Abstract

Amines are among the most common functional groups in biologically active molecules and pharmaceuticals1,2,3, yet they are almost universally treated as synthetic end points4. Here we report a strategy that repositions native primary, secondary and tertiary amines as handles for cross-coupling. The platform relies on in situ activation through borane coordination and exploits a copper catalytic redox system that generates amine-ligated boryl radicals, which undergo β-scission across the C(sp3)–N bond to release alkyl radicals. These intermediates engage in copper-catalysed cross-couplings with a broad range of C-based, N-based, O-based and S-based nucleophiles. The method tolerates diverse amine classes, enables modular functionalization and supports late-stage diversification of complex drug scaffolds. Also, amides can be incorporated into the manifold through reductive funnelling. This work establishes a general approach to deaminative C–N bond functionalization and introduces a distinct approach for making and modifying drug-like molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Amines are among the most widespread motifs in biologically active molecules1. They play critical roles in biological signalling (for example, neurotransmitters, hormones) and are embedded in the core of numerous pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. A systematic analysis of the ChEMBL database5, comprising more than 420,000 unique biologically active small molecules, reveals that amines feature in more than 60% of entries. Tertiary amines rank as the third most common functional group, whereas secondary and primary amines are fifth and twelfth, respectively2 (Fig. 1a). Similarly, an AbbVie survey of building blocks used in medicinal chemistry campaigns found amines to be the most abundant functional group across synthetic intermediates for drug-discovery programmes3 (Fig. 1b). This prevalence as both targets and precursors, combined with their structural diversity and accessibility, makes amines prime candidates not only as end targets but also as starting points for molecular diversification6.

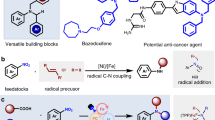

a, Amines, and more specifically tertiary amines, are one of the most common functionalities in biologically active molecules. b, Amines are the most common functionality in the building blocks used in medicinal chemistry research. c, Strategy enabling the use of primary, secondary and tertiary amines in deaminative cross-coupling through radical intermediates. d, Proposed amine activation for C(sp3)–N β-scission and computational studies (ωB97X-D3/def2-TZVP//ωB97X-D3/def2-SVP). ΔG° values are in kcal mol−1. e, Proposed copper catalytic manifold for deaminative cross-coupling through β-scission of amine-ligated boryl radicals. β-SC, β-scission; Nu, nucleophile.

Yet, in synthesis, amines are almost exclusively treated as end points. Unlike alkyl halides or carboxylic acids, which serve as standard retrons for derivatization, amines are rarely used for direct functional group interconversion7. From a medicinal chemistry perspective, however, the ability to interconvert amines with other polar or non-polar functionalities would be of profound value6,8. Even a single change at the amine site can greatly alter pharmacological profiles, biological availability and metabolic stability. For example, introduction of a methylamine into penicillin G furnishes ampicillin, with enhanced Gram-negative activity9. Conversely, replacing the same amine with a hydroxyl or a carboxylic acid modifies both scope and potency. Similarly, conversion of the primary amine in the cyclopropyl anti-cancer agent ACC into an alcohol, nitrile or carboxylate (for example, NSC154619) yields distinct biological effects10. Even subtle changes, such as formation of alcohol metabolites from dapoxetine11 or sertraline12, can affect efficacy and require monitoring during manufacturing.

Despite this functional leverage, each deaminated analogue typically requires a new synthetic route, often involving multistep sequences with protection/deprotection or specialized precursors. This inefficiency arises from the poor leaving group character of amines, the high C(sp3)–N bond dissociation energies (>80 kcal mol−1)13 and their intrinsic basicity, all of which make direct deaminative functionalization largely elusive. Radical-based retrosynthetic logic has revolutionized C–C and C–Y (Y = heteroatom) bond construction but general radical deamination strategies across primary, secondary and tertiary amines remain undeveloped4. Present methods largely target primary amines through pre-functionalization or oxidation-state modulation (for example, diazonium salts, pyridinium, quaternary ammonium intermediates)14,15,16,17,18,19,20. However, these cannot provide a unified platform in which all amine classes undergo identical deaminative radical generation and downstream cross-coupling.

