cost of ownership and market share for hybrid and electric vehicles in the UK, US and Japan. Appl. Energy 209, 108–119 (2018).

Noll, B., Val, S. del, Schmidt, T. S. & Steffen, B. Analyzing the competitiveness of low-carbon drive-technologies in road-freight: a total cost of ownership analysis in Europe. Appl. Energy 306, 118079 (2022).

Noll, B., Schmidt, T. S. & Egli, F. Managing trade-offs between electric vehicle taxation and adoption. Cell Rep. Sustain. 1, 100130 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Comparing total cost of ownership of battery electric vehicles and internal combustion engine vehicles. Energy Policy 158, 112564 (2021).

Nguyen-Tien, V., Zhang, C., Strobl, E. & Elliott, R. J. R. The closing longevity gap between battery electric vehicles and internal combustion vehicles in Great Britain. Nat. Energy 10, 354–364 (2025).

Danish Energy Agency. Technology Data: Energy Plants for Electricity and District Heating Generation; https://ens.dk/en/analyses-and-statistics/technology-data-generation-electricity-and-district-heating (2025).

Electric vehicle outlook (EVO) 2023. BloombergNEF https://about.bnef.com/electric-vehicle-outlook (2023).

Beuse, M., Steffen, B. & Schmidt, T. S. Projecting the competition between energy-storage technologies in the electricity sector. Joule 4, 2162–2184 (2020).

Urgent deployment of existing technology can get world close to net aero, BloombergNEF’s new energy outlook 2024 shows. BloombergNEF https://about.bnef.com/blog/urgent-deployment-of-existing-technology-can-get-world-close-to-net-zero-bloombergnefs-new-energy-outlook-2024-shows (2024).

Getting on track for net-zero by 2050 will require rapid scaling of investment in the energy transition over the next ten years. BloombergNEF https://about.bnef.com/blog/getting-on-track-for-net-zero-by-2050-will-require-rapid-scaling-of-investment-in-the-energy-transition-over-the-next-ten-years (2021).

Sanders, M. The Rechargeable Battery Market and Main Trends 2016–2025 (Avicenne Energy, 2017).

European lithium-ion battery supply will come up short despite investment boom. Best Magazine https://www.bestmag.co.uk/european-lithium-ion-battery-supply-will-come-up-short-despite-investment-boom (2024).

Ramasamy, V. et al. U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System and Energy Storage Cost Benchmarks, With Minimum Sustainable Price Analysis: Q1 2023 (NREL, 2023).

How much do off-grid solar systems cost. Shielden https://www.shieldenchannel.com/blogs/solar-panels/off-grid-solar-system-cost (2025).

Kamoji, J. Off-grid solar EV charging system designed for quick installation. PV Magazine https://pv-magazine-usa.com/2024/02/06/off-grid-solar-ev-charging-system-designed-for-quick-installation (2024).

Vehicle Total Cost of Ownership Model (TCOM 1.1.0) (BloombergNEF, 2022).

Ross, M. L., Hazlett, C. & Mahdavi, P. Global progress and backsliding on gasoline taxes and subsidies. Nat. Energy 2, 16201 (2017).

US Energy Information Administration. Petroleum & other liquids; https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=pet&s=eer_epmru_pf4_y35ny_dpg&f=a (2025).

Allgoewer, L. et al. Cost-effective locations for producing fuels and chemicals from carbon dioxide and low-carbon hydrogen in the future. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 63, 13660–13676 (2024).

Long-term electric vehicle outlook 2024. BloombergNEF https://www.bnef.com/flagships/ev-outlook (2024).

Nurse, S. What is the cost of insurance for electric cars in South Africa? AutoTrader https://www.autotrader.co.za/cars/news-and-advice/electric-cars/what-is-the-cost-of-insurance-for-electric-cars-in-south-africa/13985 (2024).

A quick guide to insuring your electric vehicle in South Africa. Naked Blog https://www.naked.insure/blog/a-quick-guide-to-insuring-your-electric-vehicle-in-south-africa (2024).

How much does comprehensive car insurance cost in Nigeria? Guardian Nigeria https://guardian.ng/business-services/insurance/how-much-does-comprehensive-car-insurance-cost-in-nigeria/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (2025).

UN Environment Programme. Used Vehicles and the Environment: A Global Overview of Used Light Duty Vehicles: Flow, Scale and Regulation (2020).

Lukuyu, J., Shirley, R. & Taneja, J. Managing grid impacts from increased electric vehicle adoption in African cities. Sci Rep. 14, 24320 (2024).

Lanz, L., Noll, B., Schmidt, T. S. & Steffen, B. Comparing the levelized cost of electric vehicle charging options in Europe. Nat. Commun. 13, 5277 (2022).

Briceno-Garmendia, C., Qiao, W. & Foster, V. The Economics of Electric Vehicles for Passenger Transport (World Bank Group, 2023).

Anderson, K. S. et al. pvlib python: 2023 project update. J. Open Source Software 8, 5994 (2023).

Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (2023).

Pfenninger, S. & Staffell, I. Long-term patterns of European PV output using 30 years of validated hourly reanalysis and satellite data. Energy 114, 1251–1265 (2016).

Staffell, I. & Pfenninger, S. Using bias-corrected reanalysis to simulate current and future wind power output. Energy 114, 1224–1239 (2016).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Bassi, S. A. et al. Updated Characterisation and Normalisation Factors for the Environmental Footprint 3.1 Method (Publications Office of the European Union, 2023).

Dai, Q., Kelly, J. C., Dunn, J. & Benavides, P. T. Update of Bill-of-Materials and Cathode Materials Production for Lithium-Ion Batteries in the GREET Model (2018).

Sacchi, R., Bauer, C., Cox, B. & Mutel, C. When, where and how can the electrification of passenger cars reduce greenhouse gas emissions?. Renewable Sustain. Energy Rev. 162, 112475 (2022).

Sacchi, R. & Bauer, C. Life cycle inventories for on-road vehicles. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7788737 (2021).

Ingwersen, A. et al. Prospective life cycle assessment of cost-effective pathways for achieving the FuelEU maritime regulation targets. Sci. Total Environ. 958, 177880 (2025).

European Commission. Performance of Grid-Connected PV. Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (2024).

Moretti, C., Moro, A., Edwards, R., Rocco, M. V. & Colombo, E. Analysis of standard and innovative methods for allocating upstream and refinery GHG emissions to oil products. Appl. Energy 206, 372–381 (2017).

Noll, B., Graff, D. & Moretti, C. Supplementary code: battery-electric passenger vehicles to become cost-effective across Africa well before 2040. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15132262 (2025).

Acknowledgements

B.N., D.G., T.S.S., A.P., C.B., P.K.A, I.N., T.T. and C.M. acknowledge funding from the ETH Mobility Initiative via the ESYN project (grant 2023-HS-110 MI-05-23). We would like to thank the industrial partner AMAG and Dino Graf (AMAG) in particular. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the SPEED2ZERO initiative (T.S.S., A.P., C.B., T.T., C.M.), which received support from the ETH-Board under the Joint Initiatives scheme.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.N., D.G., T.S.S, A.P., C.B., T.T. and C.M. conceptualized the research and designed the methodology; B.N., D.G., P.K.A., I.N. and C.M. coordinated the data research; B.N., T.S.S., A.P., C.B. and C.M. contributed to funding acquisition; B.N., D.G. and C.M. conducted the formal analysis and programmed the computer software; B.N. visualized the data presentation; B.N., D.G. and C.M. wrote the original draft; all authors contributed to the final draft including review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.