Abstract

Acute inflammation is an essential response that our bodies use to combat infections1. However, in the absence of infections, chronic inflammation can have a pivotal role in the onset and progression of chronic diseases, such as arthritis, cancer, autoimmune disorders, metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), and most ageing-associated pathologies2,3. The underlying mechanisms that distinguish chronic inflammation from its acute counterpart remain unclear, posing challenges to the development of targeted therapies for these major diseases. Here we identify a mechanism that separates the two responses: during chronic but not acute inflammation, chromatin remodelling is influenced by nuclear autophagy, in which the WSTF protein of the ISWI chromatin-remodelling complex interacts with the ATG8 autophagy protein family in the nucleus. This interaction leads to WSTF nuclear export and subsequent degradation by autophagosomes and lysosomes in the cytoplasm. Loss of WSTF leads to chromatin opening over inflammatory genes, amplifying inflammation. Cell-penetrating peptides that block the WSTF–ATG8 interaction do not affect acute inflammation but suppress chronic inflammation in senescence as well as in MASH and osteoarthritis in mouse models and patient samples. The ability to specifically target chronic inflammation without blunting acute inflammation offers an approach for treating common chronic inflammatory diseases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

RNA-seq and ATAC–seq data have been deposited at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession number GSE214410. Other original data are included in the Supplementary Information or are available on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Medzhitov, R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454, 428–435 (2008).

Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Vitale, G., Capri, M. & Salvioli, S. Inflammaging and ‘Garb-aging’. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 28, 199–212 (2017).

Hotamisligil, G. S. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 444, 860–867 (2006).

Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 25, 1822–1832 (2019).

Ferrucci, L. & Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15, 505–522 (2018).

Deretic, V. Autophagy in inflammation, infection, and immunometabolism. Immunity 54, 437–453 (2021).

Cadwell, K. Crosstalk between autophagy and inflammatory signalling pathways: balancing defence and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 661–675 (2016).

Levine, B., Mizushima, N. & Virgin, H. W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 469, 323–335 (2011).

Deretic, V. Autophagy as an innate immunity paradigm: expanding the scope and repertoire of pattern recognition receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 21–31 (2012).

Mochida, K. et al. Receptor-mediated selective autophagy degrades the endoplasmic reticulum and the nucleus. Nature 522, 359–362 (2015).

Dou, Z. et al. Autophagy mediates degradation of nuclear lamina. Nature 527, 105–109 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. VAMP2 controls murine epidermal differentiation and carcinogenesis by regulation of nucleophagy. Dev. Cell 59, 2005–2016 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. SIRT1 is downregulated by autophagy in senescence and ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 1170–1179 (2020).

Papandreou, M.-E., Konstantinidis, G. & Tavernarakis, N. Nucleophagy delays aging and preserves germline immortality. Nat Aging 3, 34–46 (2023).

Zhao, H. et al. Destabilizing heterochromatin by APOE mediates senescence. Nat Aging 2, 303–316 (2022).

Lamark, T. & Johansen, T. Mechanisms of selective autophagy. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 37, 143–169 (2021).

Behrends, C., Sowa, M. E., Gygi, S. P. & Harper, J. W. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature 466, 68–76 (2010).

Mizushima, N., Yamamoto, A., Matsui, M., Yoshimori, T. & Ohsumi, Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1101–1111 (2004).

Clapier, C. R., Iwasa, J., Cairns, B. R. & Peterson, C. L. Mechanisms of action and regulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 407–422 (2017).

Campisi, J. Cellular senescence: putting the paradoxes in perspective. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 21, 107–112 (2011).

Dou, Z. et al. Cytoplasmic chromatin triggers inflammation in senescence and cancer. Nature 550, 402–406 (2017).

Bozhenok, L., Wade, P. A. & Varga-Weisz, P. WSTF-ISWI chromatin remodeling complex targets heterochromatic replication foci. EMBO J. 21, 2231–2241 (2002).

Corona, D. F. et al. ISWI is an ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling factor. Mol. Cell 3, 239–245 (1999).

Yadon, A. N. & Tsukiyama, T. SnapShot: chromatin remodeling: ISWI. Cell 144, 453–453 (2011).

Rodier, F. et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 973–979 (2009).

Paull, T. T. Mechanisms of ATM activation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 84, 711–738 (2015).

Xiao, A. et al. WSTF regulates the H2A.X DNA damage response via a novel tyrosine kinase activity. Nature 457, 57–62 (2009).

Buenrostro, J. D., Wu, B., Chang, H. Y. & Greenleaf, W. J. ATAC-seq: a method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 109, 21.29.1–21.29.9 (2015).

Chien, Y. et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev. 25, 2125–2136 (2011).