In this work, we report a strategy for divergent deaminative functionalization, enabled by in situ activation of amines through borane coordination (Fig. 1c). This process delivers amine–borane complexes that are generally stable species21. However, under a copper-based redox system, they undergo homolytic activation to yield amine-ligated boryl radicals. Instead of using these intermediates in standard radical settings such as borylation22 or halogen-atom transfer (XAT)23, we exploit their potential to undergo β-scission across the C(sp3)–N bond and convert amines A into alkyl radicals B. These species can be engaged in a series of cross-couplings with a wide range of carbon and heteroatom nucleophiles (N, O, S and F), enabling the direct replacement of the amino group with diverse functionalities (C). This approach applies to primary, secondary and tertiary amines, overcomes some of the long-standing barriers to C–N bond activation and offers new retrosynthetic logic for the diversification of complex molecules, including late-stage modifications of drugs.

Direct homolysis of C(sp3)–N bonds in amines remains an unsolved problem in radical chemistry. On oxidation or H-atom transfer (HAT)24, amines typically form α-aminoalkyl radicals that are too stable to undergo β-scission and the amine itself is a notoriously poor leaving group. This combination makes C–N bonds intrinsically resistant to fragmentation and has prevented the use of amines as radical precursors in cross-coupling chemistry.

We suggested that this barrier could be overcome by installing a polarizable substituent (Y) at nitrogen (D) to access α-ammonium radicals (E) predisposed to β-fragmentation (Fig. 1d). For this strategy to succeed, the substituent must be: (1) easily installable onto primary, secondary and tertiary amines leading to ammonium species (D); (2) capable of radical generation (E) through either single-electron transfer (SET) or HAT; and (3) able to destabilize the resulting radical intermediate sufficiently to make β-scission both thermodynamically favourable and kinetically viable. A strong driving force, such as formation of an N = Y π-bond, could further promote bond cleavage.

To explore this concept, we performed density functional theory calculations on a series of N-Bn α-ammonium radicals exploring their β-scission chemistry. The reference system (Y = CH2, E1) showed endothermic fragmentation, consistent with the inertness of these radicals. We next examined radicals bearing Y = NH• (E2) and O• (E3), mimicking hydrazine and hydroxylamine motifs. These two cases featured, respectively, highly endergonic fragmentation (E2) and facile carbocation rather than radical formation (E3) (see Supplementary Information). Combined with their limited synthetic accessibility, these motifs are poorly suited as general alkyl radical progenitors. By strong contrast, the Y = BH2•− system E4 showed highly exergonic β-scission, driven by the formation of a strong B = N π system in the departing fragment. These results suggest the stable Lewis acid–base complex amine–borane21 as promising and modular precursors for C–N bond cleavage through radical pathways. Notably, the key amine-ligated boryl radical intermediate is formally isoelectronic with a conventional alkyl radical (E5), yet its reactivity diverges sharply. Although alkyl radicals are typically stable and do not fragment, our computational results indicate that boryl radical E4 ought to undergo C(sp3)–N cleavage. This contrast arises from the polarized character of the B–N bond and the electrophilicity of boron, which destabilize the radical centre and bias the system towards bond scission. Important experimental support for our boryl-radical-based C(sp3)–N activation blueprint comes from electron paramagnetic resonance studies by Roberts and colleagues, who observed that (i-Pr)2EtN–BH2• generates i-Pr• through thermal β-scission25,26. However, this reactivity has never been synthetically exploited or even observed.

To translate this radical β-scission reactivity into a synthetically useful platform, we designed a copper-catalysed cross-coupling manifold for direct functionalization of amines with diverse nucleophiles (Fig. 1e). Mechanistically, we imagined a [Cu(I)/Cu(II)/Cu(III)] redox cycle initiated by nucleophile coordination to [Cu(I)] to give a Nu–[Cu(I)] species. At this point, SET with an oxidant such as cumylO2SiMe3 would generate a cumyloxy radical (F) and Nu–[Cu(II)]. The electrophilic cumylO• would serve as a polarity-matched HAT agent, selectively abstracting a H-atom from the amine–borane complex G (ref. 27), which can be conveniently accessed by in situ coordination of A with BH3. This step would form the amine-ligated boryl radical H. Following key β-scission, the liberated alkyl radical B would be captured by the Nu–[Cu(II)] complex, forming a putative alkyl, Nu–[Cu(III)] intermediate and forging the new C(sp3)–Nu bond in product C through reductive elimination. Alternatively, direct reaction between the alkyl radical B and the Nu–[Cu(II)] intermediate can also lead to product formation28,29.

