Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is an aggressive and highly therapy-resistant brain tumour1,2. Although advanced disease has been intensely investigated, the mechanisms that underpin the earlier, likely more tractable, stages of GBM development remain poorly understood. Here we identify axonal injury as a key driver of GBM progression, which we find is induced in white matter by early tumour cells preferentially expanding in this region. Mechanistically, axonal injury promotes gliomagenesis by triggering Wallerian degeneration, a targetable active programme of axonal death3, which we show increases neuroinflammation and tumour proliferation. Inactivation of SARM1, the key enzyme activated in response to injury that mediates Wallerian degeneration4, was sufficient to break this tumour-promoting feedforward loop, leading to the development of less advanced terminal tumours and prolonged survival in mice. Thus, targeting the tumour-induced injury microenvironment may supress progression from latent to advanced disease, thereby providing a potential strategy for GBM interception and control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

GBM, the most common and malignant primary brain cancer, remains incurable, with a median survival of 12–18 months1. This poor prognosis is compounded by a range of debilitating symptoms, including physical impairments and cognitive decline5. As these typically occur at a late disease stage, most GBMs are already advanced at diagnosis1,5. This represents a major obstacle to treatment, as advanced tumours are characterized by pervasive molecular and cellular heterogeneity, extensive infiltration and immune suppression; all factors that underpin therapy resistance2,6,7,8,9.

GBM research has traditionally focussed on these advanced tumours, largely due to limited access to surgical specimens at other disease stages and sites beyond the main tumour mass, or bulk10. By contrast, much less is known about the earlier stages of GBM development and the mechanisms that drive its progression to advanced therapy-resistant disease.

The late presentation of GBM has also led to the assumption that disease initiation and early phase progression is a rapid process1. However, it is notable that a proportion of GBMs are found incidentally at a presymptomatic stage, or present in a more indolent manner1,11,12,13,14,15. In such cases, the lesions are frequently smaller, more diffuse and non-necrotic masses, which tend to progress to advanced disease after a latent period11,12,13,14,15. This suggests that GBM initiation may include a latent preclinical phase that later progresses to advanced disease, at least in part through cooperating tumour-extrinsic signals.

Alongside oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), neural stem cells (NSCs) and progenitor cells of the subventricular zone (SVZ) have been identified as frequent GBM cells of origin16,17,18. Studies in mice and patients suggest that, after acquisition of driver mutations, SVZ neural precursors exit the neurogenic niche and form tumours at distal sites16,17,18. However, the nature of these distal microenvironments and tumour-promoting factors that may act within them to drive GBM progression remain poorly understood.

Here we combined tissue analysis of early disease stages in somatic mouse models with spatial transcriptomics (ST) analysis of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models and human tissue to examine tumour-promotion mechanisms in glioma. Notably, we found a critical early role for axonal injury, which triggers Wallerian degeneration (WD), a major active programme of axonal death3. We show that genetic inactivation of Sarm1, the main effector of WD4, preserves axonal integrity in GBM models, thereby both suppressing tumour progression and improving neurological function.

Tumorigenesis occurs in WM

To explore early gliomagenesis, we used disease-relevant somatic mouse models of GBM19,20. In this system, endogenous SVZ NSCs are transformed through inactivation of the tumour suppressors Nf1, Pten and Trp53 (hereafter, the npp model), a well-established combination of human GBM driver mutations18,19,20,21,22 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Targeted NSCs are constitutively labelled with a tdTomato fluorescent reporter, enabling analysis of tumour development from the acquisition of mutations to terminal disease. We used immunohistochemistry to carry out a time-course analysis of the impact of driver mutations on NSCs and their progeny, comparing brain tissue collected at early (<8 weeks after induction), intermediate (8–12 weeks after induction), late (12–15 weeks after induction) and terminal (>15 weeks after induction, corresponding to animals reaching humane end points) disease stages. As targeted NSCs exited the SVZ, they preferentially colonized the surrounding white matter (WM) as judged by a greater proportion of tdTomato+ cells co-localizing with the myelin marker myelin basic protein (MBP), relative to MBP− grey matter (GM) regions at the early and intermediate stages (Fig. 1a,b). This was a stark difference given that the WM accounts for only 20% of tumour-infiltrated brain tissue during this period (Extended Data Fig. 1b). This was not a technical artifact because, in animals electroporated with tdTomato alone, NSCs continued to predominantly generate neuroblasts destined for the olfactory bulb (Extended Data Fig. 1a,c,d). These early differences in tumour cell distribution progressively decreased at later disease stages, resulting in tumour cells being more frequently located in GM in terminal lesions and correlating with extensive myelin disruption (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1b). Notably, tumour cell proliferation remained unchanged between WM and GM across tumour development (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1e). Instead, all tumour cells initially proliferated at a low rate regardless of location (around 1–2%), before entering a rapid proliferative phase (around 15%) in late and terminal tumours, as previously described23,24 (Fig. 1b). Longitudinal analysis of a panel of four PDXs revealed a similar WM tropism in early lesions, indicative of conserved mechanisms between mouse and human models (Extended Data Fig. 1f,g). Together, these findings suggest that changes induced by early tumour cells within the WM microenvironment may drive glioma progression from latent to more advanced disease.

a, Time-course analysis of npp tumour development. Tumour cells are tdTomato+ (tdTom, red); MBP (cyan) denotes WM; and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The dashed boxes denote regions shown at higher magnification in the insets. Scale bars, 1 mm (main image) and 100 μm (inset). n = 4 (early), n = 4 (intermediate), n = 4 (late) and n = 3 (terminal) mice. b, Quantification of the percentage of tdTomato+ tumour cells located in WM (blue dots) or GM (grey dots) within the striatum of npp tumour-bearing mice shown in a. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction (comparison of the percentage of tdTomato+ tumour cells in WM versus GM); comparison of the distribution of tdTomato+ cells between early, intermediate, late and terminal stage. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 4 (early), n = 4 (intermediate), n = 4 (late) and n = 3 (terminal) mice. P = 0.0041 (intermediate versus late), P < 0.0001 (all other comparisons). c, Quantification of the proportion of proliferating tdTomato+ cells in the WM or GM expressed as the percentage of Ki-67+tdTomato+ cells of total tdTomato+ cells in each region. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 4 (early), n = 4 (intermediate), n = 4 (late) and n = 3 (terminal) mice. P < 0.0001 (early versus late and intermediate versus late), P = 0.003 (early versus terminal) and P = 0.0022 (intermediate versus late). ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01.

Developing tumours induce axonal injury

To examine WM-specific microenvironmental changes during disease progression in detail, we used ST in a panel of genetically heterogenous PDX models collected at early or terminal disease stages (Supplementary Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 2a). We chose PDX models for these experiments because species-specific differences in DNA sequence enable selective analysis of either tumour (human reads) or microenvironment (mouse reads) in individual ST spots (Extended Data Fig. 2b). This is particularly critical in GBM, given that transcriptional programmes are extensively shared between tumour and normal cells7,9. We selected a panel of ten non-mesenchymal-immune (non-mesimm) cell lines from patients, reflecting less advanced disease stages, before tumour cells undergo stable epigenetic remodelling to immune-evasive mesimm phenotypes25 (Supplementary Tables 1–3). An age-matched non-injected mouse brain was used as the control (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2a). We assigned ST spots to the WM or GM on the basis of high or low expression of abundant myelin genes (corresponding to >70th or ≤70th percentile of mean expression, respectively; Fig. 2a) and compared mouse transcriptomes between them using all spots in control samples and tumour-containing spots only in early and terminal PDXs (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4). This revealed that Gene Ontology (GO) terms linked to wound healing and ECM organization were strongly upregulated in the WM of early tumours, increasing further at terminal stages, whereas angiogenesis, adhesion, migration and immune response were upregulated more selectively in terminal tumours (cluster 5; Fig. 2b). By contrast, signatures of myelination were progressively downregulated over time, consistent with our previous findings9 (cluster 2; Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4). Signatures of neuronal activity were upregulated in both normal and tumour GM, as expected from the higher synaptic density in this region (clusters 3 and 4; Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4). This suggests that developing tumours may induce WM injury, which begins at early disease stages and continues throughout tumorigenesis.

a, Identification of myelinated regions. Top, H&E images of normal mouse brain (control) and the PDX model GCGR-L5 at the early (GCGR L5 early) and terminal (GCGR L5 terminal) stages. Bottom, as described for the top but overlayed with labels for high (green) and low (white) myelin marker genes expressing spots derived from ST data (Methods). Scale bars, 1 mm. b, Heat map of five k-mean clusters of log2-transformed fold changes (log2[FC]) from mouse genes significantly regulated between WM and GM in control, early and terminal PDX tumour ST spots (Methods). Selected terms enriched in cluster five are shown on the right. c, Gene set enrichment analysis in WM ST spots from control brain, or early and terminal PDX tumours. Normalized enrichment scores (NESs) of significantly enriched GO terms are shown (adjusted P < 0.1). d, Gene set enrichment analysis as in c, for cell type markers from ref. 51. The median of enrichment values across PDX models is shown. Astro, astrocytes; DC, dendritic cells; EC, endothelial cells; oligo, oligodendrocytes. e, The proportion of myelin high/low spots in bins of increasing tumour density (top). Middle, the proportion of spots assigned to anatomic brain regions in bins of increasing tumour density. Bottom, the average gene expression of functional categories in spots in bins of increasing density. f, The proportion of different cell types in bins of increasing tumour density derived by deconvolution using published scRNA-seq datasets (Methods). g, Reanalysis of ST data from ref. 26. Top, the proportion of spots assigned to histological regions in bins of increasing tumour density. Bottom, the averaged gene expression of different functional categories in bins of increasing tumour density.

