Abstract

Despite ongoing antibiotic development, evolution of resistance may render candidate antibiotics ineffective. Here we studied in vitro emergence of resistance to 13 antibiotics introduced after 2017 or currently in development, compared with in-use antibiotics. Laboratory evolution showed that clinically relevant resistance arises within 60 days of antibiotic exposure in Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, priority Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens. Resistance mutations are already present in natural populations of pathogens, indicating that resistance in nature can emerge through selection of pre-existing bacterial variants. Functional metagenomics showed that mobile resistance genes to antibiotic candidates are prevalent in clinical bacterial isolates, soil and human gut microbiomes. Overall, antibiotic candidates show similar susceptibility to resistance development as antibiotics currently in use, and the corresponding resistance mechanisms overlap. However, certain combinations of antibiotics and bacterial strains were less prone to developing resistance, revealing potential narrow-spectrum antibacterial therapies that could remain effective. Finally, we develop criteria to guide efforts in developing effective antibiotic candidates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections are a major public health concern and are responsible for a substantial proportion of morbidity and mortality worldwide1. Paradoxically, many pharmaceutical companies have discontinued their antibiotic research programs2. This may be linked to the rapid spread of MDR bacteria, which makes the commercial success of new antimicrobial drugs unpredictable3,4. For example, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) spent US$15 million to acquire the GSK2251052 molecule and invested further money in its development; however, resistance to GSK2251052 emerged and the project was cancelled5. Antibiotics released to the market can also lose utility and revenue in only a few years due to resistance. Dalbavancin is one of the few therapies available for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections6,7 but resistance emerged after 2 years of commercialization.

Bacteria acquire resistance through diverse genetic mechanisms, including point mutations, amplification of genomic segments and horizontal transfer of resistance genes8. The ability to predict the possible evolutionary routes towards resistance is clearly needed, especially at an early stage of antibacterial drug discovery, to develop antibiotics with limited susceptibility to resistance. However, this is a complex problem for three main reasons: (1) multiple and varied molecular mechanisms contribute to antimicrobial resistance, (2) numerous pathogenic bacteria need to be considered and (3) many potential antibacterial compounds need to be tested.

Here we asked whether antibiotic candidates show differences in their susceptibility to the development of resistance compared with antibiotics that are currently in use. By combining laboratory evolution and functional metagenomics, we studied in vitro emergence of resistance to antibiotics either introduced after 2017 or currently in development, compared with antibiotics that are currently in use.

On the basis of the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) pipeline report9 and reviews on the subject10,11,12, we selected antimicrobial compounds that have been introduced into clinical practice recently (after 2017) or that are currently in development (that is, recent antibiotics; Table 1). The selected compounds are generally small molecules and directly target Gram-negative bacteria. Most of the candidate antibiotics analysed are intended to be used as monotherapies, mostly via intravenous or oral administration; however, previous knowledge on de novo emergence of resistance is limited (Supplementary Table 2). We considered lead compounds that are in clinical trials or have at least established efficacy against Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens, including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mouse infection models. These antibiotics include multitargeting compounds that are considered to be less prone to resistance13,14. Similarly, compounds that attack essential components of the outer cell membrane have previously been suggested to be immune to bacterial resistance10,15 because potential resistance mutations to these drugs would seriously compromise normal cellular functioning. As the evolutionary dynamics of resistance to antibiotic combinations can be very different from that of monotherapies, we examine recent advances in adjuvant therapies (for example, β-lactamase inhibitors) in a separate study. For more information on antibiotic choices, see Supplementary Note 1.

Our main goal was to compare the resistance profiles of these ‘recent’ antibiotics with antibiotics established for clinical use (that is, control). The control antibiotics belong to distinct major classes of antibiotics and they have all been in clinical use for over 25 years (Supplementary Table 3). To systematically characterize the bacterial capacity for resistance and the molecular mechanisms conferring resistance, we combined laboratory evolution, functional metagenomic screens and targeted mutagenesis. To explore the potential clinical relevance of our findings, we examined whether the identified resistance mutations and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) can be found in natural bacterial isolates and in human-associated microbiomes (Extended Data Fig. 1).

We found that critical Gram-negative pathogens develop resistance within a short time frame after antibiotic exposure in vitro. The mutations driving this resistance, found in laboratory-evolved strains, are already present in natural pathogen populations, suggesting that resistance can rapidly emerge through the selection of pre-existing variants. In addition, we identified mobile resistance genes to antibiotic candidates across clinical isolates and in environmental and human microbiomes.

Results

Resistance to in-use and in-development antibiotics overlaps

We selected 40 representative strains from 4 Gram-negative bacterial pathogens, including Escherichia coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa (Supplementary Table 4), and measured their in vitro susceptibilities to 22 clinically in-use antibiotics (control) and 13 antibiotics that are in development or were introduced post-2017 (recent; Supplementary Table 3). Of the 40 strains with clinical origins, 8 were confirmed to be extensively drug resistant (XDR) because the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for nearly all clinically recommended antibiotics were above the established clinical breakpoints (Extended Data Fig. 2). For these 40 strains, recent antibiotic candidates, such as cefiderocol, SPR-206, eravacycline and delafloxacin, have on average significantly higher efficacy (that is, a lower average MIC) compared with control antibiotics with similar modes of action (Fig. 1a). Indeed, hierarchical clustering based on the heat map of antibiotic susceptibility profiles showed that control and recent antibiotics with related modes of action cluster together (Fig. 1b). Moreover, MDR and XDR bacterial strains generally showed reduced sensitivity to both control and recent antibiotics compared with antibiotic-sensitive (SEN) strains belonging to the same species (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Together, these results indicate an overlap in resistance profiles for antibiotics that have been in clinical use and antibiotic candidates in development. However, certain membrane-targeting antibiotics, such as POL-7306 and SPR-206, were as effective in targeting MDR and XDR strains as they were in targeting SEN strains (Extended Data Fig. 3b), highlighting their antibacterial potential.

a, Comparison of MIC for control and recent antibiotics. The figure shows the median MIC values (on a log10 scale) of control and recent antibiotics across all tested bacterial strains. Each plot represents a specific recent antibiotic, along with the corresponding control antibiotics belonging to the same class (indicated and colour coded at the top of each plot). Individual points depict median MIC values of strain–antibiotic pairs, with lines connecting paired data points representing MIC values of the specific recent and within-class control antibiotic for the same strain. Blue points and lines indicate cases where the MIC of a recent antibiotic is lower compared with the corresponding control antibiotics for the same strain, whereas red indicates cases in which the MIC is not lower. Median MIC values are based on two biological and three technical replicates for each bacterial strain–antibiotic combination. Box plots show the median, first and third quartiles, with whiskers indicating the 5th and 95th percentiles of the median MIC values per investigated group. Paired Wilcoxon rank-sum analysis (two-sided test) was performed to assess significant difference between control and recent antibiotics within each class. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. For antibiotic abbreviations, see Table 1. The antibiotic classes are as follows: aminoglycosides (AMIN), carbapenems (CARB), cephalosporins (CEPH), membrane-targeting antibiotics (MEMB), topoisomerase inhibitors (TOPO) and tetracyclines (TETR). b, Recent antibiotics cluster together with control antibiotics based on sensitivity testing of a panel of bacterial strains. The heat map shows the antibiotic susceptibility profiles of bacterial strains (columns) belonging to four bacterial species, including E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa. In the x-axis labels, the first two letters represent the species (AB, A. baumannii; EC, E. coli; KP, K. pneumoniae; PA, P. aeruginosa), the next three letters indicate strain categorization based on susceptibility profiling (see Methods), while the final numbers serve as unique identifiers (please note that only strains without numeric identifiers were used for further experiments). The bacterial strains are ordered by the fraction of control antibiotics (red gradient panel on the top) to which they are resistant, as defined by the corresponding species-specific clinical breakpoint values. For more details on the abbreviations, see Table 1 (for antibiotics) and Supplementary Table 4 (species and strains). The antibiotic panel consists of 22 control (blue) and 13 recent (orange) antibiotics (rows). Antibiotic generations and classes are indicated on the left. Antibiotic clustering was based on calculating Spearman’s rank correlation of median MIC values and using the complete hierarchical clustering method. The bacterial strains are ordered by the fraction of control antibiotics (top) to which they are resistant (defined by the corresponding species-specific clinical breakpoint values). Median MIC values are based on two biological and three technical replicates for each bacterial strain–antibiotic combination. AMI, amikacin; AMP, ampicillin; APR, apramycin-sulphate; CEP, cefepime; CID, cefiderocol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; COL, colistin; CTO, ceftobiprole; CTZ, ceftazidime; CZA, ceftazidime-avibactam; DEL, delafloxacin; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor; DOR, doripenem; DOX, doxycycline; ERA, eravacycline; GEN, gentamicin; GEP, gepotidacin; IMI, imipenem; I-R, imipenem-relebactam; LEV, levofloxacin; MER, meropenem; MOX, moxifloxacin; NS, not significant; OMA, omadacycline; PIP, piperacillin; PMB, polymyxin B; POL, POL-7306; SCH, SCH-79797; SPR, SPR-206; SUO, sulopenem; TIC, ticarcillin; TIG, tigecycline; TOB, tobramycin; TRD, tridecaptin M152-P3; TRM, trimethoprim; TRS, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; ZOL, zoliflodacin.

