Abstract

In monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides, time-reversal symmetry—combined with broken space-inversion symmetry—defines the spin–valley degree of freedom. As such, the engineering and control of time-reversal symmetry by optical or magnetic fields constitutes the foundation of valleytronics. Here we propose a new approach for the detection of broken time-reversal symmetry and valley imbalance in monolayer WSe2 based on second-harmonic generation. At room temperature, our method can selectively probe a net valley imbalance generated by ultrafast, coherent and valley-exclusive optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert effects. This work demonstrates the potential and unique capabilities of nonlinear optics as a probe of broken time-reversal symmetry as well as a tool for ultrafast and non-destructive valleytronic operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Time-reversal symmetry (TRS) E↑(k) = E↓(−k) underlies some of the most exotic phases of condensed matter1. In monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), the interplay between broken space inversion E↑(k) ≠ E↑(−k) and TRS further defines the spin–valley degree of freedom2,3, where direct transitions in momentum space at the ±K points of the Brillouin zone are energetically degenerate but non-equivalent. Engineering of TRS in TMDs naturally leads to the field of valleytronics, where the degeneracy of ±K valleys is lifted either by magnetic fields (Zeeman splitting)4 or with circularly polarized light. The latter approach can be further distinguished between the generation of a real exciton population in one of the valleys via one-5 or two-photon6 absorption, or by the transient breaking of TRS with coherent processes such as the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert effects7,8. In the vast majority of studies reported so far, the detection of broken TRS and the consequent valley imbalance has been limited to the realm of linear optics, mainly to the detection of a polarized photoluminescence (PL)5,9, or the detection of Kerr rotation in the pump–probe configuration to probe valley-polarized resident carriers10,11 or valley-selective coherent states7,8. Both approaches suffer from severe limitations: PL is intrinsically destructive, as it requires the recombination of the electron–hole pair and, thus, the loss of valley information, whereas optical Kerr rotation uses a relatively intense and resonant probe pulse (for example, 100 μW of average power11), which can considerably perturb the sample under investigation. Although it is possible to probe a valley imbalance at room temperature8,12, most experiments on pristine TMDs were performed at cryogenic temperatures, as a shorter exciton lifetime13 and a longer spin relaxation time14,15,16 result in a robust exciton polarization at low temperatures.

In this context, nonlinear optics (NLO) can provide distinct advantages. An all-optical probe of broken TRS based on NLO has been realized in layered17 and bulk18 magnets, as well as in various non-magnetic TMDs under the effect of an external magnetic field19. Very recently, ultrafast and room-temperature nonlinear valleytronics has been realized in centrosymmetric materials based on light–matter interactions with engineered topological optical fields20,21. In addition, a few theoretical22,23,24 and experimental12,25,26 studies have recently demonstrated the advantages of a detection scheme based on second-harmonic generation (SHG). All these studies were based on the measurement of a rotation in the second-harmonic (SH) polarization ellipse and simultaneously writing the valley state with an elliptically polarized fundamental beam (FB)12,25,26. On one hand, this approach clearly surpasses the standard methods based on polarized PL and optical Kerr rotation, because SHG is a parametric process and, thus, ultrafast and non-destructive, especially under the condition in which the SH signal at 2ω is resonant with the exciton transition under investigation. Therefore, the TMD is fully transparent to the FB at ω. On the other hand, the detection of the valley imbalance based on elliptical SHG fails if the polarization of the FB approaches the circular state, because, in this case, there is no well-defined ellipse rotation to measure.