We next investigated how these processes evolve by examining gene expression changes that accompany progression using two complementary approaches. First, we analysed mouse reads in the WM over time by comparing control brains with early and terminal tumours. Second, we used tumour density as a proxy for progression in terminal tumours. For this latter approach, we used the fraction of human (tumour) over the sum of mouse (microenvironment) and human (tumour) unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts per ST spot to give a tumour density ratio. This enabled us to selectively measure density of the tumour cells, independent of basal differences in densities of normal cells across mouse brain regions (Extended Data Fig. 2c–f). Indeed, this method showed increased sensitivity over nuclear density measurements extracted from haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images in regions of low tumour density (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f). Gene set enrichment (Fig. 2c–e) and deconvolution analysis (Fig. 2f) were performed to assess the processes and normal brain cells that are associated with progression (Extended Data Fig. 2g–o and Supplementary Table 5). Both approaches revealed that signatures linked to tissue injury, inflammation and repair correlated strongly with tumour progression. Notably, these signatures peaked in myelinhigh ST spots and in highly myelinated anatomical brain regions (corpus callosum; Fig. 2e, Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2p) in the density analysis, consistent with progression occurring preferentially in the WM. Tumour progression also correlated with an early and progressive decrease in neurons (Fig. 2d,f), followed by a decrease in cells of the oligodendrocyte lineage in terminal tumours (Fig. 2d), indicative of demyelination9 (Fig. 2b). It also correlated with an increase in astrocytes and microglia in early lesions, and an increase in myeloid and endothelial cells in terminal lesions (the latter probably reflective of angiogenesis; Fig. 2c,e). Notably, signatures linked to axonal injury (including neuron projection regeneration, response to axon injury and negative regulation of neuron projection development) were among the most consistently upregulated as a function of time or density (Fig. 2c,e, Extended Data Fig. 2h and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). Axonal degeneration is an early response to traumatic brain injury and a key driver of the ensuing inflammation and repair responses, suggesting that it might also have a role in initiating the inflammatory programmes that we identified in the axon-rich, WM-dense regions of the tumour3. Importantly, these findings were mirrored in two independent spatial datasets of human patient GBM tissue26,27, in which signatures of healthy axons decreased, and axonal injury signatures increased as a function of tumour cell density (Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 2q and Supplementary Table 6). Moreover, we used these published human datasets to explore a potential correlation between axonal injury programmes and WM regions in patients. To this end, we derived a human myelin signature using ST data from a previous study of normal brain tissue that had been annotated to WM or GM26 (Supplementary Table 7) and used it to determine myelin content per spot across regions of increasing tumour densities. This showed significant enrichment in the densest tumour regions, confirming human disease relevance (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 2q). Together, these results suggest that axons within WM-rich regions might be particularly vulnerable to tumour-induced damage and undergo degeneration even at low tumour cell densities. They also raise the possibility that axonal injury might be a key driver of GBM progression.

Axonal injury is an early event

To begin to test this hypothesis, we examined axonal degeneration over disease progression and as a function of tumour cell number in the context of tumour development from endogenous NSCs. We induced npp tumours in Thy1 YFP-16 reporter mice (hereafter Thy1-YFP), in which a subset of neurons are labelled with YFP allowing detailed histological analysis of axons28, and measured the YFP intensity as a readout of axonal integrity in the tumour ipsilateral striatal region, which contains the tumour bulk in most terminal lesions (Fig. 1a). We found that YFP fluorescence correlated inversely with increasing numbers of tumour cells (Extended Data Fig. 3a) and was first detectable at intermediate disease stages, peaking at late stages, with no further decrease in terminal tumours (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 3a), indicating that axonal degeneration coincides with the transition from latent to advanced disease (Fig. 1a–c). To further assess early tumour–axon interactions, we next measured YFP fluorescence in individual WM bundles of the tumour-involved striatum in npp Thy1-YFP tumours at the intermediate stage and correlated it to tumour density. We again found a significant negative correlation, with loss of axons already detectable in areas of low tumour infiltration (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). A similar response was detected in wild-type (WT) npp tumours by immunostaining for the axonal marker neurofilament, confirming specificity (Extended Data Fig. 3d,e). Furthermore, correlative light and electron microscopy analysis of sparsely tumour-infiltrated WM of intermediate npp tumours showed extensive axonal damage, including hallmarks of degeneration (axonal swelling, vacuolization, organelle accumulation and presence of condensed/dark axoplasm). However, there was no overt demyelination, with both intact and pathological tumour-involved axons displaying normal g-ratios (Fig. 3c–e and Extended Data Fig. 3f,g). Furthermore, intermediate npp tumour-bearing brains were negative for markers of proteinopathies or ischaemia (Extended Data Fig. 3h–k). This indicates that degeneration is caused by direct injury to the axons, rather than being a secondary event3. Consistent with this idea, super-resolution confocal imaging of npp tumours in Thy1-YFP mice revealed that tumour-involved WM bundles frequently contained axons with hallmarks of physical injury, including mitochondria-filled varicosities, blebbing and kinks3,29 (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Video 1). These were almost exclusively found immediately adjacent to tumour cells or their processes and were absent in contralateral WM (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, tumour-infiltrated WM tracts were also significantly stiffer and displayed elevated mechanosignalling relative to contralateral tumour-free WM regions (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 3l). Together, these data indicate that compression and mechanical stress caused by infiltrating tumour cells contribute to axonal loss in early tumours.

a,b, Fluorescence images of the contralateral (contra) or tumour-involved striatum (a) and quantification of the YFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in striatal WM (b) of Thy1-YFP mice bearing early, intermediate, late and terminal npp tumours. The arrowheads indicate high-infiltrated (yellow, Thy1-YFP loss) and low-infiltrated (white, Thy1-YFP present) WM. For a, scale bars, 100 μm. Data are mean ± s.d. normalized to contralateral YFP MFI. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. n = 4 (early, intermediate and late) and n = 3 (terminal) mice. c, Electron micrographs of tumour-involved and contralateral striatal WM of WT and Sarm1−/− mice bearing intermediate npp tumours. The yellow arrows indicate degenerating axons. Scale bars, 2.5 μm. n = 4 (WT) and n = 4 (Sarm1−/−) mice. d, Quantification of degenerating neurons in tumour-involved striatal WM in mice from c. Each dot represents a bundle. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 4 (WT) and n = 4 (Sarm1−/−) mice. P < 0.0001 for all comparisons. e, The g-ratios of tumour-involved (red dots) or contralateral (grey dots) striatal WM of mice from c. Each dot represents a WM bundle. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 4 (WT) and n = 4 (Sarm1−/−) mice. f, Super-resolution images of npp tumour-bearing brains stained for mitochondrial marker TOMM20 (grey), tdTomato+ tumour cells (red) and axons (green). The yellow arrowheads indicate a mitochondria-laden varicosity, and the white arrowhead indicates a kinked axon. The side panels are orthogonal views indicating direct tumour cell–axonal contact (open and black arrowheads). Scale bars, 10 μm. n = 5 mice. g, The percentage of varicosities within 5 μm of a tumour cell body, cell process or >5 μm away from a tumour cell (no tumour cell). h, Atomic-force microscopy measurements of tissue stiffness (kPa) in tumour-involved (tumour) or contralateral WM of Thy1-YFP npp tumour mice (n = 5). Each spot represents force per indentation. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided Mann–Whitney U-tests. P = 0.0108.

