Abstract

In the past few decades, advances in understanding of cancer biology have led to the development of highly effective conventional chemotherapies, targeted therapies that act on specific pathways that are critical to cancer growth, immune-based therapies, and cellular therapies such as haematopoietic cell transplantation and chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. However, the nephrotoxic effects of these therapies continue to pose substantial challenges, with many unanswered questions regarding the prevention, diagnosis and management of this nephrotoxicity. Further, a lack of consensus and precise guidance on kidney function estimation and drug dosing for patients with acute kidney disease or chronic kidney disease and for patients receiving kidney replacement therapy limits access to life-saving therapies and jeopardizes outcomes. In this Consensus Statement, we present guidance on the prevention, diagnosis and management of anticancer therapy nephrotoxicity for adult patients that was developed at the 34th Acute Disease Quality Initiative meeting, which convened an international panel of experts in nephrology, haematology, oncology, nephropathology, critical care, paediatric care and pharmacology. We also define a research agenda focused on preventing and mitigating anticancer therapy toxicity, maximizing early detection of nephrotoxicity and enabling optimal drug dosing in patients with kidney disease, with the goal of advancing cancer care and fulfilling the potential of these ground-breaking treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer incidence and care have improved substantially over the last few decades, largely due to reductions in smoking, increased cancer screening and advances in treatments such as the development of highly effective conventional chemotherapies, novel targeted agents, immunotherapies, and cellular therapies such as haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy1. Despite these advances, important challenges remain, including alarming global increases in the incidence of early-onset cancers and related mortality2.

Nearly 1 in 10 patients who receive systemic anticancer therapy experience an episode of acute kidney injury (AKI)3. Anticancer therapies are frequently linked to nephrotoxic effects that lead to dose reductions or to interruption or cessation of treatment, reducing the beneficial effects of the therapy and adversely impacting outcomes. In addition, patients with kidney disease are often ineligible for certain therapies and for clinical trials involving new treatments4,5. The field of onconephrology was created to address the growing burden of kidney disease associated with anticancer therapies and the clinical implications of reduced kidney function in patients with cancer. This subspecialty highlights the expertise needed to provide specialized nephrology care for patients with cancer and underscores the importance of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach6. Since 2010, publications in this field have increased exponentially, with many focused on defining the various nephrotoxicities associated with anticancer agents, including several important original investigations7,8,9,10. However, the prevention, diagnosis and management of anticancer therapy toxicity remain challenging. In response, the 34th Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) multidisciplinary consensus meeting was convened to develop guidance in these areas for adults and define a research agenda focused on preventing and mitigating anticancer therapy toxicity, maximizing early detection of nephrotoxicity and promoting optimal drug dosing in patients with kidney disease.

Methods

ADQI aims to provide expertise-based statements, supported by evidence where applicable and interpretation of current knowledge for use in clinical care by health-care professionals, as well as to identify evidence and knowledge gaps to establish future research priorities. The 34th ADQI consensus meeting, which took place 26–29 September, 2024, in Charlottesville, Virginia, USA, convened an international panel of experts in nephrology, haematology, oncology, nephropathology, critical care, paediatrics and pharmacology, all of whom had a shared interest in onconephrology.

The consensus meeting followed the established ADQI process and used a modified Delphi method to achieve consensus, as previously described11. Experts were invited to participate based on their publication records and divided into four working groups focusing on kidney toxicity, monitoring and management related to conventional cancer therapies; targeted cancer therapies; immune-based cancer therapies; and cellular therapies. A fifth group focused on the dosing of anticancer agents in patients with reduced kidney function, particularly when dosing data are limited.

In the pre-conference phase, each working group performed a comprehensive literature search and evidence appraisal to identify key themes. They summarized areas of consensus supported by evidence, areas with consensus but limited or no evidence, and knowledge gaps where consensus remains uncertain, ultimately generating core questions. During the meeting, the working groups iteratively developed and refined consensus statements in response to these core questions during repeated breakout sessions. Statements were presented during four successive plenary sessions involving all ADQI delegates for debate, discussion and suggested revisions. Post-conference, consensus statements were aggregated and presented to all attendees, who formally voted and approved the consensus recommendations (approval was defined as agreement of >85% of delegates). All statements were approved after one round of voting without the need for additional revisions or repeat voting.

Evaluation of kidney health before and after receipt of anticancer therapy

Consensus statements

What are the various nephrotoxicities associated with anticancer therapies?

-

The nephrotoxic manifestations associated with anticancer therapies extend beyond decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) to encompass the full spectrum of acute kidney disease (AKD), including vascular, interstitial, tubular and glomerular injuries.

-

Any of these nephrotoxic manifestations, when present for >3 months, may evolve into chronic kidney disease (CKD).

How should kidney health be assessed before and during receipt of anticancer therapies?

-

We recommend the use of a personalized kidney health assessment (KHA) to inform susceptibility to AKD, nephrotoxin stewardship, and individualized prevention and management strategies.

-

A brief KHA may be performed by any clinician caring for a patient who is receiving anticancer therapies. The KHA is a ‘living document’ that should be updated after AKD risk exposures.

-

Abnormalities in the brief KHA should prompt consideration of a more detailed assessment (detailed KHA) and nephrology consultation.

What is the standard for kidney function assessment in patients receiving anticancer therapies?

-

In patients receiving anticancer therapies, serum creatinine (SCr) values alone are not adequate for kidney function assessment. Estimated GFR (eGFR), obtained using endogenous filtration markers (SCr +/− cystatin C) and validated regression equations, should be used for initial assessment. Measurement of GFR using exogenous filtration markers is the gold standard for kidney function assessment in this population; however, this approach may not always be available in routine clinical practice or in all resource settings. The choice of eGFR versus measured GFR (mGFR) when both are available is guided by the clinical context.

-

Patients must be in a steady state (creatinine production must be equal to creatinine excretion) to use regression-based eGFR equations.

How should kidney function be monitored in patients receiving anticancer therapies?

-

A KHA should be performed before dosing of any anticancer therapy, at regular intervals when administering nephrotoxic medications and after changes in clinical status that may affect kidney function.

-

The timing of the post-exposure KHA is dependent upon the clinical context and local resources. However, a post-exposure KHA performed within an earlier time frame enables early identification of AKD and offers opportunities for improved outcomes.

-

Consideration should be given to long-term follow-up of any patient with AKD; this follow-up should include laboratory monitoring and nephrology evaluation.

How should patients receiving potentially nephrotoxic anticancer therapies be managed?

-

The KHA is followed by a personalized Kidney Health Response (KHR). The KHR is a patient-specific and context-specific plan to monitor for AKD and lower its risk or attenuate its impact.

-

Further studies are required to understand the optimal management strategies and targets in these patient populations.

Nephrotoxic manifestations associated with anticancer therapies

Anticancer therapies are associated with a wide variety of nephrotoxic manifestations that can affect all structural compartments of the kidney (Supplementary Fig. 1). Nephrotoxicity is traditionally defined as AKI and a decrease in GFR based on the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definition12. However, the term AKI does not encompass all acute kidney alterations, as these may develop over a longer period than 7 days, substantially impacting medium-term and long-term outcomes. Furthermore, the spectrum of nephrotoxic manifestations associated with anticancer agents extends beyond GFR decline, including pathologies such as tubulopathies (electrolyte and acid–base disorders), hypertension, proteinuria and endothelial injury. To encompass this broad spectrum of manifestations, we have adopted the term AKD13. We recognize that any of these manifestations of nephrotoxicity, when present for >3 months, may evolve into CKD12,13.

Establishing causality between a particular anticancer agent and nephrotoxicity is challenging, as patients with cancer often have other comorbidities and are exposed to multiple potentially nephrotoxic triggers (for example, sepsis, hypotension, antimicrobials)14. In addition, malignancy itself can affect kidney health14. As stopping an anticancer therapy may negatively impact survival, accurate establishment of causality is critical. Thus, clinicians should rule out other causes of nephrotoxicity, carefully assess the timing of therapy administration relative to AKD detection, review preclinical and clinical data that have previously characterized drug toxicity, and examine whether the mechanisms of action of the therapy are consistent with the pattern of injury.

