Abstract

Changing atmospheric circulations shift global weather patterns and their extremes, profoundly affecting human societies and ecosystems. Studies using atmospheric reanalysis and climate model data1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 indicate diverse circulation changes in recent decades but show discrepancies in magnitude and even direction, underscoring the urgent need for validation with independent, climate-quality measurements3. Here we show statistically significant changes in tropospheric circulation over the past two decades using satellite-observed, height-resolved cloud motion vectors from the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR)10,11. Upper tropospheric cloud motion speeds in the mid-latitudes have increased by up to about 4 m s−1 decade−1. This acceleration is primarily because of the strengthening of meridional flow, potentially indicating more poleward storm tracks or intensified extratropical cyclones. The Northern and Southern Hemisphere tropics shifted poleward at rates of 0.42 ± 0.22 and 0.02 ± 0.14° latitude decade−1 (95% confidence interval), respectively, whereas the corresponding polar fronts shifted at rates of 0.37 ± 0.31 and 0.31 ± 0.21° latitude decade−1. We also show that the widely used ERA5 (ref. 12) reanalysis winds subsampled to the MISR are in good agreement with the climatological values and trends of the MISR but indicate probable ERA5 biases in the upper troposphere. These MISR-based observations provide critical benchmarks for refining reanalysis and climate models to advance our understanding of climate change impacts on cloud and atmospheric circulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Earth’s atmospheric general circulation regulates our climate and its extremes, such as droughts and cyclone intensities. It embodies a variety of components, including the tropical meridional overturning circulation (that is, the Hadley circulation) and the turbulence-laden westerlies (that is, mid-latitude jets). Understanding natural variations and human-driven trends in the atmospheric general circulation has long been a focus of climate research. Climate models and theoretical arguments project a slowdown of the overturning circulation13, a poleward expansion of the Hadley circulation3 and a poleward shift of mid-latitude westerlies1,2,14,15. However, the projections are highly uncertain. The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models, for instance, show a mean expansion rate in the Hadley cell of both hemispheres of approximately 0.2° latitude decade−1 between 1979 and 2008, but with a large spread of about 0.5° latitude decade−1 among the models8. Evidence for such changes exists in satellite observations and atmospheric reanalysis datasets, but with mixed results in the expansion rates—some reaching as high as 3° latitude decade−1 (ref. 16).

These mixed results arise partly from the diverse metrics used to describe features of the general circulation and the fundamental limitations in the datasets being used. For example, the ‘edge’ of the Hadley cell has been defined with upper-tropospheric or lower-tropospheric quantities. Upper-atmospheric quantities (for example, outgoing longwave radiation) are easily measurable by satellite instruments but have recently been deemed unreliable for quantifying dynamical changes of the general circulation3,8. Recent work therefore uses lower-tropospheric metrics that are more dynamically relevant for measuring tropical expansion, for example, the latitude of zero crossing of the near-surface zonal wind speed that divides the tropical easterlies from the mid-latitude westerlies (hereafter Lat_U0)3,8. Such lower-tropospheric metrics are easily derived from reanalysis datasets, thereby making these datasets the primary source for verifying climate model predictions1,3,8,9. However, this approach has important limitations. Both climate models and atmospheric reanalyses use dynamical models, which are subject to common uncertainties related to parameterized physics17,18,19. Furthermore, reanalyses assimilate observations20 from a changing mix of satellite instruments and sparsely distributed surface and upper-air stations. Data discontinuities, calibration drifts and the evolving nature of the global observing system yield time-dependent biases in the reanalysis that complicate trend detection. Independent global observations are therefore essential for validating circulation changes3.

Here we provide the first, to our knowledge, analysis of the 2000–2020 climatological means and trends in height-resolved cloud motion vectors (CMVs) (placed here into 1-km vertical bins) by the Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR)10,11 aboard the Terra satellite. MISR CMVs hold several advantages for this work. Unlike other satellite Earth science records, Terra maintained an exceptionally stable equator-crossing time for more than 20 years, eliminating diurnal aliasing and avoiding artificial discontinuities from stitching data records of several short-lived satellites21. Critically, MISR CMVs are derived stereoscopically10,22 and, thus, are insensitive to drift in radiometric calibration, yielding an extraordinarily stable record for change detection (Methods). The height and speed of MISR CMVs are highly accurate and have a traceable, self-contained error budget with extensive validation23,24,25,26. Because MISR CMVs are not assimilated into any atmospheric reanalyses, they constitute an independent benchmark for testing model projections and reanalysis-based estimates of circulation change.

Decadal trends in CMVs

Our analysis proceeds with the understanding that CMVs are not representative of all winds at all altitudes at all times. Unlike reanalysis datasets, which do provide a continuous estimate of wind in space and time, CMVs are contingent on cloud being present, providing winds at the cloud-top altitude of a detectable cloud layer at the time and location of MISR observations. Hence, the cloud dependence of the CMV sampling results in a lack of sampling of clear-sky conditions and conditions below cloud top. Still, clouds do occur frequently in the planetary boundary layer, even in fair weather, and only a few small boundary layer cumuli need to be present for the MISR to retrieve a CMV at a resolution of 17.6 × 17.6 km2. Cloud tops (hence CMV samples) in the mid to upper troposphere are often associated with mesoscale to synoptic-scale weather disturbances, such as tropical and extratropical cyclones. The climatology of CMVs is also linked to climatic features such as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and polar fronts27,28. As such, although conditionally sampled, CMVs capture a broad range of components in the atmospheric circulation.

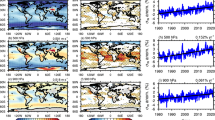

Interpreting trends in MISR CMVs as changes in cloud-top-conditioned circulations requires careful consideration of several potential confounding factors, as described and analysed in the ‘Extended data analyses and discussion’ section in Methods. Our extended data analyses and discussion show that the impacts of these confounding factors on the observed trends are small (Extended Data Figs. 2–4), supporting the conclusion that much of the observed MISR CMV changes (Fig. 1) are because of changes in the cloud-top-conditioned atmospheric circulation. Figure 1 shows the 21-year mean and statistically significant trend of the tropospheric zonal-mean CMVs. This figure is broken down by season in the extended data analyses and discussion. The mean of the CMVs shows key climatological features in the circulation, including the mid-latitude westerly jets (Fig. 1d) and the meridional overturning circulation (Fig. 1g). The wind speed trends are largest in the mid-latitude upper troposphere, in which the CMVs show statistically significant increases of up to about 2 m s−1 decade−1 in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) and about 4 m s−1 decade−1 in the Southern Hemisphere (SH) (Fig. 1a). Figure 1d,g shows both poleward and westerly flow components strengthening for the NH upper troposphere. But in the SH, the poleward flow component strengthens, whereas the westerly flow component weakens. The SH zonal wind weakening between 30 and 50° S is accompanied by an increase in the mid-troposphere zonal wind (U) of roughly 0.5–1.5 m s−1 decade−1 near 60° S. These changes near the SH polar front suggest a poleward shift of the SH westerly flow and mid-latitude storm track, which is consistent with climate model projections and recent findings from atmospheric reanalyses14,15,29. Notably, the overall wind speed increase mainly arises from the meridional wind (V). The strengthening of poleward flow indicated by CMV may be associated with warm conveyor belts or atmospheric rivers embedded in extratropical cyclones, which are key processes involved in mid-latitude extreme precipitation. Together with the overall increase in water vapour content in a warmer atmosphere, the strengthening of poleward wind may contribute to the observed and simulated increases of extreme precipitation15,30,31.

