Abstract

Recent breakthroughs in ultrathin, single-crystalline, freestanding complex oxide systems have sparked industry interest in their potential for next-generation commercial devices1,2. However, the mass production of these ultrathin complex oxide membranes has been hindered by the challenging requirement of inserting an artificial release layer between the epilayers and substrates3,4. Here we introduce a technique that achieves atomic precision lift-off of ultrathin membranes without artificial release layers to facilitate the high-throughput production of scalable, ultrathin, freestanding perovskite systems. Leveraging both theoretical insights and empirical evidence, we have identified the pivotal role of lead in weakening the interface. This insight has led to the creation of a universal exfoliation strategy that enables the production of diverse ultrathin perovskite membranes less than 10 nm. Our pyroelectric membranes demonstrate a record-high pyroelectric coefficient of 1.76 × 10−2 C m−2 K−1, attributed to their exceptionally low thickness and freestanding nature. Moreover, this method offers an approach to manufacturing cooling-free detectors that can cover the full far-infrared spectrum, marking a notable advancement in detector technology5.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Code availability

All data from this study are included in the paper and are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Meng, Y. et al. Photonic van der Waals integration from 2D materials to 3D nanomembranes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 498–517 (2023).

Ji, J., Park, S., Do, H. & Kum, H. S. A review on recent advances in fabricating freestanding single-crystalline complex-oxide membranes and its applications. Phys. Scr. 98, 052002 (2023).

Lu, D. et al. Synthesis of freestanding single-crystal perovskite films and heterostructures by etching of sacrificial water-soluble layers. Nat. Mater. 15, 1255–1260 (2016).

Kum, H. S. et al. Heterogeneous integration of single-crystalline complex-oxide membranes. Nature 578, 75–81 (2020).

Fraden, J. in Handbook of Modern Sensors: Physics, Designs, and Applications, 525–567 (Springer, 2016).

Shi, Q. et al. The role of lattice dynamics in ferroelectric switching. Nat. Commun. 13, 1110 (2022).

Brewer, A. et al. Microscopic piezoelectric behavior of clamped and membrane (001) PMN-30PT thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 202903 (2021).

Pesquera, D. et al. Large magnetoelectric coupling in multiferroic oxide heterostructures assembled via epitaxial lift-off. Nat. Commun. 11, 3190 (2020).

Han, S. et al. High energy density in artificial heterostructures through relaxation time modulation. Science 384, 312–317 (2024).

Pesquera, D., Fernández, A., Khestanova, E. & Martin, L. W. Freestanding complex-oxide membranes. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 383001 (2022).

Huang, J.-K. et al. High-κ perovskite membranes as insulators for two-dimensional transistors. Nature 605, 262–267 (2022).

Bhan, R. K. & Dhar, V. Recent infrared detector technologies, applications, trends and development of HgCdTe based cooled infrared focal plane arrays and their characterization. Opto-Electron. Rev. 27, 174–193 (2019).

Rogalski, A. W., Kopytko, M. E. & Martyniuk, P. M. Antimonide-Based Infrared Detectors: A New Perspective (SPIE Press, 2018).

Kum, H. et al. Epitaxial growth and layer-transfer techniques for heterogeneous integration of materials for electronic and photonic devices. Nat. Electron. 2, 439–450 (2019).

Chiabrera, F. M. et al. Freestanding perovskite oxide films: Synthesis, challenges, and properties. Ann. Phys. 534, 2200084 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Super-tetragonal Sr4Al2O7 as a sacrificial layer for high-integrity freestanding oxide membranes. Science 383, 388–394 (2024).

Varshney, S. et al. Hybrid molecular beam epitaxy for single-crystalline oxide membranes with binary oxide sacrificial layers. ACS Nano 18, 6348–6358 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Remote epitaxy through graphene enables two-dimensional material-based layer transfer. Nature 544, 340–343 (2017).

Jiang, J. et al. Giant pyroelectricity in nanomembranes. Nature 607, 480–485 (2022).

Nix, W. D. Mechanical properties of thin films. Metall. Trans. A 20, 2217–2245 (1989).

Liu, D. & Pons, D. J. Crack propagation mechanisms for creep fatigue: A consolidated explanation of fundamental behaviours from initiation to failure. Metals 8, 623 (2018).

Suo, Z. & Hutchinson, J. W. Steady-state cracking in brittle substrates beneath adherent films. Int. J. Solids Struct. 25, 1337–1353 (1989).