The Kidney Health Assessment

Patients receiving anticancer agents would benefit from assessment of their baseline kidney health and their risk of AKD with the planned exposures. Recognizing that patients receive therapies in various resource contexts, we define a minimum assessment of kidney health as a history and physical examination (with assessment of any concomitant nephrotoxic exposures), measurement of SCr (and cystatin C where available) to calculate eGFR and urinalysis (Table 1). Any clinician caring for patients receiving anticancer therapies can administer this brief KHA. Abnormalities in the brief KHA should prompt consideration of more detailed assessment (a detailed KHA). When local resources allow, the detailed KHA should ideally be performed in conjunction with nephrology consultation to develop a risk mitigation and monitoring plan — the KHR (Fig. 1).

Prior to administration of nephrotoxic anticancer therapies, all patients should undergo a Kidney Health Assessment. The Kidney Health Assessment is a personalized evaluation of the kidney health of the patient and their potential risk of acute kidney disease (AKD) if exposed to the planned anticancer therapy. The Kidney Health Assessment is followed by a personalized Kidney Health Response, which is a risk mitigation and monitoring plan aimed at minimizing AKD risk, mitigating and/or managing AKD complications, avoiding further injuries, managing comorbid conditions impacted by AKD and facilitating rapid recovery.

Kidney function assessment in patients receiving anticancer agents

Endogenous markers of glomerular filtration (for example, SCr) have long been used to estimate GFR. Several assumptions exist regarding the use of SCr, including that creatinine only enters the urine via glomerular filtration and that production and excretion of creatinine are in a steady state in cases of acute illness or AKI. However, neither of these assumptions is correct, and the use of SCr to estimate GFR in patients with cancer is fraught with pitfalls15,16,17. As well as GFR, SCr is affected by factors such as age, sex, muscle mass and dietary intake of protein16,17. Furthermore, certain targeted cancer therapies (including anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitors, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and CDK6 inhibitors, mesenchymal-epithelial transition tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), and polyadenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase inhibitors) have been associated with impairment of the tubular secretion of creatinine, resulting in underestimation of GFR using SCr-based regression equations (that is, a ‘pseudo-AKI’ effect). Thus, other methods that directly measure GFR or regression equations that better address certain non-GFR determinants of SCr level must be used to accurately assess AKD risk, ensure accurate drug dosing and detect kidney dysfunction in its earliest stages.

Importantly, creatinine production and excretion in patients with cancer may not be in a steady state owing to acute illness, fluctuations in daily nutritional intake, loss of muscle mass and changes in fluid balance18. Patients must be in steady state to use regression-based eGFR equations, and inappropriate use of these equations (that is, during episodes of AKI) may prove misleading. Additionally, most eGFR equations provide values that are indexed to a ‘standard’ body-surface area (BSA) of 1.73 m2. The FDA and the EMA recommend drug dosage adaptation based on non-indexed GFR (that is, corrected for actual BSA). This approach may be most relevant for drugs dosed using equations incorporating GFR estimates (for example, carboplatin dosing using the Calvert equation) and is particularly important for patients who deviate substantially from a BSA of 1.73 m2.

The Cockcroft–Gault formula for estimating creatinine clearance has been used for kidney function assessment pertaining to drug eligibility and dosing; however, this equation has multiple concerns versus newer, validated eGFR equations. The Cockcroft–Gault equation was developed prior to standardization of SCr measurement, did not include women or Black people in its derivation cohort, and uses a weight variable that may be impacted by obesity or oedema. By contrast, newer validated eGFR equations were developed using rigorous mGFR methods with standardization of filtration marker assays and were derived and validated in cohorts that were sufficiently representative of the populations of interest.

Although also affected by some non-GFR determinants (for example, glucocorticoid use, thyroid dysfunction, adiposity, inflammation), serum cystatin C is a biomarker of kidney function that may offset some of the shortcomings of SCr19. A study that investigated the use of several eGFR equations in comparison to mGFR in 1,145 patients with haematological and solid malignancies, reported that the combined Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration serum creatinine-cystatin C (CKD-EPICr-Cys) equation provided best performance when compared with creatinine-only (CKD-EPICr) and cystatin C-only equations20. These findings corroborate a 2024 position statement from the American Society of Onconephrology that advocated for the use of CKD-EPICr-Cys in patients with cancer19,21. Accordingly, we recommend use of the CKD-EPICr-Cys equation when feasible.

Direct measurement of GFR using exogenous markers (for example, inulin, iohexol, iothalamate radionuclides) should be considered when estimating equations may not be reliable and is generally considered the ‘gold standard’19,21 (Table 1). Plasma or urinary clearance of exogenous filtration markers should be measured using standardized protocols. Some jurisdictions are establishing harmonized approaches for certain mGFR approaches such as plasma clearance of iohexol22. However, mGFR may not always be available in routine clinical practice and in all resource settings. Notably, in 2025, the FDA approved a transdermal system for measuring GFR via fluorescent detection of a novel exogenous tracer (relmapirazin)23,24. This approach offers opportunities to expand access to direct, point-of-care GFR measurement.

General monitoring guidance for patients receiving anticancer therapies

We suggest that patients have a KHA within 7 days before a planned anticancer therapy exposure that carries AKD risk. The timing of the post-exposure KHA depends on the clinical context and local resources but, in general, the KHA should occur within 1 week after exposure and at regular intervals (depending on the agent administered) to identify associated AKD. In addition, we suggest that clinicians repeat a patient’s KHA immediately after an unplanned exposure that carries AKD risk (that is, unanticipated or urgent administration of intravenous iodinated contrast, aminoglycosides, amphotericin or other nephrotoxins). The details of the KHA can be tailored to the clinical context and the judgement of the clinician. The KHA is a ‘living document’ that should be updated after AKD risk exposures. Consideration should also be given to long-term follow-up (lab monitoring, nephrology evaluation) for any patient with AKD.

Completion of the KHA is followed by the KHR, creating a plan to monitor for AKD and reduce its risk or attenuate its impact. All patients at high risk should undergo early correction or mitigation of context-specific, modifiable risk factors for AKD. Optimizing haemodynamic and volume status, avoiding additional nephrotoxic insults and ensuring proper dosing of concomitant medications remain the mainstay of primary prevention for AKD. Concurrent prophylactic strategies may also be employed for certain nephrotoxic anticancer therapies25,26,27,28. However, most anticancer agents have no clear prophylactic options, and more research is needed to create risk mitigation protocols.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy

Consensus statements

What is the epidemiology of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD?

-

Causality in cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD is well established for many drugs. However, the reported incidence and prevalence vary widely depending on the AKD criteria used and underlying patient risk factors.

What are the common risk factors for cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD?

-

Predisposing factors and intensity of exposure determine the potential impact of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD.

-

Shared risk factors across therapy types include drug dose, cumulative dose exposure (for most drugs), extremes of age, existing kidney dysfunction, volume depletion and concomitant use of select medications.

What are the mechanisms and clinical presentations of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD?

-

The mechanisms and clinical presentations of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD vary by agent. Examples include acute tubular injury (for example, associated with cisplatin or ifosfamide), crystalline nephropathy (for example, associated with methotrexate) and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) (for example, associated with gemcitabine or mitomycin C).

What measures are effective to prevent cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD?

-

It is essential that preventive strategies are personalized based on the patient’s health profile, type of cancer and specific treatment plan.

-

Volume optimization, medication dose adjustment and drug selection may reduce chemotherapy-related complications. Regular monitoring of kidney function and electrolytes, avoidance of concurrent nephrotoxins and use of appropriate protective agents are critical.

What measures are effective to treat cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD?

-

Treatment strategies may include volume optimization, correction of electrolyte and acid–base disturbances, discontinuation of other nephrotoxic agents and cessation of the anticancer therapy when indicated.

-

Specific therapies (such as rescue therapies or antidotes) may be appropriate for some anticancer drugs. Administration of these therapies is based on blood levels and severity of toxicity.

