Abstract

High-harmonic generation has been driving the development of attosecond science and sources. More recently, high-harmonic generation in solids has been adopted by other communities as a method to study material properties. However, so far high-harmonic generation has only been driven by classical light, despite theoretical proposals to do so with quantum states of light. Here we observe non-perturbative high-harmonic generation in solids driven by a macroscopic quantum state of light, a bright squeezed vacuum, which we generate in a single spatiotemporal mode. The process driven by a bright squeezed vacuum is considerably more efficient in the generation of high harmonics than classical light of the same mean intensity. Due to its broad photon-number distribution, covering states from 0 to 2 × 1013 photons per pulse, and strong subcycle electric field fluctuations, a bright squeezed vacuum gives access to free carrier dynamics within a much broader range of peak intensities than accessible with classical light.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

High-harmonic generation (HHG) lies at the foundation of attosecond science, extreme nonlinear optics and an increasing number of applications1,2,3. Initially observed on irradiating gases1,2,3,4 with intense ultrashort near-infrared pulses, nowadays harmonics are generated also from liquids5,6 and solids7,8,9, using pump lasers with wavelengths spanning from the far infrared to the ultraviolet (UV)10,11,12. This non-perturbative process has applications for sources delivering high-photon-energy radiation reaching beyond the X-ray water window4,13,14, and for creation of attosecond light pulses15,16. By leveraging its intrinsic subcycle nature, HHG is now being exploited to observe charge dynamics in matter at unprecedentedly short timescales, providing radically new and powerful tools for studying phenomena such as multi-electron correlations, phase transitions and topological effects17,18,19,20. As a result, over the past decade, HHG in solids has been used for a wide range of studies such as all-optical energy band structure retrieval8,21, extreme UV spectroscopy22,23,24, laser picoscopy of the valence electron structure25, investigations of quantum phase transitions26 and Berry phases27.

Despite the wide range of experimental conditions under which it has been observed and its many applications, HHG has been described mainly in semiclassical terms. A precise description of HHG depends on the quantum properties of matter (for example, solid crystals or gas molecules). However, the intense light field driving HHG is usually considered to be classical. Meanwhile, recent works have revealed quantum-optical features of the high harmonics28,29,30,31 and of their driving field following their generation32,33,34. Still, all these works deal with the HHG from classical (coherent) pulses of light. The use of quantum light for driving HHG has been considered theoretically35,36 but not realized, since HHG requires intensities of the order of 1 TW cm−2, or photon numbers of about 1013, in a pulse of just tens of femtoseconds or shorter. Such extreme conditions have remained so far inaccessible for quantum-state engineering. Indeed, quantum states of light produced in quantum optics typically contain only a few photons per mode. Macroscopic quantum states can be obtained by adding a strong coherent component to a squeezed vacuum37 or to a single photon38,39, but even in this case most of the energy is contained in the classical part40.

An exception is a bright squeezed vacuum (BSV), a macroscopic quantum state of light generated at the output of a strongly pumped unseeded optical parametric amplifier. A BSV is a quantum superposition of even-photon-number states extending to high photon numbers. Recent experiments have achieved BSV pulses with mean photon number 〈N〉 as high as 1013 (refs. 41,42), and with a photon-number probability distribution so broad that photon numbers exceeding the mean by a factor of 6 or more occurred with 2% probability. This feature is in striking contrast with the photon-number distribution of classical (coherent-state) light, whose width is as small as \({\Delta {N}} = {\sqrt {{{\langle N\rangle }}}}\) (the shot-noise limit). This implies that for classical light with \({{{\langle N\rangle }}}={10^{13}}\) the probability of an event exceeding the mean by a factor of 6 or more is \({\sim }1{0}^{-1{0}^{13}}\).

In addition, a BSV has been shown to manifest non-classical features such as sub-shot-noise photon-number correlations43 and polarization entanglement44. It was also predicted to enhance subcycle sensing of quantum optical fields45. The broad photon-number probability distribution of a BSV leads to superbunching46: its intensity correlation function of order n, defined as \({g}_{\mathrm{BSV}}^{(n)}\equiv \langle :{N}^{n}:\rangle /{\langle N\;\rangle }^{n}\), is (2n − 1)!!. Thermal light, considered as classical stochastic light with photon-number statistics close to those of a BSV, has lower values of correlation functions \({g}_{\mathrm{th}}^{(n)}=n!\). Superbunching enhances multiphoton effects, such as perturbative harmonic generation41 or nonlinear electron emission from nanotips47, and also results in the non-Poissonian sidebands of the non-perturbative harmonics48.

All these properties suggest that a BSV is an intriguing and interesting alternative driver for the harmonics, providing a new route to combine strong-field physics and quantum optics, exploring new phenomena accessible only with quantum light and, possibly, enhancing HHG. Recently, these prospects have triggered theoretical works proposing applications of a BSV in strong-field physics, predicting an extended plateau for HHG35, modification of electron dynamics36,49, HHG selection rules50 and quadrature squeezing in the extreme UV spectral range51.