a–i, The mean and trend values of wind speed and their zonal (U, positive eastward) and meridional (V, positive northward) components for CMV (a,d,g), ERA5_MS (b,e,h) and ERA5_AW (c,f,i) during 2000–2020. The black contour lines represent the mean values in m s−1 averaged over the 21-year MISR record. The trends in m s−1 decade−1 are coloured and use a different colour scale for each variable. The trends are calculated with deseasonalized monthly CMV anomalies that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey lines represent the mean tropopause heights averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

In the equatorial regions, CMV trends reveal a pattern potentially indicative of asymmetric Hadley cell changes. The mean CMVs in the equatorial upper troposphere show easterlies (Fig. 1d) with a strong southward component (Fig. 1g), owing to the climatological ascent associated with the ITCZ being approximately 6° N (ref. 32). The trends in CMVs show a moderate increase in the upper-level easterlies in the SH deep tropics. By comparison, the V component of CMVs show stronger and more widespread trends in the deep tropics of both the NH and the SH, with the southward component in the upper troposphere strengthening at a rate of up to about 4 m s−1 decade−1 and the northward component in the lower troposphere strengthening at a rate of up to 2 m s−1 decade−1. The strengthening trend of the upper-tropospheric southward flow is consistent across seasons (Extended Data Figs. 5–8). This pattern in the CMV trends suggests the intensification of the cross-equatorial circulation that contributes to stronger lower-tropospheric convergence and upper-tropospheric divergence near 6° N. This would be consistent with the faster warming of the NH33 and the associated circulation response required by the global energetic constraint34. However, internal climate variability35, such as the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation, within our record could also be a contributing factor.

Consistency with atmospheric reanalyses

To assess the consistency of our findings with atmospheric reanalysis data, we compared the MISR CMV climatology and trends with those from the widely used ERA5 (ref. 12). We sample the ERA5 winds at the times and locations (latitude, longitude and altitude) of MISR CMVs to ensure identical sampling (see Methods). We refer to these samples as ERA5_MS (MISR Sampled). Of course, ERA5 may not be properly representing observed clouds; however, this misrepresentation was assessed in the extended data analyses and discussion and found to have a negligible impact on our findings presented below. We also repeat the analysis using all wind data available (ERA5_AW), that is, irrespective of the presence of cloud, in the ERA5 dataset sampled at 10.30 a.m. local time. ERA5_AW is a means to analyse how cloud-top-conditioned winds differ from all winds and to better connect our analysis to other studies that use reanalysis datasets, albeit using diurnal means1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. When good agreement is found between ERA5_MS and MISR CMV, we cannot reject the circulation and trends in ERA5_AW using the MISR, thereby increasing our confidence in circulation and trends computed using ERA over the MISR record.

Figure 1 shows good agreement between the MISR CMVs and the ERA5_MS winds, for both climatological means and trends between 2000 and 2020. However, there are some notable differences. In the upper troposphere of the deep tropics, the climatological means of the ERA5_MS speeds are smaller than the MISR CMV by about 2 to 8 m s−1. In mid-latitudes, the upper-tropospheric wind speed of ERA5_MS is greater than the MISR CMV by about 1 to 3 m s−1 in the NH and 1 to 2 m s−1 smaller in the SH. These differences are driven primarily by the V component. Because these differences are much larger than the uncertainty in the MISR CMVs (Methods), these findings probably indicate that further improvements to ERA5 are needed to reduce these upper-tropospheric biases—a finding supported by other evidence (see the ‘Extended data analyses and discussion’ section in Methods). The means of ERA5_MS and ERA5_AW also differ, as ERA5_MS are non-random samples (equal to MISR CMV sampling). Compared with ERA5_AW, the climatological MISR CMVs and ERA5_MS shows stronger V component and weaker U component in the mid-latitudes, corresponding to cloudy, poleward air streams embedded in cyclones.

Focusing on decadal trends, the upper-tropospheric mid-latitude jets show similar patterns between the independent MISR CMV and ERA5_MS datasets. They show an increase in cloud motion speed in both hemispheres, a strengthening trend of poleward flow in the mid-latitude upper troposphere, especially in the SH mid-latitude, and an increase in U along the polar front in the SH. But there are also important, statistically significant differences (Extended Data Fig. 1). CMV speed trends are larger by up to about 2 m s−1 decade−1 compared with ERA5_MS in the upper troposphere of the SH and tropics. This is true for the V components as well, except for the marked difference between roughly 20 and 40° S, at which the ERA5_MS V component shows trends that are approximately 4 m s−1 decade−1 weaker than the MISR. Near this region, the ERA5_MS U-component trends are up to 2.5 m s−1 decade−1 larger than the MISR, with ERA5_MS showing a trend of up to +2.5 m s−1 decade−1 just north of about 30° S and MISR CMV showing a trend of −2.5 m s−1 decade−1 just south of about 30° S. Because MISR CMV retrievals are agnostic to location, and as these trend differences are much larger than the uncertainty and stability in MISR CMVs (Methods), we suspect an issue with ERA5—perhaps erroneous trends in the input data assimilated into ERA5 that would affect ERA5_MS trends in the upper troposphere of the SH and tropics.

When we also consider ERA5_AW, the increase in U along the SH polar front is the only common dominant change in the mid-latitudes among the three datasets and has been observed in other reanalysis datasets as well2. The weak trends that appear in the ERA5_AW V component in the mid-latitudes, at which MISR CMV and ERA5_MS show strong poleward trends, suggests a potential compensating trend in the equatorward meridional flow in clear-sky conditions. In the tropical upper troposphere, the trend agreement between ERA5_AW and ERA5_MS V components may be because of the suspected erroneous trends in the inputs to ERA5 noted above.