Tumour-induced axonal injury was also accompanied by a progressive increase in neuroinflammation. Reactive astrocytes first increased sharply during the early disease stage, with a further increase during the late stage, plateauing in terminal tumours. By contrast, activated microglia increased more gradually and continuously over the entire disease course (Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). When examining the WM within intermediate tumours at the cusp of progression, we observed a similar pattern, whereby reactive astrocytes increased as a function of tumour cell density (Extended Data Fig. 4d,e), forming glial scar-like structures around and within each tumour-involved bundle. Microglial activation also increased proportionally to tumour density, although to a lesser extent, and was confined to myelinated fibres (Extended Data Fig. 4f,g). Time-course analysis of tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) and lymphocytes using flow cytometry further indicated that early npp tumours largely lacked infiltrating immune populations, which instead became detectable at the intermediate and late stages and increased further in terminal tumours (Fig. 5j,l, Extended Data Fig. 4h–l and Supplementary Data 1). Consistent with the ST results (Fig. 2d,f), a similar pattern of early neuroinflammation largely mediated by resident glia was also observed in PDX models by time-course immunofluorescence analysis (Extended Data Fig. 4m,n). Together, these data suggest that astrocytes and microglia may have an important early role in driving glioma progression, consistent with recent reports24. Thus, axonal injury is an early event in gliomagenesis, which is triggered by neural progenitor cells that, after acquisition of mutations, are rerouted to the WM.

Axonal degeneration drives progression

Axonal injury typically results in the loss of the distal portion of the axon, which impairs neuronal function and can also lead to the death of the entire neuron3,30. The primary pathway underpinning axonal degeneration downstream of mechanical injury is WD3,4, an active programme of anterograde axonal degeneration mediated by the executioner sterile alpha and TIR-motif-containing 1 (SARM1) protein31,32. Genetic inactivation of Sarm1 suppresses WD and preserves neuronal integrity and aspects of function for extended time periods after injury33,34. Consistently, pharmacological inhibitors of SARM1 are being actively developed for the treatment of a range of neurodegenerative diseases35,36,37.

We therefore examined whether WD might also be responsible for the axonal loss observed in early tumours. npp tumours were induced in Sarm1−/− mice and the axonal integrity was examined in intermediate tumours, as described above. This showed robust neuroprotection with substantially reduced axonal loss in tumour-involved WM (Fig. 3c–e and Extended Data Fig. 3d–f), indicating that WD is the major mediator of axonal degeneration in early gliomagenesis.

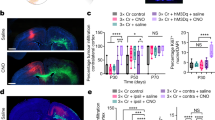

We next examined whether axonal injury in WM-dense regions has a causative role in tumour progression and, if so, whether this depends on WD and could be reversed by SARM1 inactivation. To this end, we used genetic perturbation of the pathway35,37 by generating npp tumours in WT or congenic Sarm1−/− mice and performing functional studies38. The mice were subjected to axonal transection injury, a well-established experimental paradigm for induction of WD, and the impact and timing of WD on tumour progression was assessed. Corpus callosum axons in the tumour ipsilateral hemisphere were surgically severed at the early, intermediate and late disease stages and analysis was performed 2 weeks later using immunohistochemistry (Fig. 4a). Age-matched sham-operated npp tumours of both genotypes were used as controls. We found that axonal transection injury increases tumour cell proliferation in both early and intermediate npp tumours in WT mice but not in Sarm1−/− mice, in which axonal degeneration was suppressed, and proliferation remained at the baseline sham levels (Fig. 4b,c and Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Notably, proliferation was not increased at the wound site itself in WT samples but, rather, across the main tumour mass, including GM regions but excluding distal infiltrative areas such as the contralateral hemisphere and septum (Fig. 4b,c and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). These effects are consistent with axonal degeneration, which occurs distal to the injury site, playing a key role in promoting tumour progression. Consistently, astrocyte reactivity and microglial activation also increased throughout the main tumour mass in WT npp tumours, although the former was more pronounced than the latter outside the injury site (Fig. 4d–f and Extended Data Fig. 5d–f); in npp tumours generated in Sarm1−/− mice at both timepoints, injury-induced inflammation was significantly reduced compared with the WT at the site of injury and was fully abolished in the rest of the tumour (Fig. 4d–f and Extended Data Fig. 5d–f). Importantly, these effects were not due to Sarm1-independent strain-specific phenotypes (mixed 129/C57BL6 background)39,40 or non-neuronal roles of Sarm1 (refs. 41,42) because a similar rescue of injury-induced progression was observed using an AAV-mediated gene therapy approach to inactivate Sarm1 specifically in neurons and in a pure C57BL6 background43 (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Indeed, intraventricular administration of AAVs carrying dominant-negative Sarm1 constructs driven by the human Synapsin promoter (AAV8-Syn-SARM1-CDN-eGFP) at the time of tumour induction resulted in axonal protection and reversed effects of transection injury at the intermediate disease stage, relative to AAV8-Syn-EGFP-injected controls (Extended Data Fig. 6a–f).

a, Schematic of the experimental outline. w, weeks. b, Representative images of WT npp tumours subjected to sham treatment or injury at the intermediate tumour stage. tdTomato (red), EdU (grey) and DAPI (blue) are visualized. Scale bars, 1 mm. n = 7 mice per group. c, Quantification of the percentage of EdU+tdTomato+ tumour cells in WT and Sarm1−/− npp tumours excluding the injury site (excl. inj. site) over the time course shown in a. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using multiple two-sided unpaired t-tests, with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. n = 6 (WT sham), n = 6 (WT injury), n = 6 (Sarm1−/− sham) and n = 7 (Sarm1−/− injury) at 4.5 weeks; n = 7 (WT sham), n = 7 (WT injury), n = 7 (Sarm1−/− sham) and n = 6 (Sarm1−/− injury) at 8.5 weeks; n = 7 (WT sham), n = 6 (WT injury), n = 7 (Sarm1−/− sham) and n = 6 (Sarm1−/− injury) mice at 12.5 weeks. d, Immunofluorescence images of tdTomato (red), GFAP (turquoise), CD68 (yellow) and IBA1 (magenta) staining in sham- or injury-group intermediate WT npp tumours. The dotted lines demarcate the corpus callosum (cc). str, striatum. Scale bars, 200 μm. n = 6 mice per group. e,f, Time-course analysis of the GFAP area (e) and CD68 intensity (IntDen; f) within WT and Sarm1−/− npp tumours excluding the injury site. The fold change is relative to corresponding sham-treated tumour mice at each timepoint. Data are mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using multiple two-sided unpaired t-tests with no adjustment for multiple comparisons comparing injury to sham at each time point and per genotype. n = 6 (WT sham), n = 6 (WT injury), n = 6 (Sarm1−/− sham) and n = 9 (Sarm1−/− injury) at 4.5 weeks; n = 7 (WT sham), n = 6 and 8 (WT injury), n = 8 and 7 (Sarm1−/− sham) and n = 8 (Sarm1−/− injury) at 8.5 weeks; n = 7 (WT sham), n = 8 (WT injury), n = 5 (Sarm1−/− sham) and n = 6 and 7 (Sarm1−/− injury) mice at 12.5 weeks. g, Kaplan–Meier curves of npp tumour-bearing WT mice subjected to sham (WT sham) or injury (WT injury) at the intermediate disease stage. Statistical analysis was performed using log-rank tests. n = 15 mice for both groups. Median survival: 110 days (WT sham) and 92 days (WT injury) after electroporation.

By contrast, we observed no significant changes in proliferation or neuroinflammation relative to the sham controls in either genotype when transection injury was performed in mice with late-stage tumours (Fig. 4a,c,e,f and Extended Data Fig. 5b–f). Thus, experimental injury accelerates progression of latent (early and intermediate stage) WT lesions through WD but has little impact on advanced tumours (late stage), which have already undergone progression pretransection within the tumour bulk and display pronounced proliferation, neuroinflammation and axonal degeneration at the baseline (Figs. 1c and 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Consistent with this, intratumoural administration of AAV8-Syn-SARM1-CDN-eGFP (but not AAV8-Syn-eGFP) suppressed tumour cell proliferation at the intermediate tumour stage but not at the late tumour stage (Extended Data Fig. 6g–k).

To assess the impact of axonal transection injury during the latent stage on long-term tumorigenesis, we next performed survival studies. We found that corpus callosum transection in mice bearing intermediate npp tumours significantly accelerated tumorigenesis and decreased survival relative to the sham controls (Fig. 4g). Together, these findings indicate that axonal injury and the ensuing WD increase neuroinflammation and promote glioma progression to advanced disease, a process that is rescued by inactivation of SARM1.