In this work we report the observation of HHG driven by quantum light. We generate a single-mode BSV with unprecedented peak powers and demonstrate BSV-driven high harmonics from solids, and show that, compared with classical light, a BSV enhances the harmonic yield, revealing a boost of multiphoton processes. These experimental results are supported by numerical investigations, which extend BSV-driven HHG simulations in gases28,35 to solids and show that these can reproduce the main trend. Furthermore, we show that the sparse nature of BSV light provides a simple and convenient route for suppressing sample damage, enabling the probing of electron dynamics in solids in a previously inaccessible regime.

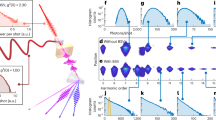

In contrast to a bright classical light pulse, which has a well-defined amplitude of the electric field with very weak fluctuations (Fig. 1a), the mean electric field of the BSV remains zero at all times, while its variance oscillates at twice the light frequency (Fig. 1b)52,53. This feature indicates strong quantum fluctuations of the field on a subcycle timescale. As a result, while classical light can drive electrons and quasiparticles with only a well-defined quasimomentum k at the time, BSV pulses can excite and drive quasiparticles in a coherent superposition of quasimomentum states, similar to the BSV-driven dynamics of free and bound electrons shown in ref. 49. Further, these electron quantum paths may interfere to modify the harmonic emission. We illustrate the difference between the two cases in (Fig. 1c,d) by depicting BSV-excited quasiparticles moving simultaneously in opposite directions (Fig. 1d).

a, The electric field of a coherent pulse exhibits a mean value oscillating at the optical frequency and a constant variance. b, The electric field of a BSV pulse: the mean value is constantly zero, while the variance oscillates at twice the carrier frequency. c, HHG by coherent light in a semiconductor in the interband mechanism. An electron–hole pair emerges via perturbative (multiphoton) or non-perturbative excitation, is accelerated by the electric field, gaining energy, and finally recombines, emitting high-energy photons. d, HHG by a BSV in a semiconductor. Due to the extremely large uncertainty of the BSV field during half a cycle, the HHG is driven by a continuum of paths for electron–hole pairs. ke, electron quasimomentum; Ee, electron energy.

Accordingly, within half of the optical cycle, the electron–hole pairs can be driven to spread all over the energy bands, emitting a broad spectrum of harmonic radiation. The large variance of the BSV drive also implies that each pulse has a Keldysh parameter54 with a large uncertainty, thus affecting the competition between multiphoton and tunnelling excitation.

Spectra of harmonics driven by quantum light

We compare HHG from solid targets driven by ultrashort pulses of classical coherent and quantum light. Both pulses are centred at 1.6 μm (0.77 eV), with the former having a duration of 70 fs full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) and the latter of 25 fs (FWHM) (Extended Data Fig. 1a). The repetition rate of both sources is 1 kHz. As targets, we use 6-μm-thick x-cut Mg:LiNbO3 (LN) and 1-μm-thick amorphous silicon (a-Si), observing emission of harmonics up to the seventh order—limited by the detection sensitivity.

Using LN, we generate both odd and even harmonics (Fig. 2a), due to the non-centrosymmetric crystal structure. The photon energies of the second to fifth harmonics from LN are below the direct bandgap (4.2 eV, ref. 55), and those of the sixth and seventh harmonics are above the direct bandgap (Fig. 2a). Despite the shorter duration, which results in broader but lower-power harmonics (longer pulses carry higher energies and thus generate harmonics with higher photon numbers despite the slightly worse conversion efficiency56), the BSV-generated fourth to seventh harmonics show at least 5–15 times higher yield than the same harmonics driven by coherent pulses with identical mean intensity (2 TW cm−2). We stress that we still observe the enhancement when the two pumps are more similar in duration (Supplementary Fig. 2).

a, Lower panel: the spectrum of harmonics generated in a 6 μm x-cut doped LN crystal by a BSV (solid line) and by coherent radiation (dashed line). The photon energies of the sixth and the seventh harmonics exceed the direct energy bandgap of doped LN. a.u., arbitrary units. Upper panel: harmonic yield enhancement factor for a BSV versus coherent pump for the same mean intensity (~2 TW cm−2). We show experimental (solid-edged bars) and simulated (dashed-edged bars) factors. b,c, Joint photon-number probability distribution of the input pump (b, coherent radiation; c, BSV) and the sixth harmonic for two different mean pump photon numbers (red and black). In the case of the coherent pump the joint photon-number distribution is Gaussian, while the photon statistics in the BSV case show non-trivial features. \(N_{{n\omega},\, {\mathrm{total}}}^{({\mathrm{bsv}})}\), total photon number of the nth harmonic, generated by BSV; \(N_{{n\omega},\, {\mathrm{total}}}^{({\mathrm{coh}})}\), total photon number of the nth harmonic, generated by coherent punp; Nnω, nth harmonic photon number; \({{\langle N_{\omega}\rangle}}\), mean photon number of the pump; \({{{\langle N\rangle }}}\), same as \({\langle {N_{\omega}}\rangle}\); \(\langle {N_{{6}{\omega}}}\rangle\), mean photon number of the 6th harmonic.

