Abstract

When two monolayer materials are stacked with a relative twist, an effective moiré translation symmetry emerges, leading to fundamentally different properties in the resulting heterostructure. As such, moiré materials have recently provided highly tunable platforms for exploring strongly correlated systems1,2. However, previous studies have focused almost exclusively on monolayers with triangular lattices and low-energy states near the Γ (refs. 3,4) or K (refs. 5,6,7,8,9) points of the Brillouin zone (BZ). Here we introduce a new class of moiré systems based on monolayers with triangular lattices but low-energy states at the M points of the BZ. These M-point moiré materials feature three time-reversal-preserving valleys related by threefold rotational symmetry. We propose twisted bilayers of exfoliable 1T-SnSe2 and 1T-ZrS2 as realizations of this new class. Using extensive ab initio simulations, we identify twist angles that yield flat conduction bands, provide accurate continuum models, analyse their topology and charge density and explore the platform’s rich physics. Notably, the M-point moiré Hamiltonians exhibit emergent momentum-space non-symmorphic symmetries and a kagome plane-wave lattice structure. This represents, to our knowledge, the first experimentally viable realization of projective representations of crystalline space groups in a non-magnetic system. With interactions, these systems act as six-flavour Hubbard simulators with Mott physics. Moreover, the presence of a momentum-space non-symmorphic in-plane mirror symmetry renders some of the M-point moiré Hamiltonians quasi-one-dimensional in each valley, suggesting the possibility of realizing Luttinger-liquid physics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Moiré heterostructures have recently emerged as versatile quantum simulators of archetypal condensed matter models1,2. When two identical or nearly identical monolayers are twisted, the resulting moiré modulation of the interlayer potential gives rise to an effective moiré discrete translation symmetry. In the moiré BZ, the moiré-modulated interlayer hybridization opens gaps in the folded band structure, quenching the kinetic energy of the monolayer electrons10. The moiré system thus enters an interaction-dominated regime, providing a tunable platform for simulating various prototypical condensed matter systems. A notable example is twisted bilayer graphene5, which hosts unconventional superconductors11 and correlated insulators12 near the magic angle and has recently been shown to simulate topological heavy-fermions13,14. Transition-metal dichalcogenide (TMD) heterobilayers can emulate the Hubbard model on a triangular lattice7,15, whereas twisted WTe2 exhibits signatures of a one-dimensional Luttinger liquid, although its theoretical description remains challenging owing to the complex monolayer band structure16. Beyond these examples, a growing body of theoretical and experimental work has explored other exotic phases in TMDs17,18,19,20,21,22. Furthermore, both integer and fractional Chern insulator states have been reported in moiré TMD23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, graphene31,32,33 and graphene–boron nitride heterostructures34,35,36,37.

Until now, nearly all moiré heterostructures have been based on twisting monolayers with triangular lattices and low-energy states near the Γ (refs. 3,4) or K (refs. 5,6,7,8,9) points, leading to systems with one or two valleys (in the two-valley case, time-reversal exchanges the valley). This work introduces a new family of moiré materials by twisting monolayers with triangular lattices and low-energy states around the M point of the BZ. These M-point moiré systems feature three time-reversal-preserving valleys related by C3z rotation symmetry. Building on extensive ab initio calculations, we propose (among others38) experimentally exfoliable twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2 as promising platforms for realizing M-point moiré heterostructures. We develop quantitative simplified models for these systems and perform a detailed analysis of the band structure, topology and charge density of the flat bands at the predicted small twist angles. We show analytically that M-point moiré Hamiltonians exhibit a new type of symmetry, termed momentum-space non-symmorphic39,40,41,42,43. In crystallography, space groups are symmorphic or non-symmorphic, depending on whether they include symmetry operations that translate the origin by a fraction of the lattice vectors. Although in real space conventional crystalline groups can feature both symmorphic and non-symmorphic operations, in momentum space, all conventional crystalline groups exhibit only symmorphic operations. M-point moiré systems are the first experimentally realizable non-magnetic systems to exhibit momentum-space non-symmorphic symmetries, all without requiring an applied magnetic field in the range of thousands of Tesla39,40,41. In a single valley, these non-symmorphic symmetries can render the system effectively one-dimensional at the single-particle level, making M-point moiré systems prime candidates for Luttinger-liquid simulators16,44. With all three valleys considered, they can realize a multi-orbital triangular lattice Hubbard model (H. Hu et al., to be published), in which valley-spin local moments couple differently along the three C3z-related directions, in a manner reminiscent of Kitaev’s honeycomb model45.

M-point moiré models

For triangular monolayer lattices, the moiré lattice is also triangular, generated by the reciprocal lattice vectors \({{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{1}}\) and \({{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{2}}\) (see Supplementary Information Section IV). These vectors span the moiré reciprocal lattice \({\mathcal{Q}}={\mathbb{Z}}{{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{1}}+{\mathbb{Z}}{{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{2}}\), as depicted in Fig. 1a. In general, the single-particle Hamiltonians of moiré systems take the form of a hopping model in momentum space. This arises because the moiré potential breaks the monolayer translation symmetry and couples momentum states that are connected by reciprocal moiré vectors. The single-particle moiré Hamiltonian can be written \({\mathcal{H}}={\sum }_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} },i,j}{[{h}_{{\bf{Q}},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}({\bf{k}})]}_{ij}{\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},i}^{\dagger }{\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} },j}\), in which \({\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},i}^{\dagger }\) denotes the moiré plane-wave operators at moiré momentum k, and i denotes a combined index comprising orbital, spin, valley, layer or other further degrees of freedom.

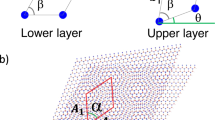

a–c, The three panels correspond to the cases in which the low-energy degrees of freedom are located at the Γ (a), K (b) and M (c) points. In each panel, the sublattices are coloured according to the legend above each plot. The moiré BZ is shown by the grey hexagon, whereas the reciprocal moiré vectors \({{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{1,2}}\) as well as the auxiliary vectors \({{\bf{q}}}_{1,2,3}^{{\prime} }\) and \({{\bf{q}}}_{0,1,2}\) are shown by the black arrows.

When the low-energy fermions of the monolayer are located at the Γ point3,4, the operators \({\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},i}^{\dagger }\) carry total momentum k − Q and the Q-vectors lie on the triangular lattice shown in Fig. 1a. In the case of a monolayer with low-energy states located at the K point5,6,7, the moiré fermions carry an extra valley index η = ±, in which the moiré Hamiltonian is diagonal. The Q-vectors form a honeycomb lattice, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. The moiré and monolayer operators are related by \({\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},\eta ,i}^{\dagger }={\widehat{a}}_{\eta {{\bf{K}}}_{{\rm{K}}}^{l}+{\bf{k}}-{\bf{Q}},l,i}^{\dagger }\) for \({\bf{Q}}\in {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{\eta l}^{{\prime} }\), in which \({\widehat{a}}_{{\bf{p}},l,i}^{\dagger }\) represents the monolayer operators from layer l = ± at momentum p and \({{\bf{K}}}_{{\rm{K}}}^{l}\) is the K-point momentum of layer l.