SARM1 inhibition delays progression

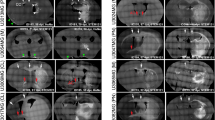

Our results so far suggest that inhibition of SARM1 may represent a potential therapeutic target for suppressing disease progression. To test this more directly, we generated npp tumours in WT and Sarm1−/− mice and used H&E staining and immunofluorescence analysis to examine their phenotypes at the terminal disease stage. Tumours generated in both genotypes replicated histology consistent with IDH WT diffuse astrocytic glioma as previously reported for the npp model18,19,20,21,22. However, aggressive neuropathological features were seen more commonly in WT mice than in Sarm1−/− mice19 (Extended Data Fig. 8a and Supplementary Data 2), indicative of terminal tumours being less advanced in the absence of WD. Notably, in Sarm1−/− mice, the tumours also appeared overall more diffuse compared with the WT controls, as judged by smaller proportions of tumours forming a defined bulk, lower tumour density and increased tumour area on the basis of both fluorescence imaging and H&E assessment (Fig. 5a–d, Extended Data Fig. 8a and Supplementary Data 2).

a–c, Representative images of tdTomato+ terminal WT and Sarm1−/− npp tumours (a), quantification of the proportions of tumours with defined bulk (localized) or diffuse phenotype (diffuse) (b) and the tumour cell density in each genotype (c). For a, scale bars, 1 mm. Data are mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-tests. n = 10 (WT) and n = 9 (Sarm1−/−) mice. d, Quantification of the tdTomato+ area in WT and Sarm1−/− terminal tumours. Data are mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-tests. n = 10 (WT) and n = 6 (Sarm1−/−) mice. e, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of scRNA-seq data from terminal WT and Sarm1−/− npp tumours: neural progenitor-like (NPC-like), OPC-like, astrocyte-like (AC-like), MES-like and aNSC-like. f, As in e, but for microenvironmental cells: choroid plexus cells (CP), astrocytes, inflamed glia (infl. glia), OPCs, transient amplifying progenitors/neuroblasts (TAP/NB), aNSCs, ependymal cells (EpC), endothelial cells, pericytes, TAMs, monocytes (Mn) and T cells. g,h, The proportion of subpopulations between genotypes in tumour (g) and non-tumour (h) cell populations. The dashed line denotes equal proportions. Pearson’s χ2 test < 0.05 and relative difference > 10% were considered to be significant (indicated by the hash symbol (#)). i–m, Flow cytometry analysis of immune populations (CD45 (i), TAMs (j), microglia (k), macrophages (l) and lymphocytes (m)) in terminal WT and Sarm1−/− npp tumours. Data are mean ± s.d. Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-tests. n = 5 (WT) and n = 4 (Sarm1−/−) mice. n, Kaplan–Meier analysis of npp tumour-bearing WT (grey) and Sarm1−/− (turquoise) mice. Median survival: 125 (WT) and 148 (Sarm1−/−) days. Statistical analysis was performed using log-rank tests. n = 22 (WT) and n = 18 (Sarm1−/−) mice. o, Neuroscores of npp tumour-bearing WT (grey) and Sarm1−/− (turquoise) mice at the indicated timepoints. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. Data are mean ± s.d. n = 5 (WT) and n = 5 (Sarm1−/−) mice. p, As for n, but for Sarm1-WT (WT, grey) and Sarm1em1.1Tftc (turquoise) mice. Median survival: 120 (WT) and 152.5 (Sarm1em1.1Tftc) days. Black lines denote censored animals. Statistical analysis was performed using log-rank tests. n = 10 (WT) and n = 12 (Sarm1em1.1Tftc) mice. q, As described for o, but for Sarm1-WT (grey) and Sarm1em1.1Tftc (turquoise) mice. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparison correction. Data are mean ± s.d. Early: n = 8 (WT), n = 13 (Sarm1em1.1Tftc); advanced: n = 6 (WT) and n = 11 (Sarm1em1.1Tftc) mice.

This broader dissemination led us to speculate that WD might have a role in the tropism to WM tracts that we observed in early gliomagenesis (Fig. 1b). To test this hypothesis, we quantified the distribution of tumour cells in Sarm1−/− tumours at the intermediate stage, when WM tropism is maximal in the WT (Fig. 1b) and found a complete loss of WM bias in the absence of WD (Extended Data Fig. 7a). To examine how this may impact tumour growth and invasion patterns, we developed an agent-based mathematical model of gliomagenesis constrained by our experimental data (Extended Data Fig. 7b–g and Supplementary Methods). This revealed that, in WT tumours, WD contributes to retaining early tumour cells in the WM, ultimately leading to the formation of more cellularly dense and localized tumours at the terminal disease stage. By contrast, in the absence of WD, tumour cells exit the WM more readily and spread more widely to generate disseminated terminal lesions (Extended Data Fig. 7b–g). These data suggest that the more-diffuse phenotype of Sarm1−/− tumours is at least partially underpinned by impaired WD.

To understand the mechanisms involved, we carried out single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis. Transcriptomes from a total of 78,131 and 23,916 cells were analysed from terminal tumours in WT and Sarm1−/− mice, respectively (Supplementary Table 8). After preprocessing, filtering and downsampling, cells were clustered and cluster labels defined using published scRNA-seq datasets (Fig. 5e,f, Methods and Supplementary Table 9). Tumour cells were then identified and separated from normal cells of the microenvironment based on their gene expression profile, aneuploid state and expression of tdTomato (Fig. 5e,f, Methods and Supplementary Table 9). As we previously reported, WT npp tumours reflected canonical transcriptomic states from ref. 7, encompassing both neurodevelopmental-like (NPC-like, OPC-like and astrocyte-like cells) and mesenchymal/injured-like populations (MES-like cells), as well as an actively proliferating state resembling active NSCs (aNSC-like)7,19. The same states were also found in tumours in Sarm1−/− mice, but in different proportions, with a particularly marked increase in NPC-like cells and a reduction in MES-like cells (Fig. 5e,g). There was no change in the proportions of cycling cells (aNSC-like) at this terminal stage, which was confirmed by Ki-67 immunofluorescence analysis (Extended Data Fig. 8b,c). We also detected pronounced differences in the tumour microenvironment; tumours in WT mice contained relatively greater proportions of endothelial cells, pericytes and glial cells of mixed astrocytic and oligodendrocytic fate with markers of high interferon signalling (hereafter, inflamed glia; Fig. 5h). Furthermore, differential expression analysis between genotypes across normal cell populations suggested that WT endothelial cells and pericytes upregulated signatures of angiogenesis (for example, cell migration, adhesion, positive regulation of smooth muscle cell migration and angiogenesis; Supplementary Table 10). To probe this more directly, we compared the tumour vasculature between genotypes using immunofluorescence analysis and found increased vessel diameter and branching alongside a trend towards increased permeability in WT tumours, in the absence of changes in vascular density, coverage or length (Extended Data Fig. 8d–n). Although the overall proportions of TAMs were unchanged in the scRNA-seq dataset (and validation immunofluorescence analysis on terminal tumour tissue; Fig. 5h and Extended Data Fig. 8o,p), reclustering of this population alone indicated that cells more closely resembling anti-inflammatory macrophages of the tumour core were enriched in the WT relative to tumours in Sarm1−/− mice44,45 (Extended Data Fig. 9a–d). By contrast, TAMs in Sarm1−/− mice with tumours expressed higher levels of pro-inflammatory microglial markers characteristic of infiltrative tumour regions44,45 (Extended Data Fig. 9a–d). Immune profiling of late-stage tumours by flow cytometry confirmed this result, revealing that npp tumours in WT mice were overall more immune infiltrated, containing higher proportions of macrophages and T cells, whereas microglia dominated in tumours generated in Sarm1−/− mice (Fig. 5i–m and Supplementary Data 1). Furthermore, LIANA analysis revealed that increased heterotypic signalling occurred between tumour cells and their microenvironment in the WT, relative to in Sarm1−/− mice (Extended Data Fig. 9e–h). Together, these findings demonstrate that inhibition of the SARM1 pathway significantly slowed tumour progression to densely cellular, angiogenic and immune-suppressive lesions, as well as the accompanying transition of tumour cells to MES-like/injured states25,46; instead, it led to the development of more diffuse and less inflamed tumours that more closely mirrored normal neurodevelopmental lineages.

These results prompted us to examine whether Sarm1 loss might affect the course of the disease more broadly in two sets of complementary experiments. First, we compared tumour latencies in survival studies and found that Sarm1 deletion resulted in a significant extension of survival (Fig. 5n; median survival 18 weeks in WT and 21 weeks in Sarm1−/−). This was unlikely to solely result from the more diffuse nature of tumours in the Sarm1−/− background and therefore a reduction in potential bulk effects, because we found that survival did not significantly correlate with either tumour cell density or the presence of a defined bulk in our somatic models (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Second, given the prolonged preservation of axonal integrity that we observed in Sarm1−/− tumours (Fig. 3c,d), we assessed neurological function in mice with advanced tumours (corresponding to ≤2 weeks before death) using motor score testing (Fig. 5o). Notably, whereas severe deterioration of motor function was detected in tumour-bearing WT mice, motor function was maintained at near-normal level in Sarm1−/− mice, indicative of neuroprotection. These effects were again Sarm1 specific because induction of npp tumours in a second independent mouse model based on CRISPR–Cas9-mediated Sarm1 gene knockout39 also resulted in more-diffuse terminal tumours with extended survival and preservation of motor function relative to background-matched controls (Fig. 5p,q and Extended Data Fig. 10c,d).

