Abstract

Yakut communities from northeastern Siberia inhabit some of the coldest environments on Earth, preserving an extraordinary archaeological record. Their history was profoundly reshaped by the Russian conquest, which introduced cereals, pathogens and Christianity beginning in 1632 (refs. 1,2,3,4,5). However, the biological impact of these transformations remains unknown. Here we generated extensive ancient DNA data to elucidate contemporary changes in Yakut genomic diversity and oral microbiomes. We found Yakut origins tracing back to local populations that admixed with Trans-Baikal groups migrating as the Great Mongol Empire spread. Despite the Russian conquest, the Yakut gene pool and oral microbiomes appeared largely stable, although smallpox strains distinct from those documented in Europe by approximately 1650 circulated. Marital practices generally maintained low consanguinity, with the exception of one female bearing the latest markers of traditional shamanism, who was the daughter of second-degree relatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The Yakuts are the largest Indigenous group in Yakutia, northeastern Siberia, with a population of approximately half a million (Supplementary Information section 1.1). They inhabit one of the coldest regions on the planet, where annual thermal fluctuations exceed 100 °C, and winter temperatures can drop below −60 °C. Genetic and historical evidence suggest that the Yakuts descend from an ancestral population that migrated from the Lake Baikal area, possibly following the Great Mongol Empire expansion in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries6,7. To survive in this extreme environment, they developed specific cultural adaptations, with subsistence strategies centred on horse and cattle breeding, which provided transportation, clothing, meat and milk8. This contrasts with the reindeer-based economies of neighbouring Indigenous groups1 (for discussion of ethnonyms terminology, see Supplementary Information section 1.1.3). Furthermore, the Yakuts, along with other northeastern Siberian peoples, traditionally practiced shamanism, wherein practitioners intermediate with the spirit realms to guide and protect their communities8. The traditional lifeways of the Yakuts were dramatically disrupted beginning in 1632, when the Russian Empire initiated its conquest, primarily to expand its fur-hunting territories9.

The Russian conquest, followed by the development of Chinese trade by the late seventeenth century, introduced tobacco, vodka and carbohydrate-rich cereals into the region10,11. New exchanges brought infectious diseases, including smallpox, tuberculosis and pertussis, exposing immunologically naive Indigenous populations to devastating outbreaks2,12,13. Beyond its impact on diet and health, the Russian conquest altered the power dynamics among patrilocal clans, with one of them gaining control over hunting grounds and becoming key in the lucrative fur trade, accumulating substantial economic wealth3. Alongside traders, Christian proselytes increasingly reached the region, ultimately converting predominantly animist and shamanic Indigenous populations to Christianity3.

The upheavals of this period, combined with an archaeological record exceptionally well preserved within permafrost14,15,16, provide a unique opportunity to obtain fine-grained resolution into the biological, medical and societal consequences of a major lifestyle transition. Here we analyse an extensive collection of human skeletal remains and dental calculus from individuals living in Yakutia over the last 2,000 years, with a primary focus on approximately 1500–1922. Using extensive ancient DNA sequencing, we first reconstruct the historical origins of Yakut communities and assess the impact of the Russian conquest on their gene pool. We then examine whether associated dietary, lifestyle and social transformations influenced oral microbiota, pathogen exposure, marital practices and methylomes as potential markers of social and economic status.

Dataset and experimental design

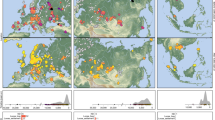

Excavations by the Mission Archéologique Française en Sibérie Orientale (MAFSO) between 2002 and 2018 (ref. 5) teaming together Russian and French archaeologists, uncovered an outstanding archaeological record across four key regions of Yakutia: Central Yakutia and the river basins of the western Vilyuy, northern Verkhoyansk (Yana) and eastern Indigirka (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Information sections 1.2 and 1.3 and Supplementary Fig. 1_2). The MAFSO expeditions aimed to investigate traditional Yakut societies and assess potential transformations following the Russian conquest3. To focus on Indigenous burial practices, excavations avoided Christian cemeteries, although funerary assemblages featuring Christian stellae, or yielding Christian crosses once unearthed, were included14,16 (Supplementary Information section 1.2). The Siberian climate preserved nearly intact human remains, textiles16,17 and a whole array of cultural artefacts, including ritual tripod or monopod wooden cups called chorons, which were owned by Yakut elites and used for drinking fermented horse milk (Fig. 1c,d).

The rich funerary assemblage provided exceptional insights into the social status, religious practices and presence of shamanism, among the buried individuals, spanning approximately 1500–1922 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1c). This period is divided into four archaeological stages, reflecting increasing Russian influence (Extended Data Fig. 1 and Supplementary Information section 1.2). Stage 1 (approximately 1500–1689) represents the traditional Yakut society before and during the early Russian conquest. Stage 2 (1689–1750) marks the Yakut ‘Golden Age’, when the Bozekov clan from AtDaban gained control over the prosperous fur trade, dealing in sables, martens and squirrels3,15. This period saw unprecedented economic, spatial and demographic expansion, with the Yakut language emerging as the lingua franca of northeastern Siberia. In stage 3 (1750–1800), demographic growth continued, whereas Russian influence over belief systems intensified, including legal measures against Indigenous spiritual traditions in favour of Orthodox Christian religion3. This process culminated in stage 4 (1800–1922), with widespread religious conversion campaigns.

a, Location of archaeological remains. Biological material sampled from 123 individuals spread across 113 archaeological sites. Those sites located in very close areas were grouped in pie charts to improve readability, with colours reflecting time stages. The origins of the three individuals positive for smallpox are indicated with a graphical representation of the virus. b, Map of Eurasia showing Yakutia and the burial location of one seventeenth century individual from Buryatia (black square). c, Cultural heat map summarizing the number of archaeological artefacts tracing wealth, leadership, shamanism and Christianity (Supplementary Information section 2.20) for stages 1–4. The M and F suffixes appended to individual names indicate genetic males and females, respectively. d, Typical Yakut artefacts reflecting wealth, leadership, shamanism and Christianity. α, Cauldrons, copper alloy with horse meat offering in a kytia (wooden pot) (individual Alyy, α1) or iron-made (Ebuguey2, α2); β, Signet ring (Celysse, β1 + β2; AC1, β3 + β4; Kerdugen, β5; Boulgouniakh1 and Boulgouniakh2, β6 + β7; Toutekh, β8; Atakh, β9 + β10); χ, Ring (Kureleekh); δ, Solar disk (Sordonokh); ε, Bronze torque necklace, twisted with counterweight composed of pearls and metal ornaments (Eletchei2, ε1) or flat with counterweight made of silver coins (Sordonokh, ε2); φ, Earrings (Lepsei2, φ1; Kyrdjakhastaala, φ2; Bere1, φ3); γ, Batilla, sword with a long wooden handle (AtDaban12, γ1; AtDaban11, γ2); η, Copper alloy bracelet (Kureleekh); ɩ, Choron, carved wooden monopod or tripod vase (Kerdugen, ɩ1; Bakhtakh3, containing an offering of dairy product, ɩ2); σ, Mammoth ivory comb (Eletchei1); κ, Pipes (wooden bowl κ1; Bere, with its copper alloy bowl and wooden stem, κ2; AC1, mammoth ivory bowl, κ3); λ, Carved wooden spoon (Tottouk1); μ, Iron knife (IeralaakhA); ν, Iron curb chain for the harness (Boulgounniakh3); ο, Wooden saddle covered with decorative metal plate (Eletchei1); π, Iron stirrup (Boulgounniakh1).

To investigate Yakut history and assess the impact of the Russian conquest on population structure, marital practices, diet and health, we analysed a comprehensive collection of 122 individuals spanning stages 1–4. The dataset included 70 petrous bones, 17 long bone fragments, 54 teeth and 78 dental calculi, three lung biopsies and one muscle tissue sample (Supplementary Table 1a,b). Shotgun sequencing of 44.77 billion DNA templates from 612 libraries yielded genome-scale data suitable for downstream analyses in 59 males and 46 females, with a median depth of coverage of 2.13-fold (range of 0.017–69.85) and nuclear contamination estimates 0.5% or less for males (Supplementary Information sections 2.1–2.6 and Supplementary Figs. 2_1 and 2_2). Additionally, 74 oral microbiomes were reconstructed (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1a,b).