We began by testing the feasibility of this concept using a benzylic amine 1a as a model radical precursor (Fig. 2a). Treatment of 1a with H3B–SMe2 (1.0 equiv.) in THF provided the desired amine–borane that was directly engaged with Ph–B(OH)2 as the nucleophile under copper catalysis. Specifically, the use of Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (1 mol%), bathophenanthroline (1.2 mol%), cumylO2SiMe3 (3.0 equiv.), in EtOAc at room temperature, gave the desired deamination-arylation product 2a in 50% yield.

a, Evaluation of amines 1a–1v in the cross-coupling with Ph–B(OH)2. b, Scope of boronic acids in the deaminative cross-coupling with 1d. ‡Reaction run with amine (2.0 equiv.), Ph–B(OH)2 (1.0 equiv.), 2.5 mol% [Cu] and 3 mol% bathophen. *Reaction run with 2.5 mol% [Cu] and 3 mol% bathophen. †Acetone was used as solvent. Ar, p-TBSO-C6H4; r.t., room temperature.

We then examined the influence of amine class and substitution. Both secondary (1b) and tertiary (1c) amines underwent smooth deaminative arylation, furnishing 2a in 62% and 56% yield, respectively. Crucially, β-scission took place selectively at the benzylic C(sp3)–N bond, thus leading to the thermodynamic benzylic radical product30. We next evaluated medicinally relevant cyclic amines31. Substrates derived from pyrrolidine (1d), piperidine (1e) and morpholine (1f) underwent clean C(sp3)–N fragmentation and cross-coupling to 2a, effectively replacing the nitrogen-containing ring with an aryl group in good to excellent yields. This transformation offers a powerful route to ‘molecular rigidification’ and ‘ring replacement’, two strategies often used to adjust physicochemical properties in lead optimization campaigns32,33.

By contrast, the benzylic amine 1g afforded 2b in lower yield, consistent with the expected decrease in the rate constant associated to the formation of a primary compared with a secondary radical. This divergence enabled a first look at chemoselectivity. Substrate 1h featuring two potential benzylic C–N cleavage sites reacted exclusively at the position leading to a secondary radical giving 2c with only traces of 2b. This highlights the inherent response of the system to radical stabilization factors.

To experimentally investigate the kinetics of the C(sp3)–N bond fragmentation, we generated the amine-ligated boryl radical directly by means of nanosecond laser flash photolysis of the corresponding amine–borane complex 1c under inert conditions (using HAT to cumylO•). The transient species exhibited a characteristic ultraviolet–visible absorption (λmax = 360 nm) and decayed following first-order kinetics with a lifetime of τ = 5.7 μs at room temperature (kobs ≈ 2 × 105 s−1) (see Supplementary Information for more details). This relatively long-lived behaviour suggests that β-scission is kinetically slow compared with most bimolecular boryl radical reactions (for example, XAT)34, which typically proceed on the sub-nanosecond timescale. The observed delay underscores the high kinetic barrier to C(sp3)–N cleavage, despite the favourable thermodynamics predicted by density functional theory (Fig. 1e). Notably, this slow unimolecular event is still successfully used in a catalytic manifold, suggesting that the surrounding redox and coordination environment, notably the rate of radical generation and copper-mediated capture, has been finely tuned to accommodate this constraint. These findings highlight the non-trivial kinetic balance required for this reaction to operate under mild conditions and distinguish this β-scission from faster, classical radical fragmentation processes (for example, radical probe processes).

The method was also compatible with other functionalized C(sp3) systems. A propargylic amine 1i delivered the corresponding arylated product 2d in 45% yield, with no detectable radical isomerization. By contrast, the allylic substrate 1j showed extensive decomposition, delivering product 2e in low yield, probably because of the competing side reactions of the allylic radical. Finally, we examined the strategy’s feasibility on substrates that generate unactivated alkyl radicals. Despite the inherent challenges associated with these β-fragmentations, we successfully used 1k–1q, which afforded 2f–2l in moderate to good yields. These substrates demonstrate deaminative cross-coupling over both acyclic and (hetero)cyclic systems of various size and also featuring HAT-activated positions (1k and 1p). Furthermore, a series of amino acid derivatives 1r–1v enabled direct modification at the N-terminus, a transformation orthogonal to conventional decarboxylative approaches. Although the resulting α-ester/amide radicals have moderate electrophilic character35, the desired products 2m–2q were obtained in good yields. We propose that the stabilized nature of this radical intermediate facilitates β-fragmentation, thereby improving compatibility with the copper catalytic cycle and expanding the scope of this methodology. Amines leading to tertiary radicals were also examined. Although these derivatives could be activated, they did not furnish the arylated product but instead gave the hydro-deaminated derivative. We attribute this outcome to the lower propensity of tertiary radicals to engage in metal-catalysed cross-couplings, which increases the likelihood of competing HAT pathways (see Supplementary Information Section 7). Overall, although the present platform exhibits optimal reactivity with benzylic amines and substrates leading to stabilized radicals, these systems are particularly abundant in medicinal chemistry. Efforts to further control and push the β-fragmentation event to target further unactivated aliphatic systems are underway.