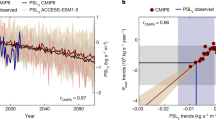

Expansion and migration rates

To assess the expansion rate of the Hadley cells, we apply the Lat_U0 metric to all three datasets using winds in the 0–1-km altitude bin (see Methods). Figure 2a,b shows the time series of deseasonalized monthly anomalies in the latitudinal position of Lat_U0 for the NH and the SH, respectively. The correlation coefficient, r, in the monthly anomalies among these datasets is strong, particularly between the MISR CMV and ERA5_MS in the NH (r = 0.87) and the SH (r = 0.95). The mean monthly values of Lat_U0 (insets in Fig. 2a,b) indicate agreement in the seasonal cycle of the edge of the Hadley cells among the three datasets, but with absolute differences of up to around 2° in latitude. All datasets show a poleward expansion rate of approximately 0.3–0.5 ± 0.2° latitude decade−1 (95% confidence interval (CI)) in the NH and about 0–0.2 ± 0.1° latitude decade−1 (95% CI) in the SH, with only a trend in the NH appearing at a reasonable confidence level based on their low P values (see Methods). These estimates of poleward expansion rate between 2000 and 2020 are in line with multimodel mean values in climate model and other reanalysis model estimates for earlier periods that use the Lat_U0 metric3,8,16, although the potential impact of internal climate variability on individual model simulations and the relatively short observational record should be kept in mind.

a–d, The time series of the deseasonalized monthly anomalies in the latitudinal positions of Lat_U0 for the NH and the SH (a,b) and Lat_Umax for the NH and the SH (c,d). The solid lines across the data series are the least-squares regression lines with their colour matching their corresponding data series, although they are largely overlapping. The slope and its uncertainty (95% CI) for each fitting line are given in the legends, as well as its P value. The insets show the mean monthly values of the latitudinal positions averaged over the 2000–2020 period for each of the three datasets. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

A common lower-tropospheric metric to examine the zonal mean position of the polar front jet is the latitude of the maximum value in monthly mean U (Lat_Umax) at the 850 hPa pressure level5,16. Here we use the 1–2-km altitude bin, at which the 850 hPa pressure level typically resides (see Methods). Figure 2c,d shows the deseasonalized monthly anomalies in the latitudinal position of Lat_Umax. The correlation coefficient in the monthly anomalies among these datasets is excellent, particularly between the MISR CMV and ERA5_MS in the NH (r = 0.98) and the SH (r = 0.99). The mean monthly values of Lat_Umax (insets in Fig. 2c,d) also indicate agreement in the seasonal cycle in the position of the polar front jet, particularly between the MISR CMV and ERA5_MS datasets. From these datasets, we see a poleward migration rate of about 0.3–0.4 ± 0.3° latitude decade−1 (95% CI) in the NH and about 0.3–0.4 ± 0.2° latitude decade−1 (95% CI) in the SH for all three datasets, with trends at only moderate to low confidence levels based on their P values. This low to moderate confidence is consistent with the confidence reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)1.

Discussion and conclusion

Unique to this study is the use of stable and accurate height-resolved CMVs from the MISR to assess climatological values of cloud motion and their variability between 2000 and 2020 (Fig. 1). We show that CMVs have significantly (95% CI) increased in speed in the upper troposphere during this period in both the NH and the SH by up to 2 and 4 m s−1 decade−1, respectively. This speed increase occurs with an increase in meridional flow towards the poles in both hemispheres, but with westerly flows strengthening in the NH and weakening in the SH. This poleward increase in the meridional component of the CMV could indicate an intensification, an increase in moisture transport in the warm sector, a change in the overall structure or a poleward shift in the tracks of extratropical cyclones. Moderately high confidence (P = 0.06) is placed in a poleward expansion of the Hadley circulation in the NH at a rate of 0.42 ± 0.22° latitude decade−1 (95% CI) using the Lat_U0 metric applied to CMVs. No notable expansion was observed in the SH. The Lat_Umax metric applied to CMVs suggests that the clouds associated with the polar jets are migrating poleward at similar rates to each other in both hemispheres, but only with low to moderate confidence levels. When considering CMV changes at all altitudes throughout the tropics, the observations suggest weakening of the Hadley circulation in the NH and strengthening in the SH, the degree to which cannot be quantified with CMVs as they do not represent mass stream functions that are commonly used in assessing circulation strength9.

We provided the first evaluation of systematic errors in ERA5 mean winds and their trends throughout the troposphere against independent, height-resolved MISR CMVs. This evaluation is important because the suitability of reanalysis data for trend detection in atmospheric circulation, in part for validating climate model projections, has raised concerns3. To facilitate a direct comparison, the ERA5 winds have been sampled (ERA5_MS) to match the time and location of MISR CMVs. We show very good agreement between MISR CMVs and ERA5_MS winds. Nonetheless, small but significant differences between MISR CMVs and ERA5_MS are present in the upper troposphere. These differences are much larger than the uncertainties in MISR CMVs, suggesting that the ERA5 data probably suffer systematic biases in the upper troposphere, specifically in the SH and the tropics. Our ERA5_MS cloud-conditional analysis presented in the extended data analyses and discussion also points to potential problems in the ability of ERA5 in representing clouds, raising concerns about using ERA5 for studying one of the key science questions in climate science, namely how clouds and circulation interact36.

Despite some upper-troposphere differences, we show excellent agreement between MISR CMV, ERA5_MS and ERA5_AW in the Hadley cell expansion rates and the polar front migration rates for the 2000–2020 period using the Lat_U0 and Lat_Umax metrics. Excellent agreement among these datasets is also observed in the seasonality of these metrics. Therefore, our findings support the use of MISR CMVs and ERA5 to monitor changes using the Lat_U0 and Lat_Umax metrics that are favoured by the community. However, caution is still recommended when extending this finding beyond this period, particularly moving backwards in time because of the reduced capabilities in our global observing system that are assimilated into ERA5.

The higher level of confidence in MISR wind speed trends in the upper troposphere relative to lower altitudes may suggest that signals of warming-induced circulation changes may first emerge in the upper troposphere, at least in cloudy conditions. ERA5_MS also picks up these trends, but the trends in ERA5_AW (that is, all clear and cloudy winds) are much weaker. This may imply that there is a compensating trend in the meridional flow towards the equator in clear conditions. Together, they may suggest an intensification in the variability of tropical–extratropical transports that make the poleward transport of moisture and heat more extreme. This has important implications for human societies sensitive to precipitation and temperature extremes.

Changes to atmospheric circulations are a critical component of climate change that is already affecting modern society37. Our assessment of these changes in the 2000–2020 period using MISR CMVs provides much-needed benchmarks for reanalysis and climate model datasets. Still, although the MISR is our longest climate-quality record from satellites for height-resolved CMVs, it is still short in light of internal climate variability. Therefore, any discussion in our analysis of change is specific to changes over the past two decades only, which probably contain natural climate variability and human-induced changes. Here we focused on zonal mean CMVs, ignoring the finer regional details important to understanding and quantifying regional impacts2. Given the larger regional internal variability of CMVs, a record longer than the MISR dataset would help detect critically important changes in regional circulations and should be pursued.