To further contextualize our findings, we characterized two more human genomes from a tooth of a seventeenth-century male from Buryatia (Fig. 1b) and a petrous bone of an Iron Age male from Central Yakutia (Mokp; Fig. 1a). The sequence data enabled the characterization of 16 methylomes and the imputation of 78.4 million genotypes in 90 individuals (Supplementary Information section 2.7 and Supplementary Table 1a). Population genetic analyses were conducted on pseudo-haploid data for 1.24 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the Allen Ancient DNA Resource v.5 (ref. 18) and genotypes imputed from the 1000 Genomes Project catalogue19.

Population history and Russian conquest

To contextualize Yakut genetic diversity within a broader human population framework, we performed a principal component analysis (PCA), projecting all ancient genomes (Supplementary Table 1d) onto the variation observed in modern Eurasian and American genomes (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1e). The first principal component separated European from Asian and American populations, with both ancient and modern Yakuts clustering with Asian populations. The second principal component further refined genetic affinities across Asia and the Americas, positioning modern and historical (stages 1–4) Yakuts near other Siberian groups, including the Evenk and Ulchi from the Russian Far East, as well as the Buryat from the Trans-Baikal region (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 3a).

a, PCA conducted on 597,573 SNPs for 2,761 modern Eurasian and American individuals, with 892 ancient Eurasian and American individuals and 106 ancient Yakut individuals projected. For clarity, all the modern individuals have been removed from the enlarged panel, except the modern Yakuts (black dots). The percentage indicated on each principal component reflects the explained fraction of genetic variance. b, Unsupervised ADMIXTURE20 genetic ancestry profiles (K = 10) calculated for 327,582 unlinked SNPs and 3,639 Eurasian modern and ancient individuals. Low-coverage individuals (less than 0.35-fold) are shown with transparency. In addition to the newly published Yakuts, two previously published22 Neolithic and one Iron Age Yakuts are shown. IA, Iron Age; LN, Neolithic. c, Length of haplotypic blocks donated by modern individuals (Asia refers to East, North-East and South-East Asian populations) to imputed ancient Yakut individuals (coverage of 0.35-fold or higher; minor allele frequency (MAF) of 0.01 or higher). Genetic outliers discussed in the text are highlighted in red. Box plots represent the 25%, 50% and 75% quantiles, with upper and lower whiskers showing values within the 1.5 interquartile range. Horizontal segments indicate the mean value for each category. d, Time estimates for admixture and Yakut founder events (generation time of 29 years), with error bars representing the standard error. Ni and N refer to the number of imputed and non-imputed individuals used, respectively.

The genetic makeup of historical Yakuts was remarkably homogeneous and closely resembled that of modern Yakuts. This was evident in their PCA placement (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3b, Supplementary Information section 2.10 and Supplementary Figs. 2_5 and 2_6), ADMIXTURE20 ancestry profiles (Fig. 2b) and fineSTRUCTURE21 clustering (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 3c). By contrast, the Iron Age Mokp individual exhibited distinct genetic affinities, clustering with modern Nganasans and Neolithic-to-Iron-Age individuals from Yakutia22. The genetic ancestry component maximized in Mokp was also predominant in all these individuals but was diluted in most historical and modern Yakuts through admixture with other genetic ancestries, shared with a subset of historical populations from the Baikal region (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Information section 2.11 and Supplementary Figs. 2_7 and 2_8). These ADMIXTURE patterns align with the fineSTRUCTURE results, indicating a greater genetic contribution from eastern and northern Asia in Mokp than in all but one historical Yakut (Omouk1; Fig. 2c). Combined, these analyses suggest that Yakuts from approximately 1500 ce onwards were not genetically continuous with the populations inhabiting Yakutia until approximately 280 bce (the radiocarbon age of Mokp).

The stage 4 Omouk1 female was a clear genetic outlier relative to the historical and modern Yakuts in the PCA (Fig. 2a). She also exhibited increased Asian haplotype sharing (Fig. 2c) and an ADMIXTURE profile resembling that of the modern Trans-Baikal Evenk (Fig. 2b). Notably, the Yakut word ‘omuk’ means ‘Tungus’ or stranger, and the associated archaeological material reflects Tungus (Evenk) reindeer herding traditions16. These findings suggest that Omouk1, while buried in Yakutia, originated from a different genetic and cultural background than other historical and modern Yakuts.

The stage 4 Yakut Omouk3 female also displayed a slightly atypical genetic profile, including increased European haplotype sharing (Fig. 2c). A similar pattern was observed in another stage 4 female (Khoumakhtaakh), a stage 2 female (Haras) and a stage 1 male showing cranial deformation characteristic of Tungus groups (Byljasyk3)16. Using qpAdm23, their genetic makeup was best modelled with a three-way admixture, incorporating an extra western Eurasian source, distinct from the two common to all other Yakuts post-1500 (Supplementary Table 1f,g). This extra ancestry could have represented European genetic input during Russian conquest. However, the estimated admixture date for Haras (718–1373; Supplementary Table 1h) pre-dates Russian expansion, suggesting earlier contact with an already admixed population, possibly from the Trans-Baikal region. The European-like admixture in Khoumakhtaakh and Omouk3 was dated to 1454–1790 (Supplementary Table 1h), aligning with both pre-conquest contacts and the Russian conquest.

Except for rare outliers (Supplementary Table 1f), the genetic makeup of all other stages 1–4 Yakuts could be modelled as a two-way admixture between populations inhabiting Yakutia in the Iron Age and the Baikal region from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries (Baikal_his, 16–38% with Yakutia_IA (62–84%) and Baikal_sib, 40–79% with Yakutia_IA (21–60%); Supplementary Information section 2.12, Supplementary Fig. 2_9 and Supplementary Table 1f). Two-way admixture models involving a Western Russian source (Vologda Administrative Region) and a Baikal source (Baikal_his or Baikal_sib) were infeasible and/or rejected (P ≤ 0.01 and/or admixture proportion estimates ± 2 s.e. fell outside the (0, 1) interval; Supplementary Table 1f). Three-way models including Yakutia_IA, Baikal_his/Baikal_sib and European sources from 11 populations representing four language families, including from Western Russia, proved infeasible or returned negligeable admixture proportions and did not improve statistical fit relative to two-way nested models (Supplementary Table 1f,g).

To further explore the genetic impact of the Russian conquest, we calculated D-statistics23 of the form D(Mbuti, European; Yakut_X, Yakut_Y), where Yakut_X and Yakut_Y represent various combinations of Yakut groups, excluding the previously identified genetic outliers (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Compared with stage 1, neither the groups forming each subsequent stage nor modern Yakuts showed a statistically significant excess of genetic sharedness with Europeans, including Western Russians (Extended Data Fig. 3d). Furthermore, no enrichment was detected in any given archaeological stage relative to earlier stages (Z scores < 3; Extended Data Fig. 3d). Only one of the 100 tested combinations showed a slightly higher Western Russian genetic contribution to modern Yakuts than to stage 2 individuals. Collectively, these analyses indicate a marginal genetic impact of the Russian conquest on the Yakut groups analysed.

The stable and homogeneous genetic composition of historical and modern Yakuts helped refine existing models of their origins. DATES24 estimated the admixture time between the two primary ancestry sources between approximately 1100 and 1250 (using Yakutia_IA + Nganasan and Baikal_sib; see Supplementary Information section 2.12 for the rationale; Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1h). ASCEND analyses25 (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Information section 2.13, Supplementary Fig. 2_10 and Supplementary Table 1i) further suggested that the Yakut population emerged shortly after this admixture (approximately 1210–1400), following a founder event of relatively mild intensity. The associated demographic bottleneck, quantified as the ratio between the bottleneck duration and twice the effective size, was estimated to 3.0–6.4%. Because HAPROH-based26 estimates indicated an already limited effective size throughout stages 1–4 (Ne of approximately 532–721; Supplementary Table 1j), our analyses support a brief bottleneck underlying the foundation of the Yakut population. These findings align with oral tradition and historical sources that depict the origin of the Yakut people in the aftermaths of the Great Mongol Empire expansion from the early thirteenth century6,7.

Oral microbiomes and disease outbreaks

The arrival of Russian settlers introduced new food items, including barley, rye and various beverages10,27, into a diet traditionally dominated by meat and fish. To assess the potential impact of these dietary changes on the oral microbiome, we analysed the taxonomic and functional composition of 78 dental calculi and 55 teeth belonging to 85 Yakuts (Supplementary Table 1a,k). A subset of 74 individuals, spanning stages 1–4, exhibited typical oral microbial profiles with limited environmental contamination (Extended Data Fig. 4a). The most abundant bacterial species identified was Actinomyces dentalis, followed by other species, such as Desulfomicrobium orale, Desulfobulbus oralis and Olsenella sp. oral taxon 80, all known to be prevalent in past oral environments and to contribute to dental biofilms and plaque28 (Supplementary Fig. 2_11).

