Abstract

Remodelling plant immune receptors has become a vital strategy for creating new disease resistance traits to combat the growing threat of plant pathogens to global food security and environmental sustainability1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, current methods are constrained by the rapid evolution of plant pathogens and often lack broad-spectrum and durable protection. Here we report an innovative strategy to engineer broad-spectrum, durable and complete disease resistance in plants through expression of a chimeric protein containing a flexible polypeptide coupled with a single or dual conserved pathogen-originated protease cleavage site fused in frame to the N terminus of an autoactive nucleotide-binding and leucine-rich-repeat immune receptor (NLR) containing a coiled-coil or RESISTANCE TO POWDERY MILDEW 8-like coiled-coil domain. Following invasion, pathogen-originated specific proteases cleave the inactive chimeric protein to form free autoactive NLR, triggering broad-spectrum plant disease resistance. We demonstrate that a single engineered NLR can confer broad-spectrum and complete resistance against multiple potyviruses. Given that many pathogenic organisms across kingdoms encode proteases, this strategy has the potential to be exploited to control viruses, bacteria, oomycetes, fungi, nematodes and pests in plants.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Sequence data can be found in the GenBank/UniProtKB/SwissProt database under the following accession numbers: Tm-22 (AAQ10736.1), AtNRG1.1 (Q9FKZ1.1) and NbNRG1 (Q4TVR0). All data are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Uncropped gel and immunoblot images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, H. & Wang, S. Rice versus Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae: a unique pathosystem. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 16, 188–195 (2013).

Saile, S. C. & El Kasmi, F. Small family, big impact: RNL helper NLRs and their importance in plant innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011315 (2023).

Balint-Kurti, P. The plant hypersensitive response: concepts, control and consequences. Mol. Plant Pathol. 20, 1163–1178 (2019).

Segretin, M. E. et al. Single amino acid mutations in the potato immune receptor R3a expand response to Phytophthora effectors. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 27, 624–637 (2014).

Giannakopoulou, A. et al. Tomato I2 immune receptor can be engineered to confer partial resistance to the oomycete Phytophthora infestans in addition to the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 28, 1316–1329 (2015).

De la Concepcion, J. C. et al. Protein engineering expands the effector recognition profile of a rice NLR immune receptor. eLife 8, e47713 (2019).

Cesari, S. et al. New recognition specificity in a plant immune receptor by molecular engineering of its integrated domain. Nat. Commun. 13, 1524 (2022).

Farnham, G. & Baulcombe, D. C. Artificial evolution extends the spectrum of viruses that are targeted by a disease-resistance gene from potato. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18828–18833 (2006).

Harris, C. J., Slootweg, E. J., Goverse, A. & Baulcombe, D. C. Stepwise artificial evolution of a plant disease resistance gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 21189–21194 (2013).

Chapman, S. et al. Detection of the virulent form of AVR3a from Phytophthora infestans following artificial evolution of potato resistance gene R3a. PLoS ONE 9, e110158 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. The synthetic NLR RGA5HMA5 requires multiple interfaces within and outside the integrated domain for effector recognition. Nat. Commun. 15, 1104 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. A designer rice NLR immune receptor confers resistance to the rice blast fungus carrying noncorresponding avirulence effectors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2110751118 (2021).

Maidment, J. H. R. et al. Effector target-guided engineering of an integrated domain expands the disease resistance profile of a rice NLR immune receptor. eLife 12, e81123 (2023).

Bentham, A. R. et al. Allelic compatibility in plant immune receptors facilitates engineering of new effector recognition specificities. Plant Cell 35, 3809–3827 (2023).

Zdrzałek, R. et al. Bioengineering a plant NLR immune receptor with a robust binding interface toward a conserved fungal pathogen effector. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2402872121 (2024).

Kourelis, J., Marchal, C., Posbeyikian, A., Harant, A. & Kamoun, S. NLR immune receptor–nanobody fusions confer plant disease resistance. Science 379, 934–939 (2023).