Distinctly, in M-point moiré materials, the Q-vectors form a kagome lattice, as shown in Fig. 1c. To be specific, the moiré operators in layer l—which, for the present case, include only an extra spin s = ↑,↓ index—are related to the monolayer ones according to \({\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},s,l}^{\dagger }={\widehat{c}}_{{C}_{3z}^{\eta }{{\bf{K}}}_{{\rm{M}}}^{l}+{\bf{k}}-{\bf{Q}},s,l}^{\dagger }\), for \({\bf{Q}}\in {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{\eta +l}\), in which \({{\bf{K}}}_{{\rm{M}}}^{l}\) is the momentum of the monolayer M point. The three C3z-related valleys indexed by η = 0, 1 and 2 are implicitly encoded by the kagome sublattice to which Q belongs: the valley-η fermions are supported on the \({{\mathcal{Q}}}_{\eta \pm 1}\) sublattices (in which η + l is taken modulo 3), as derived in Supplementary Information Section IV. As we will show, the kagome Q-lattice leads to substantially different properties of M-point moiré materials.

Materials realizations

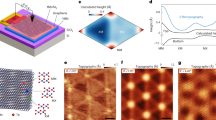

We now turn to 1T-SnSe2 and 1T-ZrS2 as experimentally exfoliable monolayers for realizing M-point moiré heterostructures (see Supplementary Information Section II). The monolayer crystal structure of both materials is shown in Fig. 2a,b and belongs to the \(P\bar{3}m1{1}^{{\prime} }\) group, which is generated by translations, C3z rotations, in-plane twofold rotations C2x, inversion \({\mathcal{I}}\) and time-reversal \({\mathcal{T}}\) symmetries. The Sn (Zr) atoms form a triangular lattice, with the Se (S) atoms being located at the other C3z-invariant Wyckoff positions above and below the Sn (Zr) plane. The ab initio band structures of monolayer SnSe2 and ZrS2 shown in Fig. 2c,d reveal two insulators for which the conduction band minimum is located at the M point. The first isolated Kramers-degenerate conduction band of SnSe2 is atomic, being spanned by an effective s-like molecular orbital centred on the Sn atom. For ZrS2, the low-energy M-point states are contributed primarily by the \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals of Zr.

a,b, Side and top views of the crystal structures of 1T-SnSe2 and 1T-ZrS2. c,d, The ab initio band structures for SnSe2 and ZrS2, respectively. The lowest spinful conduction band, with minima at the M points, is highlighted in red, whereas the Wannier orbitals contributing to the low-energy states are shown as insets. The yellow (blue) colours correspond to the positive (negative) sign of the orbitals.

Moiré Hamiltonians

Because the SnSe2 and ZrS2 monolayers lack twofold out-of-plane rotation symmetry (C2z), there are two distinct ways to stack and subsequently twist them by an angle θ to achieve a large-scale moiré periodicity. In the so-called AA-stacking configuration, the top (l = +1) and bottom (l = −1) layers are stacked directly on top of each other and then twisted by the layer-dependent angle \(\frac{l\theta }{2}\). By contrast, for AB-stacking, the bottom layer is first rotated by 180° around the \(\widehat{{\bf{z}}}\) axis, before applying the \(\frac{l\theta }{2}\) twist. As discussed in Supplementary Information Section III, the two configurations have different crystalline symmetries. Although both stackings feature C3z and \({\mathcal{T}}\) symmetries, they differ in the direction of the in-plane twofold rotation symmetry: the AA (AB)-stacking arrangement has C2x (C2y) symmetry.

We perform large-scale ab initio calculations (which include relaxation effects) at commensurate twist angles 13.17° ≥ θ ≥ 3.89° (see Methods and Supplementary Information Sections III and VIII) and construct two types of moiré Hamiltonian model for each angle and stacking configuration according to the method outlined in Supplementary Information Section IX. The first is a numerically exact model, which accurately reproduces a large set of spinful bands (at least the first five in each valley) in both energy and wavefunction. The second is an analytical approximate continuum model capturing the dispersion and wavefunction of the first or first two (depending on the angle) lowest-energy spinful gapped bands (and, qualitatively, the higher-energy spectrum) in each valley. The comprehensive results at all angles are presented in Supplementary Information Section XI. Unlike the case of Γ-point or K-point twisting, ab initio simulations are crucial for obtaining even the correct qualitative moiré Hamiltonian. The two-centred first-monolayer harmonic approximation incorrectly predicts continuous translation symmetry along one direction (for example, along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction in valley η) and an overall gapless spectrum, as shown in Supplementary Information Section VI.

Figure 3 summarizes the ab initio results for twisted AA-stacked and AB-stacked SnSe2 and ZrS2 at low twist angle. Both stacking configurations exhibit approximate spin SU(2) symmetry (see Supplementary Information Section IX) and feature two sets of spinful gapped bands in each of the three C3z-related valleys, as shown in Fig. 3a–d. The lowest-energy set of bands has a narrow bandwidth of around 10 meV. The charge density distribution (CDD) for the lowest two bands in valley η = 0, shown in Fig. 3e–h, reveals that these moiré systems have approximate spatial symmetries beyond the exact valley-preserving C2x and C2y symmetries expected in the AA-stacked and AB-stacked configurations, respectively. For instance, the CDD of the first set of spinful bands in AA-stacked SnSe2, as well as the first two sets of bands in twisted ZrS2, feature an approximate twofold rotation symmetry (the second set of spinful bands in AA-stacked SnSe2 exhibits this symmetry to a lesser extent). In the AB-stacked configuration, the centre of the approximate C2z symmetry aligns with the unit cell origin, whereas in the AA-stacked case, the effective \({\widetilde{C}}_{2z}\) rotation centre is shifted away from the unit cell origin and will be specified below. Moreover, the CDD suggests the presence of an approximate in-plane mirror symmetry, \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\). These effective symmetries (whose origin is explained below and in Supplementary Information Section VB) prompt us to construct simplified analytical continuum models that can capture and explain these features.

a–d, Band structures for AA-stacked (a,c) and AB-stacked (b,d) twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2 at the commensurate angle θ = 3.89°. Both the ab initio and valley-resolved continuum model band structures are shown. e–h, The layer-resolved CDD corresponding to the first and second sets of spinful bands in valley η = 0. The Wigner–Seitz unit cell is indicated by the dashed hexagon.