Taxonomic abundance profiles, determined using MetaPhlAn4 (ref. 29), as well as species-level alpha diversity, did not show significant shifts over the course of the Russian conquest (two-sided Wilcoxon test; P ≥ 0.66; Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 4b). Similarly, the diversity of functional pathways, assessed through HUMAnN 3.0 (ref. 30), UniRef90 (ref. 31) and ChocoPhlAn32, remained stable throughout the entire period (Fig. 3b). Both principal coordinate analyses (PCoA) and PCA, along with network-based clustering (Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_14), revealed global overlap in taxonomic and functional diversity across archaeological stages. This stability was further supported by statistical tests, including analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) (Supplementary Table 1v) and multivariate analysis of variance (adonis2; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v), both rejecting greater similarity within archaeological stages than between them (0.55 ≤ P ≤ 0.89). Shifting focus to metabolic pathways to improve resolution, no statistically significant changes were observed in the abundance profiles of carbohydrate and amino acid metabolic pathways (Kruskal–Wallis test; P ≥ 0.067; Fig. 3c, Supplementary Information section 2.16 and Supplementary Fig. 2_18). Restricting all the above analyses on the subset of 66 dental calculi did not alter the conclusions (Supplementary Information sections 2.14 and 2.16, Supplementary Figs. 2_13 and 2_19 and Supplementary Table 1m). Combined, these results depict a striking stability in oral microbiomes between approximately 1500 and 1900, despite the dietary changes introduced by the Russian conquest10.

a, PCoA of 74 oral samples carried out on Aitchison distances calculated on high-quality counts for 719 unique taxonomic species (abundance greater than 1%) from the MetaPhlAn4 database29. b, PCA of 65 oral samples performed on the abundance of 303 functional pathways after a centred log-ratio transformation. c, Relative abundance of the pathways underlying carbohydrate metabolism (for details on pathways, see Supplementary Fig. 2_18). d, Relative species abundance of five bacterial complexes and five oral pathogens (for details on each species from these complexes, see Supplementary Fig. 2_12). Similar analyses are provided in Extended Data Fig. 4c for three other pathogens. Box plots represent the 25%, 50% and 75% quantiles, with upper and lower whiskers showing values within the 1.5 interquartile range. The horizontal black segment indicates the mean value for each species at each stage. e, Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of the two Yakut smallpox strains (red labels). Node supports are on the basis of 1,000 ultrafast bootstraps. Scale bar, 0.01.

a, Kinship network obtained from two analyses (cases in which both analyses disagree are shown reporting both corresponding relationships). Mitochondrial and Y-chromosome haplogroups are colour-coded and represented by symbols on the right and left sides of each individual. Family groups (with first-degree and second-degree relationships) are circled and named. b, Heat map of P values for tests of dissimilarity between DNA-based or material-based (rows) and non-genetic (columns) factors. Grey means that the test was not performed because cultural categories have been defined on the material culture. c, Proportion of long and short run of homozygosity (ROH) and inbreeding coefficient. d, Key elements of material culture excavated together with the individual UsSergue1. From top to bottom and left to right: wood comb; ushanka with a bronze solar disk worn by the deceased; choron, traditional pot for drinking fermented mare’s milk deposed between the coffin and the chest; pendants fixing together the short and virgin belt worn by the deceased; bronze stirrup; bridle, snaffle bit and bell representing burial offerings; saddle; picture of the skull of the deceased, adorned with her jewellery.

A previous study reported a shift in carbohydrate consumption during the Russian conquest33, from pine sapwood flour (dendrophagy) to barley and rye, alongside increased risks of dental infection linked to smoking, particularly in stage 4 (ref. 10). We investigated whether these changes affected oral health by analysing the abundance of five bacterial complexes involved in biofilm formation and periodontal disease34 and eight oral pathogens (Supplementary Information section 2.14). Our analyses revealed no significant increase in abundance levels from stages 1 to 4 (Kruskal–Wallis test; P ≥ 0.053; Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 2_12). Additionally, strain-level analysis of six oral pathogens or abundant oral species, which offer improved resolution into the oral health of ancient individuals relative to bacterial complexes35, indicated different strains circulating in Yakutia and the rest of the world, as well as no shifts during the Russian conquest (Supplementary Information section 2.15 and Supplementary Figs. 2_15–2_17). These findings indicate that oral health remained largely unchanged during this period, consistent with the low prevalence of dental cavities observed archaeologically27.

However, our data revealed the presence of smallpox in three stage 2 individuals from Central Yakutia (AC1S2, AC1S3 and Rassoloda; Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 2b, Supplementary Information section 2.17 and Supplementary Fig. 2_20), one of whom previously reported polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive for smallpox12. Sequence data were derived from permafrost-preserved lung and bone tissues, as well as teeth and dental calculi (Supplementary Table 1p), although only limited portions of the smallpox genome could be characterized (average depths of coverage of 0.12-fold and 0.15-fold for AC1S2 and Rassoloda, respectively). Maximum likelihood phylogenetic reconstruction indicated that the virus belonged to a strain distinct from those previously identified in Scandinavian and western Russian individuals from the seventh to tenth centuries36 and the two main clusters responsible for the twentieth-century outbreaks worldwide (VARV-PI and VARV P-II; Fig. 3e and Supplementary Table 1q). Topological tests rejected clustering with the VD21 strain previously detected in a seventeenth-century female from Lithuania37, supporting a deeper phylogenetic placement (Supplementary Information section 2.18 and Supplementary Figs. 2_21 and 2_22). This suggests that different smallpox strains existed in Eurasia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Social life of past Yakut communities

Historical and ethnographic sources describe Yakut communities as structured around patrilineal and patrilocal clans, with strict exogamy38. Mitochondrial diversity was high across stages 1–4, whereas the number of Y-chromosomal haplotypes remained markedly limited (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the proportion of long identity-by-descent (IBD) segments (greater than 12 cM) in pairs of same-sex adults buried in different regions was significantly greater among males than females (Wilcoxon test; P < 0.0001; Extended Data Fig. 5a). These findings are consistent with the expectations of patrilocal clans practicing exogamy, although we caution that the predominance of males in the sampled assemblages may enhance the detection of genetic relatedness among males.

Kinship analyses identified 61 individuals genetically related up to the third degree, including four cases of first-degree and second-degree relatives buried at the same site (AtDaban, Oktiom, Oulakh and Arbre Chamanique, which translates to ‘shamanic tree’ in English; Fig. 4a, Supplementary Information section 2.8 and Supplementary Table 1r–t). At Oulakh, three adult males, all first-degree relatives, were buried within a few metres of one another, and at AtDaban, a father and his adult son were buried together (Extended Data Fig. 5b), consistent with patrilocal practices. However, a grandmother was buried with her daughter and two grandchildren at Arbre Chamanique (Extended Data Fig. 5b), whereas at Oktiom, a juvenile male was buried alongside his sister’s children and their father (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Although these findings suggest non-strict patrilocal practices, the funerary context of the latter two sites is unique across Yakutia16. It shows individuals deposited simultaneously, which is indicative of a catastrophic event, such as the smallpox outbreak that decimated people buried at Arbre Chamanique (AC1S2 and AC1S3). Further research, incorporating genetic analyses of large-scale funerary sites that represent entire communities, alongside denser sampling across broader geographic regions, is needed to assess the prevalence of patrilocal residence patterns.

In the present dataset, exogamy was primarily restricted to individuals within the same geographic region because no first-degree or second-degree relatives were identified across different regions (Fig. 4a). Accordingly, IBD segment sharing was stronger within pairs of individuals buried in the same region compared with those buried in different regions (t-test; P < 0.0001; Extended Data Fig. 5c). The number of inter-regional third-degree relationships was also markedly lower than expected under panmixia (χ2 test; P < 2.2 × 10−16). Furthermore, analysis of allele-sharing dissimilarity (ASD), microbiome composition and DNA methylation profiles, although from a limited subset of samples, revealed significant regional clustering (adonis2 non-parametric permutational multivariate analyses of variance; P = 0.0002, 0.0045 and 0.0037, respectively; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v). Combined, these results indicate that unions, interactions and microbial exchanges occurred primarily within regional boundaries. Although the current sample size and geographic range are limited relative to the vast expanse of Yakutia, this pattern contrasts with the prevailing archaeological interpretation, which proposed, on the basis of the same assemblages, that extensive migration between regions was responsible for the striking similarities in the material culture15.