We conclude that WD represents a key driver of gliomagenesis, which could be targeted through inhibition of SARM1 to suppress tumour progression and ameliorate disease course and its symptoms.

Discussion

The burgeoning field of cancer neuroscience has revealed that neuronal activity modulates many aspects of gliomagenesis, including proliferation, invasion and therapy resistance47. Our results identify a complementary, unanticipated role for neuron–cancer interactions: the promotion of GBM progression by injured axons. Thus, neurons profoundly impact GBM biology throughout their life-cycle, both in the intact, actively signalling state and after degeneration.

Although it is well established that neuronal death occurs at late disease stages, our finding that axonal degeneration begins even in sparse tumour regions was unexpected9,48. Our analyses suggest that this degeneration is at least partially due to physical and mechanical compression injury inflicted by tumour cells. However, several additional mechanisms, such as neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondrial disfunction, may also have a role and warrant further investigation3. Regardless of their exact contributions, we demonstrate that WD is a key effector mechanism of axonal death downstream of these insults.

This is of clinical importance as the finding that the enzymatic activity of SARM1 mediates WD has unlocked the possibility of pharmacologically targeting it to preserve neuronal function in a variety of neurodegenerative conditions4. Notably, although SARM1 is most highly expressed and predominantly functions in neurons, some low-level expression in astrocytes and macrophages has also been reported39,40,41,42. Although it remains to be determined whether non-neuronal roles may also exist in GBM, our gene therapy approach indicates that SARM1 drives progression primarily through WD itself. Furthermore, our results from two independent Sarm1−/− mouse lines, which mirror pharmacological blockade, indicate that its constitutive inactivation would be overall beneficial in GBM.

In summary, our study identifies a central mechanism underpinning the emerging role of injury programmes in GBM initiation and progression9,24,49,50. It provides a proof of principle that, by suppressing progression, targeting the injury microenvironment may lock tumours in a more-latent, less-aggressive stage and ameliorate the disease course. Owing to its unique protective effects on axons, targeting WD specifically might offer the added benefit of preserving neurological function, with important implications for the quality of life of patients with GBM.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the Animal Scientific Procedures Act, 1986 and approved by the UCL Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body (AWERB) in accordance with local ethical and care guidelines and the International guidelines of the Home Office (UK). Mice used in this study were WT C57BL/6NCrl (Charles River), congenic Sarm1tm1Aidi (strain 018069; Sarm1−/−)38 and Sarm+/+ littermates (both a gift of M. Coleman), CRISPR knockout Sarm1em1.1Tftc and Sarm1 WT39 and B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFP)16Jrs/J (Jax Laboratories, 003709)28. Genetically and aged matched animals were used as controls for Sarm1−/− experiments. NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/NCrCrl (NSG, Charles River) were used for generation of the PDX models through orthotopic injections of patient-derived GBM cell lines. Tissue from Apptm3.1Tcs (strain 5637817) and rTg4510 (strain 024854) mice (gifts from S. Hong and G. Schiavo) were used as positive controls for assessment of proteinopathies. Mice were group-housed (where possible) in individually ventilated cages and maintained under 12 h–12 h light–dark cycles at 20–24 °C, 40–60% humidity, with water and chow available ad libitum. Mice of both sexes were used and, where appropriate, all animal experiments were blinded.

Derivation and culture of cell lines

Cell lines were derived from the CRUK glioma cellular genetics resource (GCGR) with driver mutations shown in Supplementary Table 1 (G. Morrison et al., manuscript in preparation). GBM2 was derived independently as previously described52. Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Committee (Wales REC 6; reference 20/WA/0251), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the approving committee, the Declaration of Helsinki, the Human Tissue Authority and the General Data Protection Regulation. All patient lines were cultured adherently in serum-free GSC medium (N2 (1/200), B27 (1/100) (Life Technologies), 1 mg ml−1 laminin (Merck, L2020), 10 ng ml−1 EGF (Biotechne, NBP2, 35176), 10 ng ml−1 FGF-2 (Biotechne, NBP2, 35152), 1× MEM NEAA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12084947), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 31350010), 0.012% BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15260-037), 0.2 g l−1 glucose (Merck, G8769), 1,000 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (Merck, P0781). All of the cell lines were mycoplasma negative.

Generation of somatic and orthotopic PDX models

Somatic tumours were generated as previously reported19,20. In brief, plasmids described in Extended Data Fig. 1a were injected into the right ventricle of isoflurane-immobilized pups at postnatal day 2 using an Eppendorf Femtojet microinjector (Eppendorf, 5247000030) followed by electroporation (5 square pulses, 50 ms per pulse at 100 V, with 850 ms intervals). The EF1a-tdTomato-only plasmid (tdTom) was generated by SnaBI and PmeI digestion of npp plasmid to remove Nf1, Pten and Trp53 guide RNAs before religation. piggyBase (hGFAPMIN-SpCas9-T2A-PBase, 1 mg ml−1) and piggyBac vector U6-Nf1,Pten,Trp53-EF1a-tdTomato (npp, 0.564 mg ml−1) or EF1a-tdTomato (0.423 mg ml−1) were diluted in saline (0.9% NaCl) and mixed at a molar ratio of 1:1. Then, 0.1% fast green (Sigma-Aldrich, F7258) was added to the mix to visualize the injection. All experiments using somatic mouse models were performed on a mix of male and female mice. Whole litters of mice were injected with plasmids, regardless of sex.

To pharmacologically inhibit SARM1 protein selectively in neurons from npp tumour initiation, AAV8-Syn-SARM1-CDN-EGFP (a gift from J. Milbrandt, 0.745 × 1013 viral genomes (vg) per ml)43 was added to the piggyBase/npp piggyBac plasmid mix before intraventricular injection and electroporation, as described above. AAV8-Syn-GFP (Addgene, 50465-AAV8 0.745 × 1013 vg per ml) was used as a control. To investigate SARM1 function after tumour initiation, WT mice bearing tumours were injected with either 2.5 µl AAV8-Syn-SARM1-CDN-EGFP (1 × 1013 vg per ml) or AAV8-Syn-GFP (1 × 1013 vg per ml) at the intermediate or late disease stage. Male and female mice were randomized separately into GFP and SarmDN groups. In brief, mice were anaesthetized and mounted onto a stereotaxic frame. A small craniotomy was performed on the tumour ipsilateral right side of the skull 1.7 mm lateral to bregma and −0.5 mm anterior to bregma. Virus was injected through a 5 μl Hamilton syringe attached to a pump (Pump 11 Elite Nanomite, 70-4507, Harvard Apparatus) at a speed of 0.3 µl min−1 to a depth of 2.4 mm. The virus was injected continuously as the needle was introduced and removed. The wound was sutured and the mice were allowed to recover. Then, 4 weeks after injection, the mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of EdU (5 mg per kg) 2 h before brains were collected following transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) under terminal anaesthesia.

Orthotopic PDX models were generated as previously described in female NSG mice9. All tumour-bearing mice were monitored daily and euthanized at the required timepoints or at terminal stage, as defined by them reaching tumour-associated humane end points, which correlate with a lethal disease stage, specifically, any one or more of the following signs of general pain or distress (including seizures); greater or equal to 15% weight loss, hunched posture, piloerection, inactivity, ocular/nasal discharge, intermittent abnormal respiratory pattern or loss of body conditioning).

Injury induction in tumour-bearing mice

Brain injury experiments were carried out on tumour-bearing mice at 4.5, 8.5 and 12.5 weeks after electroporation with piggyBase/npp piggyBac plasmids. Male and female mice were randomized separately into sham and injury groups. Mice were anaesthetized and mounted onto a stereotaxic frame. A small craniotomy was performed on the tumour-ipsilateral right side of the skull 1.7 mm lateral to bregma and extending from 0 to 1.0 mm anterior of bregma. A 25 G needle with the bore facing to the right was introduced into the brain through the craniotomy to a depth of 2.5 mm. The needle was moved anterior and posterior three times across a 1.0 mm distance to sever the axons of the corpus callosum. Sham mice underwent the same analgesia and anaesthesia protocol but were not mounted onto the stereotaxic frame. Then, 2 weeks after injury, the mice were given an intraperitoneal injection of EdU (5 mg per kg) 2 h before brains were collected following transcardial perfusion with 4% PFA under terminal anaesthesia. Brains were fixed overnight in 4% PFA at 4 °C, transferred to PBS before vibratome sectioning (50-μm sections) and stored in cryobuffer (ethylene glcol:glycerol:PBS 1:1:2). Survival studies were carried out on tumour-bearing WT mice, which underwent brain injury or sham surgery at 8.5 weeks after electroporation with piggyBase/npp piggyBac plasmid mix as described above. Mice were euthanized when they showed any of the humane endpoints described above.