We then turned to the nucleophile scope (Fig. 2b). Using 1d as the representative amine, we evaluated a broad range of aryl boronic acids. Both electron-rich (2s and 2t) and electron-poor (2u and 2v) para-substituted derivatives worked well, demonstrating tolerance with OMe, CF3 and F functionalities. Both meta-substituted (2w and 2x) and ortho-substituted (2y and 2z) arenes were installed effectively and 2,6-difluorophenylboronic acid gave product 2aa despite its known tendency towards rapid protodeboronation under standard Suzuki conditions, an outcome we attribute to the anhydrous conditions of our reaction36,37.

We also explored heteroaryl boronic acids, which are challenging substrates under traditional coupling protocols. High-yielding couplings were achieved with indole (2ab), benzofuran (2ac), furans (2ad and 2ae), thiophenes (2af and 2ag), isoxazole (2ah) and 2,5-disubstituted pyridines (2ai and 2aj), delivering products with handles amenable to SNAr-based derivatization. 2-chloro-5-pyrimidine boronic acid also performed reliably (2ak), expanding the reach of the method into heterocycle-rich space.

Beyond arylation, we evaluated vinyl and cyclopropyl nucleophiles. Both species underwent productive coupling to assemble the corresponding C(sp3)–C(sp2) (2al) and C(sp3)–C(sp3) (2am) bonds in moderate to good yields. The formation of cyclopropylated product 2am is particularly important, given the increasing use of this motif in drug discovery owing to its conformational and metabolic properties38.

A key conceptual feature of our platform is its potential for divergent reactivity. In principle, the same amine–borane precursor could undergo β-scission and radical capture with a wide variety of nucleophilic coupling partners, enabling modular interconversion of amines into many distinct functionalities. However, this poses a substantial practical challenge, as chemically diverse nucleophiles must behave similarly under a single catalytic regime, despite differences in polarity, transmetalation propensity, redox stability and ligand-exchange kinetics. To preserve the generality of the platform, we intentionally minimized individual reaction optimization and instead sought to establish proof of reactivity across key bond-forming classes (see Supplementary Information Sections 4.2 and 5 for optimization and specific reaction conditions). We focused on transformations of high relevance to medicinal chemistry, such as C–C, C–N, C–O and C–S bond construction.

We first explored carbon-based nucleophiles using 1d as the representative amine (Fig. 3a). The use of Me3Si–CN enabled efficient deaminative cyanation, furnishing the corresponding nitrile 3a in good yield. This represents a formal retro-Curtius transformation, converting a basic amine into a polar nitrile handle that was readily hydrolysed to the carboxylic acid 3b. This conversion profoundly alters the physicochemical profile of the molecule, with implications for both lead diversification and metabolic pathway engineering39.

a, Divergent use of nucleophiles to enable direct deaminative cross-coupling on 1d, leading to C(sp3)–C, C(sp3)–N, C(sp3)–O and C(sp3)–S bond formation. b, Two-step approach for deaminative diversification of 1w through intermediate 6d. Yields reported for products 3g–3i, 4g–4p, 5b–5i and 7a are from intermediate 6d. Reaction conditions for the Ag-mediated nucleophile displacements: AgOTf (2.0 equiv.), nucleophiles (3.0 equiv.), CH2Cl2 (0.1 M), 3 Å molecular sieves, r.t., 16 h. See Supplementary Information for specific reaction conditions for the divergent functionalization. DAST, diethylaminosulfur trifluoride; dr, diastereomeric ratio.

Encouraged by this, we evaluated preliminary alkyl cross-coupling reactions with organometallic reagents. Although the use of Grignard reagents resulted in no reactivity, treatment with Et2Zn afforded the corresponding ethylated product 3c in 27% yield and the use of a copper acetylide delivered the alkynylated product 3d in 36% yield. Although these yields are moderate, they serve as blueprints for reactivity, validating the feasibility of constructing C(sp3)–C(sp3) and C(sp3)–C(sp) bonds using this deaminative approach.