Kang, T.-W. et al. Senescence surveillance of pre-malignant hepatocytes limits liver cancer development. Nature 479, 547–551 (2011).

Nusinow, D. P. et al. Quantitative proteomics of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Cell 180, 387–402 (2020).

Pezone, A. et al. Inflammation and DNA damage: cause, effect or both. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 19, 200–211 (2023).

Lewis, H. D. et al. Creation of a novel peptide with enhanced nuclear localization in prostate and pancreatic cancer cell lines. BMC Biotechnol. 10, 79 (2010).

Brunt, E. M. Pathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 195–203 (2010).

Brown, G. T. & Kleiner, D. E. Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Metabolism 65, 1080–1086 (2016).

Michelotti, G. A. et al. Smoothened is a master regulator of adult liver repair. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 2380–2394 (2013).

Syn, W.-K. et al. Hedgehog-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibrogenic repair in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 137, 1478–1488 (2009).

Du, K. et al. Increased glutaminolysis marks active scarring in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis progression. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 1–21 (2020).

Hansen, H. H. et al. Human translatability of the GAN diet-induced obese mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 20, 210 (2020).

Woodell-May, J. E. & Sommerfeld, S. D. Role of inflammation and the immune system in the progression of osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Res. 38, 253–257 (2020).

Robinson, W. H. et al. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 580–592 (2016).

Glasson, S. S., Blanchet, T. J. & Morris, E. A. The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15, 1061–1069 (2007).

Glasson, S. S., Chambers, M. G., Van Den Berg, W. B. & Little, C. B. The OARSI histopathology initiative—recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the mouse. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18, S17–S23 (2010).

Sherwood, J. C., Bertrand, J., Eldridge, S. E. & Dell’Accio, F. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of cartilage damage and repair. Drug Discov. Today 19, 1172–1177 (2014).

Wang, Y. et al. Nuclear autophagy interactome unveils WSTF as a constitutive nuclear inhibitor of inflammation. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.04.510822 (2022).

Chen Lf, Fischle, W., Verdin, E. & Greene, W. C. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science 293, 1653–1657 (2001).

Murley, A. & Dillin, A. Macroautophagy in quiescent and senescent cells: a pathway to longevity? Trends Cell Biol. 33, 495–504 (2023).

Kaur, J. & Debnath, J. Autophagy at the crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 461–472 (2015).

Vizioli, M. G. et al. Mitochondria-to-nucleus retrograde signaling drives formation of cytoplasmic chromatin and inflammation in senescence. Genes Dev. 34, 428–445 (2020).

Kundakovic, M. et al. Practical guidelines for high-resolution epigenomic profiling of nucleosomal histones in postmortem human brain tissue. Biol. Psychiatry 81, 162–170 (2017).

Bai, B. et al. Deep profiling of proteome and phosphoproteome by isobaric labeling, extensive liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 585, 377–395 (2017).

Xu, P., Duong, D. M. & Peng, J. Systematical optimization of reverse-phase chromatography for shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 8, 3944–3950 (2009).

Pagala, V. R. et al. Quantitative protein analysis by mass spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 1278, 281–305 (2015).

Niu, M. et al. Extensive peptide fractionation and y ion-based interference detection method for enabling accurate quantification by isobaric labeling and mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 89, 2956–2963 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Systematic optimization of long gradient chromatography mass spectrometry for deep analysis of brain proteome. J. Proteome Res. 14, 829–838 (2015).

Wang, X. et al. JUMP: a tag-based database search tool for peptide identification with high sensitivity and accuracy. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 3663–3673 (2014).

Li, Y. et al. JUMPg: an integrative proteogenomics pipeline identifying unannotated proteins in human brain and cancer cells. J. Proteome Res. 15, 2309–2320 (2016).

Shi, H. et al. Amino acids license kinase mTORC1 activity and Treg cell function via small G proteins Rag and Rheb. Immunity 51, 1012–1027 (2019).

Peng, J., Elias, J. E., Thoreen, C. C., Licklider, L. J. & Gygi, S. P. Evaluation of multidimensional chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) for large-scale protein analysis: the yeast proteome. J. Proteome Res. 2, 43–50 (2003).

Nesvizhskii, A. I. & Aebersold, R. Interpretation of shotgun proteomic data: the protein inference problem. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 1419–1440 (2005).

Kleiner, D. E. et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41, 1313–1321 (2005).

Stringer, C., Wang, T., Michaelos, M. & Pachitariu, M. Cellpose: a generalist algorithm for cellular segmentation. Nat. Methods 18, 100–106 (2021).

Carpenter, A. E. et al. CellProfiler: image analysis software for identifying and quantifying cell phenotypes. Genome Biol. 7, R100 (2006).