Simulations based on the semiconductor Bloch equations using the band structure of LN57 and accounting for the BSV photon statistics show a similar behaviour: an overall increase of the enhancement up to the fifth harmonic and a lower enhancement for sixth and seventh harmonics (Fig. 2a, Methods and Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, simulations (Supplementary Fig. 5) predict that, using a BSV, the high-energy cutoff extends to around 7.5 eV (165 nm), well beyond the spectral range covered by our detection scheme (extending down to 200 nm). The numerical analysis, discussed further in ‘Numerical simulation’, is based on the incoherent summation of semiclassical contributions. For this reason, any enhancements present in the analysis are derived from the photon statistics of the BSV rather than electron path interference. This effect exists for both perturbative41 and non-perturbative emission to different degrees.

Besides measuring the mean value of the harmonic yield, we also study the joint photon-number statistics between the input pump light and the harmonic radiation. For this purpose, we measure the shot-to-shot input light intensity and the resulting harmonic intensities (Methods). Figure 2b,c shows the measured two-dimensional photon-number distributions between the pump and the sixth harmonic from LN in the case of the coherent pump (Fig. 2b) and BSV pump (Fig. 2c) for two different mean photon numbers (red and black points). The photon-number probability distribution for classical light is narrow and Gaussian, centred at the mean photon number 〈Nω〉. The photon-number probability distribution of the harmonic is also Gaussian with the mean photon number 〈N6ω〉 (Fig. 2b). The increase of the pump’s mean photon number shifts the centre of the joint probability distribution without considerably changing its width. The measurement of the mean photon number is thus sufficient to find the harmonic yield 〈N6ω〉/〈Nω〉, but obtaining the power scaling requires a systematic scan of the pump mean photon number.

As opposed to coherent radiation, a BSV has a broad photon-number distribution with its maximum at zero photon number. The photon-number distribution of the harmonic is non-trivial and differs from that of the driving pulses but it inherits the large width; moreover, there is a correlation between the BSV photon number and the harmonic photon number (Fig. 2c). As a result, the large variance of the BSV photon number reveals the entire power dependence through a single joint probability distribution measurement. In other words, a scan of the mean photon number of the BSV excitation is not required, underscored by the fact that both low and high BSV settings (red versus black in Fig. 2c) can reveal the power dependence within the dynamic range of the detectors for the pump (undepleted) and the harmonic.

Additionally, within a single optical cycle of a BSV, the superposition of its photon-number states is mapped to the quasimomentum of an electron, whose wavefunction is therefore distributed over the whole energy band. This implies that the joint photon-number distribution between the BSV and its harmonic, which results from the electron–hole recombination, contains information about a large part of the (or even the entire) sample band structure and electron dynamics.

Power scaling of the high harmonics

In Fig. 3, we show the yield of the fourth to seventh harmonics generated by pumping LN with classical light (top row) and BSV light (bottom row) measured for each laser shot and the corresponding simulations. At low pump intensities, the power of harmonics with frequencies below the direct bandgap (fourth and fifth) scales with power equal to the harmonic order, typical of the perturbative regime. As the intensity increases, the scaling changes and becomes non-perturbative. When using the classical pump, deviations from the perturbative scaling can be observed at intensities above 1 TW cm−2 (Fig. 3a,b).

a–h, Power scaling of the fourth to seventh harmonics generated in x-cut LN using coherent radiation (a–d) and a BSV (e–h). Solid lines: mean photon number of the harmonics, with the shading indicating the photon-number uncertainty. Dotted lines: numerical simulation. Dashed lines: power-law fit. For coherent light excitation, the range above 3 TW cm−2 is inaccessible because of the sample damage.

In contrast, the same harmonics generated using a BSV exhibit a perturbative power scaling over a broader range of intensities and a deviation from it at around 2 TW cm−2. The yield of the sixth and seventh harmonics (with frequencies above the direct bandgap) follows a non-perturbative power scaling over the whole intensity range with both coherent and BSV pumps, but with some differences (Fig. 3c,d,g,h). The classical-light-generated harmonics scale with a fixed exponent, but the yield changes with intensity when generating the harmonics with BSV light. While at low intensities the sixth harmonic power scales with comparable exponents (~3) for the two pumps, we observe two different exponents for the seventh harmonic: 2.0 with coherent and 3.4 with BSV. Above 1.5 TW cm−2, the scaling exhibits two plateaus, especially pronounced for the fourth and seventh harmonics, probably originating from quantum path interference of short and long trajectories generated in the HHG process58. These features are visible only in the case of the BSV pump, due to its possibility of ‘non-invasive’ testing. Numerical simulations can reproduce our experimental results fairly well for both classical and BSV excitations (Fig. 3 and Methods). At low pump intensities (below ~2 TW cm−2) and for the fourth to sixth harmonics, the agreement between experimental data and simulations is excellent. However, the two depart from each other as the intensity increases, and for the seventh harmonic in general. We attribute these deviations to the simplified band-structure model, where we only take into account a single conduction band (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 4).

The differences in the power scaling of harmonics driven by a BSV and by classical light become even more striking when we replace LN with a-Si, which has a lower direct bandgap (in the range between 1.5 eV and 2 eV). Because of the amorphous material structure, only odd harmonics can be generated from this sample. Figure 4 shows the (shot-to-shot) power scaling of the above-bandgap fifth and seventh harmonics generated using classical radiation and a BSV in a-Si. Under coherent-state irradiation of the sample, we observe a non-perturbative scaling of the photon number for both harmonics: \({N_{{5\omega}}}\propto{N_{{\omega}}^{2.8}}\), \({N_{{7\omega}}}\propto{N_{{\omega}}^{2.7}}\). However, when using a BSV, we obtain a different scaling. The yield of the fifth harmonic initially scales with the fifth power of the pump photon number, \({N_{{5\omega}}}\propto{N_{{\omega}}^{5}}\), indicating a perturbative scaling, and then saturates at pump intensities above ~2 TW cm−2.

a–d, Power scaling of the fifth and seventh harmonics generated in a-Si using coherent radiation (a,b) and a BSV (c,d). Solid lines: mean photon number of harmonics, with the shading showing the photon-number uncertainty. For coherent light excitation, the range above 2 TW cm−2 is inaccessible because of the sample damage.