In valley η = 0, the simplified M-point moiré Hamiltonian can be expressed as

in which mx and my are the anisotropic effective masses of SnSe2 and ZrS2 (see Methods). As shown in Fig. 4a,b, the moiré potential takes the form of a hopping model on two of the three sublattices of the kagome M-point Q-lattice. Explicitly, the simplified Hermitian moiré potential tensor exhibits spin SU(2) symmetry and includes only interlayer terms, given by \({[{T}_{{\bf{Q}},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{AA}}}]}_{ls;(-l)s}=(\pm {\rm{i}}{w}_{1}^{{\rm{AA}}}+{w}_{2}^{{\rm{AA}}}){\delta }_{{\bf{Q}}\pm {{\bf{q}}}_{0},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}+{w}_{3}^{{\prime} {\rm{AA}}}{\delta }_{{\bf{Q}}\pm ({{\bf{q}}}_{1}-{{\bf{q}}}_{2}),{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}\) and \({[{T}_{{\bf{Q}},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{AB}}}]}_{ls;(-l)s}={w}_{2}^{{\rm{AB}}}{\delta }_{{\bf{Q}}\pm {{\bf{q}}}_{0},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}+{w}_{4}^{{\prime} {\rm{AB}}}{\delta }_{{\bf{Q}}\pm ({{\bf{q}}}_{1}-{{\bf{q}}}_{2}),{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}\). The interlayer hopping parameters, obtained by fitting to the ab initio band structure, are listed in Methods. The band structure of the simplified model for AA-stacked SnSe2 is shown in Fig. 4c, indicating excellent qualitative agreement with the ab initio results for such a small number of parameters. In the simplified models, for both SnSe2 and ZrS2, the overlap between the fitted and ab initio bands is larger than 95% (85%) with the first (second) set of spinful bands, as we show in Supplementary Information Section XI.

a, Relationship between the monolayer and moiré BZs, with the coloured and grey hexagons representing the respective BZs. b, Generation of the \({\bf{Q}}\)-lattice in the η = 0 valley, showing the hopping terms of the moiré potential matrix \({T}_{{\bf{Q}},{{\bf{Q}}}^{{\prime} }}\). c, The band structure of the simplified moiré model for AA-stacked SnSe2 at θ = 3.89°. The colour scheme matches that of Fig. 3.

Momentum-space non-symmorphic symmetries

The approximate symmetries inferred from the layer-resolved CDD of the M-point moiré Hamiltonian are exact symmetries in the simplified moiré models from equation (1) (see detailed discussion in Supplementary Information Section VI). Specifically, the centre of the effective twofold rotation symmetry \({\widetilde{C}}_{2z}\) for the AA-stacked Hamiltonian is located at \(\frac{{{\bf{q}}}_{\eta }}{|{{\bf{q}}}_{\eta }{|}^{2}}\arg ({\rm{i}}{w}_{1}^{{\rm{AA}}}+{w}_{2}^{{\rm{AA}}})\) in valley η. By contrast, the simplified AB-stacked moiré Hamiltonian exhibits C2z symmetry, with its rotation centre aligned with the origin of the moiré unit cell. Because both models are effectively spinless (owing to atomistic arguments presented in Supplementary Information Section XI) and exhibit either \({\widetilde{C}}_{2z}{\mathcal{T}}\) or \({C}_{2z}{\mathcal{T}}\) symmetry in each valley, the Berry curvature of any gapped set of bands is exactly zero. Consequently, the first two sets of bands of both the AA-stacked and AB-stacked moiré Hamiltonians are topological trivial and, hence, Wannierizable. This is also consistent (and the result of) the bands being flat and exhibiting a large (40 meV) gap from one another. However, the physics of these Hubbard (with interaction) bands is far from trivial in this system, as shown below.

Unlike the C2z and \({\widetilde{C}}_{2z}\) symmetries, the effective mirror \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry has an unconventional action on the momentum-space moiré fermions. Specifically, \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) acts non-symmorphically in momentum space, with \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}{\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}},{\bf{Q}},s,l}^{\dagger }{\widetilde{M}}_{z}^{-1}={\widehat{c}}_{{\bf{k}}+{{\bf{q}}}_{\eta },{\bf{Q}}+{{\bf{q}}}_{\eta },s,-l}^{\dagger }\) for \({\bf{Q}}\in {{\mathcal{Q}}}_{\eta +l}\). Because \({{\bf{q}}}_{0}=\frac{{{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{1}}}{2}\), the action of \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) can only be made conventional by folding the moiré BZ along \({{\bf{q}}}_{\eta }\), which would break the moiré translation symmetry. The non-symmorphic action of the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry originates from the moiré fermions realizing a projective representation of the symmetry group of the system. Letting \({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1,2}}}^{{\prime} }\) denote the two moiré translation operators for valley η = 0 along the direct moiré lattice vectors \({{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1,2}}\) (with \({{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{i}}\cdot {{\bf{b}}}_{{M}_{j}}=2\pi {\delta }_{ij}\)), we find that \([{T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}}^{{\prime} },{\widetilde{M}}_{z}]=\{{T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}}^{{\prime} },{\widetilde{M}}_{z}\}=0\) (contrasting with a conventional mirror Mz symmetry, which would commute with both \({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}}^{{\prime} }\) and \({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}}^{{\prime} }\)).

It is important to note that the effective \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry is not accidental. In the AA-stacked case, it can be shown to hold exactly for arbitrary moiré harmonics within the local-stacking approximation46. In the limit of vanishing twist angle (θ → 0), the moiré Hamiltonian can be constrained by the exact symmetries of the untwisted bilayer configuration. The inversion symmetry of the untwisted AA-stacked bilayer gives rise to the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry of the moiré Hamiltonian, as shown in Supplementary Information Sections VB and VI. In the AB-stacked case, the true in-plane mirror symmetry of the untwisted bilayer leads to an effective inversion symmetry \(\widetilde{{\mathcal{I}}}\) of the corresponding moiré Hamiltonian, which also acts non-symmorphically in momentum space. In the simplified AB-stacked model, the approximate C2z symmetry, combined with the \(\widetilde{{\mathcal{I}}}\) symmetry, leads to an \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}={C}_{2z}\widetilde{{\mathcal{I}}}\) symmetry of the system.