Kim, S. H., Qi, D., Ashfield, T., Helm, M. & Innes, R. W. Using decoys to expand the recognition specificity of a plant disease resistance protein. Science 351, 684–687 (2016).

Adachi, H. et al. An N-terminal motif in NLR immune receptors is functionally conserved across distantly related plant species. eLife 8, e49956 (2019).

Wang, J., Han, M. & Liu, Y. Diversity, structure and function of the coiled-coil domains of plant NLR immune receptors. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 63, 283–296 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Plant NLR immune receptor Tm-22 activation requires NB-ARC domain-mediated self-association of CC domain. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008475 (2020).

Collier, S. M., Hamel, L. P. & Moffett, P. Cell death mediated by the N-terminal domains of a unique and highly conserved class of NB-LRR protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 918–931 (2011).

Maekawa, T. et al. Coiled-coil domain-dependent homodimerization of intracellular barley immune receptors defines a minimal functional module for triggering cell death. Cell Host Microbe 9, 187–199 (2011).

Bi, G. et al. The ZAR1 resistosome is a calcium-permeable channel triggering plant immune signaling. Cell 184, 3528–3541 (2021).

Jacob, P. et al. Plant “helper” immune receptors are Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channels. Science 373, 420–425 (2021).

Förderer, A. et al. A wheat resistosome defines common principles of immune receptor channels. Nature 610, 532–539 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. Activation of the helper NRC4 immune receptor forms a hexameric resistosome. Cell 187, 4877–4889 (2024).

Kawano, Y. et al. Palmitoylation-dependent membrane localization of the rice resistance protein Pit is critical for the activation of the small GTPase OsRac1. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 19079–19088 (2014).

Chen, T. et al. Antiviral resistance protein Tm-22 functions on the plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 173, 2399–2410 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Reconstitution and structure of a plant NLR resistosome conferring immunity. Science 364, eaav5870 (2019).

Bieri, S. et al. RAR1 positively controls steady state levels of barley MLA resistance proteins and enables sufficient MLA6 accumulation for effective resistance. Plant Cell 16, 3480–3495 (2004).

Bendahmane, A., Farnham, G., Moffett, P. & Baulcombe, D. C. Constitutive gain-of-function mutants in a nucleotide binding site–leucine rich repeat protein encoded at the Rx locus of potato. Plant J. 32, 195–204 (2002).

Roberts, M., Tang, S., Stallmann, A., Dangl, J. L. & Bonardi, V. Genetic requirements for signaling from an autoactive plant NB-LRR intracellular innate immune receptor. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003465 (2013).

Rairdan, G. J. & Moffett, P. Distinct domains in the ARC region of the potato resistance protein Rx mediate LRR binding and inhibition of activation. Plant Cell 18, 2082–2093 (2006).

Rodamilans, B., Shan, H., Pasin, F. & García, J. A. Plant viral proteases: beyond the role of peptide cutters. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 666 (2018).

Yatsuda, A. P. et al. Identification of secreted cysteine proteases from the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus detected by biotinylated inhibitors. Infect. Immunity 74, 1989–1993 (2006).

Figaj, D., Ambroziak, P., Przepiora, T. & Skorko-Glonek, J. The role of proteases in the virulence of plant pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 672 (2019).

De Wit, P., Testa, A. C. & Oliver, R. P. Fungal plant pathogenesis mediated by effectors. Microbiol. Spectr. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0021-2016 (2016).

Furch, A. C., van Bel, A. J. & Will, T. Aphid salivary proteases are capable of degrading sieve-tube proteins. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 533–539 (2015).

Zhang, Q. et al. Two Phytophthora parasitica cysteine protease genes, PpCys44 and PpCys45, trigger cell death in various Nicotiana spp. and act as virulence factors. Mol. Plant Pathol. 21, 541–554 (2020).

