Abstract

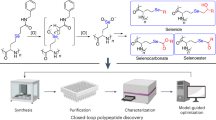

Despite successes in replicating the primary–secondary–tertiary structure hierarchy of protein, it remains elusive to synthetically materialize protein functions that are deeply rooted in their chemical, structural and dynamic heterogeneities1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. We propose that for polymers with backbone chemistries different from that of proteins, programming spatial and temporal projections of sidechains at the segmental level can be effective in replicating protein behaviours13,14; and leveraging the rotational freedom of polymer can mitigate deficiencies in monomeric sequence specificity and achieve behaviour uniformity at the ensemble level2,3,15,16,17,18,19,20. Here, guided by the active site analysis of about 1,300 metalloproteins, we design random heteropolymers (RHPs) as enzyme mimics based on one-pot synthesis. We introduce key monomers as the equivalents of the functional residues of protein and statistically modulate the chemical characteristics of key monomer-containing segments, such as segmental hydrophobicity21. The resultant RHPs form pseudo-active sites that provide key monomers with protein-like microenvironments, co-localize substrates with catalytic or cofactor-binding sidechains and catalyse reactions such as oxidation and cyclization of citronellal with isopulegol/menthoglycol selectivity. This RHP design led to enzyme-like materials that can retain catalytic activity under non-biological conditions, are compatible with scalable processing and have expanded substrate scope, including environmentally long-lasting antibiotic tetracycline22.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. For reproduction purpose, the raw data used to generate the figures are available from the Dryad Digital Repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.ghx3ffc2r).

Code availability

Source codes for metalloprotein surface analysis and sample data are available at GitHub (https://github.com/TingXuGroup/Surface-Anaysis). Source codes for RHP sequence simulation and principal component analysis24 have been previously published and are available at GitHub (https://github.com/ivanjayapurna/RHPapp and https://github.com/Shunili/AE-RHP, respectively). Each repository includes a ‘readme.txt’ file with instructions for using the code.

References

Breslow, R. Artificial enzymes. Science 218, 532–537 (1982).

DeGrado, W. F., Wasserman, Z. R. & Lear, J. D. Protein design, a minimalist approach. Science 243, 622–628 (1989).

Kuhlman, B. et al. Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy. Science 302, 1364–1368 (2003).

Castriciano, M. A., Romeo, A., Baratto, M. C., Pogni, R. & Scolaro, L. M. Supramolecular mimetic peroxidase based on hemin and PAMAM dendrimers. Chem. Commun. 14, 688–690 (2008).

Schmidt, B. V. K. J., Fechler, N., Falkenhagen, J. & Lutz, J.-F. Controlled folding of synthetic polymer chains through the formation of positionable covalent bridges. Nat. Chem. 3, 234–238 (2011).

Terashima, T. et al. Single-chain folding of polymers for catalytic systems in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4742–4745 (2011).

Wiester, M. J., Ulmann, P. A. & Mirkin, C. A. Enzyme mimics based upon supramolecular coordination chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 114–137 (2011).

Kaphan, D. M., Levin, M. D., Bergman, R. G., Raymond, K. N. & Toste, F. D. A supramolecular microenvironment strategy for transition metal catalysis. Science 350, 1235–1238 (2015).

Nath, I., Chakraborty, J. & Verpoort, F. Metal organic frameworks mimicking natural enzymes: a structural and functional analogy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 4127–4170 (2016).

Liu, Q., Wang, H., Shi, X. H., Wang, Z.-G. & Ding, B. Q. Self-assembled DNA/peptide-based nanoparticle exhibiting synergistic enzymatic activity. ACS Nano 11, 7251–7258 (2017).

Mundsinger, K., Izuagbe, A., Tuten, B. T., Roesky, P. W. & Barner-Kowollik, C. Single chain nanoparticles in catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202311734 (2024).

Lutz, J.-F., Ouchi, M., Liu, D. R. & Sawamoto, M. Sequence-controlled polymers. Science 341, 1238149 (2013).

Lombardi, A., Pirro, F., Maglio, O., Chino, M. & DeGrado, W. F. De novo design of four-helix bundle metalloproteins: one scaffold, diverse reactivities. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1148–1159 (2019).

Rose, G. D., Fleming, P. J., Banavar, J. R. & Maritan, A. A backbone-based theory of protein folding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 16623–16633 (2006).

Zaccai, G. How soft is a protein? A protein dynamics force constant measured by neutron scattering. Science 288, 1604–1607 (2000).

Henzler-Wildman, K. & Kern, D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature 450, 964–972 (2007).

Magazù, S. et al. Protein dynamics as seen by (quasi) elastic neutron scattering. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1861, 3504–3512 (2017).