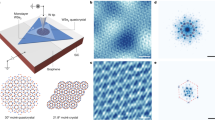

Projective fermion representations that realize momentum-space non-symmorphic symmetries have previously been proposed in magnetic systems42 or systems subjected to a large magnetic field (on the order of thousands of Tesla)40,41,47. M-point moiré materials provide the first experimentally viable realization of these symmetries in any (that is, magnetic or non-magnetic) system. To better understand the origin of the momentum-space non-symmorphic action of the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, we construct a simple one-dimensional tight-binding model that incorporates it. The resulting ladder model, shown in Fig. 5a, mimics the dispersion of an atomic band in the M-point moiré Hamiltonian for valley η = 0 along the \(\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction (see Supplementary Information Section VI). Each unit cell is threaded by a uniform perpendicular magnetic field, enclosing a π-flux. Because π-flux and (−π)-flux are equivalent, the model also respects time-reversal and \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry. In the Fourier-transformed basis \({\widehat{b}}_{k,l}^{\dagger }=\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}{\sum }_{n}{\widehat{b}}_{n,l}^{\dagger }{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}kn}\), the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry acts non-symmorphically as \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}{\widehat{b}}_{k,l}^{\dagger }{\widetilde{M}}_{z}^{-1}={\widehat{b}}_{k+\pi ,-l}^{\dagger }\), ensuring that the spectra of the Hamiltonian at k and k + π are identical, as shown in Fig. 5b.

a, A ladder tight-binding model with magnetic flux that realizes the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry. Fermion operators and hopping amplitudes are indicated above each site (black dots). b, Dispersion relation. c, Energy dispersion of the first band of AA-stacked SnSe2 at θ = 3.89° in the first moiré BZ. d, Schematic illustration of the corresponding quasi-one-dimensional character of atomic bands in M-point moiré systems for valley η = 0. Each Wannier orbital (dots) is coloured according to its \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) eigenvalue. The grey rectangle represents the rectangular unit cell of each \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry sector.

Hubbard and Luttinger simulators

Within each valley, the first two sets of spinful bands in SnSe2 and ZrS2 bilayers are individually Wannierizable, with their bandwidths tunable by adjusting the twist angle. Given the excellent SU(2) symmetry, these M-point moiré systems become effective simulators of the Hubbard model when Coulomb interactions are included (H. Hu et al., to be published). However, owing to the extra valley degree of freedom, these systems go beyond the single-band U(2) Hubbard model, instead realizing a six-flavour U(2) × U(2) × U(2) Hubbard model.

Another key distinction from the standard Hubbard model can arise from the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry. In real space, \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) does not change the position along the moiré heterostructure. As a result, the continuum moiré Hamiltonian can be made diagonal in the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) basis. Because \({({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}}^{{\prime} })}^{2}{({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}}^{{\prime} })}^{-1}\) and \({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}}^{{\prime} }\) both commute with \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\), each mirror sector of valley η = 0 will feature reduced translation symmetry specified by the rectangular lattice vectors \(2{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}-{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}\) and \({{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}\). The \({T}_{{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}}^{{\prime} }\) operator anticommutes with \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\), exchanging the two mirror sectors. The Wannier orbitals of any atomic band—such as the first conduction band of AA-stacked SnSe2 from Fig. 5c—can therefore be split by their \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) eigenvalues: the orbitals of each mirror sector are displaced by \({{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}\) and form two interpenetrating rectangular lattices shown in Fig. 5d. Within each mirror sector and in valley η = 0, the interorbital separation is larger by a factor of \(\sqrt{3}\) along the \(\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction compared with the \(\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) one. Provided that the Wannier orbital spread is approximately isotropic (as it happens for the first band of AA-stacked SnSe2 but not in the first band of twisted ZrS2), this will lead to reduced hopping along \(\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) compared with \(\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) (see Supplementary Information Section VI). As the tunnelling between \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) sectors is forbidden, the system in each valley will behave quasi-one-dimensionally, with flatter dispersion along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction, effectively emulating a Luttinger model. In the three-valley system, this quasi-one-dimensional behaviour causes the U(2) × U(2) × U(2) local moments to couple differently along three C3z-related directions, similar (but not identical) to the couplings of the Kitaev model45.

We note, however, that quasi-one-dimensionality along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction (that is, flatter dispersion along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction) is not an inherent or universal feature of M-point moiré materials. Instead, it is the presence of the effective \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, not previously identified, that plays a more general role. Together with approximately isotropic Wannier orbitals for the bands, the effective \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry can enforce one-dimensional behaviour in the single-particle valley-projected moiré Hamiltonian. However, this symmetry is also compatible with two-dimensional physics in general (see Methods). For instance, because of the elongated Wannier orbitals, twisted ZrS2 exhibits excellent effective \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, but its first set of conduction bands is not quasi-one-dimensional along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction.

Discussion

We have introduced a new platform for moiré materials based on monolayers with triangular lattices, in which the low-energy states are located at the M points of the BZ. The presence of three C3z-related valleys makes M-point moiré materials manifestly different from pre-existing Γ-point and K-point twisted heterostructures. We have shown that M-point moiré materials can be realized in many materials38,48 and specifically in twisted 1T-SnSe2 and 1T-ZrS2, both of which are experimentally exfoliable. By constructing the corresponding moiré Hamiltonians, we have shown that these materials provide the first experimentally viable example of momentum-space non-symmorphic symmetry in a non-magnetic system. The projective representations of the crystallographic space groups associated with these symmetries extend beyond present theoretical frameworks49, opening new avenues for discovering symmetry-protected topological phases.

When electron–electron interactions are considered, twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2 bilayers can realize strongly correlated, tunable six-flavour Hubbard models. As well as exhibiting Mott physics and correlated insulating phases at integer fillings, these systems can spontaneously break the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, potentially giving rise to various stripe phases, which will be explored in future work (H. Hu et al., to be published). Notably, we find that the multivalley Wannier model for AA-stacked SnSe2 admits exact solutions in the strong-coupling limit, under the experimentally justified assumption of weak spin-valley U(6) symmetry breaking in the interaction Hamiltonian. At integer fillings 0 ≤ ν ≤ 6 of the lowest six flat bands, the corresponding ground states include classical spin liquids at ν = 1 and ν = 5, valence bond solids at ν = 2 and ν = 4 and a quantum spin liquid at ν = 3 (H. Hu et al., to be published). The perfect nesting at momentum qη in valley η, enforced by the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, further enhances the potential for new correlated phases, as does the recently introduced quantum nesting condition50, satisfied as a result of the same symmetry. Moreover, owing to their quasi-one-dimensional nature within each valley, these materials are promising candidates for exploring Luttinger physics.

Methods

First-principles calculation

The ab initio calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)51,52,53,54,55 and OpenMX56,57,58,59. The lattice relaxation was carried out in two stages: first, the twisted structures were ‘pre-relaxed’ using a machine learning force field (MLFF) trained with NequIP60 and DPmoire61; second, a further relaxation step was conducted using VASP until the force on each atom was less than 0.01 eV Å−1. van der Waals interactions were included using the DFT-D2 method of Grimme62 for SnSe2 and the DFT-D3 method of Grimme et al.63 for ZrS2, based on benchmarking with bulk structures (details provided in Supplementary Information Section III). A vacuum slab larger than 15 Å was applied along the z-direction to eliminate any artificial layer interactions.