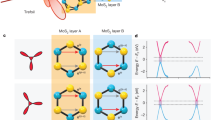

In this work, we experimentally and theoretically study SHG in monolayer WSe2 excited by linearly versus circularly polarized light, and we demonstrate that their ratio can be used as a simple and powerful probe of valley imbalance and broken TRS. Our theoretical model is based on the semiconductor Bloch equations (SBE)27,28,29,30, which we solve both analytically31 and numerically in the two scenarios where TRS is either preserved (excitation with linearly polarized light) or broken (excitation with circularly polarized light). Broken TRS is included in the model Hamiltonian of monolayer WSe2 as a valley-selective and intensity-dependent perturbation arising from the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts7,8. For a linear FB, the shift in the optical gap is valley symmetric, and thus, TRS is preserved. By contrast, circular excitation leads to valley-exclusive gap opening and TRS breaking, which is reflected in a characteristic modification of the NLO susceptibility. We highlight that our results can provide new insights for understanding previous experiments12, in which the impact and strength of the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert effects can be estimated by considering the energy difference between the fundamental photon energy and the optical gap of the material under investigation. Finally, a key ingredient of our theory and experiments is the observation that some elements of the NLO susceptibility in monolayer TMDs are proportional to the valley index τ = ±1, a property that we define as the ‘nonlinear valley selection rule’. On the basis of this, we demonstrate that the different polarizations in our SH experiments effectively probe different wave-vector groups32, and thus, they are subject to different symmetry operations. In particular, SHG with linearly polarized light simultaneously probes both ±K valleys, leading to a cancellation of the terms in the NLO susceptibility that are proportional to τ (Fig. 1a). This leads to a NLO susceptibility that is typical of the D3h point group, corresponding to the wave-vector group at the Γ point of the Brillouin zone for monolayer TMDs. By contrast, SHG with circularly polarized light selectively probes only one of the ±K valleys, and thus, it measures the corresponding C3h wave-vector group (Fig. 1b).

a, A linearly polarized FB (left, red) can be decomposed into right- and left-circular components that interact with the ±K valleys, respectively, emitting counter-rotating SH beams. Since the \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}\) elements (grey) of the NLO susceptibility cancel out in the two valleys, only the \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}\) terms (light green) contribute to the emitted signal, which add up again to a linearly polarized SH (right, light green). b, A right-circularly polarized FB (left, red) interacts only with the +K valley, and thus, it probes both \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}\) and \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}\). Coherent superposition of the two contributions from the +K valley results in circularly polarized SH (right, dark green).

Crystal symmetry and nonlinear valley selection rules

The vast majority of NLO experiments on TMDs33, such as the measurements of crystal orientation34, number of layers35, strain36 and ultrafast switching37,38, are based on the assumption that monolayers belong to the D3h point group. However, a closer look shows that the point group (or more precisely the wave-vector group39) is D3h only at the Γ point of the Brillouin zone, whereas it is C3h at the ±K points40. Thus, resonant excitation of the valleys must be described by the nonlinear elements of the cyclic C3h tensor, rather than those of the dihedral D3h group. The elements of the second-order susceptibility χ(2) for the C3h point group can be divided into two sub-groups41, namely, \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{xyy}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{yyx}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{yxy}^{(2)}\) and \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{yxx}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{xxy}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{xyx}^{(2)}\), where x (y) refers to the armchair (zig-zag) axis of the crystal in the case of TMDs. The first subset (\({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}\)) is identical to the D3h point group and these elements can fully describe SHG in TMDs in the case of non-resonant excitation (for example, below-gap virtual states), and thus, they represent the crystal (that is, geometrical and intrinsic) response of TMDs. By contrast, the second subset (\({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}\)) appears only in the C3h group and must be taken into account in the case of resonant excitation at ±K. To show this, we use analytical expressions of the χ(2) tensor31 derived from the perturbative solutions of SBEs. In the SBE framework, a monolayer TMD is described by a Hamiltonian, and we use the simplified TMD two-band model valid close to ±K (ref. 42):

with the on-site energy Δ, effective hopping γ and

where κα = a(kα − Kα) is the dimensionless wave vector measured with respect to ±K, a is the TMD lattice constant, τ = ±1 is the valley index and ζ is the prefactor of the trigonal warping term, responsible for space inversion breaking. From h1(k), we calculate the second-order susceptibility contribution from each valley τ as (Supplementary Section 2.2.3)

where \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}(\tau )=-{\chi }_{xyy}^{(2)}(\tau )=-{\chi }_{yyx}^{(2)}(\tau )=-{\chi }_{yxy}^{(2)}(\tau )\) and \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}(\tau )=-{\chi }_{yxx}^{(2)}(\tau )\)\(=-{\chi }_{xxy}^{(2)}(\tau )=-{\chi }_{xyx}^{(2)}(\tau )\). Here \(C=\frac{\tilde{C}q}{2\varDelta -{\rm{i}}/{T}_{2}-2\omega }\) accounts for the usual resonance condition (Supplementary Section 2.2.3). Note that throughout this work, we use the convention of ℏ = 1. We highlight that \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}(\tau )\) is linear in τ, and thus, it disappears when simultaneously probing both valleys, namely, when the FB is linearly polarized (Fig. 1a). In this condition, the second-order polarization is given as follows.