Robertson, D. E. et al. Design and synthesis of multi-haem proteins. Nature 368, 425–432 (1994).

Sugase, K., Dyson, H. J. & Wright, P. E. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature 447, 1021–1025 (2007).

Hilburg, S. L., Ruan, Z., Xu, T. & Alexander-Katz, A. Behavior of protein-inspired synthetic random heteropolymers. Macromolecules 53, 9187–9199 (2020).

Jiang, T. et al. Single-chain heteropolymers transport protons selectively and rapidly. Nature 577, 216–220 (2020).

Daghrir, R. & Drogui, P. Tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 11, 209–227 (2013).

Dill, K. A. et al. Principles of protein folding — a perspective from simple exact models. Protein Sci. 4, 561–602 (1995).

Ruan, Z. et al. Population-based heteropolymer design to mimic protein mixtures. Nature 615, 251–258 (2023).

Artar, M., Souren, E. R. J., Terashima, T., Meijer, E. W. & Palmans, A. R. A. Single chain polymeric nanoparticles as selective hydrophobic reaction spaces in water. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 1099–1103 (2015).

Hoshino, Y. et al. The rational design of a synthetic polymer nanoparticle that neutralizes a toxic peptide in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 33–38 (2012).

Popot, J.-L. et al. Amphipols from A to Z. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 40, 379–408 (2011).

Chakraborty, A. K. & Shakhnovich, E. I. Phase behavior of random copolymers in quenched random media. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 10751–10763 (1995).

Geissler, P. L. & Shakhnovich, E. I. Mechanical response of random heteropolymers. Macromolecules 35, 4429–4436 (2002).

Panganiban, B. et al. Random heteropolymers preserve protein function in foreign environments. Science 359, 1239–1243 (2018).

Koshland, D. E. Jr The key–lock theory and the induced fit theory. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 33, 2375–2378 (1995).

Jayapurna, I. et al. Sequence design of random heteropolymers as protein mimics. Biomacromolecules 24, 652–660 (2023).

Hoshino, T. & Sato, T. Squalene–hopene cyclase: catalytic mechanism and substrate recognition. Chem. Commun. 4, 291–301 (2002).

Moffet, D. A. et al. Peroxidase activity in heme proteins derived from a designed combinatorial library. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 7612–7613 (2000).

Walker, F. A. Models of the bis-histidine-ligated electron-transferring cytochromes. Comparative geometric and electronic structure of low-spin ferro- and ferrihemes. Chem. Rev. 104, 589–616 (2004).

Tronnet, A. et al. Star-like polypeptides as simplified analogues of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) metalloenzymes. Macromol. Biosci. 24, 2400155–2400155 (2024).

Yu, H. et al. Mapping composition evolution through synthesis, purification, and depolymerization of random heteropolymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 6178–6188 (2024).

Arbe, A., Colmenero, J., Monkenbusch, M. & Richter, D. Dynamics of glass-forming polymers: “homogeneous” versus “heterogeneous” scenario. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 590–593 (1998).

Hart-Cooper, W. M., Clary, K. N., Toste, F. D., Bergman, R. G. & Raymond, K. N. Selective monoterpene-like cyclization reactions achieved by water exclusion from reactive intermediates in a supramolecular catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17873–17876 (2012).

Hammer, S. C., Marjanovic, A., Dominicus, J. M., Nestl, B. M. & Hauer, B. Squalene hopene cyclases are protonases for stereoselective Brønsted acid catalysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 121–126 (2015).

Gibney, B. R. & Dutton, P. L. Histidine placement in de novo–designed heme proteins. Protein Sci. 8, 1888–1898 (1999).

Walker, F. A., Reis, D. & Balke, V. L. Models of the cytochromes b. 5. EPR studies of low-spin iron(III) tetraphenylporphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 6888–6898 (1984).

Murphy, E. A. et al. High-throughput generation of block copolymer libraries via click chemistry and automated chromatography. Macromolecules 58, 8369–8376 (2025).

Cochran, A. G. & Schultz, P. G. Peroxidase-activity of an antibody heme complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 9414–9415 (1990).

Tracy, T. S. Atypical cytochrome P450 kinetics. Drugs R D 7, 349–363 (2006).

Wu, G.-R. et al. Efficient degradation of tetracycline antibiotics by engineered myoglobin with high peroxidase activity. Molecules 27, 8660 (2022).

Jaacks, V. A novel method of determination of reactivity ratios in binary and ternary copolymerizations. Makromolek. Chem. 161, 161–172 (1972).

Flynn, P. F., Mattiello, D. L., Hill, H. D. W. & Wand, A. J. Optimal use of cryogenic probe technology in NMR studies of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 4823–4824 (2000).

