Abstract

Single-molecule imaging with atomic resolution is a notable method to study various molecular behaviours and interactions1,2,3,4,5. Although low-dose electron microscopy has been proved effective in observing small molecules6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, it has not yet helped us achieve an atomic understanding of the basic physics and chemistry of single molecules in porous materials, such as zeolites14,15,16. The configurations of small molecules interacting with acid sites determine the wide applications of zeolites in catalysis, adsorption, gas separation and energy storage17,18,19,20,21. Here we report the atomic imaging of single pyridine and thiophene confined in the channel of zeolite ZSM-5 (ref. 22). On the basis of integrated differential phase contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy (iDPC-STEM)23,24,25, we directly observe the adsorption and desorption behaviours of pyridines in ZSM-5 under the in situ atmosphere. The adsorption configuration of single pyridine is atomically resolved and the S atoms in thiophenes are located after comparing imaging results with calculations. The strong interactions between molecules and acid sites can be visually studied in real-space images. This work provides a general strategy to directly observe these molecular structures and interactions in both the static image and the in situ experiment, expanding the applications of electron microscopy to the further study of various single-molecule behaviours with high resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Atomic imaging of single small molecules will provide new understanding of chemical bonds and intermolecular interactions1,2,3,4,5. Especially for catalysis and adsorption in porous materials, showing the host–guest interactions between small molecules and porous structures is of great importance to study various molecular behaviours in these applications. Electron microscopy is expected to achieve real-space characterizations of lattice structures with atomic resolution, which should also be applicable for imaging small molecules. Although recent progress on low-dose imaging methods indicates that it is technically feasible to observe small molecules by electron microscopy6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, it is still challenging to atomically resolve them for a deeper insight into chemistry.

Zeolite is one of the most important porous materials that is used in the conversion of natural gas, fossil oil and methanol into important olefins, aromatics and other fine chemicals14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The ordered channel system and well-defined acid sites in zeolites provide a strong confinement on adsorbed molecules to promote their further conversion, which has been studied by various experiments and simulations26,27,28,29,30. Meanwhile, the ‘frozen’ configurations of these molecules under the confinement conditions provide a basis for us to atomically image and study them in real space. For example, pyridine and thiophene are two typical probe molecules that can strongly interact with the Brønsted acid sites in zeolites. At the acid sites, the atomic rings in these molecules are statically exposed to a proper imaging projection, so that the molecular behaviours and interactions can be visually identified from the static images and even from an in situ experiment.

Here we use the pyridine and thiophene confined in zeolite ZSM-5 as model molecules to explore the application of imaging methods in molecular physics and chemistry. To atomically image these molecules, we apply iDPC-STEM23,24,25 to such beam-sensitive and light-element samples. During the in situ experiment, we can directly ‘see’ the adsorption and desorption behaviours of pyridines in the ZSM-5 channels. On the basis of static iDPC-STEM images, the six-membered ring in single pyridine and the S atom in single thiophene are located to reflect the host–guest interactions at the acid sites in ZSM-5 channels. These results demonstrate the ability of electron microscopy in the imaging and analysis of small molecules, and then inspire us to apply it to studying more single-molecule behaviours during adsorption, catalysis, gas separation and energy storage.

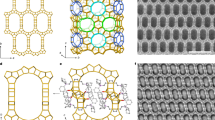

Figure 1a shows the schematics of in situ adsorption/desorption of pyridines in ZSM-5 and iDPC-STEM imaging. The T (Si or Al) and O sites in the ZSM-5 will form the cross-linked straight and sinusoidal channels with size 5.5 Å (ref. 22), which can just contain a single aromatic ring in each channel. The ZSM-5 samples we used have very thin areas with a thickness of 2–3 unit cells (4–6 nm) along the b-axis13 (Extended Data Fig. 1). On the basis of iDPC-STEM, empty ZSM-5 straight channels at these thin areas can be atomically imaged in the [010] projection (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, the Si/Al ratio of our samples is about 200, indicating only a small number of acid (Al) sites in the ZSM-5 framework. Thus most of the adsorption sites for pyridines are built only by Si and O atoms without acid (Al) sites. When pyridines were saturated in ZSM-5 channels in an in situ gas chamber (200 °C, 100 torr, gas: 1.5% pyridine and 98.5% N2), most of them were adsorbed and confined by pure van der Waals interactions. As simulated in Extended Data Fig. 2, these pyridines prefer a vertical configuration in ZSM-5 straight channels, which agrees with the simulations and imaging results in refs. 11,13,29. Figure 1c shows the iDPC-STEM image of such vertical pyridines in ZSM-5 channels after the in situ adsorption, and the spindle-shaped features appearing in channels reflect the pyridine columns (3–5 pyridines) along channels.

a, Schematics of in situ iDPC-STEM imaging of the pyridines adsorbed in ZSM-5 channels. b,c, iDPC-STEM images of empty ZSM-5 straight channels (b) and the channels after the saturated pyridine adsorption (c), compared with the structural models in the [010] projection. Scale bars, 1 nm. d, Calculated pyridine configurations in the channels with and without acid sites, respectively. After the acid site is set at O1 (as numbered), a protonated pyridine will bond with the acid site by electrostatic interaction.