Coll, P. G., Meier, R. & Bertoni, M. Dynamics of crack propagation during silicon spalling. In 2018 IEEE 7th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC) (A Joint Conference of 45th IEEE PVSC, 28th PVSEC and 34th EU PVSEC), 2537–2539 (IEEE, 2018).

Park, H. et al. Analytic model of spalling technique for thickness-controlled separation of single-crystalline semiconductor layers. Solid-State Electron. 163, 107660 (2020).

Park, H. et al. Investigation of electrical characteristics of flexible CMOS devices fabricated with thickness-controlled spalling process. Solid-State Electron. 173, 107901 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Controlled spalling and flexible integration of PZT film based on LaNiO3 buffer layer. Ceram. Int. 45, 6373–6379 (2019).

Wen, J. et al. Advances in far-infrared research: therapeutic mechanisms of disease and application in cancer detection. Lasers Med. Sci. 39, 41 (2024).

Tang, Y. & Luo, H. Investigation of the electrical properties of (1 − x)Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3–xPbTiO3 single crystals with special reference to pyroelectric detection. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 42, 075406 (2009).

Lubomirsky, I. & Stafsudd, O. Invited review article: practical guide for pyroelectric measurements. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83, 051101 (2012).

Karthik, R. et al. Highly sensitive pyroelectric detector using atomically thin nanoscale silicon ditelluride. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 10168–10177 (2023).

Niu, L. et al. Controlled synthesis and room-temperature pyroelectricity of CuInP2S6 ultrathin flakes. Nano Energy 58, 596–603 (2019).

Neumann, N., Kaiser, A. & Mutschall, D. Advantages and limitation of Mn doped PIN–PMN–PT single crystals in pyroelectric detectors. APL Mater. 9, 021106 (2021).

Felix, P., Gamot, P., Lacheau, P. & Raverdy, Y. Pyroelectric, dielectric and thermal properties of TGS, DTGS and TGFB. Ferroelectrics 17, 543–551 (1977).

Zhao, J. et al. Surface and thickness effect on the ferroelectric, dielectric and pyroelectric properties of Mn-doped Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3–0.28PbTiO3 single crystals. J. Alloys Compd. 816, 152500 (2020).

Glass, A. M. Investigation of the electrical properties of Sr1−xBaxNb2O6 with special reference to pyroelectric detection. J. Appl. Phys. 40, 4699–4713 (1969).

Shen, M. et al. High room-temperature pyroelectric property in lead-free BNT-BZT ferroelectric ceramics for thermal energy harvesting. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 39, 1810–1818 (2019).

Leppävuori, S., Łoziński, A. & Uusimaki, A. A thick-film pyroelectric PLZT ceramic sensor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 47, 391–394 (1995).

Sengupta, S., Sengupta, L. C., Synowczynski, J. & Rees, D. A. Novel pyroelectric sensor materials. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 45, 1444–1452 (1998).

Lee, J. S. et al. Preparation of (Ba, Sr)TiO3 thin films with high pyroelectric coefficients at ambient temperatures. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 38, L574–L576 (1999).

Zhang, Q. & Whatmore, R. Sol-gel PZT and Mn-doped PZT thin films for pyroelectric applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 34, 2296–2301 (2001).

Irzaman, Y. D., Fuad, A., Arifin, P., Budiman, M. & Barmawi, M. Physical and pyroelectric properties of tantalum‐oxide‐doped lead zirconium titanate [Pb0.9950(Zr0.525Ti0.465Ta0.010)O3] thin films and their application for IR sensors. Phys. Status Solidi A 199, 416–424 (2003).

Moalla, R. et al. Large anisotropy of ferroelectric and pyroelectric properties in heteroepitaxial oxide layers. Sci. Rep. 8, 4332 (2018).

Schossig, M., Norkus, V. & Gerlach, G. Dielectric and pyroelectric properties of ultrathin, monocrystalline lithium tantalate. Infrared Phys. Technol. 63, 35–41 (2014).

Bhatia, B. et al. Pyroelectric current measurements on PbZr0.2Ti0.8O3 epitaxial layers. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 104106 (2012).

Chang, D. H. & Yoon, Y. S. Pyroelectric properties of the B-polyvilnylidene fluoride (PVDF) thin film prepared by vacuum deposition with electric field application. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 41, 7234–7238 (2002).