Species-specific evolution of resistance in the laboratory

Next, we asked whether antibiotic resistance evolves in bacterial pathogens, rendering the two groups of antibiotics less effective in the long term. Here we selected one MDR and one SEN strain each of E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa (Supplementary Table 4). Of all antibiotic–strain combinations, 32% were excluded from the analysis due to relatively low initial antibiotic susceptibility (that is, MIC > 4 µg ml−1).

To characterize first-step resistance, we used a standard protocol for spontaneous frequency-of-resistance (FoR) analysis16,17,18,19 at multiple concentrations of each antibiotic. Approximately 1010 bacterial cells were exposed to each antibiotic on agar plates for 2 days at concentrations to which the given strain is susceptible. Mutants with decreased antibiotic sensitivity, that is, with at least a 4-fold increase in MIC fold change, were detected in 49.8% of the populations. Although clinical breakpoints are unknown for most of the recent antibiotics studied, recommended dosing for intravenous use is available in all cases. Therefore, data on the highest available peak plasma concentrations of the drugs (measured at intravenous administration) were used as a proxy to estimate potential clinical relevance of the MIC changes in the evolved strains (Supplementary Table 3). Within the short 48 h time frame, MICs were either equal to or above the peak plasma concentration in up to 18.7% of the mutant lines (Extended Data Fig. 4a). For 30% of the FoR-adapted lines, MICs surpassed the clinical breakpoint at which such data were available (Extended Data Fig. 4b). On average, recent and control antibiotics were equally prone to bacterial resistance because neither the frequency of appearance per generation of mutants (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0.9; Extended Data Fig. 4c) nor the fold change in resistance were statistically different (paired t-test, P = 0.68).

As FoR assays cannot detect very rare mutations either alone or in combination20 and can underestimate bacterial potential for resistance, we used the same eight ancestral strains (Supplementary Table 4) to initiate adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) with two goals. First, we aimed to maximize the level of antibiotic resistance in the populations achieved during a longer, fixed time period (for up to ∼120 generations; Methods). Second, we aimed to characterize the mechanisms associated with resistance. Ten parallel-evolving populations of each strain were exposed to increasing concentrations each of the recent or control antibiotics. The level of resistance was estimated by comparing MICs of the evolved lines with those of their corresponding ancestral strains (Fig. 2a).

a, Changes in MICs after ALE. Each point represents the median MIC values of a laboratory-evolved line and the corresponding ancestor (log10 scale). Median MIC values are based on two biological and three technical replicates for each bacterial strain–antibiotic combination. Control and recent antibiotics are indicated by blue and orange plots, respectively. Each group of plots represents a specific antibiotic class (indicated at the top of each plot). The colour of the data points represents the bacterial species. The black dashed line indicates y = x (that is, no changes in MIC during the course of laboratory evolution), whereas the red dashed line shows the antibiotic-specific peak plasma concentration. For abbreviations, see Table 1. Due to low stability in the liquid laboratory medium used, cephalosporin antibiotics were not subjected to ALE. b, Relative MIC of laboratory-evolved lines across all antibiotic–ancestor strain combinations. In the x-axis labels, the first two letters represent the species, the next three letters represent the strain and the last three letters represent the antibiotics. For more details on the abbreviations, see Table 1 (for antibiotics) and Supplementary Table 4 (species and strains). Relative MIC is the median MIC of the evolved line divided by the median MIC of the corresponding ancestor. Each point is a laboratory-evolved line from ALE and the colours indicate the bacterial species. Each point is the median MIC value of a strain–antibiotic pair. Median MIC values are based on two biological and three technical replicates for each bacterial strain–antibiotic combination. Box plots show the median, first and third quartiles, with whiskers indicating the 5th and 95th percentiles of the MIC values per investigated group. There is a highly significant heterogeneity in relative MIC across antibiotic–strain combinations (Kruskal–Wallis χ2 = 630.43, d.f. = 80, P < 2.2 × 10−16).

In general, 120 generations (60 days) of laboratory evolution was sufficient for the bacterial strains to develop resistance; the median antibiotic-resistance level in the evolved lines was ~64 times higher compared with that of the ancestor. MICs were either equal to or above the peak plasma concentration in 87% of all studied populations. Moreover, MICs surpassed the clinical breakpoint, where such data were available, for 88.3% of the ALE-adapted lines (Extended Data Fig. 4b). On average, recent and control antibiotics were equally prone to bacterial resistance (paired t-test, one-sided, P = 0.37). Resistance also emerged to recent antibiotics (Fig. 2a), with potent antibacterial activities targeting the MDR and XDR clinical isolates tested (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

Given the large heterogeneity observed in the capacity to evolve resistance across antibiotic–strain combinations, spanning a 65,000-fold range between the observed minimum and maximum MIC fold changes (Fig. 2b), we investigated possible reasons for this variation. We first analysed whether initial antibiotic susceptibility predicts long-term drug efficacy against bacteria. We found a significant positive correlation between initial MIC and the increase in resistance level across antibiotics in ALE-derived lines in two of the four species (Extended Data Fig. 5a) and five of the eight bacterial strains studied (Extended Data Fig. 5b). We also analysed whether initial MIC correlates with the increase in resistance level across strains when each antibiotic is analysed separately. We found a significant positive trend in 5 of the 16 antibiotics (Extended Data Fig. 5c). These results show that initial MIC is predictive of long-term efficacy of an antibiotic in a strain- and antibiotic-specific manner.

Previous work21,22 indicates that certain antibiotics are more susceptible to resistance evolution for particular bacterial strains and species compared with others. Accordingly, we used multiple linear regression to investigate the global influence of both antibiotic and strain genetic background on the increase in resistance level, while also considering the resistance level of the ancestor (Extended Data Fig. 5d). When examining these factors separately, the antibiotic and strain genetic background explained 24.4% and 8.9%, respectively, of the variation in the increase of resistance levels, with the initial antibiotic susceptibility level (MIC) contributing 0.9% to the variance. In an additive model, combining the antibiotic, the initial MIC and genetic background explained approximately 33% of the variation. Importantly, a model that allows an interaction term between genetic background and antibiotic combination explains an additional ~26% of variation in the increase of resistance compared with the simple additive model (that is, 58.6% versus 32.6%; Extended Data Fig. 5d).

Together, these results indicate that the initial genetic makeup of the bacterial population has a large impact on resistance evolution, but predominantly in an antibiotic-specific manner. Detailed analysis of two antibiotic candidates, SCH-79797 and SPR-206, highlight this point further (Supplementary Note 2).