We stress that in equation (6), only the valley-summed susceptibilities \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{xyy}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{yyx}^{(2)}=-{\chi }_{yxy}^{(2)}=2{\chi }_{0}^{(2)}\) survive, leading to the typical second-order tensor of the D3h point group41 and in agreement with the vast majority of reports on SHG in monolayer TMDs33,34,35,36,37. This feature is even captured by our numerical simulations (Supplementary Section 2). In addition, from equations (3) and (4), we stress that (1) \({\chi }_{0}^{(2)}\) is directly proportional to the trigonal warping prefactor ζ; (2) the \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}(\tau )\) and \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}(\tau )\) terms of the NLO susceptibility are phase shifted by π/2 at ±K.

If we now move to the circular basis and re-calculate the ±K-resolved NLO susceptibility (Supplementary Section 2.2.4), we obtain

whereas \({\chi }_{---}^{(2)}\) and \({\chi }_{+++}^{(2)}\) vanish. Here the subscripts ± refer to the helicity of SH polarization and FB. In contrast to the linear case, for circularly polarized SH and FB, the contributions from the ±K valleys towards \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}\) no longer cancel out (Fig. 1b), and the second-order polarization reads

In other words, since circularly polarized light selectively probes the valleys, the NLO susceptibility is described by the C3h wave-vector group41. In analogy with linear optics, we label the τ proportionality of \({\chi }_{yyy}^{(2)}\) as the nonlinear valley selection rule, and we stress that this is fundamentally different compared with the selection rules for circularly polarized light based on the conservation of angular momentum43,44,45. The conservation of angular momentum is naturally included in our model in the fact that the elements \({\chi }_{+++}^{(2)}={\chi }_{---}^{(2)}=0\) and \({\chi }_{-++}^{(2)}={\chi }_{+--}^{(2)}\ne 0\), namely, the observation that a σ± FB generates a σ∓ SH.

Finally, we highlight that as long as TRS is preserved, the ratio between the intensities for circularly polarized versus linearly polarized SH is exactly 2, as one can immediately observe by taking the intensity I ∝ ∣P∣2 from equations (6) and (9).

TRS breaking in TMDs by off-resonant excitation

We now include TRS breaking into our model Hamiltonian. We do this by considering the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts8, namely, by adding an energy shift \(\Delta {E}_{\tau ,\sigma }=\frac{| {d}_{vc}{| }^{2}{{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}}{2\varDelta +\sigma \tau \omega }\), where we have defined the helicity parameter σ = ±1 of the off-resonant FB; the dipole moment ∣dvc∣, which is identical at the ±K valley; the FB electric-field strength \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\); and FB frequency ω. Note that the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts are valley exclusive7,8: for instance, a σ = − 1 FB leads to an optical Stark shift of \(\Delta {E}_{+1,-1}=\frac{| {d}_{vc}{| }^{2}{{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}}{2\varDelta -\omega }=\Delta {E}_{{\rm{OS}}}\) in +K and, simultaneously, to a Bloch–Siegert shift of \(\Delta {E}_{-1,-1}=\frac{| {d}_{vc}{| }^{2}{{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}}{2\varDelta +\omega }=\Delta {E}_{{\rm{BS}}}\) in −K. In the framework of perturbative NLO, the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert effects can also be regarded as a higher-order nonlinear contribution to the emission at the SH photon energy. Thus, the Hamiltonian for broken TRS reads

The optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert effects shift the bandgap (diagonal elements in equation (10)) of the material8,46, whereas we do not expect them to change the effective mass of the material (off-diagonal term in equation (10)). We can now calculate the elements of the NLO susceptibility with optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts starting from the model Hamiltonian (equation (10)) (Supplementary Section 2.2.5):

where 1/T2 is the dephasing rate and we have defined the detuning δω = ω − E0/2 using the A1s exciton resonance energy E0. Here we observe that \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}\) is again identical in both valleys (τ = ±1), and thus, TRS is preserved (Fig. 2a). Therefore, the second-order polarization for a linearly polarized FB becomes

which is, again, the typical expression of the SH for a crystal with D3h symmetry. Finally, we calculate the elements of the NLO susceptibility for circularly polarized light (Supplementary Section 2.2.5), namely, the case in which the gap opening is asymmetric in the two valleys, and thus, TRS is broken (Fig. 2b):

a, A linearly polarized FB opens the gap in both valleys by the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts, interacting equally with the +K and −K valleys. This preserves TRS, namely, E↑(+K) = E↓(−K). b, A right-circularly polarized FB opens different gaps by the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts in the +K and −K valleys, respectively, leading to the breaking of TRS: E↑(+K) ≠ E↓(−K).