Unlike enzymatic transamination39, which requires carbonyl intermediates, there is no known biological or chemical system that directly replaces one amine with another N-functionality at a C(sp3) centre by means of radical intermediates. We demonstrate that our platform has some potential to enable this abiotic N-for-N exchange. Reaction of 1d with Me3Si–N3 and Me3Si–NCS yielded the corresponding azide 4a (38%) and isothiocyanate 4b (41%) products, both valuable intermediates for further derivatization. Furthermore, indazole and phthalimide were engaged as nitrogen nucleophiles to give transaminated products 4c and 4d in 58% and 41% yield, respectively. Although common nucleophiles such as amides, carbamates and sulfonamides were unreactive, these results provide a proof of concept for a new disconnection logic for C(sp3)–N bonds directly from amines.

C–O bond formation is of particular interest for modulating polarity and metabolic profiles in drug leads. Although direct use of alcohols or phenols was unsuccessful under the standard conditions, we found that N-hydroxyphthalimide effectively replaced the amine moiety with an oxygen-based fragment, delivering the O-alkylated phthalimide product 5a in good yield. This transformation serves as a formal retro-Mitsunobu reaction, in which subsequent SET reduction unveils the corresponding alcohol, offering a new route to amine-to-OH conversions relevant to fragment tuning and solubility optimization40.

Finally, we examined sulfur nucleophiles. Both diphenyl disulfide and 2,2′-dithiobis(benzothiazole) proved effective, delivering the corresponding thioether products (6a and 6b) in high yields. Of note, the use of commercially available AgSCF3 enabled direct incorporation of the trifluoromethylthio (SCF3) group (6c), a highly valued motif in medicinal chemistry for modulating lipophilicity and metabolic resistance41. Notably, we have been able to extend the divergent functionalization platform to amines 1l and 1p that also underwent cyanation (3e and 3f) and transamination with 2-Cl-indazole (4e and 4f) in moderate yields.

We believe that the present study provides foundational evidence for a modular interconversion platform enabling construction of C–C, C–N, C–O and C–S bonds based on a single, native amine functional group. However, key limitations remain: several pharmaceutically relevant nucleophiles, such as alcohols, amides and carbamates, did not react under the standard conditions, probably because of mismatched polarities or [Cu(I/II)]-coordination profiles. Hence, we became interested by the possibility of decoupling the β-fragmentation event from nucleophile engagement and instead convert the amine into a stable, functionally versatile intermediate amenable to diversification. Inspired by reports showing that sulfides can be displaced by soft nucleophiles under Lewis-acidic conditions, we focused on developing an amine-to-sulfide transformation leading to a modular handle for further diversification42,43.

Using 1-phenyl-1H-tetrazole-5-thiol as a sulfur donor, we found that the corresponding alkyl sulfide 6d could be formed in good yield under our standard copper catalytic conditions (Fig. 3b). This species served as a reactivity linchpin, undergoing a broad range of nucleophilic substitution reactions under silver Lewis-acid-promoted conditions. For instance, treatment with amides (4g), carbamates (4h) and sulfonamides (4i) lead to the replacement of the piperidine ring in 1w with a series of diverse nitrogen-based functionalities, effectively accomplishing a two-step abiotic transamination.

This strategy also unlocked access to previously incompatible oxygen-based nucleophiles. Alcohols and carboxylic acids reacted smoothly with 6d to furnish the corresponding ether (5b) and ester (5c), respectively, in good yields. Moreover, silyl enol ethers engaged efficiently, enabling direct installation of α-carbonyl groups in place of the original amine (3g and 3h). This represents a powerful conversion, expanding the platform into polarity inversion chemistry. Finally, treatment with diethylaminosulfur trifluoride allowed for direct conversion of the amine into a fluorinated motif (7a) useful for pharmacokinetic tuning.

This reactivity could be easily extended to several other nucleophiles belonging to the classes discussed above (that is amides: 4j–4m; sulfonamides: 4n and 4o; alcohols: 5d–5f; carboxylates: 5g–5i; and silyl enol ethers: 3h and 3i). The use of celecoxib (4p) and isoxepac (5i) illustrates the tolerance to complex and densely functionalized nucleophilic partners. Notably, some of these transformations could also be run in a fully telescoped fashion with no isolation of intermediate 6b (see Supplementary Information Section 8).