Overlap in mutational profiles across antibiotic treatments

To identify mutations underlying resistance, resistant lines derived from laboratory evolution (n = 381) and FoR assays (n = 135) were subjected to whole-genome sequencing (Supplementary Data 1). We implemented an established computational pipeline to identify mutations relative to the corresponding ancestral genomes. Ten evolved lines accumulated exceptionally large numbers of mutations (n > 18), many of which are probably functionally irrelevant. These lines have elevated genomic mutation rates; indeed six of the ten lines have mutations in methyl-directed mismatch repair (mutS, mutL or mutY). Such mutator bacteria frequently arise in response to antibiotic stress in clinical and laboratory settings23. For the remaining 506 lines, we identified 1,817 unique mutational events, including 1,212 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 605 insertions or deletions (Extended Data Fig. 6a). We found a significant excess of non-synonymous over synonymous mutations, indicating that the accumulation of the SNPs in protein-coding regions was largely driven by selection towards increased resistance (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Of the observed mutations, 19.7% generated in-frame stop codons, frameshifts or disruption of the start codon, which are probably loss-of-function mutations (Extended Data Fig. 6c). This result is consistent with previous studies on the role of inactivating mutations in antibiotic resistance24.

In total, 604 mutated protein-coding genes were detected, 193 of which were mutated in at least 2 independently evolved lines per species. Of all parallel-mutated genes, 69.4% carried mutations in lines adapted to different antibiotics. These results indicate that despite differences in antibiotic treatments, there is considerable overlap in the set of mutated genes (Fig. 3a,b). Further results indicate that adaptation during the course of laboratory evolution in the presence of antibiotics was largely unrelated to the growth medium (Supplementary Note 3).

a, Repeatedly mutated genes during laboratory evolution across different antibiotics. The heat map shows commonly mutated genes (and the corresponding orthogroups) across the tested antibiotics after ALE. Genes were considered commonly mutated if they accumulated non-synonymous mutations in response to at least three different antibiotic treatments. Left: the class and the generation of the given antibiotics. The top two rows correspond to the number of antibiotic classes and the number of antibiotics in which a given orthogroup is mutated. b, Mutation profile similarity across antibiotics. Each node represents a recent (orange) or control (blue) antibiotic. Links indicate an overlap in the set of mutated genes (or corresponding orthogroups) detected after ALE. Only non-synonymous mutations in protein-coding genes were considered. The thickness of the links indicates the extent of overlap (calculated by Jaccard similarity, as in previous work96) between antibiotic treatments. c, Non-synonymous mutations shared by laboratory-evolved lines and natural isolates of E. coli and A. baumannii. The bar plots show the number of non-synonymous mutations found in laboratory-evolved A. baumannii (left) or E. coli (right) adapted to different antibiotics. Mutations also detected in the genomes of natural isolates of the same species are marked in red, whereas those that remained undetected are marked in grey. No significant difference was found in the fraction of non-synonymous mutations shared by natural strains between control and recent antibiotics (binomial regression model, two-sided test, P = 0.206). For abbreviations, see Table 1.

To explore cross-resistance explicitly, we focused on topoisomerase inhibitors because this drug class includes a substantial proportion of the antibiotics currently in clinical trials, and resistance is usually encoded by resistance mutations. We performed deep-scanning mutagenesis in genes encoding the targets of moxifloxacin (gyrA and parC). Moxifloxacin resistance-conferring mutation combinations reduced susceptibility to topoisomerase inhibitors under clinical development, including delafloxacin and gepotidacin (Supplementary Note 4). The result with gepotidacin is unexpected because it is a new topoisomerase inhibitor in development, featuring innovative target sites and modes of action25. Previous studies reported that fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates showed no cross-resistance to this antibiotic but the data were limited26.

Mutations to recent antibiotics are present in the environment

Given the overlap observed in mutational targets associated with resistance to antibiotics in clinical use and antibiotics in development (Fig. 3a,b), we hypothesized that mutations arising during laboratory evolution may already be present in environmental and clinical bacterial isolates. To investigate this hypothesis, we analysed the prevalence of the observed mutations from laboratory-evolved E. coli and A. baumannii lines in a publicly available catalogue of genomes derived from natural isolates of E. coli (n = 20,786) and A. baumannii (n = 15,185) (Fig. 3c). We focused on non-synonymous mutations in protein-coding sequences and estimated their frequencies in the genomes of environmental isolates in these two species. For E. coli, up to 31.4% of the 245 laboratory-observed non-synonymous mutations were identified in at least 1 of the genomes from natural isolates, whereas for A. baumannii, 27.3% of 216 mutations were found in at least 1 natural isolate. Although the majority of mutations found in E. coli were relatively rare (that is, typically found in less than 1% of the isolates), they were more enriched among pathogenic isolates than in other natural isolates (Fisher’s test, P < 2.2 × 10−16, odds ratio = 3.16). Several adaptive mutations were as abundant as, or even more abundant than, canonical antibiotic resistance mutations in clinical isolates (Extended Data Fig. 7).

Mobile resistance genes targeting recent antibiotics are diverse

ALE does not allow for the analysis of horizontally transferable resistance mechanisms. Therefore, we next analysed the abundance of mobile ARGs from environmental and clinical resistomes. We previously created metagenomic libraries from (1) anthropogenic soil microbiomes, that is, river sediment and soil samples at 7 antibiotic-polluted industrial sites in the close vicinity of antibiotic production plants in India; (2) human gut microbiomes, that is, stool samples from 10 European individuals who had not taken any antibiotics for at least 1 year before sample donation; and (3) clinical microbiome samples from a pool of 68 MDR bacteria isolated in healthcare facilities or obtained from strain collections27 (Supplementary Table 5). Each library contained up to 5 million DNA fragments (contigs), corresponding to a total coverage of 25 Gb (that is, the size of ~5,000 bacterial genomes). Established functional metagenomic protocols were used to detect small DNA fragments (~1.7 kb long on average) in these libraries that confer resistance in intrinsically susceptible clinical E. coli and K. pneumoniae strains27. Specifically, these DNA fragments were heterologously expressed in these two strains.

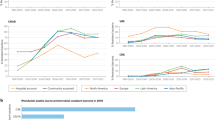

A total of 690 independent DNA fragments conferred increased resistance, by up to 256-fold, against the recent and control antibiotics tested in their bacterial hosts (Supplementary Data 2). Overall, there is no significant difference in the number of contigs conferring resistance between the antibiotics under development and their corresponding within-class controls (paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.791; Fig. 4a). However, we detected no resistance-conferring DNA fragment against tridecaptin M152-P3 in any of the metagenomic libraries and host species (Fig. 4a). The clinical microbiome contributed as much as 57.8% of the antibiotic-resistance-conferring DNA segments (Fig. 4a), more than 2× the contributions of the soil and gut microbiomes (25.5% and 24.8%, respectively). In total, 642 non-redundant open reading frames (ORFs) were detected, many of which were present in multiple DNA fragments (Supplementary Data 2). Of the 690 DNA fragments, 77% showed close sequence similarity to known resistance genes (that is, ARGs) in relevant databases (Supplementary Data 2). These ARGs are involved in antibiotic inactivation, antibiotic efflux or protection of the antibiotic targets and they have a diverse phylogenetic origin (Supplementary Data 2).

a, Overview of the sequencing results of antibiotic-resistant bacteria generated by functional metagenomics. Functional selection of metagenomic libraries with 18 antibiotics resulted in numerous distinct resistance-conferring DNA contigs, with the only exception of tridecaptin M152-P3 (TRD). The top bar plot shows the number of unique DNA fragments (contigs) that confer resistance to control (blue) and recent (orange) antibiotics, respectively, whereas the bottom bar plots show the distribution of the identified resistance-conferring contigs across metagenomic libraries and the percentage of mobile ORFs per antibiotic, respectively. ORF mobility was defined by evidence for recent horizontal gene transfer events or presence on mobile plasmids (Methods). The row below the bar plots denote the class of antibiotics analysed. We observed no significant difference in the number of contigs between recent antibiotics and their corresponding within-class controls (paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test, two-sided, P = 0.4973). The same pattern is true for the percentage of mobile ORFs (paired signed-rank Wilcoxon test, P = 0.576). For antibiotic abbreviations, see Table 1. b, Overlap in the set of resistance-conferring DNA fragments (contigs) across antibiotics. Each node represents a recent (orange) or control (blue) antibiotic, and the links indicate overlap in the resistance-conferring DNA contigs identified in functional metagenomic screens. The thickness of the link indicates the extent of overlap (calculated by Jaccard similarity) between antibiotic treatments. The size of the nodes corresponds to the total number of detected DNA fragments per antibiotic. The class to which a given antibiotic belongs is also indicated. c, Risk analysis of putative ARGs. The figure shows the total number (top) and fraction (bottom) of health-risk ARGs across functional screens to different antibiotics. ARGs were designated as potential risk if they fulfilled at least two of the following three criteria: if they were (1) mobile, (2) present in human-associated microbiomes, and (3) human pathogens. Blue and orange colours depict control and recent antibiotics, respectively. The analysis revealed a significant variation in the fraction of potential-risk ORFs across the antibiotics tested (proportion test, two-sided, P < 0.05), indicating that certain antibiotics are more likely to be associated with potential-risk ORFs compared with others.