McQuin, C. et al. CellProfiler 3.0: next-generation image processing for biology. PLoS Biol. 16, e2005970 (2018).

Kamekura, S. et al. Osteoarthritis development in novel experimental mouse models induced by knee joint instability. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13, 632–641 (2005).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140 (2010).

Kuleshov, M. V. et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W90–W97 (2016).

Freund, A., Orjalo, A. V., Desprez, P.-Y. & Campisi, J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 238–246 (2010).

Babicki, S. et al. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W147–W153 (2016).

Buenrostro, J. D., Giresi, P. G., Zaba, L. C., Chang, H. Y. & Greenleaf, W. J. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

John, S. et al. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nat. Genet. 43, 264–268 (2011).

Ross-Innes, C. S. et al. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature 481, 389–393 (2012).

An, H. et al. TEX264 is an endoplasmic reticulum-resident ATG8-interacting protein critical for ER remodeling during nutrient stress. Mol. Cell 74, 891–908 (2019).

Paulo, J. A., Mancias, J. D. & Gygi, S. P. Proteome-wide protein expression profiling across five pancreatic cell lines. Pancreas 46, 690–698 (2017).

McAlister, G. C. et al. MultiNotch MS3 enables accurate, sensitive, and multiplexed detection of differential expression across cancer cell line proteomes. Anal. Chem. 86, 7150–7158 (2014).

Huttlin, E. L. et al. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell 143, 1174–1189 (2010).

Paulo, J. A., Gaun, A. & Gygi, S. P. Global analysis of protein expression and phosphorylation levels in nicotine-treated pancreatic stellate cells. J. Proteome Res. 14, 4246–4256 (2015).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504 (2003).

Chen, H. et al. cGAS suppresses genomic instability as a decelerator of replication forks. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb8941 (2020).

Kirkin, V. et al. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol. Cell 33, 505–516 (2009).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 (2015).

Kim, E. Y. et al. Structures of CaV2 Ca2+/CaM-IQ domain complexes reveal binding modes that underlie calcium-dependent inactivation and facilitation. Structure 16, 1455–1467 (2008).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Varadi, M. et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D439–D444 (2022).

Kozakov, D. et al. The ClusPro web server for protein-protein docking. Nat. Protoc. 12, 255–278 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The proteomic studies in human fibroblasts were conducted in collaboration with J. W. Harper and J. D. Mancias. We thank Y. Tan for generating the sgRNA constructs targeting SMARCA5 and the next-generation sequencing samples in control cells; J. Xia, T. Kumazawa, J. Zhu, E. Wang, K. Xiang, C. Pan, T. Yin, L. Tan and B. J. W. Lim for technical support and discussions; the members of the microscopy core facility of Center for Regenerative Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital for assistance with confocal microscopy; the members of the next-generation sequencing core at Massachusetts General Hospital for assistance with RNA-seq; R. Graham for advice on ATAC–seq; and P. B. Alexander, J. Rajagopal, Y.-C. Hsu, D. A. Sinclair, D. B. Sykes, A. Sahay, J. Zhu, K. Hochedlinger, R. T. Lee and R. Mostoslavsky for reading our manuscript. Z.D. is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) awards R35GM137889, R01AG082785, R00AG053406, UG3CA268117, UH3CA268117 and R21AG073894, Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and AFAR Grant for Junior Faculty, and the Hevolution/AFAR New Investigator award; T.J. by a strategic thematic grant from UiT and by TOPPFORSK (grant 249884) program of the Research Council of Norway; X.-F.W. by R01CA244564 and U54-AG075936 from the NIH; and Z.Y. by NIH awards R01AG072520, R01NS060123 and R01NS117590. Work by J.L. and S.J.H.S. is supported in part by the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and Harvard Catalyst NIH UL1TR002541. Y.X. is supported by Glenn Foundation for Medical Research Postdoctoral Fellowships in Aging Research from American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR); M.S.S. by NIDDK-1K08DK139370 from the NIH; A.M.D. by 2R01-AA010154 and R01-DK141086 from the NIH; and K.D. by NIDDK-K01DK135793-01A1 from the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.D. conceived the project. Y.W. designed and conducted most of the experiments. V.V.E. contributed to the MS results of ATG8 nuclear interactomes and proteomes in human fibroblasts, performed in the J. W. Harper and J. D. Mancias laboratories. A.K. contributed to part of the GABARAP–WSTF interaction results. Y.L. contributed to part of the data in MASH and OA experiments. M.S.S. and W.G. contributed to cohort 2 data of patients with MASH. Y.X. performed cancer cell WSTF co-IP with p65 and GABARAP experiments. A.O. contributed to part of the autophagy and senescence data. X.L., X.Z. and Z.Y. contributed to mouse brain LC3B interactome data. K.D., R.M.-D., A.P.H. and A.M.D. conducted part of the mouse MASH experiments. A.M.C.B. and C.H. contributed to part of the IHC staining and RT–qPCR for mouse MASH experiments. J.X., H.Z., X.M. and B.A. contributed to part of the osteoarthritis experiments. U.R. contributed to part of the shATG13 and shFIP200 data. T.O. contributed to part of the RT–qPCR analysis of CXCL10 and IF staining of SNF2H. M.C. and R.I.S. contributed to computational analyses of RNA-seq and ATAC–seq data. L.W. contributed to experimental design and part of the next-generation sequencing data. J.L. and S.J.H.S. contributed to part of the protein interaction maps. C.B. and P.D.A. contributed to part of the mouse NRAS liver tissue samples. Z.D. generated samples for next-generation sequencing in senescent cells and contributed to part of the autophagy, senescence and inflammation results. Z.D. and Z.Z. conceived and supervised inflammation experiments. S.V.S. and R.E.K. contributed to reagents of ISWI complex and supervised epigenetic experiments. X.-F.W., T.J. and Z.D. supervised the study and provided funding support. Y.W., X.-F.W., T.J. and Z.D. wrote the paper. All of the authors discussed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Katja Simon, Anja Zeigerer, Charles Roberts, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