Epidemiology of and risk factors for cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD

Although many conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs are nephrotoxic, the most frequently implicated agents include methotrexate, cisplatin, ifosfamide, pemetrexed, gemcitabine and mitomycin C29. The reported incidence and prevalence of AKD vary, likely owing to differences in AKD criteria and underlying patient risk factors in different studies (Table 2).

Predisposing risk factors, intensity of exposure (dose and duration) and concomitant drugs determine the potential impact of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD. Shared risk factors across therapy types include initial dose, cumulative dose exposure, extremes of age, existing kidney dysfunction, drug pharmacology, volume depletion, concomitant use of nephrotoxic medications and drug–drug interactions8,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 (Table 2). Several cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, such as cisplatin and high-dose methotrexate, are highly nephrotoxic and the risk of nephrotoxicity correlates with inherent drug characteristics and patient factors8,25,30,31,32,39,40. For example, methotrexate may cause direct tubular injury via intratubular crystal formation, afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction and kidney inflammation40, and patient factors, such as poor volume status optimization, acidic urine, extracellular fluid collections (pleural effusions, ascites), concomitant use of drugs that inhibit tubular methotrexate secretion and reduced baseline GFR, may increase the risk of methotrexate-induced AKD25.

Individualized monitoring for cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD

Surveillance for cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD should be tailored to the specific agent and patient risk profile. For example, patients receiving high-dose methotrexate require serial testing of urine pH and measurement of circulating methotrexate drug levels at regular intervals to guide leucovorin dosing and inform appropriate glucarpidase administration9,25. Serum magnesium levels should be routinely checked in patients receiving cisplatin, as hypomagnesaemia has been identified as a risk factor for (and consequence of) cisplatin-associated AKD, and serum magnesium levels are a component of a validated risk score for predicting cisplatin-associated AKI8,27,41,42,43. Patients receiving gemcitabine should be monitored for signs and symptoms of TMA, such as oedema, hypertension, markers of haemolysis, thrombocytopaenia and proteinuria, in the appropriate clinical context37,44.

Prevention and management of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD

Personalized efforts to reduce AKD resulting from cytotoxic chemotherapy are essential. Appropriate hydration, adjustment of drug dose (modification of initial and maintenance dose) and appropriate drug selection may reduce the incidence and severity of cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD. In addition, regular kidney function monitoring and avoidance of concurrent exposure to potential nephrotoxins are recommended (Supplementary Table 1).

Specific preventive strategies may be available for certain cytotoxic chemotherapy agents. As mentioned above, urinary alkalinization is a long-established practice to prevent methotrexate crystallization and subsequent tubular injury25. Studies suggest that magnesium supplementation may help prevent or attenuate cisplatin-induced AKD26,27,41,42,43,45. However, randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm whether prophylactic administration of magnesium can prevent cisplatin-mediated AKD and to determine safe and effective protocols. Additionally, rasburicase may be considered in patients at high risk for therapy-induced tumour lysis syndrome (TLS)28.

For cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced AKD, an individualized treatment approach, along with standard supportive care, is warranted. Treatment strategies may include volume optimization, correction of electrolyte and acid–base disturbances, hypertension management, discontinuation of the anticancer therapy and initiation of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) when appropriate. Specific therapies may be available for some drug toxicities. For example, glucarpidase may be indicated in some cases of high-dose methotrexate-induced AKD, while KRT is reserved for those with dialysis indications9,25,46,47. Although the organic thiophosphate amifostine may protect against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, we do not support routine use of this agent given the reported adverse effects (particularly nausea, vomiting and hypotension) and persistent concerns about possible interference with the antitumour efficacy of cisplatin48,49,50. Accordingly, management of cisplatin-induced AKD is limited beyond cessation of cisplatin therapy and correction of hypomagnesaemia29. Whether patients with gemcitabine-induced TMA might benefit from complement inhibition is unclear and plasma exchange (PLEX) is not recommended37,44. Ifosfamide-induced AKD has no specific therapy other than correction of electrolyte abnormalities38.

Targeted therapies

Consensus statements

What nephrotoxic manifestations are associated with targeted therapies?

-

Nephrotoxic manifestations of targeted therapies include hypertension, AKI, CKD, proteinuria, nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, and electrolyte abnormalities.

What are the key components of the KHA before initiating targeted therapies?

-

Before initiation of targeted therapy, patients require blood pressure measurement, urine protein quantification (urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR)), measurement of serum electrolytes if they could potentially be affected by the specific therapy (for example, magnesium for patients receiving cetuximab and phosphate for patients receiving erdafitinib) and review of the medication list with attention to agents that could amplify potential adverse kidney events.

-

For patients with AKD or CKD, we suggest nephrology referral before initiation of targeted therapies to guide the KHR.

What are the key diagnostic approaches for evaluating targeted therapy-associated AKD?

-

Diagnostic work-up is guided by the specific targeted therapy and clinical presentation. Kidney biopsy should be considered in selected patients when results may provide information that could change clinical care or in the absence of a clear explanation for AKD.

What are the key considerations for treating complications, stopping the targeted therapy and potentially rechallenging with targeted therapies after AKD?

-

Treatment is guided by the severity of nephrotoxicity and the specific targeted therapy. Decisions to continue, hold, restart or stop targeted therapy should consider the severity and reversibility of the clinical presentation, the availability of alternative therapies, the cancer status and functional status of the patient, and the wishes of the patient and/or caregiver.

Nephrotoxic manifestations associated with targeted therapies

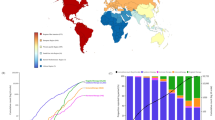

Targeted therapies have revolutionized the treatment of certain cancers by targeting tumour-specific ligands or molecular alterations, enhancing treatment precision while minimizing adverse effects51,52. However, these therapies can have ‘off-target’ effects and adversely affect specific organs, including the kidneys. Nephrotoxicity may occur due to expression of the drug target in kidney cells and is influenced by the role of the kidney in the metabolism and clearance of different drug classes (macromolecules versus small molecules) even when targeting the same receptor (Supplementary Table 2). For example, monoclonal antibodies that target the epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) seem to have a different toxicity profile than EGFR-targeting small molecule TKIs53. Complications that are associated with targeted therapies can manifest in the kidney as hypertension, AKI, CKD, urinary abnormalities (microhaematuria, proteinuria) with or without nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, and electrolyte abnormalities (Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 2).

a, Targeted anticancer agents can damage specific regions of the nephron, including the blood vessels, glomeruli, tubules and surrounding tissue (interstitium). The functional consequence of these insults is acute kidney disease (AKD). These agents might also cause isolated electrolyte abnormalities and/or interfere with tubular creatinine secretion, causing pseudo-acute kidney injury (pseudo-AKI). b, The Kidney Health Assessment, with a specific focus on components that are unique to treatment with targeted agents, serves as a guide for clinicians to anticipate, recognize and manage kidney-related adverse effects in patients with cancer. ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; BCR:ABL, breakpoint cluster region–Abelson fusion protein; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; CDK, cyclin-dependent kinase; CKD, chronic kidney disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; XPO1, exportin 1.

KHA before and during administration of targeted therapies

A comprehensive KHA before initiating targeted therapies is essential to enable distinction between underlying conditions and therapy-associated complications. Following initial assessment, focused evaluations should be conducted regularly throughout the treatment period. Identifying kidney dysfunction before drug initiation and early during therapy can facilitate timely intervention, maximize tolerance and completion of treatment, and impact future treatment decisions, potentially improving patient outcomes (Fig. 2). For example, initial urinalysis is required for all patients starting on VEGF inhibitors (VEGF-I). We suggest that urinalysis should also be checked at each VEGF-I infusion cycle and, if new proteinuria is identified, a UPCR should be obtained to quantify the proteinuria.

Anti-VEGF agents

VEGF-I are associated with development of hypertension in 30–80% of patients and nearly all patients experience a rise in blood pressure54,55,56. Hypertension in these patients is an ‘on-target’ and dose-dependent toxicity that reflects effective inhibition of VEGF signalling57. The mechanisms of VEGF-I-mediated hypertension include an increase in vascular tone caused by endothelial dysfunction, microvascular rarefaction, increased oxidative stress, reduced lymphangiogenesis and sodium and water retention57,58,59,60.