Aliane, A. et al. Impact of crystallization on ferro-, piezo- and pyro-electric characteristics in thin film P(VDF–TrFE). Org. Electron. 25, 92–98 (2015).

Luo, J. et al. High specific detectivity infrared detector using crystal ion slicing transferred LiTaO3 single-crystal thin films. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 300, 111650 (2019).

Thorlabs. Mid-IR photovoltaic detectors, HgCdTe (MCT). https://www.thorlabs.com/newgrouppage9.cfm?objectgroup_id=11319 (2024).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Quantum ESPRESSO toward the exascale. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 154105 (2020).

van Setten, M. J. et al. The PseudoDojo: training and grading a 85 element optimized norm-conserving pseudopotential table. Comput. Phys. Commun. 226, 39–54 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Range-separated hybrid functional pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 108, 165142 (2023).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA‐type density functional constructed with a long‐range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Barone, V. et al. Role and effective treatment of dispersive forces in materials: Polyethylene and graphite crystals as test cases. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 934–939 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Air Force Office of the Scientific Research (AFOSR) (award no. FA9550−22-1-0024). C.B.E. acknowledges support for this research through a Vannevar Bush Faculty Fellowship (ONR N00014-20-1-2844) and the EPiQS Initiative of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (grant no. GBMF9065). Ferroelectric measurement at the University of Wisconsin–Madison was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES), under award no. DE-FG02-06ER46327. C.S.C. acknowledges support for this research by the NRF grant funded by the Korea Government (MSIT) (grant nos. RS-2024-00355333 and RS-2024-00451173). We thank J. A. del Alamo for providing access to the electrical characterization equipment in his laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. conceived the idea and directed the team. X. Zhang designed and coordinated the experiments and characterization. O.E., P.P. and S. Lindemann performed epitaxial growth by sputtering, under the guidance of C.B.E. X. Zhang performed growth by pulsed laser deposition. M.A. and Y.F.S. conducted simulations of heterostructures using DFT. X. Zhang, S. Lee, N.M.H. and H.K. developed the mechanical exfoliation theory. C.S.C. and H.L. performed and analysed the TEM measurements. X. Zhang, O.E., S. Lindemann, P.P. and Y. Shao conducted materials characterizations. Exfoliation and device fabrication were carried out by X. Zhang, J.M.S. and J.-E.R. X. Zhang set up a confocal optical path and conducted pyroelectric characterization. J.M.S. designed all schematic illustrations. S. Lee, M.-K.S., J.M.S., J.-E.R., X. Zheng, B.B., H.K. and H.S.K. provided feedback throughout experiments and data analysis. The paper was written by X. Zhang, S. Lee, M.-K.S., C.S.C., Y.F.S. and J.K. All authors contributed to the analysis and discussion of the results leading to the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Characterization of PMN-PT on NSO substrate.

a, TEM cross-section image of as-grown PMN-PT/NSO. b, Fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns of a selected area of a including the PMN-PT epilayer (i), PMN-PT/NSO interface (ii) and NSO substrate (iii). The lattice direction of the pattern is labelled with the red rectangle. The in-plane lattice parameter for both PMN-PT film and NSO substrate is calculated as 4.158 A along the [010] direction, confirming coherent epitaxy. c, XRD Azimuthal φ scan of (101) PMN-PT after exfoliation and growth on NSO, confirming the maintained single crystallinity without in-plane rotation.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Result of charge transfer calculated by DFT simulations.

Charge transfer of PTO/STO (left) and BTO/STO (right) supercell by DFT calculation. In the three-dimensional structural plots, red and blue areas represent charge acceptance and donation, respectively. The two-dimensional maps present the visualized charge transfer at the A-face from the epilayer (top), the interface (middle) and the B-face from the substrate (bottom).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Theoretical guidelines for different Pb-containing heterostructures.

a-c, Different modes of peeling for PMN-PT/STO (a), PMN-PT/NSO (b), and PMN-PT/SRO (c) heterostructures as a function of Ni stressor thickness at an Ni stress level of 600 MPa. There is an exfoliation window with the change of stressor thickness for all three systems due to interface weakening, consistent with experiment observations.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Universal applicability of ALO to various Pb-based material systems.