If the T site is occupied by an Al atom to generate a bridging hydroxyl group (defined as the Brønsted acid site), the proton (H+) will be easily transferred to the N sites of pyridines. Then the negative zeolite and the protonated molecules are strongly bound by a short-range electrostatic interaction. In Fig. 1d, the non-equivalent O sites in a single unit cell of ZSM-5 are numbered, and the inside pyridine configurations were calculated. For the acid site at O1, the protonated pyridine shows a near-horizontal configuration with a ring structure. More calculated configurations with different positions of acid sites are given in Extended Data Fig. 3. However, owing to such a low density of acid sites in 4–6-nm thickness, a small amount of near-horizontal pyridine configurations, which can be observed in the [010] projection of ZSM-5, are just hidden in the overlapped contrasts of vertical configurations. Only if we remove the pyridines adsorbed by means of pure van der Waals interactions by heating samples at 200 °C in vacuum can the near-horizontal configurations of the left pyridines that were bonded more strongly with acid sites be eventually imaged (most probably as single pyridine left in each channel). This idea is consistent with the previous work of constructing and imaging a single para-xylene molecule compass13.

To further prove the reliability of this method, we achieved the in situ imaging of the adsorption and desorption processes of pyridines (as we mentioned above) by combining the atmosphere system with STEM. During the in situ experiment (see details in Methods), the empty ZSM-5 was studied first (named Stage 1). Then a gas mixture of 1.5% pyridine and 98.5% N2 was introduced for 5 min to fill the channels with pyridines (named Stage 2). Finally, the pyridines were gradually desorbed from the ZSM-5 after stopping the gas flow (named Stage 3). The iDPC-STEM images in Fig. 2a–d were captured near the same area of a ZSM-5 crystal. Figure 2a shows the ZSM-5 with empty channels in Stage 1 before gas introduction. Figure 2b reflects the saturated adsorption of pyridines in ZSM-5 in Stage 2 at 200 °C and 100 torr. As we described in Fig. 1c, the overlapped contrasts of the vertical pyridines are obvious at this stage. Figure 2c,d are two images captured continuously with a time interval of 3 min in Stage 3 (more images in Extended Data Fig. 4).

a–d, iDPC-STEM images of the same area in a ZSM-5 crystal captured during the in situ adsorption and desorption of pyridines. The conditions in the in situ gas chip are 200 °C, 100 torr, gas: 1.5% pyridine and 98.5% N2. Stage 1: empty ZSM-5 (a); Stage 2: the ZSM-5 after saturated pyridine adsorption (b); Stage 3: the ZSM-5 during pyridine desorption (c and d, time interval: 3 min). Scale bars, 5 nm. e, Magnified iDPC-STEM images of four channels extracted from a–d (marked by the coloured circles), indicating the changes of pyridine configurations in different stages. Scale bar, 0.5 nm.

During the pyridine desorption, we find that the contrasts of pyridine features decreased and the empty channels were observed again, indicating the removal of pyridines inside (as shown in the statistics in Extended Data Fig. 5). The ring structures appeared in some channels representing the near-horizontal pyridine configurations that were stabilized by the stronger acid–base bonding in Stage 3. Such desorption behaviours were also confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and in situ infrared (IR) spectroscopy of the pyridine desorption process (Extended Data Fig. 6). Then we selected four channels (marked by the coloured circles in Fig. 2a–d) to track the changes in the configurations of confined pyridines. The magnified images are summarized in Fig. 2e. The channels in the red and yellow circles showed clear ring structures early or late. The sizes of these ring structures are consistent with the theoretical distances between opposite atoms in aromatic rings (2.73–2.77 Å). The pyridines in the cyan channel were desorbed before capturing Fig. 2c, whereas there were still some pyridines left in the blue channel when capturing Fig. 2d (but with lower contrast than at the beginning).

Although we have shown the adsorption/desorption behaviours of pyridines by in situ STEM, it is still challenging to atomically resolve the pyridine configurations because the windows and gas in the in situ chip affect the electron scattering for high-quality imaging. Therefore, we performed exactly the same procedure on the pyridine/ZSM-5 sample outside the scanning transmission electron microscope and characterized it in the scanning transmission electron microscope with a rotatable double-tilt holder for better imaging. Here pyridines were adsorbed into ZSM-5 channels from the liquid phase. After heating at 200 °C, compared with the as-prepared sample without heating (Extended Data Fig. 7), there are obviously more empty channels and more channels with near-horizontal pyridines. It is worth noting that the image will also be blurred by noise and thermal vibration (as discussed in Extended Data Fig. 8), so that not all pyridines can be atomically resolved and some of them are roughly identified as unclear rings or round features.