In patients with pre-existing hypertension, effective antihypertensive treatment is critical before initiation of VEGF-I61,62,63. As hypertension onset usually occurs within days of initiating VEGF-I treatment, weekly in-clinic blood pressure monitoring and/or ambulatory home blood pressure monitoring after starting therapy are recommended61,64. The blood pressure threshold for initiating antihypertensive treatment in patients with cancer receiving VEGF-I must be individualized. Although VEGF-I-associated hypertension often resolves with dose reduction or treatment interruption, a rise in blood pressure in patients receiving these therapies may predict better tumour responses, complicating decisions to dose-reduce, hold or restart therapy65,66. For patients without pre-existing risk factors, antihypertensive treatment is recommended when blood pressure exceeds 140/90 mmHg. However, in patients with CKD, diabetes mellitus or a 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score >10%, antihypertensive treatment should be initiated when blood pressure exceeds 130/80 mmHg (refs. 65,66,67). To minimize adverse effects, a less stringent systolic blood pressure goal may be appropriate for some patients with advanced metastatic disease and limited life expectancy. In cases where blood pressure exceeds 180/120 mmHg, treatment should be halted and the patient promptly referred to a hypertension specialist. Patients with hypertensive emergencies (for example, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, stroke or acute myocardial infarction) require inpatient evaluation61,62. The choice of antihypertensive agent should be tailored to the specific risk factors of the patient68.

VEGF-I may induce podocytopathy or glomerular endothelial damage, causing proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome (in 20–63% and 2–6% of patients, respectively)54,55,56. The most common histological findings include TMA in patients treated with bevacizumab and podocytopathies (minimal change disease or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis) in patients treated with TKIs56. In cases of proteinuria <2 g per day, cancer treatment may continue, with hypertension and proteinuria management using renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors69. However, the presence of nephrotic syndrome, AKI or TMA typically necessitates discontinuation of the offending agent. A kidney biopsy is often recommended to guide treatment decisions when symptoms persist or worsen despite VEGF-I cessation70. The role of complement inhibitors in treating VEGF-I-associated TMA remains unclear71. A multidisciplinary approach is critical when determining whether to discontinue VEGF-targeted therapy or switch to an alternative class of anticancer therapy.

Immunotherapy

Consensus statements

What is the epidemiology of ICI-AKD?

-

The incidence of immune-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI)-associated AKI (ICI-AKI) varies from 2% to 5%.

-

Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use has been identified as a consistent risk factor for (ICI)-associated AKD (ICI-AKD). Other potential risk factors include CKD and combination ICI therapy.

-

We recommend that future epidemiological studies should include ICI-treated patients with and without ICI-AKD to enable elucidation of risk factors.

How should ICI-AKD be defined?

We suggest the following definition for ICI-AKD:

-

Acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) or another ICI-associated lesion on kidney biopsy OR

-

An increase in SCr to ≥1.5-fold higher than the pre-ICI baseline value in the absence of an alternative plausible aetiology.

What are key potential mechanisms of ICI-AKD?

-

Mechanisms of ICI-AKD are not entirely understood but likely include direct and indirect effects of immune cell activation, resulting in loss of self-tolerance.

-

Preclinical models that more closely resemble human ICI-AKD and multicentre efforts to biobank patient samples are essential for the study of ICI-AKD pathophysiology.

What are key components of the KHA and KHR before initiating ICI therapy?

-

Baseline urinalysis is crucial to identify pre-existing abnormalities that might complicate the diagnosis of future AKD.

-

We suggest avoidance of PPIs and other ATIN-causing drugs (for example, NSAIDs) before initiating ICI therapy.

What are the key diagnostic considerations in patients with suspected ICI-AKD?

In patients with suspected ICI-AKD, we suggest the following:

-

Prompt nephrology referral.

-

Assessment for ATIN-causing medications, urinary abnormalities (for example, unexplained pyuria, haematuria, proteinuria), eosinophilia and extrarenal immune-related adverse events.

-

Use of novel biomarkers of ICI-AKD (including plasma and/or urinary biomarkers and imaging studies), if available.

Which patients with suspected ICI-AKD should be considered for kidney biopsy?

-

We suggest that patients with ICI-AKD undergo a kidney biopsy if diagnostic uncertainty exists and findings could change management.

What are the key management considerations for patients with suspected ICI-AKD?

Important considerations include:

-

Withholding of ICI therapy until AKD has recovered or stabilized.

-

Withdrawal of PPI therapy and other ATIN-causing drugs, if feasible.

-

Prompt initiation of glucocorticoids, even if awaiting kidney biopsy.

-

Consideration of ICI rechallenge.

Which populations warrant additional consideration when treating with ICIs?

-

Kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) and patients with pre-existing kidney-related autoimmune conditions may be at increased risk of ICI-related kidney complications. We suggest careful assessment of the risks and benefits of initiating ICI therapy, along with possible adjustment of immunosuppression and close monitoring of kidney and autoimmune parameters in these patients.

Epidemiology and risk factors for ICI-AKD

The incidence of ICI-AKI, when AKI is directly attributed to the ICI, is reported to be 2–5%72,73. Real-world studies report that 15–25% of ICI-treated patients develop AKI, but this figure includes aetiologies other than ICI-AKI such as haemodynamic AKI or obstruction74,75,76,77. The incidence of ICI-AKD, which encompasses a broader spectrum and longer duration of kidney dysfunction than ICI-AKI, is unknown. The median onset of ICI-AKI is 16 weeks following ICI initiation, but patients may develop ICI-AKI as early as within the first 3 weeks to as late as 1 year following initiation7. Importantly, ICI-AKD may also occur several months after completing the last ICI cycle7.

PPI use has emerged as a consistent risk factor for ICI-AKD, whereas data on the associations between CKD and ICI-AKD and between concomitant use of more than one ICI and ICI-AKD are mixed7,77,78,79,80 (Table 3). The presence of pyuria, sub-nephrotic range proteinuria, haematuria, eosinophilia, and prior or concurrent extrarenal immune-related adverse events are supportive of a diagnosis of ICI-AKD, but these findings are neither sensitive nor specific7. ATIN is the most common histopathological manifestation of ICI-AKD, but a range of other pathologies have also been observed, including various glomerular, acid–base and electrolyte disorders7,81,82,83,84. With a few exceptions, epidemiological studies in patients with ICI-AKD have lacked a control group of ICI-treated patients without AKD7,75,76,77,79,85 (Table 3). To further elucidate the risk factors, we recommend that future studies include ICI-treated patients with and without ICI-AKD.

Mechanisms of ICI-AKD

ICIs elicit tumour immune responses by unleashing co-inhibitory signalling against tumour neoantigens. Concurrently, unopposed immune activation can lead to loss of self-tolerance, manifesting as immune-related adverse events in various organs, including the kidney86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95. To better understand the precise mechanisms of ICI-AKD and of immune-related adverse events in general, better preclinical models and the establishment of multicentre data and tissue repositories are needed to facilitate translational research efforts96,97,98.

KHA before initiation of ICI therapy

Before initiation of ICI therapy, baseline urinalysis is crucial to identify pre-existing abnormalities that might complicate the diagnosis of future AKD. In select patients with pre-existing CKD or autoimmune disease involving the kidney, urine protein quantification should be considered. Beyond these laboratory tests, a thorough assessment of medications is recommended. PPIs should be avoided if feasible. Other medications that may induce ATIN, such as antibiotics and NSAIDs, may also contribute to the risk of ICI-AKD, though further confirmatory data are needed7,77,78,80.