From this, we derive again the SH polarization as

On the basis of equations (11), (12) and (14), TRS breaking can be measured by looking at the ratio η of the SH intensity in the two cases of circular and linear FB polarization:

assuming an equal intensity of incident linearly and circularly polarized FB: \(| {I}_{0}^{{\rm{lin}}}(\omega )| =| {I}_{0}^{{\rm{circ}}}(\omega )|\). If we consider the Taylor expansion of equation (16) up to the first order in \({I}_{0}\propto {{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}\), we obtain

where \({\delta }_{{\rm{OS}}/{\rm{BS}}}=\frac{\Delta {E}_{{\rm{OS}}/{\rm{BS}}}}{(2\delta \omega +{\rm{i}}/{T}_{2})}\) (Supplementary Section 2.2.5). As expected, the ratio η depends on the energy difference (δOS − δBS) between the ±K valleys, and it tends to 2 if TRS is preserved (that is, in the absence of the valley-asymmetric gap opening). Furthermore, we highlight the dependence \(\eta \propto \,\text{Re}\,\left(\frac{1}{2\delta \omega +{\rm{i}}/{T}_{2}}\right)\), which results in a derivative-like shape when crossing the A1s exciton resonance, as we will show later in our experiments. In addition, η depends on the material parameters (for example, the dipole moment dvc and dephasing time T2) and experimental parameters (such as the electric-field strength of the FB \({{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}\) and detuning δω). Therefore, even though the effect is enhanced at resonance (δω→0), it is possible to observe broken TRS even for off-resonant SHG, whereas the ratio η→2 is only far from resonance, namely, when δω→∞.

Experimental and analytical results

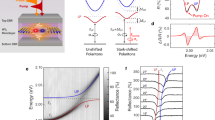

To demonstrate the features discussed in the previous section, we perform SH experiments at different wavelengths (SH signal at 690–820 nm, corresponding to an FB in the range of 1,380–1,640 nm) and scan across the A1s exciton resonance of a monolayer WSe2 sample (Methods provides details on the sample fabrication). First, we performed differential reflectivity ΔR/R and PL (Fig. 3a), Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 3b) and SH power dependence (Fig. 3c) measurements to confirm the monolayer nature of our sample. One prominent feature arising from the A exciton is observed in the ΔR/R value. The PL emission is plotted in the same figure for comparison with ΔR/R, and it shows a negligible Stokes shift, indicating the absence of contribution from localized defect states in the material47. The Raman spectrum (Fig. 3b) shows the spectrally overlapping E′ and A1′ modes and the second-order 2LA mode. The distance between the two peaks of approximately 11 cm−1 is typical of a WSe2 monolayer48. Finally, the SH power dependence (Fig. 3c) recorded for an FB of 1,500 nm shows a slope (in log–log scale) of ~2, as expected for SHG. A more detailed analysis of the SH power dependence will be discussed below.

a, Comparison of PL (orange, right y axis in 103 counts per second (kcps)) and ΔR/R (black, left y axis). b, Raman spectrum showing the characteristic E', A1' and 2LA modes. c, Double-logarithmic plot of the SH intensity (black squares) versus the FB power. The linear fit (red dotted line) shows a slope of 1.95. d, Experimental setup with the half-wave plate (HWP) and quarter-wave plate (QWP) to control the polarization state of the FB (ω, orange). The emitted SH is filtered (F) and detected by a silicon avalanche photodiode (APD). NA, numerical aperture. e, Normalized total emitted SH as a function of the ellipticity of the FB for SH wavelengths of 720 nm (green triangles), 750 nm (red circles) and 780 nm (black squares).