We choose a Gaussian-filtered image of pyridine configuration with a perfect ring feature (Fig. 3a) to further analyse its atomic structure. Six red dots were used to mark out the projected positions of C or N atoms in this pyridine (Fig. 3b). To confirm this pyridine structure, we calculated the probable configurations of a single pyridine when setting the acid sites at ten different O atoms (Extended Data Fig. 3). Among them, we find the calculated structure closest to our observation and the corresponding simulated iDPC-STEM image in Fig. 3c,d. In this structure, the acid site is located at O2 (the O atom between T1 and T2). Our method to find this closest model is based on the determination of atom coordinates in this pyridine. The x-axis, y-axis and coordinate origin (x = 0, y = 0) are given in both Fig. 3b,c. The coordinates of six atoms in the iDPC-STEM image and all ten models in Extended Data Fig. 3 are given in Extended Data Table 1. The atomic coordinates in the closest model show slight errors within 2 pixels compared with the experimental results (Fig. 3e). A least-squares fitting in Fig. 3f provides the position errors of six atoms in all models, in which the lowest error occurs when we set the acid site at O2.

a, Magnified iDPC-STEM image of a near-horizontal pyridine with an obvious ring structure in the ZSM-5 channel. Scale bar, 0.5 nm. b, Marks for the C or N atoms (red dots) and the positions of intensity profiles (red arrow). c, Calculated structural model of a pyridine in the ZSM-5 channel that is closest to our observation in a. The acid site is set at O2. d, Simulated iDPC-STEM image based on the model in c. e, Atom coordinates of pyridines in the iDPC-STEM image (b) and calculated model (c). The x-axis, y-axis and coordinate origin are also given in b and c. f, Least-squares fitting of the pyridine position in the iDPC-STEM image (b) with those in all calculated models (Extended Data Fig. 3), indicating that the acid site is most probably at O2. g, Intensity profiles of the experimental (solid line) and simulated (dashed line) iDPC-STEM images. The positions of intensity profiles are given in b. The projected distances between opposite atoms on this pyridine ring were measured in the experimental profile to atomically locate the pyridine structure and show the acid–base interaction.

Then we use the profile analysis of the experimental and simulated images to resolve this pyridine structure (Fig. 3g). The intensity profile is extracted from the area marked by the red arrow in Fig. 3b. The solid line is the experimental intensity profile and the dashed line is the simulated one. In these profiles, the higher peaks on both sides indicate the Si and O atoms in the ZSM-5 framework and the lower peaks in the centre indicate the C and N atoms on this pyridine ring. The positions of all the atom peaks in the experimental profile agree with those in the simulation. More profiles are given in Extended Data Fig. 9, including those in raw images, to demonstrate the consistency between the experimental and simulated results. The peak intervals reflect the projected distances between these atom columns along the direction of this profile. For example, the measured distance between the probable C and N peaks (2.26 Å, 9 pixels) may indicate the size of the pyridine projection, whereas that between the probable N and O peaks (2.51 Å, 10 pixels) may provide the length of N–H–O bonding, which helps to show visually this host–guest interaction in the real space.

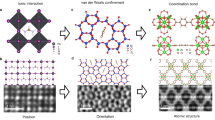

However, it must be noted that the models with acid sites at O8, O13 and O15 also show some similarity to the experimental results as shown in Fig. 3f. Determination of pyridine configuration provides the most probable position of the acid site but cannot completely rule out other possibilities. One of the main technical limits is that there is no way to identify the N element in pyridine in the image with such high resolution. Because the intensity of the iDPC-STEM image is roughly proportional to the atomic number23,24,25, replacing the N atom (Z = 7) by an active site with a larger atomic number makes it possible to directly distinguish this active site from other C atoms (Z = 6) in the image. To fully illustrate the extensibility and further applications of the imaging method, we try to visualize another probe molecule, thiophene, to study the strong bonding between the S atom and the acid site. Figure 4a shows one of the simulated configurations of thiophenes in ZSM-5 channels. More results after changing the positions of acid sites are given in Extended Data Fig. 10. In all these models, the S atoms (Z = 16), which have an obviously larger atomic number than C atoms, point to the acid sites, owing to the directional interaction. Therefore it is possible to locate only a single S atom by the image contrast to study the acid site, rather than having to locate all atoms, such as for pyridines.

a, Schematics of a thiophene bonding with the acid site. b, iDPC-STEM image of the thiophene/ZSM-5 sample prepared outside the scanning transmission electron microscope. Scale bar, 2 nm. c, d, Magnified iDPC-STEM images of two thiophenes in the ZSM-5 channels (extracted from the red and blue boxes in b) showing clear ring structures. Scale bar, 0.5 nm. e, Intensity profiles showing different intensities of S and C atoms in c and d. The red and blue profiles are taken along the red and blue arrows in c and d, respectively. f, Errors of the S positions between ten simulated models and the imaged results in c (red points) and d (blue points). By comparing the S positions in the calculations and images, the models closest to the imaging results in c and d show the acid sites at O19 and O8, respectively. g,h, Calculated structural models and simulated iDPC-STEM images of the thiophenes that are closest to our observations in c and d. The acid sites are set at O19 and O8.