The putative resistance mechanisms associated with genomic mutations and ARGs differed substantially from each other (Extended Data Fig. 8). In particular, antibiotic efflux and target alteration were the two most ubiquitous resistance mechanisms derived from genomic mutations (Extended Data Fig. 9a), whereas antibiotic inactivation was more prominent among hits derived from functional genomic screens (Extended Data Fig. 9b). For a detailed comparison of genomic mutations and mobile resistance genes, see Supplementary Note 5. In addition, our analysis revealed the contribution of non-canonical resistance mechanisms (Supplementary Note 6).

Prevalence of MDR-conferring DNA segments

We observed overlap in the set of DNA fragments conferring resistance to recent and control antibiotics (Fig. 4b), including antibiotic pairs with different modes of action. For example, 69 contigs conferring resistance to both the topoisomerase inhibitor moxifloxacin and the tetracycline antibiotic omadacycline were detected. The analysis identified 2 key genes, baeR and ramA, carried by 73.9% of these contigs. BaeR and RamA induce expression of the MdtABC/AcrD28 and AcrAB–TolC efflux pump complexes29, respectively, with RamA also downregulating expression of the porin OmpF30. The fact that some DNA fragments confer resistance to multiple antibiotics may reflect similarities in chemical structure or mechanism of action. Therefore, we investigated the impact of chemical similarity on co-resistance by quantifying the structural similarity of antibiotic pairs using SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) identifiers and examining their correlation with profile similarity based on detected DNA fragments. We found that overlap in resistance-conferring DNA fragments is more likely for antibiotic pairs with similar structures (Spearman’s rank correlation, two-sided test, R = 0.43, P < 0.01). This pattern holds when only antibiotic pairs belonging to different antibiotic classes were considered (Spearman’s rank correlation, two-sided test, R = 0.31, P < 0.01). However, there are notable deviations from this general pattern. For instance, although SPR-206 is a derivative of polymyxin B, there are no DNA fragments able to confer resistance to both antibiotics. Similarly, although cefiderocol shares structural similarity to other cephalosporins studied, the addition of a chlorocatechol group transforms it into a siderophore31 and the majority of DNA fragments conferring resistance to cefiderocol are unique to this antibiotic. In summary, these analyses indicate that certain alterations in chemical structure that affect the mode of action or uptake of the antibiotic can lead to major changes in the associated resistance mechanisms.

Health-risk analysis of resistance genes

Next, we used a previously developed omics-based framework for assessing the health risk of ARGs32. We considered three major ARG criteria: (1) gene mobility, (2) presence in microbiomes associated with the human body, and (3) bacterial host pathogenicity. ARGs were designated as ‘potential risk’ if they fulfilled at least two of the three criteria.

Using established methods, gene mobility was defined by evidence for recent horizontal gene transfer events in nature and the presence of the ARGs on natural plasmids derived from diverse environments (Methods). Of the putative ARGs, 20.7% were found to be carried by plasmids or to have been subjected to recent horizontal gene transfer events (Fig. 4a, Extended Data Fig. 10a and Supplementary Data 2). Next, we analysed putative ARG abundance in human microbiomes. We identified close homologues of the ARGS detected by our functional metagenomic screen in the non-redundant Global Microbial Gene Catalog (GMGCv1). The catalogue summarizes results from over 13,000 publicly available metagenomes across 14 major habitats, including microbiomes from the human body, domestic animals, wastewater, fresh water and built environments.

Most microbial genes in the catalogue are specific to a single habitat33. In contrast, 27.6% of the putative ARGs detected in the resistance screens to recent antimicrobials were found in multiple habitats, further indicating their potential mobility. In addition, when only habitats associated with the human body (human gut, oral, skin, nose, blood plasma or vagina microbiomes) were considered, this figure rises to 32.7%, indicating that these microbiomes could be a rich source of resistance genes to new antibiotics (Extended Data Fig. 10b). Reassuringly, ARGs associated with the human body were also more prevalent in human-related abiotic habitats (wastewater or built environment) than other ARGs (Fisher’s test, odds ratio = 125, P < 0.0001). Of the ARGs, 36.6% are already present in the genomes of bacterial pathogens with critical clinical importance (Extended Data Fig. 10b, Methods and Supplementary Data 2). The detected ARGs are also prevalent in the genomes of E. coli strains isolated from three main habitats (agriculture, human or wild animal hosts; Supplementary Note 7).

Of the 642 ARGs, 24.5% were designated as potential risk (Supplementary Data 2). These ARGs are anticipated to have the greatest potential for catalysing multidrug resistance in pathogens through a combination of hazardous traits: broad host compatibility enabled by mobility, alongside enrichment in human microbiomes and in bacterial pathogens. However, a significant variation was observed in the frequency of potential-risk ARGs across antibiotics (Fig. 4c). A notable example is apramycin sulfate, an antibiotic extensively used in veterinary medicine for decades that is now in clinical trials for human applications. Only 2 of the 63 putative ARGs (3.2%) associated with this antibiotic were designated as potential risk due to a shortage of evidence for their mobility and presence in bacterial pathogens.

By contrast, several potential-risk ARGs were detected for recent antibiotics, such as sulopenem (N = 16), cefiderocol (N = 22) and ceftobiprole (N = 26). These potential-risk ARGs included several β-lactamases, such as New-Delhi-metallo (NDM) and Verona integron metallo-β-lactamases (Extended Data Fig. 10b). Given the previous expectation of cefiderocol’s lower propensity for resistance development, the high number of potential-risk ARGs to cefiderocol is notable.

Integrating evidence on resistance to new antibiotic candidates

An ideal antibiotic candidate is expected to meet several essential criteria: (1) a broad antibacterial spectrum to ensure effectiveness against a wide array of pathogens, (2) low tendency for development of resistance through genomic mutations, (3) scarcity of intrinsic and horizontally transferred mobile ARGs, and (4) a low prevalence of associated resistance mechanisms in human-associated microbiomes and bacterial pathogens. Unfortunately, none of the compounds investigated in this study simultaneously satisfied all these requirements (Fig. 5). By synthesizing several collected data, we calculated an average metric value that served for the ranking of new antibiotic candidates based on their resistance profiles and that showed significant heterogeneity across antibiotic classes (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.05; Fig. 5). According to this ranking, recent antibiotics targeting bacterial membranes are anticipated to show reduced susceptibility to resistance development in natural settings compared with tetracyclines and topoisomerase inhibitors (Dunn post hoc test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons, P < 0.05). However, there remains considerable room for improvement in their efficacy.

The heat map shows various metrics for each antibiotic studied in this work. The metrics include: (1) prevalence of panel strains with reduced susceptibility—the fraction of bacterial strains from a selected pathogen panel with high initial MIC values (Methods); (2) tendency for resistance—the fraction of adapted lines with a relative MIC exceeding 16, representing the 25% quantile of all relative MIC values; (3) diversity of genes with mutations—the fraction of orthogroups showing mutations during ALE or FoR assays with each antibiotic, adjusted by the total number of mutated orthogroups; (4 and 5) mutation prevalence in natural E. coli or A. baumannii strains—the fraction of laboratory-observed adaptive mutations that are already present in natural E. coli and A. baumannii strains, respectively; (6) diversity of horizontally transferred contigs—the count of unique DNA fragments per antibiotic, normalized by the total contig count in functional metagenomics studies; and (7) prevalence of potential-risk ARGs—the ratio of ARGs considered potential risk, based on meeting at least two of three specified health-risk criteria (Methods), among all ARGs detected for each antibiotic. Grey colours denote missing values due to initial resistance in the studied species. Antibiotics are ordered by the average metric value. Blue and orange indicate control and recent antibiotics, respectively. The row below the heat map denotes the class of the antibiotics analysed.