To measure the broken TRS from the ratio η, we tune the ellipticity of the FB (from linear to circular) and detect the total SH intensity (Fig. 3d and Methods provide details on the experimental setup). Figure 3e shows the ellipticity-dependent measurements for three selected wavelengths: at resonance (750 nm) and away from the resonance (780 nm and 720 nm) with respect to the A1s exciton of our sample. Here the FB power is kept constant at 6 mW. The curves are normalized (that is, we set the SH intensity to 1 for linear excitation) and we paid particular attention to remove any possible contribution from two-photon PL (Supplementary Section 4), which could alter the ratio of the circular/linear SH intensity. Clearly, this ratio is highly dispersive and can dramatically differ from 2 (that is, the ratio expected when TRS is preserved), particularly in the case of resonant SHG. To further highlight this point, in Fig. 4a, we plot the wavelength dependence of η (black squares) on top of the linear PL measured on the same sample (orange curve). This ratio displays values both above and below 2 (horizontal dashed line) in correspondence with the exciton transition. Furthermore, we point out that the ratio η has a clear ‘derivative shape’ across the A1s exciton resonance, which arises from the \(\frac{1}{\delta \omega }\) dependence of equation (16)/(17). It is worth noting that the ratio η is approximately 2 close to zero detuning (δω ≈ 0), even though this wavelength falls in the resonant region in which TRS is broken. We argue that in this case, the fingerprint of broken TRS can be found in the phase difference (Δϕ) between \({\chi }_{xxx}^{(2)}\) and \({\chi }_{+--}^{(2)}\). Our experimental results are in good agreement with the dispersion of the ratio η obtained from our analytical model (16), as plotted in Fig. 4b for dephasing times of T2 = 100 fs, 250 fs and 500 fs and an FB power of 6.5 mW (Supplementary Section 2.2.5). We observe that the depicted data fall within a range of dephasing time of 100–250 fs, which is in excellent agreement with the expected value of dephasing time at room temperature from electron–phonon scattering at the ±K points49. Finally, we stress that the influence of the dephasing time T2 is a direct consequence of considering a monochromatic field within our theoretical model.

a, PL (orange curve) superimposed onto the SH ratio η (black closed circles, left y axis) for an excitation power of 6 mW, and to the slope of η (red open circles, right y axis) for different wavelengths across the exciton resonance. b, Comparison of the analytically calculated wavelength dependence of η from equation (16) (excitation power of 6.5 mW and dephasing times T2 = 100 fs, 250 fs and 500 fs, with ∣dvc∣ = 6 eÅ and Δ = E0/2 = 0.83 eV) and the experimental data from a (black closed circles). c, Power dependence of η for SH wavelengths of 720 nm (green triangles), 750 nm (black squares) and 800 nm (red circles).

In addition, Fig. 4c shows the power dependence of η for three example SH wavelengths (720 nm, 750 nm and 800 nm). The SH ratio η tends to 2 when the FB power tends to 0, namely, when TRS is preserved in the absence of an external perturbation. Moreover, the ratio η shows a linear power dependence with respect to the FB, in agreement with our analytical results from equation (17). This linear power dependence is a natural consequence of the fact that TRS is broken by the coherent optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert effects. Figure 4a also shows the slope of η (red open circles), obtained from a linear fit of all the wavelengths investigated in our experiments (Supplementary Fig. 5), displaying exactly the same derivative shape of the ratio η at a fixed FB power.

Finally, we highlight that with our analytical model, we can estimate the optical Stark (στ = −1) and Bloch–Siegert (στ = 1) shifts as \(\Delta {E}_{\tau ,\sigma }=\frac{| {d}_{vc}{| }^{2}{{\mathcal{E}}}_{0}^{2}}{2\varDelta +\sigma \tau \omega }\) using the parameters shown in Fig. 4. For an excitation wavelength of 1,500 nm, we obtain a gap opening of 17 meV and 6 meV from the optical Stark and Bloch–Siegert shifts, respectively. On rescaling by the input power and detuning, these values are in reasonable agreement with previously reported values7,8 (Supplementary Section 3). Thus, the agreement between experiments and theory (without any fitting parameter) demonstrates the capability of our detection scheme to quantitatively measure broken TRS in monolayer TMDs.

Discussion

We established a new method based on circular SHG to probe the valley degree of freedom in TMDs, and more generally, to probe broken TRS in crystals belonging to the D3h point group. We demonstrate that the NLO response of TMD monolayers must be interpreted looking at the wave-vector group, rather than the point group. Furthermore, with our analytical model, we clarify the origin of the different wave-vector groups that describe circular and linear excitations, and attribute this difference to the nonlinear valley selection rule. Finally, we analytically derive and experimentally show that the coherent and off-resonant optical Stark effect and Bloch–Siegert shift break TRS, and their effects can be measured by simply looking at the ratio η between the SH intensities emitted from circularly and linearly polarized FBs. Building on this, our approach can be used as a powerful detection scheme for valleytronic operations. This could be done, for instance, by selecting the SH wavelength with the largest slope of η as a function of power. Subsequently, TRS can be controlled with external knobs, such as the valley Zeeman splitting using magnetic fields50 or by generating a net valley polarization using one-photon absorption with circularly polarized light51. Finally, the broken TRS can be measured with our method by looking at the changes in the ratio η with and without the presence of external perturbations. Thus, this work demonstrates the unique capabilities of NLO as an ultrafast and non-invasive probe of broken TRS and of the valley degree of freedom in TMDs.