The exchange-correlation energy functional within the generalized gradient approximation as parameterized by Perdew et al.64 was used in the VASP calculations. The calculations were carried out on a 2 × 2 × 1 k-mesh for θ = 13.17° and θ = 9.43° and on a 1 × 1 × 1 mesh for smaller twist angles θ. The energy cut-off for the plane-wave basis is 288 eV (337 eV) for SnSe2 (ZrS2). Larger energy cut-offs have been tested to have negligible influence on the band structures. Furthermore, the ab initio Hamiltonians in the atomic orbital basis, used for valley projection and continuum model construction, were generated using OpenMX56,57,58,59. In these calculations, we used the 2019 version of optimized numerical pseudo-atomic orbitals, specifically Sn7.0-s2p2d2 and Se7.0-s2p2d2 for SnSe2 and Zr7.0-s2p2d2 and S7.0-s2p2d2 for ZrS2.

First-principles results for twisted bilayers

AA-stacked twisted bilayers are obtained by aligning the two layers directly on top of one another and rotating them by a small relative angle θ. By contrast, the AB-stacked configurations are formed by rotating the layers by a relative angle of 180° − θ. The AA-stacked and AB-stacked configurations exhibit P3211′ and P3121′ symmetries, respectively. Both space groups include C3z and \({\mathcal{T}}\) as symmetry generators, but P3211′ also features C2x, whereas P3121′ includes C2y. In this work, we primarily focus on the AA-stacked configuration of twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2, with further details as well as results for AB-stacked heterostructures provided in Supplementary Information Section III.

Large-scale ab initio calculations were performed for twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2 bilayers using the methodology outlined above. The relaxed structures for SnSe2 and ZrS2 at a twist angle θ = 3.89° are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, highlighting both interlayer and intralayer relaxation effects. For SnSe2, the interlayer distance varies by approximately 0.8 Å and the maximum intralayer displacement is about 0.3 Å. By contrast, ZrS2 exhibits smaller variations, with interlayer distance changes of approximately 0.6 Å and intralayer displacements up to 0.15 Å. These findings underscore the marked lattice relaxation effects in both materials, which are crucial for the energetics of the moiré potential and the resulting band dispersion.

Using the fully relaxed bilayer structures, we calculated the moiré band structures for SnSe2 and ZrS2. The band structures for θ = 3.89° are shown in Fig. 3, with further results for larger twist angles presented in Extended Data Fig. 2. The moiré Hamiltonian reveals one or two sets of isolated conduction bands, each consisting of six spinful bands originating from the three C3z-related M valleys. Each valley contributes two nearly degenerate bands owing to the approximate SU(2) symmetry. As the twist angle decreases, the moiré bands become increasingly flat, with the bandwidth of the lowest set narrowing to just several meV. Further details are provided in Supplementary Information Section III.

Constructing faithful continuum models

The workflow used in this work for constructing faithful continuum models for twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2 bilayers is summarized schematically in Extended Data Fig. 3. The process begins with a rigid twisted bilayer structure at a chosen commensurate twist angle θ. This rigid structure is relaxed using a combination of machine learning force field and density functional theory (DFT), as detailed in Supplementary Information Section III. The relaxed structure is then used for large-scale DFT calculations to obtain the ab initio spectrum (through VASP) and the corresponding tight-binding Kohn–Sham Hamiltonian in an atomic orbital basis (through OpenMX).

Next, the ab initio Hamiltonian is projected onto the relevant orbitals and valleys to derive a low-dimensional effective Hamiltonian at a small set of k-points within the moiré BZ, as described in Supplementary Information Section VIII. Simultaneously, a symmetry-based parameterization of the moiré Hamiltonian is constructed symbolically, as explained in Supplementary Information Sections IV, V and VII. The parameters of this model are determined through either linear extraction or nonlinear fitting, as detailed in Supplementary Information Section IX. The final output is an analytic, accurate and faithful continuum moiré Hamiltonian for the corresponding heterostructure.

With these continuum models, we can compute various spectral properties of the moiré system, including the band structures across the full moiré BZ, the CDD of the isolated bands, their Berry curvature, Wilson loops and interacting tight-binding models, among others. Further details are provided in Supplementary Information Section XI and H. Hu et al. (to be published). For the simple continuum models shown in equation (1) for twisted SnSe2 and ZrS2 at θ = 3.89°, the parameters are listed in Extended Data Table 1.

Other M-point moiré materials

As well as 1T-SnSe2 (refs. 65,66,67,68,69) and 1T-ZrS2 (refs. 70,71,72) studied in this work, a wide range of other experimentally exfoliable monolayers offer promising platforms for M-point moiré heterostructures, as listed in ref. 38. These include materials with structures similar to 1T-SnSe2 and 1T-ZrS2, such as 1T-ZrSe2 (refs. 71,72), 1T-SnS2 (refs. 73,74), 1T-HfSe2 (ref. 75) and 1T-HfS2 (refs. 76,77,78). Also, GaTe (ref. 79), which has a different crystalline structure, further expands this moiré ‘universality class’.

Emergence of quasi-one-dimensionality

In the main text, we showed that quasi-one-dimensional physics can emerge in M-point moiré materials. However, we also highlighted that quasi-one-dimensionality along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction, as observed in AA-stacked twisted SnSe2, is neither a generic nor a fundamental feature of M-point moiré systems. To further illustrate this, Extended Data Fig. 4 shows the dispersion of the first two sets of conduction bands for the four monolayer-stacking configurations considered in this work.

Starting with AA-stacked twisted SnSe2, Extended Data Fig. 4a,b shows that the two gapped conduction bands are nearly dispersionless along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction in valley η. This observation aligns with the general argument presented in the main text and arises from the combined effects of the effective \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry and the approximately isotropic shape of the Wannier orbitals associated with these bands. Notably, this dispersion asymmetry is opposite to what would be expected from the effective monolayer masses of SnSe2, as given in Extended Data Table 1: my > mx would generally favour flatter dispersion along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction rather than along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction. However, in the case of AA-stacked SnSe2, the difference between my and mx is not substantial (\({m}_{y}{\not\gg}{m}_{x}\)), allowing the effect of \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry to dominate and promote quasi-one-dimensional behaviour along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction (with flatter dispersion along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction).