Discussion

In this work, we showed that bacterial resistance to antibiotics currently in development generally evolves rapidly in vitro. These patterns also hold for compounds that have new or dual modes of action and that were previously thought to be relatively immune to bacterial resistance in the laboratory (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 4a). Notably, genomic mutations that accumulated during laboratory evolution may prove to be clinically relevant because they are also prevalent in the genomes of clinical bacterial isolates (Fig. 3c). These results predict that resistance to new antibiotics could arise through selection for pre-existing resistant strains via mutations and with horizontally transferable genetic elements. These results suggest that overlap in resistance mechanisms and prolonged antibiotic exposure in clinics and agriculture have selected for resistance mechanisms that reduce susceptibility to both antibacterial compounds in use and those still in development. Given that overlap was increased for antibiotics with structural similarity (Fig. 4b), these observations suggest that minor chemical modifications are insufficient to circumvent established resistance mechanisms.

Antibiotics targeting multiple cellular functions are generally expected to be less prone to bacterial resistance. For example, it has been stated that SCH-79797, a dual-targeting antibiotic, effectively kills a wide range of bacterial pathogens without detectable resistance14 but the underlying data were limited. In contrast to these claims, we found that a relatively low but notable resistance emerged via mutations of regulatory genes of efflux mechanisms (acrR, adeN and adeS). Similarly, previous studies claimed that the chance of high-level delafloxacin and gepotidacin resistance via target mutations is limited due to the dual-targeting nature of these antibiotics25,34. In addition, these antibiotics were supposed to be poor substrates for established bacterial efflux pumps35. In our studies, however, high levels of resistance to these antibiotics evolved via target mutations and mutations often occurred in established efflux pumps (acrB) or their corresponding regulatory genes (acrR, adeN and nfxB).

Omadacycline was previously thought to evade resistance via tetracycline-specific efflux pumps based on the lack of cross-resistance36. In our study, however, contigs containing tetracycline-specific efflux pump genes tetA and tetX came up as hits against omadacycline.

Due to its unique mechanism of uptake, resistance to cefiderocol was supposed to be relatively immune to the development of resistance31. However, baeS and crP, two regulatory genes involved in antibiotic efflux, were mutated in response to cefiderocol. Indeed, previous work showed that mutations in these genes constitutively activate the BaeSR two-component regulatory system to increase the expression of the MdtABC efflux pump37. In addition, in our functional metagenomic screen, carbapenemases NDM-15, NDM-22 and NDM-27 provided resistance to cefiderocol. Similarly, sulopenem is a broad-spectrum thiopenem β-lactam antibiotic being developed to treat infections caused by MDR and cephalosporin-resistant bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriales group38. However, it was prone to resistance in multiple screens. In particular, functional metagenomics identified several DNA fragments carrying NDM β-lactamase genes as able to confer resistance (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Data 2).

Eravacycline was specifically designed to overcome resistance to common tetracycline-specific efflux and ribosomal protection mechanisms39. Although eravacycline has a relatively broad antimicrobial spectrum, resistance to this compound evolves rapidly in the laboratory through modification of efflux pump activities.

Resistance to the peptide-based antibiotic, SPR-206, readily emerged through genomic mutations. SPR-206 is in clinical trials and has potent activity against a wide range of MDR bacteria40. However, an increase in resistance level as high as 128-fold emerged in K. pneumoniae because of single mutations in the BasS/BasR 2-component regulatory system.

Our work highlights the concern that antibiotic development is currently dependent solely on susceptibility indicators in various bacterial pathogens. Although many of the new antibiotics indeed have an improved antibacterial spectrum compared with their predecessors, our studies show that this is rarely paired with favourable resistance properties. Specifically, eravacycline shows improved antibacterial activity against a panel of bacterial pathogens; however, it is especially prone to resistance via genomic mutations and horizontal gene transfer (Figs. 2a and 4a).

Future application of the same antibiotic to initially susceptible pathogens can have different outcomes depending on their capacity to evolve resistance21,41. Indeed, we have found that the level of resistance achieved during ALE was contingent on the bacterial species and strains studied, in an antibiotic-specific manner (Extended Data Fig. 5c). This variability may stem from strain-specific differences in initial susceptibility to a given antibiotic, presence of efflux pumps and/or the influence of specific ‘potentiator’ genes, which facilitate unconventional mutational pathways towards resistance through epistatic interactions with resistance mutations. These hypotheses will be studied thoroughly in future work, which might aid in developing species-specific therapeutic options to counter the rapid development of resistance42. Our work also highlights the risk that antibiotic development programmes waste considerable resources on antibiotic candidates prone to resistance if they concentrate only on a single bacterial species or only on resistance emergence arising from genomic mutations. An important limitation of this study is the lack of systematic investigation of trade-offs of antibiotic resistance, especially on bacterial fitness and virulence—an issue that will be covered in future work. Future studies should also decipher the exact role of the identified mutations by reintroducing them individually and in combinations into wild-type genetic backgrounds, and studying their impact on the susceptibility of the resulting mutant strains to new antibiotics. In addition, resistance to Gram-positive-specific antibiotic candidates and combination therapies involving new antibiotics will be studied elsewhere.

In sum, the framework provided here highlights the importance of testing the evolution and mechanisms underlying resistance with complementary methods and in multiple relevant bacterial species. We argue that applying this framework is feasible and advisable for candidate antibiotics before acceptance for clinical use, as it enables a more accurate assessment of their immediate efficacy, long-term utility and potential for resistance emergence. Although our findings indicate that none of the compounds tested meets all the criteria for an ideal future antibiotic, they also highlight opportunities for improving certain critical properties (Fig. 5). This underscores the pressing need for innovative approaches in the discovery and optimization of new antibiotics, particularly those that address the challenges of efficacy and resistance.

Methods

Strains, antibiotics and media

This study focused on multiple bacterial strains. We tested the activity spectrum of the antibiotics in this study on a set of 40 clinically relevant pathogenic strains of 4 species (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa; see the whole list of pathogens in Supplementary Table 4). For the FoR and ALE experiments, two strains per species were chosen: for SEN strains, E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, A. baumannii ATCC 17978 and P. aeruginosa ATCC BAA-3107; and for MDR strains, E. coli NCTC 13846, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, A. baumannii ATCC BAA-1605 and P. aeruginosa LESB58. For E. coli, we chose the ATCC 25922 strain as a SEN strain due to its widespread use in the literature, and an mcr1-carrying NCTC 13846 strain as the MDR strain due to the high interest in the impact of this mobile resistance gene on colistin resistance43. For the other three species, SEN and MDR strains were selected based on the highest number of control antibiotics to which they showed sensitivity or resistance, respectively, with the additional criterion for MDR strains that they should be part of an official strain collection (Extended Data Fig. 3). Functional metagenomic screens were performed with E. coli ATCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 strains. Deep-scanning mutagenesis (DIvERGE) was performed with E. coli K12 MG1655 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 strains. The collection of clinical samples was performed in a previous study44. No new samples were collected for the current study. The collection of clinical samples complies with all relevant ethical regulations and was approved by the Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of the Hungarian Health Science Council (BMEÜ /271-3/2022/EKU). As specified in Material Transfer Agreements, these isolates and their derivatives cannot be transferred to a third party as they can be used only at the recipient organizations and only in the recipient scientists’ laboratories under the direction of the recipient scientists or others working under their direct supervision.