Diagnosis of ICI-AKD

Although non-specific, the presence of concomitant ATIN-causing medications (for example, PPIs), urinary abnormalities (for example, unexplained pyuria), eosinophilia and concomitant extrarenal immune-related adverse events should be considered when assessing patients with suspected ICI-AKD, as each of these factors may increase its likelihood. Various urinary, plasma and imaging biomarkers can assist in the non-invasive diagnosis of ICI-AKD. For example, serum C-reactive protein and the ratio of urine retinol-binding protein to creatinine may be increased in patients with ICI-AKI99. The levels of soluble IL-2 receptor-α, a cytokine that correlates with T cell activation, were elevated in patients with ICI-AKI compared with patients on ICIs without immune-related adverse events and patients not on ICIs with other causes of ATIN; however, a key limitation was that the study did not include a comparison with patients on ICI therapy with other causes of AKI100. The levels of urinary chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) are increased in patients with ATIN in multiple contexts, but these findings require validation in patients with ICI-AKD101,102. Similarly, increased kidney glucose uptake on positron emission tomography has been demonstrated in patients with ICI-AKD; however, additional validation is needed103,104,105. Finally, small studies suggest that renal tubular expression of programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PDL1) may be higher in kidney biopsy samples from patients with ICI-AKD than in those from patients with AKD not related to ICIs; however, standardization of antibodies and staining protocols, along with larger studies, are needed to confirm these findings106.

Although ATIN is the most common histopathological manifestation of ICI-AKD, a range of glomerular pathologies that require kidney biopsy for diagnosis have also been observed7,81,84. In the setting of an abnormal urinalysis (for example, with haematuria or proteinuria), urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and UPCR should be analysed along with other testing, as appropriate. Kidney biopsy should also be strongly considered if diagnostic uncertainty exists and the findings could change the course of treatment.

Management of ICI-AKD and consideration of ICI rechallenge

In patients with suspected ICI-AKD, ICI treatment should be paused and potential triggers (for example, PPIs) eliminated when possible. Given that ATIN is the most common pathological lesion, the mainstay of treatment is glucocorticoids7,79. Expert guidelines suggest that initial glucocorticoid dosing for ICI-ATIN should be 0.5–1 mg/kg of prednisone equivalent, although some patients with moderate-to-severe AKI may benefit from intravenous glucocorticoids at higher doses. Importantly, early initiation of glucocorticoids has been associated with higher odds of kidney recovery7,107,108.

The optimal duration of glucocorticoids for treatment of ICI-AKD is unknown. Guidelines recommend tapering of glucocorticoids over at least 4–8 weeks107,109; however, two observational studies found that patients treated with a shorter duration of glucocorticoids (3–4 weeks) did not have a higher risk of recurrent ICI-AKD than those receiving longer durations110,111,112. Some patients respond to glucocorticoids alone, but others may need additional immunosuppression81,84, particularly those with ICI-associated glomerular pathologies108. These treatment decisions require multidisciplinary discussions between haematology, oncology, nephrology and, often, rheumatology.

Once ICI-AKD has been treated, ICI rechallenge may be considered as the risk of recurrent ICI-AKD is <20%7. However, the decision to rechallenge involves weighing the risks of recurrent ICI-AKD and other immune-related adverse events against the benefits of treating progressive cancer.

Special populations: KTRs and patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders

ICIs are a feasible option for KTRs with cancer; however, the incidence of T cell-mediated and antibody-mediated rejection in those receiving these therapies is 30–40%113,114. Accordingly, the following factors should be considered in the shared decision to initiate ICIs in KTRs: transplant duration, presence of donor-specific antibodies, previous rejection, availability of alternative treatment for cancer and patient preferences (weighing the risk of inferior cancer outcomes versus the risk of returning to dialysis). Increasing or restarting glucocorticoids prior to ICI treatment and assessing the suitability of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors as an alternative to calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) should be considered115.

Similarly, ICI use is feasible in patients with pre-existing autoimmune disorders who develop cancer; however, disease activity, level of immunosuppression, and the extent of organ damage and function should be considered when weighing the risks and benefits of initiating ICI therapy in this population116.

HCT and cellular therapies

Consensus statements

What are the unique nephrotoxic manifestations associated with HCT and cellular therapies?

-

Nephrotoxic manifestations associated with HCT and cellular therapies include a diverse range of pathologies, underscoring the complex nature of these patient populations.

-

Toxicities include endothelial injury syndromes, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), TLS, cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and opportunistic infections with and without sepsis.

What are the key components of the KHA before and during HCT and cellular therapies?

-

Urine protein quantification before HCT and cellular therapies can inform risk of AKD by detecting pre-existing kidney abnormalities.

-

Incorporating longitudinal GFR assessment and urine protein quantification at baseline and at routine post-therapy milestone assessments offers opportunities to improve long-term kidney outcomes and overall survival.

What are the key diagnostic considerations in patients with AKD or CKD during HCT and cellular therapies?

-

Key diagnostic evaluation of AKD or CKD after HCT and cellular therapies includes urinalysis, urine microscopy, urine protein quantification and transplant-associated TMA (TA-TMA) work-up in patients at high risk.

-

Kidney biopsy has a role in unexplained AKD or CKD when findings could result in treatment changes.

What are the key AKD prevention and management considerations in patients receiving HCT and cellular therapies?

-

General supportive measures remain critical. Specific prevention and management strategies may be available for certain patients based on AKD aetiology.

-

Patients with a high tumour burden immediately before HCT and cellular therapies are at high risk of TLS and may benefit from early nephrology referral. Specific TLS prophylactic measures should be instituted in patients at high risk.

What are the key diagnostic and treatment considerations for TA-TMA?

-

Urine protein quantification is critical in patients at risk for TA-TMA.

-

Treatment of TA-TMA may include management of GVHD, treatment of underlying infections and use of complement-directed therapies.

What are the special considerations for KTRs and patients on dialysis undergoing HCT and CAR T cell therapy?

-

Selected KTRs and patients on dialysis have been safely and effectively treated with autologous HCT, allogeneic HCT and CAR T cell therapy.

-

Limited data exist regarding patient selection and management of immunosuppression for KTRs being considered for allogeneic HCT or CAR T cell therapy.

-

Limited data exist regarding appropriate and safe fludarabine dosing and timing for patients on dialysis receiving HCT and CAR T cell therapy.

Challenges and opportunities in HCT and cellular therapy

HCT and cellular therapies, such as CAR T cell therapy and bispecific T cell engager therapy, pose unique challenges. Ongoing advances in supportive care, conditioning regimens and HLA matching (for HCT) are expanding access to older patients and those with more comorbidities117,118. A corresponding need exists to focus on kidney protection before and after treatment to mitigate toxicity and improve survival. Multidisciplinary collaboration between nephrology, haematology/oncology, infectious disease, oncopharmacy and nursing is essential.

Mechanisms of nephrotoxicity during HCT and cellular therapy

Nephrotoxicities associated with HCT are largely driven by endothelial injury and include capillary leak syndrome, engraftment syndrome, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS; previously known as veno-occlusive disease), acute and chronic GVHD, and TA-TMA. Additional causes of AKD or CKD in the post-HCT setting include injury secondary to conditioning regimens, sepsis, viral nephritides (for example, BK virus, adenovirus), CNI-induced kidney injury, TLS, post-transplant nephrotic syndrome (for example, membranous nephropathy, minimal change disease) and electrolyte disorders119,120.

TLS and CRS are primary drivers of nephrotoxicity during and after cellular therapies121,122. In addition, although not strictly a nephrotoxicity, patients receiving cellular therapies may experience severe hypophosphataemia in association with immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome123.

Baseline and longitudinal KHA during HCT and cellular therapy

A detailed KHA, including accurate estimation or measurement of glomerular filtration rate, is essential to guide appropriate patient selection for HCT and cellular therapies, to select the appropriate preparative regimens (for example, melphalan dosing in autologous HCT, intensity of conditioning regimens in allogeneic HCT (myeloablative versus reduced intensity), and choice of bridging and lymphodepletion regimens for cellular therapies), to select appropriate GVHD prophylactic regimens for HCT recipients, to prevent kidney toxicity and associated morbidity and/or mortality and to determine which patients are at highest risk for severe TLS.

In patients receiving HCT and cellular therapies, albuminuria or proteinuria are associated with incident or progressive CKD, progression to kidney failure and mortality124. As TA-TMA and other types of post-therapy kidney injury may be associated with new or worsening proteinuria, obtaining baseline spot UACR and/or UPCR in all patients is essential to characterize their underlying kidney health125. Routine baseline 24-h urine collection is reserved for those with plasma cell dyscrasias to track treatment response126,127.