Methods

Datasets

This work uses the MISR Cloud Motion Vector (CMV) product (version F02_0002)10 over the period March 2000 to December 2020. The product is not a usual gridded, monthly mean product normally used in climatological studies. Instead, the product contains a simple list of all CMV retrievals for a given month, with each retrieval tagged by latitude, longitude and time. The height-resolved CMVs are obtained through stereoscopic means by tracking the progression of features in the MISR 275-m resolution red-band imagery (380-km swath) over a 3.5-min period between the initial 70° forward view and the nadir view, and again for the 3.5-min period between the nadir view and 70° aft view10. The resolution of the MISR CMV product is 17.6 km × 17.6 km. Our analysis uses only the daytime descending node of the MISR orbit to keep local time consistent within high-latitude grids. The latest versions of MISR cloud-top heights and CMVs have been extensively validated24,25,26. The near-global validation of cloud-top height has been validated against a space-based lidar26, showing a bias ± precision of −280 m ± 370 m. The precision in cloud motion speed is 3.7 m s−1, with biases in U = 0.0 m s−1 and V = 0.3 m s−1 relative to static ground targets and with biases in U and V relative to geostationary-derived CMVs <±0.5 m s−1 (for cloud-top heights at which they have moderate agreement) and possibly up to −1.5 m s−1 for the V component, depending on the method of assessment24,25. The stability of the product is also relevant for trend analysis. Although MISR geometric telemetry needed for stereoscopic retrievals indicate no trends over the operation of the mission (Veljko Jovanovic, personal communication), we nonetheless perform here the first analysis to quantify its stability. The MISR stereographic retrievals are agnostic to the texture being observed, be it from cloud or land surfaces, receiving no prior. Therefore, we use the surface as a stable target for measuring the stability of the MISR TC_Cloud_F0_0001 product22, which is the main input to the CMV product. We analysed cloud-top height and wind retrievals from data flagged as ‘high-confidence near-surface’ by the Stereoscopically-Derived Cloud Mask in the TC_Cloud product, which typically indicate clear sky or the occasional near-surface cloud. Our analysis encompasses 20 years of global land data between 50° N and 50° S as in ref. 26 We conducted a trend analysis on the modes (rather than mean to avoid any possible trend in near-surface clouds) of annual histograms of these retrievals. For the surface heights, the trend is small at 0.54 ± 2.5 m decade−1 (95% CI) and insignificant (P = 0.94). Near-surface wind retrievals also exhibit negligible trends: the U component shows a trend of 0.00 ± 0.01 m s−1 decade−1 (P = 0.94) and the V component indicates a trend of 0.02 ± 0.05 m s−1 decade−1 (P = 0.51). These results confirm the long-term stability and reliability of MISR stereo measurements for climate research.

For the reanalysis model dataset, this study uses hourly data of the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Atmospheric Reanalysis (ERA5)12. We use the U and V components of ERA5 wind, as well as the geopotential, on all of the available 37 pressure levels ranging from 1,000 hpa to 1 hpa. These hourly data are downloaded at a global 0.25° × 0.25° latitude–longitude grid, the highest spatial and temporal resolutions available for the ERA5 archive. Although the quality of ERA5 winds is evaluated against the MISR in the main text, we provide further discussion on ERA5 wind evaluation against other independent datasets below in ‘Extended data analyses and discussion’, showing excellent agreement with the MISR in the very limited regions on which the other datasets report.

Sampled ERA5 at the MISR CMV record (ERA5_MS)

Because the ERA5 data have a spatial-temporal resolution that is comparable with the MISR CMV, we use a nearest-neighbour approach to sample the ERA5 U and V components at the time, location and altitude of each CMV retrieval. The time, latitude and longitude for each MISR CMV retrieval at a 17.6 × 17.6-km resolution are used to find the closest hour and the nearest grid point of the ERA5 data. For a CMV retrieval at a specific height, we locate the nearest ERA5 data point using the geopotential information at pressure levels. Specifically, geopotential heights are calculated by dividing the geopotential values by the Earth’s gravitational acceleration, given by 9.80665 m s−2 (constant). Hence, the sampled ERA5 data (ERA5_MS) have the exact same record length as the MISR CMV data. Wind speed is calculated from the U and V components for each record of CMV and ERA5_MS.

Trend analysis

Before trend analyses, the U, V and wind speed data of MISR CMV and ERA5_MS are first aggregated into monthly, 0.25° × 0.25° latitude–longitude grid boxes. The aggregated data are then sorted into 20 height bins ranging from 0 to 20 km with a bin width of 1 km (with closed left side and opened right side). The mean of all of the 17.6-km retrievals in each grid box and height bin is calculated and stored in an intermediate file, along with the number of the retrievals for each bin. Hence, in one monthly intermediate file, U and V are stored in 720 (latitude) × 1,440 (longitude) × 20 (altitude) bins. For the zonal analysis (Fig. 1), the total number of bins is further reduced to 720 (latitude) × 20 (altitude) bins by averaging the data along the longitudinal dimension excluding the bins with no valid retrievals (for example, owing to high-altitude terrain lying above, say, the 0–1-km altitude bin). The zonal map of the total number of CMV retrievals is given in Extended Data Fig. 2.

To ensure a large sample size, only bins that have a total of more than 5,000 CMV retrievals over the 2000–2020 period are used in the zonal analyses. This effectively removed the low-sample observations of the stratospheric clouds and the associated wind speed, thus keeping the focus of our discussion to the troposphere. As a reference for readers, the mean tropopause heights are plotted in Fig. 1. The mean tropopause heights were derived for the period 2000 and 2020 using the tavgM_2d_slv_Nx product of the Modern-Era Retrospective analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2)38, as tropopause heights are not directly available in ERA5.

The deseasonalized monthly anomalies for each bin are calculated as the deviation from the monthly means averaged over the 2000–2020 period. Trends analysis of the deseasonalized anomalies is conducted by initially applying the nonparametric Mann–Kendall test for the trend and the nonparametric Sen’s method for the magnitude of the trend using the Python package pyMannKendall39. In all analyses and figures involving trend analysis, after performing local significance tests, we applied a tightened false discovery rate (FDR) correction, following the same procedure described in ref. 40. We aimed to control the FDR at a nominal level of 5%; however, the significance threshold was adjusted on the basis of the estimated proportion (50%) of true null hypotheses to maintain this control, as recommended in ref. 40. This adjustment often resulted in a higher nominal significance threshold, increasing the power to detect true effects while ensuring that the expected proportion of false discoveries remained at or below 5%. Grid points with adjusted P values below the adjusted FDR threshold were considered statistically significant.

Calculation of Lat_U0 and Lat_Umax

This study evaluates the tropical width and position of the polar jets using the zonal averages of the U data in the CMV, ERA5_MS and ERA5_AW. We use two metrics from the Tropical-width Diagnostics (TropD) software package41. Using TropD allows for consistency with other studies. Lat_U0 is the latitude at which the zonal-mean U component of the wind in the 0–1-km altitude bin equals zero after linear interpolation between two neighbouring latitude bins. This marks the latitude in the subtropics at which U switches sign from negative (easterly) to positive (westerly). It is calculated using the TropD_Metric_UAS module in TropD with default settings. Lat_Umax is the latitude of maximum zonal-mean U in the 1–2-km altitude bin. It is calculated using the TropD_Metric_EDJ module in TropD. We use the ‘peak’ method (weak smoothing) with the smoothing parameter of n = 6 as recommended in other studies42,43. The other parameters in the module are set with default settings.