A total of 19 antibiotics were applied in this study from 6 different antibiotic families: 13 newly developed (recent) antibiotics, which are in different phases of clinical trials, and 6 conventional (control) antibiotics with a long clinical history from each antibiotic family. For names, abbreviations and further details, see Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3. Antibiotics were custom-synthesized or purchased from several distributors (Supplementary Table 3). For preparation, each antibiotic stock solution was filter-sterilized and kept at −20 °C until use. For more details on recent and control antibiotics, see Supplementary Note 1, Table 1 and Supplementary Table 3. For data on clinical breakpoints and peak plasma concentrations, see Supplementary Table 3. Tridecaptin M152-P3 was synthesized using standard Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis. The process began with resin preparation, followed by iterative Fmoc deprotection and amino acid coupling steps using HBTU as the coupling reagent. After assembly of the peptide chain, the product was cleaved from the resin using a TFA-based cocktail, precipitated with cold isopropyl ether, and dried under vacuum. The crude peptide was then purified using preparative HPLC, yielding 233.4 mg of the product with 98.17% purity as confirmed by LC-MS and HPLC.

The synthesis of POL7306 involved three main stages: the preparation of two intermediate peptides (Compound 1 and Compound 2) and their subsequent connection. Fmoc-based solid-phase peptide synthesis was used, beginning with the attachment of amino acids to a resin, followed by deprotection and coupling steps. After peptide assembly, the crude peptides were cleaved from the resin and purified by precipitation and washing with isopropyl ether. The final connection of the two peptides was performed on a Rink Amide resin, followed by cleavage with TFA and purification through prep-HPLC. The final product, POL7306, was obtained with 96.71% purity and confirmed by LCMS and HPLC.

For detailed synthesis route see Supplementary information.

Unless otherwise indicated, cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth 2 (MHB; Millipore) medium was used throughout the study, except for cefiderocol and the folate biosynthesis inhibitor SCH-79797. Following the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing’s (EUCAST) recommendation on cefiderocol, iron-depleted MHB media was used45. To maximize antibacterial activity of SCH-79797, based on previous experience with folate biosynthesis inhibitor antibiotics46, Minimal Salt (MS) medium was used (1 g l−1 (NH4)2SO4, 3 g l−1 KH2PO4 and 7 g l−1 K2HPO4 supplemented with 1.2 mM Na3C6H5O7·2H2O, 0.4 mM MgSO4, 0.54 μg ml−1 FeCl3, 1 μg ml−1 thiamine hydrochloride, 0.2% casamino acids and 0.2% glucose).

High-throughput MIC measurements

A standard serial broth microdilution technique47 was used to determine MICs, as suggested by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. A robotic liquid-handling system was used to automatically prepare 11–16 step serial dilutions in 384 well microtiter plates. A total of 5 × 105 bacterial cells per ml were inoculated into each well containing 60 µl medium. Bacterial cultures were incubated at 37 °C with continuous shaking (300 rpm) for 18 h (2 replicates from each). Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical density (optical density at 600 nm (OD600) values using a Biotek Synergy microplate reader). MIC was defined as the antibiotic concentration of complete growth inhibition (that is, OD600 < 0.05). The same protocol was used to estimate antibiotic susceptibility of laboratory-evolved lineages. Relative MIC was calculated as follows: log2(MICevolved/MICancestor). Increase in MIC was calculated as follows: log10(MICevolved − MICancestor).

We aimed to perform both FoR and ALE assays with all selected 8 bacterial strains; however, 34% of all antibiotic–strain combinations (N = 52) were excluded from further experiments due to modest initial drug efficacy (that is, MIC > 4 µg ml−1), rendering them less relevant for clinical use. The prevalence of panel strains with reduced susceptibility to a certain antibiotic was estimated by calculating the fraction of panel strains with high initial MIC values.

FoR assays

To estimate the frequency of spontaneous mutations that confer resistance in a microbial population, the FoR assay was used. Using standard protocols16,17,18,19, approximately 1010 cells from stationary-phase cultures were plated to antibiotic-containing MHB plates. Before plating, bacteria were grown overnight in MHB medium at 37 °C, 250 rpm, collected by centrifugation (3,880g for 10 min) and washed once in equal volumes of MHB. From this concentrated bacteria suspension, ~1010 cells were plated to agar plates containing the selective drug at the desired concentration (that is, 2×, 4×, 8× and 20× MIC of each given antibiotic). Unless otherwise indicated (see ‘High-throughput MIC measurements’ above), MHB agar medium was used throughout the study. All experiments were performed in three replicates. Plates were grown at 37 °C for 48 h. Total colony-forming units were determined simultaneously in each experiment by plating appropriate dilutions to antibiotic-free MHB agar plates. Resistance frequencies for each bacterial strain were calculated by dividing the number of emergent colonies by the initial viable cell count. Ten bacterial colonies from the highest antibiotic concentration were selected for further MIC measurements and whole-genome sequence analysis.

High-throughput ALE

A previously established protocol48,49 was used for ALE, with the aim to ensure that populations with the highest level of resistance were propagated further. Starting with an antibiotic concentration resulting in ~50% growth inhibition, 10 parallel populations per antibiotic–ancestor strain combination were grown for 72 h at 37 °C with continuous shaking (300 rpm). As rapid degradation has been observed for β-lactams and cephalosporins in liquid laboratory media50, ceftobiprole, cefiderocol and cefepime were not subjected to ALE. Unless otherwise indicated, MHB medium was used. After each incubation period, 20 μl of each bacterial culture was transferred to 4 new independent wells containing freshly prepared medium containing different antibiotic concentrations (0.5×, 1×, 1.5× and 2.5× the concentration of the previous step). A chessboard layout was used on the plate to monitor potential cross-contamination events. Cell growth was monitored before each transfer by measuring the OD600 value (Biotek Synergy 2 microplate reader). Only populations with the highest drug concentration (and reaching OD600 > 0.2) were selected for further transfer. The evolution experiment was generally continued for 20 transfers, resulting in a total of 728 evolved lines (78 lines were omitted because of limited growth).

Whole-genome sequencing

To identify potential antibiotic-resistance-conferring mutations, we generally selected two to five lines from FoR and ALE experiments, respectively, for whole-genome sequencing. Resistant populations were grown overnight in antibiotic-free medium. DNA isolation from overnight cultures was performed with the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was eluted with 120 µl RNAse-free sterile water in 2 elution steps. The eluted DNA (60 µl) was then concentrated using the DNA Clean and Concentrator Kit (Zymo), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final DNA concentration was measured using a Qubit Fluorometer and concentration was set to 1 ng ml−1 in each sample. Sequencing libraries from isolated genomic DNA were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequencing libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer using mid or high output flow cells to generate 2× 150 bp paired-end reads.

To determine and annotate the variants, we mapped the sequencing reads to their corresponding reference genomes using an established method (Burrows–Wheeler Aligner)51. From the aligned reads, PCR duplicates were removed with the Picard MarkDuplicates tool (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). We removed every read that had been aligned with more than six mismatches (disregarding insertions and deletions). The SNPs and insertions or deletions were called using Freebayes52 with the following parameters: -p 5–min-base-quality 28. The identified variants were filtered using the vcffilter tool from vcflib53 using the following parameters: –f ‘QUAL > 100’. To avoid missing rare but valid hits, we did not set a lower limit for the prevalence of rare variants. If necessary, mutations were also manually inspected within the aligned reads using IGV54 to reduce Burrows–Wheeler alignment or freebayes artefacts. Finally, the variants were annotated with SnpEf and we only kept those that were not present in the ancestor. We filtered out mutations that appeared in more than nine lines because these variants are probably already present in the ancestor. Furthermore, mutations that appeared in less than nine but more than six lines were manually inspected to exclude sequencing artefacts. We also excluded mutations that affect 40 bp or longer repetitive regions, resulting in a filtered set of mutations. Lines containing mutations in the mutL, mutS or mutY genes, or lines with more than 19 mutations, defined by outlier filtering (third quartile + (3 × interquartile range)), were considered hypermutators and were subsequently discarded.