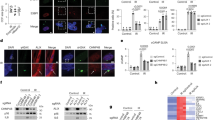

Extended Data Fig. 1 Nuclear autophagy targets chromatin remodelling proteins.

a, IMR90 cells were subjected to protein extraction using different approaches. Supernatants were analysed by immunoblotting. b, IMR90 cells were subjected to subcellular fractionation, generating nuclear and membrane fractions, then analysed by immunoblotting. c, IMR90 cells with indicated stable expression were fractionated, and the nuclear and chromatin fractions (collectively referred to as “nucleus”) were subjected to HA co-IP and immunoblotting. d, Overlap of autophagy interaction network (AIN) from a previous study versus the ATG8 nuclear interaction network from this study. e, Immunoblotting showing the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of mouse brains. f, The cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of the mouse brains were subjected to GFP co-IP. Silver-stained protein gels are shown. g, Interaction maps showing chromatin remodelling proteins in binding to human ATG8s and mouse LC3B. h-j, IMR90 cells were induced to senescence by HRasV12 and analysed by immunoblotting (h). Scheme depicting the workflow for TMT-proteomic analysis (i). The altered proteins in senescence were subjected to GO Cellular Component analysis, identifying nuclear proteins, which were further analysed by GO Biological Processes (j); P values are presented as -log10 (P). k-l, IMR90 cells stably expressing control or sh-ATG7 hairpin were treated with etoposide to induce senescence, followed by immunoblotting analyses for whole cell extract (k) or nuclear fractions (l). m, Binding intensities of human ATG8 (n = 3 biologically independent samples) and mouse LC3B to WSTF (n = 1; lysates pooled from 3 animals), and the protein levels of WSTF upon HRasV12 (n = 3 biologically independent samples) or etoposide-induced senescence (n = 2 biologically independent samples) from proteomic analyses. Results were presented as mean values with s.d.; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test for. For HRasV12 comparison, P values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test; exact P values are shown in the figure; n.s.: non-significant. n, mRNA levels of WSTF from RNA-Seq upon HRasV12 (n = 3 biologically independent samples) or etoposide-induced senescence (n = 2 biologically independent samples) from proteomic analyses. Results were presented as mean values with s.d.; P values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. No statistical analysis was performed for groups with n < 3. n.s., not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Autophagic degradation of WSTF in senescence.

a, Primary human and mouse fibroblasts were induced to senescence and analysed by immunoblotting. b, A549 senescence showed WSTF loss. c-d, IMR90 quiescence does not show WSTF loss. e-f, Senescent IMR90 induced by HRasV12 or replication exhaustion showed WSTF and not SNF2H loss. g, RT-qPCR analyses of BAZ1B/WSTF and CDKN2A/p16 under various senescent conditions. Results were normalized to Lamin A/C and presented as mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent samples; P values were calculated from unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. n.s.: non-significant; exact P values are shown in the figure. h-i, IMR90 cells stably expressing sh-NTC or sh-ATG7 were treated by IR (h) or etoposide (i) and harvested at indicated days, and analysed by immunoblotting. j-l, ATG13 or FIP200 knockdown inhibited WSTF loss in senescent IMR90 (j-k) and ARPE19 (l). m and n, Senescent IMR90 cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 (m) or MG132 (n) for 2 days, and analysed by immunoblotting. o, IMR90 cells were left untreated or treated with IR to induce senescence (harvested on day 14) and then stained with WSTF and LAMP1 antibodies, followed by imaging under a confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown. p, ARPE19 cells stably expressing mCherry-GFP-tagged WSTF were induced to senescence; the lysosomal inhibitor Lys05 was added for the last 2 days. Confocal microscopy images are shown. q, Percentage of cells with cytoplasmic GFP or mCherry. Data presented are mean values from four randomly selected fields, with over 200 cells analysed. Error bars: s.d. n.s.: non-significant. **** P value < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. r, SNF2H is unchanged in senescent IMR90 cells.