Extended data analyses and discussion

Examination of confounding factors

There are potential confounding factors at play when interpreting trends in MISR CMV as trends in speed, namely trends in the number of MISR CMV samples, their within-bin heights in the presence of within-bin vertical gradients in wind speed and their within-bin longitudes in the presence of within-bin horizontal gradients in wind speed.

Extended Data Figure 2 shows the number of CMV samples and their trends in terms of the within-bin percentage change. We see that the observed statistically significant trends in CMV samples are very small, mostly ranging from −0.6 to +0.2% decade−1. There is a decreasing fraction of CMV samples in the upper troposphere and an increasing fraction in the lower troposphere. These should not be compared with cloud-cover changes because a CMV retrieval is not sensitive to the underlying cloud fraction (that is, whether the 17.6 × 17.6-km area is 100% cloudy or 5% cloudy, we still get a CMV sample). Moreover, the positive trend in the lower troposphere is confounded by the decreasing trend in the upper troposphere, as less clouds above leads to more opportunity to retrieve clouds below. The decreasing trend in the upper atmosphere may be related to decreases in the frequency of occurrence of optically thin cirrus that reside near the detectability threshold of MISR stereo26,44. Note that the spatial patterns in the small trends shown in Extended Data Fig. 2b do not match the spatial patterns we see in the trends in Fig. 1a,d,g, which does not support the notion that sample trends alone can explain the trends seen in Fig. 1. Moreover, these small trends in sample numbers would have no impact on trends in cloud-top-conditioned winds without a corresponding shift in the CMV height and longitudinal distributions within the 1-km bin, which we examine next.

The relative change in the CMV height distribution within a 1-km altitude bin and how the heights and winds covary within an altitude bin can produce confounding effects in interpreting MISR CMV trends reported in Fig. 1 as trends in speed. Extended Data Fig. 3 shows the within-bin mean CMV height trend. We see some statistically significant trends that are small, mostly in the 0 to ±40 m decade−1 range. If we consider a moderately large gradient in wind speed with altitude of 5 m s−1 km−1 in the free troposphere (see Fig. 1 mean values), then we estimate 5/1,000 m s−1 m−1 × ±40 m decade−1 = ±0.2 m s−1 decade−1 as an extreme influence of this effect on CMV trends. This is small relative to the wind speed trends discussed with reference to Fig. 1. Moreover, the CMV heights and winds within a 1-km bin are not well correlated, with correlation coefficients <|0.2| for all bins (figure not shown). The poor correlation is as expected because (1) the uncertainty in MISR heights is only about twice as small as the bin width and (2) the uncertainty in the MISR winds is about the same value as we would expect in wind speed changes over a 1-km depth. These two facts were the primary motivators for choosing the 1-km vertical bin width to begin with for our analyses. Also, the spatial patterns in Extended Data Fig. 3 do not match the spatial patterns we see in the trends in Fig. 1a,d,g. Therefore, there is no support that the large MISR CMV trends in Fig. 1 are greatly affected by the confounding effects of changing cloud heights and their covariability with wind within a 1-km altitude bin.

Finally, a longitudinal shift of the MISR CMV samples to a region of different large-scale circulation (for example, a shift from the jet entrance towards the jet core) may also be a confounding factor, even if the large-scale atmospheric circulation does not have a notable trend. We examined whether there are any substantial trends in the centroid of the longitudinal distributions of the CMV samples for each latitude/altitude bin and found that few regions have notable trends (Extended Data Fig. 4), and when they did, these regions do not completely overlap with those shown in Fig. 1. Hence, the trends shown in Fig. 1 cannot be simply attributed to longitudinal shifts in CMV samples.

In summary, the confounding factors discussed above are small or cannot be used to explain the CMV changes in Fig. 1a,d,g. Therefore we cannot reject the notion that the observed MISR CMV changes are mostly attributed to changes in the cloud-top-conditioned atmospheric circulation.

An ERA5 cloud conditional analysis

A non-random sample of the true wind field and its comparison with the same samples reported in ERA5 is sufficient to indicate uncertainty in ERA5 winds, but not a full characterization of the ERA wind uncertainty, as the samples are non-random. This statement is true regardless of the conditioning (for example, true cloud tops only) placed on these non-random samples. These samples could be further examined to help diagnose problems within ERA5 (for example, whether ERA5 placed a cloud top in the right spot). Similarly, MISR CMVs are non-random samples conditioned to observed cloud tops. Differences between MISR CMV and ERA5_MS winds (that is, Fig. 1) would indicate uncertainty in ERA5_MS winds in regions in which differences are much larger than the uncertainty in MISR CMVs, as quantified in Methods. This is true regardless of the cloud-conditioned nature of MISR CMV samples. As discussed in the main text, such notable differences were only observed in certain regions of the upper troposphere.

As a diagnostic, the reader may be curious as to whether these ERA5_MS samples are also ERA5 samples of cloud top. We extract the ERA5 Fraction of Cloud Cover parameter associated with each ERA5_MS wind sample. In a sample-by-sample comparison, we find that 71.2% of the total ERA5_MS samples have a cloud cover > 0 at the altitude of the ERA5_MS sample; the remaining 28.8% are clear (that is, cloud cover = 0). We also use more strict criteria for the ERA5_MS to contain a cloud top: (1) ERA5_MS cloud cover > 0 at the altitude of the ERA5_MS sample and (2) there are no ERA5 clouds above this altitude. Using these criteria, we find that only 10.5% of the total ERA5_MS samples have a cloud top at the same altitude as the MISR CMV. This is stricter than it needs to be because MISR stereo can see through optically thin clouds to retrieve a lower cloud without any degradation in the quality of the retrieval26. Still, the difference between 10.5% and 71.2% is much more than can be explained by the frequency of observed thin high cloud over thicker lower cloud45. Regardless, when we recreated the Fig. 1 ERA5_MS analysis separately using the 10.5% cloud top, 89.5% non-cloud top, 71.2% cloud and 28.8% clear ERA5_MS samples, we found that their differences are not statistically different (95% CI) between each other or against Fig. 1b,e,h.

These results provide strong evidence that MISR CMVs can be used to evaluate ERA5 winds at the times and locations of MISR CMV sampling, regardless of whether ERA5 indicates the presence of a cloud (or cloud top) or not. The results are symptomatic of a large uncertainty in the ERA5 parameterization of cloud physics, particularly in how it relates to the coupling of clouds and circulation. Global models used to generate ERA5 have limitations in fully resolving the fast, fine-scale dynamics in observed moist convection46, even though the assimilation of vast amounts of data effectively constrains the state of slow-varying, large-scale circulation. Although MISR CMVs are inherently tied to observed clouds and could reflect changes in moist convective systems (for example, shifts in intensity or organization affecting cloud motion), ERA5’s parameterized convection and its representation of associated dynamical features such as divergence/convergence may not fully capture these nuances. This could mean that climate-driven changes in moist convection, if present in MISR CMVs, are challenging to isolate or validate using present global reanalyses.