Qin, L., Ding, S. & He, Z. Compositional biases and evolution of the largest plant RNA virus order Patatavirales. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 240, 124403 (2023).

Revers, F. & García, J. A. Molecular biology of potyviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 92, 101–199 (2015).

Palani, S. N., Sankaranarayanan, R. & Tennyson, J. Comparative study of potyvirid NIa proteases and their cleavage sites. Arch. Virol. 166, 1141–1149 (2021).

Adams, M. J., Antoniw, J. F. & Beaudoin, F. Overview and analysis of the polyprotein cleavage sites in the family Potyviridae. Mol. Plant Pathol. 6, 471–487 (2005).

Merits, A. et al. Proteolytic processing of potyviral proteins and polyprotein processing intermediates in insect and plant cells. J. Gen. Virol. 83, 1211–1221 (2002).

Zhang, H., Zhao, J., Liu, S., Zhang, D. P. & Liu, Y. Tm-22 confers different resistance responses against tobacco mosaic virus dependent on its expression level. Mol. Plant 6, 971–974 (2013).

Zhu, M. et al. The intracellular immune receptor Sw-5b confers broad-spectrum resistance to tospoviruses through recognition of a conserved 21-amino acid viral effector epitope. Plant Cell 29, 2214–2232 (2017).

Slootweg, E. et al. Nucleocytoplasmic distribution is required for activation of resistance by the potato NB-LRR receptor Rx1 and is balanced by its functional domains. Plant Cell 22, 4195–4215 (2010).

Wu, C. H. et al. NLR network mediates immunity to diverse plant pathogens. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8113–8118 (2017).

Case, A. J. et al. Mapping stripe rust resistance in a BrundageXCoda winter wheat recombinant inbred line population. PLoS ONE 9, e91758 (2014).

Li, B., Sun, C., Li, J. & Gao, C. Targeted genome-modification tools and their advanced applications in crop breeding. Nat. Rev. Genet. 25, 603–622 (2024).

Ge, X. et al. Efficient genotype-independent cotton genetic transformation and genome editing. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 65, 907–917 (2023).

Yin, J. et al. A cell wall-localized NLR confers resistance to soybean mosaic virus by recognizing viral-encoded cylindrical inclusion protein. Mol. Plant 14, 1881–1900 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Yan (Ningbo University) for providing ChiVMV and PepMoV, X. Zhang (Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for TuMV-GFP, X. Li (Shandong Agricultural University) for PVY-GFP, H. Guo (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for PPV-GFP and J.-M. Zhou (Yazhouwan National Laboratory) for the 35S::AvrRpt2 clone. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32130086, 32430085, 32172360 and 32200118), a Biological Breeding-National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD04077) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1400400 and 2022YFD1400800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. conceived the research. Y.L. and J.W. designed the experiments. J.W. and T.C. constructed expression plasmids. J.W., Z.Z., M.S., T.S. and X.W. preformed N. benthamiana-related experiments including plant transformation and confirmation of transgenic resistance, with assistance from T.C., X.Z., K.S., Y.W. and T.Q. X.G. and F.L. generated transgenic soybean plants. J.W. tested viral resistance in transgenic soybean plants with assistance from K.X. The manuscript was written by Y.L., J.W. and Y.H. with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.L. and J.W. have filed a patent application covering the entire content of this study (patent applicant: Tsinghua University; inventors: Yule Liu, Junzhu Wang; application no.: PCT/CN2025/075120). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

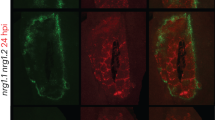

Extended Data Fig. 1 Expression and traits of transgenic plants of HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22.