Changes in ASD, pairwise distances on the basis of microbial communities and functional pathways, and DNA methylation (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Figs. 2_23–2_27) showed no statistical association with archaeological stages, which aligns with the observed stability of the Yakut gene pool and microbiome profiles over time. Although material culture linked to males and females was clearly distinct (adonis2; P = 0.0001; Fig. 4b, Supplementary Information section 2.20, Supplementary Fig. 2_28 and Supplementary Table 1v), sex did not significantly influence the similarity measured between genomes, methylomes or microbiomes (adonis2; P ≥ 0.15; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v). The latter aligns with stable isotope analyses, which reflect no dietary differences between males and females4. Furthermore, no associations were found between economic wealth, leadership, Christianity or shamanism and biological distances, whether estimated by genetic proximity, inbreeding or microbiomes (adonis2; P ≥ 0.14; Fig. 4b). This suggests that individuals with similar social and spiritual statuses were not necessarily biologically closer than those with different statuses. The lack of association between methylomes and socio-economic factors, such as wealth and leadership, further suggests that current approaches for reconstructing ancient methylomes provide limited resolution into past socio-economic status. Finally, the significant association between genetic distances and regional affiliation, but not with indicators of leadership, suggests that political power was not concentrated in a single clan.

Archaeological evidence of shamanic practices was found within close kin groups (AC1S2 and ACS3; Fig. 4a). However, shamanism was not associated with pairs of individuals close genetically (Pearson’s χ2 test; P = 0.33; Fig. 4b), indicating that the practice was not confined to a single genetic familial clan. Although historical inbreeding levels were low (Supplementary Information section 2.9), the most inbred Yakut (UsSergue1; Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 2_4) also happened to be the last individual excavated with clear markers of traditional shamanism14,16 (Fig. 4d). She was genetically identified as the great-granddaughter of AtDaban6, who was married to Bozekov, the most prominent clan leader from the late seventeenth/early eighteenth centuries39. Her high inbreeding level suggests mating between second-degree relatives. However, it seems unlikely that UsSergue1 had access to shamanism because she was the offspring of exceptionally close kins, whereas the female buried with the most extensive collection of shamanic artefacts (KyysOunouoga)16 showed no evidence of consanguinity (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

Our study clarifies the genetic origins of the Yakut people; the complex interplay between their marital, funerary and spiritual practices; and the extent to which these aspects were altered by the Russian conquest.

First, we found that the Yakut gene pool emerged through an admixture between a local population with roots in the Iron Age and another group probably from the Trans-Baikal region, which entered the area during the expansion of the Great Mongol Empire in the early thirteenth century6,7. This timeline, along with the broad connection with the Baikal region, concurs with oral traditions about their origins3. However, the persistence of a substantial local genetic component contrasts with cultural and linguistic evidence pointing to a predominant central Asian Turkic–Mongol influence7. We note, however, that the estimated contribution from the local population varies depending on the Baikal source considered, underscoring the need for denser sampling across the region and time period. Current models rely on population sources defined by a limited number of genetically characterized individuals, which probably do not capture the full extent of genetic diversity across the vast territory of Yakutia at the time of admixture. Despite these limitations, our results indicate that the Yakut history represents a fusion of a local population with a migrating group, both genetically and culturally.

Our analyses also improved previous studies on the basis of uniparental markers indicative of a founder event40,41 by showing that the demographic bottleneck preceding the Yakut expansion was rapid, occurring shortly after admixture, by no later than 1400. The earliest Yakut sequenced in our study (Atlasovka), buried by the late fifteenth/early sixteenth century, appeared to be a key ancestor in the reconstructed kinship networks, further supporting her foundational role42. Additionally, kinship analysis revealed that although first-degree and second-degree relatives could be buried at the same archaeological site, they were primarily found in geographically close locations, within a maximum of 159 km from one another (median distance of 45 m). This strong genetic proximity among burials from the same area remained evident even when close kins were excluded. Combined, these findings emphasize the deep-rooted connection between the Yakuts and the land of their fathers and grandfathers.

Furthermore, our genetic data revealed exceptions to patrilocality, and, despite the small effective population size, consanguinity remained limited. Although further research is required to assess how common such practices were, social norms allowed for close-kin unions, as shown by the UsSergue1 female, identified as the daughter of second-degree relatives. Crucially, she was buried with some funerary objects atypical of the late eighteenth century, reminiscent of the earliest Yakut material culture16,43. This female was the most recent bearer of traditional shamanic artefacts excavated. She was buried in one of the richest tombs identified and descended from the wealthiest clan documented39. Because she died right when Christian belief began to gain influence in Yakut society, she may be seen as an embodiment of a clan’s attempts to preserve its cultural and spiritual traditions.

Finally, the Russian conquest was found to have had marginal genetic impact on the Yakut population, at least within the time periods and regions investigated in this study. Because the Yakuts traditionally deposited their dead on open platforms rather than burying them, the extent of Russian admixture within the broader population not represented archaeologically remains unknown. However, we note that the individuals buried span a wide range of economic and social statuses, from small group leaders, shamans and suicides to major clan leaders, suggesting minimal sampling bias. Although the extent of Russian admixture in Christian cemeteries is also uncharacterized, the Yakut genetic pool appears stable throughout all archaeological stages and into the present day, indicating limited admixture during Russian conquest. Therefore, our study portrays Yakutia as a middle ground44, where Yakuts and Russians engaged in an economic partnership rather than a site of military or demographic conquest. Historical sources highlight Yakut peoples as pivotal to the success of the then-expanding fur trade11, which not only motivated Russian conquest1,9 but also provided prominent Yakut clans with opportunities for considerable wealth and power39. Additionally, the harsh environment, often lethal to European settlers and unsuitable for large-scale cereal agriculture, prevented the establishment of large Russian settlements (Supplementary Information section 1.1 and Supplementary Fig. 1_1). Consequently, the Russian expansion in Yakutia relied heavily on local populations, representing a form of colonialism distinct from the settler colonialism of the Americas, which proceeded through Indigenous displacement and eradication45. It also diverged from the indirect rule characteristic of colonial India, where colonial authority was maintained through local leaders without administrating the territory. By contrast, Russian authorities imposed their tax systems on Yakut communities and co-opted Yakut elites by granting them citizenship and incorporating them into the imperial structure, fundamentally altering traditional Yakut political and social organization while making them subjects of a foreign empire.

Despite the absence of significant genetic impact, Russian conquest profoundly affected Yakut livelihoods and demographics. Russian contact introduced numerous infectious agents, including the smallpox identified here and Mycobacterium tuberculosis13, with devastating demographic effects on immunologically naive Indigenous populations. The severe outbreaks documented in historical sources were not detected in hapROH, indicating limited but stable and effective population sizes. This probably reflects the extremely rapid progression of these outbreaks or other factors limiting detection power. Although dietary shifts are well-documented10,27, our study failed to identify changes in the taxonomic and functional diversity of the Yakut oral microbiome. This contrasts with earlier studies that reported major changes in Neolithic Europe, alongside a dramatic increase in carbohydrate consumption46. Our findings also conflict with oral microbiome shifts documented in Great Britain (2200 bce–1853 ce), which have been linked to lifestyle, hygiene and dietary changes, including increased dairy and carbohydrate consumption47. The consistency of the Yakut oral microbiome over the short microevolutionary timescale investigated here (approximately 1500–1922) may reflect a shift in the carbohydrate types consumed (from wood-based flour to cereal flour)33 rather than a drastically increased intake. Moreover, our findings are in agreement with other studies reporting stable oral microbiomes over deep phylogenetic scales, including between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans48, and during the Neolithic transition from hunting and foraging to farming49. Future research is needed to understand the drivers of oral microbiome composition and function; the true capacity of dental calculus to capture these dynamics; and the broader response of the digestive microbiome to lifestyle, diet and health.

The exceptional archaeological record preserved in the Yakut permafrost provided a unique opportunity to reconcile evidence from material culture with the full spectrum of ancient DNA analysis, shedding light on population origins, social practices, health and individual status. In doing so, it contributed to the growing body of ancient DNA research aimed at capturing the multigenerational life of ancient communities.

Methods

Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating of the Mokp individual (UCIAMS210906: 2205 ± 20 BP, 364–197 International Radiocarbon Calibration Curve (2020 version, IntCal20) calibrated years bce) was carried out at the Keck Laboratory, University of California, Irvine, following the methodology described by Librado et al.50.