Extended Data Fig. 3 WSTF-GABARAP interaction mediates WSTF degradation.

a, In vitro translated 35S-methionine HA-WSTF was subjected to GST pull-down using GST-ATG8 proteins purified from bacteria. b-c, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged constructs, followed by HA co-IP and immunoblotting (b). Quantification of the relative binding to WSTF is shown (c) from 3 independent experiments. Mean with s.d.; exact P values are shown in the figure; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. d-f, Endogenous co-IP in HEK293T (d), HeLa (e), and MDA-MB-231(f), showing GABARAP-WSTF interaction. g-h, GST-GABARAP pulldown of in vitro translated WSTF (g) or SNF2H (h). i-j, BiFC assay in HEK293T and quantified in j. Mean values with s.d. are shown; four randomly selected fields with over 200 cells were used; exact P values are shown in the figure; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. k, BiFC assay in senescent IMR90, stained with indicated antibodies, and imaged under a confocal microscopy. l, In vitro pull-down showing the importance of F77 residue of GABARAP in binding WSTF. Mean values with s.e.m. are shown (n = 3 biological replicates); exact P values are shown in the figure; one-way ANOVA coupled with Tukey’s post hoc test. m, Co-IP in HEK293T. n, Scheme of WSTF mutants in binding to GABARAP, summarizing the key findings. “+” denotes positive binding; “-” denotes negative binding. o, Co-IP in HEK293T. p, GST-GABARAP pulldown of in vitro translated WSTF. q-r, Co-IP in HEK293T. s, IMR90 stably expressing HA-WSTF constructs were induced to senescence and analysed by immunoblotting. t-v, IMR90 expressing HA-WSTF constructs were stained and imaged. Mean values with s.d. are shown; over 400 cells in 4 different fields were randomly selected and scored; exact P values are shown in the figure; n.s.: non-significant; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Extended Data Fig. 4 ATM promotes GABARAP-WSTF binding and WSTF degradation.

a and b, Proliferating (Untr.) or senescent IMR90 cell lysates were subjected to GST-tagged GABARAP pulldown (a) with or without lambda protein phosphatase treatment of the cell lysates (b), then followed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. c, IMR90 cells expressing HA-GFP or HA-GABARAP were treated with IR to induce senescence with or without ATM inhibitor KU-55933 (ATMi), then subjected to HA immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. d, Untreated or senescent IMR90 cells treated with or without ATMi were subjected to GST-tagged GABARAP pulldown, then evaluated by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. e, mCherry-GFP-tagged WSTF stably expressing ARPE19 cells and IMR90 cells were either left untreated, or treated with etoposide to induce senescence. ATMi was added after 5 days of etoposide treatment and the cells were analysed after 10 days of etoposide treatment. Cells were imaged using a confocal microscopy. Representative images and scale bars are shown. f, Bar graphs showing the quantification of the percentage of cells with cytoplasmic GFP or mCherry. Data presented are mean values from four randomly selected fields, with over 200 cells analysed. Error bars: s.d. ****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. g, Untreated or senescent IMR90 cells stably expressing non-targeting control (sh-NTC) or sh-ATM were subjected to GST-tagged GABARAP pulldown followed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. The western blot experiments shown in a-d and g were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 5 WSTF represses senescence-associated inflammation.