Behavioural assessment

Behavioural neuroscores were determined as follows. A ledge test was carried out observing mice walking along the edge of a cage and lowering themselves into the cage and scored as follows: 0, confident walk and good landing; 1, trips and wobbles while walking; 2, trips and wobbles, slips from ledge but recovers; 3, unable to walk along ledge. A hindlimb clasping test was carried out and scored as follows: 0, hindlimbs consistently pointing outward away from abdomen; 1, hindlimbs pulled in slightly towards body for more than 50% of the time; 2, hindlimbs pointed downwards towards abdomen for more than 50% of the time; 3, hindlimbs entirely retracted and touching the abdomen for more than 50% of the time. A gait test was carried out and scored as follows: 0, mouse moves normally; 1, slight tremor observed, slightly raised pelvis or slight waddle; 2, severe tremor, raised pelvis or pronounced waddle; 3, movements disjointed, stuttering with raised pelvis and severe waddle. A Kyphosis test was carried out and scored as follows: 0, easily able to straighten its spine as it walks; 1, mild kyphosis (curvature of the spine) but mostly able to straighten itself as it walks; 2, unable to straighten spine completely and maintains mild but persistent kyphosis; 3, maintains pronounced kyphosis as it walks or while it sits. Scores from each test were combined to give an overall neuroscore between 0 and 12. Mice were tested at 8 weeks for early disease stages and at 14 weeks and 16 weeks for advanced disease stages for WT and Sarm1−/− mice, respectively. At the late disease stage, mice were tested three times over three different days and neuroscores were averaged to account for the higher variability at advanced disease stage.

Visium ST data generation

For ST, brains from NSG mice with early or terminal PDX tumours or control NSG mice (15 weeks of age) were dissected, snap-frozen in methylbutane cooled to −20 °C in a bath of dry ice and liquid nitrogen, stored at −80 °C before embedding in OCT and sectioning at 10 μm on the Leica cryostat at −13 °C. From each brain, two 10 μm sections were collected at approximately 200 μm intervals from anterior to posterior in the striatal region onto 10x Visium Spatial Gene Expression slide (1000184, 10x Genomics). Slides were processed according to manufacturer’s instructions (10x Genomics) using a tissue permeabilization time of 36 min. RNA libraries were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (library preparation kit 10x Genomics) and sequenced on the NovaSeq system with paired-end 150 bp reads.

Visium ST data analysis

Read selection and mapping

Reads from PDX experiments were aligned to reference genomes GRCh38-2020-A (human) and mm10-2020-A (mouse) using 10x Genomics Space Ranger v.2.0.1 (Supplementary Table 2). To assign reads to either species confidently, reads were mapped three times: (1) to the human genome; (2) to the mouse genome; (3) to a combination of both genomes. Reads mapping consistently to a single species using this procedure were selected and remapped to the combined genome as in point (3) to form the final dataset (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Reads from normal NSG mouse brains were filtered as above and remapped to the mouse genome for downstream analysis.

Selection of tumour-free spots

To define tumour-free Visium spots, we remapped reads from normal mouse brain to the combined genome and calculated for each spot the ratio between UMI counts assigned confidently to human or mouse. We reasoned that, as only mouse reads were present in the dataset, the distribution of these ratios was representing the background distribution (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d). On the basis of these data, we defined tumour-free spots as having a human to mouse ratio <2−4 (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d).

Data filtering and normalization

Spots with total UMI counts below 256 were discarded. Genes with non-zero counts in at least 1% of spots were retained for further analysis. Across tumour spots in each PDX model, human and mouse UMI counts were normalized separately using the posterior mean derived from the bayNorm package with parameter ‘mean_version=TRUE’53. bayNorm normalized counts were used in Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 2g,h–o. For annotation of anatomical regions (Extended Data Fig. 2p), data were normalized using the sctransform package54.

Quantification of tumour density

Tumour density in individual Visium spots was measured using two different methods (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f and Supplementary Table 3): (1) using Visium spots positions on H&E images (Extended Data Fig. 2e (bottom)). For each spot, the area occupied by nuclei was calculated using Squidpy55. The spot area occupied by nuclei divided by the total spot area was then used as a measure of tumour density. (2) Based on sequencing data. For each spot, the total UMI counts from human transcripts divided by the total UMI counts from both species was used as a measure of tumour density.

Annotation of anatomical regions

To generate a reference dataset, normal mouse brain data were first clustered using the BayesSpace package56. Spatial clusters were then compared with annotation from the Allen Mouse Brain Atlas57 database and manually assigned labels (from specific anatomical regions). This reference dataset was used to annotate PDX data where brain morphology is partially disrupted by tumour cells and difficult to annotate manually. Data from each PDX was integrated with normal mouse brain data using the harmony package58. PDX anatomical regions were then predicted using random forest within the Harmony space59. Specifically, each dataset (PDX and normal mouse brain) was normalized using the sctransform package54. PDX and normal mouse brain data were then merged after selection of common features using the SelectIntegrationFeatures function from Seurat60, using RunHarmony in the Harmony package58. This was done in principal component analysis (PCA) space generated using the RunPCA function from Seurat60. For annotation, a random forest model was trained using annotated anatomic regions from normal mouse brain and its low-dimension space data from Harmony and used to predict anatomic regions in PDX data (Fig. 2e, Extended Data Fig. 2p and Supplementary Table 3).

Annotation of myelin high/low spots

We selected five myelination-related genes as markers of myelinated regions (Mbp, Cnp, Plp1, Mog and Mag)9 (Fig. 2a). Visium spots with mean total normalized counts for the five genes over the 70th percentile of their mean expression across spots in each section were labelled as myelinhigh.

Generation of pseudospots

The number of UMIs of human and mouse genes in a spot changes with tumour cell density (by definition) (Extended Data Fig. 2h–o). To control for spurious gene enrichments resulting from variations in number of a species UMI per spots (sequencing depth), a control dataset of randomized pseudospots was constructed as follows. In each PDX cell line, among spots with human/mouse ratio of total UMI counts between 0.5 to 1.5, the spot with the largest number of genes with non-zero UMI counts was selected for further downsampling and creation of pseudospots. For mouse genes, binomial downsampling53 was used on the spot UMI counts to generate pseudospots with UMI numbers corresponding to tumour densities ranging from 0.05 to 0.95. In total, 500 pseudospots were created in each PDX. As the pseudospots were created from a single spot, gene signatures are expected to show no correlation with tumour density.

Deconvolution of Visium data

To estimate cell type composition in each spot, Visium data were deconvoluted using the cell2location package61 and normal mouse brain scRNA-seq data from the Ximerakis study as reference 51 (Fig. 2d).

Normalization of cell type distributions across density bins

Tumour density was first discretized into 20 bins ranging from 0 to 1 with step size 0.05. Then, let xgcij denote the estimated number of cell types g in the ith spot of cth cell line, which lies in jth density bin, where j ∈ {1, …, 20}. In each spot, the proportion of cell types was calculated as \({p}_{gcij}={x}_{gcij}/{\,\sum }_{g}{\,x}_{gcij}\). Values in each bin were then summarized by taking the average across spots: \({\bar{x}}_{gcj}={\sum }_{i}{p}_{gcij}/{n}_{ci}\), where nci stands for the number of spots from the cth cell line in the jth bin. For each cell type in each bin, the average was taken across cell lines, and z-score-normalized across bins (the values are shown in Fig. 2f).

Gene signatures selection and enrichment analysis

The AUCell package was used to calculate gene signatures enrichment (area under the curve (AUC value))62. GO term gene lists were retrieved from the msigdbr database using the R package msigdbr63. Mouse GO terms with at least 50 genes were retained for further analysis (n = 1,980). Gene signatures used in Fig. 2b,c,e,g, are described in Supplementary Tables 4 and 6.

Human WM markers were derived using the ST dataset published previously26. In brief, spots from the cortex of samples 242_C, 248_C, 259_C, 265_C, 313_C and 334_C with log2-transformed total UMI counts between 8 and 14 were selected. Spots were combined and total counts were normalized. WM markers were defined as genes significantly that were upregulated in spots annotated as ‘white matter’ compared with spots annotated as ‘vascular’, ‘hyper cellular’, ‘grey matter’, ‘infiltrative’ and ‘necrotic edge’ (adjusted PWilcoxon < 0.01 and AUC value above 0.99 quantile of fitted Gaussian distribution on the AUC values reported from the wilcoxauc function of the R package presto)64.