Sex and age-at-death estimations of the human remains

Age-at-death determination methods rely on a variety of skeletal indicators, including stages of auricular surface for adults51,52, stages of iliac crest or sternal end of the clavicle fusion, measurement of long bones for immature individuals53,54 and dental eruption sequences55,56. Biological sex is on the basis of genetic data, especially the so-called Ry ratio (Y to Y + X sequence coverage)57 (Supplementary Table 1a).

DNA extraction

Samples were processed in the clean laboratory facilities at the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse (CAGT), University of Toulouse, or at the Centre for GeoGenetics (CGG), University of Copenhagen, following ancient DNA procedures (Supplementary Information section 2.2).

Bone and tooth samples

After gentle surface abrasion, a portion of the dense part of the bone samples was collected using a diamond wheel (PROXXON or ARGOFILE instruments). For tooth samples, the cementum was isolated as recommended by Damgaard et al.58. The samples were either crushed into smaller fragments using a manual mortar or cutting pliers, or pulverized using a Retsch MM200 instrument and then placed in 5-ml Eppendorf LoBind tubes. DNA was extracted following a silica-column-based method, as described by Librado et al.59, without bleach pretreatment (Supplementary Information section 2.2).

Calculus samples

Calculus samples were isolated, as described by Sabin and Yates60. Samples labelled as ‘Name_C’ in Extended Data Fig. 4a (for example, Eletchei3_C_C_P4) were extracted for DNA following a protocol similar to that used for bones and cementum, except that no 1-h predigestion was performed and the digestion volume was limited to 1 ml. Samples labelled as ‘Name_CE’ (for example, Eletchei3_CE_C_P4) were subjected to an overnight digestion at 50 °C in 555 µl of a buffer consisting of 0.45 M EDTA, 1.8 mg ml−1 of proteinase K and 9 mM dithiothreitol. The supernatant was further purified on a QIAGEN MinElute column and eluted in 40-µl sterile water.

Soft tissue samples

Fragments of soft tissues (lung and muscle) were digested in 1.11 ml of a buffer containing 0.45 M EDTA, 1.8 mg ml−1 of proteinase K and 9 mM dithiothreitol, following an overnight incubation at 50 °C with agitation. After 12 min of centrifugation at 8,000 rpm, the supernatant was collected and purified on a silica column (MinElute; QIAGEN; 40-µl sterile water elution).

USER treatment, DNA library building and indexing

An aliquot of 22.8 µl of each DNA extract was incubated with 7-µl USER Enzyme mix (New England Biolabs) for 3 h at 37 °C to limit the impact of post-mortem cytosine deamination in downstream analyses by removing uracil residues. For a few samples, another DNA extract aliquot was also directly converted into a sequencing library.

Sequencing libraries were constructed from double-stranded DNA molecules by ligation of universal (method by Gamba et al.61, adapted from Meyer and Kircher62) or indexed63 blunt-end adaptors. To determine the optimal number of PCR cycles for amplifying DNA libraries and obtaining sufficient material for Illumina sequencing, quantitative real-time PCR was performed on 20X dilution aliquots of most of the libraries. The libraries were amplified for 5–15 cycles using AccuPrime Pfx DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with 3.5–6.5 µl of unamplified DNA library and 0.2 mM of each PCR primer in a total reaction volume of 50 µl. One primer of each pair contained an external 6-bp index, read during the Illumina Indexing Read. To limit the proportion of PCR duplicates, up to six independent amplifications were carried out for most DNA libraries. The PCR products were subsequently purified using either MinElute columns (QIAGEN) or AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), eluted in 20 µl or 25 µl of elution buffer (EB) supplemented with 0.05% Tween and quantified on TapeStation 2100/4200 or Bioanalyzer instruments (Agilent Technologies) and Qubit HS Assay (Invitrogen).

Sequencing

DNA library pools were sequenced at CAGT on the Illumina MiniSeq instrument; at CGG on Illumina NextSeq, HiSeq2000, HiSeq2500 and HiSeq4000 instruments; or at Centre National de Recherche en Génomique Humaine on the Illumina HiSeq X instrument. The vast majority of the sequencing data consisted of paired-end reads.

Reads preprocessing

The demultiplexed FASTQ paired reads were processed using PALEOMIX64 bam_pipeline (v.1.2). Sequencing adaptors were trimmed (-mm 5) as well as poor-quality end, and paired-end reads were collapsed using AdapterRemoval 2 (v.2.3.1; ref. 65). All the resulting reads and those remaining paired were mapped against the hs37d5 reference genome using Bowtie 2 (ref. 66) with local sensitive mapping parameters. The binary alignment/map (BAM) alignment file was further filtered for alignment size superior or equal to 25 bp and mapping quality superior to 30. PCR duplicates were removed using Picard MarkDuplicates (http://picard.sourceforge.net), and realignment around indels was performed using GATK67. Sequencing statistics, as numbers of sequencing reads, endogenous DNA content and coverage are provided in Supplementary Table 1a,b.

All resulting alignments were merged into a single BAM file before pseudo-haploidization, with one read randomly sampled at positions characterized by one or more alignments. Pseudo-haploid genotypes were called using ANGSD (v.0.930; ref. 68) (htslib: 1.9), skipping positions and/or reads showing base and/or mapping Phred quality scores strictly lower than 30 (--doHaploCall 1 -doCounts 1 -minMapQ 30 -minQ 30 -remove_bads 1 -uniqueOnly 1) and restricting calls for those 1,233,013 SNP positions forming the 1240K panel18.

Post-mortem damage and error rates

DNA fragmentation and nucleotide misincorporation patterns were visualized using mapDamage2 (v.2.0.8; ref. 69), with default parameters on a subset of 100,000 random reads. All damage profiles and base compositions were aligned with expected profiles, with or without USER treatment of DNA extracts70.

Error rates were calculated using ANGSD68 and the methodology used in a previous study71 (Supplementary Information section 2.4). Overall, the global error rates of each individual genome characterized in this study ranged between 0.000262 and 0.002819 substitutions per base on average, mostly inflated through transition misincorporations (Supplementary Table 1b).

Uniparental markers, contamination estimates and ploidy check

A total of 46 women and 61 men were identified on the basis of Ry ratio (Supplementary Table 1a). Mitochondrial haplotypes were called using Haplogrep (v.2.266; ref. 72) after aligning reads against the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence reference mitogenome (GenBank accession no. NC_120920.1) and discarding those shorter than 25 bp, with mapping and base qualities below 30 (Supplementary Information section 2.5). The resulting variant call format file was then processed through Haplogrep72, calculating the best 100 hits. Contamination rates on the basis of mitochondrial data were estimated using schmutzi73 and the same base quality threshold as above. Nuclear contamination rates were estimated for male individuals, following the methodology by Rasmussen et al.74 and implemented in ANGSD68. Transition substitutions and sites covered once or more than 200 times were discarded.

Mitochondrial contamination estimates were assessed within a 0–5% confidence range for all individuals but three (Supplementary Information section 2.5 and Supplementary Table 1a), which were conservatively excluded from those analyses conditioned on archaeological stages. Nuclear contamination estimates were found to be limited (median of 0.24%) and inferior to 0.4% (Supplementary Table 1a). Y-chromosome haplotypes were called using the Yleaf statistical package75 (Supplementary Information section 2.5). The ploidy levels of each individual were checked following the methodology described by Sehnert et al.76 (Supplementary Information section 2.6 and Supplementary Fig. 2_3).

Imputation

We imputed a subset of genomes using GLIMPSE2 (ref. 77) and the 1000G19 panel as reference dataset, following the instructions provided by the developers on the software website. To test for the minimal coverage needed to obtain accurate imputation, we downsampled the data of four high-coverage individuals, imputed the resulting genotypes and then assessed imputation accuracy by measuring the squared Pearson correlation between original and imputed genotypes (Supplementary Information section 2.7). We found that a minimal coverage of 0.35-fold was necessary for imputing genotypes represented at MAF of 5% or higher. A total of 90 Yakut individuals (coverage of 0.35-fold or higher) were then imputed and filtered for MAF of 5% or higher and genotype probability of 0.99 or higher for all downstream analyses. The imputed individuals were combined with the phased 1000G dataset for all downstream analyses, except for those on the basis of fineSTRUCTURE21, which required a liftover to the hg38 positions to include the matrix of phased genotypes released by Bergström et al.78, which included 20 modern Yakut individuals.