Early identification of AKD or CKD and subsequent referral to nephrology are critical to post-treatment survivorship. We therefore advocate for incorporating spot UACR and/or UPCR into routine post-therapy milestone assessments (that is, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year), with nephrology referral for newly elevated UACR (>30 mg/g) or UPCR (>200 mg/g).

Diagnosis of AKD or CKD after HCT and cellular therapy

Although patients receiving HCT and cellular therapy frequently experience AKD or CKD aetiologies common to other populations, they are also at risk of unique toxicities (as outlined above). Special considerations include the timing of kidney injury relative to HCT or cellular therapy, the type of transplant or cell product used for therapy and the type of preparative regimen or lymphodepleting chemotherapy, with additional work-up for therapy-specific causes (for example, CNI toxicity, SOS, TA-TMA, TLS or CRS) as appropriate.

Kidney biopsy can have a critical role in diagnosis, especially in patients with AKD or CKD after HCT, who often have complex comorbidities and multiple coexisting potential causes of AKD or CKD120,128,129,130. However, biopsy is often deferred due to thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy128,129. Additional research and development of biopsy algorithms that address and mitigate bleeding risk are critical.

Prevention and management of AKD after HCT and cellular therapy

Prevention and management of AKD are as per the standard of care but with special attention to patient-specific factors (for example, increased risk of SOS, engraftment syndrome, TA-TMA and viral infections). Choice of pre-HCT conditioning regimen and donor source should be tailored to individual disease status and comorbidities. Reduced intensity conditioning may be considered in patients at high risk. Although studies have demonstrated a reduced incidence of AKI among patients receiving T cell-depleted HCT, this approach has not been widely adopted given concerns surrounding increased risks of relapse, graft failure and infection131,132,133,134.

General AKD prevention measures include judicious fluid management, cautious use of nephrotoxic medications and iodinated contrast, prompt treatment of infections and GVHD, and close monitoring of CNI levels. Specific prevention (for example, TLS prophylaxis) and treatment strategies (for example, defibrotide for SOS) will depend on patient-specific and transplant-specific factors135,136,137. Further research is needed regarding optimal management and timing of dialysis in this context.

Patients with a high tumour burden at the time of HCT and cellular therapy are at increased risk of TLS122,138. Appropriate prevention and management strategies in this context are unknown. In the absence of specific data in the settings of HCT and cellular therapy, we recommend following standard preventative and management strategies for TLS. We suggest early nephrology consultation for patients at increased risk of TLS (for example, those with active leukaemia or high-grade lymphoma, significantly elevated lactate dehydrogenase), before development of AKD, to facilitate timely coordination of care, intensive care unit transfer and initiation of rasburicase and/or KRT when indicated28,137.

Special considerations: TA-TMA

TA-TMA is a severe complication after allogeneic HCT with high mortality (60–90%) in untreated patients139,140. Management of TA-TMA remains challenging, with insufficient diagnostic criteria, a lack of appropriate biomarkers, and an unmet need for safe and effective therapies141,142. Proteinuria assessment is critical for diagnosis and risk stratification of TA-TMA, as patients with UPCR ≥1 g/g are at increased risk of multi-organ dysfunction syndrome and death125. Treatment of TA-TMA may include treatment of underlying infection or GVHD, CNI dose reduction or discontinuation, rituximab and/or anticomplement therapy143.

Special populations: KTRs and patients on dialysis

Cancer is a leading cause of death among KTRs and is potentially related to reduced immune surveillance, impaired defence against oncogenic viruses and pathways specific to immunosuppression regimens144. HCT after kidney transplantation presents several challenges, including a risk of kidney transplant rejection (with allogeneic HCT), infection and malignancy relapse owing to immunosuppression and uncertainties in conditioning regimen dosing145,146. Data on CAR T cell therapy in KTRs are evolving, with case reports and series demonstrating safe and effective administration of CD19-targeted therapy for post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder144,147. For KTRs undergoing CAR T cell therapy, data are lacking regarding dosing and regimen of lymphodepletion therapy (particularly fludarabine), immunosuppression adjustments throughout the CAR T cell process (leukapheresis, manufacturing, infusion) to maximize CAR T cell yield and function while minimizing rejection and infection risks and the use of non-invasive biomarkers to diagnose acute rejection147,148,149. Limited observational data suggest that the risk of rejection is reduced when cyclophosphamide is included in the lymphodepletion regimen150,151,152,153.

Data regarding HCT in patients on dialysis are limited154,155,156. Both CD19-targeted and B cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-targeted CAR T cell therapy have been administered in selected patients receiving haemodialysis, with apparent short-term safety and efficacy157. For patients on dialysis treated with HCT and CAR T cell therapy, uncertainties remain regarding the appropriate and safe dosing of fludarabine and timing of dialysis157. Future research in these areas is needed.

Anticancer therapy dosing in patients with impaired kidney function

Consensus statements

What is the impact of the lack of KHA and dosing guidelines for patients with AKD, CKD and/or receiving KRT?

-

Uncertainty regarding the approach to kidney function assessment.

-

Increased risk of anticancer agent systemic and kidney toxicity.

-

Suboptimal receipt of anticancer agents.

-

Potentially inappropriate inclusion or exclusion from clinical trials.

-

Increased cancer morbidity and mortality.

What are the potential impacts of clinically available drug level measurement and its utilization for patients with AKD, CKD and/or receiving KRT?

-

Dosing to achieve optimal levels for anticancer therapy safety and efficacy in the individual patient.

-

Informed management of dose-dependent systemic and kidney toxicities.

How are the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of anticancer therapies impacted by AKD, CKD and/or receipt of KRT?

-

AKD and CKD can affect anticancer therapy pharmacokinetics by altering absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion as well as pharmacodynamics by altering drug binding, therapeutic index and dose–response curves.

What clearance characteristics are to be considered with regards to blood purification therapies to optimize efficacy or treat toxicity?

-

Characteristics to consider for extracorporeal blood purification therapies to optimize efficacy or treat toxicity include molecular weight, volume of distribution, protein binding, timing of administration and therapy modality.

Burden associated with lack of KHA and drug dosing guidelines for patients with impaired kidney function

Consensus and precise guidance for drug dosing for patients with AKD, CKD and/or receiving KRT are lacking. As variable methods of GFR assessment are used in cancer clinical trials, uncertainty exists regarding the optimal approaches for determining patient eligibility and conducting renal pharmacokinetic analyses158. Despite poor use in clinical practice and a lack of correlation with GFR, creatinine clearance was used to estimate kidney function in most pivotal trials and pharmacokinetic analyses conducted between 2015 and 2019 (ref. 4). Imprecise estimation of GFR and overall kidney function coupled with inaccurate determination of drug dosing can lead to either suboptimal dosing or to an increased risk of anticancer therapy nephrotoxicity, especially in patients with CKD with an estimated increased risk of more than 1.8-fold159 (Supplementary Table 3).

Potential benefits of clinically available drug level monitoring

Therapeutic drug monitoring could help achieve optimal levels of anticancer agents, promoting safety and efficacy in individual patients. Most anticancer agents have narrow therapeutic ranges. For example, in patients treated with pazopanib, trough levels of ≥20 mg/l are associated with improved progression-free survival; however, only 80% of patients who receive the approved dose of 800 mg once daily reach this pharmacokinetic threshold160. Therapeutic drug monitoring could enable more patients to receive effective dosing161 and could enable informed management of dose-dependent systemic and kidney toxicities, as currently practised for patients receiving high-dose methotrexate47. Therapeutic drug monitoring is available for several anticancer drugs (Supplementary Table 4).