Andreini, C., Cavallaro, G., Lorenzini, S. & Rosato, A. MetalPDB: a database of metal sites in biological macromolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D312–D319 (2013).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Martínez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martínez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Shu, J. Y. et al. Amphiphilic peptide−polymer conjugates based on the coiled-coil helix bundle. Biomacromolecules 11, 1443–1452 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) under contract HDTRA1-19-1-0011 and HDTRA1-24-1-0012, the US Department of Defense (DOD) under contract W911NF-13-1-0232 through the Army Research Office (ARO) and the National Science Foundation under contract DMR- 2104443 and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (grant no. G-2021-16757). T.J. and A.A-K. thank the support from the National Science Foundation under EFRI E3P Award Number 2132025. We thank E. Dailing in the Molecular Foundry at the LBNL for assistance with gel permeation chromatograph measurements, and C. Citek in the Catalysis Laboratory at the LBNL for assistance with stopped-flow experiments. Work at the Molecular Foundry, Catalysis Laboratory, and ALS was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the US Department of Energy under contract no. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We thank H. Celik, R. Giovine and the Core NMR Facility of Pines Magnetic Resonance Center (PMRC Core) for spectroscopic assistance. The instruments used in this work were supported by the PMRC Core and in part supported by NIH S10OD024998. The ERP Spectroscopy experiments were supported by NIH R35GM126961. We thank the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division, under award no. DE-SC0024447, for its support of neutron scattering and molecular simulation work. This work used resources at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) and Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. SANS studies performed on the CG-3 instrument are funded by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research, U.S. Department of Energy under Contract FWP ERKP291. This work was partially supported by the Director, Office of Sciences, and the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Bioscience of the US Department of Energy at LBNL (grant no. DE-AC02-05CH11231). Access to HFBS was provided by the Center for High Resolution Neutron Scattering, a partnership between the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the National Science Foundation under agreement no. DMR-2010792. We thank M. Tyagi for the assistance with neutron experiments and the support of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, US Department of Commerce, in providing neutron research facilities used in this work. A.G. was partially supported by National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-2146752. T.J. was partially supported by the Chyn Duoq Shiah Memorial Fellowship. P.G was partially supported by the MIT Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP). A.A-K. was partially supported by the Michael and Sonja Koerner Chair. T.X. thanks the dear late colleague Phillip Geissler for encouraging discussions back in 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.X. conceived the idea and guided the project. H.Y., M.E. and P.K. synthesized and characterized the RHPs as enzyme mimics. M.E. and K.T. performed metalloprotein analysis. M.E. investigated haeme-binding RHPs and P.K. investigated RHPs for citronella cyclization. H.Y. conducted in-depth analysis and kinetic studies on haeme-binding RHPs. S.L.H., T.J., P.G., and A.A.-K. performed all-atom molecular dynamics simulation studies. Z.L., Z.R., A.G. and Y.Z. conducted neutron scattering experiments and analysis. I.J., S.L. and H.H. performed RHP sequence analysis. D.M.L. performed NMR studies. W.F., M.E. and R.D.B. conducted EPR experiments. F.Y., P.K. and J.G. conducted XANES experiments. F.D.T. assisted with the analysis of citronella cyclization experiments. All authors participated in writing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.A.-K., S.L.H., T.X., H.Y., M.E. and P.K. have filed a PCT patent application (US Provisional Application. no. 63/430902). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Colin Bonduelle, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 2 Ten RHP-P1 (a) and RHP-S1 (b) sequences simulated from RHPapp output.

To simulate RHP sequences, a batch of 10,000 sequences for RHP-P1 and RHP-S1 was generated using RHPapp, from which 10 were randomly sampled for MD simulation. These sequences represent the blockiness or randomness of RHP sequences from the batch. MMA, OEGMA, EHMA, and SPMA are shown in gray, blue, red, and yellow, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Heterogeneous dynamics of RHP-S1.

a, Root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) of the RHP-S1 backbone and side-chains at 300 K with mean and standard deviations shown. b, Single chain shown with multiple stable conformations. c, Surface compositions for all conformations compared to sequence composition by mass as calculated by alpha shape analysis. Plots shown for 10 RHP-S1 sequences. Corresponding sequence is labeled in each plot, and the sequences can be found in Extended Data Fig. 2b.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Comparison of the dynamics between sidechain and backbone in RHP-P1.

a, Average segmental root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of nine RHP-P1 sequences (blue: combined backbone and sidechain RMSF, green: sidechain only RMSF, orange: backbone only RMSF). RMSF of SEQ10 is shown in Fig. 2a. RMSF is plotted as a function of segment position along a representative RHP-P1 chain based on MD simulation. The HLB value of each monomer was also shown on the same plot (red, left axis). Error bars represent the standard errors calculated across the ten conformations. Corresponding sequence is labeled in each plot, and the sequences can be found in Extended Data Fig. 2a. b, Linear regression between average segmental root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) and HLB value of each monomer in RHP-P1 shows positive correlation. Left: combined backbone and sidechain RMSF, Middle: backbone only RMSF, Right: backbone only RMSF.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparison of the dynamics between sidechain and backbone in RHP-S1.