Comparison with other works

It is instructive to compare differences in ERA5_MS wind and MISR CMV reported here to differences in ERA winds against other observations reported in other studies. This is done to gain confidence in our analyses and those reported in other studies.

In one study47, satellite altimeter and scatterometer data were used to validate ERA5 surface winds (10 m) over the Atlantic between 60° N and 60° S. Over this region, they show that ERA5 has zonal surface wind speed relative biases that vary latitudinally between 0 and 0.8 m s−1. Other studies48,49 have compared ERA5 surface winds to land surface station data, most of which were equatorward of 60° latitude. These land station comparisons indicated mean absolute difference with ERA5 surface winds <0.4 m s−1. These results are in line with ERA5_MS biases relative to MISR CMV for the lowest 1-km bin, with results varying latitudinally (and averaged over all longitudes) within the range −0.2 to +0.8 m s−1 between 60° S and 60° N. If we restrict ourselves to 35 to 60° N, at which we have a dense network of land surface stations49, then the latitudinally varying surface wind speed relative biases in this latitude band between MISR CMV and ERA5_MS range from −0.1 to +0.1 m s−1. This improvement is expected given: (1) the dense global network of station data that is assimilated in ERA5 over land within this latitude range and (2) the high accuracy of the MISR CMV product. Over ocean, however, few surface stations data are assimilated into ERA5, so the larger ERA5 wind biases relative to altimeter, scatterometer and MISR data makes sense.

For winds above the surface, this study is the first validation of ERA5 tropospheric winds (cloud-top-conditioned or otherwise) over the globe based on independent observations. However, one study50 using Aeolus51 data over one rawinsonde station in Singapore also evaluated the ERA5 winds. Aeolus is a Doppler wind lidar capable of deriving vertically resolved, zonal winds (that is, U). Using data between 2019 and 2021, they show that the height-resolved, mean zonal winds measured by Aeolus is within ±1.5 m s−1 of ERA5 between the surface and 14 km. Above 14 km, ERA5 reaches a maximum bias relative to Aeolus of +3.5 m s−1 at an altitude of 16.5 km (that is, near the tropopause). We extracted 20 years of MISR CMV U component over Singapore and it showed very similar results, despite being cloud-conditional: within ±1.0 m s−1 of ERA5_MS between 0 and 14 km, with a maximum relative bias of +3.2 m s−1 also at 16.5 km. The similarities are remarkable, which speaks to the very high quality of both Aeolus Doppler winds and MISR CMVs, as well as to the high quality of ERA5 winds at altitudes in the lower to middle troposphere, at least at this tropical location. That study was able to attribute the large relative bias near the tropical tropopause to the poor representation of Kelvin wave dynamics in ERA5, in which reanalyses are known to struggle52. The positive impact that the assimilation of global Aeolus winds had on numerical weather prediction model forecasts, including ECMWF53,54, is further evidence that modelled winds still have room for improvements, particularly in the upper troposphere (that is, where the mean MISR CMV show the largest disagreement with ERA5_MS in Fig. 1).

A comprehensive comparison of the time series of ERA5 tropospheric winds against independent satellite data does not yet exist—the results here with MISR are a first. A time-series analysis with satellite scatterometers is challenging because of the different instruments with different orbit (and orbit drifts) that need to be stitched together. In one study55 that used a blended method with other data to help with some shortcomings in the satellite data, they show trends of surface winds over ocean between 60° N and 60° S between 1992 and 2012. Their results show latitudinal variability in zonal mean trends ranging between −0.2 and +0.2 m s−1 decade−1. In the case of MISR CMVs, ERA5_MS and ERA5_AW, few latitude bins show statistically significant trends in the surface (0–1-km) bin, and where they do, the trends range between −0.2 and +0.2 m s−1 decade−1 (Fig. 1). This is similar to the scatterometer study, recognizing the caveat in the comparison owing to differences in time periods and ocean only.

On the basis of the above comparisons with other studies, we find similar relative biases with ERA5 winds as those reported using the MISR for the very limited regions of the troposphere that these studies cover. These comparisons, along with extensive validation of MISR CMVs that show a highly accurate and stable dataset (see Methods), supports the conclusion that ERA5_MS winds are insignificantly different from MISR CMV in the lower to middle troposphere and have small but significant differences in the upper troposphere, as described in the main text. Discrepancies between MISR CMVs and ERA5_MS, particularly in the tropical upper troposphere, resonate with previously reported limitation in the ECMWF model and ERA5 performance. Independent assessments have identified substantial biases in the ECMWF model’s representation of tropical tropopause wind shear relative to radiosondes56, errors in ERA5 tropical ocean surface winds57 and persistent errors in tropopause-level wind shear in reanalyses58. These findings reinforce the MISR-based evidence that reanalysis wind remains uncertain in dynamically complex regions, particularly in the tropics and near the tropopause, and they highlight the value of using independent, high-quality observations such as MISR CMVs for further model refinements.

Seasonal variability of MISR CMV and ERA5 winds trends

Modelling studies have shown that the patterns and drivers of long-term circulation changes have some seasonality14,59. Hence, we have compared the decadal trends of seasonal means in height-resolved winds (Extended Data Figs. 5–8) against the trends in deseasonalized monthly anomalies (Fig. 1). There is general agreement between the two patterns of trends, except that the level of significance is reduced in seasonal trends, as each seasonal plot has only a quarter of the total data used in Fig. 1. There are only two notable exceptions to this broad agreement.

The first exception is in the strengthening of the U component of the winds along the polar front in the SH seen in Fig. 1—this feature largely disappears in boreal winter (December, January and February) for all three datasets. During December, January and February, stratospheric ozone depletion over the Antarctic regions has been attributed as a mechanism for enhanced poleward shifts in the eddy-driven jet and the SH Hadley cell edge in climate models. This enhanced poleward movement would result in a more meridional flow of wind than zonal in the polar jet and could probably explain the lack of strengthening in the U component over these months.

The second is in the presence of substantial strengthening of the U component in the subtropical jet of the SH seen in the ERA5_MS data but not in the CMV—it is largely absent in the ERA5_MS in the boreal winter (December, January and February), weakened in boreal summer (June, July and August) and very strong in the boreal spring and fall seasons (March, April and May and September, October and November, respectively). Apart from these two exceptions, the lack of strong seasonality in the trends in Fig. 1 implies that whatever is driving the trends is doing so regardless of seasonal forcing.

Data availability

MISR CMV data are publicly available at the NASA Langley Atmospheric Science Data Center (https://asdc.larc.nasa.gov/project/MISR/MI3MCMVN_2). ERA5 hourly data are publicly available from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts and Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/).

Code availability

The analysis scripts are archived at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15453883) and released under the MIT licence60.