Given the ubiquity of amines in pharmaceuticals, we were particularly interested in making use of our reaction manifold for divergent late-stage functionalization of complex drug molecules. As a case study, we selected three widely prescribed compounds and evaluated them under our standard conditions following in situ BH3 coordination. The antidepressant sertraline (1x) and Parkinson disease treatment rivastigmine (1y) feature benzylic secondary amines and other reactive motifs, including benzylic and α-N C(sp3)–H bonds (susceptible to HAT by electrophilic radicals), activated aryl chlorides (prone to XAT or metal-catalysed coupling) and a carbamate functionality. Under conventional late-stage editing strategies, these sites, particularly the benzylic or aryl halide positions, would typically be targeted for derivatization. By contrast, selective modification at the amine position remains out of reach. As a result, any analogue bearing structural changes at the amine site would generally require an independent de novo synthesis. Our platform overcomes this barrier: the NHMe moiety in sertraline was directly replaced with a range of electronically and structurally distinct fragments, including aryl (3j and 3k), nitrile (3l), O-phthalimide (5j) and thioether (6e and 6f) (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the formation of intermediate 6g enables further diversification with azetidinone (4q) and alcohol (5k) substituents. In the case of rivastigmine, we achieve ten different diversifications based on the replacement of the amine functionality with C-based (3m–3o), N-based (4r), O-based (5l–5n) and S-based substituents (6h–6j) (Fig. 4b). Each of these modifications would traditionally demand separate synthetic routes, yet here they are accessed from a common intermediate under a unified catalytic protocol.

a, Late-stage functionalization of sertraline 1x. Yields reported for products 4q and 5k are from intermediate 6g. b, Late-stage functionalization of rivastigmine 1y. Yields reported for products 4r, 5m and 5n are from intermediate 6k. c, Late-stage functionalization of dapoxetine 1z. d, Diversification of the alkyl side chain of cinacalcet 1aa. Yields reported for products 4t, 5o and 5p are from intermediate 6o. e, Use of deaminative couplings on lactam 1ab. Yields reported for products 4u–4w and 3t are from intermediate 6d. See Supplementary Information for specific reaction conditions for the divergent functionalization. Ar, 1-naphthyl.

Similarly, the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor dapoxetine (1z) bearing a tertiary amine and other groups potentially incompatible under radical chemistry (for example, due to preferential oxidation of the naphthol unit) underwent smooth deamination functionalization, affording structurally diversified products (3p–3s, 4s and 6l–6n) in good to moderate yields (Fig. 4c). These transformations enable the rapid generation of analogues inaccessible with traditional methods, supporting applications in lead optimization and structure–activity exploration.

To further demonstrate the synthetic usefulness of our approach, we examined the calcium-sensing receptor agonist cinacalcet 1aa, a drug featuring a benzylic amine adjacent to an alkyl chain (Fig. 4d). Following BH3 coordination and copper-catalysed thiolation, we obtained 6o, serving as an entry point to downstream diversification. From this species, we prepared a set of derivatives in which the original NH group in the drug core was replaced by an O-atom (5o) or the non-benzylic α-amino methylene unit was oxidized to the corresponding amide (4t), a challenging transformation owing to the inherent tendency of oxidants to target the benzylic C(sp3)–H position. We further accessed ester analogue 5p as a structural amide isostere. All three modifications were achieved in only two steps from the parent drug.

The use of this methodology extends beyond amines. We found that amides such as 1ab can also be engaged through a tandem reduction–borane complexation sequence, enabling their incorporation into the deaminative platform (Fig. 4e). This enabled smooth conversion of 1ab into 6d, proving access to a range of structurally diverse heterocycles through precise skeletal modifications. Displacement with oxazolidin-2-one and 1-methylimidazolidin-2-one led to the formation of cyclic carbamate (4u) and urea (4v), effectively replacing the α-carbonyl methylene with an oxygen and a nitrogen atom, respectively. Substitution with an azetidinone led to a formal one-carbon-ring contraction, affording a four-membered heterocycle (4w). Finally, interception with a silyl enol ether delivered a product bearing an α-carbonyl methylene group in place of the original nitrogen, thus accomplishing a valuable N-to-C transmutation (3t). These transformations demonstrate that amide-derived substrates, once funnelled through the amine–borane manifold, can undergo precise and divergent functionalization.

Conclusions

We have developed a strategy for radical-mediated deaminative cross-coupling that applies to all classes of amines (primary, secondary and tertiary) and is at present optimized for systems that proceed through benzylic and stabilized carbon radicals. This transformation exploits the unique ability of amine-ligated boryl radicals to undergo β-scission as blueprint for C(sp3)–N bond activation. This converts amines into alkyl radicals that engage in Cu-catalysed C(sp3)–C, C(sp3)–N, C(sp3)–O and C(sp3)–S bond formation. The methodology tolerates a wide range of amine classes, enables selective fragmentation even in complex environments and demonstrates high chemoselectivity. The approach is applicable to late-stage diversification of pharmaceuticals, providing divergent access to analogues that would otherwise require individual synthetic efforts. Although certain nucleophile classes remain challenging, the development of a modular amine-to-sulfide conversion offers a powerful workaround, enabling downstream diversification with otherwise incompatible nucleophiles under orthogonal conditions. We hope that the broad scope and mechanistic modularity will further stimulate the development of this concept positioning amine–boranes and their β-scission as a versatile tool for synthetic and medicinal chemistry.