a,b, Optical images (a) and EBSD maps (b) of exfoliated Pb-containing membrane with a size of 5 × 5 mm2, confirming high uniformity and maintained single crystallinity. c, Rocking curve of as-grown Pb-containing epilayers on different substrates. An FWHM ranging between 0.016° to 0.090° indicates good crystallinity of all epilayers. d,e, Optical images (d) and plan-view SEM (e) showing the surfaces of non-Pb-containing materials including BTO (left) and SRO (right) with spalled STO substrate layers. f, Peeling modes of heterostructure with different lattice mismatch. Exfoliation of Pb-containing materials occurs with lattice mismatches ranging from 2.9% to 0.026%. While non-Pb-containing materials with the same lattice mismatch shows spalling results, thus clearly substantiating the universal effect of Pb-related interface weakening. NSOa and NSOb refer to the two anisotropic in-plane pseudocubic lattice parameters of the NSO substrate.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Demonstration of universal applicability of ALO.

a, Schematic illustration of freestanding membrane production using PTO as an interlayer. b, Rocking curve of SRO epilayer grown on STO (left) and PTO-covered STO (right). The minimal difference in FWHM values indicates that the presence of the PTO interlayer does not affect the crystallinity of the top layer. c, Optical microscopic images (left) and photos (inset), EBSD maps (middle), and AFM images (right) of (i) STO/PTO and (ii) SRO/PTO, exfoliated from STO. The exfoliated films are around 5 × 5 mm2. The exfoliated surfaces show single crystallinity and root-mean-square (RMS) roughness of 0.34 nm and 0.19 nm for STO/PTO and SRO/PTO, respectively. d, AFM images of STO substrate surface after exfoliation with an RMS roughness of 0.14 nm and 0.20 nm. The substrate surface shows step terrace structures, which are consistent with that of the film, indicating precise crack propagation has occurred at the interface.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Production of large-scale 20 nm-thick membrane.

a, Optical microscopic image of an exfoliated film with a size of 10 × 10 mm2. b, Rocking curve of 20 nm-thick PMN-PT grown on STO with a FWHM of 0.283° indicating good crystallinity. c, EBSD maps with 4 × 4 positions over the entire membrane (top) and histograms showing misorientation angle distribution extracted from the maps (bottom). The misorientation angle distribution shows a peak position of 0.17° and a FWHM value of lower than 0.19°, confirming the maintained crystallinity on a large scale after exfoliation.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Characterization of PMN-PT on STO with various thicknesses.

a, 2 theta-omega XRD scans, and b, rocking curve of PMN-PT (002). XRD spectrums are shown for PMN-PT layers grown on STO substrate with thicknesses ranging between 10 to 200 nm. The vertical dashed line indicates the peak position for bulk PMN-PT. Good crystallinity is confirmed by the FWHM of the rocking curve ranging from 0.07° to 0.53°.

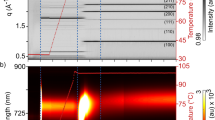

Extended Data Fig. 8 Reproducibility of ALO process.

a-d, Optical images (top left), AFM images (top right), EBSD maps (bottom right), and histograms showing misorientation angle distribution extracted from the maps (bottom left) of PMN-PT membranes exfoliated from STO with a thickness of 10 nm (a), 40 nm (b), 80 nm (c), and 200 nm (d) with a size of 5 × 5 mm. The RMS roughness of the surface ranges from 0.23 nm to 0.84 nm. The peak positions are all close to zero (0.09° to 0.25°) with a narrow width (0.09° to 0.54°), thus quantitatively indicating the preserved crystallinity and high uniformity after exfoliation.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Stability of pyroelectric response.

a, Average pyroelectric current density of 10 devices fabricated by PMN-PT membrane with a thickness of 10 nm under a temperature modulation frequency from 100 to 760 Hz. The error ribbon (coloured in light blue) presents their standard deviation. b, Pyroelectric current density of the device with a thickness of 10 nm under different temperature modulation amplitudes. The error ribbon (coloured in light blue) presents the standard deviation across 10 measurements. c, Pyroelectric current density recorded over time with a radiation modulation frequency of 760 Hz and amplitude of 4.6 K.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Notes 1–9, Supplementary References, Supplementary Figs. 1–18 and Supplementary Table 1.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Ericksen, O., Lee, S. et al. Atomic lift-off of epitaxial membranes for cooling-free infrared detection. Nature 641, 98–105 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08874-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08874-7