References

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Manney, G. L. & Hegglin, M. I. Seasonal and regional variations of long-term changes in upper-tropospheric jets from reanalyses. J. Clim. 31, 423–448 (2018).

Staten, P. W., Lu, J., Grise, K. M., Davis, S. M. & Birner, T. Re-examining tropical expansion. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 768–775 (2018).

Lee, S. H., Williams, P. D. & Frame, T. H. A. Increased shear in the North Atlantic upper-level jet stream over the past four decades. Nature 572, 639–642 (2019).

Gillett, Z. E., Hendon, H. H., Arblaster, J. M. & Lim, E.-P. Tropical and extratropical influences on the variability of the Southern Hemisphere wintertime subtropical jet. J. Clim. 34, 4009–4022 (2021).

Martin, J. E. Recent trends in the waviness of the Northern Hemisphere wintertime polar and subtropical jets. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD033668 (2021).

O’Connor, G. K., Steig, E. J. & Hakim, G. J. Strengthening Southern Hemisphere westerlies and Amundsen Sea Low deepening over the 20th century revealed by proxy-data assimilation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095999 (2021).

Grise, K. M. & Davis, S. M. Hadley cell expansion in CMIP6 models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 5249–5268 (2020).

Chemke, R. & Polvani, L. M. Opposite tropical circulation trends in climate models and in reanalyses. Nat. Geosci. 12, 528–532 (2019).

Mueller, K., Garay, M. J., Di Girolamo, L., Jovanovic, V. & Moroney, C. MISR Cloud Motion Vector Product Algorithm Theoretical Basis. JPL D-64973. https://eospso.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atbd/MISR_L3_CMV_ATBD.pdf (2012).

Diner, D. J. et al. Multi-angle Imaging SpectroRadiometer (MISR) instrument description and experiment overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 36, 1072–1087 (1998).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Simpson, I. R., Shaw, T. A. & Seager, R. A diagnosis of the seasonally and longitudinally varying midlatitude circulation response to global warming. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 2489–2515 (2014).

Lorenz, D. J. & DeWeaver, E. T. Tropopause height and zonal wind response to global warming in the IPCC scenario integrations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D10119 (2007).

Staten, et al. Tropical widening: from global variations to regional impacts. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, 897–904 (2020).

Janjić, T. et al. On the representation error in data assimilation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 144, 1257–1278 (2018).

Morrison, H. et al. Confronting the challenge of modeling cloud and precipitation microphysics. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001689 (2020).

Ferguson, C. R. & Villarini, G. Detecting inhomogeneities in the Twentieth Century Reanalysis over the central United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, D05123 (2012).

Carrassi, A., Bocquet, M., Bertino, L. & Evensen, G. Data assimilation in the geosciences: an overview of methods, issues, and perspectives. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 9, e535 (2018).

Norris, J. R. & Evan, A. T. Empirical removal of artifacts from the ISCCP and PATMOS-x satellite cloud records. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 32, 691–702 (2015).

Mueller, K. J. et al. MISR Level 2 Cloud Product Algorithm Theoretical Basis. JPL D-73327. https://eospso.gsfc.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atbd/MISR_L2_CLOUD_ATBD-1.pdf (2013).

Marchand, R. T., Ackerman, T. P. & Moroney, C. An assessment of Multiangle Imaging Spectroradiometer (MISR) stereo-derived cloud top heights and cloud top winds using ground-based radar, lidar, and microwave radiometers. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, D06204 (2007).

Horváth, Á. Improvements to MISR stereo motion vectors. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5600–5620 (2013).

Mueller, K. J. et al. Assessment of MISR cloud motion vectors (CMVs) relative to GOES and MODIS atmospheric motion vectors (AMVs). J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 56, 555–572 (2017).

Mitra, A., Di Girolamo, L., Hong, Y., Zhan, Y. & Mueller, K. J. Assessment and error analysis of Terra-MODIS and MISR cloud-top heights through comparison with ISS-CATS lidar. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2020JD034281 (2021).

Stewart, R. E., Szeto, K. K., Reinking, R. F., Cloudh, S. A. & Ballard, S. P. Midlatitude cyclonic cloud systems and their features affecting large scales and climate. Rev. Geophys. 36, 245–273 (1998).

Eckhardt, S. et al. A 15-year climatology of warm conveyor belts. J. Clim. 17, 218–237 (2004).

Woollings, T. et al. Trends in the atmospheric jet streams are emerging in observations and could be linked to tropical warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 125 (2023).

Asadieh, B. & Krakauer, N. Y. Global trends in extreme precipitation: climate models versus observations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 19, 877–891 (2015).

Myhre, G. et al. Frequency of extreme precipitation increases extensively with event rareness under global warming. Sci. Rep. 9, 16063 (2019).

Berry, G. & Reeder, M. J. Objective identification of the intertropical convergence zone: climatology and trends from the ERA-Interim. J. Clim. 27, 1894–1909 (2014).

Cowtan, K. & Way, R. G. Coverage bias in the HadCRUT4 temperature series and its impact on recent temperature trends. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 140, 1935–1944 (2014).

Kang, S. M., Frierson, D. M. W. & Held, I. M. The tropical response to extratropical thermal forcing in an idealized GCM: the importance of radiative feedbacks and convective parameterization. J. Atmos. Sci. 66, 2812–2827 (2009).

Deser, C. et al. Uncertainty in climate change projections: the role of internal variability. Climate Dyn. 38, 527–546 (2012).

Bony, S. et al. Clouds, circulation and climate sensitivity. Nat. Geosci. 8, 261–268 (2015).

Reidmiller, D. R. et al. (eds). Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018 (U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2018).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Hussain, et al. pyMannKendall: a python package for non-parametric Mann Kendall family of trend tests. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1556 (2019).

Ventura, V., Paciorek, C. J. & Risbey, J. S. Controlling the proportion of falsely rejected hypotheses when conducting multiple tests with climatological data. J. Clim. 17, 4343–4356 (2004).

Adam, O. et al. The TropD software package (v1): standardized methods for calculating tropical-width diagnostics. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 4339–4357 (2018).

Liu, X., Grise, K. M., Schmidt, D. F. & Davis, R. E. Regional characteristics of variability in the Northern Hemisphere wintertime polar front jet and subtropical jet in observations and CMIP6 models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 126, e2021JD034876 (2021).

Grise, K. M. et al. Regional and seasonal characteristics of the recent expansion of the tropics. J. Clim. 31, 6839–6856 (2018).

Mitra, A. Validation, Trend Analysis & Bias Reduction Through Satellite Fusion of the Cloud-top Height Record from Terra MODIS & MISR. PhD dissertation, Univ. Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2023).

Oreopoulos, L., Cho, N. & Lee, D. New insights about cloud vertical structure from CloudSat and CALIPSO observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 9280–9300 (2017).

King, G. P., Portabella, M., Lin, W. & Stoffelen, A. Correlating extremes in wind divergence with extremes in rain over the tropical Atlantic. Remote Sens. 14, 1147 (2022).