In AB-stacked SnSe2, Extended Data Fig. 4c,d shows that the bands are not quasi-one-dimensional. This behaviour arises because of relatively larger relaxation effects, which worsen the validity of the local-stacking approximation for this monolayer and stacking configuration. Because the effective \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) and \(\widetilde{{\mathcal{I}}}\) symmetries rely on the local-stacking approximation, this heterostructure does not exhibit strong \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry. Among the four heterostructures considered in this work, AB-stacked SnSe2 shows the smallest overlap between the ab initio wavefunctions and those computed from the fitted effective model with enforced \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry. Consequently, the system does not feature quasi-one-dimensional behaviour.

For the first conduction band of either AA-stacked or AB-stacked twisted ZrS2, shown in Extended Data Fig. 4f,h, the greatly enhanced monolayer mass asymmetry (my ≫ mx) or, equivalently, the real-space orbitals elongated along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction—as illustrated in Fig. 3g,h—leads to a flatter dispersion along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction for the first set of conduction bands. This occurs despite the system exhibiting excellent \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, which is even stronger than that of AA-stacked SnSe2. For the second set of bands of twisted ZrS2, shown in Extended Data Fig. 4e,g, the orbitals have nearly equal spread along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) and \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) directions. Consequently, our argument, which incorporates both the \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry and the orbital shape, holds, resulting in flatter dispersion along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{x}}}\) direction.

These results demonstrate that quasi-one-dimensionality is not a generic feature of M-point moiré materials but instead depends on both symmetry and energetic considerations. The relevant symmetry is compatible with behaviours opposite to those proposed in ref. 80, as observed in twisted ZrS2. Specifically, the mass-enforced band flattening, also identified in BC3 (ref. 81), in which my ⋙ mx, occurs in the opposite direction to that predicted by ref. 80. Our momentum-space non-symmorphic \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry emerges as the unifying principle that reconciles these seemingly contradictory emergent behaviours. This symmetry, along with the nature of the constituent orbitals, plays a crucial role in shaping the interacting Hamiltonian, ultimately determining the emergence of one-dimensional or two-dimensional physics (H. Hu et al., to be published).

All of these findings underscore the importance of performing detailed ab initio calculations. As discussed in the main text, without such precise insights, simplified models—such as those using the two-centred first-monolayer harmonic approximation82—produce incorrect results. Specifically, they predict a continuous translational symmetry of the system along the \({C}_{3z}^{\eta }\widehat{{\bf{y}}}\) direction in valley η and an overall gapless spectrum, neither of which are observed in the four monolayer and stacking configurations analysed in this work.

Wannier model for AA-stacked twisted SnSe2

For AA-stacked twisted SnSe2, the system develops topologically trivial, isolated conduction bands for each valley and spin. H. Hu et al. (to be published) construct the Wannier orbitals and derive the corresponding interacting models for this system. The Wannier orbitals for each valley η, denoted by \({\widehat{d}}_{{\bf{R}},\eta ,s}^{\dagger }\) for unit cell \({\bf{R}}\in {\mathbb{Z}}{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{1}}+{\mathbb{Z}}{{\bf{a}}}_{{M}_{2}}\) and spin s, form a triangular lattice. The positions of the Wannier orbitals within each unit cell for all three valleys are nearly identical.

The tight-binding model is expressed as

in which, owing to the emergent \({\widetilde{M}}_{z}\) symmetry, the hopping becomes quasi-one-dimensional. The dominant hopping terms are

The dominant interaction term is the on-site Hubbard repulsion, which takes the form

in which \({n}_{{\bf{R}},\eta }={\sum }_{s}{\widehat{d}}_{{\bf{R}},\eta ,s}^{\dagger }{\widehat{d}}_{{\bf{R}},\eta ,s}\) is the density operator associated with unit cell R and valley η.

Data availability

All data generated in this study are included in the main text and the Supplementary Information. The continuum models for the M-point moiré materials derived in this work are available online as a supplementary file. Further data, along with any code required for reproducing the figures, are available from the authors on reasonable request.

References

Andrei, E. Y. et al. The marvels of moiré materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 201–206 (2021).

Kennes, D. M. et al. Moiré heterostructures as a condensed-matter quantum simulator. Nat. Phys. 17, 155–163 (2021).

Angeli, M. & MacDonald, A. H. Γ valley transition metal dichalcogenide moiré bands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2021826118 (2021).

Claassen, M., Xian, L., Kennes, D. M. & Rubio, A. Ultra-strong spin–orbit coupling and topological moiré engineering in twisted ZrS2 bilayers. Nat. Commun. 13, 4915 (2022).

Bistritzer, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108, 12233–12237 (2011).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E., Martin, I. & MacDonald, A. H. Topological Insulators in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide homobilayers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 086402 (2019).

Wu, F., Lovorn, T., Tutuc, E. & MacDonald, A. H. Hubbard model physics in transition metal dichalcogenide moiré bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 026402 (2018).

Devakul, T., Crépel, V., Zhang, Y. & Fu, L. Magic in twisted transition metal dichalcogenide bilayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 6730 (2021).

Zhang, X.-W. et al. Polarization-driven band topology evolution in twisted MoTe2 and WSe2. Nat. Commun. 15, 4223 (2024).

Carr, S. et al. Twistronics: manipulating the electronic properties of two-dimensional layered structures through their twist angle. Phys. Rev. B 95, 075420 (2017).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 80–84 (2018).

Song, Z.-D. & Bernevig, B. A. Magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene as a topological heavy fermion problem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 047601 (2022).

Chou, Y.-Z. & Das Sarma, S. Kondo lattice model in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 026501 (2023).

Tang, Y. et al. Simulation of Hubbard model physics in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Nature 579, 353–358 (2020).

Wang, P. et al. One-dimensional Luttinger liquids in a two-dimensional moiré lattice. Nature 605, 57–62 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Correlated insulating states at fractional fillings of moiré superlattices. Nature 587, 214–218 (2020).

Anderson, E. et al. Programming correlated magnetic states with gate-controlled moiré geometry. Science 381, 325–330 (2023).

Zhao, W. et al. Gate-tunable heavy fermions in a moiré Kondo lattice. Nature 616, 61–65 (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Superconductivity in 5.0° twisted bilayer WSe2. Nature 637, 839–845 (2025).

Xia, Y. et al. Superconductivity in twisted bilayer WSe2. Nature 637, 833–838 (2025).

Sheng, D. N., Reddy, A. P., Abouelkomsan, A., Bergholtz, E. J. & Fu, L. Quantum anomalous Hall crystal at fractional filling of moiré superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 066601 (2024).

Li, T. et al. Quantum anomalous Hall effect from intertwined moiré bands. Nature 600, 641–646 (2021).

Xu, F. et al. Observation of integer and fractional quantum anomalous Hall effects in twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. X 13, 031037 (2023).