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information and can also be obtained from the corresponding author on request.

References

Lawrence, S. A. Amines: Synthesis, Properties and Applications (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004).

Ertl, P., Altmann, E. & McKenna, J. M. The most common functional groups in bioactive molecules and how their popularity has evolved over time. J. Med. Chem. 63, 8408–8418 (2020).

Wang, Y., Haight, I., Gupta, R. & Vasudevan, A. What is in our kit? An analysis of building blocks used in medicinal chemistry parallel libraries. J. Med. Chem. 64, 17115–17122 (2021).

Kim, J. U., Lim, E. S., Park, J. Y., Jung, D. & Lee, S. Radical approaches for C(sp3)–N bond cleavage in deaminative transformations. Chem. Commun. 61, 6997–7008 (2025).

Zdrazil, B. et al. The ChEMBL Database in 2023: a drug discovery platform spanning multiple bioactivity data types and time periods. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D1180–D1192 (2023).

Blakemore, D. C. et al. Organic synthesis provides opportunities to transform drug discovery. Nat. Chem. 10, 383–394 (2018).

Brown, D. G. & Boström, J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone? J. Med. Chem. 59, 4443–4458 (2016).

Hili, R. & Yudin, A. K. Making carbon-nitrogen bonds in biological and chemical synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 284–287 (2006).

Acred, P., Brown, D. M., Turner, D. H. & Wilson, M. J. Pharmacology and chemotherapy of ampicillin—a new broad-spectrum penicillin. Br. J Pharmacol Chemother. 18, 356–369 (1962).

Adams, M. E. et al. Preparation of N-(1-(aminomethyl)cyclopropyl) (aryl or heteroaryl) carboxamide derivatives as modulators of somatostatin receptor 4 (SSTR4) (2025).

Darcsi, A., Tóth, G., Kökösi, J. & Béni, S. Structure elucidation of a process-related impurity of dapoxetine. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 96, 272–277 (2014).

Quallich, G. J. Process for preparing a chiral tetralone, useful as an intermediate for sertraline (1995).

Luo, Y.-R. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies 1st edn (CRC Press, 2007).

Correia, J. T. M. et al. Photoinduced deaminative strategies: Katritzky salts as alkyl radical precursors. Chem. Commun. 56, 503–514 (2020).

Klauck, F. J. R., James, M. J. & Glorius, F. Deaminative strategy for the visible-light-mediated generation of alkyl radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12336–12339 (2017).

Basch, C. H., Liao, J., Xu, J., Piane, J. J. & Watson, M. P. Harnessing alkyl amines as electrophiles for nickel-catalyzed cross couplings via C–N bond activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5313–5316 (2017).

Ashley, M. A. & Rovis, T. Photoredox-catalyzed deaminative alkylation via C–N bond activation of primary amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18310–18316 (2020).

Steiniger, K. A., Lamb, M. C. & Lambert, T. H. Cross-coupling of amines via photocatalytic denitrogenation of in situ generated diazenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11524–11529 (2023).

Quirós, I. et al. Isonitriles as alkyl radical precursors in visible light mediated hydro- and deuterodeamination reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317683 (2024).

Aida, K. et al. Selective C–N bond cleavage in unstrained pyrrolidines enabled by Lewis acid and photoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 30698–30707 (2024).

Staubitz, A., Robertson, A. P. M., Sloan, M. E. & Manners, I. Amine− and phosphine−borane adducts: new interest in old molecules. Chem. Rev. 110, 4023–4078 (2010).

Kim, J. H. et al. A radical approach for the selective C–H borylation of azines. Nature 595, 677–683 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Tilby, M. J. & Leonori, D. Boryl radical-mediated halogen-atom transfer enables arylation of alkyl halides with electrophilic and nucleophilic coupling partners. Nat. Synth. 3, 1221–1230 (2024).

Griller, D., Howard, J. A., Marriott, P. R. & Scaiano, J. C. Absolute rate constants for the reactions of tert-butoxyl, tert-butylperoxyl, and benzophenone triplet with amines: the importance of a stereoelectronic effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 619–623 (1981).