Campos, R. M., Gramcianinov, C. B., de Camargo, R. & da Silva Dias, P. Assessment and calibration of ERA5 severe winds in the Atlantic Ocean using satellite data. Remote Sens. 14, 4918 (2022).

Ramon, J., Lledo, L., Torralba, V., Soret, A. & Doblas-Reyes, F. J. What global reanalysis best represents surface winds? Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 3236–3251 (2019).

Molina, M., Gutierrez, C. & Sanchez, E. Comparison of ERA5 surface wind speed climatologies over Europe with observations from the HadISD dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 4864–4878 (2021).

Banyard, T. P. et al. Aeolus wind lidar observations of the 2019/2020 quasi-biennial oscillation disruption with comparison to radiosondes and reanalysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 2465–2490 (2024).

Stoffelen, et al. The atmospheric dynamics mission for global wind field measurement. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 86, 73–88 (2005).

Flannaghan, T. J. & Fueglistaler, S. Vertical mixing and the temperature and wind structure of the tropical tropopause layer. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 1609–1622 (2014).

Rennie, M. P. et al. The impact of Aeolus wind retrievals on ECMWF global weather forecasts. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 147, 3555–3586 (2021).

Zuo, H., Stoffelen, Rennie, M. & Hasager, C. B. The contribution of Aeolus wind observations to ECMWF sea surface wind forecasts. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD039555 (2024).

Desbiolles, F. et al. Two decades [1992–2012] of surface wind analyses based on satellite scatterometer observations. J. Marine Sci. 168, 38–56 (2017).

Houchi, K. et al. Comparison of wind and wind shear climatologies derived from high-resolution radiosondes and the ECMWF model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, D22102 (2010).

Belmonte Rivas, M. & Stoffelen, A. Characterizing ERA-Interim and ERA5 surface wind biases using ASCAT. Ocean Sci. 15, 831–852 (2019).

Žagar, N. et al. ESA’s Aeolus mission asserts uncertainties in tropical wind shear and wave-driven circulations. ESS Open Archive https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar.173776264.46417622/v1 (2025).

Zhang, G. Amplified summer wind stilling and land warming compound energy risks in Northern Midlatitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 20, 034015 (2025).

Zhao, G. Code archive for Nature MS 2024-10-22368A-Z. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15453884 (2025).

Acknowledgements

L.D., G. Zhao, J.L. and A.M. acknowledge the support from the MISR project through the Jet Propulsion Laboratory of the California Institute of Technology (contract no. 1474871). G. Zhang is supported by the US National Science Foundation award 2327959. We thank Y. Hong for providing the tropopause height data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.D. conceived and designed this study. G. Zhao carried out the data analysis. L.D. and G. Zhao drafted the manuscript, with input from G. Zhang, Z.W., J.L. and A.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Paul Staten and Ad Stoffelen for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Regions in which CMV and ERA5-MS wind trends substantially differ.

The mean and trend values of wind speed and their zonal (U, positive eastward) and meridional (V, positive northward) components for CMV (a,c,e) and ERA5_MS (b,d,f) during 2000–2020, shown only for grid cells in which trends derived from CMV differ markedly from ERA5-MS trends at greater than 95% confidence level assessed using a standard Z-test. The black contour lines represent the mean values in m s−1 averaged over the 21-year MISR record. The trends in m s−1 decade−1 are coloured and use a different colour scale for each variable. The trends are calculated with deseasonalized monthly CMV anomalies that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey lines represent the mean tropopause heights averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CMV sampling density and its decadal change.

a,b, The total number of CMV retrievals obtained during 2000–2020 (a) and their trends in percentage decade−1 (b). The bins with the total number of retrieves fewer than 5,000 are shown as white. The trends are calculated using deseasonalized monthly anomalies of CMV retrievals that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey line represents the mean tropopause height averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Trends in CMV cloud-top height by latitude and altitude.

Vertical and latitudinal distribution of trends in cloud-top height within each bin from the MISR CMV product during 2000–2020. Trends (in m decade−1) are calculated using deseasonalized monthly anomalies of cloud-top heights that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey line represents the mean tropopause height averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Trends in the longitudinal centroid of CMV samples.

Trends in the centroid of the longitudinal distributions of the CMV samples during 2000–2020. Only values passing the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level are shown. The grey line represents the mean tropopause height averaged between 2000 and 2020. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Boreal winter (December, January, February) wind climatology and decadal trends.

The mean and trend values of wind speed and their zonal (U, positive eastward) and meridional (V, positive northward) components for CMV (a,d,g), ERA5_MS (b,e,h) and ERA5_AW (c,f,i) for December, January and February only over the 2000–2020 period. The black contour lines represent the mean values in m s−1 averaged over the 21-year MISR record. The trends in m s−1 decade−1 are coloured and use a different colour scale for each variable. The trends are calculated with deseasonalized monthly CMV anomalies that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey lines represent the mean tropopause heights averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Boreal spring (March, April, Mau) wind climatology and decadal trends.

The mean and trend values of wind speed and their zonal (U, positive eastward) and meridional (V, positive northward) components for CMV (a,d,g), ERA5_MS (b,e,h) and ERA5_AW (c,f,i) for March, April and May only over the 2000–2020 period. The black contour lines represent the mean values in m s−1 averaged over the 21-year MISR record. The trends in m s−1 decade−1 are coloured and use a different colour scale for each variable. The trends are calculated with deseasonalized monthly CMV anomalies that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey lines represent the mean tropopause heights averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Boreal summer (June, July, August) wind climatology and decadal trends.

The mean and trend values of wind speed and their zonal (U, positive eastward) and meridional (V, positive northward) components for CMV (a,d,g), ERA5_MS (b,e,h) and ERA5_AW (c,f,i) for June, July and August only over the 2000–2020 period. The black contour lines represent the mean values in m s−1 averaged over the 21-year MISR record. The trends in m s−1 decade−1 are coloured and use a different colour scale for each variable. The trends are calculated with deseasonalized monthly CMV anomalies that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey lines represent the mean tropopause heights averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Boreal autumn (September, October, November) wind climatology and decadal trends.

The mean and trend values of wind speed and their zonal (U, positive eastward) and meridional (V, positive northward) components for CMV (a,d,g), ERA5_MS (b,e,h) and ERA5_AW (c,f,i) for September, October and November only over the 2000–2020 period. The black contour lines represent the mean values in m s−1 averaged over the 21-year MISR record. The trends in m s−1 decade−1 are coloured and use a different colour scale for each variable. The trends are calculated with deseasonalized monthly CMV anomalies that have passed the tightened FDR correction at the 5% level. The grey lines represent the mean tropopause heights averaged between 2000 and 2020. See Methods for details. Data: MISR CMV (version F02_0002)10 and ERA5 reanalysis data12.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Girolamo, L., Zhao, G., Zhang, G. et al. Decadal changes in atmospheric circulation detected in cloud motion vectors. Nature 643, 983–987 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09242-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09242-1