Park, H. et al. Observation of fractionally quantized anomalous Hall effect. Nature 622, 74–79 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Thermodynamic evidence of fractional Chern insulator in moiré MoTe2. Nature 622, 69–73 (2023).

Cai, J. et al. Signatures of fractional quantum anomalous Hall states in twisted MoTe2. Nature 622, 63–68 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Fractional Chern insulator in twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036501 (2024).

Jia, Y. et al. Moiré fractional Chern insulators. I. First-principles calculations and continuum models of twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 109, 205121 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Fractional Chern insulators versus nonmagnetic states in twisted bilayer MoTe2. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045147 (2024).

Sharpe, A. L. et al. Emergent ferromagnetism near three-quarters filling in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 365, 605–608 (2019).

Serlin, M. et al. Intrinsic quantized anomalous Hall effect in a moiré heterostructure. Science 367, 900–903 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Tunable correlated Chern insulator and ferromagnetism in a moiré superlattice. Nature 579, 56–61 (2020).

Lu, Z. et al. Fractional quantum anomalous Hall effect in multilayer graphene. Nature 626, 759–764 (2024).

Dong, Z., Patri, A. S. & Senthil, T. Theory of quantum anomalous Hall phases in pentalayer rhombohedral graphene Moiré structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 206502 (2024).

Dong, J. et al. Anomalous Hall crystals in rhombohedral multilayer graphene. I. Interaction-driven Chern bands and fractional quantum Hall states at zero magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 206503 (2024).

Herzog-Arbeitman, J. et al. Moiré fractional Chern insulators. II. First-principles calculations and continuum models of rhombohedral graphene superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 109, 205122 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. 2D theoretically twistable material database. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.09741 (2024).

de la Flor, G., Souvignier, B., Madariaga, G. & Aroyo, M. I. Layer groups: Brillouin-zone and crystallographic databases on the Bilbao Crystallographic Server. Acta Crystallogr. A 77, 559–571 (2021).

Chen, Z. Y., Yang, S. A. & Zhao, Y. X. Brillouin Klein bottle from artificial gauge fields. Nat. Commun. 13, 2215 (2022).

Zhang, C., Chen, Z. Y., Zhang, Z. & Zhao, Y. X. General theory of momentum-space nonsymmorphic symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 256601 (2023).

Xiao, Z., Zhao, J., Li, Y., Shindou, R. & Song, Z.-D. Spin space groups: full classification and applications. Phys. Rev. X 14, 031037 (2024).

Fonseca, A. G. et al. Weyl points on nonorientable manifolds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 266601 (2024).

Kennes, D. M., Xian, L., Claassen, M. & Rubio, A. One-dimensional flat bands in twisted bilayer germanium selenide. Nat. Commun. 11, 1124 (2020).

Kitaev, A. Anyons in an exactly solved model and beyond. Ann. Phys. 321, 2–111 (2006).

Jung, J., Raoux, A., Qiao, Z. & MacDonald, A. H. Ab initio theory of moiré superlattice bands in layered two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. B 89, 205414 (2014).

Herzog-Arbeitman, J., Song, Z.-D., Elcoro, L. & Bernevig, B. A. Hofstadter topology with real space invariants and reentrant projective symmetries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 236601 (2023).

Petralanda, U., Jiang, Y., Bernevig, B. A., Regnault, N. & Elcoro, L., Two-dimensional topological quantum chemistry and catalog of topological materials. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.08950 (2024).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Topological quantum chemistry. Nature 547, 298–305 (2017).

Han, Z., Herzog-Arbeitman, J., Bernevig, B. A. & Kivelson, S. A. “Quantum geometric nesting” and solvable model flat-band systems. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041004 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for open-shell transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 48, 13115 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155108 (2003).

Ozaki, T. & Kino, H. Numerical atomic basis orbitals from H to Kr. Phys. Rev. B 69, 195113 (2004).

Ozaki, T. & Kino, H. Efficient projector expansion for the ab initio LCAO method. Phys. Rev. B 72, 045121 (2005).

Lejaeghere, K. et al. Reproducibility in density functional theory calculations of solids. Science 351, aad3000 (2016).

Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

Liu, J., Fang, Z., Weng, H. & Wu, Q., DPmoire: a tool for constructing accurate machine learning force fields in moiré systems. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.19333 (2025).

Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 27, 1787–1799 (2006).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Busch, C., Fröhlich, C. & Hulliger, F. Struktur, elektrische und thermoelektrische Eigenschaften von SnSe2. Helv. Phys. Acta 34, 359–368 (1961).

Su, Y., Ebrish, M. A., Olson, E. J. & Koester, S. J. SnSe2 field-effect transistors with high drive current. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 263104 (2013).

Zeng, J. et al. Gate-induced interfacial superconductivity in 1T-SnSe2. Nano Lett. 18, 1410–1415 (2018).

Wu, H. et al. Spacing dependent and cation doping independent superconductivity in intercalated 1T 2D SnSe2. 2D Mater. 6, 045048 (2019).

Huang, Y. et al. Universal mechanical exfoliation of large-area 2D crystals. Nat. Commun. 11, 2453 (2020).

Lv, H. Y., Lu, W. J., Shao, D. F., Lu, H. Y. & Sun, Y. P. Strain-induced enhancement in the thermoelectric performance of a ZrS2 monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 4538–4545 (2016).

Mañas-Valero, S., García-López, V., Cantarero, A. & Galbiati, M. Raman Spectra of ZrS2 and ZrSe2 from bulk to atomically thin layers. Appl. Sci. 6, 264 (2016).

Alsulami, A. et al. Lattice transformation from 2D to quasi 1D and phonon properties of exfoliated ZrS2 and ZrSe2. Small 19, 2205763 (2023).

Xia, C. et al. The characteristics of n- and p-type dopants in SnS2 monolayer nanosheets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 19674–19680 (2014).

Huang, F. et al. Mechanically exfoliated few-layer SnS2 and integrated van der Waals electrodes for ultrahigh responsivity phototransistors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 4, 5333–5339 (2022).

Kang, M. et al. Electrical characterization of multilayer HfSe2 field-effect transistors on SiO2 substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 143108 (2015).

Zhao, X., Xia, C., Wang, T., Dai, X. & Yang, L. Characteristics of n- and p-type dopants in 1T-HfS2 monolayer. J. Alloys Compd. 689, 302–306 (2016).

Wu, N. et al. Strain effect on the electronic properties of 1T-HfS2 monolayer. Physica E 93, 1–5 (2017).

Singh, D. & Ahuja, R. Enhanced optoelectronic and thermoelectric properties by intrinsic structural defects in monolayer HfS2. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2, 6891–6903 (2019).

Zhao, Q. et al. Thickness-induced structural phase transformation of layered gallium telluride. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 18719–18726 (2016).