Although the yield of the BSV-generated seventh harmonic already shows the non-perturbative scaling as a sign of the tunnelling scenario, its exponent is larger than in the case of the coherent pump, which points to a possible competition between the seven-photon multiphoton process and the non-perturbative regime of HHG.

We attribute the differences in the power scaling of the two types of light to the superbunched photon statistics of the BSV, which leads to the enhancement of n-photon processes by a factor of \({g}_{\mathrm{BSV}}^{(n)}\), compared with coherent-state (classical) light41. This enhancement offers an explanation for the broader intensity range over which the harmonic yield follows a perturbative scaling as well as the higher exponent of the BSV-generated seventh harmonic at low pump intensities. Furthermore, this interpretation also explains the lower statistical enhancement of the harmonics generated above the direct bandgap when compared with the fifth harmonic (Fig. 2a). A power scaling with an exponent around 3 leads to an enhancement by only a factor of \({g}_{\mathrm{BSV}}^{(3)}=15\), instead of \({g}_{\mathrm{BSV}}^{(6)}=10{\mathrm{,}}395\), which we would expect for the sixth harmonic in the perturbative regime.

Another feature of HHG driven by a BSV is the saturation of the yield, which we attribute to the strong depletion of the valence-band population. Remarkably, this is not observed in the case of the coherent-state pump due to the optical damage of the sample.

Discussion

The harmonic power scalings obtained with both samples show that using a BSV we generate harmonics over a wide range of pump intensities extending beyond 10 TW cm−2 without causing optical damage. On the other hand, with coherent light considerably lower pump intensities (~2 TW cm−2) can induce damage in the samples. Such a striking difference cannot be entirely explained by the longer duration of the coherent pulses and is mostly a consequence of the diverse photon distribution of the two pulses. In fact, in dielectrics (including LN59) for the considered durations the intensity at which damage occurs differs by at most twofold59,60,61,62.

Under coherent light irradiation, each pulse contains a well-defined number of photons, which will cause optical damage to the sample above a certain threshold. In contrast, BSV pulses possess a broad photon-number distribution, implying that each pulse contains an uncertain number of photons, with the mean value far below the damage threshold. The large-photon-number events in the tail of the distribution, however, can drive HHG and probe the material without damaging it within a single laser shot or multiple laser shots. Often, continuous irradiation of the sample within temporal intervals shorter than its relaxation time can result in optical damage to the sample. The BSV photon-number distribution also implies a longer temporal interval between intense events, thus effectively providing the sample with sufficient time to relax to its initial state.

Additional experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1) reveal that by decreasing the laser repetition rate the sample damage threshold increases, and we can generate high harmonics using brighter classical light. However, covering an intensity range comparable to that of a BSV requires reducing the repetition rate to the hertz level, increasing substantially the already longer acquisition time. The observation indicates that opportunely modulating the shot-to-shot power of a coherent source would allow using it for HHG and acquiring data within times and intensity ranges comparable to those achieved with a BSV. However, this would come at the cost of increasing complexity, especially for sources of few-cycle pulses operating at high repetition rates. On the other hand, the natural sparsity of a BSV provides an alternative and more powerful route to using optical modulators to study the interaction of intense light with matter, allowing, in a fashion similar to sparse sampling, the collection of sufficient data within a short time (minutes using a 1 kHz repetition rate pump laser) without damaging the solid sample or adding any experimental complexity.

Thus, the excitation of a material is more gentle with a BSV than with coherent light. It enables the study of solid-state samples in extreme regimes, such as the harmonic yield saturation in a-Si (Fig. 4c,d), which can be related to the creation of an electron–hole plasma63,64.

Conclusion and outlook

In conclusion, our observation of non-perturbative HHG driven by a BSV demonstrates that experiments with quantum light are now able to access the strong-field regime of optics. A BSV enables a strong enhancement of solid-state HHG when compared with coherent light and allows for the observation of electron–hole dynamics beyond the conventional damage threshold. The approach we developed may become a new spectroscopic tool based on photon-number statistics, heralding the emergence of extreme nonlinear quantum spectroscopy. Our BSV source can also attain sufficient intensities to drive HHG in gases, liquids and wide-bandgap solids, reaching the extreme UV spectral regime, and we expect that it can also be employed for controlling HHG, based on subcycle quantum noise engineering, in a similar fashion to control through subcycle field engineering65,66.

In the future, the giant uncertainty of the BSV’s electric field magnitude and the massive number of photon pairs contained in each BSV pulse will find use in the observation of quantum interference effects and of many-body correlations in solids, with applications in quantum state engineering. Finally, since HHG occurs on subcycle timescales, it goes beyond conventional descriptions of single-mode quantum optics, which are insufficient over such short temporal spans. Our findings will further stimulate discussions in this direction and expand the realm of quantum and extreme nonlinear optics to new uncharted territories.