Methods

Fabrication of bulk crystals

The synthesis of WSe2 was performed by chemical vapour transport in a quartz glass ampoule from tungsten (99.999%; 100 mesh, China Rhenium) and selenium (99.9999%, granules of 1–6 mm, Wuhan Xinrong New Material) in stochiometric amounts corresponding to 100 g WSe2. In addition, excess of 2 at.% selenium, 0.5 g SeCl4 (99.9%, rough crystalline powder, Strem) and 0.5 g iodine (99.9%, granules, Fisher Scientific) were added in a glove box to the ampoule (50 × 250 mm2; wall thickness, 3 mm) and the ampoule was sealed by an oxygen–hydrogen welding torch under a high vacuum (under 1 × 10−3 Pa) using a diffusion pump with a liquid-nitrogen trap. The sealed ampoule was first placed in a muffle furnace and heated to 500 °C for 25 h, 600 °C for 50 h and finally 800 °C for 50 h. The heating and cooling rates were 1 °C min−1. The ampoule with the formed WSe2 powder was placed in a two-zone horizontal furnace. First, the growth zone was heated to 1,000 °C and the source zone, to 800 °C. After 2 days, the thermal gradient was reversed, as the source zone was kept at 1,000 °C, whereas the growth zone was kept at 900 °C for 10 days. During cooling, the thermal gradient was reversed for 2 h, to remove the transport medium and volatile compounds. The ampoule was opened in an argon-filled glove box.

Sample preparation and characterization

We mechanically exfoliate a monolayer of WSe2 from a bulk crystal onto polydimethylsiloxane and transfer it onto a transparent fused silica substrate. The monolayer nature of our sample is confirmed by optical PL, Raman and SHG measurements (Fig. 3a–c).

Polarization-resolved SHG

For the SHG measurements, we use a custom-made multiphoton microscope, which we operate in the transmission geometry (Fig. 3d). The FB is generated by an optical parametric oscillator (Levante IR fs from APE), pumped by the output of an Yb-doped mode-locked laser (FLINT FL2-12, LIGHT CONVERSION) with a repetition rate of 76 MHz and a pulse length of ~100 fs. This allows tuning the FB from 1,300 nm to 2,000 nm. Before entering the microscope, a combination of half-wave plate (AHWP05M-1600, Thorlabs) and quarter-wave plate (#46-562, Edmund Optics), both mounted on motorized rotation mounts (RSP05/M, Thorlabs), allows us to fully control the polarization state of the FB. Subsequently, the FB is focused onto the sample by a ×40 objective (LMM-40X-P01, Thorlabs) and the transmitted FB as well as the generated SH are collimated by a lens (C330TMD, Thorlabs). The transmitted FB is blocked by a shortpass filter (FESH0950, Thorlabs) and the SH is spectrally filtered by bandpass filters. Finally, we detect the SH with a silicon avalanche photodiode (APD440A, Thorlabs) and lock-in amplifier (HF2LI, Zurich Instruments).

Differential reflectivity and PL

Room-temperature differential reflectivity (ΔR/R) measurements are performed using a custom-built confocal microscope. A halogen lamp with a stabilized power supply serves as the white light source for reflectivity, focused on a pinhole that is imaged on the sample. The reflected light is then dispersed in a spectrometer and detected by a Si charge-coupled device camera. The excitation/detection spot diameter is approximately 1 μm, smaller than the typical size of the monolayers. Differential reflectivity is defined as (Rsub − Rsam)/Rsub, where Rsam represents the intensity reflection coefficient of the sample with the WSe2 monolayers and Rsub denotes the same structure without WSe2. The PL experiments are conducted on the same areas of the monolayer using the same custom-built confocal microscope and a 633 nm He–Ne laser as the excitation source.

Numerical methods

We simulated the SHG using the SBEs27,28,29,30. The material data are calculated using a two-band tight-binding model52 fitted to the density functional theory band structure of WSe2 in the vicinity of the ±K points of the Brillouin zone. Further details are provided in Supplementary Section 2.1.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sato, M. & Ando, Y. Topological superconductors: a review. Rep. Progr. Phys. 80, 076501 (2017).

Liu, G.-B., Xiao, D., Yao, Y., Xu, X. & Yao, W. Electronic structures and theoretical modelling of two-dimensional group-VIB transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2643–2663 (2015).

Vitale, S. A. et al. Valleytronics: opportunities, challenges, and paths forward. Small 14, 1801483 (2018).

MacNeill, D. et al. Breaking of valley degeneracy by magnetic field in monolayer MoSe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 037401 (2015).