To analyse the presence or absence of mutations across genes and strain backgrounds, we first complemented the existing gene functional annotation for the eight bacterial strain backgrounds as follows. Nucleotide sequence and annotation files of six strains (E. coli ATCC 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, A. baumannii ATCC 17978, P. aeruginosa ATCC BAA-3107, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 and A. baumannii ATCC BAA-1605) were downloaded from the ATCC database (https://www.atcc.org/). For P. aeruginosa LESB58 and E. coli NCTC 13846 strains, genomic data were downloaded from NCBI Nucleotide (accession numbers FM209186.1 and GCA_900448335.1). Next, all genes in the GeneBank files, including hypothetical ones, were functionally annotated using PANNZER2 (refs. 55,56). To compare the sets of mutated genes across strain backgrounds, we determined genes that are shared across different strains by identifying groups of orthologous genes using OrthoFinder (v.2.5.4)57,58.

Bioinformatic analysis of mutations promoting growth in the laboratory based on previous work

We compiled a comprehensive list of 104 genes associated with medium adaptation in E. coli, as identified in 2 previous studies59,60. First, we examined our evolved E. coli strains for mutations within these genes. The DNA sequences of these genes from the E. coli strain MG1655 were retrieved from EcoCyc (v.26.0)61. We then aligned the sequences to the amino acid sequences of proteins in our reference genomes (SEN and MDR, separately) using the BLASTX tool (implemented in the rBLAST R package62). For each gene, we selected the alignment with the highest bit score, requiring a sequence identity of at least 80% and coverage of at least 80%. This approach resulted in 92 of the 104 genes being matched in each reference genome. Among these, 8 genes in the MDR strains showed 13 mutations and 7 genes in the SEN strains contained 15 mutations, totalling 11 genes with 28 mutations in at least 1 strain. As a next step, we investigated non-coding mutations in our evolved strains to ascertain if any were located in or adjacent to operons overlapping with the genes implicated in medium adaptation. This analysis did not reveal any non-coding mutations associated with the genes of interest.

Comparison of variants to public genomes of bacterial isolates

We assessed whether amino acid substitutions occurring in the FoR and ALE samples are present in natural populations of E. coli and A. baumannii as follows. We compiled a comprehensive genomic dataset for E. coli strains by downloading assembled genome sequences or unassembled reads and metadata, from four sources: (1) the JGI Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (IMG) database63 (on 29 January 2020), (2) the NCBI Prokaryotic RefSeq collection (available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/; on 29 January 2020), (3) genomes that were analysed in ref. 64, and (4) genomes that were analysed in ref. 65.

After trimming the adaptors with the Cutadapt v.3.2 program66, we de novo assembled the next-generation sequencing short reads (downloaded from the Sequence Read Archive database67) of genomes from sources (3) and (4) using the SPAdes v.3.14.1 software68. Then we applied the BUSCO v.5.0.0. workflow69 to exclude genome sequences with less than 95% of the BUSCO genes, indicating inadequate completeness or quality. When multiple genome sequences belonged to the same BioSample identifier, only the one with the highest BUSCO score, longest sequence and fewest contigs were kept, and all metadata of the original sequences were merged. This resulted in 20,786 E. coli genomes (Supplementary Data 1) for which gene prediction was performed using Prodigal (v.2.6.3)70 to obtain protein-coding gene annotations that are consistent across the genomes. ORFs with less than 100 amino acids were filtered out. Strains were classified as pathogens and non-pathogens based on their genomic metadata. For A. baumannii strains, we downloaded all available assembled genome sequences from the NCBI Prokaryotic RefSeq genome collection (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/) on 12 September 2022. Then we applied genome filtering with 95% completeness using BUSCO v.5.4.6. and protein prediction using Prodigal as described above for E. coli. This resulted in 15,185 A. baumannii genomes (Supplementary Data 1).

Next, we searched for the presence of each amino-acid-changing SNP across the E. coli and Acinetobacter genome collections as follows. First, we performed a sequence similarity search of each gene carrying a given variant using DIAMOND BLAST (v.2.0.2)71 using an e-value (expect-value) of 0.00001 with 90% coverage and 90% identity to identify homologues among the genomes. In the next step, we performed multiple sequence alignment using MAFFT (v.7.475)72 with the –retree 2 option. Then we analysed the amino acid frequency across the alignments in all mutated positions. All E. coli and A. baumannii variants that were present in the corresponding species’ genome collection and appeared more than once in our FoR and ALE samples were selected for further analysis.

Functional metagenomic screens

Resistance-conferring DNA fragments in the environment were identified by functional selection of metagenomic libraries. In a previous study27, we created metagenomic libraries to obtain environmental and clinical resistomes, including (1) river sediment and soil samples from 7 antibiotic-polluted industrial sites in the close vicinity of antibiotic production plants in India73 (anthropogenic soil microbiome), (2) faecal samples from 10 European individuals who had not taken any antibiotics for at least 1 year before sample donation (that is, gut microbiome), and (3) samples from a pool of 68 MDR bacteria isolated in healthcare facilities or obtained from strain collections (Supplementary Table 5). For full details on library construction, see ref. 27.

Briefly, environmental and genomic DNA was isolated using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) and the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma), respectively. Environmental and genomic DNA was enzymatically fragmented, followed by size selection of 1.5–5 kb long fragments. Metagenomic inserts were cloned into a medium-copy-number plasmid and flanked by two 10 nt-long barcodes (referred to as uptag and downtag). Library sizes ranged from 2 to 6 million clones with an average insert size of 2 kb.

Libraries were introduced into K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 and E. coli ATCC 25922 by bacteriophage transduction (DEEPMINE)27 and electroporation, respectively. DEEPMINE uses hybrid T7 bacteriophage-transducing particles to alter phage host specificity and efficiency for functional metagenomics in target clinical bacterial strains.

In this study, we followed previously described protocols with two minor modifications. First, transducing hybrid phages were generated with a T7 phage lacking the gp11, gp12 and gp17 genes, constructed as previously described74. Second, we used a new phage tail donor plasmid for complementing the deleted phage tail genes. This plasmid was cloned using the ΦSG-JL2 phage tail coding genes, the packaging signal region of T7 phage and the pK19 plasmid backbone based on previous work75.

Functional selections for antibiotic resistance were performed on MHB agar plates containing a concentration gradient of the antimicrobial compounds76,77. Cells containing the metagenomic libraries were plated in a cell number covering at least 10× the size of the corresponding metagenomic library. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For each functional selection, a control plate was prepared with the same number of cells containing the metagenomic plasmid without a cloned DNA fragment in its multicloning site. These control plates showed the inhibitory zone of the antimicrobial compound. To isolate the resistant clones from the libraries, sporadic colonies were identified above the inhibitory zone based on the control plate by visual inspection. Colonies were then collected for plasmid isolation (Thermo Scientific GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit). Metagenomic inserts in the resistant hits were sequenced using two complementary sequencing methods. First, random 10 nt barcodes flanking the metagenomic inserts (pZET_bc_F_SrfI_v2, pZET_bc_R; Supplementary Table 7) on the resistant plasmids from each selection experiment were PCR amplified. For this, we used primers that contain 2× 8-nt-long barcodes specific for each selection experiment (with codes starting with Uptag-UF, Uptag-UR, pZET_Down_F and pZET_Down_R; Supplementary Table 7). Amplicons were pooled, size-selected on agarose gel and sequenced by Illumina. Second, metagenomic inserts and their flanking 10 nt uptag and downtag barcodes were sequenced by Nanopore.

Annotation of ARGs

Consensus insert sequences from Nanopore sequencing were matched with the respective selection experiment using the data from Illumina sequencing. First, sequencing reads from Illumina sequencing were demultiplexed using the 2× 8-nt-long barcodes specific to the selection experiment, and then the demultiplexed reads were matched with the consensus insert sequences using the random 10-nt-long barcodes specific to the metagenomic inserts. To reduce redundancy and spurious matches, the list of metagenomic contigs were filtered (1) to unique barcodes, keeping barcodes with the highest Nanopore read count; and (2) to contigs that were supported by at least eight Nanopore reads and five Illumina reads. Prediction of ARGs within these contigs was based on ORF prediction using Prodigal v.2.6.3 (ref. 70), followed by searching the annotated ORFs within the CARD and ResFinder databases78,79. Searches were performed using BLASTX from NCBI BLAST v.2.12.0 (ref. 80) with a 10−5 e-value threshold and otherwise default settings. ORFs were clustered at 95% identity and coverage using CD-HIT v.4.8.1 (ref. 81) and only 1 representative ORF was kept for each cluster. The inserts were classified based on whether or not any ARGs were found in them, and whether or not at least one of these ARGs was associated with the antibiotic being tested in that particular selection experiment. Close orthologues of the host-specific proteins were excluded from further analyses by performing a BLASTP search of each ORF on host proteomes (https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000001734, https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000029103, downloaded on 24 November 2022) and removing each ORF with higher than 80% sequence similarity. The potential origin of the inserts was assessed by searching the Nanopore contigs within the NCBI Prokaryotic RefSeq Genomes database82 using BLASTN from NCBI BLAST v.2.12.0 with default settings and resolving taxids to hierarchical classifications using R83 and the taxizedb package84,85,86.