Methods

Experimental set-up

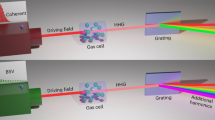

Extended Data Fig. 1a shows a sketch of our experimental set-up for HHG in solids. For comparison, we use two linearly polarized pump sources delivering (1) coherent pulses and (2) BSV pulses, both centred at 1,600 nm. As a pump laser for both sources, we use a titanium sapphire amplifier laser system (Coherent Legend) with a central wavelength of 800 nm, 45 fs FWHM pulse duration and a repetition rate of 1 kHz. Combining this laser with a femtosecond optical parametric amplifier (Light Conversion, TOPAS Prime), we obtain coherent pulses with a duration of 70 fs FWHM.

In a parallel set-up, after reducing the pump laser beam diameter to 3 mm (1/e2), we generate a BSV in a 3-mm-thick β-barium borate crystal cut for type I collinear frequency-degenerate phase matching via high-gain parametric downconversion. Here the β-barium borate crystal is tuned out of the exact phase matching to reduce the frequency bandwidth of the BSV, so that the BSV becomes single-mode temporally. However, at this stage, BSV pulses still contain around 150 spatial modes. To make it single mode also spatially, we reflect both the BSV and the pump back into the same crystal with a plane silver mirror placed at a distance of 75 cm from the crystal. Back at the β-barium borate, only the BSV spatial mode with the lowest diffraction (for example, the fundamental mode) overlaps highly with the pump beam and undergoes phase-sensitive amplification, while all the higher-order modes diffract faster without being further amplified67. After the amplification, the BSV pulses exhibit a spectral bandwidth of 150 nm centred around 1.6 μm. We separate them from the residual 800 nm light using a shortpass dichroic mirror (Thorlabs DMSP1180) and two longpass filters (Thorlabs FELH1000).

To characterize the temporal profile of the coherent and BSV pulses, and thus determine the actual intensity of the light irradiating the sample, we use a home-built device for second-harmonic frequency-resolved optical gating (FROG). The retrieved FROG traces reveal that both pulses are almost transform limited with a duration of 70 fs FWHM for the coherent pulses and 25 fs FWHM for the BSV pulses. The measured FROG trace of the latter is shown in Extended Data Fig. 1c.

Extended Data Fig. 1b displays the photon-number distribution of a BSV measured with a fast InGaAs photodiode (Thorlabs PDA20C2) without spatial or spectral filtering. The data are well fitted with a theoretical single-mode distribution41 (black line), with a mean number of photons per pulse of 2 × 1012 (dashed vertical line), confirming that the BSV is single-mode. The distribution stretches up to photon numbers of 2 × 1013, corresponding to pulse energies of 9 μJ.

For HHG, either the BSV or the coherent-state radiation is focused into a 30 μm spot (diameter at 1/e2) on the sample with a silver off-axis parabolic mirror (Edmund Optics, focal length f = 25.4 mm) to drive HHG. The spot size has been determined from a knife-edge measurement for both sources. We use two samples: an x-cut 6 μm Mg:LN crystal on a 1 mm fused silica substrate and a 1 μm a-Si layer on a 1 mm fused silica substrate. We mount the samples so that the substrate faces the pump pulses. Because fused silica has a much higher bandgap, it does not contribute to the outcome of the HHG measurement. After the samples, the harmonics and the pump light are collimated by a UV-enhanced aluminium off-axis parabolic mirror (Thorlabs MPD119-F01, f = 25.4 mm) and sent to a MgF2 prism. After this, the harmonics are focused by a UV-enhanced aluminium spherical mirror (Thorlabs CM254-250-F01) to different positions.

We detect the fourth to seventh harmonics separately using a fast UV-enhanced silicon avalanche photodiode (Thorlabs APD440A2) by rotating the spherical mirror within a range of 1°. Additionally, we place bandpass filters for the fourth harmonic (Thorlabs FBH400-40), the fifth harmonic (Edmund Optics 12094, BP325/50) and the sixth harmonic (Edmund Optics 39313, BP266/10), and also an iris (1 mm opening), in front of the detector to reduce the contribution of the scattered light. We acquire 200,000 single-shot records of driver pulses (classical or BSV) and each harmonic synchronously.

Numerical simulation

To simulate and elucidate our experimental findings, we utilize the semiconductor Bloch equations68 to describe the interaction of classical (Glauber coherent) light with LN along Γ–Z:

Here P(k, t) represents a dimensionless polarization depending on the time t and the quasimomentum k. \({f}_{\;\mathrm{e(h)}}(k,t)\) denotes the population of electrons and holes in the conduction and valence bands, respectively. The energy–momentum relations for the conduction band ϵc(k) and the valence band ϵv(k), as well as the transition dipole moment d(k), are derived from density functional theory calculations57, with some modifications. Most importantly, we set the bandgap manually to 4.2 eV, corresponding to the direct bandgap of doped LN, which is the relevant gap for the HHG process. The exact band structure and transition dipole moments are plotted in Supplementary Information.