Mak, K. F., He, K., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Control of valley polarization in monolayer MoS2 by optical helicity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 494–498 (2012).

Wang, G. et al. Giant enhancement of the optical second-harmonic emission of WSe2 monolayers by laser excitation at exciton resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 097403 (2015).

Kim, J. et al. Ultrafast generation of pseudo-magnetic field for valley excitons in WSe2 monolayers. Science 346, 1205–1208 (2014).

Sie, E. J. et al. Large, valley-exclusive Bloch-Siegert shift in monolayer WS2. Science 355, 1066–1069 (2017).

Zeng, H., Dai, J., Yao, W., Xiao, D. & Cui, X. Valley polarization in MoS2 monolayers by optical pumping. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 490–493 (2012).

Yang, L. et al. Long-lived nanosecond spin relaxation and spin coherence of electrons in monolayer MoS2 and WS2. Nat. Phys. 11, 830–834 (2015).

Hsu, W.-T. et al. Optically initialized robust valley-polarized holes in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Commun. 6, 8963 (2015).

Herrmann, P. et al. Nonlinear all-optical coherent generation and read-out of valleys in atomically thin semiconductors. Small 19, 2301126 (2023).

Lagarde, D. et al. Carrier and polarization dynamics in monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 047401 (2014).

Paradisanos, I. et al. Prominent room temperature valley polarization in WS2/graphene heterostructures grown by chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 203102 (2020).

Glazov, M. M. et al. Spin and valley dynamics of excitons in transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Phys. Status Solidi B 252, 2349–2362 (2015).

Wang, Z. et al. Intravalley spin–flip relaxation dynamics in single-layer WS2. Nano Lett. 18, 6882–6891 (2018).

Sun, Z. et al. Giant nonreciprocal second-harmonic generation from antiferromagnetic bilayer CrI3. Nature 572, 497–501 (2019).

Fiebig, M., Fröhlich, D., Krichevtsov, B. & Pisarev, R. V. Second harmonic generation and magnetic-dipole-electric-dipole interference in antiferromagnetic Cr2O3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 2127 (1994).

Wu, S. et al. Extrinsic nonlinear Kerr rotation in topological materials under a magnetic field. ACS Nano 17, 18905–18913 (2023).

Mitra, S. et al. Light-wave-controlled Haldane model in monolayer hexagonal boron nitride. Nature 628, 752–757 (2024).

Tyulnev, I. et al. Valleytronics in bulk MoS2 with a topologic optical field. Nature 628, 746–751 (2024).

Wehling, T. O., Huber, A., Lichtenstein, A. I. & Katsnelson, M. I. Probing of valley polarization in graphene via optical second-harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. B 91, 041404 (2015).

Cheng, J. et al. Chiral selection rules for multi-photon processes in two-dimensional honeycomb materials. Opt. Lett. 44, 2141–2144 (2019).

Hipolito, F. & Pereira, V. M. Second harmonic spectroscopy to optically detect valley polarization in 2D materials. 2D Mater. 4, 021027 (2017).

Ho, Y. W. et al. Measuring valley polarization in two-dimensional materials with second-harmonic spectroscopy. ACS Photonics 7, 925–931 (2020).

Mouchliadis, L. et al. Probing valley population imbalance in transition metal dichalcogenides via temperature-dependent second harmonic generation imaging. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 5, 6 (2021).

Schmitt-Rink, S., Chemla, D. S. & Haug, H. Nonequilibrium theory of the optical Stark effect and spectral hole burning in semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 37, 941–955 (1988).

Lindberg, M. & Koch, S. W. Effective Bloch equations for semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 38, 3342–3350 (1988).

Wilhelm, J. et al. Semiconductor Bloch-equations formalism: derivation and application to high-harmonic generation from Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. B 103, 125419 (2021).

Yue, L. & Gaarde, M. B. Introduction to theory of high-harmonic generation in solids: tutorial. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 39, 535–555 (2022).

Aversa, C. & Sipe, J. E. Nonlinear optical susceptibilities of semiconductors: results with a length-gauge analysis. Phys. Rev. B 52, 14636–14645 (1995).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chirality logic gates. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq8246 (2022).

Dogadov, O., Trovatello, C., Yao, B., Soavi, G. & Cerullo, G. Parametric nonlinear optics with layered materials and related heterostructures. Laser Photonics Rev. 16, 2100726 (2022).