Kinship analyses

Relatedness between historical Yakuts was assessed on the basis of the pseudo-haploid data using a combination of three complementary methodologies: READ2 (refs. 79,80), lcMLkin81 and TKGWV2 (ref. 82) (Supplementary Information section 2.8 and Supplementary Table 1r–t). For READ2 (refs. 80,81) and TKGWV2 (ref. 82), the autosomal positions overlapping the 1240K dataset were used, restricting the former to MAF of 1% or higher. We disregarded first-degree and second-degree relationships if estimated from less than 1,000 and 2,000 SNPs, respectively, whereas the default filter of READ2 (refs. 79,80) was used for assessing third-degree relationships. Precise genealogies were reconstructed using the READ2 (refs. 79,80) results, age-at-death estimations, uniparental markers and estimated period of burial of each individual (Extended Data Fig. 5b and Supplementary Information section 2.8).

Identity-by-descent (IBD) contents were calculated using ancIBD83 on the direct output of GLIMPSE2 without MAF and genotype probability filters. As recommended, the Yakut dataset was downsampled to 1,240,000 SNPs, for which ancIBD was optimized, and IBD sharing was screened for every pair of imputed individuals (coverage of 0.35-fold or higher), with default settings83. For population analyses, individuals with the least SNPs covered in each pair of first-degree or second-degree relatives were removed.

Inbreeding and diversity estimates

The effective population sizes for each stage and region were estimated on the 1240K SNP pseudo-haploid panel, restricted to individuals with at least 400,000 SNPs covered, using hapROH26 with default parameters and 5,008 haplotypes from the 1000G project as a reference panel (Supplementary Table 1j). For each archaeological stage, PCA individual outliers were removed.

ROH were identified on the imputed dataset using plink84 (--homozyg) on set of 1000G biallelic transversions with MAF higher than 5%, removing any positions not fully covered (--geno 0). Inbreeding scores were calculated with plink84 (--het) using transversions only and MAF of 5% or higher (Supplementary Information section 2.9 and Supplementary Table 1a). To further confirm our results, we performed ROH detection using hapROH26 on the pseudo-haploid data for individuals with at least 400,000 SNPs covered on the 1240K panel (Supplementary Information section 2.9 and Supplementary Fig. 2_4).

Principal component analysis

PCA was carried out using the Human Origins reference panel for 597,573 autosomal genotypes. Genotypes were downloaded from the Allen Ancient DNA Resource (v.5) website18. We also included the genotypes from those Central Asian individuals with relevant genetic ancestry profiles reported by Zhang et al.85. PCA was on the basis of pseudo-haploid genotype calls for all the individuals presented in this study and carried out using smartPCA from EIGENSOFT (v.7.2.170; ref. 86), projecting 913 ancient Eurasian and American individuals and 106 ancient Yakut individuals (coverage of higher than 0.02-fold) onto the principal components obtained from in 2,761 Eurasian modern individuals (lsqproject, YES; shrinkmode, YES; Supplementary Information section 2.10 and Supplementary Fig. 2_5, where a non-projected PCA is shown). Projections on the first two principal components are provided in Fig. 2a, whereas PC2 and PC3 are provided in Extended Data Fig. 3b. A second PCA was carried out to validate our imputation pipeline by confirming similar projections for imputed genotype data and pseudo-haploid data (Supplementary Information section 2.10 and Supplementary Fig. 2_6).

ADMIXTURE

Unsupervised ADMIXTURE (v.1.3.0; ref. 20) analyses were carried out to estimate the proportions of genetic ancestries present in Yakuts (coverage of 0.03-fold or higher; pseudo-haploid) using autosomal positions as part of the 1240K Human Origins panel and a total of 3,639 Eurasian and American individuals. Sites were thinned for linkage disequilibrium with plink84 (--indep-pairwise 200 25 0.4), resulting in a total of 327,582 SNPs. Confidence intervals were estimated from 100 bootstrap pseudo-replicates. Analyses were repeated ten times using ten random seeds to assess convergence (Supplementary Information section 2.11 and Supplementary Fig. 2_7). Full ancestry profiles are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2_8 for the entire dataset.

FineSTRUCTURE

A fineSTRUCTURE (v.2; ref. 21) analysis was performed on the imputed data to explore patterns of haplotype sharedness. Imputed transversion genotypes were converted to hg38 positions with the tool LiftoverVcf from the Picard Toolkit 2019 (https://github.com/broadinstitute/picard), and related individuals were removed before merging with the phased genotypes from Bergström et al.78. The genotype positions showing missingness in at least one individual were removed, and MAF of 1% or higher was required, resulting in 1,059,615 autosomal sites. The merged dataset was split by chromosome, rephased using SHAPEIT (v.2; ref. 87) and transformed into ChromoPainter (v.2; ref. 21) format using ‘impute2chromopainter.pl’ and a chromosome-based recombination map generated through the ‘makeuniformrecfile.pl’ script. ChromoPainter (v.2; ref. 21) analyses were on the basis of 20 expectation–maximization iterations (-s1emits 20 -in -iM), with a starting switch rate of 250 (-n 250) and a global mutation rate of 0.0005 (-M 0.0005). The fineSTRUCTURE Markov chain Monte Carlo model was run on the ChromoPainter (v.2) output for 3,000,000 burn-in iterations and 2,000,0000 sampling iterations with no thinning (-s3iters 5000000 -s3iterssample 2000000 -s3itersburnin 3000000). The resulting co-ancestry matrix is shown in Extended Data Fig. 3c.

D-statistics

Different combinations of D-statistics were calculated using qpDstat in ADMIXTOOLS (v.5.056; ref. 23) to detect gene flow by testing whether pairs of modern and ancient Yakuts from each archaeological stage were symmetrically related to modern Eurasian populations. Calculations were carried out on the pseudo-haploid 1240K dataset using Mbuti (N = 10; ref. 78) as outgroup. The topologies investigated were in the form of (outgroup, Eurasian modern populations; StageX, StageY/modern Yakut). The results of the different D-statistics calculations, with Z scores corrected for multiple testing (Benjamini–Hochberg), are provided in Extended Data Fig. 3d, permuting StageX and StageY among the four archaeological stages and modern Yakuts. Positive values indicate closer genetic proximity between the modern Eurasian population and StageY (or modern Yakuts), relative to StageX.

Admixture modelling and dating

Admixture models for ancient Yakut individuals (coverage of 0.1-fold or higher) were assessed using the pseudo-haploid 1240K dataset and qpAdm from ADMIXTOOLS (v.5.056; ref. 23), applying the feasibility criteria recommended by Flegontova et al.88, that is, coefficient ± 2 s.e. within the [0, 1] interval (P ≥ 0.01). The qpAdm models were aimed at testing whether the Yakut genomic makeup was compatible with a two-way admixture from a local Siberian background (Yakutia_IA, N = 2, comprising Mokp and yak03041 because they showed similar genetic profiles and PCA placements) and another source, potentially from the Baikal region (Baikal_his (N = 4) or Baikal_sib (N = 11)) or Russia (Russian78) (Supplementary Table 1f). Baikal sources were defined as Baikal_sib (N = 11) and Baikal_his (N = 4). The former included Mongolia_Khuvsgul_LateMedieval89 (N = 2), Mongolia_Dornod_LateMedieval89 (N = 7) and Mongolia_Khentii_LateMedieval89 individuals (N = 2), whereas the latter comprised Russia_AngaraRiver_Medieval.SG22 (N = 1), Mongolia_Sukhbaatar_Xiongnu (N = 1) and Mongolia_Khuvsgul_MLBALateMedieval89 individuals (N = 2). A full range of qpAdm admixture models were tested to identify the best sources for Baikal_his and the best western Russian source, including Yakutia_IA, Russia_AngaraRiver_Medieval.SG22 (N = 1), Mongolia_Sukhbaatar_Xiongnu (N = 1), Mongolia_Khuvsgul_MLBALateMedieval89 individuals (N = 2) and Buryat.SG90,91 (N = 4), and extending western sources to Polish, Bulgarian, Czech in addition to Russian (accounting for Slavic-speaking populations), Adygei, Abkhasian, Chechen, Lezgin and North Ossetian groups (accounting for the North Caucasus), Mansi (to represent Uralian-speaking populations) and Altaian (Turko–Mongolic-speaking populations) (Supplementary Information section 2.12 and Supplementary Table 1g). This resulted in the exclusion of Buryat.SG from the Baikal_his group because almost all of its models failed, whereas the other groups tested yielded consistent results. No other western sources outperformed the Russian group; therefore, we kept it as a proxy for the western source for the final models (Supplementary Information section 2.12 and Supplementary Table 1g). The Baikal_sib populations were selected because they exhibited the closest ADMIXTURE20 ancestry profiles (Supplementary Information section 2.11). Each ancient and modern individual from Yakutia was tested for every combination of two or three populations, putting the non-used population in the right group92 (Supplementary Table 1f).