Figure 4b shows the iDPC-STEM image of the thiophene/ZSM-5 sample that was treated in the same way as the pyridine/ZSM-5 sample outside the scanning transmission electron microscope to obtain a single molecule in each channel. We selected two channels marked by the red and blue boxes as examples to analyse the interactions between thiophenes and acid sites (as shown in Fig. 4c,d). In these iDPC-STEM images, we can identify the S atoms in ring structures owing to their higher intensities. As shown in the intensity profiles in Fig. 4e (extracted from the red and blue arrows in Fig. 4c,d), the peaks of S atoms form an obvious intensity difference compared with those of C atoms, so that they can be precisely located in these images. Especially in the red profile, the projected distance between the S and O atoms was measured as 3.27 Å (13 pixels), which is nearly consistent with the theoretical value of 3.19 Å. In the same coordinate system as Fig. 3, the coordinates of S atoms in the images and the ten calculated models in Extended Data Fig. 10 are given in Extended Data Table 2. According to the calculated errors of S positions in Fig. 4f, we select two probable thiophene configurations from Extended Data Fig. 10 (with acid sites at O19 and O8) that are closest to our observations in Fig. 4c,d. The corresponding models and simulated iDPC-STEM images are shown in Fig. 4g,h and the simulated profiles are compared with the experimental ones in Extended Data Fig. 9.

Throughout the whole idea of this work, we used a complete in situ experiment and detailed analysis of a single static image to demonstrate the effectiveness of iDPC-STEM for atomic single-molecule imaging. Through the direct structural identification of the single molecules and atoms in high-resolution images, we try to visually understand the adsorption behaviours and host–guest interactions of small molecules in porous zeolites. As we emphasized above, there is still a long way to go to atomically observe the configurations of confined molecules in all channels to obtain a statistical result on the basis of a large number of data, as the effect of Poisson noise on ultra-thin samples cannot be ignored at such an electron dose. Although the method of locating S atoms in thiophenes allows us to reduce the requirements of image signal-to-noise ratio to a certain extent, the problem still exists for further detailed analysis. Therefore, we must further consider how to balance the electron dose and signal-to-noise ratio or find a new pathway to solve the contradiction between them. Nevertheless, this work represents an important technological breakthrough in electron microscopy and a solid step forward to the study of host–guest interactions and single-molecule behaviours in porous materials by a real-space imaging method. Notably, these interactions and behaviours can be imaged at room temperature and even higher temperatures during the in situ experiments, in which their configurations are indeed closer to their real states in catalysis, adsorption, gas separation and energy storage. It will greatly expand the applications of electron microscopy to visualizing single small molecules to show the molecular mechanism in these important unit processes.

Methods

Synthesis of ZSM-5 crystals with thin areas

The ZSM-5 crystals with thin areas (Si/Al ≈ 200) were prepared by means of a hydrothermal method. During the synthesis, we used tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH) as structure-directing agent and tetraethyl orthosilicate and Al(NO3)3·9H2O as the main reactants. In a typical synthesis, 26.2 g TPAOH, 22.4 g tetraethyl orthosilicate, 4.0 g urea, 0.2 g Al(NO3)3·9H2O, 0.2 g NaOH and 0.2 g isopropanol were stirred in 36.8 g H2O for 2 h at room temperature. Then the temperature-programming crystallization was conducted in a Teflon-lined autoclave. The temperature programme was set to increase from 30 to 180 °C for 48 h and remain at 180 °C for 48 h. After that, the crystallization was quenched by cold water. The solid products after filtering and washing were calcined at 550 °C to remove the TPAOH template. Finally, the H-ZSM-5 samples were obtained from the Na-ZSM-5 samples by ion exchange. The ZSM-5 samples we used in this work are all H-ZSM-5 forms.

Adsorption of pyridine and thiophene molecules

Pyridine and thiophene molecules were absorbed in the ZSM-5 channels directly from their liquid phase. Some of them strongly interact with the acid sites in ZSM-5. As-prepared ZSM-5 powder is dispersed in the pyridine and thiophene liquid by ultrasound for 30 min. Then the samples were transferred to microgrids for STEM imaging. To remove the pyridines and thiophenes adsorbed only by van der Waals interactions, the samples were further heated to 200 °C for 1 h.