Catalogue of mobile ARGs

A mobile gene catalogue (that is, a database of recently transferred DNA sequences between bacterial species87) was created previously27. Briefly, 1,377 genomes of diverse human-related bacterial species from the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes database87 and 1,417 genomes of Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens from the NCBI RefSeq database were downloaded. Using NCBI BLASTN 2.10.1+ (ref. 80), we searched the nucleotide sequences shared between genomes belonging to different species. The parameters for filtering the NCBI BLASTN 2.10.1+ BLAST results were as follows: minimum percentage of identity, 99%; minimum alignment length, 500; and maximum alignment length, 20,000. Then, to generate the mobile gene catalogue, we compared them with the merged CARD 3.1.0 (ref. 78) and ResFinder (d48a0fe) databases79 using DIAMOND v.2.0.4.142 (ref. 71). Natural plasmid sequences were identified by downloading 27,939 complete plasmid sequences from the PLSDB database (v.2020-11-19)88. Then the representative sequences of the isolated 114 ARG clusters were searched using BLASTN both in the mobile gene catalogue and in natural plasmid sequences with an identity and coverage threshold of 90%. ARGs were considered mobile if they were present in the mobile gene catalogue and/or in natural plasmid sequences.

Detecting ARGs present in human-associated microbiome and human pathogens

To identify close homologues of the ARGs discovered in our functional metagenomic screens, we used GMGCv1 (ref. 33). This extensive, non-redundant database comprises over 2.3 billion unigenes, derived from more than 13,000 metagenomes across 14 major habitats, and includes detailed phylogenetic origin information. We applied a BLASTN89 search to compare the nucleotide sequences of the ORFs from our screens with all unigenes in the GMGCv1, using a stringent identity and coverage threshold of 90%. ARGs were considered to be associated with the human body if they showed sequence homology to unigenes present in at least five samples in at least one of the following environments: human gut, oral cavity, skin, nose, blood plasma or vagina. To further investigate the association of the detected ARGs with human pathogens, we analysed (1) their presence in the clinical metagenomic library, and (2) their phylogenetic relationships to pathogens, specifically focusing on ESKAPE pathogens and those listed in the WHO priority lists (A. baumannii, P. aeruginosa, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Shigella) by leveraging species information metadata from the GMGCv1 database for each BLASTN hit.

Detecting ARGs across E. coli phylogroups, host species types and geographic regions

Host type, geographic location and phylogroup were determined for a dataset of 16,272 E. coli genomes in previous work90. The initial complete dataset of 26,881 E. coli genomes was retrieved from the NCBI RefSeq database (in February 2022) and filtered for genomes with complete metadata. Clermont phylogrouping91 was performed in silico using the EzClermont command-line tool92, whereas host and location metadata were retrieved and categorized using the Bio.Entrez utilities from Biopython v.1.77. All genomes were sorted into the following host species categories: human, agricultural/domestic animals and wild animals. This was achieved using regular expressions constructed by manually reviewing text in the ‘host’ field of the biosample data for each accession number. Geographic locations were split into 20 subregions according to Natural Earth data93. A local BLASTP search was performed for this collection of E. coli genomes against a database of the predicted ARG ORFs identified in functional metagenomic screens, using default parameters. ARGs with both 90% amino acid identity and 90% query coverage per subject, and present in no more than 10% of the examined E. coli genomes, were analysed further.

DIvERGE mutagenesis

We performed deep-scanning mutagenesis in the target genes of moxifloxacin, an established topoisomerase inhibitor. The quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR)94 of the gyrA and parC genes were subjected to a single round of mutagenesis using DIvERGE in E. coli K12 MG1655 and K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031. A previously described workflow20 was used with minor modifications. Briefly, cells carrying the pORTMAGE311B plasmid (Addgene number 120418) were inoculated into 2 ml LB medium plus 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin and were grown at 37 °C with continuous shaking (250 rpm) for 12 h. From this starter culture, 500 μl stationary-phase culture was propagated in 50 ml of the same fresh medium under identical conditions. Induction was initiated at a fixed population density (OD600 = 0.4) by adding 50 μl of 1 M m-toluic acid (dissolved in 96% ethyl alcohol; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30–45 min at 37 °C. After induction, cells were cooled on ice for 15 min. Next, cells were washed three times with sterile ice-cold ultrapure distilled water. Finally, the cell pellet was resuspended in 800 μl sterile ultrapure distilled water and kept on ice until electroporation.

To perform DIvERGE mutagenesis, the corresponding gyrA and parC QRDR-targeting oligonucleotides were mixed in equimolar amounts. Of the 500 μl oligonucleotide mixture, 2 μl was added to 40 μl electrocompetent cells in 5 parallel samples. The oligonucleotides we used are listed in Supplementary Table 7. After electroporation, the parallel samples were pooled and suspended in 25 ml fresh LB medium to allow for cell recovery (37 °C and 250 rpm). After a 60 min recovery period, an additional 25 ml LB medium was added and cells were grown for an additional 24 h.

To select clones with reduced susceptibility to moxifloxacin, 500 μl of each mutant cell library was spread onto moxifloxacin-containing MHB agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Finally, 20-20 antibiotic-resistant clones were selected randomly and analysed further by capillary sequencing using the PCR primers listed in Supplementary Table 7.

Efflux activity measurements

Measuring the accumulation of the fluorescent Hoechst dye is known as a robust and rapid method for monitoring efflux activity/membrane permeability in bacteria95. This method is based on the intracellular accumulation of the fluorescent probe Hoechst 33342 (Bisbenzimide H 33342; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were grown overnight in MHB, then 20 µl of the overnight culture was used to inoculate 2 ml of MHB liquid medium and then the cells were grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600 = 0.4–0.6). Bacterial cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 4,500g for 30 min. Next, cells were washed and resuspended in the buffer containing 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) and 5 mM glucose. The OD600 of the cell suspensions was adjusted to 0.1, and 0.18 ml of each suspension was transferred to 96 well plates (CellCarrier-96 Black Optically Clear Bottom; Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were incubated in a Synergy H1 microplate reader at 37 °C and 25 μM Hoechst 33342 was added to each well. The ancestor strain was treated with an efflux inhibitor agent (phenylalanine-arginine β-naphthylamide) that served as a positive control. The OD600 and fluorescence curves were recorded for 2 h with 75 s delays between readings and 2.5 min reading intervals. Fluorescence reading was performed from the top of the wells using excitation and emission filters of 355 nm and 460 nm, respectively. To estimate changes in efflux activity, we used a 2 step process: (1) we measured the optical-density-normalized fluorescence signal over a fixed time frame (from 7.5 min to 120 min) to monitor the intracellular accumulation of a fluorescent probe, and (2) we calculated the change in normalized fluorescence signal by dividing the signal at the final time point (120 min) by that at the initial time point (7.5 min). Relative efflux activity of the tested strains was determined by normalizing the reached raw values to those of their respective ancestral strains and taking its inverse.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Illumina reads and Nanopore contigs for this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB63210 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB63210). Additional source data underlying the figures featured in the Supplementary Notes are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data underlying Figs. 1–5 and Extended Data Figs. 1–10 are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The authors declare that all data cleaning and analysis associated with this article were performed using previously published methods, the applications of which are appropriately cited in the corresponding sections in the Methods. No custom code was developed for the aforementioned purposes. Additional code underlying the figures featured are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Miethke, M. et al. Towards the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 726–749 (2021).