a, Transient expression of either NIaPVY-Myc or NIa-ProTuMV-Myc caused cell death in T0 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 plants (lines 3 and 5), but not in wild-type (WT) plants at 2 days post agroinfiltration. Bar is 2 cm. b, Successful expression of Myc-tagged proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting. Loading of total protein samples for analyses are shown (lower panel). Sizes and positions of protein markers are indicated. c, T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 plants of two independent lines showed no developmental defects. Bar is 5 cm. d, No significant trait difference between wild-type and transgenic plants. Height and fresh weight were measured when the plants are 3 months old, and seed setting indicated by numbers of seed pods were measured when the plants are 4 months old. “ns” means no significance as determined by two-sided Student’s t tests (n = 6 biologically independent samples). Data are represented as mean ± s.d. e, Transgene and protein expression of the HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 chimeric protein were detected by genomic PCR (upper panel) and immunoblotting (middle panel) in three independent individuals of T1 plants from two independent transgenic lines 3 and 5. Loading of total protein samples for analyses are shown (lower panel). Sizes and positions of DNA (upper panel) and protein markers (middle and lower panels) are indicated. f, Cleavage of HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 by Myc-NIa-ProPVY in T1 transgenic plants. Myc-NIa-ProPVY and AvrRpt2-Myc were expressed at the left or right halves of the same leaves from the transgenic plants. Wide-type leaf tissues without agroinfiltration served as negative controls. Total proteins were extracted and analyzed. NLR proteins and proteases were detected by anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 2 HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 confers resistance against PVY-GFP.

a, Inoculated leaves under normal light (left panel) and ultra-violet light (right panel) at 7 dpi by PVY-GFP. Leaves of WT, 3-T1 and 5-T1 came from the same plants showed in Fig. 1g. HR lesions are indicated (arrows). Bar is 2 cm. b, c, Inoculated leaves showed HR lesions at 7 dpi (b), but whole plant showed systemic hypersensitive response (SHR) at 21 dpi (c) for a few T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 plant infected by PVY-GFP. Wild-type plant was used as control. The bar is 2 cm and 5 cm in panels b and c, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 confers resistance against potyviruses.

a-d, Leaves of T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 plants were inoculated with TuMV-GFP (a), PPV-GFP (b), PepMoV (c) and ChiVMV (d), respectively, and photographed at 7 dpi. HR lesions are indicated (arrows) in T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aTm-22 plants inoculated with PepMoV (c). Bar is 2 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Confirmation of expression in transgenic plants of HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1.

a, NIaPVY-Myc caused cell death in the leaf of T0 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants. b, T1 transgenic plants of line 1 grew and developed normally. c, Transgene and HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 protein were detected by genomic PCR and immunoblotting in three independent individuals of T1 plants of transgenic line 1.

Extended Data Fig. 5 HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 confers resistance against multiple potyviruses.

a, Inoculated leaves of wild-type and T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants challenged with PVY-GFP. Photographs were taken under normal light and UV light at 7 dpi. HR lesions are indicated (arrows). Bar is 2 cm. b, Systemic tissues of PPV-inoculated WT and transgenic plants at 7 dpi. Bar = 5 cm. c, Inoculated leaves of T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants co-infected with TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV and wild-type plants infected with each of the four individual potyviruses. Two halves of one leaf of the transgenic plant were infected with TuMV-GFP and PPV-GFP, respectively. Two halves of another leaf of the same transgenic plant were infected with PepMoV and ChiVMV, respectively. One half leaf from different wild-type plants was infected with TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV, separately. Leaf photographs were taken at 7 dpi. HR lesions are indicated (arrows). Bar = 2 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 6 HA-PCSPVY-aNLR failed to confer resistance against TEV.

a, Co-expression of HA-PCSPVY-aNLR with PVY NIa-Myc, but not TEV NIa-Myc, caused cell death. Photograph was taken at 3 days post agroinfiltration. b, TEV-GFP spread over WT and T1 transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants of line 1 at 7 dpi. c, RT-PCR detected the presence of TEV RNA in WT and transgenic HA-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants at 7 dpi by TEV-GFP. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Confirmation of expression and resistance in transgenic plants of HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1.

a, T1 transgenic HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants from line 3 showed no abnormal development. b, Transgene and its protein expression were detected by genomic PCR and immunoblotting in three independent individual T1 plants of line 3. c, d, The inoculated leaves of T1 transgenic HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants were photographed under normal light and UV light at 7 days post infection with PVY-GFP (c) and TEV-GFP (d). Bar is 2 cm.