Malard, L. M., Alencar, T. V., Barboza, A. P. M., Mak, K. F. & de Paula, A. M. Observation of intense second harmonic generation from MoS2 atomic crystals. Phys. Rev. B 87, 201401 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Probing symmetry properties of few-layer MoS2 and h-BN by optical second-harmonic generation. Nano Lett. 13, 3329–3333 (2013).

Mennel, L. et al. Optical imaging of strain in two-dimensional crystals. Nat. Commun. 9, 516 (2018).

Klimmer, S. et al. All-optical polarization and amplitude modulation of second-harmonic generation in atomically thin semiconductors. Nat. Photonics 15, 837–842 (2021).

Sinelnik, A. et al. Ultrafast all-optical second harmonic wavefront shaping. Nat. Commun. 15, 2507 (2024).

Dresselhaus, M., Dresselhaus, G. & Jorio, A. Group Theory: Application to the Physics of Condensed Matter (Springer, 2007).

Fajardo, E. & Winkler, R. Effective dynamics of two-dimensional bloch electrons in external fields derived from symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 100, 125301 (2019).

Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear Optics (Academic Press, 2020).

Taghizadeh, A. & Pedersen, T. G. Nonlinear optical selection rules of excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 99, 235433 (2019).

Bloembergen, N. Conservation laws in nonlinear optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 70, 1429–1436 (1980).

Simon, H. J. & Bloembergen, N. Second-harmonic light generation in crystals with natural optical activity. Phys. Rev. 171, 1104–1114 (1968).

Tang, C. L. & Rabin, H. Selection rules for circularly polarized waves in nonlinear optics. Phys. Rev. B 3, 4025–4034 (1971).

Slobodeniuk, A. O. et al. Ultrafast valley-selective coherent optical manipulation with excitons in WSe2 and MoS2 monolayers. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 7, 17 (2023).

Paradisanos, I. et al. Efficient phonon cascades in WSe2 monolayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 538 (2021).

Sahin, H. et al. Anomalous Raman spectra and thickness-dependent electronic properties of WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 165409 (2013).

Korolev, V. et al. Unveiling the role of electron-phonon scattering in dephasing high-order harmonics in solids. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.12929v1 (2024).

Srivastava, A. et al. Valley Zeeman effect in elementary optical excitations of monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 11, 141–147 (2015).

Ye, Z., Sun, D. & Heinz, T. F. Optical manipulation of valley pseudospin. Nat. Phys. 13, 26–29 (2017).

Chacón, A. et al. Circular dichroism in higher-order harmonic generation: heralding topological phases and transitions in chern insulators. Phys. Rev. B 102, 134115 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank X. Zambrana-Puyalto, Z. Fedorova, I. Staude and L. Greten for insightful discussions on the concepts of chirality and valleys in TMDs. This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (CRC 1375 NOA), project number 398816777 (subproject C4); the International Research Training Group (IRTG) 2675 ‘Meta-Active’, project number 437527638 (subproject A4); and the Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF) project number 16KIS1792 SiNNER. Z.S. was supported by ERC-CZ program (project LL2101) from the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MEYS) and by the project Advanced Functional Nanorobots (reg. No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/15_003/0000444 financed by the EFRR). J.W. acknowledges the DFG for funding via the Emmy Noether Programme (project number 503985532), CRC 1277 (project number 314695032, subproject A03) and RTG 2905 (project number 502572516).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.H. and G.S. conceived the experiments. P.H., S.K. and T.W. performed the NLO experiments and analysed the data. P.H. and S.K. prepared the monolayer sample by mechanical exfoliation. I.P. performed the linear optical characterization of the sample. T.L. performed the numerical simulations. J.W. developed the theoretical analytical model based on the SBE and supervised the numerical simulations. A.P., K.M. and Z.S. provided the bulk crystals. I.P., D.K., J.W. and G.S. interpreted the experimental and theoretical results. P.H., J.W. and G.S. wrote the manuscript, with contributions from all authors. All authors participated in the discussion and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Photonics thanks Yi Wei Ho, Hongyuan Li, Zhipei Sun and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–6 and Figs. 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Herrmann, P., Klimmer, S., Lettau, T. et al. Nonlinear valley selection rules and all-optical probe of broken time-reversal symmetry in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Photon. 19, 300–306 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01591-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01591-z

This article is cited by

-

Encoding and manipulating ultrafast coherent valleytronic information with lightwaves

Nature Photonics (2026)

-

Measurement of optically induced broken time-reversal symmetry in atomically thin crystals

Nature Photonics (2025)

-

Photonics in Flatland: challenges and opportunities for nanophotonics with 2D semiconductors

npj Nanophotonics (2025)