These human WM markers and gene lists described in Supplementary Table 7 were used in Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 2q.

Comparison of gene expression in WM and GM

Data from sections 1 and 2 of all ST experiments were divided into three groups: (1) normal healthy brain (NSG); (2) early tumours; and (3) terminal tumours (Fig. 2b). Count data from either WM or GM spots within each group were summed up to create pseudobulk RNA-seq datasets. Differentially expressed genes between WM and GM were then identified using DESeq2 (ref. 65) within each group separately.

Differentially expressed genes were selected using Padj < 0.01 and absolute log2-transformed fold change of >0.5 as cut-offs. Differentially expressed genes from the three groups were pooled and k-means clustering was performed on the log2-transformed fold change values with number of clusters set to 6. We applied the enricher function from the R package clusterProfiler66 on each cluster for enrichment analysis. Six GO terms enriched in cluster 2 were selected and the mean log2-transformed fold change of genes associated with each one of them is shown on Fig. 2b (right) (Supplementary Table 4 (geneID column)).

Comparison of WM spots between groups

The WM pseudobulk data from Fig. 2b for each group were used individually as input for DESeq2 (ref. 65) using the other two groups as a reference (Fig. 2c). The R package fgsea67 was used for GO term enrichment analysis on the log2-transformed fold change values from each group. NESs of selected significant GO terms (Padj < 0.1) are shown on Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 6.

Normalization of gene signature across tumour density bins

Tumour density was first discretized into 20 bins ranging from 0 to 1 with step size 0.05 (Fig. 2e,g and Extended Data Fig. 2). Then, for each gene signature (g), let xgcij denote the AUC value of that gene signature from the ith spot of the cth cell line in the jth bin, where j ∈ {1, …, 20}. The average AUC value of the spots in the jth bin: \({\bar{x}}_{gcj}={\sum }_{i}{x}_{gcij}/{n}_{cj}\), where ncj stands for the number of spots from the cth cell line in the jth bin. Then the mean across cell lines was calculated and as \({\bar{x}}_{gj}={\sum }_{c}{\bar{x}}_{gcj}/{n}_{c}\), where nc stands for the number of cell lines used. Finally, \({\bar{x}}_{gj}\) was z-score normalized across 20 bins such that \({z}_{gj}=\frac{{\bar{x}}_{gj}-{\mu }_{gj}}{{\sigma }_{gj}}\), where μgj and σgj stand for the mean and s.d. of \({\bar{x}}_{gj}\) across 20 bins respectively.

Comprehensive evaluation of gene signatures expression trends as a function of tumour density

A Mann–Kendall trend test (R function mk.test from the R package trend)68,69, which was originally developed for testing monotonic trend in time-series data, was used to explore expression trends of gene signatures as a function of binned tumour densities. Let \({x}_{gcj}={{\rm{median}}}_{i}({x}_{gcij})\) denotes the median of AUC value of gene signature (g) of cth cell line in the jth bin (xgcij as defined above). mk.test with alternative=two.sided was applied to xgc across 20 bins (bins with missing values due to a limited number of spots were not considered) for each cell line and pseudospots. mk.test reports two statistics, S and pval. Positive/negative S values stand for increasing/decreasing trend of gene signature as a function of binned tumour densities (\(S=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k=1}^{n-1}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j=k+1}^{n}{\rm{sgn}}({x}_{gcj}-{x}_{gck})\) where sgn is the sign function and n = 20 is the number of bins), while pval indicates whether that trend is significant or not68,69. GO terms with at least one PDX cell line with pval < 0.1 were kept for k-means clustering on S values (Extended Data Fig. 2g and Supplementary Table 5).

Reanalysis of published spatial datasets from human glioblastoma

For the ref. 26 dataset, data were downloaded from https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.h70rxwdmj. Tumour densities were determined from H&E images using the image based approach used on Extended Data Fig. 2e,f (see above).

For the ref. 27 dataset, Cosmx data were downloaded from https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/wc8tmdmsxm/3. Following the preprocessing steps reported previously27, cells with fewer than 20 total transcripts, fewer than 20 genes detected or more than 3 negative control probes were removed. Filtered data were log-normalized and scaled using Seurat. Clustering of cells was done using PCA space for identifying tumour cells based on marker genes from refs. 7,27. For each cell (including tumour and non-tumour cells), we calculated the proportion of tumour cells present around it within a 55 µm diameter circular area (corresponding to the spot size on the Visium platform). These tumour densities were then discretized into 20 bins. Bins with upper bounds 0.05, 0.8, 0.85, 0.9, 0.95 and 1 were discarded as the number of cells per bin was low (<300).

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Animals were perfused (4% PFA in PBS; Merck P6148) under terminal anaesthesia, brains were collected, post-fixed overnight at 4 °C in PFA (4%) before transferring to PBS. Vibratome sections (50 µm) were prepared and stored in cryopreservative (glycerol:ethylene glycol; PBS 1:1:2) before immunohistochemistry. For staining, floating sections were permeabilized overnight (1% Triton X-100, 10% serum in PBS) at 4 °C, incubated in primary antibodies overnight (1% Triton X-100, 10% serum in PBS) at 4 °C and for 3 h in secondary antibody (0.5% Triton X-100, 10% serum in PBS) containing DAPI counterstain (Insight Biotechnology, sc3598). The sections were mounted with antifade mounting solution (Prolong gold antifade mountant, Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36934) before imaging on a 3i confocal spinning disk (3i SlideBook Version 2023). For imaging of axonal damage, brain tissue from Thy1-YFP mice were imaged using the Airyscan function of the LSM 880 confocal microscope (Zeiss Zen Black v.2.1).

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-Ki-67 (1:250; Abcam, ab16667), goat anti-GFAP (1:1,000, Abcam, ab53554), rat anti-CD68 (1:500, Abcam, ab53444), rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:1,000, Wako, 019-19741, L0159), mouse anti-neurofilament H (1:1,000, Enzo, ENZ-ABS219-0100), mouse anti-MBP (1:1,000, Covance, SMI-99), mouse anti-SMI32 (1:1,000, Enzo, ENZ-ABS219-0010) chicken anti-GFP (1:1,000, Abcam, ab13970), rabbit anti-RFP (1:1,000, ABIN129578), rabbit anti-pMLC2 (1:100, Cell Signalling, 3671), mouse anti-phospho-Tau S202/T205 (1:500, a gift from G. Schiavo), mouse anti-TDP-43 (1:500, Abcam, ab104223), rabbit anti-TOMM20 (1:1,000, ab186735) and mouse anti-amyloid-β (1:100, Merk, MAB348A4), rabbit anti-laminin (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, L9393), goat anti-CD31 (1:100, BioTechne, AF3628), rat anti-PDGFRB (1:200, gift from I. Kim), donkey anti-mouse IgG 488 (1:500, Thermo Fisher Scientific, A21202). For detection of EdU, the sections were stained using the Click-it EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen, C10340) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Hypoxic regions were identified by intraperitoneal injection of pimonizadole (60 mg per kg; Hypoxyprobe Omnit Kit HP3-1000Kit) 90 min before brains were collected after transcardial perfusion with 4% PFA under terminal anaesthesia. Brains were fixed in 4% PFA overnight and sectioned (40 μm) on a vibratome. The sections were permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X-100, 10% donkey serum in PBS overnight before incubation in primary antibody (1:1,000 rabbit anti-pimonidazole adducts) and detection with donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (1:1,000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-31573) and counterstained with DAPI.

Computational image analysis

Analysis of tumour cell localization and proliferation was performed in Imaris 10.1.0 on single z plane images from a 3i spinning-disk microscope. Spot segmentation was first performed on tdTomato/GFP channel, before being filtered for intensity median or centre on DAPI to segment tumour cells. Tumour cells were then classified as EdU/Ki-67+/−. For quantitative assessment within WM and GM (Fig. 1b,c and Extended Data Fig. 1b,g), we analysed the striatum because it is an anatomically well-defined brain region that is infiltrated by early tumour cells and contains both GM and WM in discrete bundles. Surfaces were manually drawn for the SVZ, haemorrhagic/necrotic regions, striatum and injury sites, and tumour cells within SVZ and haemorrhagic/necrotic regions were filtered out. WM bundle surfaces were generated using the machine learning function. The percentage of WM area (Extended Data Fig. 1b) was calculated by dividing the area of WM bundles in tumour infiltrated striatum by the total area of tumour infiltrated striatum. For analysis in Extended Data Fig. 6i,k, tdTomato spots were additionally filtered on a surface generated for the virally targeted area using GFP fluorescence.