a, Scheme of experimental design. WSTF overexpression did not affect SA-β-gal activity. Mean with s.d. are shown; 4 randomly selected fields; n.s.: non-significant. b, RT-qPCR analyses of IMR90. Results were normalized to Lamin A/C and presented as mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent samples; n.s. non-significant; exact P values are shown in the figure; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. c, IMR90 cells stably expressing vector control or WSTF were treated by IR and analysed by immunoblotting. d-e, The conditioned media from IR-induced senescent cells were analysed by cytokine arrays, showing different exposures. Mean values with s.e.m. are shown; n = 3 biological replicates; n.s. non-significant; **** P values < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. f-g, IMR90 were induced to senescence by HRasV12, then analysed by immunoblotting (f) or RT-qPCR (g). Mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent samples; **** P values < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. h-k, IMR90 with WSTF knockdown were analysed by immunoblotting (h-j) or RT-qPCR (k). Mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biological repeats; exact P values are shown in the figure; two-way ANOVA coupled with Tukey’s post hoc test. l, Stably expressed vector or WSTF IMR90 cells were infected by HRasV12 retrovirus and were harvested 7 days post infection. The cells were analysed by RNA-Seq. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were plotted in the HRasV12 condition. Representative genes down-regulated by WSTF in HRasV12-induced senescence were annotated. m, GO analysis using DEGs downregulated by WSTF in senescence. GO terms, P values, and the number of genes are shown. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Fisher exact test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons; P values are presented as -log10 (P). n, IMR90 cells were treated with IR or HRasV12 to establish senescence first, and then were infected with lentivirus encoding vector or WSTF, followed by immunoblotting. The western blot experiments shown in c, f, h-j and n were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Mechanisms by which WSTF inhibits the SASP.

a, IMR90 cells stably expressing vector control or WSTF were left untreated or treated with IR to induce senescence, followed by immunoblotting analyses. b, IMR90 cells were stained with γH2AX and H3K27me3 antibodies, followed by imaging under a confocal microscopy. Arrows indicate CCF. Quantification was performed across four biologically independent experiments. For each replicate, results presented are the mean values from four randomly selected imaging fields, with over 200 cells analysed per field. Statistical analysis was conducted using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Error bars: s.d.; n.s.: non-significant. c, Vector and WSTF stably expressing IMR90 cells were left untreated or induced to senescence with IR, then stained with a p65 antibody, followed by imaging under a confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown. Bar graphs showing the quantification of the percentage of nuclear p65 positive cells in vector and WSTF cells with or without IR treatment. Results shown are the mean values from four randomly selected fields with over 200 cells. Error bars: s.d.; n.s.: non-significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using two-way ANOVA coupled with Tukey’s post hoc test. d, Schematic illustrations of WSTF full-length and truncations. e, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged wild-type or mutant WSTF constructs, and then subjected to HA immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. f-i, full-length WSTF or WSTF truncations were stably expressed in IMR90 cells and were left untreated or induced to senescence by IR. Cells were harvested on day 14 post IR and analysed by immunoblotting (f and h) or RT-qPCR (g and i). Results of RT-qPCR were normalized to Lamin A/C and presented as mean values with s.d. (n = 3 biologically independent samples). Different letters (a, b, c, and d) represent significant differences (P < 0.05), whereas the same letter indicates no statistical significance, calculated by one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Extended Data Fig. 7 WSTF inhibits chromatin accessibility of inflammatory genes.

a and b, IMR90 cells were engineered to express control sgRNA or sgRNA against SNF2H, combined with vector or WSTF overexpression. The cells were left untreated or induced to senescence by IR, harvested on day 14, and analysed by immunoblotting (a) or RT-qPCR (b). Mean values with s.d. are shown; n = 3 biologically independent samples; exact P values are shown in the figure; one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. c, Scheme of experimental design for ATAC-Seq. d, The representative track views of a housekeeper gene Vinculin (VCL). e, GO analysis showing the top downregulated categories of differential accessible regions (DARs) by WSTF in senescent cells. The numbers of genes corresponding to the DARs and the P values are shown. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Fisher exact test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons.P values are displayed as -log10 (P). f, The genes from DEGs downregulated by WSTF from RNA-Seq were overlapped with genes from DARs downregulated by WSTF from ATAC-Seq. The overlapping genes were subjected to GO analysis, and the GO terms with the numbers of genes and P values are shown. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Fisher exact test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. P values are displayed as -log10 (P). g and h, Transcription factor prediction from RNA-Seq using DEGs (g) and ATAC-Seq using DARs (h) that are downregulated by WSTF in HRasV12-induced senescence. P values are displayed as -log10 (P). i, IMR90 cells stably expressing HA-WSTF were treated with etoposide to induce senescence, and fractionated into cytoplasm and nucleus, then subjected to p65 immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Because endogenous WSTF is lost in senescence, HA-WSTF overexpressed senescent cells were used for co-IP. j, In vitro translated Flag-p65, HA-WSTF, and HA-SNF2H were subjected to Flag immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Note that p65 binds quantitatively more to WSTF than SNF2H. k and l, HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells were subjected to p65 and WSTF IP at the endogenous level, followed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. The western blot experiments shown in i-l were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Loss of WSTF promotes inflammation in mice and cancer.