Extended Data Fig. 8 HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 confers resistance against multiple potyviruses.

a, The inoculated leaves of T1 transgenic HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants infected with TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV. HR lesions are indicated with arrows. Photographs were taken at 7 dpi. Bar is 2 cm. b, T1 transgenic HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants showed resistance against co-infection of TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV. T1 transgenic plants were co-infected with all four potyviruses TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV. Two halves of one leaf of the transgenic plant were infected with TuMV-GFP and PPV-GFP, respectively. Two halves of another leaf of the same transgenic plant were infected with PepMoV and ChiVMV, respectively. One half leaf from different wild-type plants was infected with TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV, separately. Photographs were taken at 21 dpi. Bar is 5 cm. c, RT-PCR showed that no viral RNA was detected in the systemic leaves of T1 transgenic HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants co-infected by TuMV-GFP, PPV-GFP, PepMoV and ChiVMV.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Some transgenic HA-PCSTEV-PCSPVY-aAtNRG1.1 plants showed systemic hypersensitive response (SHR) upon TEV-GFP infection.

a, The inoculated leaves and whole plants were photographed under normal light and UV light at 7 and 21 dpi respectively. b, The enlarged view of top tissues accompanied with SHR at 21 dpi. c, RT-PCR showed that small amount of TEV RNA was detected in the systemic leaves of SHR plants.

Extended Data Fig. 10 HA-PCSSMV-aAtNRG1.1 confers resistance against SMV in T1 transgenic soybean plants.

a, Expression of HA-PCSSMV-aAtNRG1.1 was confirmed in T1 transgenic soybean plants. b, The top view of uninoculated WT, inoculated T1 and WT plants at 66 days post infection of SMV-eGFP. Bar is 5 cm. c, Inoculated leaves of SMV-eGFP were shown. Bar = 2 cm. d, Agronomic traits of wild-type and T1 transgenic soybean plants. Plant height, seed setting (seedpod number and seed number) and yield (seed weight) per plant are shown. Two-sided Student’s t-tests (n = 4 biologically independent samples) were performed. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. “ns” denotes no statistically significant difference, while *** (p < 0.001) indicates a highly significant difference as assessed by Student’s t-tests. P values are shown in the Source Data.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Fig. 1

This file contains all uncropped blots and gel images.

Supplementary Tables 1–3

Supplementary Table 1. NIa protease cleavage sites between NIb and CP among 199 versus 110 analysed potyviruses follow XXVXXQ↓A(G/S) versus XXVXHQ↓A(G/S). Supplementary Table 2. NIa protease cleavage sites in polyproteins encoded by seven potyviruses in this paper. Supplementary Table 3. Primers used in this study.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Chen, T., Zhang, Z. et al. Remodelling autoactive NLRs for broad-spectrum immunity in plants. Nature 645, 737–745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09252-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09252-z

This article is cited by

-

Advances in genetic and molecular mechanisms of crop resistance to stalk rot

Stress Biology (2026)

-

Expanding disease resistance: engineered NLRS for broad-spectrum protection

Molecular Horticulture (2025)

-

Broad-spectrum plant immunity: engineering pathogen protease-activated autoactive NLRs

Cell Research (2025)

-

An artificial immune switch system: engineering durable, broad-spectrum disease resistance in plants

Science China Life Sciences (2025)

-

Engineering of autoactive NLRs: a big step toward breeding crops with durable and broad-spectrum resistance

Advanced Biotechnology (2025)