Imaging conditions and simulations

The iDPC-STEM imaging was conducted in a Cs-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (FEI Titan Cubed Themis G2 300) operated at 300 kV. This microscope is equipped with a DCOR+ spherical aberration corrector for the electron probe, which was aligned with proper aberration coefficients using a standard gold sample. The convergence semi-angle is 15 mrad. The collection angle is 3–18 mrad. The beam current is about 0.07–0.1 pA (measured by a pixel array detector). The dwell time for each pixel is 128 μs. The pixel size is 0.2514 × 0.2514 Å2. The iDPC-STEM images were usually filtered by a Gaussian filter with a sigma of 20, which is a common image-processing step directly conducted in Velox software.

During the in situ experiment, the ZSM-5 sample was packaged in an in situ gas chip (Atmosphere system, Protochips), which enables us to study various dynamic nanoscale processes under realistic conditions in the scanning transmission electron microscope. First the sample was put in vacuum (window pressure 1 torr) and heated at 650 °C for 3 h to remove the impurities in the ZSM-5 channel (Stage 1). The conditions for observing in situ pyridine adsorption (Stage 2) are: temperature: 200 °C, pressure: 100 torr, gas mixing ratio: 1.5% pyridine and 98.5% N2 (the mixing ratio was determined according to the saturated vapour pressure of pyridine). After the ZSM-5 was exposed to pyridine gas for 5 min, the adsorbed pyridines in the ZSM-5 were saturated. Then the injection of pyridine was stopped. After the sample was purged with N2 three times, the desorption process of pyridines in ZSM-5 was observed at 200 °C (Stage 3).

The iDPC-STEM simulations were conducted on the basis of the multislice method31, which can be extended to support iDPC-STEM imaging, as explained in previous works32,33. Considering the convergence angle of the beam (15 mrad), the thickness of the sample of two unit cells (4 nm) and the fact that it consists of mostly Si/Al and light elements, this sample can be considered thin34. We used the same convergence angle and collection angle as in the experiments. In the simulations, four images were separately collected by four segments of the DF4 detector and then integrated into the simulated iDPC-STEM images. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 8, thermal vibration was considered on the basis of the effect of thermal diffuse scattering (TDS), whereas shot noise was considered on the basis of the Poisson distribution, which were both added to four separate images directly.

First-principles calculations

All periodic first-principles calculations were carried out using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional in the generalized gradient approach, as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP 5.4.4)35,36. The expansion valence density was based on a plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cut-off of 450 eV and the projected augmented wave formalism was used to consider the influence of the core and valence electrons in the valence density37. Brillouin zone sampling was carried out at the Γ point. For all structure optimizations, the energy and force convergence criteria were 1.0 × 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV Å−1, respectively. A periodic siliceous MFI structure of Si96O192 with lattice parameters of 20.02 × 19.9 × 13.38 Å3 was used. The unit cell of the ZSM-5 was built by replacing one T-site Si atom with an Al atom. A charge-balancing proton was added on the most stable adjacent oxygen, which is a close neighbour of the Al atom, yielding the Brønsted acid sites (O–Si–O(H)–Al–O).

The long-range van der Waals dispersion interactions between guest molecules (pyridine and thiophene) and the zeolite framework was compensated using the DFT-D3 scheme38,39. For pyridines, the protons on acid sites were fully transferred onto the N sites in pyridines and the zeolite became negative. The interaction energy of the small molecule (M) in the ZSM-5 channel (EIN) is defined as the energy difference between the total energy (EM+ZSM-5) and the sum of the energies of the free molecule (EM) and empty ZSM-5 (EZSM-5), which was calculated as EIN = EM+ZSM-5 − EM − EZSM-5. Each calculated configuration in Extended Data Figs. 3 and 10 was found to have the lowest interaction energy with each position of acid site. The coordinates of atoms can be obtained in the calculated models after choosing given x and y axes. For the pyridine in Fig. 3, the coordinates of all six atoms in the ten calculated models and iDPC-STEM image are given in Extended Data Table 1. The sum of squares of position errors in Fig. 3f was calculated as (x1m − x1i)2 + (y1m − y1i)2 + (x2m − x2i)2 + (y2m − y2i)2 + (x3m − x3i)2 + (y3m − y3i)2 + (x4m − x4i)2 + (y4m − y4i)2 + (x5m − x5i)2 + (y5m − y5i)2 + (x6m − x6i)2 + (y6m − y6i)2, in which (xnm, ynm) (n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) are the atomic coordinates in the models and (xni, yni) (n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) are the atomic coordinates in the iDPC-STEM image. For the thiophenes in Fig. 4, the coordinates of S atoms in the ten calculated models and iDPC-STEM image are given in Extended Data Table 2. The distance between the S atoms in the models and image shown in Fig. 4f was calculated as [(xSm − xSi)2 + (ySm − ySi)2]1/2, in which (xSm, ySm) and (xSi, ySi) are the coordinates of the S atoms in the models and image, respectively.

Other characterizations

The annular dark-field STEM imaging was also conducted in the same Cs-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (FEI Titan Cubed Themis G2 300) operated at 300 kV. The convergence semi-angle is 23.6 mrad. The collection angle is 51–200 mrad. The beam current is 50 pA. The dwell time is 16 μs per pixel.