To eliminate multiple recollision interferences and maintain the pronounced harmonic structure in our one-dimensional simulation, we set the phenomenological decoherence time to half of the optical cycle duration of the pump laser, T2 = 0.5Tpump. Extending the decoherence time to one optical cycle Tpump does not notably alter our results. In general, a longer decoherence time exceeding a few cycles allows electrons to return over durations longer than a laser cycle, leading to unphysical anharmonic photon emission, whereas a shorter decoherence time less than a quarter cycle, 0.25Tpump, may strongly suppress long trajectories.

Considering LN’s ferroelectric nature, we account for the spontaneous polarization effect, which breaks the material’s symmetry and allows for even-order harmonics generation (see ref. 57 and Supplementary Information for more details). The HHG spectrum for a coherent pump is computed as

where

and

denote, respectively, the interband and intraband contributions to the HHG yield, and \({{\nu}_n}(k)={\nabla_k}{\epsilon_n}{(k)}\) represents the group velocity of the electrons.

To calculate the BSV-driven HHG spectrum underlying the enhancement plot (Fig. 2a), we apply the novel method developed in ref. 35, in which the driving field is decomposed into coherent contributions using the Husimi Q function. The emission spectrum for each coherent contribution is calculated using the semiconductor Bloch equations (equations (1) and (2)), after which the spectra are incoherently integrated over using the initial Q function. The Husimi Q function for the BSV is given by

Here ϵα is the electric field amplitude for coherent parameter α, and \(\bar{\epsilon }\) the mean value of the absolute field amplitude of the BSV. ϵα is taken to be real along the direction of antisqueezing, and the distribution is integrated over the axis of squeezing in advance, so that the distribution in equation (6) is one dimensional. This is justified, as the squeezed axis of the Husimi distribution is infinitely narrow in terms of the electric field amplitude, and hence does not contribute to the spectrum.

The BSV-driven HHG spectrum is then obtained by incoherently integrating the coherent HHG spectra with the Q-function distribution35:

where \({S}_{{\rm{HHG}}}^{{\rm{coh}}}(\omega ,{\epsilon }_{\alpha })\) is the emission spectrum driven by a coherent pump with peak electric field ϵα, as calculated in equation (3). Due to the incoherent summation, we do not consider the coupling of dephasing effects in the material and the BSV; hence we use the same decoherence time in all calculations.

While this method was developed for atomic HHG, all approximations and calculations in ref. 35 apply to any system in which the equations of motion are linear in the density matrix or state vector. As the semiconductor Bloch equations are derived from the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, this requirement holds for our calculations as well.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ferray, M. et al. Multiple-harmonic conversion of 1064 nm radiation in rare gases. J. Phys. B 21, L31–L35 (1988).

McPherson, A. et al. Studies of multiphoton production of vacuum-ultraviolet radiation in the rare gases. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 4, 595–601 (1987).

Krausz, F. & Ivanov, M. Attosecond physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 163–234 (2009).

Popmintchev, T. et al. Bright coherent ultrahigh harmonics in the keV X-ray regime from mid-infrared femtosecond lasers. Science 336, 1287–1291 (2012).

Luu, T. T. et al. Extreme-ultraviolet high-harmonic generation in liquids. Nat. Commun. 9, 3723 (2018).

Mondal, A. et al. High-harmonic generation in liquids with few-cycle pulses: effect of laser-pulse duration on the cut-off energy. Opt. Express 31, 34348–34361 (2023).

Ghimire, S. et al. Observation of high-order harmonic generation in a bulk crystal. Nat. Phys. 7, 138–141 (2011).

Vampa, G. et al. All-optical reconstruction of crystal band structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 193603 (2015).

Goulielmakis, E. & Brabec, T. High harmonic generation in condensed matter. Nat. Photon. 16, 411–421 (2022).

Ganeev, R. A., Elouga Bom, L. B. & Ozaki, T. High-order harmonic generation from plasma plume pumped by 400 nm wavelength laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 131104 (2007).

Popmintchev, D. et al. Ultraviolet surprise: efficient soft X-ray high-harmonic generation in multiply ionized plasmas. Science 350, 1225–1231 (2015).

Marceau, C., Hammond, T. J., Naumov, A. Y., Corkum, P. B. & Villeneuve, D. M. Wavelength scaling of high harmonic generation for 267 nm, 400 nm and 800 nm driving laser pulses. J. Phys. Commun. 1, 015009 (2017).

Teichmann, S. M., Silva, F., Cousin, S. L., Hemmer, M. & Biegert, J. 0.5-keV soft X-ray attosecond continua. Nat. Commun. 7, 11493 (2016).

Cousin, S. L. et al. High-flux table-top soft X-ray source driven by sub-2-cycle, CEP stable, 1.85-μm 1-kHz pulses for carbon K-edge spectroscopy. Opt. Lett. 39, 5383–5386 (2014).

Paul, P. M. et al. Observation of a train of attosecond pulses from high harmonic generation. Science 292, 1689–1692 (2001).

Hentschel, M. et al. Attosecond metrology. Nature 414, 509–513 (2001).

Imai, S., Ono, A. & Ishihara, S. High harmonic generation in a correlated electron system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 157404 (2020).

Schmid, C. P. et al. Tunable non-integer high-harmonic generation in a topological insulator. Nature 593, 385–390 (2021).