Analysis of Thy1-YFP (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 3a,c) and neurofilament (Extended Data Fig. 3e) mean fluorescence intensity, as well as GFAP+ cell density (Extended Data Fig. 4e) and CD68 integrated density (Extended Data Fig. 4g) was performed in ImageJ on maximum-intensity projection (MIP) images from a 3i spinning-disk confocal microscope using a custom script. Individual bundle ROIs were manually drawn and tdTomato+ and GFAP+ cells manually counted. ROI area and mean fluorescence intensity was measured using the Measure function. Mean fluorescence intensity was normalized to the average of mean fluorescence intensities in contralateral bundles (≥5 bundles per animal). CD68 integrated density was measured by first thresholding CD68 channel with Li autothreshold, and integrated density (IntDen) was quantified using the AnalyzeParticles function. Analysis of distance of axonal varicosities to a tumour cell body or tumour cell process (Fig. 3f) was performed in ImageJ on single z-plane images. Individual varicosities (n = 111) within tumour-involved WM were manually selected, and the distances between varicosities and tumour cells were measured using the Measure function. Varicosities located within a distance of <5 µm from the tumour cell body or cell process were categorized accordingly, while those at a distance of >5 µm classified as ‘No tumour cell’.

Analysis of GFAP area (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Figs. 5e and 6e) and CD68 intensity (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Figs. 5f and 6f) was performed in ImageJ on MIP images from the 3i spinning-disk confocal microscope using a custom script. Triangle threshold was used on the tdTomato image to generate a tdTomato ROI, which was used for ‘sham’. ROIs for the injury site were manually drawn in ImageJ. The injury site ROI was generated from the overlap of tdTomato and injury site ROIs. The ‘injury (excluding injury site)’ ROI was generated from the tdTomato ROI excluding the injury site ROI. The injury site was excluded from the analysis to avoid confounding effects of elevated neuroinflammation in this region after wounding. The GFAP area was calculated by thresholding the GFAP channel using the ImageJ Triangle threshold, and measuring the area covered within each ROI using the ImageJ AnalyzeParticles function. CD68 analysis was calculated by thresholding CD68 channel with Triangle or Li autothreshold, and integrated density (IntDen) was quantified using the AnalyzeParticles function. For both, measurements were normalized to their own sham control at each timepoint. Analysis of injury responses in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6 was carried out across all areas occupied by tdTomato+ tumour cells.

Analysis of GFAP area and CD68 intensity for time course in npp WT mice (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c) and PDX (Extended Data Fig. 4m,n) was performed as above for Sham mice, and measurements normalized to control (non-tumour-bearing brains) or contralateral, respectively. Analysis of vascular phenotypes (Extended Data Fig. 8e–h,j,l) was performed in ImageJ on MIP images from the 3i spinning-disk confocal microscope. Images were converted into RGB images, and the Vessel Analysis plug-in was used to produce thresholded vasculature images and derive the percentage of CD31+ area, vascular length (measured as the vascular length density) and the mean vascular diameter. Furthermore, the Skeletonize3D and AnalyzeSkeleton plugins were used on the thresholded images produced by the complete vessel analysis to derive number of branches. Colocalization of laminin or PDGFRB with CD31 was measured using thresholded images of CD31 and either laminin or PDGFRB, colocalization was determined using the Image Calculator AND function, and the percentage colocalization was calculated using the Measure Area function on CD31 and CD31 and laminin or CD31 and PDGFR, respectively. Analysis of IgG area (Extended Data Fig. 8n) was performed in ImageJ on MIP images from the 3i spinning-disk confocal microscope. The Triangle threshold was used on the tdTomato image to generate a tdTomato tumour ROI. IgG-positive areas were drawn manually and the area covered within each tdTomato ROI was measured using the ImageJ AnalyzeParticles function. To produce the rendered image in Fig. 3g, the z-stack confocal microscopy image was imported, 3D reconstructed and processed in Imaris v.10.1.0. 3D. Surfaces were constructed from the tdTomato/GFP channels using the Surfaces segmentation tool, combining automatic and manual segmentation. This resulted in 3D surfaces representing co-localized tumour cells and axon with axonal varicosities, which were subsequently animated in 3D alongside the three-channel tdTomato/GFP/mitoBFP confocal microscopy images (Supplementary Video 1).

Image quantification of H&E images

For H&E image quantification, the watershed method was applied to grey scale smoothed images using the Python package squidpy55 for segmentation of nuclei. The function skimage.measure.regionprops_table from the Python package scikit-image70 was used to count the number of cells.

Atomic-force microscopy

Thy1-YFP brains bearing intermediate npp tumours were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before sectioning at 10 μm on the Leica cryostat. Atomic-force microscopy measurements were performed using an MFP-3D BIO Inverted optical atomic-force microscopy (Asylum Research) mounted on a Nikon TE2000-U inverted fluorescence microscope and placed onto a vibration-isolation table (Herzan TS-150). Silicon nitride cantilevers with a nominal spring constant of 0.06 N m−1 and a borosilicate glass spherical tip with 5 μm diameter (Novascan Tech) were used. Cantilevers were calibrated using the thermal fluctuation method. Frozen sections were equilibrated to room temperature by immersion in PBS for 5 min before mounting. TdTomato and Thy1-YFP fluorescence were identified in the same section, the cantilever was placed in the corresponding regions and the specimens were indented at a 2 μm s−1 loading rate. The Young’s moduli of the samples were determined by fitting force curves with the Hertz model using a Poisson ratio of 0.5.

Single-cell RNA preparation

Mouse brains were collected into ice-cold HBSS medium and dissected into 1 mm coronal sections using a brain matrix (WPI, RBMS200C). Tumour regions were dissected out and mechanically dissociated into small pieces. Cells were isolated by papain dissociation (as above) and RNA libraries prepared using Chromium Next GEM Chip G Single Cell Kit (10x genomics; 1000127) and sequenced on Nova Seq X Plus PE 150.

scRNA-seq data analysis

Read selection and mapping

Reads were preprocessed and mapped to the mm10-2020-A mouse genome using 10x Genomics Cell Ranger v.7.0.1 (Supplementary Table 8 and 9). The tdTomato sequence, expressed by transformed cells, was added to the reference genome.

Cells and genes filtering

Cells with zero UMI counts for the 4 red blood cell markers Hbb-bs, Hba-a1, Hba-a2 and Hbb-bt and with either tdTomato expression ≤ 2 (microenvironment cells) or tdTomato ≥ 5 (tumour cells) were retained for further analysis. For all analysis, cells from WT mice were downsampled so that each genotype had ~20,000 cells. Cells with a proportion of mitochondrial genes of below 0.25 and log2-transformed total counts of between 9 and 16 were retained for further analysis. Genes with non-zero UMI counts in at least 0.5% of cells were retained for further analysis. As a result, the dataset presented in this study consists of 19,939 and 21,206 cells for the WT and Sarm1−/− samples, respectively, and of a total of 14,842 genes.

Identification of high-confidence tumour cells

Two rounds of data filtering were used to identify high-confidence tumour cells. First, the Harmony package58 was used to integrate the WT and Sarm1−/− datasets from this study with scRNA-seq datasets from normal mouse brain51,71, TAMs72 and from a mouse GBM model, which contains annotated tumour cells23. Specifically, data from each study were normalized using the sctransform package54 and merged after selection of common features using the SelectIntegrationFeatures function from Seurat60. Then, the batch correction function RunHarmony from the Harmony package58 was applied to the data in PCA space (generated with the RunPCA function in Seurat)60.

High-confidence tumour cells were defined as either (1) expressing at least 5 tdTomato UMI count; (2) predicted to be aneuploid using the copyKat package73; (3) predicted to be tumour cells using the integrated dataset annotation from ref. 58 and a random-forest approach in Harmony space. Specifically, labels from refs. 23,51,71,72 were used for training a random-forest model59, which was then applied to predict cell labels in the scRNA-seq data from this study. Finally, tumour cells with UMI counts for the Ptprc (Cd45) and Cd68 genes of >0 were discarded as these are considered to be immune-cell-specific markers.

In a second round of filtering, tumour cells were again integrated and clustered using the Harmony package58 and the Louvain approach74 both in Harmony space (same procedure as above, but this time the integration was done using scRNA-seq from this study only). Cells identified to be TAMs or endothelial cells based on markers from refs. 51,71 were removed from the high-confidence list.

Identification of high-confidence non-tumour cells

Cells with tdTomato UMI counts ≤ 2 and predicted to be diploid using the copyKat package73 were called high confidence.

Cell type annotation of high-confidence tumour and non-tumour cells

High-confidence tumour and non-tumour cells were integrated (between genotypes) and clustered separately using Harmony and Seurat58,60. Clustering was performed using the Louvain approach in Harmony space with resolution = 0.2 (ref. 74). Clusters were annotated using lineage markers and the gene enrichment analysis package fgsea67. Cluster annotation was finally checked manually for accuracy.

Cell type annotation of unassigned cells