The elemental mapping was obtained by energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) in the same Cs-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (FEI Titan Cubed Themis G2 300). The beam current is set between 10 and 15 pA to minimize damage to the specimens. The dwell time is 4 µs per pixel, with a map size of 256 × 256 pixels. The EDS data were integrated in Velox software. Multi-polynomial and Brown–Powell models were used to correct the background and quantify the EDS data. The specimen tilt correction was applied automatically in Velox software.

Thickness mapping by electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) was performed using another Cs-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (JEM-ARM200F) operated at 200 kV. The convergence semi-angle of EELS mapping was 28 mrad. The collection angle of EELS mapping was 0–25 mrad.

The position-averaged convergent beam electron diffraction (PACBED) pattern40 was acquired at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV with a convergence semi-angle of 10 mrad. During data acquisition, the beam was scanned continuously over an area of around 2 × 2 unit cells and the PACBED pattern was recorded on a BM-Ceta camera (512 × 512 pixels). The recording time for each pattern was 8 s, at a beam current of about 1 pA. Then the theoretical PACBED patterns of ZSM-5 crystals were simulated with the MuSTEM multislice simulation code41. The simulations for different thicknesses were performed using the same parameters as in the experiments.

IR spectroscopy of pyridine adsorption was conducted to quantitatively identify the pyridines absorbed on Brønsted acid sites and Lewis acid sites in ZSM-5. About 100 mg of the sample was tableted and placed in the in situ cell, pretreated under vacuum (less than 10−3 Pa) at 500 °C for 60 min. After cooling to 100 °C, the samples were exposed to pyridine molecules for 1 h to be saturated. Subsequently, the in situ cell was evacuated to vacuum (10−4 Pa) and the spectra were recorded at 200 and 350 °C, respectively. The scanning range was about 1,000–4,000 cm−1.

The TGA measurements were carried out to elaborate the desorption behaviours of the pyridines absorbed in ZSM-5 using Pyris Diamond TG-DTG. Samples were first degassed in vacuum at 500 °C and then impregnated with pyridine liquid. Subsequently, the wet mixture was transferred to a crucible for TGA analysis. The Ar gas flow rate was set at 50 sccm. First, the temperature was increased from ambient temperature to 120 °C (higher than the boiling point of pyridine) at a rate of 10 K min−1 and kept at 120 °C for 60 min to completely remove the liquid pyridine molecules. Then the temperature was increased from 120 to 600 °C at a rate of 5 K min−1.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Temirov, R., Soubatch, S., Luican, A. & Tautz, F. S. Free-electron-like dispersion in an organic monolayer film on a metal substrate. Nature 444, 350–353 (2006).

Gross, L., Mohn, F., Moll, N., Liljeroth, P. & Meyer, G. The chemical structure of a molecule resolved by atomic force microscopy. Science 325, 1110–1114 (2009).

Gross, L. et al. Organic structure determination using atomic-resolution scanning probe microscopy. Nat. Chem. 2, 821–825 (2010).

Weiss, C., Wagner, C., Temirov, R. & Tautz, F. S. Direct imaging of intermolecular bonds in scanning tunneling microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11864–11865 (2010).

Zhang, J. et al. Real-space identification of intermolecular bonding with atomic force microscopy. Science 342, 611–614 (2013).

Koshino, M. et al. Imaging of single organic molecules in motion. Science 316, 853 (2007).

Liu, Z., Yanagi, K., Suenaga, K., Kataura, H. & Iijima, S. Imaging the dynamic behaviour of individual retinal chromophores confined inside carbon nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2, 422–425 (2007).

Zhang, D. et al. Atomic-resolution transmission electron microscopy of electron beam-sensitive crystalline materials. Science 359, 675–679 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Cryo-EM structures of atomic surfaces and host-guest chemistry in metal-organic frameworks. Matter 1, 428–438 (2019).

Shen, B., Chen, X., Shen, K., Xiong, H. & Wei, F. Imaging the node-linker coordination in the bulk and local structures of metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 11, 2692 (2020).

Shen, B. et al. Atomic spatial and temporal imaging of local structures and light elements inside zeolite frameworks. Adv. Mater. 32, 1906103 (2020).

Yuan, W. et al. Visualizing H2O molecules reacting at TiO2 active sites with transmission electron microscopy. Science 367, 428–430 (2020).

Shen, B. et al. A single-molecule van der Waals compass. Nature 592, 541–544 (2021).

Corma, A. From microporous to mesoporous molecular sieve materials and their use in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 97, 2373–2419 (1997).

Davis, M. E. Ordered porous materials for emerging applications. Nature 417, 813–821 (2002).

Li, Y. & Yu, J. New stories of zeolite structures: their descriptions, determinations, predictions, and evaluations. Chem. Rev. 114, 7268–7316 (2014).