Heide, C. et al. Probing topological phase transitions using high-harmonic generation. Nat. Photon. 16, 620–624 (2022).

Shao, C. et al. High-harmonic generation approaching the quantum critical point of strongly correlated systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 047401 (2022).

Hohenleutner, M. et al. Real-time observation of interfering crystal electrons in high-harmonic generation. Nature 523, 572–575 (2015).

Tzallas, P., Skantzakis, E., Nikolopoulos, L. A. A., Tsakiris, G. D. & Charalambidis, D. Extreme-ultraviolet pump–probe studies of one-femtosecond-scale electron dynamics. Nat. Phys. 7, 781–784 (2011).

Luu, T. T. et al. Extreme ultraviolet high-harmonic spectroscopy of solids. Nature 521, 498–502 (2015).

Nisoli, M., Decleva, P., Calegari, F., Palacios, A. & Martín, F. Attosecond electron dynamics in molecules. Chem. Rev. 117, 10760–10825 (2017).

Lakhotia, H. et al. Laser picoscopy of valence electrons in solids. Nature 583, 55–59 (2020).

Alcalà, J. et al. High-harmonic spectroscopy of quantum phase transitions in a high-Tc superconductor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2207766119 (2022).

Uzan-Narovlansky, A. J. et al. Observation of interband Berry phase in laser-driven crystals. Nature 626, 66–71 (2024).

Gorlach, A., Neufeld, O., Rivera, N., Cohen, O. & Kaminer, I. The quantum-optical nature of high harmonic generation. Nat. Commun. 11, 4598 (2020).

Sloan, J. et al. Entangling extreme ultraviolet photons through strong field pair generation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.16466 (2023).

Yi, S., Babushkin, I., Smirnova, O. & Ivanov, M. Generation of massively entangled bright states of light during harmonic generation in resonant media. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.02817 (2024).

Stammer, P. et al. Entanglement and squeezing of the optical field modes in high harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 143603 (2024).

Tsatrafyllis, N., Kominis, I. K., Gonoskov, I. A. & Tzallas, P. High-order harmonics measured by the photon statistics of the infrared driving-field exiting the atomic medium. Nat. Commun. 8, 15170 (2017).

Tsatrafyllis, N. et al. Quantum optical signatures in a strong laser pulse after interaction with semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 193602 (2019).

Lewenstein, M. et al. Generation of optical Schrödinger cat states in intense laser–matter interactions. Nat. Phys. 17, 1104–1108 (2021).

Gorlach, A. et al. High-harmonic generation driven by quantum light. Nat. Phys. 19, 1689–1696 (2023).

Even Tzur, M. et al. Photon-statistics force in ultrafast electron dynamics. Nat. Photon. 17, 501–509 (2023).

Vahlbruch, H., Mehmet, M., Danzmann, K. & Schnabel, R. Detection of 15 dB squeezed states of light and their application for the absolute calibration of photoelectric quantum efficiency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 110801 (2016).

Bruno, N. et al. Displacement of entanglement back and forth between the micro and macro domains. Nat. Phys. 9, 545–548 (2013).

Lvovsky, A. I., Ghobadi, R., Chandra, A., Prasad, A. S. & Simon, C. Observation of micro–macro entanglement of light. Nat. Phys. 9, 541–544 (2013).

Laghaout, A., Neergaard-Nielsen, J. S. & Andersen, U. L. Assessments of macroscopicity for quantum optical states. Opt. Commun. 337, 96–101 (2015).

Spasibko, K. Y. et al. Multiphoton effects enhanced due to ultrafast photon-number fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 223603 (2017).

Manceau, M., Spasibko, K. Y., Leuchs, G., Filip, R. & Chekhova, M. V. Indefinite-mean Pareto photon distribution from amplified quantum noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 123606 (2019).

Finger, M. A., Iskhakov, T. S., Joly, N. Y., Chekhova, M. V. & Russell, P. S. J. Raman-free, noble-gas-filled photonic-crystal fiber source for ultrafast, very bright twin-beam squeezed vacuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 143602 (2015).

Iskhakov, T. S., Agafonov, I. N., Chekhova, M. V. & Leuchs, G. Polarization-entangled light pulses of 105 photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 150502 (2012).

Virally, S., Cusson, P. & Seletskiy, D. V. Enhanced electro-optic sampling with quantum probes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 270504 (2021).

Iskhakov, T. S., Pérez, A. M., Spasibko, K. Y., Chekhova, M. V. & Leuchs, G. Superbunched bright squeezed vacuum state. Opt. Lett. 37, 1919–1921 (2012).

Heimerl, J. et al. Multiphoton electron emission with non-classical light. Nat. Phys. 20, 945–950 (2024).

Lemieux, S. et al. Photon bunching in high-harmonic emission controlled by quantum light. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.05474 (2024).

Even Tzur, M. & Cohen, O. Motion of charged particles in bright squeezed vacuum. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 41 (2024).

Hegazi, A., Tzur, M. E. & Cohen, O. Quantum state of high harmonics driven by quantum light: dynamical symmetries and selection rules. In 9th International Conference on Attosecond Science and Technology (2023).

Tzur, M. E. et al. Generation of squeezed high-order harmonics. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033079 (2024).