Baban, J. A., Marti, V. P. J. & Roberts, B. P. Ligated boryl radicals. Part 2. Electron spin resonance studies of trialkylamin–boryl radicals. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1723–1733 (1985).

Marti, V. P. J. & Roberts, B. P. Homolytic reactions of ligated boranes. Part 5. Spin-trapping and other addition reactions of ligated boryl radicals. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1613–1621 (1986).

Hioe, J., Karton, A., Martin, J. M. L. & Zipse, H. Borane–Lewis base complexes as homolytic hydrogen atom donors. Chem. Eur. J. 16, 6861–6865 (2010).

Zhang, Z., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed radical relay in C(sp3)–H functionalization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 1640–1658 (2022).

Mandal, M., Buss, J. A., Chen, S.-J., Cramer, C. J. & Stahl, S. S. Mechanistic insights into radical formation and functionalization in copper/N-fluorobenzenesulfonimide radical-relay reactions. Chem. Sci. 15, 1364–1373 (2024).

Zipse, H. in Radicals in Synthesis I (ed. Gansäuer, A.) Ch. 28, 163–189 (Springer, 2006).

Vitaku, E., Smith, D. T. & Njardarson, J. T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 57, 10257–10274 (2014).

Churcher, I., Newbold, S. & Murray, C. W. Return to Flatland. Nat. Rev. Chem. 9, 140–141 (2025).

Lawson, A. D. G., MacCoss, M. & Heer, J. P. Importance of rigidity in designing small molecule drugs to tackle protein–protein interactions (PPIs) through stabilization of desired conformers. J. Med. Chem. 61, 4283–4289 (2018).

Baban, J. A. & Roberts, B. P. An electron spin resonance study of phosphine-boryl radicals; their structures and reactions with alkyl halides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1717–1722 (1984).

Garwood, J. J. A., Chen, A. D. & Nagib, D. A. Radical polarity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 28034–28059 (2024).

Cox, P. A. et al. Base-catalyzed aryl-B(OH)2 protodeboronation revisited: from concerted proton transfer to liberation of a transient aryl anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13156–13165 (2017).

Lozada, J., Liu, Z. & Perrin, D. M. Base-promoted protodeboronation of 2,6-disubstituted arylboronic acids. J Org. Chem. 79, 5365–5368 (2014).

Shearer, J., Castro, J. L., Lawson, A. D. G., MacCoss, M. & Taylor, R. D. Rings in clinical trials and drugs: present and future. J. Med. Chem. 65, 8699–8712 (2022).

Hall, A., Chatzopoulou, M. & Frost, J. Bioisoteres for carboxylic acids: from ionized isosteres to novel unionized replacements. Biorg. Med. Chem. 104, 117653 (2024).

Hoque, M. A. et al. Electrochemical PINOylation of methylarenes: improving the scope and utility of benzylic oxidation through mediated electrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15295–15302 (2022).

Landelle, G., Panossian, A. & Leroux, F. R. Trifluoromethyl ethers and –thioethers as tools for medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 14, 941–951 (2014).

Kotturi, S. R., Tan, J. S. & Lear, M. J. A mild method for the protection of alcohols using a para-methoxybenzylthio tetrazole (PMB-ST) under dual acid–base activation. Tetrahedron Lett. 50, 5267–5269 (2009).

Zachmann, A. K. Z., Drappeau, J. A., Liu, S. & Alexanian, E. J. C(sp3)−H (N-phenyltetrazole)thiolation as an enabling tool for molecular diversification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202404879 (2024).

Acknowledgements

D.L. acknowledges the European Research Council for a grant (101086901). G.L. thanks the EU funding from an MSCA Postdoctoral Fellowship (project 101150093 - BRADOCO). C. Vermeeren, L. Foerster and M. Herberich are kindly acknowledged for experimental support. The authors gratefully acknowledge the computing time provided to them at the NHR Center NHR4CES at RWTH Aachen University (projects number rwth1268 and p0021519).

Funding

Open access funding provided by RWTH Aachen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z., G.L., T.S. and D.L. designed the project. Z.Z., G.L., T.S., Y.C.G. and G.V.A.L. ran all of the synthetic experiments and C.S. ran all of the computational studies. G.L. performed the laser flash photolysis studies. All authors analysed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Anna Bay, Kaid Harper and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Data

Cartesian coordinates.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Lonardi, G., Sephton, T. et al. Deaminative cross-coupling of amines by boryl radical β-scission. Nature 647, 913–920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09725-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09725-1