Corma, A. Inorganic solid acids and their use in acid-catalyzed hydrocarbon reactions. Chem. Rev. 95, 559–614 (1995).

Busca, G. Acid catalysts in industrial hydrocarbon chemistry. Chem. Rev. 107, 5366–5410 (2007).

Yilmaz, B. & Müller, U. Catalytic applications of zeolites in chemical industry. Top. Catal. 52, 888–895 (2009).

Rinaldi, R. & Schuth, F. Design of solid catalysts for the conversion of biomass. Energy Environ. Sci. 2, 610–626 (2009).

Olsbye, U. et al. The formation and degradation of active species during methanol conversion over protonated zeotype catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 7155–7176 (2015).

Kokotailo, G. T., Lawton, S. L., Olson, D. H., Olson, D. H. & Meier, W. M. Structure of synthetic zeolite ZSM-5. Nature 272, 437–438 (1978).

Lazic, I., Bosch, E. G. T. & Lazar, S. Phase contrast STEM for thin samples: integrated differential phase contrast. Ultramicroscopy 160, 265–280 (2016).

Lazić, I. & Bosch, E. G. T. Analytical review of direct STEM imaging techniques for thin samples. Adv. Imaging Electron Phys. 199, 75–184 (2017).

Yucelen, E., Lazic, I. & Bosch, E. G. T. Phase contrast scanning transmission electron microscopy imaging of light and heavy atoms at the limit of contrast and resolution. Sci. Rep. 8, 2676 (2018).

Borade, R. B., Adnot, A. & Kaliaguine, S. Acid sites in dehydroxylated Y zeolites: an X-ray photoelectron and infrared spectroscopic study using pyridine as a probe molecule. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 86, 3949–3956 (1990).

Zhang, W., Cu, S., Han, X. & Bao, X. In situ solid-state NMR for heterogeneous catalysis: a joint experimental and theoretical approach. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 192–210 (2012).

Paul, G. et al. Combined solid-state NMR, FT-IR and computational studies on layered and porous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 5684–5739 (2019).

Boronat, B. & Corma, A. What is measured when measuring acidity in zeolites with probe molecules? ACS Catal. 9, 1539–1548 (2019).

Liu, L. et al. Direct imaging of atomically dispersed molybdenum that enables location of aluminum in the framework of zeolite ZSM-5. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 819–825 (2019).

Kirkland, E. J. Advanced Computing in Electron Microscopy (Springer, 2010).

Lazić, I. & Bosch, E. G. T. Analytical review of direct STEM imaging techniques for thin samples. Adv. Imaging Electron Phys. 199, 75–184 (2017).

Bosch, E. G. T. & Lazić, I. Analysis of HR-STEM theory for thin specimen. Ultramicroscopy 156, 59–72 (2015).

Bosch, E. G. T. & Lazić, I. Analysis of depth-sectioning STEM for thick samples and 3D imaging. Ultramicroscopy 207, 112831 (2019).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Grimme, S. Accurate description of van der Waals complexes by density functional theory including empirical corrections. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1463–1473 (2004).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

LeBeau, J. M., Findlay, S. D., Allen, L. J. & Stemmer, S. Position averaged convergent beam electron diffraction: theory and applications. Ultramicroscopy 110, 118–125 (2010).

Allen, L. J., D’Alfonso, A. J. & Findlay, S. D. Modelling the inelastic scattering of fast electrons. Ultramicroscopy 151, 11–22 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2020YFB0606401), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 22005170, 21771029 and 202013981) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFB0602204). We are grateful to the Tsinghua National Laboratory for Information Science and Technology for assistance with the energy simulation. B.S. is also thankful for the support from Suzhou Key Laboratory of Functional Nano & Soft Materials, Collaborative Innovation Center of Suzhou Nano Science & Technology, the 111 Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S., X.C. and F.W. conceived this project and designed the studies; B.S. and X.C. performed the electron microscopy experiments and data analysis; H.W. prepared the zeolite samples and carried out the first-principles calculations; H.X., E.G.T.B. and I.L. performed the simulation of iDPC-STEM images; all authors were involved in the data analysis; B.S. wrote the manuscript, with the help of the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Hamish Brown and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Extended data

is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04876-x.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Thin (quasi-2D) areas in ZSM-5 crystal.

a, Annular dark-field STEM image showing the lateral view of the thin area in ZSM-5 crystal. The thickness of the thin area is about 4 nm, which can be measured from this lateral view. b,c, Thickness mapping and profile analysis by EELS. The measured thickness of this thin area is also about 4 nm. d, PACBED pattern at the thin area of ZSM-5 crystal. The simulated pattern for a sample thickness of 6 nm is given to compare with the experimental result. e, Profile analysis of the experimental and simulated PACBED patterns to estimate the thickness of this thin area. The position of profiles is given in d. The inset shows the least-squares fitting of the experimental PACBED pattern with the simulated ones, indicating that this area is about 6 nm thick.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Analysis of empty channel and vertical pyridine.