a, Liver sections 6 days post injection were stained with NRasV12 and WSTF antibodies, followed by imaging. NRasV12-positive cells were highlighted. Note the expression level of WSTF was reduced in the GFP group and increased in the WSTF group. b, Bar graphs showing the percentage of WSTF-positive cells based on NRas positivity. Data presented are mean values from four randomly selected fields, with over 200 cells analysed. Error bars: SD. **** P value < 0.0001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. c and e, Additional representative images of liver sections stained with NRasV12 and CD45 antibodies, imaged under a confocal microscopy. Scale bars are shown as indicated. d, RT-qPCR analyses of liver from the NRas/GFP and NRas/WSTF groups. The relative expression levels of pro-inflammatory genes and immune cell genes were measured. Data are presented as mean values with s.e.m.; 10 mice in each group were used; P values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test and shown in the figure. f, Additional images of liver from NRasV12/GFP and NRasV12/WSTF groups 6 months post injection. Note while the GFP group did not develop liver tumour, all mice in the WSTF group developed liver tumours. g, CCLE analysis of WSTF and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression. Cell lines in the lowest 50% (WSTF-low, n = 171) and highest 50% (WSTF-high, n = 170) of WSTF expression were grouped, and the expression levels of selected inflammatory genes were compared. Box plots display the median (centre line), the 25th and 75th percentiles (box bounds), and the 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers). Data points outside the whiskers are shown as individual dots. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired two-tailed Welch’s t-test (assuming unequal variances). See Materials and Methods for additional details. h and i, RT-qPCR analyses of IL6, IL8 and WSTF in sh-NTC, sh-WSTF #1 (h) and sh-WSTF #2 (i) in cancer cells. Results were normalized to Lamin A/C and presented as mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent samples; exact P values are shown; n.s. non-significant; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. j, HeLa and MDA-MB-231 were stably expressed with non-targeting control (sh-NTC) or sh-WSTF. The cells were harvested and analysed by immunoblotting. The western blot experiments shown in j were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 9 WSTF in acute and chronic inflammation.

a, IMR90 were treated with TNFα (20 ng/mL) and THP-1 were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. b, IMR90 treated with IFNβ were analysed by RT-qPCR. Mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent samples; exact P values are shown; n.s.: non-significant. c-d, cGAS knockout BJ fibroblasts were chronically transfected by ISD (5 μg/mL) (c); IMR90 with MAVS knockdown were chronically transfected by poly I:C (0.25 μg/mL). e-f, BiFC assay in acute and chronic inflammation. g, mCherry-GFP-WSTF ARPE19 were transfected with poly I:C (0.25 μg/mL) chronically. h, IMR90 with FIP200 knockdown were transfected by ISD chronically. i-k, Co-IP in IMR90. l, ATMi rescued WSTF loss in IMR90 under chronic poly I:C or ISD transfection. m, p-ATM in IMR90. n, Sequences of synthesized peptides. o-p, GST-GABARAP pulldown of in vitro translated WSTF with 20 μg/mL competing peptides. q, PHYRE2 prediction of the hydrophobic helix of WSTF aligned with Cav2.2. r, Alphafold2 prediction of WSTF. GABARAP-binding region is highlighted, forming a hydrophobic helix with high confidence (top). ClusPro modelling of GABARAP UDS binding to WSTF helix (bottom). s, UDS and LDS regions on GABARAP and LC3B. t, Co-IP of IMR90 whole cell extracts treated with NLS-cell penetrating peptides in cultured media for 48 h. u, Fractionation control for Fig. 3i. v-w, IMR90 undergoing chronic poly I:C or ISD transfection were treated with NLS-CPP-peptides. Mean values with s.d.; n = 3 biologically independent samples; exact P values are shown; n.s.: non-significant. x, NLS-CPP-WSTF rescued WSTF in senescent IMR90. y, Sequences of mouse peptides. z-aa, Ms NLS-CPP-WSTF rescued WSTF in senescent AML12 and reduced the SASP gene expression. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. The experiments shown in a, c, d-m, o, p, t, u, x, z were repeated independently at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Targeting WSTF in MASH.

a and b, Related to Fig. 4a and b, additional images of WSTF staining of liver samples from control or MASH patients in cohort 1 and 2. c, Immunoblotting analysis of liver samples from mice fed on a chow diet or on the MCDE diet. d, Liver sections from chow diet or MCDE-treated mice were stained with WSTF and LAMP1 antibodies and analysed by a confocal microscopy. The colocalization of WSTF and LAMP1 is highlighted by arrows. WSTF signals in the MCDE group were deliberately overexposed to show the colocalization with LAMP1. e, Experimental design for establishing MASH in mice using MCDE model and scheme for administering peptides. f, Representative immunoblotting analysis of liver samples from mice fed on a chow diet or on the MCDE diet with NLS-CPP treatments. g, Quantifications of f (n = 8 animal samples). Mean and P values are shown; statistical analysis was conducted using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. h, Representative images of IHC staining for WSTF, F4/80, α-SMA, and Sirius Red. i, Quantifications of IHC staining for h. n = 8 animal samples; data were from four randomly selected fields for each mouse. Results shown are the mean values; P values are shown as indicated, calculated by one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. j, RT-qPCR analyses of liver samples. The relative expression levels of pro-inflammatory genes and macrophage genes were measured. Results shown are the mean values; 8 mice in each group were used; P values are shown as indicated, calculated by one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test. k, Liver sections were stained with an IL6 antibody then imaged using a confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Restoring WSTF by AAV in treating MASH.