Impact of AKD and CKD on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic mechanisms of anticancer agents

AKD and CKD have an important impact on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic mechanisms of anticancer agents (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 2). In vivo, most drugs are cleared by elimination of unchanged drug by the kidney and/or by metabolism in the liver and/or small intestine. The amount of excretion of an unchanged drug or its metabolites by the kidney is the net result of glomerular filtration, tubular secretion, tubular reabsorption and, to a lesser degree, drug metabolism in the kidney162. Consequently, drug clearance by kidney excretion is decreased in patients with AKD or CKD, requiring different recommended dosages. Of note, certain anticancer drugs, such as 5-fluorouracil, are metabolized in the liver, but have active metabolites that may be excreted by the kidney and accumulate in patients with AKD, CKD and/or receiving KRT163. Impaired kidney function has also been associated with changes in drug absorption, plasma protein binding or distribution, as well as with decreased non-renal clearance of drugs eliminated through the liver and gut. Accumulation of uraemic toxins in patients with reduced kidney function could potentially inhibit hepatic metabolic enzymes such as cytochrome P450 3A, affect the uptake of transporters such as organic anion-transporting polypeptides in the hepatocyte membrane and impair bile excretion through efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein164 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Although emerging evidence has aided the understanding of pharmacokinetic mechanisms, the true impact of reduced kidney function on pharmacokinetics, along with pharmacodynamic mechanisms of commonly used anticancer agents, remains unclear and poorly evaluated, with substantial uncertainty surrounding the potential clinical implications for patients with AKD or CKD and cancer (Table 4 and Supplementary Table 6). Carboplatin is one of the few anticancer agents for which direct dose adjustment based on patient GFR exists (that is, using the Calvert equation)21,165. An additional challenge is the use of anticancer agents as part of multidrug regimens, with potential for drug–drug interactions. Solid-organ transplant recipients with cancer represent a special group of interest who require both anticancer regimens and immunosuppressive agents.

Use of extracorporeal blood purification techniques to optimize the efficacy and treat the toxicity of anticancer therapies

Extracorporeal blood purification techniques include dialytic, plasma separation, and absorption or adsorption modalities. These platforms rely on filters with either semi-permeable membranes (dialytic or plasma separation), dynamic binding capabilities (absorption or adsorption) or centrifugation for plasma separation166. Anticancer drug clearance depends on both the modality characteristics and the physicochemical properties of the drug167 (Table 4). For example, a drug with molecular dimensions smaller than the dialyzer pore size, a low protein binding percentage and a low volume of distribution will be removed easily by dialytic therapies. Conversely, a drug without any of these properties will not be cleared by standard dialytic modalities (that is, intermittent haemodialysis or continuous KRT) but would be removed by PLEX.

An important, common and complex clinical scenario pertains to the timing of anticancer drug dosing around extracorporeal blood purification procedures, especially intermittent haemodialysis and PLEX. Although dosing of drugs after an extracorporeal blood purification procedure is likely the optimal approach, multidrug protocols are often not amenable to this timing if the intent is to provide extracorporeal clearance to mitigate toxicity. We suggest a potential algorithm to assist in anticancer drug timing based on drug physicochemical characteristics and blood purification modality (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Unmet needs to enable safe, optimal and equitable anticancer agent dosing and delivery

The overarching aim of providing safe and efficacious anticancer agents to patients with various states of kidney health requires a sequential, multipronged, multidisciplinary approach. Randomized controlled trials of anticancer drugs should include pre-specified subgroup analyses or parallel trials for patients with CKD, particularly in cancers with substantial impact on kidney function (for example, multiple myeloma, renal cell carcinoma). Post-marketing studies in patients with more advanced CKD should also be conducted to close knowledge gaps remaining from clinical trials. The goal of future studies should be to provide robust data to inform subsequent guidelines and statements and ultimately improve outcomes for patients with coexisting cancer and kidney disease (Box 1).

Conclusions

Advances in the understanding of cancer biology have led to the development of more effective anticancer therapies. However, nephrotoxic manifestations of both older and newer therapies continue to pose substantial challenges in cancer care. Furthermore, consensus and precise guidance on kidney function estimation and drug dosing for patients with AKD, CKD and/or receiving KRT is lacking, limiting access to life-saving therapies and jeopardizing outcomes. We propose methodologies to better assess kidney health, optimize dosing of anticancer agents, and prevent and manage therapy-related complications, with the aim of improving patient outcomes and fulfilling the potential of these ground-breaking therapies.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024 (American Cancer Society, 2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Global trends in incidence, death, burden and risk factors of early-onset cancer from 1990 to 2019. BMJ Oncol. 2, e000049 (2023).

Kitchlu, A. et al. Cancer risk and mortality in patients with kidney disease: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 80, 436–448.e1 (2022).

Butrovich, M. A. et al. Inclusion of participants with CKD and other kidney-related considerations during clinical drug development: landscape analysis of anticancer agents approved from 2015 to 2019. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 18, 455–464 (2023).

Kitchlu, A. et al. Representation of patients with chronic kidney disease in trials of cancer therapy. JAMA 319, 2437–2439 (2018).

Salahudeen, A. K. & Bonventre, J. V. Onconephrology: the latest frontier in the war against kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 24, 26–30 (2013).

Gupta, S. et al. Acute kidney injury in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 9, e003467 (2021).

Gupta, S. et al. Derivation and external validation of a simple risk score for predicting severe acute kidney injury after intravenous cisplatin: cohort study. BMJ 384, e077169 (2024).

Gupta, S. et al. Glucarpidase for treatment of high-dose methotrexate toxicity. Blood 145, 1858–1869 (2025).

Charkviani, M. et al. Incidence of acute kidney injury in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma treated with teclistamab versus CAR T-cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 40, 1512–1521 (2025).

Ronco, C., Kellum, J. A., Bellomo, R. & Mehta, R. L. Acute dialysis quality initiative (ADQI). Contrib. Nephrol. 182, 1–4 (2013).

Kellum, J. A. et al. Kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) acute kidney injury work group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. Suppl. https://doi.org/10.1038/kisup.2012.1 (2012).

Lameire, N. H. et al. Harmonizing acute and chronic kidney disease definition and classification: report of a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference. Kidney Int. 100, 516–526 (2021).

Rosner, M. H. & Perazella, M. A. Acute kidney injury in patients with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 1770–1781 (2017).

Kashani, K., Rosner, M. H. & Ostermann, M. Creatinine: from physiology to clinical application. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 72, 9–14 (2020).

Rosner, M. H. & Bolton, W. K. Renal function testing. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 47, 174–183 (2006).

Chen, J., Wang, X., Luo, P. & He, Q. Effects of unidentified renal insufficiency on the safety and efficacy of chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a prospective, observational study. Supportive Care Cancer 23, 1043–1048 (2015).

Rosner, M. H., Sprangers, B., Sandhu, G. & Malyszko, J. Glomerular filtration rate measurement and chemotherapy dosing. Semin. Nephrol. 42, 151340 (2022).

Kitchlu, A. et al. Assessment of GFR in patients with cancer: a statement from the American Society of Onco-nephrology. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 1061–1072 (2024).

Titan, S. M. et al. Performance of creatinine and cystatin-based equations on estimating measured GFR in people with hematological and solid cancers. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 20, 358–366 (2025).

Kitchlu, A. et al. Assessment of GFR in patients with cancer part 2: anticancer therapies-perspectives from the American Society of Onco-nephrology (ASON). Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 1073–1077 (2024).

Ebert, N. et al. Iohexol plasma clearance measurement protocol standardization for adults: a consensus paper of the European Kidney Function Consortium. Kidney Int. 106, 583–596 (2024).

Dorshow, R. B., Debreczeny, M. P. & Goldstein, S. L. Glomerular filtration rate measurement utilizing transdermal detection methodology. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 36, 1592–1602 (2025).

Dorshow, R. B., Debreczeny, M. P., Goldstein, S. L. & Shieh, J.-J. Clinical validation of the novel fluorescent glomerular filtration rate tracer agent relmapirazin (MB-102). Kidney Int. 106, 679–687 (2024).

Howard, S. C., McCormick, J., Pui, C.-H., Buddington, R. K. & Harvey, R. D. Preventing and managing toxicities of high-dose methotrexate. Oncologist 21, 1471–1482 (2016).

Gupta, S. et al. Effect of intravenous magnesium on cisplatin-associated AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2024f6e9f5yf (2024).