Kariyado, T. & Vishwanath, A. Flat band in twisted bilayer Bravais lattices. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 033076 (2019).

Kariyado, T. Twisted bilayer BC3: valley interlocked anisotropic flat bands. Phys. Rev. B 107, 085127 (2023).

Fujimoto, M., Kawakami, T. & Koshino, M. Perfect one-dimensional interface states in a twisted stack of three-dimensional topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 043209 (2022).

Lei, C., Mahon, P. T. & MacDonald, A. H., Moiré band theory for M-valley twisted transition metal dichalcogenides. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.18828 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank U. Petralanda, E. Morosan, G. Skorupskii, M. Claassen, D. M. Kennes, A. Rubio, L. Xian, Q. Xu, L. Elcoro and N. Regnault for collaboration on two related projects38,48, as well as S. A. Parameswaran for his collaboration on a separate project. H.P. and Y.J. thank Q. Wu, Y. Zhang and J. Liu for helpful discussions. We are also grateful to the authors of ref. 83 for sharing their manuscript before posting. The simulations presented in this article were partially performed on computational resources managed and supported by Princeton Research Computing, a consortium of groups including the Princeton Institute for Computational Science and Engineering (PICSciE) and the Office of Information Technology’s High Performance Computing Center and Visualization Laboratory at Princeton University. We also thank the Donostia International Physics Center (DIPC) Supercomputing Center for their technical assistance and continued support. D.C. acknowledges support from DOE grant no. DE-SC0016239 and the hospitality of the DIPC, at which this work was carried out. D.C. also gratefully acknowledges the support provided by the Leverhulme Trust. H.H. and Y.J. were supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101020833), as well as by the IKUR Strategy under the collaboration agreement between Ikerbasque Foundation and DIPC on behalf of the Department of Education of the Basque Government. M.G.V. and H.P. were supported by the Ministry for Digital Transformation and the Civil Service of the Spanish Government through the QUANTUM ENIA project call – Quantum Spain project and by the European Union through the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan – NextGenerationEU within the framework of the Digital Spain Agenda 2026. M.G.V. also thanks PID2022-142008NB-I00 supported by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER, UE, the Canada Excellence Research Chairs Program for Topological Quantum Matter, to Diputación Foral de Gipuzkoa Programa Mujeres y Ciencia and the EU NextGenerationEU/PRTR-C17.I1, as well as by the IKUR Strategy under the collaboration agreement between Ikerbasque Foundation and DIPC on behalf of the Department of Education of the Basque Government. B.A.B. was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through grant no. GBMF8685 towards the Princeton theory programme, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative (grant no. GBMF11070), the Office of Naval Research (ONR grant no. N00014-20-1-2303), the Global Collaborative Network Grant at Princeton University, the Simons Investigators grant no. 404513, the BSF Israel US foundation no. 2018226, the NSF-MERSEC (grant no. MERSEC DMR 2011750), the Simons Collaboration on New Frontiers in Superconductivity (grant no. SFI-MPS-NFS-00006741-01) and the Schmidt Foundation at Princeton University. L.M.S. was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s EPiQS Initiative through grant GBMF9064, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and NSF MRSEC through the Princeton Center for Complex Materials, DMR-2011750. D.K.E. acknowledges support from the ERC under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 852927), the German Research Foundation (DFG) under the priority programme SPP2244 (project no. 535146365), the EU EIC Pathfinder Grant ‘FLATS’ (grant agreement no. 101099139) and the Keele Foundation. J.Y.’s work at Princeton University is supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through grant no. GBMF8685 towards the Princeton theory programme. J.Y.’s work at the University of Florida is supported by start-up funds at the University of Florida. Note: in ref. 83, the authors also introduced a new platform based on M-point twisting. When there is overlap, our manuscripts agree in their conclusions.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A.B. conceived the project based on input from Y.J. and experimental insights provided by K.F.M., D.K.E., L.M.S., C.F. and J.S.; D.C., H.H., Y.J., H.P. and B.A.B. contributed to developing the general theory for M-point moiré Hamiltonians, including symmetries, the local-stacking approximation, the emergence of momentum-space non-symmorphic symmetries and analytic approximations for the moiré Hamiltonians; H.P. and Y.J. carried out the ab initio calculations, partially supported by computational resources arranged by M.G.V.; Y.J., H.P., D.C. and H.H. performed the valley projection of the moiré Hamiltonian; D.C. developed algorithms for deriving various numerically exact and simplified analytical moiré Hamiltonians from the valley-projected results, with input from J.Y., H.H., H.P. and Y.J.; D.C., Y.J. and B.A.B. prepared the original draft, with insights from H.H. and H.P.; D.C., Y.J., H.H., H.P. and B.A.B. collaboratively wrote Methods and the Supplementary Information. All authors reviewed and contributed to editing the final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Jianpeng Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Ab initio lattice relaxation results for twisted AA-stacked SnSe2 and ZrS2 at θ = 3.89°.

a–c, For twisted SnSe2: interlayer distance (ILD) (a); intralayer atom displacements in the bottom (b) and top (c) layers. d–f, Same as a–c but for twisted ZrS2. The definitions of the C3z-symmetric local regions labelled by AAi (for 1 ≤ i ≤ 3) are given in Supplementary Information Section III.

Extended Data Fig. 2 The ab initio band structures of twisted AA-stacked SnSe2 and ZrS2 bilayers for twist angles 13.17° ≥ θ ≥ 5.09°.

The twist angle is indicated above each panel. a–c, Moiré conduction bands of twisted SnSe2. d–f, Band structure of twisted ZrS2. In both cases, the lowest group of conduction bands, isolated from other energy bands, consists of six bands originating from the three inequivalent M valleys of the monolayer.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Small-angle band structures for M-point moiré SnSe2 and ZrS2.

a–d, Results for SnSe2. e–h, Results for ZrS2. Each panel shows the dispersion of a gapped set of conduction bands in valley η = 0 across the first moiré BZ from Fig. 4b, with the band minimum set to zero for clarity. Columns represent different stacking configurations (AA-stacked and AB-stacked) and different monolayers and rows show either the first or the second set of conduction bands. For each band, the results are averaged over the two approximately SU(2)-degenerate bands.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figs. 1–133, discussion (including detailed DFT results for monolayers and bilayers, derivation and symmetry analysis of moiré Hamiltonians with and without gradient terms, fitting procedures for continuum models, analytical and numerical band structure results and a comprehensive summary of effective models) and Supplementary Tables 1–26.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Călugăru, D., Jiang, Y., Hu, H. et al. Moiré materials based on M-point twisting. Nature 643, 376–381 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09187-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09187-5

This article is cited by

-

Fractional quantization in insulators from Hall to Chern

Nature Physics (2025)