a, Scheme of synthesized fragments derived from WSTF sequences. b, Flag-tagged GABARAP and 3NLS-tagged human WSTF fragment or vector control were transfected in HEK293T, and were subjected to Flag co-IP. c, IMR90 were transfected with poly I:C chronically. d, co-IP in mouse BMK. e, Senescent primary MEFs were analysed by immunoblotting. f, Liver sections 1 month post retro-orbital injection with AAV2/8 were stained with HA antibody. g, Experimental design for establishing MASH in mice using the CDAA-HFD model and scheme for administering WSTF fragments. h, Immunoblotting of livers. i, Quantification of h. Mean and P values are shown. n (chow)=4, n (CDAA-HFD) = 5 for both 3NLS-mWSTF 407-553-HA and 3NLS-GFP-HA; Data are presented as mean values with s.d.; P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01. j, Representative images of IHC staining for F4/80, α-SMA, and Sirius Red. Quantification is shown in k, n = 8; data were from four randomly selected fields for each mouse. Results are presented as mean with P values. l, RT-qPCR analyses of liver samples. The relative expression levels of pro-inflammatory genes and macrophage genes were measured. Results shown are the mean values; 7 mice in the chow diet group and 8 mice each in AAV2/8 3NLS-mPP6-HA and 3NLS-GFP-HA groups. m, Quantification of Fig. 4e. Mean and P values are shown. n (chow)=4, n (GAN) = 5 for both 3NLS-mWSTF 407-553-HA and 3NLS-GFP-HA; Data are presented as mean values with s.d.; P values were calculated by one-way ANOVA coupled with Dunnett’s post hoc test; exact P values are shown. n, Liver samples from mice fed on a GAN diet with AAV2/8 3NLS-GFP-HA or 3NLS-mWSTF 407-553-HA treatments. Samples were stained with HA and IL6 antibodies, then imaged using a confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 12 NLS-CPP-WSTF peptide reduced chronic inflammation in osteoarthritis.

a and b, IHC analyses for IL6, IL8, and MMP13 using ex vivo cultured cartilage explants. Quantification is shown in b. n = 3; data were from four randomly selected fields for each human sample. Results are presented as mean values with s.e.m. and exact P values. Statistical analysis was conducted using two-tailed Student’s t-test. c, Scheme of experimental design to test NLS-CPPs in chondrocytes of the damaged articular cartilage explants from OA patients. d, Immunoblotting analysis of cytokine levels in the culture media of chondrocytes using indicated antibodies. e and f, MMP13 staining of the cultured chondrocytes. Quantification is shown in f. Results are presented as mean values with s.d. and exact P values; n = 3 biologically independent samples; data were from four randomly selected fields for each sample. Statistical analysis was conducted using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. g, Mice cartilages undergone sham or OA surgery were stained with WSTF and LAMP1 antibodies and analysed by a confocal microscopy. WSTF signals in the OA group were deliberately overexposed to show the colocalization with LAMP1, highlighted by arrows. h, Related to Fig. 5d, additional representative images of IHC for cytokine staining in cartilages using indicated antibodies. Scale bar: 20 μm. i, Related to Fig. 5f, representative images of safranin O staining to evaluate cartilage damage. Scale bar: 200 μm. The diagram in panel c was created in BioRender. Wang, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/0ra48xg.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Fig. 1

Uncropped immunoblot images for the main figures with molecular mass markers indicated.

Supplementary Fig. 2

Uncropped immunoblot images for the extended data figures with molecular mass markers indicated.

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables 1–8.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Eapen, V.V., Liang, Y. et al. WSTF nuclear autophagy regulates chronic but not acute inflammation. Nature 644, 780–789 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09234-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09234-1

This article is cited by

-

Metformin inhibits nuclear egress of chromatin fragments in senescence and aging

Nature Aging (2026)

-

Cytosolic DNA crosstalk in senescence: a new axis of inflammatory signaling?

The EMBO Journal (2025)

-

An anti-inflammatory autophagic target in chronic diseases

Cell Research (2025)