Gupta, S. et al. Intravenous magnesium and cisplatin-associated acute kidney injury: a multicenter cohort study. JAMA Oncol. 11, 636–643 (2025).

Latcha, S. & Shah, C. V. Rescue therapies for AKI in onconephrology: rasburicase and glucarpidase. Semin. Nephrol. 42, 151342 (2022).

Gupta, S., Portales-Castillo, I., Daher, A. & Kitchlu, A. Conventional chemotherapy nephrotoxicity. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 28, 402–414.e1 (2021).

Latcha, S. et al. Long-term renal outcomes after cisplatin treatment. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 1173–1179 (2016).

Motwani, S. S. et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for acute kidney injury after the first course of cisplatin. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 682–688 (2018).

De Jongh, F. E. et al. Weekly high-dose cisplatin is a feasible treatment option: analysis on prognostic factors for toxicity in 400 patients. Br. J. Cancer 88, 1199–1206 (2003).

Ensergueix, G. et al. Ifosfamide nephrotoxicity in adult patients. Clin. Kidney J. 13, 660–665 (2020).

Farry, J. K., Flombaum, C. D. & Latcha, S. Long term renal toxicity of ifosfamide in adult patients — 5 year data. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 1326–1331 (2012).

de Rouw, N. et al. Cumulative pemetrexed dose increases the risk of nephrotoxicity. Lung Cancer 146, 30–35 (2020).

Umehara, K. et al. Long-term exposure to pemetrexed induces chronic renal dysfunction in patients with advanced and recurrent non-squamous cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Ren. Replace. Ther. 6, 43 (2020).

Izzedine, H. et al. Gemcitabine-induced thrombotic microangiopathy: a systematic review. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 21, 3038–3045 (2006).

Garcia, G. & Atallah, J. P. Antineoplastic agents and thrombotic microangiopathy. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 23, 135–142 (2017).

Rice, M. L. et al. Development and validation of a model to predict acute kidney injury following high-dose methotrexate in patients with lymphoma. Pharmacotherapy 44, 4–12 (2024).

Perazella, M. A. Crystal-induced acute renal failure. Am. J. Med. 106, 459–465 (1999).

Solanki, M. H. et al. Magnesium protects against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by regulating platinum accumulation. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 307, F369–F384 (2014).

Solanki, M. H. et al. Magnesium protects against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury without compromising cisplatin-mediated killing of an ovarian tumor xenograft in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 309, F35–F47 (2015).

Suppadungsuk, S. et al. Preloading magnesium attenuates cisplatin-associated nephrotoxicity: pilot randomized controlled trial (PRAGMATIC study). ESMO Open 7, 100351 (2022).

Bertin, L. et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy after long-lasting treatment by gemcitabine: description, evolution and treatment of a rare case. J. Med. Cases 15, 272–277 (2024).

Gupta, S. et al. High-dose IV magnesium in mesothelioma patients receiving surgery with hyperthermic intraoperative cisplatin: pilot studies and design of a phase II randomized clinical trial. J. Surg. Oncol. 128, 1141–1149 (2023).

Kitchlu, A. & Shirali, A. C. High-flux hemodialysis versus glucarpidase for methotrexate-associated acute kidney injury: what’s best? J. Onco-Nephrol. 3, 11–18 (2019).

Ramsey, L. B. et al. Consensus guideline for use of glucarpidase in patients with high-dose methotrexate induced acute kidney injury and delayed methotrexate clearance. Oncologist 23, 52–61 (2018).

Kemp, G. et al. Amifostine pretreatment for protection against cyclophosphamide-induced and cisplatin-induced toxicities: results of a randomized control trial in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 14, 2101–2112 (1996).

Capizzi, R. L. Amifostine reduces the incidence of cumulative nephrotoxicity from cisplatin: laboratory and clinical aspects. Semin. Oncol. 26, 72–81 (1999).

Castiglione, F., Dalla Mola, A. & Porcile, G. Protection of normal tissues from radiation and cytotoxic therapy: the development of amifostine. Tumori 85, 85–91 (1999).

Björkholm, M. et al. Success story of targeted therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia: a population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 2514–2520 (2011).

Araghi, M. et al. Recent advances in non-small cell lung cancer targeted therapy; an update review. Cancer Cell Int. 23, 162 (2023).

Porta, C., Cosmai, L., Gallieni, M., Pedrazzoli, P. & Malberti, F. Renal effects of targeted anticancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 11, 354–370 (2015).

Izzedine, H., Rixe, O., Billemont, B., Baumelou, A. & Deray, G. Angiogenesis inhibitor therapies: focus on kidney toxicity and hypertension. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 50, 203–218 (2007).

Izzedine, H. et al. VEGF signalling inhibition-induced proteinuria: mechanisms, significance and management. Eur. J. Cancer 46, 439–448 (2010).

Izzedine, H. et al. Kidney diseases associated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): an 8-year observational study at a single center. Medicine 93, 333–339 (2014).

Robinson, E. S., Khankin, E. V., Karumanchi, S. A. & Humphreys, B. D. Hypertension induced by vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibition: mechanisms and potential use as a biomarker. Semin. Nephrol. 30, 591–601 (2010).

Makino, K. et al. Impacts of negative and positive life events on development of social frailty among community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 25, 690–696.e1 (2024).

Van Der Veldt, A. A. M. et al. Reduction in skin microvascular density and changes in vessel morphology in patients treated with sunitinib. Anticancer. Drugs 21, 439–446 (2010).

Touyz, R. M., Herrmann, S. M. S. & Herrmann, J. Vascular toxicities with VEGF inhibitor therapies-focus on hypertension and arterial thrombotic events. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 12, 409–425 (2018).

Herrmann, J. et al. Defining cardiovascular toxicities of cancer therapies: an international cardio-oncology society (IC-OS) consensus statement. Eur. Heart J. 43, 280–299 (2022).

Pandey, S., Kalaria, A., Jhaveri, K. D., Herrmann, S. M. & Kim, A. S. Management of hypertension in patients with cancer: challenges and considerations. Clin. Kidney J. 16, 2336–2348 (2023).

Cohen, J. B. et al. Cancer therapy-related hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 80, e46–e57 (2023).

Azizi, M., Chedid, A. & Oudard, S. Home blood-pressure monitoring in patients receiving sunitinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 95–97 (2008).

Snider, K. L. & Maitland, M. L. Cardiovascular toxicities: clues to optimal administration of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling pathway inhibitors. Target. Oncol. 4, 67–76 (2009).

Humphreys, B. D. & Atkins, M. B. Rapid development of hypertension by sorafenib: toxicity or target? Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 5947–5949 (2009).

McFarlane, S. I. & Bakris, G. L. Diabetes and Hypertension: Evaluation and Management. Diabetes and Hypertension: Evaluation and Management 1st edn (Humana Press, 2012).

Williams, B. et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 39, 3021–3104 (2018).

Van Dorst, D. C. H. et al. Treatment and implications of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor-induced blood pressure rise: a clinical cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e028050 (2023).

Fenoglio, R. et al. The need for kidney biopsy in the management of side effects of target and immunotherapy. Front. Nephrol. 3, 1043874 (2023).

Padilha, W. S. C. et al. Bevacizumab-associated thrombotic microangiopathy treated with eculizumab: a case report. Am. J. Case Rep. 24, e940906 (2023).

Cortazar, F. B. et al. Clinicopathological features of acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Kidney Int. 90, 638–647 (2016).

Manohar, S. et al. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor treatment is associated with acute kidney injury and hypocalcemia: meta-analysis. Nephrol. Dialysis Transplant. 34, 108–117 (2019).

Xie, W. et al. Incidence, mortality, and risk factors of acute kidney injury after immune checkpoint inhibitors: systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 115, 88–95 (2023).

Koks, M. S. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated acute kidney injury and mortality: an observational study. PLoS One 16, e0252978 (2021).

Meraz-Muñoz, A. et al. Acute kidney injury associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: incidence, risk factors and outcomes. J. Immunother. Cancer 8, e000467 (2020).

Seethapathy, H. et al. The incidence, causes, and risk factors of acute kidney injury in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 1692–1700 (2019).