We further applied DATES24, using both the pseudo-haploid and imputed datasets, to two-way models to estimate the time of the admixture event between the local ancestry source (Yakutia_IA + Nganasan) and Baikal populations (Supplementary Information section 2.12 and Supplementary Table 1h). Because the confidence intervals using the Baikal_sib source were more restrained (Supplementary Table 1h) and Baikal_sib covered more individuals, analyses incorporating the Baikal_sib source were preferred (Fig. 3d). The time of admixture between a Russian source78 and either a historical Yakut ancestry source (Yakut_his, comprising all newly sequenced Yakut individuals from the four stages, excluding related individuals and genetic outliers; N = 92) or the local ancestry source (Nganasan + Yakut_IA; N = 37) was also estimated for the imputed genomes of the PCA genetic outliers (Supplementary Table 1h). The corresponding weighted linkage disequilibrium decay curves are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2_9 and discussed in Supplementary Information section 2.12).

Bottleneck dating

We used ASCEND25 to assess the intensity and estimate the time for the bottleneck underlying the foundation of the Yakut gene pool. These analyses were first run without specifying an outgroup and then repeated by choosing an outgroup (N = 15) randomly from the populations present in our dataset. Analyses were carried out by considering archaeological stages individually or the entire group of ancient Yakuts, both for the pseudo-haploid and imputed datasets, with the following parameters: binsize, 0.001; mindis, 0.001; maxdis, 0.3; maxpropsharingmissing, 1; minmaf, 0; usefft, YES; qbins, 100 (Supplementary Information section 2.13 and Supplementary Table 1i). The allele-sharing correlation decay curve together with the fitted exponential model from our outgroup tests are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2_10 and discussed in Supplementary Information section 2.13).

Microbial profiling

Microbial taxonomic profiles were determined for each individual DNA sample, restricting analyses to the fraction of collapsed reads. Reads aligned to the human genome (hg37) and the human mitochondrial genome were filtered out (Supplementary Information section 2.14). Microbial read counts were obtained using MetaPhlAn4 (ref. 29) (Supplementary Table 1l), discarding unclassified and too short reads. We applied a minimal read length filter set to the most frequent read length value (visually checked) minus ten, with strict boundaries set at less than 30 bp and greater than 70 bp (Supplementary Information section 2.14). This procedure was repeated on a panel of known sources (Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Table 1k (for details and references)) that were used to assess the proportion of oral microbes contributing to each ancient DNA library, using SourceTracker2 (ref. 93), conditioning analyses on species level (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Samples showing more than 25% of oral sources were retained for further analyses because such proportions were observed in oral samples previously analysed and identified as authentic48. In cases where both tooth and calculus samples from the same individual passed filters, the profile maximizing oral microbial sources was kept, resulting in a final dataset of 74 individual oral microbiomes.

Bacterial taxa showing abundances lower than 1% were disregarded before carrying out composition visualization (Supplementary Fig. 2_11) and PCoA on the basis of Bray–Curtis distances (Fig. 3a). Species abundances of microbes belonging to different bacterial complexes (red, orange, yellow, green and purple), together with eight known oral pathogens, were measured and tested for potential shifts across archaeological stages (Kruskal–Wallis test; Fig. 3d, Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_12). These analyses were repeated on a dataset restricted to calculus samples (Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_13).

We also performed two complementary analyses to reveal subtle commonalities in the microbial compositions of the different samples that may have remained undetected in PCoA (Supplementary Information section 2.14). The first analysis followed Quagliariello et al.46 and their network and clustering methodology. No association was found in the distribution of individuals among clusters and archaeological stages (Pearson’s χ2 test; P = 0.92; Supplementary Information section 2.14 and Supplementary Fig. 2_14). The second analysis investigated strain-level variation in the oral pathogens detected using StrainPhlAn4 (refs. 29,94), considering the most abundant bacterial species of the red complex and eight pathogens. Metagenomic data from dental calculus of several individuals, including Neanderthal outgroups and Eurasian individuals who lived within the past 500 years (Supplementary Table 1n), were accessed through the AncientMetagenomeDir (v.24.09; ref. 95) repository. These data were processed similarly to Yakut data before running StrainPhlAn4 with default parameters to extract species-specific MetaPhlAn markers. We prepared multi-FASTA alignments combining those markers together across all individuals and reconstructed maximum likelihood phylogenies in IQ-TREE (v.1.6.12; ref. 96) to assess whether or not new strains arrived in Yakutia at a specific archaeological stage (Supplementary Information section 2.15 and Supplementary Figs. 2_15–2_17). The best substitution model was estimated using the Akaike information criterion (-m MFP), and node support was assessed from 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap97 pseudo-replicates (UFBoot) (each bootstrap tree optimized using a hill-climbing nearest-neighbour interchange search; -bb 1000 -bnni). When the number of Neanderthal hits was found too limited to use them to root, the trees were rooted at midpoint.

The sequence data passing the SourceTracker2 filters described above were also subjected to functional analyses using the methodology implemented in HUMAnN 3.0 (ref. 30), with default parameters (Supplementary Table 1o). This step generated per-individual functional profiles on the basis of the UniRef90 (ref. 31) and ChocoPhlAn (January 2023; ref. 32) databases, which were further joined by pathways, normalized by counts per millions and centred log-ratio transformed to deal with compositional values that may arise from specific normalization in sequencing data, before conducting PCA (Fig. 3b). Selected pathways associated with carbohydrate or amino acid metabolism were scrutinized for their relative abundances across individuals and compared by archaeological stages using a Kruskal–Wallis test (P ≥ 0.067; Fig. 3c, Supplementary Information section 2.16 and Supplementary Fig. 2_18). These analyses were repeated on a dataset restricted to calculus samples (Supplementary Information section 2.16 and Supplementary Fig. 2_19).

Pathogen screening

Reads aligned to the human genome (hg37) and the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence mitochondrial genome were filtered out (Supplementary Information section 2.17). The resulting filtered FASTQ files were used for mapping against a selection of reference genomes from candidate pathogens (N = 26; Supplementary Information section 2.17 and Supplementary Fig. 2_20a). This alignment step was carried out using PALEOMIX64 bam_pipeline (v.1.2) and bwa-0.6 (ref. 98) (backtrack; MinQuality, 30; no seed; -n, 0.1), which produced high-quality BAM alignments that were removed for PCR duplicates. The number of aligned reads against each reference genome was counted per sample, together with average read-to-reference edit distances. We considered a sample positive for the presence of any given pathogen as long as a minimal number of 100 high-quality alignments were identified, and the average edit distance was equal to or below 0.01. This conservative approach resulted in the identification of three individuals positive for Variola major, the aetiologic agent of smallpox (AC1S2, AC1S3 and Rassoloda; Supplementary Information section 2.17 and Supplementary Fig. 2_20b).

Smallpox genome analysis

All the sequence data generated for the three smallpox-positive individuals were realigned against the variola virus (VARV) smallpox reference genome (accession no. NC_001611.1), using the same procedure as above, except that the minimum alignment size was restricted to 30 bp instead of 25 bp to maximize potential sequence coverage. Although positive, AC1S3 did not provide a sufficient number of reads (N = 199) to proceed further with the rest of the analyses (Supplementary Table 1p). We next used mapDamage2 (v.2.0.8; ref. 69) with default parameters, and genotypes were called using bcftools (v.1.17; ref. 99) mpileup and call modules, requiring a maximum depth corresponding to the 99.5th percentile of the depth distribution, minimal base and mapping Phred qualities of 30 and considering the genome haploid. Low-quality genotypes (Phred quality score lower than 30), indels and polymorphisms within two base pairs of an indel were removed using the bcftools (v.1.17; ref. 99) filter.

To place the smallpox strains identified in the smallpox phylogenetic tree, we applied the same procedure as above to the raw reads previously published for five ancient samples36,37. Additionally, the FASTA sequence data corresponding to 45 smallpox genomes from the twentieth century previously characterized were downloaded100,101 (Supplementary Table 1q). The multi-FASTA sequence data, corresponding to the 45 modern viral genome, including the reference genome, were further aligned using MAFFT102 and manually corrected wherever appropriate. Gaps were added to the six ancient samples according to the gaps in the reference genome after the alignment procedure, and all FASTA were merged to form a multi-FASTA sequence of 52 viral genomes. Positions in which at least 50% of the sequences were covered were retained for maximum likelihood reconstruction in IQ-TREE (v.1.6.12; ref. 96) (-m MFP). Node support was estimated from 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap97 pseudo-replicates (-bb 1000 -bnni). A tree was also generated using the same procedure as described above, removing the manual correction of the modern genome alignment (Supplementary Information section 2.18 and Supplementary Fig. 2_21). The position of our sample in the tree obtained was then tested against seven alternative tree conformations by running an approximately unbiased topology test103 (Supplementary Information section 2.18 and Supplementary Fig. 2_22).