Riek, C. et al. Direct sampling of electric-field vacuum fluctuations. Science 350, 420–423 (2015).

Riek, C. et al. Subcycle quantum electrodynamics. Nature 541, 376–379 (2017).

Keldysh, L. V. Ionization in the field of a strong electromagnetic wave. Sov. Phys. JETP 20, 1307–1314 (1965).

Kase, S. & Ohi, K. Optical absorption and interband Faraday rotation in LiTaO3 and LiNbO3. Ferroelectrics 8, 419–420 (1974).

Weissenbilder, R. et al. How to optimize high-order harmonic generation in gases. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 713–722 (2022).

Shao, T.-J., Hu, F. & Chen, H.-B. Spontaneous polarization effects on solid high harmonic generation in ferroelectric lithium niobate crystals. J. Phys. B 54, 245402 (2021).

Kim, Y. W. et al. Spectral interference in high harmonic generation from solids. ACS Photon. 6, 851–857 (2019).

Meng, Q., Zhang, B., Zhong, S. & Zhu, L. Damage threshold of lithium niobate crystal under single and multiple femtosecond laser pulses: theoretical and experimental study. Appl. Phys. A 122, 582 (2016).

Tien, A.-C., Backus, S., Kapteyn, H., Murnane, M. & Mourou, G. Short-pulse laser damage in transparent materials as a function of pulse duration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 3883–3886 (1999).

Chimier, B. et al. Damage and ablation thresholds of fused-silica in femtosecond regime. Phys. Rev. B 84, 094104 (2011).

Mao, S. et al. Dynamics of femtosecond laser interactions with dielectrics. Appl. Phys. A 79, 1695–1709 (2004).

Sokolowski-Tinten, K. & von der Linde, D. Generation of dense electron–hole plasmas in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 61, 2643–2650 (2000).

Sirotin, M. A. et al. Direct ultrafast carrier imaging in a perovskite microlaser with optical coherence microscopy. Optica 10, 1322–1330 (2023).

Kira, M. & Koch, S. W. Spectroscopy and Quantum-Optical Correlations 457–479 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Kira, M., Koch, S. W., Smith, R. P., Hunter, A. E. & Cundiff, S. T. Quantum spectroscopy with Schrödinger-cat states. Nat. Phys. 7, 799–804 (2011).

Pérez, A. M. et al. Bright squeezed-vacuum source with 1.1 spatial mode. Opt. Lett. 39, 2403–2406 (2014).

Luu, T. T. & Wörner, H. J. High-order harmonic generation in solids: a unifying approach. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115164 (2016).

Acknowledgements

F.T., M.C. and A.R. thank P. St.J. Russell for supporting the project and M. Butryn for technical support of the laser system. We thank M. Even Tzur and M. Ivanov for discussions. A.R. thanks P. Cusson for help with the FROG measurement, I. Soward for help in the first stage of the experiment and M. Sirotin for discussions. A.R. acknowledges funding from the International Max Planck Research School for Physics of Light. D.S. acknowledges partial support by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Programme under agreement 101070700 (project MIRAQLS). Z.C., M.B., O.C., I.K. and M.K. thank the Helen Diller Quantum Center for partial financial support. F.T. acknowledges partial financial support from EIC Pathfinder 101046424—TwistedNano.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. and F.T. conceived the project, supervised the work and acquired the funding. A.R., F.T. and M.C. designed the experiment. A.R. carried out the experiment under the supervision of M.C., F.T. and D.S. Z.C. and M.B. developed the theory and carried out the numerical simulations under the supervision of M.K., I.K. and O.C. A.R., M.C., D.S., M.K. and F.T. wrote the article. All authors contributed to discussions and the interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks Shambhu Ghimire and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Experimental setup and characterization of bright squeezed vacuum.

(a) Experimental setup for HHG by coherent radiation and BSV. (b) Photon-number distribution of BSV. The solid line is a theoretical fit, which corresponds to single-mode BSV, the only fitting parameter being the mean photon number (dashed line). (c) Measured averaged FROG trace of BSV.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–6 and Discussion.

Supplementary Data 1

Pump power scan for sixth harmonic for determination of damage threshold.

Supplementary Data 2

Spectra of classical pump and a BSV, spectra of harmonics and efficiency of generation.

Supplementary Data 3

Photon number statistics for sixth harmonic generated by classical pump with different peak intensity.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Spectra of high harmonics, harmonic efficiency, photon-number statistics of harmonics.

Source Data Fig. 3

Power scalings of fourth to seventh harmonics from LN (experimental data and theoretical fitting curves).

Source Data Fig. 4

Power scalings of fifth and seventh harmonics from a-Si (experimental data and theoretical fitting curves).

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Photon number probability distribution of a BSV and fitting curve.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasputnyi, A., Chen, Z., Birk, M. et al. High-harmonic generation by a bright squeezed vacuum. Nat. Phys. 20, 1960–1965 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02659-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-024-02659-x

This article is cited by

-

Quantum light steers photoelectrons

Nature Physics (2025)

-

Photon bunching in high-harmonic emission controlled by quantum light

Nature Photonics (2025)

-

Quantum light drives electrons strongly at metal needle tips

Nature Physics (2025)

-

Attosecond quantum uncertainty dynamics and ultrafast squeezed light for quantum communication

Light: Science & Applications (2025)