a, Structural model, simulated and experimental images of an empty ZSM-5 channel. b, Structural model, simulated and experimental images of the ZSM-5 channel with a vertical pyridine (without acid sites).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Calculated near-horizontal pyridine configurations.

a, Numbered T and O sites in the ZSM-5 (MFI) framework. b–k, Calculated structural models of pyridine molecules with the lowest interaction energy when bonding with different acid sites. Here we only show these ten acid site positions, because for other positions pyridines will be adsorbed into sinusoidal channels that cannot be imaged from this [010] projection. The stable pyridine configuration in c, when setting the acid site at O2, is consistent with the imaged results in Fig. 3.

Extended Data Fig. 4 More images in Stage 3 of the in situ experiment.

The iDPC-STEM images are continuously captured at different times during the desorption of pyridines (Stage 3).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Statistics of pyridine features in each channel after heat treatment.

There are about 45% empty channels, about 33% channels with near-horizontal pyridines and about 22% channels with vertical pyridines.

Extended Data Fig. 6 TGA and IR spectroscopy of the pyridines in ZSM-5.

a, TGA result of the pyridine/ZSM-5 sample. The sample stays at 120 °C (boiling point of pyridine) for 1 h to completely remove bulk or surface pyridines. The inset shows the peaks of pyridine desorption. At around 200 °C, most of the pyridines adsorbed mainly by van der Waals interactions were desorbed, whereas the remaining pyridines strongly bonding with the acid sites were also desorbed at over 300 °C. b, IR spectroscopy of protonated pyridines bonding with the acid sites at 200 and 350 °C. The peak at about 1,540 cm−1 indicates the N–H bonds in the protonated pyridines, which strongly interact with the Brønsted acid sites. This result shows that, in this temperature range, there are still some protonated pyridines (with near-horizontal configurations) confined in ZSM-5 channels.

Extended Data Fig. 7 iDPC-STEM images of the pyridine/ZSM-5 samples through heating.

a, iDPC-STEM image before heating (saturated van der Waals adsorption). b, iDPC-STEM image after heating at 200 °C outside the scanning transmission electron microscope. c, Different kinds of pyridine configuration in ZSM-5 channels after heating. More magnified iDPC-STEM images of the near-horizontal pyridine configurations are given, the sizes of which agree with the model of pyridine molecules.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Effects of thermal vibration and noise on iDPC-STEM images.

a, Effect of thermal vibration on iDPC-STEM images studied by image simulations. The sigma of TDS ranges from 0.1 to 0.5. b, Effect of Poisson noise on iDPC-STEM images studied by image simulations. The electron doses in the simulations are 1,500 and 3,000 e− Å−2, respectively. The thickness is 4 nm (2-unit-cell thickness). c, Simulated image with no TDS and noise with a profile direction (white arrow) for the profile analysis in d and e. d,e, Profile analysis to show the effects of thermal vibration and noise on iDPC-STEM images.

Extended Data Fig. 9 More profile analysis of the single molecules in ZSM-5 channel.

a–d, Comparison between the raw (a), Gaussian-filtered (b and d) and simulated (c) images of the pyridine discussed in Fig. 3. e,f, Profile analysis of these images to demonstrate the consistency of the experimental and simulated results. Two profile directions are marked by the red and blue arrows in d. g,h, Structural models and simulated images of two thiophenes discussed in Fig. 4. i,j, Profile analysis of the experimental and simulated images. Two profile directions are marked by the red and blue arrows in g and h.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Calculated near-horizontal thiophene configurations.

a, Numbered T and O sites in ZSM-5 (MFI) framework. b–k, Calculated structural models of thiophene molecules with the lowest interaction energy when bonding with different acid sites. Here we only show these ten acid site positions, because for other positions thiophene will be adsorbed into sinusoidal channels that cannot be imaged from this [010] projection. The S atoms in thiophenes are just pointing to acid sites to identify the positions of these acid sites. The thiophene configurations in e and i, when setting the acid site at O8 and O19, are consistent with the imaged results in Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, B., Wang, H., Xiong, H. et al. Atomic imaging of zeolite-confined single molecules by electron microscopy. Nature 607, 703–707 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04876-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04876-x

This article is cited by

-

Real space characterizations of catalysts by advanced transmission electron microscopy

Science China Chemistry (2026)

-

Decoupling photothermal-mechanical degradation through lattice-stabilizing networks in Sn–Pb perovskites and all-perovskite tandem solar cells

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Imaging molecular structures and interactions by enhanced confinement effect in electron microscopy

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Lattice stabilization and strain homogenization in Sn-Pb bottom subcells enable stable all-perovskite tandems solar cells

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Ion desolvation for boosting the charge storage performance in Ti3C2 MXene electrode

Nature Communications (2025)