Ancient DNA methylation values calibration

We used DamMet104 to evaluate DNA methylation levels in the genomes of 21 individuals with coverage greater than 9-fold, as a previous study established that relatively high coverage thresholds were needed to obtain reliable estimates. Overall, we followed the procedure previously described by Liu et al.105 to identify the best combination of parameters for DamMet104 DNA methylation inference (Supplementary Information section 2.19). The average cellular methylation fraction (M) was found to have no impact on correlation levels (Supplementary Information section 2.19, Supplementary Fig. 2_23 and Supplementary Table 1u); hence, a value of 75% was retained. Maximal correlation levels (0.38–0.8) were otherwise obtained for a maximum window size of 1 kb, windows of 25 CpGs and a minimum depth of 400 reads per window. Four individuals presented low correlation scores (Spearman correlation; R2 < 0.55) and were thus disregarded.

Despite encouraging correlation levels, two DNA methylation categories associated with scores of 0 and 1 were under-represented in the remaining samples (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Fig. 2_24a), in line with the work from Liu et al.105. We therefore followed the mitigation procedure developed by those authors to improve ancient DNA methylation inference using approximately 27.2 million CpGs in two modern bones published by Gokhman et al.106 (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Fig. 2_24b).

The validity of the resulting DNA methylation inference was also assessed by checking for the presence of well-established patterns along the genome (CpG islands, exons and introns and CTCF binding site regions), following the method by Hanghøj et al.107 (Supplementary Information section 2.19 and Supplementary Figs. 2_25–2_27). The DNA methylation profile observed for the Otchugoui individual did not align with expectations for CpG islands, exons and introns and CTCF binding regions, and it was therefore disregarded.

Statistical associations between cultural and non-cultural data

We generated a presence–absence matrix summarizing the characteristics of each burial (Supplementary Information section 2.20 and Supplementary Table 1a) and calculated pairwise Bray–Curtis between individuals (Supplementary Information section 2.20 and Supplementary Fig. 2_28). To test whether the distribution of distances calculated between pairs of individuals within categories (sex, region and archaeological stages) was significantly different from random permutations of individuals across categories, we used ANOSIM (anosim from the vegan package108 in R109) and a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (adonis2 from the vegan package108 in R109) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v).

Moreover, we binned individuals into four extra categories defining wealth, leadership, Christianity and shamanism on the basis of the collection of cultural goods found in their burials (Supplementary Information section 2.20). To test whether the similarity of the oral microbiome between groups in these categories was lower than the similarity within each group, we used ANOSIM and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v). These analyses were repeated for taxonomic and functional distances, genetic distances (ASD) and DNA methylation distances (Bray–Curtis; Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1v).

Ethics and inclusion

This study builds upon more than 15 years of archaeological research conducted in Yakutia, Sakha Republic, an autonomous region of the Russian Federation located in northeastern Siberia (Supplementary Information section 1.3). The fieldwork was conducted under the MAFSO programme (French Archeological Mission in Eastern Siberia), a collaboration between French researchers and local Yakut experts, including scholars from North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk. The programme was approved in June 2012 by the Local Committee for Biomedical Ethics of the Federal State Budgetary Institution, known as the Yakut Scientific Center of Complex Medical Problems of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. Throughout the programme, local experts were fully engaged as equal partners, contributing to research design, archaeological excavations, material selection for analysis, community outreach, permit acquisition and critical feedback on analyses and manuscripts. Their contributions are reflected in their co-authorships in this study and 21 scientific articles and reviews published between 2004 and 2021. The research team also implemented a wide array of activities to engage with local communities, including fieldwork and student training, and played an active role in public outreach through documentaries, press interviews, television programs and exhibitions. The programme was supported by several inter-university collaborative research agreements, notably between Université Paul Sabatier, Krasnoyarsk State Medical University and North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk. It also received endorsement from the Institute of Ecology and Evolution at CNRS through the International Associated Laboratory ‘Coevolution Human–Environment in Eastern Siberia’. The programme facilitated extensive community engagement, highlighted by the 2019 exhibition at the Historical Park Rossiya-Moya Istoriya in Yakutsk, which showcased the main archaeological discoveries made under MAFSO.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data (FASTQ files) and aligned BAM files generated in this study have been deposited to European Genome-Phenome Archive (accession no. EGAS50000001329). Ethical authorization for the study was granted in June 2012 for conducting ancient DNA analyses from the Local Committee for Biomedical Ethics of the Federal State Budgetary Institution (‘Yakut Scientific Center of Comprehensive Medical Problems’ of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences). This authorization supports analyses aimed at collecting information on the evolution of bacteria or viruses identified for the period studied (fifteenth to nineteenth centuries), as well as studying the influence of socioecological factors on movement, adaptation and dynamics of ancient populations. Access to the sequence data of the ancient individuals analysed in this study will be granted for investigations filling these objectives. Decisions will be made upon request by the LifeChange Data Access Committee (EGAC50000000713), which overviews data access requests for European Genome-Phenome Archive study under accession no. EGAD50000001903. Any further information required to reanalyse the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contacts upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No original code has been produced. All other software packages used in this study were previously published.

References

Forsyth, J. A History of the Peoples of Siberia. Russia’s North Asian Colony 1581–1990 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992).

Thèves, C. et al. Molecular identification of bacteria by total sequence screening: determining the cause of death in ancient human subjects. PLoS ONE 6, e21733 (2011).

Crubézy, E. & Nikolaeva, D. Vainqueurs Ou Vaincus? [Winners or Losers?] (Odile Jacob, 2017)

Romanova, L. et al. Diet of autochthonous populations in Yakutia using isotopic, ethnographic, historical and archaeological data. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 28, 102022 (2019).

Crubézy, E., Melnichuk, O. & Alexeev, A. Archaelogy genetics and history 15 years of research in Yakutia (2002–2017). Vestn. Arkheologii Antropol. Etnogr. 4, 110–119 (2020).

Alexeev, A. N. Drevniaia Iakutiia. Zheleznyi Vek i Epokha Srednevekov’ia [Ancient Yakutia. The Iron Age and the Middle Ages] (Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch, 1996).

Gogolev, A. Yakuty (Problemy Etnogeneza i Formirovaniya Kul’tury) [The Yakuts (Problems of Ethnogenesis and the Formation of Culture)] (Yakutsk State Univ. Press, 1993).

Ferret, C. Une civilisation du cheval. Les usages de l’équidé, de la steppe à la taïga [A Civilization of the Horse. The Uses of the Equid, from the Steppe to the Taiga] (Belin, 2010).

Fischer, R. H. The Russian Fur Trades, 1500–1700 (Univ. of California Press, 1943).

Macé, M. et al. At the origins of tobacco-smoking and tea consumption in a virgin population (Yakutia, 1650–1900 A.D.): comparison of pharmacological, histological, economic and cultural data. Biology 10, 1–26 (2021).

Monahan, E. The Merchants of Siberia: Trade in Early Modern Eurasia (Cornell Univ. Press, 2016).

Biagini, P. et al. Variola virus in a 300-year-old Siberian mummy. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2057–2059 (2012).

Dabernat, H. et al. Tuberculosis epidemiology and selection in an autochthonous Siberian population from the 16th-19th century. PLoS ONE 9, e89877 (2014).

Crubézy, E. & Alexeev, A. Chamane, Kyys Jeune Fille Des Glaces [Shaman, Kyys Young Girl of the Ice] (Errance, 2007).

Duchesne, S. et al. Frozen graves of Yakutia, a chronological sequence. Vestn. Arkheologii Antropol. Etnogr. 4, 120–130 (2020).

Duchesne, S. et al. Beyond the permafrost: excavated tombs of Eastern Siberia archaeological data from the French-Sakha missions. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15017495 (2025).

Hochstrasser-Petit, C., Romanova, L., Duchesne, S., Melnichuk, O. & Gérard, P. Yakut clothes of the 17th and 18th centuries, archaeology and restitution. Vestn. Arkheologii Antropol. Etnogr. 4, 131–147 (2020).

Mallick, S. et al. The Allen Ancient DNA Resource (AADR) a curated compendium of ancient human genomes. Sci. Data 11, 1–10 (2024).

The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68–74 (2015).