a, Average segmental root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of ten RHP-S1 sequences (blue: combined backbone and sidechain RMSF, green: sidechain only RMSF, orange: backbone only RMSF). RMSF is plotted as a function of segment position along a representative RHP-S1 chain based on MD simulation. The HLB value of each monomer was also shown on the same plot (red, left axis). Error bars represent the standard errors calculated across the ten conformations. Corresponding sequence is labeled in each plot, and the sequences can be found in Extended Data Fig. 2b. b, Linear regression between average segmental root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) and HLB value of each monomer in RHP-S1 shows positive correlation. Left: combined backbone and sidechain RMSF, Middle: backbone only RMSF, Right: backbone only RMSF.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Small angle neutron scattering of RHP-P1 and RHP-S1.

The experiments were performed in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Guinier analysis showed that 10 mg/mL RHP-P1 has Rg = 3.6 nm, and 10 mg/mL RHP-S1 has Rg = 6.9 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 NOESY NMR of RHP-P1 with citronellal in D2O.

Interactions between SPMA and head methyl groups of CA were not observed (D8 = 0.4 s).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Comparison of RHP-P1, RHP-S1, and RHP-S2 to understand the effects of colocalizing EHMA and SPMA.

a, PCA analysis of RHP-P1, RHP-S1, and RHP-S2. The horizontal axis (PC1) reflects the segmental hydrophobicity, whereas the vertical axis (PC2) represents the arrangement of hydrophobic and hydrophilic blocks within the sequence. The results show that RHP-S2 exhibits higher overall hydrophobicity compared to RHP-P1 and RHP-S1. b, Distribution of SPMA-containing segments in the PCA map of RHP-S2. The horizontal axis (PC1) reflects the segmental hydrophobicity, whereas the vertical axis (PC2) represents the arrangement of hydrophobic and hydrophilic blocks within the sequence. c, Sliding window sequence analysis of monomer hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) of RHP-P1, RHP-S1, and RHP-S2. The results show that all three RHPs exhibit similar dynamic range of segmental hydrophobicity. The RHP chain used here is arbitrarily chosen from 100,000 simulated sequences. For clarity, only the first 90 monomers are shown. d, DLS measurements of RHP-P1, RHP-S1, and RHP-S2. The measurements were performed in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with a RHP concentration of 20 mg/mL, matching the conditions used for the CA cyclization reaction. Number averaged diameter is shown here.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Investigating the effects of sequence heterogeneity in heme-binding RHPs by SEC and solvent fractionation.

a, SEC elution profile of heme-bound RHP-H1. RHP and heme were mixed at 1:1 molar ratio to obtain heme-bound RHPs. The mixture was then subjected to SEC. The elution profile was tracked at different wavelengths to distinguish the whole RHP population (monitored at 260 nm) versus the heme-bound RHP fraction (monitored at 380 nm, and RHP doesn’t absorb at 380 nm). Left: raw data. Right: normalized absorbance to account for the differences in absorption coefficients between species. The nearly identical elution profiles suggest that heme binding is consistent across RHP chains in RHP-H1. SEC was performed with an instrument equipped with an isocratic pump (1200 Infinity II, Agilent) and a UV detector. Agilent Bio SEC-5 column was used (300 Å, 7.8 ×300 mm) in this experiment. The elution profile is noisy at elution time t > 10 min due to the buffer and trace DMF elution. b, Comparison of SEC elution profiles of mixed heme/RHP-H1, RHP-H1 alone and heme alone. The elution peak of buffer and solvent was at around 10.5 min. c, NMR spectra of the organic and water phase residues of RHP-H1 after liquid-liquid extraction (500 MHz, CDCl3). To perform the extraction, 0.6 ml RHP solution (D2O, 50 mg/ml) was mixed with 0.6 ml organic solvent (CHCl3, DCM, or ethyl acetate). The mixtures were shaken vigorously, and the opaque solutions were centrifuged (8000 rpm, 5–10 min) to obtain well-separated water and organic phases. Each phase was dried to remove solvent and re-dissolved in CDCl3 for NMR measurements and comparison. In all three trials, the residues recovered from organic phase are below 1 mg. The results show that minimal RHP chains were partitioned into organic phases.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, H., Eres, M., Hilburg, S.L. et al. Random heteropolymers as enzyme mimics. Nature 649, 83–90 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09860-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09860-9